Geier v. Blanton Brief for Plaintiff-Intervenors, Appellees Richardson

Public Court Documents

January 11, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Geier v. Blanton Brief for Plaintiff-Intervenors, Appellees Richardson, 1978. 92b3070a-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15c4a958-f586-4c16-b8d0-04cc0e8daa35/geier-v-blanton-brief-for-plaintiff-intervenors-appellees-richardson. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

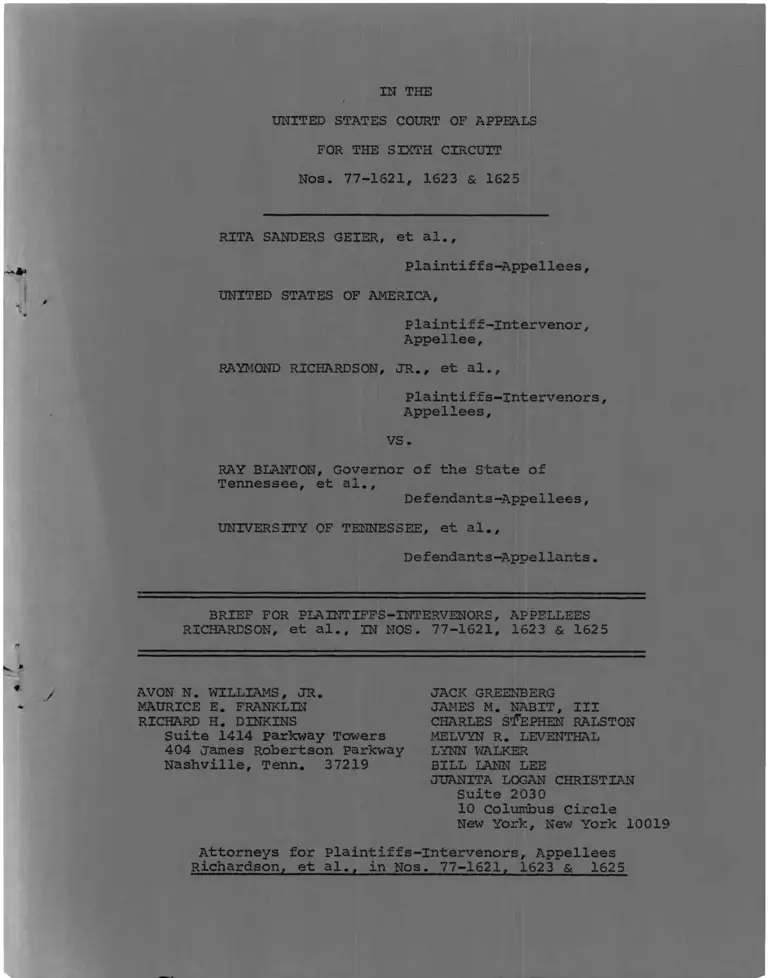

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

Appellee,

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors,

Appellees,

VS.

RAY BLANTON, Governor of the State of

Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS—INTERVENORS, APPELLEES

RICHARDSON, et al., IN NOS. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

< ‘

♦ AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE E. FRANKLIN

RICHARD H. DINKINS

Suite 1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tenn. 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

LYNN WALKER

BILL LANN LEE

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Intervenors, Appellees

Richardson, et al., in Nos. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

Appellee,

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-lntervenors, Appellees,

VS.

RAY BLANTON, Governor of the State of Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS, APPELLEES

RICHARDSON, et al., IN NOS. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE E. FRANKLIN

RICHARD H. DINKINS

Suite 1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tenn. 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

LYNN WALKER

BILL LANN LEE

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-intervenors, Appellees

Richardson, et al., in Nos. 77-1621. 1623 & 1625

INDEX

Preliminary Statement ................................ 1

Counterstatement of Question Presented .............. 2

Counterstatement of the Case ......................... 2

Argument .............................................. 3

I. The Dual System of Public Education in

Tennessee Has Not Been Dismantled............ 5

A. Evidence of Discrimination .............. 6

B. The Continuing Constitutional Violation . 10

C. UT1 s Liability ........................... 17

II. The State Has An Affirmative Duty to

Dismantle the Dual System.................... 21

A. The Constitutional Standard ............. 21

B. THEC and UT Misconstrue the Standard .... 24

III. The Lower Court Properly Exercised Its

Equitable Discretion in Ordering the

Merger of TSU and UTN......................... 31

A. The Equitable Standard .................. 31

B. Merger Is an Appropriate Remedy in

This Case ................................ 33

C. THEC and UT's Objections to Merger Do

Not Demonstrate an Abuse of Equitable

Discretion ............................... 36

Conclusion ............................................ 44

Page

i

TABLE OF CASES

Adams v. Califano, 430 F. Supp. 118 (D. D.C. 1977).... 23,38,40

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir.

1973) 16,23,37

Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public

School and College Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784

(M.D. Ala. 1968) 23,24,25

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1970) .................................. 22,40

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., ___

U.S. ___, 50 L.Ed. 2d 450 (1976) ................. - 10

Bishop v. Starkville Academy, N.D. Miss. No. E.C.

74-97-K, decided December 28, 1977 12

Bradley v. Milliken, 540 F.2d 229 (6th Cir. 1976)

aff'd U.S. , 53 L.Ed. 2d 745 (1977) ..... 6,10,15,16--- 23,30,37,41

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483(1954) 11,21,29,30

Cisners v. Corpus Christi Independent School

District, 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) ............ 41

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .................. 14

East Texas Motor Freight v. Rodriguez, ___ U.S. ___,

52 L.Ed. 2d 453 (1977) 42

Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F.Supp. 428 (D.Del.)(3-judge

court) sum.aff'd. 423 U.S. 963 (1975) 416 F.Supp.

328 (D. Del. 1976)(3-judge court) aff'd. 555 F.2d

373 (3rd Cir.) cert.denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3220 (1977)..18,20,41

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) .......... 42

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ........................................... . 23,27, 38

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 310 F.2d 536

(E.D. La. 1970) .................................. 41

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) ............ 18,20,23

Hunnicut v. Burge, 356 F. Supp. 1227 (M.D. Ga. 1973)..

Page

23

Page

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) 10,11,12

13,23

Kirsey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

554 F. 2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977) .................... 42

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ............... 13

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 453 F.2d

(5th Cir. 1971) .................................. 23,37,38

Local 189, United Paper Makers and Workers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) ..... 41

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .... 23

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ........................................... 29

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ......... 6,7,9,1017,18,21,22

23,26,28

Milliken v. Bradley II, ___ U.S.___ , 53 L.Ed. 2d

745 (1977) aff'g, 540 F.2d 229 (6th Cir. 1976) ... 4,31,35,43

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) .......................................... 27

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F.2d 1042

(6th Cir. 1977), cert.denied 46 U.S.L.W. 3886

(Dec. 12, 1977) 11,13

Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Education,

510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir. 1974), cert.denied

421 U.S. 931 (1975) 6,18,20,41

Norris v. State Council of Higher Education,

327 F. Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va. 1971) .............. 23,24,2529, 37 ,38

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232

(1970) 16

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) ......... 12

Oliver v. Michigan State Board of Education, 508

F .2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974) 13

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976) 16

iii

Pa^e

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970) ......

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 15 (1971) .............................

Sweat v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) .............

United States v. International Longshoremen's Assoc.,

319 F. Supp. 737 (D. Md. 1970) ..................

United States v. Scotland Neck Board of Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) ..............................

40

15,23,25

32,42

29

41

12,13

30,41

United Jewish Organization of Williamsburgh v. Carey,

___ U.S. ___, ___ L.Ed. 2d ___ (1977) ........... 41

United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin ISD),

5th Cir. No. 73-3301, decided(November 21, 1977) .. 6,11,13

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) . 6,7,9,10

11,12,13,21

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) .........

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) .........................................

42

12,13

28,41

Other Authorities:

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ..........................

