Stallworth v. Monsanto Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stallworth v. Monsanto Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1975. f3347ef8-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15c822f7-900a-4865-b26c-dedca51025e7/stallworth-v-monsanto-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

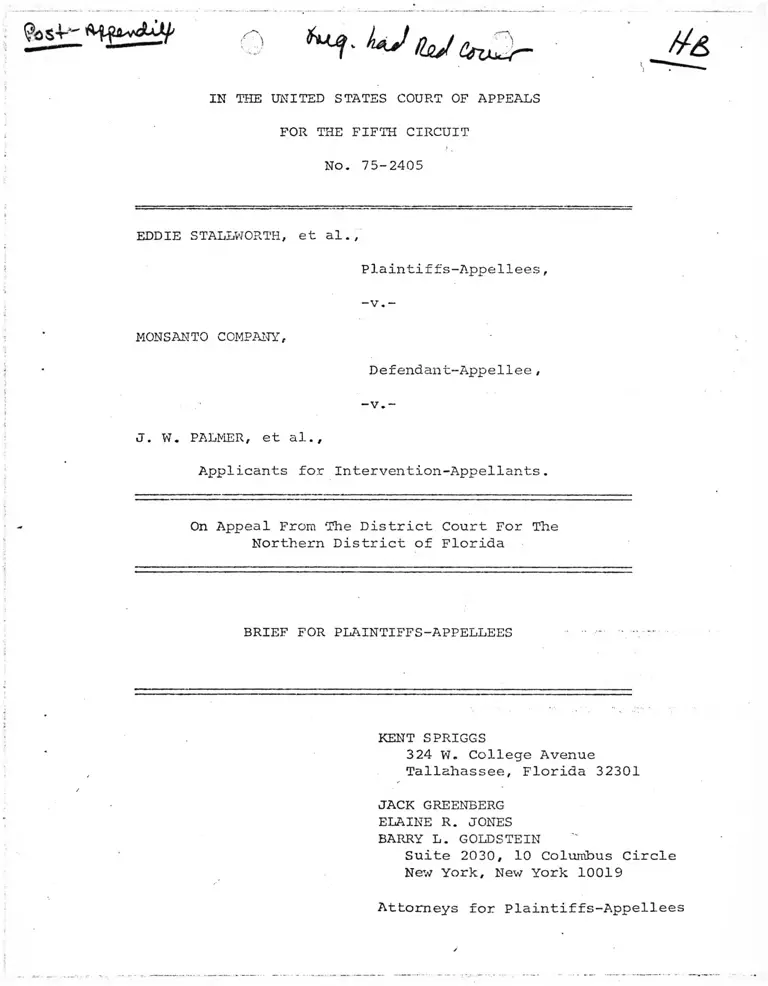

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2405

EDDIE STALLWORTH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-v. -

MONSANTO COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee ,

-v. -

J. W. PALMER, et al.,

A.pplicants for Intervention-Appellants.

On Appeal From The District Court For The

Northern District of Florida

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

KENT SPRIGGS

324 W. College Avenue

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

JACK GREENBERG

ELAINE R. JONES

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2405

EDDIE STALLWORTH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-v. -

MONSANTO COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee,

-v. -

J. W. PALMER, et al. ,

Applicants for Intervention-Appellants/

On Appeal From The District Court For The

Northern District Of Florida

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13 (a)

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellees, in con

formance with Local Rule 13 (a), certifies that the following

listed parties have an interest in the outcome of this case.

These representations are made in order that judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualifications or recusal;

Plaintiffs \

Eddie Stallworth

Angelo Moutrie

Fred Henderson

Robert Davis

Jonas Fairlie

Jesse Ford

Sam Bonham

Ernestine Young

Henry Golsten

Charles Powe

The class of black employees at Monsanto Company's Pensacola

Plant, retired or otherwise terminated black employees, and

discriminatorily rejected black job applicants represented

by plaintiffs.

