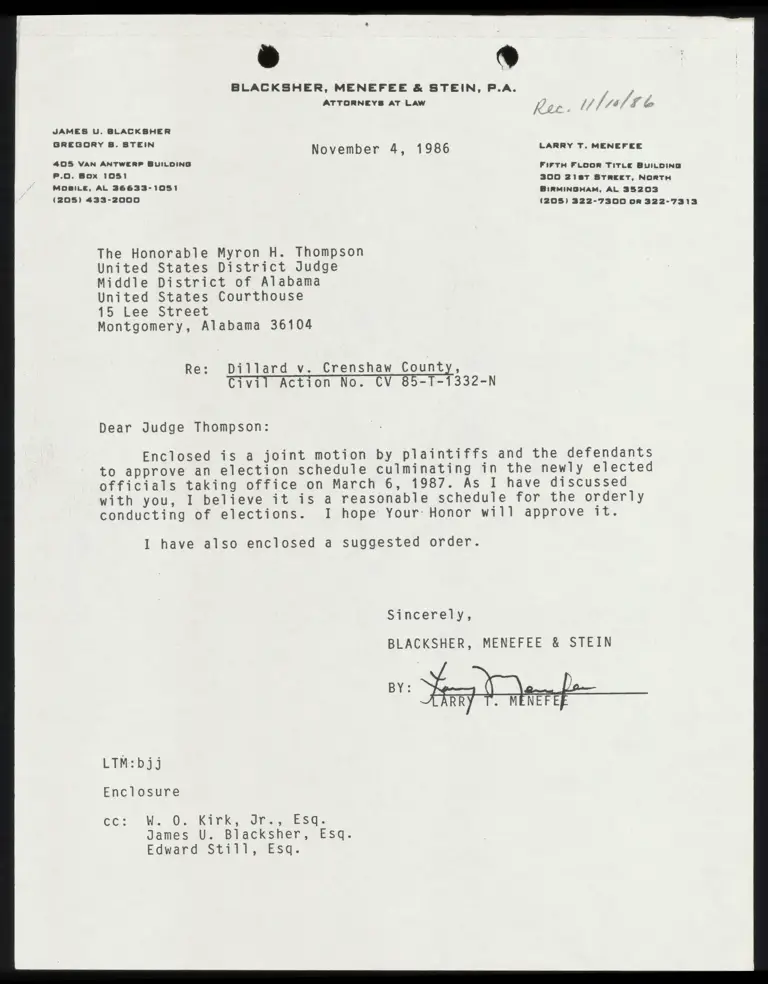

Correspondence from Menefee to Judge Thompson

Public Court Documents

November 4, 1986

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence from Menefee to Judge Thompson, 1986. 47c72ecd-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1632dfe9-c1a4-4a17-ac97-9bdead082ea6/correspondence-from-menefee-to-judge-thompson. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

i »

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT Law [Zn 1/7/48

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

GREGORY B. STEIN November 4 . 1 086 LARRY T. MENEFEE

FIFTH FLOOR TITLE BUILDING

300 2187 STREET, NORTH

BIRMINGHAM, AL 35203

(205) 322-7300 0R 322-7313

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

P.O. Box 1051

MOBILE, AL 36633-1051

(205) 433-2000

The Honorable Myron H. Thompson

United States District Judge

Middle District of Alabama

United States Courthouse

15 Lee Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Re: Dillard v. Crenshaw County,

Civil Action No. CV 85-T-1332-N

Dear Judge Thompson:

Enclosed is a joint motion by plaintiffs and the defendants

to approve an election schedule culminating in the newly elected

officials taking office on March 6, 1987. As I have discussed

with you, I believe it is a reasonable schedule for the orderly

conducting of elections. I hope Your Honor will approve it.

I have also enclosed a suggested order.

Sincerely,

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN

BY: /

RR . MENEFEF

LTM:bjj

Enclosure

cc: MW. OuKivk,:Jr., ESQ.

James U. Blacksher, Esq.

Edward Still, Esq.