Drew Municipal Separate School District v. Andrews Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Drew Municipal Separate School District v. Andrews Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae, 1975. 20f91b37-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/170763b5-f5e1-4e4e-b52f-412b3b694ffd/drew-municipal-separate-school-district-v-andrews-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

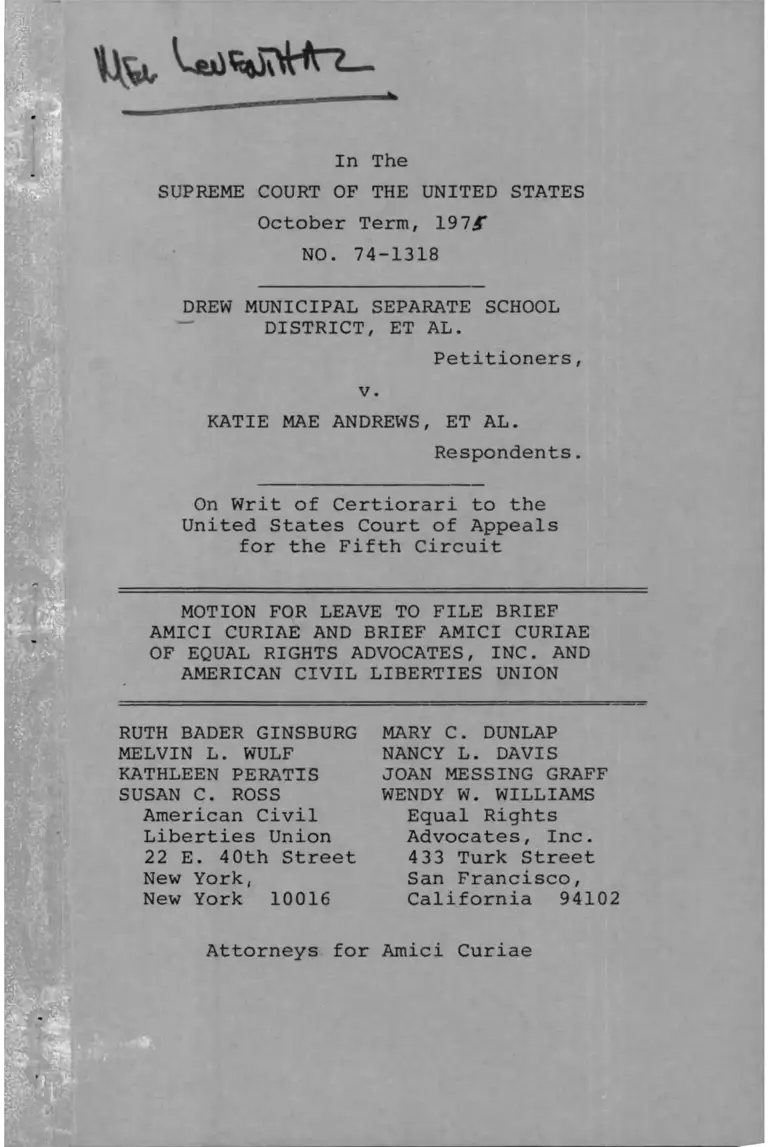

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 197/-

NO. 74-1318

DREW MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, ET AL.

Petitioners,

v.

KATIE MAE ANDREWS, ET AL.

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

OF EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES, INC. AND

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

RUTH BADER GINSBURG

MELVIN L. WULF

KATHLEEN PERATIS SUSAN C. ROSS

American Civil

Liberties Union

22 E. 40th Street

New York,

New York 10016

MARY C. DUNLAP

NANCY L. DAVIS

JOAN MESSING GRAFF

WENDY W. WILLIAMS

Equal Rights

Advocates, Inc.

433 Turk Street

San Francisco,

California 94102

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE......................... vii

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE................ xiv

INTEREST OF AMICI................ xiv

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF

ARGUMENT .............................. 1

ARGUMENT

I. Petitioners' Policy Represents

A Severe Historical Retro

gression, Against The Principle

Of Ending Sex Discrimination

Under L a w ..................... 5

A. The History of Anti-

Illegitimacy Measures

Is Thematically Linked

To Discrimination

Against Women ........... 5

B. Petitioners' Exclusion

Of Unmarried Mothers

From Employment Menaces

The Achievement Of

Equal Opportunity By Women.................. 2 4

II. Petitioners' Policy Discrimi

nates Against Females In

Violation Of The Constitutional

Guarantee Of Equal Protection................ 27

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

CASES

Cleveland Board of Education v.

LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974) . . . . 19

Estate of Lund, 26 C.2d 472,

159 P. 2d 643 (1945)........... 28

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S.

677 (1973) 24,44,45

Nichols v. Sauls' Estate, 165 S.2d

352 (Sup. Ct. Miss. 1964)............ 33

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268

(1951)................................ 30

Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971) 41,43,44

Sanders v. Tillman, 245 S.2d 198

(Sup. Ct. Miss. 1971)............. -31,33

Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645

(1972).............................. .34

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886)............................ . 39

MISCELLANEOUS

C. Atkinson & E. Maleska, The Story of

Education (1965)........! I ! [ 7 7 21

B. Babcock, A. Freedman, E. Norton

& S. Ross, Sex Discrimination And

The Law: Causes and Remedies

(1975)............................ 15

iii

19

R. Callahan, An Introduction To

Education In American Society

(1956) ..........................

