Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Rohan Petition for a Writ of Certiorari for the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Rohan Petition for a Writ of Certiorari for the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 1960. fdd90bbc-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/161515cd-142d-4f4e-8429-faa31706e083/idlewild-bon-voyage-liquor-corp-v-rohan-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-for-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-second-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

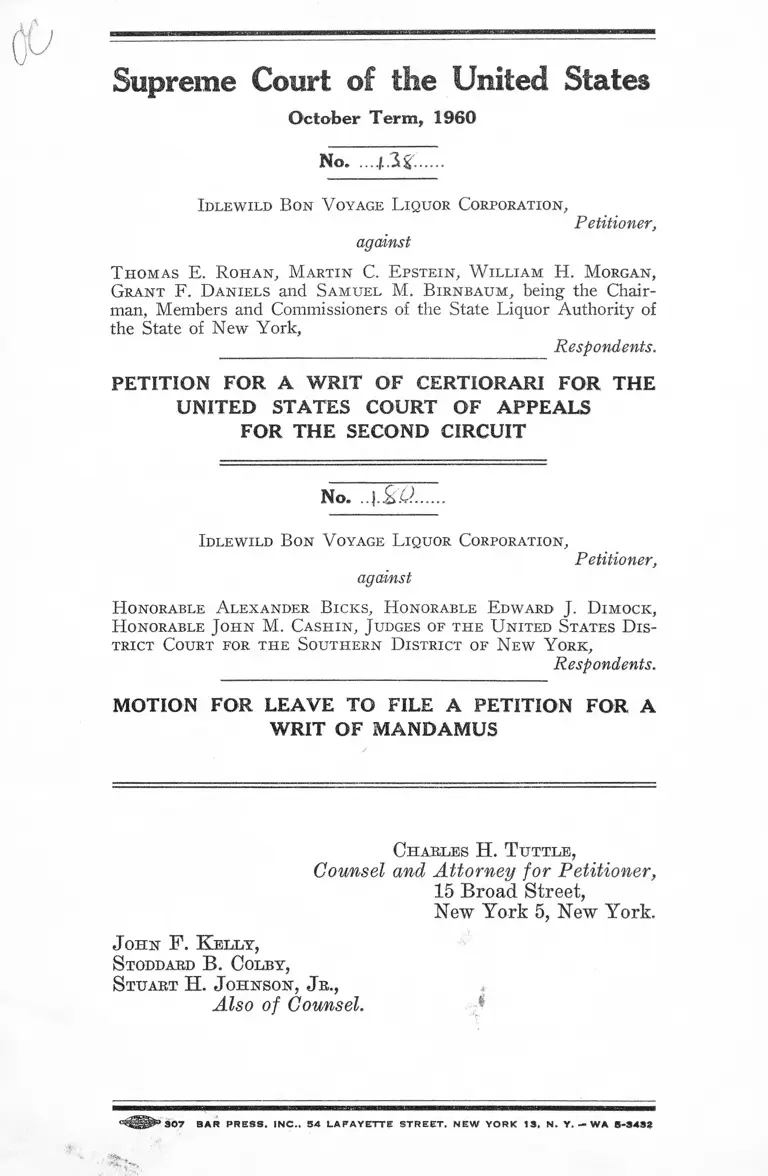

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No. .1 %.....

I dlewxld B on V oyage L iquor Corporation ,

against

Petitioner,

T h o m a s E . R o h a n , M a r tin C, E p s t e in , W il l ia m H . M organ ,

G r a n t F. D a n ie l s and S a m u e l M. B ir n b a u m , being the Chair

man, Members and Commissioners of the State Liquor Authority of

the State of New York,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FOR THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. , . | .....

I dle w ild B on V oyage L iquor C orporation ,

against

Petitioner,

H onorable A lex a n d er B ic k s , H onorable E dward J . D im o c k ,

H onorable J o h n M . C a s h in , J udges of t h e U n ited S tates D is

trict C ourt for t h e S o u t h er n D istr ic t of N ew Y ork ,

Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A PETITION FOR A

WRIT OF MANDAMUS

Charles H. Tuttle,

Counsel and Attorney for Petitioner,

15 Broad Street,

New York 5, New York.

J ohn F. K elly,

S toddard B. Colby,

S tuart H. J ohnson, J r.,

Also of Counsel. *

* 3 0 7 B A R P R E S S . IN C ., S 4 L A F A Y E T T E S T R E E T . N E W Y O R K 1 3 , N . Y. — W A 8 - 3 4 3 2

I N D E X

The Applications ......................................................... 1

Reference to Opinions Below ..................................... 2

Jurisdictional Statement ............................................ 3

The Questions Presented ............................................ 4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.... 7

(1) Federal Constitutional Provisions ............. 7

(2) Federal Statutes and Regulations ............... 7

(3) New York State Statutory Provisions ........ 8

Statement of the Case .................................................. 8

(1) The Importance of this Case ........................ 8

(2) The Nature of the Case ................................ 9

(3) Idlewild’s Lawful Export Business ............ 9

(4) The State Liquor Authority’s Assertion that

Idlewild’s Business is “ Illegal” under New

York L aw ....................................................... 11

(5) The Institution of this Action to Protect

Idlewild’s Federal Rights ............................. 11

(6) The Representations of the State Liquor

Authority Before Judge Bicks that Idle

wild’s Business was not Threatened .......... 12

(7) Judge Bicks’ Decision Remitting Idlewild to

the State Courts .......................................... 12

PAGE

11 Index

PAGE

(8) Idlewild’s Appeal and the Immediate Extra-

legal Retaliation by the State Liquor Au

thority ........................................................... 18

(9) Judge Dimock’s Decision .............. 14

(10) The Court of Appeals’ Decision ................. 14

(11) Judge Cashin’s Decision .............................. 16

(12) The Court of Appeals’ Refusal to Recall

and Clarify Its Judgment ............................ 16

A r g u m e n t .................................................................... 17

P o in t I—Idlewild’s petition for certiorari to review

the admittedly “ anomalous” majority decision

of the Circuit Court of Appeals presents impor

tant questions of federal constitutional and statu

tory law and of judicial jurisdiction which should

he settled by this Court ....................................... 17

P o in t II—This petition for certiorari also presents

for review the failure and refusal by the Court

of Appeals to vacate the orders below which it

itself held were rendered without jurisdiction—a

refusal in conflict with decisions of the Courts of

Appeals for the Third, Fifth and Sixth Circuits

and in conflict with the implications of decisions

by the Supreme Court ......................................... 19

P o in t III—Also a writ of mandamus is a further

proper means of requiring Judge Bicks and

Judge Dimock to convene a three-judge court for

determining Idlewild’s constitutional rights, or,

failing that, to exercise for the protection of the

plaintiff’s statutory rights original jurisdiction

under 28 U. S. C., Sections 1337 and 1331 ......... 22

Index

P oint IV—Furthermore, there was also no occasion

to abstain in deference to the New York courts

because those courts have settled the State Law

in Idlewild’s favor, and also because the state

remedies are inadequate ........................................ 26

P oint V—A writ of mandamus to review the decision

of Judge Dimock, as well as the decision of Judge

Bicks, is likewise proper here .............................. 29

P oint VI—Judge Cashin’s decision constitutes such

a departure from the accepted and usual course

of judicial proceedings as to call for an exercise

of this Court’s power of supervision by writ of

mandamus ............................................................. 31

Conclusion .................................................................. 32

iii

PAGE

IV Index

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Albee Godfrey Whale Creek Co. v. Perkins, 6 F. Supp.

409 (S. D. N. Y., 1933) ........................................ 30

All American Airways v. Village of Cedarhurst, 2

Cir., 201 F. 2d 273 .............................................. 5, 22, 24

Alleghany County v. Mashuda Co., 360 U. S. 185 ...... 25

Barcus v. O’Connell, 281 App. Div. 1064 (3rd Dept.,

1953) ...................................................................... 27

Bell v. Waterfront Comm, of N. Y. Harbor, 183 F.

