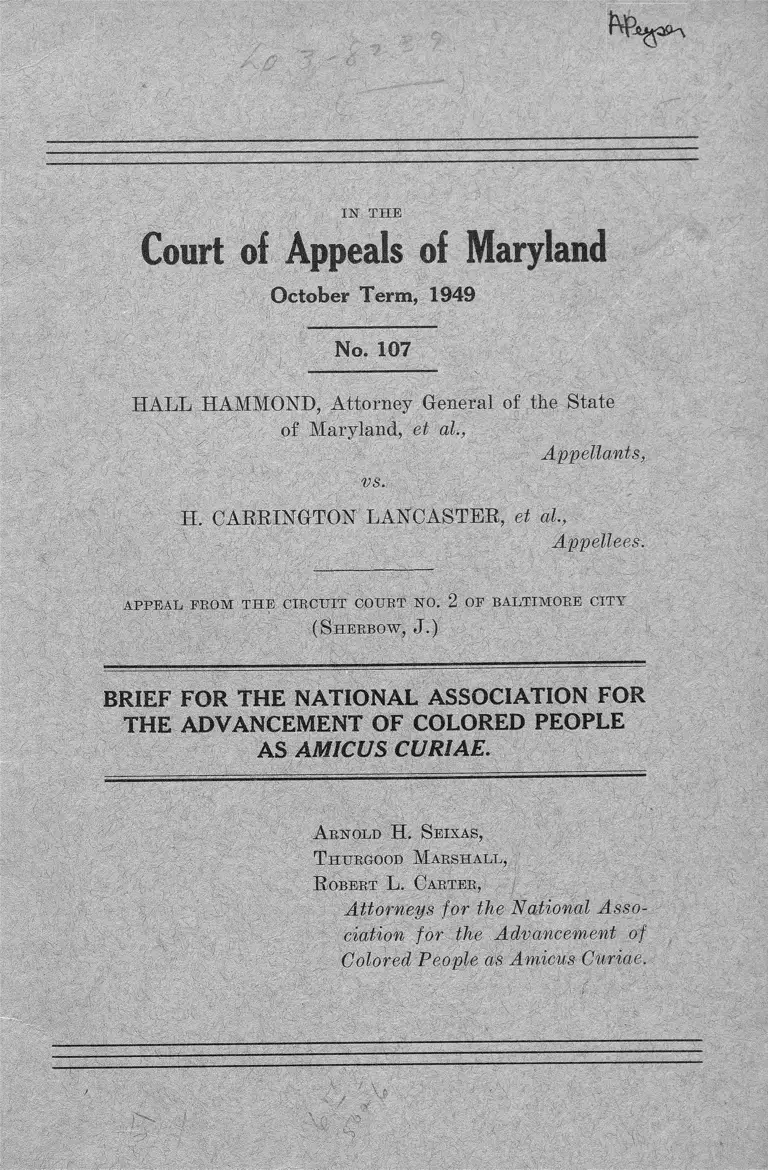

Hammond v. Lancaster Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hammond v. Lancaster Brief Amicus Curiae, 1949. 5965d252-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15e2321f-6949-419c-8abc-2c9471a34858/hammond-v-lancaster-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Court of Appeals of Maryland

October Term, 1949

No. 107

HALL HAMMOND, Attorney General of the State

of Maryland, <■/ al.

Appellants,

vs.

II. CARRINGTON LANCASTER, ct al,

Appellees.

