Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Appendix

Public Court Documents

December 4, 1967

334 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Appendix, 1967. 49ce7448-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1659d419-f871-4c9c-9b44-395f46bc3056/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-appendix. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

/

\

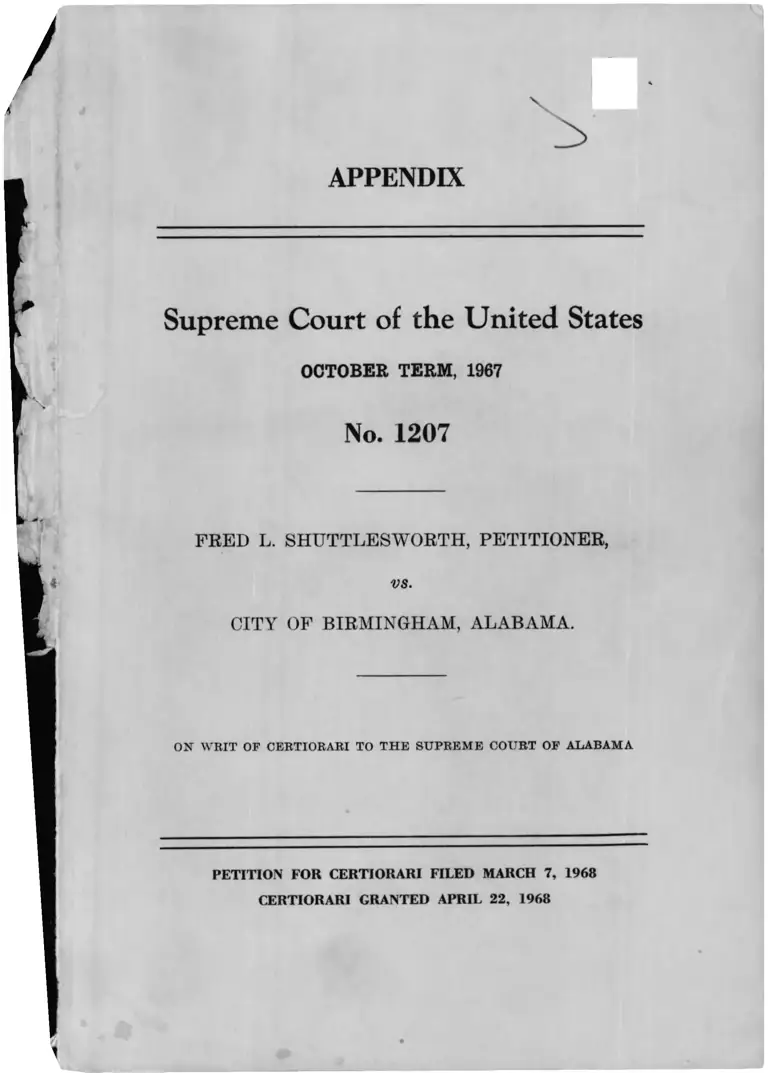

APPENDIX

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

No. 1207

FRED L. SHUTTLESWORTH, PETITIONER,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU P R E M E CO U RT OF A LA B A M A

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED MARCH 7, 1968

CERTIORARI GRANTED APRIL 22, 1968

1

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

No. 1207

FRED L. SHUTTLES WORTH, PETITIONER,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU P R E M E COU RT OF A L A B A M A

I N D E X

Original Print

Yol. I

Proceedings in the Circuit Court for the Tenth

Judicial Circuit of Alabama

Complaint........................................................... 3 1

Demurrers ......... -............................-................. 4 2

Motion to Exclude the Testimony and for

Judgment ....................................................... 8 4

Judgment E n try ............................................... 9 6

Motion for a New Trial ........................................ 12 9

Defendant’s Refused Charge .............................. 14 12

Sentence .................................................................. 15 13

Transcript of Evidence ...................................... 17 15

Witnesses

R. N. H igginbotham .................................... 19 18

Sarah W. Naugher ............................... 30 31

Edward Ratigan .......................................... 33 36

Herman Evers, Jr........................................ 41 45

Marcus A. Jones, Sr.............................. 48 52

Rosa Lee Craig ............................................ 59 66

John D. Brown ....................................... 62 68

Barbara Jean Breedlove .......................... 63 70

Rev. Charles B illups .......... -............... 65 73

Rev. F red L. Shuttleswortii .................. 68 76

Oral Charge of the Court ................................ 75 82

11 INDEX

Original Print

Vol. I

Proceedings in the Court of Appeals of

Alabama, Sixth Division

Assignment of Errors ..................................... 80 86

Majority Opinion ................... 81 88

Dissenting Opinion ..................... 121 144

Judgment ........................................................... 130 155

Original Print

Vol. II

Proceedings in the Supreme Court of Alabama

Petition for Certiorari to Court of Appeals 1 157

Order Granting W r it ....................................... 5 162

Opinion ............................................................... 6 163

Judgment ........................................................... 24 177

Application for Stay ....................................... 25 179

Order Granting Stay ....................................... 29 183

2

Demurrers

Isr t h e C ircu it C ourt of J efferson C o u n ty

A labam a , T e n t h J udicial C ircu it

No. 25988

C it y of B ir m in g h a m ,

Plaintiff,

—vs.—

F red L . S h u t t l e s w o r t h ,

Defendant.

D em urrers

Comes the defendant, in the above styled cause, and

demurs to the Complaint filed against him in this Court,

and as grounds therefor assigns the following separately

and severally:

1. That the allegations of the Complaint are so vague

and indefinite as not to apprise the defendant of what

he is called upon to defend.

2. That the Ordinance, under which said Complaint is

brought and as applied to this defendant, violates Section

25, Article 1 of the Constitution of Alabama.

3. That the said Ordinance, under which this action is

brought constitutes an abridgement of his right to apply

to those invested with power of government for redress

of grievances or other purposes, violative of rights se

cured to all persons by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the United States Constitution.

[fol. 3]

PROCEEDINGS IN THE CIRCUIT COURT FOR THE

TENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OF ALABAMA

Comes the City of Birmingham, Alabama, a municipal

corporation, and complains that Fred L. Shuttlesworth

within twelve (12) months before the beginning of this

prosecution and within the City of Birmingham or the

police jurisdiction thereof, did take part or participate

in a parade or procession on the streets of the City with-

out having secured a permit therefor from the commis

sion, contrary to and in violation of Section 1159 of the

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944.

In t h e C ir cu it C ourt for t h e

T e n t h J udicial C ircu it of A labam a

Case No. 25988

C it y of B ir m in g h a m , A Municipal Corporation,

Plaintiff,

—vs.—

F red L. S h u ttle sw o r th

Complaint

W il l ia m C. W alker

Attorney for City of Birmingham

F iled i n O pen C ourt

S ept 28^1953^

J u l ia n S w if t

C lerk C ir cu it C ourt

By V. D.

[fol. 4]

3

Demurrers

4. That the said Ordinance is : unconstitutional on its

face and constitutes deprivation of liberty without due

process of law, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.

--------------- A

5. That the said Ordinance, which is the basis of the

complaint, constitutes an abridgement of the privileges

and immunities of citizens of the United States in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

6. That to convict defendant under the said Ordinance,

the basis of this complaint, would constitute a denial of

the equal protection of the laws, in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

[fol. 5] 7. That the allegations of said complaint are

mere conclusions of the pleader.

A r t h u r D . S hores

O rzell B illin g sley , Jr.

Attorney for Defendant

F iled in O pen C ourt

S ept 28, 1963

J u l ia n S w if t

Clerk Circuit Court

By YD

4

| fol. 8]

Motion to Exclude the Testimony and for Judgment

In t h e C ircu it C ourt of J efferson C o u n t y , A labam a

No. 25988

S tate of A labam a ,

J efferson C o u n t y ,

C it y of B ir m in g h a m ,

—vs.—

Plaintiff.

F red L . S h u t t l e s w o r t h ,

Defendant.

