Moorer v. South Carolina Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 9, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moorer v. South Carolina Brief for Appellees, 1966. 065198ae-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/15f73ae1-622f-4345-9aed-8253170c2602/moorer-v-south-carolina-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

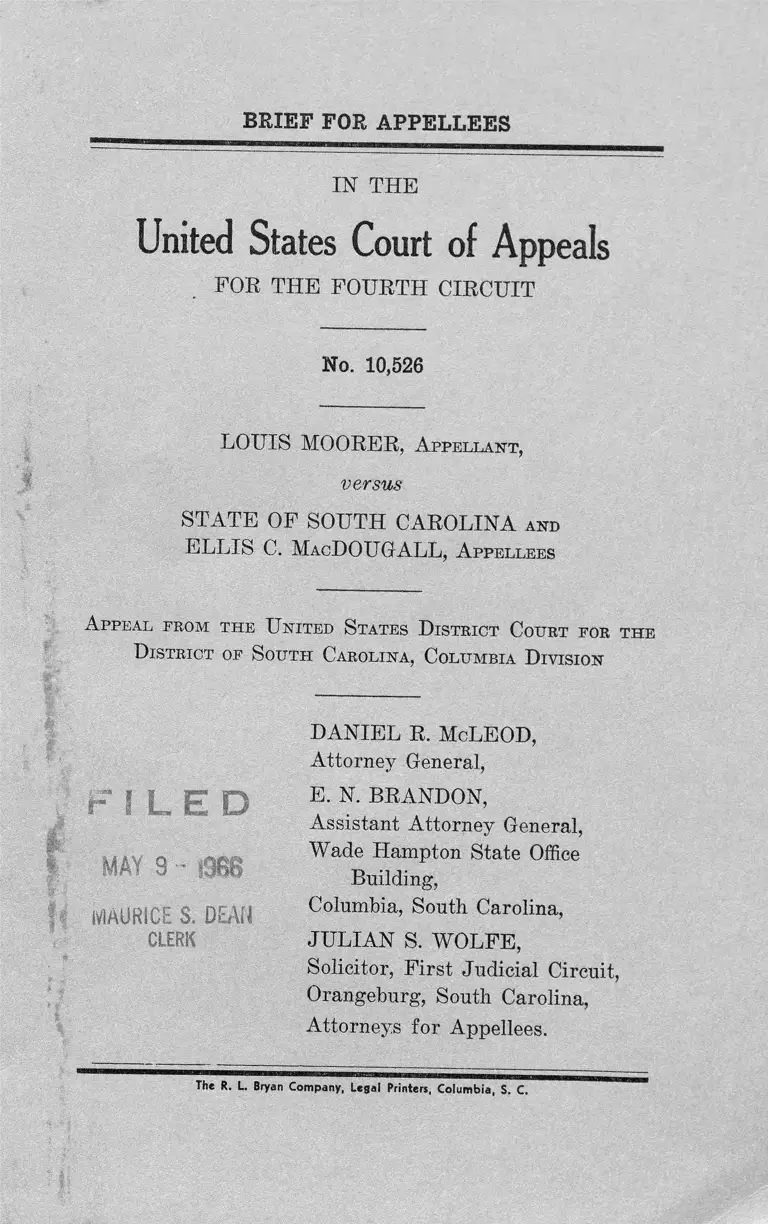

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 10,526

LOUIS MOORER, Appellant,

versus

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and

ELLIS C. MagDOUGALL, Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

District of South Carolina, Columbia Division

DANIEL R. McLEOD,

Attorney General,

r I L E D E. N. BRANDON,

Assistant Attorney General,

MAY 9 - (966

Wade Hampton State Office

Building,

M A U R IC E S. D E A N

Columbia, South Carolina,

CLERK JULIAN S. WOLFE,

Solicitor, First Judicial Circuit,

Orangeburg, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellees.

The R. L. Bryan Company, Legal Printers, Columbia, S. C.

INDEX

P age

Statement of the C ase.................................................. 1

Questions Presented ...................................................... 3

Argument:

I. The district court committed no error in re

fusing to admit into evidence certain statistics

gathered by appellant concerning the commission

of crimes by others, as such statistics were totally

irrelevant to any issue raised by this appeal......... 3

II. The district court committed no error in

finding that the death penalty for rape does not

constitute cruel and unusual punishment.............. 6

III. The district court properly denied appel

lant relief on the ground that certain alleged prej

udicial testimony was adduced in the trial court

concerning a statement made by appellant, where

such statement was not admitted into evidence and

its voluntariness was not ruled upon...................... 7

Conclusion ..................................................................... 10

( i )

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOE THE FOTTETH CIRCUIT

No. 10,526

LOUIS MOORE E, Appellant,

versus

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and

ELLIS C. MacDOUGALL, Appellees

Appeal prom the United States District Court for the

District of South Carolina, Columbia Division

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellant was convicted of rape on April 4, 1962, in

the Court of General Sessions for Dorchester County and

sentenced to death. The Supreme Court of South Carolina

affirmed the conviction on January 21, 1963, reported as

State v. Moorer, 241 S. C. 487, 129 S. E. (2d) 330. Appel

lant served notice of intention to petition the Supreme

Court of the United States for a Writ of Certiorari and

was granted a stay of execution to perfect this petition.