APPEAL. FE O M T H E C IR C U IT CO U RT N O . 2 O F BA LTIM O R E C ITY

( S h b e b o w , J . )

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

A rnold H. S eixas,

T hurgood M a rshall ,

R obert L. C arter ,

Attorneys for the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of

Colored People as Amicus Curiae.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Interest of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People _____________ 1

Statement of the Case__________________________ 2

Argument:

I. The Subversive Activities Act abridges the con

stitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and

assembly ____ 1__________________________ 3

II. The Subversive Activities Act is violative of the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment in that it is a legislative enactment of the

theory of guilt by association____________ 15

Conclusion_________ ___ ■_______________________ 19

Table of Citations

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 _______________ 8

Bridges v. Wixon, 326 U. S. 135__________________ 3

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 _____________ 10

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 __ 12

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 __________________ 10

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 _________________ 8

Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U. S. 380 _________ __________ 11

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ___________ ______ 8

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 __ _____________ 8

Lanzetta v. United States, 306 U. S. 451___________ 12

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies,

Inc., 312 U. S. 287 _____________________ ____ 11

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319________________ 9

11

PAGE

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 __________ ____ 7

Schneider v. New Jersey, 308 U. S. 147____________ 3

Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U. S. 118_______ 15

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ___ ___________ 8

Terminello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 _________________ 8

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516_________________ 3

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88________________ 8

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S. 144 3

United States v. Josephson, 165 F. (2d) 82 (C. C. A.

2nd, 1947) _________________________________ 12

West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319

U. S. 624 _______________________________ ___ 3

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 _______________ 7

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ____ 12

M isc e lla n e o u s

Chafee, Freedom of Speech (1942) _______________15,17

IN THE

Court of Appeals of Maryland

October Term, 1949

No. 107

H all H a m m o n d , Attorney General of the State of

Maryland, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

H . C arrington L ancaster , et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L PR O M T H E C IR C U IT CO U RT N O . 2 OF B A LTIM O R E CITY

( S h e r b o w , J.)

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

Statement of Interest of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is an organization which for the past forty

years has unceasingly directed its entire efforts toward

improvement in living conditions of the millions of colored

citizens of the United States. The most important phase

in this program has been a struggle directed to secure in

reality for the Negroes those rights which are theoretically

theirs under the Constitution of the United States.

2

As a necessary corollary to this program the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People

must concern itself with any threat to weaken the con

stitutional guarantees, for such weakening must necessarily

imperil its fundamental program. This statute presents

such a threat for it is an unwarranted abridgement of the

constitutional freedoms of all people. The National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of Colored People files this

brief as amicus curiae, for we feel that in order to preserve

the freedom of colored people, we must necessarily fight to

preserve the freedom of all people.

Statem ent of the Case.

The appellees in the Court below, the Circuit Court No.

2 of Baltimore City, filed a Bill of Complaint praying that.

Chapters 86 and 310 of the Acts of 1949 of the General

Assembly of Maryland be declared unconstitutional in their

entirety. Chapter 86 is known as the Subversive Activities

Act of 1949 and Chapter 310 is a re-enactment of the Sub

versive Activities Act in the form of an emergency law.

Appellants demurred to the Bill of Complaint. The Court

below overruled the demurrers and held the chapters un

constitutional. Appellants appealed from the decree over

ruling the demurrers. The National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People secured this Court’s per

mission on the 8th day of November, 1949 to file this brief

as amicus curiae.

3

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The Subversive Activities Act abridges the consti

tutional guarantees of freedom of speech and assembly.

As a preface to all thinking on the question, it must he

pointed out that when the constitutional validity of a stat

ute restricting civil liberties is drawn in question, the nor

mal presumption of constitutionality adhering to most

legislation is no longer operative. Bridges v. Wixon, 326

U. S. 135, 165; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 529; West

Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 IT. S. 624, 638;

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 IT. 8. 144, 152.

This rule, which makes a distinction between statutes

affecting civil liberties and those affecting economic rights

and privileges, has had its most frequent application where

governmental restrictions on freedom of speech, press or

assembly are involved. In Schneider v. New Jersey (Town

of Irvington), 308 U. S. 147,161, the United States Supreme

Court said:

‘ ‘ This Court has characterized freedom of speech

and that of the press as fundamental personal rights

and liberties. (Citing eases.) This phrase is not an

empty one and was not lightly used. It reflects the

belief of the framers of the Constitution that exer

cise of these rights lies at the foundation of free

government by free men. It stresses, as do many

opinions of this Court; the importance of preventing

the restriction of enjoyment of these liberties. In

every case therefore, where legislative abridgement

of the rights is asserted, the Courts should be astute

to examine the effect of the challenged legislation.

