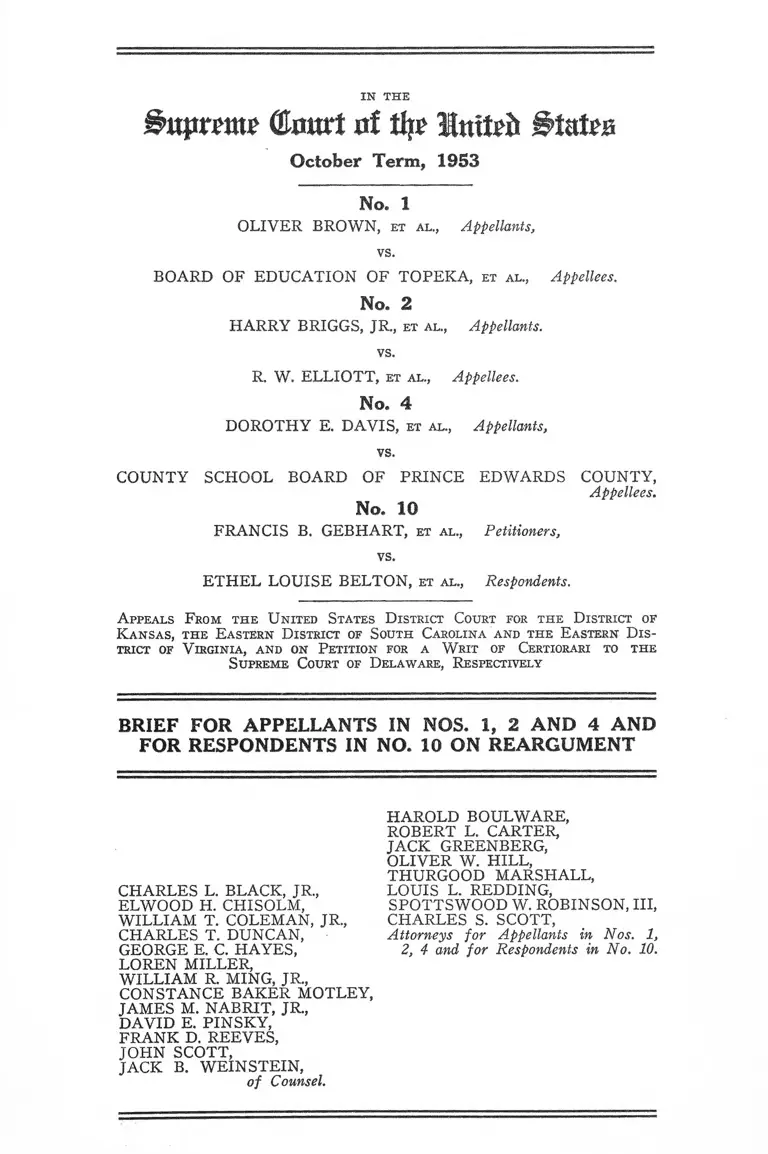

Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 4 and for Respondents in No. 10 on Reargument

Public Court Documents

December 15, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 4 and for Respondents in No. 10 on Reargument, 1953. 462767cf-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15f02044-93f9-4278-b0b5-2f6099cd16e9/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants-in-nos-1-2-and-4-and-for-respondents-in-no-10-on-reargument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

xmt (Emtrt at % MmUb States

October Term, 1953

No. 1

OLIVER BROWN, et al ., Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, ex a l ., Appellees.

No. 2

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al,, Appellants.

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, et al ., Appellees.

No. 4

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, et al ., Appellants,

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARDS COUNTY,

Appellees.

No. 10

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, et al ., Petitioners,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, et al ., Respondents.

A ppeals F rom th e U nited States D istrict Court for th e D istrict of

K an sa s , the E astern D istrict of South Carolina and the E astern D is

trict of V irginia, and on Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the

S upreme Court of D elaware, R espectively

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS IN NOS. 1, 2 AND 4 AND

FOR RESPONDENTS IN NO. 10 ON REARGUMENT

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.,

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM,

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.,

CHARLES T. DUNCAN,

GEORGE E. C. HAYES,

LOREN MILLER,

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

JAMES M. NABRIT, JR.,

DAVID E. PINSKY,

FRANK D. REEVES,

JOHN SCOTT,

JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

of Counsel.

HAROLD BOULWARE,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

JACK GREENBERG,

OLIVER W. HILL,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

LOUIS L. REDDING,

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III,

CHARLES S. SCOTT,

Attorneys for Appellants in Nos. 1,

2, 4 and for Respondents in No. 10.

F O R E W O R D

This is a reprint of the brief which was filed in the

United States Supreme Court on November 16, 1953, pur

suant to an order of that Court setting the school segrega

tion cases down for reargument. When the Court ordered

this reargument, it requested counsel to answer five ques

tions. Certain of these questions necessitated extensive

research into the history of the adoption and ratification

of the Fourteenth Amendment to determine whether the

Amendment was intended to abolish segregation in public

schools. Other questions, involving the power of the

Court to abolish segregation in education and the means

by which this could be effectively accomplished by judicial

mandate, also required intensive analysis. To this end,

the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

set out to obtain the most reliable information available.

Research was divided into three sections: law, history

and sociology. The staff was fortunate in obtaining the

services of Dr. John A. Davis, now Associate Professor of

Government at the College of the City of New York, to

outline and direct the course of non-legal research.

Dr. Mabel Smythe was engaged as his chief assistant. Dr.

Albert Blum, historian, and Miss Julia Baxter assisted in

the research.

Basic monographs on the history of the adoption and

ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment were prepared

by Dr. Alfred H. Kelly, Professor of Constitutional His

tory at Wayne University, Howard Jay Graham, Law

Librarian of the Los Angeles County Bar Association, and

Dr. Horace M. Bond, President of Lincoln University,

Pennsylvania. Dr. Bond was assisted in his work by Dr.

Marion Wright, Professor of Education at Howard Uni

versity and Smith Haynes, graduate student at Columbia

University. Dr. C. Vann Woodward, Professor of Ameri

can History at the Johns Hopkins University and Dr. John

Hope Franklin, Professor of American History at Howard

University, wrote monographs on the history of recon

struction in the South and on the purposes and results of

segregation. Dr. Kenneth Clark, Associate Professor of

Psychology at the College of the City of New York, was

responsible, with the aid of Miss June Shagaloff, for ex

ploring methods used to bring about desegregation in many

situations.

We are also indebted to Professor Howard K. Beale,

Dr. Charles S. Johnson, Dr. Buell Gallagher, Dr. Charles

Wesley, Professor Robert K. Carr, Professor John Frank,

Professor Paul Freund, Dean George M. Johnson, Pro

fessor Walter Gellhorn, Dr. Charles S. Thompson, Pro

fessor David Haber, Dr. Milton Konvitz, Professor Robert

Cushman, Jr., U. S. Tate, David Feller, Dr. Harvey C.

Mansfield, Professor Rayford Logan, Professor Wallace

Sayre, Joseph Robison, Dr. Lillian Dabney and others

for assisting the lawyers of record in the formulation

of the basic approach to the questions propounded by

the Court and for specific criticism and advice on the

brief itself.

In addition, we wish to express our deep appreciation

to those lawyers and scholars who did research on the

history of the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment

and on the history of segregation in public schools in each

of the 37 states which were in the Union at the time the

Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. We regret that the

list of lawyers who worked in the 37 states is too long to

permit us to name them individually.

This brief represents a pioneering effort and will remain

an important landmark in the development of the law.

While this brief could not have been finished without the

help and assistance indicated, our own staff assumes full

responsibility for any errors or omissions.

