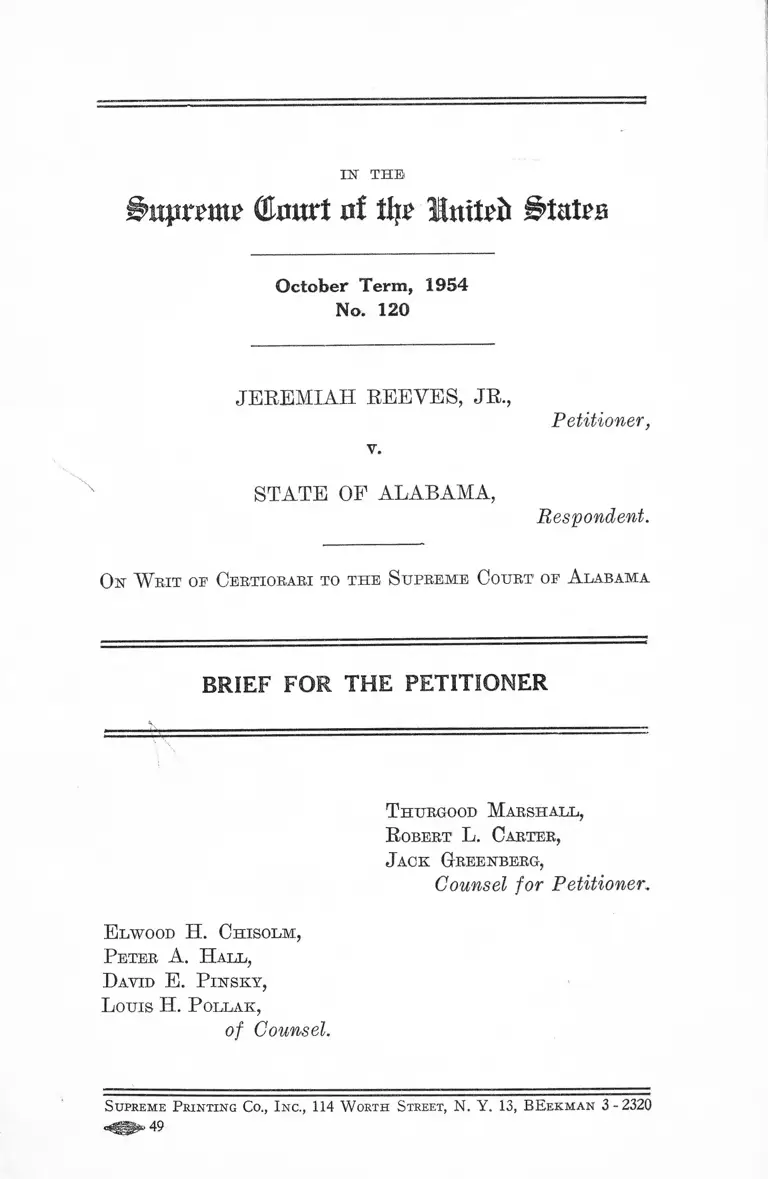

Reeves, Jr. v. Alabama Brief for the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reeves, Jr. v. Alabama Brief for the Petitioner, 1954. 42b0e3e2-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1639af32-da98-482a-95ed-d9e336198348/reeves-jr-v-alabama-brief-for-the-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

Bnptmt tourt uf % llnxtvh States

October Term, 1954

No. 120

JEREMIAH REEVES, JR.,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of A labama

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Jack Greenberg,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. Chisolm,

Peter A. Hall,

David E. P insky,

L ouis H. P ollak,

of Counsel.

S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BE ekm an 3-2320

49

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion Below ................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction.......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented........................................................... 2

Statutes Involved ............................................................... 3

Constitution of the United States—-14th Amend

ment ........................................................................... 3

Title 18 U. S. C. § 243 ................................................. 4

Ala, Const, of 1901 § 1 6 9 ................................ 4

Title 15, Code of Ala. § 320- (1940) .......................... 4

Statement ............................................................................ 5

I. Events Which Preceded The T r ia l ...................... 5

II. Preliminary Motions ........................................... 6

A. Exclusion of the P u b lic ................................... 6

B. Motion to Quash the Venire .......................... 7

III. Testimony At The Trial ..................................... 9

A. Commission of the Offense and Identifica

tion of A ccused................................................. 9

B. Inculpatory Statements and Confession: Tes

timony By Prosecutrix and Witness Clark .. 9

C. Petitioner’s Defense ....................................... 10

1. Petitioner’s Attempt to Testify Concern

ing Exaction of Confession ...................... 11

D. Rebuttal: Confession to Dr. B a za r ................ 13

IV. Motion for Mistrial Because Juror Chief of

Reserve Police Force ............................. 14

PAGE

11

Summary of A rgum ent..................................................... 15

I— A. Due process of law guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment was denied to petitioner—a

little-educated, mentally unstable Negro youth—-

by introduction into evidence of his “ confessions”

and “ inculpatory statements” made following sus

tained interrogation, punctuated by threats of

electrocution, while he was held incommunicado at

the State Penitentiary from Monday afternoon

through Wednesday morning near and frequently

in the very presence of the electric ch a ir .............. 18

B. Even if the confessions were not coerced as

a matter of law, due process was denied in that the

confession issue was not “ fairly tried and re

viewed” : The jury which heard the confessions

was not permitted to hear the relevant and im

portant testimony offered by petitioner concern

ing their exaction ....................................................... 24

C. The Supreme Court of Alabama erred in hold

ing that even if the confessions were coerced, the

decision in Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156 per

mitted affirmance because there was sufficient evi

dence apart from the confessions upon which the

conviction could have been b a sed ........................... 29

II— There was systematic exclusion of Negroes from

the venire in that the commissioners employed a

selection method whereby it was “ particularly

hard” for Negroes to become jurors if the com

missioners did not personally know them; commis

sioners knew fewer Negroes than whites; and al

though the Negro population of Montgomery

County is 43.6%, panels contained only 0% to

8.5% Negroes ............................................................. 33

PAGE

I l l

III—Arbitrary exclusion of the general public from

all phases of petitioner’s trial denied due process

of law .......................................................................... 39

Conclusion............................................................................ 49

Cases Cited

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143 ...................... 19,20

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 ....................35,37,38,39

Beauchamp v. Cahill, 297 Ky. 505, 180 S. W. 2d 423

(1944) .......................................................................... 42,43

Benedict v. People, 23 Colo. 126, 46 P. 637 (1896) .. 45, 46

Berger v. United States, 295 U. S. 7 8 ...................... 49

Brooks v. State, 178 Miss. 575, 173 So. 409 (1937) .. 26

Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443 .................................. 32

Bryant v. State, 191 Ga. 686, 13 S. E. 2d 820 (1941) 25

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ...................... 34,35,36,37

Catoe v. U. S., 131 F. 2d 16, 76 App. D. C. 292 (1942) 26

Cavazos v. State, 143 Tex. Cr. 564, 160 S. W. 2d 260

(1942) .......................................................................... 26

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 241 .................. 19, 20

Clay v. State, 15 Wyo. 42, 86 Pac. 17 (1906) .......... 26

Collier v. Hicks [1831], 2 Be. Ad. 663 ...................... 45

Commonwealth v. Blondin, 324 Mass. 564, 87 N. E.

2d 455 (1949) ............................................................. 41

Commonwealth v. Principatti, 260 Pa. 587, 104 Atl.

53 (1918) ..................................................................... 43,44

Comm. v. Sheppard, 313 Mass. 590, 48 N. E. 2d 630

(1943) cert. den. 300 U. S. 213 .............................. 26

Comm. v. Van Horn, 188 Pa. 143, 41 A. 469 (1898) 26

Cramer v. State, 145 Neb. 88, 15 N. W. 2d 323 (1944) 26

Daubney v. Cooper, 10 B. & C. 237 (1829) ................ 45

Davis v. United States, 247 F. 2d 394 (C. A. 8th,

1917)

PAGE

43

IV

PAGE

Diaz v. People, 109 Colo. 482, 126 P. 2d 498 (1942).. 25

Doyle v. Commonwealth, 100 Va. 808, 40’ S. E. 925

(1902) ........................................................................... 42

Dutton v. State, 123 Md. 373, 91 A. 417 (1914)... .41, 45, 46

Dyer v. State, 241 Ala. 679, 4 So. 2d 311 (1941)........ 25, 27

Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 U. S. 5 5 .............................. 19, 32

Gordon v. United States, 344 U. S. 4 1 4 ..................... 29

Grimmett v. State, 22 Tex. Cr. 36, 2 S. W. 631

(1886) ........................................................................... 42,44

Haley v. Ohio, 332 IT. S. 596 ............................. 19, 20, 25, 32

Hampton v. Commonwealth, 190 Ya. 531, 58 S. E. 2d

288 (1950) ................................................................... 46

Harris v. South Carolina, 338 U. S. 68...................... 19,20

Hearts of Oak Assurance Co., Ltd. v. A. G. [1931]

2 Ch. 370 ..................................................................... 45

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ......................................... 34, 35

Hogan v. State, 191 Ark. 437, 86 S. W. 2d 931 ........ 42, 43

Ingram v. State, 34 Ala. App. 597, 42 So. 2d 30 . . . . 20

Jackson v. Commonwealth, 193 Va. 664, 70 S. E. 2d

322 (1952) ................................................................... 26

Johnson v. State, 242 Ala. 278, 5 So. 2d 632, cert, den.