Mere legislative preferences or beliefs respecting

matters of public convenience may well support

4

regulations directed at other personal activities, but

be insufficient to justify such as diminishes the exer

cise of rights so vital to the maintenance of demo

cratic institutions.”

Where a statute seeks to restrict freedom of speech and

assembly, the underlying issue is whether the legislature

can prohibit utterances having a bad tendency to bring

about unlawful acts, no matter how remote, or whether it

can prohibit only those words which are a direct incitement

to unlawful acts. In other words, can a state legislature

enact- into law the “ bad tendency” test or is the “ clear and

present danger” test to be our guide in the interpretation

of the scope and meaning of the First Amendment ? A dis

cussion of the political and social good resultant in the

application of the “ clear and present danger” rule and the

danger to freedom and democracy inherent in the applica

tion of the “ bad tendency” test is out of place here. Yet,

Milton, Mill, Chafee and United States Supreme Court

Justices H o lm es , B ra n d eis and Cardozo have long wrestled

with the problem, and their thinking has contributed much

to the present day interpretation of the constitutional

guarantees which the 1st Amendment, and by incorporation,

the 14th Amendment secure.

It is submitted that the instant statute is bad because it

has enacted into law the “ bad tendency” test rather than

the clear and present danger rule: Let us look at the stat

ute.

2(d) assist in the formation or participate in the man

agement or to contribute to the support of any

subversive organization or foreign subversive or

ganization knowing said organization to be a sub

versive organization or a foreign subversive or

ganization ;

5

3. It shall be a felony for any person after June 1,

1949, to become, or after September 1, 1949 to re

main a member of a subversive organization or a

foreign subversive organization knowing said or

ganization to be a subversive organization or for

eign subversive organization. Any person who

shall be convicted by a court of competent juris

diction of violating this section shall be fined not

more than Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000), or im

prisoned for not more than five (5) years, or both,

at the discretion of the court.

4. Any person who shall be convicted by a court of

competent jurisdiction of violating any of the pro

visions of Sections 2 and 3 of this Article, in addi

tion to all other penalties therein provided, shall

from the date of such conviction be barred from

(a) holding any office, elective or appointive, or any

other position of profit or trust in or employment

by the government of the State of Maryland or of

any agency thereof or of any county, municipal

corporation or other political sub-division of said

State;

(b) filing or standing for election to any public office

in the State of Maryland; or

(c) voting in any election held in this State.

10. No subversive person, as defined in this Article,

shall be eligible for employment in, or appointment

to any office, or any position of trust or profit in the

government of, or in the administration of the

business of this State, or of any county, munic

ipality, or other political sub-division of this State.

13. Every person, who on June 1, 1949 shall be in the

employ of the State of Maryland or of any political

subdivision thereof, other than those now holding-

elective office shall be required on or before August

1, 1949, to make a written statement which shall

6

contain notice that it is subject to the penalties of

perjury, that he or she is not a subversive person

as defined in this Article, namely, any person who

commits, attempts to commit, or aids in the com

mission, or advocates, abets, advises or teaches by

any means any person to commit, attempt to

commit, or aid in the commission of any act in

tended to overthrow, destroy or alter, or to assist

in the overthrow, destruction or alteration of, the

constitutional form of the Government of the

United States, or of the State of Maryland, or any

political sub-division of either of them, by revolu

tion, force, or violence; or who is a member of a

subversive organization or a foreign subversive

organization, as more fully defined in this Ar

ticle. * * *

All of these sections must be read in conjunction with the

definitions set out in section 1.

