Taylor v. ARMCO Steel Corporation Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Taylor v. ARMCO Steel Corporation Brief of Appellants, 1969. 7b44b7c1-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16939d32-2f0f-4133-9318-8bd89f94114d/taylor-v-armco-steel-corporation-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

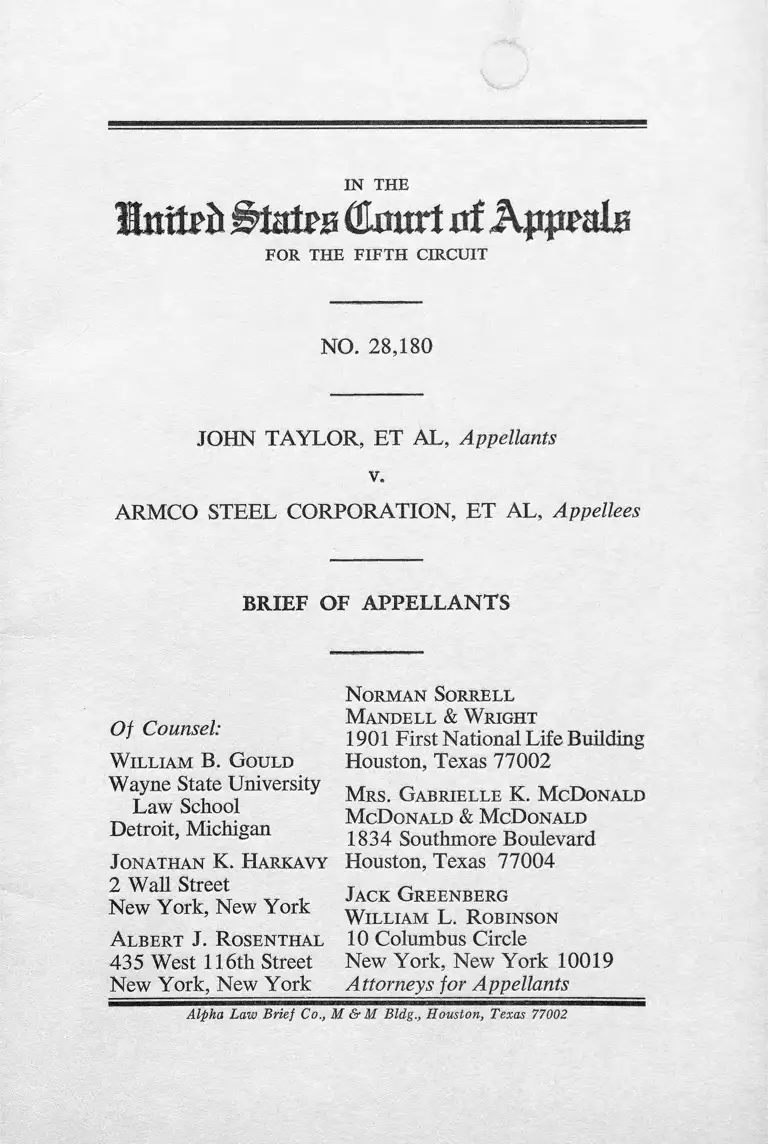

Hitttri) Stotra (Enurt rtf Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

NO. 28,180

JOHN TAYLO R, ET AL, Appellants

v.

ARM CO STEEL CORPORATION, ET AL, Appellees

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Of Counsel:

W il l ia m B . G o u l d

Wayne State University

Law School

Detroit, Michigan

Jo n a t h a n K. H a r k a v y

2 Wall Street

New York, New York

A l b e r t J. R o s e n t h a l

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York

N o r m a n So r r e l l

M a n d e l l & W r ig h t

1901 First National Life Building

Houston, Texas 77002

M r s . G a b r ie l l e K. M c D o n a l d

M c D o n a l d & M c D o n a l d

1834 Southmore Boulevard

Houston, Texas 77004

Ja c k G r e e n b e r g

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Alpha Law Brief Co., M & M Bldg., Houston, Texas 77002

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. POINTS OF ERROR 1-2

1............................................................................. 1

2..................................................................................... 1

3............................................................................. 2

II. STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE PRE

SENTED FOR REVIEW 2

III. STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2-5

IV. STATEMENT OF FACTS 5-11

V. STATUTES INVOLVED 12-14

VI. ARGUM ENT AND AUTHORITIES 14-35

POINT 1, RESTATED 14

POINT 2, RESTATED 28

POINT 3, RESTATED 33

CONCLUSION 35

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

c a se s Page

Argo v. C.I.R. (5th Cir. 1945), 150 F.2d 67 15

Astron Industrial Associates, Inc. v. Chrysler

Motors Corp. (5th Cir. 1968), 405 F.2d 958,

960 (res ajudicata) ........................................... 32

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Engine-

men v. Chicago R.I. & P.R. Co. (1968 ), 393

U.S. 129, 131 ....................................................... 34,35

Compania Mexicana v. Jernigan (5th Cir. 1969),

410 F.2d 718, 726 (Collateral estoppel) . . 32

II

c a s e s Page

Denver Building & Construction Trade Council

v. N.L.R.B. (D.C. Cir. 1950), 186 F.2d 326,

332, reversed on other grounds, 341 U.S. 675

(1951) 34

Gaston County v. United States (1969 ), 395

U.S. 285 25

Kalb v. Feuerstein (1940), 308 U.S. 433, 444 34

Local 12, United Rubber Workers v. NLRB,

368 F.2d 12, 24 (1966 ), Cert. Den’d., 389

U.S. 837 (1967) ................................................ 17

Local 53, International Association of Heat and

Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir. 1969) .................................................. 16,20

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperwork-

ers v. United States, _____ F.2d____ , 71 LRRM

3070, 60 L.C. Para. 9289 (5th Cir. July 28,

1969) ................................ 1 6 ,2 2 ,2 3 ,2 4 ,2 6 ,2 7 ,2 8 ,3 3

Louisiana v. United States (1965), 380 U.S. 145 25

Norman v. Missouri Pac. Railroad Co., 414 F.2d

73, p. 84 ..............................................................18, 19, 20

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968) .......................................21, 22, 27, 28

United Shoe Machinery Corp. v. U. S., 258 U.S.

451, 459 ................................................................ 32

United States v. Hayes International C orp .,____

F.2d------- , 2 FEP Cases 67, 60 L.C., Para

graph 9303 (5th Cir. August 19, 1969) . . 17

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Interna

tional A ssn .,-------F.2d____ , 2 FEB Cases 127,

61 L.C. Paragraph 9319 (8th Cir. 9 /1 6 /6 9 ) 16

Teas v. Twentieth Century Fox Films, Inc. (5th

Cir. 1969), 413 F.2d 1263, 1267 32,33

Whitfield v. United Steelworkers of America,

Local 2708 (5th Cir. 1959), 263 F.2d 546,

Cert. Den’d., 360 U.S. 902 (1959)

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 22,

2 4 ,2 6 ,2 7 ,2 8 ,2 9 ,3 0 ,3 1 ,3 3 ,3 5

Ill

Page

UNITED STATES STATUTES

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C., Sec. 2000e to 2000e(15) ..................

The National Labor Relations Act (Labor Man

agement Relations Act, 1947), 29 U.S.C., Sec.