M otion to E xclude t h e T estim o n y and for J udgm en t

Conies now Fred L. Shuttlesworth defendant in this

cause after all of the testimony and evidence for the City

of Birmingham has been given and received in this cause,

and moves this Court to exclude said testimony and evi

dence and to give judgment for defendant, and as grounds

for said motion set out and assign the following, sep

arately and severally.

1. The City of Birmingham has not made a case against

this defendant.

2. All of the testimony and evidence given in this cause

indicates that defendant during the time and on the occa

sions in question merely exercises rights and privileges

given to him as a citizen of the State of Alabama and of

the United States of America, and by the First and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States of America.

5

3. There lias been absolutely no evidence introduced by

the City of Birmingham, to support the complaint or war

rant in this cause.

4. All of the testimony and evidence offered by the

City of Birmingham dose not prove defendant guilty of

any criminal act or unlawful acts during the time in

question.

A r t h u r D . S hores

O rzell B illin g sley , J r .

Attorneys for Defendant

F iled in Open C ourt

Oct 1, 1963

J u lian S w if t , Clerk Circuit Court By VD

Motion to Exclude the Testimony and for Judgment

6

[fol. 9]

Appealed from Recorder’s Court

(Violation of Section 1159, General City Code)

Honorable Geo. Lewis Bailes, Judge Presiding

Judgment Entry

T h e S tate ,

C it y of B ir m in g h a m ,

—vs.—

F red L. S h u t t l e s w o r t h .

This the 30th day of September, 1963, came Wm. C.

Walker, who prosecutes for the City of Birmingham, and

also came the defendant in his own proper person and

by attorneys, Shores and Billingsley, and thereupon came

a jury of good and lawful men, to-wit: H. I). Spivey and

eleven others, who being duly empaneled and sworn ac

cording to Law, before whom the trial of this cause was

entered upon and continued from day to day and time

to time, said defendant being in open Court at each and

every stage and during all the proceedings in this cause;

the City of Birmingham files its written Complaint in this

cause, and the defendant files demurrer to said Com

plaint, and said demurrer being considered by the Court,

it is ordered and adjudged by the Court that said demur

rer be and the same is hereby overruled, and the defen

dant files motion to quash the jury venire, and said mo

tion being considered by the Court, it is ordered and ad

judged by the Court that said motion be and the same

is hereby overruled; and the defendant being duly ar

raigned upon the written Complaint of the City of Bir

mingham, for his plea thereto says that he is not guilty.

This the 1st day of October, 1963, the City rests and the

defendant files motion to exclude, and said motion being

7

Judgment Entry

considered by the Court, it is ordered and adjudged by

the Court that said motion be and the same is hereby

overruled; defendant makes motion to modify stipula

tion of counsel to present in evidence certain motion pic

ture views, and said motion being considered by the Court,

it is ordered and adjudged by the Court that said motion

be and the same is hereby overruled; and on this the 1st

day of October, 1963, said jurors upon their oaths do say,

“We the Jury, find the defendant guilty as charged in

the complaint, and fix his punishment at a fine in the

sum of $75.00 Dollars” . It is therefore considered by the

Court, and it is the judgment of the Court that said de

fendant is guilty as charged in the complaint, in accord

ance with the verdict of the jury in this cause, and that

[fol. 10] he pay a fine of Seventy-five Dollars ($75.00)

and costs of this cause.

Said defendant being in open Court, and having pres

ently failed to pay the fine of Seventy-five Dollars ($75.00)

and the costs of $5.00 accrued in the Recorder’s Court

of the City of Birmingham, or to confess judgment with

good and sufficient security for the same, it is therefore

considered by the Court, and it is ordered and adjudged

by the Court, and it is the sentence of the Law that the

defendant, the said Fred L. Shuttlesworth, perform hard ,

labor for the City of Birmingham for forty (40) days,

because of his failure to pay said fine and costs of $5.00

accrued in said Recorder’s Court, or to confess judgment

with good and sufficient security therefor.

It is further considered by the Court, and it is ordered

and adjudged by the Court, and it is the sentence of the

Law that the defendant, the said Fred L. Shuttlesworth,

perform additional hard labor for the City of Birming

ham for ninety (90) days, as additional punishment in

this cause. v

8

And the costs legally taxable against the defendant in

this cause amounting to Twenty-eight Dollars ($28.00),

not being presently paid or secured, and $4.00 of said

amount being State Trial Tax, $3.00, and Law Library

Tax, $1.00, leaving Twenty-four Dollars ($24.00) taxable

for sentence, it is ordered by the Court that said defen

dant perform additional hard labor for the County for

eight days, at the rate of $3.00 per day to pay said costs.

It is further ordered by the Court that after the sentence

for the City of Birmingham has expired that the City

authorities return the defendant to the County Authori

ties to execute said sentence for costs.

It is further considered by the Court that the State of

Alabama have and recover of the said defendant the costs

in this behalf expended, including the costs of feeding the

defendant while in jail, for which let execution issue,

[ fo l .l l ] This the 1st day of October, 1963, defendant

files motion for new trial and said motion being con

sidered by the Court, it is ordered and adjudged by the

Court that said motion be and the same is hereby over

ruled, to which action of the Court in overruling said mo

tion, defendant duly and legally excepts.

Notice of Appeal being given and it appearing to the

Court that, upon the trial of this cause, certain questions

of Law were reserved by the defendant for the consider

ation of the Court of Appeals of Alabama, it is ordered

by the Court that the execution of the sentence in this

cause be and the same is hereby suspended until the deci

sion of this cause by said Court of Appeals of Alabama.

It is further ordered by/tlTe Court that the Appeal Bond

in this cause be and the same is hereby fixed at Twenty-

five Hundred Dollars ($2500.00), conditioned as required

by Law, and defendant duly and legally excepts.

Judgment Entry

9

[fol. 12]

No. 25988

Motion for a New Trial

C ity of B ir m in g h a m ,

— vs.---

F red L . S h u t t le sw o r th ,

Plaintiff,

Defendant.

M otion for a N ew T rial

Now comes the defendant, in the above styled cause and

with leave of the Court first had and obtained, and moves

this Honorable Court to set aside the verdict and judg

ment rendered on to-wit: Oct. 1, 1963 and that this Honor

able Court will grant the defendant a new trial, and as

grounds for said Motion sets out and assigns the follow

ing, separately and severally:

1. That the verdict of the Jury and Judgment of the

Court, in said cause, are contrary to law.

2. That the verdict of the jury and judgment of the

court are contrary to the facts.

3. That the verdict of the jury and judgment of the

court are not sustained by the great preponderance of

the evidence in the case.

4. The Court erred in overruling the defendant’s de

murrers filed in this case.

10

5. The Court erred in finding the defendant guilty of

violating the laws or ordinances of the City of Birming

ham, Alabama, in that the laws or ordinances, under which

this defendant was charged and convicted, and as applied

to this defendant, constituted an abridgement of freedom

of speech violative of rights and liberties secured to the

defendant by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States of America.

6. That the Court erred in refusing to find that the

ordinance under which this defendant was being tried, as

applied to this defendant, constituted a denial of the equal

protection of the laws, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of

America.

[fol. 13] 7. That the Court erred in finding the defen

dant guilty of violating the laws or ordinances of the City

of Birmingham, Alabama, in that the laws or ordinances

under which this defendant was charged and convicted,

and as applied to this defendant, constituted a depriva

tion of liberty without due process of law, in violation

of the Constitution of the State of Alabama and the pro

visions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

8. The Court erred in overruling defendant’s Motion

to Exclude tire evidence in this cause.

9. The Court erred in overruling defendant’s Motion

to Quash the Jury Venire in this cause.

10. For that the Court erred in overruling defendant’s

Motion to Quash the Venire on grounds that Negroes had

Motion for a New Trial

11

been systematically excluded therefrom, because of their

race or color in violation of rights and privileges guaran

teed him by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

11. For that the verdict of the jury is based on bias,

prejudice and passion against defendant.

12. For that the Court erred in denying defendant’s

Motion to Declare void and illegal the petit jury drawn

to try defendant in this cause, in that there were no

Negroes serving on said petit jury.

