Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

June 2, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs, 1989. e73ae9db-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16e28e6c-3f10-416e-b7dd-7629dd4a8d68/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

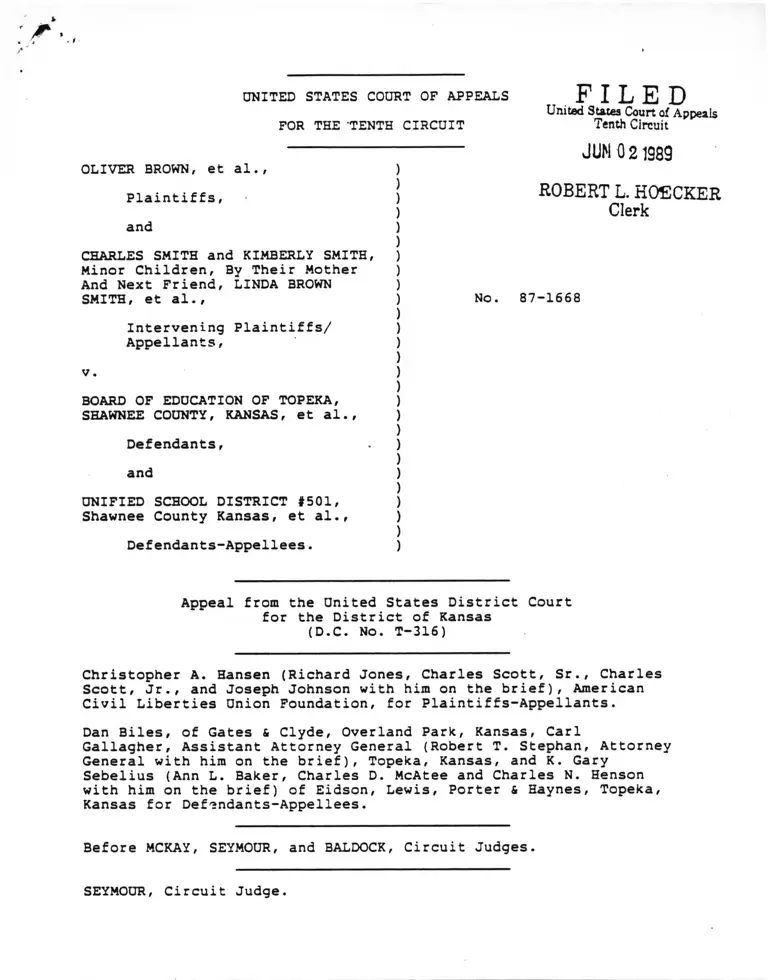

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE 'TENTH CIRCUIT

F I L E D

United States Court of Appeals

Tenth Circuit

OLIVER BROWN, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

and )

)

CHARLES SMITH and KIMBERLY SMITH, )

Minor Children, By Their Mother )

And Next Friend, LINDA BROWN )

SMITH, et al., )

)

Intervening Plaintiffs/ )

Appellants, )

)

v. )

)

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, )

SHAWNEE COUNTY, KANSAS, et al., )

)

Defendants, )

)

and )

)

UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT #501, )

Shawnee County Kansas, et al., )

)

Defendants-Appellees. )

JtIM 0 2 1989

ROBERT L. HDECKER

Clerk

No. 87-1668

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Kansas

(D.C. No. T-316)

Christopher A. Hansen (Richard Jones, Charles Scott, Sr., Charles

Scott, Jr., and Joseph Johnson with him on the brief), American

Civil Liberties Union Foundation, for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

Dan Biles, of Gates & Clyde, Overland Park, Kansas, Carl

Gallagher, Assistant Attorney General (Robert T. Stephan, Attorney

General with him on the brief), Topeka, Kansas, and K. Gary

Sebelius (Ann L. Baker, Charles D. McAtee and Charles N. Henson

with him on the brief) of Eidson, Lewis, Porter & Haynes, Topeka,

Kansas for Defendants-Appellees.

Before MCKAY, SEYMOUR, and BALDOCK, Circuit Judges.

SEYMOUR, Circuit Judge.

"[0]nce you begin the process of segregation, it has its own

inertia. It continues on without enforcement."1 This comment by

one expert on segregation in schools succinctly summarizes the

state of affairs in Topeka. As a former de jure segregated school

system, Topeka has long labored under the duty to eliminate the

consequences of its prior state-imposed separation of races.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955). The district

court concluded that Topeka has fulfilled that duty, and that the

school system is now unitary. Because we are convinced that

Topeka has not sufficiently countered the effects of both the

momentum of its pre-Brown segregation and its subsequent

segregative acts in the 1960s, we reverse. Specifically, we hold

that the district court erred in placing the burden on plaintiffs

to prove intentional discriminatory conduct rather than according

plaintiffs the presumption that current disparities are causally

related to past intentional conduct. We are convinced that

defendants failed to meet their burden of proving that the effects

of this past intentional discrimination have been dissipated. We

also reverse the district court's holding that the Topeka school

district has not violated Title VI. However, we affirm the

court's dismissal of the Governor of the State of Kansas and its

ruling that the State Board of Education bears no liability for

segregation in Topeka's schools. *

x Statement by Dr. William Lamson during trial. Rec., vol. II,

at 162-63.

-2-

LEGAL HISTORY

Prior to 1954, a Kansas statute permitted certain cities to

maintain separate schools for white and black children below the

high school level. In 1941, however, the Kansas Supreme Court

held segregation in Topeka's junior high schools to be

unconstitutional. See Graham v. Board of Education, 114 P.2d 313

(Kan. 19-41) (separate facilities not equal). Topeka was thus

legally permitted to operate segregated schools only at the

elementary level. The Topeka Board of Education operated such a

system. In 1951, black citizens of Topeka filed a class action

challenging the constitutionality of the Kansas law authorizing

school segregation. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) (Brown I ), followed, beginning a new era of American

jurisprudence by bringing an end to the doctrine of "separate but

equal" and declaring segregation unconstitutional.

The Topeka Board of Education did not wait for the decision

in Brown I before taking steps towards desegregating Topeka's

elementary schools. It began that process in 1953 by permitting

black students to attend two formerly all-white schools. It then

gradually increased the number of schools black students might

attend. Accordingly, when the Supreme Court considered the

question of the relief appropriate in school desegregation cases,

it noted that "substantial progress" had already been made in

I .

-3-

Topeka. ■ Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 299 (1955)

(Brown II). On remand, the district court criticized one aspect

of the Board's desegregation plan but described it overall as "a

good faith effort to bring about full desegregation in the Topeka

Schools in full compliance with the mandate of the Supreme Court."

Brown v. Board of Education, 139 F. Supp. 468, 470 (1955). The

court retained jurisdiction of the case, and the decision was not

appealed.

Nineteen years later, in 1974, the Office of Civil Rights

(OCR) of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW)

notified the Topeka school district that it was not in compliance

with section 601 of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.2

After the Topeka Board of Education failed to adopt a plan

designed to remedy the noncomplying conditions identified by OCR,

HEW began administrative enforcement proceedings against the

Topeka school district. The Board filed suit in federal court and

obtained a preliminary injunction against the administrative

proceeding on the ground that the district court's 1955 decision

was a final order, and that the school district was still

z Section 601 states:

"No person in the United States shall, on the ground of

race, color, or national origin be excluded from

participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be

subjected to discrimination under any program or

activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

42 U.S.C. S 200d (1982). The Topeka school district received

federal funds through the Kansas State Department of Education.

-4-

operating under that court order and still subject to the court's

jurisdiction. HEW was thereby precluded from taking

administrative action. See generally Brown v. Board of Education,

84 F.R.D. 383, 390-91 (D. Kan. 1979). In 1976, the Board

submitted a plan acceptable to HEW, and both the administrative

proceeding and the suit in federal court were dismissed. The

Board implemented the plan over the next five years.