151 to 166 1 ,2 ,6 ,1 4 ,1 5 ,1 6 ,1 7 ,1 8 ,2 8 ,3 4

The Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. Sec. 154, 45

U.S.C., Sec. 153 .................................................. 15, 18

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 25

TEXTS

Cooper & Sobel, Seniority and Testing Under

Employment Laws, A General Approach to

Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion,

82 Harvard L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ................ 21

Developments in the Law: Res Ajudicata, 65

Harv. L. Rev. 818 (1952) .............................. 32

Gould, The Emerging Law Against Racial Dis

crimination in Employment, 64 Northwestern

University L. Rev. 359 (1969) .................... 16

Gould, Employment Security, Seniority and Race,

The Role of Title VII of the Civil Rights A ct

of 1964, 13 Howard L.J. 1 (1967) ................ 21

Gould, Seniority and the Black Worker, Reflec

tions on Quarles and its Implications, 47 Tex

as L. R e v ie w ......................................................... 21

IB Moore’s Federal Practice, Sec. 0.415 nn8, 21-

25 (1965) .................................................... 14, 32, 34, 35

Report of the National Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders, 251-264 (New York Times

edit. 1968) ........................................................... 16

Title VII, Seniority Discrimination and the In

cumbent Negro, 80 Harvard L. Rev. 1260

(1967) 21

Unitrii States (Lrnrt of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

NO. 28,180

JOHN TAYLO R, ET AL, Appellants

v.

ARM CO STEEL CORPORATION, ET AL, Appellees

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

I.

POINTS OF ERROR

1. The district court erred in failing to hold that

Title VII. of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the

National Labor Relations Act impose different stat

utory obligations. Conduct held valid under the fair

representation doctrine is not necessarily lawful and

permissible under Title VII.

2. The district court erred in failing to find that

appellants raise fact issues and plead circumstances

which arose after the decision of W hitfield and,

therefore, even if Title VII. imposed no new obli-

2

gations upon the employer and union which differ

from the obligations imposed under the National

Labor Relations Act, changes in the employment re

lationships of the parties since the W hitfield decision

prevent W hitfield from controlling the plaintiffs’ and

intervenors’ proceedings.

3. The district court erred in failing to exercise

its discretion to limit the applicability of res judi

cata and collateral estoppel where there are allega

tions that there has been a significant change in

circumstances or where the preclusionary principle

would serve no useful end.

II.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE PRESENTED

FOR REVIEW

Whether the district court erred in dismissing plaintiffs’

and intervenors’ complaint of racial discrimination by rul

ing that Whitfield v. United Steelworkers of America,

Local 2708, 263 F.2d 546, (5th Cir. 1959), cert, den’d,

360 U.S. 902 (1959), forecloses consideration of plain

tiffs’ and intervenors’ claims founded upon Title VII. of

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

III.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Nature of the Case:

This appeal is from a final judgment of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Texas

(Seals, J., presiding). The district court dismissed plain

tiffs’ and intervenors’ claim for the vindication of rights

3

guaranteed to them by Title VII. of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C., Secs. 2000e-l et seq. (Title VII. here

in). The principal legal question presented by this appeal

is whether a 1959 fair representation decision ( Whitfield,

supra) forecloses consideration of plaintiffs’ and inter-

venors’ present claims based on the 1964 Civil Rights

Statute.

On or about August 11, 1966, plaintiffs filed charges

under oath with the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission ( “EEOC” or “Commission” herein) alleging that

their rights under Title VII. were violated because of

seniority and promotion arrangements negotiated by the

defendant union and the defendant employer. The EEOC

did not render a decision on this matter during the nine

teen months while the charges were pending before it.

However, in letters sent to the plaintiffs on January 17

and February 5, 1968, the Commission gave plaintiffs

notice that they might institute a civil action for redress

of unlawful job discrimination. In the matter of Alfred

James’ charge, EEOC did reach a finding of reasonable

cause prior to his intervention in this proceeding.

Since neither the State of Texas nor the City of Houston

has a fair employment practice statute or ordinance, as

contemplated by Section 706 of Title VII. of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, plaintiffs filed a petition for relief

in the United States District Court for the Southern Dis

trict of Texas (Houston Division) on February 15, 1968

(R. p. 1). Shortly thereafter, plaintiffs amended their

complaint so as to make their suit a class action on behalf

“ of other persons similarly situated, who are employed

by Armco Steel Corporation at its mills, plants and/or other

facilities (in Houston, Texas), and who are members of

the United Steelworkers of America, Local 2708, AFL-

4

CIO. . . (R. p. 5 ). As defendants in the amended

complaint, plaintiffs named Armco Steel Corporation

( “Armco” or “employer” herein), United Steel Workers

of America, AFL-CIO, and Local 2708 of United Steel

workers of America, AFL-CIO ( “union” herein) (R.

p. 4 ).

The defendants answered the amended complaint and

moved to dismiss the complaint on several grounds (R.

pgs. 16, 27 ). Thereafter Alfred James moved for and was

granted leave to intervene as a plaintiff, and he subse

quently filed an intervenors’ complaint (R. pgs. 39, 42).

Only Armco answered James’ complaint. The parties

briefed the issues and the EEOC filed an amicus curiae

brief in support of plaintiffs’ position. Motions for leave

to intervene were then filed by Leroy Matthew and

Willie Glass.

On June 9, 1969, the district court issued a memoran

dum and order denying defendants’ motions to dismiss on

jurisdictional grounds but dismissing so much of plaintiffs’

and intervenors’ complaint as dealt with the discriminatory

effect of defendants’ lines-of-progression seniority system

(R. p. 104). The court held that the question of whether a

Supplemental Agreement of 1966 was negotiated with “ an

effort to discriminate” and “ was born out of racial discrimi

nation” could be litigated provided that the issue would not

include any reference to the issues previously litigated in

the above-noted Whitfield case, if plaintiffs would amend

their complaint accordingly. (R. p. 117). Plaintiffs de

clined to amend their complaint. On July 14, 1969, the

district court rendered a final judgment granting defend

ants’ motions to dismiss upon the basis of defendants’ res

judicata defense. In the final judgment the court also

granted Matthew’s and Glass’ motions for leave to inter

5

vene, and judgment against all intervenors was rendered

on the same basis as against the original plaintiffs and

their class (R. p. 121). Notice of appeal from this final

judgment was filed on July 18, 1969 (R. p. 123).

IV.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A chronological review of employment practices at

Arm co’s Houston plant will help the analysis of the issues

of whether Whitfield, supra, precludes plaintiffs’ claims.

From the commencement of operations at the Houston

plant in 1942 until 1956, master collective bargaining

contracts covering the nation’s entire steel industry pro

vided that each local plant would establish lines of pro

gression within each department. Pursuant to the collective

bargaining contracts in effect since 1942, two lines of

progression (or job lines) have been maintained in

Armco’s Structural Mill Department, where plaintiffs and

the class of Armco employees they represent are employed.

In the Open Hearth Department, where James, Matthew

and Glass are employed, there are also two job lines.

The Number 1 line in the Structural Mill Department

encompassed jobs classified by the employer and the

union as “ skilled” . Prior to 1956, only white employees

staffed these jobs, which ranged in salary position from

Class 5 to Class 17. Line 2 in such department encom

passed job classes 2 through 9, and prior to 1956 only

Negroes staffed these “ unskilled positions” . The job classes

or salary positions are ranked from lowest number to

highest number in order of increased hourly wages.

Prior to 1956, Armco retained unbridled discretion to

screen all employees for Line 1 positions, and used this

6

power to exclude Negroes completely from Line 1. Be

cause of complaints from Negro employees concerning

their exclusion from skilled jobs, the defendants, com

mencing in 1954, began to negotiate among themselves

in order to achieve more equitable employment practices

at the Houston facilities. The negotiations culminated in

the “ 1956 agreement,” in which defendants agreed that

Negro employees could bid on Line 1 jobs if they passed

a qualification test. As part of the agreement, those em

ployees moving from Line 2 to Line 1 would begin em

ployment in the latter line in the lowest job class in that

line, and with absolutely no line seniority.

