Burr v National Labor Relations Board Brief and Argument for Intervenor

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burr v National Labor Relations Board Brief and Argument for Intervenor, 1953. 804b0f25-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16d3a81e-7c06-4006-8313-932e671e0e1a/burr-v-national-labor-relations-board-brief-and-argument-for-intervenor. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Umteb H>tate£S Court of Appeals!

JftCti) Circuit

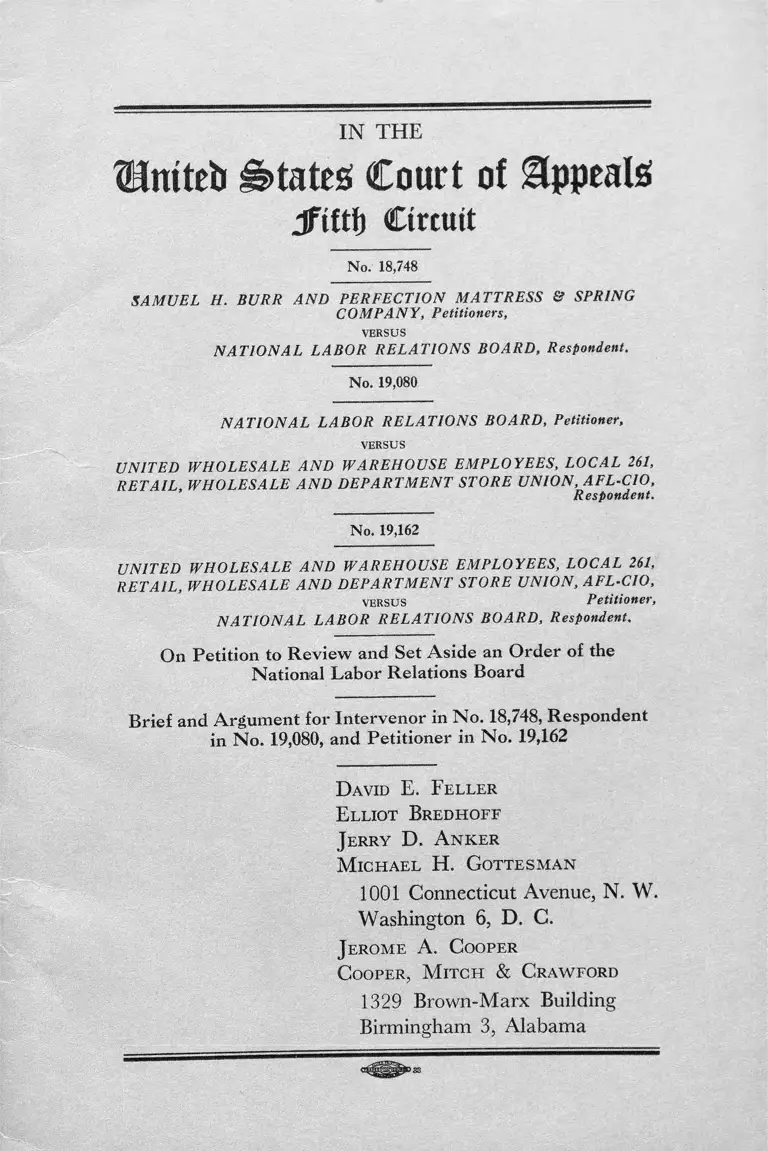

No. 18,748

SAMUEL H. BURR AND PERFECTION MATTRESS & SPRING

COMPANY, Petitioners,

VERSUS

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Respondent.

IN THE

No. 19,080

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Petitioner,

VERSUS

UNITED WHOLESALE AND WAREHOUSE EMPLOYEES, LOCAL 261,

RETAIL, WHOLESALE AND DEPARTMENT STORE UNION, AFL-CIO,Respondent.

No. 19,162

UNITED WHOLESALE AND WAREHOUSE EMPLOYEES, LOCAL 261,

RETAIL, WHOLESALE AND DEPARTMENT STORE UNION, AFL-CIO,

v e r su s Petitioner,

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Respondent.

On Petition to Review and Set Aside an Order of the

National Labor Relations Board

Brief and Argument for Intervenor in No. 18,748, Respondent

in No. 19,080, and Petitioner in No. 19,162

D avid E . F eller

E lliot B r e d h o f f

J erry D . A n k e r

M ic h a e l H. G o t t e s m a n

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.

J erom e A . C ooper

C ooper , M it c h & C raw ford

1329 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham 3, Alabama

INDEX

Page

STATEMENT OF THE CASE........................................................ 1

QUESTIONS PR E SE N T E D ............................................................ 8

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS..................................................... 8

ARGUMENT:

I. The Order Should Be Set Aside.............................................. 9

1. Peaceful Consumer Picketing in Front of a Retail

Store Asking Customers Not to Purchase Products of a

Particular Manufacturer Does Not, Per Se, “Threaten,

Coerce or Restrain” the Retailer with an Object of

“Forcing or Requiring” Him to Cease Doing Business

with the Primary Producer............................................. 10

2. If Interpreted to Prohibit, Per Se, Consumer Picketing

in Front of Secondary Establishments, § 8(b) (4) (ii)

Unconstitutionally Infringes Upon Freedom of Speech 19

II. The Order Should Not Be Modified....................................... 26

CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 27

Gases

A. F. of L. v. Swing, 312 U.S. 321 (1941)....................................... 22

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U.S. 769 (1942)...................20, 23

Building Service Union v. Gazzam, 339 U.S. 532 (1950)............... 23

Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106 (1940)...........................21, 22, 26

Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Ritter’s Cafe, 315 U.S. 722

(1942) ............................................................................................. 22, 23

Chauffeurs v. Newell, 181 Kan. 898, 317 P. 2d 817 (1957), rearg.

den. 182 Kan. 205, 319 P. 2d 171 (1958)..................................... 24

Chauffeurs v. Newell, 356 U.S. 341 (1958)....................................... 24

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951)................................. 25

Electrical Workers v. N.L.R.B., 341 U.S. 694 (1951).................23, 25

Fruit and Vegetable Packers v. N.L.R.B., — F. 2d —, 50 LRRM

2392 (D.C. Cir. 1962).......................17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27

Giboney v. Empire Storage, 336 U.S. 490 (1949)........................... 23

International Association of Machinists v. Street, 367 U.S. 740

(1961) ............................................................................................... 10

11

Page

Lebus v. Building and Construction Trades, 199 F. Supp. 628

(E.D. La. 1961)................................................................................. 26

Minneapolis House Furnishing Co., 132 N.L.R.B. No. 2 (1961).. 7

N.L.R.B. v. Fournier, 182 F. 2d 621 (2 Cir. 1950)......................... 27

Plumbers Union v. Graham, 345 U.S. 192 (1953).......................23, 24

Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union v. Rains, 226 F.

