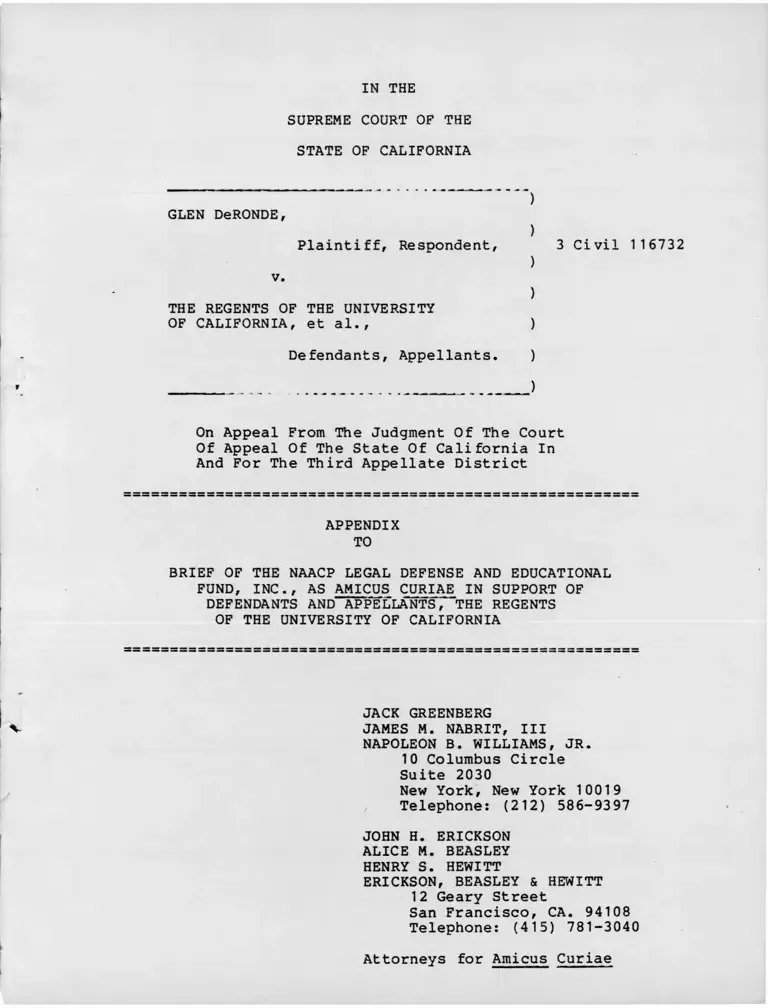

DeRonde v. University of California Regents Appendix to Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. DeRonde v. University of California Regents Appendix to Brief Amicus Curiae, 1981. fdfc4bae-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1665f7cf-d544-44a3-abd3-bafb2a914a27/deronde-v-university-of-california-regents-appendix-to-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

GLEN DeRONDE,

Plaintiff, Respondent,

v.

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA, et al..

Defendants, Appellants.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

3 Civil 116732

On Appeal From The Judgment Of The Court

Of Appeal Of The State Of California In

And For The Third Appellate District

APPENDIX

TO

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

DEFENDANTS AND APPELLANTS, THE REGENTS

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

JACK GREENBERG

V JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Telephone: (212) 586-9397

JOHN H. ERICKSON ALICE M. BEASLEY

HENRY S. HEWITT ERICKSON, BEASLEY & HEWITT

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, CA. 94108

Telephone: (415) 781-3040

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

APPENDIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

HISTORY OF DE JURE SEGREGATION IN CALIFORNIA PUBLIC EDUCATION

1. Elementary and Secondary Public School

Segregation...................................... la

2. California's Postsecondary Effort to Overcome

the Effects of Racial Segregation at Lower

Levels of Public Education ...................... 14a

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C.

Cir. 1 973) ................................. 2a,9a

Anderson v. Matthews, 174 Ca. 537, 163

P. 902 ( 1 91 7) .............................. 6a

,Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 94 (N.D. Cal.

1969) ...................................... 2a

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

( 1 954) ..................................... 4a,7a

Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215

(D. .D.C. 1 976) ............................... 2a

Carlin v. San Jose Unified School District,

___ Ca. App. Supp. 3d __, ___ Cal.

Rptr. ___ (Super. Ct. bounty of San

Diego, No. 303800, filed March 9,

1977) ...................................... 3a

Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal. 3d

280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551

P. 2d 28 ( 1 976) ............................. 3a

Diana v. State Board of Education, N.D.

Cal. Civ. Act. No. C-70-37, Rep.,

stipulation dated June 18, 1 973 ............ 3a

Gaston County v. United States, 395

U.S. 285 ( 1 969) ............................ 9a

Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215

(1971) ..................................... 2a,4a,

5a, 7a, 8a

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59

Cal.2d 876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382

P. 2d 878 ( 1 963) (en banc) .................. 3a

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified SchoolDistrict, 339 F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal.

1971), app. for stay denied, Guey Heung

Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215 (1917)

vacated and remanded, 500 F.2d 349

(9th Cir. 1 974) ............................ 2a

Page

- ii -

Page

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir.1 974) ...................................... 2a

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

( 1 973) ..................................... 6a,7a

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 ( 1 974) ............. 2a

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 Supp. 769 (S.D. Cal.

1944) ...................................... 8a

Mendez v. Westminster School District, 64 F. Supp.

544 (C.D. Cal. 1946), affirmed, 161 F.2d744 (9th Cir. 1 947) (en banc) .............. 7a

NAACP v. San Bernardino City Unified School

District, 17 Cal. 3d 311, 130 Cal.

Rptr. 744, 551 P.2d 98 ( 1 976) .............. 3a

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 1 12 ( 1 970) ......... 10a

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 ( 1 948) ........ 8a

P. v. Riles, 343 F. Supp. 1306 (N.D. Cal.

1972), affirmed, 502 F.2d 963 (9th

Cir. 1 9T4TT.T:............................. 2a

Pena v. Superior Court, 50 Cal. App. 3d 694,

123 Cal. Rptr. 500 (Ct. App. 1 975) ......... 3a

/

People v. San Diego Unified School District,

19 Cal. App. 3d 252, 96 Cal. Rptr.

658 (Ct. App. 1971), cert, denied, 405

U.S. 1 01 6 ( 1 972) ........................... 2a,3a

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P.2d

17 ( 1 948) .................................. 8a

Piper v. Big Pine School Dist., 193 Cal.