Supp. 175, aff’d 2 Cir., 279 F. 2d 853 ...................18, 30

Board of Supervisors v. Tureaud, 5 Cir. 207 F. 2d

807, vacated and remanded on other grounds, 347

U. S. 971 ........................................................... 6,17,21

Board of Trustees v. U. S., 289 U. S. 48 ..................... 22

Bransford, Ex Parte, 310 TJ. S. 354 ............................ 4,18

Burack v. State Liquor Authority of the State of

New York, 160 F. Supp. 161 (E. D. N. Y., 1958) .... 6, 27

California Commission v. United States, 355 U. S.

534 .................................................................... 24,27,30

Chicago v. Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe R. Co., 357

U. S. 77 ................................................................ 24

Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay Transit Co. v. Nims,

6 Cir., 252 F. 2d 317 ................................... 6,16, 20, 31

Collins v. Yosemite Park Co., 304 U. S. 518............... 23, 30

Corporation Comm. v. Cary, 296 U. S. 452 ................. 28

Dictograph Products Co. v. Sonotone Corp., 2 Cir.,

230 F. 2d 131 dism. per stipulation 352 U. S.

883 ..........................................................................29,32

Driscoll v. Edison Co., 307 U. S. 104............................. 28

During v. Valente, 267 App. Div. 383 (1st Dept., 1944) 5, 26

PAGE

Index v

PAGE

Epstein v. Goldstein, 2 Cir., 110 F. 2d 747 .................16, 20

Federal Trade Comm. v. Smith, 34 F. 2d 323 (S. D.

X. Y., 1929) ........................................................... 30

Florida Lime Growers v. Jacobsen, 362 U. S. 73 ...... 25

Gen. Tobacco & Grocery Co. v. Fleming, 6 Cir., 125

F. 2d 596 ............ ' ................................................ 30

Gulf Oil Corp. v. McGoIdrick, Matter of, 256 App.

Div. 207 (1st Dept., 1939) aff’d 281 X. Y. 647,

aff’d McGoIdrick v. Golf Oil Corp., 309 II. S.

414 ......................................................................... 5, 26

Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620 .....................26, 28

Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 IT. S. 52 ............................... 23

Johnson v. Yellow Cab Co., 321 IT. S. 383 ................. 23

Maynard & Child, Inc. v. Shearer, Ky., 290 S. W.

2d 790 .................................................................... 23

McQuillen v. Dillon, 2 Cir., 98 F. 2d 726, cert. den.

305 I . S. 655 .........................................................16, 32

Mountain States Co. v. Comm., 299 U. S. 167 ............ 28

Xational Comics Publications v. Fawcett Publica

tions, 2 Cir., 198 F. 2d 927 ................................... 16, 20

Xational Distillers Products Corp. v. City and County

of San Francisco, Cal., 297 P. 2d 61 22

Pacific Tel. Co. v. Kuykendall, 265 IT. S. 196 ............. 28

Parrott & Co. v. City and County of San Francisco,

Cal., 280 P. 2d 881 .............................................. 23

Penagaricano v. Allen Corporation, 1 Cir., 267 F. 2d

550 ......................................................................... 5,24

Pennsylvania v. Xelson, 350 U. S. 497 ........................ 18, 23

VI Index

PACTS

Pollitz v. Wabash R. Co., 180 F. 950 (C. C. S. D.

X. Y.) .................................................................... 16, 32

Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 TJ. S. 218..........18, 23

Rosenblum v. Frankel, 279 App. Div. 66 (1st Dept.,

1951) ...................................................................... 5,26

Securities & Exchange Comm. v. Tung Corp., 32 F.

Supp. 371 (N. D. 111., 1940) ................................. 30

Stratton v. St. Louis S.W. Rwy. Co., 282 TJ. S.

10 ........................................... 3,16,19,31

Two Guys From Harrison—Allentown, Inc. v. Mc-

Ginley, 3 Cir., 266 F. 2d 427 ............................6,17, 20

Vallely v. Northern Fire Ins. Co., 254 TJ. S. 348 ........16, 32

Yacht Club Catering v. Bruekman, Matter of, 276

N. Y. 44 ................................................................ 27

S ta tu te s

28 U. S. C.:

§1254(1) ................................................................ 3

§1291 ...............................................................4,7,17,19

§1292 ...............................................................4,7,17,19

§1331 ................................................4, 5, 7,13,18,19, 22

§1337 ................................................4, 5, 7,13,18,19, 22

§1341 ...................................................................... 28

§1342 ...................................................................... 28

§1651(a) ................................................................ 3

§2106 ...............................................................6,7,17,21

§2281 ................................................................ 4,5,7,12

§2284 ................................................................ 4,5,7,12

Index

PAGE

Constitution of the United S ta tes................................ 9

Article I §8 ........................................................... 7

Article I §10 ......................................................... 7, 22

Article VI ............................................................. 7

Export-Import Clause .......................................4, 5, 22

Foreign Commerce Clause ................................... 4, 5

Supremacy Clause ................................................ 4, 5

New York Alcoholic Beverage Control Law ............. 5, 26

§3(28) .................................................................... 11

§121 .................................................................. 6,8,9,27

Tariff Act of 1930,19 U. S. C. §1311................. 4, 5, 7,10, 23

§311 .................................................................. 10,18,23

19 C. F. R. part 18 ...........................................4, 5, 7, 23

19 C. F. R. part 19 ...........................................4, 5, 7, 23

Internal Revenue Code:

26 IT. S. C. §5521 ............................................ 4, 5, 7, 23

26 U. S. C. §5522 ............................................ 4, 5, 7, 23

26 U. S. C. §5523 .................................................. 7

New York State Tax Law:

§420(10) ................................................................ 10

§424 ........................................................................ 10

§429 ....................................................................... 10

vii

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No.

I dlew ild B on V oyage L iquor Corporation ,

against

Petitioner,

T h o m a s E. R o h a n , M a r t in C. E p s t e in , W il l ia m H. M organ ,

G r a n t F. D a n ie l s and S a m u e l M. B ir n b a u m , being the Chair

man, Members and Commissioners of the State Liquor Authority of

the State of New York,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FOR THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Now

I dlew ild B on V oyage L iquor Corporation ,

against

Petitioner,

H onorable A lexa nder B ic k s , H onorable E dward J . D im o c k ,

H onorable J o h n M . Ca s h in , J udges of t h e U n ited S tates D is

tr ic t C ourt e'or t h e S o u t h er n D istr ic t of N ew Y ork ,

Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A PETITION FOR A

WRIT OF MANDAMUS

The Applications

Petitioner, Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corporation,

(hereafter called “ Idlewild” ), seeks a writ of certiorari

to review the decision of a divided United States Court

2

of Appeals for the Second Circuit, rendered April 14, 1961,

which dismissed its appeals from decisions by Judge Bicks

and Judge Dimock; and to review so much of the Injunction

Order of the Circuit Court of Appeals, dated May 15,

1961, as denied Idlewild’s motion to recall and clarify the

judgment of that Court so as to conform to its decision.

Furthermore, Idlewild hereby moves for] leave to file a

petition for a writ of mandamus directed to Honorable

Alexander Bicks, Honorable Edward J. Dimock and Hon

orable John M. Cashin, Judges of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of New York, requir

ing them to convene a district court of three judges and

to grant Idlewild further appropriate relief.

These petitions for a writ of certiorari, and/or for

a writ of mandamus, are presented together because they

arise out of identical facts, but differing judicial views,

on the important question of federal jurisdiction and

procedure common to both petitions, namely: what is

the appropriate forum to determine the admittedly “ sub

stantial” Federal constitutional and statutory rights of

Idlewild, “ a party who we believe is entitled to relief”

(110a) * according to the Court of Appeals, in the face

of immediate irreparable injury threatened by the New

York State Liquor Authority.