As a result of these sections organizations are criminal

and persons belonging to them guilty of a crime where such

organizations “ advocate” , “ advise” , or “ teach the over

throw, destruction or alteration of the constitutional form

of government of the United States * * # , by revolution,

force or violence”. No place in the government or teaching

post is open to a “ subversive person” as defined in the act.

Surely these sections are a direct and unwarranted abridge

ment of freedom of speech and assembly and place uncon

stitutional conditions upon holding public office or teaching

in the State of Maryland.

These sections proscribe words which merely advocate,

regardless of their nature or the circumstances under which

they are uttered. Penalties attach whether there is even

the remotest likelihood of the utterances bringing about un

lawful acts. A man or an organization can be punished

merely because the words used happen to conform to a cer

7

tain proscribed pattern. They are being punished not for

what they do, but for what they think. Speech is dangerous

only when it incites to unlawful acts. When it falls short

of incitement, it is merely the voicing of an opinion which

falls within the allowable area of free discussion. It is

submitted, therefore, that these sections of the act disre

gard the “ clear and present danger” test as laid down by

the Supreme Court of the United States in Schenck v.

United States, 249 U. S. 47.

‘ ‘ The question in every case is whether the words

used are used in such circumstances and are of such

a nature as to create a clear and present danger that

they will bring about the substantive evils that Con

gress has a right to prevent. It is a question of

proximity and degree.”

This test was ably clarified by Justice B r a n o eis , con

curring in Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 376.

“ Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify sup

pression of free speech and assembly. Men feared

witches and burned women. It is the function of

speech to free men from the bondage of irrational

fears. To justify suppression of free speech there

must be reasonable ground to fear that serious evil

will result if free speech is practiced. There must be

reasonable ground to believe that the danger appre

hended is imminent. There must be reasonable

ground to believe that the evil to be prevented is a

serious one. Every denunciation of existing law

tends in some measure to increase the probability

that there will be violation of it. Condonation of a

breach enhances the probability. Expressions of ap

proval add to the probability. Propagation of the

criminal state of mind by teaching syndicalism in

creases it. Advocacy of lawbreaking heightens it

still further. But even advocacy of violation, how

ever reprehensible morally, is not a justification for

denying free speech where the advocacy falls short,

of incitement and there is nothing to indicate that

the advocacy would be immediately acted on. The

wide difference between advocacy and incitement,

between preparation and attempt, between assem-

blying and conspiracy, must be borne in mind. In

order to support a finding of clear and present dan

ger it must be shown either that immediate serious

violence was to be expected or was advocated, or that

the past conduct furnished reason to believe that

such advocacy was then contemplated.”

Nor, can the “ clear and present dang*er” test be read

into these sections, notwithstanding the words “ clear and

present danger” are used in section 2(b) of the Act. The

express inclusion of the words there results in their implied

exclusion from the sections in question.

It is submitted that sections 2(d), 3, 4, 10 and 13 result

in an unwarranted abridgement of the freedoms guaranteed

in the First Amendment. The United States Supreme Court

has taken the position that although the rights of freedom

of speech and assembly are not absolute, the Fourteenth

Amendment protects them from impairment through state

action Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652, unless the speech

or assemblage sought to be proscribed constitutes a clear

and present danger that will bring about the substantive

evils that the legislature has a right to prohibit. Schenck

v. United States, supra; Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242;

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88; Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353; Bridges v.

California, 314 U. S. 252; Terminello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1.

In this connection appellants rely on the cases of Gitlow

v. United States, supra, and Whitney v. California, supra.

9

In these cases the Court speaking through Justice S anford

categorized state statutes in two classes:

(a) a statute which forbids certain action and which is

used against a defendant on the grounds that he has

used language to bring about the forbidden acts;

(b) a statute in which the legislature has defined cer

tain types of language and has considered the use

of such language punishable.