Defendant

Monsanto Company

Applicants for Intervention

J. W. Palmer Bobby W. MorrisG. C. Brantley Huey CourtneyRichard S. Brown Pete BartleyE. V. Amason, Jr. W. L. PughC. B. Kelley J. W. ThompsonJames D. Roberson C. E. McLellandR. H. Woodard H. C. FowlerW. D. Roberson W. L. BingleW. S. Howell R. D. ThomasL. E. Sellers R. C. CurtisJ. D. Ingram Marucs DobsonDon S. Smith A. J. McCroskeyMarvin Sanders C. L. PayneC. E. Bryan Bill MorrisC. R. Nelson C. F. Kas tD . H. Morris M. L. ChaversH. L. McCrone R. Y. CottonL. D. Goodson Paul B. VanlenteD. H. Smith R. K. Bryan

The class of employees at Monsanto Company who have allegedly

lost seniority expectations as a result of Plaintiffs' suit,

-2-

represented by Applicants for Intervention.

Jack Greenberg

Attorney for Plaintiffs-

Appellees of Record

-3-

\TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certificate Required by Local Rule 13(a) 1

Table of Contents ..................................... i

Table of Authorities ............. ^

Statement of Question Presented ........................ j_v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. 1

ARGUMENT ............................................... 6

Introduction ...................................... 6

The Prejudice Intervention Would Cause to the

Parties and to the Orderly Processes of the

Court Amply Justifies a Determination ofUritimeliness .................................. 8

A. The Substantial Prejudice Which Would

Result from the Grant' of the Motion

..-to Intervene ........................... 8

B. The Intervening White Employees

Knew, or Should Have Known, of the Pendency of this Action

Against their Employer, but

Failed to Take Timely Steps to

Protect Their Alleged Interests ........ 15

1. The Intervenors1 Mistaken "Reliance"

on Monsanto to Present the

Position Which They Now Seek to

Advance is Unreasonable and CannotExcuse Their Failure to take TimelyAction Themselves .................. 16

2. The Intervenors1 Mistaken Under

standing of the District Court's

Jurisdiction is Unreasonable andCannot Excuse Their Failure to

Take Timely Action Themselves ...... 16

CONCLUSION 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) ... 14

Central of Georgia Ry. v. Jones, 229 F.2d 648 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied. 352 U.S. 848 (1956) ........ 20

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709

(E.D. La. 1970), aff'd, 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir.

1971) ........................................... 13

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888

(5th Cir. 1970) ................................. 11,14

Diaz v. Southern Drilling Corp., 427 F.2d 1118 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 878 (1970) ........ 6,10

English v. Seaboard Coast Line R. Co., 465 F.2d 43

(5th Cir. 1972) ................................. 21

Hobson v. Hansen, 44 F.R.D. 118 (D. D.C. 1968) ....... 19

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964) ............... 20

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974) 19

Kessler v. EEOC, 472 F.2d 1147 (5th Cir.) (en banc),

cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) 12

Marcus v. Putnam, 60 F.R.D. 441 (D. Mass. 1973)...... 11

McDonald v. E. J. Lavino Co., 430 F.2d 1065 (5th Cir.

1970) ......................................... 6,7,9

Missouri-Kansas Pipe-Line Co. v. United States, 312

U.S. 502 (1941) .......... ............... ........ . 23

NAACP v. New York, 413 U.S. 366 (1974) ........... 6,15,23

Norman v. Missouri-Pacific RR, 414 F.2a 73

(8th Cir. 1969) 20

Pg.ge

s .Petete v. Consolidated Freightways, 313 F. Supp. 1271

(N.D. Tex. 1970) ................................ 12

Quarles v. Philip Morris Co., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968) ....................................... 19

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971), cert, dism., 404 U.S. 1006 ............... 19

Smith Petroleum Service, Inc. v. Monsanto Chemical Co.,

420 F . 2d 1103 (5th Cir. 1970) ................... 6

Stadin v. Union Electric Co., 309 F.2d 912 (3d Cir.

1962) 12

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ................................... 20

United States v. Carroll County Bd. of Educ.,

427 F .2d 141 (5th Cir. 1970) .................... 10

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973) 20

United States v. U. S. Steel Corp., 371 F. Supp. 1045

(N.D. Ala. 1973), 5 EPD 8619 (N.D. Ala. 1973) .. 20

Vogler v. McCarty, 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971) ..... 20

Wooten v. Moore, 42 F.R.D. 236 (E.D. N.C. 1967), aff'd

on other grounds, 400 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1968),

cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1083 ..................... 9

Other Authorities:

3B Moore's Federal Practice 5 24.09(2] ................ 19

3B Moore's Federal Practice 5 24.13[1] ................ 6,8

7A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure § 1916 7,9

7A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure, § 1901 11

Rule 24, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ............ 6

9

iii

Page

Other Authorities (cont'd): x

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ..................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §§ 2OOOe et seq., Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (as amended 1972) .......... 2,12,14

iv

/

s

©

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, in a suit brought pursuant to Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1969 and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 to term

inate racial discrimination in employment, the district

court appropriately denied intervention of right and per

missive intervention pursuant to F.R.C.P. 24 to white

encumbent employees purporting to represent a class of em

ployees whose alleged seniority rights were modified by a

judicially-approved settlement reached by the parties, where

1. Such intervention was not sought until after

extensive discovery and hearings had been had and after the

Consent Order which settled the issue of injunctive relief

in the case had gone into effect, and

2. Intervenors do not have a legally cognizable

interest in either their alleged "seniority rights" or in

mitigating the relief in the Order complained of or in any

further Order designed to eliminate unlawful racial discrim

ination.

v

s

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2405

EDDIE STALLWORTH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-v. -

MONSANTO COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee,

-v. -

' J. W. PALMER, et al.,

Applicants for Intervention-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal by white employees of-defendant Monsanto

Company from the district court's denial of their motion to

/

intervene in a class action brought by black employees

challenging across-the-board practices of discrimination.

The white Intervenor-Appellants did not seek intervention

until after extensive discovery and evidentiary hearings

had taken place and, in particular, after a judicially

approved Consent Order settling the issues of injunctive

relief had taken effect (A. 42-58).

This action was brought under 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and

2000 e, et seq. The named plaintiffs, all black employees

of Monsanto, represent a class of more than 600 present em

ployees, former employees and rejected applicants. Plain

tiffs filed their complaint on April 13, 1973, in which they

sought declaratory and injunctive relief, including back pay (A. 27)

There had previously been filed in the same court a related

civil action styled Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v.

Monsanto Company, No. 73-31-Civ-P. ' The two cases were conso

lidated for trial. The E.E.O.C. participated actively in the

proceedings against Monsanto and is a party to the order of

March 7, 1975, to which Intervenors object (A. 42); however, the

E.E.O.C.1s case, No. 73-31, was dismissed for lack of juris

diction on March 12, 1975, and its motion to intervene in the

instant case, No. 73-45, was denied on March 17, 1975.

Discovery and pre-trial proceedings have been extensive

in this case, resulting in a voluminous and detailed record

(A. 1-26).

The parties appeared before the court on at least six different

occasions prior to March 1, 1975. At one evidentiary hearing

on July 30-31, 1974, concerning plaintiffs' motions for pre

liminary injunction and partial summary judgment, the court

heard approximately eight witnesses and received substantial

documentary evidence (A. 10). On September 12, 1974, the court

enjoined certain aspects of Monsanto's testing and educational

requirements which the court found to be unlawful and granted

the plaintiffs motion for summary judgment with respect to

those practices. As to other issues presented by the plain-

motions, the court made no affirmative findings and

reserved the issues for trial.

On December 26, 1974, the court filed a pre-trial Order

setting the case for trial beginning March 3, 1975, and sche

duling further pre-trial proceedings. At a pre-trial con

ference held on February 24, 1975, the court expressed the

desire that the case be concluded within the month set aside

for trial but indicated that if additional time were necessary

the court would seek to make such time available. Further,

the parties agreed to explore the possibility of settling

some of the issues of the case. .

With the court's permission, during the week of March 3,

1975, the parties attempted to settle some of the issues in

the case before proceeding to trial, and intensive negotiations

3

s

were conducted. Counsel apprised the court of developments

during that week but no evidentiary hearings were held. As

a result of the week-long negotiations, the parties jointly

submitted an order to the court which it signed and adopted

on March 7, 1975 (A. 42-58). The Order includes detailed

injunctive provisions which, by agreement of the parties,

resolved plaintiffs' (and E.E.O.C.'s) claims for injunctive

relief, but left open their claims for declaratory and

monetary relief.

In particular, the Order provided for: (1) The appoint

ment of an industrial psychologist to supervise the remedial

training and advancement of plaintiffs and their class; (2)

Modification of Monsanto's "Prior Request System" for new job

openings; (3) Affirmative action programs for supervisor, cleri

cal and technical employees; (4) Replacement of "group"

seniority with "plant" seniority in the major departments of

the facility; (5) Red-circling and procedures for transfer

by members of the class; (6) Review of determination of

medical qualifications; (7) Resumption of use of the Mechani

cal Assessment Program and continuance of Monsanto's affirma

tive action in hiring; and (8) Compliance reports.