Idlewild’s complaint invoked its constitutional rights,

its statutory rights, and such other relief as may be just

and proper.

Reference to Opinions Below

Judge Bicks’ initial decision of November 4, 1960 (49a)

is reported at 188 F. Supp. 434.

Judge Dimock’s subsequent opinion (88a) and order

(93a) have not been officially reported.

* All such references are to the pages of Petitioner’s Appendix.

3

The majority and dissenting opinions of the Court of

Appeals (103a, 111a) dismissing Idlewild’s appeals from

the decisions of Judge Bicks and Judge Dimoek have not

yet been officially reported. The judgment of the Court

of Appeals is reprinted at 116a.

Judge Cashin’s subsequent decision and order (130a)

have not been officially reported.

The Injunction Order of the Court of Appeals, denying,

inter alia, Idlewild’s application for clarification of its

judgment, is reprinted at 147a.

Jurisdictional Statement

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

April alC 1961, and the Injunction Order of the Court of

Appeals, denying Idlewild’s alternative application to re

call and clarify its judgment, was entered on May 15, 1961.

The decisions of Judges Bicks, Dimoek and Cashin,—all

denying Idlewild’s successive applications to convene a

district court of three judges and for injunctive relief,

were rendered on November 4, 1960, December 28, 1960

and May 3, 1961, respectively.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked on certiorari

under 28 U. S. C. §1254(1) because the decision of a

divided Circuit Court of Appeals presents important ques

tions of federal constitutional and statutory law and juris

diction, and, in our view, is in conflict with applicable

decisions of this Court and other U. S. Courts of Appeal—

questions which should now be definitively settled by this

Court (Buie 19).

The jurisdiction of this Court to issue a writ of man

damus is invoked under 28 U. S. C. §1651 (a). The applica

tion for mandamus is made pursuant to the holding of the

majority of the Court of Appeals, on authority of Stratton

v. St. Louis S.W. Rwy. Co., 282 U. S. 10, that Idlewild’s

“ proper remedy was a writ of mandamus from the Su

4

preme Court” (106a) to review the refusals of Judge Bieks

and Judge Dimock to convene a three-judge district court

for a determination of the ‘‘substantial federal question”

here presented by “ a party who we believe is entitled to

relief” (104a, 107a, 108a, 110a), and the subsequent holding

by Judge Cashin that those refusals are “ the law of the

case” and Idlewild’s remedy “ is a writ of mandamus”

(135a).

The Questions Presented

(1) Should a district court of three judges he convened,

pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§2281 and 2284, where the un

dented allegations of Idlewild’s complaint pose a “ sub

stantial federal question” as to the legality of attempted

State regulation of exports contrary both to (a) the For

eign Commerce Clause, (h) the Export-Import Clause, and

(c) the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution of the United

States, and to the preemptive provisions of the Tariff Act

of 1930, 19 U. S. C. §1311, together with the regulations

thereunder (19 C. F. R. Parts 18 and 19) and associated

provisions of the Federal Internal Revenue Code (26

U. S. C. §§5521 and 5522)?

(2) Does the Circuit Court of Appeals have jurisdiction

over final and otherwise appealable orders under 28 U. S. C.

§§1291 and 1292(a)(1) where, as here, single district

judges, having original jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C.

§§1337 and 1331, have denied Idlewild’s applications for

convening a thtee-judge district court, for enforcement

of its statutory rights, and for injunctive relief against

attempted regulation by the New York Liquor Authority

of exports contrary to the uniform construction by the

New York courts of the New York Alcoholic Beverage

Control Law {Ex Parte Brans ford, 310 U. S. 354, 361) ?

5

(3) Should the Federal District Court abdicate its

jurisdiction and deny Idle wild its statutory right (28

U. S. C. §§2281, 2284, 1331 and 1337) of access to the Fed

eral District Court to vindicate its substantial Federal

rights under the Federal Constitution, statutes and admin

istrative regulations, despite imminent irreparable injury,

where, as here,

(a) Idlewild is engaged solely in the business of ex

ports pursuant to an exclusive and preemptive Federal

program adopted by Congress pursuant to the Foreign

Commerce, Export-Import and Supremacy Clauses of the

Constitution of the United States;

(b) The Federal Tariff Act of 1930, 19 IT. S. 0. §1311,

together with the Regulations thereunder (19 C. F. R.

Parts 18 and 19) and the associated provisions of the In

ternal Revenue Code (26 U. S. G. §§5521 and 5522), con

stitute a comprehensive, exclusive and preemptive Federal

program for the promotion of exports of liquor in foreign

commerce, and hence Idlewild is entitled to the relief it

seeks even if, contrary to the uniform New York decisions,

the Alcoholic Beverage Control Law should be held ap

plicable here (Penagaricano v. Allen Corporation, 1 Cir.,

267 F. 2d 550', 557-558; All American Airways v. Village

of Cedarhurst, 2 Cir., 201 F. 2d 273, 277);

(c) The New York Courts have uniformly held that

the New York Alcoholic Beverage Control Law is inap

plicable or “ inoperative” if applied to sales of liquor for

export in foreign commerce under constant United States

Customs Bond, regulation and supervision,—the very trans

actions here involved. (Matter of Gulf Oil Corp. v. Mc-

Goldrick, 256 App. Div. 207, 209, 210 (1st Dept,, 1939),

aff’d 281 N. Y. 647, aff’d McGoldrich V. Gulf Oil Corp., 309

U. S. 414; During v. Valente, 267 App. Div. 383, 386 (1st

Dept., 1944); Rosenblum v. Frankel, 279 App. Div. 66, 68

(1st Dept., 1951);

6

(d) The State Court remedies provided by the New

York Alcoholic Beverage Control Law, §121, have already

been judicially considered and held ‘ ‘ inadequate ’ ’ (Burack

v. State Liquor Authority of the State of New York, 160

F. Supp. 161,165 (E. D. N. Y., 1958) ?

(4) Where the Court of Appeals has dismissed appeals

from orders otherwise appealable, on the ground that such

orders were made without jurisdiction because only a dis

trict court of three judges could determine the “ substan

tial federal question” presented, should the Court of Ap

peals vacate the orders under appeal and remand the case

to the District Court for proceedings not inconsistent with

its decision (28 U. S. C. §2106; Two Guys From Harri

son-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, 3 Cir., 266 F. 2d 427, 433;

Chicago, Duluth db Georgian Bay Transit Co. v. Nims, 6

Cir., 252 F. 2d 317, 319; Board of Supervisors v. Tureaud,

5 Cir., 207 F. 2d 807, 810, vacated and remanded on other1

grounds, 347 U. S. 971.)?

(5) Are the judges of the Federal District Courts so

bound by the doctrine of “ the law of the case” that they

are required to follow a prior decision of another district

judge of the same Court without regard either to a radical

change in the circumstances presented to the first judge

or a subsequent holding by the Circuit Court of Appeals

that the decision of the first district judge was erroneous

and without jurisdiction?

7

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

(1) Federal Constitutional Provisions

(a) “ The Congress shall have Power # * To regulate

Commerce with foreign Nations” (Art. I, §8).

(b) “ No State shall, without the Consent of the Con

gress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports”

(Art. I, §10)1

(c) “ This Constitution, and the laws of the United

States which shall he made in Pursuance thereof * * *

shall he the Supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in

every State shall be hound thereby, any Thing in the Con

stitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwith

standing” (Art. VI).