2d 503 (5 Cir. 1959)......................................................................... 3

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919)................................. 25

Teamsters v. Hanke, 339 U.S. 470 (1950) ........................................ 23

Teamsters v. Vogt, 354 U.S. 284 (1957)....................................... 19, 23

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940)...............19, 21, 22, 23, 24

United States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612 (1954)................................. 10

United Wholesale and Warehouse Employees v. N.L.R.B., 282 F.

2d 824 (D.C. Cir. 1960).................................................................. 4, 6

Wooten v. Ohler, — F. 2d —, 50 LRRM 2446 (5 Cir. 1962) . . 19, 20, 24

Statutes

National Labor Relations Act,

§ 8(b) (4) (A), 29 U.S.C.A. § 158(b) (4) (A ) ...............3, 4, 23, 25

§ 10(e), 29 U.S.C.A. § 160(e)........................................................ 27

§ 10(1), 29 U.S.C.A. § 160(1).......................................................... 3

National Labor Relations Act, as amended

§ 8(b) (4) (i) (B), 29 U.S.C.A. § 8(b) (4) (i) ( B ) . . . .4, 6, 7, 8, 21

§8 (b) (4) (ii) (B), 29 U.S.C.A. § 8(b) (4) (ii) (B ) . . . .4, 6, 8, 9-27

§ 8 (b) (7), 20 U.S.C.A. § 158(b) (7 ) ................................. 12, 19, 26

Legislative Materials

H. R. Rep. No. 471, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)............................. 12

H. R. Rep. No. 1147, 86th Cong., 1st Sess (1959)........................... 12

“Legislative History of the Labor Management Reporting and Dis

closure Act of 1959” ....................................................9, 13, 14, 15, 16

S. Doc. No. 10, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)................................... 13

S. Rep. No. 187, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)................................. 12

Articles, Notes, etc.

Cox, Strikes, Picketing and The Constitution, 4 V'and. L. Rev.

574 (1951) .....................................................................................20, 25

Note, 107 U. Pa. L. Rev. 127 (1958)................................................ 25

Samoff, Picketing and the First Amendment: “Full Circle” and

“Formal Surrender,” 9 Lab. L.J. 889 (1958)............................... 25

IN THE

©ntteb S ta te s Court of Appeals!

Jfiftf) Circuit

No. 18,748

SAMUEL H. BURR AND PERFECTION MATTRESS & SPRING

COMPANY, Petitioners,

VERSUS

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Respondent,

No. 19,080

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Petitioner,

VERSUS

UNITED WHOLESALE AND WAREHOUSE EMPLOYEES, LOCAL 261,

RETAIL, WHOLESALE AND DEPARTMENT STORE UNION, AFL-CIO,

Respondent.

No. 19,162

UNITED WHOLESALE AND WAREHOUSE EMPLOYEES, LOCAL 261,

RETAIL, WHOLESALE AND DEPARTMENT STORE UNION, AFL-CIO,

Petitioner,

VERSUS

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Respondent,

On Petition to Review and Set Aside an Order of the

National Labor Relations Board

Brief and Argument for Intervenor in No. 18,748, Respondent

in No. 19,080, and Petitioner in No. 19,162

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case, which involves the validity of consumer picket

ing by the United Wholesale and Warehouse Employees,

Local 261, Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union,

AFL-CIO (hereinafter “the Union” ) against the products of

the Perfection Mattress & Spring Company (hereinafter

2

“Perfection” )—the primary employer with whom the Union

had a legitimate labor dispute—is the sequel to extensive

litigation instituted by Perfection to prevent the picketing.

1. The original picketing and the litigation which follow ed

Perfection, at its Birmingham plant, is engaged in the

manufacture of mattresses, springs and furniture, which it

sells to retail furniture stores in Birmingham [T.R. 46].1 In

August or September, 1958, the Union was certified as the

collective bargaining representative of Perfection’s Birming

ham employees [O.T.R. 42].1 A series of bargaining confer

ences were held between representatives of Perfection and

the Union, resulting in an impasse, and on October 14, 1958,

Perfection’s employees struck and picketed the Birmingham

plant. Perfection hired non-union employees to replace the

strikers. The Union thereupon commenced peaceful picket

ing on the public sidewalk in front of certain retail furniture

stores selling Perfection mattresses. Not more than two pick

ets at a time appeared at any store. They carried signs

stating:

“Products made by Perfection Mattress and Spring

Company are made by non-union labor. As a con

sumer, please do not buy them. Local 261, AFL-CIO.”

The pickets did not appear until after the hour at which

employees of the stores normally reported to work, and they

left before the hour at which the store employees normally

ceased work. No appeal was made to store employees or

employees delivering and picking up goods at the store. No

employee of the stores quit work or indicated any inclina

tion or intention to do so. None refused to handle Perfec

t s used herein, “T.R.” refers to the Transcript of Record in Cases

No. 18,748, 19,080 and 19,162; “S.T.R.” refers to the Supplemental

Transcript of Record in these cases; and “O.T.R.” refers to the Trans

cript of Record in Case No. 17,632, which is incorporated by reference

in the Transcript of the present proceedings [T.R. 3], and which con

stitutes the record upon which the Board’s decision herein was based.

3

tion-made products, nor were there any refusals to deliver

[O.T.R. 176-77].

Nevertheless, Perfection filed an unfair labor practice

charge with the N.L.R.B. on November 10, 1958 [O.T.R.

7-8], alleging that the picketing in front of the retail stores

constituted a violation of § 8(b) (4) (A) of the Taft-Hart-

ley Act (prior to its amendment in 1959), 29 U.S.C.A. § 158

(b) (4) (A), which made it an unfair labor practice to “in

duce or encourage” the employees of any employer to engage

in a strike or a “concerted refusal in the course of their em

ployment to . . . handle any goods . . . or to perform any

services” with an object of “forcing or requiring” any em

ployer to “cease doing business with any other person.”

The Board’s regional director issued a complaint and sought

a temporary injunction against the picketing under § 10(1)

of the Act, 29 U.S.C.A. § 160(1), from the District Court for

the Northern District of Alabama [O.T.R. 1-9]. A hearing

was held on the injunction application, at which the parties

presented extensive evidence [O.T.R. 17-167]. On the basis

of this evidence, the Court found that the picketing was

conducted in the manner we have described hereinabove

[O.T.R. 176-77], but nevertheless granted an injunction

[O.T.R. 172-74]. Picketing of the retail stores thereupon

ceased [T.R. 37]. On April 30, 1959, this Court affirmed

the issuance of the injunction, Retail, Wholesale and Depart

ment Store Union v. Rains, 226 F. 2d 503.

In the Board proceeding, the parties waived a hearing and

stipulated that the evidence taken in the injunction proceed

ing would constitute the “record” before the Board [T.R. 5].