It is this Consent Order,which resolved some of the com

plex issues in the suit, ' that the intervenors wish to challenge

4

The court evidently considered entry of the Order a

watershed in the suit. After rendering decision on March 20,

1975, on the issue of laches with respect to plaintiffs'

■ claims of bach pay, the court, on March 24, 1975, referred all

issues not previously decided to a Special Master. The de-

Order made by the court for the guidance of the Master

indicates that the purpose of the action was to relieve the

court of some of its burden and to speed the case along (the

judge noted that he was the only one in a two-judge district),

that referral would not have taken place but for the

March 7 Consent Judgment.

Meanwhile, the March 7, 1975 Consent Order had entered

into effect. Intervenors claim that because of this Order

Vthey were temporarily displaced from jobs which they would

have retained during a rollback had the discriminatory group

seniority system not been eliminated. Only at this point,

on April 4, 1975, did Intervenors, who should have sought to

protect their alleged seniority expectations much earlier,

seek to present their position in this litigation. The dis

trict court properly denied the intervention as untimely

(A. 129-31).

1/ See the July 21, 1975 Affidavit of K.C. Beene, Personnel

& Industrial Relations Superintendent at the Company's

Pensacola Plant, accompanying Defendants' Response to

Intervenors' Renewed Motion to Intervene, in which it is

stated that all applicants for intervention have been returned to their former positions.

5

ARGUMENT

Introduction

/

Application pursuant to Rule 24, F.R.C.P. , for both inter

vention as of right and by leave of court must first be timely

made, irrespective of the satisfaction of the other require

ments for intervention. Timeliness is to be determined by the

district court in the exercise of its sound discretion. NAACP

v. New York, 413 U.S. 366 (1973); McDonald v. E.J. Lavino Co.,

430 F.2d 1065 (5th Cir. 1970). District courts consider the

following pertinent factors; (1) The amount of time during

which the intervenor knew, or should have known, of his

interest in the suit without acting, and the steps he eventu

ally does take to protect his interest; (2) The harm or pre

judice that results to the rights of the parties by delay;

and (3) unusual circumstances warranting intervention. NAACP

v. New York, supra, at 365-69; Diaz v. Southern Drilling

Corp., 427 F.2d 1118, 1125 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 400

U.S. 878 (1970). This court has repeatedly indicated that

prejudice caused to the parties is the more important - if not

the only - consideration. Smith Petroleum Service, Inc, v.

Monsanto Chemical Co., 420 F.2d 1103, 1115 (5th Cir. 1970);

McDonald v. E.J. Lavino Co., supra. See 3B Moore's Federal

Practice 5[24.13[1], at 24-523 (1974).

In addition, a motion to intervene introduced after

6

•; ) i

judgment is looked upon by the courts with a jaundiced eye

and a strong showing is required before such a motion is

granted. McDonald v. E.J. Lavino Co., supra, at 1072;

7A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure §1916,

at 579-81.

After careful consideration of these and other issues

raised by counsel, the district judge determined that neither

intervention of right nor permissive intervention should be

allowed in the case at this point (A. 129-31). The prejudice that intei

vention would cause both to the parties and to the orderly

processes of the court, as well as appellant's inexcusable

delay in seeking intervention, amply justify this exercise

2/of the lower court's discretion.

..... ‘ /____________________ f

i

2 / Since a determination of untimeliness with respect to a

motion to intervene of right a_ fortiori compels a finding

that an alternative motion for permissive intervention

is untimely, this discussion will be directed to the

motion to intervene of right and not otherwise deal with the timeliness of appellants' motion for permissive intervention. See, e.q., McDonald v. E.J. Lavino Co.,

supra, at 1073; 3B Moore's Federal Practice 5(24.13 [1], at 24-522.

7

t

THE PREJUDICE INTERVENTION WOULD

CAUSE TO THE PARTIES AND TO THE

ORDERLY PROCESSES OF THE COURT

AMPLY JUSTIFIES A DETERMINATION

OF UNTIMELINESS

A. The Substantial Prejudice Which Would Result

from the Grant of the Motion to Intervene.

