Maddox v Claytor Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 6, 1984

68 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maddox v Claytor Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1984. dd87553b-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16a65ed5-0e2d-4971-a8a3-cc62c06699fa/maddox-v-claytor-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

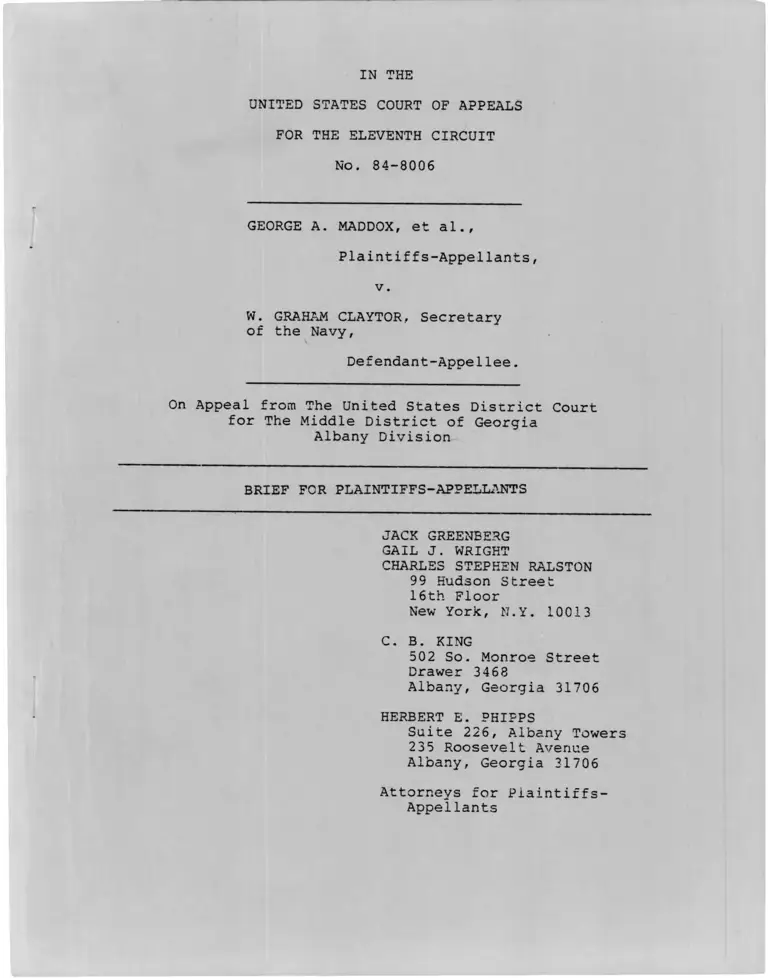

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-8006

GEORGE A. MADDOX, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, Secretary

of the Navy,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Middle District of Georgia

Albany Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

GAIL J. WRIGHT

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

C. B. KING

502 So. Monroe Street

Drawer 3468

Albany, Georgia 31706

HERBERT E. PHIPPS

Suite 226, Albany Towers

235 Roosevelt Avenue

Albany, Georgia 31706

Attorneys for Piaintiffs-

Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-8006

GEORGE A. MADDOX, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, Secretary

of the Navy,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Middle District of Georgia

Albany Division

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record for plain

tiff s-appellants certifies that the following listed persons

have an interest in the outcome of this action.

A. >As plaintiffs-appellants.

1. The named plaintiffs-appellants:

a. George A. Maddox,

b. William D. Abad, and

c. Eric D. Shepherd;

2. The class of Blacks now employed or formerly

employed by defendant Marine Corps Logistics Base, Atlantic

located in Albany, Georgia;

B. As defendants-appellees.

1. W. Graham Claytor, Secretary of

the Navy

2. Major General F. Sullivan,

Commanding Officer

3. Warren R. Johnson, former

Commanding Officer

4. Clarence H. Schmid, former

Commanding Officer.

5. Carl R. Lee, Civilian

Personnel Officer

6. L. Lamar Wiggins, former Civilian

Personnel Officer

7. George C. Small, Director of

Equal Employment Opportunity

8. Donald Devine, Director, Office of

Personnel Management (formerly U.S.

Civil Service Commission).

These representations are made pursuant to Rule 22(f)(2) of

the Local Rules for the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit in order that judges of this Court,

inter alia, may evaluate possible disqualification or

refusal.

Respectfully submitted,

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-8006

GEORGE A. MADDOX, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, Secretary

of the Navy,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Middle District of Georgia

Albany Division

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

In accordance with Local Rule 22(f)(4) plain

tif fs-appellants respectfully request oral argument of this

appeal. This matter raises substantial and complex ques

tions of law regarding the appropriate standards of proof in

pattern and practice class actions instituted pursuant to

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, as amended. Further,

notwithstanding plaintiffs' unrebutted evidence, the Court

below totally neglected to address plaintiffs' claim that

the defendant's failure to develop, implement or maintain an

affirmative action plan violated Section 717(b) of the Act.

Finally, this action concerns the rights of named plain-

tiffs and class members to a trial on their individual claims.

Plaintiffs-appellants submit that the District

Court's errors are clear from the record. However, oral

argument is requested to assist in the presentation of the

factual issues and in order to facilitate the resolution of

the legal arguments presented in this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS ................ i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT ................ iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................. V

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES ........................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................. 2

A. Course of Proceedings and

Disposition in the Court Below ..... 2

B. Statement of the Fact................ 4

C. Standard of Review .................. 34

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................... 34

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ......................... 35

ARGUMENT ........................................... 36

I. The Court Below Erred In Holding That

The Statistical Evidence Did Not

Establish Discrimination ................ 36

A. The Appropriate Comparison For

Wage Board Promotions Was The

Internal Workforce .................. 36

B. Plaintiffs' Promotion Study Demon

strated Discrimination .............. 42

C. The Defendant's Statistical Proof

Supports A Finding Of

Discrimination ...................... 45

D. The Failure To Validate The

Qualifications Standards And

Procedures Violates Title VII ...... 47

II. Defendant's Failure To Develop An

Effective Affirmative Action Plan

Constitutes A Violation of Section

717(b) Of The Act ........................ 49

v

Page

III. The Court's Decision With Regard To The

Individual Claims Were In Error ......... 53

A. The Named Plaintiff And Members Of

The Class Are Entitled To Present

Their Individual Claims ............. 53

B. Relief must Be Awarded To Those

Class Members Whom The Court Deter

mined Had Been Subjected To Racial

Discrimination ....................... 55

CONCLUSION .........................................

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ............................

vi

Cases Pa9e

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543

(4th Cir. 1975) .............................. 40

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refinery Corp., 495

F. 2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974) ..................... 54

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425

U.S. 820 (1976) .............................. 50

Carroll v. Sears Roebuck & Co., 708 F.2d 183 (5th

Cir. 1983) ................................... 36' 37

Clark v. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330 (9th Cir. 1980) ... 50

Connecticut v. Teal, ___ U.S. ___, 73 L.Ed.2d 130

(1982) ........................................ 54

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank, S.Ct. No. 83-185 . 55

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, ___ U.S. ___,

76 L . Ed . 2d 628 (1983) ........................ 55

*Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1979) 36, 39, 41

*Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 704 F.2d

613 (11th Cir. 1983) ......................... 45, 55

*EEOC v. American Nat'l Bank, 652 F.2d 1276 (4th

Cir. 1981) .................................... 41

Fisher v. Proctor & Gamble Mfg. Co., 613 F.2d 527

(5th Cir. 1980) .............................. 53

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ........................................ 54

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F .2d 1007

(2d Cir. 1980) ............................... 40 , 41

*Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ... 44, 47

Harrison v. Lewis, 559 F.2d 943 (D.C.C. 1983),

aff'd per curiam, ___ F.2d ___ (D.C. Cir.

March 1, 1984) ............................... 44

Table of Authorities

* Authorities principally relied on.

