Tennessee v. Garner Motion to Affirm or Dismiss and Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tennessee v. Garner Motion to Affirm or Dismiss and Brief in Opposition, 1983. a866aed3-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16831472-a796-495c-b8e1-44f58aafdac6/tennessee-v-garner-motion-to-affirm-or-dismiss-and-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

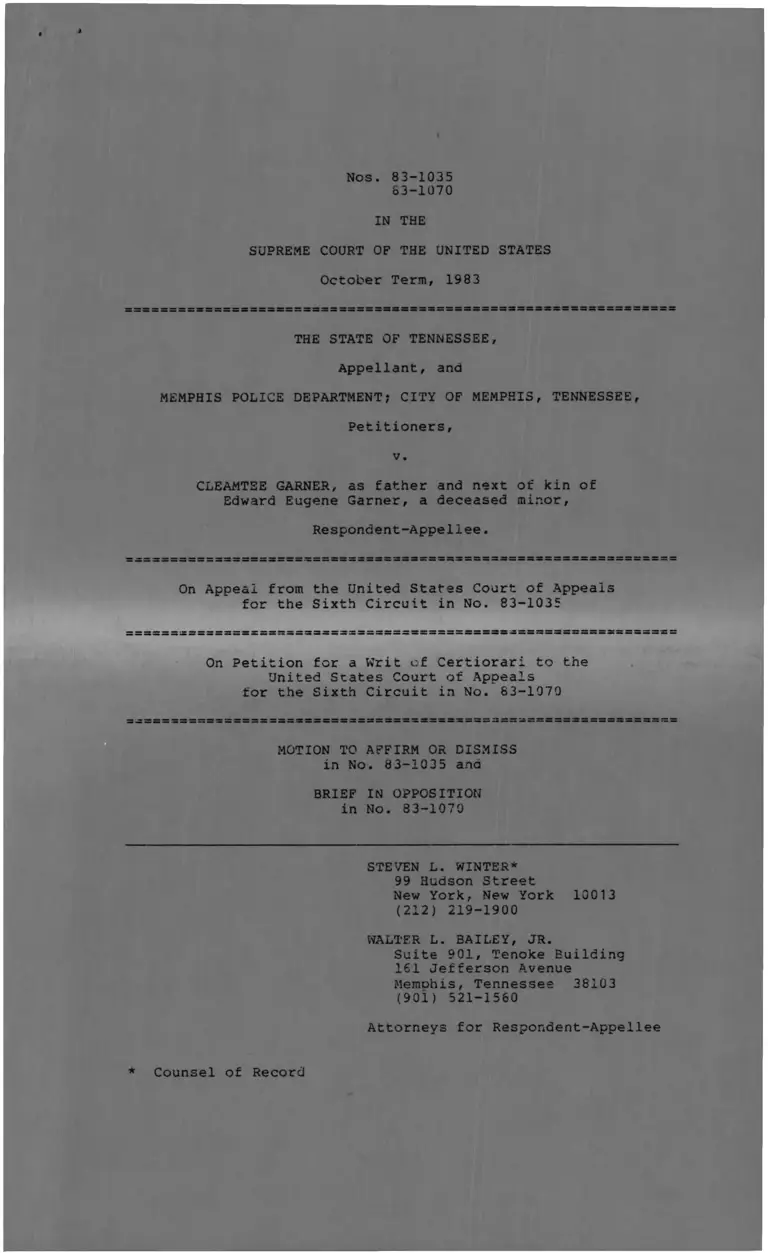

Nos. 83-1035

83-1070

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1983

THE STATE OF TENNESSEE,

Appellant, and

MEMPHIS POLICE DEPARTMENT; CITY OF MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE,

Petitioners,

v.

CLEAMTSE GARNER, as father and next of kin of

Edward Eugene Garner, a deceased minor,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in No. 83-1035

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in No. 83-1970

MOTION TO AFFIRM OR DISMISS

in No. 83-1035 and

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

in No. 83-1070

STEVEN L. WINTER*

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

WALTER L. BAILEY, JR.

Suite 901, Tenoke Euilding

161 Jefferson Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

(90l) 521-1560

Attorneys for Respondent-Appellee

* Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Does a state statute that confers unlimited discretion

on police officers to shoot nondangerous, fleeing

felony suspects whom they reasonably assume to be

unarmed violate the fourth, sixth, eighth and

fourteenth amendments?

Does a municipal policy and custom of liberal use

of deadly force that results in the excessive

and unnecessary use of such force to stop nondangerous,

fleeing felony suspects violate the fourth, sixth,

eighth and fourteenth amendments?

Is the Memphis policy authorizing the discretionary

shooting of nondangerous, fleeing property crime

suspects racially discriminatory?

f

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ................................ i

Table of Authorities ............................... iii

Opinions Below ...................................... 1

Statement of the Case .............................. 2

Statement of Facts ................................. 3

Reasons for Denying Review ......................... 6

I. The Court of Appeals Correctly Held

that a State Statute that Confers

Unlimited Discretion on Police

Officers to Shoot Nondangerous,

Fleeing Felony Suspects Whom They

Reasonably Assume to be Unarmed

Violates Established Constitutional

Principles ................................ 6

II. The Standard Adopted by the Court

of Appeals is Workable and, as a

Practical Matter, Will Not Interfere

With Law Enforcement ..................... 15

III. The Judgment Below Should be Affirmed

Because the Memphis Policy and Custom

is One of Liberal Use of Deadly Force

that Results in the Excessive and

Unnecessary Use of Such Force to Stop

Nonaangerous, Fleeing Felony Suspects .... 21

IV. Memphis's Policy Authorizing the

Discretionary Shooting of Non

dangerous, Fleeing Property Crime

Suspects Violates the Equal Protection

Clause Because it is Racially Discrim

inatory ................................... 26

Conclusion .......................................... 31

-li-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ......................

Avery v. State of Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953)....

Beech v. Melancon, 465 F.2d 425 (6th Cir. 1972) ...

Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520 (1979) ..............

Bivens v. Six Unknown Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971) .

Byrd v. Brishke, 466 F .2d 6

(7th Cir. 1972) .................................

Camara v. Municipal Court, 387 U.S. 523 (1967) ....

Carter v. Carlson, 447 F .2d 358 (D.C. Cir.

1971), rev'd on other grounds, 409 U.S.

418 (1973) .......................................

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) .........

Clark v. Ziedonis, 368 F. Supp. 544

(E.D. Wise. 1973), aff'd on other grounds,

513 F .2d 79 (7th Cir. 1975) ....................

Cunningham v. Ellington, 323 F. Supp. 1072

(W.D. Tenn. 1971) ...............................

Cupp v. Murphy, 412 U.S. 291 (1973) ...............

Dalia v. United States, 411 U.S. 238 (1979) ......

Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. 721 (1969 ) ....... .

Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979) .........■

Enmund v. Florida, ____ U.S. ____ ,

73 L.Ed.2d 1140 (1982) .........................

Florida v. Royer, 460 U.S. ____, 75

L.Ed.2d 229 (1983) .............................

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 236 (1972) ...........

Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 712 F .2d 240

(6til Cir. 1983) ................................

Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 600 F .2d 52

(6th Cir. 1979) ................................

Giant Foods, Inc. v. Scnerry, 51 Md. App.

586, 544 A.2a 483 (1982) .......................

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) ............

Cases:

30

31

22

12

7

12

10

12

31

1 6

22

9

9

9 , 11

9

1 4 - 1 5

1 1

26

passim

2, 3 , 1 4 , 26

16, 17 , 18

1 0

Page

-i i i-

Gregory v. Thompson, 500 F.2d 59

(9th Cir. 1974) ................................. 1 2

Hayes v. Memphis Police Dept., 571 F .2d 357

(6th Cir. 1978) .................................... 22

Herrera v. Valentine, 653 F.2d 1220

(8th Cir. 1981) .................................... 12

Howell v. Cataldi, 464 F.2d 272 (3rd Cir. 1972) ... 12

Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651 (1977 ) ........... 1 2

Jenkins v. Averett, 424 F.2d 1228

(4th Cir. 1970) ................................. 3, 11

Johnson v. Click, 481 F.2d 1027 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1033 (1973) ............. 12, 1 3

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) ............ 7

Jones v. Marsnall, 528 F .2d 132 (2d Cir. 1975) .... 8, 13

Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144

(1963) ............................................ 12-13

Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963) ............. 9

Kortura v. Alkire, 69 C.A.3d 325, 138 Cal. Rptr.

26 (1977 ) ........................................ 16, 1 7, 1 8

Krause v. Rhodes, 570 F .2d 563

(6th Cir. 1977) ................................. 12

Landrigan v. City of Warwick,

628 F . 2a 736 (1st Cir. 1980) ................... 12

Leite v. City of Providence, 463 F. Supp.