The appellants contend that the instant statute proscribes

certain defined language and therefore is protected by the

rule in the Gitlow case that where the constitutionality of

such a statute is drawn in question the Court must give

great weight to the legislative decision that the proscribed

utterances in themselves are dangerous, and that the “ clear

and present danger” test cannot be applied to those words

which fall into the pattern defined.

The implications of the Gitlow and Whitney cases, stand

ing alone, are that utterances no matter how trivial, no

matter how innocuous the circumstances under which they

are uttered, no matter how remote the tendency that they

will bring about the forbidden evils, are open to punish

ment if they fit the pattern of speech defined in the statute.

Thus, in times of hysterical fear, utterances could be deemed

dangerous by a state legislature where no real danger exists,

and the courts would be all but powerless to protect free

dom of discussion which is the sine qua non of our way of

life. See Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 327; Thomas

v. Collins, supra.

Although the Gitlow and Whitney cases have never been

expressly overruled, their sweeping effect has in a great

measure been curtailed if not nullified by later decisions of

the United States Supreme Court.

In later free speech cases the Court has tacitly dis

approved this “ bad tendency” test by the constant re

10

iteration of the “ clear and present danger” rule. Termi-

nello v. Chicago, supra; Bridges v. California, supra; Thorn

hill v. Alabama, supra; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 IT. 8.

296; Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367; Herndon v. Lowry,

supra; DeJonge v. Oregon, supra; Stromberg v. California,

supra.

In Herndon v. Lowry, supra, at 258, the Court expressly

noted the distinction between the types of statutes set out

in the Gitlow case and then proceeded to exorcise the “ bad

tendency” test from those statutes where the legislature

had proscribed certain language as dangerous.

“ The power of a state to abridge freedom of

speech and of assembly is the exception rather than

the rule and the penalising even of utterances of a

defined character must find its justification in a

reasonable apprehension of danger to organised,

government. * * * The limitation upon individual

liberty must have appropriate relation to the safety

of the state. Legislation which goes beyond this need

violates the principle of the Constitution.” (Italics

added.)

Certainly, in the instant statute where bare words regard

less of their nature or the circumstances in which they are

used can be punished, the legislature is purporting to pro

hibit words without having as its justification “ a reasonable

apprehension of danger to organized government ” .

In Stromberg v. California, supra, defendant was con

victed under a statute which prohibited the display of a red

flag, “ as a symbol or emblem of opposition to organized

government” . Chief Justice H u g h es delivered the opinion

of the Court, and in terms of the “ clear and present

danger” test declared the statute unconstitutional as an

encroachment upon the area of allowable political discus

sion. Language is not necessarily only written or spoken.

11

Speech is a symbolization of ideas; likewise a flag. To dis

play a flag as a symbol of opposition to organized govern

ment is no different than displaying a sign on which are

written words advocating opposition to organized govern

ment. We have, therefore, in the unconstitutional Oregon

statute, in effect, a legislative determination that a certain

and defined symbolization of ideas, or language, is danger

ous. But the Court instead of applying the rule in the

Gitlow case, used the “ clear and present danger” test to

declare the statute unconstitutional.

In view of what has been said before, it is clear that this

statute proscribes discussion before the clear and present

danger limitation is reached. But even if this test were met

the statute would at ill fall because its sweeping nature ap

plies an effective brake upon desirable discussion. What

man will feel free to speak or feel free to join an organiza

tion where the slightest chance exists that his words or the

literature of his organization might by some trick of fate

fall into the pattern proscribed by the statute. For that

reason even where the danger is sufficient to warrant a

limitation of freedom of speech or assembly, the statute

must be narrowly drawn to meet the supposed evil. Thorn

hill v. Alabama, supra; Milk Wagon Drivers Union of Chi

cago v. Meadowmoor Dairies, Inc., 312 IJ. S. 287. In this

field, therefore, the activity regulated or prohibited—the

substantive evil must be so clearly and specifically defined

as to render its application to any other activity unlikely.

