Jones v. Alabama Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Alabama Brief for Appellant, 1971. 3b57905f-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15952333-aecd-43b8-892d-507d8c0a16de/jones-v-alabama-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

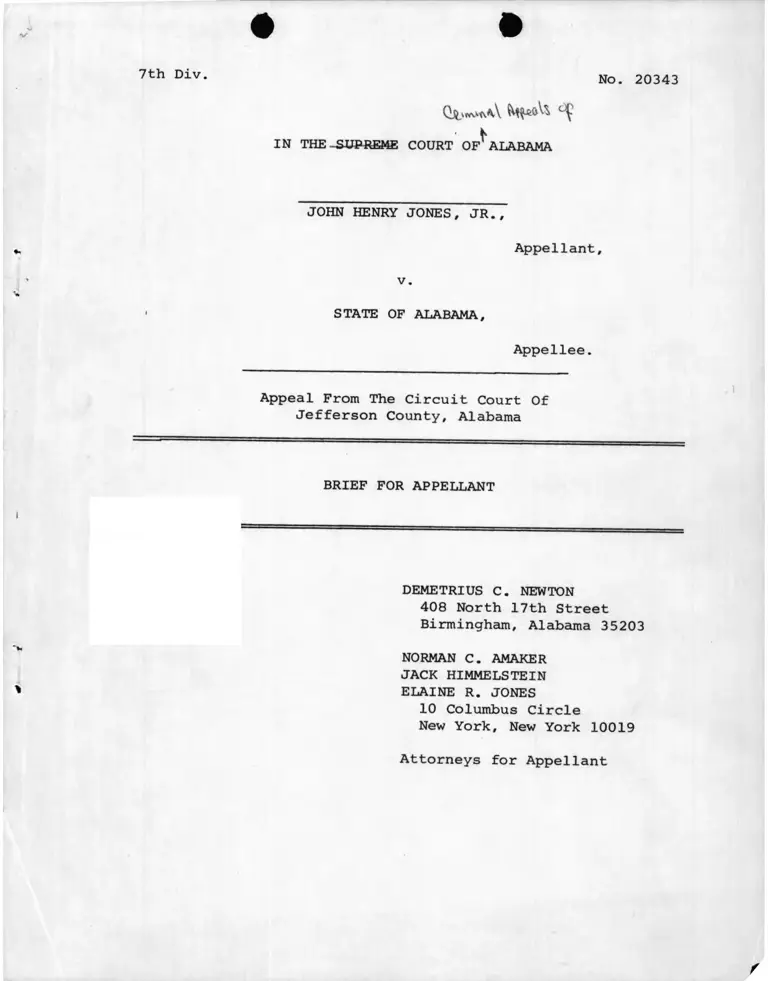

7th Div. No. 20343

IN THE -SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

JOHN HENRY JONES, JR.,

Appellant,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Appellee.

Appeal From The Circuit Court Of

Jefferson County, Alabama

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

NORMAN C. AMAKER

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

INDEX

STATEMENT OF THE CASE---------------------------------

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS--------------------------------

I. MUCH EVIDENCE SUGGESTING RAPE INCLUDING

BOTH INCOMPETENT TESTIMONY AND OTHER

DEMONSTRATIVE AND DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

SUGGESTING RAPE WAS ALLOWED IN APPELLANT'S

TRIAL FOR ROBBERY----------------------------

II. THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO SUSTAIN

THE VERDICT IN FACT AND LAW------------------

A. There Was Variance Between The Indict

ment and The Evidence--------------------

B- Admission Allegedly Made By Appellant Uhder Extremely Coercive Circumstances

Before Being Charged With The Crime

Of Robbery Was Admitted Into Evidnece----

III. THE VOIR DIRE IN EXCLUDING VENIREMEN SCRUPLED AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY DID NOT SUBSCRIBE

TO THE GUIDELINES PROVIDED IN WITHERSPOON v.

ILLINOIS-------------------------------------

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW----------------------------------

ARGUMENT

I. APPELLANT'S CONVICTION SHOULD BE REVERSED

BECAUSE THE COURT ERRED IN ADMITTING

EVIDENCE SUGGESTING RAPE AND ASSAULT

WITH INTENT TO MURDER WHICH WAS EXTREMELY PREJUDICIAL AND INFLAMMATORY IN APPELLANT'S

TRIAL FOR ROBBERY-------------------------

A. Evidence Suggesting Rape and Assault

With Intent to Murder Should Have Been Declared Inadmissible Because

Such Evidence Was Not Embraced in

Appellant's Indictment For Robbery----

B. The Evidence Was Extremely Prejudicialand Inflammatory, Thus Constitutes

Reversible Error----------------------

Page

II. IN THE ALTERNATIVE THE JURY SHOULD HAVE

RECEIVED AN INSTRUCTION THAT EVIDENCE

SUGGESTING OTHER CRIMES SHOULD ONLY GO

TO THE QUESTION OF GUILT AND NOT TO THE

ISSUE OF PUNISHMENT. APPELLANT SUBMITS

THE COURT"S FAILURE TO GIVE SUCH AN INSTRUCTION CONSTITUTES REVERSIBLE ERROR------

III. THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO SUSTAIN

THE VERDICT OF GUILTY OF THE CRIME OF ROBBERY BOTH IN FACT AND IN LAW. THEREFORE,

APPELLANT'S CONVICTION MUST BE SET ASIDE------

A. There Was Variance Between The Indict

ment and the Evidence---------------------

B. The Introduction Into Evidence of the Incriminating Highly Prejudicial Admission

(R. 244-53) Allegedly Made By Appellant

to Authorities Before Being Apprised of

the Charges Against Him, and Made Involun

tarily When He Was Without Counsel Violates

Appellant's Fifth Amendment Privilege

Against Self-Incrimination. Its Intro

duction Into Evidence Therefore Constitutes

Reversible Error--------------------------

IV. APPELLANT'S CONVICTION SHOULD BE REVERSED

BECAUSE THE EXCLUSION OF PERSONS WITH

CONSCIENTIOUS SCRUPLES AGAINST THE DEATH

PENALTY FROM SERVICE ON THE JURY VIOLATED

THE RIGHTS OF APPELLANT UNDER THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND IS CONTRARY TO THE RULE ENUNCIATED

IN WITHERSPOON v. ILLINOIS--------------------

V. THE ABSENCE OF PROCEDURAL STANDARDS FOR ADMINISTERING CAPITAL PUNISHMENT FOR THE

CRIME OF ROBBERY PURSUANT TO TITLE 14 §415 OF THE CODE OF ALABAMA WHICH AUTHORIZES

THE IMPOSITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR THE

CRIME OF ROBBERY COUPLED WITH THE ALABAMA

PROCEDURE OF SIMULTANEOUSLY SUBMITTING THE

ISSUES OF GUILT AND PUNISHMENT TO THE JURY

IS PROHIBITED BY THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT, THE EIGHTH AMEND

MENT'S PROHIBITION AGAINST CRUEL AND UNUSUAL

PUNISHMENT AND BURDENS FIFTH AMENDMENT

PRIVILEGES. THE VERDICT, JUDGMENT AND

SENTENCE PROCURED PURSUANT TO THIS TITLE

SHOULD THEREFORE BE REVERSED------------------

17

18

18

20

23

28

ii

Page

A. The Alabama Statute Title IV §415 Is

Unconstitutional On Its Face In That It

Sets No Standards For The Imposition Of

The Death Penalty. The Jury Has Un

limited And Unfettered Discretion To

Impose The Death Penalty In No Way Guided

By Standards Or Principles Of General

Application Which Would Defeat Arbitrari

ness---------------------------------------- 29

B. Alabama’s Single-Verdict Procedure Of

Submitting Both The Issues Of Guilt

And Punishment To The Same Jury At The

Same Time Bears Heavily On The Discrimi

natory Capital Sentencing In This Case

and Violates Appellant's Fifth Amend

ment Privilege------------------------------ 33

VI. APPELLANT'S DEATH SENTENCE CONSTITUTES CRUEL

AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT IN VIOLATION OF THE

EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES---------------------------- 39