664, 226 P. 926 ( 1 924) ..................... 6a

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1 896) ......... 5a

Romeo v. Weakley, 226 F.2d 399 (9th Cir. 1955) ... 8a

San Francisco Unified School District v.Johnson, 3 Cal.3d 937, 92 Cal. Rptr.

309, 479 P.2d 669 (1971) (en banc)

cert, denied, 401 U.S. 1012 (1971) ......... 3a

- iii -

Page

Santa Barbara School District v. Superior Court,

13 Cal. 3d 315, 118 Cal. Rptr. 637, 530

P. 2d 605 ( 1 975) (en banc) .................. 4a

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of

Trustees, 386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974),

on remand from 488 F.2d 577 (9th Cir.

1 973 ) .......".................. ............. 2a

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education,

311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1 970) .......... 2a,6a

Takahaski v. Fish and Game Commission, 334

U.S. 410 ( 1 948) ............................ 8a

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P. 129 (1885) .... 6a

Ward v. Flood, 49 Cal. 36 ( 1 874) ................ 5a

Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal. 588, 23 P. 54

( 1 890) ..................................... 5a

Yick Wo. v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 ( 1 886) ........ 8a

Statutes:

State Statutes

General School Law of California § 1662

at 14 ( 1 880) ............................... 5a

1860 Cal. Stats., c. 329, § 8 ............... 5a

1863 Cal. Stats., c. 159, §68 ............... 5a

1885 Cal. Stats., c. 117, § 1 662 ........... 5a

1983 Cal. Stats., c. 193, §1 662 ............. 6a

1921 Cal. Stats., c. 685, § 1 ............... 6a

1935 Cal. Stats., c. 488, §§ 1, 2 .......... 7a

1947 Cal. Stats., c. 737, § 1 ............... 7a

1959 Cal. Stats., Res. c. 1 6 0 .............. 10a

Assembly Concurrent Resolution Number

151, 1974 Cal. Stats., Res. c. 209 (1974) . 10a,16a

U.S. Statutes

20 U.S.C. § 1600 et seq. ( 1 972) ................. 1a

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ( 1 964) ........................ 1a

- i v -

Other Authorities

American Public Health Association, Minority

Health Chartbook (1974) ...............

California Coordination Council For Higher

Education, H. Kitano & D. Miller, An

Assessment of Educational Opportunity

Programs in California Higher Education (1970). 13a,17a,

California Coordinating Council For Higher

Education, K. Martyn, Increasing Opportuni

ties In Higher Education For Disadvantaged

Students (1966) ...........................

22 California Department of Justice, Opinions

of The Attorney General, Opinion 6735a (January

23, 1930) 931-932 (1930) .....................

California Legislature, Assembly, A Master Plan

For Higher Education in California, 1960-

1975 (1960) ..............................

California Legislature, Assembly Permanent Sub-

corn. On Postsecondary Education, Unequal Access

to College (1975) ...........................

California Legislature, Joint Com. on Higher Ed

ucation, K. Martyn, Increasing Opportunities

For Disadvantaged Students, Preliminary Out

line (1967) ....................... '.......

California Legislature, Joint Com. on Higher Ed

ucation, The Challenges Of Achievement: A

Report on Public and Private Higher Education In California (1969).......................... 11a, 13a

California Legislature, Joint Com.On the Master

Plan For Higher Education, Nairobi Research

Inst., Blacks and Public Higher Education In

California (1973) ............................

California Legislature, Joint Com. on the Master

Plan For Higher Education, R. Lopez & D. Eons,

Chicanos and Public Higher Education in

California (19 72) ..... ........*............ -

California Legislature Joint Com. on the Master

Plan For Higher Education, R. Yoskioka, Asian-

Americans and Public Higher Education in

California (1973) ...........................

Page (s)

20a

18a,19a

14a,17a

7a

10a

17a,19a

13a,17a

14a,17a

18a

18a

15a,17a

v

(Page(s)

California Postsecondary Education Commission,

Equal Education Opportunity in California

Postsecondary Education: Part 1 (1976) .........

California Postsecondary Education Commission,

Planning For Postsecondary Education In

California: A Five Year Update, 1977-1982

(1977) ........................................

California State Department of Education, Racial

and Ethnic Survey of California Public

Schools, Fall 1966 (1967), Fall 1968 (1969)

and Fall 1970 (1971) ...........................

Center for National Policy Review, Justice Delayed,

HEW and Northern School Desegregation (1974) ....

Center For National Policy Review, Trends In Black

School Segregation, 1970-1974, Vol. 1 (1977) ....

Center For National Policy Review, Trends In

Hispanic Segregation, 1970-1974, Vol. II (1977)..

Darity, Crucial Health and Social Problems In The

Black Community, Journal of Black Health

Perspectives 1 (June/July 1974) ................

Davis, A Decade Of Policy Developments in Provid

ing Health Care For Low Income Families In

Haveman, R. Ed. A Decade of Federal Anti-Poverty

Policy: Achievements, Failures And Lessons

(1976) .........................................

Governor's Commission On The Los Angeles Riots,

Violence In The City (1965) ....................

Iba, Niswander & Woodville, Relation of a Prenatal

Care To Birth Weights, Major Malformations, and

Newborn Deaths of American Indians, 88 Health

Services Reports 697 (1973) ....................

I. Hendrick, The Education of Non-Whites in Cal

ifornia, 1849-1970 (1977) ......................

D. Ressner Et A., Contrasts In Health Status, Volume I

Instant Death: An Analysis By Maternal Risk and

Health Care (1973) .............................

"Maternal and~CniTcr~Hea;itn—Service, U . S .-Department

of Health, Education and Welfare, Promoting The

Health of Mothers and Children, Fiscal Year

1972 ...........................................

17a,19a

10a,11a

la, 8a

3a

la

la

21a

23a

8a

22a

5a,6a,8a

22a

23a

vi

Page (s)

Mills, Each One Teaches One, J. Black Health

Perspectives (Aug.-Sept. 1974

Montague, Prenational Influences (1962) .........