F. Campbell, "Birth Control and

the Christian Churches", 14(2)

Population Studies 142 (1960) . . . 17

W. Chafe, The American Woman (1972) . 16

F. Cornford, trans., The Republic

of Plato 144 (1966)................ 24

K. Davidson, R. Ginsburg & H. Kay,

Sex-Based Discrimination (1973) . . . 15

Davis, "Illegitimacy and the Social

Structure", 45 Am.J.Soc. 215

(1939).............................. 13

K. Davis, "Population Policy: Will

Current Programs Suceed?", 158

Science 736 (1967)................ 24

D. Dewar, Orphans of The Living:

A Study of Bastardy (1968) ........ 6

B. Disraeli, Sybil (1845).......... 7

F. Donovan, The School Ma'am (1938) . 21

W. Elsbree, The American Teacher

(1939)............................ 20

C. Foote, R. Levy & F. Sander,

Cases and Materials on Family Law

118 (1966)........................ 43

O. Fowler, Perfect Men, Women and

Children (1878) 12

IV

P. Goubert, "Legitimate Fecundity and

Infant Mortality In France During The

Eighteenth Century: A Comparison",

97 Daedalus 593 (Spring 1968) . . . . 8

Hankins, "Illegitimacy: SocialAspects", 7 Encyclopaedia of Social

Sciences 579-581 (1932) . . . . . . . 16

G. Hardin, ed., Population, Evolution

and Birth Control (1969) .......... 17

E. Hecker, A Short History of

Women* 1s Rights (1910) ! ! ! 7 . . . . 11

S. Hartley, Illegitimacy (1975) . . . g

L. Kanowitz, Women and the Law:

The Unfinished Revolution (1969) . . 15

*H. Krause, Illegitimacy: Law and

Social Policy (1971) .............. 34

W. Langer, "Europe's Initial

Population Explosion", 69 American

Historical Review 1 (1963) ........ 7

J.L. Muret, "Memoire sur 1'etat de la

population dans le pays de Vaud",

Memoires de la Societe Economique

de Berne 57 (1766)................ 45

National Education Association,

Brief Amicus Curiae to the United

States Supreme Court, in Cleveland

Board of Education v. LaFleur,

Sup. Ct. No. 72-777 .............. 19

I. Pierce, Medical and Surgical

Reporter 614 (1888).............. 18

v

Secretary of the United Nations,

Report: "The Status of the Unmarried

Mother: Law and Practice" 56

(1971)........................ 14

R. Stein, "The Economic Status of

Families Headed By Women", U.S.

Dept, of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Monthly Labor Review

(December 1970) 25

M. Twain, Letters From The Earth . . 12

United Nations, Document #ST/TA0/

HR/22 (1964).................... 9

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1

Characteristics of the Population

Table 54 (1970).................... 9,35

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Subject

Reports: Persons By Family

Characteristics 1 (1970) 35

I. Woody, A History of Women's

Education In The United States (1966). 21

* * * * * * * * * * *

NOTE: All references to the testimoney

of Superintendent Pettey hereinbelow

are marked "P.T." (Pettey Transcript); all references to the testimony of

Mrs. McCorkle hereinbelow are marked

"Mc.T." (McCorkle Transcript).

vi

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1974

No. 74-1318

DREW MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, ET AL.

Petitioners,

v.

KATIE MAE ANDREWS, ET AL.

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE

TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. and the

American Civil Liberties Union respectfully

move for leave to file a brief amicus

curiae in this case. Respondents have con

sented to the filing of this brief. The

letter of consent accompanies this motion

and brief, for filing with the Court.

Counsel for amici has sought the consent

of petitioners to the filing of this brief,

by telephonic and written correspondence.

As of the time of preparation of this

motion, counsel for petitioners has not

responded to said requests for consent.

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. is a

non-profit, tax-exempt legal and educa

tional corporation dedicated to promoting

equal rights of men and women under law.

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. devotes sub

stantial amounts of time, energy and

resources to advancing the constitutional

and statutory rights of men and women to

be free from unlawful sex-based discrim

ination in employment.

Lawyers for Equal Rights Advocates,

Inc. have participated in a number of

cases challenging laws, policies and

practices that operate to disadvantage

the female child-bearer, including Gedul-

dig v. Aiello, __ U.S. ___, 94 S.Ct. 2485

vii i

(1974), which upheld the denial, against a

fourteenth amendment challenge, of state

disability benefits to women disabled by

"normal" childbirth, and Berg v. Richmond

Unified School District, ___ F.2d ___ (9th

Cir. 1975), which affirmed a Title VII

decision adjudging the school district's

policies as to maternity leave and accrued

sick pay to be violative of the Act. Law

yers for Equal Rights Advocates, Inc.

served as amicus curiae in Liberty Mutual

Insurance Co. v. Wetzel, No. 74-1245, now

pending before this Court, and in Gilbert

v. General Electric Co., 519 F.2d 661 (4th

Cir. 1975), also now pending before this

Court sub nom General Electric Co. v. Gil

bert .

The American Civil Liberties Union is

a nationwide, non-partisan organization of

over 250,000 members dedicated to defend

IX

ing the rights of all persons to equal

treatment under the law. Recognizing that

confinement of women's opportunities is a

pervasive problem at all levels of society,

the American Civil Liberties Union has

established a Women's Rights Project to

work towards the elimination of gender-

based discrimination.

Lawyers associated with the American

Civil Liberties Union Women's Rights

Project presented the appeal in Reed v.

Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), participated as

counsel for the appellants and later as

amicus curiae in Frontiero v. Richardson,

411 U.S. 677 (1973), represented the

appellant in Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351

(1974), the appellees in Edwards v. Healy,

421 U.S. 772 (1975), and Weinberger v.

Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), and the

petitioners in Struck v. Secretary of

x

Defense, 461 F.2d 1372 (9th Cir. 1971,

1972), cert. granted, 409 U.S. 947, judg

ment vacated, 409 U.S. 1071 (1972), and

Turner v. Department of Employment Secur

ity, ___U.S. ____, 96 S.Ct. 249 (1975),

and acted as amicus curiae in this Court

in several other gender discrimination

cases.

The American Civil Liberties Union

believes that this case poses an issue of

great significance to the realization of

full equality between the sexes. It con

cerns women's right to aspire and achieve

in accordance with their talents and capac

ities as individuals, their right not to

be caged, in lump fashion, by an indurate

classification that relegates them to

inferior status in society.

