Sims v Dutton Supplemental Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1966

72 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sims v Dutton Supplemental Brief for Petitioner, 1966. f8ece978-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/17fac21b-93a1-4647-8fd7-d2b36f2ad382/sims-v-dutton-supplemental-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

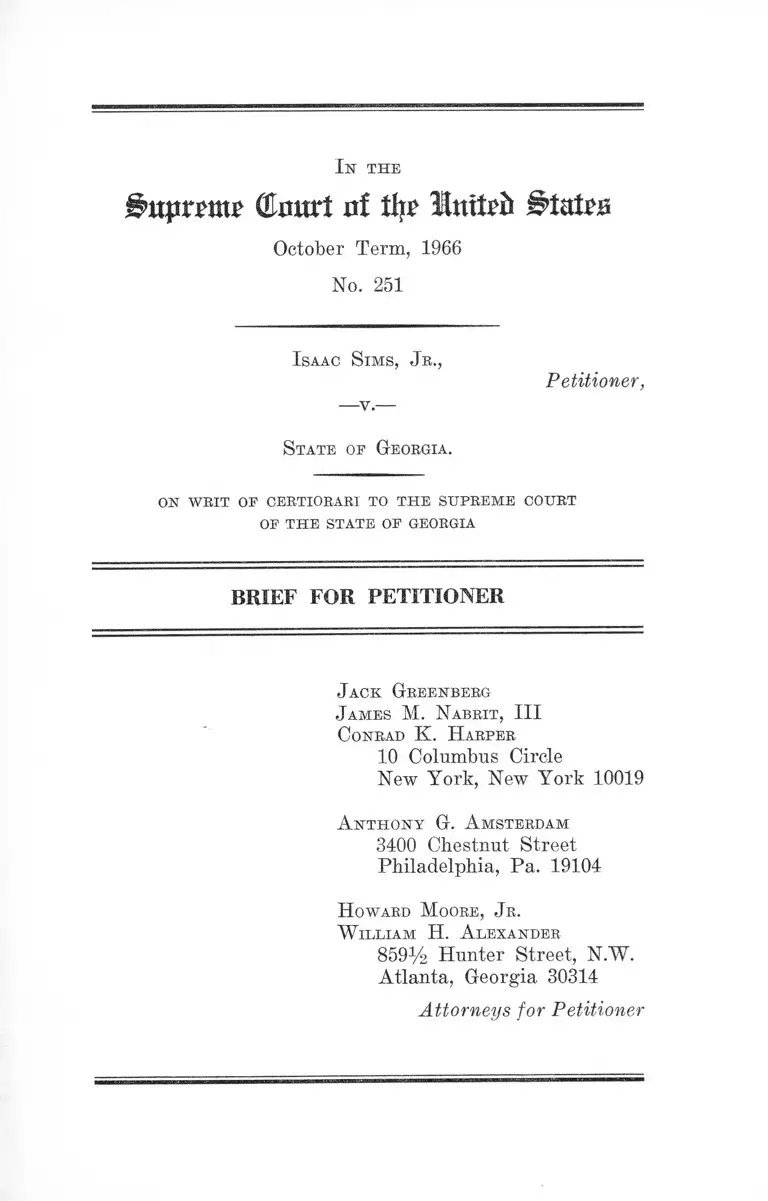

I n th e

g>ttprrmr Court nf % luttrfc #tatro

October Term, 1966

No. 251

I saac S im s , J r .,

Petitioner,

S tate oe Georgia.

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OP THE STATE OP GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit, I I I

C onrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

H oward M oore, J r .

W illiam H. A lexander

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................. -........................................... 1

Questions Presented ....... .................................................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved----- 4

Statement of the Case............................................... -...... - 5

Summary of Argument ........................................ 9

A rgum ent

I. Petitioner’s Constitutional Rights Were Violated

by the Use at His Trial of Confessions Which

(A) Were Not Reliably Determined to Be Vol

untary, in Violation of Jackson v. Denno, 378

U.S. 368; (B) Were Judged by Standards of

Voluntariness That Were Not in Accord Consti

tutional Requirements; (C) Were Obtained in

Inherently Coercive Circumstances Following

the Physical Brutalization of Petitioner While

in Custody; and (D) Were Obtained in Violation

of Petitioner’s Sixth Amendment Right to the

Assistance of Counsel ......................... ......... ........ 13

Introduction ________ ._____-.................................. 13

A. The Decision Below Is in Plain Conflict With

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 ................... 14

B. The Standards Applied Below to Determine

Voluntariness Were Insufficient to Satisfy

the Constitutional Requirements ..... ...... ...... 22

11

0. Petitioner’s Confession Was Obtained in In

herently Coercive Circumstances and After

He Had Been Physically Brutalized While in

Custody, and Its Hse to Convict Him Vio

PAGE

lates the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment ............ ................. ............ 26