CONCLUSION----------------------------------------------- 40

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Aaron v. State, 271 Ala. 70, 122 So.2d 360 .............. 13

Argo v. State, 43 Ala. App. 564, 195 So.2d 901 (1967) . . 31

Baker v. State, 19 Ala. App. 437, 97 So. 9 0 1 ............ 9,13

Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 7 8 .................... 9

Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1969)................ 10, 25

Bowman v. State, 208 So.2d 241 (1968) .................. 9, 12

Brasker v. State, 249 Ala. 36, 30 So.2d 3 1 .............. 12

Crampton v. Ohio, No. 1633, O.T. 1969, 38 U.S.L.W.

3478 (1970).................................... 30

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ............ 10, 21,22

Ex parte Carson, 17 Ala. App. 345, 85 So. 827 .......... 9, 12

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961)................ 36

Frady v. United States, 348 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1965) . . . 37

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966)............ 10, 29

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) .............. 10

Green v. United States, 365 U.S. 301 (1961) ............ 36

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965).............. 36

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 .................. 39

Harden v. State, 211 Ala. App. 656, 101 So. 442 . . . . 9,12,13

Harris v. State, 212 So.2d 695 (1968) .................. 9, 12

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 .......................... 10

Higginbotham v. State, 262 Ala. 236, 78 So. 2d 637 (3 965) . 9, 17

In re McLeod, 23 Ida. 257, 128 P. 1106.................. 9,18

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961)................ .. 22

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964).................. 10

/

iv

Cases (Cont'd) Page

Lovely v. United States, 169 F.2d 386 (4th Cir. 1948) . . . 38

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964) .................... 21, 36

Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 ( 1 9 5 9 ) .......... 38

Marvin v. United States, 279 F. 2d 4 5 1 .................... 18

Mason v. State, 259 Ala. 438, 66 So.2d 557 (1953) ........ 9,12

Maxwell v. Bishop, 90 S.Ct. 1578 ...................... 10,25

McGautha v. California, No. 1632, O.T. 1969, 38 U.S.L.W.

3478 (1970) .................................... 31

Metower v. Simpson, 294 F. Supp. 1134 (M.D. Ala. 1969) . . 31

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)............. 5, 10, 20,22

Ralph v. Warden (4th Cir. No. 13,757, Dec. 11, 1970). . 10,32,33

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963) 22

Roberts v. State, 183 N.W. 555 (1921).................... 15

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) 10,33,39

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 .......................... 10

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966)................ 23

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 ........................ 39

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968) ........ 10,35,36

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ................ 10, 35

Smarr v. State, 260 Ala. 30, 68 So. 2d 6 . . . .■.......... 9,17

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967) 10,35

State v. Minton, 234 N.C. 716, 68 S.E.2d 844 21

Thompson v. State, 24 Ala. App. 300, 134 So.2d 679 . . . . 9,12

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 (1965)................ 23

United States v. Beno, 324 F.2d 582 (2d Cir. 1963) . . . . 38

United States v. Curry, 358 F.2d 904 (2d Cir. 1965) . . . . 37

/

v

Cases (Cont'd)

Page

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 ................ 10,35,37

United States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F.2d 311

(3rd Cir. 1962) .................................... 38

United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Banmiller, 310 F .2d

720 (3rd Cir. 1962) ................................ 38

Untreiner v. State, 146 Ala. 26, 41 So. 285 (1906) ........ 25

Weatherspoon v. State, 36 Ala. App. 392, 56 So.2d 793 . . . 9,13

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) .............. 33

Wilson v. State, 268 Ala. 8 6, 105 So.2d 66 (1958) . . 9,12,13,16

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) . . 3,10,24,25,26,27

Wright v. People, 104 Colo. 335, 91 P.2d 499 .............. 9,18

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) .................. 30

Statutes:

Alabama Code, Recomp. 1958, Title 14, § 395 18

Alabama Code, Recomp. 1958, Title 14, § 415 ........... 28,29,32

Alabama Code, Recomp. 1958, Title 15, §§ 382 (1-13) . . . . 1

Alabama Code, Recomp. 1958, Title 30, § 57 ................

I

vi

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

JOHN HENRY JONES, JR.,

Appellant,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Appellee

Appeal from the Circuit Court of

Jefferson County, Alabama

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal comes to this Court under the provisions of

the automatic appeal statute, (Title 15, §382, subsection 1

through 13 inclusive, Alabama Code of 1940, Pocket Part) from

the Circuit Court for the 10th Judicial Circuit, Birmingham,

Alabama, Honorable John J. Jasper, Circuit Judge.

Appellant is John Henry Jones, Jr., a Negro man convicted

in May 1970 in the Birmingham Circuit Court on a jury verdict

of the crime of robbery of a white girl. His sentence was

fixed at death by electrocution.

After being indicted for robbery, appellant was duly

arraigned and pled not guilty and not guilty by reason of

insanity. Later, in Chambers with the Court, the court

reporter, and all attorneys present, appellant withdrew his

plea of not guilty by reason of insanity. Trial was had before

a jury which found him guilty of robbery and fixed his punish

ment at death. The sentence of the court was in accordance

with the verdict of the jury. He duly filed a motion for a

new trial which he later amended. The motion was overruled.

Appellant also filed a motion for leave to appeal in forma

pauperis which motion was granted. In his motion for a new

trial and now in this his direct appeal, appellant alleges the

unconstitutionality of his conviction for the following reasons

(1) Appellant's conviction should be reversed because the

court erred in admitting evidence suggesting rape and assault

with intent to murder which was extremely prejudicial and

inflammatory in appellant's trial for robbery (R. 61, 67, 6 8 ,

69-71, 72-82, 105, 106-108, 109, 111, 113, 220).

(2) Evidence suggesting rape and assault with intent to

murder should have been declared inadmissible because such

evidence was not embraced in appellant's indictment for robbery

(R. supra).

(3) In the alternative the jury should have received an

instruction that evidence suggesting other crimes should only

go to the question of guilt and not to the issue of punishment

(R. supra).

(4) The evidence was insufficient to sustain the verdict

of guilty of the crime of robbery both in fact and in law

(R. 55, 1, 50, 190, 279, 456).

2

(5) There was variance between the indictment and the

evidence (R. supra).

(6 ) The introduction into evidence of the incriminating

highly prejudicial admission (R. 244-53) allegedly made by

appellant to authorities before being apprised of the charges

against him and made involuntarily when he was without counsel

violates appellant's Fifth Amendment privilege against self

incrimination.

(7) Appellant's conviction should be reversed because

the exclusion of persons with conscientious scruples against

the death penalty from service on the jury violated the rights

of appellant under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the Uhited States and is contrary to the rule enunciated in

Witherspoon v. Illinois (R. 17-24, 32-33, 35).

(8 ) The Alabama Statute, Title IV, §415 is unconstitu

tional on its face in that it sets no standards for the

imposition of the death penalty. The jury has unlimited and

unfettered discretion to impose the death penalty in no way

guided by standards or principles of general application which

would defeat arbitrariness (R. 457).