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. and

the American Civil Liberties Union seek

xi

to participate in this case as amici

curiae because each organization views

the achievement of fair and even-handed

treatment of mothers in public employment

as basic to the efforts of amici to win

equality for working women

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. and

the American Civil Liberties Union believe

that the within brief will be of assis

tance to the Court in resolving the

crucial issues before it. The brief offers

an historical analysis of the treatment of

mothers of "illegitimate" offspring, and

it discusses the issues raised by peti

tioners' exclusion of this group from

employment, insofar as the fourteenth

amendment's guarantee of equal protection

to these persons is concerned.

For these reasons, we respectfully

request leave to file the within brief

xii

amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

Mary C. Dunlap An Attorney for Movants

xi 11

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 74-1318

DREW MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL.,

Petitioners,

v.

KATIE MAE ANDREWS, ET AL.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI

The interest of amici is set

forth in the preceding motion for leave

to file this brief.

xiv

1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amici support the position that the

policy of petitioners is criss-crossed

with constitutional defects, any one of

which should prove fatal to it: it dis

criminates against Black persons on

account of race; it infringes grievously

upon the rights of privacy and procreative

choice; it arbitrarily deprives persons of

employment in a fashion causing uncon

scionable risk and harm to children, in

cluding economic suffering and personal

shame; and, it discriminates against

women on account of sex. Because of the

gravity and complexity of the sex dis

crimination issues raised by this case,

we will focus predominantly upon those

issues.

For many centuries and across

diverse cultures, campaigns have been

2

conducted through law to prevent child

bearing and child-rearing outside socie-

tally respected relationships. Keeping

women in their place has frequently been

a concern of these campaigns, and women

have historically suffered myriad punish

ments under these sex-discriminatory

schemes. The grave problem of employment

discrimination against women persists.

The policy of petitioners aggravates that

problem and activates its worst consequence

poverty. Petitioners' policy excludes

from employment a group of women whose

work affords not only a resource to

society that must be saved from the waste

of discrimination, but which affords the

means of economic self-sufficiency to

these women and their families. (Section I)

On its face, petitioners' policy

consists of a prohibition against employ

3

ment of unwed mothers. Founded upon ex

pressly sex-discriminatory instructions

to the personnel agent, rooted in the

avowed purpose of excluding persons who

are identifiable by the fact of their

parenthood as "bad role models", and

structured in the context of state laws

that empower male parents to avoid the

exclusion from employment, the face of

petitioner's policy plainly contains a

sex-based classification. (Section II-A).

Under the policy, five females and

no males have been excluded from employ

ment by petitioners. Even were facial

neutrality attributed to the policy, its

application has been, and is assured by

its structure to continue to be, sex-

discriminatory against women. (Section

II-B).

The sex-discriminatory nature of

4

petitioners' policy offends the equal

protection clause. The policy finds no

rational foundation in petitioners' "role

model" theory, insofar as the policy's

focus and structure immunize most offen

ders of the "role model" premise from the

exclusion from employment. The policy

bears neither a fair nor a substantial

relationship to any legitimate aim of

public school authorities. Additionally,

in their utilization of female sex as the

cutting edge of their categorical exclu

sion from employment, petitioners have

drawn a line which, for equal protection

purposes, merits strict scrutiny by this

Court. (Section II-C).

5

I. PETITIONERS' POLICY REPRE

SENTS A SEVERE HISTORICAL

RETROGRESSION, AGAINST THE

PRINCIPLE OF ENDING SEX

DISCRIMINATION UNDER LAW.

A. The History of Anti-Ille

gitimacy Measures Is

Thematically Linked To

Discrimination Against

Women.

The concept of "illegitimacy" has

varied in its legal dimensions across

cultures and eras, shaped and reshaped

by diverse societal, religious and

economic views of human sexuality and by

different and changing norms of manhood,

womanhood and childhood. With this per

vasive variability, one constant appears:

where legal and moral authorities have

punished the offspring of sexual inter

course occurring outside the bounds of

approved relationships, those authorities

have likewise punished the maternal

biological parents of these children, and

6

vice versa.

A dramatic and appalling example of

this interaction lies in the experience of

mothers and children under the English

Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which pur

portedly sought to prevent false accusations

of paternity by removing the financial

responsibilities of putative fathers,

while in fact sanctioning the mothers of

"illegitimate" children through severe

financial penalties. The Act resulted in

a crystallization of

"... the popular view of the

day, that it was the woman

with an illegitimate baby

who was guilty of succumbing

to temptation and the man

was not to be equally blam

ed. . . it had been decided

that erring women should

suffer to the full conse

quences of a 'fall'". 1/

1/ D. Dewar, Orphans of The Living: A

Study of Bastardy 20-21 (1968).

7

One apparent consequence of the Act

was infanticide. Around the time of the

Act's imposition of severe penalties upon

mothers of illegitimate children, Benjamin

Disraeli, in his sociologically informed

novel, Sybil, observed in 1845:

"Infanticide is practiced

as extensively and as

legally in England as it

is on the banks of the

Ganges...". 2/

Social and economic suffering for the

mothers and children affected were the

alternatives to abortion, infanticide and

the anonymous delivery of infants to

3 /foundling homes in which many died.—

2/ As quoted in W. Langer, "Europe's

Initial Population Explosion", 69

American Historical Review 1-17 (1963).

The practice of anonymous abandonment

of infants was by no means confined to

"illegitimate" mothers, for "... the

statistics show that of the thousands

of children thus abandoned, more than

half were the offspring of married

couples." Id. at fn 5/.

3/

8

In eighteenth century rural France

the phenomenon of "illegitimacy" was a

great deal less statistically common than

it was in England, but the socio-economic

situation of the unmarried French mother

was similar; it has been described by at

least one famous demographer as "excep-

4/tional and difficult."— Heavy social,

legal and moral stigmatization of

"illegitimacy" in France and in England

had completely opposite effects upon

"illegitimacy" rates -- a telling compar

ison, in the context of petitioners' re

cited purpose of deterring teenage

4/ P. Goubert, "Legitimate Fecundity and

Infant Mortality in France During The

Eighteenth Century: A Comparison",

reprinted at 97 Daedalus 593-594

(Spring, 1968) (Historical Population

Stud ies) .