316 U. S. 693, 713 ....................................................... 30

Jones v. State, 23 Ala. App. 493, 127 So. 6 8 1 ............ 49

Keddington v. State, 19 Ariz. 457,172 P. 273 (1918).. 45, 46

Leach v. State, 245 Ala. 539, 18 So. 2d 289 (1944) . . . 48

Leyra v. D enno,------U. S . --------, 98 L. Ed. (Adv.

631) ..................................................................... 21,23,28,32

Logan v. Commonwealth, 308 Ky. 259, 214 S. W.

2d 279 (1948) ............................................................. 26

Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 IT. S. 596 ......................22, 23, 28, 32

McNahh v. U. S., 318 U. S. 332 ................................. 20

McPherson v. McPherson [1936] A. C. 177,1 D. L. R.

321 ............................................................................. 41,42,45

V

Mack v. State, 203 Ind. 355, 180 N. E. 279 ................ 26

Mahlikilili Dahlamini v. The King* [1942] A. C. 583

[P. C.] ........................................................................... 41, 45

Maliniski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401 ........20, 21, 22, 23, 32

Mooney v. Hollohan, 294 U. S. 103 .......................... 49

Moore v. State, 151 (la. 648, 108 S. E. 47 (1921) .. 46

Murphy v. United States, 285 F. 801 (C. A. 7th,

1923), cert. den. 261 U. S. 617 ............................... 26

Neal v. State, 86 Okla. Cr. 283,192 P. 2d 294 (1948) .. 44

Nelson v. State, 190 Ark. 1078, 83 S. W. 2d 539

(1935) ........................................................................... 25

Nicholson v. State, 38 Md. 140 (1873) ...................... 26

Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257 ........................................... 40,42,47

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 3 1 9 ........................... 41

People v. Dudgeon, 229 Mich. 26, 201 N. W. 355 (1924) 26

People v. Elmore, 277 N. Y. 397, 14 N. E. 2d 451, 124

A. L. R. 465 (1938) .................................................... 26

People v. Fox, 25 Cal. 2d 330, 153 P. 2d 729 (1944) . 25

People v. Hartman, 103 Cal. 242, 37 P. 153 (1894) 43

People v. Roach, 369 111. 95, 15 N. E. 2d 873 (1938) 26

People v. Yeager, 113 Mich. 228, 71 N. W. 2d 491

(1897) .......................................................................... 43,45

Pierson v. State, 99 Ala. 148, 13 So. 550! (1891) 47

Pollack v. State, 215 Wise. 200, 253 N. W. 560 (1934) 26

R v. Hamilton [1930], 30 S. R. N. S. W. 277; 47

N. S. W. W. N. 84 .................................................... 41,45

R v. Ladbrooke [1931], N. L. R. 475 ..................41,42,45

R v. Neff [1947], I. W. W. R. 640, 88 Can. C. C. 199 45

R v. Murray, 1 K. B. 391 (1951) ................................. 28

Rhoades v. State, 102 Neb. 750, 169 N. W. 433 (1918) 44

Robertson v. State, 64 Fla. 437, 60 So. 118 (1912) . . 45

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165 .......................... 21

PAGE

VI

Scott v. Scott [1913], A. C. 417 ................................. 41,45

Shapiro v. City of Birmingham, 30 Ala. App. 563,

10 So. 2d 38 (1942) ................................................. 48

Smith v. State, 77 Okla. Crim. 142, 140 P. 2d 237

(1943) ..................................... ..................................... 26

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 1 2 8 ..................................... 37

State v. Adam s,------R. I. ——, 121 Atl. 418 (1923) 26

State v. Adams, 100 S. C. 43, 84 S. E. 368 (1915) .. 44

State v. Auguste, 50 La. Ann. 488, 23 So. 612 (1898).. 21

State v. Bonza, 72 Utah 177, 269 P. 480 (1928)........ 44,45

State v. Brooks, 92 Mo. 542, 5 S. W. 257 (1 8 8 7 ).... 44, 47

State v. Callahan, 100 Minn. 63, 110 N. W. 342

(1910) .................................................................... . . . .4 2 ,4 4

State v. Cleveland, 6 N. J. 316, 78 A. 2d 560, 23

A. L. R. 2d 907 (1 9 5 1 )........... 26

State v. Collett (Ohio) 58 N. E. 2d 417 (1944)............ 26

State v. Crank, 105 Utah 332, 142 P. 2d 178, 170

A. L. R. 542 (1943) .................................................... 26

State v. Croak, 167 La. 92, 118 So. 703 (1928)............ 46

State v. Damm, 62 S. D. 123, 252 N. W. 7 (1 9 3 3 ).... 42, 44

State v. Genese, 102 N. J. L. 134, 130 Atl. 642 (1925). 42, 44

State v. Gibilterra, 342 Mo. 577, 116 S. W. 2d 88

(1938) ........................... 26

State v. Grover, 96 Me. 363, 52 A. 757 (1902)............ 26

State v. Hensley, 75 Ohio St. 255, 79 N. E. 462

(1906) ........................................................................... 42,44

State v. Hofer, 238 la. 820, 28 N. W. 2d 475 (1947)... 25

State v. Holm, 67 Wyo. 360, 224 P. 2d 500 (1 9 5 0 ).... 41, 46

State v. Johnson, 26 Idaho 609, 144 P. 784 (1 9 4 1 ).... 45

State v. Jordan, 146 Ore. 504, 30 P. 2d 751 (1934).. 26

State v. Keeler, 52 Mont. 205, 156 P. 1080 (1916)... 44

State v. Kerns, 50 N. D. 927, 198 N. W. 698 (1924).. 26

State v. Marsh, 126 Wash. 142, 217 P. 705 (1923) .. 44

State v. Miller, 204 Ala. 234, 85 So. 700 (1920) . . . . 39

State v. Nicholas, 62 S. D. 511, 253 N. W. 737 (1934) 26

State v. Nyhus, 19 N. D. 326, 124 N. W. 71 (1909) .. 46

PAGE

V l l

State v. Osborne, 54 Ore. 289, 103 P. 62 (1909) . . . . 42, 44

State v. Richards, 101 W. Va. 136, 132 S. E. 375

(1926) ................................... ....................................... 26

State v. Saale, 308 Mo. 573, 274 S. W. 393 (1925) .. 42

State v. Schabert, 222 Minn. 261, 24 1ST. W. 2d 846

(1946) ......................................................................... 26

State v. Scott, 209 S. C. 61, 38 S. E. 2d 902 (1946) .. 26

State v. Scruggs, 165 La. 842, 116 So. 206 (1928) .. 42

State v. Sherman, 35 Mont. 512, 90 Pac. 981 (1907) . . 26

State v. Smith, 62 Ariz. 145,155 P. 2d 622 (1944) . . . . 25

State v. Taylor, 119 Kan. 260, 237 Pac. 1053 (1925) . 26

State v. Vaisa, 28 N. M. 414, 213 Pac. 1038 (1923) .. 26

State y . Van Brunt, 22 Wash. 2d 103, 154 P. 2d 606

(1944) 26

State v. Van Vlack, 57 Id. 316, 65 P. 2d 736 (1937) .. 26

State v. Williams, 31 JSTev. 360, 102 P. 974 (1909) .. 26

State v. Willis, 71 Conn. 293, 41 Atl. 820 (1898) . . . . 25

State v. Wilson, 217 La. 470, 46 So. 2d 738 (1950)

aff’d. 341 U. S. 901 ............................................... 26

Stein y . New York, 346 U. S. 156 .............. 2,15,16, 201, 25,

29, 30, 31, 32, 49

Stroble v. California, 343 U. S. 181 ....................... . 23,32

Tanksley v. United States, 145 F. 2d 58 (C. A. 9th,

1944) ............................................................................ 43,47

The King v. Governor of Lewes Prison, ex parte

Boyle, 2 K. B. 254 (1917) ........................................ 43,45

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 5 1 0 ..................................... 48

Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62 . . . ................ 20

U. S. ex. rel. Almeida v. Baldi, 195 F. 2d 815 (C. A.

3d, 1952) .................................................................... 28

United States v. Bayer, 331 U. S. 532 ...................... 22

United States v. Kobli, 172 F. 2d 919 (C. A. 3d,

1944) ............................................................................ 42,43

United States v. Sorrentino, 175 F. 2d 721 (C. A. 3d,

1949)

PAGE

47

V l l l

Vernon v. State, 239 Ala. 593, 196 So. 96 (1940) .. 27

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 ..................................... 19, 20

Weaver v. State, 33 Ala. App. 207, 31 So. 2d 593

(1947) .......................................................................... 46

Williams v. State, 156 Fla. 300, 22 So. 2d 821 (1945) 25

Wilson v. Louisiana, 341 U. S. 901, a ff’g. 217 La. 470 21

Wilson v. U. S., 162 IT. S. 613 (1896) ...................... 26

Witt v. United States, 196 F. 2d 285 (C. A. 9th,

1952), cert. den. 344 U. S. 827 ............................. 26

Wynn v. State, 181 Tenn. 325, 181 S. W. 2d 332

(1943) .......................................................................... 26

Constitutions

United States Constitution, Sixth Amendment . . . . 41

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amend

ment ...................................................................2, 3,18, 33, 48

Alabama Const. Art. I, § 6 ........................................... 41

Alabama Const. § 169 ................................................... 4, 45

Arizona Const. A rt: II, Section 2 4 ............................. 41

Arkansas Const. Art. II, Section 1 0 ......................... 41

California Const. Art. I, Section 13 ......................... 41

Colorado Const. Art. II, Section 1 6 ............................. 41

Connecticut Const. Art. I, § 9 ..................................... 41

Delaware Const. Art. I, § 7 ......................................... 41

Florida Const., Declaration of Eights, Section 11 . . 41

Georgia Const. Art. I, § 2-105 ..................................... 41

Idaho Const. Art. I, § 1 3 ................................................. 41

Illinois Const. Art. II, § 9 ............................................... 41

Indiana Const. Art. I, § 1 3 ............................................. 41

Iowa Const. Art. I, Section 1 0 ................................... 41

Kansas Const. Bill of Rights § 10 ............................. 41

Kentucky Const. Section 11 ......................................... 41

Louisiana Const. Article I, § 9 ............................... .. 41

Maine Const. Art. I, Section 6 .................................... 41

Michigan Const. Art. II, § 1 9 ....................................... 41

PAGE

IX

Minnesota Const. Art. I, § 6 ........................... ............. 41

Mississippi Const. Art. 3, § 2 6 ..................................... 41, 45

Missouri Const. Art. I, § 18(a) ................................... 41

Montana Const. Art. I ll , § 1 6 ............................... . 41

Nebraska Const. Art. I, § 1 1 ....................................... 41

New Jersey Const. Art. I, Par. 10 .............. ................ 41

New Mexico Const. Art. II, § 1 4 ........................... 41

North Carolina Const. Article I, § 1 3 .......................... 41

North Dakota Const. Art. I, § 1 3 ............................... 41

Ohio Const. Art. I, § 1 0 ....................................... .. 41

Oklahoma Const. Art. II, § 2 0 ....................................... 41

Oregon Const. Art. I, § 1 1 ........................................... 41

Pennsylvania Const. Art. I, § 11.................................... 41

Rhode Island Const. Art. I, § 1 0 ................................. 41

South Carolina Const. Art. I, § 18 ............................ 41

South Dakota Const. Art. VI, § 7 ................................. 41

Tennessee Const. Art. I, § 9 ................................. .... 41

Texas Const. Art. I, § 1 0 ............................................. 41

Utah Const. Art. 1, § 12 ............................................. 41

Vermont Const. Ch, I, Art. 1 0 ....................................... 41

Washington Const. Art. I, § 22 ................................. 41

West Virginia Const. Art. I ll, § 1 4 ........................... 41

Wisconsin Const. Art. I, § 7 ......................................... 41

Statutes

18 U. S. C. § 243 ............................................................. 4, 33

15 Code of Ala. § 1 6 0 ..................................................... 20

15 Code of Ala. §320 .................................................... 4, 45

15 Code of Ala. § 389 ..................................................... 14

30 Code of Ala. § 2 4 ....................................................... 33

Ga. Code of 1933 Sec. 81-1006 ..................................... 45

Ky. Rev. States. § 455.130 (Baldwin’s 1943 Rev. Ed.) 42, 43

Mass. G-. L. (Ter. Ed.) c. 278 § 16A ...................... 45

Mich. Stat. Ann. (1935) Sec. 27.465 .......................... 43,44

Minn. Stat. Ann. (1947) §631.04 ............................... 42,44

PAGE

X

Nev. Comp. Laws Ann. Sec. 10654 (1929) ................ 41,42

Nevada Comp. Laws 1929 § 8404 ............................... 41

29 McKinney’s Cons. Laws of New York, Sec. 4 . . . 41, 45

Gen. Stats. No. Car. (Recompiled 1953) Sec. 15.166.. 42, 44

North Dak. Rev. Code of 1943 27-0102 ...................... 45

Code of Ya. 1950, Sec. 19-219 ..................................... 45

Wise. Stats. 1951 § 256.14 ........................................... 42,44

England: Children and Yonng Persons Act (1933)

(23 Geo. 5, C. 12) § 3 6 ............................................... 42

Other Authorities

170 A. L. R. 567 ............................................................... 27

Archbold’s Criminal Pleadings, Evidence & Prac

tice (31st Edn. 1943) 174 ......................................... 42, 45

8 Halsbury’s Laws of England (2d edn.) 526-527 . . 45

1950 Census of Population, Vol. II, Characteristics

of Population, Part 2, p. 2-87 ................................. 35

Note, 49 Col. L. Rev. 110 (1949) ................................. 40

Note 35 Cornell L. Q. 395, 399 (1949) ......................... 47

Note, The Supreme Court, 1952 Term, 67 Harv. L.

Rev. 91, 120 (1953) ................................................... 31

III Wigmore § 855 ......................................................... 23

III Wigmore § 866 ......................................................... 25

PAGE.

IN THE

§>iiprem? (Emtrt nf tty Inft^ Btntm

October Term, 1954

No. 120

------ ---------- o----- ------------

Jeremiah R eeves, J r .,

v.

Petitioner,

State of A labama,

Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of A labama

------------------------o----------------------

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 184)

is reported at 68 So. 2d 14.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Superior Court of Montgomery

County was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama on

August 6, 1953. Rehearing was denied November 27, 1953.

Time for filing petition for writ of certiorari was extended

to and including March 12, 1954 by order of the Chief Jus

tice dated February 17, 1954. Petition for writ of certiorari

and motion for leave to proceed in forma pauperis were

granted on June 7,1954. The printed record was received by

2

petitioner’s counsel on August 17,1954. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. § 1257(3), petitioner

having asserted in the courts below rights, privileges and

immunities conferred by the Constitution of the United

States.

Questions Presented

I

A.

Whether due process of law guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment was denied petitioner—a little-

educated, mentally unstable Negro youth—by introduction

into evidence of his “ confessions” and “ inculpatory state

ments” made following sustained interrogation—punctu

ated by threats of electrocution—while he was held in

communicado at the State Penitentiary from Monday

afternoon through Wednesday morning, near and fre

quently in the very presence of the electric chair.

B.

Whether, even if, arguendo, the confessions were not

coerced as a matter of law, due process was denied in that

the confession issue was not “ fairly tried and reviewed” ,

for the jury which heard the confessions was not permitted

to hear the relevant and important testimony offered by

petitioner concerning their exaction.

C.

Whether the Supreme Court of Alabama erred in pro

ceeding on the premise that even if the confessions were

coerced, it might properly, on the basis of Stein v. New

York, 346 U. S. 156, affirm the judgment of the trial court

because there was sufficient evidence apart from the con

fessions upon which the conviction could have been based.

3

I I

Whether there was systematic exclusion of Negroes

from the venire where there was a system of jury selection

based entirely upon the jury eommissoners’ personal

acquaintanceship; where they knew very few Negroes and

it was “ particularly hard” for Negroes to become jurors

if the commissioners did not know them; and where jury

panels contained only 0% to 8.5% Negroes in a county

where the Negro population is 43.6%.

I I I

Whether due process was denied in that the general

public was arbitrarily excluded from all phases of peti

tioner’s trial—especially when this ban included a time

when, as subsequent events proved, the public’s presence

was most necessary: during the voir dire when the Chief

of Police of the Montgomery Reserve Police Force became;

a juror, after having concealed his police affiliation which

was known to the State but unknown to petitioner.

