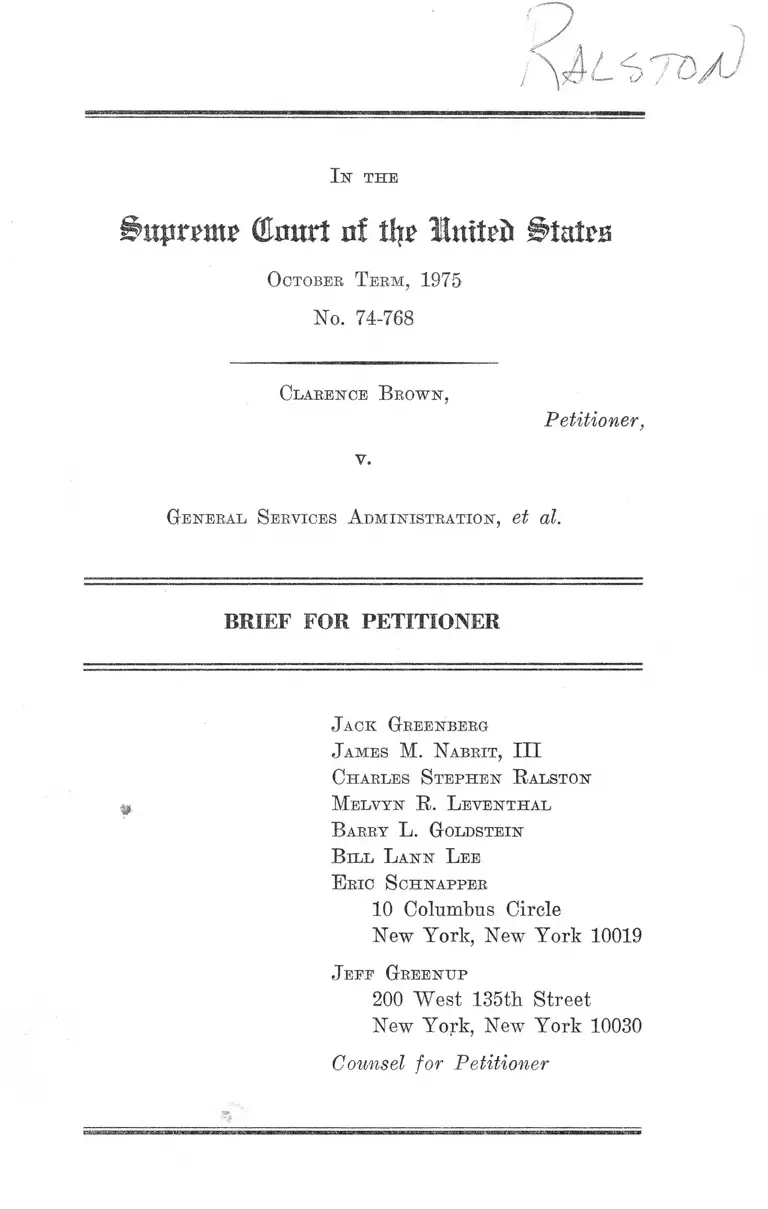

Brown v. General Services Administration Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. General Services Administration Brief for Petitioner, 1975. d74a69b7-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/17bb655d-70f4-4a5e-a7eb-de76ccc50e15/brown-v-general-services-administration-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

(tart n! % United States

O ctober T erm , 1975

No. 74-768

Clarence B ro w n ,

Petitioner,

v.

G eneral S ervices A dm inistration , et al.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

C harles S teph en R alston

M elvyn R . L even th al

B arry L . G oldstein

B il l L a n n L ee

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J eep G reenup

200 West 135th Street

New York, New York 10030

Counsel for Petitioner

TABLE OF COINTENTS

Opinions Below ................ .................. ........... ................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................. 1

Questions Presented .......................................................... 1

Statutory Provisions Involved ............................. 2

Statement of the Case ......................................... ............ 4

Summary of Argum ent...................................................... 7

A rgum ent

I. Jurisdiction Over This Action Is Conferred

By Statutes Adopted Prior To Section 717

of Title V II of The 1964 Civil Rights A c t ....... 11

A. 1. The 1866 Civil Rights Act ................... 14

2. The Mandamus Act ..... 22

3. The Tucker Act ........... 26

4. 28 U.S.C. § 1331 ......................................... 31

5. Administrative Procedure Act ............. 36

B. Application of Section 717 to Discrimina

tion Occurring Before March 24, 1972 ....... 38

C. Section 717 Did Not Repeal Pre-Existing

Remedies for Discrimination in Federal

Employment ......................... 38

PAGE

11

PAGE

II. This Action Should Not Be Dismissed For

Failure To Exhaust Administrative Remedies 44

A. Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies Is

Not a Prerequisite To An Action Under

The 1866 Civil Rights Act, etc..................... 45

1. Independent Remedies ............................ 46

2. Purposes of Exhaustion .......................... 49

3. Other Policy Considerations ................. 56

B. Even If Exhaustion Is Generally Required

In Such Actions, It Should Not Be Re

quired In This Case ................................. 61

C onclusion ........ ...........................................-..................... 67

A ppendix A ................................... laa

A ppen d ix B .......................................................................... 2aa

T able op A uthorities

Cases:

Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136 (1967) ..36, 45

Ableman v. Booth, 21 How. (62 U.S.) 506 (1858) ------- 18

Adams v. Witmer, 271 F.2d 29 (9th Cir. 1959) 37

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 43 U.S.L.W. 4880

(1975) _______________ ________ ___ -............ 25, 49, 50, 55

Alcoa S.S. Co. v. United States, 80 F.Supp. 158 (S.D.

N.Y. 1948) ............. ......... .. ........... ............... —......... . 28

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415, U.S. 36 (1974)

37, 40, 42, 46, 50, 51, 55, 56, 64

Allison v. United States, 451 F.2d 1035 (Ct. Cl. 1971)

29, 40

Ill

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Au

thority, 306 F.Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969) ........... . 14

Arrow Meat Company v. Freeman, 261 F.Supp. 622

(D. Ore. 1966) ........ ...... ........... ........ .... ........ .............. 36

Aycock-Lindsey Corporation v. United States, 171 F.2d

518 (5th Cir. 1948) ...................... ..................... .............. 29

Beale v. Blount, 461 F.2d 1133 (5th Cir. 1972) ..... 24, 25, 30

Beers v. Federal Security Administrator, 172 F.2d 34

(2nd Cir. 1949) ___ ______________________ ___ _____ 28

Bennett v. Gravelle, 4 EPD U7566 (4th Cir. 1971) .... .15, 35

Berk v. Laird, 429 F.2d 302 (2d Cir. 1970) _____ ____ 34

Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, 403

U.S. 388 (1971) ........ ................... ....... .......... ............ ...28,35

Blanc v. United States, 244 F.2d 708 (2d Cir. 1957) .... 31

Board of Trustees of Arkansas A & M College v. Davis,

396 F.2d 730 (8th Cir. 1968) ........................................... 35

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ..... ..17, 23, 28, 34, 35

Boudreau v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting, 437

F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971) ............... ............. ............. ..15, 40

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 416

U.S. 696 (1974) .... ..... ............................................... ..... 38

Brady v. Bristol Meyers, Inc., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir.

1972)............... ........................ ......... .......................... ....... 15, 40

Brooks v. Marcelli, 331 F.Supp. 1350 (E.D. Pa. 1971) .. 42

Brooks v. United States, 337 U.S. 49 (1949) ................ 29

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ............. ........... .............. ........... . 15

Caldwell v. National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044 (5th

Cir. 1971) ......... ........................ ......................... .............. 15

Cappadora v. Celebrezze, 356 F.2d 1 (2d Cir. 1966) .... 36

Carriso v. United States, 106 F.2d 707 (9th Cir. 1939) .. 28

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971)____17, 35

PAGE

IV

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) ........ . 35

Chambers v. United States, 451 F.2d 1045 (Ot. Cl.

1971) ..................................................................................8,29

Christian v. New York Department of Labor, 414 U.S.

614 (1974) ____ 54,65

Citizens Committee for Hudson Valley v. Volpe, 425

F.2d 97 (2d Cir. 1970) ............................ ............... . 36

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S.