13. For that the Court erred in denying defendant’s

Motion to Quash Venire returned against the defendant

on the grounds that Negroes qualified for jury service

in Jefferson County, Alabama, are arbitrarily systemati

cally and intentionally excluded from jury duty in vio

lation of rights and privileges guaranteed defendant by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution.

14. For that the Court erred in overruling defendant’s

Motion to set aside the verdict of the jury and for judg

ment in this cause.

[fob 14]

A rth u r D. S hores

O rzell B illin g sley , J r .

Attorneys for Defendant

F iled in O pen C ourt

Oct. 1, 1963

.Ju lian S w if t

Clerk C ir cu it C ourt

Motion for a New Trial

VD

12

Defendant’s Refused Charge

DEFENDANT’S REFUSED CHARGES

The following charge was requested by the defendant,

in the presence of the jury and before the jury retired,

and was refused by the Court, said charge being in writ

ing, and being endorsed separately and severally “Refused

Bailes, J.” and being in words and figures as follows,

to-wit:

Defendant’s requested Charge #1

If you believe the evidence in this case, then gentlemen

of the jury, you should find the defendant not guilty.

Refused-Bailes, J.

13

[fol. 15]

Sentence

T h e S tate of A labam a ,

J efferson C o u n t y .

A ppeal B ond— H ard L abor S en ten ce

K now A l l M en B y T hese P resents, That we F. L. Shut-

tlesworth principal, and Jas. Esdale & Willie Esdale as

sureties, are held and firmly bound unto the State of

Alabama in the sum of Twenty Five Hundred & no/100

($2500.00) Dollars, for the payment of which well and

truly to be made, we bind ourselves, our heirs, executors

and administrators, jointly and severally, firmly by these

presents; and we and each of us waive our rights of

exemption under the Constitution and laws of the State

of Alabama as against this bond.

T he C ondition of t h e A bove O bligation Is S u c h , That

whereas, the above bounden F. L. Shuttlesworth was on

the 1 day of Oct. 1963. convicted in the Circuit Court of

Jefferson County, Alabama, for the offense of Parading

Without A Permit—Gen City Code Sec No 1159 and had

assessed against him a fine of $75.00 Seventy Five &

No/100 Dollars, together with the cost of this prosecution,

and on the 1 day of Oct. 1963, on failure to pay fine was

sentenced to perform hard labor for the County f o r ..........

days, and an additional term for the cost, at the rate of

seventy-five cents per day, and as additional punishment

imposed the defendant was sentenced to perform hard

labor for the County for 90, from which sentence the

said F. L. ShnttleswortlTJias this day prayed and ob

tained an appeal to the Court of Appeals of Alabama.

14

Sentence

Now, i f t h e S a i d F. L. Shuttlesworth shall appear and

abide such judgment as may be rendered by the Court of

Appeals, and if the judgment of conviction is affirmed, or

the appeal is dismissed, the said F. L. Shuttlesworth shall

surrender himself to the Sheriff of Jefferson County, at

the County Jail, within fifteen days from the date of such

affirmation or dismissal, then this obligation to be null

and void, otherwise to remain in full force and effect.

Given under our hands and seals, this the 1 day of Oct.

Approved:

J u l ia n S w ift

Clerk of the Circuit Court of Jefferson County.

F iled in O ffice

O ct . 1, 1963

J u lian S w if t

1963.

[fol. 16]

F. L. S h u ttlesw o r th

J as. E sdale

W illie E sdale

By J as . E sdale, Atty in fact

E sdale B ail B ond Co

By J as. E sdale

(L.S.)

(L.S.)

( L S . )

(L.S.)

(L.S.)

(L.S.)

Atty. in Fact.

Clerk

15

[fob 17]

Transcript of Evidence

In t h e C ikcuit C ourt of t h e T e n t h J udicial C ircu it

In and for J efferson C o u n t y , A labam a

Case No. 25988

Cit y of B ir m in g h a m ,

—vs.—

Complainant,

F red S h u t t le sw o r th ,

Respondent.

C a p t i o n

Tiie above en titled cause came on to be heard before

the Honorable George Lewis Bailes, Judge Presiding, and

a jury, on the 30th day of September, 1963, commencing at

or about 3 :00 P.M., Jefferson County Courthouse, Birming

ham, Alabama, when the following proceedings were had

and done:

A p p e a r a n c e s :

William C. Walker, Assistant City Attorney, City Hall;

and Lewis Wilkinson, Assistant City Attorney, City Hall,

for the Complainant.

Arthur Shores and Orzell Billingsley, Jr., Masonic Tem

ple Building, Birmingham, Alabama, for the Respondent.

P r o c e e d i n g s :

The Court: Both sides ready!

Mr. Walker: We are ready.

Mr. Billingsley: Yes, sir.

16

Colloquy

The Court: And you want to present, first, the demurrer

to the complaint?

Mr. Shores: Well, first the motion to quash venire. We

submit on our demurrers.

The Court: I would hear you on the question of sub

mitting- them.

[fol. 18] Mr. Billingsley: Your Honor, we don’t neces

sarily wish to argue the motion to quash venire, we are

going to file another motion after the jury is empaneled,

which I think will take care of some of the situation.

The Court: Very well, let the motion to quash venire

be overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

The Court: And next would be the demurrer.

Mr. Billingsley: Yes, sir, the demurrer.

The Court: Let the record show the demurrer to the

City’s complaint is overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception, Your Honor.

The Court: Is this Case No. 25988?

Mr. Shores: That is right.

(Whereupon, a jury venire was sent for and entered the

Court Room at 3:40 P.M., were duly qualified by the Court,

identified, and special questions were asked by counsel on

behalf of the respective parties and the following oc

curred:)

The Court: Now, the hour being what it is, what is the

pleasure of counsel in the case?

Mr. Shores : We would like to recess until in the morning,

Your Honor.

Mr. Walker: 1 have no objections to that, Judge Bailes.

The Court: Very well, in the morning. The next thing

that the law requires me to say is please do not mention

I

Colloquy

the case to anyone of your brethren on the jury, nor to

any member of the family, nor to anybody anywhere. Do

not mention the case until you have heard all the evidence

in the case and have retired to your room for deliberation,

before you ever say anything about the case. With that

little reminder, I bid you to be at leisure until 9:00 A.M.

[fol. 19] in the morning.

(Whereupon, proceedings were in recess from 4:30 P.M.,

September 30, 1963, until 9 :00 A.M., October 1st, 1963, and

the following occurred:)

O ctober 1st, 1963 9 :00 A .M .

M orning S ession

The Court: Counsel ready?

Mr. Walker: Yes, sir.

Mr. Billingsley: Yes, sir.

The Court: Let the jury be brought into the box.

(Jury brought in at 9:10 A.M.)

The Court: Good morning, everybody. Counsel ready?

Mr. Billingsley: We are ready.

Mr. Walker: We are ready.

The Court: I believe the jury was not sworn.

Mr. Walker: I don’t think they were.

(Whereupon, the jury was sworn by the Court.)

The Court: Let the cause be stated. Is the complaint—

I believe it is already filed.

Mr. Walker: Yes, sir.

(Whereupon, Mr. Walker addressed the jury in opening-

statement on behalf of the Complainant; following which

Mr. Shores addressed the jury in the opening statement

\

18

on behalf of the Respondent; following which the follow

ing occurred:)

Mr. Walker: Your Honor, are we ready!

The Court: Yes, sir.

Mr. Shores: Judge, we would like the witnesses put

under the rule.

(Whereupon, the rule was invoked on the witnesses; fol

lowing which the following occurred:)

E videxce o x B e h a lf op C o m p l a ix a x t

Mr. Walker: Call Officer Higginbotham.

K. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Hired

[ fo l . 20] R. N. H ig g ix b o t h a m , ca lled as a w itn ess, b e in g

first d u ly sw orn , w as exam in ed and testified as f o l l o w s :

Dir ext Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. State your name, please.

A. R. N. Higginbotham.

Q. And occupation!

A. Police Officer for the City of Birmingham.

Q. And, Officer Higginbotham, how long have you been

so employed?