42 Federal Register 40780 (August 11, 1977)

iv

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

Appellee,

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-lntervenors,

Appellees,

VS.

RAY BLANTON, Governor of the State of

Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS, APPELLEES

RICHARDSON, et al., IN NOS. 77-1621, 1623 & 1625

Preliminary Statement

It is the position of plaintiffs-intervenors Richardson,

et_ al. in these consolidated appeals that the lower court

properly ordered the merger of TSU and UTN in order to desegre

gate public higher education in Nashville, but the district

court erred in its further rulings on the implementation of

the Nashville merger and the adequacy of statewide desegregation

efforts outside Nashville. We, therefore, respond in this

brief as appellees to the briefs of two of the defendants, UT

and THEC, on their appeals on the validity of the TSU-UTN

merger (77-1621 and 1625, and 77-1623 respectively). in a

separate brief, we reply to the responses of the other

parties on our appeal from the implementation of merger and

{/the adequacy of the statewide remedy (77-1622 and 1624).

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the district court abused its discretion in

ordering as a form of equitable relief that TSU and UTN be

merged in order to dismantle Tennessee's dual public higher

education system?

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiffs-intervenors Richardson, et_ al. incorporate

by reference the Statement Of The Case and Statement Of Facts

in Brief For Plaintiffs-lntervenors, Appellants Richardson,

et al. in 77-1622 and 1624 (hereinafter "Richardson brief")

1/ Plaintiffs-intervenors Richardson, et al. also have

opposed the intervention of UTN faculty, 77-1620, in a

separate brief.

2

pp. 2-48. 2/

ARGUMENT

In response to the contentions made by defendants

1/UT and THEC against merger, we argue three key points

in support of the lower court's merger ruling: (a) the

State continues to operate a dual public higher education

system, (b) the duty of the State is to affirmatively desegre

gate the dual system, and (c) merger of TSU and UTN is an

appropriate remedy. Initially, however, we note that the

thrust of UT and THEC's arguments ignores altogether the

lower court's comprehensive findings of fact on the dual state

wide system and the underlying voluminous trial record,

which are presented in detail in the Richardson brief,

4/pp. 2-48, and the government's brief, pp. 2-34: The

statewide dual system remains in place. UTN was

established in Nashville in 1947 as the white public higher

education alternative to all-black TSU, the preexisting

State-supported higher education institution in Nashville.

Since State-imposed segregation required by law formally

2/ Compare the Statement Of The Case in Brief For The

United States in 77-1621, 1623 & 1625 (hereinafter "govern

ment's brief"), pp. 2-34.

3/ Defendants Ray Blanton, Governor of Tennessee, represented

by the State Attorney General, and the State Board of Regents

have not appealed the merger order.

4/ Compare Brief For Plaintiffs Rita Sanders Geier, et_ al.

in 77-1622 and 1624, pp. 1-5.

3

ended in I960, UTN has greatly expanded from a non-degree

granting night school to a 4-year, degree-granting university

with classes after mid-afternoon. In contrast, TSU has not

6/been able to expand significantly. UTN and TSU provide dupli

cative academic programs, and compete for white students. With

UT's prestige and TSU's black history, UTN has been able to

siphon off white Nashville area students who would have natu

rally desegregated TSU. As a result, 9 years after the lower

court's first order that the dual system be dismantled, TSU's

student body remains overwhelmingly black and UTN's majority

white, and TSU is identifiably black and UTN identifiably white.

As the court further found, defendants, including UT and THEC,

have been recalcitrant, and actively opposed and frustrated

meaningful efforts to desegregate. After years of such recal

citrance, the lower court finally ordered the merger of TSU and

UTN, as the best alternative, in order to dismantle the dual

7/

system in Nashville, and Tennessee generally.

5/ 288 F. Supp. at 940. Available records show that the first black Student was not admitted to UTN until 1965, Response of Defendants to

Richardson Intervenors Supplemental Interrogatories, June 13, 1974.

6/ Although the court did not update its finding that "the

failure to make [TSU] a viable desegregated institution in the

near future is going to lead to its continued deterioration as

an institution of higher learning," 288 F. Supp. at 943, the

1976 record shows that tangible unequal educational opportunity

continues, see Richardson brief, pp. 15-16; cf. Milliken v .

Bradley, ___ U.S. ___, 53 L.Ed.2d 745, aff'g, 540 F.2d 229 (6th

Cir. 1976).

7/ See Richardson brief, pp. 13-32; government's brief, pp. 2-34.

4

Ignoring these findings, UT and THEC develop at

length several legal contentions which attempt (a) to gut

the lower court's careful findings of fact merely by invoking

recent Supreme Court decisions concerning proof of discrimi

nation, (b) to argue that the State has only the duty to

"remove compulsive segregation," and (c) to argue that

merger of TSU and UTN is per se an abuse of discretion. We

refute these contentions in turn below, but press the threshold

point that UT and THEC do not even attempt to met their

burden to show that these plain findings of fact are clearly

erroneous. For example, neither THEC and UT mention that

all expert opinions, including that of THEC officials and

defendants' Long Range Plan consultants, was that merger

was "the best long range solution for desegregating the

Nashville area," 427 F. Supp. at 657-659, Richardson brief,

pp. 28-31, government's brief, pp. 28-32. The failure to

meet the clearly erroneous standard is a defect which, as we

further detail below, is fatal to their appeals.

8/

I.

THE DUAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC EDUCATION IN

TENNESSEE HAS NOT BEEN DISMANTLED.

Throughout 9 years of litigation, the parties did not

contest the basic existence of de jure systemic segregation

8/ The UT appellants brief in 77-1621 & 1625 is hereinafter

cited as "UT appellants brief," and the THEC appellant brief in

77-1623 is hereinafter cited as "THEC appellant brief."

5

and maintenance of a dual system in the State of Tennessee;

the issue -was the steps required to dismantle the dual system.

UT and THEC now throw up legal defenses based on Washington

v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) and Milliken v. Bradley/ 418

U.S. 717 (1974), which if accepted, would exempt the State

from the long-recognized but unrealized "affirmative duty

imposed upon the State by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States to dismantle the dual system of

higher education which presently existed in Tennessee,"

288 F. Supp. at 942. As in other recent school desegregation

cases in which defendants have attempted to raise Washington

v. Davis (see, e.g., Bradley v. Milliken, 540 F.2d 229 (6th

Cir. 1976), aff*d. __U.S.__, 53 L.Ed. 2d 745 (1977); United

States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin ISD), 5th Cir.

No. 73-3301, decided November 21, 1977) and Milliken v .

Bradley I (see, e.g., Newburg Area council Inc, v. Board

of Education, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

421 U.S. 931 (1975)) these defenses come too late, have no

basis in the record and are clearly without merit. They

therefore, must be rejected.

A. Evidence of Discrimination

THEC and UT contend that the only valid evidence of

segregation in Tennessee public higher education is statisti

cal disparity in the enrollment of traditionally black TSU

6

and the traditional white institutions, including UTN.

It is upon this factual premise that defendants base their

Washington v. Davis and Milliken v. Bradley I contentions

that the evidence is legally insufficient for liability.

The factual premise, however, is a straw man.

In 1968, 1972 and 1976 the lower court concluded that the

de jure statewide dual system required by law until 1960,

particularly all-black TSU, has not been dismantled, 288

F. Supp. at 940; 337 F. Supp. at 576; 427 F. Supp. at 652.

As the lower court put it in 1972, "the phenomenon of a

black Tennessee State, so long as it exists, negates both

the contention that defendants have dismantled the dual

system of public higher education in Tennessee, as ordered

by this Court, and the contention that they are, in any

realistic sense, on their way toward doing so," 337 F. Supp.

at 576. TSU's "Negro enrollment in excess of 99 per cent"

in 1968 was still as high as 92.5% black for on campus students

10/

in fall 1976; UTN, in constrast, remains predominantly

V

9/ THEC appellant brief, p. 14 et seq.; UT appellants brief,

p. '21 et_ seq. Although the THEC and UT briefs intersperse

discussions of continuing segregation and the legal duty to

desegregate, plaintiffs-intervenors separately discuss the two

issues for the sake of analytical clarity.