Instead of perfecting the petition for a Writ of Certiorari,

appellant abandoned his appeal to the United States Su

preme Court and filed a petition for a Writ of Habeas

Corpus on May 14, 1963. This petition was denied after a

full hearing on May 17,, 1963, and appellant served notice

of appeal to the Supreme Court of South Carolina. At a

subsequent hearing to settle the record on appeal, the pre

siding judge, with the consent of all parties, directed that

another hearing be held to determine if appellant had been

given a preliminary hearing prior to tins trial, since he had

attempted to incorporate certain exceptions relating to a

preliminary hearing. This supplemental hearing was held

on August 30, 1963, following which the presiding judge

issued an order holding that appellant had established no

further grounds for the issuance of a Writ of Habeas

Corpus. Appellant’s appeal from both orders to the Su

preme Court of South Carolina resulted in the affirmance

thereof on March 30, 1964. Moorer v. State, 244 S. C. 102,

135 S. E. (2d) 713, Certiorari denied 379 U. S. 860.

Appellant tiled a petition for writ of habeas corpus

and stay of execution in United States District Court on

November 30, 1964, which stay was granted December 1,

1964. Appellant filed an amended petition on March 10,

1965, requesting the stay be continued while he returned

to the state court. This request was granted on March 12,

1965, but jurisdiction was relinquished and the stay vacated

on April 13, 1965. The Supreme Court of South Carolina

denied appellant’s application for a stay and overruled

all his contentions of error in a well considered order on

May 11, 1965. Moorer v. MacDougall, 245 S. C. 633, 142

S. E. (2d) 46.

Thereafter appellant returned to the district court, but

his petition was overruled and a stay denied. On May 13,

1965, Chief Judge Haynsworth issued a stay of execution

pending appeal. On June 23, 1965, the Court of Appeals

vacated and remanded the judgment of the district court

for a hearing and a review of the state decisions. Moorer

2 Moorer, Appellant, v. State of S. C. et al., Appellees

v. State of South Carolina, 347 F. (2d) 502. The district

court denied relief to appellant on January 3, 1966.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether the district court committed error in re

fusing to admit into evidence certain statistics gathered by

appellant concerning the commission of crimes by others.

II. Whether the district court committed error in find

ing that the death penalty for rape does not constitute cruel

and unusual punishment.

III. Whether the district court properly denied ap

pellant relief on the ground that certain testimony was ad

duced in the trial court concerning a statement made by

appellant, where such statement was not admitted into evi

dence, and its voluntariness was not ruled upon.

ARGUMENT

I

The District Court Committed No Error in Refusing

to admit Into Evidence Certain Statistics Gathered by Ap

pellant Concerning the Commission of Crimes by Others, as

Such Statistics Were Totally Irrelevant to any Issue Raised

by this Appeal.

Appellees will use the designation of appellant in cit

ing from the various proceedings. The transcript of trial

proceedings in the Court of General Sessions for Dorches

ter County will be cited as S.C.T..........The transcript of

habeas corpus proceedings in the Court of Common Pleas

for Richland County will be cited as S.C.H......... The tran

script of the habeas corpus proceeding on August 18, 1965,

in the United States District Court will be cited as U.S. . . .

Judge Hemphill, in his order denying appellant relief

(U.S. 49), refused to admit the proffered statistics on the

Moorer, Appellant, v. State of S. C. et al., Appellees 3

grounds that they were hearsay, which they clearly were

and also on the ground that they were “not proper to the

cause”. This was a clear ruling that suchjp*nffered statis

tics were irrelevant. If they are irrelevant, and appellees

submit that they are, then they arU-Tmt- adin issible, no mat

ter how reliable they may be and no matter whether they

might be admissible as an exception to the hearsay rule.

The point raised here is really very simple, and should

be simply treated. Under South Carolina law a defendant

has absolutely no right to mercy in a rape case. State v.