1. Facts and Circumstances Surrounding

the Confession ............................. .............. 26

2. The Confessions Were Obtained in In

herently Coercive Circumstances and

Their Use Violated the Due Process

Clause .......................................................... 36

3. The Physical Violence Inflicted on Sims

Is Sufficient by Itself to Invalidate the

Confessions ..................................... 39

D. The Decision Below Violates Petitioner’s

Sixth Amendment Right to Counsel in Con

flict With Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478,

and Other Decisions of This Court ....... 44

II. Petitioner Was Denied Equal Protection of the

Laws by Rulings of the Courts Below Refusing

Evidence That Negroes Were Systematically

Excluded From Grand and Petit Juries in

Charlton County, and Overruling His Challenge

to Those Juries on Grounds of Racial Discrimi

nation in Their Selection ..................... .............. 47

A. The Georgia Courts Unconstitutionally Re

fused to Receive Petitioner’s Proffered Proof

of Racial Discrimination in the Selection of

Jurors 49

I l l

B. The Use of Tax Digests Containing Racial

Designations, As Required by Statute, in

PAGE

Georgia’s System of Jury Selection is Un

constitutional .................................................... 52

C. The Results of Jury Selection in the Instant

Case Establish a Prima Facie Case of Racial

Discrimination .................................................. 56

Conclusion .......................................................................... 61

Appendix on Computation ................................................ 63

T able op Cases :

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 .... ............ .... ........ 53, 56

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 ....................... 50

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143 ............................ 25

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 .......... .....12,13, 55, 56, 59, 60

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U.S. 199 ............................ 42

Bram v. United States, 168 U.S. 532 .......................... 43

Brodie v. United States, 295 F.2d 157 (D.C. Cir. 1961) 21

Brooks v. Beto, No. 22,809, 5th Cir., July 29, 1966 ....... 50

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 _______ ____ _____ ___ 57

Brubaker v. Dickson, 310 F.2d 30 (9th Cir. 1962), cert.

den. 372 U.S. 978 ............................ ................... .......... . 45

Bryant v. State, 191 Ga. 686, 13 S.E.2d 820 (1941) ....16, 20

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442 ......................................11, 50

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 .................................. 52,57

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 ............. ................. 25

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. (19 U.S.) 264 ............... 14

Coker v. State, 199 Ga. 20, 33 S.E.2d 171 (1945) .....16, 20

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129.................. ....... ..... 11, 50

IV

Commonwealth v. Coyle, 190 Pa. Super. 509, 154 A.2d

412 (1959) .............................................. ....................... - 21

Commonwealth ex rel. Gaito v. Maroney, 416 Pa. 199,

204 A .2d 758 (1964) ................... ................... -............. 22

Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control

Board, 367 U.S. 1 .................................... .................... . 52

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 .............. ...... ................. —- 14

Crooker v. California, 357 U.S. 433 ............. .......... ...... 45

Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568 ...................38, 42, 43

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U.S. 737 ........................ 41

Davis v. State, 245 Ala. 589, 18 So.2d 282 (1944) ....... 21

Downs v. State, 208 Ga. 619, 68 S.E.2d 568 (1952) ..16,17, 20

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 ................ 2,11,14,44, 45

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 .......................13, 50, 57

Pikes v. Alabama, 352 U.S. 191 ...............2,14, 36, 37, 38, 42

Garrett v. State, 203 Ga. 756, 48 S.E.2d 377 (1948) ....16, 20

Griffith v. Rhay, 282 F.2d 711 (9th Cir. 1960), cert. den.

364 U.S. 941...................................................................... 45

PAGE

Haley v. Ohio, 322 U.S. 596 ....................................... ...37, 38

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 P.

Supp. 156 (E.D. Va. 1964), aff’d sub nom. Tancil v.

Woolls, 379 U.S. 19 ................... ......... ................. 12,53,54

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503 ...............25, 30, 37, 38

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776 .................................. 14

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 ........... ....................... 50

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 .......................................... 13, 57

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 .............2, 8, 9,13,14,15,16,

17.18,19, 20, 21, 22

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 .......................41,44

Johnson v. Pennsylvania, 340 U.S. 88

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 .......... 38

Labat v. Bennett, No. 22,218, 5th Cir., Aug. 15, 1966 ....

Lisenba v. California, 314 U.S. 219 .................... -........

Lopez v. State, 384 S.W.2d 345 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App.

1964) ................................................................... -............

Malinski v. New York, 324 U.S. 401............. ..... ......... 37,

Marion v. State, 387 S.W.2d 56 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App.

1964) .............. ...... ........................................-...................

Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 ......-...............

Maxwell v. Bishop, E.D. Ark., No. PB-66-C-52, decided

August 26, 1966 ............................................ .................

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 ...........................41,42,

Moorer v. South Carolina, 4th Cir., No. 10,526, Memo

randum and Order of July 18, 1966 ..........................

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 ......................... ............

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 ...... ....................50. 54,

Opper v. United States, 348 U.S. 84 .................. ..........

Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560 .......................... 24, 37,

Payton v. United States, 222 F.2d 794 (D.C. Cir.

1955) ................................................................... ........... 39,

People v. Caruso, 246 N.Y. 437, 159 N.E. 390 (1927) ....

People v. Megladdery, 40 Cal. App. 748, 106 P.2d 84

(1940) ........................... .................... -----....... —.............

People v. Walker, 374 Mich. 331, 132 N.W.2d 87 (1965)

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 ..................................

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 ............. ........ — .... .

