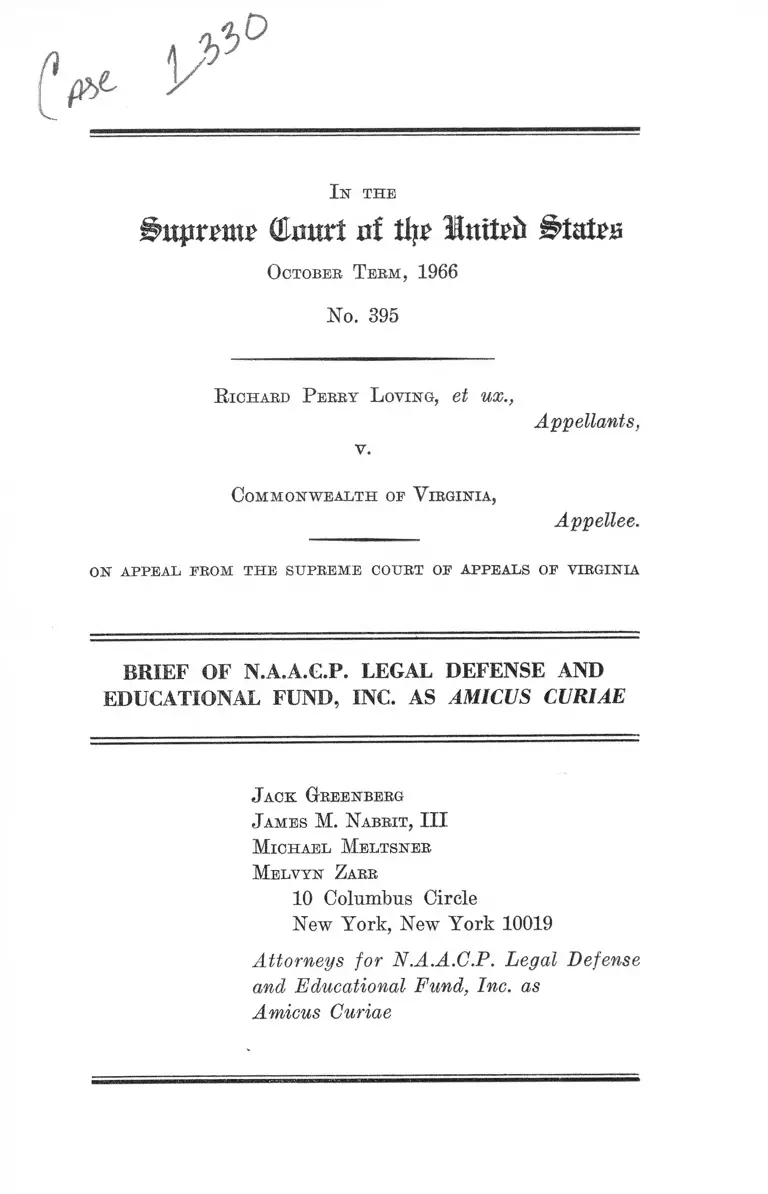

Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia Brief Amicus Curiae, 1966. 228658ce-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16c09567-9df6-4800-a327-b509ec8a4a6b/loving-v-commonwealth-of-virginia-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

1 st t h e

Supreme (Emurt nf tip lu tt^ States

O ctober T erm , 1966

No. 395

R ichard P erry L oving, et ux.,

Appellants,

v.

Co m m on w ealth oe V irginia ,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF OF N.A.A.G.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

M ichael M eltsner

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. as

Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of the Amicus Curiae.................................. 1

Argument .................... 3

Conclusion ........... 15

A ppendix I .................................................................. 17

A ppendix II .................. 19

Table op Cases

Abernathy v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 447 ........................... 2

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 ..... 7

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 .................................. 2, 6

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 41 ....................................... 2,6

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 ......................... 2

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 .................................. 6

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 ........................................ 2

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 ..................................... 6

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 ........ .............. 2

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 .................................. 2

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 .... .................... 2, 6

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ...........2, 6,14

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U.S. 60 .................................. 6