A r t h u r B. S pihgarn

President

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

December 15, 1953.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Explanatory Statement .................................................. 2

No, 1

Opinion B elow ................................................................... 2

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 2

Statement of tlie C ase ...................................................... 2

Specification of Errors .................................................. 3

No. 2

Opinions Below ............................................. 4

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 4

Statement of the Case .................................................... 4

Specification of Errors .................... 6

No. 4

Opinion Below ................................................................. 6

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 6

Statement of the Case .................................................... 7

Specification of E rro rs .................................................... 8

No. 10

Opinions Below ............................................................... 9

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 9

Statement of the Case .................................................... 10

This Court’s Order ............................................. 13

Summary of Argum ent.................................................... 15

Argument ......................................................................... 21

PAGE

11

ARGUMENT

P art One

PAGE

I. Normal exercise of the judicial function calls for

a declaration that the state is without power to

enforce distinctions based upon race or color in

affording educational opportunities in the pub

lic schools................................................................. 21

II. The statutory and constitutional provisions in

volved in these cases cannot he validated under

any separate but equal concept............................. 31

A. Racial Segregation Cannot Be Squared With

the Rationale of the Early Cases Interpreting

the Reach of the Fourteenth Amendment . . . . 32

B. The First Time the Question Came Before the

Court, Racial Segregation In Transportation

Was Specifically Disapproved......................... 36

C. The Separate But Equal Doctrine Marked An

Unwarranted Departure From the Main

Stream of Constitutional Development and

Permits the Frustration of the Very Purposes

of The Fourteenth Amendment As Defined

by This Court .................................................... 38

D. The Separate But Equal Doctrine Was Con

ceived in Error ................................................. 40

1. The Dissenting Opinion of Justice Harlan

in Plessy v. Ferguson................................ 40

2. Custom, Usage and Tradition Rooted in the

Slave Tradition Cannot Be the Constitu

tional Yardstick for Measuring State Ac

tion Under the Fourteenth Amendment . . 42

3. Preservation of Public Peace Cannot Jus

tify Deprivation of Constitutional Rights 43

I ll

4. The Separate but Equal Doctrine Deprives

Negroes of That Protection Which the

Fourteenth Amendment Accords Under the

General Classification Test ....................... 45

E. The Separate But Equal Doctrine Has Not

Received Unqualified Approval in This Court 47

F. The Necessary Consequence of the Sweatt and

McLaurin Decisions is Repudiation of The

Separate But Equal Doctrine ......................... 48

III. Viewed in the light of history the separate but

equal doctrine has been an instrumentality of

defiant nullification of the Fourteenth Amend

ment .......................................................................... 50

A. The Status of the Negro, Slave and Free, Prior

to the Civil W a r ................................................ 50

B. The Post War Struggle .................................. 53

C. The Compromise of 1877 and the Abandon

ment of Reconstruction.................................... 56

D. Consequences of the 1877 Compromise........... 57

E. Nullification of the Rights Guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment and the Reestablish

ment of the Negro’s Pre-Civil War Inferior

Status Fully Realized ...................................... 62

Conclusion to Part I ....................................................... 66

P art T wo

I. The Fourteenth Amendment was intended to de

stroy all caste and color legislation in the United

States, including racial segregation..................... 67

PAGE

IV

A. The Era Prior to the Civil War "Was Marked

By Determined Efforts to Secure Recognition

of the Principle of Complete and Real Equality

For All Men Within the Existing Constitu

PAGE

tional Framework of Our Government.......... 69

Equality Under Law ...................................... 70

B. The Movement For Complete Equality

Reached Its Successful Culmination in the

Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment .. 75

C. The Principle of Absolute and Complete

Equality Began to Be Translated Into Fed

eral Law as Early as 1862 ............................. 77

D. From the Beginning the Thirty-Ninth Con

gress Was Determined to Eliminate Race

Distinctions From American L a w ................. 79

The Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment 93

E. The Fourteenth Amendment Was Intended to

Write into the Organic Law of the United

States the Principle of Absolute and Com

plete Equality in Broad Constitutional Lan

guage ................................................................. 103

F. The Republican Majority in the 39th Con

gress Was Determined to Prevent Future

Congresses from Diminishing Federal Pro

tection of These Rights .................................. 108

G. Congress Understood That While the Four

teenth Amendment Would Give Authority to

Congress to Enforce Its Provisions, the

Amendment in and of Itself Would Invali

date All Class Legislation by the States . . . . 114

Congress Intended to Destroy All Class

Distinction In L a w ............... ....................... 118

Y

H. The Treatment of Public Education or Segre

gation in Public Schools During the 39th

Congress Must Be Considered in the Light

of the Status of Public Education at That

time ................................................................ 120

I. During the Congressional Debates on Pro

posed Legislation Which Culminated in the

Civil Rights Act of 1875 Veterans of the

Thirty-Ninth Congress Adhered to Their

Conviction That the Fourteenth Amendment

Had Proscribed Segregation in Public Schools 126

II. There is convincing evidence that the State Legis

latures and conventions which ratified the Four

teenth Amendment contemplated and understood

that it prohibited State legislation which would

require racial segregation in public schools . . . . 139

A. The Eleven States Seeking Readmission

Understood that the Fourteenth Amendment

Stripped Them of Power to Maintain Segre

PAGE

gated Schools .................................................... 142

Arkansas ........................................................... 143

North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana,

Georgia, Alabama and F lorid a ................... 144

Texas ................................................................. 151

V irginia............................................................... 152

Mississippi ......................................................... 153

Tennessee ......................................................... 155

B. The Majority of the Twenty-two Union States

Ratifying the 14th Amendment Understood

that it Forbade Compulsory Segregation in

Public Schools .................................................. 157

West Virginia and M issouri........................... 158

The New England S tates................................ 159

The Middle Atlantic S tates............................. 164

The Western Reserve States ......................... 170

The Western States ........................................ 177

Y1

C. The Non-Batifying States Understood that

the Fourteenth Amendment Forbade Enforced

PAGE

Segregation in Public Schools.......................... 182

Delaware ........................................................... 182

Maryland ........................................................... 183

Kentucky ........................................................... 184

California ................................................... 185

Conclusions to Part I I ................................................... 186

P art T hree

1. This Court should declare invalid the constitu

tional and statutory provisions here involved

requiring segregation in public schools. After

careful consideration of all of the factors involved

in transition from segregated school systems to

unsegregated school systems, appellants know of

no reasons or considerations which would war

rant postponement of the enforcement of appel

lants’ rights by this Court in the exercise of its

equity powers , ...................................................... 190

A. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that a

decree he entered directing that appellants

he admitted forthwith to public schools with

out distinction as to race or c o lo r ................. 190

B. There is no equitable justification for post

ponement of appellants’ enjoyment of their

rights ................................................................. 191

C. Appellants are unable in good faith to sug

gest terms for a decree which will secure

effective gradual adjustment because no such

decree will protect appellants’ r igh ts ........... 195

Conclusion ....................................................................... 198

Supplement ....................................................................... 199

Table of Cases

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 4 6 ........................... 99

Alston v. School Board, 112 F. 2d 992 (CA 4th 1940),

cert, denied 311 U. S. 693 ...................................... 25

Ammons v. School Dist. No. 5, 7 R. I. 596 (1864) . . . . 159

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 ................................ 24

Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U. S. 2 7 ............................... 45

Barrows v. Jackson, — II. S. —, 97 L. ed. (Advance,

p. 961) ............................................ ........................... 22

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. 2d 391 (CA 4th 1949)........ 25

Bell’s Gap R. R. Co. v. Pennsylvania, 134 U. S. 232 46

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 4 5 ................... 48

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 . . . 25

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 .........................16, 22, 44,

47,194

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 1 1 0 ................................ 35

Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14 (C. A. D. C. 1950)___ 8

Cassell v. Texas, 339 IT. S. 282 .................................... 24

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (CA 4th 1951),

cert, denied 341 U. S. 9 1 .......................................... 48

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Co., 218 U. S.