9

"illegitimate" pregnancy — .

Severe punishments including death

itself have been visited upon mothers

of "illegitimate" children, motivated and

justified by— ^vindication of what is

commonly called "the double standard" of

sexual morality, under which women must * I

_5/ Superintendent Pettey testified be

low that " (I)n Drew, we have had in

the last two years... an alarming

number of school girl pregnancies...

I think that this is a problem that

we as school people, responsible for

the development of children, should

try to do something about." (P.T.8,

9) .

6/ As of 1964, in countries around the

region of Togo, the unmarried mother

"... is often considered as having

brought shame and dishonour to the

whole family and as a result, in

extreme cases, is murdered by her

brother or her father while no

punishment or hardly any is imposed

on the man involved." United Nations,

Document #ST/TAO/HR/22 at paragraphs

134-135 (1964). Refer also to note

12/, infra. Death is the penalty for

"illegitimate" maternity in other

regions as well. S. Hartley,

Illegitimacy 12 (1975).

10

remain virginal and uninformed about sex

ual matters until marriage, obedient and

ignorant of matters such as contraception

within marriage, hostile toward divorce

and infidelity, and generally ashamed of

7 /and displeased about sexual intercourse.—

7/ In 1880, the Reverend William John Knox

Little summarized many of these aspects

of woman's place under the double stan

dard of sexual morality as follows:

"God made himself to be born of a woman

to sanctify the virtue of endurance;

loving submission is an attribute of a

woman; men are logical, but women, lack

ing this quality, have an intricacy of

thought. There are those who think

women can be taught logic; this is a

mistake. They can never by any power

of education arrive at the same mental

status as that enjoyed by men, but they

have a quickness of apprehension, which

is usually called leaping at conclu

sions, that is astonishing. There,

then, we have distinctive traits of a

woman, namely, endurance, loving sub

mission, and quickness of apprehension.

Wifehood is the crowning glory of a

woman. In it she is bound for all time.

To her husband she owes the duty of

unqualified obedience. There is no

crime which a man can commit which

justifies his wife in leaving him or

in applying for that monstrous thing,

divorce, (continued on page 11)

11

Under this "double standard", men are

expected to be sexual teachers of their

virginal wives, and their sexual experi- * I

7/ (Con't)

It is her duty to subject herself to

him always, and no crime that he can

commit can justify her lack of obedience.

If he be a bad or wicked man, she may

gently remonstrate with him, but refuse

him never. Let divorce be anathema;

curse it! curse this accursed thing,

divorce; curse it ! curse it! Think of

the blessedness of having children. I

am the father of many children and there

have been those who have ventured to

pity me. 'Keep your pity for yourself',

I have replied, 'they never cost me a

single pang' . In this matter let women

exercise that endurance and loving sub

mission which, with intricacy of thought,

are their only characteristics." Re

printed in E. Hecker, A Short History

of Women's Rights 151-152 (Putnam, 1910) .

12

ences outside matrimony are to be con

doned, because the blame for such ex

periences is upon the immoral, seducing

female.—^

To adherents of that double standard

of human sexual behavior, the mother of

"illegitimate" offspring symbolizes

defiance of the moral order: she is a

woman who is publicly known not to be

virginal and she is unmarried. So she

has been the bearer of many and diverse

punishments, often involving deprivations

upon her child or children, intended to

make her suffer for her violation of the

double standard. Even where the child

is not the direct object of punishment,

8/ O.S. Fowler, Perfect Men, Women and

Children 180 (1878); Mark Twain,

Letters From The Earth 40 (1962).

13

the child too suffers:

"... illegitimate pregnancy

is in itself a great blotch

upon a woman's virtue. Hence,

in so far as the child iden

tifies himself with his

physical mother — as he is

bound to do in our culture —

he will profoundly be affected

by the knowledge of his ille

gitimacy ...". 9/

Under the double standard of sexual

morality, the woman who does not dedicate

herself solely to child-rearing within

marriage has been viewed by religious,

social and legal authorities as a vio

lator of the basic natural order of

9/ Davis, "Illegitimacy and the Social

Structure", 45 A m . J . Soc. 215, 228,

231-233 (1939) .

14

humanity.— ^ The double standard is thus

preserved where women are relegated to

giving to society, and to receiving from

it, only those values afforded by marriage

and family roles; other kinds of exchanges

of values between woman and society —

10/ "It has often been said that a person

born out of wedlock, the parents of

that person (the mother much more so

than the father), and sometimes the

entire family of the mother, suffer a

stigma as the result of the nature of

the birth. Words as strong as

'discredit', 'disdain', 'shame',

'contempt' and 'condemnation' have

been used to describe that stigma.

When it exists, it impairs the social

position, not only of the person born

out of wedlock, but also the mother,

thus constituting for her an obstacle

to the realization of a normal life

in the community in which she lives."

Secretary of the United Nations,

Report: "The Status of the Unmarried

Mother: Law and Practice" 56 (1971) .

15

including education, non-domestic

employment, voting, office-holding, jury

service and ownership of property -- have

been publicly disapproved and legally

prohibited^

In the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries, Western political and relig

ious authorities battled openly against

movements for equal rights for women,

positing that legal freedom of women would

lead to the demise of marriage and family

11/ A summary of these legal disabilities

may be found in L. Kanowitz, Women

and the Law: The Unfinished

Revolution passim (1969). More de

tailed discussions are presented in

Davidson, Ginsburg and Kay, Sex-Based

Discrimination (1974) and in Babcock,

Freedman, Norton & Ross, Sex

Discrimination and the Law: Causes

and Remedies (1975).