National Center For Health Statistics, Department

Of Health, Education and Welfare, Monthly _

Vital Statistics Report, Summary Report Final

Mortality Statistics (1973) ..................

National Foundation, Annual Report (1974) .......

Robertson, et al., Toward Changing the Medical

Care System: Report Of An Experiment in

Haggarty, The Boundaries of Health Care, Re

printed from Alpha Omega Honor Society, Pharos

of Alsph Omega Alpha, Vo. 35..................

Rodgers, The Challenge of Primary Care, Daedalus

82 (Winter 1977) .............................

B. Tunley, The American Health Scandal (1966) ....

U.S. Bureau Of The Census, Current Population Re-

Ports, Series P-23, No. 46, The Social and

Economic Status Of The Black Population In

The United States, 1972 (1973) ...............

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics

Of The United States, Colonial Times to 1970,

Part I (1976) ................................

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970, Census of Popu

lation, Series PC(2)-2A, State of Birth (1973).

U.S. Bureau Of The Census, Statistical Abstract

Of The United States, 1976 ...................

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Mexican-American

Education Study, Reports I-VI (1971-1974) ....

U.S. Comm. On Civil Rights, Fulfilling The Letter

And Spirit Of The Law (1976) .................

U.S. Comm. On Civil Rights, 3 The Federal Civil

Rights Enforcement Effort— 1974, To Ensure

Equal Educational Opportunity (1975) .........

21a

22a

21a

22a

23a

23a

21a

4a

4a

4a

la,20a

9a

3a

la

vii

Page(s)

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare,

Office For Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools In Selected

Districts, Enrollment and Staff by Racial/

Ethnic Groups,Fall 1968 (1970), Fall 1970

(1972) and Fall 1972 (1974) ................. la, 4a

U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of

Health, Education And Welare, Selected Vital

And Health Statistics In Poverty And Non-

Poverty Areas of 19 Large Cities, United

States, 1969-71 ............................. 22a

M. Weinberg, A Chance To Learn (19 77) .......... 5a, 7a

Weiner & Milton, Demographic Correlates of Low

Birth Weight 91 Am.J.Epidemio, 260 (Mar. 1970) 22a

C. Wollenberg, All Deliberate Speed, Segregation

and Exclusion in California Schools, 1885-1975 (1976) ................................. 5a, 6a, 7a

viii

APPENDIX

DE JURE SEGREGATION IN CALIFORNIA PUBLIC EDUCATION

1. Elementary and Secondary Public School Seg

regation

In 1972, three-quarters of California's

black elementary and secondary public school

pupils attended schools which were 50-100% black,

Chicaco, Asian or Indian; over 40% attended public

25/schools which were 95-100% minority,— and

numerous judicially noticeable decisions demon

strate that official policies have caused, at the

very least, a substantial measure of this condi

tion. The following school districts have been

found to have segregated minority school children

25/ BUREAU OF THE CENSUS' STATISTICAL ABSTRACT

OF THE UNITED STATES, 1976, p. 133 (1975).

Statistical evidence on the extent of seg

regation in California elementary and secondary

education is available in U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH, EDUCATION AND WELFARE, OFFICE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS, DIRECTORY OF PUBLIC ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY

SCHOOLS IN SELECTED DISTRICTS, ENROLLMENT AND

STAFF BY RACIAL/ETHNIC GROUPS, for FALL 1968

(1970), FALL 1970 (1972), and FALL 1972 (1974).

See also biannual CALIFORNIA STATE DEPARTMENT

OF EDUCATION, RACIAL AND ETHNIC SURVEY OF CALIFOR

NIA PUBLIC SCHOOLS, for FALL 1966 (1967), FALL

1968 (1969) and FALL 1970 (1971); CENTER FOR

NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW, TRENDS IN BLACK SCHOOL

SEGREGATION, 1970-1974, Vol. I (1977) and TRENDS

IN HISPANIC SEGREGATION, 1970-1974, Vol. II

( 1 977) .

federal Constitution and/or in violation of

2 6/federal statutory civil rights guarantees:—— San

„ . 27/ . , 28/ 29/rranctsco,— Los Angeles,— Pasadena,— San

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the

26/ Pursuant to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, and Title VII of the

Emergency School Aid Act of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1600

at. seq. , the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare is given authority to terminate federal

assistance in cases of, respectively, school seg

regation generally and teacher assignment. HEW's

enforcement role is discussed in, inter alia, 3

U.S. COMM. ON CIVIL RIGHTS, THE FEDERAL CIVIL

RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT EFFORT— 1974, To Ensure Equal

Educational Opportunity 49-138 (1975). Recent

litigation concerning HEW1s failure to fulfill its

enforcement obligations includes Adams v, Richard

son, 480 F. 2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 7 3); Brown v.

Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976); Kel

sey v, Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1974).

27/ Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School

District. 339 F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal. 1971), apo.

for stay denied, Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404

U.S. 1215 (1971), vacated and remanded, 500

F • 2 d 349 (9th Cir. 1 974); P. v. Riles. 343 F.

Supp. 1306 (N.D. Cal. 1972), affirmed, 502 F .2d

963 (9th Cir. 1974) (14th Amendment violation);

Lau v. Nichols. 414 U.S. 563 (1974) (Title VI

violation found).

28/ See, Kelsey v. Weinberger, supra, 498 F.2d at

704 n.19 (HEW determination of violation of.

Emergency School Aid Act noted).

29_/ Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education,

311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) (14th Amendment

violation).

Diegoj30/Oxnard ^ ' Pittsburg R i c h m o n d ^ D e l -

an0' Fresno^— Sweetwater,— Watsonville (Pa-

jaro Valley),— 7, Desert S a n d s B a k e r s field ,— /

30/ People v. San Diego Unified School District,

19 Cal. App. 3d 252, 96 Cal. Rptr. 653 (Ct. App.

1971) (14th Amendment violation).

31/ Soria v, Oxnard School District Board of

Trustees, 386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974), on

remand from, 488 F .2d 577 (9th Cir. 1973).

32/ Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 94 (N.D. Cal.

1969) (14th Amendment violation).

33/ See Kelsey v. Weinberger, supra, 498 F.2d

at 704 n.19 (HEW determination of violation of

Emergency School Aid Act noted).

34/ See , Brown v. Weinberqer, surra, 417 F. Supp

at 1224 ( violation of Title VI noticed by HEW) .