- vii -

Cases Page

*Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 ( 1977) .......................... 23 , 40, 41

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc., 628 F.2d 419 (5th

Cir. 1980) .................................... 36 , 47

*Lawler v. Alexander, 698 F.2d 439 (11th Cir.

1983) ......................................... 26, 43

*McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F .2d 62 (D.C. Cir. 1982) 49

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 ( 1974) ........... 50

Parson v. Kaiser Alum. & Chem. Corp., 575 F.2d

374 (5th Cir. 1978) ..................... 53

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, 673 F.2d 798 (5th

Cir. 1982) ................................... 36, 37

Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Service,

699 F . 2d 760 (5th Cir. 1983) ................ 24, 41

Pnillips v. Joint Legislative Committee, 637 F.2d

1014 (5th Cir. 1981) .......................... 57

Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp. 690 (D.D.C. 1981) 41

Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263 (10th

Cir. 1975) ...................................

*Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) . 39, 40, 41, 53

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C.Cir. 1982) . 50

*Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094 (D.C. Cir. 1983)

vacated, U.S. , 52 U.S.L.W. 3628

(1984) ........................................ 21, 37

United States Postal Service Bd. of Governors

v. Aikens, ___ U.S. ___, 75 L.Ed.2d 403

(1983) ........................................ 21

Valentino v. United States Postal Service, 674

F. 2d 56 (D.C. Cir. 1982) ........................ 45

Table of Authorities

* Authorities principally relied on.

- viii -

Statutes, Regulations and Rules: Pa9e

Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 ................. 52

*Federal Personnel Manual ......................... 12, 32, 51, 52

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 .............................. passim

29 C.F.R. §1607 , et ................................ 48, 52

Uniform Guidelines for Employee Selection

Procedures ................................... 13 * 48, 52

Other Authorities:

*H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1971) 39, 47, 50

Schlei & Grossman, Employment Discrimination Law

(2nd Ed. 1983) ................................. H

*S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1971) . 38, 40, 47

* Authorities principally relied on.

- ix -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-8006

GEORGE A. MADDOX, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

w. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, Secretary

of the Navy,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Middle District of Georgia

Albany Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

I. Did the district court err in concluding that the

statistical evidence did not establish classwide

racial discrimination in promotions in violation

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended?

II. Did the district court err in concluding that de

fendants' statistical evidence was sufficient to

demonstrate that there was no racial discrimina

tion with respect to promotions?

III. Did the district court err in neglecting to address

plaintiffs' allegation that the defendant's failure to

develop and implement an affirmative action plan violates

selection 717(b) of the Act?

IV. Did the district court eer in failing to afford the

named plaintiffs, George A. Maddox and William D.

Abad, and class members an opportunity to present

their individual claims?

V. Did the district court err in failing to award appropriate

relief to class members whom the court found had been

subjected to unlawful employment practices?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course of The Proceedings And Disposition in

The Court Below

This lawsuit was instituted as a class action by

George A. Maddox, William D. Abad and Eric D. Shepherd, three

Black employees of the Marine Corps Logistics Base, Atlantic,

[hereinafter referred to as "The Base" or "defendant"] to

enforce rights granted by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of March 24, 1972, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b). The action was

triggered in accordance with federal regulations establishing

the procedures for raising class claims.

On January 6, 1978 the Complaint was filed in the

District Court for the Middle District of Georgia on behalf

of three named plaintiffs, seventeen named members of the

class and other Black employees challenging the racially

2

discriminatory employment policies and practices or the

Base. (R. E. 10; 18-26).

On December 6, 1979 the District Court certified

the class to include "all past, present and future Black

civilian employees and applicants for employment at the

Marine Corps Logistics Base. (R. 548 ). —^ In an Order of

March 18, 1980 the court redefined the class to include "all

present, past, and future black employees of the Marine

Corps Logistics Base, Albany, Georgia who since January 28,

1977, have been unlawfully discriminated against by employment

practices of the Marine Corps Logistics Base. Specifically

excluded are employees of the "tenant" activities on the base

which are not within the control of defendant . . .", (R.

600 ) .

This case was tried before the Honorable Judge

Wilbur D. Owens, sitting without a jury, commencing on April

6, 1981. During the four days of trial plaintiffs challenged

various employment policies and procedures practiced by the

1/ on January 8, 1980, the defendants moved for decertifi

cation of the class. In the alternative, defendants sought

a delineation of the class to exclude applicants for employ

ment (R. 550-552) [It should be noted that page three (3) of

"Defendants' Memorandum In Support of Motion to Reconsider

And/Or Hearing on Definition of Class" is missing from the

Record.]

3

Base, and alleged violations of the federal equal employment

opportunity and affirmative action regulations. In support

of these claims of racially discriminatory disparate treat

ment and disparate impact, and regarding defendant's failure

to comply with the affirmative action requirements of the

Act, plaintiffs offered a plethora of statistical, documen

tary and testimony evidence.

In an Order dated November 4, 1983 the district

court found that the evidence failed to support plaintiffs

class claims: (R. E. 59) Further, the Court denied the

claims of the two named plaintiffs, George A. Maddox and

William D. Abad. (R. E. 60-61). The court did find for and

grant individual relief to Mr. Shepherd. (R. E. 60). The

court's judgment was entered on November 4, 1983 (R. E. 36).

The present appeal of the trial court s November

4, 1983 Opinion/Order was timely filed on January 3, 1984.

B. Statement of The Facts

1. The Parties

George A. Maddox, one of the three named plaintiffs in

the action has been employed by the Base, as a Wage Grade

(WG) employee since 1974. (R. E. 15-16.) William D. Abad

has been a General Schedule (GS) employee with the Base

since 1976, prior to that time he had been employed by the

Marine Corps Logistics Base in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as

of 1954. (R. E. 16-17). Eric D. Shepherd, a General

Schedule (GS) employee has been employed by the Base since

1958. (R.E. 17-18).

4

The defendant is the Marine Corps Logistics Base,

Atlantic located in Albany, Georgia.

2. The Organization of The Base

The function of the Marine Corps Logistics Base is to

procure, maintain, repair, rebuild, store, distribute and

inventory supplies and equipment. (R. 1014) . In addition,

the Base conducts schools and training; and provides ser

vices to the support operations of activities and units of

the operating forces of the Marine Corps. (Id.)

The Base is composed of twelve divisions known as

"cost work centers" which as of 1979 employed approximately

2,200 persons. —^ These divisions are under the general

supervision of a Commanding Officer who is responsible

for implementing personnel policies. (R. 1015). All of

the Base Commanders, during the relevant time period, have

been White (Id.) The Civilian Personnel Office and the

Equal Employment Opportunity Office are the two major offi

ces which are responsible for personnel matters. (Id.).

L. Lamar Wiggins who was the Civilian Personnel Officer

from January 1975 until 1974 was replaced by Carl R. Lee,

who held the position at the time of trial (R. 1015).

Both of these Civilian Personnel officers are White. (Id.).

The majority of the persons employed in the Personnel Office

are White. (Lee Dep. 22).

2/ As of October 1980 the twelve centers were material

(406) facilities and service (291) centralized design (97),

comptroller (143) repair, (578) technical operations (167)

supply operations (156) deputy chief (30), logistics systems

(36), personnel/administration (109), contracts (57), and

provisioning (71). (R. 864).

- 5 -

3. Employee Classifications and Pay Schedules

All of the civilian jobs at the Base are cate

gorized according to two main pay schedules: the general

schedule known as "GS", which covers white-collar or graded

employees, whose salaries are nationally determined and

fixed by Congressional acts; and the federal wage system

which covers persons employed in trades, crafts, labor or

blue-collar positions whose wages are fixed and adjusted

administratively according to the wage rates in the local

area. (R. 1016-1017).

Each pay schedule is divided into levels or

grades identified by numbers, and the higher the level, the

greater the base rate of pay. (R. 1017). Each pay level

is further divided into "steps" and the higher the step the

greater the pay. (Id.) In addition, the salary of an em

ployee in a non-supervisory position has a lower salary than

a supervisory level employee with the same step and grade.