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 ..................................................................................... 6

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 .................................. 2

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 .......................................... 2, 6

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 ................... 2

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 ..................................... . 2, 6

PAGE

11

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202 ........................................ 6

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 4 4 ............................ 2

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 .................................. 2

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 ...................................... 2, 6

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 ..................................... 2

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 565 .............................. 7

Gober v. City of Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374 ................. 2

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 ............................. 9

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 ................... 2, 6

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 ........................... 9

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 .............................. 2

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 .................................. 2

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U.S. 668 .................................. . 6

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776 .................................. 2

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 .................................... 2, 6

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 .................................. 6

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 ................... 6

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 .............................. 6

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U.S. 877 ........................................................................... 2,6

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 .......................... 2,4,5

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 .................................. 9

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U.S. 971 6

Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E.2d 749 (1955), judg.

vacated, 350 U.S. 891 (1955), judg. reinstated, 197

Va. 734, 90 S.E.2d 849 (1956), motion to recall

mandate denied, 350 U.S. 985 (1956) ....................... 3,4

PAGE

I ll

Naim y. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E.2d 749 ...................9,14

New Orleans City Park Improvement Asso. v. Detiege,

' 358 U.S. 5 4 ......... ....... .............. ............................ ........... 6

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 .... ................... ........... . 4

Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal.2d 711, 198 P.2d 17 (1948) .... 11

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 ............... 2, 6

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 .................................. 4

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 .......................................... 2

Scott v. Georgia, 39 Ga. 321 (1869) .............................. 10

Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. (60 U.S. ) 393 ....................... 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .................. ...................... 6

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 ........ ....... ....... .......... 9

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 ............. 7

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 .................................... 6

State v. Jackson, 80 Mo. 175 (1883) ............................... 10

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533 .... 2, 6

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U.S. 192 ..... ......... 6

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 ....................... 6, 7

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 ............................... 2, 6

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 .................................. 2,6

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 ...................................... 2,6

Statutes Involved:

Va. Code Section 20-54 ..................................................... 3

Va. Code Section 20-57 ...................... .... .......................... 3

Va. Code Section 20-58 ......... ............................................. 3 ?4

Va. Code Section 20-59 ......................... ............................. 3

Va. Code Section 20-60 ...................... ............................... 3

PAGE

IV

Other Authorities:

Beals and Hoijer, An Introduction to Anthropology

(1953) .............. 11

Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions,

69 Yale L. J. 421 (1960) ......... ....................................... 8

Dobzhansky, “ The Race Concept in Biology,” The

Scientific Monthly, LII (Feb. 1941) .......................... 10

Hankins, The Racial Basis of Civilisation (1926) ....... 11

Kroeber, Anthropology (1948) ....................................... 12

Montague, An Introduction to Physical Anthropology

(1951) ........... 12

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy

of Race (4th ed. 1964) ............................................10,11,12

Murray, States’ Laws on Race and Color (1951) ........... 14

Note, 58 Yale L. J. 472 (1949) ............. ............. ............. 11

UNESCO, “ Statement on the Nature of Race and Race

Differences—by Physical Anthropologists and Ge

neticists, September 1952.” .................. ......................... 11

Weinberger, “A Reappraisal of the Constitutionality

of Miscegenation Statutes,” 42 Cornell L. Q. 208 .... 10

Yerkes, “Psychological examining in the U. S. Army,”

15 Mem. Nat. Acad. Sci. (1921) .................................. 12

PAGE

In the

(Emtrt nf tljiv Tl&mttb States

O ctober T erm , 1966

No. 395

R ichard P erry L oving, et ux.,

v.

Appellants,

Com m on w ealth oe V irginia ,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL PROM THE SUPREME COURT OE APPEALS OE VIRGINIA

BRIEF OF N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of the Amicus Curiae

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a non-profit membership corporation, incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York in 1940. It was

formed to assist Negroes to secure their constitutional

rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares

that its purposes include rendering legal aid gratuitously

to Negroes suffering injustice by reason of race or color

who are unable, on account of poverty, to employ and

engage legal aid on their own behalf. The charter was

approved by a New York court, authorizing the organiza

tion to serve as a legal aid society. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is independent of

other organizations and is supported by contributions of

funds from the public.