In 1979, a group of black parents and children sought to

intervene in Brown as additional named plaintiffs on the ground

that they were members of the original class and that the original

named plaintiffs no longer had a sufficient interest in the matter

to represent their interests. The intervenors asserted that

Topeka has failed to desegregate its schools in compliance with

the Supreme Court's mandate, and that the Topeka school district

currently maintains and operates a racially segregated school

system. Their request to intervene was granted.-* See Brown, 84

F.R.D. 383. A long discovery and motion stage followed the

granting of the intervenors' motion.

Trial took place in October 1986. The court found the Topeka

school district to be an integrated, unitary school system. Brown

v. Board of Education, 671 F. Supp. 1290 (D. Kan. 1987). The

court also held that the Topeka school district had not violated

Linda Brown, a child named plaintiff in the original suit, is

now the mother of two intervening child plaintiffs.

-5-

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, dismissed the Governor

of Kansas from the case, and found that the State Board of

Education bore no liability for racial conditions in the school

district. This appeal followed.

II.

BRIEF FACTUAL HISTORY

A. Population Change

In 1950, Topeka's population was approximately 10% black.

While Topeka's population grew significantly until 1970 and then

dropped, the black percentage of the population remained

approximately the same. The Hispanic population of Topeka has

been slightly less than 5% since 1970. Other minorities make up

less than 1.5% of the population.

The distribution of Topeka's population has changed more

significantly than its composition. In general, the outer parts

of Topeka, particularly on the western side, have grown

considerably in population, while the inner city has declined.

Until recently, the western side of Topeka was almost exclusively

white. The black population of Topeka was concentrated in a few

areas in the center of the city in the 1950s; it has since spread

widely throughout the eastern part of the city and has gradually

begun to move into the western side of Topeka.

-6-

The percentage of black and minority children in the Topeka

schools has long been higher than the percentage of blacks and

minorities in the Topeka population as a whole and has risen over

time. In 1952, black students constituted 8.4% of the total

number of students in Topeka. By 1966, the percentage of black

students in the Topeka school district was 11.6% and the

percentage of minority students was 16.0%. In 1975, black

students constituted 14.7%, and minority students 20.9%, of the

school population. The latest figures used at trial, those for

the 1985 school year, showed 18.4% black and 25.95% minority

children in the system.

B. Elementary Schools

In 1951, four Topeka elementary schools were reserved for

black children. Eighteen elementary schools educated white

children. Black children were bused to their schools; white

children attended neighborhood schools. 671 F. Supp. at 1291.

Under the four-step plan approved by the district court in 1955,

all elementary schools were to be opened by September of 1956 to

black and white children under a neighborhood school policy. Id.

at 1293.

During the late 1950s, the school district acquired by

annexation the Avondale (outer Topeka, south) and Highland Park

-7-

(middle and outer Topeka, east) school districts as well as other

territory on the edges of the district. Existing schools within

the acquired area were either primarily white or primarily black.

As school enrollments grew and the population began to shift, the

school district began to close elementary schools in the inner

part of the city and open them in the rapidly growing outer part

of the city. Three of the closed schools were former de jure

black schools (McKinley, Buchanan, and Washington). The new

schools were built in the newly acquired white areas and opened

with all or virtually all white students.

Racial statistics were not kept in an organized fashion from

1956 to 1966. In 1966, the school district operated thirty-five

elementary schools. There were some white students in every

school. Minority students were present in thirty-two schools.

Nineteen of the schools were 90+% white. An additional seven

schools were 80-90% white. Four schools were more than 50%

minority, and a fifth was almost 50%. The highest percentage of

minority students was 93.1% (Parkdale), and the lowest was 0%

(Lyman, McEachron, and Potwin). Sixty-five percent of white

students attended 90+% white schools and an additional 18.7%

attended 80-90% white schools. Close to half of all minority

students attended 50+% minority schools.4

4 Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 54-56. The record on appeal consists

of pleadings, transcripts, and exhibits. We cite them

respectively as "Rec., doc. #," "Rec., vol. #," and "Rec., ex.

vol. #".

-8-

A second major reorganization of the elementary schools took

place in the late 1970s, under the plan approved by HEW. Eight

elementary schools closed over a six-year period, including the

last of the four former de jure black schools (Monroe). In

September 1982, when the reorganization had ended, minority and

white students were present in each of the district's twenty-six

elementary schools.5 Five schools were 90+% white, and another

seven were 80-90% white. Four schools were 50+% minority, two of

them were schools that had been 50+% minority since 1966. The

highest percentage of minority students was 60.6% (Highland Park

North), and the lowest was 3.4% (McClure). Close to one-quarter

of all white students attended the 90+% white schools, and another

third attended 80-90% white schools, totalling 58% overall. The

percentage of minority students in 50+% minority schools was

35.5%.6

With one or two exceptions, the relative percentages of white

and minority students in the elementary schools have changed only

by two or three percentage points since that time. The most

significant change is that the schools with the highest white

percentages have gained some minority students. Thus, in 1985,

Lyman elementary school had been deannexed in 1967. Rec.,

vol• III, at 281.

6 Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 134-38.

-9-

the lowest percentage of minority students in any school was 7.2%

(McClure).7

C. Secondary Schools

In 1954, the Topeka school district operated six junior high

schools and one high school. Two schools were 90+% white, and

three were 80+% white. The estimated percentage of black students

at the junior high schools ranged from 1.7% (Roosevelt) to 30%

(East Topeka).®

7

Percentage of Minority Students

In Topeka Elementary Schools In 1985

School % School %

Avondale East 44.1 Lundgren 15.8

Avondale West 16.6 McCarter 9.2

Belvoir 61.9 McClure 7.2

Bishop 10.5 McEachron 10.3

Crestview 8.9 Potwin 7.7

Gage 9.4 Quincy 20.5

Highland Park Central 35.1 Quinton Heights 49.4

Highland Park North 57.9 Randolph 14.8

Highland Park South 28 Shaner 20.7

Hudson 46.55 State Street 26.3

Lafayette 56.8 Stout 26.8

Linn 29.4 Sumner 31.5

Lowraan Hill 41.9 Whitson 10.2

27.2% of all elementary students in 1985 were minorities.

Source: Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 170-74.

8 Rec., vol. Ill, at 306-07. Plaintiffs' expert Lamson used

the figures for black rather than minority students in his

analysis and testimony. Where we repeat his figures, we therefore

refer to black students and white students. We also refer to

black students when we discuss pre-1966 numbers, as it is only in

that year that figures begin to be available for minority students

-10-

_ During the late 1950sjrearly 1960s period of annexations and

building, two junior high schools joined the school system, and

three junior highs.were built. At the high school level, Highland

Park high school was annexed, and Topeka West high school was

built. All of these schools were in the newly acquired white

outer part of the school district and opened as white or primarily

white schools. 671 F. Supp. at 1299.

In 1966, there were thus eleven junior high and three high

schools. At that time, the average minority percentage for the

junior high and high schools was 15.3% and 14.9%, respectively.* 9

Of the junior highs, five had 90+% white students and another

three had 80-90% white students; one had 50+% minority students.

The highest percentage of minority students at one school was

61.8% (East Topeka), and the lowest percentage was 0% (Capper).

Of the high schools, Topeka High was nearly one-quarter minority,

Highland Park High had close to 15% minority students, and Topeka

West had .4% minority students. French junior high school opened

in 1970 in the southwestern part of the school district as a

primarily white school. 671 F. Supp. at 1299.

generally. Otherwise we refer to minority students. See Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1 , 413 U.S. 189, 197 (1973). The parties are in

agreement that the difference in analysis between black students

and minority students is not significant in this case. Rec., vol.

IV, at 409-10; rec., vol. V, at 598, 602-03.

