LDF File Brief to Supreme Court to Vacate Jesse Fowler Death Sentence

Press Release

December 13, 1974

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. LDF File Brief to Supreme Court to Vacate Jesse Fowler Death Sentence, 1974. b617e801-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15d54345-da84-49be-979e-a98c2a96bff4/ldf-file-brief-to-supreme-court-to-vacate-jesse-fowler-death-sentence. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

75)

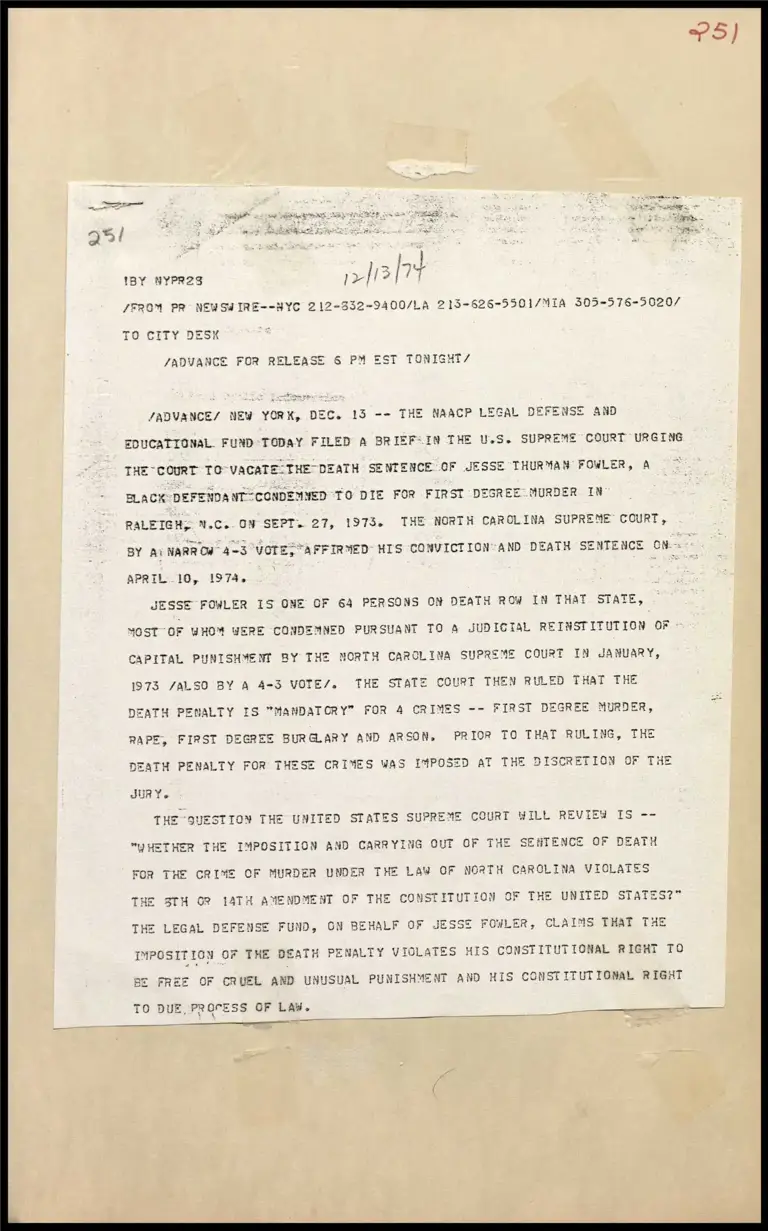

IBY NYPR2S rfi3]

/ADVANCE FOR RELEASE 6 PM EST TONIGHT/

/ADVANCE/ NEW YORK, DEC. 13 -- THE NAACP LEGAL DE ENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL. FUND TODAY FILED A BRIEF-IN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT URGING

THE COuRT TO VACATE:THE-DEATH SENTENCE OF JESSE THURMAN FOWLER, A

BLACK DEFENDANT = CONDEMNED TO DIE FOR FIRST DEGREE MURDER IN

RALEIGH, N.C. ON SEPT. 27, 1973. THE NORTH CAROLINA SUPREME COURT,

BY Ay NARROW 4-3 VOTE, AFFIRMED HIS CONVICTION AND DEATH SENTENCE CN

APRIL .10, 1974.