Worthy, 239 S. C. 449, 123 S. E. (2d) 835. It is purely a

matter of grace which may be extended by the jury for any

reason or for no reason at all. This was properly charged

by Judge Griffith at the trial (S.C.T. 86). In order to de

termine why mercy was or was not recommended it would

be necessary to interrogate the members of the jury. This

cannot be inquired into, as it would destroy the inviolabil

ity of the jury room. The Supreme Court of South Caro

lina clearly recognized this and so stated in Moorer v. Mac-

Dougall, 245 S. C. 633, 142 S. E. (2d) 46.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit in Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F. (2d) 325, cert, denied

382 U.S. 944, 15 L. Ed. (2d) 353, cuts to the heart of this

matter. It recognizes that appellant’s theory, if followed

to its ultimate conclusion, would make the prosecution of a

Negro for rape impossible, and would effect discrimination ft'

in reverse. It is a legal merry-go-round without substance, i/*

Suppose appellant were to prevail under this theory and

the prosecution of Negro rapists no longer was allowed.

Could not then a white man argue that the law was being

discriminatorily enforced against him and he could not be

prosecuted!

The Supreme Court of the United States denied cer

tiorari in Swam v. Alabama at the same time it denied cer-

4 Moorer, Appellant, v . State op S. C. et al., Appellees

5

ftiorari in Maxwell. On March 29, 1966, it denied certiorari

in Craig v. Florida, 179 So. (2d) 202, 34 Law Week 3332.

Maxwell, Swain, and Craig involved substantially the same

contentions advanced by appellant. With three denials of

certiorari in the same term, it would appear that the Su

preme Court looks with scant favor on such contentions.

, £ j M qoeee, A ppellant, v. State of S. C. et a l, A ppellees

Appellant’s contention was before the Supreme Court

of Florida many years before Craig. State ex rel. Johnson

v. Mayo, 69 So. (2d) 307; State ex rel. Copeland v. Mayo,

87 So. (2d) 501; Thomas v. State, 92 So. (2d) 621. ̂In

Thomas that court remarked that such statistics, if they

show anything, show that more Negroes have been tried

and convicted for rape than have white defendants.

“■’~EvCTdnWaHeB'~wlre're’discriminatory selection of juries

can be shown in prior years a present conviction is not

nullified if the current selection is proper. Brown v. Allen,

344 U.S. 443, 97 L. Ed. 469.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 30 L. Ed. 220, and

cases of similar import cited by appellant, are not appli

cable here. No contention has been made that the law

against commiting rape is not enforced equally against all

rapists. If the police arrested only Negro rapists the situa

tion would be comparable to Yick Wo v. Hopkins. Appellant

is attempting to inquire into why a jury takes a certain

action in a case or cases which have no bearing on his own

case. No inquiry can be directed thereabout.

A defendant is entitled to non-discriminatory selection

of jurors. After he gets that, he can’t delve into their

actions. Each case stands on its own.

This case is not unlike those cases in which one Negro has

killed another Negro. It is common knowledge that in many

such cases the defendant has gotten off lighter than he

should have. Under appellant’s theory, could it not be

said that the first Negro to receive the death penalty for

killing another Negro has been discriminated against?

6 M oorer, A ppellant, v . State of S. C. et al., A ppellees

II

The District Court Committed No Error In Finding

That The Death Penalty For Rape Does Not Constitute

Cruel And Unusual Punishment.

This contention was made in Maxwell, Swain, and

Craig, supra, and the Supreme Court of the United States

denied certiorari in all three instances. As is well known,

the court first rejected the contention in Rudolph v. Ala

bama, 375 U. S. 889, 11 L. Ed. (2d) 119. As is equally well

known, this court in Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F. (2d) 128,

certiorari denied 380 IT. S. 925, also rejected such conten

tion.

/ Appellant concedes that the death penalty for rape,

under the decisions, does not constitute cruel and unusual

punishment in those jurisdictions where no provision is

made for the jury to recommend the defendant to the mercy

of the court. How then could it constitute cruel and unusual

punishment in thise jurisdictions which permit the jury to

recommend mercy, and thereupon impose a lesser judg

ment ? Which jurisdiction is more favorable to a defendant ?

It is difficult to see how anything could be fairer than to

allow the jury to recommend mercy in its discretion. State

v. Worthy, supra.At is impossible to j ->ee how a stra ight

rape caideath penalty for rape can becmisSEjiiQiiflllv ptyrmissihlo

and a provision for mercy impermissible, j

A defendant has no right to mercy, as is stated in

Worthy. Consequently he has no right to present evidence

which would warrant mercy. There is thus no conflict be

tween such claimed right and his Fifth Amendment right

not to incriminate himself. By way of illustration, however,

there is no bar to asserting matters meriting mercy through

non-incriminatory witnesses. Appellant here sought to do

so by having his grandmother testify that appellant did

not act normal and was a slow learner. S. C. T. 38-41

The matter for the jury’s consideration is really very

simple. They must decide if the defendant is guilty or

innocent, and if they decide that he is guilty they must de

cide whether or not to recommend mercy. All they need to

make these decisions can be placed before them during the

trial. The amount of force used and the physical harm

done to the victim is inescapably brought out.