9 Rec., ex. vol. II, at 56-57.

-11-

The reorganization of the late 1970s under the HEW-approved

plan included the junior high schools. Two junior highs closed in

1975. In 1980, five more junior highs closed and two schools were

opened as the district shifted from a junior high (6-3-3) to a

middle school (6-2-4) format. In 1981, after the end of the

reorganization, there were six middle schools in the Topeka school

district. Two were 90+% white and one was 80-90% white. None

were 50+% minority. The highest percentage of minority students

was 45.7% (Eisenhower) and the lowest 5.5% (French). By 1985, the

relative percentages at some schools had altered by approximately

5%, but the pattern across the district had not changed.10 The

percentage of minority students at the three high schools was

39.8% (Highland Park), 32.5% (Topeka High), and 5.25% (Topeka

10

Percentage of Minority Students

In Topeka Secondary Schools in 1985

Middle Schools % High Schools_________ %

Chase 33.4

Eisenhower 48.7

French 6.2

Jardine 17.3

Landon* 9.3

Robinson 28.5

Highland Park 33.6

Topeka High 30.9

Topeka West 7.9

The percentage of minority students in all middle schools was

26.9%, while the minority percentage at the high school level was

23.8%.

Source: Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 175-77.

*Landon is now closed.

-12-

West) in 1981, and 33.6% (Highland Park), 30.9% (Topeka High), and

7.9% (Topeka West) in 1985.

III.

THE PARTIES

All of the parties to this case have changed. The original

plaintiff children have long since left the Topeka school system.

The school district has been reorganized, and the State Board of

Education came into existence in 1969. These changes have

affected the posture of the litigation to some extent. The

original named plaintiffs represented black elementary school

children and their parents. Current named plaintiffs represent

black children throughout the school system and their parents.

The school district grew considerably in size as the city of

Topeka annexed territory, although the school district's

boundaries were fixed about 1960 while the city continued to grow.

The district was also renamed Unified School District # 501 as

part of a state-wide reorganization of school districts in 1965.

671 F. Supp. at 1292. The State Board of Education is the product

of a 1966 state constitutional amendment. Its powers differ

considerably from those of its predecessor. Id.; Brief for

Individually-Named Defendants Associated with the State Board of

Education at 1, 3-4.

-13-

IV.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF UNITARINESS

Unitariness is a finding of fact reviewed under the clearly

erroneous standard.^ Before we assess the status of school

desegregation in Topeka, we set forth the principles that guide

our consideration of the unitariness issue.

The district court defined a unitary school system as "one in

which the characteristics of the 1954 dual system either do not

exist or, if they exist, are not the result of past or present

intentional segregative conduct of" the school district. 671 F.

Supp. at 1293. These are necessary ingredients in a unitariness

determination, because once a violation is found, H[t]he Board has

. . . an affirmative responsibility to see that pupil [and

faculty] assignment policies and school construction and

abandonment practices 'are not used and do not serve to perpetuate

or re-establish the dual school system.'" Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 538 (1979) (Dayton II)

(quoting Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 460

1979). An additional essential requirement of unitariness, 11

11 See, e .q . , Riddick v. School Bd. of the City of Norfolk, 784

F .2d 521, 533 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. C t . 420 (1986);

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d 504, 506 (5th Cir.

1981), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1143 (1982); cf. Dayton Bd. of Educ.

v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 534 & n.8 (1979) (whether school

district is intentionally operating a dual school system is a

question of fact).

-14-

however, is whether "school authorities [have made] every effort

.to achieve the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation,

taking into account the practicalities of the situation." Davis

v. Board of School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971).

I

To determine whether a school district has become unitary,

therefore, a court must consider what the school district has done

or not done to fulfill its affirmative duty to desegregate, the

current effects of those actions or inactions, and the extent to

which further desegregation is feasible.* 13 After a plaintiff

establishes intentional segregation at some point in the past and

a current condition of segregation, a defendant then bears the

burden of proving that its past acts have eliminated all traces of

past intentional segregation to the maximum feasible extent.

A. Current Condition of Segregation

The actual condition of the school district at the time of

trial is perhaps the most crucial consideration in a unitariness

determination. The plaintiff bears the burden of showing the

See also Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq Bd. of. Educ., 402

D.S. 1, 26 (1971); Morqan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 322-25 (1st Cir.

1987).

13 C f . Morqan, 831 F.2d at 319 (considering number of one-race

or racially identifiable schools, good faith on the part of the

school district, and maximum practicable desegregation); Ross v.

Houston Indep. School Dist., 699 F.2d 218, 227 (5th Cir. 1983)

(considering conditions in district, accomplishments to date, and

feasibility of further measures).

-15-

existence of a current condition of segregation. The case law is

decidedly unclear as to the precise meaning of that term.14 In

our view, a plaintiff must prove the existence of racially

identifiable schools, broadly defined, to satisfy the burden of

showing a current condition of segregation. Racially identifiable

schools may be identifiable by student assignment alone, in the

case of highly one-race schools, or by a combination of factors

where the school is not highly one-race in student assignment.

Although virtual one-race schools "require close scrutiny,"

they are not always unconstitutional.1 ̂ Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburq Board of Education, 402 D.S. 1, 26 (1971). Their

The Supreme Court desegregation cases involved- school systems

in which the degree of segregation was sufficiently great that the

parties did not seriously dispute on appeal that the plaintiffs

had satisfied their burden on this issue. See Dayton II, 443 D.S.

at 529 (Dayton public schools "highly segregated by race"); Wright

v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 455 (1972) (complete

segregation); Swann, 402 U.S. at 24 (no challenge to finding of

prior dual system); Green v. County School Bd, of Educ., 391 U.S.

430, 435 (1968) (complete racial identification of schools). The

issue was potentially more significant in recent circuit cases in

which a school district had been under court order for some time

and many of the vestiges of prior de jure segregation had been

eliminated. Even in these more recent cases, however, no clear

standard has been articulated. See Morgan, 831 F.2d at 319-21

(considering number of one-race schools as part of unitariness

determination); Price v. Denison Indep. School Dist., 694 F.2d

334, 347-68 (5th Cir. 1982) (discussing need to consider various

factors in determining whether constitutionally violative

condition of segregation exists).

15 Given modern urban demography and geography, one-race schools

may well have evolved for reasons beyond school board control.

See, e .g ., Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 537 F.2d 800,

803 (5th Cir^ 1976); Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F.2d 717, 719 (5th Cir.

1975) .

-16-

existence in a system with a history of de jure segregation,

however, establishes a presumption that they exist as the result

of discrimination and shifts the burden of proof to the school

system. _Id. The presence of essentially one-race schools is thus

sufficient to satisfy a plaintiff's initial burden of showing a

current condition of segregation.

Courts have used various standards to define "one-race

schools."15 * Standards may appropriately differ from school

district to school district because the percentage of minority

students may likewise vary.17 18 * * Whatever the minority percentage

district-wide, however, it is clear that a school with 90+%

students of one race is a predominantly one-race school. °

ib See Morgan, 831 F.2d at 320 (listing standards ranging from

70% to 90% and declining to decide whether 80% or 90% is more

appropriate for Boston); Tasby v. Wright, 713 F.2d 90, 91 n.2, 97

n.10 (5th Cir. 1983) (90% standard for one-race schools; 75%

standard for predominantly one-race schools). Swann did not

define the term "one-race school," presumably because two-thirds

of Charlotte-Mecklenburg's black students attended schools that

were 99+% black. See Swann, 402 U.S. at 7.

17 See Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 320 n.7 (1st Cir. 1987)

(rejecting 75% standard in district 72% black); Castaneda v.

Pickard, 781 F.2d 456, 461 (5th Cir. 1986) (school 97.88% Mexican-

American not a vestige of discrimination in district 88% Mexican-

American); Ross, 699 F.2d at 220, 226 (affirming finding of

unitariness for district 80% minority although 57 out of 226

schools were 90+% one-race); Price, 694 F.2d at 336, 339-40

(schools not necessarily racially identifiable in district 88%

white although 7 out of 8 elementary schools 90+% white); Calhoun,

522 F .2d at 718-19 (85% black district unitary although more than

60% of schools all or substantially all black).

