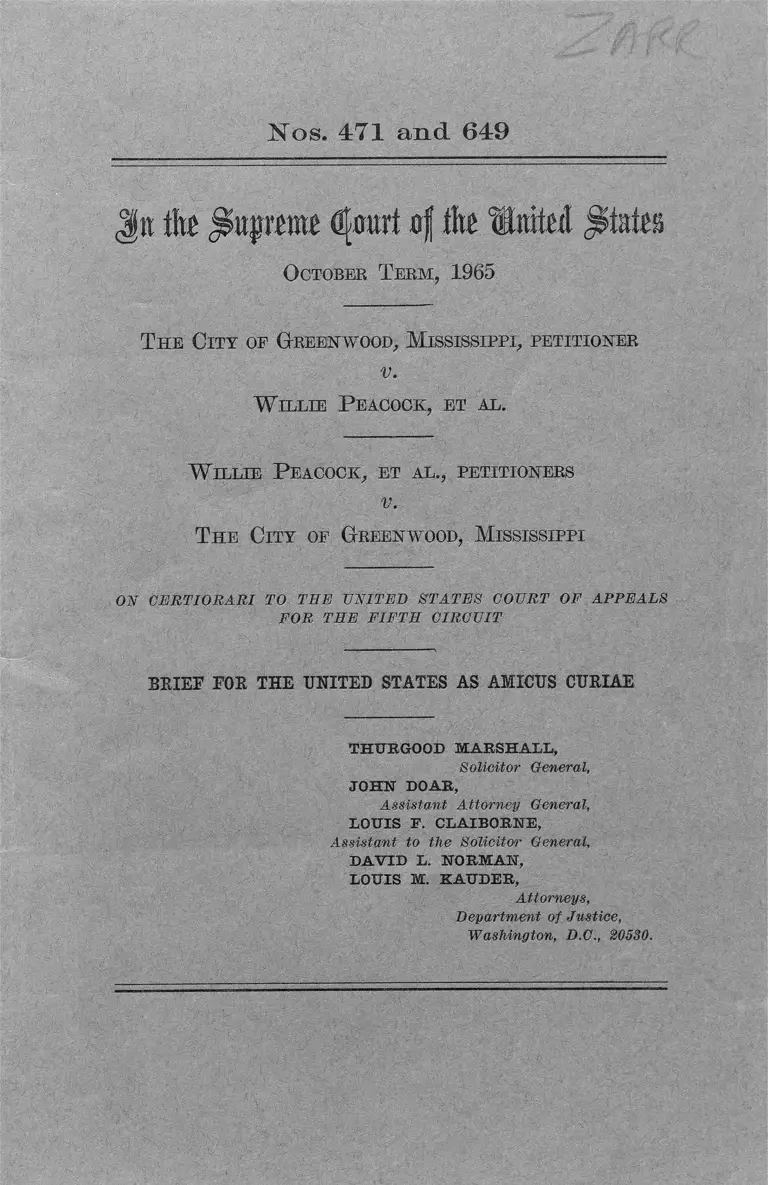

City of Greenwood, MS v. Peacock Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Greenwood, MS v. Peacock Brief Amicus Curiae, 1966. 3b23e2a6-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15db4017-a643-4633-bba9-8c79adc06168/city-of-greenwood-ms-v-peacock-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 471 and 649

J tt the Jsujjreme f̂ rrarf of the United p lates

October T erm , 1965

T h e City of Greenwood, M ississippi, petitioner

v.

W illie P eacock, et al.

W ill ie P eacock, et al., petitioners

v.

T h e City of G reenwood, M ississippi

ON C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E U N ITED S T A T E S COURT OF A P P E A L S

F O R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

THURGOOD m a r s h a l l ,

Solicitor General,

JO H N DQAR,

A ssis ta n t A tto rney General,

LO U IS F. C LA IB O RN E,

A ssis ta n t to th e Solicitor General,

D A V ID L. N ORM A N,

LO U IS M. K A U D E R ,

A ttorneys,

D epartm ent o f Justice ,

W ashington, D.C., 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below_ ___________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction________________________________________ 1

Statute involved____________________________________ 2

Questions presented_________________________________ 2

Interest of the United States_________________________ 3

Statement_________________________________________ 3

Argument:

Introduction and Summary____________ _________ 8

A. The “denial” provision of the removal statute (28

U.S.C. 1443(1)) permits pre-trial relief against

discriminatory and repressive prosecutions____ 21

B. The “color of authority” provision of the removal

statute (28 U.S.C. 1443(2)) is available to

private defendants, _______________________ 36

C. The removal statute protects all rights to equality

free of racial discrimination, and the associated

rights of advocacy and protest_______________ 53

D. The removal petitioners are entitled to an oppor

tunity to show a right of removal under both

paragraphs of Section 1443__________________ 57

Conclusion_________________________________________ 59

CITATIONS

Cases:

Baines v. Danville, No. 9080, decided January 21,

1966 (C.A. 4), petition for certiorari pending, No.

959, this term-------------------------------------------- 21, 28, 36

Bell v. Hood, U.S. 327 U.S. 678___________________ 35

Blyew v. United States, 13 Wall. 581_______________ 38

Brown v. Louisiana, No. 41, October Term, 1965,

decided February 23, 1966_____________________ 25

Burton v. Wilmington Pkg. Auth., 365 U.S. 715_____ 42

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110__________________ 22, 33

Cameron v. Johnson, 381 U.S. 741_________________ 11

City oj Chester v. Anderson, 347 F. 2d 823 petit on for

certiorari pending, No. 443, this term___________ 36

City oj Clarksdale v. Gertge, 237 F. Supp. 213____ 1, 7, 40

212-260—-66---1 (I)

IX

Cases—Continued p»g»

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3-------------------------------- 42

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. 264--------------------------- 47

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U.S. 510---------------------------- 38, 51

Cox v. Louisiana, 347 F. 2d 679---------------------------- 37

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536----------------------------- 25

DeBusk v. Harvin, 212 F. 2d 143-------------------------- 32

Dilworth v. Rines, 343 F. 2d 226---------------------------- 25

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479----------------------- 11, 26

England v. Medical Examiners, 375 U.S. 411------- 13, 32, 33"

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651-------------------------- 42,48

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391_______________________ H, 13

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903------------------------------ 42

Georgia v. Rachel, No. 147, this Term----------------- 3, 26, 37

In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1--------------------------------------- 46

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U.S. 1----------------------------- 22, 44

McDonnell v. Wasenmiller, 74 F. 2d 320----------------- 32

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668----------- 9

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304----------------- 47

Maryland v. Soper (No. 2), 270 U.S. 36------------------ 34

Maryland v. Soper (No. 1), 270 U.S. 9--------------------34, 51

Mayor, The v. Cooper, 6 Wall. 247--------------------- U, 34, 48.

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167---------------------------- 9, 41, 43

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U.S. 101------------------------ 33

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288_____________ 56.