JESSE FOWLER 1S ONE OF 64 PERSONS ON DEATH ROW IN THAT STATE,

MOST oF WHOM WERE CONDE iE D PURSUANT TO A JUDICIAL REINSTITUTION OF

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT BY THE NORTH C > ROLINA SUPREME COURT IN JANUARY,

1973 /ALSO BY A 4-3 VOTE/, THE STATE COURT THEN RULED THAT THE

IS "MANDATORY" FOR 4 CRIMES -- FIRST DEGREE MURDER,

FIRST DEGREE BURGLARY AND ARSON. PRIOR TO THAT RULING, THE

D STATES SUPREME COURT WILL }

THE IMPOSITION AND CARRYING OUT OF THE SENTENCE OF DEATH

= Q Eo}

— fq

Q RIMS OF MURDER UNDE THE Law OF NORTH CAROLINA VICLATES

THE STH OR 14TH AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES?”

IMPOSITION OF THE DEATH

BE PREE OF CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHME!

THE DEFENDANT. WAS CONVICTED ENTENCED TO DIE FOR THE muRDE >

JOHN GRIFFIN. “DURING: THE COURSE OF HIS TRIAL, JESSE FOWLER TESTIFIED

AND’ PRESENTED WITNESSES ON HIS OWN BEHALF, BUT THE JURY REJECTED HIS

SELF DEFENSE CLAIM AND CONVICTED HIM OF FIRST DEGREE MURDER. THE

TRIAL COURT ALSO INSTRUCTED THE JURY THAT IT COULD, AS AN

ALTERNATIVE, FIND HIM GUILTY OF SECOND DEGREE MURDER OR MANSLAUGH

PEGGY DAVIS AND DAVID KENDALL, LEGAL DEFENSE FUND STAF F LAWYERS

SPECIALIZING IN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT CASES, NOTED -- "THIS IS THE

FIRST TIME A DEATH SENTENCE IS BEING CHALLENGED ON THE MERITS IN

THE“U-S.. SUPREME COURT SINCE THE FURMAN DECISION OF JUNE 29, 1972.”

“THE. PRESENT CASE,” THEY ADD, “APPEARS TO BE SIGNIFICANT BECauUSz

Tt RAISES ISSUES COMMON TO THOSE PRESENTED IN 187 CASES IN 17

STATES: -- AND, IN-PARTICULAR, TO THE 64 NORTH CAROLINA CASES,”

INS THE FURMAN RULING, ARISING OUT OF THE LEGAL DEFENSE FUND CASES

/COLLECTIVELY CALLED FURMAN V. GEORGIA/, THE HIGH COURT HELD THAT

THE DEATH PENALTY IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL WHEN THE SENTENCING AUTHOR ITY

IS FREE TO DECIDE BETWEEN DEATH AND SOME LESSER PENALTY. THE FURMAN

DECISION, WHICH HELD THIS FORM OF DEATH PENALTY TO RE "CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT,” SPARED THE LIVES OF 631 ON DEATH ROWS.

IN THE INTERVENING 2-1/2 YEARS, SINCE FUR4AN, SO STATES HAVE

REINSTITUTED CAPITAL PUNISHMENT STATUTES, ASSUMING THAT THE STATUTES

COULD MEET CONSTITUTIONAL REQUIREYENTS 3Y IMPOSING STANDARDS TO

CONTROL JURY DISCRETION OR BY MAKING THE DEATH PENALTY AUTOMATIC

UPON CONVICTION OF CERTAIN CRIMES EN LHE NT CaSE, THE DEATH

SENTENCE WAS REINSTITUTED JUDICIALLY BY A STATE SUPREME COURT.

NOTE -- THE LEGAL DEFENSE FUND IS A COMPLETELY SEPARATE

CAGANIZATION EVEN THOUGH IT WAS ESTABLISHED BY THE Naacp AND THOSE

INITIALS ARE RETAINED IN ETS NAME. THE CORRECT DESIGNATION IS NAACP

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., FREQUENTLY SHORTENED To

FUND.

/CONTACT 77> PEGGY DAVIS OR DAVID KENDALL OF LEGAL DEFENSE FuND AT