18 See Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 529 n.l; Milliken v. Bradley, 418

U.S. 717, 726 (1974); Ross, 699 F.2d at 226; Lee v. Macon County

Bd. of Educ., 616 F.2d 805, 808-09 (5th Cir. 1980).

-17-

Moreover, this is true whether the students at the school in

question are white or minority.^

Where racial imbalance in student assignment is still extreme

in a system that formerly mandated segregation, appellate courts

have reversed findings of unitariness without looking to other

factors.20 However, no particular degree of racial balance is

required by the Constitution.21 A degree of imbalance is likely

to be found in any heterogeneous school system. Therefore, the

existence of some racial imbalance in schools will often not be

conclusive in itself.

Where numbers alone are insufficient to define racially

identifable schools, courts look to demography, geography, and the

individual history of particular schools and areas of the city.22

See Morqan, 831 F.2d at 320; Tasby, 713 F.2d at 91 n.2; Ross,

699 fTIH at 226; Price, 694 F.2d at 364; Stout, 537 F.2d at 802.

20 See Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d at 508; c f . Lee v.

Tuscaloosa City School System, 576 F.2d 39 (5th Cir.) (per

curiam), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 1007 (1978); United States v.

Board of Educ. of Valdosta, Ga., 576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir.) (per

curiam) cert, denied ̂ 439 U.S. 1007 (1978); Carr v. Montgomery

County Bd. of Educ.~ 377 F.Supp. 1123, 1134 (M.D. Ala. 1974),

aff'd, 511 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.) (per curiam), cert, denied, 423

U.S. 986 (1975)..

21 See Milliken v. Bradley, 433 CJ.S. 267, 280 n.14 (1977);

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 434 (1976);

Swann, 402 U.S. at 24-26.

22 See Morgan, 831 F.2d at 320 (noting difficulty of further

desegregating schools located in geographically isolated or

heavily black sections of Boston); Price, 694 F.2d at 347-68

(authoritatively demonstrating that degree of racial balance is

-18-

While a multi-race school cannot be classified as racially

identifiable merely by tallying up the race of the students who

attend it, such a school may be racially identifiable "simply by

reference to the racial composition of teachers and staff, the

quality of school buildings and equipment, or the organization of

sports activities," among other factors. Swann, 402 D.S. at 18. J

These factors alone can establish a prima facia case of a

constitutional violation. Id. Therefore, a plaintiff may prove a

school to be racially identifiable by factors that may, but need

not, include student assignment.

B. The School District's Burden

Once a plaintiff has proven the existence of a current

condition of segregation, the school district bears the

substantial burden of showing that that condition is not the

result of its prior de jure segregation. Under the relevant

Supreme Court decisions, mere absence of invidious intent on the *

only one of many factors to be considered); Stout, 537 F.2d 800

(affirming remedy leaving three schools one-race because of

geographic isolation and barriers); c f . Carr, 377 F. Supp. at 1141

(criticizing formulas for determining racial balance as "highly

artificial" and severely disruptive).

^ See Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1 , 413 D.S. 189, 196 (1973)

(what is a segregated school depends on facts of the particular

case; faculty and staff percentages and community and

administrative attitudes as well as racial composition of student

body are relevant); Price, 694 F.2d at 347-68; United States v.

Lawrence County School Dist., 799 F.2d 1031, 1039-40 (5 th Cir.

1986) (looking to student and faculty percentages and history and

location of school).

-19-

part of the school district is not sufficient to satisfy its

"heavy burden" of proof; the district's duty is to act

affirmatively, not merely to act neutrally. Dayton II, 443 U.S.

at 538. The school district must show that no causal connection

exists between past and present segregation, not merely that it

did not intend to cause current segregation. The causal link

between prior and current segregation is not snapped by the

absence of discriminatory intent alone, or even by a firm

commitment to desegregation, where it is not accompanied by action

that in fact produces a unified school district. Id.

Where a plaintiff has established segregation in the past and

the present, it is "entitled to the presumption that current

disparities are causally related to prior segregation, and the

burden of proving otherwise rests on the defendants." School

Board of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308, 1311 (4th

Cir. 1987).24 This presumption ensures that subconscious racial

discrimination does not perpetuate the denial of equal protection

to our nation's school children.25 A focus on provable intent

alone would deny a remedy to too many Americans.

See Keyes, 413 U.S. at 211; Vaughns v. Board of Educ., 758

F .2d 983, 991 (4th Cir. 1985).

25 As one commentator has observed, "[A]mericans share a

historical experience that has resulted in individuals within the

culture ubiquitously attaching a significance to race that is

irrational and often outside their awareness." Lawrence, The Id,

the Ego, and Equal Protection: Reckoning With Unconscious Racism,

39 Stan. L. Rev. 317, 327 (1987).

-20-

Contrary to the district court's apparent conclusion, see 671

F. Supp. at 1297, remoteness in time does not make past

intentional acts less intentional. See Dayton II, 443 U.S. at

535-36; Keyes v. School District No. 1 , 413 O.S. 189, 210-11

(1973). The passage of time merely presents an opportunity for a

school district to show that the presumptive relationship between

the de jure system and the current system is so attenuated that

there is no causal connection. See id. at 211.

What the school district has done to integrate is crucial in

determining whether the causal link between the prior segregation

and the current disparities has been severed. The district may

carry its burden by showing that it has acted affirmatively to

desegregate. Absent such proof, the court must presume that

current segregation is the result of prior intentional state

action. A showing that the school district has not promoted

segregation and has allowed desegregation to take place where

natural forces worked to that end is insufficient.

The ultimate test of what the school district has done is its

effectiveness, most significantly its effectiveness in eliminating

the separation of white and minority children. ^ While a district

is not always required to choose the most desegregative *

See Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 462

(1972); Davis, 402 U.S. at 37; Swann, 402 UTS. at 25.

-21-

the result ofalternative when it selects a particular option,27

the sum of the choices made by the district must be to desegregate

the system to the maximum possible extent.28 29 * Furthermore, the

school district may "not . . . take any action that would impede

the process of disestablishing the dual system and its effects."

Dayton II, 443 C.S. at 538.

One choice frequently made by school districts, and the one

made in Topeka, is to use a neighborhood school plan as the basis

for student assignment. Neighborhood schools are a deeply rooted

and valuable part of American education.28 To the extent that

neighborhoods are themselves segregated, however, such plans tend

to prolong the existence of segregation in schools.20 Thus, they

must be carefully scrutinized. They are not "per se adequate to

meet the remedial responsibilities of local boards." Davis, 402

O.S. at 37; see Dnited States v. Board of Education, Independent

See Pitts v. Freeman, 755 F.2d 1423, 1427 (11th Cir. 1985).

28 See Diaz v. San Jose Unified School Dist., 733 F.2d 660 (9th

Cir. 1984") (en banc) (castigating school district for consistently

choosing more segregative alternatives), cert, denied, 471 U.S.

1065 (1985).

29 See 20 D.S.C. S 1701 (1982) (declaring it to be the public

policy of the Dnited States that neighborhood schools are the

appropriate basis- for determining public school assignments);

Crawford v. Los Angeles Bd. of Ed., 458 D.S. 527, 537 n.15 (1982);

D\az, 733 F.2d at 677 (Choy, J ., dissenting).

30 See Swann, 402 O.S. at 28; Diaz, 733 F.2d at 664.

School District No. 1, Tulsa County, 429 F.2d 1253 (10th Cir.

