Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Petition for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

August 5, 1971 - October 26, 1972

29 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Petition for Rehearing En Banc, 1971. b97e5447-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1650b5c0-b12f-456d-88cd-32d901c64948/mapp-et-al-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tn-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

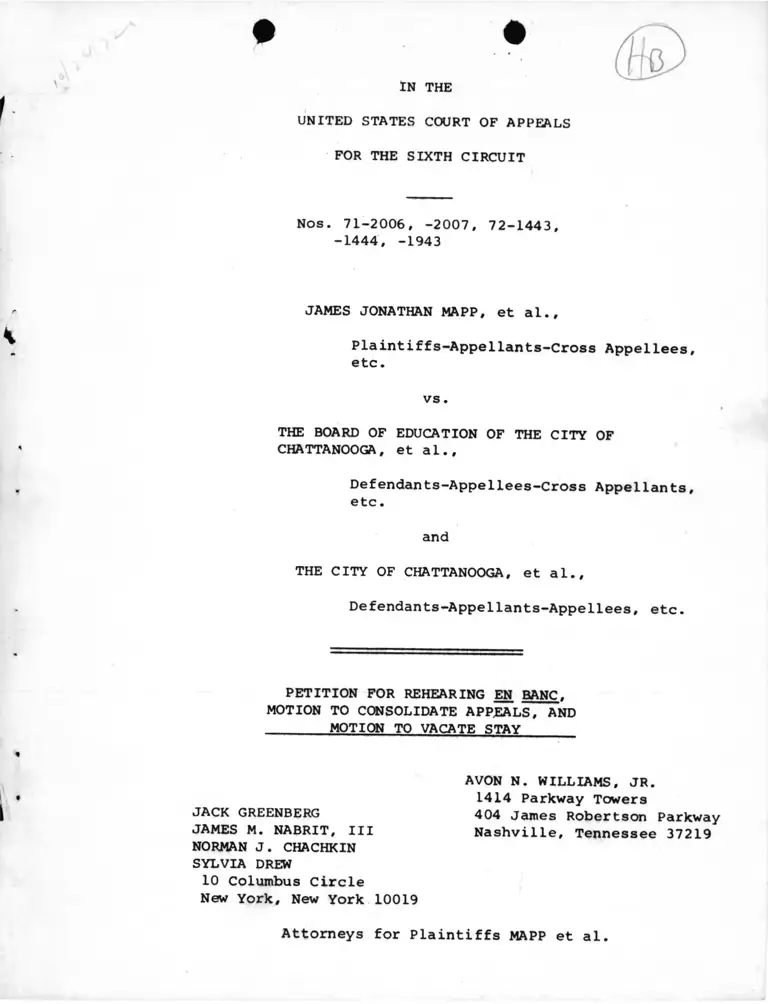

In t he

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443,

-1444, -1943

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

etc.

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants,

etc.

and

THE CITY OF CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants-Appellees, etc.

PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC.

MOTION TO CONSOLIDATE APPJEALS, AND

_______ MOTION TO VACATE STAY

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

JACK GREENBERG 404 James Robertson Parkway

JAMES M. NABRIT, III Nashville, Tennessee 37219

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs MAPP et al

f IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 71-2006. -2007, 72-1443, -1444

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants,

and

THE CITY OF CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants-Appellees

PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Plaintiffs below, JAMES JONATHAN MAPP et al., by their

undersigned counsel, respectfully pray that pursuant to F.R.A.P.

40 and 35(a), this Court grant rehearing en banc of the October

11, 1972 decision by a panel in these appeals, in an opinion

rendered by Judges Weick and O'Sullivan, from which Judge Edwards

has dissented. A determination by the full Court is urgently

• •

required because (a) the opinion for the majority fails to decide

squarely any of the issues presented by the parties with the

exception of that relating to the burden of proof — and with

respect to that issue, the majority's holding is flatly contradictory

to controlling precedent, Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educw 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia.