402 (1971) ............. .............................. ...................... ..... 36

City of New York v. Ruckelshaus, 358 F.Supp. 669

(D.D.C. 1973) ....... ............................ ........................ ..... 24

Clackamas County, Oregon v. Mackay, 219 F.2d 479

(D.C. Cir. 1954) ........... 26

Clay v. United States, 210 F.2d 686 (D.C. Cir. 1954) .. 31

Oompagnie General Translantique v. United States, 21

F.2d 465 (S.D.N.Y. 1927) ................................. .......... 28, 29

Congress of Racial Equality v. Commissioner, 270

F.Supp. 537 (D. Md. 1967) ............................................ 12

Copeland v. Mead Corp., 51 F.R.D. 266 (N.D. Ga. 1970) 15

Cortwright v. Resor, 325 F.Supp. 797 (E.D.N.Y. 1971) 32

Damico v. California, 389 U.S. 416 (1967) ..... 46

Davis v. Romney, 355 F.Supp. 29 (E.D. Pa. 1973) ____ 36

Davis v. Washington, 352 F.Supp. 187 (D.D.C. 1972) .... 23

District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973)

7, 8,16,17

Dugan v. Rank, 372 U.S. 609 (1963) ............................... 34

Estrada v. Alliens, 296 F.3d 690 (5th Cir. 1969) ..... ..... 37

Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) .............. ...... .... .33, 34

Farmer v. Philadelphia Elec. Co., 329 F.2d 3 (3d Cir.

1964)

p a g e

3 2

V

Faruki v. Rogers, 349 F.Supp. 723 (D.D.O. 1972) ....... 23

Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 211 U.S. 249

(1908) .................................................... .......... ............ . 24

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 595 (1866) ...... ............ 23

Glover v. Daniel, 434 F.2d 617 (5th Cir. 1970) ........... ........ 14

Glover v. St. Louis, etc., R.R., 393 U.S. 324 (1969) ......50, 52

Gnotta v. United States, 415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir.

1969) ........................................................... .................... 12,29

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 461 U.S. 424 (1971) ........... 49

PAGE

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975) ..... 49, 59, 66

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp,, 350 F.Supp. 529

(S.D. Tex. 1972) .............................................................. 45

Hackett v. McGuire Brothers Inc., 445 F.2d 442 (3d

Cir. 1971) .......................................................................... 15

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) ............... .............. 49

Harris v. Kaine, 352 F.Supp. 769 (S.D.N.Y. 1972) .... . 36

Henderson v. Defense Contract Administration Ser

vices, 370 F.Supp. 180 (S.D.N.Y. 1973) ........................6,23

Hill v. United States, 40 Fed. 441 (C.C. Mass. 1889).... *27

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) ............ ....... ..... .....16,17

Huston v. General Motors Corp., 477 F.2d 1003 (8th

Cir. 1973) .......................................................................... 6

Indian Trading Co. v. United States, 350 U.S. 61 (1955) 21

Jackson v. United States, 129 F.Supp. 537 (D. Utah

1955) .................................................................................. 30

James v. Ogilvie, 310 F.Supp. 661 (N.D. 111. 1970) ...... 15

Jarrett v. Resor, 426 F.2d 213 (9th Cir. 1970) ............... 22

Jenkins v. General Motors Corp., 475 F.2d 764 (5th Cir

1973) .................................................................................. 45

Johnson v. Cain, 5EPD j[8509 (D.Del. 1973) ... ...14,35

VI

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 349 F.Supp.

3 (S.D. Tex. 1972) ............................ 15

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 44 L.Ed. 2d 295

(1975) ................ 9,14,40,46,

47, 49, 63

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer C'o., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) ....... 17,

18,42

Jones v. United States, 127 F.Supp. 31 (E.D.N.C.

1954) .................................................................................. 27

Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306

U.S. 381 (1938) ............................... 22

Kletschka v. Driver, 411 F.2d 436 (2d Cir. 1969) ......... 37

Lancashire Shipping Co. v. United States, 4 F.Supp.

544 (S.D.N.Y. 1933) ...................................................... 28

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce Corp., 337

U.S. 643 (1949) ....... ............. ........................................._. 34

Law v. United States, 18 F.Supp. 42 (D.Mass. 1937) .... 28

Lazard v. Boeing Co., 322 F.Supp. 343 (D. La. 1971) .... 15

Leonhard v. Mitchell, 473 F.2d 709 (2d Cir. 1973) ..... 23

Lloyds’ London v. Blair, 262 F,2d 211 (10th Car. 1958) 27

Lombard Corporation v. Resoc, 321 F.Supp. 687 (D.

D.C. 1970) ...................................................... 37

London v. Florida Department of Health, 313 F.Supp.

591 (N.D. Fla. 1970) .......................................... ......... 44 ̂35

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 352 F.Supp. 135 (E.D. Mich.

1972) ...................................................................... 40

Long v. Ford Motor Company, 496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir.

1974) ...................................................................

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d

979 (D.C. Cir. 1973)

page

4 0

vii

Malone v. Baldwin, 369 IT.S. 643 (1962) ................. ......... 34

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803) ....8,22,

26, 32

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1972) ....... ....... ................... ..................... ........... 37,45

McGee v. United States, 402 U.S. 479 (1971) ............... 45

McIIoney v. Callaway, No. 74-0-1729, E.D.N.Y.......... 57

McKart v. United States, 395 U.S. 185 (1969).......45, 49, 50,

58, 61

McLaughlin v. Callaway, No. 74-1237, S.D. Ala............. 57

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963) .... 46

McQueary v. Laird, 449 F.2d 608 (10th Cir. 1971) ....... 26

Miguel v. McCarl, 291 U.S. 442 (1934) .......................... 24

Mills v. Board of Education of Ann Arundel, 30

F.Snpp. 245 (D. Md. 1938) ................................. ...... 14

Minnesota v. United States, 305 U.S. 382 (1939) ....... 22

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ....................... 46

Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1974).........14,35

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) .... ...9,17, 23, 41, 44

Murphy v. Colonial Fed. Savings and Loan, 388 F.2d

609 (2d Cir. 1967) .......................................................... 32

N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 340 F.Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972) 35

National Helium Corporation v. Morton, 326 F.Supp.

151 (D. Kan. 1971) .......... .......... .............. ............. .... 37

National Helium Corporation v. Morton, 455 F.2d 650

(10th Cir. 1971) ......... .................................................... 37

Northeast Residents Association v, Department of

Housing and Urban Development, 325 F.Supp. 65

(E.D. Wis. 1971) ........................ ............... .......... ........ 36

Norwalk Core v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 .

. F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968) ....... ....................................... 37

PAGE

Vlll

Pacific Telephone, etc. Co. v. Keykendall, 265 U.S. 196

(1924) .................................. ............................................. 65

Palmer v. Rogers, 6 EPD «[J8822 (D. D.C. 1973) .........31, 32

Parisi v. Davidson, 405 U.S. 34 (1972) ...... .................. 65

Penn v. Schlesinger, 490 F.2d 700 (5th Cir. 1973)

24, 25, 47, 55

Penn v. Schlesinger, 497 F.2d 970 (5th Cir. 1974).......25, 55

Penn v. Schlesinger, No. 74-476 ............................ -........ 65

Perry v. United States, 308 F.Supp. 245 (D. Colo. 1970) 27

Pettit v. United States, 488 F.2d 1026 (Ct. Cl. 1973)..... 30

Philadelphia Co. v. Stimson, 223 U.S. 605 (1912) ....... 34

Place v. Weinberger, No. 74-116 ...................................... 38

Prentis v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, 211 U.S. 210

(1908) ................................ ......... -................................. . 65

Rambo v. United States, 145 F.2d 670 (5th Cir. 1944).... 31

Rayonier v. United States, 352 U.S. 315 (1957) ...... 22

Renegotiation Board v. Bannercraft Co., 415 U.S. 1

(1974) .................................................. ............ ........ - ...... 51

Rice v. Chrysler Corp., 327 F.Snpp. 80 (E.D. Mich.

1971) .... ......... - ................................................................. 15

Road Review League v. Boyd, 270 F.Supp. 650

(S.D.N.Y. 1967) ............. 36

Roberts v. United States ex rel. Valentine, 176 U.S. 221

(1900) ...................................................................... 24

Ross Packing Co. v. United States, 42 F.Supp. 932

(E.D. Wash. 1942) ......... 28,29

Rural Electrification Administration v. Northern States

Power Co., 373 F.2d 686 (8th Cir. 1967) ................. 22

Rusk v. Cort, 369 U.S. 367 (1962) ............. ....................... 36

Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61 (1974) ............................. 24

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir.