1970).31

Neighborhood school plans must be both neutrally administered

and effective. A plan that is administered in a scrupulously

neutral manner but is not effective in producing greater racial

balance does not fulfill the affirmative duty to desegregate.32

It is equally important that a plan's neutrality be more than

surface-deep. We have specifically held that when minorities are

concentrated in certain areas of the city, neighborhood school

plans may be wholly insufficient to fulfill the district's

affirmative duty to eliminate the vestiges of segregation. Tulsa

County, 429 F.2d at 1258-59. Even when neighborhood school plans

On remand, the district court in Tulsa County developed a

plan to desegregate Tulsa's schools, which we subsequently

affirmed. 459 F.2d 720 (10th Cir. 1972). The Supreme Court then

summarily reversed our affirmance of the proposed plan and

remanded for reconsideration in light of Keyes. 413 D.S. 915

(1973). We then determined that "the factual premise upon which

we based our original decision ha[d] been so materially changed

both by lapse of time and the specific and voluntary actions taken

by the School Board and the students themselves that our further

consideration under the present record would serve no useful

purpose.” 492 F.2d 118S (10th Cir. 1974). We remanded to the

district court for such further proceedings as might be necessary

to bring the school district in conformity with the Keyes mandate.

Our original decision overturning the district court's finding of

no constitutional violation remains the law of this circuit.

32 See Morgan v, Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 328-29 (1st Cir. 1987)

(racial neutrality is "unreliable talisman"); Diaz, 733 F.2d at

664 (adherence to neighborhood plan not determinative on question

of segregative intent); Adams v. Dnited States, 620 F.2d 1277,

1285-86 (8th Cir. 1980) (en banc) (adoption of neighborhood school

plan did not fulfill duty to desegregate); c f . Pitts, 755 F.2d at

1426 (mere adoption of desegregation plan insufficient to render a

dual system unitary).

-23-

hold the. promise of being effective, courts must recognize that

the school district's choices on such questions as where to locate

new schools, which schools to close, how to react to overcrowding

or underutilization, and what transfer policy to offer, all have

obvious impact on the school attendance boundaries the district

can draw under a neighborhood school plan.33 If these choices are

not made with an eye toward desegregation, a neighborhood school

plan may "further lock the school system into a mold of separation

of races." Swann, 402 U.S. at 21. Ultimately, whether the use of

a neighborhood school plan in a particular case is consistent with

a school district's duty to desegregate turns on whether the

"school authorities [have made] every effort to achieve the

greatest possible degree of actual desegregation taking into

account the practicalities of the situation." Davis, 402 U.S. at

33.

Actions the school district has not taken are also relevant

in considering what the district has done. A school district

which has not made use of such classic segregative techniques as

gerrymandering, discriminatory transfer policies, and optional

attendance zones is more likely to have fulfilled its duty to

desegregate than a district that has done so.34 Similarly, a

See Columbus Bd. of Educ., 443 U.S. 449, 462 & nn. 9-11

(1979); Swann, 402 U.S. at 28; Diaz, 733 F.2d at 667-71; Tulsa

County, 429 F.2d at 1256-57.

34 See Adams, 620 F.2d at 1288-91 (intact busing, school site

selection, block busing, transfer policy, and segregated faculty

-24-

school district that has made use of the various techniques

available to encourage voluntary desegregation is more likely to

have fulfilled its duty than one that has not.35 36 Such techniques

may include, for example, the establishment of magnet schools and

vigorous official encouragement of desegregative transfers.

Finally, objective proof of the school district's intent must

be considered. How a district lobbies its patrons and government

agencies on issues that affect desegregation, whether it seeks and

then heeds the desegregation recommendations of others, and the

cooperativeness of the district in complying with court orders,

for example, bear on the manner in which the district has shaped

the current conditions in the school district.36

assignments); Higgins v. Board of Educ., 508 F.2d 779, 787 (6th

Cir. 1974) (listing segregative techniques); Tulsa County, 429

F.2d at 1257 (transfer policy).

35 See Ross, 699 F.2d at 222, 227; Price, 694 F.2d at 351-53;

c f . Diaz, 733 F.2d at 672-73 (criticizing school district for

implementing none of desegregation proposals made by citizens'

committee).

36 See Columbus, 433 O.S. at 463 n.12 (Board refused to seek

advice on desegregation or implement recommendations); Morgan, 831

F.2d at 321 (noting cooperation with court orders); Diaz, 733 F.2d

at 671-74 (manipulation of committee studying segregation;

statements suggesting failure of bond issue would lead to forced

busing); Ross, 699 F.2d at 222-23 (school district appointed

community task force to develop magnet plan, opposed efforts to

disrupt integration plans, and promoted interdistrict transfer).

-25-

C. Maximum Practicable Desegregation

What more can and should be done, if anything, is the final

component in a determination of unitary status.3^ Essentially, a

defendant must demonstrate that it has done everything feasible.

Courts must assess the school district's achievements with an eye

to the possible and practical, but they must not let longstanding

racism blur their ultimate focus on the ideal.* 38

i

In most unitariness cases, the school district has been

implementing a court-approved desegregation plan under active

court supervision. The question is usually whether closer

adherence to the plan is practical or whether the plan has

achieved its objectives.39 The district court in such cases has

been intimately involved with the process of desegregation and is

well aware of the obstacles it faces. The court can thus make an

informed judgment on the possibilities of further desegregation.

Where the school district has complied with the desegregation plan

to the best of its ability, and has done what can be done in spite

See Davis, 402 U.S. at 37; Morgan, 831 F.2d at 322-25; Ross,

699 F773 at 224-25.

38 See Morgan, 831 F.2d at 324; Ross, 699 F.2d at 225.

39 See Morqan, 831 F.2d at 322-25; Riddick, 784 F.2d at 532-34;

Calhoun, 522 F.2d 717.

-26-

of the obstacles in its way, it is reasonable to conclude that no

further desegregation is feasible.4®

The present case is one of those rare ones in which the

unitariness determination is not directly tied to the execution of

a particular desegregation plan. In such a case, the

consideration of whether further desegregation is practicable must

include the obstacles that are likely to stand in its way, and

whether they may be circumvented without imperiling students'

health or the educational process. See Swann, 402 D.S. at 30-31.

Where there are no significant barriers to desegregation, or such

barriers as exist may be overcome without undue hardship, further

desegregation is practicable. See id. at 28 (mere awkwardness or

inconvenience is no barrier to carrying out desegregation plan).

In sum, when a school system was previously de jure, a

plaintiff bears the burden of showing that there is a current

condition of segregation. It may do so by proving the existence

of racially identifiable schools. The school district must then

show that such segregation has no causal connection with the prior

de jure segregation, and that the district has in fact carried out

See Ross, 699 F.2d at 224 (further remedial efforts would be

unreasonable and inadequate); Calhoun v. Cook, 525 F.2d 1203, 1203

(5th Cir. 1975) (per curiam) ("It would blink reality . . . to

hold the Atlanta School System to be nonunitary because further

integration is theoretically possible and we expressly decline to

do so.").

-27-

the maximum desegregation practicable for that district. We now

apply these legal principles to Topeka.

V.

THE FINDING OF UNITARINESS

Because Topeka's schools formerly operated under a system of

de jure segregation, ”[t]he board's continuing obligation . . .

[has been] 'to come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work . . . now, . . . until it is clear that

state-imposed segregation has been completely removed.'" Columbus

Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459 (1979). Prior to

this case, no court had pronounced the Topeka school system

unitary; hence, this duty never dissipated. The district court

concluded, however, that the effects of de jure segregation have

been eliminated in Topeka. On appeal, plaintiffs attack this

determination.