16

structures.— For example, the Church of

England campaigned against contraception

as part-and-parcel of its opposition to

12/ W. Chafe, The American Woman 5, 9-11

(1972); Hankins in "Illegitimacy:

Social Aspects", 7 Encyclopaedia of

Social Sciences 579, 580-81 (1932)

states in part: "Viewing woman as the

chief source of sin Christianity tend

ed to degrade motherhood, to accentuate

masculine supremacy and to maintain a

double standard of morality. It thus

inflicted an often unbearable cruelty

upon the unmarried mother and an almost

certain degradation upon her off-spring.

In medieval and early modern times the

mother was often required to confess

her sin before the congregation in

both Catholic and Protestant Communi

ties; and she was sometimes fined,

sometimes publicly whipped, sometimes

placed in stocks, and the child was

neglected and socially ostracized,

while the father suffered little or

no penalty."

12/

17

the emancipation of women.— Those who

spoke of contraception as a means by which

the status of men, women and children

might be improved were scorned and cast

14/out for their radicalism.— The idea that

13/

13/ "The Church of England was slower to

face the challenge presented by new

social conditions -- particularly the

growing demand for women's emancipa

tion -- and was more reluctant to

change its traditional doctrine about

sex, marriage and the family... Regret

was expressed at the decline of the

birth rate among English-speaking

peoples, especially the upper and

middle classes, and it was suggested

that many physical and mental diseases

might be a direct consequence of the

use of contraceptives. The bishops

(footnotes omitted), having denounced

birth control as "preventive abortion",

recommended that all contraceptive

appliances and drugs be prohibited by

law and their advocates prosecuted."

F. Campbell, "Birth Control and The

Christian Churches" 14(2) Population

Stud i e s 142 (1960).

14/ See for example the discussion of

Francis Place's paper of 1822, entitled

"To The Married of Both Sexes of the

Working People", at G. Hardin, e.d..

Population, Evolution and Birth Control

192-193 (1969).

18

contraception, abortion and "illegitimate"

pregnancy directly violated the proper

role of women and together threatened the

institution of marriage itself was also

given voice by medical professionals, in

spired by religious campaigns against fe-

male social and legal equality.— ^

15/Isaac Pierce, M.D., writing for the

Medical and Surgical Reporter in 1888,

states in pertinent part:

"Every man knows the horrors of illicit

love and the suffering of misguided

though patient and confiding women; no

man is insensible to the lifelong shame

of a child thrown upon the world with

out knowing a father, and no man denies

the wickedness of criminal abortion. No

medical man doubts the suffering, and in

many cases permanent injury, of the

woman who practices abortion that she

may shield herself and her destroyer

from the condemnation of the world...

Let it become generally known that the

medical profession countenances a pre

ventive even in a few cases, and there

is reason to fear this will be stretch

ed to a license which will work much

mischief to women who are already ex

perimenting in this direction, who have

no reason why they should not fulfill the

God-given function which makes happy

homes, and who are now only held in check

by the judgment of the world."Pp. 614-616.

19

Integral to preservation of the model

of the adult female as fit only for the

roles of wife and mother were drastic

constraints upon her access to the

educational system in this nation. From

the inception of the educational system

of this nation, the opportunities of

women for employment in that system have

been profoundly and consciously manipu

lated because of their female sex, marital

and maternal status. This pattern of

manipulation, commencing with total pro

hibitions against female teachers— ^and

reaching almost to the present through

categorical restrictions upon employment

17/of pregnant teachers— , has been con-

16/ R. Callahan, An Introduction to Edu

cation In American Society 383-384

(1956) .

Brief Amicus Curiae For The National

Education Association et al., in Cleve

land Board of Education v. LaFleur, Sup.

Ct. No. 72-777 , at p p . 10-14 (1972).

17/

20

sistently intertwined with vindication of

the above-described double standard of

human sexuality and the "woman's place"

model of female rights and responsibilities.

So it was that prior to 1830, the United

States' public teaching profession was

18/composed almost exclusively of men.— ' A

movement to include women as teachers,

commencing in the 1830's and culminating in

a great influx of women into the teaching

profession during the Civil War, contri

buted demonstrably to the general enhance

ment of women's employment opportunities,

and increased public respect for the social

19/contributions of women— Married women were

nonetheless widely prohibited from teach

ing and related occupations until World

18/ W. Elsbree, The American Teacher 199

(1939).

19/ Id. at 201-207.

21

War I, — 'and many such prohibitory laws

and policies were re-established after

21/World War I— and again after World War

22/II.— The fundamental basis of these

exclusions appears to have been an ad

mixture of sentiments about the morally

damaging and hazardous influence of

23/married women upon students— and sex-

2 0 /

20/ C. Atkinson & E. Maleska, The Story

of Education 346-347 (1965).

21/ I. Woody, A History of Women's

Education In The United States 509,

513 (1966).

22/ Id.IITh e employm ent of ma rried wo men

teac her s in the pu b li c schoo 1s of theuni ted State s ha s eve r been a con-

tr oV er sial questio n . Custom has 1o ng

dec reed tha t the scho o 1 ma 1 am be ce1-

iba t e and mo st sch oo 1 board s not on iyre fu s e to emp ioy ma r r ied wornen , bu t

a1 so s tipula te tha t th e empl oyed un -

mar ried t eac her mu st re s ign her po si -

tio n a s soon as sh e becomes a wife . ii

Don ovan , The schoo i Ma ' am 57 (S tok es

Co . 193 8) .

22

based economic notions about male bread

winning and female domesticity in family

4- 4. 24/structure.—

Like their historical predecessors,

who first excluded all women, and who

next excluded married women, from teaching

and related occupations, petitioners

in this case claim that their policy is

designed solely to improve the moral

stmosphere of schools by removing women

who have chosen a course of personal con

duct that is believed to convey a bad

24/ "Opposition to the employment of

married women as teachers is generally

recognized as stronger in smaller

rather than larger city systems. In

smaller communities there still pre

vails the traditional attitude that

woman's place is in the home, that

her husband is expected to provide an

income for the maintenance of the

family, and that his prestige depends

upon his ability to do this." Id

at 60 .