(9) Alabama's single-verdict procedure of submitting

both the issues of guilt and punishment to the same jury at

the same time bears heavily on the discriminatory capital

sentencing in this case and violates appellant's Fifth

Amendment privilege. (R. 450-458)

3

(10) Appellant's death sentence constitutes cruel and

unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment and

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

By successive orders of the circuit court, the time for

filing the transcript of the proceedings below in this Court

was stayed until December , 1970 and by order entered this

Court on January , 1971, appellant was granted 15 additional

days to file his brief up to and including January 21, 1971.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

I.

MUCH EVIDENCE SUGGESTING RAPE INCLUDING

BOTH TESTIMONY AND OTHER DEMONSTRATIVE

AND DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE SUGGESTING RAPE

WAS ALLOWED IN APPELLANT'S TRIAL FOR ROBBERY

Beginning with the direct examination of the prosecutrix

hy the State, there is evidence throughout the record suggesting,

hinting and in some instances alleging the commission of other

offenses by appellant. Defense counsel strenuously objected to

evidence suggesting rape, but there is also much evidence

indicating assault with intent to murder.

Prosecutrix (R. 61) testified that her money was first

taken by appellant. There is further testimony from prosecutrix

(R. 61) that appellant requested she remove her clothes.

There is further testimony (R. 63-69 inclusive) elicited

from prosecutrix on direct that there was a prolonged struggle

with appellant (all occurring after he allegedly had taken the

money, of his allegedly dragging her, pulling off her clothes,

4

and discharging a gun. Later during the direct examination

of prosecutrix over the objection of defense counsel, the

court permits testimony as to the alleged rape (R. 70) and

there is additional testimony as to a threatened sodomous act.

Throughout the remainder of the testimony of the prosecutrix

(R. 72-87) appellee questioned her vigorously but did not

elicit any testimony about the alleged stolen watch (item in

the indictment) until after prosecutrix had made detailed

allegations not included within the scope of the indictment

(R. 88).

Also articles of the prosecutrix' wearing apparel worn

during her alleged ordeal were admitted into evidence (R. 102-

114 inclusive). Defense counsel excepted on the ground this

demonstrative evidence - of bras, panties, culottes - had no

bearing on the crime of robbery charged in the indictment.

A statement that appellant allegedly made to the authorities

which was transcribed was received in evidence (State's exhibit

XX - R. 244-253 inclusive). In this written instrument (R. 245)

when receiving the Miranda warnings, appellant is expressly

told he is in jail on a charge of rape. This written instru

ment was considered by the jury in its deliberations.

II.

THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO SUSTAIN

THE VERDICT IN FACT AND LAW.

A. There was variance between the indictment and the evidence.

The indictment (R. 1) alleges appellant feloniously took

5

a ladies* gold watch valued at twenty-eight dollars and also

took thirty dollars in cash.

Yet most of the evidence suggests other offenses not

embraced in the indictment. On direct examination of prose

cutrix appellee elicits testimony suggesting rape (R. 65-72)

and alleging various degrees of assault.

The only evidence as to appellants allegedly taking thirty

dollars from prosecutrix is found in her testimony (R. 55).

There is no other evidence in the record as to this money.

Also prosecutrix testified that appellant took her watch (R. 8 6 ).

There is no evidence in the record that appellant was ever

seen with such a watch or that he ever had this particular

watch.

However, when appellant was arrested, direct examination

of the arresting officer revealed a pawn ticket for a watch

was found on him (R. 204). Further testimony attempts to

establish a link between appellant and the particular watch

taken from the alleged victim.

The officer testified he secured the watch from the pawn

shop (R. 207) and prosecutrix earlier identified the watch

secured as her watch (R. 8 8).

The pawnbroker testified he did not know the appellant

at all (R. 187) but the person who had pawned the watch had

signed the appellant's name. There was evidence from the

state toxicologist that there were "good points of reproduction

between appellant's handwriting and the signature on the pawn

ticket." (R. 279). There was no positive evidence that

6

appellant had even seen or pawned the watch of the prosecutrix.

B. Admission allegedly made by appellant under extremely

coercive circumstances before being charged with the

crime or robbery was admitted into evidence.

There was a written instrument introduced (R. 244) allegedly

a statement made by appellant on the night of his arrest (R. 256-

260). The evidence shows appellant was (cross-examination of

police sergeant) arrested at 3:00 p.m. in the afternoon on an

unrelated charge. At 9:00 p.m. appellant was still without

counsel and being interrogated. At that point he was charged

with rape and at 1:30 a.m. the next morning he allegedly signed

the statement admitting some limited involvement. (See R. 244-

253) Appellant's defense at trial, however, was alibi.

Ill

DURING THE VOIR DIRE, VENIREMEN WHO WERE

SCRUPLED AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY WERE

STRUCK FOR CAUSE.

The record shows (R. 17-24, 32-33, 35) fifteen veniremen

were struck for cause because they voiced apprehensions about

the imposition of the death penalty. Each venireman was asked

if he felt beyond a reasonable doubt the defendant was guilty -

after all the evidence, then would preclude the death penalty

from any and all consideration. Only one prospective juror

(R. 37) was asked if she would consider all the forms of

punishment that the "His Honor instructs you on." And she

answered a vigorous yes.

7

NOTE: There is evidence in the record that Negroes were

systematically and arbitrarily excluded from

appellant's petit jury venire (R. 45). The defense

counsel notes for the records the prosecutor's

discriminatory use of his peremptory challenges.

8

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW

I. The three essential ingredients of the common law

offense of robbery are the use of force or violence

or by use of means whereby the person is put in

fear; the taking from the person* or from the presence of another, of money or other personal

property; and taking it with the intent to rob or steal.

THOMPSON Vo STATE, 24 Ala. App. 300, 134 So. 679

EX PARTE CARSON, 17 Ala. App. 345, 85 So. 827

WILSON v. STATE, 218 Ala. 8 6 , 105 So. 2d 66 (1958)

HARRIS v. STATE, 212 So. 2d 695 (1968)

BOWMAN v. STATE, 208 So. 2d 241 (1968)

II. The purpose of the indictment is to limit and make

specific the charges the defendant will have to face on the trial.

MASON v. STATE, 259 Ala. 438, 66 So. 2d 557 (1953)

III. Evidence of distinct and independent offenses is not

admissible on the trial of a person accused of a crime.

WEATHERSPOON v. STATE, 36 Ala. App. 392, 56 So. 2d 793

HARDEN v. STATE, 211 Ala. 656, 101 So. 442

BAKER v. STATE, 19 Ala. App. 437, 97 So. 901

IV. Evidence of separate offenses in a criminal trial is

admissible only as shedding light on the acts, motives

and intent of the accused.

HIGGINBOTHAM v. STATE, 262 Ala. 236, 78 So. 2d

637 (1955)

SMARR v. STATE, 260 Ala. 30, 68 So. 2d 6

V. There is a variance where an indictment charges a

specific offense and the proof establishes the commission of a different crime not included in the one

charged.

MARVIN v. U„ S., 279 F.2d 451

IN RE McLEOD, 23 Idaho 257, 128 P. 1106

BERGER v. U.S., 295 U.S. 78

VI. The defendant can be tried only on the charge con

tained in the indictment and not for any other offense.

WRIGHT v. PEOPLE, 104 Colo. 335, 91 P.2d 499

9

VII. If the interrogation of an individual held by police

continues without the presence of an attorney, and a

statement is taken, a heavy burden rests on the State

to demonstrate that the defendant knowingly and

intelligently waived his privilege against self-incrimi

nation and his right to retained or appointed counsel.