(Id.). As of 1979, the total workforce was 2,225? 1697 or

76.2 percent White and 528 or 23.7 percent Black. (R. 864).

4. The Key Components of the Personnel

System 3/

A. OVERVIEW

The majority of the supervisory workforce at the

Base are White. Supervisors have an all encompassing role

in the personnel system. Supervisors have the initial au-

3/ See also R. 1052-1070, Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law.

6

thority to create a position; determine career ladder ad

vancement, determine and establish qualifications for the

position; train and prepare applicants for advancement;

submit appraisals which affect promotional opportunities,

and recommend members for the ranking panels. They were

the ultimate power to select the candidate, to be promoted.

While obstensibly based on objective merit and job related

criteria, the Base's promotion schemes place heavy reliance

on the subjective appraisals and judgments of supervisors,

the majority of whom are White.

B. COMPETITIVE AND NON-COMPETITIVE

PROMOTIONS

Job vacancies within the Base may be filled by

promotion, re-assignment, transfer, temporary promotion or

hiring from the outside (PX 5). Since there are no restric

tions of the area of consideration, employees may be se

lected from the internal workforce or from outside the Base.

(Lee Dep. 150-154; Tr. Vol. Ill 104-106; PX 3).

Promotions at the Base, in common with all fed

eral agencies operating under the civil service system, are

essentially of two kinds, competitive and noncompetitive.

The majority of the promotions at the Base are competitive

(Tr. Vol. Ill, 104-105; Lee Dep. 36-42, 150-154). The

procedures for filing a competitive position are the same

irrespective of whether the person is a Base employee seeking

a promotion or an outsider seeking to be hired into the

7

4/agency. (PX 3 [FPMChap. 335]. Inititially, the super

visor with the ultimate selecting authority, or the division

director, issues a vacancy announcement which creates and

describes the position to be filled. (Lee Dep. 43, 158-160;

Tr. Vol. Ill, 80). The supervisor, in conjunction with

a staffing specialist from the personnel office, develops

the job elements that will be used to determine the eligi

ble candidates. (Lee Dep. 43; Deiter Dep. 15, 18, 23).

Persons who believe they are qualified submit

a "171 Form" which is an official federal government appli

cation on which applicants state their qualifications.

Individuals may also submit supplemental information.

) The Base does not officially provide any guidance

to employees with regard to the completion of the form.

Nor does the Base review or verify the accuracy and complete

ness of the data (Lee Dep. 56-57; 60-62, 73; Tr. Vol. Ill,

84). All applications are forwarded to the Personnel Office,

and if the applicant meets the minimum eligibility require

ments, the Personnel Office solicits a "supervisory appraisal"

from the applicant's immediate supervisor. (R. 1018; Lee

Dep. 65-66; Deiter Dep. 28; Tr. Vol. Ill, 84). Supervisors

—/ the applicant does not already possess a civil

service rating, the agency must obtain a certification

from ̂ OPM (formerly CSC) that the person is eligible for

appointment to the federal service at the grade level in

question. (PX 3 FPM Chap. 335] Otherwise, the process

for determining qualifications, rating, ranking and selec

tion is the same. See Schlei and Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law (2nd Ed. 1983) at 1187 n. 5.

8

do not receive specific instructions regarding the com

pletion of the appraisals, other than the general guidelines

in the document itself. (Lee Dep. 65-66; Tr. Vol. Ill, 84;

Deiter Dep. 28).

The division director where the vacancy exists

recommends the names of persons whom he knows personally to

rate and rank the andidates (Lee Dep. 83; Deiter Dep. 30;

Tr. Vol. Ill, 85). Panels composed of three or a minimum of

two persons, evaluate each candidate's credentials on "ran

king sheets" based upon their unguided assessment of the

Form 171 inclusive of any supplemental information, the

performance appraisal and the supervisory appraisal. (R.

1018; Tr. Vol. Ill, 85-86; Lee Dep. 57, 76, 84, 87). The

Base has not required that Blacks or females serve on the

panels. (Lee Dep. 82; Bass Dep. 23; Deiter Dep. 40; Tr.

Vol. Ill, 75). Ranking panels are not provided with official

training or guidelines, but are merely provided with glib,

non-specific, inexacting instructions as to how to perform

the ratings (Tr. Vol. Ill, 91; Deiter Dep. 34). The ranking

panels consideration of the performance appraisal or super

visory appraisal is totally discretionary. (Lee Dep. 68-69,

91-94, 108; Tr. Vol. Ill, 94). Yet, it is clear that the

supervisor's evaluation plays an significant role in the

selection process (Deiter, Dep. 36-38, Lee Dep. 107). As

Carl Lee, the Chief of Personnel attested, whether the panel

considers awards, training or education as a criteria and

the relative weight to be alloted these criteria is dis

9

cretionary and arbitrary. (Lee Dep. 69-71, 107).

Candidates are rated on a consensus, by the

entire panel on a scale from 0 (no value) to 4 (superior

work). R. 1018; Deiter Dep. 33). The names of those can

didates who score three or better are designated as "highly

qualified." (Lee Dep. 88, Bass Dep. 27). The names of

the first top five scorers are placed in alphabetical order

on a selection certificate which is then forwarded to the

selecting official, who makes the final selection (Lee Dep.

88; Tr. Vol. Ill, 86).

The selecting officials who are required to

interview all of the "highly qualified" candidates may

also interview other candidates on the certified list,

if they choose to do so. (Lee Dep. 99; Bass Dep. 36).

However, the interview process itself is discretionary,

non-uniform and system less. (Parcell, Tr. Vol. IV, 196)

5/ Prior to 1976, the actual numerical score of each

candidate was reflected on the certification list which was

then provided to the selecting official (Lee Dep. 26).

6/ Black employees repeatedly testified at trial that^

due to this subjective procedure Blacks who are rated "high

ly qualified" are subsequently eliminated for further con

sideration during these interviews and selection processes

which is generally conducted by Whites. (See, e .g ., Gaines,

Tr. Vol. I, 114-115; Lockett, Tr. Vol. I, 145-146; Henley,

Tr. Vol. II, 50-53; Carter, Tr. Vol. II, 218-219; Miller,

Tr. Vol. 229-230; Miller Dep. 19-21; Shepherd, Tr. Vol.

Ill, 25-26; Baylor Dep. 14-16, 18-21. Unrebutted testimony

from class members demonstrated that interviews, which

are the final determinative as to who will be selected_

for the position, are conducted by White panels or individuals.

(Gaines, Tr. Vol. I, 116-119; Richardson, Tr. Vol. I,

178-180; Henley, Tr. Vol. II, 50-53; Knighton, Tr. Vol.

II, 165-168; Bruce, Tr. Vol. II, 194; Bruce Dep. 17; Miller,

Tr. Vol. II, 224-226; Shepherd, Tr. Vol. Ill, 31-32; Hinson,

Tr. Vol. IV, 57.)

- 10

Selecting officials do not receive instructions as to how

the interview should be conducted. (Lee Dep. 91-94, 100;

Tr. Vol. Ill, 94). The Base does not provide instructions

as to the weight which should be alloted to each criteria.

(Id.) Further, there are no restrictions as to what se

lecting officials may consider. ~ Selecting officials

are not required to explain the basis of their selection

nor are they accountable for their decision. (Lee Dep.

92; Bass Dep. 37). Nor are there written records or data

memoralizing the content and scope of the interview or

selection determinaton. (Id.)

These facts demonstrate that the entire pro

motion process is subjective and infected with arbitrariness

and unbriddled discretion by White supervisory personnel.

