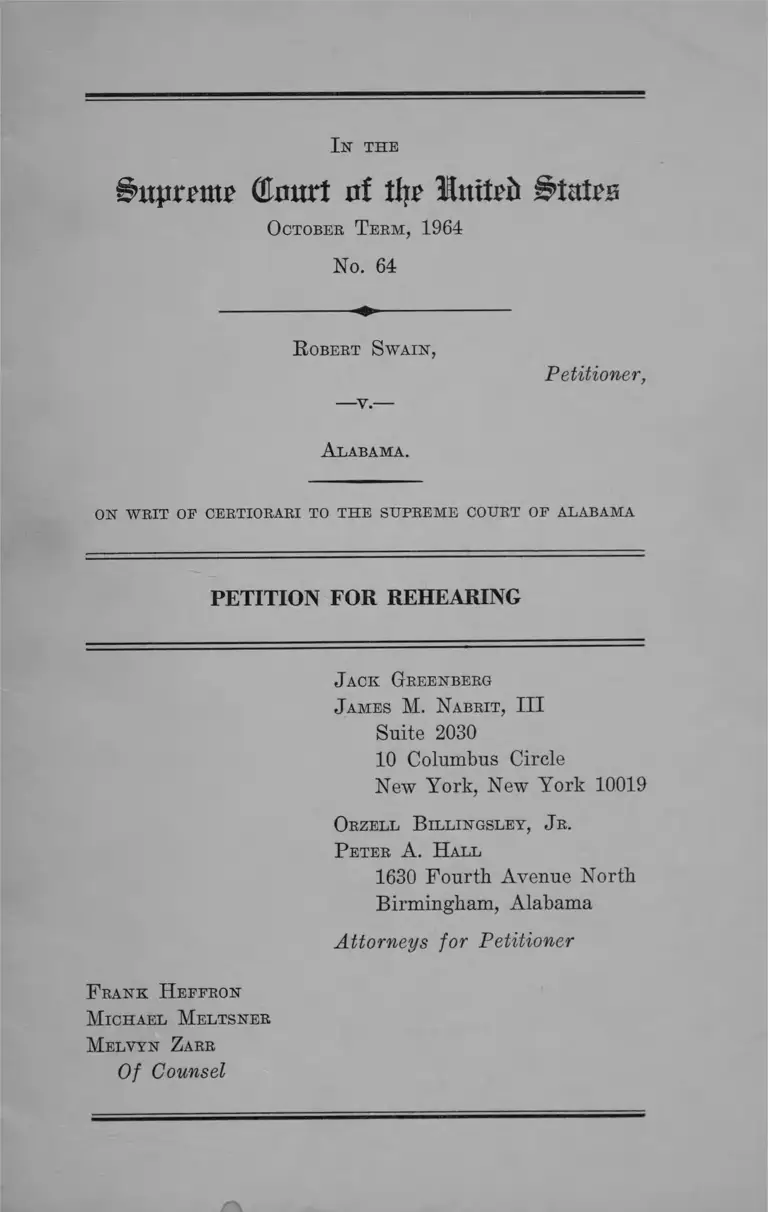

Swain v. Alabama Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swain v. Alabama Petition for Rehearing, 1965. 839bcb8a-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1761c6a6-cadb-4c5c-8224-dfa53427de0c/swain-v-alabama-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

§upmttp GJourt of tfro llnxtzb States

October T erm, 1964

No. 64

In the

R obert Swain,

—v.—

A labama.

Petitioner,

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP ALABAMA

PETITION FOR REHEARING

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

F rank H eepron

Michael Meltsner

Melvyn Zarr

Of Counsel

I N D E X

I. The Rationale of the Court’s Rejection of Peti

tioner’s Claim of Exclusion of Negroes From Jury

Venires Represents a Sharp Departure From Pre

vious Decisions and Entails Grave Consequences

Not Adequately Considered in the Briefs or the

Argument or the Opinion of the Court .............. 2

II. The Court Apparently Did Not Adequately Appre

ciate the Extent to Which Racial Discrimination

Infects the Jury Selection Process in Talladega

County .......................................................................... 10

Conclusion............................. 11

Certificate of Counsel............... 13

Appendix ........................................................................... la

T able op Cases

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 .............................. — 10

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773 ...................... 4

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 .................... ............. 6

Bailey v. Ilenslee, 287 F. 2d 936 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 4

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 II. S.

