Greenberg Statement on Newark Medical School

Press Release

December 29, 1967

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 5. Greenberg Statement on Newark Medical School, 1967. b4e00264-b892-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/168cdd01-4356-4169-bdea-7de46d3e73eb/greenberg-statement-on-newark-medical-school. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

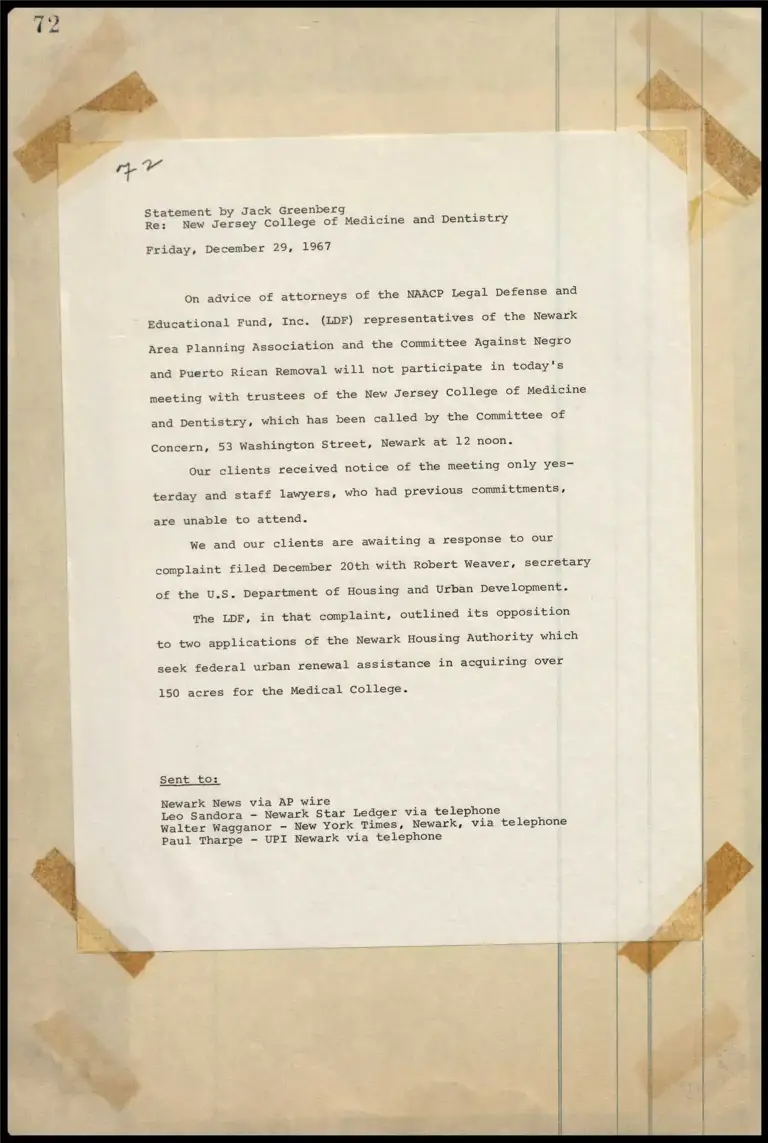

Statement by Jack Greenberg

Re: New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry

Friday, December 29, 1967

On advice of attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) representatives of the Newark

Area Planning Association and the Committee Against Negro

and Puerto Rican Removal will not participate in today's

meeting with trustees of the New Jersey College of Medicine

and Dentistry, which has been called by the Committee of

Concern, 53 Washington Street, Newark at 12 noon.

Our clients received notice of the meeting only yes-

terday and staff lawyers, who had previous committments,

are unable to attend.

We and our clients are awaiting a response to our

complaint filed December 20th with Robert Weaver, secretary

of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The LDF, in that complaint, outlined its opposition

to two applications of the Newark Housing Authority which

seek federal urban renewal assistance in acquiring over

150 acres for the Medical College.

Sent to:

Newark News via AP wire

Leo Sandora - Newark Star Ledger via telephone

Walter Wagganor - New York Times, Newark, via telephone

Paul Tharpe - UPI Newark via telephone