Indeed, the Court itself recognizes that the defendant's

lack of standards governing the employment schemes is a

. , 9/problem. —

7/ For example, he can decide to confer with a candi

date's supervisor or go so far as to retrieve and consider

any supplemental data he deems relevant. (Lee Dep. Ill)•

8/ See Schlei & Grossman, Employment Discrimination

Law, (2nd ed. 1983), p. 1187 n. 5.

9/ In response to plaintiffs' concern that defendants

counsel had given the court the impression that the pro

motion process was uniformly administered the court stated:

"No, I didn't get the impression that there were any set

rules. I think that's their basic problem. (Tr. Vol.

II, 25).

11

Non-competitive or "career ladder" promotions are

also used at the Base. Pursuant to this process an employee

is placed in a particular job series that has promotional

potential and advances, without competiting for the job and

without the job being announced, after performing satisfac

torily for a specific period of time. This process con

tinues until the employee reaches the highest level in the

career ladder, at which point in order to advance further,

he must bid for a competitive promotion or seek a lateral

transfer to a position with a higher career ladder level.

(Lee Dep. 150-158; PX 3, [FPM Chap. 335]). Determinations

as to whether a position is "career ladder" and the levels

of the position are made, in large part, by supervisory per

sonnel .

5. The Governing Rules and Regulations

The Federal Personnel Manual (hereinafter re

ferred to as "FPM"), which was originally issued by the

United States Civil Service Commission in 1969, and as cur

rently maintained by the Office of Personnel Management,

establishes the employment procedures and policies governing

federal employees. The FPM which is exacting in content and

scope, requires that employment activies inclusive of all

policies, procedures programs and practices, be "job re-

12

lated." (PX 3). 10/

The Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures as issued in 1978 require that an employer per

form a job analysis and demonstrate the "validity" of any

requirement or test used in employee selection that has an

adverse impact on Blacks or any other protected class. Uni

form Guidelines §§ 14(b)(2), (d)(2), and 15(b)(3), (c)(3),

(d)(3), 43 Fed. Reg. 38290-91, 38300-07 August, 28 C.F.R.

350 14 1978). The Guidelines provide a framework for de

termining the proper use of employee selection procedures

and are "predicated on the principle that the use of a

selection procedure which has an adverse impact is unlawfully

discriminatory"; unless the procedure has been validated

job-related. FPM letter 300-25 (Dec. 29, 1978, p. 2).

10/ Merit Promotion for federal employees is governed

governed by Chapter 335 of the FPM which requires that:

An agency must adopt adequate pro

cedures to provide equal opportuni

ty in its promotion program for all

qualified employees and to insure

that nonmerit factors do not enter

into any part of the promotion pro

cess. Promotions must be made with

out discrimination for any nonmerit

reason such as race, color, religion,

sex, national origin, politics, mari

tal status, physical handicap, age,

or membership in an employee organi

zation. FPM 335, subch. 3-9(a).

13

Under the Uniform Guidelines federal agencies are required

to "maintain and have available for inspection, records or

other information which will disclose the impact which its

tests and other selection procedures have upon employment

opportunities (of minorities) . . . in order to determine

compliance with guidelines." 43 Fed. Reg. at 38297 (1978).

As the record demonstrates the Base has done

nothing to comply with the Guidelines or the Federal Per

sonnel Manual. Mr. Carl Lee, the Civilian Personnel Officer

testified that the Base has never sought the approval or

validation of its Personnel Manual which governs all of its

civilian employment practices. (Lee Dep. 190) Nor has the

Base ever revised any of its provisions to assure that they

comply with the FPM. (Lee Dep. 29; Tr. Vol. Ill, 107). ^

Mr. Lee conclusively testified that neither the promotion

system nor the components of the system have been validated

or demonstrated to be job-related. (Tr. Vol. Ill, 107,

11/ The only mandatory educational requirements for a

position are established in Handbook X-118. Any additional

qualifications are discretionarily determined by the super

visor. (Bass Dep. 20; Lee Dep. 69-70; Tr. Vol. II, 83).

However, the Base has not taken any steps to determine

whether its classification requirements beyond the basic

eligibility standards would result in an increase in the

percentage of Blacks who would meet the minimum qualifica

tions. (Lee Dep. 11-18).

14

Lee Dep. 35). In fact, no one in the Personnel Office

or the EEO office have ever taken any steps to determine

whether training, details and awards criteria and determina

tions are job-related; or are equitably and proportionately

distributed to Black employees. (Tr. Vol. 121-122; Lee Dep.

70 , 86, 113, 312, 35 , 47). — '/ The Base has not conducted

any validation studies with respect to the criteria used

for promotions, re—assignment, testing or qualifications.

Simply put, the Base has not conducted any validation

studies concerning any of the employment devices or policies

utilized at the Base in order to determine whether they

are in compliance with Title VII. (Small Dep. 21, 22,

41). Nor have the affirmative action plans ever been vali

dated or formally reviewed or approved by appropriate fed

eral authorities. (Small Dep. 74-76). Notwithstanding

the OPM requirements, no steps have been taken to collect

adverse impact data. (Tr. Vol. Ill, 95, 116).

12/ There have been no studies to establish the validity

of the factors used in the supervisory appraisal form (Lee

Dep. 72). Numerous class members who testified confirmed

that the appraisals are formulated in an arbitrary, standard

less fashion which has effectively destroyed their opportuni

ties to advance. (Proctor, Tr. Vol. II, 113-117; Harp,

Tr. Vol. II, 155-158; Fowler, Tr. Vol. II, 176-187; Carter,

Dep. 18-20; Abad, Tr. Vol. Ill, 16-17).

15

6. The Operation of The Equal Employment Opportunity

Office

Beginning in January of 1965 the Civilian Per

sonnel Office began implementing and maintaining an EEO

program, and processing EEO complaints. In 1973 the Equal

Employment Opportunity Office was established to carry out

these functions, as an entity separate from the Civilian

Personnel Office. The EEO Office and functions have always

been controlled by White males. ^

The testimonies of defendant's own officials

confirm that the Base does not provide directives regarding

14/affirmative action and equal opportunity.

By its own admission, the EEO Office has failed

to engage in any affirmative action oriented projects or

activities. (Small Dep. 36). The testimony of Small, who

has been the EEO officer through this lawsuit, convincingly

establishes that the Base has been acutely aware of problems

experienced by Black employees but have neglected to take

any affirmative steps to address these problems in accor-

13/ George C. Small, a White male, was appointed to direct

the EEO Office in 1973, and remains the sole full-time EEO

staff member. (Small Dep. 4). Small's training in the

field of equal employment is inconsequential. (Small Dep.

5) . . ,14/ Carl Lee and Mary Deiter testified that selecting

officials are not given instructions advising them to give

full consideration to minorities and females. (Lee Dep. 95;

Deiter Dep. 19). Persons employed in the Personnel Office

have never been provided EEO directives or guidelines con

cerning their obligations or responsibilities. (Deiter Dep.

25-26). As the senior staffing specialist, Mary Deiter testi

fied that contacts between the EEO Office and Personnel

officials have been minimal at best. (Deiter Dep. 26).

16

15/ Notably, in 1976dance with § 717(b) of Title VII. —

the EEO Office and dissiminated a list reflecting twenty

five specific "eeo" concerns to Base officials. (Small

Dep. 68-73). — ^ The EEO Office never conducted any follow

up studies analysis or reports with regard to the identi

fied problems. (Small Dep. 68-74) Nor has the Base formu

lated any strategies designed to address these concerns.

In fact, the EEO Office has never made any formal recommen

dations or submitted any reports with regard to the opera

tion of the Upward Mobility Program, the EEO process, the

15/ No. 5 - improperly conducted interviews for promo-

tTon/selection; No. 12 - failure to consider EEO goals when

selecting employees; No. 13 - failure to provide various

training programs; No. 19 - inconsistency in rating appli

cations under the job element rating procedures; No. 22 -

recruitment efforts do not provide qualified minorities/women

applicants to meet the organizational needs under the EEO

program."