A. Eighteen years next month.

Q. Now, what detail are you assigned to A v ith the Police

Department?

A. Traffic Division.

Q. Were you working for the Traffic Division on April

12th of this year?

A. I was.

Q. Is that Good Friday?

A. Yes, sir.

19

Q. Now, Officer Higginbotham, did you have an occasion

to see or view a parade on that day?

Mr. Shores: Your Honor, we object to the term

“parade” . That is a legal conclusion. I think he

could go into or frame his questions in such a way

as to determine what happened or what he saw or

did during the day.

Mr. Walker: Judge Bailes, parade has a well de

fined meaning and, if anything, would be an ultimate

fact.

The Court: Let him answer the question.

Mr. Billingsley: He can ask the witness what hap

pened. He doesn’t have to use words of conclusion

as to say that they were parading. It would be a

conclusion on Mr. Walker’s part.

The Court: The Court has ruled.

[fol. 21] Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

Q. Officer, tell what you saw on that occasion, at that

time.

A. I was sitting at 17th Street—at 18th Street and 5th

Avenue, when the large crowd.of.people turned east, on

5th Avenue from across the park at 17th Street, and also

from 17th Street into 5th Avenue.

Q. Is that the first time you saw this group?

A. It was.

Q. And where were you at that time?

A. I was at the corner of 18th Street and 5th Avenue.

Q. And where was the group, again, please?

A. They was just coming on to 17th Street and 5th Ave

nue on the 5th Avenue side.

Q. And which direction were they traveling?

A. East.

B. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Direct

20

Q. On which street?

A. 5th Avenue.

Q. Now, do you have any opinion as to how many people

were in the group?

A. There was several hundred people.

Q. Several hundred.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were they in any kind of formation at that time?

_ A. There was a formation on the sidewalk on the north

side of 5th Avenue. There was also a lot of people to the

rear on the south side of the street that didn’t seem to be

in any formation, just sort of walking along.

Q. You didn’t see this parade—

Mr. Billingsley: We object.

Mr. Walker: We withdraw that.

Q. You didn’t see this group of people—where they came

from, is that correct?

A. No, I didn’t.

[fol. 22] Q. Now, what did you do when you saw them

at that time, if anything?

A. 1 observed the crowd approaching. 1 heard singing-

going on—

Mr. Billingsley: We are going to object to this

line of questioning, until he has tied this Defendant

up.

The Court: (five him time.

A. I approached the middle of the block towards 17th

Street. I crossed over to the block to the sidewalk with

my motor. 1 got off my motor, and when they got close

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Direct

21

enough to me I hollered in a loud voice, “ Does anyone in

this group have a permit” ?

Mr. Billingsley: We object to that line of ques

tioning.

The Court: Overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

Q. Did anyone in this group have a permit?

Mr. Billingsley: We object to that question.

The Court: Overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take an exception.

A. I received no answer from the parade at this time.

Q. Now, Officer Higginbotham, did you, at any time, see

the Defendant in that group of people?

A. I did.

Q. Where did you see the Defendant?

A. The best I can remember, he wTas several—in the line

across the sidewalk—he was several people back from the

front. "

Q. Was he in the group?

A. Yes, he was in the group.

Q. And what did you see the Defendant do, if anything?

A. I didn’t see him do anything that anyone else wasn’t

doing.

Mr. Billingsley: WTe object and ask that that an

swer be stricken from the record.

The Court: Overruled.

[fol. 23] Mr. Billingsley: It’s irrelevant, incom

petent, and immaterial, and has nothing to do with

the vital issues in this case.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Direct

22

The Court: Overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: Exception.

Q. Officer Higginbotham, who, if anyone, was leading

this group of people?

Mr. Shores: Your Honor, we object to the fram

ing of this question. We are not concerned with

anyone but the Defendant. I think that the proper

question is whether or not the Defendant was lead

ing, would be the proper question.

The Court: Well, please let him answer.

A. I couldn’t say who was leading, because they were

all the way across the sidewalk and I don’t know who was

leading.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

Mr. Walker: That is all.

Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

Q. Officer Higginbotham, where did you first see this

group of people that you speak of?

A. As it came on to 5th Avenue from 17th Street.

Q. Did you observe them coming through the park there ?

A. No, sir.

Q. You just observed them as they came?

A. I was at the corner of 18tli Street.

Q. And at the time how were they marching or walking?

A. They were four to six across the ̂ sidewalk all the

way across the sidewalk on the north side ot 5th Avenue

leading east.

Q. And had the street been blocked?

A . No, imhmTiTf at this time.-V

v

23

- Mr v V

V Q. Was it ever blocked off at 5th Avenue between 17th

and 18tli Street, ever blocked!

A. No, now I don’t know.-----.

Q. Were you there all the time from the time that you

observed them until the time they were arrested?

A. Yes, I was.

[fol. 24] Q. Did you—you don’t know whether it was

blocked off?

A. I couldn’t see, there was some people in the way.

Q. Did you address the group yourself?

A. I did.

Q. And was there any bands along with them?

A. No.

Q. Was there-any particular organized sort, of form a -

lion?

A. The group on the sidewalk was.

Q. The group on the sidewalk was?

A. Right.

Q. What about the other group, I believe you said there

was another group to the rear and to the side.

A. There was milling, and there was a large crowd ap

proaching from the back of them. They were all over.

They were gathering all the time on the street on the

opposite side of the sidewalk.

Q. And who were the group gathering on the opposite

side and alongside?

A. I didn’t know any of them.

Q. Were they all the one race identity or were they

white and black?

A. They were all black.

Q. Did you stop any of the other groups?

A. Everyone stopped at this time that I brought it to a

halt, they did.

w R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

>

24

Q. How did you determine who was marching of the

so-called marchers or paraders from the other group?

A. .The group to the north side of the sidewalk headed

east were signing. They were in—I wouldn’t say exactly

rows, but they were paired off in fours and sixes and they

were the only group that there was singing, or any kind

of formation.

Q. The group that was in the formation was paired off

in fours and sixes, is that correct?

A. Right.

[fol. 25] Q. And I believe when you said you first

observed this Defendant, he was back in one of the

other groups?

A. He was in this group on the north side of the

sidewalk headed east on 5tli Avenue, but he wasn’t

exactly in the front row. The best 1 can remember he

was in the, maybe, third or fourth row back.

Q. In the group on the opposite side of the street?

A. This was the group that was on the north side

of 5th Avenue.

Q. And that was not the group singing?

A. Yes, it was.

Q. Was he part of that group and was he walking?

Did you see whether or not he attempted to speak to

somebody in this group?

A. That I don’t know. I was so busy I don’t even

know whether he was singing or not.

Q. You don’t know whether he was in the organized

group, do you?

\ A. He was in the organized group. ]

\ 'QTWas there somebody"marching- along beside, men

in two’s or three’s or four’s?

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

25

A. There was people around him at this time they

was ahead of the other group.

Q. Where was he when you first saw him!

A. The first time that I noticed him was when I stopped

the group.

Q. And where were you when you stopped the group?

A.^Approximatelv in the center of the block between

17th mild 18th on 5th. Q

And at the time you stopped the group between

17th and 18th—

A. Approximately in the center of it.

Q. Where was this Defendant?

[fob 26] A. The best I can remember, he was either

two or three rows back from the front of the rows that

were leading this, the front ones in the group.

Q. Was he on the outside, or within the group or just

what was his position with respect to it?

A. I would say he was approximately in the center.

Q. And at the time you stopped him, were there other

groups on either side of the so-called marching group?

A. To the reai-, in the center of the street, and coming

up on the opposite side of the street.

The other group von sponk^nf, was it out in the

center of the stre e t ? __\

A?~Yes! *

Q. And they was people you speak of as marching

there on the sidewalk?

A. Right.

Q. Did they have a band?

A. No band.

Q. Were there any vehicles in this marching group?

A. No.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

26

Q. And all they were doing was marching and singing?

A. That is right.

Q. Did you personally arrest this Defendant?

A. 1 did not.

Q. Was he arrested at the time the others were ar

rested?