The Appellants sought intervention two years after insti

tution of the suit, at a point subsequent to determination of

class-wide discrimination, entry of a complex decree of injunc

tive relief, resolution of the issue of laches and reference

of a number of issues to a Special Master (A. 129-31). The

applicants for intervention seek in effect to reopen the issue

of injunctive relief after such relief has been implemented,

and after full discovery and hearings have been had, and to

leave the black employees without remedy while the issues are

relitigated. The lower court determined, that to allow these

white employees to intervene in order to contest the March 7,

1975 Consent Order,

with time taken for the filing of pleadings,

for discovery needed on their asserted claims and for trial thereof, will of necessity slow . down and impede the progress of this lawsuit,

already too long delayed, in moving to con

clusion. (A. 130) 3/ .

3/ In general, where there has been much litigation by

way of motions,- depositions, taking of testimony

before a Master, etc., tardy intervention is usually

denied. 3B Moore's Federal Practice 3[24-13[l], at 24-523.

8

I

The circumstances here are similar to those in Wooten v.

Moore, 42 F.R.D. 236 (E.D.N.C. 1967), aff'd on other grounds,

400 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1968), cert. denied, 393 U.S. 1083,

where intervention by the United States was denied for

untimeliness two years after the suit had begun, where the

issue for decision had been ripe for twenty-three months,

numerous depositions, interrogatories and admissions had been

made or requested, a pre-trial hearing had occurred a year

prior, and additional pleadings would result from a grant of

intervention. Intervenors, Palmer, et al., do not even discuss

the prejudice that intervention at this point would cause the

parties.

The motion to intervene here raises the same problems

a motion to intervene after judgment does. Such motions re

quire a strong showing for approval not only because of the

likelihood of prejudice to the parties, but also because of

the danger of substantial interference with the orderly

processes of the court. McDonald v. E.J. Lavino Co., supra,

at 1072; 7A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure

§1916, at 579-81. McDonald involved the post-judgment inter

vention of right of a workmen’s compensation carrier in an

injured employee's suit against a third-party tort-feasor

for the purpose of protecting its right of subrogation to

the as yet undistributed fund. In finding the application

9

V o 1 >. —'

timely, this Court noted the "minor" inconvenience this would

cause the lower court and the limited, technical purpose of

the motion. It considered it "significant that [the compen

sation carrier] was not attempting to reopen or litigate

any issue which had previously been determined." Id. at 1065.

Similarly, in Diaz v. Southern Drilling Corp., supra, the

United States sought to intervene of right before trial to

assert a tax lien. This Court noted that

[a]t the time of the intervention, there had been no legally significant proceedings

in the second of the two lawsuits [the only one which concerned the United States]

other than completion of discovery and a

pretrial that determined that there were

to be two separate suits. There is no

showing of any delay in the process of the

overall litigation by the Government's

filing of its application at the time it

did. l[d. at 1125.

In the case at bar, where the most significant issues had

already been determined prior to application for intervention,

and where delay was certain if the motion was granted, the

district court really had no choice but to deny the motion.

Compare United States v, Carroll County Bd. of Educ., 427 F.2d

141 (5th Cir. 1970), which affirmed denial of intervention as

untimely in a five-year old school desegregation case where

intervention had not been sought until after a judicially

approved desegregation plan had been put into effect. See

10

)

also Marcus v. Putnam, 60 F.R.D. 441 (D. Mass. 1973).

The interests of these white employees in stating their

case in this litigation is clearly outweighed by the interests

of the plaintiff black workers, for whom delay means further

. 5 /irreparable injury, in a speedy conclusion of the action.

In addition, there is also a public interest in the efficient

resolution of controversies. 7A Wright & Miller, Federal

Practice & Procedure §1901, at 465. Moreover, Congress expli

citly provided that Title VII cases, because of the paramount

Intervention in Marcus was denied in a shareholder's deri

vative suit when it was not sought until one day prior to the two-month cut-off for making objections to a proposed

settlement which had been arrived at only after lengthy

negotiations and pre-trial discovery. The prejudice

delay would cause to the rights of the stockholders of

the funds involved and to the funds themselves motivated

the court's decision.

5/ C_f. Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co. , 421 F.2d 888, 894(5th Cir. 1970). Note that none of the intervening white

employees can even allege any .continuing harm, since —

they have all been returned to the jobs they formerly

held. See note 1, supra.

i

public interest in terminating employment discrimination, <

should be expeditiously processed in the district court.