407 U.S. 4,52 (1972); (b) the majority opinion contradicts as well a

generation of constitutional adjudication by the Supreme Court

j

commencing with Brown v. Board of Educ. (I), 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

(c) the rejection by the majority of plaintiffs' request for in

structions to the District Court requiring further desegregation

of the Chattanooga public school system, and the underlying thesis

throughout the majority opinion that desegregation need not be

"maximized," conflict with "opinions of this court in which the

great majority of the members of this court have joined" (Edwards,

J., dissenting herein); (d) most of this Court's school desegre

gation cases come from Tennessee, and the inconsistency of approach

result among- panels of this Court leads to the application

of different constitutional rules to the various school systems

of the State, and creates confusion among the lower courts concerning

the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment in this Circuit; and

(o) the majority opinion remands this matter to the district court

-2-

for further consideration with virtually no guidance whatsoever,

in an opinion which seems to encourage abandonment of even the

minimal desegregation thus far achieved in Chattanooga, and which,

absent intervention by the full Court, is likely to result in

grave injustice to the plaintiffs and further denial of their

constitutional rights.

I. The Facts

This action to desegregate the public schools of Chattanooga,

Tennessee, was commenced on April 6, 1960, some five years after** I

the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Educ. (II), 349

U.S. 294 (1955). No desegregation had yet occurred in Chattanooga,

and progress toward disestablishment of the dual biracial system

of public education in Chattanooga has remained inordinately slow.

The Board resisted the District Court's initial order to submit

a desegregation plan [see 295 F.2d 617 (6th Cir. 1961)] and proposed

to defer complete desegregation for eight years [see 203 F. Supp. 843

(E.D. Tenn. 1962), aff'd 319 F.2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963)]. When its

dual attendance zones were finally eliminated, the school system

created new zones coextensive with areas of racial residential

segregation, maintained optional zones in areas of racial transition,

and applied various transfer rules, all with the result that

desegregation was minimized [see generally, Brief for Plaintiffs-

Appcllants in No. 71-2006, pp. 6-11].

-3-

Although it had never taken affirmative, as opposed to

"neutral," action to bring about the integration of the Chattanooga

schools [see Brief for Defendant-Appellee and Cross-Appellant in

Nos. 71-2007, -2007, pp. 8-9], the school board resisted the

District Court's determination that under Swann and other decisions

of the United States Supreme Court, it was required now to take such

affirmative action, on the specious ground that its conduct —

however ineffective to bring about desegregation in Chattanooga —

had not specifically been held insufficient in this case prior to

1971, that it was not therefore "in default" as that phrase is

used in Swann, and that it was not therefore responsible for the

continued segregation of its schools.

Following lengthy hearings, the District Court ruled from

the bench on May 19, 1971 that, measured by the standards enunciated

by the Supreme Court of the United States in Swann and companion

cases, the school board was not operating a unitary school system.

Accordingly, the District Court directed the submission of further

desegregation plans. The school board then submitted plans (plain

tiffs had previously introduced their proposal at the earlier

hearings), which were approved for the elementary and junior high

school grades in a memorandum opinion entered by the district court

on July 26, 1971. Since part of the elementary and junior high

school desegregation plan required the acquisition of additional

-4-

transportation facilities, the District Court's Order of August 5,

1971 permitted the school board to defer complete implementation

of the elementary and junior high school plan until the necessary

buses could be purchased, but as soon as practicable.* Approval

of a plan for the high schools was reserved.