2

The Fund has litigated a great many cases involving

the civil rights of Negroes which have sought to eliminate

racial segregation and discrimination.1 One of those cases

was McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, a case wThich,

as we shall submit below, has an important bearing on

the present litigation. The Fund consistent with its op

position to all forms of racial discrimination supports

appellants’ arguments that Virginia’s laws punishing inter

racial marriage violate the Constitution. The parties have

consented to the filing of an amicus curiae brief by the

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and

copies of their letters of consent will be submitted to the

Clerk with this brief.

1 Some of the cases in which the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc. has opposed racial discrimination in recent years are

eases involving schools (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483;

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1; Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683;

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103; Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198);

public parks (Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S.

877; Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284;

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526; Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296);

voting (Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399); transportation facilities

(Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454;

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 41; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350; Aber

nathy v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 447); restaurants (Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U.S. 157; Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244; Gober v. City

of Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374; Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226; Bouie v.

City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347; Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146;

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306; Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780);

the right of peaceable assembly (Edioards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S.

229; Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 44; Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S.

776); jury discrimination (Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129); dis

criminatory treatment of a witness (Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650),

and athletic contests (State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533).

3

Argument

Appellants were convicted of violating Virginia Code

Section 20-58, and Virginia’s highest court has rejected

their objections that the statute violates their rights under

the Constitution of the United States. Section 20-58 is one

of several Virginia laws which prohibit marriages between

white persons and colored persons.2 It provides:

§20-58. Leaving State to evade law.—If any white

person and colored person shall go out of this State,

for the purpose of being married, and with the inten

tion of returning, and be married out of it, and after

wards return to and reside in it, cohabiting as man

and wife, they shall be punished as provided in §20-59,

and the marriage shall be governed by the same law

as if it had been solemnized in this State. The fact

of their cohabitation here as man and wife shall be

evidence of their marriage.

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, in the opinion

below, found “no sound judicial reason” (E. 25), to depart

from its prior decision upholding the law forbidding inter

racial marriage against a federal constitutional challenge.

Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E,2d 749 (1955), judg.

vacated, 350 U.S. 891 (1955), judg. reinstated, 197 Va.

734, 90 S.E.2d 849 (1956), motion to recall mandate denied,

350 U.S. 985 (1956) (case “devoid of a properly presented

federal question” ). In Naim v. Naim, supra, the Virginia

court said that the purpose of the state’s laws against

2Va. Code §20-54 prohibits interracial marriage in the State. Section

20-57 provides that marriages between white and colored persons are

“ absolutely void without any decree of divorce or other legal process.”

Section 20-59 makes inter-marriage a felony punishable by confinement

in the penitentiary for not less than one nor more than five years. Section

20-60 provides that any person performing a marriage ceremony between

a white person and a colored person shall forfeit two hundred dollars.

4

intermarriage was “to preserve the racial integrity of its

citizens” and so that the state “ shall not have a mongrel

breed of citizens” (87 S.E.2d at 756), and that: “I f preser

vation of racial integrity is legal, then racial classification

to effect that end is not presumed to be arbitrary” (87

S.E.2d at 755). Appellants argued in the courts below

that Naim v. Naim, supra, should not be followed because

it was based upon precedents—particularly Plessy v. Fer

guson, 163 U.S. 537, and Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583—

which had been overruled. The court below rejected these

arguments, and asserted that McLaughlin v. Florida, 379

U.S. 184, which appellants relied on, “detracted not one

bit from the position asserted in the Naim opinion” (R. 24).