71 ................................................................................ 42,48

Cities Service Gas Co. v. Peerless Oil & Gas Co.,

340 U. S. 1 7 9 ............................................................. 46

Civil Rights Cases, 109 IT. S. 3 .................................... 35

Clark v. Board of School Directors, 24 Iowa 266

(7868) ........................................................................150,182

Coger v. N. W. Union Packet Co., 37 Iowa 145 (1873) 182

Cory v. Carter, 48 Ind. 327 (1874) ............................. 173

Crandell v. State, 10 Conn. 339 (1834) ................... 207, 208

Crowell v. Benson, 285 U. S. 2 2 .................................... 48

Cumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 .............................................................................. 43

Dallas v. Fosdick, 50 How. Prac. (N. Y.) 249 (1869) 169

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ............................. 125

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

"tf- s - 100 ................................................................... 193

Y ll

PAGE

vm

Dove v. Ind. School Dist., 41 Iowa 689 (1875).......... 182

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 1 8 0 ......................... 23

Estep v. United States, 327 U. S. 114 ......................... 48

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 .................................... 24

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 .......................... . 35

Foister v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 937

(E. D. La. 1952) unreported.................................... 49

Giozza v. Tiernan, 148 U. S. 657 ................................ 46

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 ............................ 47,48

Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Tennes

see, 342 U. S. 517 ................................................... 48

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 ..................... 25, 58

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 ............. 23, 43, 48

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ........................................ 24

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 ......... 22, 23, 24

Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333

U. S. 203 ................................................................... 125

PAGE

Jones v. Better Business Bureau, 123 F. 2d 767, 769

(CA 10th 1941) ....................................................... 28

Jones v. VanZandt, 46 U. S. 2 1 5 ................................ 220

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 ........... 23, 24

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 .................................... 25

Lewis v. Henley, 2 Ind. 332 (1850) ............................. 172

McCardle v. Indianapolis Water Co., 272 U. S. 400 . . 125

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th

1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 951 ............................. 48, 49

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 ......................................................... 16,17,22,26,27,30,

31, 43, 47, 48,49

McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U. S. 1 ......................... 46

Marchant v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 153 U. S. 380 . . . . 46

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266 ............. 16, 46

Miller v. Schoene, 276 U. S. 272 ................................ 125

Minneapolis & St. Louis Ry. Co. v. Beckwith, 129

U. S. 26 ....................................................................... 46

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . . 22, 47

IX

Mitchell v. Board of Regents of University of Mary

land, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore City

Court 1950) unreported............................................ 49

Monk v. City of Birmingham, 185 F. 2d 859 (CA 5th

1950), cert, denied 341 U. S. 940 ............................. 45

Moore v. Missouri, 159 U. S. 673 ................................. 46

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 .........................25, 45, 48

Nancy Jackson v. Bullock, 12 Conn. 38 (1837).......... 220

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 ................................... 35

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 7 3 .................................. 24

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ............................... 46

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 .......................... 22, 24

Payne v. Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 894

(E. D. La. 1952) unreported................................... 49

People v. Easton, 13 Abb. Prac. N. S. (N. Y.) 159

(1872) ......................................................................... 169

People ex rel. King v. Gallagher, 92 N. Y. 438 (1883) 170

People ex rel. Workman v. Board of Education of

Detroit, 18 Mich. 400 (1869).................................... 175

Pierce v. Union Dist. School Trustees, 17 Vroom

(46 N. J. L.) 76 (1884) ............................................ 168

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ............................... 24

PAGE

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 . . . 15,17, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38,

39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 48,

61, 62, 65,118,183

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389.. 16, 46

Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall 445 ................. 36, 37, 39, 40

Railway Mail Assn. v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88 ................. 26,170

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (CA 4th 1947), cert.

denied 333 U. S. 875 ................................................ 25

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849) 71

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .........................16, 21, 43, 75

Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393 ................. 41, 52, 75, 76, 79,

83, 98,117

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S. 5 0 ............................... 24

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 ................. 47,190

X

PAGE

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 .............................. 16, 46

Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall. 36 ............. 19, 32, 39,133,

137,141,142

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 .................................. 25,43

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 ...................................... 16, 46

Smith y . Directors of Ind. School Dist., 40 Iowa 518

(1875) .......................................................... .............. 182

South v. Peters, 339 U. S. 276 ...................................... 23

State y . Duffy, 7 Nev. 342 (1872) ...................... 181

State v. Board of Education, 2 Ohio Cir. C't. Rep. 557

(1887) .......................................................................... 172

State v. Grubbs, 85 Ind. 213 (1883) ............................... 173

State ex rel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1872) 171

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co., 323 U. S.

192 ........................................................ 16,24

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ............... 16, 33, 39,

119,142

Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civil Action No.

30 (W, D. Va. 1950) unreported................................ 48

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ........... 16,17, 26, 27, 30, 31,

43, 47, 48,125,190

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 ............................................................................... 24

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 .................................... 25, 58

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 .................................... 16, 24, 46

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210......................................... 16, 24

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 ................... 35

Van Camp v. Board of Education, 9 Ohio St. 406

(1859) ......................................................................... 171

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 .................................. 35

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874).................................. 185

West Chester & Phila. R. Co. v. Miles, 5 Smith (55

Pa.) 209 (1867) ......................................................... 164

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 ............................................................ 30

XI

Weyl v. Comm, of Int. Eev., 48 F. 2d 811, 812 (CA 2d

1931) .......................................................................... 28

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State

University, 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950),

aff’d 340 U. S. 909 ..................................................... 48

Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal. 588 (1890) .............. 185

Yesler v. Board of Harbor Line Commissioners, 146

U. S. 646 ..................................................................... 46

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ............................. 22, 35

Youngstown Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S. 579 ................... 192