(2) Federal Statutes and Regulations

The Appendix sets forth the pertinent provisions of

the Federal Statutes providing for (a) a district court of

three judges in constitutional cases 28 U. S. C. §§2281 and

2284 (1) and (3) (148a); (b) original jurisdiction of the

federal district courts in federal question cases and cases

arising under any Act of Congress regulating commerce,

28 U. S. C. §§1331 and 1337 (149a); (c) appellate juris

diction of the Circuit Court of Appeals over final orders

and interlocutory orders of the district courts refusing

injunctions, 28 U. S. C. §§1291 and 1292(a)(1) (149a);

(d) the powers of the federal appellate courts, 28 U. S. C.

§2106 (150a); and (e) the pertinent substantive provi

sions of the Federal Tariff Act of 1930, 19 U. S. C. §1311

(17a), together with the applicable regulations thereunder,

19 C. F. R. Parts 18 and 19 (154a), and associated pro

visions of the Internal Revenue Code, 26 U. S. C. §§5521,

5522, and 5523 (150a).

8

(3) New York State Statutory Provisions

The pertinent provisions of the New York Alcoholic

Beverage Control Law are reprinted in the Appendix (30a-

33a).

Statement of the Case

(1) The Importance of this Case

These petitions for certiorari and/or mandamus are

Idlewild’s last resort in its long quest for a remedy for its

admittedly “ substantial” Federal rights under the Consti

tution and laws of the United States invoked in its com

plaint.

Here are many questions of importance to the due

administration of justice throughout the federal system,

as evidenced by the bewildering^/ different views expressed

in the five judicial opinions presented for review.

Such questions include (a) Idlewild’s statutory right

of access to the federal district courts to protect its sub

stantial constitutional and statutory federal rights against

State interference where the federal rights are preemptive

and exclusive, the State courts themselves have so held,

and the State judicial remedies are inadequate; (b) the

proper tribunal to determine such federal rights in the

first instance; (c) the appellate jurisdiction of the Circuit

Courts of Appeals and of this Court in such cases; and

(d) the proper application of the “ law of the case” by

the federal district courts.

The decisions below have left the proverbial “ little

fellow” helplessly caught in the gears of the cumbersome

machinery of justice amid a welter of contradictory deci

sions possessing but one common denominator,—a refusal

to afford a remedy for Idlewild’s substantial Federal

rights in a situation where the Court of Appeals has de

9

scribed the plaintiff Idlewild as ‘ ‘ a party who we believe is

entitled to relief.”

This case, we submit, cries out for review by this Court

to the end that others may not become inextricably en

meshed in a similar procedural web, after four decisions

and five different opinions, and with a hearing on the merits

not yet in sight a year after this urgent case was com

menced and large expense has been necessitated.

(2) The Nature of the Case

This action is for declaratory and injunctive relief and

for an adjudication that the Constitution and laws of the

United States preclude the application of the New York

State Alcoholic Beverage Control Law to Idlewild’s export

business and the destruction thereof by the New York

Liquor Authority.

As Judge Dimock noted (9$a):

“ Plaintiff certainly raises a serious legal issue when

it states that what New York is regarding as unlawful

has been ruled by the United States to be lawful for

eign commerce.”

The Court of Appeals thrice held that “ a substantial

federal question” is thus presented (104a, 107a, 108a).

(3) Idlewild’s Lawful Export Business

Idlewild, a New York corporation, is engaged in selling

United States Customs bonded, tax-free wines and liquors,

solely for export, to overseas passengers from premises

leased from the New York Port Authority, a bi-State

agency, at Idlewild Airport (49a-50a, 90a, 130a-131a).

Each bottle of liquor sold by Idlewild remains under

continuous United States Customs bond, regulation and

supervision from the time it is withdrawn from Class 6

10

United States Government bonded manufacturing ware

houses, and the United States Customs bonded storage

warehouses; during the time it is rewarehoused at Idle-

wild’s premises under United States Customs control, until

the bottle is placed aboard the aircraft for delivery to the

passenger only upon and after arrival at his foreign desti

nation (3a-5a, 36a). Idlewild is required to account, on

United States Customs forms, for each and every bottle

(3a, 36a).

The privilege accorded the outgoing passenger to ex

port liquor free of tax and duty here or abroad is reciprocal

to the privilege accorded incoming passengers to purchase

a limited quantity of liquor in foreign countries for im

port into the United States free of tax or duty here or

abroad (5a-6a, 37a).

The obvious purposes of the right of thus exporting a

bottle of liquor tax-free are (1) to encourage foreign com

merce, and (2) to promote domestic exports,—a particu

larly pressing national interest in view of the present

crisis in our balance of payments.

The United States Treasury Department, Bureau of

Customs, supervises the conduct of Idlewild’s business.

It has approved Idlewild’s premises, and has prescribed

Idlewild’s procedures. Finally, the United States Treasury

Department, Bureau of Customs has expressly ruled that

Idlewild’s business constitutes the exportation of mer

chandise within the meaning of §311 of the Tariff Act of

1930, 19 U. S. C. §1311 (50a, 131a, 15a-20a).

The New York State Tax Commission has also ruled

that a business such as Idlewild’s, which consists of sales

of liquor in United State Customs bond withdrawn from

Class 6 warehouses under federal regulation, is not a

“ sale” subject to the New York State Alcoholic Beverage

tax. Tax Law §§420(10), 424, 429 (26a-27a).

11

(4) The State Liquor Authority’s Assertion that Idlewild’s

Business is “Illegal” under New York Law

Out of an abundance of caution, Idlewild inquired of

the State Liquor Authority whether its business was sub

ject to the New York State Alcoholic Beverage Control

Law. The State Liquor Authority sought and obtained an

opinion from the New York State Attorney-General (1960,

Op. Atty. Gen., June 30) to the effect that (1) Idlewild’s

business constituted a “ sale” within the meaning of the

Alcoholic Beverage Control Law, §3(28), but (2) there is

no provision of that Law which would authorize a license

for such sales for export, and (3) no person can sell

alcoholic beverages within New York without a license

(51a, 90a, 131a, 21a-24a).

Thereupon the State Liquor Authority determined, and

so advised Idlewild’s counsel (25a), that its business

<<# * * is in conflict with the laws of the State of New

York and, therefore, would be illegal.”

(5) The Institution of this Action to

Protect Idlewild’s Federal Rights

The immediate practical effect of this “ determination”

was to place Idlewild in dire jeopardy. As Judge Bicks

found (51a, 188 F. Supp. at p. 436):

“ The New York Importers & Distillers Association

circularized its members advising that in view of the

position of the Attorney General and of §62 of the

Alcoholic Beverage Control Law, they could not legally

fill plaintiff’s orders. Plaintiff has not since been

able to make purchases to meet its requirements and

faces the prospect of closing its doors, with conse

quent substantial damage.”

12

This action was accordingly instituted on July 22, 1960,

for the protection of Idlewild’s constitutional and statu

tory rights; and a motion for the impanelling of a three-

judge court pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§2281 and 2284 ( 32a)

and an application, by order to show cause, for a temporary

injunction (33a-34a) were filed and served simultaneously

with the complaint.

(6) The Representations of the State

Liquor Authority Before Judge

Bicks that Idlewild’s Business was

not Threatened

Confronted with the square conflict between their claim

of illegality under State Law and Idlewild’s federal rights,

the State Liquor Authority sought to delay an adjudica

tion. It appeared before Judge Bicks by the Attorney-

General of the State of New York and cross-moved to dis

miss the complaint on the ground that the state courts af

forded an “ efficient remedy” and that (42a, 75a):

“ The complaint makes no claim that the State

Liquor Authority is threatening, directly or indirectly,

to take steps to interfere with plaintiff’s operations.

Since the plaintiff is a non-licensee, there is no real

action the State Liquor Authority can take against

the plaintiff. ’ ’

(7) Judge Bicks’ Decision Remitting

Idlewild to the State Courts

Because of what he deemed to be the “ tentative and

hypothetical posture” of the case before him (53a), Judge

Bicks decided (55a, 188 F. Supp. 437-8):

“ Although the substantive issues raised in the com

plaint may not be considered by the judge to whom

application under 28 U. S. C. A. §2281 is made, he has

13

the power to retain jurisdiction pending state court

adjudication where, as here, there is insufficient basis

to support intervention by a federal court of equity.