Rabinowitz v. United States, No. 21,256, 5th Cir., July

20, 1966 ................. .......................... .................... ......... 50,

50

42

22

43

22

46

3

44

3

50

57

19

43

42

21

21

22

50

46

53

VI

PAGE

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 ................................... . 50

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 ...............10,14,19, 23,

24, 25, 43

Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966) .......... 51

Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7, 136 S.E.2d 766 (1964)

1, 5, 6, 50

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 .................................. 13, 50, 57

Smith v. United States, 348 U.S. 147 .......................... 19

Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315 ........ ..... .......... ..42, 46, 47

State v. Brewton, 395 P.2d 874 (Ore. 1964) ................... 22

State v. Burke, 27 Wis. 244, 133 N.W.2d 753 (1965) .... 22

State v. Costello, 97 Ariz. 220, 399 P.2d 119 (1965) .... 22

State v. Taylor, 133 N.W.2d 828 (Minn. 1965) .... 22

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 ............... 17, 20, 21, 40, 42

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S, 202 ......................... ........ 61

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 ....................................... 3

Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U.S. 62 .............................. 38

United States v. Atkins, 323 F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 53

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959) ..... ....................................................... . 51

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353 (E.D.

La. 1963), aff’d 380 U.S. 145 .................................. 12,53

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53

(5th Cir. 1962) ............................................................... 51

Wan v. United States. 266 U.S. 1 .................. .............. 14, 24

Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547 ......................... .............. . 25

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 .......................................... 37

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 .................................. 56

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 .............. . 19

V ll

S t a t u t e s :

PAGE

Ga. Code Ann. §27-209 (1933) .......................... -.... 33,45,46

Ga. Code Ann. §27-212 (1933) ........................................ 33

Ga. Code Ann. §38-411 (1933) ............ ......... .4,16, 20, 22, 23

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 (1965 Rev. Yol.) ..... ....4,12,47,48,

49, 52, 53

Ga. Code Ann. §59-108 (1965 Rev. Vol.) ....................... 47

Ga. Code §92-6307 (1933) ................. ......... ...5,12,47,52,55

N. Y. Code Grim. Proc. §395 ................................ ..... 19

N. Y. Code Crim. Proc. §465 .......................................... 21

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ............................................................ 2

Other. A u t h o r it ie s :

Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice & Procedure

§2281 (Rules ed. 1958) .................................................. 21

24 C.J.S., Criminal Law, §1452 (1961) .......................... 21

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory to the Jury Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv.

L. Rev. (1966) [to be published in Fall, 1966] ....... 58

Hoel, Introduction to Mathematical Statistics (1962) 59

7 Wigmore, Evidence §2071 (3d ed. 1949) .................. 19

In t h e

&>vtyxm\t (Eourt ni tliT lititpfr BXuUb

October Term, 1966

No. 251

I saac S im s , J r .,

S tate of Georgia.

Petitioner,

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia and the

dissenting opinion of Justice Almand are reported at 221

Ga. 190, 144 S.E.2d 103. A prior conviction for the same

offense involved here was set aside in an opinion reported

as Sims v. Balk,com, 220 Ga. 7, 136 S.E.2d 766 (1964).

Jurisdiction

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was entered

July 14, 1965 (R. 345) and rehearing was denied July 26,

1965 (R. 351). On October 19, 1965, Mr. Justice Black

extended the time for filing the petition for writ of cer

tiorari to and including November 23, 1965 (R. 355). The

petition for writ of certiorari and the motion for leave

to proceed in forma pauperis were filed November 22, 1965,

and granted June 20, 1966 (384 U.S. 998; R. 356-57). Re

2

view was limited to the first five questions presented by

the petition (R. 356-57).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here, the deprivation of his rights, privileges and

immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by a conviction and sentence to death ob

tained on the basis of a confession made under inherently

coercive circumstances within the doctrine of Fikes v.

Alabama, 352 U.S. 191.

2. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by the failure of the Georgia courts to afford

a fair and reliable procedure for determining the volun

tariness of his alleged coerced confession is disregard of

the principle of Jack-son v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368.

3. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment right

to counsel as declared in Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478,

was violated by the use of his confession obtained during

police interrogation in the absence of counsel, or whether

petitioner’s right to counsel was effectively waived.

4. Is a conviction constitutional where:

(a) local practice pursuant to state statute requires

racially segregated tax books and county jurors are selected

from such books;

(b) the number of Negroes chosen is only 5% of the

jurors but they comprise about 20% of the taxpayers; and

3

(c) a Negro criminal defendant’s offer to prove a prac

tice of arbitrary and systematic Negro inclusion or exclu

sion based on jury lists of the prior ten years is disal

lowed?1

1 In this brief petitioner will not urge reversal of the decision below

upon the ground presented by the fifth question in his petition for certi

orari, relating to racially discriminatory application of the death penalty

for rape. Petitioner, a pauper, was tried in October, 1964. At that time

he had available, to support the contention urged in his plea in abatement

(E. 17-18) that Georgia juries discriminate against Negroes in capital

sentencing for rape, only the published United States Bureau of Prisons

figures showing that between 1930 and 1962 fifty-eight Negroes and three

whites were executed for rape in the State. His proffer of this evidence

was rejected by the trial judge (R. 93-95)—wrongly we believe— and

that ruling was preserved for review by the Georgia Supreme Court (E.

323, 333) and subsequently challenged in the petition for certiorari here.