585 (D. R.I. 1978 ) .............................. 26

McKenna v. City of Memphis, 544 F. Supp. 415

(W.D. Tenn. 1982) ............................... 22, 25

Meldrum v. State, 23 Wyom. 12, 146 P.596

(1915) ........................................... 16

Monell v. Department of Social Services,

436 U.S. 658 (1978 ) ............................. 2, 3, 13, 26

Morgan v. Labiak, 368 F .2d 338

(10th Cir. 1966 ) ................................ 12

Qualls v. Parish, 534 F.2d 690

(6th Cir. 1976 ) ................................. 22

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348

(5th Cir. 1972) ................................. 31

Scnmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757

(1966 ) ............................................. 9f

-iv-

Cases: Pa9e

Schumann v. City of St. Paul, 268 N.W.2d 903

(Minn. 1978) ..................................... 16

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945) ...... 12

State ex rel. Baumgarner v. Sims, 139

W.Va. 92, 79 S.E.2d 277 (1963) ................... 16

State v. Sundberg, 611 P.2d 44

(Alas. 1980) ..................................... 16

Teftt v. Seward, 689 F .2d 637

(6th Cir. 1982) ................................. 12

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968 ) .................. 6/ 9, 10, 11

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ...............

United States v. Calandra, 414 U.S.

338 (1974) ....................................... 9

United States v. City of Memphis, Civ. Action

C-74-286 (W.D. Tenn. 1974) ...................... 31

United States v. Clark, 31 Fed. 710

(C.C.E.D.Mich 1837) ............................. 13

United States v. Place, ___ U.S. ___,

77 L. Ed. 2d 110 (1983) ........................... 9, 10

United States v. Stokes, 506 F .2d 771

(5th Cir. 1975 ) ................................. 12

United States v. Villarin Gerena,

553 F . 2d 723 (1st Cir. 1977 ) ................... 12

Uraneck v. Lima, 359 Mass. 749, 269

N.E.2a 670 (1971 ) ............................... 16

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 224 (1976 ) .......... 31

Werner v. Hartfelder, 113 Mich. App. 747,

318 N.W. 2d 825 (1982) ........................... 17

Wiley v. Memphis Police Dept., 548 F .2d 1247

(6th Cir. 1977), aff'g, Civ. Action

No. C-73-8 (W.D. Tenn. June 30, 1975) .......... 13, 22, 24, 27

Williams v. Kelly, 624 F .2d 695

(5th Cir. 1980) ................................. 7

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ........... 7, 26

Cases: Pa£e

-v-

Constitutional and Statutory Authorities: Page

U.S. Constitution amend. IV ........................ 9

U.S. Constitution amend. XIV, § 1 ................. 7

2

2

Alaska St at. §' 11.81.3 70 ........................... 16

Cal. Penal Code § 196 (V.Test 1970) ................. 17

Hawaii Rev. Stat. Title 37, 18

16

Minn. Stat. Ann. § 609.7 ........................... 16

Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-808 (1975) ................... 3, 8, 14

Tex. Penal Code, Art. 2,

§ 9.51(c) (1974) ................................ 18

Other Authorities:

W.A. Beller & H.J. Karales, Split Second

Decisions: Snootings of and by Chicago

Police (Chicago Law Enforcement Study 1 9

4 w. r 1ackstone, Commentaries

13

M . Blumberq, The Use of Deadly Firearms by

Police Officers: The Impact of Individuals,

Communities, anc Race (Ph.D. Dissertation,

S.U.N.Y., Albany, Sch. of Crim. Justice

19

Ron 1 pn f. Schulman, Arrest Witn and Without

a Warrant, 75 U. Pa. L. Rev. 485 (192/) ...... 13

Fvfe, Obersvations on Deadly Force, 27 Crime

& Delinquency 376 (1981) ....................... 2G

Matulia, A Balance of Forces: A Report of the

international Association of Chiets or police

(National Institute of Justice 1982) .......... . 16, 17, 18, 21

^ver, Police Shootings at Minorities: Tne_

Case of Los Angeles, 52 Annals of Amer.

Acad. & Soc. Sci. 98 (1980) ................... 19

k. Perkins, Criminal Law (2d ed. 1969) ...........

-vi-

13

Ringel, Searches and Seizures, Arrests

and Cofessions, §23.7 (2d ed. 1982)

Page

16

Sherman, Execution Without Trial; Police

Homicide and the Constitution,

33 Vand. L. Rev. 71 (1980) ....................

T. Taylor, Two Studies in Constituional

Interpretation (1966) ..........................

Commission on Accreditation For Law

Enforcement Agencies, Standard for Law

Enforcement Agencies (August 1983) ............

Community Relations Service, United States

Department of Justice, Mempnis Police

and Minority Community: A Critique (May 1984) .

Comment, Deadly Force to Arrest: Triggering

Constitutional Review, 11 Harv. Civ. Rights-

Civ. Lib.L. Rev. 360 (976) ....................

Mote, Legalized Murder of a Fleeing Felon,

15 Va. L. Rev. 582 (1929) .....................

Note, Tne Use of Deadly Force in Arizona

by Police Officers, 1972 L.& Soc. Order

481 .............................................

Staff Report to the Michigan Civil Rights

Commission, (May 18, 1981) ....................

12-13

13

21

31

13, 16-17

13

13

17

-vi l-

Mos. 83-1035

83-1070

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1983

THE STATE OF TENNESSEE,

Appellant, and

MEMPHIS POLICE DEPARTMENT; CITY OF MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE,

Petitioners,

v.

CLEAMTEE GARNER, as father and next of kin of

Edward Eugene Garner, a deceased minor,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in No. 83-1035

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in No. 83-1070

MOTION TO AFFIRM OR DISMISS

in No. 83-1035 and

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

in No. 83-1070

Respondent-appellee, CLEAMTEE GARNER, respectfully

submits that his motion to affirm the judgment below or dismiss

the appeal in No. 83-1035 should be granted and that the petition

for a writ of certiorari in No. 83-1070 should be deniea.

OPINIONS EFLCV7

The decision of the United States Court of Appeals tor

the Sixth Circuit, rendered on June 16, 1983, is reported as

Garner v. Mempnis Police Dept., 712 F .2d 240 (6th Cir. 1983).

Rehearing was denied on September 26, 1983; this order is

notea at 710 F.2d at 240 . The Sixth Circuit's prior opinion

Vis reported at bUO F.2d 52 (6th Cir. 1979).

STATEMENT OF THE CASS

Fifteen—year—old Edward Eugene Garner was shot and

Killed by a Memphis police officer on the night of October

3, 1974. On April 8, 1975, Cleamtee Garner filed "an action

for damages brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983,

1985, 1986 and 1988 to redress the deprivations of the rights,

privileges and immunities of Plaintiff's deceased son, Eaward

Eugene Garner, secured by the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution."

- 1/Complaint K 2; App. b. On August 18, 1975, the district

court entered an order dismissing the City of Memphis and

tne Memphis Police Department as defendants under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983. Trial was held on August 2 through 4, 1976. On

September 29, 1976, the district court entered a memorandum

opinion rendering judgment for the defendants.

Plaintiff appealea. The court of appeals, Chief

uudge Edwarus and Judges Merritt and Lively, reversed and

remanded the case for reconsideration in light of Monel1 v .

Department of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658 (1978). One of

tne questions that it listen for consideration on remand was

whetner "a municipality's use of deadly force under Tennessee

law to capture allegedly nondangerous felons fleeing from

*/ Citations to the opinions below are

the petition for a writ of certiorari in

designated as A. ____. Citations to the

the Joint Appendix in the Sixth Circuit

to the appendix to

No. 83-1070 and are

record below are to

ana are designated

as App.

1/ The suggestion by the state, appellant in Mo. 83-1035,

tnat the fourth amenament haa not been raised, see Jurisdictional

Statement at 5, is incorrect. Indeed, the district court

noted in its initial opinion that: "Plaintiff cited specific

ally in this regard the Fourth Amendment right to be free of

unreasonable seizure of the body ... incorporated into the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and made

applicable to the States." A. 2. See also Complaint 1| 19,

App. 11-12; Memorandum Opinion of Feb. 29, 1980, A. 21.

- 2-

nonviolent crimes [is] constitutionally permissible under

the fourth, sixth, eighth and fourteenth amendments?" Garner

v. Memphis Police Dept., 600 F.2d 52, 55 (6th Cir. 1975); A.

18. It also remanded for consideration of the question of

Mempnis's "policy or custom" for purposes of liability under

Mcnell. Id., 600 F.2d at 55; A. 15.