A. Burden of Proof

Plaintiffs argue initially that the district court improperly

required them to prove intentional discriminatory conduct on the

part of the school district over the course of the decades instead

of according them the benefit of a presumption that current

segregation stems from th^ prior de jure system. Plaintiffs quote

a number of sentences from the district court's opinion as support

-28-

for their argument that the court placed on them the burden of

proof on intent. Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants at 27.41 The

court itself expressed some confusion as to the proper burden of

proof. 671 F. Supp. at 1295. We have considered both these

citations and the tenor of the district court's opinion as a

whole, and we are convinced that the court focused too greatly on

the school district's lack of discriminatory intent. Although the

percentage of minority students in Topeka is lower than in other

cities involved in desegregation cases and consequently the

statistics alone do not appear as egregious, we are persuaded that

this overemphasis on the school district's intent led the court to

make the same errors as did the district court in Dayton II. It

failed "to apply the appropriate presumption and burden-shifting

principles of law." Brinkman v. Gilligan, 583 F.2d 243, 251 (6th

Cir. 1978), aff'd sub nom. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

443 O.S. 526 (1979).

The district court made the following findings: that the

neighborhood school attendance boundaries drawn in 1955 had the

effect of maintaining segregation; that the construction of new

41 For example, the district court stated:

"Although, on its face, the construction of

schools, particularly on the west side of the district,

appears to have promoted racial separation, the court

does not believe that the district's school construction

policy was intended to maintain or promote segregation."

671 F. Supp. at 1300 (emphasis added).

-29-

schools since that time had the effect of "promoting] racial

separation"; that the reassignment of students from previous de

jure schools to adjacent schools with higher-than-average

percentages of minority students had the effect of increasing

those percentages; and that the assignment of faculty had the

effect of placing minority faculty disproportionately at schools

with higher-than-average minority student percentages. 671 F.

Supp. at 1300, 1301, 1304-05. It is clear from the court’s other

findings that the school district's use of space additions, its

siting of Topeka West high school, its drawing of attendance

boundaries, and its failure to adopt various reorganization plans

did not further the process of desegregation. Id. at 1298-1301,

1308-09. Nevertheless, the court's discussion of most of these

aspects of Topeka's history ends with the conclusion that because

these actions were not taken with the intent to discriminate and

were consistent with a "race-neutral" neighborhood school plan,

they did not promote segregation.^ The court evidently believed

that if these two criteria, i.e., no intent to discriminate and

consistency with a race-neutral neighborhood school plan, were

See, e.q., 671 F. Supp. at 1298-99 ("the use of space

additions was consistent with a race-neutral neighborhood

policy. . . . [I]t has not been shown that space additions were

intentionally used to promote segregation. . . ."); .id. at 1300

("The court believes the siting of Topeka West High School was a

race-neutral decision."); id. at 1301 ("The district has

consistently applied race-neutral, neighborhood school principles

to the demarcation of attendance zones."); id. at 1309 ("The court

does not believe the district's conduct over thirty years

indicates a desire to perpetuate segregation by foregoing

opportunities to desegregate schools.").

-30-

met, the school district's actions would pass constitutional

muster.

While we agree with the district court's findings that the

current school administration is not presently acting with

discriminatory intent — indeed, there is evidence that the

present school board has some commitment to desegregation — we

are persuaded that the court failed adequately to weigh the

conduct of the school district for the past thirty years, and the

current effects of that conduct. The court erred by limiting the

school district's burden merely to showing that it had

nondiscriminatory reasons for acting as it did. As thirty years

of desegregation law have made clear, the Constitution requires

more than ceasing to promote segregation. See part IV supra.

"[T]he measure of the post-Brown I conduct of a school board under

an unsatisfied duty to liquidate a dual system is the

effectiveness, not the purpose, of the actions in decreasing or

increasing the segregation caused by the dual system." Dayton II,

443 O.S. at 538. A lack of intent to discriminate is therefore

insufficient. "'Racially neutral' assignment plans . . . may be

inadequate; such plans may fail to counteract the continuing

effects of past school segregation . . . . In short, an

assignment plan is not acceptable simply because it appears to be

neutral." Swann, 402 U.S. at 28. Mere adherence to a race-

neutral but ineffective neighborhood school plan is therefore alio

insufficient. In general, any course of action that fails to

-31-

provide meaningful assurance of prompt and effective

disestablishment of a dual system is unacceptable. Wright v.

Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 460 (1972). The

district court did not heed this mandate. While it did find that

the school district had taken some actively desegregative actions,

we are convinced that the court's overall conclusion as to

unitariness was fatally infected by the inadequacy of the burden

of proof standard to which it held the school district.

B. The Evidence

In order to assess the district court's finding of

unitariness under the appropriate burden of proof and the general

principles we have outlined, we turn to a more specific review of

the record. As a general matter, it is important to note that

much of the record evidence consists of statistics and other

undisputed facts. Our differences with the district court lie

mainly in how the essentially undisputed facts are characterized.

We believe that the district court's finding of unitariness is

flawed by the undue deference it gave to the school district's

neighborhood school policy and by the court's failure to give

proper weight to its own findings that certain actions and

omissions by the school district had a segregative effect.

-32-

1 . Current Condition of Segregation in Topeka

The district court found that "there are disparities in the

racial makeup of various schools' enrollments," and that

"[p ]laintiffs have demonstrated that in general there are a

greater than average number of minority faculty and staff in

schools with a greater than average number of minority students."

671 F. Supp. at 1295, 1304. Like most courts, however, the

district court did not discuss separately the issues of current

segregation and the causal connection between that segregation and

the prior de jure segregation.

As we have pointed out, the simplest and most compelling

evidence of segregation is the presence of predominantly one-race

schools. In a system such as Topeka's, however, in which the

minority student population is relatively small, there may be a

number of primarily white schools even though minority students

are spread through a significant number of other schools. In such

a system, it is the concentration of minority students that is

usually the hallmark of discrimination. Because the significance

of mostly white schools is therefore not necessarily as great in a

mostly white system as it would be in a system with a heavy

minority population, we focus on the broader form of racial

identifiability discussed in part IV A above. In support of their

argument that there is currently segregation in Topeka, plaintiffs

-33-

point primarily to student assignment, and faculty and staff

assignment. We consider each in turn, and then together.

a. Student Assignment

Each of the experts who testified at trial used a different

standard for determining whether a school was racially

identifiable in student assignment. Plaintiffs' main experts,

Drs. Lamson and Foster, each used standards that took the

percentage of black or minority students actually enrolled in the

elementary or secondary schools (26% in 1985), and then added and

subtracted some number to obtain a range within which they did not

consider schools to be racially identifiable on the basis of

student assignment alone. Their methods differ to some extent,

but for 1985 either method leads to a range of 11-41% (26% plus or

Plaintiffs do not contest the district court's finding that

the Topeka school system is unitary with respect to facilities,

extracurricular activities, curriculum, transportation, and

equality of education. See Brown, 671 F. Supp. at 1307-08. There

are currently no optional attendance zones, and the district's

transfer policy is a majority-to-minority program. See id. at

1298.

Plaintiffs commissioned a public opinion survey in order to

determine whether Topekans perceive some schools as black/minority

and others as white, whether they perceive some schools as

providing an inferior education, and whether there is a

correspondence between the two. While the results of the survey

provide some support for plaintiffs' contentions, the survey was

extensively criticized as unreliable by several of the school

district's experts. The district court discussed additional flaws

and concluded that the survey was not strong evidence of the

existence of segregation. 671 F. Supp. at 1305-06. We see no

error in that conclusion. We therefore disregard the survey

results.

-34-

minus 15%). The school district's primary expert on this issue,

Dr. Armor, used an absolute rather than a relative standard. In

his view, desegregated schools should optimally have 20-50%

minority students, regardless of the percentage of minority

students in the system. Dr. Armor also allowed a variance, which

resulted in a range of acceptability of 10-60%.44

As plaintiffs point out, under any of these methods there are

schools in Topeka that are racially identifiable by student

assignment. Even under the most generous of these numerical

standards, proposed by the school board's expert, there are six

elementary and three secondary schools that are racially

identifiable by student assignment.

44 The school district also offered two indices as a measure of

desegregation in Topeka’s schools. Rec., vol. XIII, at 2574-80.

The dissimilarity index measures how dissimilar schools are

compared to the district's mean. Rec., vol. IV, at 558. The

exposure index is a measure of the potential for interracial

contact. The indices are measures of system-wide desegregation,

however; they say nothing about individual schools. Rec., vol.

