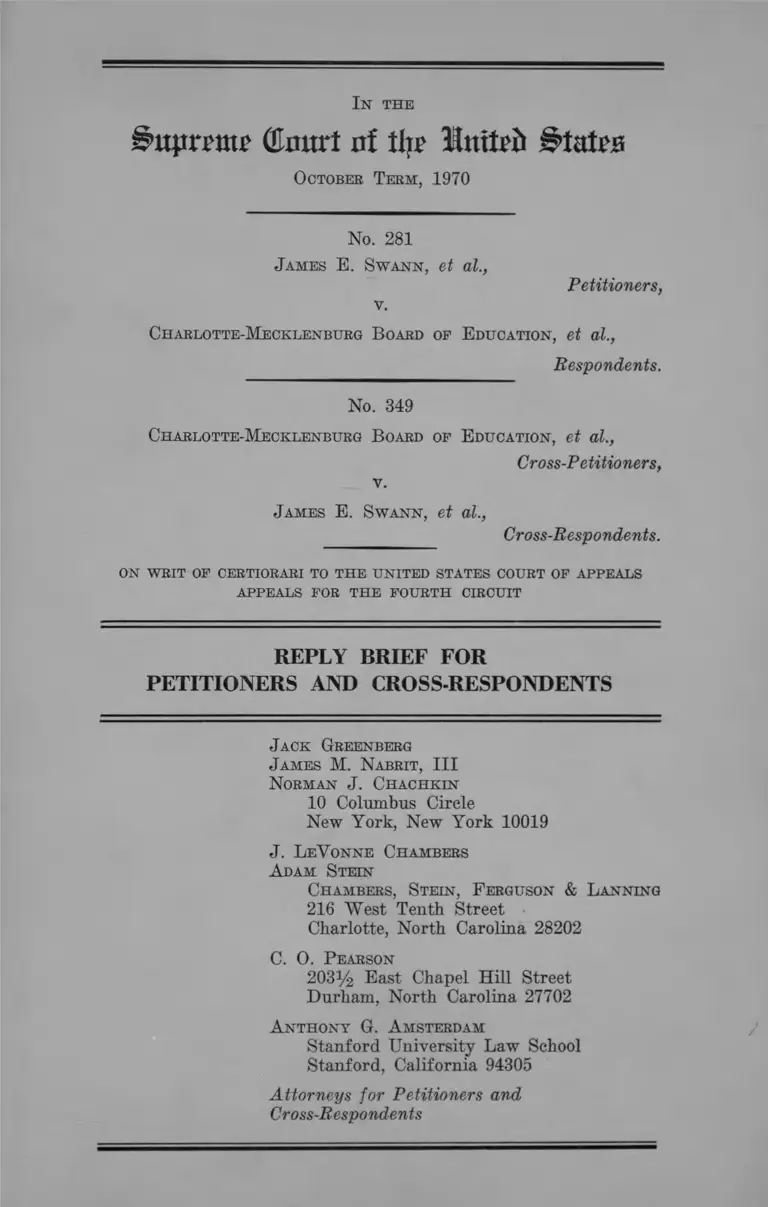

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Reply Brief for Petitioners and Cross-Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Reply Brief for Petitioners and Cross-Respondents, 1970. 1c07c584-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/154f428a-aa1d-4d16-8156-be6fad57540a/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-reply-brief-for-petitioners-and-cross-respondents. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

i>uprmp Qlmtrt nf tlu' Inttpfc States

October Term, 1970

No. 281

James E. Swann, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 349

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, et al.,

Cross-Petitioners,

v.

James E. Swann, et al.,

Cross-Respondents.

on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR

PETITIONERS AND CROSS-RESPONDENTS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. LeVonne Chambers

A dam Stein

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Lanning

216 West Tenth Street •

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. O. Pearson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Anthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners and

Cross-Respondents

I N D E X

Preliminary Statement ....................................................... 1

A r g u m e n t :

I. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Schools Were

Segregated by Unconstitutional Governmental

Action ........................................................................... 3

II. The Assignment Plan Now in Effect Is Workable

and Desegregates the Schools ................................. 17

III. The School Board Proposes No Viable Rule of

Law to Define the Goal of a Unitary System ..... 24

IV. The District Court Was Correct in Not Attempt

ing to Declare a General Rule of Law to Govern

the Multitude of Varied Circumstances of School

Segregation in Other Cities and Other Parts of

the United States ....................................................... 28

V. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Does Not in Any

Way Limit the Power of the Courts to Fashion

Remedies for Unconstitutional Racial Segrega

tion in Public Schools or Prohibit the Courts

from Requiring Busing of Pupils to Disestab

lish Dual Segregated School Systems ..................... 32

PAGE

11

T able op A uthorities

Cases:

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397

F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968)................................................... 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....3, 4, 8,

14, 24, 29,

30,37

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)....... 3

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) ................................................................................. 3

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 290 (1970)................................................................... 27

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. City of Philadel

phia, 353 U.S. 230 (1957).................................................... 17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)............................... 3

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education, 394

F.2d 410 (4th Cir. 1968), affirming 273 F. Supp. 289

(E.D. N.C. 1967)................................................................. 17

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, O.T. 1970, No. 436 ......................................... 25, 27

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma Public

Schools, 396 U.S. 269 (1969)............................................... 24

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) affirmed 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir. 1967), cert, den., 387 U.S. 931 (1967)................... 16

Eason v. Buffaloe, 198 N.C. 520, 152 S.E. 496 (1930).... 13

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969),

affirming 338 F. Supp. 678 (D. D.C. 1968)................. 17

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)................... 17

PAGE

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)......................................................... 24

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) cert, den., 396 U.S.

940 (1969) .......................................................................16,

Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F.2d 851 (8th Cir. 1970).............

Keyes v. School District Number One, Denver, 303

F. Supp. 279 (D. Colo. 1969).........................................

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939).............................17,

Local 189, Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969)...........................

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)...........

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, —— F.2d ------ (5th Cir., No. 28643,

May 11, 1970) ................................................................. 16,

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) ...............................................................................24,

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970)

Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N.C. 290, 37 S.E.2d 895 (1946)

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968).....

Ross v. Eckels, ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir., No. 30080,

August 25, 1970)............................................................. 16,

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)...........................

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), reversed sub

nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,

396 U.S. 290 (1970).........................................................

25

16

16

31

17

17

25

30

24

13

24

25

13

37

IV

United States v. Board of Education of Baldwin

County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970)....................... 16

United States v. Board of Education School District

No. 1, Tulsa, Okla.,------ F .2d------- (10th Cir. 1970).... 25

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, den.,

395 U.S. 907 (1969)......................................................... 16

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir., 1969), cert, den.,

396 U.S. 1011 (1970) ......................................... ............. 16

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969)................................................. 24

United States v. School District, 151 of Cook County,

Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1968), affirmed,

404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968)....................................... 16, 25

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, 423 F.2d 1132

(5th Cir. 1970) .................................................................

Vernon v. R. J. Reynolds Realty Co., 226 N.C. 58, 36

S.E.2d 710 (1946) ...........................................................