23

example to students. In this way,

petitioners' policy joins a long line of

sex-discriminatory laws, policies and

practices, purportedly directed at

manipulating the image of women in

public education in order to transmit a

particular moral philosophy to students.

24

B. Petitioners' Exclusion

Of Unmarried Mothers

From Employment Menaces

The Achievement Of

Equal Opportunity By

Women.

Proposals to create equal employment

opportunities without regard to sex are at

least as ancient as Plato's Republic

Alongside such philosophical ideas about

the means to equality, the reality stands

that:

"...(n)o society has restruc

tured both the occupational

system and the domestic

establishment to the point

of modifying the old divi

sion of labor by sex." 27/

As Justice Brennan observed in the plural

ity opinion in Frontiero v. Richardson,

26/ In Chapter XV, Socrates explains how the

principle of equality of the sexes should

work. F. Cornford trans., The Republic of

Plato, 144-155 (1966).

27/ K. Davis, "Population Policy: Will Current

Programs Succeed?", 158 Science 736-737

(1967).

25

411 U.S. 677 (1973), sex discrimination

in employment continues to confront women

in the United States, in spite of legis

lative and judicial efforts to overcome

it.

The notion that women can avoid

employment discrimination because women

are free to forego the non-domestic work

ing world has little validity in this

country, where a substantial and increas

ing proportion of the female population

works outside the home out of sheer econo-

mic necessity.— ' In families whose sole

breadwinners are females, the economic

need to work is obviously most intense.

Yet the very families whose livelihood is

28/ As of 1970, there were 5.6 million families

headed by women in the United States, of

which almost one-third had family incomes

below the poverty line of $3,700 for a

family of four. R. Stein. "The Economic

26

cut off by petitioners' exclusion of

mothers of illegitimate" children from

employment are within this most economi

cally needy group.

There can be no doubt that access

to employment free from invidious dis

crimination has paramount significance in

the realization of equal employment oppor

tunity under law. Petitioners' exclusion

strikes multiple blows against the un

married mother whose employment provides

her family's livelihood: the excluded

mother is deprived of economic self-

sufficiency; she is foreclosed from making

the contribution to society that her work

affords; not only is the principle of

equal opportunity violated, but the means

28/ cont'd.

Status of Families Headed By Women", in U.S.

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statis

tics, Monthly Labor Review (Dec. 1970).

27

of making that principle real and of giv

ing it meaning - employment - is taken

from her by petitioners, for the rest of

her life.

II. PETITIONERS' POLICY DISCRIM

INATES AGAINST FEMALES IN

VIOLATION OF THE CONSTITU

TIONAL GUARANTEE OF EQUAL

PROTECTION.

A. Petitioners' Policy Is

Facially Sex-Discriminatory.

Amici contend that the policy of

petitioners herein at issue warrants treat

ment by this Court as a facially sex-dis

criminatory policy, for four reasons.

First, the actual phrasing of the unwritten

policy, effectuated in the form of an oral

instruction to exclude unwed mothers from

employment, contained that sex-based clas

sification. Second, regardless of the

wording of the unwritten policy, it was

designed and structured in direct reliance

upon the greater identifiability of

28

mothers than of fathers of "illegiti-

.,29/ children. Third, under Missis-

I l ia t c ------

sippi law, fathers may take action to

legitimate their children born out of

wedlock, thus escaping the exclusion from

employment, whereas mothers are legally

incapable of doing so. Fourth, the

declared purpose and the method of enforce

ment of petitioners' policy assure that

it will not reach and exclude male parents

of "illegitimate" children from school

district employment.

The record in this action fully sus

tains the position that petitioners'

policy was articulated to find and exclude

29/ In 1945, Justice Schauer of the California

Supreme Court opined that it would seem

fairer to refer to the offspring of unmarried

parents as the morally neutral children of

"illegitimate parents". Estate of Lund,

26 C.2d 472, 159 P.2d 643 (1945). Amici have

placed the term "illegitimate" in quotation

marks throughout this Brief because they

29

from employment a class composed solely

of women. Under cross-examination, Super

intendent Pettey, who designed the policy

(P.T. 3), admitted that his instruction

to Mrs. McCorkle, who was charged with

investigating and recommending certain

applicants (P.T. 11), specifically con

sisted of a prohibition against hiring

unwed mothers (P.T. 28) and that he gave

Mrs. McCorkle no instructions whatsoever

as to exclusion of male applications who

had fathered "illegitimate" children

(P.T. 23-24).

Moreover, there is a compelling

reason to define the face of petitioners'

policy as consisting of the exclusion of

unwed mothers from employment. Because

29/ cont'd.

believe that, whatever group the term is

used to modify, it invites injustices.

(See Section I, above.)

30

the policy remained an unwritten one to

and through the trial below, for this

Court to define the face of the policy as

consisting of the phrasing given to it in

the adversary context of litigation, by

its defenders, would work a serious mis

chief. Such a judicial definition of the

policy's face would encourage governmental

authorities to propound unwritten policies

containing overtly discriminatory classi

fications, and subsequently to give clear

and neutral-seeming phraseology to such

policies only if and when challenged under

the Constitution. Cf. Niemotko v. Mary

land , 340 U.S. 268 (1951). Even the more

neutral-seeming phrasings— ^ of the policy

30/ At one juncture Superintendent Pettey stated

that the policy excluded unwed parents. (PT

23,24.) At a second juncture he stated that

the policy excluded parents of illegitimate

children (P.T. 3, 15.) At a third juncture,

as discussed hereinabove, Superintendent

31

do not redeem it from its facially sex-dis

criminatory character.

Both in structure and in the purported

justification of their policy, petitioners

have relied directly and impermissibly

upon the greater identifiability of mothers

31/than of fathers.— Indeed, in their

30/ cont'd.

Pettey indicated that he instructed Mrs.

McCorkle to exclude unwed mothers. (P.T.

28.)