On remand, the district court denied plaintiff the

opportunity to introduce additional evidence on the question

of the Memphis "policy or custom," to submit an offer of

proof, or to suomit a brief on the merits; it entered judgment

for the defendants. A. 20. After consideration of plaintiff's

motion to reconsider, the court allowed the submission of a

orief and offer of proof and then again entered judgment for

the defendants. A. 31. The court of appeals, Chief Judge

Edwards and Judges Merritt and Keith, reversed. It held

that the Tennessee statute, Term. Code Ann. $ 40-808 (1975),

violated the fourth amendment and the due process clause of

the fourteenth amendment "because it authorizes the unnecessarily

severe and excessive, and therefore unreasonable," use of

deadly force to effect the "arrest" of unarmed, nonviolent,

fleeing felony suspects such as plaintiff's son. 710 F.2d

at 241; A. 40-41. Rehearing ano rehearing en banc were

denied on September 26, 1983. 710 F .2d at 240; A. 58.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

At the time of his death, Edward Eugene Garner was

fifteen-years-old. He was an obvious juvenile; slender of

build, he weighed between 85 and 100 pounds and stood only

five feet and four inches high. App. 78 and 290-91. He

-3-

nad a minor juvenile record. At the age of 12, ne and two

other boys illegally entered the house in whose yard they

were playing. App. 686 and 689. In July of 1974, his family

called the police when they discovered that he had taken a

2/jar of pennies from a neighbor's house. He was placed on

probation for one year. App. 88-89 and 689. There was also

a prior arrest for a curfew violation, but that was resolved

when it was explained that young Garner was working at a local

store and under supervision at the time. App. 84 and 693-94.

On the night of October 3, 1974, Officers Hymon and

Wright responded to a burglary in progress call at 737

Voilentine in Memphis. When they arrived at that address, a

woman was standing in the door pointing at the house next door.

Upon inquiry by Officer Hymon, she said that "she had heard

some glass breaking or something, and she knew that somebody

3/was breaking in." App. 207. Hymon went around the near

side of tne house, his revolver drawn, while Wright went around

the far side. Hymon reached the backyard first, where he

heard a door slam and saw someone run from the back of the

house. He located young Garner with his flashlight:

2/ The neighbor declined to call the police about this

minor incident. It was the family that insisted that the

police be called. App. 88-89.

3/ Hymon testified that: "Roughly I recall her saying,

'They are breaking inside....'" App. 2u7. He qualified

that testimony when he was asked: "Did you understand her

to be saying that there were several people inside the house?"

He responded: "I don't really think she knew. I think that

she — I think that she might have mentioned that she had

heard some glass breaking or something, and she knew that

somebody was breaking in. I don't think that the plural

form had any indication of her knowing." Id.

This version was corroborated by his partner, Officer

Wright. He testified that: "I was leaning over in the street

like this to hear what she was saying through the open door.

She said, 'Somebody is breaking in there right now.'" App.

707.

-4-

Garner was crouched next to a six foot cyclone fence at

the back of the yard aoout 30 to 40 feet away from Hymon.

Hyiuon was able to see one or both of Garner's hands; he

concluded that Garner was not armed. App. 239, 246-47, 658,

4/and 677.

While young Garner crouched in Hymon's flashlight

beam, Hymon identified himself and ordered Garner to halt.

Garner paused a few moments during which Hyrnon made no attempt

5/to advance, but continued to aim his revolver at Garner.

Garner bolted, attempting to jump the fence. Hymon fired,

striking young Garner in the head. Garner fell, draped over

the fence. He did not die immediately; when the paramedics

arrived on the scene "he was holding his head and just thrashing

about on the ground," App. 141, "hollering, you know, from

the pain." App. 137. Edward Eugene Garner died on the

operating table. App. 153.

4/ At his deposition, introduced into evidence, hymon

testified that: "I am reasonably sure that the individual

was not armed___ " App. 246. On direct examination by the

city at trial, Hymon was asked: "Did you know positively

whether or not he was armed?" He replied: "I assumed he

wasn't...." App. 656.

Hymon also testified that Garner did not act as an

armed suspect would, neither firing a weapon not throwing it

down. App. 246. He testified that: "I figured, well, if

he is armed I'm standing out in the light and all of the

light is on me the[n] I assume he would have made some kind

of attempt to defend himself...." App. 658. That officer

Hymon operated on the assumption that young Garner was unarmed

is further corroborated by his testimony that he "definitely"

would nave warned his partner if he had had any question

whether Garner was armed, App. 246-47, and that: "I would

have taken more cover than what I had." Id.

5/ Hymon testified that he did no more than take "a couple

of steps," App. 651, "which wasn't, you know, far enough to

make a difference." App. 256. Officer Wright testified

tiiat when he rounded the corner of the house after the shot,

Hymon "was standing still...." App. 720. According to

Wright, it took only "three or four seconds" for Hymon to

reach Garner after the shot. Id.

-5-

There was no one home when the house was broken

into. After the shooting, the police found that young Garner

had ten dollars and a coin purse taken from the house. App.

737. The owner of the house testified that the only items

missing were a coin purse containing ten dollars and a ring

belonging to his wife, but that the ring was never found.

6/The ten dollars were returned. App. 169.

Plaintiff called two expert witnesses — Chief Detective

Dan Jones of the Shelby County Sheriff's Department and

Inspector Eugene Barksdale, former commander of the personal

crimes bureau of the Memphis Police Department — to testify

about the reasonableness of Hymon's use of deadly force

under the circumstances. As the district court found: "The

substance of such testimony was to the effect that Hymon

should first have exhausted reasonable alternatives such as

giving chase and determining whether he had a reasonable

opportunity to apprehend him in some other fashion before

firing his weapon." A. 8. Both Jones and Barksdale testified

that Hymon "snould have tried to apprehend him," App. 278

ana 375; Barksdale added that "in all probability he could

have apprehended the subject without having to shoot him...."

App. 373.

REASONS FOR DENYING REVIEW

I. THE COURT OF APPEALS CORRECTLY HELD THAT A

STATE STATUTE THAT CONFERS UNLIMITED DIS

CRETION ON POLICE OFFICERS TO SHOOT NON-

DANGEROUS, FLEEING FELONY SUSPECTS WHOM THEY

REASONABLY ASSUME TO BE UNARMED VIOLATES

ESTABLISHED CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES_______

The court of appeals applied established constitu

tional principles to review a state statute that authorizes

6/ The owner also testified that: "The first -- I had some

old coins in there and when they did let me in, I went to

them. They were still there." Id.

-6-

police officers to use deadly force against nondangerous,

fleeing felony suspects. It held that the fourth amendment

applies ana that it requires reasonable methods of capturing

suspects. 710 F. 2d at 243; A. 44. As at common law — when

all felonies were capital offenses, tne fleeing felon doctrine

authorized the use of deadly force to prevent the felon's

escape — the court of appeals held that the fourth amendment

allows only the reasonable, proportioned use of deadly force

in the arrest context: i.e., "the police response must

relate to the gravity and need...." Bivens v. Six Unknown

Agents, 403 U.S. 388, 419 (1971 ) (Burger, C.J., dissenting).

Since the use of deadly force against unarmed, nonviolent

felony suspects is excessive, it violates the fourth amendment.

710 F,2a at 246; A. 51.

The court of appeals also held that the use of aeadly

force against unarmed, nonviolent felony suspects violates

due process. The due process clause explicitly protects the

right to life, U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 1; Williams

v. Kelly, 624 F.2a 695, 697 (5th Cir. 1980), a right so

axiomatic that it is an understatement to characterize it as

"fundamental." Compare Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356,

370 (1886) ("the fundamental rights to life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness"), and Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458,

462 (1938) ("fundamental human rights of life and liberty"),

with Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 102 (1958) ("the right to

have rights"). The Tennessee statute falls under the due

process clause because the state interests cannot support

the taking of life in the context of a nonviolent, nondangerous

felony. 710 F .2d at 246-47; A. 52-53.

-7-

The state and the city argue that the court of appeals

erred because the fourth amendment does no more than set the

minimum standard — i.e., probable cause for initiating

an arrest, but that it does not govern the manner of police

action in effectuating that arrest. Jurisdictional Statement

at 8-9 ; Cert. Petition at 10-11. They argue that the reliance

placed by the court of appeals on the Fourth Circuit's ruling

in Jenkins v. Averett, 424 F.2d 1228 (4th Cir. 1970), is

misplaced because in Jenkins the officer had no probable

cause to arrest and, thus, was not authorized to use any

force. Jurisdictional Statement at 8; Cert. Petition at 11.