PAGE

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1343 ................................................................... 35

42 U.S.C. §1983 ................................................................... 35

42 U.S.C. §2000c, Civil Rights Act of 1964, §401 ....2, 32, 33,

34, 35,

39, 40

42 U.S.C. §2000c-6(a), Civil Rights Act of 1964, §407(a)

2, 32

42 U.S.C. §2000c-8, Civil Rights Act of 1964, §409 ....... 35

42 U.S.C. §§3601 et seq., Civil Rights Act of 1968 ....... 14

N. C. Gen. Stat. §115-176................................................... 6

16

13

V

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Charlotte Observer, Sept. 5, 1970 ................................... 14

110 Cong. Eec. 1598 ........................................................... 39

110 Cong. Eec. 2280 .........................................................39, 40

1 st t h e

Smumitr (Court of ttjr lluitrii ^tatrs

O ctober T erm , 1970

No. 281

J ames E . S w an n , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 349

Charlotte-Mecklenburg B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Cross-Petitioners,

v.

J ames E . S w ann , et al.,

Cross-Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR

PETITIONERS AND CROSS-RESPONDENTS

Preliminary Statement

The respondents and cross-petitioners (hereinafter

school hoard) seek to pose the issue in this case of whether

a school board may continue to operate one or more pre

2

dominantly black schools. We feel that the issue is more

properly posed in the decision of the district court below,

namely, whether in the context of the facts developed in

this case, the pervasive role of the state and its agencies

in creating and perpetuating a racially segregated system,

a school board may continue to deny equal educational

opportunities to black children on the pretext of preserving

“neighborhood schools” or avoiding transportation of stu

dents when a feasible alternative is available for complete

desegregation. This reply is addressed to the activities

and practices of the state, particularly those of the school

board, which produced the segregated system which the

district court sought to eliminate; the feasibility and prac

ticability of the plan directed by the court; and the fact

that the school board and the various amici who have sub

mitted briefs in this matter suggest no viable alternative

rule of law to that adopted by the district court and advo

cated by the petitioners herein. We also discuss the pos

sible applicability of the decision of the Court in this case

to other jurisdictions and the applicability of §§401 (b) and

407(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000c(b)

and 42 U.S.C. §2000c-6(a).

For the Court’s information we are attaching as an ap

pendix to this reply a copy of the interim report filed by

the school board showing the results o f desegregation for

the present school term under the plan directed by the

district court. As the report demonstrates the plan elim

inates all racially identifiable schools in the system with the

exception of 3 elementary schools and as to these 3 schools

some steps are now being taken in order to alleviate the

overcrowded conditions and to prevent resegregation.

3

ARGUMENT

I.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Schools Were

Segregated by Unconstitutional Governmental Action.

The School Board and several amici1 challenge for the

first time the district court’s findings of state created and

perpetuated racially segregated housing and public schools.2

They contend that the admitted segregation is merely

adventitious. The record, however, clearly demonstrates

the contrary. As the district court stated in its Memo

randum Opinion of November 7, 1969, segregation of the

races in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg system is not “ consti

tutionally benign.”

In previous opinions the facts respecting [the location

of schools] . . . their controlled size and their popu

1 See, e.g,, Amicus Curiae Brief for the Classroom Teachers

Association of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School System, Incorpo

rated, pp. 20-21.

2 The Commonwealth of Virginia suggests that such inquiry is

irrelevant. See, e.g., Brief for the Commonwealth of Virginia,

Amicus Curiae, pp. 8-10. The district court found, however, that

the varied actions of the state, including the School Board, had

resulted in racially segregated schools as condemned in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955);

that inquiry into the forces of the state creating or perpetuating

racial discrimination were indeed appropriate and required by

decisions of this Court; see, e.g., Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961), for the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibits “ State support of segregated schools through any arrange

ment, management, funds, or property.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1, 19 (1958). This Court further stated in Cooper, supra at 17:

“ In short, the constitutional rights of children not to be discrim

inated against in school admission on grounds of race or color

declared by this Court in the Brown ease can neither be nullified

openly and directly . . . nor nullified indirectly . . . through evasive

schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘ingeniously’ or ‘ingenu

ously.’ ” Finding state imposed segregation and a feasible means

to correct it, the district court was obligated by the Constitution to

enforce the constitutional rights of the black children of this school

system.

4

lation have already been found. Briefly summarized,

these facts are that the present location of white schools

in white areas and of black schools in black areas is

the result of a varied group of elements of public and

private action, all deriving their basic strength origi

nally from public law or state or local governmental

action. These elements include among others the legal

separation of the races in schools, school buses, public

accommodations and housing; racial restrictions in

deeds to land; zoning ordinances; city planning; urban

renewal; location of public low rent housing; and the

actions of the present School Board and others, before

and since 1954, in locating and controlling the capacity

of schools so that there would usually be black schools

handy to black neighborhoods and white schools for

white neighborhoods. There is so much state action

embedded in and shaping these events that the result

ing segregation is not innocent or “ de facto,” and the

resulting schools are not “unitary” or desegregated.3

(657a, 661a-662a).

3 Contrary to the board’s assertion (see Briefs of Respondents

and Cross-Petitioners, p. 46), this finding did not constitute a re

versal of the previous findings of the court; rather it was at this

point that the court was pointedly advised by the board, that the

board had no intention of complying with the directives of the

court. The district court has described its painstaking, patient,

but unsuccessful efforts to encourage the board to discharge its

affirmative duty to desegregate. (See Supplemental Memorandum

1221a-1238a). It was the board’s recalcitrance which led Judge

Sobeloff to note in dissent that “ this Board, through a majority

of its members, far from making ‘every reasonable effort’ to ful

fill its constitutional obligation, has resisted and delayed desegre

gation at every turn.” (No. 9, 1291a-1293a) Moreover, the record

clearly demonstrates that the constitutional violations which the

district court sought to remedy resulted not just from practices

of other governmental agencies but to a large extent from the

board’s conduct and action in locating and controlling schools,

school sites, capacities, attendance districts, etc., all taken in con

junction with and in furtherance of the developing racial housing

patterns, both before and after this Court’s decision in Brown.

5

We discuss below some of the record evidence supporting

these findings.

In the district court’s findings of April 23, 1969 (285a,

296a), the court described Charlotte and Mecklenburg

County as follows:

The central city may be likened to an automobile hub

cap, the perimeter area to a wheel, and the county area

to the rubber tire. Tryon Street and Southern Rail

road run generally through the county and the city

from the northeast to the southwest. Trade Street runs

generally northwest to southeast and crosses Tryon

Street at the center of town at Independence Square.

Charlotte originally grew along the Southern Railroad

tracks. Textile mills with mill villages, once almost

entirely white, were built. Business and other industry

followed the highways and the railroad. The railroad

and parallel highways and business and industrial de

velopment formed something of a barrier between

east and west.

By the end of World War II many Negro families

lived in the center of Charlotte just east of Independ

ence Square in what is known as the First Ward-

Second Ward-Cherry-Brooklyn area. However, the

bulk of Charlotte’s black population lived west of the

railroad and Tryon Street and north of Trade Street

in the northwest part of town. The high-priced, al

most exclusively white, country was east of Tryon

Street and south of Trade in the Myers Park-Provi-

dence-Sharon-Eastover area. Charlotte thus had a

very high degree of segregation of housing before the

first Brown decision.