In December, 1971, certain individual citizens of Chattanooga

commenced a suit in the Circuit Court of Hamilton County, Tennessee

against the City of Chattanooga, its mayor and city commissioners,

to enjoin the direct or indirect expenditure of city funds to

purchase buses in order to comply with the aforementioned August

5, 1971 Order of the District Court. Such an injunction was issued

by the Circuit Judge on January 18, 1972. Upon appropriate motions

and proceedings, the plaintiffs and defendants in the state court

action were made additional parties defendant in the federal liti

gation and all parties were enjoined from enforcing or attempting

to enforce the state court judgment. At the same time, the District

Court amended its August 5, 1971 Order to require completion of

the process of implementing plans for elementary and junior high

school desegregation which it had previously approved by not later

★

During the 1971-72 school year, the elementary and junior high

schools were partially desegregated; twelve elementary and junior

high schools were more than 90% black, nine were more than 90%

white, while only eight schools enrolled between 30% and 70% black

students. Approximately 55% of the system-wide enrollment is black.

-5-

than the commencement of the 1972-73 school year. Finally, the

District Court directed further submissions from the school board

with respect to the question of high school desegregation by

June 15, 1972. (No order approving a plan for high school deseg

regation has yet been issued by the District Court).

On July 24, 1972, the school board filed with the District

Court a motion to stay further implementation of pupil desegre

gation in the elementary and junior high schools, which would

require transportation, purportedly pursuant to Section 803 of the

Education Amendments of 1972, P.L. 92-318. The motion revealed

that on June 13, 1972, the board had cancelled a purchase order

for the necessary buses, without court approval, because it inter

preted §803 as guaranteeing it a stay. On August 11 the District

Court granted the requested stay, interpreting §803 as applying to

school desegregation and racial balance orders. The appeal in No.

72-1943 followed.

In summary, while the District Court in May, 1971 found that

the Chattanooga school system was not yet unitary, it deferred

complete implementation of a plan of desegregation for elementary

and junior high schools until the 1972-73 school year; while an

appeal and cross-appeal from its judgment were pending, the school

board unilaterally took action which made it impossible to carry

-6-

out the remainder of the plan by the 1972-73 school year, and the

District Court subsequently stayed that portion of its order

pursuant to an interpretation of a federal statute which has been

rejected by every other federal court in the nation, including the

entire United States Supreme Court on Monday, October 16, 1972,

No. A-377, Board of Educ. of Memphis v. Northcross.

On October 11, 1972, the decision on these appeals, of which

rehearing en̂ banc is herein sought, was issued by a majority of a

panel of this Court, nearly two months after a separate appeal

and motion seeking vacation of the district court's stay had been

filed. However, the majority opinion not only fails to address

itself to the issues on these appeals; it declines to disturb the

District Court judgments of which the parties sought review,

remands the matter for further ccnsideration by the District Court,

but obliquely endorses the stay by holding precedential interpre

tation of §803 irrelevant to this case. The result is that a return

to segregation has been sanctioned by the District Court and this

Court of Appeals.

II. The Issues on Appeal

The parties to the various appeals presented the following

general issues: plaint if f s contended that the district court had

erred in deferring high school desegregation rather than ordering

implementation of the plan presented by their expert witness, that *

* See the accompanying Motion to Consolidate Appeals and Motion to

Vacate Stay. -7-

the lower court erred in accepting the school board's elementary

and junior high school proposals because they excluded certain

racially identifiable schools from the desegregation process on

legally untenable grounds, and that the board's proposals improperly

placed the burden of such desegregation as would occur dispropor

tionately upon black students. The Chattanooga Board of Education

contended that it was not "in default" as that language appears in

Swann and therefore it had no obligation to affirmatively consider

race in designing a further desegregation plan, that it ought not

have the burden of proving that segregated schools in Chattanooga

do not result from past discrimination, that a race—conscious plan

of integration of the sort required by the district court would not

improve educational opportunity and would violate the constitutional

rights of students assigned involuntarily, and that the school

board had no obligation to maximize integration. The City of

Chattanooga attacked the district court's power to compel local

officials to expend funds to purchase transportation equipment in

order to effectuate student integration, both generally under the

Eleventh Amendment and also in the specific circumstances of this

case wherein the City claimed not to have been a party to the action

prior to its January, 1972 joinder.