On December 2, 1959, the Board, by a 3-2 vote, found that

on this record the Union had violated § 8(b) (4) (A), and

ordered the Union to cease and desist from “inducing” em

ployees of the retail stores. The Board rejected the Union’s

argument that because the picketing was addressed only to

the consuming public there was no inducement of employees.

The Board reasoned that because employees could see the

4

signs from within the store, and because on isolated occasions

picketers had addressed customers in tones loud enough to be

heard by employees within the store, the Union’s actions had

the “necessary effect” of inducing employees [T.R. 4-17].

On July 7, 1960, the Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia set aside the Board’s order, United Wholesale

and Warehouse Employees v. N.L.R.B., 282 F. 2d 284. Cit

ing the absence of any evidence that the Union had sought to

induce employees, or that the picketing had had that likely

effect, the Court said:

“Here, we simply cannot say from the record viewed

as a whole, that the union’s appeal to the customers had

the ‘necessary effect’ of inducing the neutral employees

to engage in concerted work stoppage when no such re

sult even remotely appears” (282 F. 2d at 827).

2. The subsequent picketing and the litigation leading to this

proceeding

On March 10, 1960, the Union recommenced virtually

identical picketing on the public sidewalks in front of retail

stores selling Perfection products [T.R. 38]. On March 14,

1960, Perfection, through its attorney Burr, filed a new

charge with the Board claiming that the renewed picketing

violated § 8(b) (4) (i) and (ii) (B) of the Act, as amended

in 1959. § 8(b) (4) (i) (B) continues without pertinent

change the old § 8(b) (4) (A) proscription of inducement

of employees. The charged violation of §8(b)(4)(i)(B )

thus raised again the issue already decided by the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia in the earlier case.2

§ 8(b) (4) (ii) (B), a new provision added to the Act in

1959, makes it an unfair labor practice for a union “to

2 As amended § 8(b) (4) (i) eliminated the requirement that induce

ment be of “concerted” refusals to work, and the Board originally

argued that the Court of Appeals’ opinion in the first Perfection case

was distinguishable because of this change [T.R. 54-56], But the

Court of Appeals’ decision does not seem to be premised on the exist

ence of that requirement.

5

threaten, coerce or restrain any person engaged in com

merce” when an object thereof is “forcing or requiring” a

neutral to cease doing business with the primary employer.

A complaint was issued, and on August 6, 1960, the par

ties entered into a stipulation [T.R. 34-41] waiving a hear

ing; providing that the transcript of the injunction proceed

ing would again be a part of the record; and further agree

ing that “the picketing . . . was conducted as follows:”

“A. Said picketing was peaceful at all times material

herein and was limited to not more than one picket at

any one time. This picket was on the public sidewalk

in front of the store and carried a picket sign visibly

reading:

“ ‘To The Consuming Public—Products Made By

Perfection Mattress & Spring Company Are Made By

Non-Union Labor. As A Consumer, Please Do Not

Buy Them. Local 261, AFL-CIO’.

“B. The picket did not appear until after the hour at

which employees of the stores normally reported to work

and the picket left before the hour at which such em

ployees normally left work at the end of the day.

“C. No picket was placed at back or service en

trances to which deliveries of merchandise were made

at the stores, and through which some employees of the

store regularly came and went. Employees of the stores

could see, and some saw, the picket sign from inside the

stores, and also when, as some employees did, such em

ployees used the public entrances of the stores to enter

or to leave in the course of a day.

“D. No truck drivers or deliverymen were asked not

to deliver to the stores’ service entrances or to any other

entrance and no such employee refused to make any

such delivery.

“E. No employee of the stores quit work or indicated

6

any inclination or intention to do so, or to refuse to han

dle Perfection-made products as a result of or during

the picketing.

“F. No appeal, other than by the picketing described

above, has been made since to-wit: December 9, 1958,

by Respondent directly to employees of the retail stores,

or any other person or persons, including the retail store

employers handling retail products of Perfection.

“G. Respondent made no attempt to organize or to

recruit membership among employees of the stores.

There has been no work stoppage at any time material

herein by employees of Braswell, Willoughby, or other

retail stores pursuant to said picketing.” [T.R. 38-39].

The Union discontinued its picketing pursuant to an

agreement between it and the General Counsel that the case

would proceed in accordance with the stipulation [T.R. 49].

On December 28, 1960, the Board rendered a decision

holding that the picketing violated both § 8(b) (4) (i) and

(ii) (B) [T.R. 43-62]. With respect to inducement of em

ployees, the Board stated that it disagreed with the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia, and adhered to its

original opinion [T.R. 54].

With respect to the new provision—§ 8(b)(4)(ii)(B ) —

the Board held that all consumer picketing in front of sec

ondary stores constitutes “coercion and restraint” of the sec

ondary stores [T.R. 56-69]. The Board rested this sweeping

conclusion upon two isolated items of legislative history.

First, a statement by Representative Griffin who, when told

about a hypothetical boycott situation which according to

the Board “strikingly resembles the present situation,” re

plied that “such a boycott could be stopped” [T.R. 57]. Sec

ond, a proviso to § 8(b) (4) exempting from regulation

“publicity other than picketing,” and which, the Board con

cluded, prohibits all secondary consumer picketing “by [its]

literal wording” as well as “through the interpretive gloss

placed thereon by its drafters” [T.R. 59],

7

The Board ordered the Union to cease and desist from (a)

inducing or encouraging employees to strike, or refuse to de

liver to, the neutral employers, and (b) “threatening, co

ercing or restraining” the neutral employers; where in either

case, an object thereof is to force the neutrals to cease doing

business with Perfection [T.R. 61].

On December 30, 1960, Perfection and Burr filed a peti

tion for review with this Court, No. 18,748 [S.T.R. 1-3].

Their sole basis for claiming to be “aggrieved” was that the

Board order (which enjoined the Union, in the language of

the statute, from “threatening, coercing or restraining” the

employer) was insufficient to reach the peaceful consumer

picketing engaged in by the Union. A motion by the Board

to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction [S.T.R. 5] was denied by

order of May 4, 1961 by this Court, which held that the

Board’s failure to prohibit “acts of picketing” made Perfec

tion an “aggrieved” party [S.T.R. 5-6]. The Union was per

mitted to intervene [S.T.R. 32].

The Board petitioned for enforcement of its order, No.

19,080 [S.T.R. 8], and on August 16, 1961, the Union’s peti

tion for review, which originally had been filed in the Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia and had been trans

ferred [S.T.R. 27-28], was docketed in this Court as No.

19,162 [S.T.R. 17-19]. The three petitions were consoli

dated for briefing and argument [S.T.R. 32].