1970) .................................................... 15,40

p a g e

IX

PAGE

Scanwell Laboratories Inc. v. Shatter, 424 F.2d 859

(D.C. Cir. 1970) ............................. -.............................. 37

Schener v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974) ...... ................ 35

Schicker v. United States, 346 F.Supp. 417 (D. Conn.

1972) ................................. -......... -................................ 36

Schroede Nnrsing Care, Inc. v. Mutual of Omaha Inc.

Co., 311 F.Supp. 405 (E.D. Wis. 1970) ....... ................. 37

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945) .... ............ 17

Service v. Dulles, 354 U.S. 363 (1957) ....... ..................... 24

Settle v. E.E.O.C., 345 F.Supp. 405 (S.D. Tex. 1972).... 35

Sinclair Nav. Co. v. United States, 32 F.2d 90 (5th Cir.

1929) .................................................. - ............................. 28

Smiley v. City of Montgomery, 350 F.Supp. 451 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) .............. ..................... - ................................. 14

Smith v. United States, 458 F.2d 1231 (9th Cir. 1972) 28

Somma v. United States, 283 F.2d 149 (3rd Cir. 1960)..65, 66

Spanish Royal Mail Line Agency, Inc. v. United States,

45 F.2d 404 (S.D.N.Y. 1930) ....... ...............................~ 28

Sperling v. U.S., 9 EPD fL0,100 (3d Cir. 1975) .... . 64

Spillway Marina, Inc. v. U.S., 445 F,2d 876 (10th Cir.

1971) ........... .. .................... ------------- 27

Strain v. Philpott, 4 EPD flf[7885 (M.D. Ala. 1971).....14, 35

Suel v. Addington, 465 F.2d 889 (9th Cir. 1972).........14, 35

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969).... 42

Sultzbach Clothing Co. v. United States, 10 F.2d 363

W.D. N.Y. 1925) .............................. ......... ......... ......... . 28

Sutcliffe Storage & Warehouse Co. v. United States,

162 F.2d 849 (1st Cir. 1947) ........................................ 27

Swain v. Callaway, 5th Cir. No. 75-2002 .................. ...... 57

Thorn v. Richardson, 4 EPD H7630 (W.D. Wash. 1971) 24

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association,

410 U.S. 431 (1973) ............................................ 8,16,17, 42

X

Toilet Goods Association v. Gardner, 360 F.2d 677

(2d Cir. 1966) .................................................................. 34

Union Trust Co. v. United States, 113 F.Snpp. 80 (D.

D.C. 1953) ...................... 27

United States ex rel. Parish, v. MacYeagh, 214 U.S. 124

(1909) ..... 24

United States v. Emery, Bird, Thayer R.R. Co., 237

U.S. 28 (1915) ....................................................... 29

United States v. Hellard, 322 U.S. 363 (1944) ............. 22

United States v. Hvoslef, 237 U.S. 1 (1915) ....... 28

United States v. Johnson, 153 F.2d 846 (9th Cir. 1946) 27

United States v. Jones, 109 U.S. 513 (1883) ................... 22

United States v. Shaw, 309 U.S. 495 (1939) ..... 22

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 340 U.S. 543 (1950)..22, 27

Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F.2d 807 (2d Cir. 1967) ..... 34

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476 (7th

Cir. 1970) ....... ........ ........................ .................... .......... 15, 40

Watkins v. Washington, 3 EPD 1J8291 (D.D.C. 1971) .. 35

Weinberger v. Salfi, 43 U.S.L.W. 4985 (1975) .......45, 49, 51

Weinberger v. Weisenfeld, 43 U.S.L.W. 4393 (1975) ....45, 49

West v. Board of Education of Prince George’s County,

165 F.Supp. 382 (D.Md. 1958) ...................... ............ . 14

Work v. United States ex rel. Lynn, 266 U.S. 161 (1924) 24

Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph, 438

F.2d 757 (3d Cir. 1971) .................................................. 40

Young v. International Tel. & Tel. Co., 438 F.2d 757

(3d Cir. 1971) .......................................................... . 15

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579

(1952) ........................................................... ........ ........... 34

PAGE

Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967) 47

X I

Constitutional Provisions: page

U.S. Constitution, Article I, section 9 .................-........ 28

IJ.8 . Constitution, Fourth Amendment ........... ............. 28

TJ.S. Constitution, Fifth Amendment ................... 13, 21, 23,

28, 36, 43

U.S. Constitution, Eleventh Amendment ..................... 33

Statutes:

5 U.S.C. §702 ....................................................................13, 36

5 U.S.C. §704 ...................................................................... 45

5 U.S.C. §706 ....... ............................................................... 36

25 U.S.C. §461 ...... ..... - ....... -......... ...... - ................ -..... - 44

5 U.S.C. §7151 .................................................12,13, 23, 43, 54

28 U.S.C. §1254 (1) .................................................. 1

28 U.S.C. §1331 .......... ..................................3, 8,13, 27, 31, 32,

35, 37, 43, 53

28 U.S.C. §1343 ................................................ -3, 8,19, 20, 21

28 U.S.C. §1346 ....................................................4, 7, 8,13, 26,

27, 28, 29, 30

28 U.S. §1361 ............. ................. - ....................... 4, 7, 8,13, 22,

26, 30, 31

28 U.S.C. §1491 ........... ............... .................................8, 29, 40

42 U.S.C. §1971 (c) ............................................................. . 42

42 U.S.C. §1981 ...................................—.3, 7, 8,13-17, 20, 21,

23,40, 42-48, 50, 58, 61

42- U.S.C. §1982 .................................................. 7, 8,16,17, 42

Xll

PAGE

42 U.S.C. §1983 .................................................................. 15, 42

42 U.S.C. §2000a........................................................ ......... 42

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5; Section 706 of Title V I I ............ 39,43

42 U.S.C. §2Q00e-6; Section 707 of Title V II _______ 39

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16; Section 717 of Title V I I .......1, 2, 6, 7,

9,11,13, 38-44, 47, 54,

58, 59, 63, 64, 66

42 U.S.C. §3612 .... .............................. ............................... 42

Administrative Procedure Act ...................7, 8,13, 36, 37, 45

Civil Rights Act of 1866 ............ ........................ 7, 9,13-20, 23,

37, 45, 53, 62

Civil Rights Act of 1870 ................. ...............................15, 20

Civil Rights Act of 1871 ...................... 20

Civil Rights Act of 1957 ............... 42

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ........................... 2

Fugitive Slave A c t ..... ........................................................ 18

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 ....................... 36

Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 .... .................. ........... 9, 44

Mandamus Act ....... ....................................... 7, 8,13, 22, 37, 46

National Labor Relations A c t .......................................... 28

Social Security Act ...... .............................. ......... ............. 28

Transportation Act — ............................... ...................... 28

Tucker Act .............7, 8,13,14, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 37, 43, 46, 53

14 Stat. 27 ....................................................... ...... 15,16,19, 20

14 Stat. 28 ............................. .................. .......... ...... ......... 19

X l l l

14 Stat. 29 ........................................................................... 19

16 Stat. 140 ..... .................................. -................................. 15

76 Stat. 744 .... ....................................................... ........... 30, 31

78 Stat. 699 .................................................... ............... ..... 30

Anno. Code of Cal., §1422 ................................. ................ 48

Code of Ala., Title 7, §5526 .................... ............. ............. 48

Code of S.C., §10-146 ...... ........ ........................ ............. . 48

New York Civil Practice Law and Rules, §214............... 48

Tenn. Code Anno. §28-304 ........... ................................ . 48

Vernon’s Anno. Texas Revised Civil Statutes, Art. 5526 48

Regulations:

5 C.F.R. part 351 ...... ...... ........ ......... ................ ....... ..... 57

5 C.F.R. part 532 ..... .......... ..... ........................................ 57

5 C.F.R. part 713 ......... ....... ....... 12,13, 24, 29, 43, 45, 46, 57

5 C.F.R. part 771 ....... ..... ............................... ............... . 57

5 C.F.R. §300.103 ........................................ ......... ............. 57

5 C.F.R. §713.201 .............................. ........... ............... ..... 24

5 C.F.R. §713.203 ............. ..... ........... ................................. 54

5 C.F.R. §713.213 ............................................ ............. . 48

5 C.F.R. §713.214 ......................... ...... ......... ............ ........ 53

5 C.F.R. §713.216 ........... ............ ............ ........... ............... 60

5 C.F.R. §713.217 ........................................................ ....... 60

5 C.F.R. §713.219 ................................................................ 57

5 C.F.R. §713.220 ......... .................................................... 47, 62

PAGE

5 C.F.R. §713.251 ............................... ............... ................. 57

5 C.F.R. §713.261 .... ........ ........ ....... ....... .......................... 57

5 C.F.R. §713.271 ............ ..............................................8,25,53

5 C.F.R. §772.306 ................................................................ 57

Executive Orders:

Executive Order 9980 ........................................ ........... ... 24

Executive Order 10590 ........................... ..... ..... ........... . 24

Executive Order 10925 ................................................... 24

Executive Order 11246 ........ .......... ..................... ........ .... 24

Executive Order 11478 .................................. 13, 24, 29, 41, 43

Executive Order 11590 .................. 24

Legislative Materials:

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess......23, 38, 49, 52, 57

S. Rep. 1390, 88th. Cong., 1st Sess....................... ........... 30, 31

H. Rep. No. 92-238, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess...... .......... 49, 51, 63

H. Rep. 1604, 88th Cong., 2d Sess................................... 30

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Senate Com

mittee on Labor & Public Welfare, 92 Cong., 1st Sess.

(1971) ........................... 12,13,42

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Senate Judi

ciary Committee, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) .........12,13

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Labor of the

House Committee on Education and Labor, 92 Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971) ........ .............. ........ ................................ 12

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. ................................... 21

x i v

PAGE

XV

Gong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess........... ............ ............ 20

108 Cong. Rec................................... ........... .......... ............. 26

110 Cong. Rec. ................................ ...................................31, 42

117 Cong. Rec...................................................... ....... ........ 39

118 Cong. Rec. ........................ ...................... ......... 38, 39, 42,43

PAGE

Other Authorities:

G. Bentley, History of the Freedmen’s Bureau (1955).. 18

M. King, Lyman Trumbull (1965) ............. .... ........... . 18

Moore’s Federal Practice .................................................. 27

K. Stamp, The Era of Reconstruction (1965) ........... . 18

Schlesinger and Israel, The State of the Union Mes

sages of the President (1966) .......... ......... ............... 21

ten Broek, Equal Under Law (1951) .................... 18,20

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Federal Civil

Rights Enforcement Effort 1974 .......... ........ .52, 53, 54, 61

Byse and Fiucca, “ Section 1361 of the Mandamus and

Venue Act of 1962” , 81 Harv. L. Rev. 308 (1967)...... 26

Graham, “The Conspiracy Theory” of the Fourteenth

Amendment” , 47 Yale L.J. 371 (1938) ..................... 20

Graham, “ The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the

Fourteenth Amendment” , 1950 Wise. L. Rev. 479...... . 20

Board of Appeals and Review. Work Load Statistics,

Fiscal Years 1972, 1973, 1974 64

I n t h e

g>uprrme CUmtrt nf itp? Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1975

No. 74-768

Clarence B ro w n ,

v.

Petitioner,

G eneral S ervices A dm inistration , et al.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 507

F.2d 1300, and is set forth in the Appendix to the Petition,

pp. 2a-18a. The opinion order of the District Court, which

is not reported, is set forth in the Appendix to the Peti

tion, p. la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

November 21, 1974. The Petition was filed on December

20, 1974 and granted on May 27, 1975. Jurisdiction of the

Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Is jurisdiction over this action conferred by statutes

enacted prior to the adoption in 1972 of section 717 of

Title VII?

2

2. Was this action properly dismissed for failure to ex

haust administrative remedies 1

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 717(a) of Title Y II of the 1964 Civil Bights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(a), provides:

All personnel actions affecting employees or ap

plicants for employment (except with regard to aliens

employed outside the limits of the United States) in

military departments as defined in section 102 of title

5, United States Code, in executive agencies (other

than the General Accounting Office) as defined in sec

tion 105 of title 5, United States Code (including em

ployees and applicants for employment who are paid

from nonappropriated funds) in the United States

Postal Service and the Postal Rate Commission, in

those units of the Government of the District of Colum

bia having positions in the competitive service, and

in those units of the legislative and judicial branches

of the Federal Government having positions in the

competitive service, and in the Library of Congress

shall be made free from any discrimination based on

race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Section 717(c) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §20G0e-16(c), provides:

Within thirty days of receipt of notice of final action

taken by a department, agency, or unit referred to in

subsection 717(a), or by the Civil Service Commission

upon an appeal from a decision or order of such de

partment, agency, or unit on a complaint of discrimi

nation based on race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin, brought pursuant to subsection (a) of this

section, Executive Order 11478 or any succeeding Ex-

3

ecutive orders, or after one hundred and eighty days

from the filing of the initial charge with the depart

ment, agency, or unit or with the Civil Service Com

mission on appeal from a decision or order of such

department, agency, or unit until such time as final

action may be taken by a department, agency, or unit,

an employee or applicant for employment, if aggrieved

by the final disposition of his complaint, or by the

failure to take final action on his complaint, may file a

civil action as provided in section 706, in which civil

action the head of the department, agency, or unit, as

appropriate, shall be the defendant.

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C., provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal bene

fit of all laws proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

Section 1331(a), 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of all civil actions wherein the matter in controversy

exceeds the sum or value of $10,000, exclusive of in

terest and costs, and arises under the Constitution,

laws or treaties of the United States.

Section 1343(4), 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of any civil action authorized by law to be commenced

by any person:

* # # # #

4

(4) To recover damages or to secure equitable or

other relief under any Act of Congress providing for

the protection of civil rights, including the right to

vote.

Section 1346, 28 U.S.C., provides in pertinent part:

(a) The district courts shall have original jurisdic

tion, concurrent with the Court of Claims, o f :

# * # # #

(2) Any other civil action or claim against the

United States, not exceeding $10,000 in

amount, founded upon the Constitution or any

Act of Congress, or any regulation of an ex

ecutive department, or upon any express or

implied contract with the United States, or

for liquidated or unliquidated damages in

cases not sounding in tort.

Section 1361, 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of any action in the nature of mandamus to compel an

officer or employee of the United States of any agency

thereof to perform a duty owed to the plaintiff.

Statement o f the Case

Petitioner is black and has for eighteen years been an

employee of the General Services Administration, herein

after “ GSA” .1 (A. 4a) He is a GS-7 but has been cer-

1 Subsequent to the filing of the Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

petitioner was transferred to another government agency. That

lateral transfer has no effect on his claim for back pay or injunc

tive relief. Petitioner is still a GS-7 and still wants the specific

GS-9 position in the General Services Administration for which

he applied in 1971.

5

tilled eligible and rated “ highly qualified” for a GS-9 posi

tion. He has for the past eight years been repeatedly de

nied that GS-9 promotion. (A. 15a-17a)

October 19, 1970, the names of petitioner and two whites

were submitted to petitioner’s white supervisor for the

filling of a GS-9, Communications Specialist, vacancy; all

of the candidates wrere rated “highly qualified;” a white

obtained the promotion. Immediately thereafter, petitioner

contacted his Equal Employment Opportunity Counsellor

at GSA and was advised to withhold a formal complaint

of discrimination because two new GS-9 vacancies were

imminent; petitioner complied with the EEO Counsellor’s

request and terminated proceedings. (A. 36a)

June 15, 1971, the names of petitioner and two whites

-were submitted to petitioner’s supervisor for the filling of

a GS-9 vacancy; on this occasion only petitioner and one

of the white candidates were rated “highly qualified;” a

white candidate was again selected. On July 15, 1971, peti

tioner filed his Complaint of Discrimination against the

Director of the Transportation and Communications Ser

vice and the Chief of the Commissions Division, GSA.

Petitioner’s complaint alleged inter alia, that he had been

seeking a promotion since 1967 to a GS-9 position and that

in every instance he had been rejected because of his race.

(A. 5a-15a) The agency investigation revealed that peti

tioner had been repeatedly passed over for promotion in

favor of white employees. In addition, subsequently pub

lished statistics reveal that, while blacks are employed at

GSA in significant numbers in grades GS-7 and lower, they

are clearly under-represented in all grades GS-8 and above

(Appendix A, infra, p. laa). October 19,1972, GSA notified

petitioner that on the basis of the investigative file it pro

posed to find that it had not discriminated against him and

advised him of his right to a hearing. (A. 30a)

6

December 13, 1972, a bearing was held on petitioner’s

complaint. February 9, 1973, the Hearing Examiner found,

on the basis of petitioner’s supervisors’ testimony, that the

whites selected for the positions in contest were more

“ cooperative” than the petitioner and, accordingly, that

petitioner was not passed over because of his race. (A.