Statutes Involved

Constitution of the United States—

14th Amendment.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State wherein they reside.. No

State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws.

4

Title 18 U. S. C. § 243.

Exclusion of jurors on account of race or color.—No

citizen possessing all other qualifications which are or may

be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for service as

grand or petit juror in any court of the United States, or

of any State on account of race, color, or previous con

dition of servitude; and whoever, being an officer or other

person charged with any duty in the selection or summon

ing of jurors, excludes or fails to summon any citizen for

such cause, shall be fined not more than $5,000. (June 25,

1948, c. 645, §1, 62 Stat. 696.)

Ala. Const, of 1901 § 169.

In all prosecutions for rape and assault with intent to

ravish, the court may, in its discretion, exclude from the

courtroom all persons, except such as may be necessary in

the conduct of the trial.

Title 15, Code of Ala. § 320 (1940).

Exclusion of public when evidence vulgar, etc.—In all

prosecutions for rape and assault with intent to ravish,

the court may, in its discretion, exclude from the courtroom

all persons, except such as may be necessary in the conduct

of the trial; and in all other cases where the evidence is

vulgar, obscene, or relates to the improper acts of the

sexes, and tends to debauch the morals of the young, the

presiding judge shall have the right, by and with the

consent and agreement of the defendant, in his discretion,

and on his own motion, or on the motion of the plaintiff's

or defendants, or their attorneys, to hear and try the said

cause after clearing the courtroom of all or any portion

of the audience whose presence is not necessary.

5

Statement

Petitioner has been sentenced to death following con

viction for the crime of rape without recommendation of

mercy (R. 184). The Supreme Court of Alabama has

affirmed (R. 194).

I. Events Which Preceded The Trial

During the summer of 1952, there were a number of

complaints of rape in Montgomery, Alabama (R. 44, 102,

104, 136). For a period of about six months the police

were unable to charge anyone, even though several sus

pects were arrested (R. 66), including petitioner who was

later released (R. 44-45, 104, 141). Petitioner is a 17-year-

old Negro with an eighth grade education (R. 116), who

comes from a poor family (R. 106-107) and who is mentally

unstable (R. 105, 121-122, 124). Finally, on Monday,

November 10, 1952, he was arrested once more (R. 135)

and was taken out to Kilby prison (R, 137) near the City

of Montgomery where he was held under circumstances

to be detailed below until he “ confessed” . Wednesday

morning, after his “ confession” , he was taken to the

City Jail.

It appears that several women who had been raped

or robbed were there to identify him and that four women

other than prosecutrix herein failed to do so (R. 44, 139).

Prosecutrix was told that petitioner confessed and was

given a copy of a statement purportedly constituting such

confession (R. 58, 64); thereupon she saw him, the only

Negro in the room, through a window (R. 65), entered the

room, and apparently identified him (R. 59).

In the presence of police officers a conversation ensued

in which, according to prosecutrix, petitioner identified her

house and described his entry (R. 59-60'), but was unable

to explain the reasons for his actions (R. 59). On Novem

6

ber 14, petitioner was indicted for six crimes on six indict

ments, three of them capital (E. 1, 44)1 * * among them was

the indictment upon which the conviction herein is based.

II. Preliminary Motions

A. Exclusion of the Public

Trial commenced November 26, 1952 in Montgomery.

At the outset, before motions were heard or the jury was

empanelled the judge ordered the courtroom cleared of

all persons except officials, jurors, and lawyers (E. 2, 10).

Petitioner objected and moved that the public be permitted

to attend (B. 2, 10, 19). He then moved that at least

newspapermen (B. 3, 11) and his relatives (B. 3, 14-15,

19) be admitted. The motion as to relatives was granted

(B. 3, 15); but that as to the press was at first denied

(B. 3, 11). Subsequently the press was admitted to hear

the actual taking of testimony (B. 22). Petitioner objected

to these exclusions on the ground that he was thereby

denied his right to a public trial as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment (B. 10-11, 14-15, 19-20). Follow

ing these objections petitioner moved that if the public

were to be excluded, it should be excluded only during

prosecutrix’s testimony on the ground that permanent ex

clusion from all phases of the trial denied due process of

law as guaranteed by the United States Constitution (B.

15, 20). This motion was denied (B. 15). Thus, the gen

eral public was excluded prior to the empanelling of the

jury and during the trial proper. Petitioner appealed

this denial of a public trial to the Supreme Court of Ala

1 A t the time he went to trial he made a motion for continuance

on the ground that he did not know for which of the three capital

offenses he was going to be tried (R . 50). It was denied (R . 45).

7

bama, urging Federal Constitutional grounds. It ruled

against trim but did not discuss the question in its opinion.2

E. M otion to Q uash the V enire

Petitioner moved to quash the venire on the ground

that Negroes had been systematically excluded from the

jury box in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment (R.

15, 20). The judge was also one of the jury commissioners,

and therefore recused himself (R. 15-16). He was replaced

by a Special Judge who tried the case from that point on

(R. 21).

Evidence revealed that the jury box contained about

five thousand cards (R. 38) bearing the names of all per-,

sons who had been called for jury service during at least

the past 18 years (R. 30), excepting those who had be

come ineligible or died (R. 30). The commissioners did

not known how many Negroes’ names were in the box and

would not estimate (R. 29, 39). However, one com

missioner testified that the largest number of Negroes

called at any term was three (R. 30). There have been

panels with a smaller number of Negroes (R. 30, 34-35)

and there have been terms with no Negroes at all (R. 35).

A panel consists of 50 persons although only 35 may

actually appear (R. 30). However, if there is a shortage

of jurors, additional ones may be called (R. 30). * IS

2 The Supreme Court of Alabama noted that the public had been

excluded, but merely mentioned this in connection with petitioner’s

motion to have his private stenographer admitted to the courtroom,

which was apparently held to have been waived at a later time be

cause the stenographer could not be located (R. 188-189). The

federal question was preserved in petitioner’s brief in the Supreme

Court of Alabama (see n. 5, infra), as follows:

“ P r o p o s i t i o n X V

A r b i t r a r y e x c l u s i o n o f a l l m e m b e r s o f t h e p u b l i c

W IT H O U T C LA SSIFIC A TIO N FROM A L L PH A SE S OF A RAPE TR IA L

IS A D E N IA L OF DUE PROCESS OF L A W U N DER T H E 1 4 t h

A M E N D M E N T OF T H E C O N S T IT U T IO N OF T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S .”

(Brief of Appellant, In the Supreme Court of Alabama,

Reeves v. The State of Alabama, p. 9.)

8

The commissioners selected jurors entirely from their

personal acquaintance with individuals or organizations

(R. 28-29, 36-37). They had obtained lists of names from

almost every white club in the County (R. 33), but they

knew few Negroes (R. 29, 37) and did not know or go to

Negro clubs (R. 33, 36). Only one of them could recall a

Negro organization which he had contacted, long ago in

the past, and he was not sure of its name (R. 33-34). The

Commissioners testified that they did not discriminate (R.

34), that they sought “ high class” or “ good” Negroes

(R. 29, 36, 38) for jury service and never rejected a man

because of his race (R. 29). There is testimony that

several Negroes had been asked to submit names for the

box (R. 36-37, 40, 42), although it does not appear that

names ever were submitted by these persons (R. 36, 37,

40, 42), except on one occasion two or three years ago

(R. 29), and that a public meeting was held at the start of

World War II, attended by “ high class” Negroes, and

names were requested there (R. 38). Two Negroes testi

fied that they had served on juries (R. 40, 41) and that

other Negroes had served with them. However, one com

missioner testified that it is “ particularly hard” for

Negroes to get on the jury without the commissioners

knowing them (R. 29).

Petitioners moved on two occasions to examine the

cards in the box to ascertain the number of Negroes who

had been selected and to test the Commissioners’ general

assertions by cross-examination (R. 27, 34). Petitioner

also sought to interrogate the commissioners concerning

the voting list to ascertain whether it had been employed,

as required by statute, in selecting jurors (R. 31, 39).

These requests were denied (R. 27, 31, 34, 39). The

trial court (R. 43) and the Supreme Court of Alabama

(R. 187) concluded that there was no evidence to sustain

petitioner’s motion, and that there was therefore no viola

tion of the Federal Constitution.