In several instances state courts reflecting current

hysteria have been able to fit entirely innocuous activities

of persons into the sweeping terms of statutes similar to

the one in question here. Cf. DeJonge v. Oregon, supra;

Fiske v. Kansas, 274 IJ. S. 380. The result of such deci

sions can only be to create a medium of fear through which

12

controversial discussion is restrained. This danger is

pointed up in the remarks of Justice Clarke, dissenting in

United States v. Josephson, 165 F. (2d) 82, 93 (C. C. A. 2d,

1947).

11 * * * the teaching of experience, after nearly three

decades of a well-nigh pathological fear of ‘Com

munism’ under constant investigation by Congress,

O gden , The Dies Committee, 2d Rev. Ed. 1945, 14-37,

might suggest that there was more to be feared from

the fear itself than from the supposed danger.”

Closely linked to the narrowly drawn statute require

ment is the rule which states that a deprivation of due1

process of law exists where a statute punishing for an of

fense is so vague and indefinite in its terms that it contains

no reasonable standard of guilt. A man of common intelli

gence cannot be required at peril of life, liberty or prop

erty to speculate as to the meaning of a statute. Lametta

v. United States, 306 IT. 8. 451; Winters v. New Yorlc, 333

U. S. 507; Herndon v. Lowry, supra; Stromherg v. Cali

fornia, supra; Connally v. General Construction Co., 269

IT. S. 385.

In Connally v. General Construction Co., supra, it was

stated:

‘ ‘ That the terms of a penal statute creating a new

offense must be sufficiently explicit to inform those

who are subject to it what conduct on their part will

render them liable to its penalties, is a well rec

ognized requirement, consonant alike with ordinary

notions of fair play and the settled rules of law.

And a statute which either forbids or requires the

doing of an act in terms so vague that men of com

mon intelligence must necessarily guess at its mean

ing and differ as to its application, violates the first

essential of due process of law.”

13

It is felt that various sections of the instant statute fall

within the above rule and therefore constitute a depriva

tion of due process.

Section 1 pertaining to definitions states:

“ ‘Subversive Organization’ means any organiza

tion which engages in or advocates, abets, advises,

or teaches, or a purpose of which is to engage in or

advocate, abet, advise, or teach activities intended

to overthrow, destroy or alter, or to assist in the

overthrow, destruction or alteration of, the consti

tutional form of the government of the United States,

or of the State of Maryland, or of any political sub

division of either of them, by revolution, force, or

violence. ’ ’

Under the terms of this section an organization would be

“ subversive” and its existence unlawful if it “ advocated”

the ‘ ‘ alteration of the constitutional form of government of

the United States * * * by r e v o lu t io n The word “ revo

lution” is defined in Ballantine’s Law Dictionary (1948

Ed.) 1142,

“ The word has been variously defined as a radical

change or modification of the government (5 Tex. 34,

75); the overthrow of an established political sys

tem (Ballantine’s Law Dictionary); a fundamental

change in government or in the political constitution

of a country effected suddenly and violently, and

mainly brought about by internal conditions (New

Standard Encyclopedia); a radical change in social

or governmental conditions; the overthrow of an

established political system, generally accompanied

by far-reaching social changes. See State v. Dia

mond, 27 N. M. 477, 20 A. L. R. 1527, 1532, 202 Pac.

Rep. 988.”

Thus a person or organization advocating the alteration

of the constitutional form of government of the United

States could be guilty of violating this statute if such ad

14

vocacy were intense, inciting, or fervent. As Mr. Chief

Justice H u g h e s stated in Stromberg v. California, supra,

the First Admendment was intended to protect:

‘ ‘ The maintenance of the opportunity for free

political discussion to the end that government may

be responsive to the will of the people and that

changes may be obtained by lawful means, and op

portunity essential to the security of the Republic,

is a fundamental principle of our constitutional sys

tem. A statute which upon its face, and as authori

tatively construed, is so vague and indefinite as to

permit the punishment of the fair use of this oppor

tunity is repugnant to the guaranty of liberty con

tained in the 14th Amendment.”