42 U.S.C. §2000e - f (4) (5) .

The maintenance or manageability of Title VII action is

a real and substantial problem. Even at present it is diffi

cult enough, as a result of the complexity and cost of Title

VII litigation, for individuals with Title VII claims to find

competent counsel:

The courts of this Circuit have previously found that competent lawyers are not eager to enter the fray in behalf of a person

who is seeking redress under Title VII.

This is true even though provision is made

for payment of attorneys' fees in the

event of success. . In the case of Petete

v. Consolidated Freight Ways, 313 F.Supp.

1271 (D.C.N.D. Tex. 1970), the court

found that further complicating plain

tiff's problem has been the reluctance

of the attorneys she has approached to

undertake the specific and complex challenges of a Title VII lawsuit which are not common to more frequently liti

gated areas of the law. (citations

omitted) Kessler v. E.E.O.C., 472 F.2d 1147, 1152 (5th Cir.), (en banc), cert. denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973).

In Title VII cases, more so than in many other cases, ,

Additional parties always take addi

tional time. They are the source of

additional questions, objections,

briefs, arguments, motions and the

like which tend to make the proceed

ing a Donnybrook Fair. Stadin v.

Union Electric Company, 309..F,2d 912,.

12

920 (3rd Cir. 1962). /

Furthermore, counsel for plaintiffs typically handle

Title VII actions on a contingency fee basis: if the

7/plaintiffs prevail, attorneys' fees are generally awarded.

Intervention in this case to reopen the settled issue of

injunctive relief is likely to result in litigation costs

substantially greater than what they would have been had

8/Intervenors come in earlier. It should be noted that, as

6/

6/ If intervention of white employees who are allegedly

disadvantaged by the change in seniority policy is

allowed, it would follow that whites and other groups

who benefit from the change should also be allowed

to come in, as Defendant Monsanto suggests in its

Response to Appellants Motion to Intervene. The

possibility of further delay and complication is evident.

7/ See Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F.Supp. 709

(E.D. La. 1970), aff'd, 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971).

8/ With respect to attorneys' fees, the district court

expressed concern in its March 24, 1975 Order over

the amount of time consumed in this

case and whether the parties have

spent, or will spend, unnecessary

time and have incurred, or will

incur, unnecessary expense in

presentation of the case ... Id.

at 6-7.

13

a practical matter, it would be difficult to recover attorneys'

fees or costs from intervening white employees.

Finally, it should be noted that the addition through

intervention of parties who do not have any liability under

9/Title VII will generally make the resolution of Title VII

suits through negotiation and settlement extremely diffi-

10/cult. These problems are aggravated, of course, where

intervention by such parties is not sought until after

settlement has been reached.

9/ Title VII applies to "employers", "labor organizations,"

"employment agencies" and "joint labor management

committees." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2.

Cf. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974).

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., supra, at 891.10/

B. The Intervening White Employees Knew, or Should

Have Known, of the Pendency of This Action Against

Their Employer, but Failed to Take Timely Steps,

to Protect Their Alleged Interests.______________

As the Supreme Court has emphatically stated,

[T]imeliness is to be determined from all the

circumstances. And it is to be determined by

the court in the exercise of its sound discre

tion, unless that discretion is abused the

court's ruling will not be disturbed on review,

(footnotes omitted)

NAACP v. New York, supra, at 366.

When, as here, intervention would substantially prejudice

the interests of the parties and the orderly process of the

administration of the court's business, the intervenors have

a considerable burden to overcome. The Supreme Court indicated

that in an evaluation of timeliness, it is appropriate to

examine the point at which the appellants "knew or should have

known of the pendency of the ... action . . . , " the steps taken

by intervenors to protect their interests, and the reasons, if

any, for the intervenors' tardiness in asserting their position.

Id. at 366-67. Here, as the district court found, the interven

ing white employees "do not deny knowledge of the pendency of

the suit, nor is it reasonable to assume they did not know about

15

• oV

it." (A. 130) Applicants for Intervention do not seriously

contest this finding. Rather, they rely on two "excuses" for

not having asserted their position in a timely manner:

(1) their disappointed belief that they could rely on Monsanto

to assert their position; and (2) their false assumption that

the trial court was without power under Title VII to replace

group with plant seniority. Brief for Appellants at p. 8 .

These excuses are without basis in fact or law, and assuredly

provide no grounds for this Court to find that the denial of

intervention as untimely was a clear abuse of discretion.