The court thought that none of the many decisions in

validating racial laws under the Fourteenth Amendment3

required invalidation of the law punishing interracial mar

riage because of “an overriding state interest in the insti

tution of marriage” (R. 24). We submit that the laws

forbidding and punishing marriages between white persons

and Negroes violate the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

Virginia Code §20-58, on its face and as applied in this

case, makes a person’s race the test of whether his conduct

is criminal. No penalty is provided for persons of the

same race who engage in the conduct mentioned in the

section—i.e., leaving the state for the purpose of being

married, with the intention of returning, being married

out of the state, and afterwards returning to and residing

in the state cohabiting as man and wife. The essence of

the law is racial, and race is the test of criminality. It is

obvious, and doubtless would be conceded by the State,

3 See, e.g., cases collected in note 1, supra, and see text infra, p. 6.

5

that appellants’ conduct would be entirely lawful under

Virginia law had they both been white, or both Negroes.

We urge that the issue of the invalidity of this law may

be disposed of on this ground and without reference to

other possible formulations of the issue. As Mr. Justice

Stewart, joined by Mr. Justice Douglas, wrote concurring

in McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 185, 198:

. . . I cannot conceive of a valid legislative purpose

under our Constitution for a state law which makes

the color of a person’s skin the test of whether his

conduct is a criminal offense. * # # And I think it is

simply not possible for a state law to be valid under

our Constitution which makes the criminality of an

act depend upon the race of the actor. Discrimination

of that kind is invidious per se.

In McLaughlin, supra, the opinion of the Court, by Mr.

Justice White, invalidated Florida’s interracial cohabita

tion law “without reaching the question of the validity of

the State’s prohibition against interracial marriage” (379

U.S. at 195). The opinion of the Court in McLaughlin,

supra, said that the Florida law was invalid “Because the

section applies only to a white person and a Negro who

commit the specified acts and because no couple other than

one made up of a white and a Negro is subject to con

viction upon proof of the elements comprising the offense

it proscribes . . .” (379 U.S. at 184). The opinion said

also that this racial classification “must be viewed in light

of the historical fact that the central purpose of the Four

teenth Amendment was to eliminate racial discrimination

emanating from official sources in the States.” 379 U.S.

at 192. The Court then inquired whether there was any

statutory purpose which might justify the classification;

found that there was none; and held the law invalid under

the Equal Protection Clause.

6

We urge that racially discriminatory state laws are no

longer only “constitutionally suspect” (Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U.8. 497, 499) and merely subject to “rigid scrutiny”

(.Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.8. 214, 216). The

decisions which have invalidated every state segregation

law or practice to come before this Court establish that

there can be no justification for such laws and that they

are all invalid per se. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60; Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U.S. 668; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649; Steele v.

Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U.S. 192, 203; Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249;

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483; Muir v.

Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U.S. 971; Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877;

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879; Gayle v. Browder, 352

U.S. 903; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1; New Orleans City

Park Improv. Asso. v. Detiege, 358 U.S. 54; Evers v.

Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202; State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey,

359 U.S. 533; Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U.S. 715; Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 41; Turner

v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350; Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S.

61; Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244; Lombard

v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S.

284; Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526; Goss v. Board

of Education, 373 U.S. 683; Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S.

399; Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103; Evans v.

Newton, 382 U.S. 296. We think the teaching of these

cases, viewed against their varied circumstances and against

the multitude of supposed justifications for segregation

which have been offered and rejected, is simply that

the Equal Procetion Clause strikes down all forms of

racial segregation laws. It is beyond the power of the

state to compel segregation whatever the context and what

ever the asserted justification. As Mr. Justice Stewart

7

wrote in 1963, “ . . . our Constitution presupposes that

men are created equal, and that therefore racial differences

cannot provide a valid basis for governmental action.”

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 317

(dissenting opinion).

Most especially in the area of criminal justice must the

law be administered “ without reference to consideration

based on race.” Cf. Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 565,

591. To send a person to prison because of the color of

his skin would make a mockery of the constitutional promise

of equal protection of the laws. The Fourteenth Amend

ment overrides any State choice to inflict penal sanctions

based on race or color. Such a choice is simply denied

to the States. The “pervading purpose” of the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments was to protect Ne

groes against discrimination. The Slaughterhouse Gases,

83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36, 71. The Fourteenth Amendment

was adopted to declare “ . . . that the law in the States

shall be the same for the black as for the white; that all

persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal before

the laws of the States and, in regard to the colored race,

for whose protection the Amendment was primarily de

signed, that no discrimination shall be made against them

by law because of their color.” Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303, 307.