Ill. The Decision of the Panel

The majority opinion for the panel, by Judge Weick, summarizes

-8-

the contentions of the parties (s.o. at 1-2) and tie n states:

It is obvious to us that none of the parties is

satisfied with the desegregation order of the

District Court and that the main appeal is only

a piecemeal appeal. For the reasons hereinafter

set forth, and in compliance with the request of

the plaintiffs we remand for further consideration

and direct the District Court to present a plan

which will finally determine this apparently-

indeterminable litigation, which is now more than

twelve years old. We do not grant to plaintiffs

declaratory relief which they request, as this is

beyond our jurisdiction as an Appellate Court.

Plaintiffs' request for declaratory relief should

be presented to the District Court.*

*This paragraph is exemplary of the plain legal errors committed

by the majority which should be corrected by this Court en banc.

Insofar as the majority viewed the case as a "piecemeal appeal,"

because the District Court had not approved a desegregation plan

for all grades on a "permanent" basis, but had deferred part of

the job, it did not follow its own logic and dismiss the appeal;

insofar as the majority may have taken that "piecemeal" status

to relieve the Court of the obligation to decide the issues

presented to it, such a ruling conflicts with Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Bd. of Educ., 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970) and is clearly

erroneous. See generally, United States v. Texas Educ. Agency.

431 F.2d 1313 (5th Cir. 1970); Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of

Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Bd., 396 U.S. 226, 290 (1969, 1970). Plaintiffs sought not a

general remand to the District Court without guidance but rather

specific instructions concerning the legal errors which the District

Court had made and should avoid in the future; indeed, plaintiffs

sought a declaratory judgment with respect to certain of these

matters in order that the law should be quite clear to the lower

court* (The contention that this Court cannot issue such a judgment

directly conflicts with the jurisdictional provisions of the Judicial

Code:

In case of actual controversy within its

jurisdiction, except with respect to Federal

taxes, any court of the United States, upon

the filing of an appropriate pleading, may

declare the rights and other legal relations of

any interested party seeking such declaration,

whether or not further relief is or could be

sought. . . .

28 U.S.C. §2201 (emphasis supplied).

-9-

Following a brief history of the case emphasizing the "good

faith" of the school board, i.e., its willingness to obey, without

the necessity of formal contempt proceedings, orders of the District

Court which had failed to bring about meaningful desegregation in

Chattanooga, the majority opinion proceeds to comment upon various

issues, although it does not directly decide any. The matters

upon which the majority does express itself are generally those

contentions made by the defendants. Ordinarily such discursive

comments might be classified as dicta which do not detract from a

clear holding, but here, where there is no such ruling, and where

the majority merely remands to the District Court for further

consideration, its comments assume importance since they will no

doubt be taken to heart by the district judge.

For example, the majority comments that both the plaintiffs'

plan and that approved by the District Court, which had as their

goal the establishment of schools with racial compositions between

30% and 70% black [or white], are plans embodying "fixed racial

quotas" of the sort eschewed in Swann. The majority does not,

however, reverse the judgment of the District Court on this

account despite the palpable legal error which it claims to have

found. Again, the majority shuts its eyes to the explicit language

of the Supreme Court in Swann, 402 U.S. at 26, and says that in

its judgment, "the [District] Court erred in placing on the

-10-

defendants the burden of proof in resisting plaintiffs' motion

for further relief" (s.o. at 9) by demonstrating that schools in

Chattanooga attended overwhelmingly by students of one race are

unrelated to past or present discrimination. Yet the majority

does not reverse the lower court's judgment for this "error."

The discussions of the majority abound with emotional

references to the purported benefits of "neighborhood schools,"

again despite the Supreme Court's emphasis in Swann that

[d] esegregation plans cannot be limited to the walk—in school,"

402 U.S. at 30. Thus in the section of its opinion entitled,

Maximizing Integration," the majority suggests that constitutional

requirement declared by the Supreme Court must be balanced against

the very "neighborhood school" traditions the Supreme Court

specifically held were secondary to the effectuation of constitiiional

rights.