1. The Intervenors1 Mistaken "Reliance" on Monsanto

to Present the Position Which They Now Seek to

Advance Is Unreasonable and Cannot Excuse Their

Failure to Take Timely Action Themselves._______

Intervenors argue that "[a]t no time did [they] have any

reason to believe that the Company would not live up to its

commitment to its white encumbent workers..." (Brief for

Appellants 4), and that they "had absolutely no way of knowing

that Defendant Monsanto Company would not protect their rights

11/ .

11/ At one point in their brief Intervenors-Appellants

suggest that this findings is "clearly erroneous." (Brief

for Appellants at 6) They cite in support of this con

tention Affidavits executed by three Applicants for

Intervention (A. 62, 67, 72). But these affidavits

were evidently carefully worded to avoid any assertion

that the applicants did not know of the suit— a point

which the district .court did not fail to recognize.

16

•

until the actual entry of the consent judgment in this case."

Id. at 7. Appellants further complain that they "had no advance

warning whatsoever that the Company would completely capitulate

and agree to ... an order ... which totally eliminated [their]

hard-earned group seniority rights." Id. at 8 .

Monsanto had no obligation to represent the special

interests of its white encumbent employees. On the contrary,

the Company had a legal obligation not to engage in discrimina

tory employment practices. After protracted litigation and a

preliminary finding of unlawful practices by the district court

(see supra, p. 3), Monsanto realized that it would be appro

priate to agree to certain well-established remedies designed to

terminate the effects of its discriminatory practices. It is to

be expected (and in fact it is the design of Title VII) that an

employer confronted with proof of employment discrimination will

resolve the complex issues involved through settlement. It would

be contrary to the Company's self-interest (and contrary to the

law) to resist compliance to the bitter end, regardless of the

desires and "expectancies" of encumbent whites who benefited

from the discriminatory status quo.

To permit white employees to remain outside a discrimination

suit until such time as their employer ceases active defense and

enters into a settlement, and then allow intervention, would

17

unreasonably disrupt and discourage conciliation and settle

ment .

y—7

The intervening white employees appear to have based their

expectation that the Company would defend the status quo partly

on a so-called "commitment" of the Company not to affect their

seniority "rights." Brief of Appellants at 4, 8. In particular,

they allege in their complaint that Monsanto's employee rela

tions pamphlet, You and Your Future with Monsanto Textiles

Company, Pensacola Plant, which discusses plant and group sen

iority at 28-32, is a binding contract between the Company and

each individual employee (there is no union at Monsanto)

(A. 132-39) .

This pamphlet is no more than a unilateral declaration of

management policy and practice, and provides the worker with

all the "advance warning" he needs in its very first sentence

that Monsanto reserves the right to "constantly revis[e] its

policies to provide maximum benefit to the individual employee."

Ibid. It is certainly reasonable for a Company desirous of end

ing the discriminatory effects of group seniority to eliminate

it completely and start afresh, rather than installing, for

example, a complex combination of group.- and plant. seniority, itself

based on color, which would be difficult to administer and would

emphasize racial differences. This is especially true where

18

the Company could have instituted this change in a completely

12/

independent and unilaterial policy change.

Even if the pamphlet is interpreted as embodying a contract,

"[t]he rights assured by Title VII are not rights which can be

bargained away ..." Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791,

799 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, denied. 404 U.S. 1006, 1007. This

Court has held that the very fact that a union or employer is

a party to a discriminatory contract is enough to constitute a

violation of Title VII. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co..

491 F.2d 1364, 1381-82 (5th Cir. 1974). Contractual seniority

"rights," no matter how hard-earned, "are not vested, indefeasible

rights. They are expectancies derived from the collective bar

gaining agreement, and are subject to modification." Quarles

v. Philip Morris Co.. 279 F. Supp. 505, 520 (E.D. Va. 1968);

12/ Reliance on this pamphlet as a source of "binding seniority

rights" is so unfounded that the intervening white employees

cannot be said to have satisfied Rule 24(a)'s requirement

of a "direct, substantial, legally protectable interest in

the proceedings." 3B Moore's Federal Practice 5 24.09[2],

at 24-301, citing Hobson v. Hansen. 44 F.R.D. 18, 24 (D. D.C.

1968) (Wright, J.). Even more insubstantial is the complaint

of "reverse discrimination" by these white employees, who

seem to feel that any change in Monsanto's seniority policy,,

which has been adjudged discriminatory by the district

court, is beyond the power of the court to approve. (See pp.