16/ Small admitted that: (1) the classification of Blacks

in the wage grade (WG) positions as compared to the general

service (GS) positions is an egregious problem (Small Dep.

13); (2) too few Blacks are enrolled in the Upward Mobility

Program (Small Dep. 15-17); (3) Base officials recognize

that the greatest number of EEO complaints have been filed

by Black employees. (Small Dep. 26.) They are cognizant of

the fact that few of these complaints have been resolved at

the Base and admit that thev have not succeeded in es

tablishing an effective system for resolving complaints by

employees who feel they were discriminated against conceding

that "Serious and significant delays are occurring in the

processing of discrimination complaints." (PX 5); (4) the

EEO office is ineffective, in part, due to the lack of active

and genuine support from the Base. The EEO Office desperately

needs more than one full time staff person, and more per

sonnel contact with division directors, supervisors, manage

ment and employees. (Small Dep. 27-28).

17

merit promotion process or selection criteria and procedures

or career development. (Small Dep. 31, 37, 38). Small has

not communicated with the Personnel Office regarding these

issues and he candidly admitted that henever considered it

appropriate or necessary to meet Black employees. (Small

Dep. 31, 37, 38).

Personnel officials who testified at trial stated

that they were aware of the underrepresentation of Blacks in

certain jobs, and admitted that they had done nothing to

rectify the condition. (Tr. Vol. Ill 98; see also Deiter

Dep. 44. The Personnel Office admitted to the lack of ade

quate representation of Blacks at the supervisory level and

its failure to alleviate this inadequacy. (Tr. Vol. Ill,

99-100; See also Deiter Dep. 12.) Further, Personnel Di

rector Lee testified that although various efforts were made

to promote Base personnel from WG to GS in 1976 when the

Base was saturated with GS vacancies, no specific attempts

were made to advance Blacks. (Tr. Vol. Ill, 11.)

At trial plaintiffs introduced into evidence each

of the Base's affirmative action plans for the relevant

period of time. These self-incriminating reports confirm

that the Base has failed to take affirmative steps to eradi

cate racially discriminatory employment devices as mandated

18

by § 717(b) of the Act. 17/

The evidence established that there has been a

failure of the Base to effectively utilize training programs

in order to remove racial imbalances or to enhance the

career advancement of Blacks. "As a general rule when an

agency does an effective job of selecting and training

employees, it should have a pool of employees with potential

for career advancement to most positions." PX 3, Chapter

335, Subch. 3-3e(i).

Two career development programs which are in

tended to provide training and opportunities for advancement

and promotion are Upward Mobility and the Worker Trainee

17/ Defendant's affirmative action plans, reflecting the

following, demonstrate that the Base has failed to take

affirmative steps to eradicate racial disparaties as re

quired by § 717(b) of the Act: (1) Although Blacks comprise

roughly 30% of the potential labor force in the area, 60.8%

of the WG-02 employees are Black, while only 13.2% of the

WG-11 employees are Black. (PX 4); (2) Blacks constitute

15.0% of the GS-3 workforce; 10.2% of the GS-4; and 9.6% of

GS-5. However, not one of the 21 persons employed as a GS-

13 is Black (PX 4, 1)

An independently conducted census of Base employees

fortifies plaintiffs' contentions in that it shows that as

of 1976: (1) Blacks constitute 26.9% of the Base workforce,

but only 8.9% of all GS positions, while constituting 41.9%

of the ungraded workforce; (2) Blacks constitute 10.5% of

the workforce at GS levels 1 through 8, but only 5.7% of the

workforce at GS 9 through 15; and (3) Blacks hold 65.1% of

the total number of WG jobs at levels 1 through 8, but only

22.1% of all WG jobs at levels 9 through 15 (PX 27; 19, A-

2 0 ) .

19

Program. — / The Personnel Office has never recommended

that positions be designated as Upward Mobility for the

purpose of accomplishing affirmative action goals. (Lee

Dep. 13, 123, 241, Small Dep. 16, 40.) Further, the Base

has utterly failed to take advantage of its myriad of

training programs including management, executive, mid

level, clerical or technical programs, for wage grade

employees, in order to. increase the opportunities for Blacks

to advance. (Lee Dep. 234, 235, 239, 241.).

7. The Statistical Evidence

Plaintiffs introduced both descriptive and in

ferential, or analytical, statistical evidence into the

19/record. — The defendants introduced their own studies,

1 8/

18/ The Upward Mobility Program is:

... designed to provide encourage

ment, assistance and developmental

opportunities to lower-level em

ployees ... in dead-end jobs, in

order that they may have the change

in to increase opportunities for ad

vancement, improve skills, and bene

fit from training and education

through a program of individual

career development.

19/ "Descriptive" statistics reflect the actual numbers of

persons in each grade level, job category, receiving pro

motions and awards, etc. They are usually "snapshots,"

giving the picture of the workforce as of a particular date.

See EEOC v. American Nat'1 Bank, 652 F.2d 1276, 1189-1190

(4th Cir. 1981). "Inferential" statistics provide inter

pretations of the raw numbers through the application of

statistical analysis of calculations. They permit the fact

finder to draw inferences as to the meaning and significance

of the numbers. See Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299, 308, n. 14 (1977).

20

which attempted to show a lack of discrimination at the

Base. In accord with the decisions of the Supreme Court in

United States Postal Service Board of Governors v. Aikens,

___ U.S. ___, 75 L .Ed.2d 403 (1983) and Lehman v. Trout,

U.S. ___, 52 U.S.L. Week 3628 (Feb. 27, 1984), the totality

of this evidence must be considered in deciding whether

discrimination had been established.

A. Plaintiffs' Descriptive Studies

Using the litigation data base developed by the de

fendant, the plaintiffs developed a number of computer gen

erated exhibits which demonstrated the statistical profile

of the base over the time period involved as it related to a

number of issues before the court. These studies demon

strate that in both the wage board (WB) and general

schedule (GS) categories black employees were consistently

concentrated in the lower grade levels, that grade level by

grade level there was a consistent pattern of Blacks re

ceiving fewer promotions than Whites, that Blacks were at

lower grade levels even when the factors of education and

experience were taken into account, and that Blacks were

excluded from a significant number of occupational groups.

With regard to grade level, a much higher percentage

of Whites than Blacks were at GS-11 and above during the

21

relevant time period, between 12%-29% of Whites and 0-14% of

Blacks from 1972-79. (PX 7.) The pattern among wage board

employees was as pronounced, with more than 50% of Whites

but less than 20% of Blacks being at WG-10 and above in

nearly all the years examined. (PX 7.)

With regard to promotions, an examination of

promotions out of each grade level demonstrated that in the

great majority of instances a greater percentage of Whites

were promoted as compared to Blacks. (PX 5A). The result

of these patterns is that the supervisory and management

positions in both the wage board and general service

categories are dominated by Whites. Thus, by 1979 15.9% of

all White employees were supervisors, while only 5.7% of

Black employees were. While Blacks constituted 26% of

nonsupervisory employees and 35% in the Wage Leader category

(from which Wage Supervisors are drawn), they constituted

only 12% of first level supervisors, 5% of second level, and

7% of managerial level employees. (PX 18).

The net result of the employment practices at the Base

is that throughout all of the pay plans, taking into account

education and years of service, Blacks uniformly receive

19a/lower average wages or salaries than Whites. (See PX 10A).

19a/ The tables which are set out in Plaintiffs' Proposed

Finding of Fact, at pp. 1108-1114 of the record show that

Blacks of comparable years of service and education levels

to that of Whites consistently are at lower grade levels

22

B . Plaintiffs' Analytical Studies

Plaintiffs' statistical expert prepared two studies

examining the promotion rates of Blacks and Whites. The

first study was prepared from the defendants' litigation

data base. Using essentially the same data as set out in

plaintiffs' descriptive statistics, the expert calculated

the probability of the differences of percentages of Blacks

promoted, grade level by grade level, over the time period

involved. He found a consistent pattern of statistically

significant under-promption of Blacks as compared to Whites.