35/ See , Brown v. Weinberqer, supra, 417 F. Supp

HEW) .at 1223 ( violation of Title VI noticed by

36/ See , Brown v. Weinberqer, supra, 417 F. Supp

at 1224 (violation of Title VI noticed by HEW) .

37/ Id.

38/ Id.

39. See, CENTER FOR NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW,

JUSTICE DELAYED, HEW AND NORTHERN SCHOOL DESEGRE

GATION 108 (1974) (violation of Title VI noticed

by HEW).

3a

40/ 41/Berkeley,— and Redwood City (Sequoia).— In addi-

42/tion, school systems in Los Angelas,— San Fran-

43/ 44/ 45/ 46/cisco,— San Diego,— San Jose,— Pasdena,—

40/ Id.; see also, U.S. COMM. ON CIVIL RIGHTS,

FULFILLING THE LETTER AND SPIRIT OF THE LAW 50-54

(1976) (discussion of Berkeley's voluntary deseg

regation effort).

41/ See, CENTER FOR NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW,

JUSTICE DELAYED, HEW AND NORTHERN SCHOOL DESEGRE

GATION 108 (1974) (violation of Title VI noticed

by HEW) .

Also, the State Department of Education

agreed to remedy disproportionate representation

of Mexican-American children in classes for

educable mental retarded classes by a consent

decree in Diana v. State Board of Education, N.D.

Cal. Civ. Act. No. C-70-37 REP, stipulation dated

June 18, 1973.

42/ Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal. 3d

280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1976).

43/ See, San Francisco Unified School District v.

Johnson, 3 Cal. 3d 937, 943, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309,

311, 479 P.2d 669, 671 (1971) (en banc), cert.

denied, 401 U.S. 1012 (1971).

44/ People ex rel. Lynch v. San Diego Unified

School District, 19 Cal. App. 3d 252, 96 Cal.

Rptr. 658 (Ct. App. 1971), cert, denied, 405 U.S.

1016 (1972).

45/ Carlin v. San Jose Unified School District,

_ Cal. App. Supp. 3d ___, ___ Cal. Rptr.

Super. Ct., County of San Diego, No. 303800,

filed March 9, 1977).

46/ Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59

4a

Delano,— ^San 3ernardi.no,— '̂ and Santa Barbara— '/

have been found in violation of State school seg

regation and racial imbalance prohibitions. While

necessarily an estimate, it appears that fully 59%

of black and 43% of all minority public school

pupils in 1970 attended schools in districts that

have been found in violation of federal or State

laws prohibiting school segregation.— ^It also

should be noted that a substantial proportion of

46/ cont'd.

Cal.2d 876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 ?.2d 878

(1963) (en banc).

47/ Pena v. Superior Court, 50 Cal. App. 3d 694,

123 Cal. Rptr. 500 (Ct. App. 1975).

48/ NAACP v. San Bernardino City Unified School

District, 17 Cal. 3d 311, 130 Cal. Rptr. 744, 551

P.2d 48 (1976).

49/ See, Santa Barbara School District v. Supe

rior Court, 13 Cal. 3d 315, 319, 118 Cal. Rptr.

637, 642, 530 P.2d 605, 609-610 (1975) (en banc).

50/ Statistics derived from enrollment statistics

by school district and projected universe statis

tics for all California districts in O.S. DEPART

MENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND WELFARE, OFFICE

OF CIVIL RIGHTS, DIRECTORY OF PUBLIC ELEMENTARY

AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN SELECTED DISTRICTS,

ENROLLMENT AND STAFF BY RACIAL/ETHNIC GROUPS, FALL

1970 (1972).

5a

California's black population received some part

Moreover, the recent school desegregation

decisions indicate that California has not fully

dismantled its historic separate school system,

which has been characterized as a "classic case of

3oard of Education, 347 U.S. 483, relief ordered,

349 U.S. 294," Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S.

1215, 1215-1216 (1971) (Mr. Justice Douglas, Cir-

52/cult Justice).— Soon after the first public

5_1_/ Fully 42% of California's black population

was born in the South, see U.S. Bureau of the

Census, 1970 Census of Population, Series,

PC ( 2) - 2A, State of Birth 55, 61 (1973); see also

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population

Reports, Series P-23, No. 46; The Social And

Economic Status of the Black Population in the

United States, 1972 at 12 (1973). Extraordinary

black migration to California, principally from

the South, during and after the Second World War,

resulted in the black population multiplying

by 11.3 times from 1940 to 1970, U.S. BUREAU OF THE

SENSUS, HISTORICAL STATISTICS OF THE UNITED

STATES, COLONIAL TIMES TO 1970, PART 1, 25 (1976).

In the same period, the white population increased

by only 2.7 times).

52/ In Guey Heung Lee, Mr. Justice Douglas denied

a request by Americans of Chinese ancestry to stay

a school desegregation plan for San Francisco, ob

serving that, "[s]chools once segregated by State

of its schooling under

tions in the southern Status.—

condi-

[the] de jure segregation involved in Brown v,

6a

"colored school" was opened in in San Francisco

for black children, California's education law was

formally amended in I860— 7to permit separate

schools for the education of "Negroes, Mongolians• 5 A /and Indians,"— The constitutionality of the pro

vision subsequently was upheld, Ward v. Flood. 48

Cal' 365g)8?4) ’~ ^ but che statute was repealed

in 1880 after the closing of separate black

schools in California's largest cities for reason

5 2/ cone ' d .

action must be desegregated by State action,

at least until' the force of the earlier segrega

tion policy has been dissipated," id. at 1216.

The history of school segregation in Califor

nia is reviewed in C. WOLLENBERG, ALL DELIBERATE

SPEED, SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION IN CALIFORNIA

SCHOOLS, 1855-1975 (1976) and I. HENDRICK, THE

EDUCATION OF NON-WHITES IN CALIFORNIA, 1849-1970

(1977). Pertinenc sources and studies are

cited. See also, M. WEINBERG, A CHANCE TO LEARN

(1977).

13/ 1860 Cal. Stats., c. 329, § 8; see also,

1863 Cal. Stats., c. 159, § 68.

54/ See, WOLLENBERG, jnipra, at 10—14.