9

III. Testim ony At The Trial

A . Com m ission o f the O ffense and

Identification o f A ccu sed

Prosecutrix testified that her assailant entered her home

July 28, compelled her to have intercourse (R. 52) and beat

her unconscious (R. 62). She identified her assailant in

most general terms as a Negro, seventeen to twenty-five

years of age, five feet nine and a half to five feet ten inches

in height, slightly taller than her husband, 130 to 150

pounds in weight (R. 62, 65), without a mustache (R. 65),

wearing a dark blue shirt with a yellow-gold design and a

straw hat (R, 52). Petitioner resembles even this general

description only in that he is a Negro. There is uncon-

tradicted testimony that he has always had a mustache

since he was fourteen (R. 150, 151, 154, 155), that he.has

never owned the articles of clothing prosecutrix described

(R. 107, 150), that he is five feet seven inches tall (R. 150)

and that he was under seventeen at the time of the alleged

offense (R. 135). The State seized all of petitioner’s be

longings (R. 102, 107) but produced no items of clothing

like those prosecutrix described.

B. Inculpatory Statements and Confession:

Testimony By Prosecutrix and Witness

Clark

Prosecutrix testified concerning the statements made

by petitioner to her at the City Jail (R. 59-60), and also

testified that the solicitor had told her that petitioner

confessed and that he showed her petitioner’s confession

(R. 58, 64-65). Petitioner objected to prosecutrix’s testi

mony concerning the incriminating statements on the

ground that they had been obtained by coercion which denied

due process of law (R. 55-56, 58-59). A hearing was held

without the presence of the jury in which petitioner sought

to show that he had been held incommunicado at Kilby

from 2:00 P. M. on Monday until Wednesday morning

10

when he confessed, at which time he was taken to the City

Jail to be identified by prosecutrix. He sought to show

that at Kilby he had been continuously questioned in the

presence of the electric chair, had been kept in the room

next to the electric chair, that he was offered the hope

and promise that if he confessed he would not be electro

cuted, hut that if he did not confess he would be electro

cuted. Petitioner also sought to introduce testimony con

cerning his age and education (R. 55-56, 58-59).

The judge held that the proffered testimony was inad

missible because it related to events up to the time that

petitioner was taken to the City Jail to make the incrimi

nating statements, but did not concern his treatment when

he gave the statements at the City Jail (R. 58-59). Prose

cutrix then proceeded with her testimony before the jury

(R. 59-60, 64-65).

Witness Clark testified that not far from prosecutrix’s

home at the time of the offense he gave a ride to a person

who fit prosecutrix’s description of her assailant (R. 71-

73) and that this person was petitioner. He then testified

to an inculpatory statement petitioner made to him at the

City Jail on November 17 (R. 74-75), in which petitioner

purportedly recognized him and acknowledged that he had

been Clark’s passenger. Petitioner objected to the intro

duction of this statement on the ground that it was the

product of the coercion used against him at Kilby (R. 74).

The Court overruled the objection on the same ground

that it overruled the earlier objection to the prosecutrix’s

testimony (R. 74), and refused to hear testimony on it.

C. Petitioner’s Defense

Petitioner took the stand to deny that he committed the

crime and to testify that he was playing dominoes at the

time the offense was committed (R. 142-143). Another

witness who participated in the domino game corroborated

the alibi (R. 126-127). There was testimony that peti

11

tioner did not fit the description given by prosecutrix

(Compare R. 52, 62-65 with R. 106, 134, 150, 151, 154, 155).

In the alternative there was a defense of insanity concern

ing which a series of lay witnesses testified that petitioner

was mentally unstable and in their opinion insane (R. 105,

121-122,124). There was also testimony of his good reputa

tion (R. 152, R. Orig. 175, 200, 201, 202).3

1. Petitioner’s Attempt to Testify Concern

ing Exaction of Confession.

Petitioner sought to testify during his own case con

cerning the treatment he received at Kilby before he con

fessed and made the incriminating statements in the

presence of prosecutrix, witness Clark and the police (R.

138, 139-141).

After petitioner had testified briefly concerning occur

rences at Kilby on Monday, the Court stopped him on the

ground that the testimony was irrelevant (R. 138-139, 140-

141). Petitioner, thereupon made the following proffer

(R. 140):

“ Mr. McGee: To show the defendant, a seven

teen year old negro boy, who quit school in the 8th

grade, was arrested at approximately 2:10 P.M. on

November 10th, 1952, and was carried within a period

of about fifteen minutes from then to the State

Penitentiary, Kilby Prison, Montgomery County,

Alabama, where he was held incommunicado by State

and City officers and questioned continuously the

rest of the afternoon, and then permitted to sleep

only a short while, some fifteen or twenty minutes;

he was then carried into the next room where the

electric chair was and questioned some more by the

Deputy Warden O. R. Dees and accused of having

3 R. Orig. indicates pages of the original record which were not

printed.

12

made various kinds of attacks on some six white

women of Montgomery County, Alabama. 0. R.

Dees further told him that if he didn’t confess to

these crimes that all the women would identify him

and he was going to the electric chair. And that if

he would confess that he would keep him out of the

chair. After questioning him all night he was finally

permitted to go to bed until the following morning,

Tuesday. Tuesday morning early the officers again

began a series of constant questioning all day Tues

day and part of Tuesday night. Then he was per

mitted to go to bed. That on Wednesday morning

he was again questioned. And all the time the

officers were telling him if he didn’t confess to

these crimes he would go to the electric chair, and

if he did he would keep him out of the chair, until

sometime finally Wednesday morning he agreed to

confess to all of these crimes they had been accus

ing him. That he was then carried by the State

Officers of Montgomery County to Police Head

quarters and there held by the Montgomery County

Police and City Police officers until the prosecutrix

in this case was permitted to view him.

“ And I move the Court to permit me to prove

these allegations, and in order to go to the credibility

of the statement which is alleged he made in her

presence while he was held.

“ And I move the Court to permit me to do so on

the ground that a failure by the Court to permit me

to do that is a denial to the defendant of his con

stitutional rights as guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.”

The motion was denied (R. 141).

13

Thus, the jury was denied substantial and crucial testi

mony concerning the entire pattern of coercion, and knew

nothing about what happened at Kilby Tuesday and Wed

nesday.

D. Rebuttal: Confession to Dr. Bazar

In rebuttal the state presented the testimony of Dr.

Bazar, a psychiatrist, whom they had caused to examine

petitioner. Dr. Bazar concluded that petitioner was not

legally insane, and testified that while examining petitioner

on November 13, petitioner confessed to him (R. 165).4

Petitioner objected to testimony of the confession as hav

ing been obtained in violation of the Constitution and

exacted by the same coercion which produced the earlier

confession. He made an offer of proof which was refused

(R. 164-165). The Court overruled him.

Thus attempts to introduce testimony concerning the

coercion of inculpatory statements and confessions were

rebuffed on four occasions, each time over a Federal Con

stitutional objection. Neither the Court nor the jury heard

the testimony. The Supreme Court of Alabama sustained

the trial court’s actions as to the confessions and held that

defendant’s rights under the Federal Constitution were

not infringed (R. 191, 192, 193). It wrote that there was

“ nothing to show that the trial court’s action in admitting

them was manifestly wrong or that defendant’s rights

under the Federal Constitution were infringed’ ’ (R. 193).

4 Dr. Bazar states that he saw petitioner twice; on November

13th at Kilby and on November 20th at the County Jail (R. 161).

He does not specify on which occasion the confession was made.

Petitioner, however, admits confessing at Kilby and denies making

any confession at the County Jail (R. 144).

14

IV. Motion for M istrial B ecause Juror C h ief o f

R eserve P olice F orce

Shortly before the trial ended petitioner informed the

court that he had just discovered that one of the jurors,

Jack Page, was Chief of Police of the Reserve Police Force

of Montgomery and had been active in this case. Peti

tioner thereupon moved for a mistrial on the ground that

this juror had answered falsely on voir dire. Petitioner

further averred that the juror was Chief of the Montgom

ery Reserve Police Force organized for the purpose of

tracking down “ alleged Negro rapists” and night burglars,

and that he had been active in this case (R. 172-173), and

asked to call Page as a witness in support of this motion.

The state admitted that Page was a member of the Police

Force and had been working on cases, but denied that he

had worked on this case. The Solicitor stated:

“ There was no question asked whether any mem

ber of the panel was a member of the Reserve

Police Force. I am a member of the Naval Reserve

and that doesn’t enter into my qualifications. He

has been working on cases, but has not worked on or

had any connection with this case, and didn’t have

any opinion or bias in this case” (R. 172).

The trial court denied a hearing on the matter and over

ruled the objection on the ground that the jury had already

been qualified (R. 173). The Supreme Court of Alabama

sustained the trial court (R. 193).

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama appears

at page 185 of the Record.5

5 It should be noted that pursuant to Title 15, Code of Alabama,

§389 (1940), this Record contains no assignments of error. The

matters which petitioner raised in the Supreme Court of Alabama

were presented in his brief according to State practice.