(Drogin Aff., R. 1414-1433).

In the analysis the proportion of Blacks promoted out

of a given grade in a given year, in a given pay plan was

compared with the proportion of Blacks in that grade at the

end of the prior year. — / The statistical significance of

the difference between the number of Blacks expected to be

promoted and those actually promoted was calculated

by a formula for the 1-sample binomial test endorsed in

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299

19a/ Continued

and consequently receive lower salaries. PX 10-10B.

20/ Only full time permanent employees were included in

the calculations. A promotion was defined as a change in

position, either by pay plan or grade or series, for which

there was an increase in salary and for which the new po

sition was full time permanent. (R. 1416)

23

(1977) and Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Service,

699 F .2d 760 (5th Cir. 1983). (R. 1416).

The results for Black WG employees, set out in

detail at p. 1423 of the record, were summarized by the

expert as follows:

1. Blacks received fewer promo

tions than expected in all grades, except WG-10

and WG-12. Blacks lost 10.4 promotions out of

WG-2, 46.4 promotions out of WG-5, 7.0 promo

tions out of WG-7, and 19.8 promotions out of

WG-8.

2. For WG as a whole, blacks re

ceived fewer promotions than expected in each

year during 1973-1979.

3. Over all grades, and all years

from 1973-1979, blacks received 90.7 fewer pro

motions out of WG grades than expected. The

corresponding Z-VALUE for this disparity is

-7.8, which would occur by chance with proba

bility less than .00000000000001577. Accor

dingly, there is a very high level statistical-

significance in the disparity of promotions

actually received by blacks compared to the ex

pected promotions to blacks, if promotions were

distributed at parity.

(R. 1418).

With regard to promotions out of GS positions,

which were held by a far lower proportion of Blacks than

24

were WG ones, — the same analysis was performed. (R.

1418-19.) Because of the smaller numbers the results were

less dramatic, but still showed a statistically significant

under promotion of Blacks, as summarized by the expert:

1. Blacks received 17.5 promotions

fewer than expected out of GS-2 over the period

from 1973-1979. This disparity has a Z-VALUE of

-3.96, which would occur by chance with proba

bility less than .0002, and is highly statis

tically significant.

2. When disparities for each grade

and year are accumulated, blacks received 23.1

fewer promotions out of grade than would be ex

pected if promotions were received by blacks at

the same rate as their representation in the

grade. This disparity has a Z-VALUE of -2.0,

indicating a significance probability of about

.05. This result has statistical significance.

(R. 1418-19).

2 1/

In addition to these studies, which were essen

tially based on a labor force analysis, plaintiffs' expert

also examined actual applicant flow data to determine

whether the expected number of Blacks received competitive

21/ In 1979 only 20% of the Black workers held GS po

sitions, while 2/3 of the white employees did. (PX 18.)

25

promotions to GS positions compared with those applying for

such promotions. Information was obtained from the Base's

vacancy announcement files from which the names of persons

applying for each particular vacancy were available, and

race data was coded in from the defendants' litigation data

base with the result that the great majority of those per

sons applying for competitive positions were identifiable as

to their race. The method used by plaintiffs' expert,

contrary to the finding by the district court, was to ex

amine each vacancy announcement separately. — ^ In this way

it was possible to eliminate from consideration those

vacancies where there was no competition between Blacks and

Whites and to avoid distortions in the data that would be

occasioned by a large number of applications for particular

positions.

As described above, the competitive promotion pro

cess at the Base has, in common with other federal agencies,

23/three stages.— At the first stage persons interested in a

job fill out a standard form on which they list their

22/ See R. 1419 ("The promotional opportunity data was

analyzed separately for each announcement, and then the

disparities were accumulated over announcements to obtain an

overall measure of disparity."); and R. 1461 ("I did do the

competitive promotion analysis on an announcement by

announcement basis".)

23/ See Lawler v. Alexander, 698 F.2d 439 (11th Cir. 1963).

26

qualifications. These forms are then reviewed by the per

sonnel office to determine those persons who have the alleged

minimum qualifications for the position. Those persons

having the minimum qualifications, all of whom are ranked

"qualified", then proceed to the second stage in the process.

In this stage each person is given points based on

factors such as education, experience, training, awards, and

performance appraisals. Those persons above a particular

point level are ranked "highly qualified." The names of the

Qualified and Highly Qualified are placed on a list in

alphabetical order.

In the third and last stage of the process the

selecting official selects, at his discretion, anyone of the

persons on the list. In this process the selecting official

may interview the person, and review personnel files and

other data available through the personnel office.

Plaintiffs' expert determined the relative rates at

which Blacks and Whites were screened out by this process

and ultimately the rate at which Blacks were selected as

opposed to Whites. As noted above, this was done

24/ As described by the expert:

For each vacancy announcement, and for each year, the race

composition for each of the following groups was tabulated:

All Applicants

Qualified

Highly Qualified

27

separately for each vacancy announcement, and the results

for each were, through an established statistical pro

cedure, accumulated to determine the effect of each stage

of the process and the effect of the process as a whole.

There was a consistent pattern of Blacks being under

selected at each stage of the process, usually at statistically

significant levels. Thus, Blacks were found not qualified

at a higher rate than were Whites, and Blacks found to be

24/ (Continued)

Interviewed

Selected

Selected and Qualified

Selected and Highly Qualified

In order to evaluate the impact on blacks at each stage of

the Merit promotion process several comparisons were made:

Black and white rates of

Qualified + Highly

Qualified among All Applicants

Black and white rates of

Highly Qualified among Qualified and

Highly Qualified

Black and White rates of

Selected among Qualified

Qualified

and Highly

Black and white rates of

Selected among Highly Qualified

Black and white rates of

Selected among All Applicants

(R. 1416-17.)

28

qualified were not determined to be highly qualified at the

2 5/same rates as were Whites. — /Blacks found highly qualified

were not selected from the lists at the same rates as were

Whites. — ^

Plaintiffs' study, which again used actual appli

cant flow data, established that the impact of the system

for making competitive selections was consistenlty to under

select Blacks at statistically significant rates. Thus,

the underselection of Blacks from all Black applicants

was at the level of 4.32 standard deviations, with under-

2 7/selections at every GS-level except GS-10 (R. 1421).— '

25/ R. 1419. At all grades but three fewer black applicants

were found qualified and highly qualified than expected,

with an overall loss of nearly 48 promotions. This was

statistically significant at the level of 4.72 standard

deviation, with a probability of less than 7 chances in

one million.

There was a similar under representation of Blacks

from the Qualified pool; 19 fewer Blacks were so rated

than expected, at a level of 2.64 standard deviations (R.

1420 . )

26/ Blacks were underselected from among the Qualified/

Highly qualified pool at a level of 2.47 standard deviations.

(R. 1421).

27/ There were too few promotions to GS-14 and GS-15 posi

tions to permit their study.

29

Defendant produced no explanation for these results

except speculative ones unsupported by any evidence. Thus,

it is clear that absolutely nothing had been done to validate

the qualifications or selection procedures used, or to

in any way demonstrate that they in fact were accurate

or necessary measures of individuals' abilities to do the

jobs in question. — '/ Indeed, their own expert advanced as

an explanation for the underselection of Blacks the fact

that Blacks were known to have lower educational levels than

were Whites. Therefore, they would be found to be less

qualified because of their failure to meet educational

requirements. 2_9/ no showing was made that the

educational requirements that existed were job related or

had been validated in any way.

C. The Defendant's Statistical Studies

In his case the defendant put on studies de

veloped by two statistical experts. The first essentially

compared persons in particular types of positions with their

representation in various labor markets. Thus, the study

was more relevant to the question of initial hires than to

promotions, the main focus of plaintiffs' case.

The second expert studied promotions specifica

lly, and, in fact, developed two studies. The first a

28/ See Tr. Vol. Ill, 107; Lee Dep. 35, 44, 47, 70-72,

86, 133, 190.