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415----------------------- 32, 56

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370------------------------------ 22

New York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255, certiorari de

nied, 380 U.S. 977____________________________ 36, 43

O’Campo v. Hardisty 262 F. 2d 621------------------------ 32

Petersen v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244------------------------ 42

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336---------------------------- 37

Sam Fox Publishing Co. v. United States, 366 U.S. 683, 34

School v. New York Life Ins. Co., 79 F. Supp. 463----- 32

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91----------------------- 41

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 592------------------------- 33

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303-------------- 14, 22, 54

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U.S. 257-------------- U, 34, 39, 48, 52,

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461------------------------------- 42,

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299--------------------- 41,

Cases—Continued Pag6

United States v. Guest, No. 65, this Term___________ 42

United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383______________ 46, 55

United States v. Price, Nos. 59 and 60, this Term, de

cided March 28, 1966__________________________40, 46

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70_____________ 40

Venable v. Richards, 105 U.S. 636________________ 38

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313_______ 18, 21, 22, 23, 27,44

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213_____________ 33

Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 97________ ____ 41

U.S. Constitution:

Article III:

§ 1 , ------------------------------------------------- 48

§ 2, cl. 1----------------------------------------------------- 48

First Amendment___________________________ 4, 7, 51, 56

Fourteenth Amendment_______________ 4, 7, 20, 42, 51, 56

Fifteenth Amendment___________________________ 56

Statutes and Rules:

Act of March 3, 1863, 12 Stat. 755________________ 32

Act of March 3, 1865, 13 Stat. 507________________ 53

Act ol July 13, 1866, 14 Stat. 98___________________ 39,41

Act of July 16, 1866, 14 Stat, 173_________________ 53

Act of September 24, 1789, 1 Stat. 73_____________ 39

Amendatory Act of February 28, 1871, 16 Stat. 433__ 40

Amendatory Act of May 11, 1866, 14 Stat. 46______ 32

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27:

Section 1--------------------------------------------- 9, 16, 19, 43

Section 2--------------------------------------------- 9, 36, 42, 43

Section 3--------------------------------------------- 9,14,32,53

Sections 4-10_________________________ 39

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 266:

Title I I_______________________________ 25

Section 901___________________________ 24

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140:

Section 6_____________________________ 9

Section 16____________________________ 53

Section 17____________________________ 9,42

Section 18_________________________________ 42, 54

Habeas Corpus Act of February 5, 1867, 14 Stat. 386_ _ 11

Judicial code of 1911, § 31, 36 Stat. 1096______ 14

I l l

IV

Statutes and Rules—Continued Page.

Judiciary Act of 1789, § 12, 1 Stat. 79____________ 13

Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat. 13:

Section 1_____________________________ 9, 11, 43, 54

Section 2 __________________________________ 9, 54

Revised Statutes of 1874:

Section 641__________________________ 14,32,47,55

Section 643________________________________ 30, 47

Voting Rights Act of 1965:

Section 11(b)_______________________________ 26

18U.S.C. 241__________________________________ 9,26

18 U.S.C. 242_____________________________ 9, 42, 43, 56

28 U.S.C.:

§ 74______________________________________ 14

§ 1442(a)(1)__________________________ 47

§ 1443_________________________________ in passim

§ 1446(e)__________________________________ 35

§ 1446(f)__________________________________ 35

§ 1447(c)__________________________________ 32

§ 1447(d)__________________________________ 3,24

§ 1448(c)__________________________________ 34

§ 2241(c)(3)_______________________________ 11

§ 2251_____________________________________ 11

§ 2283_____________________________________ 11

42 U.S.C.:

§ 1971_____________________________________ 4, 55

§1971 (a)__________________________________ 19

§1971(b)__________________________________ 26

§ 1981__________________________________ 19, 53, 55

§ 1982__________________________________ 19, 53, 55

§ 1983_____________________________ 9, 11,42,43,56

§ 1985___________________________________ 9, 19, 55

§ 2000(a)_______________________________ 19,26,55

§ 2000(e)__________________________________ 19,55

State Laws:

Mississippi Code:

Section 2296.5______________________________ 4

V

Miscellaneous:

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally

Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal Removal and Habeas

Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State Court Trial, 113 Page.

Pa. L. Rev. 793____________________________ 9, 11, 38

Cong'. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess:

p. 503_____________________________________ 8

pp. 602-603________________________________ 10

pp. 1124-1125______________________________ 9

p. 1367____________________________________ 17

p. 1758____________________________________ 43

p. 2063------------------------------------------------------ 10

Cong. Globe. 41st Cong., 2d Sess., p. 3663_________ 42, 43

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess., App. 68_________ 43

110 Cong. Rec. 2770____________________________ 24

110 Cong. Rec. 6955____________________________ 24

1 Farrand, Records oj the Federal Convention of 1787

(1911), p. 124______________________________ „ 47

Jtt to Jsujjrtntt (ffottrt of to United states

October T erm , 1965

No. 471

T h e City of Greenwood, M ississippi, petitioner

v.

W illie P eacock, et al.

No. 649

W illie P eacock, et al., petitioners

v.

T h e City of Greenwood, M ississippi

ON C E R T IO R A R I TO TH E U N ITED S T A T E S COURT OF A P P E A L S

F O R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

O PIN IO N S BELOW

The opinions of the court of appeals (R. 21-32,

96) are reported at 347 F. 2d 679 and 347 F. 2d 986.

The opinions of the district court in these cases

(R. 8-17, 67-71, 89-91, 92-94, 94-96) are not officially

reported, but its opinion in a related case which was

adopted by reference (R. 72-87) is reported at 237

F. Supp. 213.

(i)

2

JU R IS D IC T IO N

The judgment of the court of appeals in the Pea

cock case (R. 33) was entered on June 22, 1965, and

the judgment in the Weathers case (R. 96) on July

20, 1965. Cross-petitions for writs of certiorari were

granted on January 17, 1966, 382 U.S. 971 (R. 97-

98). The cases were consolidated and set for oral

argument immediately following Georgia v. Thomas

Rachel, et a l No. 147, this Term, certiorari granted,

382 U.S. 808 (R. 98). The jurisdiction of this Court

rests on 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

ST A T U T E IN V O LV ED

Section 1443 of Title 28, United States Code, pro

vides :

Any of the following civil actions or crim

inal prosecutions, commenced in a State court

may be removed by the defendant to the dis

trict court of the United States for the district

and division embracing the place wherein it is

pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or

cannot enforce in the courts of such State a

right under any law providing for the equal

civil rights of citizens of the United States, or

of all persons within the jurisdiction thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority

derived from any law providing for equal

rights, or for refusing to do any act on the

ground that it would be inconsistent with such

law.

QUESTION S P R E SE N T E D

1. Whether Section 1443(1) of the Judicial Code

authorizes the removal to federal court of a State

criminal prosecution founded on a State statute

3

which, although valid and non-discriminatory on its

face, is applied so as to deny the accused a right

under a law providing for equal civil rights.

2. Whether Section 1443(2) of the Judicial Code

extends the remedy of removal to private persons

with respect to a criminal prosecution arising out

of their exercise of equal civil rights, and the asso

ciated rights of advocacy and protest.

IN T E R E S T OF T H E U N IT E D STATES

Together with Georgia v. Rachel, Ho. 147, this Term,

these cases are the first under the civil rights removal

statute to reach this Court since 1906. They are here

by virtue of the provision of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 which, for the first time in three-quarters of a

century, permits appeals from orders remanding cases

removed pursuant to Section 1443. See 28 U.S.C.

1447(d), as amended. The questions presented are of

obvious importance to those who are engaged in ef

forts to obtain the promise of equality for Negroes.

Their resolution, moreover, may significantly affect

the business of the federal courts. Accordingly, it

seems appropriate that the United States express its

views on the far-reaching issues involved.

ST A TEM EN T

On April 3, 1964, the thirteen State court defend

ants in the Peacock case filed petitions for removal

(R. 3) in which they alleged that each of them was a

civil rights worker affiliated with the Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee engaged in a voter

registration drive in Leflore County, Mississippi

aimed at encouraging the registration of Negroes.

212—260—66--- 2

4

They recited that, on March 31, 1964, they were ar

rested in Greenwood and subsequently charged with

obstructing public streets in violation of Section

2296.5 of the Mississippi Code. They alleged that the

State statute invoked against them was unconstitu

tionally vague, that it was arbitrarily applied and

used, and that its enforcement against them was “ a

part and parcel of the unconstitutional and strict pol

icy of racial segregation of the State of Mississippi

and the City of Greenwood” ( R. 4), and on that basis

asserted that they could not enforce in the courts of

Mississippi their rights of free speech, free assembly,,

and the equal protection of the laws under the First

and Fourteenth Amendments. They further generally

alleged in the language of § 1443(1) that they were

being “denied [and]/or cannot enforce in the courts

of such State” their rights under laws providing for

the equal rights of citizens, and in the language of

§ 1443(2) that because of their arrests they could not

“act under * * * authority” of the First and Four

teenth Amendments and 42 U.S.C. § 1971 (dealing

with the right to vote free from racial discrimina

tion). The district court remanded the cases to the

State court, holding that § 1443 “authorizes removal

of a criminal case from a state court to a federal

court only when the Constitution or laws of the state

deny or prevent the enforcement of equal rights * *

(R. 13). The Court of Appeals stayed the remand

orders pending appeal (R. 19).