MIRANDA v. ARIZONA, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)

ESCOBEDO v. ILLINOIS, 378 U.S. 478 (1964)

GIDEON v. WAINWRIGHT, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)

VIII. Exclusion from juries of persons scrupled against

capital punishment is unconstitutional.

WITHERSPOON v. ILLINOIS, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)

BOULDER v. HOLMAN, 394 U.S. 478 (1969)

MAXWELL v. BISHOP, 90 S. Ct. 1578 (1970)

IX. Unfettered discretion to impose the death penalty

violates Due Process of Law.

HERNDON V. LOWRY, 301 U.S. 242 GIACCIO v. PENNSYLVANIA, 382 U.S. 399

RALPH v. WARDEN (4th Cir. 1970)

SKINNER v. OKLAHOMA, 316 U.S. 535

X. Use of the single verdict procedure whereby a jury

simultaneously determines guilt and sentence violates

Due Process of Law.

JACKSON v. DENNO, 378 U.S. 368 (1964)

U.S. v. JACKSON, 390 U.S. 570

SIMMONS v. U.S., 390 U.S. 377 (1968)

SPECHT v. PATTERSON, 386 U.S. 605

XI. Imposition of the death penalty for robbery is cruel and unusual punishment.

ROBINSON v. CALIFORNIA, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)

RUDOLPH v. ALABAMA, 375 U.S. 889

RALPH v. WARDEN (4th Cir. 1970)

BEDAU, THE DEATH PENALTY IN AMERICA

10

ARGUMENT

I.

APPELLANT'S CONVICTION SHOULD BE REVERSED

BECAUSE THE COURT ERRED IN ADMITTING EVIDENCE

SUGGESTING RAPE AND ASSAULT WITH INTENT TO

MURDER WHICH WAS EXTREMELY PREJUDICIAL AND

INFLAMMATORY IN APPELLANT'S TRIAL FOR ROBBERY.

A . Evidence Suggesting Rape and Assault With Intent To

Murder Should Have Been Declared Inadmissible Because Such Evidence Was Not Embraced In Appellant's

Indictment For Robbery.

During appellant's trial for robbery, the court admitted

evidence embracing charges other than the one included in the

indictment. There was testimony by the prosecutrix over

objection that appellant asked her to remove her clothes

(R. 61); there was further testimony the appellant was pull

ing at the clothes of prosecutrix (R. 67) and that he pulled

her panties off and broke the zippers to her garments (R. 6 8).

There was further testimony of consummated rape and an alleged

threat by appellant to force the prosecutrix to commit the

act of sodomy (R. 69-71). Also there was extensive testimony

by the prosecutrix, over objection of defense counsel of

repeated attempts by appellant to run over her with a car

(R. 72-82).

Appellant was indicted for robbery — such crime being

of thirty dollars ($30.00) and a ladies gold-filled watch

valued at thirty-eight dollars ($38.00), a common law offense

11

1/in Alabama with three essential ingredients which constitute

the crime; the use of force or violence, or by use of means

whereby the person is put in fear; the taking from the person,

or from the presence of another, of money or other personal

property; and, taking it with the intent to rob or steal.

Thompson v. State, 24 Ala. App. 300, 134 So. 679; Ex parte

Carson. 17 Ala. App. 345, 85 So. 827; Wilson v. State. 268

Ala. 8 6, 105 So.2d, 66 (1958), Harris v. State, 212 So.2d,695

(1968); Bowman v. State, 208 So.2d, 241 (1968).

These are the essential ingredients the State must

prove beyond a reasonable doubt in order to secure a robbery

conviction, and a lengthy exaggerated excursion into other

distinct and separate offenses allegedly committed by appel

lant are clearly not within the scope of the indictment.

The purpose of the indictment is to limit and make

specific the charges that the defendant will have to face on

the trial. Mason v. State. 259 Ala. 438, 66 So.2d, 557

(1953). In a criminal trial the defendant is entitled to

have an indictment charging specific crimes. Brasker v.

State, 249 Ala. 96, 30 So.2d, 31; Harden v. State. 211 Ala.

656, 101 So. 442.

1/ The court also permitted the introduction of the various

articles of clothing prosecutrix wore before and during her

alleged attack, sweater-vest (R. 105), undergarments (R. 106-

108, 111) pants and blouse and skirt (R. 109) remainder of

blouse (R. 113). It also became a part of the record that at the time the accused received the required Miranda warnings

appellant was charged with the rape of the prosecutrix (R. 220).

12

The general rule in Alabama is that evidence of distinct

and independent offenses is not admissible on the trial of a

person accused of a crime. Weatherspoon v. State. 36 Ala. App.

392, 56 So.2d, 793; Harden v. State, supra; Baker v. State,

19 Ala. App. 437, 97 So. 901. Recognizing the exception under

which evidence of offenses which are part of the same con-

27tinuous transaction is admitted as part of the res qestae,

appellant respectfully submits this is not such a case for

the applicability of the res qestae exception to the general

rule.

In a criminal trial, especially a capital offense, courts

clearly have a duty to safeguard the fundamental rights of

the accused and jealously protect the presumption of innocence

to which he is entitled. The right of the defendant to know

the nature of the charges against him, to have a copy of the

charges, and to have a trial by jury in a criminal trial are

basic rights afforded appellant by both the Constitution of

3/ 4/the United States and the Constitution of Alabama. Any

procedure or rule which encroaches upon these rights should

be closely scrutinized and discarded, if not needed, to ensure

justice.

2/ Wilson v. State. 268 Ala. 8 6, 105 So.2d 6 6, (1958)

3/ U. S. Const, amend. VI.

4/ Ala. Const. 1901, art. 1 §6

13

Having made the choice to indict appellant on a charge

of robbery, the State should be made to abide by it. It is

not as if it is foreclosed from bringing additional charges

if the evidence so warrants. However, the State should not

be allowed to ride to judgment on a hybrid, especially in a

case in which the very life of the accused is in jeopardy.

There is a perimeter encircling this res qestae excep

tion to the admissibility of evidence of separate and distinct

crimes. Appellant contends the circumstances of the instant

case fall outside of that perimeter. Appellee sought a con

viction on the charge of robbery; the court should limit the

evidence to proof of the ingredients of robbery and no more.

To permit the tate to do indirectly (actually try defendant

on a charge of rape) what it alone refrained from doing

directly is to run roughshod over appellant's rights by

surprising him during trial, rendering his prepared defense

ineffective, and unduly prejudicing the trier of fact against

him while he sits in the court of law, surprised, shocked and

helpless.

B. The Evidence Was Extremely Prejudicial And Inflamatory

And Thus Constitutes Reversible Error.

In the preceding section the unduly prejudicial portions

of the record are noted (p. 1, supra). It is appellant's

submission that all of the evidence suggesting rape and

assault with intent to murder is so prejudicial as to require

14

a reversal of appellant's conviction. Especially is this

true when viewed in light of Alabama's single-verdict pro

cedure — simultaneously submitting both the issue of guilt

and punishment to the jury.

Appellant's primary contention is that all of the evi

dence documentary, demonstrative and testimonial — suggesting

other crimes is per se inadmissible.

The presumption of innocence to which a defendant is

entitled may give way to the respect and sympathy naturally

felt by any tribunal for a female allegedly wronged, or to

the unreasoning rage which many feel toward one accused of

both violence and indecency. "Public sentiment seems pre

inclined to believe a man guilty of any illicit sexual offense

he may be charged with. . . . " Roberts v. State, 106 Neb.