715 ................. ................................................................. 7

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ................................ . 3, 4

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 .............................. 12

PAGE

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 .................... ......... 6, 7

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261..................................... 9

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 ............................................ . 9

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U. S. 52 .............................. 12

Harper v. Mississippi, ------U. S .------- , 171 So. 2d 129

(1964) ............................................................................. 4,5

Henslee v. Stewart, 311 F. 2d 691 (8th Cir. 1963) ___ 4

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 .......................................... 7

Louisiana v. United States, 33 U. S. L. Week 4262 ....... 6, 7

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 .................................... . 3

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ................... .................. 4, 7

Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 600 .............................. 12

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463 ..... ..................... 4, 6

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .............. 10

Powell v. Alabama, 387 U. S. 4 5 ..................................... 12

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 .................................... . 4

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723 ................................. 7

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ...................... 3

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 ..................................... 9

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959) ............................................................ 4,5

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1962) ........................................................................ 4, 7

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F. 2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) ....... 5

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 .................................. 12

11

PAGE

iii

PAGE

Statutes:

18 U. S. C. §243 ............................... ...................... ......... 9

Alabama Code, Tit. 30, §21 (1958) ............... ...... ....... 5

North Carolina G. S. §9-1 .................. .......................... 4

Other Authorities:

Marshall, Federalism and Civil Rights (Columbia Univ.

1964) ............................................................................... 5

Prettyman, Death and the Supreme Court .............. . 12

In the

§uprmtu> Court of % llnxUb States

October T eem, 1964

No. 64

R obert Swain,

Petitioner,

A labama.

ON WBIT OP CEETIOEAEI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP ALABAMA

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Petitioner respectfully urges the Court to rehear this

capital case for the following reasons:

1. The opinion of the Court establishes rules governing

proof of racial discrimination in jury selection which, as

a practical matter, will be incapable of administration at

the trial level wherever a jury commission has been com

pelled to abandon exclusion of Negroes and has moved to

token inclusion.

2. The opinion of the Court reflects incomplete appre

ciation of evidence in the record demonstrating state-

initiated racial distinctions infecting the jury selection

process.

2

I.

The Rationale of the Court’s Rejection of Petitioner’s

Claim of Exclusion of Negroes From Jury Venires Rep

resents a Sharp Departure From Previous Decisions

and Entails Grave Consequences Not Adequately Con

sidered in the Briefs or the Argument or the Opinion

of the Court.

The Court holds that petitioner has failed “ in this case

to make out a prima facie case of invidious discrimination

under the Fourteenth Amendment”, 33 U. S. L. Week 4231,

4232, because there was no “meaningful attempt to demon

strate that the same proportion of Negroes qualified under

the standards being administered by the commissioners” ,

33 U. S. L. Week at 4233, and “purposeful discrimination

based on race alone is [not] satisfactorily proved by show

ing that an identifiable group in a community is under

represented by as much as 10 per cent”, 33 U. S. L. Week

at 4233.

A. No prior decision of this Court has required as part

of establishing a prima facie case a showing that Negroes

are as well qualified as whites. On the contrary, the rule

of exclusion, as it has been known heretofore, has required

only a showing of a class constituting a distinct portion of

the population and a pattern of systematic non-representa

tion of that class, whereupon the state has been required

to justify that non-representation. Both petitioner and

respondent argued this cause on the premise that the

burden of showing inequality between the races rested on

the state, and the state attempted to assume that burden

at the hearing in the Circuit Court through the use of

spurious and irrelevant statistics on the incidence of ve

nereal disease and receipt of public assistance. The burden

of showing equality between the races is not one which a

3

Negro petitioner may realistically be expected to meet, and

this Court should not place that burden upon him without

considering briefs and arguments directed squarely toward

the issue.