IQ/ The lower court found that; Defendants' "Febrary 1976

Progress Report reveals that the enrollment at TSU in fall,

1975, was about 85% percent black and about 12.2 percent white.

However, the proportion of whites on the main campus had not

7

white. Moreover, the lower court's opinion is replete with

underlying findings of fact that defendants have taken actions

since 1960 to maintain the dual system and obstruct desegre

gation, notably maintaining a duplicative academic program

U /

at UTN and permitting UTN to siphon off white students who

12/

could be expected to attend TSU, i.e. "the existence and

10/ (Continued)changed since the previous year and remained at about 7 percent,

leading to the conclusion that a great number of the white

students enrolled at TSU were actually taking courses in off-

campus centers since over 80 percent of the students in these

centers were white," 427 F. Supp. at 652, 660. In fact, 74%

of TSU's white students were taking courses in the off-campus

centers, see DX 11 at pp. 38, 42, 48. In fall 1976, the white

presence on the TSU campus remained 7% (T. 1382, A. ), and

95% of TSU's off-campus students were white (DX 36, A. ),

see 427 F. Supp. at 656. It is thus misleading for defendants

to insist that TSU is over 12% white, UT appellants brief, p. 7,

THEC appellant brief, p. 9.

11/ The lower court expressly found that UTN's program

duplicated TSU's, 427 F. Supp. 652. "The best evidence of

the competitive nature of the Nashville situation is found in

the similar programs offered by both institutions," which

"have remained predominantly one-race at each institution,"

id. See also Richardson brief, p. 18; government's brief,

pp. 21-24.

That TSU has 73 degree-granting programs while UTN has

only 9, UT appellants brief, p. 9, is a distinction without a

difference, which results from TSU's practice of specifying

major areas and UTN's practice of offering one degree for large

numbers of areas, compare, DX 41 (TSU catalogue), with.

PIX 11 (UTN catalogue). The lower court rejected this con

tention, without comment.

12/ The lower court specifically found that "even if the

average student profile at UTN shows that those students are

older [than TSU students] and are employed, these are the

kind of students that THEC and Dr. Elias Blake, witness for

the United States, say that TSU must attract if it is to

prosper," 427 F. Supp. at 653. The record fully supports the

8

expansion of predominantly white UTN alongside the

traditionally black TSU have fostered competition for white stu

dents and thus have impeded the dismantling of the dual system,"

427 F. Supp. at 652-657, Richardson brief, pp. 13-28, govern

ment's brief, pp. 5-28.

Thus, defendants UT and THEC's present claim that this

is a case of de_ facto segregation CLn order to invoke Washington

v. Davis and Milliken I)has no basis in the record, and,

indeed, can only be maintained by ignoring express findings of

fact and the underlying record. The district court found, in

the higher education context, classic indicia of de_ jure

school segregation - state-imposed statutory segregation

consistently maintained by the actions of State officials.

The Nashville situation, indeed, is more aggravated in light

of defendants1 recalcitrance to effect court-ordered desegre

gation over the course of 9 years. The time is long past to

inject a challenge to the underlying finding of statewide

12/ (Continued)

court, see Richardson brief, pp. 16-17; government's brief,

pp. 23-25. Moreover, UTN students are increasingly younger and

full-time (PXX 15, A. ) and UTN offers a substantial number

of courses, principally undergraduate courses, that begin in

mid-afternoon (GX 8, A. ). UT's claim that TSU "with the

exception of one (1) nursing course, operates exclusively as a

late-evening and nighttime school primarily for working adults,"

UT appellants brief, p. 9, is therefore insufficient to meet

the clearly erroneous test. Moreover, the UTN daytime nursing

course in question (75.1% white) competes directly with a TSU

daytime program (70.9% black), 427 F. Supp. at 655, n. 27; see

Richardson brief, p. 25.

9

seeviolation, which subsequent evidence only fortifies,

Bradley v. Milliken, 540 F.2d 229, 239 (6th Cir. 1976), aff*d,

__U.S. , 53 L.Ed. 2d 745 (1977) (' [w] e find [Washington v.

Davisl to be inapplicable here because it is the law of the

case that unlawful de_ jure segregation . . . exists ") .

B. The Continuing Constitutional Violation

UT and THEC contend that Washington v. Davis, supra,

somehow voids the legal significance of the State's manifest

and consistent perpetuation of Tennessee's statutory system

w

of de_ iure segregated higher education. It was in Keyes

v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 208 that the Supreme

Court ruled that "the differentiating factor between de_ jure

segregation and so-called de_ facto segregation . . . is

purpose or intent to segregate" (original emphasis), of which

Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 240-244 is an elabora

tion beyond the school segregation area, see also Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.. __U.S.__, 50 L.Ed. 2d

450, 464-466 (1976). Keyes, involving the Denver, Colorado

public schools, was "not a case, however, where a statutory

13/

13/ The basic de_ jure statewide systemic segregation finding has

remained unchanged. The court did revise its 1968 ruling

that UTN's expansion would not necessarily perpetuate the dual

system based on additional evidence, 427 F. Supp. at 652. See

infra at pp. 18-20.

14/ See, e.g., UT appellants brief, pp. 20, 29-30, THEC

appellant brief, p. 14. We discuss Milliken v. Bradley, infra,

at part A.3.

10

dual system has ever existed," supra, 413 U.S. at 201;

compare NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F.2d

1042, 1045 (6th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3886

(December 12, 1977). Such cases, like the instant action,

are governed as to per se unconstitutionality by Brown v .

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). This was precisely

the question in United States v. Texas Education Agency

(Austin ISP), 5th cir. No. 73-3301, decided November 21,

1977, on remand from, 429 U.S. 990 (1977), in which the

Fifth Circuit ruled that "because Washington v. Davis is

concerned with the evidentiary showing necessary to establish

an equal protection violation in those situations where there

has been no law specifically requiring segregation, that

decision is inapplicable 'where a statutory dual system has ever

existed,' Keyes v. School District No. 1, . . . " slip

opinion at 4 (referring to Texas segregation law for black

students). This Court had earlier recognized in NAACP v .

Lansing Board of Education, supra, 559 F.2d at 1045, the

same principle that " [w]here a dual educational system was

authorized by state law at the time of Brown I, . . . [t]he

State automatically assumes an affirmative duty 'to

effectuate a transition to a racially non-discriminatory

school system,' Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

11

294 . . . (1955) (Brown II) , by eliminating 'all vestiges

of state-imposed segregation,' Swann v. Board of Education,

402 U.S. [1,] 15 . . . [(1971)];" compare Keyes v. School

District No. 1, supra, 413 U.S. at 200. There is thus no

merit for THEC's and UT1s attack on the lower court's

conclusion that "the establishment by State statute was a

blatant constitutional violation," 427 F. Supp. 660, whose

vestiges have not been remedied.

In addition, district court's findings on the

expansion of UTN to the detriment of TSU, the duplication

of courses, the competition for white students and other

State actions since 1960 demonstrate continuing de_ jure

segregation on several other grounds: First, that State

officials unlawfully impeded desegregation is unlawful

regardless of intent to discriminate, Wright v. Council of

City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972); United States v. Scot

land Neck Board of Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972); Norwood

v. Harrison, 413 U.S. .455, 467 (1973); Bishop v. Starkville

Academy, N.D. Miss. No. EC 74-97-K, decided December 28,

1977 (3-judge court) (distinguishing Norwood v. Harrison

from Washington v. Davis) .