Today, the degree of segregation in housing is even more

pronounced. Some of the factors which have contributed

to the school segregation follow:

6

1. Location and control of schools. Prior to 1954 all

public schools in the City of Charlotte and Mecklenburg

County were segregated pursuant to the state law and

Constitution.4 The district court attached as an Exhibit

to its Memorandum of Decision and Order of August 3,

1970 a collection of segregation codes of the state which,

as indicated by the Memorandum Decision (Br. A4), re

mained in the state statutes as late as 1969. Schools were

located and students and staff personnel were assigned to

the various schools on the basis of race. Subsequent to the

Brown decision and prior to the institution of this pro

ceeding no affirmative steps were taken by the board to

disestablish the racially segregated system. Some token

integration did take place under the North Carolina Pupil

Assignment Act, N. C. Gen. Stat. §115-176, pursuant to

which a few black students requested transfer to previ

ously all-white schools. The school board, however, con

tinued to locate and control the various capacities of schools

in order to maintain racial segregation.48- These practices

have continued even through the present day.

In conjunction with the racially developing residential

patterns, the school board built or made additions to the

following schools subsequent to 1954 solely to accommo

date black students.

4 Separate boards governed the city and county schools until

1961, at which time the two school units were merged.

4a The board controlled grade structures to maintain segregation.

In 1965 the system had a basically 6-3-3 grade structure, except

that some black schools had different patterns to facilitate racial

segregation such as grades: 1-4, 1-7, and 5-9, for example. (See

Appellants’ Appendix in 1966 appeal to the 4th Circuit, No. 10207,

pp. 25-29).

7

Schools Year of Construction Years of Additions

Burns 1968

Marie Davis 1951 1953

1957

1959

Double Oaks 1952 1955

1965

Druid Hills 1960 1964

First Ward 1912 1950)

1961)

1968) practically

complete new

facilities.

Lincoln Heights 1956 1958

Oaklawn 1964

University Park 1957 1958

1964

(Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1 in original record; 124a-132a)5

Several white schools were built in white areas and pre

dictably enrolled only white students:

Schools Year of Construction

Devonshire 1964

Albemarle Road 1968

Beverly Woods 1969

These examples are not meant to be exclusive but only

exemplary of the practices followed by the board prior

5 “ Q. Dr. Self, when you built schools since 1954, what efforts

did you make, other than what you testified to yesterday, to locate

the schools in an area that would effect the greatest maximum

integration of students in the system? A. The schools were lo

cated in such a way as to house the youngsters, Mr. Chambers,

not to effect a maximum amount of integration.

“ Q. You did not attempt to do it? A. We made an attempt to

house the youngsters in the neighborhood.” (132a)

* * * *

“ Q. And I think that on your drawing board right now are

plans to build more schools that are going to be all white and

some that will be all black. A. I ’m sure that the enrollment in

the schools will be affected by the neighborhood served.” (129a)

8

to and since Brown. (Plaintiffs’ Ex. 1 in original record;

127a-129a). Even at the time of the March 1969 hearing

the board was proceeding with construction of a new

junior high school (Carmel Road) which under the board’s

most recent attendance zone plan would have been 100

per cent white (512a (designated “ Project 600” ), 747a).

Additionally, the board has added mobile units in order

to accommodate any influx of black or white students in

the segregated schools rather than redraw attendance dis

tricts and assign either black or white students to schools

of the opposite race (Pis’. Ex. 1 in original record). De

fendants have controlled school districts in order to limit

the race of students assigned to the various schools (Com

pare Pis’. Exs. 1, 4, 24). As the court noted in its Opinion

and Order of June 20, 1969:

“ [I]t may be timely to observe and the court finds

as a fact that no zones have apparently been created

or maintained for the purpose of promoting desegre

gation ; that the whole plan of ‘building schools where

the pupils are’ without further control promotes seg

regation; and that certain schools, for example Bill-

ingsville, Second Ward, Bruns Avenue and A may

James obviously serve school zones which were either

created or which have been controlled so as to sur

round pockets of black students and that the result

of these actions is discriminatory. These are not

named as an exclusive list of such situations, but as

illustrations of a long standing policy of control over

the makeup of school population which scarcely fits

any true ‘neighborhood school’ philosophy.” (455a-

456a) (see also note 5, supra; 132a).

Transportation has been arranged for students in order

to perpetuate segregation. Even through the 1964-65 school

1 ear, the board continued racially overlapping bus routes.

9

For students in the city and its immediate environs, black

schools have been located within convenient walking dis

tance of black residential areas. White schools have gen

erally been located in outlying white residential areas

necessitating bus transportation. Thus of the 23,384 stu

dents provided transportation during the 1969-70 school

year only 541 of such students were transported to black

schools (1014a-1032a, 1203a-1204a). Coupled with these

practices the school board continued freedom of choice to

permit those students enclosed within school districts of

the opposite race to transfer to other schools where their

race would be in the majority.

2. Urban Renewal. Urban renewal has contributed to

the residential segregation by relocating black families

from urban renewal areas to black residential areas or

areas rapidly changing to black. Principally, all of the

black families relocated by the city urban renewal pro

grams, principally all of which have taken place since

1960, have been relocated in black residential areas and

the few white families who have been relocated have been

relocated in white residential areas. A similar practice has

prevailed in the relocation of families uprooted by new

streets and highways (209a-214a, 282a-283a; Plaintiffs’

Exhibit 42). The court characterized this practice as

follows:

Under the urban renewal program thousands of Ne

groes were moved out of their shotgun houses in the

center of town and have relocated in low rent areas

to the west. This relocation of course involved many

ad hoc decisions by individuals and by city, county,

state and federal governments. Federal agencies

(which hold the strings to large federal purses) re

portedly disclaim any responsibility for the direction

of the migration; they reportedly say that the selec

tion of urban renewal sites and the relocation of dis

10

placed persons are matters of decision ( “ freedom of

choice” !) by local individuals and governments. This

may be correct; the clear fact however is that the

displacement occurred with heavy federal financing

and with active participation by local governments,

and it has further concentrated Negroes until 95% or

so of the city’s Negroes live west of the Tryon-railroad

area, or on its immediate eastern fringe (297a-298a).

The record demonstrates, however, that even this reloca

tion did not afford the affected families a “ free” choice

for, as indicated below, homes in other areas were simply

not available to black families (Plf. Exhs. 14, 19, 42 in the

original record; 28a-64a, 208a-215a, 282a-283a). Moreover,

with the overcrowding of schools which resulted from the

relocations, the school board simply added additional

rooms to existing black schools to accommodate the black

students.

3. Public Housing. Consistent with the city’s zoning

practices of locating multi-family and low income housing

in black residential areas, all public housing, built prin

cipally since 1960 and now generally occupied by blacks,

has been located in black residential areas. Even pro

jected public housing has been designated for black resi

dential areas (Plf. Exhs. 14, 19, 29 and 42 in original

record; 215a-217a). The effects of such practices in per

petuating segregated housing is seen even in the most

recent plan directed by the district court where three of

the elementary schools and one of the junior high schools,

projected to be predominantly white, have since the begin

ning of this school year become predominantly black be

cause of the relocation of additional black families in

federally financed, low-income housing in black residential

areas of the four school districts (Reply Brief App 10a-

15a).

11

4. City Zoning. City zoning lias influenced separation

o f the races by marking out and designating by land usage

those areas of the city occupied by blacks and those occu

pied by whites. Beginning in 1947, the city enacted its

first zoning ordinance and in effect delineated the black and

white residential areas. All white residential areas were

zoned residential with restricted land usage. All black

residential areas, with the exception of two small pockets

adjacent to white residential areas, were zoned industrial

for multi-land usage, including heavy industry, multi

family homes and high density areas. Even the two ex

cepted black areas were zoned for higher density use than

the white residential areas (174a, 202a-207a, 251a, 268a,

272a-283a). This difference in zoning practices for black

and white residential areas has been carried forward to

the present day in the major revisions of the zoning ordi

nance in 1962.