15

Summary of Argument

The introduction into evidence of petitioner’s “ con

fessions” and “ inculpatory statements” denied due process

of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment because

they were obtained following sustained interrogation and

threats of electrocution while petitioner-—a little-educated

mentally unstable Negro youth—was held incommunicado

at Kilby State Penitentiary from Monday afternoon

through Wednesday morning, near and frequently in the

very presence of the electric chair. The fact that the in

culpatory statements to the prosecutrix, witness Clark and

Dr. Bazar were made at the nearby City Jail shortly fol

lowing the coercion at Kilby does not absolve the State

of the consequences of the coercion at Kilby. There is a

presumption that petitioner remained under the influence

of the coercion; and this presumption was not dispelled

by the evidence which, indeed, indicates no significant

change in his situation.

Even if the confessions and inculpatory statements

made at the City Jail were not coerced as a matter of

law, petitioner was denied due process in that the con

fession issue was not “ fairly tried and reviewed.” Peti

tioner was not permitted to testify before the jury con

cerning the pattern of coercion which exacted the confession

at Kilby State Penitentiary, and concerning the confessions

made at the City Jail which followed the confession at

Kilby. Thus, the jury heard the confessions and the

State’s side of the story that they were voluntary, but

was denied relevant and important defense testimony con

cerning how the confessions were coerced.

The Supreme Court of Alabama erred in holding that

even if the confessions were coerced this Court’s opinion

in Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156 made reversal unneces

sary, because there was evidence apart from confessions

16

upon which the conviction could be sustained. But this

Court’s opinion in the Stein case was concerned with a

quite different problem: (1) In the Stein case the con

fession was held not to have been coerced. (2) This Court

then went on to say that where a confession is not coerced

as a matter of law, an appellate court need not reverse

even though it is possible that the jury might have found

it coerced as a matter of fact and convicted defendant

nevertheless. (3) In the Stein case defendant had been

permitted to put on evidence relevant to the issue of

coercion. Here petitioner was not permitted to do so.

(4) In the Stein case petitioner requested an instruction

for acquittal if the jury found the confession coerced.

That issue is not involved here. This Court would not

have upset its long standing rule that where a conviction

is tainted by a coerced confession the conviction must

fall, without saying so explicitly.

There was systematic exclusion of Negroes from juries

in Montgomery County, caused by a system, of jury selec

tion which relied wholly upon the jury commissioners’ per

sonal acquaintanceship, when the commissioners knew few

Negroes. Thus, as one commissioner testified, it was “ par

ticularly hard ” for Negroes to become jurors. As a result,

although the Negro population of Montgomery County is

43.6%, no more than 3 Negroes or (a range of 0% to 8.5%

of any panel) ever appeared on any jury panel.

Arbitrary exclusion of all portions of the general public

from the entire trial denied petitioner’s right to a public

trial as guaranteed by the due process clause of the United

States Constitution. The right to a public trial is recog

nized uniformly throughout the English speaking world.

The only limitations upon it which are generally admitted

are those which contribute to the fair and orderly admin

istration of justice. Thus, children and unruly persons

may be excluded, or the general public may be excluded for

17

a limited time during, for example, the testimony of a

prosecutrix who cannot express herself before a large

audience. Cases upholding the exclusion of the entire pub

lic from all phases of a criminal case, over a defendant’s

objection, have been found in but a few states. Such arbi

trary exclusion is unrelated to the orderly and fair admin

istration of justice, and even to the State’s avowed purpose

of protecting the morals of the public. If petitioner’s mo

tion to limit the exclusion of the public only to the time of

prosecutrix’s testimony had been granted, petitioner’s

rights would have been protected. Certainly, the exclusion

of the public during the empanelling of the jury had no

reasonable relation to any permissible purpose and may

have seriously prejudiced petitioner, for without petition

er’s knowledge—although the State knew of it—the Chief

of the Reserve Police Force of Montgomery County became

a member of the jury after having failed to disclose his

police affiliation on voir dire.. Thus petitioner was tried

by a juror with an interest in his conviction. One of the

principal reasons for the public trial right is that it is

designed to prevent miscarriages of justice abetted by con

cealment of this sort.

These were not merely individual fatal flaws in peti

tioner’s trial, but considered cumulatively these errors

robbed petitioner’s trial of any semblance of the open

quality which characterizes judicial proceedings in the

United States and, indeed throughout the English speak

ing world.

18

ARGUMENT

I

A .

Due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment was denied to petitioner— a little-edu

cated, mentally unstable Negro youth— by introduction

into evidence of his “ confessions” and “ inculpatory

statements” made following sustained interrogation,

punctuated by threats of electrocution, while he was

held incommunicado at the State Penitentiary from

Monday afternoon through Wednesday morning near

and frequently in the very presence of the electric

chair.

The confessions 6 which were introduced into evidence

were coerced as a matter of law. There is no controversy

as to the facts because the issue arises upon proffers

(R, 55-56, 58-59, 74, 164-165, 139-141), which were rejected

as irrelevant by the trial court and as irrelevant and in

sufficient in law by the Alabama Supreme Court. Nowhere

are the allegations denied by the State.7 Indeed, although

6 There are involved inculpatory statements which amounted to

confessions (R . 59-60, 75, 190-191), a confession (R . 165-166) and

testimony that there had been a confession (R . 58, 64-65). For

brevity, petitioner refers to them as the confessions, except where

it is necessary to distinguish among them.

7 There is some testimony of a general nature apparently intro

duced to exculpate the State from a charge of coercion, but it does

not amount to denying any of petitioner’s allegations: There is testi

mony by prosecutrix that she knew nothing of what occurred prior

to petitioner’s statements at the City Jail (R . 57), that she saw no

one threaten petitioner there (R. 55, 57) ; by the Director of the

State Department of Toxicology and Criminal Investigation that no

one coerced petitioner between 2 :30 and 3 :00 P. M. on November

11th (R . 92-93) ; by petitioner that the Solicitor told petitioner he

would help him (R . 143) ; by the Prison Classification Officer that

the Solicitor told petitoiner he could make him no promises and

would get him a lawyer if he didn’t hire one (R . 159) ; by Captain

J. Lewis Miller of the detective force of Montgomery that in his

presence no one coerced petitioner at the City Jail (R . 156).

19

testimony in support of the proffers was forbidden, there

is incidental corroboratory testimony in the record.8

Prior to the introduction of the confessions petitioner

in these proffers offered to prove the existence of many

facts each of which this Court frequently has held to be

relevant on the issue of coercion:

That he was a Negro,9 seventeen years of age,10 had an

eighth grade education,11 that he was held incommunicado

8 On cross-examination, S. E. Sellers, City Detective, testified

that he was at Kilby on November 10th and was with defendant for

twenty to forty minutes, that during this time Warden Dees was

present, that petitioner was in the room next to the electric chair, but

that he (Sellers) did not hear what was said (R . 99-100). Petition

er’s mother testified that she had not been permitted to see him until

Wednesday afternoon (R . 102-103). Petitioner’s father testified

he had not been permitted to see him until Thursday (R. 116-117).

There was testimony by the Prison Classification Officer that peti

tioner was held without a charge lodged against him (R. 160).

Before petitioner’s testimony was interrupted, he testified as to his

age (R . 135) ; that he had been threatened in a number of ways by

the officers who picked him up, including with the electric chair

(R. 137-138) ; that he was held incommunicado (R . 137) ; that on

Monday he was questioned till dark, went to sleep and was then

awakened and taken into the room with the electric chair (R . 138) ;

that Warden Dees threatened him with the chair if he did not con

fess (R . 138). That he did not see his parents until 5:00 P. M.

Wednesday (R . 141) ; that he was frightened (R . 142).

9 In ascertaining whether a confession is coerced, this Court gives

weight to the fact that defendant is a member of an unpopular racial

group. Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 237, 241; Ward v.

Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555; Harris v. South Carolina, 338 U. S. 68,

70, as part of considering his “ condition in life” Gallegos v. Nebraska,

342 U. S. 55, 67. See, Mr. Justice Jackson’s dissenting opinion in

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143, 156, 173.

10 Whether defendant is mature or immature is important in

evaluating whether a confession has been coerced. Haley v. Ohio,

332 U. S. 596.

11 The degree of education which a defendant has had is an

important factor in evaluating whether a confession has been coerced.

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555; Harris v. South Carolina, 338

U. S. 68, 70.

20

at Kilby from about 2:00 P. M. on Monday the 10th,

through 5:00 P. M. on Wednesday the 12th, that he was

denied permission to talk to or phone anyone, that friends

and relatives had been forbidden to see him or speak to

him,12 that he was continuously questioned and abused,13

was kept next to the room with the electric chair, that he

12 Holding petitioner incommunicado was not only in probable

violation of Alabama law, 15 Code of Ala. § 160 (1940), Ingram v.