Dissatisfaction with the 1956 agreement prompted some

Negro employees to file a suit against Armco and the

union, alleging a breach of the duty o f fair representation

under the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. Sec.

159. The suit culminated in this Court’s decision in

Whitfield v. United Steelworkers of America, supra, in

which this Court found that “ . . . there [was] no evi

dence of unfairness or discrimination on the ground of

race” in the 1956 agreement. The arguments by the

Whitfield plaintiffs that interline mobility was unlawfully

impaired by the qualification test and the provisions as

to loss of seniority contained in the 1956 agreement were

rejected in an opinion by Judge Wisdom, which details

more fully the pre-1956 circumstances in the Structural

Mill Department. See 263 F.2d at 547-548.

For nearly a decade after Whitfield the parties labored

under collective bargaining agreements akin to the 1956

agreement. Gradually, interline mobility increased, and

it is fair to note that, until the events of 1965 and 1966,

some of the discriminatory effects of the pre-1956 seniority

system were being very gradually eroded by a trickle of

7

qualified Negro workers moving from Line 2 to Line 1

positions, and then moving up within Line 1. However,

it should be noted that these few Negroes who transferred

from Line 2 to Line 1 positions received a new line

seniority date from the time of their transfer; no credit

was given these employees for their accrued seniority in

Line 2.

Meanwhile, although the hourly rate of pay theoretically

increased as a worker progressed to a higher job class,

certain jobs received incentive pay. Incentive pay made

it possible, in some instances, for a worker in a lower job

class to earn more than another employee in a higher

job class. As a result, many employees whose seniority

would have entitled them to fill vacancies in jobs with

higher classifications, elected to remain in lower job

classifications because they paid better overall.

Beginning in 1965, however, defendants once again

began to draw out the worst in seniority systems by a

series of maneuvers which shifted the focus of racial

discrimination within the system from interline mobility

to intraline mobility. Defendants instituted two major

changes in their employment practices, the combined

effects of which grievously violated rights guaranteed to

plaintiffs by Title VII.

First, pursuant to an agreement among the defendants

dated November 1, 1965, incentive pay became applicable

to all jobs in the Structural Mill Department. While the

pre-1965 selective incentive pay scheme had artifically

limited the attractiveness of upward movement within

each line of progression, when incentive pay became a

part of all job classes the distinctions between job classes

once again became decisive; to better one’s self economi

8

cally, one had to continue movement up the lines of pro

gression.

The second important change in employment practices

occurred on August 9, 1966, when, pursuant to an agree

ment among the defendants, all jobs from class 5 to class

12 (Finishing Shear Operator) in Line 1 were opened

to bids based solely on line seniority. By this 1966 agree

ment defendants upset the orderly progression within a

line based on bids taken first from the class immediately

below the job opened up. The 1966 agreement substituted

for this orderly procedure an arbitrary bid system. Such

new system is not grounded on relevant job qualifications,

and its effect is to discriminate against qualified employees

who lack only line seniority (by virtue of past discrimina

tion because of their color).

It should be noted at this point that the Whitfield

decision, upholding the provision of the 1956 agreement

that Negroes transferring from Line 2 into Line 1 had

to do so at the bottom rung and without seniority, was

based on the premise that “ [t]he jobs start with the

easiest in terms of skill, experience, and potential ability

and progress step by step to the top job in the line. The

knowledge acquired in a preceding job is necessary for

the efficient handling of the next job in the progression.”

263 F.2d at 548. But in 1966 the defendants made

abundantly clear that they no longer regarded the knowl

edge acquired in a preceding job as necessary to the

efficient handling of the next job in the progression. And

by making line seniority the decisive factor in advance

ment, they gave fresh life to the pre-1956 discrimination

against Negro employees just when there were signs that

some of the consequences of that discrimination were

beginning to disappear.

9

By way of illustration, prior to the August 9, 1966,

Supplemental Agreement, the progression in Line 1 would

operate as follows:

“A job in Class 10 becomes open, no employee in

Class 9 wishes the job. The man with the least line

seniority in Class 8 wishes to obtain the Class 10

job and does obtain it. This man has less seniority

than anyone in Class 9. Later, a job becomes vacant

in Class 11. The man who, with less line seniority,

has recently risen from Class 8 to Class 10, would

have preference over anyone in Class 9 for the

opening in Class 11.” (R . pgs. 10, 11).

Under the Supplemental Agreement, however, the em

ployee with the greatest Line 1 seniority, regardless of

what class work he was performing, would have the first

opportunity to bid for the top jobs. And since Negroes

had been barred from Line 1 before 1956, this past

discrimination would rise up still another time to deprive

them of jobs in the higher classes, in favor of white

employees with longer line seniority but who had never

done the work in the jobs immediately below the one for

which they were bidding. Thus, the defendants have

completely cut away the ground on which Whitfield had

sustained the 1956 agreement, namely that business

necessity required step-by-step progress from each pre

ceding job to the one immediately above it.

Moreover, even if at the time Whitfield was decided,

the separate lines of progression might have been properly

characterized, respectively, as a “ distinct operation” in

the plant each “ composed of a series of interrelated jobs”

for which knowledge on one job is a necessary prerequisite

to effective handling of the next job in the progression,

many of the jobs included in each line are now inter

10

dependent and inter-related to a point that Line 2 em

ployees would become and, in fact, became fully compe

tent to handle Line 1 jobs given the opportunity (R. p.

8-9). For instance, the “tilt table operator” (Class 14

in Line 1) cannot put the steel through the mill until the

“wrencher” (Class 4 in Line 2) turns the bar in a posi

tion to enter the roll pass. The “ finishing shear operator”

(Class 12 in Line 1) is dependent on the “ shear helper”

(Class 4 in Line 2) to position the bar on the shear

blade and trip the shear before the bar is cut. The “crane

man” (Class 8 in Line 1) is dependent upon the “hooker”

(Class 3 in Line 2) (R. p. 8-9). These allegations of

plaintiffs’ complaint must be taken as true for purposes

of this appeal; plaintiffs are entitled to their day in court

to prove their accuracy.

The effect of the 1966 Supplemental Agreement was

to wipe out whatever advantage Negro workers with less

Line 1 seniority had as the result of the failure to move

up on the part of white incumbents who were benefiting

from the incentive pay scheme, but who had more line

seniority. For instance, Plaintiff Luther Reden had the

highest Line 1 job classification held by any Negro in

the Structural Mill Department. The effect of the 1966

Agreement was to discriminatorily deprive him of his job

by allowing white men with greater fine seniority to have

preference to it. The agreement was structured to appear

objective by affecting all of the jobs from finishing shear

operator down, but it was obviously aimed at Reden’s

job since the Agreement did not apply to any other Class

12 jobs or any other higher job classes (R. p. 11-12).

Mr. Reden had eighteen years of plant seniority, fifteen

years of departmental seniority and nine years of Line 1

11

seniority. He is discriminated against because he is denied

the job opportunity he would have had, but for the segre

gated lines of progression and the 1966 Agreement.

Although the changes adopted in 1965 and in 1966

thus raise serious problems when considered separately,

the full consequence can be measured only by consider

ing them together. The advent of incentive pay for all

positions has made intraline mobility a necessity for eco

nomic advancement, for all employees. At the same time,

Negro employees are now arbitrarily and capriciously shut

off from intraline mobility because of the open bid sys

tem based on wholly irrelevant line seniority.