Finally, they argue that the Court should grant review because

the decision in this case conflicts with that of the Second

Circuit in Jones v. Marshall, 528 F .2d 132 (2d Cir. 1975).

Jurisdictional Statement at 10; Cert. Petition at 10.

The state and the city are wrong on each of these

points, and the court of appeals is correct. As we show

below, the fourtn amendment plainly applies under the prin

ciples consistently enunciated by this Court and affirmed

again only last Term. Moreover, the ruling below is entirely

consistent with the decision in Jenkins and the parallel

authority in every circuit, including the Second Circuit.

The Tennessee statute at issue, Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-

808, provides that:

It, after notice of the intention to arrest the

defendant, he either flee or forcibly resist, the

officer may use all the necessary means to effect

the arrest.

Id. It is an arrest statute; there can be no suggestion

chat "such police conduct is outside the purview of tne

Fourth Amendment." Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 16 (1968). Tne

fourth amendment speaks directly to: "The right of the people

-8-

to be secure in their persons ... against unreasonable ...

seizures...." U.S. Const, amend. IV; Terry, 392 U.S.

at 16 ("It is quite plain that the Fourth Amendment governs

'seizures' of the person...."); accord United States v .

Place, ____ U.S. ____, 77 L.Ed.2d 110, 121-22 (1983); Dunaway

v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 207 (1979); Cupp v. Murphy, 412

U.S. 291, 294 (1973); Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. 721,

726-27 (1969).

Moreover, the Court has long repudiated the contention

that the fourth amendment governs only the "when" of police

action ana not the "how." Only last Term, the Court reaffirmed

what it "observed in Terry, '[t]he manner in which the seizure

...[was] conducted is, of course, as vital a part of the

inquiry as whether [it was] warranted at all.'" United

States v. Place, 77 L.Bd.2d at 121 (quoting Terry, 392 U.S.

7/at 28). in Place, the Court went on to "examine the

agents' conauct___ " id., and found it "sufficient to render

the seizure unreasonable." I_d. at 122. See Schmerber v.

California, 384 U.S. 757, 768 (1966) ("whether the means and

procedures employed ... respected relevant Fourth Amendment

standards of reasonableness"); Ker v. California, 374 U.S.

23, 38 (1963) (whether "tne method of entering the home may

offena federal constitutional standards of reasonableness");

United States v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338, 346 (1974) (subpoena

"'far too sweeping in its terms to be regarded as reasonable'

under the Fourth Amendment") (dicta); Dalia v. United States,

411 U.S. 238, 258 (1979)("the manner in which a warrant is

7/ In Terry, the Court added that: "The Fourth Amendment

proceeds as much by limitations upon the scope of governmental

action as by imposing preconditions upon its initiation."

392 U.S. at 28-29.

-9-

executed is subject to later judicial reivew as to its rea

sonableness" ) .

In determining the reasonableness of the use of deadly

force under the fourth amendment, the court of appeals followed

exactly the mode of analysis applied by this Court in considering

other forms of police action.

Terry and its progeny rests on a balancing of the

competing interests to determine the reasonableness

of the type of seizure involved within the meaning

of "the Fourth Amendment's general proscription

against unreasonable searches and seizures." 392

U.S. at 20. We must balance the nature and quality

of the intrusion on the individual's Fourth Amendment

interests against the importance of the governmental

interests alleged to justify the intrusion.

8/United States v. Place, 77 L.Ed.2d at 118. The court

of appeals looked at the "nature and quality of the intrusion:"

As an intrusion by police, the use of deadly force is "a

method 'unique in its severity and irrevocability.'" Garner,

710 F .2d at 243; A. 44 (quoting Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S.

153, 187 (1976)). It balanced this against the state's

interests and concluded that, as was true at common law, the

state interests are proportionate only when the underlying

felony is a violent one or the fleeing suspect will endanger

o/ In fact, this mode of analysis did not originate in

Terry; the Terry Court derived it from the decision in Camara

v. Municipal Court, 387 U.S. 523 (1967):

In order to assess the reasonableness of the police

conduct as a general proposition, it is necessary

"first to focus upon the governmental interest

which allegedly justifies official intrusion upon

the constitutionally protected interests of the

private citizen," for there is "no ready test for

determining reasonableness other than by balancing

the need to search [or seize] against the invasion

which the search [or seizure] entails."

Terry, 392 U.S. at 20-21 (quoting Camara, 387 U.S. at 534-

35, 536-37).

the physical safety of others. The court of appeals thus

properly applied settled fourth amendment principles and

correctly arrived at the decision below.

JenKins v. Averett, on wnich the court of appeals

relied, is consistent with this reasoning. Nownere in Jenkins

die the fourth Circuit engage in the reasoning suggested by the

state and the city: that the snooting violated the fourth

amendment because there was no probable cause to arrest. To

tne contrary, the Fourth Circuit never discussed whether the

police were authorized to stop Jenkins. Rather, the vice it

found was that "our plaintiff was subjected to the reckless use

of excessive force." 424 F .2d at 1232 (emphasis added).

Jenkins was premised on the principle that the fourth

amendment protects the "inestimable right of personal security."

la., 424 F .2d at 1232 (quoting Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. at 8-

9). Accord Florida v. Royer, 460 U.S. ____, 75 L.Ed.2d 229,

238 (1983); Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. at 726-27 ("Nothing

is more clear than that the Fourth Amendment was meant to

prevent wholesale intrusions upon the personal security of our

citizenry...."). As such, the fourth amendment "shield covers

the individual's physical integrity." Jenkins, 424 F.2d at

232. See Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. at 767 ("we are dealing

with intrusions into the human body"). Every circuit has

concurred in this conclusion, although most now follow the

1/

9/ The city argues that the court of appeals "failtedj to

recognize the valid state interests encompassed by the statute....

Cert. Petition at 11. This is false. The scope of the

state interests in the use of deadly force were fully briefed

in the court below. Brief for Appellees at 13; Brief for

Appellant at 21-28, 33-35. They will not be recapitulated

here because of the necessary length of such a discussion.

Suffice it to note that the question was fully considered by

the court below; it simply decided the issue adverse to the

city.

-1 1-

leadSecond Circuit's lead as articulated by Judge Friendly in

Johnson v. Glick, 481 F.2d 1028 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 414

U.S. 1033 (1973), that "quite apart from any 'specific' of the

Bill of Rights, application of undue force oy law enforcement

officers deprives a suspect of liberty without due process of

law." Id. at 1032; accord Landrigan v. City of Warwick, 628

F.2c 736, 741-42 (1st Cir. 1980) (citing United States v.

Villann Gerena, 553 F.2d 723, 728 (1st Cir. 1977) (fourth and

fifth amendments)); Howell v. Cataldi, 464 F.2d 272 (3rd Cir.

1972); United States v. Stokes, 506 F.2d 771, 775-76 (5th Cir.

1975); Tefft v. Seward 689 F.2d 637, 639 n. 1 (6th Cir. 1982);

Byrd v. Brishke, 466 F.2d 6 (7th Cir. 1972); Herrera v. Valentine,

653 F .2d 1220, 1229 (8th Cir. 1981); Gregory v. Thompson,

500 F.2G 59 (9th Cir. 1974); Morgan v. Labiak, 368 F.2d 338

(ICth Cir. 1966); Carter v. Carlson, 447 F .2d 358 (D.C. Cir.

1971), rev'a on other grounds, 409 U.S. 418 (1973). The

court of appeals simply applied the well established prin

ciple that excessive force by law enforcement personnel

violates the fourth amendment and the due process clause to

10/the facts of this case.

10/ In the courts below, respondent-appellee advanced another,

estaolished, aue process principle that supports the judgment.

The due process clause provides "protection against punishment

without due process of law...." Sell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S.

520, 535 (1979); accorG Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651,

671-72 n. 40 (1977); Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S.

144, 165-67 (1963); Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91,

106 (1945); Krause v. Rhodes, 570 F.2d 563, 572 (6th Cir.

1977). Application of the seven iMendoza-Martinez criteria,

citea in Wolfish as "useful guideposts," 441 U.S. at 538,

establishes that the shooting of nondangerous, fleeing felony

suspects "amounts to punishment," _id. at 535, in violation

of the due process clause. Sherman, Execution Without Trial:

Police Homicide and the Constitution, 33 Vand. L. Rev. 71

(1980). This conclusion is particularly supported by the

history of the common law fleeing felon doctrine, whicn was

a direct outgrowth of the application of capital punishment

and, in its earliest incarnations, summary punishment for

-12-

The state and city's argument that the decision below

is in conflict with the Second Circuit opinion in Jones v .

Marshall is simply wrong. Jones was decided before Monel1.

Jones decided only the question of the privilege the police

officer could invoke under § 1983, not the substantive con

stitutional question under the fourteenth amendment.