On August 17, 1961, the Board moved for permission to

amend its decision and order [S.T.R. 28-29], in light of its

opinion in Minneapolis House Furnishing Co., 132 NLRB

No. 2 (1961), holding on identical facts that there was no

inducement of employees. This Court remanded the case

to the Board [S.T.R. 33] and the Board issued a Supple

mental Decision and Order reversing its finding of violation

o f§8 (b )(4 )(i)(B ), and deleting the “cease and desist from

inducing employees” provision from its order [T.R. 66-69].

The Court’s remand order had specifically provided the

parties “the right to file whatever amended pleadings and

8

papers as each might think advisable or appropriate” [S.T.R.

33]. Perfection and Burr have, however, not amended their

petition for review to complain of the Board’s reversal of

decision and amendment of order as to § 8(b) (4) (i) (B).

Accordingly, that issue is not before this Court.

The single issue is the validity of the Board’s decision and

order under § 8(b) (4) (ii) (B). The Board, in No. 19,080,

seeks enforcement of the order; Perfection and Burr, in No.

18,748, seek modification of the order; and the Union, in

No. 19,162, seeks to have the order set aside.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

On a record devoid of any evidence of actual coercion or

restraint, the Board has ruled that peaceful consumer pick

eting in front of a retail store constitutes “coercion” and “re

straint” of the stores. It bases this decision on its interpreta

tion that the statute makes consumer picketing in front of a

secondary establishment unlawful per se. This ruling raises

two questions:

1. Does § 8(b) (4) (ii) of the Taft-Hartley Act prohibit,

per se, peaceful consumer picketing in front of retail stores

asking customers not to purchase the products of a Company

with which the Union has a primary labor dispute?

2. If so interpreted, would § 8(b) (4) (ii) unconstitution

ally infringe upon freedom of speech?

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS

The National Labor Relations Board erred in finding that

the peaceful consumer picketing in this case violated § 8(b)

(4) (ii), and in interpreting the statute so as to render it an

unconstitutional infringement upon freedom of speech.

9

ARGUMENT

I. THE ORDER SHOULD BE SET ASIDE

The Board’s decision in this case rests exclusively upon its

conclusion that § 8(b) (4) (ii) outlaws consumer picketing

perse [T.R. 56-69].

In the argument that follows, we submit two grounds for

setting aside the Board’s order: (1) the Act does not pro

hibit consumer picketing per se; and (2) if it did, it would

unconstitutionally infringe upon freedom of speech. Ob

viously these two grounds are interrelated.

Congress was aware of the Constitutional protections due

picketing, and § 8(b)(4)(h) is carefully drafted so that,

given a reasonable reading, it does not infringe upon them.

Representative Griffin, discussing the applicability of his

bill to consumer picketing, cautioned that:

“Of course this bill and any other bill is limited by

the constitutional right of free speech” 2 Leg. Hist.

1615(2).3

In this same discussion, Representative Griffin, referring

to the ban on organizational picketing created by § 8 (b) (7),

reiterated the desire not to infringe upon the speech aspects

of picketing:

“. . . This is subject, however, to the constitutional

rights of free speech. Unless the picketing is for the

coercive purpose indicated, it would not be affected by

this language. In other words, whether it is the hand

ing out handbills or putting an ad in the paper or pick

eting, if it is done in such a way so as clearly to be noth

ing more than an exercise of free speech then the pro

vision would not be violated” 2 Leg. Hist. 1615(3).

In interpreting the Act, weight must be accorded the spon

3 “Leg. Hist.” refers to the two-volume series “Legislative History

of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959,”

published by the National Labor Relations Board. Figures in paren

thesis following the page number locate the column on the page.

10

sor’s desire (International Association of Machinists v.

Street, 367 U.S. 740, 765-68 (1961)), as well as the Courts’

(U. S. v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612, 617-24 (1954)) to avoid

constitutional questions.

While we reserve to Part 2 of this Argument our discus

sion of the constitutional deficiencies of the Board’s inter

pretation, these constitutional implications are of course,

necessarily relevant in interpreting the statutory language.

I . Peaceful Consum er P icketing in Front of a R eta il Store

A sking Custom ers N o t to Purchase Products of a Particular

M anufacturer D oes N ot, Per Se, “ Threaten, C oerce or R e

strain” the R etailer with an O bject of “Forcing or Requiring”

H im to Cease Doing Business with the P rim ary Producer.

The language of § 8(b) (4) (ii) (B), into which the Board

seeks to fit its prohibition of all secondary consumer picket

ing, makes it an unfair labor practice for a Union to

“threaten, coerce or restrain any person engaged in com

merce” with an object of “forcing or requiring” that person

to “cease doing business with any other person.” The Board

has found that the Union’s consumer picketing in this case

coerced and restrained the retail furniture stores, with an

object of forcing or requiring them to stop handling Perfec

tion’s products. It made this finding in the absence of any

evidence that the picketing was either “coercive” or “re

straining,” or that it had as an object “forcing or requiring”

the retail stores to cease dealing with Perfection.

There was only one picketer in front of each store. That

lone picketer carried a sign addressed to the consuming pub

lic, advising that the Union had a primary dispute with Per

fection, and asking that customers not buy Perfection prod

ucts. The sign did not mention the retail store, let alone ask

customers to boycott the store. And there is no evidence

that a single consumer withheld his patronage from a retail

store as a result of the picketing.

Indeed, the Union did not desire a boycott of the stores.

Its sole desire was to induce customers to boycott Perfection

11

products. Any customer who entered the store and pur

chased a rival product would help, not hurt, the Union’s

cause. It was precisely to encourage such conduct that the

Union engaged in picketing.

No work stoppages or refusals to pick-up and deliver oc

curred at the retail stores, and indeed, the Board has found

that the picketing was not designed to induce such activity.

Nor is there any evidence that the picketing coerced any

prospective customers. The lone picketer engaged in no con

duct which could in any way frighten or deter a prospective

customer from entering the retail store.

In short, the picketing was part of a direct, primary boy

cott directed against Perfection. It was not aimed at any

retail store, and there is no evidence that it had any effect on

any store. It was not “coercive” or “restraining,” and surely

it did not have as an object “forcing” or “requiring” the re

tail stores to cease handling Perfection mattresses.4

To be sure, the picketing took place on the public side

walks in front of the retail stores. The Union chose these

locations because they were the most effective points from

which to appeal to consumers not to buy Perfection prod

ucts. Furniture is marketed through retail stores. Custom

ers do not visit the factory. Accordingly, it would have

made no sense for the Union to picket at the premises of

Perfection’s plant. The retail stores are where the custom

ers go and are the only places where appeals to customers

can be made. But proximity to the stores in no way proves

coercion of the stores. Indeed, no retailer has been heard to

4 The Board seems to say that since cessation of handling Perfection

mattresses by the retail stores would help the Union’s cause, its “object”

was “forcing or requiring” that result. This is fallacious. The Union’s

campaign was, in effect, an advertising campaign. Whenever advertis

ing is successful, it benefits some brands to the detriment of others.