The same defect appears in the subsection defining

“ subversive person” in section 1 and in section 2, subsec

tion (a) and (b).

Section 3 makes it a felony for any person to be a men-

ber of a “ subversive organization * * # knowing said or

ganization to be a subversive organization” . More shall

be said about this section later, but it is enough to point

out here the ambiguity of the word “ knowing” . Must the

knowledge be actual or constructive? Is every person put

on notice to analyse the purposes of his respective organi

zation in line with the definitions in the statute or may he

wait until a judicial determination of “ subversiveness” .

Other words in this statute such as “ member” in sec

tion 3 and “ security” in section 2(b) are words important

to the enforcement of this statute, and are so loaded in their

ambiguity that enforcement could easily go not only against

the illegal but also against the merely objectionable.

Clearly this statute in its vagueness and uncertainty

sets no reasonable standard of guilt and results in a de

privation of due process of law.

15

II.

The Subversive Activities Act is violative of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in that it

is a legislative enactment of the theory of guilt by asso

ciation.

Section 3 of this act and section 10 when read in con

junction with section 1 deprive all persons coming within

their terms of due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment in that, these sections embody the principle of

guilt by association. That guilt is personal is a funda

mental concept of our law. C h a e e e , Freedom of Speech

(1942), 471-484. Where a statute seeks to hold a person

criminally responsible not upon his own actions but upon

the actions of others with whom he associates, it under

mines this fundamental concept. Schneiderman v. United

States, 320 U. S. 118; Bridges v. Wixon, supra; Cf. DeJonge

v. Oregon, supra; see also Justice B eandeis concurring,

Whitney v. California, supra.

Section 3 states that, “ it shall be a. felony for any per

son # # # to become, or * * * to remain a member of a

subversive organization knowing said organization to be

a subversive organization or foreign subversive organi

zation” .

Section 10 states that,

“ no subversive person as defined in this article, shall

be eligible for employment in, or appointment to any

office, or any position of trust or profit in the gov

ernment of, or in the administration of the business

of this state, or of any county, municipality, or other

political subdivision of this state.”

16

The Article in section 1 defines “ subversive person” as

any person who inter alia “ is a member of a subversive

organization or a foreign subversive organization” .

That both these sections aim to reach the person who is

merely a member of an organization and to make member

ship punishable per se is clear from the presence of sec

tion 2, subdivision (c), which makes it a felony to conspire

to violate the act. Certainly this conspiracy section covers

the “ subversive” activities of the members of an organiza

tion in violation of the act. Section 3 and the portions of

sections 10 and 1 referred to above are totally unnecessary

unless it was the intent of the framers to punish member

ship alone without reference to actions or speech in further

ance of the purposes of the organization.

Thus under this act a man is guilty merely because of

his status as a member—what he says or does is not mate

rial. What other members say or do is material. This is

guilt by association in its most patent and abject form.

In the case of DeJonge v. Oregon, supra, defendant, a

member of the Communist Party was convicted on the

ground that he assisted in conducting a meeting of the Com

munist Party at which the doctrine of criminal syndicalism

was advocated. The meeting in fact was lawful and no

criminal syndicalism was advocated. The evidence pre

sented to secure the conviction was literature of the Com

munist Party which advocated criminal syndicalism. Hence,

all that defendant was convicted for was his presence at a

meeting of a party which advocated criminal syndicalism.

The Supreme Court reversed the conviction on the grounds

that defendant’s right of freedom of assembly was abridged.

It is apparent though that this decision is grounded on the

concept that guilt is personal. The Supreme Court would

not allow a conviction to stand where the defendant’s only

17

act was membership in and presence at a meeting of a party

advocating the overthrow of the government.