Finally, although it is absolutely clear in Chattanooga, as

it was in Memphis and Nashville, for example, that meaningful

desegregation of urban public school systems cannot be achieved

without pupil transportation, the majority rhetorically asks

the District Court not to employ that desegregation tool on remand:

"If now every order involving schools requires busing, the question

may well be asked, 'What next?'" (s.o. at 13).

-11-

Our difficulty in cogently summarizing the majority's

opinion stems from its failure to announce clear holdings on

issues, and its ambiguous remand for further consideration. When

the opinion is read as a whole, however, we believe its hostility

to desegregation appears almost tangibly, and its conflict with

the Fourteenth Amendment law as pronounced by the Supreme Court

of the United States is virtually self-evident.

IV- Reasons Why Rehearing En Banc Should Be Granted

The reasons why this matter should be reheard en banc may

be simply put: the majority of a panel has decided an important

case involving the protection of fundamental constitutional rights

in a manner which conflicts not only with the recent trend of

decision in this Court, but also with the principles expounded

in decisions of the United States Supreme Court which are binding

upon the lower federal judiciary. The appeal is one of a class

of cases which appear frequently upon the dockets of this Court

and the district courts within its jurisdiction, and resolution

of the conflicts among panels of this Circuit in approach to

and decision of such cases will eliminate confusion of district

judges as well as make unnecessary further appeals to this Court

in other cases in order to obtain such resolution.

The description of the case in the first parts of this

Petition suffices, we believe, to identify some of the glaring

-12-

• •

inconsistencies of approach between the majority of the panel

and the Supreme Court of the United States. In similar fashion,

the dissenting opinion of Judge Edwards in this case lists many

of this Court's own recent school desegregation decisions with

which the opinion of the majority in this case is necessarily at

odds, and we shall not dwell upon these conflicts. The chief

difference between the panel majority and both the Supreme Court

and other panels of this Court seems to us to be the majority* s

failure to apprehend the Supreme Court's basic tenet that deseg

regation plans are judged by their effectiveness. e ,g., Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); see,

> Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.. 409 F.2d

682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969); Clark v. Board

of I’.duc. of Little Rock. 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970), cert.

denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971). This principle recently received

cogent and forceful application by this Court in Kelley v. Metro

politan County Bd. of Educ.. 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir. 1972) and

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis. No. 72-1630 (6th Cir.,

August 29, 1972). In both of those decisions, other panels of

this Court recognized the test of effectiveness, and also that

the burden of demonstrating effectiveness rests with the school board.

The kind of confusion into which district judges are thrown

by the issuance of contradictory opinions in school desegregation

-13-

cases from this Circuit is illustrated by the defendants' claim

(Brief for Defendant-Appellee and Cross-Appellant in Nos. 71-2006

and -2007, p. 15) that after an initial ruling based upon Kelley,

436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970) and Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of

Educ., 442 F .2d 255 (6th Cir. 1971), "[t]he District Court

appeared to shift emphasis on the basis of Goss v. Board of

Education of City of Knoxville. 444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir., June 22,

1971) . . . . ' •

To plaintiffs' knowledge, this Court has never sat en banc

to hear a school desegregation case. Not only would such a

hearing establish consistent Circuit-wide policy to the benefit

of district judges, and indirectly of this Court's workload,

but it will avoid unnecessary Supreme Court review of matters

which do not truly represent policy of the Circuit. Additionally,

such a hearing in this case will serve to further the application

of a consistent body of law to Tennessee school desegregation cases

Finally, rehearing en banc is compelled, we think, by this

Court’s heavy responsibility under our Constitution and the oath

of office to administer justice. With respect to the issue of

school desegregation, decisions of the Supreme Court of the United

States have made it clear that Courts of Appeals, as much as

district courts, have a responsibility to further the rapid and

effective dismantling of dual school systems. E .g ., Alexander v.