However, since petitioner’s trial, substantial new evidence has become

available on the issue. Pursuant to a rigorously conceived research design,

an empirical study of the effect of race upon capital sentencing for rape

in eleven Southern States including Georgia was undertaken in the sum

mer of 1965 under the sponsorship of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and

Educational Fund. The results of that study are being subjected to

statistical analysis on a State-by-State basis and have been proffered or

presented through expert testimony in a number of pending cases. See

Maxwell v. Bishop, E.D. Ark., No. PB-66-C-52, decided August 26, 1966,

stay granted by Mr. Justice White, September 1, 1966; Moorer v. South

Carolina, 4th Cir., No. 10,526, Memorandum and Order of July 18, 1966

(describing the study). The study lays a firm factual foundation for the

attack made in this case, the cases cited, and others, challenging Southern

capital punishment for rape under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The study to date has involved the expenditure of considerably more

than $35,000. Since it supplies evidence supporting petitioner’s contention

which is vastly more illuminating than the meager showing petitioner

attempted to make on the present record in 1964 and—being plainly

without petitioner’s financial means—obviously will support a “ substantial

allegation of newly discovered evidence” within the meaning of Townsend

v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293, 313 (1963), it will be available to petitioner in

subsequent proceedings, whether on remand following reversal of peti

tioner’s conviction on the grounds urged in this brief or in state or federal

collateral attack proceedings. In these circumstances, petitioner’s counsel

would not urge this Court to premature consideration of a vitally signifi

cant constitutional question on the scanty and relatively uninformative

record of the present proceeding.

4

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

This case involves the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following Georgia Statutes:

Ga. Code §38-411 (1933) :

Confessions must be voluntary.—To make a confession

admissible, it must have been made voluntarily, with

out being induced by another, by the slightest hope of

benefit or remotest fear of injury.

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 (1965 Kev. Y o l.) :

Revision of jury lists. Selection of grand and traverse

jurors.—Biennially, or, if the judge of the superior

court shall direct, triennially on the first Monday in

August, or within 60 days thereafter, the board of

jury commissioners shall revise the jury lists.

The jury commissioners shall select from the books

of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the per

sons so selected on tickets. They shall select from these

a sufficient number, not exceeding two-fifths of the

whole number, of the most experienced, intelligent, and

upright citizens to serve as grand jurors, whose names

they shall write upon other tickets. The entire number

first selected, including those afterwards selected as

grand jurors, shall constitute the body of traverse

jurors for the county, to be drawn for service as pro

vided by law, except that when in drawing juries a

name which has already been drawn for the same term

as a grand juror shall be drawn as a traverse juror,

such name shall be returned to the box and another

5

drawn in its stead. (Acts 1878-79, pp. 27, 34; 1887, p.

31; 1892, p. 61; 1899, p. 44; 1953, Nov. Sess., pp. 284,

285; 1955, p. 247.)

Ga. Code §92-6307 (1933):

Entry on digest of names of colored persons.—The

tax receivers shall place the names of the colored tax

payers, in each militia district of the county, upon the

tax digest in alphabetical order. Names of colored and

white taxpayers shall be made out separately on the

tax digest. (Acts 1894, p. 31.)

Statement of the Case

Petitioner, Isaac Sims, an indigent, ignorant and illiter

ate Negro, is under a sentence of death by electrocution

imposed by the Superior Court of Charlton County, Georgia

following his conviction for the crime of rape. His con

viction was affirmed on appeal by the Supreme Court of

Georgia, which stayed execution pending this Court’s re

view of petitioner’s claims that he was denied rights pro

tected by the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioner had previously been indicted, convicted and

sentenced to death at the October 1963 Term of the Superior

Court for the same offense. That first conviction wTas set

aside on habeas corpus by the Supreme Court of Georgia,

which ordered a new trial on May 7, 1964. Sims v. Balkcom,

220 Ga. 7, 136 S.E.2d 766 (1964). No appeal from the first

conviction had been taken by Sims’ court-appointed coun

sel, the court reporter had destroyed his trial notes, exe

cution had been scheduled for November 13, 1963, and a

commutation of sentence had been denied (R. 58, 250-251).

One of Sims’ present counsel, Mr. Moore, entered the case

and initiated the habeas corpus proceedings resulting in

6

the Sims v. Bcilkcom decision and obtained a stay on the

day before Sims’ scheduled execution.

The indictment leading to this conviction, returned Octo

ber 6, 1964, charged that Sims raped Nola Jean Eoberts

on April 13, 1963, in Charlton County (E. 1). The trial

commenced the next day, October 7, 1964, and a jury re

turned a verdict of guilty without recommendation of

mercy on October 8, 1964 (E. 2).

The evidence upon which Sims was convicted consisted

principally of testimony by the prosecutrix that Sims

“ forced her car off the road, dragged her into the w-oods,

pulled her clothes off, and raped her” (Opinion below, E.

334), and that he “kept choking her and threatened to kill

her if she screamed” (ibid.). In addition, there was testi

mony by Miss Eoberts’ mother and her physician, Dr.

Jackson, as to her condition after the attack, and evidence

of several admissions and confessions by the defendant.

The circumstances of these admissions and confessions,

which Sims contends were involuntary and obtained by

coercion, are set forth in detail in Argument I below, pp.

26 to 36. The text of a written confession signed by Sims

while in custody appears at E. 226-227. Sims is unable to

read or write. The confession was written by a deputy

sheriff and read to Sims. The first three sentences and

last three paragraphs of the statement were admittedly

not statements by Sims but, rather, assertions of the vol

untariness of the confession written by the deputy and

read to Sims (E. 100-101, 103-104, 218-219).