362, 367; 183 N.W. 555, 557 (1921). Because the crime of

rape, even if not proved but merely alleged, arouses emotions

as do few others, it should be tried as a separate offense

in which there are certain procedural safeguards built in for

the accused such as corroboration. An alleged crime, such

as rape, which usually evokes a powerful sentimental emotional

human response toward the victim should not be used as a

catalyst to secure a conviction and capital penalty in a com

pletely different offense. Requirements of due process forbid

such a procedure.

An additional ground which makes the procedure unlawful

surfaces when viewing it in the context of Alabama's single

verdict procedure. If, by some chance the admission of this

15

evidence falls within Alabama's res qestae exception to the

general rule, it remains an unlawful procedure. The same

jury that convicts also punishes in single-verdict juris

dictions. However, even where there is the more favorable

split-verdict procedure, the bifurcated trial giving the

accused a fair trial as to both the issues of guilt and

punishment, this evidence of alleged additional offenses

should not be admitted. However, if admitted, the second

jury — the one determining the punishment — would never

hear this evidence.

This Court has said, "all the details of one continuous

criminal occurrence . . . may be considered by the jury in

passing on the culpability . . . of the crime for which the

party is being tried." Wilson v. State. 105 So.2d, 6 6, 69.

Therefore, even under the res qestae exception this Court

has noted that this evidence of "other crimes" only goes to

the question of guilt. But when there is a single jury, how

can it help from also being influenced by this inflammatory

evidence even on the penalty issue? And this is what has

happened to appellant. The upshot of it all is that contrary

to all the precepts of justice, he was tried, convicted and

sentenced for an alleged offense against which he was never

permitted to defend.

16

II.

IN THE ALTERNATIVE THE JURY SHOULD HAVE

RECEIVED AN INSTRUCTION THAT EVIDENCE

SUGGESTING OTHER CRIMES SHOULD ONLY GO

TO THE QUESTION OF GUILT AND NOT TO THE

ISSUE OF PUNISHMENT. APPELLANT SUBMITS

THE COURT'S FAILURE TO GIVE SUCH AN IN

STRUCTION CONSTITUTES REVERSIBLE ERROR.

If, in the alternative, the court decides the afore

mentioned portions of the record constitute admissible evidence

as part of the res qestae of the charge convicted of robbery,

then appellant contends he was entitled to a jury instruction

informing the jury as to the law in using this evidence suggesting

other crimes.

The jury should have been instructed that any evidence of

rape, assault with intent to murder or any other distinct and

separate offenses should only be considered on the question of

guilt of the charge convicted of, robbery. Such evidence was

admissible only as shedding light on the acts, motive and intent

of the accused. Higginbotham v. State, 262 Ala. 236, 78 So.2d

637 (1955); Smarr v. State, 260 Ala. 30, 68 So.2d 6 . In con

sidering the penalty issue, the jury should have received

express direction from the court that evidence of other crimes

should not be considered in fixing appellant's punishment for

robbery, if convicted. Failure to instruct the jury in this

manner was prejudicial error and therefore appellant's convic

tion should be reversed.

17

III.

THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO SUSTAIN

THE VERDICT OF GUILTY OF THE CRIME OF

ROBBERY BOTH IN FACT AND IN LAW. THERE

FORE APPELLANT'S CONVICTION MUST BE SET

ASIDE.

A. There Was Variance Between The Indictment And The

Evidence.

There is a variance where an indictment charges a specific

offense and the proof establishes or seeks to establish the

commission of a different crime not included in the one charged.

Marvin v. U.S., 279 F.2d 451, In Re McLeod, 23 Idaho 257, 128 P.

1106. The defendant can be tried only on the charge contained

in the indictment. . . and not for any other offense. Wright v.

People, 104 Colo. 335, 91 P.2d 499.

In his proof appellee made an attempt to establish appel

lant's guilt as to rape even though appellant was indicted for

robbery. The State sought to prove all of the common law

elements of rape, use of force, penetration, lack of consent,

against the will. However, the State cannot show on direct

the alleged details of the occurrence. Aaron v. State, 271 Ala.

70, 122 So. 2d 360. Appellee was able to circumvent the

procedural problems by seeking a robbery conviction with all

the circumstances of the alleged rape an entrenched part of

the record.

That is clearly material variance for neither did appellee

prove beyond a reasonable doubt the essential ingredients of

the robbery offense.

The indictment charged the appellant with feloniously

18

taking one ladies' wristwatch of the value of $38 and $30 in

currency (R. 1, 450). An essential ingredient of proof of

robbery is the taking of personal property or money from

another. The evidence failed to establish a nexus between

appellant and the items allegedly taken. The only evidence

in the record which attempts to show appellant took any money

from the prosecutrix is her statement that she handed him

thirty dollars ($30) from her purse (R. 55).

There was no evidence which would indicate someone saw

him spending a similar sum; there were no witnesses to the

alleged taking; and the record is barren of any evidence except

prosecutrix' own testimony that appellant took any money from

her.

The indictment on its face alleges a ladies watch valued

at thirty-eight dollars ($38)(R. 1, 50) was taken. No watch

of said description was found in appellant's possession nor

did anyone testify as to seeing appellant with such a watch.

A search of appellant upon his arrest revealed a pawn ticket.

The pawnbroker testified (R. 190) he could not identify the

party who pawned the watch. The toxicologist which compared

the signature on the pawn ticket to appellant's signature

testified that "there were good points of reproduction". . .

(R. 279). As to the watch the "evidence against appellant was

highly tenuous and circumstantial.

Also the court in its oral charge to the jury (R. 456)

emphasized if any one of the three essential elements of robbery

was not present, then appellant could not be found guilty of

19

robbery. Appellant submits the evidence is insufficient to

sustain his conviction for robbery.

B. The Introduction Into Evidence Of The Incriminating

Highly Prejudicial Statement Allegedly Made By

Appellant To Authorities Before Being Apprised Of

The Charges Against Him and Made Involuntarily When

_He Was Without Counsel Violates Appellant's Fifth

Amendment Privilege Against Self-Incrimination And Its Introduction Into Evidence Therefore Constitutes

Reversible Error.

There is evidence in the record supporting the contention

that upon his arrest, appellant was not afforded the protection

the law allows. The record shows appellant was arrested on a

charge other than robbery at approximately 3:00 p.m. (R. 255).

Testimony indicates he orally received the Four Miranda warnings

at the time of his arrest. Further reading of the record (R. 258)

indicates appellant was interrogated on and after from the time

of his arrest around 3:00 p.m. until 1:30 a.m. the following

morning (R. 255-260). A statement propurtedly made and signed

by appellant the night of his arrest was introduced into

evidence. The record (R. 224) also shows that at no time was

appellant advised that he was charged with robbery - not before

he allegedly made his incriminating admission nor afterwards.

If the interrogation of an individual held by police con

tinues without the presence of an attorney, and a statement is

taken, a heavy burden rests on the State to demonstrate that the

defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his privilege

against self-incrimination and his right to retained or appointed

counsel. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 u.S. 436 at 476 (1964).

20

It is appellant's submission that the statement allegedly

made by him was totally involuntary for he was without counsel,

had not been apprised of the charges against him and in a

coercive environment. " . . . unless adequate protective devices

are employed to dispel the compulsion inherent in custodial

surroundings, no statement obtained from a person held for

interrogation by a law enforcement officer can truly be the

5/product of his free choice.

Appellant's defense is alibi and "the burden of proof of

an alibi is not on the accused but it is incumbent upon the

State to show beyond a reasonable doubt on the whole evidence

that the accused is guilty. State v. Minton. 234 N.C. 716, 68

S.E. 2d 844.