31/ In the case of Sanders v. Tillman, 245 S .2d

198 (Sup. Ct. Miss. 1971), which offers the

most recent definition of "legitimation"

under Mississippi law, the Supreme Court

of Mississippi observed in relevant part:

"It is a simple matter to prove the mater

nity of an illegitimate child, but is

infinitely more complex and difficult to

prove the paterntiy. It is only necessary

for the father to be present at the laying

of the keel, not at the launching of the

ship. The mother must be present at both,

and it is not at all difficult to prove who

launched the ship." 245 S.2d at 200.

32

answer to the complaint, petitioners as

serted that:

"...the regulation bears only

upon the Plaintiffs' open and

notorious display of a status

which is within the province

of the school district to regu

late in determining who may

teach." (Answer, p. 3, 1[XV.)

Generally only mothers would be capable of

such open display of unwed parenthood in

this culture. (It bears emphasis that, as

a matter of record, none of the respondents

in this case was at any time engaged in

any display whatsoever of her status as an

unmarried parent; to the contrary, agents

of petitioners affirmatively searched for

information as to the marital and parental

statuses of the respondents. (P.T. 9, 10,

28, 29; Mc.T. 13, 23, 24, 36, 37, 42)).

Furthermore, to the extent that peti

tioners are referring to the status of

being a childbearer out of wedlock, it

33

must be considered that no father is cap

able of such a status. To the extent that

the policy refers to the fact of child-

rearing, it must further be considered

that unwed fathers in this society do not

32 /generally rear their children.— Finally,

while Mississippi law provides a means by

which a father may legitimate his offspring

born out of wedlock, no such legal means

is available to the mother; the father may

marry the mother and acknowledge the child,

3 3/rendering it legitimate.— Thus it

emerges that petitioners' policy, insofar

as it purportedly excludes parents of

"illegitimate" children from employment,

operates in a context of state laws that

32/ See footnote 36, infra.

33/ Cf. Sanders v, Tillman, footnote 31, supra;

see also, Nichols v. Sauls' Estate, 165 S.2d

352 (Sup. Ct. Miss. 1964).

34

empower fathers, and not mothers, to legit

imate their children and thus to avoid

exclusion from employment.— ^

The structure of petitioners' policy

inexcusably disfavors the female parent

vis a vis the male parent, even aside from

its tandem operation with Mississippi's

laws governing legitimation. This Court

fully realizes the statistical infrequency

of the phenomenon of single male persons

35/who are the custodial parents of children-,— ■

Within this phenomenon, the father who is

the custodial parent of his child conceived

and born out of wedlock must be uncommon

34/ In several states, acknowledgement by the

father without marriage accomplishes full

legitimation. H. Krause, Illegitimacy:

Law and Social Policy 19 (1971).

35/ Cf. Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645

634-656 (1972).

35

3 6/indeed.— ■ Thus, by its reliance upon the

fact of custody to locate parents of

"illegitimate" children, the structure of

petitioners' policy excludes fathers by

means of the virtual impossibility of lo

cating a male custodial parent of an

"illegitimate" child.

Petitioners have made two essentially

irreconcilable contentions about the

36/ Id. As of 1970, 98.67% of all persons under

18 years old in the United States were

living either with both parents or with

a female head of family. U.S. Bureau of

the Census, 1 Characteristics of the

Population Table 54, p. 1-278 (1970).

Only 0.2% of all persons under 18 years

old were living with fathers who were

single (i.e., never married, separated,

widowed or divorced). U.S. Bureau of the

Census, Subject Reports: Persons By

Family Characteristics 1 (1970).

36

relationship between their policy and the

group of female parents of "illegitimate"

children excluded thereby. On the one

hand, petitioners claim that males and

females who engage in conduct resulting

in the birth of an "illegitimate" child

are equally bad role models in instruc

tional contexts, and that they are there

fore equally subject to the exclusion from

employment under that ostensible purpose.

On the other hand, as the portion of the

answer quoted above (see text after foot

note 31) emphasizes, and as District Court

Judge Ready below observed:

"Defendants argue that when

a single woman engages in

premarital sexual relations,

become pregnant and begets

an illegitimate child, she

voluntarily places herself

in a classification in which

men are not similarly sit

uated, and hence, a regula

tion which treats women

differently is justified."

371 F.Supp. 26, 36.

37

Thus, there is little doubt that

petitioners' policy, by its language,

structure, method of enforcement and

declared purpose of regulating "open and

notorious display" of the status of unwed

motherhood, treats women differently from

men. In terms of petitioners' own position

that both parents of "illegitimate" off

spring are bad role models in instruction

contexts, the sex-differential compass of

petitioners' policy, which encircles

mothers and omits fathers of "illegitimate"

children, is unjustifiable.

38

B. As Applied, Petitioners'

Policy Discriminates

Against Women.

The factual record in this action

underscores the sex-discriminatory fashion

in which petitioners' policy has been

administered. The assertion that the

policy is to be applied to both sexes is

belied on the face of the record: under

the policy, five females and no males have

been excluded from school district employ

ment (M.c.T. 14, 20, 42). Section II-A

demonstrated that petitioners' policy is

structured to find and exclude women.

Amici contend that this "women only" result

should therefore be viewed as the utterly

predictable consequence of a facially

discriminatory classification. However,

even were the policy deemed fair and neu

tral on its face as to the sex of persons

to be excluded from employment, the policy

39

represents a classical situation of dis

criminatory application.

The doctrine that illegal discrim

ination accomplished by application of a

neutral-seeming law will not be counte

nanced is a long-standing element in the

strength of the United States Constitution.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

As in Yick Wo, the Court here is con

fronted by a record evincing a wholly

unequal application, as between persons

similarly situated, of a governmental

prohibition materially affecting those

persons' rights. The administration of

petitioners' policy invites and assures

continuation of this unequal application,

in that petitioners have depended frontally

upon the reality, rooted in biology, state

law and maternal custody patterns, that

mothers of "illegitimate" children are

40

usually identifiable and excludable where

fathers, similarly situated under the

purported purposes of the policy, are not.

As in Yick Wo, the petitioners' policy

here has been unequally and discrimina-

torily administered, and it must fall.