Petitioner denied understanding the import of the state

ment and denied b .IS guilt in sworn testimony at a voir dire

hearing and in an unsworn statement before the jury (E.

134-135, 248). Sims, in his mid-twenties at the time of

arrest, was a pulpwood worker who quit school at age

seventeen or eighteen, having completed only the third

7

grade (R. 128-130). His understanding is severely limited

as is illustrated by the following testimony, which is a

mere sample of his incapacity as revealed in the record:

Mr. M oore: Do you know what is meant by “ the

statement can be used against you in court” !

Mr. Sims: Statement can be used against me?

Mr. Moore: Statement can be used against you in

court. Do you know what that means!

Mr. Sims: No, sir.

Mr. Moore: Do you know what it means to be in

formed of your legal rights?

Mr. Sims: Well, that’s like being good or something?

Mr. Moore: Is that what it means to you, Isaac?

Mr. Sims: Yes, sir. (R. 136)

* # # # #

Mr. M oore: Isaac, do you know what “ Constitutional

rights” means?

Mr. Sims: Do you mean good or something?

Mr. Moore: Is that what it means to you, Isaac?

Mr. Sims: Yes, sir. (R. 137)

The facts of record with respect to petitioner’s claim of

racial discrimination in the jury selection process are set

forth below in Argument II, pp. 47 to 48, infra.

Petitioner objected to the confessions and the testimony

about them on federal constitutional grounds by a series

of oral and written motions and pleas, including a pre

trial motion to suppress (R. 13), a motion to quash the

signed confession and to exclude the testimony concerning

it (R. 235), and motions to strike testimony (R. 212-213,

225). All the motions were overruled. An amended mo

tion for new trial renewed the objections (R. 24-44) and

was denied (R. 317). The federal claims were preserved

by bill of exceptions (R. 319, 321-322), and on appeal the

8

Supreme Court of Georgia rejected all of petitioner’s con

stitutional claims and held the confession was properly

-admitted in evidence (E. 334-343).

Petitioner’s objections to the standard used to determine

voluntariness under Georgia law were articulated in the

amended motion for new trial (R. 43-44). His objections,

based on Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, were overruled

by the Georgia Supreme Court in an opinion denouncing

the holding of Jackson as “illogical, impracticable and

utterly unsound” and expressing the hope that it would

be overruled, while at the same time attempting to show

that the Jackson holding was not applicable to this case in

view of certain Georgia laws (R. 337-342).

The federal objections based on jury discrimination were

also preserved throughout the proceedings below. Peti

tioner’s motion for change of venue, first plea in abatement,

and challenge to the array in the Superior Court alleged

that his Fourth Amendment rights of equal protection of

the laws and due process of law had been violated in that

grand and petit jury panels were selected in a racially

discriminatory manner (R. 3-4, 6-8, 10-11). The pleadings

contended that Negroes were systematically and arbitrarily

included or excluded from jury panels and that no Negro

had ever served as a jury commissioner {ibid.). The first

plea in abatement and challenge to the array also alleged

that the Charlton County Tax Digest from which jurors

were selected listed taxpayers separately on the basis of

race (R. 4, 7-8). After hearing testimony the court over

ruled petitioner’s objections (R. 5, 6, 8, 12, 70. 93, 95).

Petitioner offered in evidence certified copies of the grand

and traverse jury lists from 1954 to 1963 (R. 254-98). The

trial court ruled them, inadmissible (R. 72-73, 147). Peti

tioner’s bill of exceptions in the Supreme Court of Georgia

assigned these various rulings on the jury discrimination

claim as error (R. 319-322).

9

The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed, rejecting peti

tioner’s arguments on the merits (R. 330-332).

■ Petitioner offered to prove by certified copies of the

traverse and grand jury lists of 1954 to 1963 the pattern

in which Negroes had been systematically and arbitrarily

included or excluded from jury lists (R. 70-73). These

offers of proof were ruled inadmissible (R. 147) and this

ruling was upheld by the Georgia Supreme Court (R. 332-

33).

Summary of Argument

I.

The use at trial of confessions obtained from petitioner

while in police custody violated his right against depriva

tion of life without due process of law, for several reasons.

A. The issue of voluntariness of the confessions was

submitted to the trial jury without the prior judicial screen

ing required by Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368. The Su

preme Court of Georgia conceded as much, but took the

view that Jackson was inapplicable in Georgia by reason

of several aspects of Georgia confession practice—the re

quirement that confessions be corroborated, the require

ment that they be shown voluntary as a condition of

admissibility, and the trial court’s power to set aside an

unjust verdict of conviction— said to provide safeguards

not provided by the New York practice condemned in Jack-

son. However, each of these practices has its exact ana

logue in New York law and each is so obviously general,

if not universal, American practice in confession cases

that it blinks reality to suppose the Court in Jackson

imagined that any other practices would obtain in the trials

which Jackson was plainly designed to govern. Georgia

10

has here merely evaded, not distinguished, Jackson; and

its evasion should not he countenanced by the Court.

B. A standard was used to determine the voluntariness,

hence the admissibility, of petitioner’s confessions which

was not the standard imposed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Inquiry respecting voluntariness below was confined

to the issues (delimited by Georgia statute) whether peti

tioner’s statements were induced by promises or threats.