A. The whole group was under arrest./

CJT W haTTiappen ed to the group after they were placed

under arrest?

A. At this time, several other motor scouts and three-

wheelers and cars came up and blocked the street behind

me. There were several that came up at this time to

my assistance and at this time there was a lot of people

had turned and started back toward 17th Street.

Q. Now, at that time, these people that were stopped

and the other officers came up and blocked off the street,

[fol. 27] that meant that no one could move out of the

area blocked in, is that correct?

A. At this time I presume.

Q. Not what you presume, what you know and what

you saw and did.

A. To the rear of me was blocked, because when I

turned around to get on the motor there was several

police cars across in back of me.

Q. And then the crowd or group of marchers Avere

blocked in, were they not?

A. To the back of me at this time, they A v e r e .

Q. To the back of you at this time. Was this Defendant

to the back of you or to the front of you?

A. At this time he was in front of me.

Q. In front of you?

A. Eight.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

27

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Cross

Q. And where was lie at that time when the rest of

them were placed in patrol cars or buses or something?

A. At this time there was a lot of confusion going on.

A.

Mr. Billingsley: We object to that answer and

ask that it be stricken from the record.

The Court: Overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: Exception.

that. He is not

answering the question.

There was a lot of rocki throwing.

Mi-. Billingsley: We object^to

Q. My question was whether or not these people were,

whether they were escorted off to the city jail in the

bus or in the regular city paddy wagon, and what hap

pened to them at that time?

A. The best I can remember, the patrol wagons came

up and we started putting them in the patrol wagons.

Q. Was this Defendant placed in the patrol wagon?

A. At this time, I don’t know.

Q. Were you there?

[fol. 28] A. Yes, I was there.

Q. Had he left your view at that time?

A. I left the scene at this time.

Q. Where did you go?

A. 1 went to the opposite side of the street to assist

some other officers.

Q. But you do know he was in the group that was

blocked and held there until the patrol wagon was brought?

A. He was in the group that arrived there. Now, what

happened to him after that, I don’t know.

28

Q. Did you ascertain where the group was going?

A. No, I didn’t.

Mr. Walker: We object to that as immaterial,

where the group was going.

Mr. Shores: That is all, Your Honor.

Re Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. Now, Officer Higginbotham, what time of the day

was this?

A. The best 1 can remember, it was approximately 2 :15

or 2:30.

The Court: P.M.?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And at the time of this arrest, would you describe

to the gentlemen of the jury the circumstances or the

conditions that existed then?

Mr. Billingsley: Your Honor, we object to that.

Mr. Walker: Your Honor, they opened the door

to that. We have a right to show what the cir

cumstances were.

The Court: Please let the witness answer.

Mr. Billingsley: If Y7our Honor please, I don’t

understand the question when he talks about con

ditions and circumstances—

The Court: The Court has ruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

[fol. 29] A. On the morning prior to this—

Mr. Billingsley: We object.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff—Redirect

29

Q. Officer Higginbotham, I mean by the question at the

immediate time of arrest, at 2 :30 or thereabouts, what

were the conditions prevailing at the scene of the arrest,

just what was going on?

Mr. Billingsley: Your Honor, we object on the

further grounds that this witness is not qualified

to tell what was the conditions. I don’t understand

what condition he is talking about; the conditions

in Bessemer or Houston, or about the weather.

I don’t see that Officer Higginbotham can answer

that question and we object to that.

The Court: Overruled.

Q. Officer Higginbotham, just tell what you saw at the

time of the arrest.

A. At the time of the arrest there was a lot of loud

hollering going on, there was a lot of rocks being thrown, j

who threw them I don't knouy I don’t have any idea

who threw the rocks, but I know there was a lot of rock

throwing. There was a lot of dodging going on.

Mr. Billingsley: If Your Honor please, we would

like to object and ask for a mistrial in the case,

as his answer was for the purpose of attempting

to confuse the men of the jury in this case. He

says rock throwing and that type of thing; it needs

to be stated about the witness: How does he know

rocks were being thrown. Was he hit and what

happened to them?

The Court: He will be subject to cross-examina

tion.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

B. N. Higginbotham,—for Plaintiff—Redirect

30

A. And at the time right after we pnt, them under

arrest—who the officers were, I don’t know—some officer

hollers, “We got an officer in trouble” . I looked and saw—

Mr. Shores: We certainly object to that. That

has nothing to do with the proceedings.

The Court: This, in the intention of the ques

tion, was at the time and place of the occasion, or

[fol. 30] occurrence, or incident, or episode.

Mr. Walker: Go ahead.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception. Your Honor.

A. I ran directly across the street through the crowd

of people, and at this time we had pushed back the crowd

of people to help an officer that was in the crowd at this

time. When I got back across the street, which was

approximately five or ten minutes later, to the crowd,

the other officers had all arrived and the crowd was

being pushed back and I didn’t know who was arrested

or who was taken to jail.

Mr. Walker: That is all.

R. N. Higginbotham—for Plaintiff^Recross

Re-Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

\ )

Q. Officer Higginbotham, at the time you described what

else was going on, did you arrest this Defendant and

place any other Defendants under arrest for parading

without a permit!

A. I didn’t, no.

Q. Then this Defendant, as far as you could ascertain,

and the parties you arrested, were not engaged in any

thing but marching and parading without a permit?

A. That is rigT

31

Sarah W. Nauglier—for Plaintiff—Direct

Q. And that is wliat you arrested them for?

A. That is right.

Q. You didn’t see him throw any rocks?

Mr. Shores: That is all.

Mr. Walker: No further questions.

(Witness excused.)

The Court: Who do you have next?

Mr. Walker: Sarah Naugher.

Sarah W. Naugher, called as a witness, being first

duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

| fol. 31] Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. State your name, please.

A. Sarah W. Naugher.

Q. And occupation?

A. Clerk in the City Clerk’s office.

Q And how long have you been so employed?

A. Seventeen years.

Q. And, Airs. Naugher, what is this book that you hold

in your hands?

A. Permit book.

Q. Does that book have any relation to permits for

parades?

A. Yes, it does.

Q. What is the relation between that book and parade

permits?

A. It contains the carbon copies of the parade permits.

Q. And is part of your duty to keep that book?

A. Yes.

32

Q. Is tliat an official book of the City!

A. Yes, it is.

Q. Now, I will ask you if there was any parade permit

for any Friday, issued for parades to be held on April

12th?

A. No.

Mr. Billingsley: If Your Honor please, we would

like to object to the question on the grounds that

the testimony to be given by Mrs. Naugher is

irrelevant and incompetent, and immaterial and it

has not been established by the City of Birmingham

that there was a parade on the date that you were

talking about, and I don’t see where it has, this

whole thing has any relevancy in this case.

The Court: Overruled.

Mr. Billingsley: We take exception.

Q. Was there any permit issued for any parade on

April 12th?

A. No.

Q. Was there a permit issued for any procession on

that day?

[fol. 32] A. No, sir.

Q. Does that book contain all of the permits that has

been issued for parading during the past year?

A. Yes.

Mr. Walker: That is all.

Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

Q, Mrs^Jaugher, does that book show the applications

refused for j5enhiTsWcTparade?

A. No.

Sarah W. Naugher—for Plaintiff—Cross

33

Q. Only those issued!

A. Yes.

Q. Do you have a list of permits issued between Sep

tember—what period does that book cover!

A. It covers from 1951 to 1963.

Q. And do you have the list of permits issued between

January 1st, and June 1st!

A. Yes.

Q. Would you please list them for me!

A. The Mutual Aid Society of Groveland Baptist Church

on March 3, 1963, Mount Pilgrim District Congress on

April 11th, and the Central Park Baseball Association

on April 15th.

Q. Now, Mrs. Naugher, does the permit indicate the

route over which the parade is to take!

Sarah W. Naugher—for Plaintiff—Cross

A. Yes.

Q. And does it indicate the number of vehicles that

are or that there will be vehicles!

A Nr,

Mr. Walker: We object to this, unless it is to be

shown that the Defendant has the permit.