Those products which suffer may, in turn, be dropped by retailers

which formerly handled them. But surely it does not follow that the

object of the advertiser is “forcing or requiring” that result. To bene

fit by a result, even to desire it, is not to “force or require” it.

12

complain in this case. The charges were filed, and have

been pursued, by Perfection alone.

Thus, the Union’s activity here simply does not fit the lan

guage of the statute. Indeed, Perfection agrees that the

picketing here does not coerce or restrain the retail stores,

for in its petition it claims that it is “aggrieved” by the

Board’s order that the Union cease and desist from threaten

ing, coercing or restraining the stores. This Court apparently

agrees, for it has ruled that Perfection is “aggrieved” by the

Board’s failure to prohibit “acts of picketing.” Even the

Board does not suggest that the activity here violates the lan

guage of the statute. Rather, the Board relies on what it

conceives to be the intent of Congress, notwithstanding the

language of the statute, that all “consumer picketing in front

of a secondary establishment is prohibited” [T.R. 59].

This interpretation is quite a step from the statutory lan

guage, which prohibits, not “picketing,” but “threats, co

ercion and restraint.” And Congress is no novice at pro

hibiting picketing when it wants to. In § 8(b) (7), passed

simultaneously with § 8(b) (4) (ii), Congress made it an un

fair labor practice for a Union

“to picket or cause to be picketed, or threaten to picket

or cause to be picketed, any employer where an object

thereof is [to force recognition of an uncertified union].”

Moreover, the Board’s excursion from the statutory lan

guage finds no support in any legislative report. Neither

the Senate5 nor the House Report6 suggests that Congress

intended to outlaw all consumer picketing, and the Confer

ence Report,7 which explains the compromise reached on

8(b) (4) (ii), nowhere indicates that the compromise is to

apply to all secondary consumer picketing.

Indeed the purpose of § 8(b) (4) (ii), as described by its

sponsors, was to reach a wholly different type of conduct.

5 S. Rep. No. 187, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959).

6 H.R. Rep. No. 741, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959).

7 H.R. Rep. No. 1147, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. 38 (1959).

13

While existing law prohibited direct appeals to secondary

employees, it did not prohibit threats made directly to the

secondary employer that, unless he assented to the Union’s

desires, economic action directed against him would be forth

coming. Legislators supporting § 8(b)(4)(h) were con

vinced that the threats were as effective as the direct ap

peals to employees, and accordingly they felt there was a

“loophole” in existing law. Representative Griffin’s explana

tion is typical.

“The courts also have held that, while a union may

not induce employees of a secondary employer to strike

for one of the forbidden objects, they may threaten the

secondary employer, himself, with a strike or other eco

nomic retaliation in order to force him to cease doing

business with a primary employer with whom the union

has a dispute. This bill makes such coercion unlawful by

the insertion of a clause 4 (ii) forbidding threats or co

ercion against ‘any person engaged in commerce or an

industry affecting commerce.’ ” 2 Leg. Hist. 1523(1).8

The Board, in reaching its result, overlooks these explana

tions of the purpose of § 8(b) (4) (ii), and instead relies

upon isolated remarks of Representative Griffin, a sponsor,

and Senator Kennedy, an opponent. Read out of context, as

the Board has read them, these statements are susceptible of

the interpretation which the Board gives them. But, placed

in perspective, they simply do not say what the Board would

have them say.

The Senate, after an extensive debate, had voted down

8 To the same effect, see President Eisenhower’s Message, S. Doc.

No. 10, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959), item No. 11, printed at 1 Leg.

Hist. 82; Secretary of Labor Mitchell’s explanation, 2 Leg. Hist.

994(1); Minority Views, S. Rep. No. 187, supra, at 79; Remarks of

Senator Goldwater, 2 Leg. Hist. 1079 (2) (3); Remarks of Representa

tives Landrum and Griffin, 2 Leg. Hist. 1523(1) ; Remarks of Rep

resentative Griffin, 2 Leg. Hist. 1568(2); Remarks of Representative

Rhodes, 2 Leg. Hist. 1581(1) (2).

14

attempts to include in its labor bill any changes in the exist

ing secondary boycott provisions, 2 Leg. Hist. 1071-86; 2

Leg. Hist. 1193-98. In the House, the proposed changes were

faring better, and the Landrum-Griffin bill, containing the

“threaten, coerce or restrain” provision, was receiving con

siderable support. Throughout the debates in the House,

the bill’s sponsors assured the House that the bill was de

signed only to close certain carefully identified “loopholes”

in § 8(b) (4), and that the “threaten, coerce or restrain”

formula, in particular, was designed only to meet direct

threats by the Union to a neutral employer to exert eco

nomic pressure on that neutral employer.9

On the eve of the critical House vote on the bill, President

Eisenhower spoke to the nation in support of its passage. In

the course of that speech, he told of an incident in which

picketers asked customers not to patronize a retail store car

rying goods manufactured by the employer with whom the

Union had a dispute. Representative Brown, on the floor of

the House, recalled this speech and asked Representative

Griffin whether his bill would prohibit such conduct. Grif

fin, observing that “of course, this bill and any other bill is

limited by the Constitutional right of free speech,” opined

that his bill would reach secondary consumer picketing if its

purpose “is to coerce or to restrain the employer of that sec

ondary establishment” (Emphasis added).10 Griffin further

emphasized the limited reach of his bill in response to the

next question, which concerned the impact of § 8(b) (7)

upon consumer picketing in support of an organizing drive.

Griffin cautioned:

“Unless the picketing is for the coercive purpose indi

cated, it would not be affected by this language. In

other words, whether it is the handing out handbills or

putting an ad in the paper or picketing, if it is done in

9 See, e.g., Remarks of Representatives Landrum, Griffin and

Rhodes, supra, n. 8.

10 2 Leg. Hist. 1615(2).

15

such a way so as clearly to be nothing more than an ex

ercise of free speech then the provision would not be

violated.” 11

The House passed the Landrum-Griffin bill two days

later, 2 Leg. Hist. 1701-02. Griffin’s comment was the only

reference in the House to the applicability of the bill to con

sumer picketing. The Board, in relying on the Griffin quote,

has overlooked the qualifications which Griffin himself im

posed : that the bill would reach only picketing which is co

ercive or restraining of the secondary establishment, and that

to go further would raise serious Constitutional questions.