Professor Charles L. Black, Jr. has cogently stated that

the application of the Equal Protection Clause to cases

of racial discrimination calls for no inquiry about whether

such discriminations are “reasonable.” Professor Black

wrote:

But the whole tragic background of the fourteenth

amendment forbids the feedback infection of its central

purpose with the necessary qualifications that have

attached themselves to its broader and so largely acci

8

dental radiations. It may have been intended that

“ equal protection” go forth into wider fields than the

racial. But history puts it entirely out of doubt that

the chief and all-dominating- purpose was to ensure

equal protection for the Negro. And this intent can

hardly be given the self-defeating qualification that

necessity has written on equal protection as applied

to carbonic gas. If it is, then “ equal protection” for

the Negro means “equality until a tenable reason for

inequality is proferred.” On this view, Negroes may

hold property, sign wills, marry, testify in court, walk

the streets, go to (even segregated) school, ride public

transportation, and so on, only in the event that no

reason, not clearly untenable, can be assigned by a

state legislature for their not being permitted to do

these things. That cannot have been what all the noise

was about in 1866.

What the fourteenth amendment, in its historical

setting, must be read to say is that the Negro is to

enjoy equal protection of the laws, and that the fact

of his being a Negro is not to be taken to be a good

enough reason for denying him this equality, however,

“reasonable” that might seem to some people. All

possible arguments, however convincing, for discrim

inating against the Negro, were finally rejected by the

fourteenth amendment.4

However, if it is thought to be necessary to inquire

whether Virginia’s law serves any legitimate interest of the

State which can justify the racial classification, any linger

ing doubt about the invalidity of the law ought to be readily

dispelled.

4 Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions, 69 Y ale L J

421, 423 (1960).

9

The court below asserts “an overriding state interest in

the institution of marriage” (R. 24). Surely the States

have traditionally exercised considerable control over the

institution and incidents of marriage. But state legislative

power over marriages is not omnipotent. State power over

marriages, like “Legislative control of municipalities,” must

of necessity lie “within the scope of relevant limitations

imposed by the United States Constitution.” Cf. Gomillion

v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 344-345. The right to marry

is a protected liberty under the Fourteenth Amendment,

and is one of the “basic civil rights of man.” Skinner v.

Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541. In Meyer v. Nebraska, 262

U.S. 390, 399, this Court declared:

While this court has not attempted to define with

exactness the liberty thus guaranteed [by the Four

teenth Amendment], the term has received much con

sideration, and some of the included things have been

definitely stated. Without doubt, it denotes not merely

freedom from bodily restraint, but also the right of

the individuals to . . . marry, establish a home and

bring up children. . . .

The several majority opinions in Griswold v. Connecticut,

381 U.S. 479, demonstrate that a variety of constitutional

doctrines have been thought to limit the power of the

states over the marriage relationship.

Virginia’s principal apparent claimed justification for

the law against interracial marriage is that stated in Naim

v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E.2d 749, 756, the purpose to

“preserve the racial integrity of its citizens,” and prevent

what it calls “a mongrel breed of citizens” . The state’s

justification thus turns on the amalgam of superstition,

mythology, ignorance and pseudo-scientific nonsense sum

10

moned up to support the theories of white supermacy and

racial “purity.” 5

Clearly, this basis for anti-marriage laws rests on theories

long deemed nonsensical throughout the world’s community

of natural scientists. The distinguished American geneticist

Theodosius Dobzhansky has said:

The idea of a pure race is not even a legitimate

abstraction; it is a subterfuge used to cloak one’s

ignorance of the phenomenon of racial variation.

(Dobzhansky, “The Race Concept in Biology,” The

Scientific Monthly, LII (Feb. 1941), pp. 161-165.)