The combined discriminatory effect of the 1965 and

1966 agreements, together with the passage of national

legislation providing the means for attacking such dis

crimination, have prompted these plaintiffs and intervenors

to seek vindication of their right to equal opportunity in

our economic system.

Intervenors James, Matthew and Glass, are switchmen

in the open hearth department railyard, not employees in

the Structural Mill (R. pgs. 42, 100, 102). But they

suffer from a progression scheme which forces them, with

no credit for Line 2 seniority which they may have ac

crued, to bid upon lower Line 1 jobs in their department

before having access to bid upon and be awarded the

Line 1 engineer’s job. Their duties as switchmen in the

railyard have made them much more familiar with and

adaptable to the job of the engineer, who operates the

yard switch engine, than to the Line 1 open hearth jobs

which they are required to stair-step up through as ob

stacles to the sought after engineer’s position (R. pgs. 42,

100, 102) .

12

STATUTES INVOLVED

The following portions of Title VII. of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 are involved in the disposition of this case:

Section 70 3 (a ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(a)

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1 ) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any indi

vidual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employ

ment, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2 ) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees

in any way which would deprive or tend to

deprive any individual of employment oppor

tunities or otherwise adversely affect his status

as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 7 0 3 (c ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(c)

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for a

labor organization—

(1 ) to exclude or to expel from its membership

or otherwise to discriminate against any indi

vidual because of his race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin;

(2 ) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership,

or to fail or refuse to refer for employment

any individual, in any way, which would de

prive or tend to deprive any individual of em

ployment opportunities, or would limit such

employment opportunities or otherwise ad

versely affect his status as an employee or as

an applicant for employment, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or na

tional origin; or

13

(3 ) to cause or attempt to cause an employer to

discriminate against an individual in violation

of this section.

Section 703 (d ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(d)

It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for any employer, labor organization, or joint

labor-management committee controlling ap

prenticeship or other training or retraining,

including on-the-job training programs to dis

criminate against any individual because of

his race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin in admission to, or employment in,

any program established to provide apprentice

ship or other training.

Section 703 (h ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h)

Notwithstanding any other provision of this

Title, it shall not be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer to apply different

standards of compensation, or different terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment pur

suant to a bona fide seniority or merit system,

or a system which measures earnings by quan

tity or quality or production or to employees

who work in different locations, provided that

such differences are not the result of an in

tention to discriminate because of race, color,

religion, sex, or national orgin; * * *

Section 70 6 (g ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g)

If the court finds that the respondent has in

tentionally engaged in or is intentionally

engaging in an unlawful employment practice

charged in the complaint, the court may en

join the respondent from engaging in such

unlawful employment practice, and order such

affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include reinstatement or hiring of

14

employees, with or without back pay (pay

able by the employer, employment agency,

or labor organization, as the case may be,

responsible for the unlawful employment prac

tice) * * *

V.

AR G U M E N T A N D AU TH O R ITIE S

1. TH E D IC T R IC T C O U R T ERRED IN FAIL

IN G T O H O LD T H A T TITLE VII. OF TH E CIVIL

RIG H TS A C T OF 1964 A N D TH E N A T IO N A L

LABOR RELATION S A C T IMPOSE DIFFERENT

S T A T U T O R Y OBLIGATION S. C O N D U C T HELD

V A LID U N D E R TH E FAIR REPRESEN TATIO N

D O C TR IN E IS N O T NECESSARILY LAW FU L

A N D PERMISSIBLE U N D ER TITLE VII.

The plaintiffs have brought this action under Title VII.

Its merits must be tested under that statute. Without

reaching the merits, the court below held that the decision

of this Court ten years ago in Whitfield, upholding certain

conduct of the defendants against charges of failure to

comply with the fair representation doctrine, was res

judicata against the plaintiffs and precluded them from

suing the defendants under Title VII.1 In effect, the court be

1. The most obvious argument for reversal that can be made is

that plaintiffs’ present claim could not have been litigated in the

Whitfield case because the statute upon which it is based was not

yet in existence. Indeed, it is a well established proposition that res

judicata cannot apply to claims premised upon statutes enacted

subsequent to the first decision. See IB Moore’s Federal Practice

Sec. 0.41S, nn. 8, 21-25 (1965). Nonetheless, plaintiffs realize that

one of the ultimate issues in this case is only begged by that propo

sition, and plaintiffs therefore do not place prime reliance on the

mere phenomenon of subsequent enactment of a statute. Plaintiffs do,

however, assert that enactment of a statute subsequent to and dealing

15

low had held that Title VII. was little more than an echo

of prior law, that the employment discrimination which

it forbade was no more than what had already been

forbidden, and that all of the soul-searching, the intense

debate, the agony of decision, the hopes for a chance at

a better job that were engendered by its enactment, were

all wasted because no changes of significance were really

being adopted after all.

The error in this holding can be demonstrated in dif

ferent ways. First of all, this court, as well as other courts

which have considered this question, have universally held

that the obligation to refrain from discrimination in em

ployment is dramatically different from, and greater than,

the duty of fair representation under the National Labor

Relations Act and the Railway Labor Act. Secondly, de

cisions by this court as well as other courts, have con

sistently held conduct of the type involved in the instant

case to violate Title VII., thus implicitly holding that

Whitfield is not determinative of the rights of the plain

tiffs under Title VII.2 * *

In Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, 263 F.2d 546 (5th

Cir., 1959), cert, den’d, 360 U.S. 962 (1959 ), this Court

held that an agreement between the defendants which

required Negro workers to relinquish Line 2 seniority while

with the same subject matter as an earlier court decision places a

heavy burden of persuasion upon the party relying on the res judi

cata to show that the statute has no effect on the scope of the

preclusion of claims and issues. This Circuit has adopted that rule.

See, e.g. Argo v. C.I.R., ISO F.2d 67 (S Cir., 1945). We further

submit that, at the very least, the courts are under a duty to

scrutinize closely the relationship between the new statute and the

former adjudication.

2. In another portion of our brief we will show that even if the

same statute were involved in the instant case as in Whitfield, res

judicata would not apply.

16

proceeding into all white Line 1, and which imposed new

qualifications tests upon Negroes, was consistent with the

duty of fair representation imposed upon a union as the

exclusive bargaining representative under the National

Labor Relations Act.3 Stating that “ [i]f there is racial

discrimination under the new contract, it is discrimina

tion in favor of Negroes,”4 this Court held that neither

of the above-noted factors violated the N LRA because

their existence was consistent with the lines of progression

structure which was “ conceived out of business necessity,

not out of racial discrimination.” 5 Said the Court: “This

is a product of the past. We cannot turn back the clock.”6

Plaintiffs believe that both a fuller appreciation of the

evils of racial discrimination in our society,7 the facts of

that case as reflected in the district court’s opinion,8 as

well as the direction taken by recent Title VII. decisions9

impel a re-examination of Whitfield under the National

3. 29 U.S.C. Sec. 159.

4. Whitfield, supra, at 549.

5. Id. at 550.

6. Id. at 551.

7. See Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders, 251-264 (New York Times edit. 1968).

8. 156 F. Supp. 430 (S.D. Tex. 1957).