Constitutions, Statutes and Session Laws

Federal

Eev. Stat. § 1979 (1875), 8 U. S. C. § 4 3 ................... 124

28 U. S. C., § 1253 ....................................................... 2, 6

28 U. S. C., §1257(3) ................................................. 9

28 U. S. C., § 2101(b) .................................................. 2,6

28 U. S. C., § 2284 ....................................................... 3, 5

28 U. S. C. § 863 (1946) .............................................. 196

12 Stat. 376 (1862) ...................................................... 77

12 Stat. 407 (1862) ....................................................... 77

12 Stat. 805 (1863) ....................................................... 78

13 Stat. 536, 537 (1865) ................................................ 78

14 Stat. 358 (1866) ....................................................... 139

14 Stat. 364 (1866) ..................................................... 157

14 Stat. 391 (1867) ....................................................... 177

14 Stat. 428 (1867) ................................................’ ’ .141,142

15 Stat. 72 (1868) ....................................................... 143’ 144

15 Stat. 73 (1868) ....................................................... 144,’ 147

16 Stat. 62 (1870) ......................................................... ’ 153

16 Stat. 67 (1870) ....................................................... 154

16 Stat. 80 (1870) ....................................................... 151

16 Stat. 363 (1870) ....................................................... 151

PAGE

Statutes and Constitutions

State

Ala. Const. 1867, Art. X I .......................................... .. 149

Ala. Laws 1868, App., Acts Ala. Bd. Educ.................. 150

Ark. Acts 1866-67, p. 100 .............................................. 142

Ark. Acts 1873, p. 423 .................................................. 144

Ark. Const. 1868, Art. IX, § 1 ............... .................... 143

Ark. Dig. Stats., c. 120, § 5513 (1874)......................... 144

Ark. Laws (1873) ......................................................... 56

Cal. Stats. 1866, p. 363 .................................................. 185

Cal. Stats. 1873-74, p. 9 7 .............................................. 185

Cal. Stats. 1880, p. 4 8 ................................................... 185

Conn. Acts 1866-68, p. 206 ............................................ 159

Del. Const. 1897, Art. X, § 1 ........................................ 11

Del. Const. 1897, Art. X, § 2 ........................................ 183

13 Del. Laws 256 (1867) .............................................. 183

Del. Laws 1871-73, pp. 686-87 ...................................... 183

Del. Laws 1875, pp. 82-83 ............................................ 183

Del. Laws 1875-77, c. 1 9 4 .............................................. 183

Del. Laws 1881, c. 362 ................................................. 183

Del. Rev. Code, Par. 261 (1935) .................................. 11

Del. Rev. Stats., c. 42, § 12 (1874) .............................. 183

Fla. Const. 1868, Art. VIII, § 1 .................................. 144

Fla. Const. 1885, Art. VII, § 2 .................................... 145

Fla. Laws 1869 ............................................................. 144

Fla. Laws 1873, c. 1947 ................................................ 145

Ga. Const. 1868, Art. V I .............................................. 150

Ga. Const. 1877, Art. VIII, § 1 .................................... 151

Ga. Laws 1870, pp. 56-57 ..............................................56,151

Iowa Const. 1857, Art. I X ..........................................149,182

Iowa Laws 1865-66, p. 158 ..........................................149,182

111. Const. 1870, Art. VIII, § 1 ...................................... 174

111. Stats. 1858, p. 460 .......... ...................................... 173

Ind. Laws 1869, p. 4 1 ...................................... . 173

Xll

PAGE

XIII

Ind. Laws 1877, p. 1 2 4 ............. ................................. 173

Ind. Rev. Stats. (1843) ................................................ 172

Kan. Laws 1862, c. 46, Art. 4, §§ 3, 1 8 ....................... 179

Kan. Law 1864, c. 67, § 4 ............................................ 179

Kan. Law. 1865, e. 46, § 1 ............................................ 179

Kan. Laws 1867, c. 125, § 1 ...................................... 179

Kan. Laws 1874, c. 49 § 1 ............................................ 179

Kan. Laws 1876, p. 238 .............................................. 179

Kan. Laws 1879, c. 81, § 1 ............................................ 180

Kan. Gen. Stats., Art. V, § 75; c. 19, Art. Y, § 57, c. 92,

§ 1 (1868) ................................................................... 179

Kan. Stats., c. 72-1724 (1949) .................................... 2

Kan. Rev. Stats., § 21-2424 (1935) ............................... 179

Kan. Rev. Stats., § 27-1724 ...................................... 180

Ky. Const. 1891, § 187 ................................................ 184

Ky. Stats., c. 18 (1873) ................................................ 184

Ky. Stats., e. 18 (1881) .............................................. 184

Ky. Laws 1865-66, 38-39, 49-50, 68-69 ......................... 184

Ky. Laws 1869, c. 1634 ................................................. 184

Ky. Laws 1904, pp. 181-82............................................ 184

Ky. Laws 1869-70, pp. 113-127................................ 184

Ky. Laws 1871-72, c. 112 ............................................ 184

La. Acts 1869, p. 37 ..................................................... 149

La. Const. 1868, tit. VII, Art. 1 3 5 ............................. 147

La. Const. 1868, tit. I, Art. 2 ........................................ 147

La. Const. 1898, Art. 248 .............................................. 149

La. Laws 1871, pp. 208-10 ................................ ........ 149

La. Laws 1875, pp. 50-52 .............................................. 149

Mass. Acts 1845 ........................................................... 71

Mass. Acts & Res. 1854-55, c. 256, § 1, p, 650 ..........72,160

Mass. Acts & Res. 1864-65, pp. 674-75 ......................... 160

Mass. Acts & Res. 1867, pp. 789, 820 ..................... 161

Mass. Acts & Res. 1867, p. 787 ........... ......................... 162

Md. Laws 1865, c. 160, tit. i - iv .................................... 184

Md. Rev. Code, §§47, 60, 119 (1861-67 Supp.) .......... 184

Md. Laws 1868, c. 407 ................................................... 184

PAGE

XIV

Md. Laws 1870, c. 311 ........... ................................... 184

Md. Eev. Code, tit. xvii, §§ 95, 98 (1878)..................... 184

Md. Laws 1872, c. 377 .......................................... . 184

Mich. Acts 1867, Act. 34, § 2 8 .................................... 175

Mich. Acts 1869, Act 77, § 32 ................................... 175

Mich. Acts 1883, Act 23, p. 1 6 .................. 175

Mich. Acts 1885, Act 130, § 1 ................................... 175

Mich. Comp. Laws, H 7220, 11759 (1897) ................. 175

Mich. Const. 1835, Art II, § 1 .................................... 174

Mich. Const. 1850, Art VII, § 1, Art XVIII, $ 11 . . . . 174

Mich. Laws 42 (1867) .................................................... 175

Minn. Laws 1862, c. 1, § 33 ........................................ 180

Minn. Laws 1864, c. 4, § 1 ............................................ 180

Minn. Stats., c. 15, § 74 (1873) .................................... 180

Miss. Const. 1868, Art V I I I ........................................ 153

Miss. Const. 1890, Art IX, § 2 .............................. 155

Miss. Laws 1878, p. 103 .............................................56,155

Mo. Const. 1875, Art IX ............................................ 158

Mo. Laws 1864, p. 126................................................... 158

Mo. Laws 1868, p. 1 7 0 ................. 158

Mo. Laws 1869, p. 8 6 .................................................... 158

N. C. Const. 1868, Art. IX, §§ 2, 1 7 ............................. 145

N. C. Const. 1872, Art. IX, § 2 ...................................... 146

N. C. Laws 1867, c. LXXXIV, § 5 0 ............................. 146

N. C. Laws 1868-69 ....................................................... 146

Nebr. Comp. Laws 1855-65, pp. 92, 234, 560, 642,

(1886) ................. 178

2 Nebr. Comp. Laws 1866-77, pp. 351, 451, 453

(1887) ........................................................................178,179