Ward v. Flood was later cited with approval

in Pfessy v. Ferguson. 163 U.S. 537, 545 (1896).

5_6/ General School Law of California, 5 1 662 at 14

(1880).

, 57/or economy.— However, recalcitrant districts

continue to separate black school children,— ^and

systemic segregation continued into the 20th

59/century. The most common means of segregation

has been through manipulation of student atten

dance zones, school site selection and neighbor

hood school policy.——^Following unsuccessful

efforts to exclude Ch inese,— /Japanese^-/and In

dian children— ^from public education altogether,

specific statutory authority was created for the

establishment of separate schools for Chinese,

57/ See, C. WOLLENBERG, supra, at 24-26.

58/ See, Wvsinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal. 588, 23

P. 54 (1890)..

59/ See HENDRICK, suora, at 78-80, 98-100.

60/ See, id., at.100, 103-106; see e■q., Soanqler

v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311 F. Supp.

501 (C.D. Cal. 1970). C_f. Keyes v. School Dis

trict No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 191-194 (1973).

61 / See, e.g. , Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P.

129 (1885). »i »*

82/ See, e.g. , Aoki v. Deane, discussed in WOL

LENBERG, supra, at 48-68.

63/ See, e.g. , Anderson v. Mathews, 174 Cal. 537,

163 P. 902 (1917); Piper v. Big Pine School Dist.,

193 Cal. 664, 226 P. 926 (1924).

8a

Japanese and Indian children.— The California

Education Code provided:

"§ 8003. Schools for Indian children, and

children of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian

parentage: Establishment. The governing

board of any school district may establish

separate schools for Indian children, ex

cepting children of Indians who are wards

of the United States Government and children

of all other Indians who are descendants of

the original American Indians of the United

States, and for children of Chinese, Japan

ese, or Mongolian parentage.

"S 8004. Admission of children into

other schools. When separate schools are

established for Indian children or children

of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parent

age, the Indian children or children of

Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage

shall not be admitted into any other school."

These provisions were not repealed until 1 947,— /

see Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, supra, 404 U.S.

1215.

The repeal of California school segregation

statutes seven years before this Court's invali-

64 /

64/ 1885 Cal. Stats., c. 117, S 1662 (Chinese);

1893 Cal. Stats., c. 193, S 1662 (Indians); 1921

Cal. Stats., c. 685, § 1 (Japanese). The 1893

Indian provision was amended in 1935, see infra.,

at p. 18a, n.67. See generally WOLLENBERG, supra,

at 28-107; HENDRICK, supra, at 11-59.

65/ 1947 Cal. Stats., c. 737, $ 1.

9a

dating decision in Brown v. Board of Education,

suora, was precipitated by Mendez v. Westminster

School District, 64 F. Supp. 544 (D.C Cal. 1946),

affirmed, 161 F.2d 744 (9th Cir. 1947) (en banc),

involving yet another racial minority. As was

true of the southwestern states generally, see

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189,

197-198 (1973), de jure public school segregation

of Mexican-American school children was tolerated

by the State. ^While California law did not

expressly sanction separate schools, state admin

istrative authorites construed the term "Indian"

in the school segregation law to include Mexican-

Americans.— ^Mendez v. Westminster School Dis-

— / See' HENDRICK, supra, at 60-70, 81-82, 89-92;

WOLLENBERG, supra, at 109-118.

67/ California's Attorney General was of ,the view

that, "the greater portion of the population of

Mexico are Indians, and when such Indians migrate

to the United States, they are subject to the laws

applicable generally to other Indians." 22

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, OPINIONS OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL, Opinion 6735a (January 23, 1930)

931-932 (1930). The legislature then amended the

separate school law to exclude from coverage

"children of Indians who are wards of the United

States Government and children of all other

Indians who are descendants of the original

American Indians of the United States," 1935 Cal.

Stats., c. 488, §§ 1, 2. As a result, most

10a

trict, supra, held that "the general and continu

ous segregation in separate schools of the chil

dren of Mexican ancestry from the rest of the

elementary school population" in four Orange

County districts was impermissible under the

Fourteenth Amendment. As was the case with the

6 8 /other racial minorities,— segregation of Mexican-

American children in public schools was part and

parcel of general state-imposed racially dis

criminatory policies and practices.— ^

The 1940's and the 1950's witnessed an ac

celerated rate of segregation as a result of rapid

in-migration of minority groups and the actions of

districts in drawing school attendance areas.— ^

67/ cont'd.

American Indians were excluded from coverage but

Mexican-Americans included, see, HENDRICK, supra,

at 87; WEINBERG, supra, at 166.

63/ See, e.g. , Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886); Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948);

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U.S.

410 (1948).

69/ See, e.g. , Lopez v, Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769

(S.D. Cal. 1944) (exclusion from municipal park and

swimming pool); Perez v. Sharp., 32 Cal. 2d 711,

198 P.2d 17 (1948) (miscegenation).

70/ See, HENDRICK, supra, at 104-106; c_f., Romero

v. Weakley, 226 F.2d 399 (9th Cir. 1955).

11a

Thus, in the State Department of Education's first

statewide survey of racial distribution in school

districts in 1966, it was concluded that, "despite

efforts to implement the policies of the State

Board of Education and tha progress made by the

Department of Education, the task of eliminating

segregation and providing equal educational oppor

tunities remains formidable. "— ^As the recent

cases decided in the decade since demonstrate,

supra, "the force of the earlier segregation

police has [not] been dissipated," Guey Heunc Lee

v. Johnson, supra, 347 U.S. at 1216.

Studies have documented some of the deleteri

ous effects of this educational deprivation. See,

e.q., GOVERNOR'S COMMISSION ON THE LOS ANGELES

RIOTS, VIOLENCE IN THE CITY 49 et seq., (1965);

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, ASSEMBLY PERMANENT SUBCOM.

ON POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION, UNEQUAL ACCESS TO

COLLEGE (1975). See generally U.S. CIVIL RIGHTS

COMMISSION, MEXICAN AMERICAN EDUCATION STUDY,

REPORTS I-VI (1971-1974) (comprehensive study of

Mexican-American public school segregation in the

71/ CALIFORNIA STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION,

RACIAL AND ETHNIC SURVEY OF CALIFORNIA'S PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, FALL 1966, iii (1967).