Mr. Billingsley: The crucial question is : What

is a parade. That is the question we have got to

determine, whether or not these persons were en

gaged in a parade or a procession, and the only

[fol. 33] way we can find out is by questioning the

witnesses to determine whether or not it is a parade.

The Court: Just go along and ask the witness

whatever you care to.

34

Sarah W. Naugher—for Plaintiff—Cross

Q. Does the permit show whether or not it was given

to parade on the sidewalk or out in the street?

A. No.

Q. Mrs. Naugher, I believe you said you have been clerk

for seventeen years.

A. Yes.

Q. You have seen a number of these parades, haven’t

you?

A. Yes.

Q. Have you noticed a parade down the streets or on

the sidewalk?

A. In the streets.

Q. All in the street?

A. Yes.

Q. And did you notice whether or not these parades

would have bands or vehicles in the procession?

A. Yes.

Q. They would?

A. Yes.

Q. And does one get a permit to picket, or just to

parade ?

A. No.

Q. Does one get a permit to._jiisl--waIk down the street?

A. No.

Q. Do you know whether or not at time when a group

of Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts were going to load up on

the bus, whether or not they would have to get a permit

to get to the bus?

The Court: That would be a legal question and

she wouldn’t be competent.

Mr. Billingsley: The vital question is whether

or not—what she has in the book there.

I

Sarah W. Nauglier—fur Plaintiff—Cross

A. We have not issued any.

[fol. 34] Q. I believe the City Auditorium—

The Court: We will leave the arguments until

we come to the arguments after all the evidence

is in.

Q. Have you seen students attending the symphony,

walking from the bus to the auditorium?

A. Yes.

Q. Does your book show whether or not they got a

permit?

Mr. Walker: We object.

The Court: Sustained.

Mr. Billingsley: Exception.

Q. Do you know whether or not a permit was issued

in the early part of September when a number of auto

mobiles paraded up and down the street?

Mr. Walker: We object to anything that hap

pened after the case.

The Court: Sustained.

Mr. Billingsley: Exception.

Mr. Walker: Judge Bailes, Mrs. Naugher is due

in the council meeting. Would it be all right for

her to leave?

Mi-. Shores: We have no objection.

The Court: She may. Who do you have next ?

(Witness excused.)

Mr. Walker: Officer Ratigan.

36

E dward Ratigan, called as a witness, being first duly

sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. State your name, please.

A. Officer Edward Ratigan.

Q. And your occupation?

A. I am a Police Officer foi1 the City of Birmingham.

Q. How long have you been so employed?

A. Eighteen years.

[fol. 35] Q. Were you so employed on April 12th?

A. I was.

Q. What was your duty on that date?

A. I was stationed in front of the church in the 1400

Block of 6th Avenue North to inform the radio on the

activities going on at the church.

Q. What time did you get to the church?

A. I just don’t remember, I don’t recall at all.

Q. Were you there approximately at 2:00, or a little

after?

A. I was.

Q. Now, what, if anything, did you observe at the

church at that time? Just tell the jury what, if anything,

you saw and heard.

Mr. Shores: Your Honor, we object to what he

saw and observed at the church. This parade is

supposed to be on the street or the sidewalk.

Mr. Walker: Your Honor, we don’t want the evi

dence—it will show the parade.

Mr. Billingsley: We object to the use of the

word parade.

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Direct

37

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Direct

Mr. Shores: We except.

Q. Tell the jury, the gentlemen of the jury, and the

Court what you saw on that occasion at the church, and

thereafter.

A. Approximately around 2 :30 I observed Martin Luther

King and A. B. Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth and

a white man I don’t know, leaving the church at the

1400 Block. They came out of the church and marched

in two’s traveling east on 6th Avenue North in the 1400

Block. They proceeded east down to, down 17th Street.

They turned, they turned south on 17th Street to 5th

Avenue and then turned east again on 5th Avenue and

were stopped in the 1700 Block of 5th Avenue North.

During this time they were marching two abreast and

they were singing.

Q. And were they in formation1?

A. They were in a formation.

[fol. 36] Q. And did you see the Defendant in that group?

A. I observed the defendant from the 1400 Block of

6th Avenue North to the corner of 6th Avenue and 17th

Street. When I made the turn I lost the Defendant

momentarily crossing in the 1700 Block and 6th Avenue.

I picked the Defendant up again within the group in the

1700 Block of 5th Avenue at the corner. He was in the

group in the 1700 Block of 5tli Avenue, when T went up

to make the arrest.

Q. You didn’t see him at the time the arrests were

made ?

A. I did not see him at the time the arrests were made.

Q. Let me see, where is the church located?

A. The church is located on the North side of 6th

Avenue within the 1400 block.

38

Q. On the north side of 6th Avenue within the 1400

Block?

A. Yes.

Q. Officer Ratigan, would you come down and draw a

diagram of the route—let’s pull this out here. Draw the

route this procession or group of people took.

A. (Drawing on blackboard)

Q. Now, Officer Ratigan, where did you first observe

the Defendant and the others that you named, King and

Abernathy, and Shuttlesworth? Where were they when

you first saw them?

A. The first time I saw them on this occasion was

coming out of the church on the 1400 Block of 6th Avenue

North.

Q. And which direction did they proceed?

A. They came out of the church, marched down the

sidewalk, marched along—I was originally here (indi

cating), cut accross and I followed them on this side of

the street (indicating). I followed them down all the

way down and they turned here (indicating).

Q. Which direction did they turn?

A. They turned south. It was approximately within

this point here (indicating) I lost the Defendant. I came

[fol. 37] across him here, and I picked him up, approxi

mately, in here again.

Q. I see. What street did they turn south on? 17th

Street is one block south of 6th Avenue North. What

street would that be or what avenue?

A. That is 5tli Avenue North.

Q. Did you ever see the Defendant on 17th Street?

A. Oh, yes. I picked the Defendant somewhere along

in the point here (indicating), and lost him again over

here because of this group marching along in here, and

Edivard Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Direct

39

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Direct

they turned and went east in this group here, and I lost

him here, (indicating), somewhere in here, almost to the

corner.

Q. Describe the formation you observed this group of

people to be in when they left the church, or as they walked

along 6th Avenue North.

A. They were marching two abreast and they were

,appijrxj_nmte]y forty unclies apart.

Q. Who was leading, or who was in front of the group,

if you know?

A. There was Martin Luther King was one of the first

ones, I don’t recall the other one. And directly behind

one of the first was this white man, who was the second

one on the right hand side. If my memory serves me

right, A. D. King was one of the second ones. ̂Fred

Shuttlesworth, when I first observed him, was _up near

the front, jle was not in~ any particular formation of

two’s, v ile was alongside of them and as they proceeded

downWthe avenue within the point here, (indicating),

approximately in here (indicating), he appeared to be

drawing back and giving encouragement.

Mr. Shores: We object to drawing back and

giving encouragement.

The Court: Yes, I think what you heard him say,

what happened, what you saw him do, would he

permissible.

A. He was talking to the crowd, but 1 did not hear

what the Defendant said.

[fol. 38] Q. How many blocks, all told, that you observed

the Defendant with the group?

A. Taking into consideration the point that I lost him,

I would say approximately three and a half blocks. That

40

half a block in here (indicating), and that would be one

and two (indicating) and 1 lost him in here and picked

him up again in here (indicating). That would be about

three blocks, but I lost him entirely in here (indicating).

Q. What was the total distance you observed the group

that included the Defendant?

A. I observed the group all along until they came into

The 1700 Block, and they were stoppecTTh the 1700 Block

of 5th Avenue.

Q. Now, just have a seat, Officer Ratigan.

A. (Witness resumes witness stand.)

Q. Officer, would you describe how the Defendant Fred

Shuttlesworth was dressed on this occasion?

A. The Defendant was wearing a black shirt with blue-

jean trousers.

Q. Would you describe how Martin Luther King was

dressed on this occasion?

Mr. Shores: We object to how he was dressed.

He is not on trial. It is irrelevant and incompetent.

Mr. Walker: This is to show that they were

acting in unison.