The fifteen State court defendants whose removals

were consolidated in the Weathers case filed removal

5

petitions between July 23, 1964, and August 21, 1964

(R. 36-63). Their petitions were identical except for

the specification of the State charges against them and

brief descriptions of their conduct at the time of their

arrests. The petitioners alleged that they were civil

rights workers affiliated with the Council of Federated

Organizations (COFO), the activities of which were

“designed to achieve the full and complete integra

tion of Negro citizens into the political and economic

life of the State of Mississippi” (R. 37). They re

moved 21 separate charges against them. Three of

the petitioners were arrested on July 16, 1964, while,

according to their allegations, they were “peacefully

picketing” at the Leflore County Courthouse in

Greenwood (R. 38). They were charged with assault

and battery (R. 36) and, in addition, petitioner

Weathers was charged with interfering with an officer

(R. 47). On July 31, 1964, two others were charged

with operating motor vehicles with improper license

tags while driving in Greenwood (R. 52, 61), a third

who was riding as a passenger was charged with

interfering with a police officer (R. 51), and a fourth,

a member of a group “walking along the roadside

singing songs” was charged with contributing to the

delinquency of a minor and parading without a per

mit after obeying an officer’s order to disperse (R.

53-54). On August 1 one of the petitioners was

arrested and charged with assault while “engaged

* * * in * * * voter registration activity, when he

was accosted and assaulted in said exercise” (R. 59) ;

another was charged with disturbing the peace while

6

engaged in COFO’s “ Freedom Registration” program

(R. 55) ; and two others were charged with disturbing

the peace while protesting police brutality “by word

of mouth, pamphlets, and photographs” on a public

street (R. 50). Others were charged on various dates

with the use of profanity while on a public street

(R. 57); disturbing the peace while participating

in an economic boycott (R. 58) and assembling on a

street (R. 62) ; inciting to riot while promoting an

economic boycott of a grocery store the owner of

which, a part-time policeman, had allegedly engaged

in police brutality (R. 60) ; and assault and battery

while at a police station making an inquiry during

which “ assault and battery was accomplished with

the intent to intimidate and harass petitioner”

(R. 63).

The petitioners in Weathers alleged that they had

engaged in no conduct prohibited by any valid law

or ordinance of the State or city (R. 38) and that

their arrests and prosecutions were for the sole pur

pose of “harassing Petitioners and of punishing them

for and deterring them from the exercise of their

constitutionally protected right to protest the condi

tions of racial discrimination and segregation” in

Mississippi (R. 38). Their petitions alleged denials

of, or the inability to enforce in State court, equal

rights protected by § 1443(1) because of practices of

racial segregation and discrimination throughout the

State of Mississippi in state courts, in the electoral

process, and in the selection of jurors (R. 40-41).

They further asserted a right to remove under

7

§ 1443(2) because the conduct for which they were

arrested was “engaged in by them under color of

authority derived from the Federal Constitution and

laws providing for equal rights of American citizens”

(R. 41) in that their acts were protected by the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

the free speech and assembly guarantees of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments. They further alleged

that the statutes under which they were charged are

unconstitutionally vague or unconstitutional if con

strued to apply to their conduct, that the prosecutions

had no basis in fact and were therefore groundless,

and that there is no theory under which their conduct

could lawfully be brought within the ambit of these

statutes (R. 41-42). The district court on December

30, 1964, remanded the Weathers cases to the State

court for the reasons stated in the Peacock opinion

and in the district court’s opinion in City of Clarks-

dale v. Gertge (R. 67-71, 89-91, 92-94, 94-96, see

R. 72-87). The district court granted a stay of the

remands pending appeal (R. 71, 91, 94).

The court of appeals, on June 22, 1965, reversed the

order remanding the Peacock cases (R. 33) for rea

sons given in an extensive opinion (R. 21-32). On

July 20, 1965, the court likewise reversed the remand

orders in the Weathers cases by a per curiam decision

invoking its opinion in Peacock (R. 96). The court

in its Peacock opinion read the removal petition there

to allege that a State statute “is being invoked dis-

criminatorily to harass and impede appellants in their

efforts to assist Negroes in registering to vote” in

8

violation of the equal protection clause (R. 24), and,

on that basis, concluded that a ground for removal

under § 1443(1) had been stated (R. 24-25). And

the court accordingly remanded the cases to the dis

trict court with a direction that it permit the peti

tion to prove that allegation, in which event the prose

cutions should be dismissed (R. 32, 96).

The court went on, however, to reject petitioners’

claim of a right to remove under § 1443(2). That

conclusion was compelled by the court’s view that

private individuals, as distinguished from public

officials and persons acting under their direction, can

not be said to be acting “ under color of authority”

of civil rights laws within the meaning of § 1443(2)

(R. 29-32).

A R G U M E N T

Introduction and Summary

A century ago the Regro won his freedom and was

solemnly declared a citizen and an equal before the

law. Rut, from the first, it was realized that no mere

declaration—even if enshrined in the Constitution it

self—would overcome resistance in the defeated

States.1 And so federal statutes were promptly en

1 See, e.g., the statement of Senator Howard in January 1866

(Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 503) :

I t was easy to foresee, and of course we foresaw, that in

case this scheme of emancipation was carried out in the

rebel States it would encounter the most vehement resistance

on the part of old slaveholders. I t was easy to look

far enough into the future to perceive that it would be a

very unwelcome measure to them, and that they would

resort to every means in their power to prevent what they

called the loss of their property under this amendment.

We could foresee easily enough that they would use, if they

9

acted to vindicate the rights of the new freedmen.

The majestic generalities of the new constitutional

guaranties were given concrete content by positive

legislation defining specific rights; 2 criminal laws were

passed to punish disobedience, by officials3 and private

conspiracies 4 alike; civil remedies were provided for

those who still would be denied; 5 and, in each in

stance, jurisdiction to implement the new laws was

given to the federal courts.6 There remained one

further danger to guard against, however: the pos

sibility that the Negro or his protector would be the

victim of a hostile judicial system when he was

should be permitted to do so by the General Government,

all the powers of the State governments in restraining and

circumscribing the rights and privileges which are plainly

given by it to the emancipated negro.

See, also, the remarks of Representative Cook, id. at 1124—1125.

The materials are collected in the exhaustive article of Professor

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally Guar

anteed Civil Rights: Federal Removal and Habeas Corpus Juris

diction to Abort State Court Trial, 113 Pa. L. Rev. 793, at 808-

828.

2 E.g., § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1886, 14 Stat. 27, and

§ 17 of the Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 144, now

42 U.S.C. 1981, 1982. See, also, Brief for the Appellants in

Katzenbach v. Morgan, No. 847, this Term, pp. 31-41.

3 E.g., § 2 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27, and

§ 17 of the Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 144, now

18 U.S.C. 242. See, also, Brief for the United States in United

States v. Price, Nos. 59 and 60, this Term.

i E.g., §6 of the Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat.

141, now 18 U.S.C. 241. See, also, Brief for the United States

in United States v. Guest, No. 65, this Term.

5 E.g., §§ 1 and 2 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, 17

Stat. 13, now 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1985.

6 E.g., § 3 of the Civil Eights Act of 1868, 14 Stat, 27. See,

also, Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 183; McNeese v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 688.

1 0

brought before the State court as a defendant on a

local charge.7

Two potential problems lurked in that situation.