9. Local 53, International Association of Heat and Frost Insu

lators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969); Local 189, United

Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States, _ F . 2 d _____ , 71

LRRM 3070, 60 L.C. Paragraph 9289 (5th Cir., July 28, 1969);

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers International Association,_____

F.2d-------- , 2 FEP Cases 127, 61 L.C. Paragraph 9319 (8th Cir.,

September 16, 1969); See generally Gould, The Emerging Law

Against Racial Discrimination in Employment, 64 Northwestern

University L. Rev. 359 (1969). (We feel obliged to call attention

to the fact that the author of this, as well as of several other articles

cited in this brief, is of counsel in the instant case.)

17

Labor Relations Act. But since the instant case involves

an interpretation of Title VII. of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 rather than the NLRA, that task is an unneces

sary one here.

The irrelevance in a Title VII. case of Whitfield, and

its interpretation of the fair representation obligation is

made dramatically clear by this Court’s recent opinion

in United States v. Hayes International C orp .,___ F.2d___ ,

2 FEP Cases 67, 60 L.C. Paragraph 9303 (5th Cir.,

August 19, 1969). In Hayes International Corp.— another

industrial union seniority discrimination case— Judge Tuttle,

speaking for this Court, stated the following about

Whitfield:

“Whitfield was not a Title VII. case and therefore

is not controlling. Furthermore, to the extent that it

can be read limiting the power of the court to order

‘such affirmative action as may be necessary’ [citation]

to simply barring any further application of discrim

ination practices Whitfield is inconsistent with the

words of the statute, its purposes and the thrust of

recent cases in this Circuit * * *” 2 FEP Cases at

69, n. 6.

Even prior to this court’s conclusions in Hayes Inter

national Corp. regarding the relevance of Whitfield to a

case arising under Title VII., the rationale had been fully

articulated. For, in Local 12, United Rubber Workers

v. NLRB, 368 F.2d 12, 24 (5th Cir., Nov. 9, 1966), cert,

den’d, 389 U.S. 837 (1967), this Court stated by way of

dictum that the obligations incurred as a result of the fair

representation doctrine articulated under the National

Labor Relations Act, and those imposed as the result of

Title VII., were not synonymous.

18

Especially significant is the recent decision of the Eighth

Circuit in Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad, 414 F.2d

73 (8th Cir., 1969), where an attempt was made to

equate the fair representation doctrine under the Railway

Labor Act with the right to be free from discrimination

under Title VII.10 In articulating the distinction, the court

stated the following:

“ The Railway Labor Act is not basically a fair em

ployment practice act, nor has it been utilized as

such. Its basic purpose is to foster and promote col

lective bargaining between employees and employers

with a provision for continuity of service to the

public while setting up a detailed and elaborate

procedure for the resolution of major and minor

disputes that occur in the operation of the railroad.

On the other hand, Title VII, of the Civil Rights

Act specifically prohibits racial and other discrimina

tion in employment and employment opportunities.

. . . The enactment of Title VII provides a more

extensive and broader ground for relief, specifically

oriented toward the elimination of discriminatory

employment practices based upon race, color, reli

gion, sex, or national origin. Title VII. is cast in

broad, all-inclusive terms setting up statutory rights

against discrimination based inter alia upon their

race. . . .

Surely Congress in the enactment of Title VII had

in mind the granting to a new and enlarged basis

for elimination of racial and other discriminations

in employment. Title VII clearly is not a codification

of existing law, but is an enactment of broad prin

10. It should be noted that the duty of fair representation is the

same under both the Railway Labor Act and the National Labor

Relations Act; in fact, it originated in cases involving the former

and was later carried over to the latter.

19

ciple prohibiting discrimination against any indi

vidual ‘with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions or privileges of employment because of

. . . race, color, religion, sex, or national origin’

414 F.2d at pgs. 82-83.

Even more significant is that the identical res judicata

argument, on which the lower court based its decision in

the instant case, was also made in the Norman case, but

rejected by the Eighth Circuit. Just as in this case, it was

argued that decisions, holding that conduct adverse to

Negro employees did not violate the fair representation

doctrine, were binding in a Title VII. action. They were

sharply rejected by the court:

“The Railroad contends the issue of whether the

classification of train porter is an unlawful racial

classification has been decided and the matter is now

res judicata, or, at least the plaintiffs are collaterally

estopped from raising it. Nunn v. Missouri Pacific

Railroad Co., 248 F. Supp. 304 (E.D. Mo. 1966),

was a class action brought by the train porters

alleging discrimination against them in the abolition

of train porter positions on ten passenger trains.

The District Court there held that the abolition of

these positions was not discriminatory against Ne

groes and that the question of whether the Railroad

had the right to abolish the jobs was a minor dispute

to be decided by the National Railroad Adjustment

Board. No appeal was taken from this decision. In

Howard v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co.,

361 F.2d 905 (8 Cir., 1966), the train porters in

a class action contended that they were relegated to

the class of train porter solely because of race. We

stated at 906 of 361 F.2d that the District Court

‘failed to find hostile racial discrimination.’ We

viewed the issue on appeal as whether ‘the District

Court had jurisdiction and power, to require by

20

appropriate order, that all Negro employees of

Frisco, now in the craft or class of train porter, be

placed in the craft or class of brakeman.’ Id. Both

of these cases were viewed within the context of

jurisdictional disputes or craft classifications con

stituting grievances solely cognizable under the Rail

way Labor Act. The applicability of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act to the plaintiffs’ complaint has

not been decided by the courts. We hold, that Nunn

and Howard are not a bar to the present action.”

(414 F.2d at 84).

The “new and enlarged basis for the elimination of

racial . . . discrimination” which the Eighth Circuit

found in Title VII. ( Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad,

414 F.2d at 83) undoubtedly explains the long strides

made by the courts in Title VII. cases when contrasted

with the faltering advances which had occurred under

fair representation. For instance, this Court in Local 53,

International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir., 1959), has not only

altered a discriminatory union referral system, but has

also examined and found questionable the labor market

judgments of the parties concerning the supply of labor

in a particular trade. Nothing strikes more directly at

the heart of the collective bargaining process in the craft

union context than this. But, this Court stated that:

“ . . . [I]n formulating relief from such practices

(discriminatory referrals systems) the courts are not

limited to simply parroting the Act’s prohibitions but

are permitted, if not required to ‘order such affirma

tive action as may be appropriate’ . . . . Where

necessary to ensure compliance with the Act, the

District Court was fully enpowered to eliminate the

present effects of past discrimination.” 407 F.2d at

p. 1052-1053. (Parenthesis added).

21

Of great significance to the instant case is the holding

in Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968), where the court held that a . seniority

system that has its genesis in racial discrimination is not

a bona fide seniority system” within the meaning of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that Negro workers dis

criminated against under such a system must be allowed

to carry over seniority credits previously accumulated in

the formerly all black sector of the plant, on the theory

that discrimination barring them from entering the all

white sector had prohibited them from accumulating

the seniority in the latter area. Applying the same

reasoning to the instant case, but for the discriminatory

promotion practices of the past, Negroes would have

enjoyed the protection afforded whites already in Line 1

through the accumulation of seniority credits in the

formerly white sector of the plant.31 Since the com

petitive disadvantage results from the segregation of

jobs in the past, a discriminatory effect is carried over

into the present system every time the Negro worker at

tempts to bid for a job opening and is limited by the

collective bargaining agreement’s failure to recognize

service in the segregated area. The white employee hired

off the street into the formerly all white area may have

worked only two years and yet have a superior competi

tive position in the case of promotion, lay-off and trans

it. See generally Gould, Employment Security, Seniority and

Race: The Role of Title VII. of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 13

Howard L. J. 1 (1967); Gould, Seniority and the Black Worker:

Reflections on Quarles and its Implications, 47 Texas L. Rev. 1039

(1969); Cooper & Sobel, Seniority and Testing Under Employment

Laws: A general Approach to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Pro

motion, 82 Harvard L. Rev. 1598 (1969); Note, Title VII., Seniority

Discrimination and the Incumbent Negro, 80 Harvard L. Rev. 1260

(1967).