IV, at 554-57; rec., vol. XIII, at 2581.

-35-

b. Faculty and Staff Assignment

To determine racial identifiability by faculty/staff

assignment, plaintiffs again used a standard based on the actual

percentage of minority employees and a range of a few percentage

points above and below that number. The school district contested

the accuracy of plaintiffs' standard but presented no alternative

one. We do not adopt plaintiffs' standard, but instead evaluate

the data on its face.1

In 1985, the percentage of minority faculty/staff in the

Topeka school system was 11.2% for the elementary schools and

12.65% for the secondary schools. In the elementary schools, the

percentage of minority faculty/staff at individual schools ranged

from 0% to 33.3%. Nine schools had less than 5% minority faculty/

staff, and two had more than 25%. ̂ In the secondary schools, the 1 2

1 The range used by plaintiffs was very narrow, and it was

extremely difficult for any school to fall within it. In 1985,

for example, only four of the twenty-six elementary schools were

not racially identifiable under plaintiffs' standard. While it is

appropriate to use a harsher standard for analyzing faculty

assignments than student assignments, since the school district

may assign faculty as it sees fit, plaintiffs' standard is simply

too difficult to meet in this case. We note, moreover, that the

school district is limited to some extent in its ability to assign

faculty because different teachers are certified in different

fields. This is particularly true at the secondary level.

2

Minority Faculty/Staff In

Topeka's Elementary Schools, 1985

School______________________ Total_____Minority_________%

Avondale East 31.4 10.45 33.3

-36-

percentage ranged from 2.5% to 24.7%. One school had less than 5%

minority faculty/staff, an additional three schools had less than

10%, and one had more than 20%.^

Avondale West 25.8 1.0 3.9

Belvoir 25.95 3.85 14.8

Bishop 23.8 .4 1.7

Crestview 31.65 3.4 10.7

Gage 21.0 1.0 4.8

Highland Park Central 34.6 3.9 11.3

Highland Park North 28.6 5.5 19.2

Highland Park South 29.2 5.4 18.5

Hudson 19.75 3.8 19.2

Lafayette 32.6 5.65 17.3

Linn 17.8 .3 1.7

Lowman Hill 25.6 6.5 25.4

Lundgren 21.55 2.8 13.0

McCarter 27.4 3.0 10.9

McClure 25.1 0.0 0.0

McEachron 23.5 1.0 4.3

Potwin 14.15 2.0 14.1

Quincy 32.35 1.0 3.1

Quinton Heights 20.4 4.4 21.6

Randolph 27.0 1.0 3.7

Shaner 21.9 2.0 9.1

State Street 22.9 1.3 5.7

Stout 20.6 2.0 9.7

Sumner 23.3 1.85 7.9

Whitson 35.35 1.0 2.3

Average minority faculty/staff: 11.2%.

, , ex. vol. IV, at 261 •

Minority/Staff In

Topeka's Secondary Schools, 1985

School Total Minority %

Chase 40.5 7.45 18.4

Eisenhower 65.25 12.1 18.5

French 42.6 2.4 5.6

Jardine 39.65 3.8 9.6

Landon 31.1 3.0 9.6

-37-

Faculty/staff data have been -kept only since 1973 and, except

for 1981, that data does not distinguish between faculty and

staff. Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 263-68. Faculty/staff includes

managerial personnel at both the school and district level,

teacher aides, clerical/secretarial employees, skilled and

technical employees, and service workers, as well as teachers and

other professional staff. The distinction between faculty and

staff is particularly relevant because the percentage of minority

employees has always been lower than the minority student

population, and has fallen steadily at the elementary level over

the period such data was kept. Moreover, minorities are

represented more heavily in staff positions than in faculty

positions. In 1985, for example, district-wide statistics showed

that 11.3% of elementary teachers and 8.0% of secondary teachers

were minorities, while 19% of teacher aides and 20% of service

workers were minorities. Rec., vol. IV, at 268. Any one faculty/

staff person listed at any one school is thus twice as likely to

be a teacher aide or service worker as a teacher.

Robinson 49.35 12.2 24.7

Highland Park 118.25 13.65 11.5

Topeka 150.1 25.5 17.0

Topeka West 120.0 3.0 2.5

Average minority faculty/staff:

Rec., ex. vol. IV, at 262.

-38-

12.65%.

We 'recognize that the small number of faculty and staff at

any one school means that the presence or absence of one minority

employee may have a considerable effect on the school's minority

percentage. Nevertheless, we see no obviously neutral reason why

McClure elementary school has no minority employees among its 25

faculty/staff and Topeka West high school has 3 among 120, while

Avondale East elementary school has 10 minority faculty/staff out

of a total of 31 employees and Robinson middle school has 12 out

of 49. We therefore conclude that faculty/staff assignment in

Topeka remains segregated.

c. Factors considered together

Because faculty/staff assignment is largely within the

control of the school district, it is a potent tool for

demonstrating that the district does or does not itself identify

certain schools as white or minority. It also provides an

opportunity for undoing some of the harm of segregated student

assignments, because both white and minority students may benefit

from the presence of minority role models. See Washington v.

Seattle School District, No. 1 , 458 O.S. 457, 472 (1982) ("white

as well as Negro children benefit from exposure to ethnic and

racial diversity in the classroom"). Conversely, if the district

disproportionately assigns minority^ faculty/staff to those schools

with the highest percentages of minority students, the district is

in effect reinforcing the identification of particular schools as

-39-

white or minority. This practice of disproportionate assignments

also reinforces the irrational nation that minority teachers are

inferior and not fit to teach white children.

In Topeka, although the correlation is not completely

uniform, see 671 F. Supp. at 1305, there is a clear pattern of

assigning minority faculty/staff in a manner that reflects

minority student assignment. This correlation is fatal to the

school district's effort to show a lack of current segregation.

Both student assignment and faculty/staff assignment can be

expected to vary from school to school, the former because of

population distribution, and the latter, to a lesser extent,

because of differing teacher credentials. When they vary

together, as they do in Topeka, leading to schools that are

noticeably more white or more minority in both students and

faculty, it is difficult to posit a neutral explanation. The

school district has not attempted to provide one.

Moreover, when we look beyond the numbers, we find that the

schools that are marked as white or minority by their students and

faculty/staff are also so marked by their geography, the

residential population in their attendance areas, and by their

history. Of the six racially identifiable elementary schools

detected by Dr. Armor's method, five are now and always have been

attended almost exclusively by white students. They are located

on the western and northwestern edges of the school district,

-40-

The same is true of theareas with mostly white populations.4

.three secondary schools. See infra part V B (2)(c ) (vii). The one

remaining elementary school, Belvoir, is located on the eastern

edge of the school, district. The area has long been inhabited by

a significant minority population, and the school's student

population is now and has been for over twenty years more than

half minority. See infra part V B(2)(c)(i). Finally, the

correlation between student assignment and faculty/staff

assignment is not a one-year fluke. The same correlation has

existed throughout the course of this litigation. See infra part

V B(2)(b)(ii). Considering all of these factors together, there

is sufficient evidence to support plaintiffs' contention that

there is a current condition of segregation in Topeka.^ * 30

4 For two of these schools, Gage and Potwin, the district court

specifically found that they have been predominantly white schools

since the Supreme Court's decision in this case, and remain

predominantly white schools adjacent to schools with higher-than-

average minority student population. 671 F. Supp. at 1303.

We do not consider this part of our opinion necessarily in

conflict with the district court's conclusion that there is no

illegal segregation in Topeka, because the court did not

separately consider the issue of current segregation apart from

the question of causation. As we previously pointed out, the

district court did find the existence of racial disparities in

school enrollment and staff/faculty assignment. See supra at pp.