40a)

March 23, 1973, twenty months after petitioner filed his

administrative complaint, GSA issued its final agency deci

sion concluding* that it had not discriminated against peti

tioner on the basis of race.2 (A. 43a)

Petitioner was notified of the agency decision on March

26, 1973. (A. 45a) The letter of notification advised him

that he could within 30 days commence a civil action in the

United States District Court, or within 15 days file an

appeal to the Appeals Review Board of the Civil

Service Commission. On the basis of this letter petitioner

decided to file suit. Because petitioner had great difficulty

locating an attorney who would represent him,, he did not

succeed in filing his complaint until May 7, 1973, 12 days

after the deadline for filing an action under section 717.3 * * * * 8

2 On August 10, 1973, the government moved to dismiss this

action in the district court on the ground, inter alia, that peti

tioner had not commenced his action within the 30 days required

under section 717. On July 27 and September 24, 1973 the same

United States Attorney filed memoranda in the same district

court, in Henderson v. Defense Contract Administration Services,

370 P.Supp. 180 (S.D. N.Y. 1973), arguing that section 717 did

not apply to employees such as petitioner who were the victims

of discrimination prior to March 24, 1972.

8 Within a week of receiving the letter of March 23, petitioner

presented himself and the letter to the clerk of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York, where the

pro se clerk advised him to retain a private attorney. Compare,

Huston v. General Motors Corp., 477 F.2d 1003 (8th Cir. 1973).

Prior to obtaining the services of counsel, petitioner unsuccess

fully sought assistance from three other attorneys and several

civil rights organizations.

7

However, petitioner asserted federal jurisdiction under

several statutes other than §717.

On September 27, 1973, the District Court for the South

ern District of New York dismissed the action for lack of

jurisdiction (Petition, p. la ). On November 21, 1974, the

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed that dis

missal (Petition, pp. 2a-18a). The Second Circuit con

cluded: (1) that section 717 had, by implication, repealed

pro tanto the Tucker Act, the Mandamus Act, the 1866

Civil Eights Act, the Administrative Procedure Act, and

the other statutes which petitioner asserted created fed

eral jurisdiction; (2) that section 717 applied to discrimina

tion occurring prior to its effective date, March 24, 1972,

and that the implied repeal was accordingly retrospective;

and (3) that in any event, petitioner could not sue because

he had not filed an appeal from the final agency decision

to the Appeals Review Board of Civil Service Commission,

and thus had not completely exhausted his administrative

remedies.

Summary of Argument

I. A. Prior to the adoption, in 1972, of section 717 of

Title VII, which gave federal employees the same right

to sue under Title V II enjoyed by private employees, fed

eral jurisdiction to remedy federal employment discrimina

tion already existed under several other statutes.

1. The 1866 Civil Eights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, prohibits

all forms of employment discrimination, including dis

crimination by the federal government. This Court has

already held that § 1982, which also derives from the 1866

Act, applies to the federal government, District of Colum

8

bia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973), and that § 1981 and

§ 1982 should be similarly construed. Tillman v. Wheaton-

Haven Recreation Association, 410 U.S. 431 (1973). Carter

and Tillman compel the conclusion that § 1981 applies to

the federal government. Section 1343(4), 28 U.S.O., con

fers jurisdiction to enforce § 1981.

2. The Mandamus Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1361, authorizes

the district courts to issue writs of mandamus to enforce

the prohibition against federal employment discrimination

contained in the Fifth Amendment, several statutes and

executive orders, and the applicable regulations. Since

federal officials have no discretion to discriminate against

petitioner on the basis of race, their duty to act in a non-

discriminatory manner is ministerial. Because discrimina

tion is unlawful, the responsible officials are not protected

by sovereign immunity. Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137

(1803). Although mandamus is not usually available to

compel the payment of money, it is when there is ministerial

duty to make a payment. The applicable regulations create

such an absolute duty to make an award of back pay in

any case of federal employment discrimination. 5 C.F.R.

§ 713.271(b).

3. The Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1346, confers jurisdic

tion on the district courts over actions against the United

States founded upon the Constitution or any law or regula

tion. Section 1346 was amended in 1964 for the express

purpose of permitting federal employees to sue for back

pay. The similar language of 28 U.S.C. § 1491 ha.s been

construed by the Court of Claims to establish jurisdiction

over federal employment discrimination actions. Chambers

v. United States, 451 F.2d 1045 (Ct. Cl. 1971).

4. Jurisdiction over this action is also conferred by 28

U.S.C. § 1331 and the Administrative Procedure Act.

9

B. Section 717 did not repeal the remedies for federal

employment discrimination which existed before 1972.

In construing section 717, the Court should look to the

meaning and construction of Title V II as applied to private

employees, since section 717 was adopted to give federal

employees the same rights already enjoyed by private

workers. This Court has already held that Title V II did not

repeal the pre-existing remedies of private employees.

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 44 L.Ed. 2d 295

(1975).

Section 717 does not expressly repeal the 1866 Civil

Rights Act or any other remedy. Repeals by implication

are not favored. Congress expressly rejected proposals to

make Title VII the exclusive remedy for employment dis

crimination. In Morton v. Mancari, 417 TJ.S. 535 (1974), this

Court held that the siibstantive provisions of section 717 did

not repeal the apparently inconsistent preference for Indian

employees in the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. It

follows, a fortiori, that section 717 did not repeal the exist

ing complimentary remedies enforcing the same substan

tive prohibition against racial discrimination.

II. A. Exhaustion of administrative remedies should

not be required of federal employees who bring employ

ment discrimination actions under statutes other than Title

VII. Exhaustion is not required of state or private em

ployees who bring employment discrimination cases under

the 1866 Civil Rights Act. Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 44 L.Ed. 2d 295 (1975). Federal employees should

not be treated differently. The administrative procedure

established by the Civil Service Commission is merely one

of several independent remedies among which employees

may choose.

The traditional factors which militate in favor of an

exhaustion requirement are not present in a federal em

10

ployment discrimination case. Congress correctly con

cluded in 1972 that neither the Civil Service Commission

nor the agencies have any expertise in employment dis

crimination matters. Since the finding of discrimination is

mandatory on the establishment of certain facts, this is not

an area where the agencies have any discretion to exercise.

In July, 1975, the Civil Eights Commission concluded, as

had Congress three years earlier, that the administrative

procedure is so biased against aggrieved employees as to

make resort thereto essentially futile. In Fiscal Tear 1973,

of 26,627 informal complaints and 2,743 formal complaints

by federal employees, only 22 resulted in back pay or retro

active promotions.

I f exhaustion were generally required, the federal courts

would be obligated to determine (a) whether each partic

ular complaint would have been futile in view of the many

defects in the administrative procedure, and (b) whether

an employee had chosen the correct administrative pro

cedure among the 9 different procedures established by

regulation. The judicial time consumed in deciding these

questions would be better used resolving the merits of the

discrimination claims. The delays and effort required to

vigorously prosecute an administrative complaint place a

significant burden on employees, and should not be imposed

where there is little chance of success. Because of the

great importance of eradicating discrimination, the most

efficacious remedy should be the first invoked, and the choice

of remedy should be made by the aggrieved employee, not

by the courts.

B. Even if exhaustion is generally required in federal

employment discrimination cases, further exhaustion efforts

should not be required in this case. Although Civil Ser

vice .Commission regulations require an agency to resolve

a discrimination case within 180 days, the defendant agency

11

did not decide the instant case for 617 days. It would be

unreasonable to impose on petitioner the further delay of

an administrative appeal. Congress,, in adopting section

717, made appeals to the Appeals Review Board optional

because it concluded such appeals were generally futile.

This Court should not require plaintiffs suing under stat

utes other than Title V II to meet a more stringent exhaus

tion requirement than Congress thought reasonable.

Should the Court conclude that petitioner’s suit was pre

mature, the appropriate disposition of this action is not

dismissal with prejudice but merely an appropriate stay

of judicial proceedings while exhaustion is completed. This

is the usual practice in cases of inadequate exhaustion.