The first was that the suit or prosecution itself might

be instituted and carried through in total disregard

of the federal law which authorized the Negro to

engage in the activity for which he was now sued and

which directed federal officers to protect him in the

enjoyment of his new equality. The other danger—

perhaps more common—was that, even if the suit was

justified, the defendant—because of his race or be

cause of his cause—might not obtain a fair trial in the

local court. There were many variants of the second

situation. In the case of the Negro defendant, it

might be the consequence of continuing local proce

dural rules which, in defiance of federal law, denied

his race representation on the jury, or the right to

testify, or some other courtroom prerogative enjoyed

by whites. For both the Negro and his protector, the

prejudice might come, less obviously, but as effectively,

from local hostility to the cause of civil rights which

could infect the whole judicial process in a community.

7 See, e.g., the remarks of Senator Lane (Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess., p. 602) :

But why do we legislate upon this subject now? Simply

because we fear and have reason to fear that the emanci

pated slaves would not have their rights in the courts of the

slave States. The State courts already have jurisdiction of

every single question that we propose to give to the courts

of the United States. Why then the necessity of passing

the law? Simply because we fear the execution of these

laws if left to the State courts. That is the necessity for

this provision.

See, also, the colloquy between Senators Hendricks, Stewart,

Doolittle, and Clark, at id. 2063.

11

'These are the cases that concern us here. The ques

tion is whether the architects of the first civil rights

revolution left those problems without adequate

solution.

I t would be strange indeed if the great egalitarians

•of the Reconstruction decade overlooked so obvious a

danger or failed in the attempt to devise an effective

remedy. The men of the early post-War Congresses

were realists, neither callous nor inept. We think it

plain they saw the problem and solved it for each of

the cases we have suggested by declaring a right of

removal to a federal court. This is not to say that,

for those cases in which a criminal prosecution was

wholly unwarranted, more radical remedies were not

also provided—by way of habeas corpus before tr ia l8 or

injunctive relief.9 But, for all other situations at least,

the already familiar device of removal10 was the

obvious solution, because it both assured sufficient

protection to the exercise of civil rights and involved

the least impingement on State prerogatives. The

8 § 1 of the Habeas Corpus Act of February 5, 1867, 14 Stat.

386, now 28 U.S.C. 2241(c)(3), 2251, discussed at some length

in Amsterdam, op. eit. supra, at 819-825, 882-908. See Fay v.

Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 415-419.

0 See § 1 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat. 13,

now 42 U.S.C. 1983, which (insofar as it authorizes injunc

tive relief) may well have been intended as an exception to the

rule, now embodied in 28 U.S.C. 2283, prohibiting a stay of

State court proceedings. The question has been left open in

this Court. See Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 484, n. 2;

■Cameron v. Johnson, 381 U.S. 741.

10 The earlier removal legislation is canvassed in this Court’s

opinions in The Mayor v. Cooper, 6 Wall. 247, and Tennessee v.

Davis, 100 U.S. 257.

2 1 2 -2 6 0 — 66------- 3

12

very appropriateness of the remedy strongly suggests,

it must have been intended to operate in the circum

stances we are discussing.

What were the virtues of removal in this context?

First, unlike habeas corpus or injunctive relief, it

would not finally arrest a suit or prosecution that

ought to be tried; in all instances in which the insti

tution of the proceeding was not wholly unwarranted,

the removal case could go forward in a changed

forum, free of prejudice. Removal would not im

munize the new freedman and his protectors from the

rightful grievances of local suitors or place them be

yond the reach of the State criminal law. Moreover,

because the transfer would often be automatic, there

would be little occasion for the federal judge to try

his State court brother—an unseemly spectacle at

best and one frought with serious dangers of enervat

ing Federal-State relations. In some cases removal

would depend on the existence of hostile State legis

lation, avoiding any inquiry into the actual practices of

the particular local judge. More often, the transfer

would be effected simply because the alleged wrong

had been committed in the course of civil rights

activity, without stopping to finally determine, at this

point, whether the defendant had indeed overreached

the bounds of his federal privilege, much less whether,

in the particular instance, the context of the case

would really prejudice the trial. And, finally, be

cause removal—unlike post-conviction habeas corpus

or appellate review in this Court—is a pre-trial

remedy, it would involve none of the friction inherent

13

in the procedures which permit federal courts to re

examine the decisions of State tribunals.

To be sure, the rule permitting removal in such

circumstances would itself embody an unflattering

implication against the State judiciary as a whole.

But that impersonal distrust of local courts, made

anonymously by the law as a matter of general regula

tion, could not carry the same sting. I t would be

merely a limited exercise of federal jurisdiction which

the Constitution itself had condoned from the begin

ning ; 11 and in time, it might come to be accepted as no

more offensive than the diversity removal rule which

had been in force since the first Judiciary Act of

1789.12 On the other hand, removal was a swift and

sure remedy against local prejudice—-necessarily, a

far more effective shield against discriminatory treat

ment of the freedom attempting to assert their newly

won rights than the ultimate revisionary power of

this Court over the judgments of State tribunals.13

I t is against this background that we must ex

amine the contemporary legislation which provided

for removal of “civil rights” cases. The problems of

the time—still too familiar—and the knowledge that

the Congress of that day was dedicated to resolving

them, must inform the exegesis. To borrow the lan

guage of this Court in construing the Fourteenth

Amendment itself—framed by the same men who

wrote the statutes wre examine—“ [t]he true spirit

11 See, infra, pp. 47-48.

12 Act of September 24, 1789, § 12, 1 Stat. 73, 79.

13 Cf. Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 416. See also, England v.

Medical Examiners, 375 U.S. 411, 416-417.

14

and meaning of the [provisions] cannot be under

stood without keeping in view the history of the

times when they were adopted, and the general ob

jects they sought to accomplish,” in light of which

they should be “construed liberally.” Strauder v.

West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 306, 307. Whatever

hesitation there may be to return to the spirit of

1866—as the normal rules of legislative construction

in any event suggest—must yield to the unhappy

truth that a century of cautious waiting has not re

moved the problem. Accordingly, we turn to the

early provisions which, still today, supply a needed

remedy.

The law of removal in this area derives from Sec

tion 3 of the very first Civil Rights Act, the Act of

April 9, 1866 (14 Stat. 27). Despite several changes

in terminology,14 everyone agrees that the substance

of the matter is circumscribed by the terms of this

old statute and we are content to rest our argument-

on that text—reserving only the question of the rights

protected which later revisions somewhat expanded.15

In pertinent part, the removal section of the 1866

Act read as follows:

* * * the district courts of the United

States, within their respective districts, shall

have, exclusively of the courts of the several

States, cognizance of all crimes and offences

committed against the provisions of this act,

and also, concurrently with the circuit courts

of the United States, of all causes, civil and

14 See E.S. §641; Judicial Code of 1911, §31, 36 Stat.

1096; 28 U.S.C. 74(1940); 28 U.S.C. 1443 (1948).

15See discussion, infra , pp. 53-56.

15

criminal, affecting persons who are denied or

cannot enforce in the courts or judicial tri

bunals of the State or locality where they may

be any of the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act; and if any suit or

prosecution, civil or criminal, has been or shall

be commenced in any State court, against any

such person, for any cause whatsoever, or

against any officer, civil or military, or other

persons, for any arrest or imprisonment, tres

passes, or wrongs done or committed by virtue

or under color of authority derived from this

act or the act establishing a Bureau for the

relief of Freedmen and Refugees, and all acts,

amendatory thereof, or for refusing to do any

act upon the ground that it would be inconsist

ent with this act, such defendant shall have

the right to remove such cause for trial to the

proper district or circuit court in the manner

prescribed by the “ Act relating to habeas

corpus and regulating judicial proceedings in

certain cases,” approved March three, eighteen

hundred and sixtv-three, and all acts amenda

tory thereof. * * '* 16

In terms, this provision grants a right of transfer

to the federal court at the instance of a defendant

16 Inadvertently, in quoting tliis section, the opinion below

(as reprinted in the City of Greenwood’s petition for certiorari,

p. 76, and the record here, R. 30, n. 7) omits from the second por

tion of the section the words “against any such person, for any

cause whatsoever, or”—which, by reference back to the preceding

clause, states the first ground of removal, now 28 U.S.C.