12a

southewestern states, including California). "A

predicate for minority access to quality post

graduate programs is a viable, coordinated ...

higher education policy that takes into account the

special problems of minority students."— It was

72/ Adams v. Richardson, 480 F. 2d 1159, 1165

(D.C. Cir. 1973). In Adams, the D. C. Circuit

analyzed the requirements of Title VI for State

systems of higher education, and concluded that,

"The problem of intergrating higher

educatin must be dealt with on a state-wide

rather than a school-by-school basis.10/ Per

haps the most serious problem in this area

is the lack of state-wide planning to provide

more and better trained minority group

doctors, lawyers, engineers and other profes

sionals. A predicate for minority access to

quality post graduate programs is a viable,

coordinated state-wide higher education

policy that takes into account the special

problems of minority students.

10/ It is important to note that we

are not here discussing discriminatory

admissions policies of indiviual institutions.

... This controversy concerns the more

complex problem of system-wide racial im

balance. "

Id. at 1164-1165. In the next section, we show

that the State of California has done precisely

this, viz. formulated a state-wide higher educa

tion policy that seeks to overcome discrimination

at lower levels of public education.

13a

therefore appropriate for the University of

California-Davis medical school in framing its

admissions policies "to consider whether ...

educational requirement[s] ha[ve] the 'effect of

denying ... the right [to public higher education]

on account of race or color' because the State or

subdivision which seeks to impose the require

ment [s] has maintained separate and inferior

schools for its [minority] residents," Gaston

County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285, 293 (1969).

Oregon v.Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112, 1333 (1970).

2. California's Postsecondary Effort to Over

come the Effects of Racial Segregation at

Lower Levels of Public Education

The entire public higher education system of

the State of California is under a duty imposed

by state law to "[address] and overcomfe] ...

ethnic ... underrepresentation in the makeup of

the student bodies of institutions of public

higher education,"— ^This deliberate State

policy sanctions the race-conscious admissions

program of the University of California-Davis

73/ California Assembly Concurrent Resolution

No. 151, 1974 Cal. Stats., Res. c. 209.

14a

medical school.— ^

In 1960, Caliornia's Master Plan for Higher

Education stipulated that up to two percent

of the undergraduate body of the University of

California, the California State University and

Colleges, and the California Community Colleges be

admitted as exceptions to the general admission

„ 75/requirements.— Pursuant to this authority the

University of California in 1964-65, and the State

Colleges in 1 966-1 967—-^began to establish

various undergraduate "Equal Opportunity Programs"

to increase opportunities for "socio-economically

disadvantaged" students——^through recruitment,

74/ See, e.g., CALIFORNIA POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION

COMMISSION, PLANNING FOR POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION

IN CALIFORNIA: A FIVE YEAR PLAN UPDATE 33,

n.—7( 1977) .

75/ CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, ASSEMBLY, A MASTER

PLAN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION IN CALIFORNIA, 1960-1975

p. 12 (1960). The Master Plan was approved by the

State Board of Education and the Regents of the

University of California December 18, 1959, ^d. at

6. The Master Plan was formulated pursuant to

authority conferred by the legislature, 1959

Cal. Stats., Res. c. 160.

76/ The California Community Colleges instituted

its program in 1969-1970, infra.

22/ "Initially, under the terms of the 1960

Master Plan, the number of authorized

exceptions to the basic state college and

University admissions rules were limited

15a

tutoring, financial aid, ate.— ' In order ..t0

7 7/ co nt ' d .

to the equivalent of 22 of the number of

applicants expected to be admitted as

freshmen and as transfer students. The

figure of 2Z was recommended by the Master

Plan Survey Team without any particular

justification, except that it would provide

some release from the basic rule in the case

of athletes and others whom the state col

leges and University might wish to admit.

"As the pressure to admit more disad

vantaged students began to increase, the

pressure to admit a greater number of excep

tions also increased. A careful examination

of the way the campuses were actually using

the allotted 22 revealed, to no one’s sur

prise, that it was being used primarily for

athletes and others with special talents or

attributes which the campuses wanted. For

1966 it was found that among the freshmen

admitted as exceptions by both segments, less

than 2 of 10 could be termed disadvantaged.

And the figure was less than 1 in 10 for

those admitted to advanced standing. In the

following year, 1967, as pressure continued

to mount for the admission of disadvantaged

students, these figures began to show some

improvement, but the number of exceptions who

were also disadvantaged remained well below

5 02. "

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON HIGHER

EDUCATION, THE CHALLENGE OF ACHIEVEMENT: A REPORT

ON PUBLIC AND PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION IN CALIFOR

NIA 77 (1969).

12/ CALIFORNIA POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION COMMIS-

16a

readjust some of the past practices which have

contributed to the problems of 'minority and

78/ cont'd.

SION, PLANNING FOR POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION IN

CALIFORNIA: A FIVE YEAR PLAN UPDATE, 1977-1982,

32-34 (1977) describes the affirmative action and

related programs of the three branches of Califor

nia's higher education system:

"University of California: In 1964, the

University of California established an

Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) de

signed to increase the enrollment of disad

vantaged students at the undergraduate level.

Supported by the University's own funds and

those from federal financial aid programs,

this program has grown from an enrollment of

100 students and a budget of 5100,000 in

1965, to an enrollment of over 8,000 students

with a budget in excess of $17 million.

"Dissatisfied with the growth in minority

enrollments, the University in 1975 initiated

an expanded Student Affirmative Action

program to supplement the activities of

campus EOPs. ...

* * *

"The University also has initiated a

variety of programs at the graduate and

professional level to increase the enrollment

of students from underrepresented groups.

Generally, these programs include special

recruitment efforts and academic support

services. As a result, the enrollment of

Black and Chicano students at the graduate

level increased from 3 percent in 1978

17a

disadvantaged' populations" and "to attack one of

the root causes of social inequality— the lack of

78/ cont'd.

to 10.7 percent in 1972. Since then, Chicano

graduate enrollments have continued to

increase but Black graduate enrollments have

declined.

"Finally, the University is authorized to

admit up to 4 percent of its entering stu

dents under a special program which provides

for the admission of students who demonstrate

potential for success but do not fully meet

the regular entrance requirements.