"The mandate of Brown II was to desegregate

schools, and we have said that ' [t]he measure

of any desegregation plan is its effective

ness. ' Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33, 37 . . . Thus, we have

focused upon the effect— not the purpose or

12

motivation— of a school board's action in

determining whether it is a permissible method

of dismantling a dual system. The existence

of a permissible purpose cannot sustain an

action that has an impermissible effect."

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, supra, 407 U.S. at 462;

Oliver v. Michigan State Board of Education, 508 F.2d 178,

183 (6th Cir. 1974). Second, the focus of Washington v .

Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 283-284, on intent, in any event,

does not apply to either actions under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, or this action

which is brought, inter alia, to enforce Title VI of the

15/Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, see Lau v. Nichols, 414

U.S. 563, 566-569 (1974). Third, "school authorities have

carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting

a substantial portion of students, schools, teachers, and

facilities within the school system" which would establish

requisite intent even without prior legal segregation,

Keyes v. School District No. 1. supra, 413 U.S. at 201;

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, supra, 559 F.2d at

1042, 1049-1057; united States v. Texas Education Agency

(Austin ISP). supra (portion of opinion on Chicano students).

We now proceed to address several subsidiary

liability contentions.

1. THEC claims that the lower court "did not find,

however, that any 'vestiges' of prior de jure segregation

15/ See, e.g., complaints of plaintiffs-intervenors

Richardson and the united States (R. 33, 34, 86, A. __, __, _

see,

13

had been carried forward by present discriminatory State

action" and that the "'vestiges' of legalized segregation

referred to consist of the persistence of private racial

attitudes expressed in student choices," p. 15. The district

court obviously did find vestiges of prior legal segregation,

and just as obviously, the vestiges of legal segregation

were the product of State action and institutional in

character. Moreover, the State cannot excuse responsibility

for the substantial segregation-enforcing acts of its

officials merely by invoking "private racial attitudes;"

it is defendants who created and maintain the dual system.

Government simply may not support unlawful racial segregation,

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958),

2. Defendants make the related argument that the

existence of a single black school, TSU, in the Tennessee

17/education system is not probative of a persisting dual system.

" [Wjhere it is possible to identify a 'white school' or a

'Negro school' simply by reference to the racial composition

of teachers and staff . . . , a prima facie case of violation

of substantive constitutional rights under the Equal Pro-

16/ We address, infra, at pp. 2 8-31 the claim that higher

education systems differ significantly from elementary and

second schools because of the "voluntary" nature of school

attendance.

17/ THEC appellant brief, p. 40; UT appellants brief, pp.

19-21.

14

tection Clause is shown," Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

18/

hoard of 'Education, supra. 402 U.S. at 18. TSU, of

course, is not just any one-race school: it was historically

" [t]he lone institution for so-called higher learning operated

by the State of Tennessee for Negroes," 288 F. Supp. at 940,

nor is the evidence of perpetuation based on statistic alone

but State action to maintain TSU's segregated status. The

record is conclusive that the maintenance of TSU as a black

institution was discriminatory.

3. UT argues that " [t]here is a patent inconsistency

in the District Court's finding and holding that the previously

existing dual system has been effectively dismantled in the

statewide system of predominantly white institutions . . . ,

while, at the same time finding and holding that the dual

system had not been dismantled as it relates to the Nashville

19/

area involving TSU and UTN," p. 16. The simple answer is

that the district court has never found that Tennessee has

18/ "Where the school authority's proposed plan for conversion

from a dual to a unitary system contemplates the continued

existence of some schools that are all or predominately of one

race, they have the burden of showing that such school assign

ments are genuinely nondiscriminatory. The court should

scrutinize such schools, and the burden upon the- school

authorities will be to satisfy the court that their racial

composition is not the result of present or past discriminatory

action on their part." Id. at 26; Bradley v. Milliken, supra,

540 F.2d at 237-238.

19/ THEC does not argue that the dual statewide system has been

converted to a unitary system, only that it is "satisfactorily

desegregating," THEC brief at 40.

15

dismantled its statewide system or achieved conversion to a

statewide unitary system, Pasadena city Board of Education

v. Spangler. 427 U.S. 424 (1976). As Chief Judge Phillips put

it in Bradley v. Milliken, supra, 540 F.2d at 239, " [t]his is

not a Spangler situation; 11 see also, Northcross v. Board of

207Education of Memphis, 397 U.S. 232 (1970). While

the statewide and Nashville issues were the "two prongs of the

problem," the district court specifically found that " [i]n

Tennessee, the sole black institution, TSU, is the heart of

the dual system" and that the "'phenomenon of a black Tennessee

State, so long as it exists, negates . . . the contention that

defendants have dismantled the dual system of public higher

21/education in Tennessee,r" 427 F. Supp. at 650.

20/ At most the lower court only found that "the white insti

tutions are making steady progress toward desegregation," 427

F. Supp. 644 (emphasis added), and, as plaintiffs-intervenors

Richardson et al. assert in their appeal, the State's desegre

gation efforts statewide are inadequate, Richardson brief,

pp. 34-48, and that the lower court erred in failing to order

greater statewide desegregation, Richardson brief, pp. 53-62.

21/ Nor is the lower court's decision inconsistent with the

statewide desegregation approach of Adams v. Richardson, 480

F .2d 1159, (D.C. Cir. 1973), UT appellants brief, pp. 35-36;

THEC appellant brief, p. 46 , for the reasons set forth in

427 F. Supp. at 650 n. 14. As we discuss infra, at p. 40, the Dept.

of Health, Education and Welfare has developed higher education

criteria, pursuant to Adams, which expressly sanction the

merger ordered as a remedial device for black public higher

education institutions.

16

C. UT*s Liability

UT, in particular, contends that, "the court's judgment

and order is the equivalent of an inrerdistrict remedy -without

2 2/an interdistrict violation or interdistrict effect" Re

lying on Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974), ut

characterizes itself as "an innosent party" and claims that

"the Court has never found that racially discriminatory acts

of the University of Tennessee defendants have been a sub

stantial cause of segregation, past or present, at TSU,"

p. 23. The lower court of course stated the specific finding

that:

"The Court now finds that the existence and

expansion of predominantly white UTN alongside

the traditionally black TSU have fostered com

petition for white students and thus have

impeded the- dismantling of the dual system. "

22/427 F. Supp. at 652. The district court then detailed how

" [w] ith TSU's blac.k history and UT's prestige, this competition

inevitably fosters dualism," 427 F.Supp. at 653. We need not * 2

22/ UT appellants brief, pp. 21-30; THEC appellant brief, pp. 53-58.

2 3/ The unsupported statement that, " [t]he establishment of

UTN in 1971 post dated the past mistakes and inequities found to

exist and was wholly unconnected therewith," ut appellants brief,

p. 32, if, clearly wrong. Since 1967, TSU has been the black

public h igher educational institution in Nashville while UTN

has been the white institution in Nashville, and the lower court

so fouud, 427 F. Supp. at 652.

17

reiterate the extensive underlying facts supporting the

lower court's finding as to UT, Richardson brief, pp. 16-21,

goverru Lent's brief, pp. 18-28, which under the relevant

caselav set forth at, supra, part A.2 establish beyond

peradventure UT1s liability. Nor can UT even argue that

it and the State Board of Regents have geographically

distinct jurisdictions.

Th ; reliance of UT and THEC on Milliken I is misplaced

for the same reason that this and other courts have upheld

interdistrict remedies in which several governmental entities

were involved in the underlying constitutional violation,

Newburg area council, Inc, v. Board of Education of Jefferson

County, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421

U.S. 931 (1975); Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428

(D. Del.’ (3-judge court), sum, aff'd. 423 U.S. 963 (1975);

416 F. Sipp. 328 (D. Del. 1976) (3-judge court), aff'd,

555 F.2d 373 (3rd cir.), cert, denied, 46 U.S.L.W. 3220

(1977); Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976).