The introduction of appellant's alleged statement into

evidence was extremely prejudicial to his case. Alibi was

appellant's defense and the only evidence which rebuts that

in any convincing manner is that statement. It is an admission

that he was at the scene, kidnapped and assaulted the prosecutrix.

Admitting this statement into evidence in effect was the same

as forcing the appellant to testify against himself. He did

testify in his behalf but this earlier admission he allegedly

made was in evidence and mocked his every word.

The State has the burden of proving appellant knowingly,

willingly and voluntarily waived rights guaranteed him by

5/ The introduction of this involuntary statement violates

appellant's Fifth Amendment privilege against self

incrimination. Malloy v. Hogan (1964), 378 U.S. 1, 84 S.Ct. 1489, Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, Escobedo v. Illinois,

378 U.S. 478.

21

principles of fundamental due process and voluntarily made

this statement with a full understanding of his right to

remain silent. Appellee failed to introduce any evidence which

would overcome the State's burden of showing voluntariness.

For the foregoing reasons, appellant's conviction should be

reversed.

6/ Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1964),

Illinois, 378 U.S. 478.

Escobedo v.

IV

APPELLANT'S CONVICTION SHOULD BE REVERSED

BECAUSE THE EXCLUSION OF PERSONS WITH CON

SCIENTIOUS SCRUPLES AGAINST THE DEATH

PENALTY FROM SERVICE ON THE JURY VIOLATED

THE RIGHTS OF APPELLANT UNDER THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED

STATES AND IS CONTRARY TO THE RULE LAID DOWN

** j)__ rjL C -i n p lS

1/Pursuant to the laws of the State of Alabama, persons

with conscientious scruples against the death penalty were

excluded for cause from service on the jury which convicted

and sentenced appellant. Such an exclusion violated the rights

of the defendant under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the Uhited States.

Appellant's first contention is that such an exclusion

resulted in a biased and prosecution-prone jury, unable to

accord him a fair trial on the issue of guilt, and a jury

unfairly predisposed against the selection of penalties other

than death. A fair trial by an unbiased jury on the issue of

guilt or innocence is plainly appellant's right under the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, see, e.g. Irvin v.

Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961); Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723

(1963); Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 (1965); Sheppard v.

Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966). The State may not entrust

7/ "On the trial for any offense which may be

punished capitally, or by imprisonment in the

penitentiary, it is a good cause of challenge

by the state that the person has a fixed opinion

against capital or penitentiary punishments, or

thinks that a conviction should not be had on

circumstantial evidence; which cause of challenge

may be proved by the oath of the person, or by

other evidence." Alabama Code, Title 30, §57.

23

Appellant's final contention on the scrupled-jury issue

is that such an exclusion violated appellant's right to a

fair trial on the penalty issue by denying him a representa

tive jury. This practice denied appellant a trial of the

penalty question by a body of jurors validly representative of

the community.

Witherspoon v. Illinois. 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770 (1968),

Maxwell v. Bishop, / U.S. 90 S.Ct. 1578 (1970) and Boulden

v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478, 89 S.Ct. 1138 (1969), are three com

pelling decisive authorities for the rule of law pronounced in

Witherspoon in which the Court held:

. . . that a sentence of death cannot be

carried out if the jury that imposed or

recommended it was chosen by excluding

veniremen for cause simply because they

voiced general objections to the death

penalty..10/ No defendant can constitu

tionally be put to death at the hands of a tribunal so selected.

The Alabama statute on qualifying jurors (see p. 23 » footnote

7, supra) speaks of excluding jurors with a "fixed opinion"

against capital punishment. However, as the statute has been

construed "fixed opinion" is the equivalent of "conscientious

scruples" — the statutory formulation expressly condemned by

the Supreme Court in Witherspoon. Contrary to the per se

meaning of the phrase "fixed opinion," this Court in Untreiner

v. State, 146 Ala. 26, 41 So. 285 (1906) interpreted it to mean

exclusion from jury service of one who is generally opposed to

capital punishment. Witherspoon precludes such a

10/ Ibid at p. 1777.

11/result.

The most that can be demanded of a venireman in a capital

case is that he be willing to consider all penalties provided

by state law and that he not be irrevocably committed before

trial has begun to vote against penalty of death regardless

of the facts and circumstances that might emerge in the course

of the proceedings. (Emphasis supplied)

Witherspoon expressly provides that a venireman must be

willing to consider all penalties provided by state law. The

jury is not instructed as to the penalties provided for a

particular offense until the very end of the trial. Therefore

during the voir dire, if the prosecutor asked several veniremen

as he did in the instant case if they would preclude the death

penalty from their consideration (R. 17-23, 32-33, 35) and

they respond affirmatively, this does not fully satisfy the

requirements of Witherspoon. The venireman must be asked the

11/ The Witherspoon rule applies to all capital cases in which

the jury was death-qualified pursuant to procedures which

excused for cause veniremen who stated that they had con

scientious or religious scruples against the death penalty,

or that they were opposed to or did not believe in the

death penalty, or in which they were excused in some similar

fashion that recognized a challenge on the basis of general

resistance or repugnance to capital punishment but did not

pursue the inquiry to the point of establishing, unmistakably

and affirmatively on the record, in the case of each venireman excused, either (a) that his attitudes on the death

penalty were such that he would refuse, under any possible

state of the evidence in the case before him, to return the

death penalty; or (b) that his attitudes on the death penalty

were such as to prevent his trying fairly and impartially

the question of the defendant's guilt.

26

question on the basis that the death penalty is one of the

punishments provided by law for the offense charged, in order

to provide the clear unambiguous response sought by Witherspoon.

If the venireman does not know it, that the offense charged is

punishable by death must at least be hypothesized to him in

voir dire.

Whereas when the prosecutor (R. 35) asks the venireman

if she would consider "all the forms of Punishment that His

Honor instructs you on," (emphasis supplied) he gets an imme

diate unqualified "yes." This is the only venireman that was

specifically asked if she would "consider all the forms of

Punishment His Honor instructs you on," not precluding the

death penalty. Presenting the question in this manner was a

way of clearly asking the venireman "if the death penalty is

provided by state law for this offense and you receive an

instruction on it, would you preclude it?" Appellant submits

this form of the question is in the spirit of the Witherspoon

doctrine and simply asking a venireman if he would preclude

the death penalty no matter what the circumstances does not

fully satisfy the Witherspoon requirement.

27

V.

THE ABSENCE OF PROCEDURAL STANDARDS FOR ADMINISTERING

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT FOR THE CRIME OF ROBBERY PURSUANT

TO TITLE 14 § 415 OF THE CODE OF ALABAMA WHICH AUTHOR

IZES THE IMPOSITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR THE CRIME

OF ROBBERY COUPLED WITH THE ALABAMA PROCEDURE OF SIM

ULTANEOUSLY SUBMITTING THE ISSUES OF GUILT AND

PUNISHMENT TO THE JURY IS A PROCEDURE PROHIBITED BY

THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT,

THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT'S PROHIBITION AGAINST CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT, AND BURDENS FIFTH AMENDMENT PRIV

ILEGES. THE VERDICT, JUDGMENT AND SENTENCE PROCURED

PURSUANT TO THIS TITLE SHOULD THEREFORE BE REVERSED.