State, 34 Ala. App. 597, 601, 42 So. 2d 30 (1949), but contrary to

the almost universal rule. See statutes collected in McNabb v. U. S.,

318 U. S. 332, 342, fn. 7. Although there has been some controversy

over whether this alone should vitiate a confession it is at least a

serious factor to be weighed, because, “ [t]o delay arraignment,

meanwhile holding the suspect incommunicado, facilitates and usually

accompanies use of ‘third degree’ methods. Therefore [this Court]

regard[s] such occurrences as relevant circumstantial evidence in the

inquiry as to physical or psychological coercion.” Stein v. New

York, 346 U. S. 156, 187. See also Harris v. South Carolina, 338

U. S. 68, 71; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62, 64; Ward v.

Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555; Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143,

152; Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401, 412, 417; Turner v.

Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62, 66, 67.

13 If petitioner had been able to develop this line of inquiry he

would have been able to show the nature and extent of the interroga

tion. Questioning began after 2 :00 P. M. on the afternoon of Mon

day the 10th (R. 140) and continued until dark (R . 138) ; petitioner

then slept for fifteen or twenty minutes and was awakened and taken

into the room with the electric chair (R . 140) ; he was questioned

there all night (R. 140) ; early Tuesday morning he was awakened

and he was then questioned all day Tuesday and part of Tuesday

night (R . 140). Later Tuesday night he slept. Wednesday morning

he was questioned again, until he confessed (R . 140). Questioning

was of long duration, and was conducted and threats were made by a

series of officers (R. 74, 140, 164).

Continuous interrogation has been deemed an important factor in

evaluating whether a confession has been coerced, Chambers v.

Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 231; Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143, 154; Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S.

596, 600; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62, 64.

21

was taken into the electric chair room and threatened

with death in the electric chair14 and was offered the

hope and promise that if he confessed he would save his

life from the chair ;15 that while held there he was stripped

naked and photographed, and had his spine tapped and

blood taken from his arm against his will.16 Further in

quiry would have developed that petitioner was mentally

unstable (R. 105, 121-122, 124), and came from a poverty

stricken home (R. 107), and was therefore even more likely

to capitulate than the ordinary otherwise disadvantaged

seventeen year old Negro youth in his plight.

Almost every aspect of the treatment which petitioner

received at Kilby is found in the leading cases in this Court

condemning exaction of involuntary confessions. Virtually

each form of the pressure employed has been condemned

by this Court.17 In combination, petitioner submits, they

formed an irresistible pattern.

Mute testimony that petitioner was subjected to illegal

coercion at Kilby is given by the State’s unwillingness

14 In Wilson v. Louisiana, 341 U. S. 901, aff’g 217 La. 470, 46

So. 2d 738, petitioner had been brought into the electric chair room

in the course of obtaining a confession from him. However, the

Louisiana Court noted that the electric chair was not visible and

that there was no evidence that it had the effect of intimidating peti

tioner there. Cf. State v. Auguste, 50 La. Ann. 488, 23 So. 612 (1898)

(prisoner interrogated in presence of gallows, confession held

coerced).

15 A lighter penalty is one of the inducements which was offered

in Leyra v. Denno, ------ U. S . --------, 98 L. ed. (Adv. 631, 633). As

Mr. Justice Minton wrote, at p. 645 (concerning the first confession

in Leyra) : such “threats, cajoling, and promises of leniency * * * to

induce petitioner to confess were soundly condemned * * * ”

16 The effect of similar treatment was noted in Malinski v. New

York, 324 U. S. 401, 403, 407. Also see Rochin v. California, 342

U. S.' 165, 173, 174, 179.

17 Footnotes 9 through 16 cite only some of the cases in this

Court in which it has been held that confessions were coerced because

of practices such as those used here.

2 2

even to attempt to introduce a “ confession” (R. 58, 64-65)

which was apparently made before he was removed to the

City Jail.

Transfer of petitioner from one jail to another on

Wednesday morning so that he might be identified by

prosecutrix clearly did not alleviate his condition. No

appreciable time had elapsed.18 He was still in police

custody. He was still incommunicado.19 He labored under

the crushing burden of having already confessed.20 He

was confronted by prosecutrix accusing him of a frightful

crime. His age, education and mental condition were no

different. It does not appear that any significant change

in circumstances occurred. Neither did any significant

change in circumstances occur prior to his confessing to

the psychiatrist,21 or to witness Clark.22 But even apart

from the factual showing that his situation was the same,

such a confession remains coerced as a matter of law

18 The time gap cannot be ascertained with precision, but it was

no more than a few hours. W e know petitioner was questioned on

Wednesday morning at Kilby (R . 140), that the ride from Mont

gomery to Kilby is about 15 minutes (R. 140) ; that prosecutrix went

out to the City Jail at 11:00 (R . 57).

19 His parents were not permitted to see him until late Wednes

day afternoon (R . 102-103, 116,117, 141).

20 As Mr. Justice Jackson wrote in United States v. Bayer, 331

U. S. 532, 540, once an accused has confessed, “ no matter what the

inducement, he is never thereafter free of the psychological and prac

tical disadvantages of having confessed.” In U. S. v. Bayer, the

Court weighed a time lapse of six months and concluded that this

length of time in conjunction with only a modicum of restraint vitiated

a previous inducement to confess. See Mr. Justice Rutledge’s con

curring opinion in Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401, 420, 428;

Mr. Justice Murphy’s dissenting opinion in Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322

U. S. 596, 605, 606.

21 A day had elapsed and he had seen his mother (R . 144, 102-

103).

22 Clark thinks he saw petitioner on the 17th (R . 75).

23

unless the State comes forward to overcome the presump

tion created by the undisputed facts. Mr. Justice Minton

stated the general rule when he wrote:

“ As in the case of other forms of coercion and

inducement, once a promise of leniency is made a

presumption arises that it continues to operate on

the mind of the accused. But a showing of a variety

of circumstances can overcome that presumption.

The length of time elapsing between the promise

and the confession, the apparent authority of the

person making- the promise, whether the confession

is made to the same person who offered leniency,

and the explicitness and persuasiveness of the in

ducement are among the many factors to be

weighed. ’ ’ Leyra v. Denno,------U. S .------- , 98 L. ed.

(Adv. 631, 645, 647).23

The State produced nothing. The record shows that there

was no change in conditions that makes any legal differ

ence.

Because of the introduction into evidence of these

coerced confessions, or any of them,24 the judgment below

must fall.

23 III Wigmore § 855, states: “ * * * the general principle is

universally conceded that the subsequent ending of an improper in

ducement must be shown ; i. e. it is assumed to have continued until

the contrary is shown.” (Italics in original). See also Mr. Justice

Rutledge’s concurence in Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S; 401, 420,

428; Mr. Justice Murphy’s dissenting opinion in Lyons v. Oklahoma,

322 U. S. 596, 605, 606.

24 Stroble v. California, 343 U. S. 181, 190; Malinski v. New

York, 324 U. S. 401, 402, 404; Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 U. S. 596,

597 note 1.

24

B.

Even if the confessions were not coerced as a

matter of law, due process was denied in that the con

fession issue was not “ fairly tried and reviewed” : The

jury which heard the confessions was not permitted to

hear the relevant and important testimony offered by

petitioner concerning their exaction.

In Point A, supra, petitioner demonstrated by undis

puted facts that this conviction rests upon confessions

obtained contrary to due process of law. Petitioner sub

mits in this section that error was compounded by the

trial court’s refusal to permit the jury to hear evidence of

how the confessions were exacted.

Following the State’s case, petitioner began to testify

concerning the pattern of coercion which commenced at

Kilby on Monday and continued through Wednesday morn

ing when he confessed, just prior to being brought before

prosecutrix. The court stopped him before he completed

testifying about Monday. Thereupon petitioner made the

proffer which appears on page 11, supra.

The trial court refused to permit the jury to hear this

testimony on the ground that it did not concern events

in the City Jail (E. 138, 140,141). On review the Supreme

Court of Alabama upheld the trial court.25 Therefore,

neither the trial court nor the jury nor the Supreme Court

fairly considered the pattern of coercion preceding the

confessions. Petitioner submits that by this procedure he

25 The Alabama Supreme Court considered State testimony con

cerning events at Kilby on Tuesday the 11th (R. 192). It deemed

the events of the 11th relevant at least for purposes of the State’s

case, although defense testimony concerning the 11th had been ex

cluded as irrelevant.