"California State Universitry and Col

leges: Approximately $5.5 million in

State funds were allocated to the California

State University and Colleges in 1974-75 for

its Educational Opportunity Program, which

served 13,585 students that year. For 1976—

77, the State University projects that it

will serve 19,439 students with a total of

$10,182,138 in State appropriations ($6,129,-

041 in grants and $4,053,097 in support

services). EOP funds provide not only

financial aid, but also a number of student

support services such as personal and aca

demic counseling. In addition, the State

University is experimenting with alternative

admissions standards on several campuses.

The State University system also is author

ized to admit up to 4 percent of its entering

freshmen class in exception to regular ad

mission requirments, with a similar percent

age for lower division transfer students....

18a

education. — The systematic underrepresentation

of minority groups at successive levels of Cali

fornia public education was cited as the rationale

79/

78/ cont'd.

"California Community Colleges: Extended

Opportunity Programs and Services of the

California Community Colleges reached ap

proximately 37,000 students in 1974-75 with a

State appropriation of $6.7 million.

For 1976-77, those funds were increased to

$11.4 million. The EOPS program was the

result of specific legislation (SB 164, 1969)

which identified the unique purposes for

allocating State funds in this area. The

Community Colleges report that the State

dollars are put at the disposal of students

either through student support services

(such as academic and personal counseling,

tutoring, and financial aid counseling), or

through direct grants and work/study pro

grams . *

Compare CALIFORNIA LEGISLATIVE JOINT COM. OF

HIGHER EDUCATION, THE CHALLENGE OF ACHIEVEMENT: A

REPORT ON PUBLIC AND PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION IN

CALIFORNIA 65-80 (1969); CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE

JOINT COM. ON HIGHER EDUCATION, K. MARTYN, IN

CREASING OPPORTUNITIES FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS,

PRELIMINARY OUTLINE (1967).

7_9/ CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, H. KITANO & D. MILLER, AN ASSESSMENT OF

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS IN CALIFORNIA

HIGHER EDUCATION 2 (1970).

19a

for the programs.— 'Reviewing the programs in

1966, the California Coordinating Council on

80/ See, e.g. , California Legislature, Joint Com.

on Higher Education, The Challenge of Achievement,

supra, at 66 (Table 6.1):

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISTRIBUTION OF ENROLL

MENT FOR CALIFORNIA PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND

PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION, FALL 1967

Chinese,

Level of Spanish Japanese, American

Enrollment Surname Negro Korean Indian

Elementary

Grades

(K—3) 14.4% 8.6% 2.1% .3%

High School

Grades (9-12) 11.6 7.0 2.1 .2

All Grades

K-12

Junior

Colleges

California

State

Colleges

University of *California— .7 .3 4.6 .2

13.7 8.2 2.1 .3

7.5 6.1 2.9 .1

2.9 2.9 1.9 .7

* Excludes Berkeley Campus.

20a

Higher Education— 'advised higher education

bodies "to explore ways of expanding efforts to

stimulate students from disadvantaged situations

81/

80/ cont'd.

Level of

Enrollment

Other Other

Nonwhite White

Elementary

Grades

(K-8) .7% 73.9%

High School

Grades (9-12) .5 78.6

All Grades

K-12 .7 75.1

Junior

Colleges .8 32.6

California

.State

Colleges -- 90. 1

University of ★California— -- 93.7 *

* Excludes Berkeley Campus.

81/ The Council was renamed the California Post

secondary Education Commission.

21a

to seek higher education"— and, as part of that

directed that consideration be given to

expanding the two percent exception by an addi

tional two percent to accommodate disadvantaged

students not otherwise eligible.— ^ Two years

later, the Council recommended, and the University

and State Colleges accepted an expansion of the

programs by raising the ceiling to four per cent,

with at least half the exceptions reserved for

disadvantaged students.— '/ Criticism of the

exception as unduly narrow, however, contin u e d ^

82/

§1/ CALIFORNIA COORRDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, K. MARTYN, INCREASING OPPORTUNITIES

IN HIGHER EDUCATION FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS,

supra at 7 (1966).

83/ Id.

84/ See, CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON

HIGHER EDUCATION, THE CHALLENGE OF ACHIEVEMENT:

A REPORT ON PUBLIC AND PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION

IN CALIFORNIA, supra, 78.

85/ For instance, the Joint Committee on Higher

Education's report, _i£. , criticized the four per

cent ceiling as "arbitrary" and limiting, and

suggested a ten per cent ceiling that would per

mit "a real effort on the part of the two four-

year segments to expand opportunities for dis

advantaged students." The report also called

for a general reappraisal of California higher

education policies and stated that:

22a

After further s t u d y t h e California Legisla

ture enacted Assembly Concurrent Resolution No.

151 (1974) to provide, in pertinent part, that:

85/ cont'd.

"To many institutions, in the name of main

taining standards, have excluded those who

would benefit most from further education.

For these reasons we believe that current

admissions policies among California's public

institutions of higher education should be

very carefully and thoroughly reexamined."

Id. at 80.

86/ "In the 1960 Master Plan for Higher

Education, California committed itself to

provide a place in higher education to every

high school graduate or eighteen-year-old

able and motivated to benefit. Calfornia

became the first state or society in the

history of the world to make such a commit

ment. We reaffirm this pledge.

* * *

"Our achievements in extending equal

access have not met our promises. Though

we have made considerable progress in the

1060 s and 1970's, equality of opportunity '

in postsecondary education is still a goal

rather than a reality. Economic and social

conditions and early schooling must be

significantly improved before equal opportun

ity can be realized. But there is much that

can be done by and through higher education."

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON THE MASTER

PLAN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION, REPORT 33, 37 (1973).

23a

"WHEREAS, The Legislature recognizes

that certain groups, as characterized

by sex, ethnic, or economic background, are

underrepresented in our institutions of

public higher education as compared to the

proportion of these groups among recent

California high school graduates; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislatue that such underrepresentation be

addressed and overcome by 1980; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature that this underrepresentation

be eliminated by providing additional student

spaces rather than by rejecting any qualified

student; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature to commit the resourcs to imple

ment this policy; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature that institutions of public

higher education shall consider the following

methods for fulfilling this policy:

(a) Affirmative efforts to search

out and contact qualified students.