What is at issue in the instant case — what appellant

does vigorously challenge — are the procedures employed by the

State of Alabama in selecting the men to die pursuant to Title

14 § 415 of the Alabama Code. Alabama's practice of allowing

capital trial juries absolute and arbitrary power to elect

between the penalties of life or death for the crime of robbery

without standards or principles of general application to guide

that choice violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Appellant's second contention is that appellee's practice

of simultaneously submitting both the issues of guilt and pun

ishment to the jury in a capital case makes it impossible for

the jury to exercise its already unlimited discretion in any

reasonable or rational fashion. Although the due process

clause guaranteed appellant a fair trial both on the issues of

and punishment, appellant was forced to give up one for

the other.

Such arbitrary sentencing power coupled with requiring

appellant to elect between fundamental constitutional rights

28

often results — as in the instant case -- in an unduly harsh

penalty totally unrelated to the factual circumstances of the

crime which clearly violates the Eighth Amendment's proscrip

tion against cruel and unusual punishment.

A. The Alabama Statute Title 14 § 415 Is Unconstitutional

on Its Face in That It Sets no Standards for the Impo

sition of the Death Penalty. The Jury Has Unlimited

and Unfettered Discretion to Impose the Death Penalty

in no Way Guided by Standards or Principles or General Application Which Would Defeat Arbitrariness.

The sentence of death imposed upon appellant was determined

by a jury which, pursuant to the laws of the State of Alabama,

has unlimited, undirected and unreviewable discretion in

determining whether the death penalty shall be imposed.

Robbery, Title 14 § 415. Any person who is convicted

of robbery shall be punished, at the discretion of

the jury, by death or by imprisonment in the peniten

tiary for not less than ten years. Code of Alabama,1940.

Thus the decision between the death penalty and lesser

alternatives is required to be made by the jury according to

whatever whims, urges, or prejudices may move it. Such caprice

to which appellant fell victim flies in the face of the Anglo-

American concept of the law. Certainly one of the basic

purposes of fundamental fairness and due process has always

been to protect a person against having the government impose

burdens upon him except in accordance with the valid laws of

12/

the land. For the very idea that one man may be compelled

12/ Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399, 403 (1966).

to hold his life, or the means of living, or any material right

essential to the enjoyment of life, at the mere will of another,

seems to be intolerable in any country where freedom prevails,

as being the essence of slavery, itself. Yick Wo v. Hopkins.

118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886).

What passes for procedure in implementing Title 14 § 415

of the Code of Alabama is merely institutionalized arbitrari

ness. The issue is that the Constitution requires there be a

lawful system for deciding which men shall live and which shall

die. The present system of saying to the jury, in effect, "kill

him if you want" or "spare him if you wish" will simply not do

in a system based on concepts of fundamental fairness, due pro

cess and equal protection.

No legal fair or uniform standards for making this

determination are set forth by statute, judicial decision or

executive pronouncement. The trial judge gave no directions or

standards for choosing among permissible sentences. Thus the

capital sentencing system established under Alabama law permits

juries to utilize illegal and unconstitutional factors in sen

tencing appellant to death and resulted in the imposition of

the death penalty arbitrarily and capriciously, in violation of

the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual

punishment and the rule of law that is the fundamental principle

of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. Crampton v. Ohio, cert,

granted, 0 .T. 1969, No. 1633, 38 U.S.L.W. 3478 (June 1, 1970),

30

McGautha v. California, cert, granted, O.T. 1969, No. 1632,

38 U.S.L.W. 3478 (June 1, 1970).

One point is clear, however; an Alabama jury's death

verdict in a robbery case is absolutely final. It may not be

reviewed or set aside by any court. And the fixing of penalty

is a power vested solely in the jury. Robbery in Alabama is

punishable by sentences from ten years' imprisonment to death.

Metower v. Simpson. 294 F. Supp. 1334 (M.D. Ala. 1969). The

punishment for robbery must be set by a jury. Argo v. State,

43 Ala. App. 564, 195 So.2d 901 (1967). It is, within statu

tory limits, the exclusive province of the jury, subject to the

power of the governor to commute a death sentence. The jury's

power is absolute.

These decisions reinforce the decisiveness and lawlessness

of the jury's unchecked, unguided power to decide between life

and death. Therefore, appellant's trial jury had the absolute

power, which it exercised, to willy-nilly decide that he should

die.

In addition to its inconsistency with the rule of law

commanded by due process, Alabama's practice of committing cap

ital sentencing to the unconstrained and undirected discretion

of a jury results in the imposition of death sentences that are,

by their nature, cruel and unusual punishments within the

Eighth Amendment. Appellant submits since there are no stand

ards enumerated by which a jury may rationally decide between

the penalties of life and death in any given case, any death

31

penalties meted out pursuant to Title 14 § 415 per se consti

tute cruel and unusual punishment.

Appellant does not take the stand that the Due Process

Clause entirely forbids the exercise of discretion in sen

tencing, evey by a jury and even in a capital case. Ways may

be found to delimit and guide discretion, narrow its scope,

and subject it to review; and these may bring a grant of discre

tion within constitutionally tolerable limits.

Appellant has been picked to die out of a group of iden

tically situated defendants convicted of the same crime and

thereupon permitted to live. The sentencing jury is not required

to consider the similarities or differences that make the cases

relevant. it may simply elect to kill him or not, as it

chooses, for any reason, or for no reason, and certainly for

no reason that need or will be applied in the case of any other

defendant.

It is appellant's contention that the Eighth Amendment's

prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment forbids appel

lant's execution for robbery since his victim’s life was not

taken nor was there serious physical harm.

Ralph v. Warden (4th Cir. 1970), held that a defendant

convicted of rape and his victim's life was neither taken nor

endangered cannot be executed for rape within the ambit of the

Constitution. A capital sentence imposed upon such circumstances

constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and therefore violates

the Eighth Amendment.

32

There are rational gradations of culpability that can be

13/made on the basis of injury to the victim. if the Fourth

Circuit finds this holds true for a convicted rapist, surely

appellant's death penalty for robbery in a situation in which

the victim's life was not take cannot be squared with the

Constitution.

The Eighth Amendment is a limitation on both legislative

14/and judicial action. Consequently, it acts as a control on

the jury's imposition of the death penalty in appellant's case

— on facts such as these. In appellant's case the imposition

of the death penalty for robbery is unduly harsh, extremely

excessive, clearly disproportionate to the crime and is there

fore constitutionally impermissible. It is a precept of

justice that punishment for a crime should be graduated and

15/proportional to the offense.

B. Alabama's Single-Verdict Procedure of Submitting Both

the Issues of Guilt and Punishment to the Same Jury

at the Same Time Bears Heavily on the Discretionary

Capital Sentencing in This Case and Violate's Appel

lant's Fifth Amendment Privilege.

Alabama's practice of submitting simultaneously to the trial

jury the two issues of guilt and punishment in a capital case

compounds the vice of lawless jury discretion by making it

virtually impossible for the jurors to exercise their discretion

13/ Ralph v. Warden, 4th Cir., No. 13,757 (Dec. 11, 1970).

14/ Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

15/ Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 367 (1910).

33

in any rational fashion. The effect of this practice is obvious

and devastatingly prejudicial to the accused. He is forced to

elect between his right of allocution and his privilege against

self-incrimination. If he wishes to personally address the

jurors who must make the decision whether he shall live or die,

he can do so only at the price of taking the stand and thereby

surrendering his privilege. He is subject not only to incrim

inating cross-examination but also to impeachment. If he

exercises the privilege, on the other hand, he risks an unin

formed and uncompassionate death verdict. Should he wish to

present background and character evidence to inform the jury's

sentencing choice, he may do so only at the cost of opening the

question of character prior to the determination of guilt or

innocence, thereby risking the receipt of bad-character evidence

ordinarily excludable and highly prejudicial on the guilt ques

tion. Or he may avoid that risk of prejudice by confining the

evidence at trial to matters relevant to guilt, letting the

jury sentence him to life or death in ignorance of his character

A jury engaged in the task of determining whether a defendant

shall live or die needs much information that cannot and should

not be put before it within the confines of traditional and

proper limitations on the proof allowable as going to guilt or

innocence.