I f the government objects to this action because it claims

petitioner’s case should be considered by the Appeals Re

view Board, it must now afford petitioner an opportunity to

appeal to the Board.

ARGUMENT

I.

Jurisdiction Over This Action Is Conferred By Stat

utes Adopted Prior To Section 717 o f Title VII o f The

1964 Civil Rights Act.

In 1971-72, when Congress was considering adopting sec

tion 717 or other legislation to assure federal employees

a right to judicial determination of their claims of dis

crimination, both the Civil Service Commission and the

Department of Justice advised Congress that federal em

ployees already had that right. Irving Kator, the Deputy

Executive Director of the Commission, testified:

“ There is also little question in our mind that a

Federal employee who believes he has been discrim-

12

mated against may take his case to the Federal

courts . . . .” 4

The Commission submitted a written statement insisting:

“We believe Federal Employees now have the oppor

tunity for court review" of allegations of discrimina

tion, and believe they should have such a right.” 5

The Commission argued that the then leading cases deny

ing federal employees such a right to sue, Gnotta v. United

States, 415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.8 .

934 (1970), and Congress of Racial Equality v. Commis

sioner, 270 F.Supp. 537 (D.Md. 1967), were incorrectly de

cided.6 Assistant Attorney General Ruckelshaus assured

a Senate subcommittee that the courts could remedy any

unconstitutional or unlawful federal action.7 Although

4 Hearings Before Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on

Labor & Public Welfare, 92 Cong., 1st Sess. 301 (1971) p. 296.

5 I d p. 310.

6 The Commission reasoned: “As it appears that the attention

of the court in the CORE case was not directed to the statute (5

U.S.C. § 7151) . . . and that case involved no constitutional issue,

we do not regard it as dispositive of the matter under considera

tion. To the same effect see Gnotta v. United States, 415 F.2d 1271

(8th Cir. 1969), in which one court found no jurisdiction to re

view an alleged failure of promotion due to discrimination but did

not discuss the statutory or constitutional issues that might be in

volved in such an action. We are of the opinion that an individual

who has exhausted the discrimination complaint procedure pro

vided in Part 713 of the Civil Service regulations (5 CFR part

713) may obtain judicial review of the alleged discriminatory

action . . .” Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Labor of the

House Committee on Education and Labor, 92 Cong., 1st Sess.

386 (1971).

7 Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Com

mittee, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970), pp. 69, 74, 256-257:

’ “ [ T ] o some extent injunctive remedies are already avail

able. The constitutionality of any program can be challenged.

13

the Civil Service Commission insisted that section 717

“would add nothing” 8 to the rights federal employees

already enjoyed under earlier statutes, Congress adopted

section 717 in view of its concern that the courts might

not construe the existing statutes to provide such a remedy.

Petitioner asserts that jurisdiction over his claims of

federal employment discrimination is conferred by stat

utes adopted prior to section 717: the 1866 Civil Rights

Act,9 the Mandamus Act,10 the Tucker Act,11 the Adminis

trative Procedure Act12 and 28 U.S.C. §1331, and that the

defendants’ alleged refusal to promote him on account of

race violates the Fifth Amendment, the 1866 Civil Rights

Act, 5 U.S.C. §7151,13 14 Executive Order 11478“ and 5 C.F.R.

part 713.15 Petitioner urges that sovereign immunity pre

The authority within the program of an official to act can be

challenged.”

“ [T]here is no doubt that a court today may look into un

authorized or unconstitutional agency action . . . ”

8 Hearings Before Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Com

mittee on Labor & Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 301 (1971).

9 42 U.S.C. §1981.

10 28 U.S.C. §1361.

“ 28 U.S.C. §1346.

12 5 U.S.C. §§702-06.

13 5 U.S.C. §7151 provides:

It is the policy of the United States to insure equal employ

ment opportunities for employees without discrimination be

cause of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. The

President shall use his existing authority to carry out this

policy.

14 See n.39, infra, p. 23.

16 See n.40, infra, p. 24.

14

sents no obstacle to injunctive relief requiring an end to

discrimination, to injunctive relief to enforce the ministerial

duty to award back pay in cases of discrimination, or to

monetary relief against tbe defendant individuals. A waiver

of sovereign immunity is necessary for awards of punitive

and compensatory damages, and that waiver is found in

the Tucker Act and the 1866 Civil Eights Act.

A. 1. The 1866 Civil Rights Act

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C., which derives from Section 1

of the 1866 Civil Eights Act, provides that “All persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the

same right in every state and Territory to make and en

force contracts. . . .” (Emphasis added). This includes

employment contracts and thus entails a ban on racial

discrimination in hiring and promotion. Johnson v. Rail

way Express Agency, 44 L.Ed. 2d 295, 301 (1975). Sec

tion 1981 has been uniformly held to bar discrimination

in employment by state16 and local17 governments, by pri-

16 See e.g. Johnson v. Cain, 5 EPD 8509 (D. Del. 1973); Suel

v. Addington, 465 F.2d 889 (9th Cir. 1972); Strain v. Philpott,

4 EPD 7885, 7562, 7521 (M.D. Ala. 1971); Morrow v. Cnsler,

491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir. 1974) (en banc) ; London v. Florida De

partment of Health, 313 F.Supp. 591 (N.D. Fla. 1970).

17 See, e.g., Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971);

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 306

F.Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969) ; Glover v. Daniel, 434 F.2d 617

(5th Cir., 1970); Smiley v. City of Montgomery, 350 F. Supp. 451

(M D Ala 1972) • West v. Board of Education of Prince George’s

County, 165 F.Supp. 382 (D. Md. 1958); Mills v. Board of Edu

cation of Ann Arundel, 30 F.Supp. (D. Md. 1938).

15

vate employers,18 and by labor unions.19 Jurisdiction over

federal employment discrimination actions was expressly

upheld under §1981 in Bowers v. Campbell, 505 F.2d 1155

(9th Cir. 1974).

The class of persons protected by section 1981 is de

scribed in the all encompassing language to be “ [a]ll per

sons within the jurisdiction of the United States.” Had

Congress wished to limit the statute to exclude federal

discrimination, it knew how. Section 1983, 42 U.S.C., ex

pressly limits coverage action under color of the state law,

as did a number of other post Civil War civil rights pro

visions. See, e.g., 16 Stat. 140, §§l-3.20

18 See, e.g., Sanders v. B olls Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th

Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971) ; Bice v. Chrysler

Corp., 327 F.Supp. 80 (E.D. Mich. 1971) ; Hackett v. McGuire

Brothers Inc., 445 F.2d 442 (3d Cir. 1971) ; Young v. International

Tel. & Tel. Co., 438 F.2d 737 (3d Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) Brown v. Gaston

County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 93 S. Ct. 319 (1972); Boudreau v. Baton Bouge

Marine Contracting, 437 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971); Caldwell v.

National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 998 (1970) ; Brady v. Bristol Myers, 452 F.2d 621 (8th

Cir. 1972) ; Bennett v. Gravelle, 323 F.Supp. 203 (D. Md.

1971); Copeland v. Mead Corp., 51 F.R.D. 266 (N.D. Ga. 1970);

hazard v. Boeing Co., 322 F.Supp. 343 (E.D. La. 1971) ; Long

v. Ford Motor Co., 352 F.Supp. 135 (E.D. Mich. 1972) ; Guerra

v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 350 F.Supp. 529 (S.D. Tex. 1972);

Jenkins v. General Motors Corp., 475 F,2d 764 (5th Cir. 1973).

19 Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476 (7th. Cir.

1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970); James v. Ogilvie, 310

F.Supp. 661 (N.D. 111. 1970) ; Guerra v. Manchester Terminal

Corp., 350 F.Supp. 529 (S.D. Tex. 1972) ; Johnson v. Goodyear

Tire & B uller Co., 349 F.Supp. 3 (S.D. Tex. 1972) ; Jenkins v.

General Motors Corp., 475 F.2d 764 (5th Cir. 1973).

20 The criminal provisions of section 2 of the 1870 Civil Rights

Act, 16 Stat. 140, apply only to conduct under color of state law;

the criminal provisions of the 1866 Act apply to conduct under

color of any law. 14 Stat. 27. See n.22, infra, p. 17.

16

That section 1981 prohibits federal discrimination is com

pelled by District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973) and Tillman v. Wheaton Haven Recreation Asso.,

410 TJ.S. 431 (1973). Section 1981 was originally enacted

as part of Section 1 of the 1866 Civil Eights Act, 14 Stat.