And see the many scientific authorities rejecting the “pure

race” idea collected in Weinberger, “A Reappraisal of the

5 Such nonsensical material pervades the legal opinions upholding laws

against intermarriage. See, for example, State v. Jackson, 80 Mo. 175,

179 (1883):

“It is stated as a well authenticated fact that if the issue of a

black man and a white woman and a white man and a black woman

intermarry, they cannot possibly have any progeny, and such a fact

sufficiently justifies those laws which forbid the intermarriage of

blacks and whites. . . . ”

See also, Scott v. Georgia, 39 Ga. 321, 323 (1869) :

“ The amalgamation of the races is not only unnatural, but is

always productive of deplorable results. Our daily observations show

us, that the offspring of these unnatural connections are generally

sick and effeminate, and that they are inferior in physical develop

ments and strength to the full-blood of either race. . . . Such con

nections never elevate the inferior race to the position of superior,

but they bring down the superior to that of the inferior. They are

productive of evil, and evil only, without any corresponding good.”

(Emphasis added.)

It is notable that even the word “miscegenation,” now widely used in legal

literature to refer to intermarriage, was reportedly invented as a hoax

in an 1864 political pamphlet connected with a presidential campaign.

See discussion in Montague, Man ’s Most Dangerous My t h : T he F al

lacy of F ace, 400 (4th ed. 1964).

11

Constitutionality of Miscegenation Statutes,” 42 Cobnell

L. Q. 208, 217, n. 68.6 7

The 1952 UNESCO Statement On The Nature of Race,1

prepared by distinguished natural scientists from around

the world, concludes:

There is no evidence for the existence of so-called

“pure” races. Skeletal remains provide the basis of

our limited knowledge about earlier races. In regard

to race mixture, the evidence points to the fact. that

human hybridization has been going on for an in

definite but considerable time. Indeed, one of the

processes of race formation and race extinction or

absorption is by means of hybridization between races.

As there is no reliable evidence that disadvantageous

effects are produced thereby, no biological justifica

tion exists for prohibiting intermarriage between per

sons of different races.

Similarly, other pseudoscientific props for racism, includ

ing the notions of biological disadvantages of race mixture,

and the assumption that cultural levels depend on racial

factors, are completely undermined by modern scientific

knowledge.8 For example, the 1952 UNESCO Statement,

supra, concludes by saying:

6 See also Note, 58 Y ale L. J. 472 (1949).

7 The full title is: “ Statement on the Nature o f Race and Race Differ

ences—by Physical Anthropologists and Geneticists, September 1952,”

published by UNESCO. The statement, published in numerous publica

tions by UNESCO is conveniently available in Appendix A of Montague,

op. cit., 361 et seq.

8 The importance of environmental factors in determining cultural levels

was noted by the court in Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P.2d 17,

24-25 (1948). Major contemporary research demonstrating the absence

of any relation between race and cultural achievement is found in Beals

and Hoijer, A n I ntroduction to A nthropology, 195-198 (1953); Han

kins, T he R acial Basis of Civilization 367-371 (1926); Kroeber,

12

9. We have thought it worth while to set out in

a formal manner what is at present scientifically es

tablished concerning* individual and group differences.

(1) In matters of race, the only characteristics which

anthropologists have so far been able to use effec

tively as a basis for classification are physical (anatom

ical and physiological).

(2) Available scientific knowledge provides no basis

for believing that the groups of mankind differ in their

innate capacity for intellectual and emotional develop

ment.

(3) Some biological differences between human be

ings within a single race may be as great or greater

than the same biological differences between races.

(4) Vast social changes have occurred that have

not been connected in any way with changes in racial

type. Historical and sociological studies thus support

the view that genetic differences are of little significance

in determining the social and cultural differences be

tween different groups of men.

(5) There is no evidence that race mixture produces

disadvantageous results from a biological point of view.

The social results of race mixture whether for good

or ill, can generally be traced to social factors.

And see, generally, Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous

Myth: The Fallacy of Race (4th ed. 1964), for a noted

anthropologist’s full discussion of the most recent scientific

evidence and research on race.

A nthropology 190-192 (1958); Ashley Montague, A n I ntroduction to

P hysical A nthropology 352-381 (1951); Yerkes, “ Psychological Ex

amining in the U. S. Army,” 15 Mem . Nat. A cad. Sci. 705-742 (1921).