22

fers over a Negro worker who has been employed for

twenty years in the all black department, but is without

adequate seniority protection because of the past policies.

Here this situation is aggravated by additional post-Act

discrimination in the Supplemental Agreement of 1966.

Said the Court in Quarles: “Congress did not intend to

freeze an entire generation of Negro employees into dis

criminatory patterns that existed before the Act.” Quarles

v. Philip Morris, supra, at 516.

Finally, the Quarles approach has been recently ac

cepted by this Court in Local 189, United Papermakers

and Paperworkers v. United States, ____ F .2d______, 71

LRRM 3070, 60 L.C. Paragraph 9289 (5th Cir., July

28, 1969). In that case, Quarles was relied upon to sup

port a holding that a “ job” seniority system was unlawful

where it “ carried . . . forward the effects of former

discriminatory practices [and] the system [resulted] . . .

in present and future discrimination.” Id. at 3071.

One can reasonably expect defendants to attempt to dis

tinguish the instant case from the facts of those contained

in both Local 189 as well as Quarles since both of those

opinions distinguish Whitfield. It is clear, however, that

the Papermakers case is completely inconsistent with any

notion that a Whitfield-type, arrangement would be upheld

if it were attacked under Title VII. instead of under the

fair representation doctrine.

Judge Wisdom, who was the writing judge in both

Whitfield and Papermakers, has clearly pointed out the

differences between the legal standards under the different

statutes invoked in the two cases. In Whitfield:

“ The question before the Court [was] whether the

May 31 contract [the 1956 agreement] is fair . . .

23

What is fair is a moral decision resting on the

conscience of the Court.” 263 F.2d at 547.

In referring to the problem of discrimination against

the Negroes’ interline mobility, the Court said:

“ This is a product of the past. We cannot turn back

the clock. . . . We have to decide this case on the

contract before us and its fairness to all.” 263 F.2d

at 551.

But ten years after holding that a federal court was un

able, under the fair representation doctrine, to remedy

current effects of prior discrimination, Judge Wisdom

wrote in Papermakers:

“We hold that Crown Zellerbach’s job seniority

system in effect at its Bogalusa Paper Mill prior to

February 1, 1968, was unlawful because by carrying

forward the effects of former discrimination prac

tices the system results in present and future dis

crimination.” Slip opinion at p. 3.

The obvious shift in the legal standards governing

seniority systems stems not from this Court’s having a

change of visceral reaction, but, quite properly, from the

enactment of Title VII. which, in effectuating the broad

purpose of Congress to redress those wrongs unreachable

by the duty of fair representation, makes it unlawful for

an employer

“ . . . to limit, segregate or classify his employees

in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive

any individual of employment opportunities or other

wise adversely affect his status as an employee be

cause of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex,

24

or national origin.” Section 7 0 3 (a )(2 ) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C., Sec. 2000e-2(a) (2 ) .

Plaintiffs do not now need to prove to this Court that

the seniority system at the Armco facility in Houston is

in fact violative of Title VII. Although under the Paper-

makers decision, the seniority system in effect at the

Armco facility in Houston clearly seems to violate the

equal employment rights of at least some of the Negro

employees. All that plaintiffs ask is that they be given

the chance to prove to the district court that their Title

VII. rights have been infringed. The district court, perhaps

laboring under the misconception that plaintiffs were

owed no additional duties by virtue of Title VII., said, in

effect, that plaintiffs could not relitigate their Whitfield-

type claims. Just fourteen days after the district court’s

decision, this Court decided Papermakers, which, for the

first time, clearly defined Title VII. law with respect to

seniority systems in this Circuit. We suggest, therefore,

that the Papermakers decision is an adequate ground for

invoking the summary procedures of this Court in order

to reverse and remand the case to the district court so

that plaintiffs can have their “ day in court” on their

Title VII. claims.12

Respect for the stare decisis effect of this Court’s pro

nouncement of Title VII. law in Papermakers should

12. Our suggestion that this case is ripe for summary reversal

pursuant to Local Rules 17-20 is in no way a waiver of our right

to oral argument, should the Court disagree with our reading of

Papermakers. Indeed, but for this one ground for summary reversal,

plaintiffs submit that this case is of major importance in defining the

differences between Title VII. and fair representation claims. We

therefore respectfully ask that, if the screening panel does not sum

marily reverse, this case should not otherwise be removed to the

summary calendar.

25

suffice for a holding in the present case that the district

court erred because it failed to give effect to Title VII.’s

imposition of affirmative duties upon employers and

unions. Nevertheless, it may be useful to highlight briefly

some analogous situations in which the Supreme Court

has held that Congress may impose affirmative duties upon

majorities to redress the present effects of past discrimina

tion against minorities. In the area of voting rights this

doctrine had its genesis in the case of Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, (1965). In that case the Supreme

Court, through Mr. Justice Black, said that close restraints

imposed by the district court were justified by “ [t]he need

to eradicate past evil effects and to prevent the continua

tion or repetition in the future of the discriminatory prac

tices shown to be so deeply engrained in the laws . . .

of Louisiana.” 380 U.S. at 156. In the course of a general

discussion of the district court’s power to protect the

franchise, Justice Black said:

“We bear in mind that the court has not merely the

power but the duty to render a decree which will

so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects

of the past as well as bar like discrimination in the

future.” 380 U.S. at 154.

Protection of the franchise was once again at issue

when the Supreme Court decided the case of Gaston

County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285, (1969). In that

case the Supreme Court held that a challenge to literacy

tests based upon the unequal educational opportunity af

forded Negroes in North Carolina was permissible under

the Voting Rights Act of 1965. One of the county’s argu

ments was that its impartial administration of the tests

would not deny anyone his Constitutional rights. The

26

Supreme Court, by Mr. Justice Harlan, made short shrift

of the allegations that today’s educational opportunities

and today’s impartiality obviate any Constitutional prob

lem:

“ ‘Impartial’ administration of the literacy test today

would serve only to perpetuate these inequities in a

different form.”

By the same token, “ impartial” administration of the

seniority system imposed by the defendants in the instant

case would serve only to perpetuate the more blatant

inequities of the past in a more sophisticated form. And

this Court has, in effect, so held, in Papermakers, supra.

To summarize, the legal standards in effect at the time

of Whitfield mandated only that the plaintiffs there be

fairly represented in the contract negotiations. The courts,

under the Steele Doctrine, could not remedy past wrongs

which were locked into present contracts, so long as the

contracts were “ fair” to all employees. Whitfield, supra.

Title VII. changed the obligations owed to individual

employees and the remedies available for breach of those

obligations.

“Every time a Negro worker hired under the old

segregated system bids against a white worker in his

job slot, the old racial classification reasserts itself,

and the Negro suffers anew for his employer’s pre

vious bias. It is not decisive therefore that a seniority

system may appear to be neutral on its face if the

inevitable effect of tying the system to the past is

to cut into the employees present right not to be

discriminated against on the ground of race. The

crux of the problem is how far the employer must

go to undo the effects of past discrimination.” Paper-

makers, Slip Opinion, p. 15.

27

Under fair representation, Whitfield taught that the

clock could not be turned back. Under Title VII., Paper-

makers teaches that it finally can:

“When an employer adopts a system that necessarily

carries forward the incidents of discrimination into

the present, his practice constitutes on-going dis

crimination, unless the incidents are limited to those

that safety and efficiency require.” Papermakers, Slip

opinion, p. 30.