Industrial zones have continued to be restricted to black

residential areas. Additionally, the residential zoning au

thorized for the black areas in the 1962 zoning ordinance

has been limited to high density zones, R-6 and R-9 requir

ing 6,000 square feet and 9,000 square feet, respectively,

for a single family home. No black residential area in the

City today has a higher density zoning than R-9 while

principally all white residential areas have restricted zon

ing of R-12, R-15 or above (206a-208a; Plf. Exh. 10 in

original record (maps showing present zoning for city of

Charlotte)). As testified by plaintiffs’ witness during the

March 1969 hearing, the effect of such zoning makes the

land in the black residential areas accessible to other

uses; permits the rapid deterioration of the quality of the

land—“ and this is clearly evident from the amount of

industrial development which has taken place in areas of

Negro residences;” reduces the housing value; and intro

duces blighted and noxious usages into the area (204a).

12

It delineates for governmental and private developers,

school officials and home buyers and renters those areas of

the city for blacks and those for whites.

5. City Planning. City planning has further enforced

segregation in housing. In a comprehensive proposal in

1960 entitled “ The Next Twenty Years” (Plf. Exh. 12 in

the original record), the City Planning Commission pro

posed the continuation of basically the same racially dis

criminatory zoning practices with high density and multi

land usage in black residential areas and restricted zoning

in the white residential areas. While the proposal itself,

absent approval by the City Council, should have no con

trolling effect, it nevertheless provided the blueprint for

developers of what land usage would be permitted in the

future. As plaintiffs’ witness testified:

The only elements of the plan which develop any com

pelling force are those elements which relate to facili

ties or land uses which are normally provided by

government, things such as roads, or public buildings.

Quite naturally, the development of residential or

industrial land is subject to the decision-making of

private developers within, of course, whatever the legal

constraints are which the city imposes. But the plan

very definitely sets a direction in the recoommenda-

tions which it develops and it’s those recommendations

which are particularly significant in this case (188a).

# # *

This planning document [“ The Next Twenty Years” ]

was developed in 1960 so that this is the major impact.

The secondary effect of this document is the proposed

interstate highway system and the major arterial

streets in the Charlotte area. And again one can see

that the major north-south route—1-77—tends to re

inforce this north-south division by running adjacent

13

to and parallel to the industrial band which runs

through the city [separating the black residential area

on the west from the white residential area on the east]

(195a, 196a).

The Planning Commission’s proposal was largely en

acted by the City Council in the revised zoning code of

1962 (202a, 220a).

6. Streets and Public Highways. Streets and public high

ways have perpetuated barriers between the races. Streets

have been designed to provide ease of communication only

within the separate white or black residential areas with

little means of communication between them. Additionally,

one of the major federally financed interstate routes now

being constructed through the city, the North-South Ex

pressway (1-77), further marks, along with the Tryon

Street-Southern Railroad, the division between the racially

separate areas (195a, 216a-217a; Plf. Exh. 13 in original

record).

7. Private Discrimination. Private discrimination has

been pervasive in establishing and perpetuating the racially

segregated housing that exists in the city. Blacks simply

have been denied access or the right to purchase or rent

in white residential areas. Construction firms and real

estate agents and banking institutions, including the fed

eral government, have planned and developed racially seg

regated areas. As the court below noted (1264a), such

developments were perpetuated by racially restrictive cove

nants which were enforced by the North Carolina Supreme

Court until this Court’s decision in Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948). See, e.g., Phillip v. Wearn, 226 N.C..

290, 37 S.E. 2d 895 (1946); Eason v Buff aloe, 198 N.C.

520, 152 S.E. 496 (1930); Vernon v. R. J. Reynolds Realty

Co., 226 N.C. 58, 36 S.E. 2d 710 (1946). Such develop

ments have been followed by the school board with con

14

struction of new schools “ to house the youngsters in the

neighborhood.” (132a) Black areas or developments have

been purposely located west of the Tryon Street-Southern

Railroad dividing line and white developments on the

east side of the dividing line. Prior to the 1968 Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §§3601 et seq., real estate agents

were bound by their code of ethics to perpetuate this

policy of discrimination (Plf. Exhs. 33, 34, 35, 36 in origi

nal record; 28a-57a, 282a-283a). Limitations on the ability

and freedom of blacks to purchase and rent homes in other

areas of the city continue today.6

The school board now proposes to engraft on this

segregated system, district and housing pattern zones

which would leave the majority of the black and white

students in racially segregated schools (See projected

enrollment under board’s plan of February 2, 1970, 744a-

748a). The pervasiveness of the state practices in creat

ing and perpetuating the housing patterns and segregated

schools is no different than the former constitutional pro

visions compelling racial separation in public schools. It

is clearly illusory to contend otherwise for the black stu

dents in the all black and predominantly black schools

would be locked into those schools just as effectively and

with as much state control as they were under the former

compulsory system rejected in Brown. Cf. Brewer v.

School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, 41-42 (4th

Cir. 1968). The district court addressed this problem in

its Memorandum Decision and Order of August 3, 1970.

“ The principle difference between New Kent County,

Virginia, and Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, is

6 A black family which moved into a home in a white residential

area of the city on September 4, 1970 was intimidated and

threatened repeatedly and nightriders fired shotgun blasts into

their home while the family was asleep. Charlotte Observer, Sept.

5, 1970, at 1A.

15

that in New Kent County the number of children being

denied access to equal education was only 740, where

as in Mecklenburg that number exceeds 16,000. I f

Brown and New Kent County and Griffin v. Prince

Edward County and Alexander v. Holmes County are

confined to small counties and to “ easy” situations,

the constitutional right is indeed an illusory one. A

black child in urban Charlotte whose education is be

ing crippled by unlawful segregation is just as much

entitled to relief as his contemporary on a Virginia

farm.” (Br. A10)

Additionally, the court noted that the issue involved here

is not the validity of a “ system” but the rights of indi

vidual people:

I f the rights of citizens are infringed by the system,

the infringement is not excused because in the abstract

the system may appear valid. “ Separate but equal”

for a long time was thought to be a valid system but

when it was finally admitted that individual rights

were denied by the valid system, the system gave

way to the rights of individuals.” (Br. A13)

The court again noted that “ the essence of the Brown

decision is that segregation implies inferiority, reduces

incentive, reduces morale, reduces opportunity for asso

ciation and breadth of experience, and that segregated edu

cation itself is inherently unequal.” (Br. A15)

Testing results which the court had noted in previous

orders (see Order of August 15, 1969, 579a, 586a-590a;

Opinion and Order of December 1, 1969, 698a, 702a-706a;

Supplemental Findings of Fact of March 21, 1970, 1198a,

1206a) further substantiated the adverse effect that ra

cially segregated schools have on black children in the

Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system.

16

It was this record o f state imposed segregation which

led the court to reject any finding of de facto or consti

tutionally benign racially segregated schools and housing

in the Charlotte-Mecklenberg system. The Fourth Circuit

held these findings to be “ supported by the evidence” and

accepted “ them under familiar principles of appellate re

view.” (264a).