13

Actually, the laws against interracial marriage grew out

of the system of slavery and were based on race prejudices

and notions of Negro inferiority used to justify slavery,

and later segregation. Chief Justice Taney said in Scott v.

Sandford, 19 How. (60 TJ.S.) 393, 409 that laws against

intermarriage:

. . . show that a perpetual and impassable barrier

was intended to be erected between the white race and

the one which they had reduced to slavery, and gov

erned as subjects with absolute and despotic power,

and which they then looked upon as so far below them

in the scale of created beings, that intermarriages be

tween white persons and negroes or mulattoes were

regarded as unnatural and immoral, and punished

as crimes, not only in the parties, but in the persons

who joined them in marriage. And no distinction in

this respect was made between the free negro or

mulatto and the slave, but this stigma, of the deepest

degradation, was fixed upon the whole race.

The court below disparaged the scientific texts cited to

it by appellants as an invitation to “judicial legislation”

(R. 25). But it is the state which must justify its racial

classification. And the state can no more justify its racial

classification here by reference to a nonsensical theory of

pure races and racial superiority than it could impose some

special disability on some citizens on a theory of witch

craft, or restrict their liberty of movement on a claim that

the earth is flat.

The sum of the other justifications for the laws against

interracial marriage amount to little more than a claim

that they promote segregation. They are exemplified by

the opinion of the trial judge in appellants’ case who de

clared :

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow,

malay and red, and he placed them on separate con

14

tinents. And but for the interference with his arrange

ment there would be no cause for such marriages.

The fact that he separated the races shows that he

did not intend for the races to mix (E. 16).

Such a theory could, of course, support any kind of dis

criminatory practice which the States have ever devised;

and, indeed, it seems to suggest discriminations never yet

attempted in this country. As an individual the Judge is

entitled to entertain his private theology. But the Four

teenth Amendment places it entirely beyond the power

of the state courts to implement racial discrimination,

whatever the rationale.

The court below thought it important to mention it§

statement in Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S.E.2d 749, 753,

that “more than one-half of the states then [1955] had

miscegenation statutes” (E. 21). That statement is, of

course, no longer true. Thirteen states have repealed their

anti-marriage laws since 1951 (see Appendix I, infra).

Laws prohibiting interracial marriages continue in the

statute books of only 17 of the 50 states (see Appendix II,

infra), and it is notable that all of these are southern and

border states which had extensive segregation codes9 prior

to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483.

These laws, having only a racial character and purpose,

are relics of the system of human slavery. They should be

struck down for the same reasons this Court has in

validated all other segregation laws. As a result of these

many decisions, laws against interracial marriage are

among the last of such racial laws with any sort of claim

to viability. But they are the weakest, not the strongest,

of the segregation laws. They intrude a racist dogma into

9 The segregation codes of the pre-Brown era are collected in Murray,

States’ Laws ok R ace and Colob (1951).

15

the private and personal relationship of marriage. The

state has no semblance of a rational claim of interest in

such an intrusion. Virginia’s laws punishing interracial

marriage violate the -Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Gtbeenbebg

J ames M. N abbit, I I I

M ichael M eltskeb

M elvyn Z aeb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. as

Amicus Curiae

17

APPENDIX I

S tates R epealing L aw s A gainst I nterracial M arriage

I n R ecent Y ears

1. Arizona (1962) :

2. California (1959) :

3. Colorado (1957) :

4. Idaho (1959):

5. Indiana (1965) :

6. Montana (1953):

7. Nebraska (1963):

8. Nevada (1959) :

Laws 1962, ch. 14, §1, delet

ing a portion of Ariz. Rev.

Stat. §25-101 (1956).

Stat. 1959, eh. 146, §1, at

2043, repealing Cal. Civ.

Code §§60, 69 (1954).

Colorado Laws 57, §1, at 334,

repealing Colo. Rev. Stat.

§§90-1-2, 90-1-3 (1953).

Laws 1959, ch. 44, §1, at 89,

deleting Idaho Code Ann.

§32-206 (1947).