1443(1). The same error is repeated in the Brief for Re

spondents in Georgia v. Rachel, No. 147, this Term, p. 55.

The provision is correctly reproduced in the Petition for

Certiorari (App., p. 36) and the Brief for Petitioner in the

same case (pp. 59-60).

16

called before a State court to answer a civil or crim

inal complaint in three distinct situations:

(1) When the defendant, regardless of the nature

of the case (“for any cause whatsoever”), “ [is]

denied or cannot enforce in the courts or judicial tri

bunals of the State or locality * * * any of the rights

secured to [him] by the first section of [the Civil

Rights Act of 1866]” (all, in effect, aspects of the

right to equal treatment by the law, in both substantive

and procedural matters) ;11 * * * * * 17

(2) When the defendant, whether he be “any of

ficer, civil or military, or other person/’ is held to

answer on account of “any arrest or imprisonment,

trespasses or wrongs done or committed by virtue or

under color of authority of [the Civil Rights Act of

1866 or the Freedmen’s Bureau legislation]” 18; and,

finally,

(3) When the defendant (presumably a State offi

cial)19 is sued or prosecuted “for refusing to do any

act upon the ground that it would be inconsistent

with [the Civil Rights Act of 1866]”.

11 Section 1 of the Act declared Negroes citizens and con

ferred upon them “the same right * * * to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, pur

chase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed, by white

citizens, and [to] be subject to like punishment, pains, and

penalties, and to none other * * *.”

18 Today, and ever since 1874, “any law providing for equal

rights” replaces the bracketed words. See, infra , pp. 54-55.

19 A restrictive reading of the “refusal” clause is suggested

by its legislative history. The provision came in by amend

ment to the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and was explained by its

17

We are not here concerned with the last situation—

involving as it does only the plight of the local official

called to answer in his own court for refusing to obey

the directives of local law or local superiors when

they conflict writh the supervening federal statute.

I t is worth noting, however, because it indicates that

the framers of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 over

looked nothing. Our immediate focus is on the other

two occasions for removal. There, if at all, we must

find a remedy for the danger that a hostile local court

would disregard the new privileges granted the Negro.

At the outset, it seems clear these provisions are

broad enough to encompass all our cases—as one would

expect in light of what has already been said con-

'cerning the problems of the time and the determina

tion of the contemporary Congress to resolve them.

This is not to say that there are not close questions of

statutory construction involved. On the contrary, we

freely concede that our reading of the text is, in some

-instances, less than assured. Permissible alternatives

are perhaps equally plausible. We must, however,

emphasize our belief that no construction would be

faithful to the intent of the Thirty-Ninth Congress—

or to the needs of the present—that withheld removal

relief in any of the circumstances we have thus far

sponsor in these words (Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.,

p. 1367) :

I will state that this amendment is intended to enable

State officers, who shall refuse to enforce State laws dis

criminating in reference to these rights on account of race

or color, to remove their cases to the United States courts

when prosecuted for refusing to enforce those laws. * * *

18

mentioned. With that important caveat, we return to'

the text and outline our analysis.

1. We first examine the provision (now 28 IT.S.C.

1443(1)) which permits a State court defendant to

remove the case against him if he “ [is] denied or

cannot enforce in the courts * * * of the State”"

one of the “egalitarian rights” protected by the re

moval statute (infra, pp. 21-36). In our view, the

operative words govern two different problems: (1)

the apprehension of the defendant that—because of

his race and regardless of the context of the case -

lie will not be able to “ enforce” his procedural rights

at his forthcoming trial in the local court; (2) the

situation of a State court defendant who has already

been “denied” protected right by being subjected to

trial on a discriminatory or unfounded prosecution.

We have no occasion here to urge reconsideration,,

for the first category of cases, of the restrictive

rule of Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, and the subse

quent decisions of this Court that nothing short of a

legislative directive will justify the delicate predic

tion that a State judge will violate his constitutional

oath to render equal justice to all. But when the

claim is that the initiation of a court proceeding of

itself constitutes a present) denial of protected r ights,

we submit that the removal statute requires the fed

eral court to take over the case and to dismiss it if,

after full inquiry, it is satisfied that the prosecution

is discriminatory or wholly unwarranted.

2. Turning next (infra, pp. 36-53) to the second

provision of the “ civil rights” removal statute (now

19

'28 U.S.C. 1443(2)), we attempt to show that it is not

confined to federal officers acting under color of their

office, but extends also to private persons who assert

that the State proceedings against them arise out of

their exemse~of protected rights) In our view, an in-

dividualTriay be 'said to be" acting' “under color of au

thority”. _of a “ law providing for equal rights” when

he believes his conduct is privileged, and immunized

against improper official interference, by overriding

federal law. We suggest that the consequences of

such a rule are not offensive to proper notions of

federalism, emphasizing that removal in such cases

does not abate the prosecution, but merely transfers

the trial to another forum.

3. We consider, in a third section of our brief

(infra, pp. 53-56), the scope of the rights protected

by the removal statute. Although the original statute,

so far as is relevant here, referred only to the rights

declared by Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866

(now 42 U.S.C. 1981-1982), we think it proper, in

this particular, to focus on the language of the Re

vised Statutes of 1874, carried forward in the present

Judicial Code, which speaks of “ right[s] secured”

by, or acts done “under color of authority” of, “ any

law providing for equal rights.” And we follow the

uniform judicial construction of this phrase as in

tending an open-ended category. In our view, this

leads to the conclusion that the rights protected by

the removal statute includes those declared or secured

by Sections 1971(a), 1981, 1982, 1985(3), 2000a and

_2000e of Title 42 of the United States Code, at least

2 1 2 -2 6 0 — 66- 4

20

insofar as those provisions forbid inequality of treat

ment based directly or indirectly on race, as well as

the corollary privilege to advocate the exercise of

those rights and protest their denial. While we do

not foreclose a broader reading, we suggest that, for

present purposes, it is unnecessary to decide the diffi

cult question whether other rights guaranteed by the

Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment are also included within the

scope of the removal statute.

4. Finally (infra, pp. 57-58), we address ourselves to

the proper disposition of the cases before the Court.

Because the cases are here on preliminary rulings,

before any development of the facts which control the

question of removal, there is little occasion to do more

than suggest the guiding principles. I f our submis

sion with respect to the appropriate boundaries of the

removal statute is correct, however, it is clear the cases

must be remanded to the district court. In our view,

an arguable basis for removal under both paragraphs

of Section 1443 has been stated by each of the removal

petitions. Accordingly, we suggest affirmance of the

order below remanding the cases for a full hearing

under Section 1443(1). But we submit that the

ruling of the court of appeals denying removal under

Section 1443(2) is erroneous, that it should be vacated,

and that the district court, on remand, should be in

structed to consider removal on this ground also, if

petitioners fail to show that they are entitled to out

right dismissal of the pending prosecutions.

21

A. THE “ DENIAL” PROVISION OF THE REMOVAL STATUTE

(28 U.S.C. 1443(1) ) PERMITS PRE-TRIAL RELIEF AGAINST

DISCRIMINATORY AND REPRESSIVE PROSECUTIONS

The first relevant provision of the statute (now 28

U.S.C. 1443(1)) turns removal on denial or inability

to enforce one of the enumerated rights in the State

courts. Without rejecting the forceful arguments to

the contrary (see, e.g., Sobeloff, J., dissenting in

Baines v. Danville, No. 9080, C.A. 4, decided Janu

ary 21, 1966, petition for certiorari pending, No. 959,

this Term), we rest our own submission on the assump- j

tion that the words “denied” and “cannot enforce” both j

refer to action or anticipated action “in the courts or ju- j

dicial tribunals of the State.” That was the construe-

tion given the provision in Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S.