(Citing cases)

“ Motion for impanelling of a three-judge court

denied, with leave to renew after the state court has

ruled.”

Judge Bicks’ decision disregarded Idlewild’s statutory

right to the exercise by him of original jurisdiction under

28 U. S. C. §§1337 and 1331.

(8) Idlewild’s Appeal and the Immediate Extra-legal

Retaliation by the State Liquor Authority

Idlewild promptly appealed Judge Bicks’ decision

(56a).

Five days later, the State Liquor Authority issued a

subpoena duces tecum directed to Idlewild. Notwithstand

ing its representations before Judge Bicks that “ since

the plaintiff is a non-licensee, there is no real action the

State Liquor Authority can take against the plaintiff”

(64a, 67a, 75a), the subpoena expressly required Idlewild to

appear and testify concerning its business “under the li

cense to sell alcoholic beverages issued by the State Liquoi

Authority” (69a).*

Thus, the State Liquor Authority, acting under color

of State law, reversed its field and. went back on its rep

resentation to Judge Bicks that “ there is no real action”

or ‘ ‘ steps to interfere ’ ’ which it could take against Idlewild.

Instead, it sought to cut in ahead of the Court of Appeals

and to hale Idlewild before itself for an inquisition as prose

cutor, judge and jury to pass upon its own assault upon

Idlewild’s Federal rights.

No more overt interference could there be than the

bald threats thereafter made on three occasions by officials

of the State Liquor Authority to the several United States

* Emphasis has been supplied throughout this petition.

14

Customs bonded interstate truckers who had been making

deliveries to Idlewild (76a, 78a-81a). This was a palpable

attempt, vi et armis, to frustrate Idlewild’s resort to the

federal courts by choking off its last lifeline of supply

from out-of-state sources to which Idlewild had been driven

because the State Liquor Authority’s prior determination

of illegality had frightened off its New York suppliers

(51a, 131a).

(9) Judge Dimock’s Decision

Accordingly, Idlewild again moved for a temporary in

junction pendente lite and for the impanelling of a three-

judge court (71a-72a). This motion, together with Idle-

wild’s application to quash the subpoena duces tecum,

came on before Judge Dimock, who held that he had to

follow Judge Bicks (89a), but that (91a):

“ Plaintiff is entitled to an injunction against har

assment by defendant pending the appeal from the

order of Judge Bicks.”

(10) The Court of Appeals’ Decision

A majority of the Court of Appeals, Chief Judge

Lumbard dissenting, held that since “ a substantial federal

question existed” (104a, 107a, 108a), “ a three-judge dis

trict court should have been convened” by Judge Bicks

and Judge Dimock to decide, inter alia, whether to apply

the so-called doctrine of “ abstention” (109a, 110a). Ac

cordingly, although the orders of both judges were held to

be otherwise appealable (105a-106a, 109a, 111a), the ma

jority held that since Judge Bicks and Judge Dimock “ had

no jurisdiction to proceed * * * we must conclude from

Stratton that we have no jurisdiction to entertain an

appeal” from either decision (108a, 110a).

The majority conceded “ this result leaves us in a

somewhat anomalous position” (108a), and concluded

(110a) :

15

“ The results we reach are unhappy ones. We are

refusing access to our court to a party who we believe

is entitled to relief.”

Idlewild’s statutory right to the exercise of original

jurisdiction by the District Court with a single judge under

28 U. S. C. §§1337 and 1331 was at least impliedly overruled.

In his dissenting opinion Chief Judge Lumbard took is

sue, saying (114a-115a):

“ The majority’s view, however, imposes on the fed

eral courts a procedure of piecemeal review whereby

a court of appeals is always forced to stay its hand

whenever an appellant or appellee argues to it that

the decision below should have been made by a three-

judge court. No matter how worthless such a claim

may be, we would not be able to dispose of it on an

appeal from a final order but would have to await a

decision on a petition for mandamus in the Supreme

Court. Only after the Supreme Court decided the

jurisdictional question might we be permitted to con

sider the merits, and the merits would not be ripe for

Supreme Court review until we had passed upon them

on remand. II cannot believe that the authority of the

Supreme Court over three-judge tribunals was in

tended to extend so far as to preclude us from decid

ing the jurisdictional issue when a district judge enters

an order that is otherwise appealable under 28 U. S. C.

§§1291, 1292, and thereby to impose on the parties a

procedure calling for separate appellate consideration

of the jurisdictional and substantive questions.”

Thus, the sure result of the majority decision of the

Court of Appeals will be to flood this Court with petitions

for mandamus whenever, in a case where Federal constitu

tional rights are involved the district court applies the so-

called doctrine of abstention or claim has been unsuccess

fully made for decision by a three-judge court.

16

(11) Judge Cashin’s Decision

Idlewild promptly sought to comply with the decision

of the Court of Appeals and moved again in the District

Court to convene a three-judge district court and for in

junctive relief, in accordance with the procedure suggested

by this Court in Stratton v. St. Louis S. IF. Ry. Co., 282

U. ,S. 10, 18, and by Mr. Justice Stewart in Chicago, Duluth

(& Georgian Bay Transit Co. v. Nims, 6 Cir., 252 F. 2d 317,

319.

Judge Cashin denied these applications. He character

ized as “ dictum” the holding by the Court of Appeals

that “ a three-judge district court should have been con

vened” (132a); and, overlooking the very ratio decidendi

of that Court, he followed as “ the law of this case” and

“ as still in full force and effect” (133a) the very refusals

by Judge Bicks and Judge Dimock to convene a three-

judge district court which the Court of Appeals had just

held to be erroneous, without jurisdiction and hence nul

lities. Vallely v. Northern Fire Ins. Co., 254 U. S. 348,

353-4; McQuillen v. Dillon, 2 Cir., 98 F. 2d 726, 729, cert,

den. 305 U. S. 655; Pollitz v. Wabash R. Co., 180 F. 950,

951 (C. C. S. D. N. Y.).

(12) The Court of Appeals’ Refusal to Recall

and Clarify Its Judgment

In a final effort to avoid burdening this Court, counsel

and the litigants with the expenditure of time, money and

effort entailed by these conflicting judicial expressions,

Idlewild moved in the Court of Appeals for an order clari

fying its judgment of dismissal (as authorized by National

Comics Publications v. Fawcett Publications, 2 Cir., 198 F.

2d 927 and Epstein v. Goldstein, 2 Cir., 110 F. 2d 747, 748)

so as to test Judge Cashin’s characterization as “ dictum,”

and to remand this case to the District Court for “ such

further proceedings * * * as may be just under the cir

17

cumstances,” as authorized by 28 IT. S. C. §2106 and as

was done under similar circumstances in Two Guys From

Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, 3 Cir., 266 F. 2d

427, 433, and Board of Supervisors v. Tureaud, 5 Cir., 207

F. 2d 807, 810, vacated and remanded on other grounds in

347 U. S. 971.

The Court of Appeals’ denial was without opinion

(147a).

ARGUMENT

P O I N T I

Idlewild’s petition for certiorari to review the ad

mittedly “anomalous” majority decision of the Cir

cuit Court of Appeals presents important questions

of federal constitutional and statutory law and of

judicial jurisdiction which should be settled b y this

Court.

(1) The majority in the Court of Appeals held that

since “ a substantial federal question exists” (104a, 107a)

in this case,

“ * # * we are of the opinion that the determination

of whether a federal court ought to abstain is a deter

mination that may only be made in the first instance by

a three-judge district court” (108a).

(2) All three judges in the Court of Appeals agreed

that “ the orders made by Judges Bieks and Dimock are of

the sort which are ordinarily appealable” to that Court

under 28 U. S. C. §§1291 and 1292(a)(1) (105a-106a, 109a,

I lia ) .