In Schneiderman v. United States, supra, the concept of

guilt by association was expressly rejected. This case in

volved a proceeding to cancel defendant’s certificate of citi

zenship on the grounds that defendant did not under the

terms of the statute behave like a man of good moral char

acter, attached to the principles of the Constitution of the

United States, and well disposed to the good order and

happiness of the same. The evidence on this question was

that defendant was a member of the Communist Party. The

Court rejected the evidence saying that membership qua

membership was immaterial.

To say that section 3 cures itself of the defect of guilt

by association by requiring knowledge of the member that

the organization is “ subversive” in purpose is to attribute

great power of analysis to the common man. The quandry

of the liberal joiner is deftly stated by C h a f e e , Freedom of

Speech (1942) at 475.

‘4 How many members of radical organizations can

fairly be supposed to have known on June 28th, 1940,

that their organization was within that new statute?

After all, the purposes of an organization do not

stand out like a sore thumb. One can read through

the whole platform and campaign handbook of a

party, without being sure what its real purposes are.

They are concealed behind a printed compromise de

signed to reconcile the widely divergent groups which

make up any political party. Were the real purposes

of the Republican Party in 1928 those of Andrew

Mellon or Herbert Hoover or George Norris? As

for the Democrats, remember the Madison Square

Convention. What is true of the major parties is

a fortiori true of radical organizations. A radical by

his very nature tends to keep on splitting off. Bris-

18

senden’s book on the I.W.W. is largely a history of

factional fights. How can any member of such an

organization be sure precisely what it stands for!

Joining the Communist Party is not like joining a

cocktail party, where everybody knows its purpose.”

It must be noted that while section 3 contains the require

ments of knowledge, no such requirement exists in sections

10 and 1. A man under these sections can be barred from

office on the grounds of membership alone.

In Bridges v. Wixon, supra, the Supreme Court de

nounced the deportation statute on the ground that under

it an alien was deportable if he was a member or an affiliate

of an organization which advocated the overthrow of the

government, and said,

‘ ‘ The statute does not require that an alien, to be

deportable, must personally advocate or believe in

the forceful overthrow of the Government. It is

enough if he is a member or an affiliate of an organi

zation which advocates such a doctrine. And in this

case the Government admits that it has neither

claimed nor attempted to prove that Harry Bridges

personally advocated or believed in the proscribed

doctrine. There is no evidence, moreover, that he

understood the Communist Party to advocate violent

revolution or that he ever committed or tried to com

mit an overt act directed to the realization of such an

aim.

“ The doctrine of personal guilt is one of the most

fundamental principles of our jurisprudence. It

partakes of the very essence of the concept of free

dom and due process of law. Schneiderman v. United

States, 320 U. S. 118, 154, 87 L. Ed. 1796, 1817, 63

S. Ct. 1333. It prevents the persecution of the in

nocent for the beliefs and actions of others. See

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1941) pp.

472-475.

19

“ Yet the deportation statute on its face and in

its present application flatly disregards this rule. It

condemns an alien to exile for beliefs and teachings

to which he may not personally subscribe and of

which he may not even be aware. This fact alone is

enough to invalidate the legislation. Cf. Dejonge

v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 81 L. Ed. 278, 57 S. Ct. 255;

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 IT. S. 242, 81 L. Ed. 1066, 57 S.

Ct. 732; Whitney v. California, 274 IT. S. 357, 71 L.

Ed. 1095, 47 8. Ct. 641.”

Conclusion.

W h erefore , fo r reasons h erein above s ta ted , it is

resp ec tfu lly p ra y e d th a t th e ju d g m en t of th e lo w er

cou rt should be sustained.

A rnold H. S eixas,

T hubgood M arsh a ll ,

R obert L. C arter ,

Attorneys for the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of

Colored People as Amicus Curiae.

L aw yers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300