-14-

Holmes County Bd. of Educ., supra. Here, if the majority's

decision is not reviewed, the already long-delayed desegregation

of the Chattanooga public schools will be yet again* postponed,

perhaps indefinitely. it is incumbent upon this Court to act to

prevent any further denial of constitutional rights to the black

children of Chattanooga.

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted that

this Court should grant rehearing en banc of the October 11, 1972

panel decision in this cause, and establish a schedule for such

additional briefs as the Court desires, in order to effectuate

complete relief effective with the 1973-74 school year.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

MAPP et al.

-15-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443,

-1444, -1943

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

etc.

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants,

etc.

and

THE CITY OF CHATTANOOGA, et al..

Defendants-Appellants-Appellees, etc.

MOTION TO CONSOLIDATE APPEALS

Plaintiffs below, JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al., by their

undersigned counsel, respectfully pray that the above-captioned

appeals be consolidated for purposes of rehearing or hearing

en. banc before this Court, and in support of their motion would

show the Court as follows:

1. Nos. 71—2006 and —2007 are an appeal and cross—appeal

by the Plaintiffs and the Board of Education of the City of

Chattanooga, respectively, from the Order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee, Southern

Division, entered August 5, 1971, directing implementation of

certain desegregation measures affecting elementary and junior

high schools in Chattanooga insofar as possible for the 1971-

72 school year and in any event as soon as practically feasible.

2. Nos. 72-1443 and -1444 are appeals by the City of

Chattanooga and the School Board of the City of Chattanooga,

respectively, from the Order of the same United States District

Court entered February 4, 1972, which amended the Order of

August 5, 1971 so as to require complete implementation of the

aforementioned elementary and junior high school desegregation

by the commencement of the 1972-73 school year and which also

enjoined the School Board, the city and city Council and certain

other added parties from enforcing or seeking to enforce a

state court injunction against the expenditure of funds

necessary to implement the district court orders.

3. No. 72-1493 is an appeal by Plaintiffs from an Order

of August 11, 1972 entered by the district court which granted

a stay of the August 5, 1971 and February 4, 1972 desegregation

Orders insofar as any pupil reassigned pursuant to such Orders

would require transportation, which stay the district court

held was required by the provisions of Section 803, Education

Amendments of 1972, P.L. 92-318.

-2-

4. Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443, and -1444 were argued

together on their merits before a panel of this Court consis

ting of Circuit Judges Weick and Edwards and Senior Circuit

Judge O'Sullivan on June 6, 1972. These appeals were decided

together in an opinion written by Judge Weick and joined by

Judge O'Sullivan [Judge Edwards dissenting] on October 11, 1972.

The entire matter was "[rjemanded for further consideration"

without formal affirmance or reversal, although the majority

opinion does decide at least one issue (the "burden of proof"

question) raised in No. 71-2007.

5. No. 72-1943 was initiated in this Court almost two

months prior to the issuance of the aforementioned opinion, by

the filing of a "Motion of Plaintiffs-Appellants for Suspension

of Rules, Summary Reversal and Immediate Relief, including

Vacation of Stay Order and Hearing In Banc" on or about August

16, 1972. Although the majority opinion in the related cases

does not purport to determine the merits of this appeal, it does

hold that decisions of individual Supreme Court Justices on

stay motions presented pursuant to § 803 of the Education

Amendments of 1972 are "not relevant" in light of the Court's

remand, and based upon that statement, the City of Chattanooga

as appellee in No. 72-1943 has recently filed a "Suggestion of

Mootness and Motion to Dismiss Appeal."

6. Simultaneously with the filing of this Motion to Con

solidate Appeals, plaintiffs are filing a Petition for Rehearing

En Banc of the panel's October 11, 1972 decision in all of the

-3-

above-captioned matters except No. 72-1943, in which appeal a

suggestion of hearing en banc has been filed but not yet

acted upon. It would therefore be appropriate for the entire

Court to consider all of these appeals together.