The majority, however, reached the frankly “anomalous

position” (108a) of distinguishing the recent decision of

the Second Circuit in Bell v. Waterfront Commission of

18

New York Harbor, 2 Cir., 279 F. 2d 853 (107a, 109a), and

of dismissing Idle wild’s appeals, on the very grounds that

Idlewild was right in its contentions that “ a substantial

federal question existed” on constitutional grounds and

that “ a three-judge district court should have been con

vened” by Judge Bieks and Judge Dimock (109a).

(3) Also, 'Idlewild’s complaint challenges, in addition,

the regulatory power of the State Liquor Authority on

Federal statutory grounds (irrespective of constitutional

issues) of which a single federal district judge clearly has

original federal jurisdiction under 28 IT. S. C. §§1331, 1337.

(Ex Parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354, 361.)

Thus, Idlewild contends that Section 311 of the Federal

Tariff Act of 1930, 19 U. S. C. §1311, and the detailed

federal regulation and supervision of the exports here in

volved are preemptive, and “ the scheme of federal regula

tion [is] so pervasive as to make reasonable the inference

that Congress left no room for the States to supplement

i t” . Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U. S. 497, 502; Rice v.

Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U. S. 218, 230.

The effect of the decision of the Court of Appeals was

also to nullify this statutory right to original jurisdiction.

(4) Idlewild further contends, inter alia, that the State

Liquor Authority is attempting here to misapply the New

York Alcoholic Beverage Law to exports in foreign com

merce, contrary to the uniform rulings of the New York

courts themselves and contrary to Idlewild’s Federal statu

tory rights.

“ In such a case the attack is aimed at an allegedly

erroneous administrative action” which “ does not require

a three-judge court” even though based on “ the uneonsti-

tutionality of the result obtained” . (Ex Parte Bransford,

310 U. S. 354, 361.)

19

(5) Here the majority in the Court, of Appeals held

that the mere presence of substantial Federal Constitu

tional questions as to state action (a) deprived a single

district judge, otherwise vested with original federal juris

diction on non-constitutional grounds under 28 U. S. C.

§§1331 and 1337, of all jurisdiction to decide the issues, and

(b) deprived the Court of Appeals of jurisdiction to review

such decisions, although they are “ ordinarily appealable”

(105a-106a, 109a, 111a) under 28 II. S. C. §§1291, 1292(a)

(1).

P O I N T II

This petition for certiorari also presents for re

view the failure and refusal by the Court o f Appeals

to vacate the orders below which it itself held were

rendered without jurisdiction,— a refusal in conflict

with decisions ©f the Courts of Appeals for the Third,

Fifth and Sixth Circuits and in conflict with the im

plications of decisions by the Supreme Court.

(1) Stratton v. St. Louis S.W. Rwy. Co., 282 U. S. 10,

was the decision principally invoked by the majority of

the Court of Appeals for its holding that Idlewild’s “ prop

er remedy was a writ of mandamus from, the Supreme

Court.” But in the Stratton case, this Court held (282

U. S. at p. 18) that although a writ of mandamus was still

available:

“ It is not necessary, however, that formal applica

tion should he made for such a writ, as the District

Court may now proceed to take the action which the

writ, if issued, would require.”

In keeping with this recommendation by this Court,

Idlewild thereupon attempted to comply with the majority

decision of the Court of Appeals by renewing its appli

20

cation to the District Court for the impanelling of a

three-judge court and for injunctive relief (117a). This

was the procedure proposed by Judge (now Mr. Justice)

Stewart in Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay Transit Co.

v. Nims, 6 Cir., 252 F. 2d 317, 319:

“ Were we to agree with the appellant’s position

that a court of three judges should have been con

vened, it would be our duty now to dismiss the appeal

for want of jurisdiction. An application to the Su

preme Court for a ivrit of mandamus ivould then be

available if the district judge declined to tahe steps

to effectuate the convening of a three judge tribunal.”

(Emphasis added.)

But when Judge Cashin characterized as “ dictum” the

majority decision of the Court of Appeals that the orders

of Judges Bicks and Dimock were without jurisdiction,

Idlewild applied to that Court for rectification or clarifica

tion of its mandate (as was done in National Comics Publi

cations v. Fawcett Publications, 2 Cir., 198 F. 2d 927 and

Epstein v. Goldstein, 2 Cir., 110 F. 2d 747, 748) so as to

make explicit what the majority decided:—that the orders

of Judge Bicks and Judge Dimock were nullities since with

out jurisdiction, were in consequence vacated, and the case

was remanded to the District Court for further proceedings

not inconsistent with the decision of the Court of Appeals

(146a).

Such was the procedure adopted under identical cir

cumstances by the Third Circuit in Two Guys From Harri-

son-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, 3 Cir., 266 F. 2d 427 where

the Court held that a three-judge district court was re

quired and concluded (p. 433):

“ Consequently we will vacate the judgment of the court

below and will remand the cause for appropriate ac

tion.”

21

Again, in Board of Supervisors v. Tureaud, 5 Cir., 207

F. 2d 807, vacated and remanded on other grounds, 347

U. S. 971, the Court concluded (p. 810):

“ We are in no doubt that the suit from which this

appeal comes was one for three judges, that the dis

trict judge was without jurisdiction to hear and de

termine the application for injunction, and that the

order should be vacated and the cause remanded to

the district judge with directions to take further pro

ceedings not inconsistent herewith.” (Emphasis

added.)

Such a procedure, in our view, is squarely authorized

by 28 U. S. C. §2106, which confers upon the federal ap

pellate courts jurisdiction to review and to:

“ * * # remand the cause and direct the entry of such

appropriate judgment, decree or order, or require such

further proceedings to be had as may be just under

the circumstances.”

We respectfully submit that by refusing to clarify its

judgment, the Court of Appeals “ has so far departed from

the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings, or

so far sanctioned such a departure by a lower court, as to

call for an exercise of this court’s power of supervision” .

(This Court’s Buie 19(1)(b).)

22

Also a writ of mandamus is a further proper

means of requiring Judge Bicks and Judge Dimock

to convene a three-judge court for determining Idle-

wild’s constitutional rights, or, failing that, to exer

cise for the protection of the plaintiff’s statutory

rights original jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C., Sections

1337 and 1331.

(1) These Sections expressly confer upon the District

Courts “ original jurisdiction of any civil action or pro

ceeding arising under any Act of Congress regulating com

merce,” or (when the controversy exceeds $10,000 in value)

“ under the Constitution, laws or treaties of the United

States” . (See Complaint, la et seq.)

(2) “Where the issue is essentially federal, the federal

court proceeds at o n c e ( A l l American Airways v. Village

of Cedarhurst, 2 Cir., 201 F. 2d 273, 277.) IdlewiM’s

federal rights arise not only under the Constitution hut

also under a comprehensive and preemptive federal statu

tory and regulatory scheme and program in the national

interest for the promotion of exports of domestic liquor

in foreign commerce free of Federal or State tax.

This federal scheme was adopted by Congress in the

exercise of its “ exclusive and plenary” constitutional

power to “ regulate commerce with foreign Nations” (Art.

I, §8, par. 3),—a power which “ may not be limited, quali

fied or impeded to any extent by state action” . Board of

Trustees v. U. 8., 289: U. S. 48, 56-57; National DistUlers

Products Corp. v. City and County of Can Francisco, Cal.,

297 P. 2d 61, 65. The “ exclusive and plenary” Federal

power is “ buttressed by” the Import-Export Clause (Art.

I, §10, par. 2), Board of Trustees v. U. 8., supra, 289 IT. S.

at pp. 56-57; Parrott & Co. v. City and County of San Fran

P O I N T I I I

23

cisco, Cal., 280 P, 2d 881, 885, and by “ the supremacy of

the national power in the general field of foreign affairs” ,

Sines V. Davidowitz, 312 U. S. 52, 62.