Moreover, in this case the Court, in order to reverse,

would not even be required to accept the broad pro

nouncements about past discrimination already handed

down here in Papermakers; one finds independent dis

criminatory conduct engaged in by the defendants sub

sequent to the effective date of Title VII. in the form

of the Supplemental Agreement of 1966. As is noted

above, the effect of this Agreement was to thwart the

very limited advance of Negro workers at the Structural

Mill Department. A similar post Title VII. arrangement

impedes progress of intervenors in the open hearth depart

ment. This kind of independent post-Act discrimination

was not present in Papermakers or Quarles and such

evidence was not relied upon to establish the conclusions

of law in those cases. Their holdings should apply a

fortiori to the instant case.

We, therefore, ask this Court to recognize its own new

standards and to remand this case so that plaintiffs may

have a chance to show the district court that their rights

under Title VII. have been violated.

It should be pointed out, that while a hearing on re

mand may produce evidence of purposeful discrimination

in the sense that the defendants are shown to be of a

discriminatory state of mind, such a finding is hardly a

28

prerequisite to a Title VII. violation. This issue, as well,

was squarely raised in Papermakers and squarely disposed

of:

“Section 706(g ) limits injunctive (as opposed to

declaratory) relief to cases in which the employer

or union has ‘intentionally engaged in’ an unlawful

practice. Again, the statute, read literally requires

only that the defendant meant to do what he did,

that is, his employment practice was not accidental.”

See also Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505,

at 517-518. Thus, even if the court below had been cor

rect in excluding from the case “ any reference to the effect

of Armco’s system of dual lines of job progression whether

the effect is past or present [nor] any other questions

resolved in the Whitfield decision” (R. p. 81-82), it would

still have erred in limiting the plaintiffs to a showing that

the Supplemental Agreement of 1966 “was negotiated in

an effort to discriminate” and that it “was born out of

racial discrimination.” (R. p. 117).

2. TH E D ISTR IC T C O U R T ERRED IN FA IL

IN G T O FIN D T H A T APPELLANTS RAISE FA CT

ISSUES A N D PLEAD CIRCUM STANCES W H IC H

AROSE AFTER TH E DECISION OF WHITFIELD

A N D , THEREFORE, EVEN IF TITLE VII. IM

POSED N O N EW OBLIGATION S U PO N TH E

EM PLOYER A N D U N IO N W H IC H DIFFER FROM

TH E O BLIGATION S IMPOSED U N D ER TH E N A

T IO N A L LABOR RELATION S A C T , CHANGES

IN TH E EM PLOYM ENT RELATIONSH IPS OF

TH E PARTIES SINCE TH E WHITFIELD D ECI

SION PREVEN T WHITFIELD FROM C O N T R O L

LIN G TH E PLAINTIFFS’ A N D IN TER VE N O R S2 * * 5

PROCEEDINGS.

29

Not only are plaintiffs suing under a different statute

from that invoked by their predecessors in Whitfield; they

are also basing their claim in large part upon different

facts.

At the time of the Whitfield decision, each employee

in Line 1 had to pass through every job class on his way

up the ladder. Business necessity dictated that this prac

tice be followed, lest efficiency be impaired through de

ployment of less competent people in more demanding

positions. The district court in that case specifically so

found. Findings of Fact Numbers 21-32, 156 F.Supp. 430,

434-37. For example, “ the reason for promotion by sen

iority within a Line of Progression has been to ensure the

full development of each employee in each successive job

in the Line of Progression, thereby assuring to the com

pany that the employee will develop maximum experience

and know-how within the particular phase of operation

before moving upward to the next job.” Finding of Fact

31, 156 F.Supp. 436. This Court, in affirming, reached

the same conclusions as to the facts: “The knowledge

acquired in a preceding job is necessary for the efficient

handling of the next job in the progression.” 263 F.2d

546, at 548.

Business necessity dictated such step-by-step advances

when they served to explain why Negroes had to start at

the bottom of the ladder of Line 1, and why they could

not bring with them the seniority they had accumulated

in Line 2. But now, when the requirement of step-by-step

advances through each successive job would serve to keep

some white employees with greater line seniority (but in

lower job classes) from leapfrogging over and displacing

Negro employees with less Line 1 seniority (but in higher

30

job classes), a new fact has suddenly entered the picture

— it is apparently no longer deemed necessary (by Armco

and the union) for the efficiency of the business that there

be “the full development of each employee in each suc

cessive job in the Line of Progression.” Moreover, Negroes

were permitted to fill Line 1 jobs above the baseline job

class in Line 1 on temporary arrangements (some quite

extended) without first having to work up the line to such

jobs and without any training other than that normally

acquired on the job.

It is not necessary that the plaintiffs claim that this

switch in position on the part of the defendants is the

result of bad faith. The defendants have now evidently

concluded that advancement through each job class is no

longer necessary for safety, economy or efficiency of

operations. Hence the facts have changed. And those

which obtained, and were decisive, at the time of Whit

field are no longer true.

A survey of the discriminations suffered by two of the

named plaintiffs will further demonstrate that the sub

stance of the present claim differs from Whitfield and that

the causes of action are therefore not identical for res

judicata purposes.

As to allegations concerning plaintiff Reden: After ac

cruing eighteen years of plant seniority and fifteen years

of departmental seniority in the Structural Mill Depart

ment, Luther Reden lost his Class 12 job solely because

the job was opened to bid by the 1966 Agreement (R.

p. 11). Reden’s claim has absolutely nothing to with the

Whitfield-type situation of an employee’s being inhibited

in moving from Line 2 to Line 1. It should be noted that

31

Reden has nine years of Line 1 seniority. Moreover, he

was an incumbent in the Class 12 position, and we should

be permitted to argue in the district court that incumbency

should be tantamount— or indeed far superior— to the

temporary filling of jobs, for the purposes of establishing

one’s qualifications for it. It will be our position in the

trial court that defendants have shown and cannot now

show a compelling “business” reason for the open bid

system and that therefore its discriminatory effects is its

only raison d’etre. What is important for our purpose

on this appeal is for this Court to notice that Reden is not

concerned with interline mobility, but merely with keeping

his job vis-a-vis lower ranking white contestants in his

own line.13

As to allegations concerning plaintiff Taylor: This

plaintiff has twenty-three years of plant seniority and

twenty-three years of departmental seniority, all in the

Structural Mill Department. He has worked in Line 2

from Class 2 through 9 and in Line 1 from Class 5 through

10 (R. p. 12). He does not assert any inability to move

from Line 2 to Line 1 as the plaintiffs in Whitfield did.

Rather, he asserts that the 1965 agreements made his

Class 10 job desirable to whites with less plant and

department seniority than he. He further asserts that the

1966 agreement allowed such whites to bid successfully on

his job solely because of their having more Line 1

seniority which, but for the fact of past discrimination,

13. It should be noted that Reden’s job, which was the top Negro

position in the department, was the top job to be opened to bid.

Perhaps a more charitable person would urge that this was mere

coincidence. Plaintiffs, however, who are struggling for the oppor

tunity to work, assert that this is some evidence of defendants’ dis

criminatory intentions.

32

he would have over them. Taylor thus challenges the open

bid system as an overt attempt to subvert the orderly lines

of the progression system whereby only those employees

in the slots immediately below the open job could bid

for it. Under the 1966 agreement a white in Class 5

with three years of line seniority can deprive a Negro in

Class 10 of his job if the Negro has only two years of

Line 1 seniority— all in disregard of (a ) Negroes’ long

time department and/or plant experience and (b ) the

Negroes’ incumbency in the very job at issue (as con

trasted with the white’s lack of experience in any job even

close to it on the ladder).