But under the Due Process Clause, any cumulation of

circumstances which saps the will of an accused and com

pels him to a confession not freely self-determined renders

the confession inadmissible even though no threats or

promises have been made. The narrow view taken by the

Georgia courts of the constitutional obligation of a State

to protect criminal defendants against the use of invol

untary confessions thus runs afoul of the holding in Rogers

v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534, and compels reversal of peti

tioner’s conviction.

C. Petitioner, an ignorant and illiterate Negro taken

into custody for the capital offense of rape of a white

woman, was subjected while surrounded by police to physi

cal brutality requiring hospital treatment. A short time

thereafter, still surrounded by police, without the oppor

tunity to see a friend or lawyer, and without effective

warning of his rights in view of his limited mentality, he

confessed the rape. Later, after he had been charged by

warrant, again surrounded by police and without having-

seen a friend or received effective caution, he was asked

to reaffirm his confession and did so. On these uncontested

facts, his confessions were coerced as a matter of law.

Any confession made in police custody shortly after a

prisoner’s blood has been spilled is inadmissible consistent

with due process of law. When to the physical brutality

11

suffered by petitioner there is added his mental inadequacy,

his isolation in police confinement, and the terrorizing cir

cumstance of his charge for rape of a white woman, the

totality of circumstances plainly makes out duress within

the prior forced-confession holdings of this Court.

D. The same circumstances firmly establish that peti

tioner was denied the right to counsel given by Escobedo

v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478. While petitioner did not request

counsel, Escobedo and cases decided prior to it make

plain that a request is not the invariable condition of the

protective right to counsel which Escobedo assures, and

that in some cases fundamental fairness precludes use of

a confession taken from an ignorant and uncounseled state

criminal defendant. Petitioner’s is such a case. His in

capacity to understand or protect his rights in the fearful

surroundings of his confinement by the police render the

taking of his initial confessions fundamentally unfair. And

the police stratagem of securing his reaffirmation after he

had been charged violates the command of the Sixth Amend

ment, as incorporated in the Fourteenth, that a criminal

“accused” be provided a lawyer once the proceedings

against him have progressed to the post-investigative stage.

II.

A. Georgia courts refused to permit petitioner to make

a full record on his claim that Negroes had been arbitrarily

barred from and limited in serving on Charlton County

grand and petit juries. In thus thwarting petitioner’s

rights, the Georgia courts were in clear violation of the

principle announced in Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129,

and Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442. In jury discrimination

cases, this Court has long relied upon records covering a

number of years in order to appraise present conduct in

the context of past action.

12

B. The Charlton County jury commissioners’ use of seg

regated tax digests, pursuant to Ga. Code §§59-106 and

92-6307, violates petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

to grand and petit juries selected without regard to race.

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F. Supp.

156 (E.D. Ya. 1964), aff’cl sub nom. Tancil v. Woolls, 379

U.S. 19, deprives the State of any justification for main

taining racially separate tax lists, and Georgia’s process

of selecting jurors from those lists, together with Charlton

County’s local practice of having the names of white tax

payers on white paper and Negroes on yellow paper, vio

lates the rule of Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559. Ga. Code

Ann. §59-106, specifying that jurors shall be chosen on the

basis of uprightness and intelligence, requires the jury

commissioners to employ vague, subjective criteria and

gives them a discretion in which the discriminatory oppor

tunities provided by the segregated digests create an un

constitutional probability of racial exclusion. Cf. United

States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, 396-97, aff’d, 380

U.S. 145.

C. Notwithstanding the Georgia courts refused to per

mit petitioner to make a full record on his jury discrim

ination claim, the facts shown—that only about 5% of the

jury list, from which his grand and petit juries were se

lected, were identified as Negroes although Negroes com

prised about 20% of the tax digest—made out a prima

facie case of racial discrimination. In support of this

claim, petitioner relies upon statistical computations wdiich

show a high degree of improbability that Charlton County

juries were selected without regard to race in October, 1964.

A gross disparity between the number of Negroes avail

able for jury service and those actually chosen appears,

and suffices to make the showing of improbability of color

blind selection required by the jury discrimination cases

13

generally, e.g., Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 131; Hill v.

Terns, 316 U.S. 400, 404; Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S.

584, 587. The instant case is controlled by Avery v. Georgia,

345 U.S. 559, where the Conrt, on a record quite similar

to petitioner’s regarding the jury selection process, held

that a prima facie case of racial discrimination had been

established. The probability that the selection process was

fairly used in Avery is much greater than the probability

that the process was fairly used in the instant case.

ARGUMENT

I.

Petitioner’ s Constitutional Rights Were Violated by

the Use at His Trial o f Confessions Which (A ) 'Were

Not Reliably Determined to Be Voluntary, in Violation

o f Jackson Denno, 378 U.S. 368 ; (B ) Were Judged

by Standards of Voluntariness That Were Not in Accord

With Constitutional Requirements; (C ) Were Ob

tained in Inherently Coercive Circumstances Following

the Physical Brutalisation o f Petitioner While in Cus

tody; and (D ) Were Obtained in Violation o f Peti

tioner’ s Sixth Amendment Right to the Assistance of

Counsel.

Introduction

At petitioner’s trial the State introduced testimony con

cerning an alleged oral confession by petitioner Isaac Sims

to Deputy Sheriff Jones (R. 210), and a written confes

sion signed by Sims purporting to give the details of the

crime (R. 226-27). Both the alleged oral confession (which

Sims denied making) and the signed statement were ob

tained April 13, 1963, while petitioner was in custody in

the Ware County Jail, as the sole suspect in a capital

felony. The prosecution also introduced testimony of a

14

state investigator that on the afternoon of April 15, 1963,

he read the written confession to Sims who said it was

true (R. 238). Sims stated at trial that he did not under

stand what he was doing when he signed the confession

and that he was innocent of the crime (R. 141, 248).