C. Petitioners' Policy Fails

Every Test Of Equal Pro

tection To Be Guaranteed

To Women In The Context

Of Public Employment.

Both on its face, and as applied to

respondents, petitioners' policy achieves

a discrimination against women as mothers

of "illegitimate" children. That dis

crimination is wholly unjustifiable under

the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of

equal protection.

The policy of petitioners does not

begin to fulfill the rigorous rational

basis test of equal protection to women

and men propounded by this Court in

41

Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971). As

Chief Justice Burger reasoned therein:

"The Equal Protection Clause...

does, however, deny to States

the power to legislate that

different treatment be accor

ded to persons placed by a

statute into different classes

on the basis of criteria wholly

unrelated to the objective of

that statute." !Id. at 76-77.

Petitioners have insisted that the purpose

of their policy is to exclude from in

structional employment persons who, by

virtue of their participation in out-of-

wedlock sexual intercourse that results in

"illegitimate" births, are immoral role

models for students.

Petitioners' policy bears neither a

fair nor a substantial relationship to

the policy's declared purpose, as re

quired for equal protection purposes by

Reed v. Reed, supra. The criterion of sex

is wholly unrelated to the policy's pur

42

pose, which is to exclude bad role models

from employment. Surely the father of

"illegitimate" offspring is as much or

37/as little a bad role model— as the mother

yet, because of his sex, he is outside the

policy's structure and enforcement scheme.

Thus it appears that petitioners' policy

bears no demonstrable relationship to the

declared end.

Wholly aside from its discrimination

on account of sex, the policy draws a set

of arbitrary lines among women, each of

which moves the policy further away from

the fair and substantial relationship to

the governmental purpose which, under

37/ For purposes of the discussion of

equal protection herein, amici have

assumed arguendo that petitioners'

"role model" theory has some factual

validity. However, the District

Court found that it does not, and

there is substantial evidence in

the record to support that finding.

43

Reed, the policy must bear. The pregnant

woman who elects abortion, or who abandons

3 8/or even destroys— ' her infant, is outside

the policy; it is only the woman who elects

to give birth and to fulfill custodial

responsibilities to her offspring whom

petitioners' policy excludes from employ

ment. By the "bad role model" theory of

petitioners, all of these women are en-

38/ "It bears emphasis that community

disapproval and penal sanctions a-

gainst the mother may intensify the

mother's desire to protect her

anonymity and rid herself of the in

fant. Although the incidence of

infanticide and abandonment are not

as great as they were in Puritan

days... the pressure on the modern

unmarried mother may result in either

illegal induced abortion or anonymous

release of the child for adoption."

C. Foote, R. Levy & F. Sander, Cases

and Materials On Family Law

118 (1966).

44

3 9/compassed— ; yet the policy arbitrary

selects only the last, and excludes her

from employment. Along with its

irrational line between men and women,

these additional lines drawn among women

by the policy underscore its lack of re

lationship to the purpose of excluding

"bad role models" from employment.

The case at bar does not require this

Court to reach the question, which has at

least once divided it, as to the proper

jurisprudential status of the category of

"sex" for equal protection purposes. Cf.

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677

(1973). Nonetheless, if this Court were

to view the policy of petitioners as

somehow capable of surviving the sub

stantial rationality test of Reed, we urge

39/ The prospective mother of an "ille

gitimate" child who elects abortion

is a double sinner, in some views.

See footnote 15/, supra.

45

that the reasons for holding sex to be a

suspect category, delineated by Justice

Brennan in Frontiero v. Richardson,

supra, should be found wholly persuasive

in the instant case. By the language,

structure and method of enforcement of

their policy, petitioners have targeted

mothers, because of their sex, for ex

clusion from employment in a fashion that

makes these women the direct victims of a

poorly designed and ill-considered form

of behavioral architecture.— ^ Petitioners'

40/ See Section I. A-B., above. The

exclusion from employment of men in

order to encourage marriage and pro

creation would seem to be every bit

as ill-considered, although at least

one public minister, J.L. Muret of the

canton of Vaud, Switzerland, suggested

it in 1766, saying "... A means which

would seem very efficient, and be the

more appropriate since it would en

hance population more directly, would

be to bar from all employments the

non-married men...". J.L. Muret,

Memoire sure 1 ' etat de la population

dans le pays de Vaud", in Memoires de

la Societe Economique de Berne 57 (17 6 6).

46

policy represents an unwarranted return to

the times during which stigmatization of

unwed mothers was a tool, along with

forced pregnancy, compulsory marriage and

deprivation of birth control information,

by which women were kept in their legal

41/and societal places— The policy thus in

vokes the historical and legal reasons for

holding that sex, like race, should be

viewed as a suspect category for equal

protection purposes. Whatever changes may

be promised or predicted on the road to

equal opportunity without regard to sex,

the stigmatization and exclusion from

public employment of women who bear

"illegitimate" children can only be viewed

as a backward step. Amici urge that this

41/ See fn's 12_ / , 13/ , and 15/ , and

accompanying text, supra.

47

Court find that policy of denying employ

ment to unwed mothers, while allowing un

wed fathers to teach, violates the most

stringent test of equal protection.

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, as

well as those urged by respondents, the

decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

/*/MARY C. DUNLAP

NANCY L. DAVIS

JOAN MESSING GRAFF

WENDY W. WILLIAMS

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc.

433 Turk Street

San Francisco, California

94102

RUTH BADER GINSBURG

MELVIN L. WULF

KATHLEEN WILLERT PERATIS

SUSAN C. ROSS

American Civil Liberties

Union

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

48

Attorneys for Amici gratefully acknow

ledge the assistance of Roberta Dempster,

Julia Jaurigui, Jill Nelson, JoAnn

Novoson and Kathy Purcell in the pre

paration of this Brief.

W t l^ - c r

' i O

i . r

0 vJjQ.i

S U I T E 2 0 3 0

10 C O L U M B U S C I R C L E

N E W Y O R K , N. Y. 1 0 0 1 9