Appellant challenges the constitutionality of this trial

procedure which needlessly burdens his Fifth Amendment privi

lege to remain silent. The Supreme Court of the United States

34

emphasized in United States v. Jackson. 390 U.S. 570 (1968), and

Simmons v. United States. 390 U.S. 377 (1968), that the exercise

of the Fifth Amendment privilege in criminal trials may not be

penalized or needlessly burdened. The jury's simultaneous con

sideration of the death penalty together with the issue of

guilt results in such a needless burden — needless because

the State has ample means to avoid it, use of the bifurcated

jury trial, judge sentencing, or the elimination of the death

penalty.

The Alabama single-verdict procedure therefore confronts

the defendant on trial for his life with a gruesome Hobson's

choice. He is subjected to an "undeniable tension," the avoid

able but unavoided conflict of one constitutional right against

another, that the Supreme Court recently condemned in a similar

setting, Simmons v. United States, supra at 394. He has a

crucial interest — amounting, indeed, to an independent federal

constitutional right, see Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535

(1942) — that his sentence be rationally determined. The Con

stitution guarantees him, also, certain procedural rights in

this sentencing process: inter alia, "an opportunity to be

heard ... and to offer evidence of his own." Specht v. Patterson,

386 U.S. 605, 610 (1967). As the basis for a rational senten

cing determination, he will often want to present to the

sentencing jurors evidence of his history, his character, his

motivation, and the events leading up to his commission of the

crime of which he is guilty (if he is guilty). The common-law

35

gave him a right of allocution which is an effective vehicle

for this purpose, as well as for a personal appeal to the jurors,

where capital sentencing is discretionary.

But to exercise his right of allocution before verdict on

the guilt issue, he must forego his constitutional privilege

against self-incrimination. Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964);

Griffin v. California. 380 U.S. 609 (1965). He mus take the

stand and be subjected to cross-examination that can incrim

inate him. Even apart from cross-examination, allocution before

verdict of guilt destroys the privilege. For much of the value

of the defendant's personal statement to his sentencer derives

from its spontaneity, see Green v. United States, 365 U.S. 301,

304 (1961) (opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter), arid this same

spontaneity — unguided by the questions of counsel — leaves

the defendant impermissibly unprotected as he appears before a

jury which has not yet decided on his guilt. Cf. Ferguson v.

Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961).

The simultaneous-verdict practice which entails these con

sequences is totally inconsistent with Simmons v. United States.

390 U.S. 377 (1968). There the Court condemned admission at

the trial of the guilt issue of the defendant's testimony on a

motion to suppress. The result of that practice was that the

accused was obliged either to surrender what he believed to be

a valid Fourth Amendment claim or "in legal effect, to waive

his ... privilege against self-incrimination." 390 U.S. at

394. Simmons held it "intolerable that one constitutional

right should have to be surrendered in order to assert another."

36

390 U.S. at 394. But, as we have shown above, that is exactly

what the capital trial practice used in appellant's case

requires.

The question in United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570

(1968), was whether the provision of the federal kidnapping

statute reserving the question of the death sentence to the

exclusive province of the jury "needlessly encourages" guilty

pleas and jury waivers and therefore "needlessly chill[s] the

exercise of basic constitutional rights." 390 U.S. at 582.

So here the question is whether the simultaneous trial of guilt

and punishment needlessly encourages the waiver of the right to

remain silent or needlessly chills the right to put in evidence

relevant to sentencing and the right of allocution. in view of

the ready availability of alternative modes of procedure ; not

involving this dilemma — for example, the split-verdict proce

dure now in use in a number of jurisdictions and uniformly

recommended by modern commentators, see Frady v. United States.

348 F.2d 84, 91, n. 1 (D.C. Cir. 1965) (McGowan, J.); cf.

United States v. Curry. 358 F.2d 904, 914 (2d Cir. 1965) —

the single verdict procedure plainly falls under the ban of

Simmons and Jackson.

A second, related and aggravating vice of this simultaneous

verdict procedure lies in the intolerably unfair choices which

it requires of a man on trial for his life. Often he must choose

between making his defense on the guilt issue or casting his

whole case in avoidance of the death penalty. if the defendant

seeks to present to the jury evidence of his background and

37

character for purposes of sentencing, the prosecution may-

counter with evidence of the defendant's bad character, includ

ing evidence of unrelated crimes. The prohibition which

ordinarily keeps this sort of evidence from the trial jury

sitting to determine the issue of guilt is "one of the most

4

fundamental notions known to our law." United States v. Beno,

324 F.2d 582, 587 (2d Cir. 1963), arising "out of the funda

mental demand for justice and fairness which lies at the basis

of our jurisprudence," Lovely v. united States. 169 F.2d 386

389 (4th Cir. 1948). See Marshall v. United States. 360 U.S.

310 (1959). Allowing the trial jury access to unfavorable

background information, however pertinent to the issue of pun

ishment and however clearly limited by jury instructions to

that use, may itself amount to a denial of due process of law.

Compare United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Banmiller. 310 F.2d 720

(3rd Cir. 1962), cert, denied. 374 U.S. 828 (1963), with United

States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F .2d 311 (3rd Cir. 1962),

cert̂ . denied, 374 U.S. 844 (1963). in any event, the possibility

that the background information will be strongly prejudicial

forces a defendant to a "choice between a method which threatens

the fairness of the trial of guilt or innocence and one which

detracts from the rationality of the determination of the sen

tence. " American Law Institute, Model Penal Code. Tent. Draft

No. 9 (May 8, 1959), Comment to § 201.6 at 74.

38

VI.

APPELLANT'S DEATH SENTENCE CONSTITUTES CRUEL

AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT IN VIOLATION OF THE

EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES.

The death sentence for the crime of robbery is so cruel

and unusual as to constitute a violation of the Eighth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States. The penalty

the loss of life without commensurate justification.

Even if applied regularly and evenhandedly, the death

penalty would violate public standards of decency, dignity and

humanity. it avoids public condemnation only by being unus

ually and arbitrarily applied (Argument V, supra). in this it

is cruel and unusual punishment within the Eighth Amendment.

Execution by electrocution also imposes physical and

psychological torture and under contemporary standards of decency

it is so cruel and unusual as to constitute a violation of the

Eighth Amendment. Robinson v. California. 370 U.S. 660;

Sfterbert v. Verner. 374 U.S. 398; Griswold v. Connecticut. 381

U.S. 479.

39

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, appellant respect

fully submits that his conviction should be reversed and the

sentence of death imposed upon him be set aside.

Appellant requests oral argument.

Respectfully submitted.

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN C. AMAKER JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELAINE R. JONES10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

40

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that on the ____ day of

January, 1971, a copy of the foregoing brief for appellant,

was served on the Hon. Earl C. Morgan, District Attorney for

the 10th Judicial Circuit by personally serving him at his

office in Birmingham, Alabama in the Jefferson County Court

house. The undersigned further certifies that he served

the Attorney General of Alabama by mailing a copy addressed

to him at his office in Montgomery, Alabama on the ---- day

of January, 1971 via United States mail, postage prepaid.

Demetrius C. Newton Attorney for Appellant