The Court appears, from its opinion, willing to entertain

a rebuttable presumption that Negroes as a class are not

as well qualified as white persons under constitutionally

acceptable standards. Such a presumption flies in the face

of the teachings of the Court since the turn of the century.1

Moreover, if the incidence of disqualifying factors is

higher among Negroes in a given county, the jury commis

sioners, who presumably have observed these factors, will

be easily in the best position to offer proof of them; then

the Negro defendant will be justly put to his proof in re

buttal. But this is a far different thing from a presumption

by the Court of racial inequality.

The rule to date, as petitioner understood it, was as

stated in Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282. There, Mr. Justice

Reed, announcing the judgment of the Court, pointed out

that although Negroes constituted 15.5% of the population,

they constituted only 6.7% of the grand jury panels—a

discrepancy of the same order of magnitude as that pre

sented in the instant case. Mr. Justice Reed’s opinion held

that:

An individual’s qualifications for grand-jury service,

however, are not hard to ascertain, and with no evi-

1 Such a rule conflicts with the purpose of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, see Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 306, for it

implies that Negroes are known to be less qualified and should

therefore prove that they possess the same qualifications as whites.

Attempts to impose such a burden have been rejected in the past.

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, for example, reversed a “violent

presumption” of a state court that Negro exclusion was due to

their lack of qualifications.

4

dence to the contrary, we must assume that a large

proportion of the Negroes of Dallas County met the

statutory requirements for jury service. 339 IT. S.

at 288-289.

Also, in Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773, the Court

found a prima facie showing of jury exclusion, absent

proof of the qualifications of Negroes in the community.2

See also Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85, 88 (the burden on

the state); Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463, 468; Norris

v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 591 (Negroes 7.5% of the popu

lation, none on juries; prima facie case of denial).3

The lower courts—which must actually administer any

rule required by the Court—have also placed the burden on

the state to prove that Negroes are not as well qualified

as whites. The United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit has held that the burden is on the state, not

Negro defendants, to show that voter registration officials

freely and fairly register qualified Negroes as electors, if

such is the standard for jury service, because “ the fact

[rests] more in the knowledge of the State.” United States

ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71, 78 (5th Cir. 1959).

That decision was followed in Harper v. Mississippi,------

Miss. ------, 171 So. 2d 129 (1964).4 This Court’s decision

2 No proof was offered of intelligence and good character, the

qualifications for jury service provided by North Carolina G. S.

§9-1.

3 To be sure, the Court has always treated evidence of the quali

fications of Negroes as relevant, Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587,

598, but there is no suggestion in the cases that one claiming dis

crimination must affirmatively show that Negroes are as well

qualified as whites.

4 See United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53, 59

(5th Cir. 1962), where the Court relied upon the fact that “ [t]here

was no testimony . . . that, on the average, Negroes in Mobile

County are any less qualified for jury service than are whites.”

See also Bailey v. Henslce, 287 F. 2d 936 (8th Cir. 1961); Henslee

v. Stewart, 311 F. 2d 691 (8th Cir. 1963).

5

would have forced the defendant in both Goldsby, supra, and

Harper, supra, to show that Negroes were as well qualified

as whites to meet the selection standards of the state as to

voter registration, a task difficult enough for the Depart

ment of Justice,5 and no doubt impossible for individual de

fendants. It must be remembered that virtually all Negro

defendants in capital cases are indigent and usually are rep

resented by local Negro counsel whenever the jury issue is

raised, see United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, supra

at 82; Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F. 2d 496, 506-07 (5th Cir.

1964). Such Negro counsel are few and far between and are

unlikely in the extreme to have available the investigative

staffs which the state can muster.

Given the jury selection standards in Alabama and in

deed in other states,6 the evidence almost entirely within the

knowledge of state officials ought to continue to come from

them, as it has in the past. The entirely subjective stand

ards of juror qualifications of Ala. Code, tit. 30, §21 (1958)

(“ esteemed in the community for their integrity, good char

acter and sound judgment” ) coupled with the vague and ad

hoc procedure approved by the Supreme Court of Alabama

make it virtually impossible for a defendant to show “ that

the commissioners applied different standards of qualifica

tions to the Negro community than they did to the white

5 The former Assistant Attorney General who headed the Civil

Eights Division has stated, “The federal government has demon

strated a seeming inability to make significant advances, in seven

years time, since the 1957 law, in making the right to vote real

for Negroes in Mississippi, large parts of Alabama, in Louisiana,

and in scattered counties in other states.” Marshall, Federalism

and Civil Rights (Columbia Univ. 1964), p. 37. A crucial aspect

of proposed bills to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment is a shift

ing of the burden of proof to the county concerned rather than

the Department of Justice.