It is these facts and findings which required that appro

priate steps be taken by the school board to disestablish

the state imposed segregated system.

Several lower court decision have held that school offi

cials under these circumstances may not perpetuate seg

regated schools under the guise of a neighborhood system.

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) cert. den. 396 U.S. 940 (1969);

United States v. Greenivood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) cert. den. 395 U.S.

907 (1969); United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969), cert. den. 396

U.S. 1011 (1970); Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board,

423 F.2d 1132 (5th Cir. 1970); United States v. Board of

Education of Baldwin County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir.

1970); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills

borough County, 427 F.2cl 874 (5th Cir., No. 28643, May

11, 1970); Ross v. Eckels, ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir. No.

30080, Aug. 25, 1970); Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F.2d 851 (8th

Cir. 1970); United States v. School District, 151 of Cook

County, Illinois, 286 F Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1968), affirmed

404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968); Dowell v. School Board of

Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) affirmed

375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, den., 387 U.S. 931

(1967); Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, 303 F.

Supp. 79 (D. Colo. 1969).

17

Such holdings are based on the long established princi

ple that a state may not evade the prohibition of the

Fourteenth Amendment by engrafting neutral, or otherwise

unobjectionable practices upon constitutionally objection

able ones, where the effects would perpetuate constitutional

deprivations. See, e.g., Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268

(1939); Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. City of Phila

delphia, 353 U.S. 230 (1957); Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960); cf. Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969), affirming 288 F. Supp. 678 (D.D.C. 1968). See

also Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Educ., 394 F.2d

410 (4th Cir. 1968), affirming 273 F. Supp. 289 (E.D.N.C.

1967); Local 189, Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969); pp. 32-34 Brief

Amicus Curiae for the National Education Association.

II.

The Assignment Plan Now in Effect Is Workable and

Desegregates the Schools.

The school board urges here that the pupil assignment

plan it offered to the district court on February 2, 1970,

which has been rejected in every respect by both courts

below, should have been approved. We have discussed

at some length in our brief on the merits the court directed

plan which is now in effect and the majority board plan.7

7 The board plan is actually the plan of five of the nine members

of the board. Four members of the board offered an alternative

plan for the complete desegregation of the system at the July, 1970

hearing. Judge McMillan found that plan acceptable, but the board

chose to implement the plan which had been directed on February

5, 1970 (BR. A letseq.).

18

We respond here only to respondents’ discussion in sup

port of their plans for junior and senior high schools,

matters not directly addressed by our brief on the merits.

The Junior High School Plan. The board’s principal

attack on the present assignment plan as ordered by the

court is that it employs the technique of satellite zones

while under the hoard plan all students would be assigned

to a school within a zone which surrounds their school.

The hoard therefore says that its plan maintains the

“neighborhood school” concept. The court-ordered plan,

it says, does not. We have previously demonstrated that

the neighborhood school theory cannot be supported in

history and tradition as a justification for continued

segregation because it was widely and invariably dis

regarded in order to promote segregation.8 Moreover, a

comparison of the two plans shows that the board’s argu

ments are entirely spurious.

At the junior high school level the court ordered plan

draws zones around the twenty-one schools. In addition

some smaller zones (satellites) are made in the black inner-

city area which do not surround any schools. The black

children in these zones are assigned to nine of the 21

junior high schools ;9 12 of the schools have no satellites.10

(See Bespondents-Cross Petitioners’ Brief Appendix, Map

7.) The board’s plan includes no satellites. (See Respon

8 See Brief for Petitioners, pp. 80-83. See also, Opinion and

Order, April 23,1969, 305a-306a.

9 There are satellites for Eastway, Cochrane, Wilson, MeClint-

lock, Albemarle Road, Carmel (sometimes referred to as P-600),

Smith, Quail Hollow and Alexander Graham (sometimes referred

to as “A.G.”).

10 The schools without satellites are: Alexander, Coulwood, Ran-

son, Northeast (sometimes referred to as J. H. Gunn, Wilgrove or

P-601), Williams, Northwest, Spaugh, Kennedy, Sedgefield, Pied

mont, Hawthorne and Randolph.

19

dents’-Cross-Petitioners’ Brief Appendix, Map 6.) How

ever, the board would leave 842 black children in Piedmont

Junior High, a racially identifiable school (830a). This

would nearly double the number of black students at Pied

mont from the 1969-70 school year (Ibid). The board’s

justification for leaving a segregated black junior high

school is its adherence to what it calls the neighborhood

school concept. We suppose a neighborhood school means

that the children who attend the same school are “neigh

bors.” A close examination of the board’s maps shows that

the white and black children attending the junior high

schools are as much “neighbors” under one plan as under

the other.

The board zones are drawn so that there are corridors

which lead into and include portions of the black community

in order to integrate the formerly white schools.11 Pour

o f the five predominantly black schools were dealt with by

extending the zones to include white areas. (Id. Map. No.

g)ua ]rjve 0f the predominantly white schools under the

board’s plan would remain nearly all-white (830a).12

The court ordered plan, on the other hand, eliminates

the board’s corridors leading from black neighborhoods

to white schools and simply assigns the black students

to the outlying white schools. In fact, some of the same

students residing within satellites of five of the schools

would be assigned to the same school under the board

plan.13 Other black children were assigned from satellite

11 See, e.g., Coulwood, Ranson, Cochrane, Eastway, Wilson, Sedge-

field, Smith and Randolph.

lla See, e.g., Hawthorne, Kennedy, Northwest, and Williams.

12 Albemarle Road, McClintock, Quail Hollow and the two schools

opened for the 1970-71 year, Carmel (P-600) and Northeast (re

ferred to variously as J. H. Gunn, Wilgrove and P-601).

13 Smith, Eastway, Cochrane, Wilson, and Alexander Graham

(A.G.).

20

zones in the central city to predominantly white schools

not desegregated by the board’s plan. Under both plans

black children are assigned to outlying schools and white

children are assigned to formerly black inner-city schools.

The principal difference in technique therefore between

the plans is that the court ordered plan does not have

connecting corridors between the white schools and the

black areas. The principal difference in result is that

court’s plan is effective, complete and stable while the

board’s plan is limited, incomplete and is subject to the

problems of resegregation.14 We offer the following addi

tional commitments about the board’s connecting corridors

and the administrative workability of the plans.

The board’s connecting corridors bear no relationship

to any conceivable neighborhood concept nor any relation

ship to any natural landmarks such as major thorough

fares. Therefore, the transportation system would be

considerably more complex under the board’s plan than

under the plan adopted by the court. Judge McMillan

emphasized this point in the Supplemental Findings of

Fact of March 21, 1970:

“ Two schools may be used to illustrate this point.

Smith Junior High under the board plan would have

a contiguous district six miles in length extending 4%

miles north from the school itself. The district

throughout the greater portion of its length is one-

14 This is emphasized by the board’s Interim Report on Desegre

gation, of September 23, 1970 (printed as an appendix herein, 10a-

15a), which describes a developing problem of resegregation at

Spaugh caused by new public housing projects. The board’s limiting

requirement that all students must reside within a zone surrounding

a school would make it impossible to deal effectively with this situa

tion caused by the policies and actions of governmental officials.

By using the techniques of the court-ordered plan, the board can

control the population at Spaugh so that it does not become a

racially identifiable black school.