25

was denied his fundamental, constitutional right to have

the confession issue “ fairly tried and reviewed.” 26

The law has long recognized that prisoners may con

fess for any one of or a combination of many complex

reasons. In some cases the psychology of the problem

may be clear; in others obscure. But, in any case, it is

fundamental “ * # * that confessions vary in value accord

ing to the circumstances in which they are made. ’ ’ 27

The fundamental importance of the right to present evi

dence to the jury on the issue of voluntariness is demon

strated by the fact that in every American jurisdiction,

once the jury hears a confession the defendant is permitted

to put on testimony of circumstances surrounding its exac

tion.28 Most jurisdictions instruct the jury to reject a

28 Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 1S6, 182. See also Mr. Justice

Burton’s dissent in Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596, 607, 615: “ Due

process of law under the Fourteenth Amendment requires that the

States use some fair means to determine the voluntary character of

a confession * * * ”

The issue of the right to testify concerning the exaction of a con

fession was raised in the Stein case, at pp. 173-175, but this Court

held that it was not properly presented. Petitioners alleged that as

a practical matter they had been prevented from presenting evidence

of coercion, because if they had testified on the confession issue they

would have opened themselves up to general cross-examination. The

State denied this. At any rate petitioners there did not take the

stand and then object to cross-examination when, in their opinion,

it exceeded the bounds of due process, and therefore the issue was

not before this Court.

In the case now at bar there was a flat refusal to permit petitioner

to testify concerning relevant and weighty facts bearing on the con

fession.

27 III Wigmore § 866.

28 Dyer v. State, 241 Ala. 679, 4 So. 2d 311 (1941) ; State V.

Smith, 62 Ariz. 145, 155, 155 P. 2d 622 (1944) ; Nelson v. State,

190 Ark. 1078, 1082, 83 S. W . 2d 539 (1935); People v. Fox, 25

Cal. 2d 330, 340, 153 P. 2d 729 (1944) ; Diaz v. People, 109 Colo.

482, 485-486, 126 P. 2d 498 (1942) ; State v. Willis, 71 Conn. 293,

314, 41 Atl. 820 (1898); Williams v. State, 156 Fla. 300, 303, 22 So.

2d 821 (1945) ; Bryant v. State, 191 Ga. 686, 711, 13 S. E. 2d 820

(1941 ); State v. Hofer, 238 la. 820, 829, 28 N. W . 2d 475 (1947);

26

confession which it finds to be coerced; some instruct it

to consider coercion in determining what weight to give

28 (Continued)

State v. Van Vlack, 57 Id. 316, 342-343, 65 P. 2d 736 (1937);

People v. Roach, 369 111. 95, 96, 15 N. E. 2d 873 (1938); Mack v.

State, 203 Ind. 355, 373, 180 N. E. 279 (1932); State v. Taylor,

119 Kan. 260, 262, 237 Pac. 1053 (1925); Logan v. Common

wealth, 308 Ky. 259, 262-263, 214 S. W . 2d 279 (1948 ); State

v. Wilson, 217 La. 470, 486, 46 So. 2d 738 (1950) affd. 341

U. S. 901; Nicholson v. State, 38 Md. 140, 155 (1873) ; Comm. v.

Sheppard, 313 Mass. 590, 604, 48 N. E. 2d 630 (1943) cert. den.

300 U. S. 213; State v. Grover, 96 Me. 363, 366, 52 A. 757

(1902) ; People v. Dudgeon, 229 Mich, 26, 30, 201 N. W . 355

(1924) ; State v. Schabert, 222 Minn. 261, 263, 24 N. W . 2d 846

(1946) ; Brooks v. State, 178 Miss. 575, 582, 173 So. 409 (1937) ;

State v. Gibilterra, 342 Mo. 577, 585, 116 S. W. 2d 88 (1938);.

State v. Sherman, 35 Mont. 512, 519, 90 Pac. 981 (1907) ; Cramer

v. State, 145 Neb. 88, 97-98, 15 N. W . 2d 323 (1944); State v.

Cleveland, 6 N. J. 316, 326, 78 A. 2d 560, 23 A. L. R. 2d 907

(1 9 5 1 ) ; State v. Vaisa, 28 N. M. 414, 417, 213 Pac. 1038 (1923);

People v. Elmore, 277 N. Y. 397, 404, 14 N. E. 2d 451, 124 A. L. R.

465 (1938 ); State v. Kerns, 50 N. D. 927, 940, 198 N. W . 698

(1924); State v. Collett, 58 N. E. 2d 417, 424 (Ohio) (1944) ; Smith

v. State, 77 Okla. Crim. 142, 146-147, 140 P. 2d 237 (1943);

State v. Jordan, 146 Ore. 504, 511, 30 P. 2d 751 (1934) ; Comm.

v. Van Horn, 188 Pa. 143, 168, 41 A. 469 (1898); State v. Wil

liams, 31 Nev. 360, 371, 102 P. 974 (1909); State v. Adams,

------ - R. I. -------, 121 Atl. 418, 419 (1923); State v. Scott, 209

S. C. 61, 64-65, 67, 38 S. E. 2d 902 (1946); State v. Nicholas,

62 S. D. 511, 515, 253 N. W . 737 (1934); Wynn v. State, 181

Tenn. 325, 329, 181 S. W . 2d 332 (1943); Cavazos v. State,

143 Tex. Cr. 564, 566, 160 S. W . 2d 260 (1942 ); State v. Crank,

105 Utah 332, 355, 364, 142 P. 2d 178, 170 A. L. R; 542 (1943) ;

Jackson v. Commonwealth, 193 Va. 664, 674, 70 S. E. 2d 322

(1 9 5 2 ) ; State v. Van Brunt, 22 Wash. 2d 103, 108, 154 P. 2d

606 (1944) ; State v. Richards, 101 W . Va. 136, 141, 132 S. E.

375 (1926 ); Pollack v. State, 215 Wise. 200, 217, 253 N. W . 560

(1934); Clay v. State, 15 W yo. 42, 59, 86 Pac. 17 (1906); Wilson

v. U. S., 162 U. S. 613, 624 (1896); Witt v. United States, 196

F. 2d 285, 286 (C. A. 9th, 1952), cert. den. 344 U. S. 827; Murphy

v. United States, 285 F. 801, 808 (C. A. 7th, 1923), cert den.

261 U. S. 617; Catoe v. U. S., 131 F. 2d 16, 19, 76 App. D. C.

292 (1942).

27

the confession.28 29 But no jurisdiction has been found which

keeps from the jury the circumstances surrounding the

exaction of a confession which it has heard. Indeed, in

Alabama the rule is that if a confession is held not to have

been coerced as a matter of law, the trial court permits the

jury to hear evidence concerning its exaction so that it

may determine its credibility.30 This is the English rule

too.31 But by tightly drawing the circle of relevancy the

28 The states are classified in 170 A. L. R. 567.

30 Dyer v. State, 241 Ala. 679, 4 So. 2d 311 (1941) ; Vernon V.

State, 239 Ala. 593, 196 So. 96 (1940). The jury was so charged in

this case (R . 175), but, of course, it had been denied petitioner’s

proffered evidence and so the instruction was meaningless.

31A recent case in the King’s Bench decided by Lord Chief

Justice Goddard, contains a particularly clear discussion of the im

portance of the right to present evidence of involuntariness to the

ju ry :

“ The recorder was wrong in the course which he took.

It was quite right for him to hear evidence in the absence of

the jury and to decide on the admissibility of the confession;

and, since he could find nothing in the evidence to cause him

to think that the confession had been improperly obtained, to

admit it. But its weight and value were matters for the

jury, and in considering such matters they were entitled to

take into account the opinion which they had formed on the

way in which it had been obtained. Mr. Hooper was per

fectly entitled to cross-examine the police again in the pres

ence of the jury as to the circumstances in which the confes

sion was obtained, and to try again to show that it had been

obtained by means of a promise or favour. If he could have

persuaded the jury that, he was entitled to say to them;

‘You ought to disregard the confession because its weight is

a matter for you.’

“ The point, if there is any doubt about it, ought to be

finally settled. * * * It has always, as far as this court is

aware, been the right of counsel for the defence to cross-

examine again the witnesses who have already given evidence

in the absence of the jury; for if he can induce the jury to

think that the confession was obtained through some threat

2 8

trial court in this case barred the proffered testimony from

the jury.

This ruling was patently erroneous insofar as it denied

petitioner the right to testify concerning the confession—

about which prosecutrix had testified— (ft. 58, 64-65) which

was made immediately following the coercion at Kilby.

And certainly reasonable men knowing all the facts,

could have concluded that the subsequent confessions were

coerced, even if arguendo, by moving petitioner to the

City Jail the State escaped the consequences of coercion

at Kilby as a matter of law.92 But the jury here was

prevented from knowing all the facts, and could not fairly

try the issue.