Id., 528 F .2d at 137, 138, 140, 142. Indeed, it expressly

rejected the view of the defendant in that case that the

Connecticut statute was constitutional and that no further

analysis was necessary. Id♦ at 137. Rather, it noted that

Johnson v. Glick provides the 'controlling constitutional

principle, id. at 139, declined to assess the balance of

the competing interests, id. at 142, and instead incorporated

the Connecticut rule of the officer's privilege as a defense

to the s 1983 action. Id. at 138, 142. Thus, the opinion

in Jones is in striding conformity with the rulings of the

court of appeals in this case. On the first appeal, the

Sixth Circuit held that the officer was entitled to invoke

the qualified privilege of good faith reliance on state law.

10/ continued

all felonies. Sherman, supra, at 81; see also 4 W. Blackstone,

Commentaries 98 (Garland ed. 1978); United States v. Clark,

31 Fed. 710, 713 (C.C.E.D.Mich. 1887); Bohlen & Schulman,

Arrest With and Without a Warrant, 75 U. Pa. L. Rev. 485,

495 (1927); Note, Legalized Muraer of a Fleeing Felon, 15

Va. L. Rev. 582, 583 (1929); T. Taylor, Two Studies in Con

stitutional Interpretation 28 (1968); R. Perkins, Criminal Law

10 (2d ed. 1969) ; Note, The Use of Deadly Force in Arizona by

Police Officers, 1972 L. & Soc. Order 481, 482; Comment, Deadly

Force to Arrest: Triggering Constitutional Review, 11 Harv.

Civ. Rights & Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 361, 365 (1974). In addition,

the Memphis policy promotes one of "tne traditional aims of

punishment." Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. at 168-69. The

record establishes "tnat one of the principal purposes of

wempnis's policy ... is to deter criminal conduct." Wiley,

v. Memphis Police Dept., Civ. Action No. C-73-8, Slip op. at 13

(W.D. Tenn. June 30, 1975); see App. 962, 1832-33 and 1848-50.

Neither of the courts below, however, addressed this aspect of

the due process issue.

-13-

Garner, 600 F .2d at 54; A. 16-A. 17. On the second appeal, it

reached the constitutional question not decided in Jones and

held the state statute unconstitutional. 710 F.2d at 246-

47; A. 51-A. 53.

The city makes one last argument against the balance

of competing interests struck by the court of appeals. Without

any supporting authority, it asserts that "the nighttime

breaking and entering a dwelling is a crime so frequently

associated with the commission of violence...." Cert. Petition

at 13. But there is no evidence in the record to support

1 Vthis bald assertion.— Nor has the Tennessee legislature

ever made such a factual determination. The statute at issue in

this case was passed in 1858 and merely codified the then existing

common law, Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-808; the Tennessee legislature

lias never held hearings on this question.

The available evidence is to the contrary. As the

Court has observed,

competent observers have concluded that there is

no basis in experience for the notion that death

so frequently occurs in the course of a felony

for which killing is not an essential ingredient....

This conclusion was based on three comparisons of

robbery statistics, each of which showed that only

about one-half or one percent of robberies resulted

in homicide. The most recent national crime statistics

strongly support this conclusion.

11/ This argument is, in fact, inconsistent with the city's

position in the prior cases and that expressed in the record

in this case. Tne mayor of Memphis has on several occasions

testified under oath regarding the reasons for the Memphis

policy allowing the officer discretion to shoot unarmed

burlgary suspects. On those occasions, he has testified

that the policy is justified not because burglars commit

violence in connections with that crime, but because they

graduate to commit subsequent crimes of violence. App. 961;

App. ia32-34.

Enmund v. Florida, ____ U.S. ____ 73 L.Ed.2d 1140, 1153

(19b2) (citations and footnotes omitted). In light of the

fact that this is so for robbery, a crime that by definition

involves the use of force or the threatened use of force,

the city's assertion with regard to burglary is highly ques

tionable.

In sum, the court of appeals applied well established

fourth amendment principles as enunciated by this Court. It

applied principles under the fourth amendment and the due

process clause that are consistent with the holdings of

every circuit in tne country. The decision below is correct,

and review by this Court is unnecessary.

II. THE STANDARD ADOPTED 3Y THE COURT OF APPEALS

IS WORKABLE AND, AS A PRACTICAL MATTER, WILL

not i nt er f er e with l a w e n f o r c e m e n t__________

The state and the city argue that the rule adopted by the

court of appeals "places burdensome and impractical constraints

on effective law enforcement," Jurisdictional Statement at 7,

and that it "will create much confusion among law enforcement

officers...." Cert. Petition at 11. That is simply not so.

Tne court of appeals has adopted a standard that is clear,

workable, and not unduly restrictive of law enforcement.

Before an officer uses deadly force to stop a fleeing felony

suspect, he or she must have "an objective, reasonable basis in

fact to believe that the felon is dangerous or has committed a

violent crime." 710 F.2d at 246; A. 52.

In fact, the actual practices of most law enforcement

agencies demonstrate the practicability of the standard adopted

by the court of appeals. Most jurisdictions already restrain

the use of deadly force by police officers in a manner that is

as restrictive or more restrictive than that adopted by the

-15-

court below. The common sense of law enforcement professionals

across the nation is that these restrictive standards are

workable ana do not hamper effective law enforcement.

While some number of states still retain the common law

J_2/rule, comparatively few police departments actually operate

under that standard. Several states that ostensibly follow the

common law rule have modified it by judicial interpretation.

For example, California is normally listed as one of those

states tnat has codified the common law rule by statute. See

e .9., Matulia, A Balance of Forces: A Report of the International

Association of Chiefs of Police 17 (National Institute of

Justice 1962); Comment, Deadly Force to Arrest: Triggering

12/ The state cites Ringel, Searches and Seizures, Arrests

and Confessions, § 23.7 at 23-29 (2d ed. 1962), for the proposi

tion tnat there are 24 states with statutes adopting the common

law rule. Ringel, however, provides neither a listing of

states nor authorities. An earlier article lists 24 states

with statutes that codify the common law, Comment, Deadly Force

to Arrest: Triggering Constitutional Review, 11 Harv. Civ.

Rights - Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 360, 366 n.20 (1976), but that

listing is now incorrect. At least three of those states have

amenaea their statutes. See Alaska Stat. § 11.61.370; Iowa

Coae § 804.6; Minn. Stat. Ann. § o09.7; see Schumann v. City of

St. Paul, 268 N.W.2d 903 (Minn. 1975). Also, as indicatea in the

text, infra, some of those stares nave reaa tneir statutes more

narrowly, confining the use of deadly force to those fleeing

violent felonies. See kortuir v. Alkire, 69 C.A.3d 325, 138

Cal.Rptr. 26 (1977); State v. Sundberg, 611 P.2d 44 (Alas.

1580) (reading prior Alaska statute consistently with new

statute and limiting it to dangerous felonies); see also Clark

v. Z ieaonis, 366 F. Supp. 544, 546 (2.D.Wise. 1973 ), aff'd on

other grounds, 513 F.2d 79 (7th Cir. 1975) (reading Wisconsin

statute as limited to violent felony situations).

Several states have no statute. In these jurisdictions,

it is sometimes difficult to ascertain what rule is applied since

the case law is frequently of substantial vintage. See, e .g .,

State ex rel. baumgarner v. Sims, 139 W.Va. 92, 79 S.E.2d 277

(1963); Melaruffi v. State, 23 Wyom. 12, 146 P. 596 (1915). As

discussed infra, this may reflect the fact that few juris

dictions actually employ deadly force to stop nondangerous

fleeing felony suspects. Of the prior common law jurisdictions,

some have reaffirmed the rule in recent years, Uraneck v .

Lima, 359 Mass. 749, 269 N .E.2d 670 (1971), while others have

modified it. Giant Foods, Inc, v. Scherry, 51 Md.App. 586, 544

A.2d 483 (1982).

-16-

Constitutional Review, 11 Harv. Civ. Rights-Civ. Lib. L. Rev.

360, 368 n .30 (1976); Cal. Penal Code § 196 (West 1970). Its

courts, however, have interpreted that statute to allow the use

of deadly force against only those fleeing violent felonies.

Kortum v. Alkire, 69 C.A.3d 325, 138 Cal. Rptr. 26 (1977).

Similarly, Maryland was a common law jurisdiction, but its

courts have limited the privilege to use deadly force to

those situations involving an immediate threat of harm. Giant

Foods, Inc, v. Scherry, 51 Md. App. 586, 544 A.2d 483 (1982)

(robber fleeing without threat of violence).