6 See Appendix at p. la, infra.

6

community.” 33 U. S. L. Week at 4233. It is totally un

realistic to believe that a Negro defendant, faced with the

scheme of a jury selection law “ completely devoid of stand

ards and restraints,” Louisiana v. United States, 33 U. S. L.

Week 4262, 4264, which vests “ a virtually uncontrolled dis

cretion,” id. at 4263, in jury commissioners, will be capable

of showing “ that the same proportion of Negroes qualified

under the standards being administered by the commis

sioners,” U. S. L. Week at 4233. This evidence is peculiarly

within the knowledge of those who select the jurors. If

Negroes are not as well qualified as whites, then the jury

commissioners will have encountered these differences and

will be able to produce meaningful evidence of them.

Finally, it is said that the disparity between the percent

age of Negroes on the jury venires and the percentage

in the eligible population is not sufficient to make out a

prima facie case, because, while the selection process is

“haphazard” and “ imperfect,” there is no proof it reflects

a “ studied” or “purposeful” attempt to discriminate. Lan

guage implying the necessity for proof of intentional dis

crimination has appeared in some of the decisions of the

Court, but it has been thought that the only proof required

was that a system or course of conduct operate in a dis

criminatory manner. In Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559,

the Court disapproved a jury selection procedure whereby

names of members of the white and Negro race were put

on different colored tickets; the Court held that the Negro

defendant’s prima facie burden had been met by showing

a system susceptible of operation in a racially discrimina

tory manner and that the state had the burden of showing

that purposeful discrimination had in fact not occurred.’ 7

7 See also, for example, the explicit language of Patton v. Mis

sissippi, 332 U. S. 463, 469, reaffirmed in Eubanks v. Louisiana,

7

But as Mr. Justice Clark said in Burton v. Wilmington Park

ing Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 725, “ It is of no consolation

to an individual denied the equal protection of the laws

that it was done in good faith.” And see, Rideau v. Louisi

ana, 373 U. S. 723, 726, where the question of who initiated

the television interview of the defendant’s confession was

“ irrelevant” ; the fact that it was televised to the community

was dispositive.

The requirement of proof of “ purposeful” discrimination,

as well as the requirement that Negroes prove that they are

as well qualified as whites, will in practice, tend to restrict

the prohibition of the Fourteenth Amendment to total ex

clusion, for it is virtually impossible to show a subjective

desire to discriminate or to show a misapplication of stand

ards, when vague and subjective standards are applied by

a jury commissioner “ at his own sweet will and pleasure,”

Louisiana v. United States, supra, 33 IT. S. L. Week at 4264.

B. The Court found “the over-all percentage disparity”

between the percentage of Negroes in the population and

the percentage on the jury venires “ small” , saying: “We

cannot say that purposeful discrimination based on race

alone is satisfactorily proved by showing that an identi

fiable group in a community is under-represented by as

much as 10%”, 33 IT. S. L. Week at 4233.

Petitioner submits that if numbers are to be used in this

manner, it should be noted that under-representation on

the grand jury was only 7.5% in Norris v. Alabama, 294

U. S. 587; moreover, a showing of a 10% Negro population

and 0% Negro jury participation would seemingly, under

the Court’s rationale, fail to meet a Negro defendant’s

prima facie burden of proving jury exclusion.

356 U. S. 584, 587. See also, Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400; as repre

sentative of the lower courts, see United States ex rel. Seals v.

Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53, 65 (5th Cir. 1962).

8

In this case, whereas 26% of the total male population

in Talladega County are Negroes, only 10%-15% of the

persons appearing on the grand and petit jury venires

have been Negroes; additionally, whereas Negroes have

served on 80% of the grand juries selected (the number

ranging from 1 to 3), no Negro has ever actually served

on a petit jury.