86/ cont'd.

The report recommended that, inter alia, "Each

segment of California public higher education

shall strive to approximate by 1980 the general

ethnic, sexual and economic composition of the

recent California high school graduates," at 38,

and is the principle legislative history of

Assembly Concurrent Resolution Wo. 151.

24a

(b) Experimentation to discover

alternate means of evaluating student

potential.

(c) Augmented student financial

assistance programs.

(d) Improved counseling for disad

vantaged students;

now, therefore, be it

"Resolved by the Assembly of the State

of California, the Senate thereof concurring.

That the Regents of the University of Cali

fornia, the Trustees of the California State

University of Colleges, and the Board of

Governors of the California Community Col

leges are hereby requested to prepare a plan

that will provide for addressing and over

coming, by 1980, ethnic, economic, and sexu

al underrpresentation in the makeup of the

student bodies of institutions of public

higher education as compared to the general

ethnic, economic, and sexual composition of

recent California high school graduates ...”

"In adopting Assembly Concurrent Resolution

151 (1974) the Legislature acknoledged that

additional effort by colleges and universities is

necessary to overcome underrepresentation of

ethnic minorities and the poor," CALIFORNIA

LEGISLATURE, ASSEMBLY PERMANENT SUBCOM. ON POST

SECONDARY EDUCATION, UNEQUAL ACCESS TO COLLEGE 1

(1975).

California's public higher education affir

mative action effort has been predicated on

25a

the need to increase educational opportunities of

persons disadvantaged by financial, geographic,

academic and motivational barriers.— ^ The docu-

cumented effect of such artificial barriers to ex

clude many disadvantaged students, particularly

minority students, from higher education in Cali

fornia was the spur to affirmative action.— ^

Moreover, it is evident that individuals of

low-income minority groups suffer from double dis-

87/ CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, H. KITANO & D. MILLER, AN ASSESSMENT

OF EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS IN CALIFORNIA

HIGHER EDUCATION, supra, at 9; CALIFORNIA LEGISLA

TURE, JOINT COMMITTEE ON HIGHER EDUCATION, K.

m a r t y n, Increasing opprtunities for disad-

VANTAED STUDENTS, PRELIMINATRY OUTLINE, supra;

CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER EDU

CATION. K. MARTYN, INCREASING OPPRTUNITIES IN

HIGHER EDUCATION FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS,

supra, at 10-11.

88/ See, e_;_£. , CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT

COM. ON HIGHER EDUCATION, K. MARTYN, INCREASING

OPPORTUNITIES FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS, PRELIMI

NARY OUTLINE, supra, at 3-14; CALIFORNIA LEGISLA

TURE, JOINT COM. ON HIGHER EDUCATION, THE CHAL

LENGE OF ACHIEVEMENT: A REPORT ON PUBLIC AND

PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION IN CALIFORNIA, supra, at

66-67; CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, ASSEMBLY PERMANENT

SUBCOM. ON POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION, UNEQUAL ACCESS

TO COLLEGE, supra; CALIFORNIA POSTSECONDARY

EDUCATION COMMISSION, EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY

IN CALIFORNIA POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION: PART

I 406, Appendix B at B-1 — B-11 (1976).

26a

crimination.— 'California's public higher

education system has been characterized as "in

herently racist because socioeconomic and cultural

condidtions in the early experience of minority

persons leave them unable to measure up to the

,,90/admissions standards of the four-year segements. —

"... [0]ne of the most serious blocks to

participation in higher education for minor

ity students occurs in the secondary educa

tional system. Students from [black and

Mexican-American] minority groups tend to be

systematically underrepresented at each suc-

91 /cessive level of educational attainment."—

"The importance of the high school experience on

the [minority] student's opportunity to attend

college cannot be too heavily emphasized." 92/ Thus,

89/

89/ See, e.g., CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM.

ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION, REPORT,

supra, at 37-38.

90/ Id., at 47.

91/ CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, H. KITANO & D. MILLER, AN ASSESSMENT OF

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS IN CALIFORNIA

HIGHER EDUCATION, supra, at 3.

92/ CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON THE

MASTER PLAN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION, R. LOPEZ S, D.

ENOS, CHICANOS AND PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION IN

CALIFORNIA 14 (1972). This report is one of a

series that analyzes problems and available

affirmative action efforts from the perspective of

27a

while the proportion of high school seniors

eligible for entrance into the University of

California and State University and Colleges (on

the basis of grades and test scores) increases

with family income for all students, the proportion

of minority seniors is consistently lower.— ^The

percentage of eligible minority race seniors who

actually matriculate also is a fraction of the

percentage of eligible white seniors.M/Such

trends persist in the college and post-college

92/ cont'd.

various minority groups. See also, CALIFORNIA

LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR

HIGEHR EDUCATION, R. YOSKIOKA, ASIAN-AMERICANS AND

PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION IN CALIFORNIA (1973);

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE, JOINT COM. ON THE MASTER

PLAN FOR HIGHER EDUCATION, NAIROIBI RESEARCH

INST., BLACKS AND PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION IN

CALIFORNIA (1973).

93/ CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, H. KITANO & D. MILLER, AN ASSESSMENT OF

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS IN CALIFORNIA

HIGHER EDUCATION, supra, at 4-5; CALIFORNIA

LEGISLATURE, ASSEMBLY PERMANENT SUBCOM. ON

POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION, UNEQUAL ACCESS TO COL

LEGE, supra, at 7 et seq. ; CALIFORNIA POST

SECONDARY EDUCATION COMMISSION, EQUAL EDUCATIONAL

OPPORTUNITY IN CALIFORNIA POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION:

PART I, supra, at 5-6.

94/ Id.

28a

careers of minority students.—

In a comprehensive review of the State of

California's higher education affirmative action

programs, the California Postsecondary Commission

concludes that more rather than less is required,

EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPRTUNITY IN CALIFORNIA

POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION: PART II (publication

pending).

95/

95/ CALIFORNIA COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR HIGHER

EDUCATION, H. KITANO & D. MILLER, AN ASSESSMENT OF

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS IN CALIFORNIA

HIGHER EDUCATION, supra, at viii; authorities

cited supr3 at p. 29a, n.92.

29a

'

»