27. Section 1 of that Act protected, not only the rights now

covered in §1981, including the right to contract, but also

the right to buy and own real property. Manifestly if any

one of the rights covered by section 1 was protected against

federal discrimination, all must have been, for the enumera

tion of rights draws no distinction among them. Subse

quent to 1866, section 1 of the Civil Eights Act was divided

into two sections; the provisions regarding real property

were placed in 42 U.S.C. §1982,21 and the other provisions

in §1981. This restructuring, however, involved no change

in substance. The scope of §1981 and §1982 are necessarily

the same. In Tillman v. Wheaton Haven Recreation Asso.,

410 TJ.S. 431 (1973), the Court held:

The operative language of both §1981 and §1982 is

traceable to the Act of April 9, 1866, e.31, 1, 14 Stat.

27. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 TJ.S. 24, 30-31 (1948). In light

of the historical interrelationship between §1981 and

§1982, we see no reason to construe these sections

differently . . .

410 U.S. at 439-40. Since the Court had concluded that

§1982 covered discrimination by private clubs, it held that

§1981 did as well.

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948), and District of Co

lumbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973), hold that section 1982

applies to discrimination by the federal government.

21 “All citizens of the United States shall have the same right,

in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and

personal property.”

1 7

That provision bars

all such discrimination, private as well as public, fed

eral as well as state. Jones v. Alfred II. Mayer & Co.,

supra, at 413. With this in mind, it would be anom

alous indeed if Congress chose to carve out the Dis

trict of Columbia as the sole exception to an act of

otherwise universal application. And this is all the

more true where, as here, the legislative purposes

underlying §1982 support its applicability in the Dis

trict. The dangers of private discrimination, for

example, that provided a focal point of Congress’

concern in enacting the legislation, were and are, as

present in the District of Columbia as in the States,

and the same considerations that led Congress to ex

tend the prohibitions of §1982 to the Federal Govern

ment apply with equal force to the District, which is

a mere instrumentality of that Government. 409 U.S.

at 422.22 23 (Emphasis added).

The reasoning of Carter is fully applicable to §1981 ;33 since

§1982 applies to the Federal government, §1981 does so

as well.

The legislative background of the 1866 Civil Rights dem

onstrates the correctness of Carter, Hodge and Tillman,

and gives no reason to believe that Congress wTould have

intended to deny to newly freed slaves protection from

discrimination by federal officials.24 It is unlikely that Con-

22 See also Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 97, n,2 (1945)

(§2 of the 1866 Act, rendering criminal certain discrimination

against “any inhabitant of any State, Territory or District,” ap

plies to federal officials).

23 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499 (1954), found “unthink

able” the suggestion that while the states were prohibited from dis

criminating in education the federal government was not. On the

extent and nature of racial discrimination in federal service, see

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 545 n.22 (1974).

24 The abolitionists in control of Congress in 1866 had for a

generation been anxious to abolish slavery and all its trappings

1 8

grass, having forbidden slavery throughout the nation, in

tended by section 1 of the Civil Eights Act to abolish the

“badges of slavery” only in the states and to leave them

intact in the nation’s capitol. See Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer

Co., 392 ILS. 409, 439 (1968).25 The memory of the mis

treatment of blacks by federal officials under the Fugitive

Slave Act was still fresh in the minds of abolitionists in

1866.26 Freedmen’s Bureau agents were reported to be

more sympathetic to the desires of white Southern

planters than the needs of freedmen..27 By April of

1866, Congress was aware of President Johnson’s oppo

sition to its reconstruction program, and believed that he

was actively undermining enforcement of new legislation

and dismissing federal officers who supported Congress’

policies.28 That concern about the conduct of federal offi-

in the District of Columbia. Henry B. Stanton, in an address to

the Massachusetts legislative urging abolition in the District of

Columbia, had argued: “ [Hjaving robbed the slave of himself,

and thus made him a thing, Congress is consistent in denying to

him aU the protection of the law as a man. His labor is coerced

from him by laws of Congress: No bargain is made, no wage is

given . . . There is not the shadow of legal protection for the

family state among the slaves of the District . . . No slave can

be a party before a judicial tribunal, . . . in any species of action

against any person, no matter how atrocious may have been the

injury received. He is not known to the law as a person: much

less, a person with civil rights . . . Congress should immediately

restore to every slave, the ownership of his own body, mind and

soul, transfer them from things without rights, to men with rights

. . the slave himself should be legally protected in life and

limb, in his earnings, his family and social relations, and his

conscience.” ten Broek, Equal Under Law, p. 46, 41-57 (1951).

25 Congress also had ample reason for concern that the federal

officials of the Freedmen’s Bureau, established in 1865, were seri

ously mistreating and exploiting the newly freed black former

slaves. G. Bentley, History of the Freedmen’s Bureau 77 84

125-132 (1955).

26 See J. Ten Broek, Equal Under Law, 57-65 (1951) ; Ableman

v. Booth, 21 How. (62 U.S.) 506 (1858).

27 See e.g. K. Stamp, The Era of Beconstuetion, 133-34 (1965).

28 See M. King, Lyman Trumbull, 293-95 (1965).

19

eials is manifest in other provisions of the 1866 Civil Rights

Act, which compels federal marshalls, on pain of criminal

punishment, to enforce the Act,29 expressly requires that

the district attorneys and other officials he paid for en

forcing the Act at the usual rates,30 and authorized the

circuit courts, rather than the President, to appoint com

missioners with the power to arrest and imprison persons

violating the Act.

The 1866 Civil Rights Act, in addition to forbidding em

ployment discrimination in section 1, expressly provided a

judicial remedy:

[T]he district courts of the United States, within

their respective districts, shall have . . . cognizance

. . . concurrently within the circuit courts of the United

States, of all cases, civil and criminal, affecting per

sons who are denied . . . any of the rights secured to

them by the first section of this act . . .

14 Stat. 27. This provision is now incorporated in 28

U.S.C. §1343(4).31

It is particularly unlikely that the Congress which en

acted the 1866 Civil Rights Act could have intended that,

to the extent that federal officials violated its provisions,

2914 Stat. 28, §5.

3014 Stat. 29, §7.

81 “ The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any

civil action authorized by law to be commenced by any person:

-y-•vc v.-

(4) To recover damages or to secure equitable or other relief

under any Act of Congress providing for the protection of

civil rights, including the right to vote.”

See Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 508, n.10 (1939).

2 0

aggrieved citizens would have no legal remedy.32 The aboli

tionists who finally won control of the Congress in the

1860’s and 1870’s had long maintained that the rights de

scribed in Reconstruction Amendments, and legislation

were not new, but already existed by virtue of the privi

leges and immunities clause and the Bill of Rights.33

The purpose of such Amendments and legislation was,

above all, to make those rights enforceable. The 1866

Civil Rights Act was entitled “An Act to protect all Persons

in the United States in the Civil Rights, and Furnish the

Means of their Vindication.” 14 Stat. 27 (emphasis added)

Congressman Wilson, speaking in favor of the 1866 Civil

Rights Bill, explained:

Mr. Speaker, I think I may safely affirm that this

bill, so far as it declares the equality of all citizens

in the enjoyment of Civil rights and immunities, merely

affirms existing law. We are following the Constitu

tion. We are reducing to stature form the spirit of

the Constitution. We are establishing no new right,

declaring no new principle. It is not the object of

this bill to establish new rights, but to protect and

enforce those which already belong to every citizen.

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong. 1st Sess. 1117.

32 If Congress had wanted to limit jurisdiction to discrimina

tion involving state action, it knew how to do so. Sections 2 and 3

of the 1870 Civil Rights Act and section 1 of the 1871 Civil Rights

Act expressly restrict their coverage to action taken under color

of state law, as does 28 U.S.C. §1343(3). No such limitation is

to be found in section 2 of the 1866 Act or section 1343(4), and

its absence must be taken as revealing Congressional intent to do

just what those provisions said— confer jurisdiction over all vio

lation of §1981, regardless of whether the violation may be by state

officials, federal officials, or private parties.

33 See generally ten Brock, Equal Under Law (1951); Graham,

“ The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the Fourteenth Amend

ment,” 1950 Wise. L. Rev. 479; Graham, “ The Conspiracy Theory

of the Fourteenth Amendment,” 47 Yale L.J. 371 (1938).

21

Since federal discrimination was already forbidden by the

Fifth Amendment, to hold the 1866 Civil Rights Act un

enforceable against federal defendants would be to render

the Act, in this regard, nugatory.