30, 33. Our disagreement with the district court is chiefly on

the significance of these findings in a district with Topeka's

history, and bearing the weight of a presumption against it which

the district court failed to accord.

-41-

2 . The Causal Link Between De jure Segregation and the Current

Condition of Segregation

Brown I established that the Topeka school system was one of

de jure segregation. Because there is a current condition of

segregation, we turn our attention to the causal link between

these two conditions of segregation, which must be assessed in

light of the burden and factors set out in part IV B, supra. We

are convinced that the school district failed to meet its burden

of showing the absence of this link. This failure, which the

district court did not see because it failed to impose on

defendants the proper burden of proof, is the key to our reversal.

Timing is central to an assessment of the Topeka school

district’s actions. After a remarkably enlightened beginning in

the mid-1950s, the course it followed in the early 1960s may

fairly be characterized as segregative. This decade from 1956 to

1966 is important because it established a framework from which

the school district subsequently deviated very little.® A period

of quiescence then followed, during which the system was simply

administered as it stood. Finally, under the impetus of the HEW

° Thus, one of the school district's experts, after reluctantly

admitting that Lowraan Hill elementary school's attendance

boundaries were drawn in the 1950s with the effect of encompassing

the only two areas of black population in that part of Topeka, and

that the school was long surrounded by other schools with few to

no black students, objected that "the boundaries of those school

districts [were] in place." Rec., vol. XI, at 2345.

-42-

proceedings in the mid-1970s, the school district undertook some

positive action to desegregate its schools. After that brief

flurry of action, the school district again turned its attention

elsewhere, but to its good fortune the oft-maligned forces of

demography began to work in its favor. Two things are apparent

from the record. First, Topeka has largely acted as if its duty

to desegregate had been fulfilled at the conclusion of the four-

step plan implemented in the 1950s. Second, although Topeka's

schools have in fact become less segregated in the last decade,

this lessening of segregation is due in part to forces beyond the

control of the school district. Moreover, those actions

undertaken by the school board were primarily the result of

pressure from the federal government. Although its record is

better than that of many other school districts, Topeka has

engaged in voluntary desegregation with little enthusiasm.

a. The general pattern in each decade

i. The mid-50s to raid-60s

This period was one of significant change in the Topeka

school district. Most notably, the district expanded greatly with

several city-imposed annexations at the end of the 1950s, the

beginning of a spurt in population growth and shift to the newly

annexed areas, and the school district's consequent opening of new

schools in this outer white part of Topeka. As the white

-43-

population moved outwards, the inner city population became

increasingly heavily minority, and inner city schools were closed.

The mid-60s found the Topeka school system still heavily

segregated. While the numeric polarization between schools had

decreased to some extent systemwide,”̂ and minority students were

somewhat less concentrated,* 8 the number of schools serving

primarily white children had increased. Geographic polarization

also increased, as a result of the building of so many primarily

white schools on the outer edges of the district. Plaintiffs

introduced evidence tending to show that the school district's use

of portable classrooms and optional attendance zones served to

maintain segregation by concentrating students of one race at

certain schools. The school district's expert, Dr. Clark,

conceded that his study of changes in attendance zone population

because of changed attendance boundaries led him to conclude that

' In 1955, 3 elementary schools were 99+% black and 14

elementary schools were 90+% white for a total of 17 out of the 23

elementary schools. In 1966, 1 elementary school was 90+%

minority and 19 elementary schools were 90+% white, for a total of

20 out of the 35 elementary schools. Rec., ex. vol IV, at 39-40,

54-56. Pages 30-181 of volume IV of the exhibits consist of

student enrollments for individual schools from 1950 to 1985. We

henceforth refer to this part of the record as Student Tables.

8 In 1955, about half of Topeka's black students attended three

schools that were 99+% black. In 1966, approximately the same

percentage of minority students attended one 90+% minority school

and three 50-80% minority schools. Student Tables, 1955, 1966.

-44-

one such boundary change might have had segregative effects not

Q

explainable solely by demographic shifts.7

We have no doubt that during this period the school district

in fact maintained and perhaps promoted a segregated system by

current standards. Moreover, the system that existed after the

wave of school openings and closings ended, i.e., the location of

schools and the race of their students, formed the basis for the

current elementary system. Therefore, while the school district

should not be judged primarily by actions now twenty or more years

in the past, neither can those actions be ignored.

ii. Mid-60s to Mid-70s

This period was one of quiescence in the school district.

Enrollment in the Topeka school system peaked in 1969,

substantially ending the need for new school buildings. Outer

Topeka continued to grow in white population, particularly in the

western part of the city. Minority population began to spread out

of its highly concentrated central areas into eastern Topeka.

The only significant change in the school system at the end

of this period was that the number of virtually all-white schools

dropped. At the elementary level, 19 out of a total of 35 *

® Rec., vol. XI, at 2326.

-45-

elementary schools were virtually one-race in 1966; 13 out of a

total of 34 were virtually one-race in-1974.^ The difference at

the secondary level was less: from 6 out of 14 schools in 1966,

to 5 out of 15 schools in 1974. This change took place primarily

in schools on the outskirts of the southeastern part of Topeka,

the area into which minorities were spreading. The school

district's conduct during this period can thus be summarized as

letting demographic forces work without interference or

encouragement. This also means that schools already heavily

minority were allowed to increase in minority population.11 It is

apparent that while Topeka did not promote a segregated school

system during this period, it maintained the system then in

effect.

iii. Mid-70s to the present

In 1974, the HEW compliance action began the third phase of

the Topeka school system since Brown I . At the elementary level,

HEW cited unequal facilities for minority and white children as

well as "student racial compositions not consonant with a unitary 10 11

10 Student Tables, 1966, 1974. Lyman elementary school was

deannexed during this period.

11 In 1966, Belvoir elementary school had 59.7% minority

students and Lafayette elementary school had 54.5% minority

students. By 1974, Belvoir had 67.1% minority students and

Lafayette had 68.9%. At the secondary level, Crane junior high

rose from 34.45% minority in 1966 to 52.9% in 1974, while East

Topeka junior high remained more than 60% minority. Student

Tables, 1966, 1974.

-46-

plan." Five elementary schools were specifically listed as having

"substantially disproportionate minority.student compositions

clearly the result of a former dual pattern of operation." At the

secondary level, HEW found that the junior high schools attended

by most minority students were inferior in facilities to those

schools attended largely by white students. In addition, the

district's transfer plan was criticized.* 13 The Board denied that

the district was in noncompliance and obtained an injunction

against further HEW administrative proceedings. Nevertheless, the

Board agreed to take "administrative steps to assure a more

perfect unitary school district."13 It developed and implemented

two plans largely approved by HEW.

These plans had some success. At the end of the

reorganization, there were no 90+1 minority elementary schools,

the attendance boundaries of two 90+% white schools had been

redrawn so that they were no longer one-race, and a third one-race

white school had been closed. At the secondary level, two heavily

minority and one primarily white junior high school had been

closed, although the minority population of one other junior high

school had risen significantly as a result of the reorganization.

The school district's desegregation indices dropped as much in the

Rec., vol. V, at 12-14.

13 Rec., vol. XII, at 2485-91; rec., ex. vol. V, at 245-47.

-47-

six years from 1975 to 1981 as they had fallen in the previous

twenty years.14 15

Some of this decline, however, was the result of the movement

of minorities into the western part of the school district.

During the same six-year period, three additional elementary

schools rose above the 10% minority level solely because of this

demographic change.^ This movement has continued. In 1985, two

additional elementary schools were just barely no longer one-race

for that reason.1®

Other changes that took place in this decade are as follows:

elections to the Board were changed in 1976 to ensure that all

parts of the city were fairly represented; the Board has now, and

has had for some time, significant minority representation; in

1981, the district abandoned a slightly segregative majority-to-

minority transfer policy for a transfer policy that is slightly

desegregative; in 1984, while this trial was pending, a black

superintendent was appointed; and, five days before the beginning