We urge that Sims’ rights under the Constitution were

violated by the use against him of these confessions, for

several distinct reasons grounded on decisions of this Court

decided prior to his trial, October 7, 1964 (R. 148, 249).

We submit first, that the procedure by which the trial

judge and jury determined the admissibility of petitioner’s

statements violated the due process requirements of Jack-

son v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368. Second, we urge that the

standards used to determine voluntariness were consti

tutionally deficient under Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534,

and Wan v. United States, 266 U.S. 1. Third, we argue

that the physical brutality and coercive circumstances sur

rounding the confessions prohibit their use under Fikes v.

Alabama, 352 U.S. 191, and similar cases. Fourth, we argue

that use of the confessions violated petitioner’s Sixth

Amendment right to counsel under the principle of Esco

bedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, and other decisions of this

Court.

A. The Decision Below Is in Plain Conflict With

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368

The decision below is a frontal attack on the funda

mental premise of this Court’s rulings from Cohens v.

Virginia, 6 Wheat. (19 U.S.) 264, through Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, to Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776,

that under the Supremacy Clause, “ the federal judiciary

is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution”

(Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. at 18). On June 22, 1964, this

Court decided Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, holding

that the Constitution forbids a state court procedure leav

ing the determination of the voluntariness of a confession

to the same jury which is charged with deciding simul

taneously the issue of guilt or innocence. The Court held

that such a procedure “did not afford a reliable determina

tion of the voluntariness of the confession offered in evi

dence at the trial, did not adequately protect . . . [the]

right to be free of a conviction based upon a coerced con

fession and therefore . . . [violated] the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” (378 U.S. at 377).

Notwithstanding that petitioner was tried and convicted

in October 1964, almost four months after Jackson v.

Denno, and that decision was brought to the attention of

the Georgia trial and appellate courts, Georgia has ad

hered to its settled practice in plain violation of Jackson

v. Denno. To be sure, the Georgia Supreme Court’s opinion

below makes a bow in the direction of the Supremacy

Clause (“Did we think that the Jackson case applied to

this case, we would unhesitatingly follow it despite our

firm conviction that it is illogical, impractical, and utterly

unsound” ; K. 337), and attempts to distinguish Jackson

v. Denno on grounds we shall examine below. But the

primary emphasis of the opinion is an open denunciation

of this Court’s decision and an express call for it to be

overruled.

The court below decried “the unusual implication of

Jackson” ; deplored the “ strange speculation as to how

jurors might violate their oaths . . . all of which was pure

imagination without a scintilla of fact or law to support

it” ; asserted it was based on “unfounded speculation” ;

said the “ decision is so shocking . . . every judge has a

duty to speak out loudly against it” ; and voiced dismay

over the “new and strange rule with no basis of law but

established by a majority of one of the Supreme Court”

16

(R. 339-41). Indeed, that court saw the Jackson case as

one “ shaking the foundations of orderly judicial trials

which can only be followed by chaos in the trial courts of

America” (R. 341), and expresses the hope that this Court

will “ after more mature consideration overrule Jackson

v. Denno” (E. 341). Such vehemence was not merely

academic exhortation. Repudiation of Jackson is the only

ground on which the procedures employed in petitioner’s

case could be sustained.

Nothing in the opinion below suggests that Georgia

procedure affords what Jackson v. Denno requires: a sys

tem for determining the voluntariness of a confession on

the facts and law prior to its submission to the jury which

decides the question of guilt or innocence. On the con

trary, consistent with prior Georgia precedents, the trial

court submitted the issue of voluntariness to the trial

jury for decision (see charge to jury at E. 312). The trial

jury was left to resolve the conflicting testimony about

whether physical brutality was used against petitioner by

Dr. Jackson in the presence of a group of police officers at

the same time it was considering the issue of guilt on all

the evidence, including the disputed confessions. The func

tion of the trial judge, under settled Georgia procedure,

was merely to determine whether the State made out a

prima facie case that a confession was voluntary. The

State can establish such a prima facie case under Georgia

law merely by its witness’s assertion during preliminary

examination that (in the words of Georgia Code §38-411)

a confession was “made voluntarily, without being induced

by another, by the slightest hope of benefit or remotest

fear of injury.” Bourns v. State, 208 Ga. 619, 621, 68 S.E.

2d 568, 569-70 (1952); Garrett v. State, 203 Ga. 756, 762-63,

48 S.E.2d 377, 382 (1948); Coker v. State, 199 Ga. 20, 23-25,

33 S.E.2d 171, 173-74 (1945); Bryant v. State, 191 Ga. 686,

17

710-11, 13 S.E.2d 820, 836-37 (1941). Once the state makes

this “prima facie” showing it is “ for the jury to decide

on conflicting evidence whether [a confession] . . . was

voluntary.” Doivns v. State, supra, 68 S.E.2d at 570. The

trial judge overruled Sims’ motion to suppress the con

fession without any explanation or elaboration of his rul

ing and without any indication that he had attempted to

resolve the conflicting testimony presented to him (R. 147).