The Court: Let him answer.

A. He was wearing a black shirt and bluejeans as

trousers.

Q. And how was Abernathy dressed?

A. The same way.

Q. Did you observe other people on that occasion in

similar dress?

A. I don’t recall. I don’t really recall.

Q. Let me ask you this, were these leaders of the

group or the formation?

[fol. 39] A. They were.

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Direct

41

Q- And I will ask you if—what is the profession of

the Defendant, if you know?

A. I just know what 1 read in the paper, he is sup

posed to be a Reverend.

Q. And what is the profession, if you know, of Martin

Luther King?

A. lie is supposed to be a preacher.

Q. And Abernathy?

A. 1 am not sure about Abernathy.

Mr. Walker: That is all.

Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

Q. Officer Ratigan, I believe you said you observed

this Defendant, along with others, from the time they

left the church, to the time they were stopped by an

officer, and were arrested, is that correct?

A. Right.

Q. And you described the formation as two abreast

about forty inches apart, is that correct?

A. That is right.

Q. And that formation persisted from the time they

were apprehended or stopped?

A. It did.

Q. And during this time were there other people on

the side or behind, walking along the side of these people

who were in formation?

A. There were.

Q. And I believe you also stated that this Defendant

at no time was in line with a partner, marching two

abreast, but lie was alongside the line of marchers; is

that correct?

A. That is right.

Edward Ratigan— for Plaintiff—Cross

42

Q. And that was when he moved from your sight, is

that correct?

A. It was twice.

[fol. 40] Q. Now, at any time did this formation group

themselves into four’s and six’s?

A. No.

Q. At no time, from the time they began and from the

time they were marching alongside in two’s, approxi

mately forty inches apart?

A. That is right.

Q. Did you ever get close enough to this Defendant to

hear what he said, as he was walking alongside the

marchers?

A. No.

Q. You don’t know whether he was telling people keep

quiet and be orderly or what?

A. I do not.

Q. You did see him speak, from time to time, as he

walked along beside the line of marchers?

A. I did.

Q. And his position was no different from that of other

persons that walked alongside of the marchers, is that

correct? There were others avIio walked alongside the

way he walked?

A. Not the way he walked, no.

Q jH e was not in line or in a definite place as the

others you saw? He went from place to place, is that

right? Is that rigid, in the line he went from place to

jolace ?

''tVT'That is right, but the other people that were talking

were away from the curb, were nearer to the houses or

to the avenue, whereas the Defendant was to the curb

side of the street.

Edward Ratigan— for Plaintiff—Cross

43

Q. I see, but lie was not in the lines of two’s?

A. He was not in the line of two’s.

Q. And at this time they didn’t have any brass band

leading them?

A. No.

Q. And they were on the sidewalk, were they not?

A. They were.

[fol. 41] Q. Will you describe just what they were doing,

as they marched along the sidewalk.

A. All I recall is that they were marching two abreast.

_ I don’t even recall if they\vere singing.

Q. And they werg orderlv/as they were marching along?

A. Yes. f .. /

Mr. Shores: That is all.

Re-Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. Officer Ratigan, let me ask you one question. In

your opinion, how many people were in the formation?

A. When I radioed to the Police Headquarters ̂ I had

pounted 52 people that had left the church in pairs of two?

Q. And is that all?

A. That is all.

Q. Did you say 52 persons or 52 couples?

_A. 52TTOi-sonsr_This was in two’s and I counted about 23.

Q. WncTthis group that has been referred to, were they

merely spectators?

A. You mean the ones that were marching?

Q. Were there any spectators?

A. There were spectators, oh, yes.

] Q. Were those spectators a part of this formation, at

this time, when you observed them?

A7~No part of them.

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Redirect

44

Q. What was their relation as compared to the relation

of this Defendant to the group that was marching? What

was their difference?

A. There were spectators lined up along 6th Avenue

up to along the point of the houses, and as this group

would march—and the Defendant was to the curb side

of the group—then as the group would pass them, the

spectators would follow from the rear.

Q. Which sid(Twere the spectators on of the formation?

[fol. 42] Were they on the side toward the buildings or

toward the street?

A. They were toward the buildings.

Q. And which side was the Defendant on?

A. Toward the Street side.

Q. Was he with anybody besides himself?

A. Pie was just going down the line with the rest of

them after he left the church, lie was one of the three

then, and as they walked along he appeared to be talking'

to them.

Edward Ratigan—for Plaintiff—Recross

Mr. Walker: That is all.

Re-Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

Q. I believe you said you did follow the line of marchers

until they were arrested?

A. That is right.

Q. Did you participate in the arrests?

A. I participated in the arrests.

3Vns tliis Defendant arrested there, at that time?

A. He Avas_jnat—

, Q. TJ» wiic unt. arrested along with the others that

-were?

A. He was not.

45

Mr. Shores: That is all.

(Witness excused.)

The Court: Who do you have next?

Mr. Walker: Officer Evers.

Berman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

H erman E vers, Jr., called as a witness, being first duly

sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. State your name, please.

A. Herman Evers.

Q. And what is your occupation?

[fol. 43] A. City of Birmingham Police Department.

Q. How long have you been so employed?

A. Around ten years.

Q. Now, on April 12tli of this year, Officer Evers, what

was your detail?

A. I was in the—I was detailed to the downtown area

to work and watch for demonstrations that was to take

place that afternoon.

Q. Let me ask you this: Where were you—first, is

April 12th Good Friday?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Would you tell the jury and the Court where-yo^

were at approximately 2:15 and 2:30 on^Jffood Friday,,

of this year? ' / --------- -—

A. I was assigned to watch a church in the 1400 Block

of 6tli Avenue in the City of Birmingham.

Q. And would you—let me ask you this: On that occa

sion did you see this Defendant?

A. Shuttlesworth?

Q. Yes.

A. Yes, sir.

46

Q. Do you know the Defendant in this case?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And how long have you known him?

A. I have known him for about five or six years.

Q. How long did you know him when you saw him,

and did you know him when you saw him on that occasion?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. How long have you known him by sight?

A. About five or six years.

Q. Now, where was the Defendant when you first saw

him on Good Friday about 2:00 or after?

A. He and one other came up in a car. They got out

of the car and walked into the church about 2 :05, or

somewhere around in there.

[fol. 44] Q. When did you next see the Defendant?

A. When he came out of the church leading the demon

stration, approximately 2 :30.

Q. How was the Defendant dressed on that occasion?

A. When I first saw him, when he got out of the car

he was dressed in a suit. When he came back out he was

dressed in bluejeans, pants and jacket, I believe.

Q. In other words, he was dressed differently when he

came out of the church?

A. He was dressed differently, yes, sir.

Q. Did you observe a group of people coming out of the

church at the same time the Defendant came out?

A. They followed him out, yes, sir.

Q. Who was leading the group of people?

A. Well, there was King and Abernathy and Shuttles-

worth?

Q. Which King?

A. A. D. King, I believe.

Herman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

47

Q. It was A. D. King that you saw? Now, tell the Court

and the gentlemen of the jury how these people were

dressed?

A. Best I can remember, they also were dressed in this

bluejean attire.

Q. Now, describe the formation, if any, that the group

was in.

A. It was a simulated formation. They came out and

started walking east on Gth Avenue on the sidewalk in

groups of two’s and pairs of two’s, in a group strung out.

Q. Now, did you see the Defendant on this occasion?

A. I did.

Q. And was the Defendant with the formation?

A. lie was in the front, yes.

Q. When was he in the front?

A. From the time he walked out of the church, until

the last time I saw him. The last time I saw him was in

the 600 Block of 17th Street. I believe it was there by

the park.

[fol. 45] Q. Did you see him all the time?

A. On spot occasions as I was riding along with them.

Q. Now, how many, in your opinion, was in this forma

tion; how many people?

A. We counted as they came out and it was approxi

mately 52, when they came out of the church, at that

time.

Q. Was there many spectators in the area, at that time?

A. Yes.

n Did the spectators joinjthe formation?