More importantly, the actual practices of most police

departments are governed not by state law but by more restrictive

municipal or departmental policies. See Matulia, supra, at 153-44.

For example, Michigan is a common law jurisdiction. See Werner

v. Hartfelder, 113 Mich. App. 747, 318 N.W.2d 825 (1982). But more

than half of the local law enforcement agencies have deadly force

policies that are more restrictive than the common law ana aoout

75% of those are consonant with the standard adopted by the court

of appeals in this case. Staff Report to the Michigan Civil Rights

Commssion at 54 et seg. (May lb, 1981). This trend is particularly

true of major metropolitan areas. Although Arizona, Connecticut,

Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Ohio are common law states, Phoenix,

New Haven, Boston, Alburquerque, Santa Fe, Cincinnatti, and Dayton all

have deadly force policies that would bar the shooting in this

13/case. App. 1318, 1291 1131, 1110, 1330, 1209, & 1218.

13/ The same is true for the Memphis Police Department, whose

written policy is stricter than state law in that it prohibits

the use of deadly force against those fleeing arrest from

certain property crimes such as embezzlement. App. 1274.

Although Memphis's written policy does authorize the shooting of

fleeing burglars, it would prohibit the shooting that occurred

in this case because it applies a defense of life standard when

the fleeing suspect is a juvenile. Id.

The most recent survey of municipal deadly force policies

confirms this trend. The International Association of Chiefs

of Police ("IACP") solicited the deadly force policies of all

cities over 250,000. All but three responded. Matulia, supra,

at 153. Only four, or 7.5%, follow the common law rule. More

than half limit the use of deadly force in a manner that is

consonant with or stricter than tne standard adopted by the

court of appeals. About 40% limit the use of deadly force to

those fleeing from "atrocious" felonies; the IaCP report does

not distinguish between tnose policies that exclude burglary

11/from that category and those that include it. ^d. at 161.

The survey of municipal deadly force policies contained in the

offer of proof, although somewhat dated, is to the same effect.

The offer of proof contains the deadly force policies of 42

11/cities, including 30 of the 44 largest cities in this country.

Over 70% of these policies would bar the shooting in this case;

almost two thirds apply standards consonant with the decision

below. The record information indicates that, for the 44

11/largest cities, these figures are 84% and 77%, resepectively.

14/ The information available to respondent-appellee,

including the municipal policies contained in the offer of

proof, indicate that no more than half of these policies

include burglary as an "atrocious" felony. Thus, only about

one quarter of the municipal policies considered by the IACP

would allow the shooting in this case.

15/ Of the fourteen cities from this category that are not

represented in the offer of proof, information is available on

seven. Six of these cities — Houston, El Paso, Forth Worth,

Austin, San Antonio, and Honolulu — are in states with deadly

force statutes modeled on the Model Penal Code. Tex. Penal

Code, Art. 2, §9.51(c) (1974); Hawaii Rev. Stat. Title 37, §

703-307(3)(1976 ) . Two others — Baltimore, Maryland, and Long

Beach, California — are in states whose courts have restricted

the use of deadly force. Giant Foods, supra; Kortum v. Alkire,

supra.

16/ These figures include the seven cites discussed in n.15,

supra.

-13-

Permissive state laws and municipal policies notwithstand

ing, very few police departments actually use deadly force to

stop fleeing suspects. Only a small minority of police firearm

discharges nationwide are for the purpose of stopping nondangerous

11/fleeing felony suspects. in large part, this reflects the fact

than nanoguns are an unreliable means of effecting an arrest.

Fcr example, the record information on the use of deadly force

to stop fleeing property crime suspects in Memphis shows that

between 1969 and 1974, Memphis police used their revolvers to

attempt to stop fleeing suspects on 114 occasions, resulting in

±8/only 16 woundings and 17 deaths. App. 1460-69. Although

tne data is incomplete, it appears that a large percentage of the

suspects fired upon eluded capture. Id.; App. 957. In the words

of tne Memphis police director: "The chances are ... under the

circumstances where deadly force is used..., ne [the police officer]

will not hit [the suspectj." App. 953. He testified that

part of the reason for canning warning shots was the fact that

it had the opposite of the desired effect; it tended to spur

the fleeing suspect. He concluded that shots that miss probably

have the same effect. App. 963-64.

17/ The figures vary, of course, from city to city depending

on that city's policy. See App. 791 (11.3% in New York between

1971-1975); W.A. Beller & K.J. Karales, Split Second Decisions:

Shootings of and by Chicago Police 6 (Chicago Law Enforcement

Study Group 1981) (17% between 1974-1978); M. Mver, Police

Shootings at Minorities: The Case of Los Angeles, 52 Annals of

Amer. Mcao. of Pol. & Soc. Sci. 98, 104 (1980) (Detween 1974-1978,

15% of all shootings at blacks, 9% of all shootings at Hispanics,

and 9% of all shootings at whites); M. Blumberg, The Use of

Deadly Firearms by Police Officers: The Impact of Individuals,

Communuites, and Race 201 (Ph.D. Dissertation, S.U.N.Y., Albany,

Sch. of Crim. Justice Dec. 14, 1982) (7.8% in Atlanta between

1975-1978; between 1973-1974, 4.6% in the District of Columbia,

10% in Portland, Ore., but 58.1% in Indianapolis).

18/ This represents only about half of all firearm discharges

by Memphis police during this period. App. 1469.

Similarly, the use of deadly force in this context is

insignificant to the ability of the police to make felony

arrests. This is true in Memphis as elsewhere. Between 1969 and

1974, Memphis police attempted to make property crime arrests

with their firearms on 114 occasions, many of which were not

successful. But during this period they made more than twenty-six

thousand arrests for property crimes. App. 1767. As the

Memphis police director observed: "of all arrests how many

involve the use of deadly force, I would say it would be less

than one percent, probably less than a half percent.... [I]f

you want to even boil it down to arrests of felons I think you'd

still find it less than — well, let's say you'd find it a minute

percentage point." App. 957-58. Dr. Fyfe has observed: "[I]n

order for the police to have cleared even one percent [more] of

the nonviolent felonies [burglary, larceny, and auto larceny]

reported in 1978 through 'apprehensions effected by shooting,'

they would have had to increase the rate at which they shot

people during that year by at least fifty-fold. Doing so would

have resulted in approximately 35,000 fatalities and 70,000

woundings." Fyfe, Observations on Deadly Force, 27 Crime

& Delinquency 376, 381 (1981).

Thus, it is not suprising that, as noted above, the

majority of modern police departments no longer authorize the use

of deadly force in this context. Many, including the FBI, App.

1869, apply a strict defense of life policy. Also telling is the

11/position of professional police organizations. The

19/ Respondent-appellee recognizes that such standards "do

riot estadlisn the constitutional mimima ...," Bell v. Wolfish,

441 U.S. at 543 n.27, and does not offer them as such. Indeed,

these standards are more restrictive than that adopted by the

court of appeals under the fourth amendment. But these standards

are surely "instructive," Wolfish, supra, of the degree to which

experienced police professionals have concluded that the authority

to shoot nondangerous fleeing suspects is not necessary to

effective law enforcement.

-20-

standard recommended by the IACP report is that: "An officer may

use deadly force to effect the capture or prevent the escape of a

suspect whose freedom is reasonably believed to represent an

imminent threat of grave bodily harm or death to the officer or

other person(s)." Matulia, supra, at 164 (emphasis in original).

Similarly, the Standards for Law Enforcement Agencies (August

1983) of the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement

20/Agencies provides "that an officer may use deadly force

only when the officer reasonably believes that the action is in

defense of human life, including the officer's own life, or in

defense of any person in immediate danger of serious physical

injury." Standard 1.3.2.

In sum, the clear position of the organized, professional

police community — as reflected by its standards, written

policies, and pratices — refutes the state's argument that

effective law enforcement will be hampered without the authority

to shoot nondangerous fleeing felony suspects.

III. THE JUDGMENT BELOW SHOULD BE AFFIRMED BECAUSE THE

MEMPHIS POLICY AND CUSTOM IS ONE OF LIBERAL USE OF

DEADLY FORCE THAT RESULTS IN THE EXCESSIVE AND UN

NECESSARY USE OF SUCH FORCE TO STOP NONDANGEROUS,

FLEEING FELONY SUSPECTS______ _____________________

Although the court of appeals did not reach the question

of the constitutionality of Memphis's policy ana customs regarding

the use of deadly force, it was familiar with the exceptional

record of Memphis police with regard to the shooting of fleeing

20/ These standards were "prepared by the four major law

enforcement executive membership associations, tne ... IACP,

National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives

(NOBLE); National Sherrifs' Association (NSa ); and the Police

Executive Branch Forum (PERF)." Iji. at iii.