29/ R. 1408, Affidavit of Charles T. Kenny.

30

so-called "naive" study, was fully consistent with plain

tiffs' study and demonstrated a general underselection of

Blacks for promotions at the Base. This "naive" study,

which was revealed only during the cross-examination at

trial, was followed by an attempt to construct a regression

analysis which would explain the different rates in pro

motions based on differences in a number of factors. These

factors included levels of education (not education related

to the job in question); the length of experience in years;

veterans preference; and others. — ^

30/ See Court Exhibit II. For example, Table 1.4 at p. 13

of the report cumulates the deviations from expected Black

promotions over the period 1973 to 1979 by various groups of

grades. In six out of the nine groupings there was an

underselection of Blacks, and four of these were at sta

tistically significant levels. Overall, the study shows

that 75 fewer Blacks were promoted than would be expected

(437.949 expected - 363 actual). Applying the Hazlewood-

Peques formula, where the numbers are:

Total promotions = 2111

Percent Blacks expected = 17%

Percent White Expected = 83%

Actual Blacks promoted = 363,

the result is 4.342 standard deviations.

31/ See DX 25.

31

Using these factors, which explained a fairly low

proportion of the reasons for the differences in promo

tions, the expert purported to conclude that there was no

discrimination against Blacks in promotions. During his

examination the expert acknowledged that his selection of

the various factors used was not based on a particularized

3 2/study of the federal personnel system, — but rather was

based on his understanding of how personnel systems worked

generally. — ^ Thus, for example, veterans preference is

not in fact used in the competitive promotion process, but

only when persons are initially hired into the federal

system. — ^His educational levels simply looked at years of

education and not types of education to match up the

35/education specifically related to the jobs m question. —

His experience factor was years of service, — 7 even though

under the federal personnel system years of service (or

seniority) is not used to determine competitive promotions

unless there is a tie between candidates. Rather, only that

experience which is purportedly related to the position in

question is considered. See Federal Personnel Manual Chap.

335 (PX 3) •

32/ Tr. Vol.• IV, pp

33/ Id. , P- 13-14.

34/ Id. , pp.. 7-9.

35/ Id. , pp.. 16-17.

36/ Id. , P- 18.

32

Finally, the expert acknowledged that he did not

factor in two elements which were used in the selection

process, namely awards and performance appraisals. His

reason for not utilizing those factors was that because they

were subjective in nature they could be attacked as

discriminatory. — ^ In any event the bottom line of the

study was that differences in promotions might be explained

by the level of education attained by Blacks and Whites and

to some degree by their length of federal service.

9. The Testimonal Evidence

During the trial twenty six members of the class

representing both the Wage Grade (WG) and General Schedule

38/(GS) classifications presented illuminating testimony. —

In addition, depositions were introduced on behalf of four

other class members. This testimony, which was unrebutted

by the defendant, fortifies plaintiffs' statistical and

documentary proof. The majority of the class members testi

fied that they had been denied opportunities to advance

irrespective of their demonstrated abilities and potential

capabilities. The testimony of several members of the class

evidences that Black were denied supervisory positions

37/ Tr. Vol. Ill, 221; Vol. IV, 18.

38/ Due to space limitations plaintiffs cannot present an

exhaustive analysis of their testimony. Therefore, we refer

the Court to Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact, pp. 53-

74 .

33

despite thee fact that they possessed superior qualifications.

Others who testified proved that they were not afforded

employment opportunities assignments, or training which was

provided to similarly situated Whites. Finally, plaintiffs'

testimonial proof confirmed that the equal employment

opportunity office and complaint processing system is

ineffectual.

In fact, the court below expressly found that

twelve of the class members who testified at trial "were

persuasive on the issue of discrimination in the promotion

process." (R. 53)

C . Standard of Review

1. With regard to Argument I, the district

court erred as a matter of law; in addition, some of its

factual findings were clearly erroneous.

2. With regard to Argument II, the district court

erred as a matter of law.

3. With regard to Argument III, the district

court erred as a matter of law.

Summary of Argument

I.

The statistical evidence presented by both parties

clearly establishes a pattern of discrimination against

Blacks in promotions. Blacks are concentrated at the lower

grade levels and are underrepresented in supervisory and

managerial positions. Studies of competitive promotions

established that Blacks were underselected at each stage in

34

the process, with the result that they received far fewer

promotions than would be expected in a race-neutral system.

The defendant failed to present any evidence that would

support a finding that the differences in promotion were the

result of non-discriminatory factors. Defendant's failure to

validate any of its selection procedures violated the

requirements of Title VII.

II.

Section 717(b) of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act requires that federal agencies establish effective

affirmative action programs. Congress enacted the pro

visions because of the concentration of Blades and other

minorities in lower grade levels. Precisely the same

pattern was shown in the present case. Therefore, the

district court was required to order the defendant to

establish and carry out an effective affirmative action

program.

III.

The Court's failure to order relief for class

members who demonstrated discrimination was error. The case

should be remanded for reconsideration of the individual

claims in light of classwide discrimination.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction of this Court is based on 28 U.S.C. §

1291, this being an appeal from the final decision of the

court below dismissing the action.

35

ARGUMENT

I.

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN HOLDING THAT THE STATISTICAL

EVIDENCE DID NOT ESTABLISH DISCRIMINATION

We have set out at length in the statement of facts

the statistical evidence before the trial court relating to

the claims of discrimination. The district court made

errors of both law and fact in assessing this evidence, and

these errors require the reversal of its decision.

A. The Appropriate Comparison for Wage Board

Promotions Was The Internal Workforce.

A long line of decisions have established that when

promotions are predominantly from within an employer's work

force, then the appropriate comparison to be made is whether

those persons holding positions in the upper levels reflect

the proportion of persons in the workforce as a whole. — ^

The district court thus erred in assessing plaintiffs' des

criptive statistics as they related to promotions to higher

level wage board positions, as well as the statistical

analysis presented by their expert.

39/ Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1979); Payne

v. Travenol Laboratories, 673 F.2d 798, 826-27 (5th Cir.

1982); Johnson v. Uncle Ben's Inc., 628 F.2d 419, 425 (5th

Cir. 1980); Carroll v. Sears Roebuck Co., 708 F.2d 183, 193

(5th Cir. 1983).

36

Both studies compared those persons in each par

ticular grade level at the Base to assess whether the pro

portion of Black and White employees promoted was different.

The statistics demonstrated beyond question, and the defen

dants' experts admitted, that there was statistically sig

nificant differences in the rates of promotions of Blacks

and Whites grade level by grade level over the time period

involved in this case. The ultimate result of this pattern

was that Blacks were severely underrepresented in the higher

level supervisory and management positions at the Base both

in the wage grade and categories.

Once such a showing had been made the burden was on

the defendants to come forward with evidence, not speculative

reasons, as to why these differences existed. Payne v.

Travenol Laboratories, supra; Carroll v. Sears Roebuck, supra

see also Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094, 1102 (D.C.

Cir. 19 83 ), rev1d on another ground, ___U.S. ___, 52 U.S.L.

Week 3628 (Feb. 27, 1984). The defendants, however, failed

to do so. Rather, they and their experts simply presented

possible reasons why the difference could have existed, such

as Blacks were less qualified than Whites, Blacks did not

apply for positions, etc. Such speculations cannot substi

tute for the proof which a defendant employer and would be in

the best position to produce since it is in its possession.

Indeed, it is clear from the affidavits of defendants'

experts which were relied upon by the court below that they

completely misconstrued the relative burdens of proof in a

37

Title VII case. They evidently believed that the burden was

on plaintiffs to disprove every possible alternative

explanation for differences between Blacks and Whites in

order to make out a case of racial discrimination. Such a

position completely misconstrues the purpose and history of

Title VII.