Section 1981 entails in certain instances34 35 a waiver

of sovereign immunity. The Congress which enacted section

1981 had no fondness for sovereign immunity, and could not

have contemplated that ex-slaves aggrieved by federal mis

conduct would have to seek a remedy through a private

bill.36 This Court has already made clear that it will not “ as

a self-constituted guardian of the Treasury import immu

nity back into a statute designed to limit it.” Indian Trading

v. United States, 350 U.S. 61, 69 (1955), or “whittle down

. . . by refinements” a statute affecting sovereign immunity.

34 No sovereign immunity would be involved in an action for

injunctive relief or to enforce the regulation requiring back pay.

See pp. 32-35, infra. Section 1981, in conjunction with §1343(4),

covers ordinary damages and certain other appropriate relief.

35 That Congress, only three years earlier, led by many of the

prominent abolitionists, had enacted the first comprehensive

waiver of federal immunity in an attempt to end the long stand

ing practice of seeking redress from Congress through private

bills. President Lincoln, in his first State of the Union message,

had urged such abolition:

It is important that some more convenient means should be

provided, if possible, for the adjustment of claims against

the Government especially in view of their increased number

by reason of the war. It is as much the duty of Government

to render prompt justice against itself in favor of citizens

as it is to administer the same between private individuals.

The investigation and adjudication of claims in their nature

belong to the judicial department.

Schlesinger and Israel, The State of the Union Messages of the

President, v. 2, 1060 (1966) (Emphasis added). The legislation

waiving that immunity was enacted largely to end the practice

of redressing grievances through private bills, which left many

citizens without a remedy, fostered lobbyists pressing dubious

claims, and corrupted the Congress. See> Cong. Globe, 38th Cong.,

1st Sess. 1674-75.

22

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 340 U.S. 543, 550 (1950).36

On the contrary, precisely because that immunity “gives

the government a privileged position, it has been appro

priately confined,” Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Fi

nance Corp., 306 U.S. 381, 388 (1938), and any authority

to sue “ is to be liberally construed/-' United States v. Shaw,

309 U.S. 495, 502 (1939). When Congress establishes by

statute a legal right, including a right against the federal

government, it must be deemed enforceable by the courts

unless there is an unequivocal congressional intent to the

contrary.87

2. The Mandamus Act

Section 1361, 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of

any action in the nature of mandamus to compel an

officer or employee of the United States or any agency

thereof to perform a duty owed to the plaintiff.

This provision, enacted in 1962, was intended to confer

upon the district courts the mandamus power until then

limited to the District Court for the District of Columbia.

Jarrett v. Resor, 426 F.2d 213 (9th Cir. 1970); Rural Elec

trification Administration v. Northern States Power Co.,

373 F.2d 686 (8th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 945. A

writ of mandamus is available to compel a federal officer

to perform any ministerial act, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S.

(1 Cranch) 137 (1803), regardless of whether the official’s

obligation arises under the Constitution, a federal statute,

86 See also Rayonier v. United States, 352 U.S. 315, 320 (1957).

87 Minnesota v. United States, 305 U.S. 382, 388, n.5 (1939);

United States v. Eellard, 322 U.S. 363 (1944); United States v.

Jones, 109 U.S. 513 (1883), 519-521.

23

a regulation or an Executive Order. Leonhard v. Mitchell,

473 F.2d 709, 713 (2d Cir. 1973).

The defendant officials clearly have such a ministerial

duty to make promotions without discrimination on the

basis of race. The Fifth Amendment guarantee of due

process of law absolutely prohibits the federal government

from discriminating against blacks in employment, educa

tion, or any other regard. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1954).38 The authority of the defendants in personnel mat

ters is strictly circumscribed by section 7151 of Title 5 of

the United States Code, which declares it to be the official

policy of the United States “ to insure equal employment

opportunities for employees without discrimination be

cause of race, color, religion, sex or national origin,” and

directs that the President shall carry out this policy.39 Of

course, racial discrimination by defendants is also for

bidden by the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981,

88 “ [T]he Constitution of the United States, in its present form,

forbids, so far as civil and political rights are concerned, discrim

ination by the General Government, or by the States, against any

citizen because of his race.” 347 U.S. at 499, quoting Gibson v.

Mississippi, 162 U.S. 595, 591 (1866). The Senate Report on the

1972 amendments to Title YU concluded on the basis of Bolling

that “ [t]he prohibition against discrimination by the Federal

government, based upon the Due Process clause of the Fifth

Amendment, was judicially recognized long before the enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” S.Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971) 13. The Fifth Amendment has been expressly

held to bar federal discrimination in employment Davis v. Wash

ington, 352 F.Supp. 187 (D.D.C. 1972) a fd , 512 F.2d 956 (D.C.

Cir. 1975), petition for writ of certiorari pending, No. 74-1492;

Faruki v. Rogers, 349 F.Supp. 723 (D.D.C. 1972) (three judge

district court).

39 Section 7151 is no mere assertion of social goals; it is a direct

and Unequivocal command to the exemitive branch not to discrim

inate against petitioner because of his race. See Henderson v. De

fense Contract Administration.. 370 F.Supp. 180 (S.D.N.Y. 1973) ;

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 546 n.21 (1974).

24

infra, pp. 14-19, and by federal regulations and Executive

Orders.40

The lower courts have held that mandamus is available

to compel federal defendants to hire and promote without

regard to race. Beale v. Blount, 461 F.2d 1133 (5th Cir.

1972) ; Penn v. Schlesinger, 490 F.2d 700, 704-05 (5th

Cir. 1973), reversed on other grounds, 497 F.2d 970 (5th

Cir. 1974); Thorn v. Richardson, 4 EPD If 7630, at p. 5490

(W.D. Wash. 1971). At least since Service v. Dulles, 354

U.S. 363 (1957), this Court has recognized that federal

personnel decisions are subject to judicial scrutiny. Samp

son v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61, 71 (1974).

Mandamus is also available to enforce a ministerial duty

to pay a particular sum of money to the plaintiff,41 though

40 Part 713, 5 C.F.R., implements, inter alia, a series of Ex

ecutive Orders dating back to 1948. See E.O. 9980, July 26, 1948;

E.O. 10590, January 18, 1955; E.O. 10925, March 6, 1961; E.O.

11246, September 24, 1965; E.O. 11478, August 8, 1969; E.O. 11590.

Both part 713 and Executive Order 11478 establish that it is

the policy of the government of the United States “ to provide

equal opportunity in federal employment for all persons, to pro

hibit discrimination in employment because of race,” E.O. 11478,

§1; 5 C.F.R. §713.202; and both provide that each executive de

partment and agency “shall establish a program to assure equal

opportunity in employment and personnel operations without re

gard to race.” E.O. 11478, §2; C.F.R. Part 713.201(a).

41 In United States ex rel. Parish v. MacVeagh, 214 U.S. 124

(1909), the Secretary of the Treasury had refused to pay the

plaintiff $181,358.95, whieh payment was required by a special

Act of Congress. This Court held that mandamus was available

to compel the Secretary to issue a draft in that amount. 214 U.S.

at 138. In Miguel v.' McCarl, 291 U.S. 442 (1934), this Court

held that mandamus was available to compel the payment of a

pension unlawfully withheld by the Comptroller General and the

Army Chief of Finance. In Roberts v. United States ex rel.

Valentine, 176 U.S. 221 (1900), this Court upheld a writ of

mandamus directing the Treasurer of the United States to pay

interest on certain bonds issued by the District of Columbia.

See also Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 211 U.S. 249

(1908); Work v. United States ex rel. Lynn, 266 U.S. 161 (1924);

City of New York v. Ruckelshaus, 358 F.Supp. 669 (D. D.C.

1973) .

25

not to compel payment in an ordinary disputed tort or

contract action. In the instant action plaintiff seeks, inter

alia, an award of back pay. Were this a mere claim for

consequential damages mandamus would be inappropriate.

But the applicable regulations place upon defendants an

express obligation to compute and award back pay in

cases of racial discrimination, rendering the award of such

back pay ministerial.42 The mandatory nature of back pay

awards under the regulation is somewhat more favorable

to employees than the standard applied by courts in

Title Y II litigation, which involves a limited degree of

discretion. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 43 U.S.L.W.

4880 (1975). I f the district court finds discrimination, the

defendants will have an absolute obligation to provide back