-21-

suspects, particularly blacks. See Bayes v. Memphis Police Dept.,

571 F .2d 357 (6th Cir. 1978); Wiley v. Memphis Police Dept., 548

F .2d 1247 (6th Cir. 1977); Qualls v. Parish, 534 F .2d 690 (6th

Cir. 1976); Beech v. Melancon, 465 F.2d 425 (6th Cir. 1972); see

also Cunningham v. Ellington, 323 F. Supp. 1072 (W.D. Tenn.

1971) (three judge court); McKenna v. City of Memphis, 544 F.

Supp. 415 (W.D. Tenn. 1982) (shooting of brother officer in

21/attempt to stop fleeing misdemeanant). The excessiveness of

the Memphis policies and customs in violation of the fourth amendment

and the due process clause is an alternative ground for affirming

the judgment below. Rule 10.5, Rules of the Supreme Court of

the United States.

Even assuming the appropriateness of using one's revolver

to arrest a suspect, Memphis's policies, practices, and customs

go oeyond what is necessary. Because of the district court's

decision not to allow further hearings on remand, the record

on the question of the Memphis policy or custom is a hybrid.

It consists of the evidence adduced at the original trial and

_22/the offer of proof tendered on remand. But despite the

nature of the record and the lack of findings below, it is

clear that Memphis's use of deadly force to stop nondangerous

suspects is uniquely excessive in its execution.

21/ As indicated above, supra n.17 and text accompanying

nn.17-18, the percentage of firearm discharges against non

dangerous, fleeing suspects as compared to all firearm dis

charges by Memphis police is amongst the highest in the nation.

It is also noteworthy that Memphis accounts for about 30% of all

the reported federal cases on this issue in the last 10 years.

22/ Organized in fifteen parts, the offer of proof includes

affidavits of expert witnesses who would have been called to

testify, App. 765-97; excerpts from prior federal cases against

the Memphis Police Department that illuminate Memphis's actual

policies and customs regarding the use of deadly force, App.

798-1019, 1409-57, 1460-69, 1477-1601, ano 1614-1891; excerpts

from the report of the Tennessee Advisory Committee to the

-22-

At trial, plaintiff called CaptairyColetta, who was

responsible for recruit training and the ammunition policies

of the Memphis Police Department. He testified that the

Memphis police have always used a .38 caliber Smith and Wesson.

In the years immediately preceding the Garner shooting, Memphis

twice upgraded its ammunition to bullets with greater velocity,

accuracy, and predicted wounding power. App. 413-16, 425-

27, and 447. The bullet that was finally selected was the

125 grain, semi-jacketed, hollow-point Remington. Both

Coletta and the Shelby County medical examiner testified

that this bullet is a "dum-dum" bullet banned in international

use by the Hague Convention of 1899 because it is designed

to produce more grievous wounds. App. 487-88 and 572. This

is the bullet that killed young Garner.

Coletta also testified that Memphis recruits are

taught to aim at the torso, or "center mass," where vital

organs are more likely to be hit. App. 357-58. See also

23/App. 1597 and 1807-08. Together with the use of "dum-dum"

bullets, this creates a far greater risk that the resulting

wound will be fatal. Moreover, the interplay of these two

22/ continued

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, which was based on hearings

on civil rights abuses by the Memphis Police Department,

App. 1050-58; the deadly force policies of 44 major municipali

ties, App. 1108-1368; the training materials for the New York

Police Department, App. 1369-1408; and an excerpt from an

LEAA publication on deadly force that details police training

procedures used in other cities but not in Memphis. App.

1602-13.

23/ Captain Coletta testified that the reason for teaching

recruits to aim for the torso was not related to police safety;

it did not create a better chance of neutralizing a dangerous

suspect. App. 353-57. Rather, it is taught solely because the

torso presents a greater target and thus reduces the chances of

missing. App. 357-58.

-23-

factors creates an indelible impression upon the Memphis police

officer that the policy of the department is one encourag-

24/ing use of one's revolver. indeed, in a prior case, the district

court found that Memphis police officers "were trained whenever

they use their firearms to 'shoot to kill.'" Wiley v. Memphis

Police Dept., 548 F .2d at 1250.

Other policies, practices, and customs of the Memphis Police

Department also encourage the quick resort to the use of deadly

force without a proper effort to exhaust other alternatives.

Captain Coletta testified that the department used the film

"Shoot - Don't Shoot," which presents only armed fleeing felons

in its situational illustrations of the fleeing felon rule, App.

25/329-32; that there was no training in alternatives that

should be exhausted before resorting to deadly force to stop

unarmed fleeing felony suspects, App. 340 ; that i_he department s

24/ Chief William R. Bracey would have testified that "a

definite message was transmitted when [Memphis] reiterated

its policy of shooting 'to stop' and at the same time intro

duced the use of dum-dum bullets. The message transmitted

to line officers would seem to suggest the department s support

of firearm use." App. 773.

At the time of his affidavit, William R. Bracey was Chief

of Patrol of the hew York Police Department with supervisory

authority over all 17,500 uniformed personnel of the New York

Police Department. He would also have testified: that guidelines

and committed enforcement of those guidelines by the police

hierarchy will lead to reductions in the use of unnecessary

deadly force; that New York has reduced firearms discharges by

50% by these means; that the result of this reduction has been

the increased safety of New York Police Department officers with

fewer assaults on officers and fewer deaths; that law enforcement

has been unhampered; that training, including training in alterna

tives to minimize the need for use of deadly force, and discipline

are the keys to reducing unnecessary deadly force; that shooting

unarmed fleeing felons is related to the officer's subjective

notions of punishment; and that the Memphis policies of shooting

fleeing property crime suspects, use of "dum-dum" bullets, and

training and discipline were all deficient. App. 765—78.

25/ Tne heavy reliance on the"Shoot/Don't Shoot" film encourages

"the use firearms because, as respondent-appellee's expert Chief

Bracey would have testified, it has a negative effect on an

inexperienced recruit, making him jumpy and more likely to

employ deadly force. App. 774.

-24-

firearms manual details firearms techniques, but not techniques

to avoid the need for the use of weapons, App. 344-45; ana that

tne use of deadly force to stop fleeing felony suspects is left

to the individual officer's discretion: recruits are simply told

that tney must live with themselves if they kill a person. App.

326 and 345. Accord App. 195-96, 901, 956, and 1796.

It is particularly significant that there is no training on

when to use deadly force. This lack of guidance operates m tandem

with a policy — evidenced by pronouncements of the mayor, App.

1632 and 1825-28, and the miserable failure of the Memphis Police

26/

Department disciplinary procedures, App. 547 and 1858,

not to review and control firearm discharges. As a result,

Memphis officers get the clear message that they can deadly force

without guidelines and with impunity. The proximate result is

the excessive use of deadly force in situations when it is not

necessary in order to apprehend the subject.

This case provides an adequate illustration: The police

experts testified that Hymon should have attempted to apprehend

young Garner, who was only 30 to 40 feet away, rather than

27/solely on his gun. A* 8. Other illustrations

abound. In McKenna, the officer who hit his fellow officer was

shooting at a fleeing misdemeanant; he was a known shooter but

had never been disciplined or retrained. 544 F. Supp. at 417.

26/ No Memphis police officer had ever been disciplined for the

Hie of his gun. App. 547 and 1858. The civili? " ^ lal^ r^ ° Ce" dures are designed to deter complaints. App. 1050-58. First,

there is a rule that all complainants must take a polygraph

while no officer is ever required to. Second, the procedures

require that the officer against whom a charge is made must

immeaiately be notified of the complainant's name ana aadress.

App. 1050-58.

27/ The only witness to testify that the officer was justified

In using his gun was Captain Coletta, who had both trained Hymon

and sat on the review board that condoned the snooting. App. 506

507-09. Even so, his opinion was based on an assumption not sup

ported by the facts: that Hymon was "physically barrea from the

area by a fence." App. 532.

-25-

In another instance, Memphis officers shot and killed a fleeing

olack teenager who had committed car theft, even though his

accomplice was already in custody and could have provided

identification. The officer who shot never considered any

alternatives, not even giving chase. App. 844-45.

There can be little doubt that myriad Memphis polices and

customs are implicated as the cause of the shooting death of

respondent-appellee's son. "In this case, City officials did set

the policies involved ... training and supervising the police

force...," Leite v. City of Providence, 463 F. Supp. 585, 589

(D. R.I. 1978), exposing the city to liability under Monell.

Young Garner was shot pursuant to that liberal use of deadly

force policy and custom "which allows an officer to kill a flee

ing felon rather than run the risk of allowing him to escape ap

prehension." Garner, 600 F. 2d at 54; A. 16. Here, the officer

did no more than follow that policy, as he "was taught." I_d. at

53; A. 16. The judgment below should be affirmed on this basis

alone.

