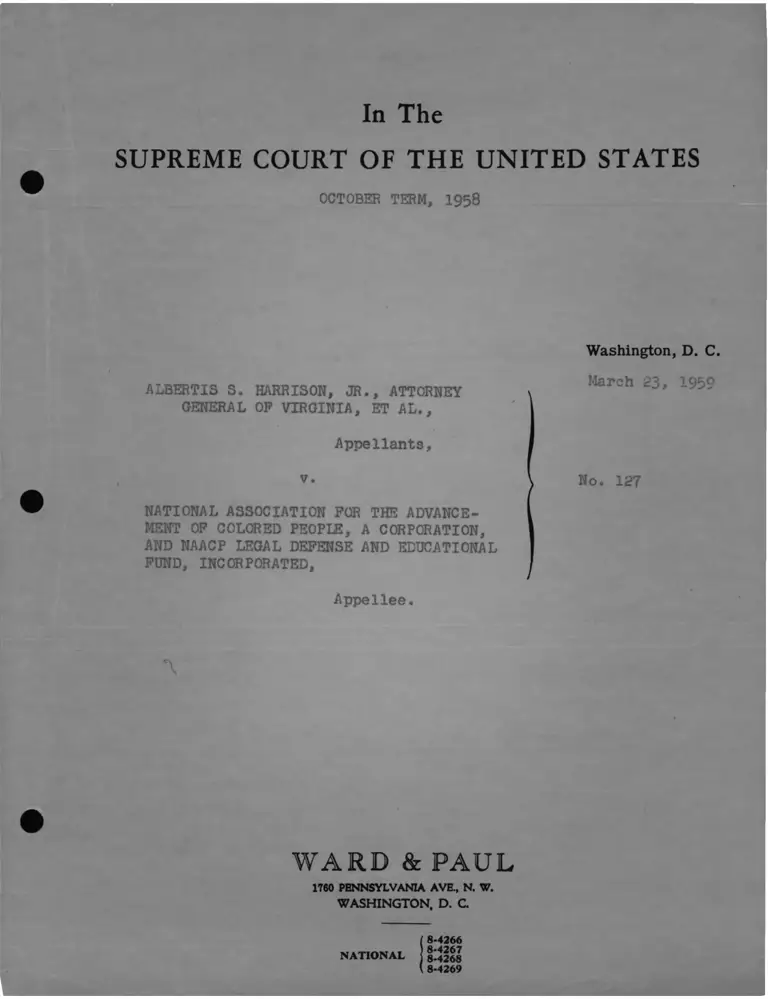

Harrison v. NAACP Argument on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 23, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. NAACP Argument on Behalf of Appellants, 1959. 4f794f7d-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/152c1560-38b1-47b2-9ba9-7f86cba64d6d/harrison-v-naacp-argument-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Copied!

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1958

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY

GENERAL OP VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OP COLORED PEOPLE, A CORPORATION,

AND NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED,

Washington, D. C.

March 23, 195>9

No. 127

Appellee.

■ \

WARD & PAUL

1760 PENNSYLVANIA AVE., N. W.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

NATIONAL

8-4266

8-4267

8-4268

8-4269

A

C O N T E N T S

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR . ,

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

APPELLANTS

By Mr. J. Segar Gravatt 3

1

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1958

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v. No. 127

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, A CORPORATION,

AND NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED,

Appellee. :

Washington, D.C.

Monday, March 23> 1959

The above-entitled matter came on for oral argument

at 4:16 o'clock, p.m..

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren, and Associate

Justices Black, Frankfurter, Douglas, Clark, Harlan,

Brennan, Whittaker, and Stewart.

APPEARANCES:

On behalf of Albertis S. Harrison, Jr., Attorney

General of Virginia, Et Al., Appellants:

J. Segar Gravatt, Blackstone, Virginia.

2

On behalf of National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc., Appellees:

Robert L. Carter, 20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

Oliver W. Kill, 118 E. Leigh Street,

Richmond, Virginia.

On behalf of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., Appellees:

Thurgood Marshall, 10 Columbus Circle,

New York, N. Y.

Spotsviood W. Robinson, III, 623 North Third

Street, Richmond, Virginia.

3

The Chief Justice: No. 127, Albertis S. Harrison, Jr.,

Attorney General of Virginia, et al, Appellants, versus the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

a Corporation, and NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Incorporated.

The Clerk: Counsel are present.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Gravatt, you may proceed.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, ET AL.

By Mr. Gravatt:

Mr. Gravatt: Mr. Chief Justice, if Your Honors

please, this case come to this Court on a direct appeal from a

three judge statutory court sitting in the Eastern District

of Virginia, by virtue of Title 28, USC 1253.

The controversy here arises from a bill filed in an

equity proceeding by the National Association for Colored

People and an associate organization, the National Association

for Colored People Legal Defense Fund, in which they asked the

lower court to declare five Virginia statutes unconstitutional

upon the grounds that they violated the commerce clause of the

Constitution and rights of the complainant under the Fourteenth

and First Amendment.

The defendant filed a motion to dismiss the complaint.

Among the grounds stated is that one of the principal con

tentions which vie wish to make here — namely, that the court

4

should have withheld its extension of equity jurisdiction

and should have remanded the case, or held the case upon its

docket pending state construction of these statutes.