Nev. Comp. Laws (1929) ............................................ 181

Nev. Laws 1864-65, p. 426 .............................................. 180

N. H. Const. 1792, § L X X X II I .................................... 163

N. J. Const. 1844, Art. IV, § 7(6) ............................... 167

N. J. Laws 1850, pp. 63-64 .......................... 167

N. J. Laws 1874, p. 135 ................................................ 168

N. J. Laws 1881, p. 1 8 6 ................................................ 168

PAGE

XV

N. J. Rev. Stats., c. 3 (1847) ........................................ 167

N. Mex. Stats. 1949, Mar. 17, c. 168, § 1 9 ................... 196

N. Y. Const. 1821, Art. V I I .......................................... 169

N. Y. Const. 1846, Art. I X ............................................ 169

N. Y. Const. 1868, Art. I X .................................... 169

N. Y. Laws 1850, c. 143................................................. 169

N. Y. Laws 1852, c. 291 .................. 169

N. Y. Laws 1864, c. 555 ................................................. 169

N. Y. Laws 1873, c. 186, §§ 1, 3 ...................... 170

Ohio Laws 1828-29, p. 7 3 ............................. ............. 171

Ohio Laws 1847-48, pp. 81-83...................................... 171

Ohio Laws 1848-49, pp. 17-18................. 171

Ohio Laws 1852, p. 441 ................................................. 171

Ohio Laws 1878, p. 513.................................................. 172

Ohio Laws 1887, p. 34 ............................... 172

Ore. Laws 1868, p. 114 .................................................. 181

Ore. Laws 1868, Joint Resolutions and Memorials 13 181

Pa. Laws 1854, No. 617, § 2 4 ........................................ 164

Pa. Const. 1873, Art X, § 1 ........................................ 166

Pa. Laws 1867, pp. 38-39, 1334 .................................... 166

Pa. Laws 1881, p. 76 ................................................... 166

R. I. Laws 1866, c. 609 .................................................. 160

S. C. Acts 1868-69, pp. 203-204 .................................... 148

S. C. Const. 1868, Art XX, 4, 1 0 ............................ 147

S. C. Const. 1868, Art I, § 7 ........................................ 147

S. C. Const. 1895, Art XI, § 5 ........................................ 27

S. C. Const. 1895, Art XI, §7 .................................... 4,149

S. C. Code, § 5377 (1942) ............................................ 4

S. C. Code, tit. 31, c. 122-23 (1935) ............................. 27

S. C. Code, tit. 31, c. 122, §§ 5321, 5323, 5325 (1935) .. 28

Tenn. Acts 1853-54, c. 81 ............................................ 155

Tenn. Acts 1865-66, cc. 15, 18, 40 ................................ 155

Tenn. Const. 1834 (As Amended, 1865) ...................... 155

PAGE

XVI

Term. Const. 1870, Art XI, § 1 2 ................................ 157

Tenn. Laws 1867, c. 27, § 1 7 ....................................... 157

Term. Laws 1870, c. 33, § 4 ........................................ 157

Tex. Const. 1871, Art I, § 1 ........................................ 151

Tex. Const. 1871, Art IX, §§1-4 ............................. 151

Tex. Const. 1876, Art VII, § 7 ................................. 152

6 Tex. Laws 1866-71, p. 288 ....................................... 152

8 Tex. Laws 1873-79, cc. CXX, § 5 4 ............................. 152

Ya. Acts 1869-70, c. 259, § 47 .............................. 153

Va. Const. 1868, Art VIII, § 3 .................................... 152

Va. Const. 1902, Art IX, § 1 4 0 ................................ 7, 8,153

Ya. Code, tit. 22, c. 12, Art 1, § 22-221 (1950) .......... 7, 8

Va. Laws 1831 .................................... ......................... 52

Vt. Const. 1777, c. II, § X X X I X ................................. 163

Vt. Const. 1786, c. II, § X X X V I I I ............................. 163

Vt. Const. 1793, c. II, § 41 ........................................ 163

Wis. Const. 1848, Art 10, § 3 ........................................ 176

Wis. Rev. Stats., tit. V II (1849) ............................. 176

W. Va. Const. 1872, Art XII, § 8 ................... . 158

W. Va. Laws 1865, p. 5 4 ................................................ 158

W. Va. Laws 1867, c. 9 8 ................................................ 158

W. Va. Laws 1871, p. 206 .............................................. 158

Debates, Records and Reports o f State Legislatures

and Constitutional Conventions

Alabama Constitutional Convention 1901, Official

Proceedings, vol. I, I I ................................................ 60

Ark. Sen. J., 17th Sess. 19-21 (1869)........................... 143

Biog. Dir. Am. Cong., H. R. Doc. No. 607, 81st Cong.

2nd Sess., 1229 (1950) .............................................. 226

Brevier Legislative Reports 44, 45, 79 (Ind. 1867) . . . 172

Brevier Legislative Reports 80, 88, 89, 90 ................ 173

Cal. Ass. J., 17th Sess. 611 (1867-68) ......................... 185

Cal. Sen. J., 17th Sess. 611, 676 (1867-68) .................. 185

Conn. House J. 410 (1866)....... 159

Conn. House J. 595 (1868)............................................ 159

PAGE

Conn. Sen. J. 374 (1866)................. .............................. 159

Conn. Sen. J. 247-48 (1868).......................................... 159

Debates of the California Constitutional Convention

of 1873 (1880) ........................................................... 185

Documents of the Convention of the State of New

York, 1867-68, Doc. No. 15 (1868) ...................... 170

Del. House J. 88 (1867)................................................ 183

Del. Sen. J. 76 (1867) ................................................... 183

Da. House J. 88, 307, 1065 (1870) ............................ 151,183

Ga. Sen. J., Pt. II 289 (1870) ...................................... 151

Iowa House J. 132 (1868) ............................................ 181

Iowa Sen. J. 265 (1868) ........................................... 181

111. House J. 40, 154 (1867) .......................................... 174

111. Sen. J. 40, 76 (1867).............................. ................ 174

Ind. Doc. J. Part I 21 (1867)........................................ 172

Ind. House J. 100-101 (1867) ...................................... 172

Ind. House J. 184 (1867) ............................................ 173

Ind. Sen. J. 79 (1867)................................................... 172

Journal of the Constitutional Convention of Georgia

151, 69, 479, 558, 1867-1868 ...................................... 150

Journal of the Louisiana Constitutional Convention

1898 ............................................................................. 60

Journal of the Mississippi Constitutional Convention

of 1890 ................................................................... 59,60,154

Journal of the Constitutional Convention of the State

of Illinois, Convened at Springfield, December 13,

1869 (1869) ............................................................ 174

Journal of the South Carolina Convention 1895 ........ 60

Journal of the Texas Constitutional Convention, 1875 56

Journal of the Virginia Constitutional Convention

1867-68 (1868) ..........................................................152,153

Journal of the Virginia Constitutional Convention

1901-1902 ..................................................................... 59

Kan. Sen. J. 43, 76,128 (1867)...................................... 179

Kan. House J. 62, 79 (1867) ........................................ 179

Ky. Sen. J. 63 (1867)..................................................... 184

Ky. House J. 60 (1867) ............................................... 184

xvii

PAGE

XV111

Mass. House Doc. No. 149, 23, 24, 25 (1867)............... 161

Mass. Leg. Doe., Sen. Doc. No. 25 (1867) ................... 162

Md. Sen. J. 808 (1867) .................................................. 183

Md. House J. 1141 (1867) ................. .......................... 183

Mich. House J. 181 (1867)............................................ 175

Mich. Sen. J. 125,162 (1867)........................................ 175

Minn. Exec. Doc. 25, 26 (1866) .................................. 180

Minn. House J. 26 (1866) ............................................ 180

Minn. Sen. J. 22, 23 (1866) .......................................... 180

Minutes of the Assembly 309, 743 (N. J. 1868).......... 168

Minutes of the Assembly, Extra Session 8 (N. J.

1866) .......................................................................... 167

Nebr. House J., 12th Terr. Sess. 99,105 (1867).......... 178

Nebr. House J. 148 (1867) .......................................... 178

Nebr. Sen. J. 174 (1867)................................................ 178

Nev. Ass. J. 25 (1867) ............... .................................. 180

Nev. Sen. J. 9, 47 (1867) .................................... . 180

N. H. House J. 137,174 (1866) ..................................... 162

N. H. House J. 176, 231-33 (1866) ............................... 163

N. H. Sen. J. 70, 94 (1866)............................................ 163

N. J. Sen. J. 198, 249, 356 (1868)................................ 168

N. J. Sen. J., Extra Sess. 14 (1866)............................. 167

N. Y. Ass. J. 13, 77 (1867) ........................................ 169

N. Y. Sen. J. 6, 33 (1867) .......................................... 169

Official Journal of the Constitutional Convention of

the State of Alabama 1867-1868, 237, 242 (1869) .. 149

Official Journal of the Proceedings for Framing a

Constitution for Louisiana, 1867-1868 (1868) . . . . 147

Ohio Exec. Doc. Part I 282 (1867) ............................. 171

Ohio House J. 13 (1867) ............................................ 171

Ohio Sen. J. 9 (1867) ................................................... 171

Ore. House J. 273 (1868) .......................................... 181

Ore. Sen. J. 25, 34-36 (1866) .................................... 181

Ore. Sen. J. 271-272 (1868) ........................................ 181

2 Pa. Leg. Rec. app, III, XVI, X X II (1867) . . . . . . 165

2 Pa. Leg. Rec. app. LXXXIV (1867)......... .............. 166

Pa. Sen. J. 16 (1867) ................................................. 164

PAGE

Pa. Sen. J. (1881) ....................................................... 167

Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Con

vention of the State of New York 1867-68 (1868) 169

Proceedings of the South Carolina Constitutional

Convention of 1868 Held at Charleston, S. C., Be

ginning January 14, and ending March 17, 1868,

654-900 (1868) ........................................................... 147

Report of the Proceedings and Debates of the Consti

tutional Convention, State of Virginia, Richmond,

June 12, 1901-June 26, 1902 (1906) ......................... 63

Report of Committee on Education, R. I. Pub. Doc.