7. All of these appeals are concerned with the selection

and effectuation of an appropriate plan for the full desegre

gation of the public schools of Chattanooga, Tennessee and

their consideration would be simplified by their consolidation

in this Court.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons. Plaintiffs respect

fully pray that the clerk be directed to consolidate all of the

above-captioned appeals for purposes of further consideration

and disposition by this Court.

Respectfully submitted

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

MAPP, et al.

-4-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443,

-1444, -1943

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al.,

Plaintiffs-AppeHants-Cross Appellees, etc.

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

De fend ants-Appe1lees-Cros s Appe1lants, etc.

and

THE CITY OF CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appe1lants-Appe1lees, etc.

MOTION TO VACATE STAY

Plaintiffs below, JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al., by their

undersigned counsel, respectfully pray that this Court en banc

issue an order vacating the stay issued by the District Court

on August 11, 1972 so that the Chattanooga School Board shall

take the necessary steps to carry out the orders of the District

Court of August 5, 1971 and February 4, 1972 at the earliest

practicable opportunity. in support of their motion, plaintiffs

would show this Court as follows:

1. On August 5, 1971, the District Court directed the

Board of Education of the city of Chattanooga to take certain

steps to implement a desegregation plan for elementary and

junior high schools as soon as the necessary transportation

f ^ ^ H t i e s could be acquired. By order of February 4, 1972,

the District Court required that such steps be completed and

desegregation fully implemented by the commencement of the

1972-73 school year.

2. However, upon motion of defendants, the District

Court on August 11, 1972 stayed those parts of its desegrega

tion order which required the acquisition of transportation

capability because the Court held that Section 803 of the

Education Amendments of 1972, P.L. 92-318, applied to its

earlier orders even though they were designed to achieve

desegregation and not racial balance.

3. On August 16, 1972, plaintiffs filed a motion for

suspension of the rules and immediate relief and including

vacation of the said District Court stay, along with a

suggestion of hearing en banc in No. 72-1943. That request

has never been acted upon by this Court.

4. However, on October 11, 1972, the panel of this

Court to which the other above-captioned appeals were assigned

issued its judgment and a majority opinion by Judge Weick,

concurred in by Judge O'Sullivan, remanding this entire matter

to the District Court "for further consideration" without

-2-

either approving or disapproving specifically the previously

ordered steps toward desegregation. The majority opinion

states that:

The decisions of individual Justices of the

Supreme Court on applications for a stay under

the provisions of § 803 of the Education Amend

ments of 1972, Pub.L. 92-318, § 803 (June 23,

1972) are not relevant here in view of our

remand of these appeals to the District Court

for further consideration.

5. The decision of the District Court is in conflict

with the interpretation given Section 803 by Mr. Justice

Powell in Drummond v. Acree, No. A-250 (September 1, 1972),

previously furnished to this Court, and the determinations

of other Justices on stay applications pursuant to that section.

See dissenting opinion of Edwards, J. in this cause, pp. 14-

17. in addition, the entire Supreme Court of the United

States denied an application for a stay pursuant to Section

803 (which had also been denied by this Court) in Board of

Education of Memphis v. Northcross. No. A-377 (October 16, 1972).

See Exhibit A hereto.

6. Prior to obtaining a stay from the District Court,

the Chattanooga School Board unilaterally cancelled an order

for the purchase of busses necessary to carry out the District

Court s desegregation decree, and unless the stay is vacated

there will be an additional delay in effectuating desegregation

should the decision of the panel be reversed by the entire

Court.

-3-

7. Simultaneously with the filing of this motion,

Plaintiffs are submitting a Petition for Rehearing En Banc

of the October 11 decision and a Motion to Consolidate these

appeals.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, Plaintiffs respect

fully pray that an order issue from this Court vacating the

stay order of August 11, 1972 issued by the District Court

and reinstating the District Court Orders of August 5, 1971

and February 4, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

MAPP, et al.

-4-

* •

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

WASHINGTON, D. C. 20543

October 16, 1972

Jock Patras, Esq.