The House and Senate then went into conference to re

solve the differences in their bills. There was, of course, a

substantial conflict with respect to 8(b) (4), for the Senate

bill contained no changes, while the House bill contained the

“threaten, coerce or restrain” formula. Griffin’s last-min

ute revelation that his bill would reach coercive publicity

directed against a secondary establishment became the focal

point of the conference discussions. A majority of the Sen

ate conferees were strongly opposed to outlawing any pub

licity, even “coercive” publicity. Accordingly, they pro

posed a proviso which would exclude from regulation “pub

licity for the purpose of truthfully advising the public” 2

Leg. Hist. 1382.

The Senate and House disagreement was ultimately re

solved in conference by whittling down the proviso to “pub

licity, other than picketing, for the purpose of truthfully ad

vising the public.” The effect of this change was to retain

the House bill’s ban on “coercive” picketing, even though it

is publicity.

Senator Kennedy, in his report to the Senate on the results

of the conference, twice stated that the proviso would not

protect consumer picketing in front of retail stores [1389

(1), 1432(1)]. Taken out of context, as the Board has

11 2 Leg. Hist. 1615(3).

16

taken them, these statements would suggest that Congress

had outlawed all consumer picketing. But Senator Ken

nedy’s remarks were directed only to the proviso, which was

not designed to create new restrictions, but rather to narrow

the impact of 8 (b )(4 )(h ). And the Board overlooks the

explanation given by Senator Goldwater, a fellow conferee

and an ardent supporter of § 8(b) (4) (ii), in which he

makes clear that § 8(b) (4) (ii), as finally drafted in con

ference, is directed only at picketing which asks consumers

not to patronize the secondary establishment:

“This new amendment in the conference report also

makes secondary consumer boycotts illegal subject to

certain narrow and limited exceptions. Thus, under

previous law a labor union having a dispute with the

producer, company A, could lawfully picket the dis

tributor, company B, who carried company A’s prod

ucts for sale, for the purpose of inducing consumers not

to patronize company B, subject to certain restrictions

imposed by the Board. Under the new amendment,

such picketing becomes illegal . . . ” 2 Leg. Hist. 1857

(2) (Emphasis supplied).

In the absence of affirmative evidence that a single Con

gressman intended to outlaw all consumer picketing by the

language of § 8(b) (4) (ii) itself, it is bootstraps reasoning to

infer such an intent from the statements of Senator Kennedy,

the sponsor of a proviso which was originally designed to ex

empt even coercive picketing from regulation.

The Board also seeks support for its position from the “lit

eral wording” of the proviso, which is:

“for the purposes of this paragraph (4) only, nothing

contained in such paragraph shall be construed to pro

hibit publicity, other than picketing, for the purpose of

truthfully advising the public, including consumers and

members of a labor organization, that a product or

products are produced by an employer with whom the

17

labor organization has a primary dispute and are dis

tributed by another employer, as long as such publicity

does not have an effect of inducing any individual em

ployed by any person other than the primary employer

in the course of his employment to refuse to pick up,

deliver, or transport any goods, or not to perform any

services, at the establishment of the employer engaged

in such distribution;”.

With dubious logic, the Board concludes that since pick

eting is not exempted by the proviso, it necessarily violates

§ 8(b) (4) (ii). This is backwards reasoning. Picketing

directed against the retail stores, and asking customers not to

patronize those stores, might be “coercive,” and, if so, the

proviso will not save it simply because it is publicity. But in

this case, no such coercion of the retail stores occurred. The

action called for by the picketing was a refusal to buy Per

fection products, not a refusal to patronize the stores. If

picketing would not violate § 8(b) (4) (ii) because it is not

coercive, surely the proviso would not make it unlawful.

The Board’s reasoning has been rejected by the one Court

which has thus far interpreted § 8(b) (4) (ii). In Fruit and

Vegetable Packers v. N.L.R.B., —F. 2d —, 50 LRRM 2392,

2394 (D.C. Cir. 1962), the Court said:

“Looking solely to the language of the statute . . .

we believe the most plausible reading to be that § 8(b)

(4) (ii) outlaws only such conduct (including picket

ing) as in fact threatens, coerces or restrains secondary

employers, and that the proviso is intended to exempt

from regulation ‘publicity other than picketing’ even

thought it threatens, coerces or restrains an employer.

. . . Perhaps the Board’s view—-that the proviso re

flects the draftsman’s assumption that without it all

secondary publicity is banned because it necessarily

threatens, coerces or restrains a secondary employer—

can be squared with the statutory language. But that

18

appears to be a less plausible reading of the statute.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

§ 8(b) (4) (ii) as enacted outlaws not “picketing,” but

“coercion and restraint.” The Board argues that despite

this language all peaceful consumer picketing at a secondary

site is outlawed per se, relying on the legislative history. As

we have shown, a few isolated remarks pulled from their

context might be read to support the Board’s contention.

But viewed in context, these statements are consistent with

the entire legislative history, which clearly indicates that

only consumer picketing which is in fact “coercive” or “re

straining,” in that it invites consumers to boycott the sec

ondary store, is outlawed.

Surely a clearer expression of legislative intent should be

required before a Court will turn the language of a statute

on its head as the Board has done here, especially in the face

of the clear implications of such a course. As the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia warned, in Fruit and

Vegetable Packers:

“In analyzing the legislative history . . . we must be

ever mindful that we do a disservice to Congress if we

construe the statute on the basis of the legislative his

tory in a manner which would raise serious constitu

tional questions. Particularly is this so where there is

no elucidating House, Senate or Conference report on

the precise point involved, and where one of the spon

sors of the legislation made clear the desire to avoid

constitutional questions.” 50 LRRM at 2394.

We believe the interpretation of the statute by the Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia in Fruit and Vege

table Packers is correct:

“Viewed as a whole, the statute does not reflect Con

gress’ intent to ban all secondary consumer picketing.

What Congress has said is that it shall be an unfair

labor practice for a union ‘to threaten, coerce, or re

19

strain any person engaged in commerce . . . where . . .

an object thereof is . . . forcing or requiring any per

son to cease . . . selling . . . the products of any

other producer.’ Each of these terms has a meaning;

each must be given effect. None can be ignored to be

repealed by reference to the legislative history. It is

significant that when Congress wanted to outlaw pick

eting per se, it knew how to do so, as is evidenced by

§ 8(b) (7), which forbids a union in certain circum

stances ‘to picket or cause to be picketed any employer’

if its object is to force him to recognize an uncertified

union.

“As we construe the statute, it condemns not picket

ing as such, but the use of threats, coercion and re

straint to achieve specified objectives. Some picketing

might come within the ambit of that prohibition. But

here, there was no work stoppage, no interruption of

deliveries, no violence or threat of violence. The record

does not show whether pickets ‘confronted’ consumers

or whether consumers felt ‘coerced’ by their presence.

Nor does the record show that the picketing—directed

against only one of hundreds of products sold by Safe

way—caused or was likely to cause substantial eco

nomic injury.”