No. 4 (1896) ............................................................... 160

Report of the Committee on Education, Mass. House

Doc. No. 167 (1855) .................................................73,160

2 Reports Made to the General Assembly at Its

Twenty-Fifth Session (111. 1866) ......................... 173

S. C. House J. Spec. Sess. 51 (1868) ......................... 148

Tenn. House J., called Sess. 24, 26, 38 (1866) .......... 156

Tenn. Sen. J. called Sess. 41, 42 (1866) ................. 156

Va. House J. 84 (1831-1832) .................................... 52

Vt. House J. 33, 139 (1866) ........................................ 164

Vt. Sen. J. 28, 75 (1866) .............................................. 164

Wis. Ass. J. 618 (1863) .............................................. 176

Wis. Ass. J. 96, 98, 32, 33, 224-226, 393 (1867).......... 176

Wis. House J. 33 (1867) ............................................ 176

Wis. Sen. J. 119, 149 (1867) ...................................... 176

Congressional Debates and Reports

3 Cong. Deb. 555 (1826)................................................ 210

Cong. Globe, 34th Cong., 1st Sess. App. (1856) 124,

295-296, 553-557, 644 ..................................................... 229

Cong. Globe, 34th Cong., 3rd Sess. App. 135-140

(1857) ............................ 230

Cong. Globe, 35th Cong., 1st Sess. 402 (1858) .......... 230

Cong. Globe, 35th Cong., 2nd Sess. 981-985 (1859) . . . 234

xix

PAGE

XX

PAGE

77

77

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess. 1639 (1862)

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess. 1642 (1862)

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. (1864):

553, 817 ................................................................... 78

1156......................................................................... 98

1158 .............................................. 78

3132, 3133 ................................................................ 78

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865-66):

2 ............................................................................... 7,80

39-40 ...................................................... 79

69.. ............................. 81

74 ............................................................................ 94

75 ............................................................................ 94

183 ........................................................................... 88

217............................................................................ 142

240 ......................................... 118

372 .......................................................................... 99

474 .......................................................................... 83

475 ............................................................................83,210

500 ff.......................................................................... 84

500 .......................................................................... 84

504 .......................................................................... 85

541............................................................................ 82

570 ..................................................... 85

630 ........................................................................... 87

813............................................................................ 104

1063 ................................................... 94

1121 ................................................................ . . . . 86,102

1171 ......................................................................... 86

1270 ........................................................................ 218

1291.......................................................................... 87

1291, 1293, 2461-2462 ............................................ 99

1294 ................. 87

1835 .......................................................................... 89

1836 ........................................................................ 89

XX I

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.:

2459, 2462, 2498, 2506, 2896 .................................108,113

2459, 2462, 2498, 2502 ............................................ 112

2455 ............................................................ 114

2537 ......................................................................... 113

2766 ......................................................................... 115

2940 ............................................... 116

2961 ................................................. 116

2896 ........................................................................ 97

3148 ......................................................................... 94

4275-4276 .................................... 101

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. App. (1866):

71 ............................................................................. 82

134 .......................................................................... 103,105

1094 ........................................................................ 106

1095 ............................................................ 106

2538 ........................................................................ 103

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess. 472 (1867).......... 141

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 1st Sess. 2462 (1868).......... 97

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess. 2748 (1868) . . . .100,101

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1871):

244 .......................................................................... 127

384 .......................................................................... 127

760, 764 ................................................................. 127,128

913, 919, 929 ..........................................................128,129

1582 ........................................................................ 129

3181 ....................................................... 129

3189, 3190 ............................................................... 130

3191, 3192............................................................... 131

3195 ........................................................................ 130

3256 ........................................................................ 130

3258 ........................................................................ 130

3264-65 ................................................................... 131

3266 ......................................................................... 131

3268 ......................................................................... 131

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1871):

3270

PAGE

131

XXII

2 Cong. Rec. (1873-74):

318 .................................................... 132

412 ff............................................... 133

2, 383 ff................................................................... 134

3451-3455, 4116, 4173 .............................................. 135

4089, 4154, 4159, 4167 ............................................ 137

4151, 4153-54 ......................................................... 136

4171, 4176 ...................................... 138

4167 ................................ 100

5 Cong. Rec. 979, 980 (1875)...................................... 139

H. R. Rep. No. 691, 24th Cong., 1st Sess. (1836)....... 211

H. R. Rep. No. 80, 27th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1843)....... 210

Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. Pt. IY, 135 (1866) ................. 123

Other Authorities

Address of the Conservative Members of the Late

State Convention to the Voters of Virginia (1868) 153

Annual Proceedings and Reports, American Anti-

Slavery Society, Vols. 1-6 (1833-1839) ....206,207,213

Annual Report of the State Superintendent of Schools

(N. J. 1868) .............................................................. 167

Annual Report of the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction (N. Y. 1866) ........................................ 169

Barnes, The Anti-Slavery Impulse, 1830-1844 (1933)

205, 211, 221

Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen (unpub. ms., pub. ex

pected in Dec. 1953) ................................................ 159

Becker, The Declaration of Independence (1926) . . . . 201

Birney, James Gr., Birney and His Times (1890) . . . . 205

Birney, James G., Narrative of the Late Riotous

Proceedings Against the Liberty of the Press in

Cincinnatti (1836) .................................................... 213

Blose and Jaracz, Biennial Survey of Education in the

United States (1949-50) (1952) ........................... 64

Boston Daily Advertiser, January 5, 1867 ................. 161

PAGE

XX111

Boston Daily Advertiser, March 12, 1867; March 14,

1867; March 21, 1867 ................................................ 162

Boudin, Truth and Fiction About the Fourteenth

Amendment, 16 N. Y. U. L. Q. Rev. (1938) ..........93, 200

Bowers, The Tragic Era (1929) .................................94,100

3 Brennan, Biographical Encyclopedia of Ohio (1884) 227

Brownlee, New Day Ascending (1946) ..................... 55

Bruce, The Plantation Negro as a Free Man: Obser

vations on his Character, Conditions, and Prospects

in Virginia (1889) ........................................................ 60

Burgess, The Middle Period (1897) ........................... 210

Cable, The Negro Question (1890) ............................. 55

Calhoun, The Works of John C. Calhoun (Cralle ed.