It is apparent from this discussion that the same wrongs

are not being committed and the same rights are not being

infringed. Plaintiffs seek a chance to prove this in court.14

14. The term “ res judicata” is generally used to define a binding

effect of prior adjudications upon present litigation. Res judicata in

its pure form (sometimes characterized as “ merger” or “bar” ) is

properly invoked where the same parties contest the same causes of

action in successive suits. “ Collateral Estoppel” covers the operation

of the principal of repose in a subsequent suit, between the same

parties, involving a different cause of action, but with issues in

common. See generally Developments in the Law: Res A judicata,

65 Harv. L. Rev. 818 (1952). This Circuit has repeatedly recognized

these the fundamental differences between res judicata and collateral

estoppel, see Compania Mexicana v. Jernigan, 410 F.2d 718, 726

(5th Cir.,. 1969) (collateral estoppel); Astron Industrial Associates,

Inc. v. Chrysler Motors Corp., 405 F.2d 958, 960 (5th Cir., 1968)

(res ajudicata). Plaintiffs respectfully submit that an analysis of the

principles recognized in the cases in this Circuit will clearly show

that the district court erred in foreclosing plaintiffs from their day

in court on their Title VII. claims—whether res judicata or collateral

estoppel is asserted as a bar to relief from racial discrimination.

It is the general rule that collateral estoppel applies only to foreclose

litigation of identical issues. Moore, supra at Sec. 0.441 [2], Jernigan,

supra. The courts generally look behind the face of the judgment to

determine the scope of the estoppel. United Shoe Machinery Corp. v.

U. S., 258 U.S. 451, 459 (1922); Teas v. Twentieth Century Fox

33

3. T H E D ISTR IC T C O U R T ERRED IN FAIL

IN G T O EXERCISE ITS D ISCRETIO N T O LIM IT

TH E APPLICABILITY OF RES JU D IC A T A A N D

CO LLATERA L ESTOPPEL W H ERE TH ERE ARE

ALLEG ATIO N S T H A T TH ERE H AS BEEN A SIG

N IF IC A N T C H AN G E IN CIRCUM STANCES OR

W H ERE TH E PRECLU SION ARY PRINCIPLE

W O U LD SERVE N O USEFUL END.

Appellants’ final argument is directed to the inherent

equitable discretion of the court. Although sympathetic

to the plight of these long-term employees who, but for

their color, would be entitled to the positions which they

had worked so hard to attain, the district judge apparently

did not consider himself possessed of discretion to temper

the harsh and sometimes unfair effects of the doctrines

of repose. In addition to the legal arguments heretofore

made, Appellants contend that equitable and practical

considerations dictate that Appellants be allowed to liti

gate their Title VII. claims for the first time.

That the district judges of the United States possess

such discretion to mitigate the rigors of res judicata

Films, Inc., 413 F.2d 1263, 1267 (5th Cir., 1969). This Court need

not go so far, for the judgment on its face is conclusive on the point

of lack of identity between the issues in Whitfield and here. Title

VII., the 1965 agreement, and the 1966 agreement had not yet come

into existence at the time of Whitfield. Moreover, Judge Wisdom

indicated in the Whitfield opinion that the complaint was based on

the duty of the union to represent the employees fairly. What is

dispositive of the collateral estoppel point is the observation of Judge

Wisdom in Papermakers, that, “ \t\here was no issue in Whitfield

as to the measure of promotion from one job to another.” No other

statement could more clearly convey the idea that collateral estoppel

there cannot foreclose plaintiffs’ intraline mobility claims. Plaintiffs

rest upon this observation and the support found in Judge Wisdom’s

opinions and in Point 1 of the argument in this brief.

34

principle is an eminently fair and well-settled doctrine.

See, generally, IB M oore’s Federal Practice at pp. 621,

631. The principles of preclusion have been qualified by

public policy, considerations of federalism and supremacy,

and pure equitable discretion to avoid unfair results. Id.

Sec. 0.405. At least two of these doctrinal exceptions are

applicable to this case.

We suggest that an overriding public policy of national

equal employment opportunity mandates a tempering of

res judicata in this case. The National Labor Relations

Act was the basis for refusing to apply res judicata to

a prior court action. See Denver Building & Construction

Trades Council v. N.L.R.B., 186 F.2d 326, 332, (D.C.

Cir., 1950), reversed on other grounds, 341 U.S. 675

(1951). The Supreme Court has indicated that the plenary

power over bankruptcy possessed by Congress should

override considerations of judicial finality whenever the

two principles collide. Kalb v. Feuerstein, 308 U.S. 433,

444, (1940). Surely the Congressional power to regu

late commerce as manifested in so important an area as

race relations cannot be stunted by a genuflective response

to the doctrine of judicial finality.

Appellants’ further suggest that considerations of equity

mandate a tempering of this overly harsh application of

foreclosure principles. First, res judicata should not be,

and has rarely been, applied when new economic or

social conditions have intervened. The Supreme Court

last year examined the merits of an attack upon full-crew

laws which the railroad companies had litigated to finality

several times in the past. Mr. Justice Black disagreed

with the district court’s holding “that the railroads have

shown a change in circumstances sufficient to justify de

parture from our three previous decisions.” Brotherhood

35

of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen v. Chicago R.I.

& P. R. Co., 393 U.S. 129, 131, (1968). However, the

fact that the Supreme Court considered the issues afresh

and decided the case on the merits, rather than summarily

reversing on grounds of res judicata, clearly indicates

that it adheres to the principle that a material change in

circumstances can be the basis for invoking an equitable

limitation upon the doctrine of res judicata. See M oore’s

Federal Practice, Sec. 0.415. When litigation is not need

less and repetitive but reflects such a material change in

circumstances, then a court should not be quick to cut

off the important right to be heard in a public forum.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the judgment of the

district court should be reversed and the case remanded

to the district court for such further proceedings as

justice shall require. Appellants ask for such other and

further relief as this Court might deem necessary and

proper to do justice, including, as the Court may see fit,

a ruling upon whether the Whitfield facts are, per se,

proscribed by Title VII., or such instructions as the Court

36

may deem useful or necessary for the ordering of proceed

ings upon remand.

Respectfully submitted,

M a n d e l l & W r ig h t

By--------------------------------------------

1901 First National Life Building

Houston, Texas 77002

M cD o n a l d & M c D o n a l d

By—---------- ----------— --------- _

1834 Southmore Boulevard

Houston, Texas 77004

Ja c k G r e e n b e r g

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel:

W il l ia m B. G o u l d

Wayne State University

Law School

Detroit, Michigan

J o n a t h a n K . H a r k a v y

2 Wall Street

New York, New York

A l b e r t J. R o s e n t h a l

435 West 116th Street

New, York, New York

37

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the . day of November,

1969, a true and correct copy of the foregoing was

served upon: Mr. Chris Dixie, 505 Scanlan Building,

Houston, Texas, Attorney for Armco Steel Corporation,

and Mr. George Rice, Messrs. Butler, Binion, Rice, Cook

& Knapp, Esperson Building, Houston, Texas, 77002,

Attorneys for United Steel Workers of America, AFL-CIO,

and Local 2708, United Steel Workers of America, AFL-

CIO, by placing the same in properly addressed envelopes,

postage prepaid, and depositing the same in the United

States mail.

N o r m a n So r r e l l