2. If In terpreted to Prohibit, Per Se, Consum er Picketing in

Front of Secondary Establishments, § 8(b)(4 )(H ) Unconstitu

tionally Infringes upon Freedom of Speech.

The Supreme Court long ago established that picketing

is a form of speech protected by the First Amendment.

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940). But the Su

preme Court has subsequently taught that in some circum

stances picketing may involve “more than publicity,” and in

such cases the non-publicity aspects of picketing make it

regulable where “pure” speech might not be. Teamsters v.

Vogt, 354 U.S. 284 (1957); and see cases cited in Wooten v.

20

Ohler, — F. 2d —, 50 LRRM 2446, 2449, n. 9 (5 Cir.

1962).

As this Court recently noted, the application of the First

Amendment to picketing is often “complex,” resulting from

the “inherent, intrinsic uncertainty of what does or does not

constitute civil rights protected picketing,” Wooten v. Ohler,

supra, 50 LRRM at 2450. But we believe the Supreme

Court’s decisions can be harmonized, and a workable rule

derived therefrom, if they are placed in proper historical

perspective, and if the distinction between “consumer” and

“signal” picketing, only occasionally articulated in the

Court’s opinions, is made clear.

Consumer picketing is one means whereby a union may

publicize the facts of a labor dispute, and thereby com

municate its ideas to the public. If conducted peacefully,

as here, it neither intimidates customers nor induces sec

ondary employees.

By contrast, “signal” picketing is more than a means of

communication. It is a device aimed at unionized employ

ees, designed to induce them to quit work or stop deliveries.

And, in these circumstances, “the very presence of a picket

line may induce action of one kind or another, quite irre

spective of the nature of the ideas which are disseminated,”

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U.S. 769, 776 (1942)

(Douglas, J., concurring).

“The response to which Mr. Justice Douglas referred

is characteristic of unionized employees to whom pick

ets have traditionally addressed their appeal. Such

employees are subject to group discipline based on com

mon interests and loyalties, habit, fear of social ostra

cism, or the application of severe economic sanctions.

Hence, they may refuse to work or to make pickups and

deliveries for a secondary employer, thereby causing

him serious and immediate economic injury. See Cox,

Strikes,PicketingandThe Constitution, 4 Vand. L. Rev.

574, 594 (1951). In that context, picketing is more

21

than ‘pure’ speech.” Fruit and Vegetable Packers,

supra, 50 LRRM at 2395.

Here, the picketing was directed only to consumers. The

Board in finding that § 8(b) (4) (i) was not violated has

conclusively determined that the union did not induce, nor

seek to induce, secondary employees to quit work or stop de

liveries. Indeed, the Union affirmatively and effectively,

sought to prevent its picketing from having any “signal”

effect on employees, by avoiding any picketing at employee

entrances, by avoiding picketing while employees entered

and left the store at the start and finish of their work day,

and by addressing its picket sign “To the Consuming Public.”

This, then, was not “signal” picketing.

In reviewing the Supreme Court’s opinions, this distinc

tion becomes important. For, as we shall show, the original

equation of “picketing” with “speech” developed in a series

of consumer picketing cases; the later classification of “pick

eting” as “more than speech,” came in a series of signal

picketing cases, in which the Court for the first time saw the

non-communicative influences which picketing directed at

unionized employees can exert; and, finally, in some recent

cases, the Court has begun to realize that the broad term

“picketing” encompasses two essentially different types of

conduct deserving of very different degrees of constitutional

protection.

In Thornhill, and in Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106

(1940), decided the same day, the Court made clear that

peaceful picketing was in its view fully protected speech:

“The carrying of signs and banners, no less than the

raising of a flag, is a natural and appropriate means of

conveying information on matters of public concern . . .

[Publicizing the facts of a labor dispute in a peaceful

way through appropriate means, whether by pamphlet,

by word of mouth or by banner, must now be regarded

as within the liberty of communication which is se

22

cured to every person by the Fourteenth Amendment

against abridgement by a State.” Carlson v. California,

310 U.S. at 112-13.

As is clear from these opinions, the Court was viewing

picketing as a means of communicating with the public, and

its sweeping statements about the protections due “picket

ing,” although not qualified in the opinion, were really di

rected to consumer picketing. In a section of the Thornhill

opinion entitled “Third,” the Court set out its conception of

‘picketing,” and it is clearly consumer picketing:

“Section 3448 has been applied by the state courts so

as to prohibit a single individual from walking slowly

and peacefully back and forth on the public sidewalk in

front of the premises of an employer, without speaking

to anyone, carrying a sign or placard on a staff above

his head stating only the fact that the employer did not

employ union men affiliated with the AFofL; the pur

pose of the described activity was concededly to advise

customers and prospective customers of the relationship

existing between the employer and its employees and

thereby to induce such customers not to patronize the

employer. . . . The statute as thus authoritatively con

strued and applied leaves room for no exceptions based

upon either the number of persons engaged in the pro

scribed activity, the peaceful character of their de

meanor, the nature of their dispute with an employer,

or the restrained character and the accurateness of the

terminology used in notifying the public of the facts of

the dispute.” 310 U.S. at 98-99 (Emphasis supplied).

The sweeping language of Thornhill and Carlson was re

iterated in the next case to reach the Court, also involving

consumer picketing, AFofL v. Swing, 312 U.S. 321 (1941).

But in Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Ritters’ Cafe, 315

U.S. 722 (1942), the Court first saw that picketing could

have potentialities transcending pure speech. There a picket

23

line induced secondary employees to stop work and truck

men to refuse to deliver. Branding this conduct “exertion of

concerted pressure,” the Court held that it could be regu

lated by the State.

Simultaneously with Ritter’s Cafe, the Court struck down

state regulation of consumer picketing which was virtually

identical to that in this case, Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl,

315 U.S. 769 (1942). The Court did not articulate a dis

tinction between the “signal” picketing in Ritter’s Cafe and

the consumer picketing in Wohl, but the opposite results in

the two cases suggest that this distinction may have under

lied the Court’s thinking even then.

There followed a series of cases in which the Court al

lowed State regulation of signal picketing. In Giboney v.

Empire Storage, 336 U.S. 490 (1949), truckers were told by

picketers that if they crossed the picket line they would lose

their union membership; in Teamsters v. Hanke, 339 U.S.

470 (1950), truckers refused to cross the picket line; in

Building Service Union v. Gazzam, 339 U.S. 532, 540, the

Court decried the picketing which had “far more potential

for inducing action or inaction than the message the pickets

convey” ; in Electrical Workers v. N.L.R.B., 341 U.S. 694

(1951), the Court upheld regulation of signal picketing

under § 8(b) (4) (A) of Taft-Hartley; and finally, in Team

sters v. Vogt, 354 U.S. 284 (1957), the Court upheld state

regulation of picketing which induced truckers to refuse to

deliver.