Acts 1965, No. 1039, repeal

ing Ind. Ann. Stat. §44-104

(Burns, 1952).

Laws 1953, ch. 4, sec. I, re

pealing Laws 1909, ch. 49,

secs. 1-5.

Neb. Sess. Laws, at 736

(1963), repealing Rev. Stat.

of Neb. §§42-103, 42-328

(1948).

Nev. Stat. 1959, at 216, 217,

repealing Nev. Rev. Stat. tit.

11, ch. 122, 180 (1957).

18

9. North, Dakota (1955) : N.D. Stat. 1955, ch. 246, §1,

repealing N.D. Code §14-

03-04.

10. Oregon (1951) : O.E.S. §106.210 (1963), re

pealing Ore. Code Law Ann.

§§23-1010, 63-102.

11. South Dakota (1957) : S.D. Sess. Laws 1957, ch. 38,

repealing S.D. Code §14.990

(1939).

12. Utah (1963): Sess. Laws 1963, ch. 43, re

pealing IJtah Stat. §30-1-2

(1953).

13. Wyoming (1965) : Acts 1965, No. 3, repealing

Wyo. Stat. §§20-18, 19.

19

APPENDIX II

S tates at P resent P rohibiting I nterracial M arriages

(P enalties for I nfractions A re I ndicated)

1. Alabama: Ala. Const. §102; Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §360

(1958); 2-7 imprisonment (idem.).

2. Arkansas: Ark Stat. §55-104 (1947); 1 year imprison

ment and/or $250 tine (Ark. Stat. §41-106).

3. Delaware: Del. Code Ann., Tit. 13, §101 (1953); $100

fine in default of which imprisonment for not more

than 30 days (Del. Code Ann., Tit. 13, §102).

4. Florida: Fla. Const, art. XVI, §24; Florida Stat.

§741.11 (1961); maximum 10 years imprisonment

and/or maximum fine of $1,000 (Fla. Stat. §741.12).

5. Georgia: Ga. Code Ann., §53-106 (1933); 1 to 2 years

imprisonment (Ga. Code Ann. 53-9903).

6. Kentucky: Ky. Rev. Stat. §402.020 (1943); fine of $500

to $1000 and if violation continued after conviction,

imprisonment of 3 to 12 months (K.R.S. §402.990).

7. Louisiana: La. Civil Code Art. 94 (Dart. 1945); 5 years

imprisonment (La. Rev. Stat. Ch. 14, §79).

8. Maryland: Md. Ann. Code Art. 27, §398 (1957); im

prisonment from 18 months to ten years (idem.).

9. Mississippi: Miss. Const, art. 14, §263; Miss. Code Ann.

§459 (1942); Imprisonment up to 10 years (Miss.

Code Ann. §2000, 1960).

10. Missouri: Mo. Rev. Stat. §451.020 (Supp. 1966); 2

years in state penitentiary; and/or a fine of not

less than $100, and/or imprisonment in county jail

for not less than 3 months (Mo. Rev. Stat. §563.240).

20

11. North Carolina: N.C. Const, art. XIV, §8; N.C. Gen.

Stat. §51-3 (1953); 4 months to 10 years imprison

ment (N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-181).

12. Oklahoma: Okla. Stat., Tit. 43, §12 (1961); 1 to five

years and up to $500 fine (Okla. Stat., Tit. 43, §13).

13. South Carolina: S.C. Const, art. 3, §34; S.C. Code

§20-7 (1952); imprisonment for not less than 12

months, and/or fine of not less than $500 (idem.).

14. Tennessee: Tenn. Const, art. (11), §14; Tenn. Code

Ann. §36-402 (1956); 1 to 5 years imprisonment, or,

on recommendation of jury, fine and imprisonment

in county jail (Tenn. Code Ann. §36-403).

15. Texas: Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. art. 4607 (1948); 2 to 5

years imprisonment (Tex. Penal Code art. 492).

16. Virginia: Va. Code Ann. §20-54 (1953); 1 to 5 years

(Va. Code Ann. §20-59).

17. West Virginia: W. Va. Code Ami. §4697.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. c."4Jgf». 219