This preemptive Federal program for commerce with

foreign countries is, as stated at the outset hereof, em

bodied in Section 311 of the Tariff Act of 1930, 19 IT. S. C.

§1311 and the associated provisions of the Internal Revenue

Code, 26 IT. S. 0. §§5521 and 5522; and it also involves a

reciprocal pro tanto tax immunity as regards foreign coun

tries. It is also implemented by detailed regulations and

actual supervision and control by the United States Treas

ury Department, Bureau of Customs under the Tariff Act

(19 C. F. R. Parts 18 and 19).

Accordingly, particularly in view of the current crisis

in our balance of payments, we are dealing here with a

national concern ‘ ‘ so dominant that the federal system will

be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the

same subject” . Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U. S.

218, 230; Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U. 8. 497, 504; Sines

v. Davidowitz, supra, 312 U. S. 52, 62-69.

Moreover, “ the scheme of federal regulation [is] so

pervasive as to make reasonable the inference that Congress

left no room for the States to supplement i t” . Pennsyl

vania v. Nelson, supra, 350 U. S. at p. 502; Rice v. Santa

Fe Elevator Corp., supra, 331 U. S. 218, 230.

Accordingly, we submit, since the exported liquor here

involved is in a Federal enclave and under Federal sov

ereignty, the Federal courts may not abandon their statu

tory jurisdiction and obligation in exaggerated defer

ence to “ comity” . Johnson v. Yellow Cab Co., 321 U. S.

383, 386, 391-2; Collins v. Yosemite Park Co., 304 IT. 8. 518,

536-538 ; Maynard & Child, Inc. v. Shearer, Ky., 290 8. W.

2d 790, 794.

Both the specific terms of the Constitution and the fed

erated structure of our Government forbid New York and

its agencies to trespass upon legislation and regulation by

Congress acting in its own domain.

24

If the Alcoholic Beverage Control Law is inapplicable,

Idlewild will be entitled to an injunction against its at

tempted enforcement here. If, on the other hand, the New

York Law is applicable in its terms, then “ it wonld conflict

with federal law and the ban of the supremacy clause

would come into play.” Penagaricano v. Allen Corpora

tion, 1 C'ir., 267 F. 2d 550, 558. For this reason, the Court

upheld the exercise of jurisdiction in the Penagaricano case,

supra, stating (267 F. 2d at pp. 557-558):

“ * * * a preliminary glance at the apparent clash be

tween federal and local authority reveals that * * * the

exercise of federal authority here involved is wholly

within the confine of a valid federal enactment * * *.

And, whatever the local courts may hold to be the

meaning of the local Act, the plaintiffs will be entitled

to relief from its application. That is to say, the

plaintiffs will he entitled to the relief they request

ivhichever way the local Act is construed.” (Empha

sis added.)

Thus, even if the terms of the Alcoholic Beverage Con

trol Law should be construed to be applicable here, contrary

to the uniform decisions of the New York Courts (p. 26,

infra), “ there can be no doubt” of the “ direct clash” of

the New York Statute “ with the federal regulations” and

hence “ no occasion for postponement here for possible state

action.” All American Airways v. Village of Cedarhurst,

2 Cir., 201 F. 2d 273, 277; Chicago v. Atchison Topeka &

Santa Fe R. Co., 357 U. S. 77, 84, 89; California Com,mis

sion v. United States, 355 U. S. 534, 538, 539.

(3) The assertion of the State Liquor Authority that

under New York Law the plaintiff’s business was. “ il

legal” (25a) created an issue and was sufficient in itself to

deter the plaintiff’s domestic suppliers (51a, 131a). Hence

Judge Bicks was mistaken in regarding the issue as

25

in a merely “ tentative and hypothetical posture” (53a, 188

F. Supp. at p. 436).

In Florida Lime Groivers v. Jacobsen, 362 U. S. 73, this

Court reversed a three-judge District Court which had dis

missed a declaratory-judgment complaint on the ground

that there was no “ existing dispute as to. present legal

rights” hut only “ a mere prospect of interference posed

by the bare existence of the law in question” (362 U. S.

at p. 85). This Court, in language applicable a fortiori

here, said (362 U. S. at pp. 85^86):

“ It is therefore evident that there is an existing dis

pute between the parties, as to present legal rights

amounting to a justiciable controversy which appel

lants are entitled to have determined on the merits.”

(4) Furthermore, Judge Bicks was not justified in

abdicating his statutory jurisdiction, for such abdication

is justified only in extraordinary circumstances, wholly

absent here. As this Court held in Alleghany County v.

Mashuda Co., 360 U. S. 185, 188-189:

“ The doctrine of abstention, under which a Dis

trict Court may decline to- exercise or postpone the

exercise of its jurisdiction, is an extraordinary and

narrow exception to the duty of a District Court to

adjudicate a controversy properly before it. Abdica

tion of the obligation to. decide cases can be justified

under this doctrine only in the exceptional circum

stances where the order to the parties to repair to

the state court would clearly serve an important

countervailing interest. ’ ’

26

Furthermore, there was also no occasion to ab

stain in deference to the New York courts because

those courts have settled the State Law in Idlewild’s

favor, and also because the state remedies are in

adequate.

(1) In Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620, 629,

this Court held that there was no occasion for “ remitting

the claimant to the state courts for determination of the

local law question” where1, as here, the State courts have

given “ an authoritative interpretation of the local law.”

The New York courts have recognized the “ exclusive

and plenary” power of Congress to regulate foreign com

merce; “ the careful control exercised by government of

ficials over goods that have been taken into Class 6 Ware

houses” ; and the fact that such goods are “ constantly

under government supervision” pursuant to Section 311

of the Tariff Act of 1930,—the very Federal statute in

voked by Idlewild here under like circumstances (Matter

of Gulf Oil v. McGoldrich, 256 App. Div. 207, 209, 210

(1st Dept,, 1939), aff’d 281 N. Y. 647, aff’d McGoldrich v.

Gulf Oil Corp., 309 U. S. 414).

Accordingly, the New York courts have held that the

New York Alcoholic Beverage Control Law,—the very

statute which the State Liquor Authority here invokes,

was not applicable, or was “ inoperative” if applied, to

sales of liquor under United States Customs bond, regu

lation and supervision, for export in foreign commerce,-—

the very transactions here involved. (During v. Valente,

267 App, Div. 383, 386 (1st Dept., 1944). The New York

courts have therefore held that “ international transac

tions in alcoholic beverages * * * would be: beyond the

regulatory powers of the State Liquor Authority.”

(Rosenhlum v. Franhel, 279 App. Div. 66, 68 (1st Dept,,

1951)).

P O I N T I V

27

(2) Furthermore, “ abstention” is improper where, as

here, the state remedies are, as here, inadequate.

In the first place, as this Court held in California

Commission v. United States, 355 IT. S. 534, abstention is

improper where, as here, “ The Commission has plainly

indicated an intent to enforce the Act” (355 U. S. at p.

538), and the “ issue is a constitutional one that the Com

mission can hardly be expected to entertain” (355 U. S. at

p. 539). This Court concluded (p. 539):

“ But where the only question is whether it is consti

tutional to fasten the administrative procedure onto

the litigant, the administrative agency may be defied

and judicial relief sought as the only effective way of

protecting the asserted constitutional right.”

In the second place, Alcoholic Beverage Control Law

§121, on which the State Liquor Authority relied before

Judge Bicks (64a-65a), provides the sole method for judi

cial review of determinations of the State Liquor Author

ity, but limits any stay by the New York courts in such a

proceeding “ for a period not exceeding thirty days” .

Matter of Yacht Club Catering v. Bruck-man, 276 N. Y. 44

holds that this period is mandatory, regardless of “ ir

reparable damage to the individual” (276 N. Y. at p. 48).