1854-1855) ................................................. 203

Carleton, The Conservative South—A Political Myth,

22 Va. Q. Rev. 179 (1946) ........................................ 62

Carroll, The Negro A Beast (1908) ............................. 60

Carroll, The Tempter of Eve, or the Criminality of

Man’s Social, Political and Religious Equality With

the Negro, and the Amalgamation to Which These

Crimes Inevitably Lead (1902) ................................. 60

Cartwright, Diseases and Peculiarities of the Negro

Race, 11 DeBow’s Rev. 64 (1851) ......................... 51

Cartwright, Diseases and Peculiarities of the Negro

Race, 2 DeBow, The Industrial Resources, etc., of

the Southern and Western States (1852) ............. 51

Cartwright, Essays, Being Inductions Drawn From

the Baconian Philosophy Proving the Truth of the

Bible and the Justice and Benevolence of the

Decree Dooming Canaan to be a Servant of Serv

ants (1843) ............................................................... 51

Chadbourne, A History of Education in Maine (1936) 160

Channing, History of the United States (1921) . . . . 52

Charleston Daily News, July 10, 1868 .................... 148

Charlotte Western Democrat, March 24, 1868; April

17, 1868 ...................................................................... 146

PAGE

XXIV

Chase, Speech in the Case of the Colored Woman,

Matilda Who Was Brought Before the Court of

Common Pleas of Hamilton Co., Ohio, by Writ of

Habeas Corpus, March 11, 1837 (1837) . . . . . . . . 206

Christensen, The Grand Old Man of Oregon: The Life

of George H. Williams (1939) ................................ 96

Cloud, Education in California (1952) ..................... 185

Comment, A New Trend in Private Colleges, 6 New

South 1 (1951) ........................................................... 49

Comment, Some Progress in Ehmination of Discrimi

nation in Higher Education, 19 J. Neg. Ed. 4 (1950) 49

Comment, The Courts and Racial Integration in Edu

cation, 21 J. Neg. Ed. 3 (1952) ............................. 49

Comment, 22 J. Neg. Ed. 95 (1953)............................. 193

Commercial, March 30, 1866 ........................................ 89

Conkling, Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling (1869) 100

Corwin, National Power and State Interposition 1787-

1861, 10 Mich. L. Rev. 535 (1912) ......................... 211

Corwin, The ‘ Higher Law’ Background of American

Constitutional Law, 42 Harv. L. Rev. 149, 365

(1928).......................................................................... 201

Coulter, The South During Reconstruction (1947) 54

Craven, The Coming of the Civil War (1943).......... 212

2 Crosskey, Politics and the Constitution in the His

tory of the United States (1953)............................ 200

Cubberly, A Brief History of Education (1920) . . . . 120

Cubberly, Public Education in the United States

(1919) .......................................................................... 122

Dabney, Universal Education in the South (1936) 148,153

Daily Arkansas Gazette, March 15, 1868, March 19,

1868, April 2, 1868 .................................................... 143

Daily Arksanas Gazette, April 10, 1868 ................... . 144

Daily State Journal, February 20, 1870 ................ 151

Daily Wisconsin Union, February 7, 1867 ................ 177

DeBow, The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-

Slaveholder (1860) ................................................... 123

Des Moines Iowa State Register, January 29, 1868;

February 19, 1868 ................................................... 182

PAGE

XXV

Dew, Review of the Debates in the Virginia Legisla

ture of 1831-32, The Pro-Slavery Argument 442

(1853).......................................................................... 52

Diary and Correspondence of Salmon P. Chase, 2

Ann. Rep. Am. Hist. Assn. 188 (1902) ................. 73

1 Diet. Am. Biog 389 (1928) .................................... 227

2 Diet. Am. Biog. 278 (1929) .................................... 99

2 Diet. Am. Biog. 374 (1929) .................................... 226

2 Diet. Am. Biog. 489 (1929) ................................... 227

6 Diet. Am. Biog. 348 (1931) ................................... 227

6 Diet. Am. Biog. 349 (1931) ...................................... 95

7 Diet. Am. Biog. 631 (1931) ...................................... 95

7 Diet. Am. Biog. 632 (1931) .................................... 95

7 Diet. Am. Biog. 260 (1931) ...................................... 226

8 Diet. Am. Biog. 310 (1932) .................................. 96

10 Diet. Am. Biog. 113 (1933)..................................... 98

11 Diet. Am. Biog. 52 (1933) .................................... 133, 227

11 Diet. Am. Biog. 389 1933) .................................... 227

12 Diet. Am. Biog. 240 (1933) .................................... 226

13 Diet. Am. Biog. 198 (1934) ................................ 227

17 Diet. Am. Biog. 620 (1935) .............. ............ ............ . 226

17 Diet. Am. Biog. 270 (1935) .................................... 226

18 Diet. Am. Biog. 208 (1936) .................................... 227

19 Diet. Am. Biog. 303 (1936) .................................... 226

19 Diet. Am. Biog. 504 (1936) .................................... 102

20 Diet. Am. Biog. 322 (1936) .................................... 227

Dubuque Weekly Herald, January 30, 1867 ............. 182

Dumond, The Antislavery Origins of the Civil War

(1938) ....................................................................... 212,221

Eaton, Special Report to the United States Commis

sioner of Education, Report of the U. S. Commr.

of Educ. to the Secy, of the Int. (1871) ................. 144

Eaton, Freedom of Thought in the Old South (1940) 211

Edwards and Richey, The School in the American

Social Order (1947) ........................................*.. .121,122

Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incorpo

rate the Bill of Rights ? The Original Understand

ing, 2 Stan. L. Rev. 5 (1949)

PAGE

200

XXY1

Fay, The History of Education in Louisiana, U. S.

Bureau of Education, Circular No. 1 (1898) ........ 149

Fayetteville News, April 14, 1868; June 2, 1868 . . . . 146

2 Fessenden, Life and Public Services of William. Pitt

Fessenden (1931) .................................................... 95

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1908) .................................................................. 90,138,185

Flake’s Daily Bulletin, March 3,1870; March 13,1870 152

Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction,

1865-1906 (1906) ........................................... 79

Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding of

“ Equal Protection of the Laws” , 50 Col. L. Rev.

131 (1950) .................................................93,96,97,98,99,

100, 101, 200

Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of

American Negroes (1947) .................................... 51

Franklin, The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-

1860 (1943) .......................... 52

Franklin, The Enslavement of Free Negroes in North

Carolina, 29 J. Neg. Hist. 401 (1944) ................. 52

Garner, Reconstruction in Mississippi (1901) .......... 154

Goodell, View of American Constitutional Law in Its

Bearing Upon American Slavery (1844) ............... 221

Graham, The “ Conspiracy Theory” of the Four

teenth Amendment:

47 Yale L. J. 371 (1938)........................................ 99, 200

48 Yale L. J. 171 (1938)....................................... 200

Graham, The Early Antislavery Backgrounds of the

Fourteenth Amendment, 1950 Wis. L. Rev. 479,

610 ......................................................... 99,199,201,202,203

213, 214, 218, 228

Greene and Woodson, The Negro Wage Earner

(1930) ......................................................................... 52

Greensboro Times, April 2, 1868; April 16, 1868 ____ 146

Hamer, Great Britain, The United States and the

Negro Seaman Acts, 1822-1848, 1 J. So. Hist. 1

(1935) ................................................................. 210

Hamilton, Property According to Locke, 41 Yale

L. J. 864 (1932)

PAGE

201

XXY11

Harper’s Memoir on Slavery, The Pro-Slavery

Argument 26-98 (1835) ............................................ 51

Helper, The Impending Crisis of the South (1863).. 53

Herbert, et ah, Why the Solid South? Or Recon

struction and Its Results (1890) ............................. 60

Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old South

(1935) ...............................................................51,52,53,211

Johnson, The Ideology of White Supremacy, 1876-

1910 in Essays in Southern History Presented to

Joseph Gregoire deRoulhae Hamilton 124 (Green

ed. 1949) ...................................................... 50,51,59,61,64

Johnson, The Negro in American Civilization

(1930) ...................................................................... 51,53,54

Jordan, Official Convention Manual (1874)................. 167

Julian, The Life of Joshua R. Giddings (1892)........... 224

Kelly and Harbison, The American Constitution, Its

Origin and Development (1948)............................... 93

Kendrick, Journal of the Joint Committee of Fifteen

on Reconstruction (1914) ............... 92, 95, 96, 97, 99,101,

102,107,109, 200, 225

Kennebec Journal, January 22,1867 ................... 160

Key, Southern Politics in the State and Nation (1949) 58

Kirwan, Revolt of the Rednecks (1951)................. 59, 60, 63

Knapp, New Jersey Politics During the Period of

Civil War and Reconstruction (1924)..................... 168

Knight, Influence of Reconstruction on Education

(1913) ........................................................................ 145

Knight, Public Education in the South (1922)..........55,144

Lee and Kramer, Racial Inclusion in Church-Related

Colleges in the South, 22 J. Neg. Ed. 22 (1953) . . . 49

Letters of James G. Birney, 1831-1857, 2 Yols.