The opinions in these cases do not articulate a distinction

between consumer and signal picketing. Indeed frequently,

in language as broad as Thornhill, they suggest that all pick

eting has the elements making it “more than speech.”

But of late the Court has evidenced in two opinions that

its post-Thornhill opinions, like Thornhill itself, were worded

too broadly. In Plumbers Union v. Graham, 345 U.S. 192,

200 (1953), the Court upheld state regulation of picketing

which induced secondary employees to stop work. Yet its

24

opinion suggests that picketing which did not contain the

“signal” aspect would be pure speech:

“Petitioners here engaged in more than the mere pub

lication of the fact that the job was not 100% Union.

Their picketing was done at such a place and in such a

manner that, coupled with established union policies

and traditions, it caused the Union men to stop work

and thus slow the project to a standstill.”

And, in Chauffeurs v. Newell, 356 U.S. 341 (1958), the

Court struck down a State Court injunction against peaceful

consumer picketing. This is the Supreme Court’s most

recent pronouncement in the labor-picketing field, following

all the broadly worded signal picketing decisions, and its sig

nificance is evident. The Union had engaged in consumer

picketing in front of a retail dairy. The picketing had been

effective, and a number of the dairy’s largest customers had

ceased doing business with it. The Kansas Supreme Court

had upheld an injunction against the picketing, 181 Kan.

898, 317 P. 2d 817 (1957), finding the picketing ‘ ‘coercive”

of both the dairy and its customers. A petition for rehear

ing had been denied, 182 Kan. 205, 319 P. 2d 171 (1958).

The Supreme Court summarily reversed, citing “Thorn

hill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 98 Third.” The Third section

of Thornhill, from which we have quoted supra, at p. 22

of this brief, declares that consumer picketing is constitution

ally protected speech.

This Court has recently commented that “the protection

afforded picketing has changed considerably since the broad

pronouncements in Thornhill,” Wooten v. Ohler, 50 LRRM

at 2449. But a review of the Supreme Court’s opinions re

veals that though the broad language of Thornhill has not

been followed in cases involving “signal” picketing, Thorn

hill apparently retains its original vitality in the area of con

sumer picketing.

25

The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia noted

this in Fruit and Vegetable Packers:

“[I]t may well be that the picketing in this case is

closer to the core notion of constitutionally protected

free speech than the picketing the Supreme Court has

held may be banned.”

See also, to the same effect, Cox, Strikes, Picketing and the

Constitution, 4 Vand. L. Rev. 574, 594 (1951); Samoff, Pick

eting and the First Amendment: “Full Circle” and “Formal

Surrender" 9 Lab. L.J. 889 (1958); Note, 107 U. Pa.L.

Rev. 127 (1958).

The growing awareness of the distinction between signal

and consumer picketing is more than coincidence. For in

the past decade legal restraints on signal picketing, particu

larly § 8(b) (4) (A) of Taft-Hartley which makes secondary

signal picketing unlawful (see Electrical Workers v. NLRB,

341 U.S. 694 (1951)), have forced unions to re-examine

their picketing conduct. Whereas in the past unions directed

their picketing appeals indiscriminately at both employees

and the public or even exclusively at employees, they have

now learned to channel their picketing away from employees

and exclusively toward the public. There has accordingly

developed, quite recently, increased use of “pure publicity”

picketing, and the Courts and commentators have been quick

to recognize the difference.

Of course, even picketing which is “pure speech,” and en

titled to the same protections as other forms of speech, may

be regulated in very extreme cases, when the “gravity of the

evil” the legislature seeks to prevent, discounted by its im

probability, justifies “such invasion of free speech as is nec

essary to avoid the danger,” Dennis v. United States, 341

U.S. 494, 510 (1951), or as stated by Justice Holmes, when

there is a “clear and present danger” of “substantive evils

that Congress has a right to prevent,” Schenck v. United

States, 249 U.S. 47,52 (1919).

26

But however stated, the Constitution allows suppression of

speech only when it threatens to bring about an “evil” which

Congress has the “right” to prevent. Here, the consumer

picketing might conceivably have two effects: (1) it might

induce customers to boycott Perfection products; (2) it

might thereby indirectly motivate retail stores to stop han

dling Perfection’s goods. It is doubtful that Congress could

constitutionally prohibit either of these effects. The con

sumer’s right not to patronize, and the retailer’s right not to

carry products which do not sell, would both seem beyond

the reach of restrictive legislation. And if Congress cannot

regulate these ends, neither can it regulate speech directed at

these ends, Fruit and Vegetable Packers, supra, cf. Lebus v.

Building and Construction Trades, 199 F. Supp. 628 (E.D.

La. 1961). But these questions need not be reached. For

Congress has not declared the effects here “evils” in them

selves. Indeed, in the proviso to § 8 (b) (4) it has specifically

approved “publicity, other than picketing” designed to bring

about these ends.

Thus § 8(b) (4) (ii), if construed to outlaw secondary

consumer picketing per se, would be prohibiting one form of

speech while allowing other forms advocating the very same

end. This Congress cannot do, Carlson v. California, supra.

And this Congress did not intend to do. We again recall

Representative Griffin’s words concerning § 8(b) (7) :

“[Wjhether it is the handing out handbills or putting an

ad in the paper or picketing, if it is done in such a way

so as clearly to be nothing more than an exercise of free

speech then the provision would not be violated.”

II. THE ORDER SHOULD NOT BE MODIFIED

Perfection and Burr, in their petition, seek modification

of the Board’s order to specifically prohibit consumer picket

ing. As we have shown, the Board’s order should be set

aside, and accordingly in our view this request is moot.

But even if the Board’s opinion were sustained no modi

27

fication of the order would be appropriate. For the Board’s

order recites the language of the statute, and if the statute

reaches the picketing in this case, manifestly the Board’s

order does as well.

CONCLUSION

The Union respectfully submits that the Board’s order

should be set aside,12 and Perfection and Burr’s request that

the order be modified should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

D avid E . F eller

E lliot B r e d h o f f

J erry D . A n k e r

M ic h a e l H. G o t t e s m a n

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.

J erom e A. C ooper

C ooper , M it c h & C raw ford

1329 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham 3, Alabama

12 In Fruit and Vegetable Packers, the Court of Appeals for the Dis

trict of Columbia remanded the case to the Board for the taking of evi

dence as to whether the picketing in fact coerced or restrained the sec

ondary stores. We submit that that disposition is improper. If the

Board has failed to introduce competent evidence to sustain its com

plaint, its order should be set aside. § 10(e) of the Act authorizes the

taking of additional evidence only upon a showing that “there were

reasonable grounds for the failure to adduce such evidence in the hear

ing before the Board.” No reasonable grounds have been suggested

here. Cf. NLRB v. Fournier, 182 F. 2d 621 (2 Cir. 1950).