UT also makes several subsidiary claims. First, UT,

UT appellmts brief, pp. 27-28, cites the court's initial

1968 finding on the then-existing record that "I do not find

that the proposed construction and operation of the

University of Tennessee Nashville Center will necessarily

perpetuate a dual system of higher education," 288 F. Supp.

18

at 941 (original emphasis) because there was "nothing in the

record that the University of Tennessee has any intention

to make the Nashville Center a degree-granting day institu

tion, " and the center’s "overwhelming emphasis" was on part-

time evening programs, id. By 1977, there was sufficient evi

dence so that defendants' representations about the limited

24/

role of UTN were found out. The district court, therefore,

revised its finding and ruled that " [t]he Court now finds

that the existence and expansion of predominantly white UTN"

fostered competition for students and impeded dismantling

the dual system, 427 F. Supp. at 652 (emphasis added).

24/ An example is the following testimony of UT President

Edward j. Boling that UT had decided as early as 1965 to make

UTN a degree-granting institution.

Q. "Now, getting back to UT/N, I notice that in

Exhibit 70 — we were on Exhibit 75 — and you indicated that

you asked the — the board decided in 1968 to expand and to

undertake degree offerings in business administration and

general engineering because they thought there was a need

here in Nashville; is that right?

A. "That is really what the people came about mostly

in 1965. At that time we still hadn't done it and we felt

there was a need.

Q. "You were all taking time to try to develop that?

A. "We had been developing it and people had been working

up the courses and coming to Knoxville for a degree. It still

had not been built in the way that people down here thought it~

should be built in terms of having the curriculum set the way

they wanted it.

Q. "And then, of course, you knew the lawsuit was filed

at that time, didn't you?

A. "It was filed somewhere in that period.

Q. "Didn't you know it was filed in '67?

A. "I don't know what the date was.

(cont *d)

19

Second, UT makes the novel claim that merely because

UTN and TSU have different governing boards, it is shielded

from liability, pp. 24-26. This is surely an argument that

falls of its own weight in light of the record of UT's lia

bility, Newburg Area Council, Inc, v. Board of Education of

Jefferson County, supra; Evans v. Buchanan, supra; Hills v .

Gautreaux, supra. Nor can UT argue against the lower court's

finding that the dual system of public higher education in

Tennessee is a system, see, e .g., 427 F. Supp. at 650, as

clearly erroneous. Obviously the Tennessee public higher

education system operates as a common system funded by the

State legislature, with a master plan (PIX 3, A. ) and

with THEC coordinating the planning, financing and programs

24/ (Continued)

Q. "Well, of course, this exhibit is dated, this board

meeting was held in October 1968. Didn't you know that the

Court had entered an order in this case on August 21, 1968, in

which it had denied — which it predicated its order allowing

UT/N to — the Nashville center to build a building here on

the theory that there is nothing in the record to indicate that

the University of Tennessee has any intention to make the

Nashville center a degree-granting day institution?

A. "Our program was intended all along to let people work

toward degrees. That was the basis for starting it in 1965.

THE COURT: "Well, my opinion speaks for itself. At that

time there was no indication in the record they intended to

have a degree-granting day institution. That is what I said."

(T.II 293-294) (emphasis added). Thus, UT, at the very least,

is disingenuous when it declares that the 1968 order is the

lower court's only finding as to UT and that "[t]he District

Court has never, in any subsequent decision, finding, order of

judgment, found or held to the contrary," UT appellants' brief,

p . 28.

20

2 5/of education institution.—

In short, Washington v. Davis and Milliken v.

Bradley I simply do not undermine what was never seriously

disputed before in this long litigation, i.e., the lower

court's finding that the failure to dismantle public

higher education system is a constitutional violation,

nor permit defendants UT and THEC to escape their legal

obligations. It is the existence of this continuing

Fourteenth Amendment violation that gives rise to the State's

affirmative duty to desegregate.

II.

THE STATE HAS AN AFFIRMATIVE DUTY TO

DISMANTLE THE DUAL SYSTEM.___________

A. The Constitutional Standard

Since Brown II, the Supreme Court has clearly stated

that once there is a violation, "the burden of State 2

2 5/ THEC concedes that UT and UTN are part of the dual

system, and argues only that segregation at UTN does not

contribute to segregation at TSU, THEC brief, pp. 57-58.

This of course flies in the face of the clear record that

UTN's existence and expansion were inextricably a part of the

dual system in Nashville and Tennessee generally.

21

officials is . . . 'to eliminate from the public schools

all vestiges of state-imposed segregation '" Milliken v.

Bradley II, supra, 53 L.Ed. 2d at 762, and to do so at the

"immediately" and "at the earliest practicable date,"

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19, 20 (1970).

"The objective today remains

to eliminate from the public schools

all vestiges of state-imposed segre

gation. Segregation was the evil

struck down by Brown I as contrary

to the equal protection guarantees

of the Constitution. That was the

violation sought to be corrected

by the remedial measures of Brown II.

That was the basis for the holding

in Green that school authorities are

"clearly charged with the affirmative

duty to take whatever steps might be

necessary to convert to a unitary

system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch."

391 US, at 437-438 .

"If school authorities fail in

their affirmative obligations under

these holdings, judicial authority

may be invoked. Once a right and

a violation have been shown, the

scope of a district court's equitable

powers to remedy past wrongs is broad,

for breadth and flexibility are in--

herent in equitable remedies."

22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra,

402 U.S. at 15; compare Milliken v. Bradley II, supra.

There is simply no doubt that an affirmative duty exists

2 6/

to effectively and promptly desegregate a dual school system.

And there is no doubt that in performing its duty, a court

must meet "the 'root and branch requirements of Green v.

County School Board, 391, U.S. 430, 437-38 . . . (1968),

and the call-out desegregation requirements of Keyes v.

School District, 413 U.S. 189, 214 . . . (1973)," Bradley

v. Milliken, supra, 540 F.2d at 238.

Thus, every court which has been faced with a constitu

tional violation in higher education has acknowledged the

affirmative duty imposed by the Constitution to dismantle

the dual system as did the lower court, see, e,g., Alabama

State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School and

College Authority, 289 F.Supp. 784, 789 (M.D. Ala. 1968);

Norris v. State Council of Higher Education, 327 F.Supp.

1368, 1373 (E.D. Va. 1971); Hunnicutt v. Burge, 356 F. Supp.

1227, 1230 (M.D. Ga. 1973); Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 453 F.2d 524, 527 (5th Cir. 1971); see also

Adams v„ Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Adams

v. Califano, 430 F. Supp* 118 (D.D.C. 1977) (Adams cases

construe Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 42 U.S.C.

26/ The rule in civil rights controversies generally is that "the

court has not merely the power but the duty to render a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in the

future," Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965),

Albemarle Paper Co, v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975); Hills

v. Gautreaux, supra, 425 U.S. at 297; see also Milliken v.

23

§ 2000d to require affirmative duty to desegregation).

B . THEC And UT Misconstrue The Standard

Defendant THEC and UT make several contentions which

take issue with the lower court's acceptance of this con

stitutional standard.

1. UT and THEC reiterate the contention that a "good

faith" "open door policy" is the sum total of defendants'

duty to desegregate, i.e ., "a State satisfies its constitu

tional duty to desegregate higher education by permitting

the free choice system of enrollment to operate free of

State-imposed racial discrimination," THEC brief, p. 16,

and that caselaw "limit[s] the constitutional goal in higher

education to the removal of compulsory segregation," UT

brief, p. 18, which the district court clearly rejected in

1968 (288 F.Supp. at 942) and in 1972, (337 F. Supp. at 577-

581), see 427 F. Supp. at 646.

Little that THEC and UT raise now was not dealt with

in the lower court's 1972 opinion at considerable length:

in particular, Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama

Public School and College Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784 (M..D.

Ala. 1968), sum, aff'd , 393 U.S. 400 (1969), upon which THEC and

UT rely principally, and Norris v. State Council of Higher

26/ continued

Bradley II, supra.