(Dumond, ed. 1938) .........................................205,213,214,

221, 226

Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimke

Weld and Sarah Grimke (1822-1844), 2 Yols.

(Barnes and Dumond eds. 1934)................... 205, 207, 211,

220, 226, 227

Lewellen, Political Ideas of James W. Grimes, 42

Iowa Hist. & Pol. 339 (1944)

PAGE

95

XXV111

Lewinson, Bace, Class and Party (1932)................... 62

Locke, Second Treatise on Government (1698)........ 201

Logan, The Negro in American Life and Thought:

The Nadir 1877-1901 (To be published by the Dial

Press early in 1954) ..................... ......................... 61

McCarron, Trial of Prudence Crandall, 12 Conn.

Mag. 225 (1908) ........................................ 208

McLaughlin, Constitutional History of the United

States (1935) ........................................................... 210

McLaughlin, The Court, The Corporation and Conk-

ling, 46 Am. Hist. Bev. 45 (1940) ..................... .. 200

McPherson, Political History of United States Dur

ing Beconstruction (1880) .................................... 79

McPherson’s Scrapbook, The Civil Eights B il l .......... 89

Mellen, An Argument on the Unconstitutionality of

Slavery (1841) ........................................................... 221

Messages and Proclamation of the Governors of

Nebraska, collected in Publications of the Nebraska

Historical Society (1942) ........... 178

Moon, The Balance of Power—The Negro Vote (1948) 62

2 Moore, Digest of International Law 358 (1906) .. 220

Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massa

chusetts (1866) ........................................................ 202,203

Morse, The Development of Free Schools in the

United States as Illustrated by Connecticut and

Michigan (1918) ....................................................... 159

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) ................. 203

Nashville Dispatch, July 12,1866 ................................ 156

Nashville Dispatch, July 25, 1866 ............................. 157

Nason, Life and Public Services of Henry Wilson

(1876) ........................................................................ 71

National Intelligencer, April 16, 1866; May 16, 1866 89

Nebraska City News, August 26, 1867; September 4,

1867 .............................................................................. 178

Nevins, The Ordeal of the Union (1949) ............... 212,221

Newark Daily Advertiser, October 25, 1866 ............... 168

New Haven Evening Begister, June 17, 1868 .......... 159

PAGE

XXIX

89

193

PAGE

N. Y. Herald, March 29, 1866; April 10, 1866 ..........

New York Times, August 19, 1953 .............................

Noble, A History of Public Schools in North Carolina

(1930) ..................................................................... 145,146

Note, 56 Harv. L. Rev. 1313 (1943) ........................... 196

Note, Grade School Segregation: The Latest Attack

on Racial Discrimination, 61 Yale L. J. 730 (1951) 194

Nott, Two Lectures on the Natural History of the

Caucasian and Negro Races (1866) ..................... 51

Nye, Fettered Freedom (1949) ........... .. .204, 208, 212, 221

Ohio Antislavery Society, Anniversary Proc., Vols.

1-5 (1836-1840) ......................................................... 206

Olcott, Two Lectures on the Subject of Slavery and

Abolition (1838) ....................................................... 206

Omaha Weekly Republican, January 25,1867; Febru

ary 8,1.867 ............................................... 178

Oregonian, The, September 14, 1866; September 21,

1866 ............................................................................ 181

Orr, History of Education in Georgia (1950) ........150,151

Our National Charters (Goodell ed. 1863) ............. 222

Page, The Negro: The Southerners’ Problem (1904) 60

Philanthropist, January 13, 1837; January 20, 1837;

January 27, 1837; March 10, 1837 .........................216, 217

Phillips, American Negro Slavery, Documentary His

tory of American Industrial Society-Plantation

and Frontier Documents (1910) ............................. 53

Porter, A History of Suffrage in the United States

(1918) ........................................................................ 52

Pound, Appellate Procedure in Civil Cases (1941) .. 196

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Higher

Education For American Democracy (1947) ___ 196

Proceedings of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Convention

Held at Putnam, April 22-24,1835 (1835).............. 209

Pro-Slavery Argument, as Maintained by the Most

Distinguished Writers of the Southern States

(1853) 203

Randle, Characteristics of the Southern Negro (1910) 60

Report of the Arguments of Counsel in the Case of

Prudence Crandall, Plff. in error vs. State of Con

necticut, Before the Supreme Court of Errors, at

Their Session at Brooklyn, July Term 1834 .......... 208

Report of the Indiana Department of Public Instruc

tion (1867-68) ........................................................... 163

Report of the United States Commissioner of Educa

tion, 1867-68 (1868).................................................... 156

Reynolds, Portland Public Schools, 1875, 33 Ore.

Hist. Q. 344 (1932) ............................................... 181

Richmond Enquirer, March 31,1868 ............................ 152

Rowland, A Mississippi View of Relations in the

South, A Paper Read Before the Alumni Associa

tion of the University of Mississippi, June 3, 1902

(1903) ......................................................................... 60

Salter, Life of James W. Grimes (1876)..................... 95

Sewell, The Selling of Joseph (1700)........................... 202

Schaff'ter, The Iowa “ Civil Rights A ct” , 14 Iowa L.

Rev. 63 (1928) ........................................................... 182

Shugg, Negro Voting in the Ante-Bellum South, 21

J. Neg. Hist. 357 (1936) .......................................... 52

Simkins, Pitchfork Ben Tillman (1944) .......................59, 60

Simkins, The Tillman Movement in South Carolina

(1926) ........................................................................ 53

Simms, “ The Morals of Slavery” , The Pro-Slavery

Argument (1835) ...................................................... 51

Sixth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public

Instructions of the State of Illinois, 1865-66 ___ 173

Smith, Appeals of the Privy Council From American

Plantations (1950) .................................................... 196

Smith, The Liberty and Free Soil Parties in the

Northwest (1897) ........................................... .....223 ,224

Spain, The Political Theory of John C. Calhoun

(1951) 203

Special Report of the Commissioner of Education,

Legal Status of the Colored Population in Respect

to Schools and Education (1871)............................. 176

x x x

PAGE

XXXI

Stanwood, History of the Presidency (1904) .. .223, 224, 225

Staples, Reconstruction in Arkansas (1923).............. 143

State Documents on Federal Relations: The States

and the United States (Ames ed. 1904) ................. 210

Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law

(1910) .......................................................................... 56

Stiener, History of Slavery in Connecticut (1893).. 208

Stone, Studies in the American Race Problem (1908) 60

2 Sumner, Work of Charles Sumner (1875)............... 71

Sydnor, Development of Southern Sectionalism 1819-

1848 (1948) ....................................................... 211

tenRroek, The Antislavery Origins of the Fourteenth

Amendment (1951) .................................... .68, 76, 200, 222

Thomas, Theodore Weld (1950) ................................ 205

2 Thorpe, The Federal and State Constitutions,

Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws

(1909) ........................................................................ 150,203

Tiffany, A Treatise on the ITnconstitutionality of

American Slavery (1849) ........................................ 221

Trenton Daily True American, November 3, 1866 . . . 168

Trenton State Gazette, November 3, 1866 ................. 168

Tuckerman, William Jay and the Constitutional

Movement for the Abolition of Slavery (1893) . . . . 210

Yance, Human Factors in Cotton Culture (1926) . . . 53