313, 321, and, as a matter of textual analysis, it is diffi-

cult to quarrel with that reading. We are content to J

read the terms “denied” and “cannot enforce” as simply J

referring to different stages of the proceeding—the

present and the future.20 But that is, in itself, an

important distinction. Indeed, it is obvious that very

different considerations may govern according as the

claim for removal rests on an accomplished fact—which

can be closely examined—or, rather, on a mere predic-

20 I t may well be that, originally, when removal could be

effected at any time, before or after trial, the term “denied”

applied to denials both before and during trial—whereas, since

the revision of 1871 confined the remedy to pre-trial, the

defendant can only claim a denial before the trial begins. But,

then as now, the tense of the verlCjFis deniecT'Ualways indi

cated a present denial, not a prediction. ‘W yW ntrast, “cannot

enforce,” in all versions of the statute suggests a future denial.

22

tion of future denial, where some danger of erroneous

speculation is unavoidable.

i . “ cannot enforce”

We begin with the cases in which the allegation is

that the defendant will not be able to enforce, at trial,

a right within the protection of the removal statute.

| All the decisions in this Court—from Strauder v.

1 West Virginia and Virginia v. Rives, supra, through

j Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U.S. 1—are of that charac-

I ter, each involving a claim by the defendant that he

| would not be able to vindicate his right to a non-

discriminatory jury. Indeed, the main thrust of the

“ cannot enforce” clause is to provide a remedy for

; the States court’s anticipated refusal to recognize in

the Negro the same procedural rights at his trial as

are enjoyed by white citizens—a problem of more

obvious acuteness in the day of the Black Codes.

There are, however, other possible applications of

the clause. To borrow an illustration from the con

text of 1866, we may suppose a State statute which,

in defiance of the Civil Rights Act of that year, for

bade the sale of land to a Negro and a prosecution of

the seller for disregarding that law. I f we assume

that the State judge will feel bound to follow the law

of his State,21 this is plainly a case in which the de

fendant “cannot enforce” his federal right in the lo

cal tribunal and, hence, is entitled to removal. And

the same reasoning, of course, applies to the perhaps

21 We assume the local statute neither predated the federal

enactment (see Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370), nor had been

invalidated as unconstitutional (see Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S.

110).

23

more compelling modern case of the Negro who is

charged under an unconstitutional local segregation

ordinance for peaceably seeking service at a lunch

counter covered by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The rule for these cases is a strict one under the

old decisions of this Court. The doctrine of Virginia

v. Fives—at least as construed in the later decisions—

is that nothing short of a present (albeit unconstitu

tional) legislative directive can support the predic

tion that the State judge will refuse to accord the

same procedural rights to the defendant as others

enjoy or to recognize his substantive defense under a

federal statute “providing for equal rights.” There

are strong arguments for relaxing that rule, although

we concede the force of considerations which suggest

limiting the occasions in which a federal judge is

called upon to speculate that his Brother of the State

court will be unfaithful to his constitutional oath.

However, since the cases before the Court do not nec

essarily present the question, we abstain from any dis

cussion of the proper scope of the “cannot enforce”

clause.

Even if the rule of Virginia v. Rives were adhered

to, however, it woul(^follow that the whole of what

is now subsection (1) of Section 1443 is obsolete.

There are other applications of that provision—un

der the “denial” clause—which have special impor

tance in the contemporary context.

2 . “IS DENIED”

The more substantial question—and the one in

volved in the cases before the Court—is whether the

24

‘4denial” clause offers any relief when the State law

on which a criminal charge is predicated is not void

on its face, but is alleged to be unconstitutional as ap

plied to the defendant in the circumstances. This

Court has never had occasion to reach that issue.

And it was in part in order to permit its authoritative

resolution that Congress recently amended the civil

rights removal statute by providing for appellate re

view of remand orders. See § 901 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (78 Stat. 266), now the proviso to 28

U.S.C. 1447(d), as amended. Senator Dodd, the

floor manager with respect to the appeal provision,

expressed the congressional attitude (110 Cong. Rec.

6955) :

Needless to say, by far the most serious de

nials of equal rights occur as a result not of

statutes which deny equal rights upon their

face, but as a result of unconstitutional and

invidiously discriminatory administration of

such statutes.

# # # # #

In particular, I think cases to be tried in

State courts in communities where there is a

pervasive hostility to civil rights, and cases in

volving efforts to use the court process as a

means of intimidation, ought to be removable

under this section.22

We agree. In our view, however, that result is

not inconsistent with this Court’s early decisions,

which we read as construing the statute only as it

22 See the similar speech by Congressman Kastenmeier, 110

■Cong. Rec. 2770, and the remarks of then Senator Humphrey

on this point, id. at 6551.

25

applies to claims alleging inability to enforce a right

in the future, at trial. Our submission is that the

circumstances described in the Senate debate involve

a present violation of protected rights, removable

under the “ denial” clause of what is now Section

1443(1).

There are several variants of the situation, or, at

least, the focus can be placed on differing aspects

of the problem. Thus, one not unfamiliar case is

that of the discriminatory prosecution, in which

Negroes are charged under a State law or local

ordinance which is valid on its face and permissibly

applicable to the conduct in suit but which, in prac

tice, is not applied in similar circumstances to white

persons. See Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 555-

558; Brown v. Louisiana, No. 41, this Term, decided

February 23, 1966 (concurring opinion of Mr. Justice

White). On those facts—without noticing whether

the defendant was at the time engaged in exercising

a substantive right protected by the removal statute—

it is clear that there has been a denial of the right

to “be subjected” to “none other” but those “ punish

ments, pains and penalties” imposed on “white citi

zens.” 23 Another example is the prosecution under

an otherwise valid local law (i . e a trespass statute)

for conduct which is privileged under federal law

{i.e., peaceably seeking service at an establishment

covered by Title IT of the Civil Rights Act of 1964).

23 We need hardly elaborate the proposition that, in some

circumstances at least, a discriminatory prosecution constitutes

unequal “punishment” within the meaning of the Civil Eights

Act of 1866. See Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (C.A. 5).

26

Cf. Georgia v. Rachel-, No. 147, this Term. Here,,

again, there is a denial of a protected federal right—

whatever motive inspired the institution of the pro

ceeding. And, finally, there is the case—related to

each of the others, but distinguishable—in which a

wholly unwarranted charge is brought to intimidate

Negroes out of asserting rights within the removal

statute. Ignoring the denial of due process inherent

in the seizure and detention of the accused without

cause, such a prosecution obviously impinges on the

protected substantive right involved by violating the

correlative right to be exempt from official threats

designed to deter its exercise. See, e.g., 42 TLS.C.

1971(b), 2000a-2(b), (c), and § 11(b) of the Voting

' Bights Act of 1965. Of. 18 TJ.S.C. 241.

In each of these situations, it is plain that a right

protected by the removal statute has been “denied”

in a very real sense. Beyond the immediate injury

inherent in being subjected to unfounded charges, it

is sufficiently obvious that, in a “ closed society”

which sets the race apart, a discriminatory prosecu

tion against Negroes, whatever its purpose, and, a

fortiori, one that arises out of civil rights activity,

will tend to have a repressive effect on the exercise

of fundamental rights by the victim and others simi

larly situated—regardless of the prospects of ultimate

acquittal. Cf. Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479,

490, and cases there cited. The remaining question is

whether a deprivation of covered rights which results

from the institution of a formal prosecution is a

“denial” within the intendment of the removal pro

vision. We submit it is—although, as we elaborate in

27

a later section of our brief (pp. 36-52), we believe re

moval of all but the clearest of such cases is more

appropriately effected under the “color of authority”

provision, now 28 TT.S.C. 1443(2).