21

half mile wide and all roads in its one-half mile width

are diagonal to its borders. Eastway Junior High

presents a shape somewhat like a large wooden pistol

with a fat handle surrounding the school off Central

Avenue in East Charlotte and with a corridor extend

ing three miles north and then extending at right

angles four miles west to draw students from the

Double Oaks area in northwest Charlotte. Obviously

picking up students in narrow corridors along which

no major road runs presents a considerable trans

portation problem.

The Finger plan makes no unnecessary effort to

maintain contiguous districts, but simply provides for

the sending of busses from compact inner city atten

dance zones, non-stop, to the outlying white junior

high schools, thereby minimizing transportation tie-

ups and making the pick-up and delivery of children

efficient and time-saving. (1210a-1211a).

The district judge’s finding was supported by the testimony

of the court consultant15 and the superintendent of

schools :16

Dr. Self, the school superintendent, and Dr. Finger,

the court appointed expert, both testified that the

transportation required to implement the plan for

junior highs would be less expensive and easier to ar

range than the transportation proposed under the

board plan. The court finds this to be a fact. (1210a).

He concluded his analysis of the plan in the following w ay:

In summary, as to junior high schools, the court finds

that the plan chosen by the board and approved by the

16 957a-958a.

16 803a-804a.

22

court places no greater logistic or personal burden

upon students or administrators than the plan pro

posed by the school board; that the transportation

called for by the approved plan is not substantially

greater than the transportation called for by the board

plan, that the approved plan will be more economical,

efficient and cohesive and easier to administer and will

fit in more nearly with the transportation problems

involved in desegregating elementary and senior high

schools, and that the board made a correct adminis

trative and educational choice in choosing this plan in

stead of one of the other three methods (1211a-1210a).

The Senior High School Plan. The board also complains

about the approval by the courts below of the satellite zone

for Independence High School from which 300 black chil

dren are assigned to a school which would have had only

23 blacks enrolled under the board plan. Judge Butzner

in approving this portion of the plan observed that:

The transportation of 300 high school students from

the black residential area to suburban Independence

School will tend to stabilize the system by eliminating

an almost totally white school in a zone to which other

whites might move with consequent “ tipping” or re

segregation of other schools (1273a).

He also noted that the non-stop bus trips for these students

compares favorably in terms of distance with the trans

portation of other students assigned to Independence “ and

is substantially shorter than the systems average one-way

trip of 17 miles” (1273a, n. 6).

The distance involved is also substantially equivalent

to the distance to be traveled under the board’s high school

23

plan by inner-city black students assigned to South Meck

lenburg, East Mecklenburg, and West Mecklenburg and

by which students are assigned to the formerly all-black

West Charlotte School. (See Respondents-Cross-Peti-

tioners’ Brief Appendix, Map No. 8.)

Moreover, the children living within the Independence

satellite zone would, under the board’s plan, be assigned

to Harding and West Mecklenburg high schools serving

the area which the board reports is experiencing greater

black enrollment than expected at the elementary and

junior high school levels because of recently completed

public housing.17 . If the 300 black children now going to

Independence were, instead, going to Harding and West

Mecklenburg, we would expect that the board would be re

porting the anticipated resegregation at the high school

level which they now expect at Spaugh Junior High School.

Spaugh now has a 38.4% black enrollment. Under the board

plan the combined enrollment at Harding and West Meck

lenburg High Schools would be 39% black.18 The combined

enrollment is now only 31% black. Presumably the forces

which the board expects to create resegregation at Spaugh

Junior High School, if not corrected, including the antici

pated early occupancy o f 240 additional public housing

units at Little Rock Homes would also have had the same

effect upon Harding and West Mecklenburg High School

if the district court had not required the assignments to

Independence.

17 See appendix to this brief, 10a-15a.

18 This figure is computed by adding 300 black students to the

September 23, 1970 enrollments reported at Harding and West

Mecklenburg.

24

III.

The School Board Proposes No Viable Rule of Law

to Define the Goal of a Unitary System.

The board asks this Court to “ give instruction and guid

ance to school hoards” as to the requirements of a unitary

school system. (Brief of Respondents p. 32; hereinafter

referred to as “Brief” ) They offer, however, no standard

or rule which would clarify the law.

The school hoard’s position, as we understand it, is that

the legal conclusions drawn by the Fourth Circuit are cor

rect (Id. p. 36). The hoard supports the court’s rule of

reasonableness (Ibid.) which was stated as follows:

“ [SJchool hoards must use all reasonable means to inte

grate the schools in their jurisdictions.” (1267a)

The hoard does not seem to deny that it has some affirma

tive duty to desegregate.19 Indeed, it quotes with approval

19 Respondents are not clear as to what they view as their minimal

obligations to desegregate. They claim that “In formulating its

plan, the Board to a very significant degree has elected to exceed

Constitutional requirements” (Brief, p. 80). However, we do not

understand them to adopt the position of several of the amici that

a unitary system is created by engrafting upon a dual school sys

tem an ostensibly neutral geographic assignment plan, which leaves

racial segregation intact. Amicus Curiae Brief for the Classroom

Teachers Association of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School System,

Incorporated; Amicus Curiae Brief of the State of Florida; cf.

Amicus Curiae Brief of William C. Cramer, et al. Such a position

clearly conflicts, we think, with the decisions of this Court in Brown

v Board of Education, supra; Green v. Country School Board of

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Com-

mmumers, 391 U.S. 450 (1968); Raney v. Board of Education,

3. 1 U.S. 443 (1968); United States v. Montgomery County Board

of Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ; Dowell v. Board of Education

of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, 396 U.S. 269 (1969) and

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970). The other

circuits are in agreement with the court below that a dual school

25

the conclusion of the court that smaller school districts are

required to desegregate completely: “All schools in towns,

small cities, and rural areas generally can be integrated

by pairing, zoning, clustering or consolidating schools and

transporting pupils.” (1267a quoted at p. 36, Brief for Re

spondents).

In our brief on the merits we have criticized the “ reason

able means” test (pp. 58-65) on the ground that it is a sub

jective standard which portends a new era of litigation and

which sanctions a great deal of continuing segregation.

The board’s position underscores what we have said. They

would have this Court adopt the rule of the Court of Ap

peals, but reject its application to the facts of this case.

The board thus argues that its affirmative duty to eliminate

the vestiges of segregation would be satisfied by its de

segregation plan of February 2 (726a-748a) even though

more than one-half of the black children would still be at

tending racially identifiable black schools because it says

its plan employs all reasonable means. In concluding their

brief, the hoard asserts that the means they have chosen

are reasonable because their choices represent the “value

judgments of the elected school hoard and the educators or

its administrative staff” {Id., at 100).

At bottom, the board is arguing that locally elected

school hoards must be vested with the discretion to deter

mine not only the means hut also the extent of desegrega-

system is not dismantled by simply drawing zone lines which leave

racial segregation in the schools undisturbed. See, e.g., Henry v.

Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District supra; Mannings v.

Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, supra; Boss

v. Eckels, supra; see analysis of Fifth Circuit’s “Neighborhood

School” concept in Brief for Petitioners Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, O.T. 1970, No. 436; United States

v. School District, 151 of Cook County, Illinois, supra; United

States v. Board of Education, School District No. F, Tulsa, Okla.,

------ F.2d ------ (10th Cir. 1970). We therefore do not address

further the arguments of the above amici.