The matter was — the motion, of course, was over

ruled by the lower court, answers were filed, and evidence was

heard. The majority opinion, written by two Justices -- Judge

Soper and District Judge Hoffman — overheld three of the

statutes — Chap. 31 j 32 and 35 — to be plainly in violation

of the Constitution, to be without any ambiguity, and referred,

or retained the case upon the docket, and directed the

plaintiffs to apply to the state court for a construction

of the remaining two statutes, 33 and 3 6.

The statutes briefly -- these three statutes that

we have here under consideration fall into two classes,

Chapter 31 and Chapter 32 — what you would commonly character

ize as registration statutes, in that they require the registry

of the name of the corporation in this case and the supplying

of certain information therewith with the clerk of the

State Corporation Commission, provided the corporation or

association is engaged in certain activities defined in the

statute.

The other statute, which is Section Chapter 35

of the 1956 Acts of the Extra Session of the General Assembly,

is a statute which deals with the unauthorized practice of

law. It is quite closely akin to the other two statutes

5

which the court directed toe referred to the state courts for

a construction.

We shall argue here, if the Court please, two

questions. They are somewhat related to each other.

The first question is — should the lower court

have exercised, in the exercise of its discretion, retained

this case upon its docket, with a suggestion to the plaintiffs

that they apply to the state court for a construction of these

statutes.

I do not suppose that in fact the appellees in their

brief recognize the validity of that principle. They have

undertaken to develop an exception to it, on the toasis that

that will only toe done, that a federal equity court will only

sutomit a statute, and withhold its exercise of its equity

jurisdiction — will only do so when it is apparent to the

federal court that there is a reasonable toasis upon which the

statute in question could toe construed or interpreted in a

manner which would make it constitutional.

The problem which we present is a problem which has

been recognized toy this Court and toy judges and statesmen

through the years as toeing a delicate and an extremely serious

function, and an extremely serious matter.

This Court has repeatedly said that it is concerned

with one of the most delicate areas in which federal courts

are required to discharge their duties, namely, that area

in which they come in conflict with state powers and state

courts.

I do not suppose that anyone would question the

fact that the power to define crime, to define what acts are

punishable acts., is a power reserved to the states under the

Ninth and the Tenth amendment of the Constitution.

Of course, that power has to he exercised subject

always to the limitations imposed by the states in the Federal

Constitution, including the Fourteenth Amendment limitations

which are contended for here.

I do not suppose that anyone will question that

the final authority for the interpretation and the construction

of state statutes, under our system of government, lies in

the state courts and appropriately should be exercised there.

I further do not suppose that anyone would question the fact

that once such a statute is construed by the state courts,

once the state court has determined the scope, has determined

the meaning of its language, the area within which it operates,

the class or those persons to whom it will apply, that this

Court then has the final responsibility to determine whether,

as thus interpreted, or interpreted, the statute is in

conflict with those limitations imposed upon the states in

our Constitution.

Those principles, and the doctrine that has been

characterized in some of the decisions, and which seems to me

6

7

very aptly described as a doctrine of equitable abstention

from the assumption of power and of jurisdiction, which a

federal court has — that doctrine, if you please, is predicated

upon those principles which I have mentioned to you, which

find their origin in the very structure of the Constitution of

the United States. It is a doctrine that is exercised in

deference to the division of power ordained in the Constitution.

There is, however, another great and compelling

reason that supports and directs the discretion of a chancery

court in withholding its jurisdiction, and that is that this

Court, the function and the responsibility — as I apologize

for suggesting — has-a heavy and a great and an enduring

responsibility.

What is done here, in the construction of our

Federal Constitution, reaches on down the age3 whenever and

wherever it may be appropriate for it to be considered.

For that reason, this Court has always — it has

always been a maxim, a canon of the exercise of its power —

that It would avoid deciding a case upon a constitutional

issue if the case could be properly disposed of upon another

ground.

All of those considerations are not, if Your Honors

please, simply considerations of form. They are considerations

that reach to the very substance of our system of government.

They are considerations that are of the most compelling nature

8

when we come to consider the friction that may be generated

by the arbitrary exercise of federal power in an area that

primarily is the responsibility for the states to operate in.

And I am confident that a court of equity and that this Court

will always recognise that a chancery, sitting with such

great power to be exercised upon a state legislature and upon

all its people, will use that forebearance in applying it that

is dictated by the considerations and the constitutional

principles which I have very briefly referred bo.

This doctrine —

Justice Douglas: Does this law apply to Just

this organization, or does it apply to others?

Mr. Gravatt: It applies, so far as I know, sir

there e,re a great line of cases in which the court has

applied it in a great many different situations. I think

it ap'olies to this principle here, and I think it applies in

all areas.

Justice Douglas: Does it apply to the Virginia

State Bar Association?

Mr. Gravatt: Do you —

Justice Douglas. Chapters 31 and 32 -- do they

aoply to any organization but the NAACP?

Mr. Gravatt: provisions with respect to the Legal

Aid Society of the Bar Association.

Justice Douglas. Yes.

9

Mr. Gravatt. Yes, they are provisions that

apply to everybody that falls within them.

Justice Douglas. I guess we had better understand

each other.

The Chief Justice. We will recess now, Mr. Gravatt.

(Whereupon, at 4:30 p.m., the hearing was

recessed to reconvene at 12 o'clock noon, Tuesday,

March 24, 1959.)