At the outset, we stress, once again, that the claim j

under the “ denial” clause is not that the defendant

will be unable to enforce a right at his State trial, not

yet commenced. The allegation here is, rather, that

the institution of the prosecution, which requires him

to stand trial, itself denies him a right protected by

the removal statute. These cases involve no assess

ment of probabilities, no predication as to what the f

State judge will do. Accordingly, the rule of Vir- j

ginia v. Rives and its progeny is inapplicable. Un- j

like the jury discrimination there involved, which was

harmless unless the court endorsed it by denying a

challenge (100 U.S. at 321-322), the present denial of

rights in our cases has already inflicted injury before

the trial concludes, indeed, before it begins. So, also, |

because the claim here is that the deprivation is an ac

complished fact, the violation is susceptible of proof

and does not depend on appraisal of the defendant’s,

mere “ apprehension” with respect to the forthcoming;

trial (id. at 320). And, finally, since the basis for

removal in the circumstances we are discussing is not

the anticipated unconstitutional action of the State

court during the trial, we are not confronted—as the

Court was in Rives—with the difficult and delicate

problem of determining, in advance, whether the par

ticular judge will respect his oath to uphold the

Constitution.

2 1 2 -2 6 0 — 66-------5

28

We conclude that the precedents in this Court do

not stand in the way of our reading of the “ denial”

clause. But, wholly apart from those decisions, there

remain three possible objections to our submission on

this point. The questions raised are: (a) whether

a deprivation of protected rights by the institution of

a prosecution is a denial “ in the courts or judicial

tribunals of the State;” (b) whether removal is an

appropriate remedy when the stated ground for the

transfer is not apprehension as to the action of the

State court but a present denial of protected rights

through an unwarranted or discriminatory prosecu

tion; and, finally, (c) whether a procedure which dis

poses of the case on the merits in determining re

movability is consistent with the general purpose of

removal to permit the trial to proceed in an impartial

forum. We consider each of these points in turn.

(a) I t has been suggested with much force that

the “ denial” clause of the removal statute is not

necessarily tied to the qualifying words “ in the

courts * * * of [the] State”—the point being illus

trated by punctuating the relevant provision (which,

in the successive re-enactments, has never been punc

tuated to resolve the inherent ambiguity) to say that

removal is available to “ persons who are denied [,]

or cannot enforce in the courts or judicial tribunals

of the State or locality where they may be [,] any

right * * *.” See the opinion of Sobeloff, J., dissent

ing, in Baines v. Danville, Ho. 9080, C.A. 4, decided

January 21, 1966. As already noted, however, we pre

fer to rest our argument on the assumption that the

29

denial, present or future, must occur “ in tlie

courts * * * of the State or locality. ’ ’

We submit that the^in^titnthm-ixL a formal prose-

cution meets that test. To be sure, it is normally

the prosecutor who decides to make the charge—al

though, on occasion, in the police courts and justice

of the peace courts typically involved in the cases

that concern us, the initial official action may be

that of the local, judge issuing a summons or arrest

warrant on the complaint of a peace officer or a

private citizen. But, at some stage before the com

mencement of the trial, a judicial officer or his dele

gate must intervene, whether to issue a warrant or

summons, to commit the prisoner, to receive and file

the complaint, or information, or indictment. Thus,

the judicial machinery is necessarily involved when

a formal prosecution is initiated. Doubtless, in most

cases, the judge himself will have played a role—

however small. That is not critical, however. The

statute does not require that the denial be effected

“by the judge’7; it is enough if it occurs “ in the

court.” While there may be violations of right in

the arrest, or at other preliminary stages, the rele

vant denial for purposes of the removal statute is

the initiation of an unwarranted judicial proceeding.

And that condition is necessarily satisfied before the

removal petition is filed since nothing less than a

formal “ suit or prosecution * * * commenced in a

State court” is removable under the terms of the

statute.

30

In sum, while the removal statute is always ulti

mately guarding against the improper action—or in

action—of the State judge, the immediate focus of the

“denial” clause is on the locale, not on the actor. The

deprivation of right here is the initiation of an un

justified court proceeding and it does not matter who

set the case in motion—the judge himself, his clerk, the

prosecutor or another officer of the court. Once the

illegal prosecution becomes a formal “case”, the denial

is complete and the proceeding is removable.

(&) One may well ask what purpose is served by

removal if rights have already been finally denied

and no action of the State court can remedy the

wrong. The answer is, of course, that removal is

authorized in these situations because, although an

irremediable injury has been inflicted, it may yet be

aggravated by compelling the defendant to suffer an

unwarranted trial, or simply by holding him under

improper charges, perhaps incarcerated, for an ex

tended period pending trial. The underlying fear is

that the State judge will not promptly dismiss the

prosecution as he should. That is a risk which the

law determines, as a matter of general policy, to

avoid, in light of the urgent need to arrest further

injury to one already deprived of important federal

rights. In this sense, the possibility of prejudice—

or unconcern—on the part of the local judge is, once

again, the ultimate rationale of the transfer to a fed

eral court. But that is not the technical ground for

removal with respect to a defendant who has already

31

suffered injury. He must show a present denial of

protected rights in that he is a victim of the unequal

enforcement of State law or of an otherwise unwar

ranted prosecution interfering with his exercise of

such rights. He need not also prove (or even allege)

that the injury will he compounded by the action of

the State court in failing to grant swift relief; the

law itself supplies that ingredient in these circum

stances.

(c) Successful invocation of the “ denial” clause

of the removal statute, as we construe it, inevitably

results in pre-trial dismissal of the case, rather than

trial in a new forum; in these cases, the decision deny

ing remand, which determines removability, at the

same time finally disposes of the case, sometimes on

the merits of the plea of privilege or justification.

There is some basis for the charge that such a pro

cedure resembles more injunctive relief against State

court proceedings than removal of a cause to the

federal forum. Indeed, the radical character of the

relief suggests that it be used sparingly. But it isr

nevertheless, a proper aspect of removal, fully war

ranted by the statute and a very appropriate remedy

in extreme circumstances.

There is, of course, no fixed rule that a removed

case must proceed to trial on the merits. Obviously,

if an absolute bar to the prosecution is claimed, it

must be heard and determined before trial—in what

ever court the proceeding is pending—and if the ob

jection is sustained no trial will ensue. In every

removable case, the defendant may transfer the hear-

32

mg of that threshold question to the federal court,24

where the proceeding will end if the plea is sustained.

I t is common experience to have the removed case

concluded at this stage. See, e.g., O’Cctmpo v. Har-

disty, 262 F. 2d 621 (C.A. 9) ; Be Busk v. Harvin, 212

F. 2d 143 (C.A. 5). Thus, here, the removal, although

it does not look to a trial in the federal court, serves

24 The present statute, applicable to all categories of removal,

expressly provides that a criminal prosecution may be removed

“at any time before final judgment.” 28 U.S.C. 1441(0). That

has been the rule for civil rights cases at least since the Revised

Statutes of 1874, which authorized removal “at any time before

the trial or final hearing of the cause.” R. S. 641. Indeed,

originally, removal of civil rights cases, if sought before judg

ment, could be effected only at the very inception of the court

proceeding, “at the time of [the defendant’s] entering his

appearance in [the State] court.” § 5 of the Act of March 3,

1863, 12 Stat. 755, 756, adopted by reference in § 3 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 (supra, p. 15) . The harshness of this rule

led to a provision in § 3 of the amendatory Act of May 11, 1866,

14 Stat. 46, permitting removal “after the appearance of the

defendant and the filing of his plea or other defence in [the

State] court, or at any term of said court subsequent to the

term when the appearance is entered, and before a jury is em-

pannelled to try the [case].”

Under present law, then, the defendant has an option. I f the

bar to the prosecution is not also the ground of removal, the

defendant may choose to await the State court’s ruling on his

preliminary plea and, after its denial, remove the case to the

federal court “before trial.” I t is not clear, however, whether

submission of the threshold issues would prevent their relitiga

tion, after removal, in the federal district court. In civil cases,

the State court rulings before removal have been treated as bind

ing on the ground that the federal trial court is not a reviewing

court. McDonnell v. Wasenmiller, 74 F. 2d 320 (C.A. 8); School

v. New York Life Ins. Go., 79 F. Supp. 463 (D. Tenn.); cf.