24

Education, 327 F. Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va. 1971) sum, aff 'd

sub. nom. Board of Visitors of the College of William & Mary

in Virginia. 404 U.S. 907 (1971)-, which defendants go to some

2 7/

pains to distinguish, were correctly and exhaustively analyzed.

27/ 337 F.Supp. at 577-580. In ASTA, the court refused

to enjoin the construction of a white institution near

traditionally black Alabama State College; in Norris. the

the court enjoined the construction of a white junior college

near predominantly black Virginia State College. The court’s

analysis was: First, ASTA "does not stand for the proposi

tion that a state is under no affirmative duty to dismantle

a dual system of higher education in those cases where such

a system is a vestige of d e jure segregation," 337 F. Supp.

at 578; compare, ASTA 289 F. Supp. at 789, with. Norris,

327 F. Supp. at 1373. Second, "the ASTA court was consis

tent with the Norris line of reasoning . . . the Asta court

merely refused to enjoin certain construction, on the basis

of the facts before it." 337 F. Supp. at 579. Third, certain

kinds of relief used in elementary and secondary school cases

may not work in the college context.

"[Wjhat works in one system will

not work in another. Yet this is

so as a practical matter, and not as

a result of either of there being

less of a duty owed by a state to

dismantle a dual system of higher

education or of a lack of power

. . . on the part of a federal

court to remedy such a situation.

The limiting factor, from the court's

point of view, is 'what will work?'"

337 F. Supp. at 580. Fourth, the ASTA court acted as a court

of equity and balanced competing interests; the approach

taken by both ASTA and Norris is consistent with Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra,

25

The lower court's ruling was that:

"From a consideration of both

ASTA and Norris, read in the light

of the whole line of desegregation

cases culminating in Swann, this

court is of the opinion that the

present state of the law is as

follows: (1) There is an affirma

tive duty on a state to dismantle its

dual system of education, when such

system is a vestige of de jure segre

gation; (2) "The means of eliminating

discrimination in public schools neces

sarily differ from its elimination in

colleges but [(3)] the state's duty

is as exacting" Norris, 327 F.Supp.

at 1373; (4) a federal district court,

in order to ensure that such duty is

performed,is to proceed as a traditional

court of equity; (5) accordingly, in

framing relief, the court must balance

the interests involved and take into

account the administrative feasibility

of the proposed relief, and, in fash

ioning the remedy, the scope of the

relief must be fitted to the scope of

the violation; and (6) in cases involving

higher education, the interests of the

state in setting its own educational

policy are to be given especially great

weight."

2 8/

337 F. Supp. 580, On the basis of these factors, the court

concluded that "when the basic (and preferred) approach of

an open door policy fails to be effective, the interests

of the State in completely setting its own educational

policy must give way to the interests of the public and

the dictates of the Constitution," id. Although the district

court ordered defendants to consider, 'inter alia, "merger

or consolidation of Tennessee State and U.T. Nashville into

a single institutiont" 337 F.Supp. at 581-582, the court

of course did not then exercise its discretion to order

23/ Compare Milliken v. Bradley II, supra, 53 L.Ed. 2d

755-756.

26

merger, but waited another 4 years. It then became clear,

as the court found, that "the defendants 1 approach to eliminat

ing the effects of State-imposed segregation in the Nashville

area institution has not worked and that it offers no real

hope for further progress in that direction," 427 F. Supp.

at 657. Only then was merger ordered.

2. THEC, but not UT, makes the argument that

the "plain language" of Green v. County School Board, supra,

29/ 50/

391 U.S. at 438-439, somehow does not mean what it says,

that "freedom of choice" plans, like all other desegregation

plans must be measured against the duty to dismantle the

dual system, i .e [t]he burden on a school board today is to

come forward with a plan that promises realistically to work

now. "

"In Green v. County School Board

. . ., the issue was whether the school

board's adoption of a "freedom of choice"

plan constituted adequate compliance with

the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education,

349 US 294 (Brown II). We did not hold

that a freedom-of-choice plan is of itself

unconstitutional. Rather, we decided that

any plan is "unacceptable" where it "fails

to provide meaningful assurance of prompt

and effective disestablishment of a dual

system. . . . " 391 US, at 438 . . . . In

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 US

450 . . ., we applied the same principle in

rejecting a "free transfer" plan adopted by

the school board as a method of desegrega

tion :

29/ See also Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968).

30/ THEC appellants brief, p. 24 et seq.

27

"We do not hold that ’free transfer’

can have no place in a desegregation

plan. But like 'freedom of choice,'

if it cannot be shown that such a

plan will further rather than delay

conversion to a unitary, nonracial,

nondiscriminatory school system, it

must be held unacceptable." Id., at

459 . . . "

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, supra, 407 U.S. at

460. Nothing does or can distinguish the application of

the affirmative duty obligation of school officials recog

nized in Milliken II, Swann and Green to higher education.

31/No a priori "practices-oriented" rule applies for gauging

the effectiveness of desegregation: "any plan is 'unaccept

able' where it 'fails to provide meaningful assurance of

prompt and effective disestablishment of a dual system,'"

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, supra, 407 U.S0 at

460, or as the lower court put it, ”[t]he limiting

factor from the court's point of view is 'what will work?'"

337 F.Supp. at 580.

3. Lastly, THEC and UT argue that "systems of higher

education are non-compulsory, and are intended to provide

students with a variety of dissimilar institutions from

32 /which to choose" and that the difference between secondary

and higher education [is] the difference between compulsion

31/ THEC appellant brief atpp. 33 et seg.

32/ THEC appellant brief, p. 18.

28

and choice." First, the distinction is a red herring. The

affirmative duty to eliminate segregation derives from the

nature of the Constitutional violation, i.e., the existence

of a dual system not from any a_ priori difference between

compulsive and free choice systems of education. As the

lower court put it, while 1,1 [t]he means of eliminating dis

crimination in public schools necessarily differ from its

elimination in colleges, . . . the state's duty is as

exacting,'" 337 F. Supp. at 578, guoting Norris

----- 347

v. State Council, supra, 327 F. Supp. at 1373. Second.

the distinction obviously proves too much. The affirmative

duty to desegregate elementary and secondary schools is

neither diminished nor increased by a legislative with

drawal of compulsory education statutes. Nor presumably

would defendants drop their arguments against affirmative

duty in public higher education, if Tennessee were to enact

compulsory collegiate education. Thirdf it is not public

elementary and secondary education which is "compulsory," but

elementary and secondary education. Thus, in school desegre

gation cases, loss of white students through exercise of "free

33/

33/ UT appellants brief, p. 41. Of course, UT subsequently

argues that "exclusive program allocation" and "geographical

limitations or restrictions upon enrollment for commuter

students11 are permissible alternatives to merger as long as

these alternatives (which of course run counter to a "free

choice system") apply only to State Board of Regents institu

tions, UT appellants brief at pp. 55-60.

34/ In Brown I, the Supreme Court rejected, without comment,

a distinction between the free choice character of graduate

education and the compulsive character of elementary and

secondary education as requiring a different result for the

students in Sweat v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) and McLaurin

29

choice," i.e.. ,lwhite flight," simply has no legal signifi

cance for purposes of desegregation. As this court put it

in Bradley v. Milliken, supra, 540 F.2d at 238, " [a]pprehen-

sion of white flight, however, cannot be used to deny basic

relief from de jure segregation" and that '"while this

development may be cause for deep concern [school authorities],

it cannot, as the Court of Appeals recognized, be accepted as a

reason for achieving anything less than complete uprooting

of a dual public school system'" quoting, United States v .

Scotland Neck Board of Education, supra, 407 U.S. at 491.