The discrepancy between 10-15% and 26% with respect

to the venires and the greater discrepancy with respect to

actual service on grand juries (in 20% of the cases, no

Negro served at all) results in an exclusion ratio of about

50% (10%-15% in relation to 26%). By reference to the

exclusion ratio rather than to the percentage discrepancy,

one would immediately realize that a Negro population

of 13% with 0% Negro jury participation presents a clear

prima facie case of discriminatory exclusion. The per

centage discrepancy there, as here, is about 13%, but the

meaningful figure is the exclusion ratio, which would there

be 100%. In this case the ratio is 50%, and the lower

courts might well read the instant decision as sustaining

discrepancies between a Negro jury participation of 20-

30% and a Negro population of 40-60%.

If an exclusion ratio of 50% is not sufficient to shift

the burden to the state, it is apparent that only complete

or virtual exclusion will be subject to judicial correction.

Admittedly, it may be difficult to draw a bright line at

which the burden will no longer be on the state. But where

the exclusion ratio is so large, the standards of jury

selection so subjective, the method of selection so “hap

hazard” and the knowledge concerning jury selection so

personal to the jury commissioners (who have not shown

Negroes less qualified than whites), petitioner submits that

trial counsel will have an intolerable burden in any case

where token inclusion is practiced.

9

C. The opinion of the Court places an intolerable burden

of proof on the Negro defendant in another respect also.

While acknowledging that unconstitutional discrimination

“may well” result if a prosecutor consistently—and re

gardless of trial considerations—exercises peremptory

strikes, so that no Negro could serve on a jury in any

criminal case, the Court avoids decision because petitioner

failed to make the necessary proof. It is respectfully sub

mitted that petitioner, having shown that no Negro has

served on any petit jury in Talladega County, should not

have to prove that the prosecutor abused his prerogatives.

Petitioner is obligated by the Court’s decision to place

the prosecutor on the stand to secure admissions about

his intentions during the striking process, admissions which

can be expected to be few since they would, in all proba

bility, be of an incriminating nature. See 18 U. S. C.

§243, Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261. The defendant in

an isolated criminal case, unfamiliar with the continuous

course of criminal prosecutions in the county, is unequipped

to give evidence on such matter as the prosecutor’s striking

practices, but the prosecutor is in an excellent position

to do so. He can easily establish the absence of a dis

criminatory pattern of peremptory strikes by showing that

Negroes have served on some juries or that defense counsel

bear a substantial portion of responsibility for the con

sistent striking of Negroes.

By placing on the defendant the burden of establishing

that the prosecutor struck Negroes for reasons unre

lated to the outcome of the case, the Court has formulated

a rule of law removed from the realities of trial strategy

and courtroom conduct. For all practical purposes the

petitioner will receive but illusory protection from Fay v.

Noia, 372 U. S. 391 and Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293,

because of the Court’s requirement that he adduce more

proof than he has already so laboriously placed on the

record in this case.

II.

The Court Apparently Did Not Adequately Appreci

ate the Extent to Which Racial Discrimination Infects

the Jury Selection Process in Talladega County.

Suppose that Talladega County had the following rule

of court:

In any case in which the defendant is a Negro, the

solicitor shall inquire of counsel for the defendant

whether he desires to have Negroes serve on the jury.

If counsel for the defendant does not desire them, all

Negroes on the venire shall be struck. In all other

cases jury selection shall proceed as otherwise required

by law.

No one for a moment would doubt that any conviction

occurring under such circumstances would violate the Four

teenth Amendment. Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399;

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244. The court

would not indulge in an inquiry as to whether counsel for

defendant would have arrived by his own “mental urges,”

373 U. S. at 248, at a conclusion to strike Negroes.

But this is precisely what happened here. The record

is clear that this solicitor, without variation, at the com

mencement of criminal eases inquired of counsel for the

defendant whether he desired to have Negroes on the jury:

If I am trying a case for the State, I will ask them

what is their wish, do they want them, and they will

as a rule discuss it with their client, and then they

will say, we don’t want them. If we are not going to

11

want them, if he doesn’t want them, and if I don’t

want them, what we do then is just take them off.

Strike them first (E. 27).

This is corroborated by other testimony of the solicitor:

Many times I have asked, Mr. Love for instance, I

would say there are so many colored men on this jury

venire, do you want to use any of them (E. 20).