In accord: Barcus v. O’Connell, 281 App. Div. 1064 (3rd

Dept., 1953).

For this reason, the State “ remedy” afforded by Sec

tion 121 is utterly “ inadequate” , Burack v. State Liquor

Authority of the State of New York, 160 F. Supp. 161

(E. D. N. Y., 1958), where the Court held (p. 165):

“ A further reason for) my conclusion is the pro

vision in §121, supra, that no stay shall be granted

pending the determination of the matter for a period

of more than thirty days. That period may not be ex

tended. Barcus v. O’Con/nell, 281 App. Div. 1064, 121

N. Y. S. 2d 366. Because of that 30-day provision

the time still available for the filing and final determi

28

nation of state court proceedings is inadequate. Even

if the plaintiff should be successful in such a proceed

ing he would win hut a Pyrrhic victory. ’ ’

In Pacific Tel. Co. v. Kuykendall, 265 U. S. 196, this

Court noted that the State law permitted a stay against

a decision of a State administrative tribunal for only a

limited period (there, one year). This Court reversed the

decision of the district court refusing jurisdiction, and

held (pp. 204-205):

“ Under such circumstances comity yields to con

stitutional right, and the fact that the procedure on

appeal in the legislative fixing of rates has not been

concluded will not prevent a federal court of equity

from suspending the daily confiscation, if it finds the

case to justify it.” (Emphasis added.)

Even under the statutes forbidding the district courts

to exercise jurisdiction over a challenge to State taxes or

rate orders, this Court has uniformly held that the district

court should exercise jurisdiction unless it affirmatively

appears that “ a plain, speedy and efficient remedy may

be had in the courts of such State.” 28 TJ. S. C. §§1341,

1342. Corporation Comm. v. Cary, 296 IJ. S. 452, 458;

Mountain States Co. v. Comm., 299 U. S. 167, 170; Driscoll

v. Edison Co., 307 U. S. 104, 110; Hillsborough v. Crom

well, supra, 326 U. S. 620, 628.

29

A writ of mandamus to review the decision of

Judge Dimock, as well as the decision of Judge Bicks,

is likewise proper here.

(1) Judge Dimock acknowledged (91a):

“ Plaintiff certainly raises a serious legal issue

when it states that what New York is regarding as un

lawful has been ruled by the United States to be law

ful foreign commerce.”

Judge Dimock further recognized that after Judge

Bicks’ decision and Xdlewild’s ensuing appeal, the State

Liquor Authority was attempting to drive Idlewild out of

business forthwith: first under color of State law, then by

its subpoena duces tecum, and then by overt threats to the

interstate truckers who were Idlewild’s last lifeline of

supply. Accordingly, he granted a stay pending the ap

peal from Judge Bicks (91a, 93a-95a).

In our view, the error in Judge Dimock’s decision was

in his narrow application of the doctrine of the “ law of

the case” by mechanically following Judge Bicks, despite

the State Liquor Authority’s subsequent repudiation of

its aforesaid representations to Judge Bicks and despite

the fact that under these changed circumstances “ there is

no imperative duty to follow the earlier ruling.” Dic

tograph Products Co. v. Sonotone Corp., 2 Cir., 230 F. 2d

131, 135', dism. per stipulation 352 U. S. 883.

(2) We also respectfully submit that, for the following

reasons, Judge Dimoek further erred in denying Idlewild’s

application to quash the subpoena duces tecum issued by

the State Liquor Authority.

P O I N T V

30

(a) The subpoena was an overt effort by the State

Liquor Authority to constitute itself as the tribunal to

pass upon its own assault on Idlewild’s Federal rights

and upon constitutional issues which the State Liquor Au

thority “ can hardly be expected to entertain.” California

Commission v. United States, supra, 355 U. S. at p. 530.

(b) Since the State Liquor Authority has no power

to regulate or license Idlewild’s export business, Collins v.

Tosemite Park Co., 304 U. S. 518, 539, its subpoena power

is correspondingly confined to matters within its jurisdic

tion to regulate or license. Gen. Tobacco £ Grocery Co. v.

Fleming, 6 Cir., 125 F. 2d 596; Federal Trade Comm. v.

Smith, 34 F. 2d 323 (S. D. N. Y., 1929); Securities £ Ex

change Comm. v. Tung Corp., 32 F. Supp. 371, 373 (N. D.

111., 1940).

(c) The subpoena was invalid under New York law since

Civil Practice Act §406(1) expressly precludes adminis

trative subpoenas relating to “ a matter arising, or an act

to be done, in an action in a court of record” ; and this

“ matter” was then actively sub judice.

(d) Judge Dimock’s denial of his power to quash the

subpoena was directly contrary to his own decision in Bell

v. Waterfront Comm, of N. Y. Harbor, 183 F. Supp. 175,

177, aff’d 2 Cir., 279 F. 2d 853, 858-9. See also Albee God

frey Whale Creek Co. v. Perkins, 6 F. Supp. 409', 410

(S. D. N. Y., 1933).

31

Judge Cashin’s decision constitutes such a de

parture from the accepted and usual course of judi

cial proceedings as to call for an exercise of this

Court’s power of supervision by writ of mandamus.

As already noted, Idlewild promptly sought to comply

with the majority opinion in the Court of Appeals by re

newing its application to the District Court for the con

vening of a three-judge district court and for injunctive

relief.

This was precisely in accordance with the procedure

suggested by this Supreme Court in Stratton v. St. Louis

S. W. Ry. Co., supra 282 IT. S. 10, 18, and by Judge (now

Mr. Justice) Stewart in Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay

Transit Co. v. Nims, supra, 252 F. 2d at p. 319.

Judge Cashin was clearly in error in characterizing

as “dictum” the very essence and ratio decidendi of the

majority of the Court of Appeals, thus clearly stated in

their opinion (108a, 110a):

“ Having decided that Judge Bicks had no juris

diction to proceed as he did, we must conclude from

Stratton that we have no jurisdiction to entertain an

appeal from his decision.

“ * * * we must hold that inasmuch as Judge Dimock

exercised power properly exercisable only by a three-

judge district court we have no jurisdiction to hear an

appeal from his order.”

Nevertheless Judge Cashin brushed these rulings aside

as “ dictum,” and held himself bound to follow as “ the law

of this case” and “ as still in full force and effect” the

very orders which the Court of Appeals had just held to

have been made without jurisdiction and hence without

existence in law.

P O I N T V I

32

Having been rendered without jurisdiction, the orders

of Judge Bicks and Judge Dimoek were as a matter of law

“ nullities” and “ void” , Vallely v. Northern Fire Ins. Co.,

254 IT. S. 348, 353-4; McQuillen v. Dillon, 2 Cir., 98 F. 2d

726, cert. den. 305 U. S. 655; Pollitz v. Wabash R. Co., 180

Fed. 950, 951 (C. C. S. D. N. Y.).

But even if these orders by Judges Bicks and Dimoek,

rendered without jurisdiction, could by any stretch of

imagination possibly constitute “ the law of this case,”

Judge Cashin was under “ no imperative duty to follow”

them. Dictograph Products Co. v. Sonotone Corp., supra,

230 F. 2d at p. 135.

Judge Cashin suggested (a) an application for reargu

ment to Judge Bicks,—a remedy which was wholly illusory

as practical matter (141a), and also (b) an application for

a writ of mandamus (135a).

Conclusion

Idlewild respectfully prays this Court to issue a writ

of certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit, and/or for leave to file its petition for writs

of mandamus directed to Judge Bicks, Judge Dimoek and

Judge Cashin; and for such other reliefs as may be just

and proper.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles H. T uttle,

Counsel and Attorney for Petitioner,

15 Broad Street,

New York 5, New York.

J ohn F. K elly,

S toddard B. Colby,

S tuart H. J ohnson, J r.,

Also of Counsel.