20-21, infra.) To justify intervention at the closing

stages of the proceedings, intervenors should be required

to make a much stronger showing of a '"direct, substantial,

legally protectable interest" than they have.

19

Norman v. Missouri-Pacific RR, 414.F.2d 73, 85 (8th Cir. 1969).

Cf. Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964); Central of Georgia

Ry. v. Jones, 229 F.2d 648 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 352 U.S.

848 (1956).

2. The Intervenors' Mistaken Understanding of the

District Court's Jurisdiction is Unreasonable

and Cannot Excuse Their Failure to Take Timely

Action Themselves. _____________

Intervenors' second excuse for delay is that they "cannot

be charged with the knowledge that the district court would

exceed the authority granted to it by Title VII and completely

destroy the group seniority system regardless of the extent of

prior racial discrimination." Brief for Appellants 10; Complaint

in Intervention at 5 24. A district court sitting in equity has

wide power to insure that Title VII works in fact to end discrim

ination in employment. United States v, Georgia Power Co., 474

F.2d 906, 927 (5th Cir. 1973); Vogler v. McCarty, 451 F.2d 1236,

1238-39 (5th Cir. 1971). It may order institution of a uniform

system of plant seniority if that is required to insure effective

and administratively feasible relief from the discriminatory

'13/

effects of a group seniority system. For example, in United

14/

States v. United States Steel Corporation, the court ordered

13/ Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1, 15, 21 (1971.) .

14/ 371 F. Supp. 1045, 1056 (N.D. Ala. 1973), 5 E.P.D. 51 8619,

at 7816-17 (N.D. Ala. 1973) (order issued) .

- 20 -

the replacement of occupational line of promotion and depart

mental seniority with plant seniority. That the seniority

expectancies of some white workers relative to other white

workers may be modified by change in a company's seniority system

does not render such a remedy illegal. This is particularly

so where the change was agreed to by the Company, which, unbound

by any collective bargaining contract, was free to make any

changes it wished as a matter of management policy.

Finally, the Intervenor-Appellants assert that the district

court lacked jurisdiction to affect the seniority expectancies

of white incumbent workers who are not parties to the action.

Complaint in Intervention 51 24; cf. Brief for Appellants 10.

This contention, however, was laid to rest in English v. Seaboard

Coast Line R. Co., 465 F.2d 43, 46 (5th Cir. 1972), where the

plenary powers of the court to eradicate all vestiges of racial

discrimination, even where white employees were not joined, was

affirmed.

CONCLUSION

Of the various factors to be assessed in determining

the timeliness of an application to intervene, prejudice

to the parties is one of the most important. The inter

vening white employees do not contest that throwing open

the Consent Order which settled the issue of injunctive

relief to further litigation at this point would cause

substantial expense and delay the relief for which plain

tiffs have been waiting much longer than the two years this

suit has been pending.

The likelihood of substantial interference with the

orderly processes of the court should intervention be per

mitted is also evident. This case was settled in large part

by the Consent Order and referred to a Special Master on

the strength of such Order. Reopening the Order for liti

gation could substantially disrupt the procedures by which

this case is finally drawing to a close.

Finally, there is no excuse for the tardiness of the

intervening white employees. Not only can they cite to no

evidence in support of their contention that they did not

know of the pendency of the suit, their whole reliance argu

ment presupposes such knowledge. In addition, the objective

circumstances surrounding a major discrimination suit against

22

their employer compel the conclusion that Intervenors "should

have known" of the action long before entry into effect of

the consent decree. NAACP v. New York, supra, at 366. The

conclusion is inescapable that Intervenors knew of the

suit in time to make a proper application to the court, but

preferred to take no action and remain uninvolved until too

late.

Plainly enough, the circumstances

under which interested outsiders

should be allowed to become participants in a litigation,

is [sic], barring very special

circumstances, a matter for the

nisi prius court.Missouri-Kansas Pipe-Line Co. v.

United States, 312 U.S. 502, 506

(1941).

The trial court determined that interventions would be

untimely in this case, and this determination should be

upheld.

WHEREFORE, the denial of intervention by the District Court

should be affirmed. ■ — •• -

Respectfully submitted,

KENT SPRIGGS

324 W. College Avenue

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

JACK GREENBERG

ELAINE R. JONES

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

23