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 TJ.S. 415, 427-428; England v. Medi

cal Examiners, 375 U.S. 411, 417-419. On the other hand, it is

arguable that such rulings are merely tentative, subject to recon-

33

the important function of transferring to that forum

the equally critical adjudication of the plea in bar

to the prosecution, which is grounded on federal law.

To be sure, in other situations, the pretrial dismis

sal in the federal court normally occurs after final

removal of the cause, not as an incident of the deter

mination of removability on a motion to remand.

Here, too, the apparent incongruity might be avoided

by turning removability on the mere allegations of the

petition, or on a “prima facie” showing-—as is the

rule with respect to removal of prosecutions against

sideration until final judgment, and that the federal court suc

ceeds to the power of the State tribunal to reverse itself.

Because we deal here with criminal cases, it may also be per

missible to view the removal court as akin to a federal habeas

corpus court which may re-examine the facts underlying the

State court’s disposition of these legal issues. See England v.

Medical Examiners, supra, at 417, n. 8.

But, in any event, the defendant whose “motion to quash”

or “motion in bar” rests on the same ground as his petition for

removal has nothing to gain by submitting his claim initially

to the State court. Even if an adverse ruling there does not

preclude him from presenting the same contention to the federal

court (and thereby bar removal ah initio), he has not added to

his claim of “denial” by showing that the State court has pre

liminarily endorsed the violation of his protected rights. For,

whether or not the federal court may vacate the ruling after

removal, it is clear the State court might do so if the case

remained there. Indeed, the early decisions of this Court reject

a claim of denial of rights based on a refusal by the State trial

court to set aside an indictment returned by a discriminatorily

selected grand jury or to quash a similarly drawn petit jury

panel—final rulings, as a practical matter—on the ground that

an appellate court of the State might correct the error. See

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110; Sm ith v. Mississippi, 162 U.S.

592; Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U.S. 101: Williams v. Mississippi,

170 U.S. 213.

34

federal officers. See The Mayor v. Cooper, 6 Wall.

247, 253-254; Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U.S. 257, 262;

Maryland v. Soper (No. 1), 270 U.S. 9, 34-36; Mary

land v. Soper (No. 2), 270 U.S. 36, 38-39. Indeed,

that may have been the original design with respect to

civil rights cases also, the first removal statutes in

this area including no provision for remand. But

there can hardly be objection because the modern rule

is more cautious and imposes a heavier burden on the

removal petitioner. I t is of course a mere coincidence

that the jurisdiction of the federal court is usually

determined on a motion to remand. The judicial Code

is explicit that remand is required if the impropriety

of the removal “appears” “at any time before final

judgment.” 28' U.S.C. 1448(c). Thus, the return of

the case would be compelled if the removal court’s

want of jurisdiction came to light in connection with

any pretrial proceedings, whether or not a motion to

remand had been submitted. In any event, there is

no real anomaly in confusing the question of remov

ability and the merits of the challenge to the prosecu

tion. There are many instances in the law where a

procedural or jurisdictional issue is so bound up in

the merits that it cannot be decided separately. See,

e.g., Sam Fox Publishing Co. v. United States, 366

U.S. 683, 687-688, 694-695.

I t would be an exaggeration, however, to say that

removal and dismissal of the case exactly coincide un

der the suggested reading of the “denial” clause. The

case is removed by filing the petition in the federal

35

court and a copy with the clerk of the State court,

and that action automatically stays further proceed

ings in the local court, 28 U.S.C. 1446(e). That is

a safeguard of some importance. Moreover, if the

defendant is confined, the removal judge must, with

out awaiting the remand hearing, issue a writ of

habeas corpus to transfer the prisoner to federal cus

tody, and may then enlarge him on bail. 28 U.S.C.

1446(f). And, of course, the federal court acquires

jurisdiction to consider the merits of the petitioner’s

claim before the allegations are proved. Cf. Bell v.

Hood, 327 U.S. 678. Thus, removal, for some pur

poses, is effected quite independently of the ultimate

decision in the case. I t is only at the end that the

jurisdictional question merges into the disposition of

the case.

We conclude that there are no obstacles to a read

ing of the “denial” clause of the removal statute

which would permit a transfer of a criminal case on

the ground that the underlying prosecution violates

rights guaranteed by a federal law “providing for

equal rights.” I t need hardly be added that our sub

mission assumes the federal court will act with re

straint. We take it for granted that the court cannot

subsitute itself for a trial jury, deciding questions of

fact not open on a pretrial motion to quash the prose

cution: we claim no special powers for the court

merely because it is determining “removability” in

a proceeding labelled “hearing on motion to remand.”

A proper regard for the principle of federalism re

quires the caveat. But, once that is clear, there can be

no rightful claim of undue impingement on State pre

36

rogatives. Certainly, the State cannot complain be

cause the issue of jurisdiction is always open and the

final decision to exercise it awaits actual proof of the

petitioner’s allegations, to the same degree as is re

quired for dismissal of the case without trial.

B. THE “ COLOR OF AUTHORITY” PROVISION OF THE RE

MOVAL STATUTE (2 8 U.S.C. 1 4 4 3 ( 2 ) ) IS AVAILABLE TO

PRIVATE DEFENDANTS

The second removal provision of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866 {supra, p. 14—15)—carried forward in para

graph (2) of Section 1443—allowed “any officer, civil

or military, or other person” to transfer to the fed

eral court a suit or prosecution initiated against him

on account of “any arrest, imprisonment, trespasses-

or wrongs done or committed by virtue or under color

of authority” of the 1866 Act or the legislation re

lating to the Freedmen’s Bureau. This Court has

had no occasion to consider the reach of this provision.

Recently, however, the question whether paragraph

(2) of Section 1443 extends any protection to private

defendants not acting under compulsion of federal law

has been answered in the negative by a divided panel

of the court of appeals for the Second Circuit {New

York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255 (C.A. 2), certiorari

denied, 380 U.S. 977), a panel of the Third Circuit

{City of Chester v. Anderson, 347 F. 2d 823, petition

for certiorari pending, No. 443, this Term),25 a ma

jority of the Fourth Circuit {Baines v. Danville, No.

25 The question was not reached in the dissenting opinion of

Chief Judge Biggs and Judges Kalodner and Freedman on the

petition for rehearing in that case. See 347 F. 2d at 825.

37

9080, C.A. 4, decided January 21,1966, petition for cer

tiorari pending, Ho. 959, this Term),26 and, in the deci

sion below (R. 21, at 29-32), a panel of the Fifth Cir

cuit.27 We submit these decisions are erroneous and

that, the provision grants a right of removal to a pri

vate person with respect to criminal charges arising out

of his exercise of federal rights or privileges secured

by “any law providing for equal rights.”

Certainly, the words of the statute permit this con

struction. I t is in terms provided that “any * * *

person” may remove a “ prosecution” brought against

him “ for any * * * trespasses or wrongs done or

committed * * * under color of authority” of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866, or, today, any other federal

law “ providing for equal rights.” Historical con

notations and judicial gloss aside, the phrase “under

color of authority of law,” as a matter of plain

English, includes conduct which the actor claims he

is privileged to engage in by a provision of law—

for instance, to enter and seek service at a covered

restaurant immune from the local trespass law, as

the recent federal public accommodations statute “au

thorizes” him to do. And it is equally clear that any

charge arising out of such an assertion of rights is

embraced within the wrords “ trespasses, or wrongs”—

assuming we are bound by the terms of the original

statute, rather than the present text which permits

26 Judges Sobeloff and Bell, dissenting, did not decide the

question. But, see, ----- F. 2d at ——-, n. 54.

27 The F ifth Circuit did not consider the scope of paragraph

(2) in Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336, No. 147, this Term,,

or Cox v. Louisiana^ J47E^lkHjTJr

38

removal of a prosecution “for any act under color of

authority * *