Berman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff-—Direct

the north side of the avenue and the spectators were

Q. Where did they joint it?

A. As they crossed it they were on—the church is on

. At a distance.

48

standing on the south side and thereabouts,__As they

crossed 15th Street that is where the spectators started

coming in and joining them.

Q. Did they follow them, or did they actually join the

group or formation?

A. They were following them.

,_Q. Iiow many was—of the spectators, were in the group

following the procession?

A. In number?

Q. Do you have any opinion as to that?.

A . To me it looked like over-ar thousand.

Q. And they were—what were they doing?

A. They were following behind them singing, just loud

comments and talking and all that, i just generally a dis

orderly type crowdi ' T

Q. Officer Evers, let me ask one other question. How

long was—what was the distance that this formation

traveled, that you observed them? What distance did

you observe them traveling?

A. From the church up to 17th Street. They made a

right turn at 17th Street and then came to 5th Avenue,

and that is where I arrested them, in the 1700 Block of

5th Avenue, about the middle of the block.

[fol. 46] Q. Let me ask you this: Did this Defendant

make the turn? Did you see him after the formation

turned south on 17th Street?

A. The last time I saAV him was when the formation

turned south on 17tli Street. As I passed them going up

to 5th Avenue, after he was there at the Kelly Ingram

park.

Q. Did he turn south or do you know?

A. Yes, sir, he was there at Kelly Ingram Park.

Herman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

49

Q. Was Kelly Ingram Park on this diagram? Yon can

come down.

A. (Witness goes to blackboard.)

Kelly Ingram Park would be in this area (indicating).

Q. Where was the Defendant, approximately, the last

time you saw him?

A. Approximately, in the middle of the block.

Mr. Walker: That is all.

Cross Examination by Mr. Shores:

Q. Officer Evers, I believe you said you observed the

Defendant when he went into the church?

A. I did.

Q. He went in dressed in one attire and came out in

another?

A. That is right.

Q. Did you see anybody else go in one way and come

out dressed another?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you also saw him coming out leading this group

of fifty something persons?

A. He and King and Abernathy.

Q. They were in two’s, is that correct?

A. Groups of two.

Q. Do you recall who his partner was, if he had a

partner ?

A. He was in front talking to King and Abernathy.

Q. He was on both sides, first one side and then the

other?

[fol. 471 A. Yes, sir. King was on one side and Aber

nathy was on the other.

Herman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff—Cross

50 1

Q. And at all times lie was at the front’?

A. No.

Q. Will you describe his conduct at other times during

the procession? \

A. Ilis conduct was in a frantic conduct, such as bound

ing from the front to the rear and waving his arm~£d come

on, telling them to come on. ^

Q. Did you hear him tell them to come on?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Was he telling the marchers to come on?

A. Both. (

Q. And did you hear him saying anything else about

keeping quiet and orderly?

A. No.

Q. All you heard him sav was to wave his arms and

tell them to come on?

A. That is correct.

Q. How close were you at that time?

A. I was riding on the north side of the street. There

were cars back there, and they were on the sidewalk.

That is how close they got.

Q. They were on the sidewalk, and you were out in

the street riding your motor bike?

A. Motorcycle, yes.

Q. And what were these marchers doing as they left

the church until the time they rvere stopped between

17th and 18th Street on 5th Avenue?

A. Clapping their hands, and singing, and shouting <

and things like that.

Q. They were not just walking along?

A. Not just walking along the street, no.

Herman Evers, Jr.—for Plaintiff—Cross ,

51

Q. 1 see. And was Ratigan one of the Officers that

[fol. 48] assisted in the arrest, Officer Ratigan?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And did you see him during this time?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And what was he doing during this time?

A. He was stationed in front of the church at the

beginning.

Q. He was stationed in front of the church.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And when he was stationed in front of the church,

did he move along as they marched up the street?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And if he stated that all they did was just walk along,

he was wrong in stating that they didn’t do anything else?

A. That is his statement, not mine.

Q. He wouldn’t be telling the truth?

Mr. Wilkinson: We object, that would be im

proper.

The Court: That would be argumentative.

Q. Did you stop them as they reached a point between

17th Street and 6tli Avenue?

A. 1 did.

Q. What did you do when you stopped them, and what

did you say, and what did you do?

A. I pulled my motorcycle along the sidewalk, and King

and Abernathy dropped down on their knees. And some

body asked them if they had a permit, and nobody an

swered, and we put them in the wagon.

Q. Was the Defendant there at that time?

A. No.

Herman Evers, J r—for Plaintiff—Cross

52

Q. He was not there at that time?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you know when he left this group?

A. Like I say, the last time I saw him was in the 600

Block and 17th Street, and then he went on with the

[fol. 49] group and we cut them off and let them up to

5th Avenue, and then we put them in.

Q. Did you ever see him when he wasn’t on the side

walk ?

A. No, other than crossing the street.

Mr. Shores: That is all.

Mr. Walker: No further questions.

The Court: That is all, you may step down.

Who do you have next?

(Witness excused.)

Mr. Walker: Marcus A. Jones, Sr.

Marcus A. Jones, Sr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

M arcus A. Jones, Sr., called as a witness, being first

duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. State your name, please.

A. Marcus A. Jones.

Q. And occupation?

A. Detective for the City of Birmingham.

Q. How long have you been employed by the City of

Birmingham?

A. I have been with the City about 20 years, about

10 years as a detective.

53

Q. What was your detail on April 12th, Good Friday

of this year?

A. I was assigned to make pictures for the City of

Birmingham.

Q. Now, were you assigned—where were you on Good

Friday about 2:15 or 2:30?

A. I was in front of the church on 6th Avenue, between

14th and 15th Street.

Q. Now, would you tell the gentlemen of the jury what

you observed on that occasion, at that time?

A. Of course, I had been down there sometime before.

There was a meeting going on in the church, and approxi

mately at that time they began to come out the front,

[fol. 50] They turned to their left, and behind them the

marchers, and they marched to 17th Street, and there

they turned across the street beside the park, turned

to their right and went across the street on 5th Avenue,

turned to their left and went on up and directly to in

front of the Auto Rental business where they were stopped.

Q. And did you have an occasion to—did you see this

Defendant at the time you observed people coming out

of the church?

A. I did.

Q. Did they—of the people you observed, did they form

any type of formation?

A. They pmiifl out of tin* church in a formation.

Q. Describe that formation, please.

A. It was about three or four wide, and, of course,

jjhJi'Qiit—the front men turned to the left when they

came out, and the others in the church turned out and

followed the others, went on up the sidewalk.

TJi'Whnt wua youi "Ttetail at that Time?" S

A. T was making moving pictures at that time.

Marcus A. Jones, Sr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

54

Q. Did you make moving pictures of this Defendant,

and the group as they came out of the church"?

A. 1 did, as they turned up the street.

Q. And did you observe this group as they proceeded

east along 6th Avenue North?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you—were they in formation?

A. Yes, sir, they were in formation.

Q. Did you take moving pictures of that?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you take moving pictures continually from the

time they left the church?

A. No, sir, I didn’t take them continually. That would

be impossible.

Q. But you took moving pictures periodically?

[fol. 51] A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, have you observed those moving pictures that

you took on that occasion?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did they fairly represent to the—do they truly

represent the facts that you have testified to here?

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Walker: Your Honor, we would like to

show the movies to clarify the testimony that Mr.

Jones has given, and if possible, 1 believe that

it will be necessary to locate and to point on the

film, rather than show some things that might be

prejudicial to this Defendant, in that he might

not have been in Birmingham when other parts

of the film were taken, but we would like to show,

if we could, the part of the film that Mr. Jones

took on that occasion of that group of people

Marcus A. Jones, Sr.—for Plaintiff—Direct

55

coming out of tlie church where the gentlemen of

the jury can better understand the testimony that

Mr. Jones has given.

The Court: Any objections?

Mr. Shores: Your Honor, we would like to object

on the grounds he stated his movie wasn’t con

tinuous. From aught that appears, he might have

just taken shots at certain points which would

indicate some inconsistency with respect to the

whole line of march and not the time he was out