When Congress passed the Equal Employment Opportun

ity Act of 1972 it recognized that the issue of employment

discrimination was more complex, far reaching, and entrenched

than had been perceived in 1964:

In 1964, employment discrimination tended

to be viewed as a series of isolated and dis

tinguishable events, for the most part due to

ill-will on the part of some identifiable indi

vidual or organization . . . Experience has

shown this view to be false.

Employment discrimination as viewed today

is far more complex and pervasive phenomenon.

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1971) p. 5.

With regard to agencies of the federal government

Congress found in the concentration of Blacks in the lower

grade levels evidence both of employment discrimination and

of the failure of existing programs to bring about equal

40/employment opportunity. — ' The present case presents the

t--------------------------------

40/ the House Report stated:

Statistical evidence shows that minorities and

38

same pattern that led Congress to extend Title VII to

federal agencies; Blacks are largely relegated to lower

positions, regardless of their qualifications and capa

bilities

propostion that in an employment system that is fair and

neutral with regard to race, one would expect to see persons

receiving employment benefits on an equal basis irrespec

tive of their race. Thus, if the issue is hiring, one

would expect to see a workforce reflective of the workforce

from which employees are hired. Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324, 339 n. 20 (1977). If the issue is internal

promotions one would expect over a period of time to see

Blacks distributed fairly through the workforce. Davis

v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957, 963-64 (D.C. Cir. 1980). Indeed,

40/ Continued

women continue to be excluded from large numbers of

government jobs, particularly at the higher govern

ment levels ....

This disproportionate distribution of minorities

and women throughout the Federal bureaucracy and their

exclusion from higher level policy-making and super

visory positions indicates the government's failure to

pursue its policy of equal opportunity.

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1971), p. 23. the

Senate report also included statistics which showed the

itle VII, of course, is based on the fundamental

it was this expectation and its disappointment that led

Congress to conclude that minority federal employees suf

fered from employment discrimination and that corrective

- ̂ 41/action was neeaed. —

The burden on plaintiffs in a Title VII action is

not, and never has been, to disprove every conceivable ex

planation for a maldistribution of Blacks in the workforce,

but to show patterns which demonstrate that the underlying

presumptions of Title VII are not met. Blacks are dispro

portionately in lower grades; they advance at slower rates;

fewer are promoted and they are underrepresented in super

visory and managerial positions. ——^ Upon such a showing,

the burden shifts to the defendant employer to come forward

with legally sufficient reasons for these disparities, mal

distributions, and inequities. An employer cannot simply

40/ Continued

concentration of minorities in the lower grade levels, and

concluded that this indicated that their ability to advance

to the higher grade levels had been restricted. S. Rep. No.

92-415 (92nd Cong., 1st Sess.) pp. 13-14.

41/ See S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra, pp. 5-6.

42/ See Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 299,

307 (1977); Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 336-

338 (1977); Barnett v. W. T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543, 549

(4th Cir. 1975); Seqar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp. 690 (D.D.C.

1981); Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007, 1018

(2nd Cir. 1980 ) .

40

sit back and demand that the plaintiffs counter every specu-

43/lative explanation that may be invented by a fertile mind.—

In sum, the thrust of Title VII is to provide an

effective remedy to correct the historical denial to Blacks

of equal opportunity and a fair share of employment benefits.

It is a remedial statute and must be construed and applied in

light of the problems it was passed to address and correct.

The statistical evidence in this case establishes a consistent

pattern of discrimination and disparate treatment of Black

employees at the Marine Supply Base which requires the con

clusion that Title VII has been violated.

43/ As one Court has put it:

When a plaintiff submits accurate statistical data,

and a defendant alleges that relevant variables are

excluded defendant may not rely on hypothesis to

lessen the probative value of plaintiff's statistical

proof. Rather, defendant in his rebuttal presentation,

must either rework plaintiff's statistics incorpora

ting the omitted factors or present other proof under

mining plaintiffs' claims.

Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp. 690, 712 (D.D.C. 1981),

citing Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d at 964. See Hazelwood

School District v. United States, supra; Teamsters v. United

States, supra; Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007,

1015 (2nd Cir. 1980); Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment

Service, 699 F.2d 760, 769 (5th Cir. 1983); EEOC v. American

41

B. Plaintiffs' Promotion Study Demonstrated

Discrimination.

The court below made a number of factual and legal

errors in assessing plaintiffs' study of actual promotion

actions. First, it is clear from the record, as attested to

by two affidavits from plaintiffs' expert, that he in fact

examined each promotion action separately and then accumula

ted the results over the entire time period. See n.22, supra.

Thus, the finding of the district court that he did not do so

44/is clearly erroneous. —

Plaintiffs' expert began with data on each promotion

action individually. For example, for vacancy #1, ten Blacks

and 20 Whites may have applied and a White selected; for

vacancy #2, 5 Blacks and 2 Whites applied, and a White was

selected, and so on. The expert calculated the probability

of each event occurring by chance, and then totalled the

43/ Continued

National Bank, 652 F.2d 1176, 1186-89 (4th Cir. 1981).

44/ The court's error apparently derived from the bald asser

tion of defendants' expert that plaintiffs' expert looked at

all the promotion actions as a group. (R. p. 1387.) This

assertion, however, was based on no evidence, and, indeed,

the defendants' expert Dr. Upton in his affidavit admitted

that he had not verified "the data or calculations" that

formed the bases of plaintiffs' expert's conclusions. (R.

1384.) Therefore, plaintiffs' expert's statement that he in

fact looked at each promotion action separately is uncontroverted.

42

results over all the actions.

Second, the district court erred in its analysis of

the promotion process. See Lawler v. Alexander, 698 F.2d 439

(11th Cir. 1983). Plaintiffs' statistics clearly demonstrated

that Blacks were unfavorably treated at each stage of the

process at the Base; moreover, their disproportionate

under-selection at each stage was at levels of statistical

significance. The ultimate result of the process was that

Blacks were weeded out at a much higher rate than were

Whites.

Defendant's experts did not challenge the accuracy

of the statistical analysis; rather, criticisms were made on

a series of assumptions with no basis in either the record or

in the law. First, it was assumed that the system for

establishing the qualification of applicants was valid, and

therefore the defendant accurately assessed that those per

sons found qualified and highly qualified indeed had the

45/skills necessary to accomplish the job in question. —

Specifically, one of defendants' expert noted that the edu

cation requirements would weed out a greater number of Blacks

than Whites since it was "well known" that Blacks as a whole

46/had lower levels of education than did Whites. —

45/ R. 1383-85 (Aff. of Dr. Upton).

46/ R. 1408 (Aff. of Dr. Kenney)

43

However, such a result itself establishes a violation of

Title VII since the Supreme Court, has held that the use of

an educational standard which has an adverse impact on Blacks

violates Title VII in the absence of a demonstration that it

is job related. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971). Of course, the record here establishes beyond

question that absolutely no attempt has been made by the

defendant to validate or otherwise establish that the

education or any other requirements used to determine the

qualifications for the various jobs in question are actually

related to the ability to perform the jobs. See Harrison v.

Lewis, 559 F. Supp. 943, 948-50 (D.D.C. 1983), aff1d per

curiam, ___ F.2d ___ (D.C. Cir. Mar. 1, 1984).

With regard to the qualified/highly qualified stage^.of

the process, it is clear that all persons reaching that point

have the minimum qualifications for the job, even assuming

that the qualifications are valid. Thus, the high rate of

exclusion of Blacks at this stage necessarily calls for an

explanation by the employer.

The defendant's expert tried to explain this

showing away by an argument which totally contradicts the

position taken by the defendant with regard to the first

stage of the process. He speculated that the employer

erroneously found persons to be highly qualified or quali

fied, and that the mistaken qualification of more Blacks

4 7/than Whites could explain the statistical showing. —

47/ R. 1389-90 (Upton Aff.).

44

Of course, defendant put in no evidence whatsoever to

demonstrate either that anyone was erroneously classified, or