26

tion which is to occur within their jurisdictions. This plea

for school board discretion is echoed in several amicus

curiae briefs filed in this case. Brief for the Commonwealth

of Virginia, Amicus Curiae, p. 27; Brief of the City of

Chattanooga, Tenn., Amicus Curiae, p. 28; Amicus Curiae

Brief of David E. Allgood, An Infant etc., et al., p. 13.S0

I f the constitutional rights of black children to a de

segregated school are to he left to the best judgments of

local school hoards, then, of course, many of the legal

problems will he solved. A unitary school system would be

whatever a local school board determines it to be. It would

also, almost inevitably, be a segregated school system.

Judge Sobeloff spoke to the matter of school board dis

cretion in his dissent below:

In making policy decisions that are not constitutionally

dictated, state authorities are free to decide in their

discretion that a proposed measure is worth the cost

involved or that the cost is unreasonable, and accord

ingly they may adopt or reject the proposal. This is

not such a case. Vindication of the plaintiffs’ constitu

tional rights does not rest in the school board’s discre

tion as the Supreme Court authoritatively decided six

teen years ago and has repeated with increasing

emphasis (1288a).

The board offers no rule which would resolve the questions

which it claims need answers,51 other than its request that

N Some of these amici seem also to argue for a “ colorblind" test

of the variety described in the preceding footnoote.

51 The State of Florida. Governor Claude R. Kirk. Jr.. The Com

monwealth of Virginia. The Chattanooga Board of Education, the

Concerned Ciurens of Norfolk. Virginia and the Classroom Teachers

Amciatiun o f the Charlotte Mecklenburg School System. Inc., as

tM h earw, join In respondents insistence that there are important

questions to be answered. We perceive no viable answers in their

27

the discretionary decision of school boards be honored by

the courts. We cannot believe that these crucial constitu

tional rights are to be left to a majority vote.

The school board offers no viable definition of a unitary

school system. The Fourth Circuit’s reasonable means test

is “ inherently ambiguous” (1289a) and is “ a new litigable

issue” which, as the board’s brief makes clear would he

“ exploit[ed] . . . to the hilt.” (1290a). Petitioners urge

this Court to reject the reasonableness test either as an

nounced in the court below or as would be further limited

by the school board. The only thing certain about “ reason

ableness” as a standard in this context is that it sanctions

a significant amount of continued segregation in the public

schools.

Petitioners find no warrant in Brown or its progeny for

any standard or test which at the outset assumes that

segregation will remain. We submit that a dual school

system must he required to reorganize so that every black

child is to he free from assignment to a racially identifiable

“black” school, at every grade of his education. The only

exception to this general rule would be where eliminating

all black schools is absolutely unworkable.* 22 The plan or

submissions. They would either have the Court adopt a “ color

blind” standard which would leave segregation intact (see note, 20,

supra, and accompanying text) or a rule placing great emphasis on

school board discretion (see note 19, supra, and accompanying text.)

22 See the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan in Carter v.

West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 290, 292 (1970).

See also the dissenting opinion of Judge Sobeloff below:

Of course it goes without saying that school boards are not

obligated to do the impossible. Federal courts do not joust at

windmills. Thus it is proper to ask whether a plan is feasible,

whether it can be accomplished ( 1284a).

28

dered by the district court in this case accomplishes the

goal23 which we urge. And it works.24

IV.

The District Court Was Correct in Not Attempting

to Declare a General Rule of Law to Govern the Multi

tude of Varied Circumstances of School Segregation in

Other Cities and Other Parts of the United States.

The school board’s brief suggests that Judge McMillan

relied upon grounds to support his desegregation order

which would apply to Chicago (or other large northern

cities) as well as to Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The board

thereby attempts to precipitate this Court into considera

tion of the enormously complicated problem that is some

times termed “ de facto” school segregation.25 The Court

is neither required nor able to consider that problem in

this case.

Judge McMillan did not base his order on general prin

ciples applicable out of the context of classical school

segregation under state segregation laws and practices—

de jure segregation—nor, indeed, upon broad principles of

23 See Brief for Petitioner, Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 0. T. 1970, No. 436, pp. 63-49, for a full

discussion of the general principle we ask this Court to announce.

24 See Report, etc., which is printed as an Appendix to this Brief,

4a-9a (showing enrollment in the schools as of September 21, 1970).

25 We think the labels “ de facto” and “ de jure” are somewhat

unhelpful and confusing because the terminology tends to beg the

question at issue, i.e., whether the government is responsible for

the segregation to a sufficient extent that the Fourteenth Amend

ment prohibits its continuance. The terminology tends to assume

that there is a distinction between the causes of segregated schools

in tlie North as opposed to the South. That is a question which

must in the final analysis be decided in the concrete circumstances

of cases which present the issues.

29

any sort applied out of the context of the particular school

system of Charlotte. What Judge McMillan did, as he

was legally and realistically obliged to do was to consider

all of the factors in the Charlotte situation that were

relevant to determining whether the school board had ful

filled its obligations under Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954), and, if not, what steps were neces

sary to require it to fulfill those obligations.

That is also the only question before this Court. Noth

ing in this case obliges the Court to consider questions of

so-called de facto segregation, for in this case we deal with

an archetype of de jure segregation and a question of the

proper remedies for it.

Prior to 1954, public schools in Charlotte-Mecklenburg

were segregated pursuant to the state constitution and

laws of North Carolina. Judge McMillan’s opinion of Au

gust 3, 1970, attaches as an appendix the elaborate code

of segregation laws adopted in North Carolina, including

about sixty-five sections of the General Statutes and two

sections of the Constitution. (This exhibit of the segrega

tion laws has not been printed in the appendices, but is

contained in the original record attached to the opinion of

August 3, 1970.) Under this segregation code racial segre

gation of pupils and faculties and all aspects of the system

was complete. A dual system of schools for whites and

Negroes was maintained throughout the state under the

compulsion of these laws. As Judge McMillan has noted

many of these laws were still on the books in North Car

olina when his April 23,1969, opinion was written, although

many were repealed thereafter by the 1969 General A s

sembly.

Although segregation in schools was unconstitutional

from 1954 to 1970, as a practical and a legal matter, racial

segregation has continued in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

30

schools through the 1969-1970 school year. The board main

tained until June 1969 a pupil assignment system based

on geographic zones and freedom of transfer which was

substantially the same as that held unconstitutional by this

Court in Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson,

Tenn., 391 U.S. 450 (1968). Thus Judge McMillan found

last year that the 9,216 pupils “ in 100% black situations

are considerably more than the number of black students

in Charlotte in 1954 at the time of the first Brown decision”

(661a). Judge McMillan has been addressing a problem

of how to desegregate all-black schools in Charlotte which

remained in the pre-1954 pattern.