Lastly, the characterization of public higher education

as "free choice systems" is merely a disguised attempt to set

aside clear finding of facts, as the THEC appellant makes

clear: "The State has no legal responsibility for assigning

college students and no direct control over patterns of

student enrollment," p. 28. Of course, the court did con

clude that defendants created and have consistently perpetuated

and maintained a dual system of education in violation of the

14th Amendment. The underlying findings are not clearly erroneous,

and are not drained of legal significance merely by invocation

of "free choice system." This is especially true in a case in

which merger of the black school and the white school would,

as we show in the next section, directly address the very evil,

34/ continued

v. Oklahoma State Regents. 339 U.S. 637 (1950), and the school

children in Brown, see, e.g.. Briggs v. Elliott. 98 F. Supp.

529 (E.D.S.C. 1951). Again, it was " [s]eparate educational

facilities [which] are inherently unequal," not any compulsion-

choice distinction, that gave rise to the affirmative duty to

desegregate.

30

i.e. , the "existence and expansion of predominantly white

UT-N alongside the traditionally black TSU," that has "impeded

the dismantling of the dual system," 427 F. Supp. at 652.

III.

THE LOWER COURT PROPERLY EXERCISED ITS EQUITABLE

DISCRETION IN ORDERING THE MERGER OF TSU AND UTN.

A. The Equitable Standard

Whether "the District Court abused its discretion in

15/ordering merger as the remedy" must be judged under the

three-part standard recently reiterated by the Supreme Court

in affirming this Court's ruling in Milliken v. Bradley II,

U.S. , 53 L .Ed.2d 745, 755-756 (1977), aff'g, 540

26/

F.2d 229, 238 (6th Cir. 1976).

"In the first place, like other equitable

remedies, the nature of the desegregation

remedy is to be determined by the nature

and scope of the constitutional violation.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, supra, at 16 ... The remedy must

therefore be related to 'the condition

alleged to offend the Constitution. ...'

Milliken I, supra, at 738. ... Second, the

decree must indeed be remedial in nature,

that is, it must be designed as nearly as

35/ UT appellants' brief, p. 38.

36/ The court prefaced its statement of the standard with

the observation that:

"This Court has not previously addressed

directly the question whether federal courts

can order remedial education programs as part

of a school desegregation decree. However, the

general principles governing our resolution of

this issue are well settled by the prior deci

sions of this Court. In the first case concerning

31

possible 'to restore the victims of discrim

inatory conduct to the position they would

have occupied in the absence of such conduct.'

Id. at 746. ... Third, the federal courts in

devising a remedy must take into account the

interests of state and local authorities in

managing their own affairs, consistent with

the Constitution. In Brown II the Court

squarely held that ' [s]chool authorities

have the primary responsibility for elucidating,

assessing, and solving these probems. ...'

349 U.S., at 299. ... (Emphasis supplied.)

If, however, 'school authorities fail in their

affirmative obligations ... judicial authority

may be invoked.' Swann, supra, at 15. ...

Once invoked, 'the scope of a district court's

equitable powers to remedy past wrongs is broad,

for breadth and flexibility are inherent in

equitable remedies.' Ibid."

Compare Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board, supra,

402 U.S. 15-16. The district court's 1972 statement of

governing legal standards, set forth supra at p. 26, is thus

confirmed. Moreover, as we further show, merger was proper

in the record in this case and well within the "breadth and

flexibility ... inherent in equitable remedies."

36/ Continued

federal courts' remedial powers in eliminating

de jure school segregation, the Court laid down

the basic rules which governs to this day: 'In

fashioning and effectuating the [desegregation]

decrees, the courts will be guided by equitable

principles.' Brown v. Board of Education, 349

US 294, 300 ... (Brown II)."

53 L.Ed.2d at 755.

32

The lower court fully stated the findings of fact

that require the conclusion that the State's approach to

dismantling the dual system in Nashville has not worked and

contains no prospect of working, and that the only reason

able alternative to accomplish desegregation is merger of

TSU and UTN into a single institution under a single govern

ing board, 427 F. Supp. at 654-660, and plaintiffs-intervenors

Richardson, e_t a_l. and the government have shown at length

the substantial basis in the record for these findings,

Richardson brief, pp. 21-32, government's brief, pp. 12-18,

28-32. Summarized, these findings are: The use of joint,

cooperative and exclusive program allocations in the 1974

Long Range Plan and as implemented proved completely ineffec

tive in overcoming the dual system. None of the programs

formulated by defendants worked; the only program with any

success was the graduate teacher education program ordered

by the court to be exclusively allocated to TSU (and then its

off-campus character did not result in substantial segregation

of the TSU campus). Moreover, defendants evaded the court's

B . Merger Is An Appropriate Remedy In This Case

iv

37/ The findings of fact on the nature of the constitutional

violation were summarized supra at pp. 3-4.

33

orders to develop a meaningful desegregation plan; the

division and inability of the defendants to pull together

was found "destructive." At the trial all expert testimony

supported merger as a superior alternative to the State's

program allocation approach, and even defendants' experts

agreed that merger is the best long range solution. In

addition, the former THEC Chairman and head of the Long Range

Plan monitoring committee testified that, "I think in the

future a point will be reached where a merger might be a

solution. ... My estimate would probably be five to ten

[years]" (T. 749-750, A. ). Merger was not studied nor

proposed by the Long Range Plan primarily because of the

inability of defendants— principally UT, THEC and the State

Board of Regents— to agree. The court also found that one

governing board for the merged institution, and that "merger

under the Board of Regents, with UTN supporting TSU during

the transition period ... offers the best prospect for success,"

427 F. Supp. at 560.

Lastly, the history of this case demonstrates that merger

was not ordered precipitously, and that the lower court gave

defendants many years to do what had to be done. (Indeed,

the district court deferred too long to the perogatives of

defendant State educational officials in designing a Nashville

34

desegregation plan.) It was only when the manifest refusal

of defendants to act was clear beyond any doubt that the

court reluctantly ordered what it had ordered defendants

specifically to consider doing voluntarily 4 years earlier.

The lower court very frankly recognized that the "radical"

and "extreme" nature of merger was called for by the "egre

gious Constitutional violation.

Clearly, the court met the equitable standard of

Milliken v. Bradley II, Swann and the 1972 opinion. First,

the remedy of merger was not merely related to the condition

that was in violation of the Constitution, it directly

redressed the expansion of white UTN alongside black TSU

which was one of the central hallmarks of the Tennessee dual

public higher education system, and which "impeded the dis

mantling of the dual system." Second, the merger remedy is

surely the one remedy that most nearly as possible restores

the victims of discrimination to their rightful place. The

38/

natural desegregation of TSU that the existence and expan

sion of UTN prevented from occurring is exactly what merger

will accomplish. Moreover, the court-ordered merger of TSU

and UTN will accomplish the kind of solution comparable

38/ 427 F. Supp. at 652-653, Richardson brief, pp. 16-21,

government's brief, pp. 18-28.

35

in which Memphis State University and UT's Memphis Center

39/

eventually merged. Third, there is no doubt that the

State had a full opportunity to overcome the constitutional

violation, and failed completely to act effectively.

C . THEC And UT's Objections To Merger Do Not

Demonstrate An Abuse Of Equitable Discretion.

As against the extensive factual findings which make

merger appropriate under the equitable standard applicable

to school desegregation remedies, defendants THEC and UT

seek to show abuse of discretion principally by raising a

hue and cry about the "unprecedented" nature of "forced

40/

merger." Neither of those contentions has merit.

The merger remedy is not unprecedented. The district

court expressly analyzed the analogous merger in Memphis

between Memphis State University and UT Memphis Center and

found that: "UT-N and TSU are in competition for students

just as were MSU and the UT-Memphis Center. With TSU's

black history and UT's prestige, this competition inevitably

situation in Memphis (without the racial segregation aspect)

39/ 427 F. Supp. at 653; Richardson brief, pp. 19-21;

government's brief, pp. 25-26 (includes discussion of

Chattanooga merger).

40/ See, e .g., THEC appellant brief, pp. 14, 49.