IV. MEMPHIS'S POLICY AUTHORIZING THE DISCRETIONARY

SHOOTING OF NONDANGEROUS, FLEEING PROPERTY CRIME

SUSPECTS VIOLATES THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE

BECAUSE IT IS RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY_____________

The Memphis policy runs afoul of the Constitution in

another fundamental way not discussed by the court of appeals: It

is a policy that discriminates on the basis of race. The materials

contained in the offer of proof betray a policy "in actual opera

tion, and the facts shown establish an administration ... with an

evil eye and an unequal hand" in violation of the fourteenth amendment.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. at 373-74; see also Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238, 389 n.12 (1972) (Burger, C. J., dissenting).

The offer of proof contains the raw data concerning all

arrests in Memphis between 1963 and 1974, App. 1409-57 and

-26-

1767-68; data on all shootings of fleeing property crime suspects

between 1969 and 1974, App. 1460-69; data on all those killed by

Memphis police officers between 1969 and 1976, App. 1764-67 and

28/1071; prior analysis of this data by a statistician, App.

1769-77, and his testimony at an earlier trial regarding this anal

ysis, App. 1559-62 and 1589-92; historical data regarding race

discrimination by the Memphis Police Department from 1874 through

the mid-seventies, including the deposition testimony of the mayor

and police director supporting this conclusion, App. 908-910,

928-32, 972-74, 1539-40, 1571-75, 1646-56, 1677-78, 1690, and

1828-29; and the affidavit of plaintiff's expert, Dr. James J.

29/Fyfe, which analyzed in detail the arrest and shooting data

contained in the offer of proof. App. 787-97.

On the use of deadly force, the data reveal thac there are

significant disparities based on the race of the shooting victim/

suspect and that virtually all of this disparity occurs as the

result of the Memphis policy that allows officers to exercise

their discretion to shoot fleeing property crime suspects. Be

tween 1969 and 1976, blacks constituted 70.6% of those arrested

tor property crimes in Memphis but 88.4% of the property crime

suspects shot at by the Memphis police. In contrast, the percent

age of black violent crime suspects shot at by Memphis police

was closely proportionate to their percentage in the violent crime

arrest population: 85.4% ana 83.1%, respectively. App. 1773.

28/ Ail of the foregoing data was collected and provided by

the Memphis Police Department as defendant in Wiley v. Memphis

Police Dept., Civ. Action No. C-73-8 (W.D. Tenn. June 30,

1975), aft'd, 548 F .2d 1247 (6th Cir. 1977).

29/ Dr. Fyfe is a former New York Police Department lieutenant

and training officer. He designed a firearms trainings program

tor the New YorK Police Department in which over 20,000 officers

have participated. His doctoral thesis concerned the use of

deadly force by New York Police Department officers. He is an

associate professor at The American University in Washington,

D.C., and has served as a consultant on the deadly force issue

for the United States Department of Justice ana the Civil Rights

Commission. App. 788-89. He also teaches courses at the F.B.I.

National Academy at Quantico, Va.

-27-

con-Or. Fyfe reviewed this cata and concluded that

trolling for differential racial representation in the arrest

population, black property crime suspects were more than twice as

liKely to be shot at than whites (4.33 per 1000 black property

crime arrests; 1.81 per 1000 property crime arrests), four times

more likely to be wounded (.586 per 1000 blacks; .1113 per 1000

whites), and 40% more likely to be killed (.63 per 1000 blacks,

.45 per 1000 whites). App. 792.

Comparison of shootings by Memphis Police officers while

controlling for race of the shooting victim and the nature of the

incident provided similarly striking data. Dr. ryfe s analysis

of the shooting incidents between 1969 and 1976 described by the

Memphis Police Department to the Civil Rights Commission showed a

dramatic disparity between the situations in which whites were

killed and those in whicn blacks were killed. Of the blacks shot,

50% were unarmed and nonassaultive, 23.1% assaultive but not

armed with a gun, 26.9% assaultive and armed with a gun. Of the

whites shot, only one was non—assaultive (12.5%), five (62.5%)

were armed with a gun, and the remaining two (25%) were assaultive

Wbut not armed with a gun.

Based on this data, Dr. Fyfe concluded that, during the

period in question, Memphis police were far more likely to shoot

blacks than whites in non—threatening circumstances and that the

great disparity in blacks shot by Memphis police officers is

largely accounted for by the policy allowing the discretionary

shooting of non—dangerous fleeing felony suspects. Between 1969

and 1976, Memphis police killed 2.6 unarmed, non-assaultive

blacks for each armed, assaultive white. App. 793-94.

30/ Dr. Fyfe noted that: "These are certainly dramatic differ

ences, but no measure of their significance is possible ...

because the only statistically significant category of whites

killed is those armed with guns." App. 794.

-28-

Plaintiff proffered this evidence having previously-

requested both additional discovery and a hearing on these

factual questions. The district court, in its post-reconsidera

tion order, A. 31, rejected Dr. Fyfe's conclusions on the basis

of several unsupportable considerations. It noted Dr. Fyfe's

. , 31/"bias," A. 34, without ever having seen him testify.— it

attacked Dr. Fyfe's conclusions because, it claimed, he failed to

"specify the actual number of blacks arrested and/or convicted

for alleged 'property crimes' as compared to whites during this

period." A. 32. But, as discussed above, Dr. Fyfe's analysis

specifically "controls for differential involvement among the

races in property crime...," App. 7y2; indeed, the data on which

Dr. Fyfe relied was included in the offer of proof and provided

trie actual number of both white and black property crime arrests

together with the raw data of ail arrests. App. 1409-57 and

1767-68. The district court questioned the delineation of

"'property crime' in the Fyfe definition." A. 32. But the

delineation between property crimes and violent crimes that Dr.

Fyfe employed was that made by the Memphis Police Department and

included witn the arrest statistics. App. 1559 and 1767-68.

In numerous similar ways, the district court misapprehended 32/

31/ The district court's "bias" finding was based on Dr.

Fyfe's disagreement with the Memphis policy allowing the use

of deadly force against nondangerous suspects. This "bias,"

however, is the official policy of the F.B.l. and numerous

metropolitan police departments as disparate as New York,

Atlanta, and Charlotte, North Carolina. See App. 1113, 120U,

1293, and 1869.

32/ For example, in questioning Dr. Fyfe's observation that

the incidence of use of deadly force in property crime arrests

in Memphis far exceeded that in New York, the district court

noted that: "Professor Fyfe admitted his comparison was not

'precise' in respect to 'property crimes' comparison." A. 32

n. 1. But Dr. Fyfe accounted for this imprecision in a way

that favored Memphis. His "admission" was that:

-29-

Moreover, the district court failed to consider that the

historical background of the Memphis Police Department corrobo

rates the inference of discrimination that arises from the

statistics. Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 265-67 (1977). The department's history is one of

3 3/entrenched racism m employment, promotion, and law enforcement.—

The department was repeatedly the agent of enforcement of the

segregation laws in the 60's, App. 1539-40, engaging in racial

abuse and brutality during the sanitation strike in 1968. App.

1571-75. A 1970 NAACP Ad Hoc Committee Report concluded that:

"the most common form of address by a Memphis policeman to a

black person appears to be 'nigger.'" App. 1671. And, it was

acknowledged by Mayor Chandler that, as late as 1972:

The black community, speaking generally and in a broad sense,

perceives the police department as having consistently

brutalized them, almost their enemy instead of their

friend.... [Tjalking about in 1972, what you say is

absolutely true and I would say almost across the board.

32/ continued

More than half (50.7 percent) of the police shootings

in Memphis during 1969-1974 involved shooting at property

crime suspects. The comparable percentage in 1971-1976

in hew York was no more than 11.8 percent. This comparison

is not precise because the New York City figure includes

all shootings to "prevent or terminate crimes." Thus,

it includes shootings precipitated by both property crimes

and crimes of violence. My estimate of tiie percentage of

New York City police shootings which involved property

crime suspects only is four percent.

App. 791.

Similarly, in arguing that Dr. Fyfe failed to control

for disparate racial involvement in the underlying felonies,

the district court alleged that Dr. Fyfe "concedes elsewhere

that there is also 'differential racial involvement in police

shootings.'" A. 32. What Dr. Fyfe said, however, is that:

"In New York City, differential racial involvement in police

shootings also exists, but [unlike Memphis] it is almost

totally accounted for by differential racial involvement in

the types of activities likely to precipitate shootings."

App. 792.

33/ As long ago as 1874, a "Resolution asking Police Board to