900 Mwvhle lei* Bid*.

Nasphis, Tom. 38103

18: M . of Itoittoa of tho Moaphlt City

Mools, ot ol. ▼. lortheroM, ot el.,

g W S g E-Sk - i H.mt—

Dear Sir:

The Court: today entered the following

order m the above-entitled case:

Tho application for stay protested to

Mr. Justice 8tavert, end by hie referred to

the Court, Is denied.

l£aekcc: uXtck Greeebeco, Kef.

10 Coluebos Circle

mrc 10019

Very truly yours,

MICHAEL R0DAK, JR., Clerk

Bv

He. 1. Cel

Loots 1

325

u * i 2 r *

Xltlc il^l,Glcn Taylor> (Mrs.)

38103 ‘

’Assistant Clerk

Clerk

COCA 6

08 Ct.B.

Clndnnetl, Ohio 45202

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443, -1444

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al..

Plainti f fs-Appe11 ants-

Cross Appellees,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-

Cross Appellants,

and

THE CITY OF CHATTANOOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appel1ants-

Appellees.

RESPONSE TO MOTION TO DISMISS

PLAINTIFFS' PLEADINGS AND ALTERNATIVE

MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

Plaintiffs, by their undersigned counsel, respond to

the "Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs' Pleadings" filed herein

on or about October 30, 1972 as follows:

1. The Petition for Rehearing _En Banc was timely filed.

Rule 40(b) F.R.A.P. provides:

The petition ... shall be served and filed as

prescribed by Rule 31 (b) for the service and

filing of briefs.

This provision modifies the language of Rule 40(a) set out at

page 2 of the brief in support of motion. Rule 31 does not

define the method of filing but Rule 25(a) provides that briefs

shall be considered filed as of the date of mailing. Plain

tiffs, therefore, submit that petitions for rehearing are

likewise to be considered filed as of the date of mailing.

2. Similar objections to the timeliness of petitions for

rehearing or rehearing en banc were overruled and the petitions

considered on their merits by the Fifth Circuit in United

States v. Georgia, 5th Cir. No. 29067 (July 15, 1970) and the

Eighth Circuit in Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22,

8th Cir. No. 19746 (October 28, 1969).

3. The cases cited at pages 2-4 of the brief in support

of motion are inapposite since none deals with a petition for

rehearing, as to which the provisions of the Federal Rules of

Appellate Procedure are distinguishable, as noted above.

4. Should the Court be of the view that the petition

was not timely filed, plaintiffs respectfully pray that the

Court consider this their alternative motion pursuant to

Rules 26 (b) and 2 for an enlargement of time within which to

file petition for rehearing to and including October 26, 1972.

Such a petition is manifestly required in the interests of

justice particularly since plaintiffs did not receive a copy

-2-

of the October 11, 1972 decision and judgment of the panel

until October 16, 1972 because of delays in mailing. In

addition, the petition itself was mailed October 24, 1972, in

sufficient time according to the experience of counsel unless

delayed by the United States postal service, to be received

the following day in Cincinnati.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs respect

fully pray that the Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs' Pleadings

be denied or in the alternative that this Court enter an order

extending the time within which plaintiffs might file a

petition for rehearing to and including October 26, 1972 nunc

pro tunc.

Respectfully submitted

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

MAPP, et al.

-3-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 31st day of October, 1972,

I served a copy of plaintiffs' Response to Motion to Dismiss

Plaintiffs' Pleadings and Alternative Motion for Extension of

Time upon counsel for the defendants, Raymond B. Witt, Jr.,

Esq., 1100 American National Bank. Bldg., Chattanooga, Tennessee

37402 and Eugene N. Collins, Esq., 400 Pioneer Bank Bldg.,

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402, by depositing same in the

United States Mail, postage prepaid.

— t ie n k k 'UU *— ^ V V — ----------Norman J. Chachk^n

Attorney for Pla/intiffs MAPP

et al.

-4-

i