It is only when mercy is recommended that a serious

inquiry into circumstances of mitigation or aggravation is

necessary. At that time the defendant and the State can

offer such circumstances as they wish. State v. Kimbrough,

212 S. C. 348, 46 S. E. (2d) 273. The court can then sentence

the defendant within the limits of the statute.

I l l

The District Court properly denied appellant relief on

the ground that certain alleged prejudicial testimony was

adduced in the trial court concerning a statement made by

appellant, where such statement was not admitted into evi

dence and its voluntariness was not ruled upon.

Appellant’s contention that testimony that he had made

a voluntary statement soon after his arrest was prejudicial

because it strongly suggested that he had voluntarily con

fessed is without factual support. Two witnesses, the sheriff

and a deputy, testified that a statement was given. S.C.T.

30-34. There is not the slightest indication that the state

ment was either incriminatory or exculpatory. It was not

Admitted into evidence and did not become an issue in

the case.

Appellant was represented by able counsel at his trial,

'..-and no request for an instruction to disregard any refer-

Moorer, Appellant, v. State of S. C. et al., Appellees 7

8 M oorer, A ppellant, v . State of S. C. et a l, A ppellees

ence to a statement was made, and no motion for a mistrial

was made. Appellant did not object to questions about the

statement on the ground that it was not voluntary. The only

testimony was to the effect that it was voluntary; there

was no testimony as to its contents.

In State v. Robinson, 238 S. C. 140, 119 S. E. (2d) 671,

testimony was elicited concerning a voluntary confession;

later the State, after objection, withdrew the tendered ex

hibit. The trial judge instructed the jury to disregard the

statement. A new trial was denied and the Supreme Court

of South Carolina affirmed.

Appellant here was represented by able counsel in his

petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the Eichland County

Court of Common Pleas. Moorer v. State, 244 S. C. 102,

135 S. E. (2d) 713, certiorari denied, 379 U. S. 860. This

contention could tan^^een made there but was not, and

jfc Tm <mm+ion, the Supreme Court

it searched the record in

appellant’s original appeal and found no error. That Court

considered such determination to be binding on appellant.

This case is not controlled by Jackson v. Pernio. 378

U. S. 368, 12 L. Ed. (2d) 908, since”tlm~statement was not

aHnuTEM into evidence, and there was no issue of voluntari

ness to be considered by the jury. It thus does not run

afoul of Jackson.

Since Jackson was decided after the instant case was

tried, there was no way its holding could be applied. The

trial court followed what at that time was approved pro

cedure.

Appellant makes much of being faced with a cruel

dilemma. At his trial he could have moved for a mistrial,

and if it had been demiedTT^

question on appeal. He could have requested an instruction

MacDougall, 245 S. C.

that the jury be told to disregard any reference to a state

ment. South Carolina law (Section 17-513.1, 1962 Code)

provides that the jury shall be excused and counsel and

litigants shall be given the opportunity to express objections

to the charge or to request the charge of additional propo

sitions made necessary by the charge. This requirement

was strictly followed by the trial judge S.C.T. 86. The

appellant requested no additional proposition to be charged.

When the matter of a statement was first approached

by the State, the appellant could have objected and re

quested that the matter be considered out of the presence

of the jury. This he did not do. It is not incumbent upon

the prosecution to represent both the State and the de

fendant. A criminal prosecution is still an adversary pro

ceeding. Appellant has sought to preserve every vice, take

his chances upon a verdict, and then assert those vices.

This is proscribed by Robinson, supra.

Appellees submit that no prejudice resulted to appel

lant from such testimony, and that any right to further

object has been waived.

Moorer, Appellant, v. State op S. C. et a l , Appellees 9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the dis

trict court should be affirmed and the cause remanded for

the execution of the judgment by the Supreme Court of

South Carolina.

Respectfully submitted,

DANIEL R. McLEOD,

Attorney General,

E. N. BRANDON,

Assistant Attorney General,

Wade Hampton State Office

Building,

Columbia, South Carolina,

JULIAN S. WOLFE,

Solicitor, First Judicial Circuit,

Orangeburg, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellees.

10 M oorer, A ppellant, v . State of S. C. et al., A ppellees