This unseemly custom where the prosecutor invites con

sideration of jurors on the basis of their race appears to

be as invariable as a rule of court and no evidence in the

record qualifies this conclusion. Eegardless of the view

the Court takes as to what constitutes misuse of strikes, it

ought not approve such conduct on the part of a prosecutor.

CONCLUSION

By requiring petitioner to prove that Negroes are as

qualified as whites for jury service in Talladega County

the Court has ignored contrary precedents on which both

parties relied at the trial. Placing this burden on the de

fendant stigmatizes the Negro race and is extremely unfair

in practice. The Court also fails to attribute due signifi

cance to the disparity between the percentage of Negroes

in the county (26%) and their percentage on petit jury

venires (10-15%). Despite complete exclusion of Negroes

from petit jury service, the Court unfairly requires peti

tioner to show that the prosecutor was more interested in

banishing Negroes than in winning cases. In both cases

the burden is placed on virtually resourceless counsel for

indigent defendants in capital cases, while the state has

pertinent information and the ability to gather more.

Finally, the Court erroneously approved an unvarying prac

tice of prosecutor-mifwEed conferences with defense attor

12

neys as to whether Negroes should be stricken as a pre

liminary matter, a practice which if embodied in a formal

rule of court would be clearly unconstitutional.

This is a capital case,8 and petitioner respectfully urges

that it not be concluded without the most solemn considera

tion of the substantial practical and doctrinal propositions

urged herein, especially when the briefs and arguments of

the parties did not focus on several propositions adopted

by the Court for the first time.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

F rank H effron

M ichael Meltsner

Melvyn Zarr

Of Counsel

8 See, e.g., Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, 391 ( “ That life

is at stake is of course another important factor . . . ” ) ; Hamilton

v. Alabama, 368 U. S. 52, 55 (“When one pleads to a capital charge

without benefit of counsel, we do not stop to determine whether

prejudice resulted.” ) ; Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 241

( “Due process of law . . . commands that no such practice as that

disclosed by this record shall send any accused to his death” ) ;

Powell v. Alabama, 387 U. S. 45, 56; Patterson v. Alabama, 294

U. S. 600; and see generally, Prettyman, Death and the Supreme

Court.

13

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

The undersigned attorney for petitioner hereby certifies

that the foregoing Petition for Rehearing is presented in

good faith and not for delay.

T h is.......day of April, 1965.

Attorney for Petitioner

APPENDIX

Qualifications for Jury Service in Eleven Southern States

Voter Good Character

Alabama None Code of Ala., Tit. 30, §21: “Male citizens . . . gen

erally reputed to be honest and intelligent men and

esteemed in the community for their integrity, good

character and sound judgment.”

Florida Fla. Stat. Ann., §40.01 Fla. Stat. Ann., §40.01: “Law abiding citizens of

approved integrity, good character, sound judgment

and intelligence.”

Georgia None Ga. Code Ann., §59-201 (grand jurors) : “The most

experienced, intelligent and upright persons.”

Ga. Code Ann., §59-106 (jurors generally) : “Upright

and intelligent citizens.”

Louisiana None, but compare LSA-R.S. §15-172

(juror qualifications) with LSA-R.S.

§18-31 (voter qualifications).

L.S.A.-R.S. §15-172: “Persons of well-known good

character and standing in the community.”

Mississippi Miss. Code Ann., §1762 None

North Carolina None N.C. General Statutes, §9-1: “Persons . . . of good

moral character.”

South Carolina S. C. Code Ann., §38-52 S.C. Code Ann., §38-52: “Male electors . . . of good

moral character.”

Virginia None None

Arkansas Grand Juror: Ark. Stat. §39-101

Petit Juror: Ark. Stat. §39-206

Ark. Stat. §39-101: “Temperate and good behavior.”

Ark. Stat. §39-206: “ Good character.”

Texas Vernon’s Ann. Tex. Stat., Art. 2133,

“ Qualified to vote” .

Vernon’s Ann. Tex. Stat., Art. 2133: “Good moral

character.”

Tennessee None Tenn. Code Ann., §22-203: “ Integrity, fair character,

sound judgment.”