36

fosters dualism," 427 F. Supp. at 653. Nor has merger

of higher education institutions for purposes of desegrega

tion been unprecedented, see Bradley v. Board of Public

Instruction, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 117 (M.D. Fla. 1965), nor

the related remedy of enjoining construction of a rival insti

tution (as originally sought in 1968 in the instant case),

see Norris v. State Council of Higher Education, supra;

see also, Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, supra.

Indeed, the court should take judicial notice that merger

of higher education institutions is not even unusual: sta

tistics demonstrate that between 1968 and 1976, i.e ., during

the course of this lawsuit, there have been 86 cases of

42/

merger involving 209 institutions. UT makes the claim

that the decision of the D.C. Circuit in Adams v. Richardson,

supra, and the acceptance by the Department of Health,

43/

Education and Welfare are somehow contrary to merger.

However, the D.C. Circuit expressly stated that under Title

VI a good state-wide plan must give special attention to

enhancing black institutions, 427 F. Supp. at 650, n. 14,

41/

4 1/ For substantial support in the record for the lower

court's finding, see supra at p. 36, n. 39.

42/ Government's brief, p. 61, n. 140.

43/ UT appellants' brief, pp. 52-53.

37

quoting, 480 F.2d at 1164-1165, which obviously the merger

would accomplish. Moreover, the acceptance by HEW of cer

tain plans in June 1974 was vacated by the district court,

see Adams v. Califano, supra, 430 F. Supp. at 119-120 (" [T]he

Court finds that such plans did not meet important desegre

gation requirements and have failed to achieve significant

44/

progress toward higher education desegregation"). Adams

v. Califano. 430 F. Supp. at 120, again emphasized that

'"[t]he desegregation process should take into account the

unequal status of the Black colleges and the real danger

that desegregation will diminish higher education opportun

ities for Blacks.'" Pursuant to the court's order HEW has

now drafted Amended Criteria Specifying Ingredients of

Acceptable Plans to Desegregate State Systems of Public Higher

45/

Education. These criteria state, inter alia, that there

is an affirmative duty to take effective steps to eliminate

de jure segregation (citing Green, supra; Norris v. State Council

of Higher Education, supra; Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, supra. and the court's 1972 decision in the

44/ The slip opinion of this decision is also set forth as

Appendix D to the Richardson brief.

45/ 42 Federal Register 40780 (August 11, 1977).

38

instant case), and that traditionally black .colleges have

a unique role. Indeed, in listing the elements of a plan

for disestablishment of the structure of the dual system,

the criteria expressly sanction "merging institutions or

branches thereof, particularly where institutions or campuses

46/

have the same or overlapping service areas" (emphasis added).

46/ "To achieve the disestablishment of the structure of

the dual system, each plan shall:

ic Jc ic

"C. Commit the state to take specific steps to elim

inate educationally unnecessary program duplication among

traditionally black and traditionally white institutions in

the same service area. The plan shall identify existing

degree programs, major fields of study, and course duplica

tion (other than core curricula) among institutions having

identical or overlapping service areas and indicate specif

ically with respect to each area what steps the state will

take to eliminate such duplication. The elimination of such

program duplication shall be carried out consistent with the

objective of strengthening the traditionally black colleges.

"D. Commit the state to give priority consideration to

placing any new undergraduate, graduate, or professional

degree programs, courses of study, etc., which may be proposed,

at traditionally black institutions, consistent with their

missions.

* * * *

"H. Commit the state and all its involved agencies and

subdivisions to specific measures for achievement of the

above objectives. Such measures may include but are not lim

ited to establishing cooperative programs consistent with

institutional missions; reassigning specified programs, course

offerings, resources and/or services among institutions;

realigning the land grant academic programs so that research,

experiment and other educational services are redistributed on

a nonracial basis; and merging institutions or branches thereof,

particularly where institutions or campuses have the same or

39

While the HEW criteria establish only minimal standards,

whose adequacy is being challenged in the Adams v. Califano

litigation, we submit that they fully support the lower

court's exercise of equitable discretion as within commonly

accepted remedies for curing discrimination in higher educa

tion.

Nor is the concept novel in school desegregation law

generally in which "the obligation of every school district

is to terminate dual school systems at once and to operate

now and hereafter only unitary schools," Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19, 20 (1970), which as

a practical matter results in plans "to merge faculties and

staff, transportation, services, athletics and other extra

curricular activities," Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

46/ Continued

overlapping service areas. The measures taken pursuant to

this section should be consistent with the objective of

strengthening the traditionally black colleges."

(42 Federal Register at 40782-40783 (original emphasis

deleted, emphasis added).)

47/ On December 27, 1977, plaintiffs in the Adams case

filed a Motion for Order Requiring Improvement of Higher

Education Desegregation Criteria that the criteria were

otherwise inadequate. Some of counsel for plaintiffs-inter-

venors Richardson, e_t a_l. are also counsel for plaintiffs in

Adams, and will keep the court apprised of subsequent devel

opments on this motion and the Adams litigation generally.

40

Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211, 1217 (5th Cir. 1970)

(en banc). Thus, courts as a matter of course have ordered

the pairing or clustering of schools, realignment of school

assignment zones and relocation of portable school rooms as

methods for eliminating segregated schools, see, e.g.,

Cisnercs v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 467

F.2d 142, 153-154 (5th Cir. 1972). This and other circuits

have ordered interdistrict remedies where, as here,

there was a violation by several school districts, see, e.g.,

Newburg Area Council, Inc, v. Board of Education, supra;

Evans v. Buchanan, supra. Furthermore, in Wright v. Council

of City cf Emporia, supra, and United States v. Scotland

Neck City Board of Education, supra, the Supreme Court for

bade the establishment of separate or "splinter" school systems

which would impede desegregation— a mirror-image of the relief

ordered in the instant case.

Merger or consolidation types of remedies are common in

other civil rights areas. For example, segregated local

unions have been ordered merged, see, e.g., Local 189, United

Paper Makers and Workers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th

Cir. 1969); Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 310 F. Supp. 536

(E.D. La. 1970); United States v. International Longshoremen's

Assoc. , 319 F. Supp. 737 (D. Md. 1970), cf_. East Texas Motor

41

Freight v. Rodriguez, ___ U.S. ____ , 52 L.Ed.2d 453, 453

(1977) ("merger of the city and line-drivers collective bar

gaining units"). Another example is the merger of political

entities in voting rights cases, see, e.g ., White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U.S. 339 (1960); United Jewish Organization of Williamsburgh

v. Carey, ____ U.S. ____ , 51 L.Ed.2d 229 (1977); Kirksey

v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 F.2d 139 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, ____ U.S. ____ , 46 U.S.L.W. 3357 (1977).

The rhetorical claim that a "forced merger" is a per se

abuse of equitable discretion because of its interference in

the political process has no more merit under the record in

this case than defendant school boards' claims of "forced

busing" in Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa-

tion or "bizarre" educational components in Bradley v, Milliken,

supra, 540 F .2d at 236, aff'd, 53 L.Ed.2d 745. Nor is UT's

belated effort to present alternatives to merger which do not

48/

meet the peculiar problem of TSU and UTN enough. in short,

the history of the litigation and record amply demonstrate

that "[t]he District Court has ... properly enforced the

guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment consistent with [the

48/ UT appellants' brief, pp. 54, et seg.

42

Supreme Court's] prior holdings, and in a manner that does

not jeopardize the integrity of the structure or function

of state and local government," Milliken v. Bradley II,

supra, 53 L.Ed.2d at 763.

43

CONCLUSION

*

For the reasons stated above, the district court's

Nashville merger order should be affirmed.*

Respectfully submitted,Ak:mL r

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE E. FRANKLIN

RICHARD H. DINKINS

1414 Parkway Towers

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

LYNN WALKER

BILL LANN LEE

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Intervenors, Appellees

Richardson, et al. in