Defendants-Appellees' Motion for Time to Respond

Public Court Documents

May 12, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Defendants-Appellees' Motion for Time to Respond, 1988. 25bae037-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16dd58a6-dff2-48b5-916e-3e339ddd73f9/defendants-appellees-motion-for-time-to-respond. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

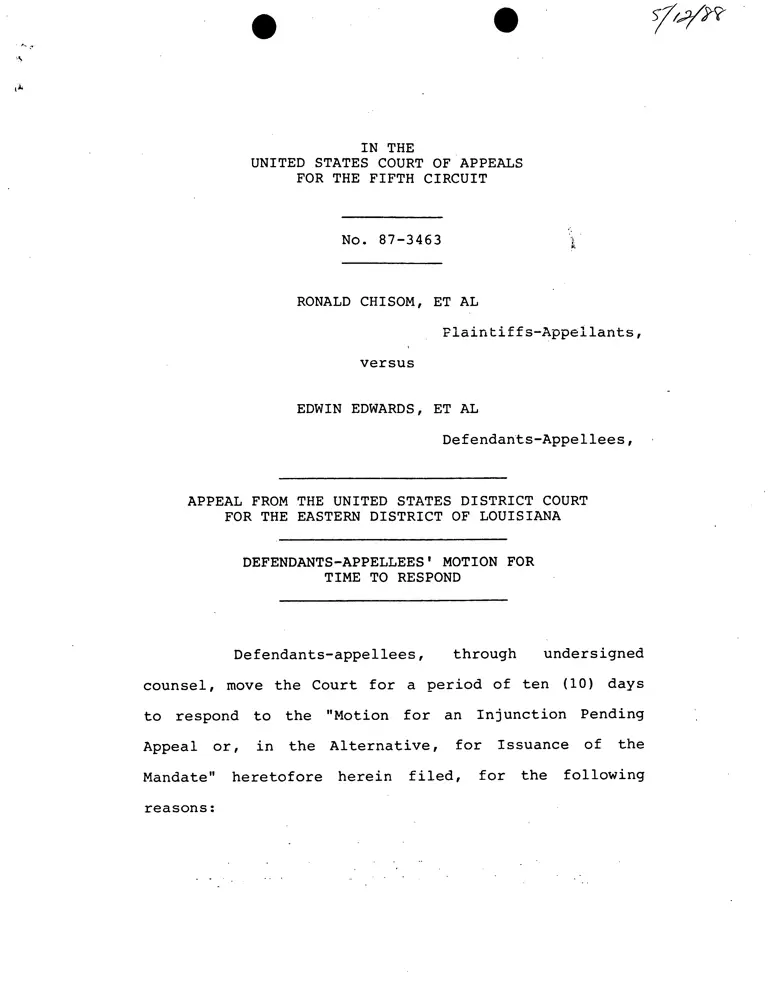

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL

Defendants-Appellees,

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES' MOTION FOR

TIME TO RESPOND

Defendants-appellees, through undersigned

counsel, move the Court for a period of ten (10) days

to respond to the "Motion for an Injunction Pending

Appeal or, in the Alternative, for Issuance of the

Mandate" heretofore herein filed, for the following

reasons:

(.•

2

1.

On yesterday, May 11, 1988, lead counsel for

the defendants-appellees received a copy of the

plaintiffs-appellants "Motion for an Injunction Pending

Appeal Or, in the Alternative, for Issuance of the

Mandate" [the "Motion"].

2.

Rule 27 of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure states that "motions authorized by Rules 8

. [inter alia] may be acted upon after reasonable

notice, and the court may shorten or extend the time

for responding to any motion."

3.

Counsel for defendants-appellees submits that

defendants-appellees should be granted ten (10) days to

respond to the Motion received yesterday. Such a ten

(10) day period will be necessary because of the

unusual and complexity of the request posed and because

the motion appears to conflict with Rule 41 of the

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure.

4.

The procedural story of this case is a short

one. After the filing of a complaint, a Rule 12(b)(6)

motion was filed and favorably considered by the court

below. No evidence was considered necessary or

permissible for purposes of this motion. An appeal to

this court timely perfected was followed by a reversal

and remand. Both a motion for rehearing by the panel

and a suggestion for rehearing en banc were filed.

Neither of these have been acted upon.

5.

Out of this procedural history, and without

consideration of the factual vacuum in which this case

now lies, the plaintiffs-appellants would seek

extraordinary relief here of an injunction to prohibit

Louisiana from the exercise of its most basic

governmental function - election of its judges, or,

alternatively, cause the immediate issuance of an

mandate prior to the completion of the procedural

remedies sought both before this panel and the full

court only so that the plaintiffs-appellants might be

provided with a judicial forum to immediately seek

injunctive relief.

6.

The jurisdictional and prudential problems

that plague the rights of the defendants-appellees to

4

present evidence in this case have been dramatically

exposed. The efforts of the plaintiffs-appellants to

secure from this Court summary-type relief, enuring to

the benefit of the plaintiffs-appellants underscore the

the propriety and advisability of granting to the

defendants-appellees an adequate opportunity to timely

and intellectually respond to plaintiffs-appellants

current motion.

Dated: May 12, 1988

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Louisiana Department of

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th

New Orleans, Louisiana

(504) 568-5575

M. TRUMAN WOODWARD, JR.

209 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 581-3333

BLAKE G. ARATA

201 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 582-1111

By:

Justice

Floor

70112

A. R. CHRISTOVICH

1900 American Bank Bldg.

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 561-5700

MOISE W. DENNERY

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1241

RO ERT G. PUGH

L-ad Counsel

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

(318) 227-2270

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEYS GENERAL

CERTIFICATE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the above and

foregoing motion for time to respond has this day been

served upon the plaintiffs through their counsel of

record:

William P. Quigley, Esquire

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Julius L. Chambers, Esquire

Charles Stephen Ralston, Esquire

C. Lani Guinier, Esquire

Ms. Pamela S. Karlan

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Roy Rodney, Esquire

643 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Ron Wilson, Esquire

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

by depositing the same in the United States Mail,

postage prepaid, properly addressed.

All parties required to be served have been

served.

Shreveport, Caddo Parish, Louisiana, this the

12th day of May, 1988.

Robert G. Pugh

Lead Counsel