In determining whether the promise of Brown I that

such segregation would be eliminated “ root and branch”

is applicable, Judge McMillan and this Court should prop

erly give weight to the impact of all factors which operate

within the school system of Charlotte-Mecklenburg to bring

about its present condition or enable its change. It was

for this reason that Judge McMillan considered—and we

invite this Court to consider—such matters as housing

demographic patterns effected by public housing, urban

renewal, city zoning, racial restrictive covenants enforced

by state laws, and by school planning decisions (school loca

tion, school size, grade structure, school attendance areas,

etc.). All of these factors are related in determining the

school system that Charlotte has today, and in appraising

whether it meets the requirements of a desegregated sys

tem. Judge McMillan recognized, as this Court must, that

the present system is the result of many factors. For ex

ample, decisions about whether to build schools, where to

build schools, and the capacity of the schools to be built,

shape neighborhood and demographic patterns over many

years. Now that the schools have shaped the neighborhood,

Judge McMillan reasonably took the view that a school

system was not meeting its obligation to desegregate if it

31

now permitted the neighborhoods to shape the schools. The

neighborhoods to which respondents advert as the basis of

the “neighborhood school principle” are themselves the

product of state planning and state action of many sorts,

by the board of education and other state organs over many

years. One can no more say that a neighborhood school

principle in this setting achieves desegregation because it

is “color blind” than one could sustain the operation of

“color blind” Grandfather Clauses used by many states to

perpetuate voting discrimination after this Court voided

more obvious forms of denying black citizens the franchise.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939).

But this does not mean that any of the factors considered

by Judge McMillan here urged on this Court would have

the same significance in another context, particularly with

relation to a different question: for example, the question

whether the City of Chicago has an unconstitutionally seg

regated school system in the first instance. This Court

should be exceedingly cautious in indulging the assumption

suggested by respondents that Chicago does pose the same

— or indeed a different—problem than does Charlotte. We

simply do not know, respondents do not know, and the

Court does not know what problems Chicago may pose.

One thing that the Court does know is that school deseg

regation problems are very complex, and arise against the

full, complicated factual situations in different localities.

What appears to be “ de facto” in one context may be “de

jure” in another. It is wholly inappropriate for the Court

to decide this case in light of fears or concerns as to how

problems in Chicago might be resolved, when there is not

now a record before the Court suggesting either what the

issues in Chicago might be or what the full set of com

plicated factual circumstances in Chicago, relevant to those

issues, are.

32

y .

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Does Not in Any W a y

Limit the Power of the Courts to Fashion Remedies

for Unconstitutional Racial Segregation in Public

Schools or Prohibit the Courts from Requiring Busing

of Pupils to Disestablish Dual Segregated School

Systems.

The school board and some of the amicus curiae have

argued that two provisions of the Civil Rights Act of

1964—sections 401(b) and 407(a), codified as 42 U.S.C.

§§2000c(b)28 and 2000c-6(a)27—justify reversal of the dis- * 1 2 * * * * *

28 §2000e. Definitions

As used in this subchapter—

# # #

(b) “Desegregation” means the assignment of students to

public schools and within such schools without regard to

their race, color, religion, or national origin, but “desegre

gation” shall not mean the assignment of students to public

schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.

Pub.L. 88-352, Title IV, §401, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat 246.

27 §2000c-6. Civil actions by the Attorney General— Complaint;

certification; notice to school board or college

authority; institution of civil action; relief re

quested; jurisdiction; transportation of pupils to

achieve racial balance; judicial power to insure

compliance with constitutional standards; im

pleading additional parties as defendants

(a) Whenever the Attorney General receives a complaint in

writing—

(1) signed by a parent or group of parents to the effect

that his or their minor children, as members of a class of

persons similarly situated, are being deprived by a school

hoard of the equal protection of the laws, or

(2) signed by an individual, or his parent, to the effect

that he has been denied admission to or not permitted to

continue in attendance at a public college by reason of race,

eolor, religion, or national origin,

and the Attorney General believes the complaint is meritorious

and certifies that the signer or signers of such complaint are

33

trict court’s desegregation plan. The board’s brief argues

that the Civil Eights Act of 1964 “ expressly prohibits a

United States Court to order transportation to achieve

racial balance in schools” (School Board brief herein,

Argument I.-E-4). This audacious effort to convert the

Civil Eights Act into a sword against school desegrega

tion has been rejected by every court of appeals which

has been confronted with the argument, including the

decision below by Judge Butzner (A. 1274a). See peti

tioners’ brief herein at pp. 65-66 and cases cited. Judge

Butzner concluded for the court below:

Those provisions are not limitations on the power of

school boards or courts to remedy unconstitutional

segregation. They were designed to remove any im

plication that the Civil Eights Act conferred new juris

diction on courts to deal with the question of whether

unable, in his judgment, to initiate and maintain appropriate

legal proceedings for relief and that the institution of an action

will materially further the orderly achievement of desegrega

tion in public education, the Attorney G-eneral is authorized,

after giving notice of such complaint to the appropriate school

board or college authority and after certifying that he is satis

fied that such board or authority has had a reasonable time to

adjust the conditions alleged in such complaint, to institute

for or in the name of the United States a civil action in any

appropriate district court of the United States against such

parties and for such relief as may be appropriate, and such

court shall have and shall exercise jurisdiction of proceedings

instituted pursuant to this section, provided that nothing herein

shall empower any official or court of the United States to issue

any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by

requiring the transportation of pupils or students from one

school to another or one school district to another in order to

achieve such racial balance, or otherwise enlarge the existing

power of the court to insure compliance with constitutional

standards. The Attorney General may implead as defendants

such additional parties as are or become necessary to the

grant of effective relief hereunder.

# * #

Pub.L. 88-352, Title IV, §407, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 248.

34

school hoards were obligated to overcome de facto

segregation (1274a).

The board’s argument is entirely untenable because it

is in conflict with the plain language of the Civil Rights

Act and with the legislative purpose of the Congress.

The language of section 407(a) makes it clear that the

relevant proviso was added merely to insure that the law

was not interpreted to enlarge the powers of the federal

courts. There is no language in the section which prohibits

the courts from doing anything. Section 407 authorizes

the attorney general to institute school segregation cases

in the name of the United States in the federal courts

upon receiving complaints of aggrieved citizens that they

were “ deprived by a school board of the equal protection

of the laws.” The section provides that the United States

may sue “ for such relief as may be appropriate” and that

the appropriate district courts “ shall have and shall exer

cise jurisdiction of proceedings instituted pursuant to this

section.” Immediately after this grant of jurisdiction over

suits brought by the attorney general, section 402 states

the proviso that the board relies on, which says that

nothing therein empowers any official or court of the

United States “ to issue any order seeking to achieve a

racial balance in any school by requiring the transportation

of pupils or students from one school to another or one

such school district to another in order to achieve such

racial balance, or otherwise enlarge the existing power of

the court to insure compliance with constitutional stan

dards” (emphasis added).

There is simply nothing in this language that prohibits

the federal courts from doing anything. It certainly does

not forbid anything the courts find necessary to “ insure

compliance with constitutional standards” (section 407).

35

The whole purpose of §407 is to enable the federal govern

ment to institute suits to “ further the orderly achievement

of desegregation in public education” by enforcing the

Equal Protection Clause through suits in the federal courts.

The proviso applies only to suits instituted pursuant to

the section—that is, where the federal courts exercise the

jurisdiction conferred to entertain school desegregation

cases instituted by the attorney general. The provision has

no application whatsoever to this Charlotte school case

which was not instituted by the attorney general but was

filed by petitioners who invoked the district court’s juris

diction under 28 IT.S.C. §1343 to enforce their rights under

42 IJ.S.C. §1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment. The

United States is not even a party to this case. Section 409

of the Act (42 U.S.C. §2000c-8) provides that “Nothing in

this title shall affect adversely the right of any person to

sue for or obtain relief in any court against discrimination

in public education or in any facility covered by this title.”

Thus, the Congress made plain that any limitation placed

on suits brought by the attorney general would not “ ad

versely affect” suits brought by private litigants.