It is significant that during the hearing, out of the pres

ence of the jury, Sims’ testimony that he was beaten and

pulled by the “privates” while in custody in Dr. Jackson’s

office was entirely unrebutted, Dr. Jackson’s partial de

nials coming only in testimony to the jury after the con

fessions ruled admissible.

All of the vices of the procedure which this Court thought

sufficient in Jackson to require it to overrule Stein v. New

York, 346 U.S. 156, are present here. The trial court’s

unexplained overruling of petitioner’s challenge to the

confessions in no way resolved the conflict between peti

tioner’s testimony that he was questioned by Sheriff Lee

and Sheriff Lee’s denials, nor did it determine whether

credence was to be given petitioner’s then undisputed testi

mony that he was beaten by Dr. Jackson in the presence

of armed peace officers. The trial court made no findings

concerning the weight to be given the testimony that peti

tioner was “ scolded” in the sheriff’s office (R. 139), or

the circumstances that the written statement contained

manufactured statements of voluntariness (R. 101, 103-

104). Similarly, it is impossible to know what the jury

decided on the question of voluntariness. Here, as in Jack-

son v. Denno (supra, 378 U.S. 379-80):

It is impossible to discover whether the jury found

the confession voluntary and relied upon it, or in

voluntary and supposedly ignored it. Nor is there any

18

indication of how the jury resolved disputes in the

evidence concerning the critical facts underlying the

coercion issue. Indeed, there is nothing to show that

these matters were resolved at all, one way or the

other.

Thus, the ruling below is at war with the requirement

that the “procedures must . . . be fully adequate to insure

a reliable and clear-cut determination of the voluntariness

of the confession, including the resolution of disputed facts

upon which the voluntariness issue may depend.” Jackson

v. Denno, 378 U.8. 368, 391.

The court below does not deny that Georgia practice

makes the trial jury the only trier of fact on the issue

of “ admissibility” when a confession is challenged as in

voluntary. It, rather, suggests three principal reasons,2

why it believes Jackson v. Denno is distinguishable from

this case (R. 337-338):

1) That the Jackson opinion did not consider Georgia

Code §38-420 “which provides that a confession can not

rest upon a confession alone, but the confession must

be corroborated” ;

2) that the Jackson opinion did not consider Georgia

Code §38-411 “requiring as an indispensable founda

tion to the introduction of an alleged confession a

showing that it was freely and voluntarily made and

that it was not induced by another by the slightest

fear of punishment nor the remotest hope of reward” ;

2 The court below also suggested that Jackson did not cover this ease

because "there was no evidence to make an issue of voluntariness” (R.

339). To the contrary, we shall submit at pp. 26 to 43, infra, that the

uncontradicted evidence establishes coercion as a. matter of law. However

this may be, the assertion that there was “ no evidence” o f coercion is

entirely untenable. See ibid.

19

3) that the Jackson- opinion did not consider “ Geor

gia law investing the trial judge with unquestionable

power to review the case after conviction, and to set

the verdict aside if he is not satisfied with it.”

The general answer to these attempted distinctions is

that none of the rules of Georgia law which are cited are

rules which are different from the New York law con

sidered in Jackson. Indeed, all three rules are principles

of such general applicability that there is no reason at all

to believe that this Court did not consider them or ever

thought any other principles applied when it decided

Jackson v. Denno, supra.

The Georgia Supreme Court’s first point—emphasizing

that confessions must be corroborated—is directly par

alleled in New York law. See N.Y. Code Crim. Proc., §395

requiring “additional proof” other than a confession be

fore conviction. The rule that confessions must be cor

roborated is, of course, universal in American law. See

7 Wigmore, Evidence §2071 (3d ed. 1940). It has been

stated frequently in this Court’s opinions in federal cases.

Opperv. United States, 348 U.S. 84; Smith v. United States,

348 U.S. 147; Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471,

488-489. One can hardly suppose that the Court forgot it

or did not know of it in deciding Jackson v. Denno, supra.

Of course, even if the Georgia rule on corroboration of

confessions was unique, it would not justify rejection of

Jackson v. Denno. The emphasis on the corroboration of

the confession is merely another way of urging that it is

reliable or truthful. But Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534,

makes it plain that the Constitution requires a determina

tion that a confession is voluntary and that the reliability

of the confession is not properly considered in determining

voluntariness.

20

The Georgia Court’s second point merely focuses on the

verbiage of Georgia Code §38-411 and is largely rhetoric.

Of course, Georgia law requires that a foundation be laid

for a confession. But so does New York’s law as this

Court observed in Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, 377-378,

and Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156. The Georgia rule is

like the New York rule described in Jackson v. Denno, 378

U.S. at 377-378:

Under the New York rule, the trial judge must make

a preliminary determination regarding a confession

offered by the prosecution and exclude it if in no cir

cumstances could the confession be deemed voluntary.

But if the evidence presents a fair question as to its

voluntariness, as where certain facts bearing on the

issue are in dispute or where reasonable men could

differ over the inferences to be drawn from undisputed

facts, the judge “must receive the confession and leave

to the jury, under proper instructions, the ultimate

determination of its voluntary character and also its

truthfulness.” Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156, 172,

97 L.ed. 1522, 1536, 73 S. Ct. 1077. If an issue of coer

cion is presented, the judge may not resolve conflicting

evidence or arrive at his independent appraisal of the

voluntariness of the confession, one way or the other.

These matters he must leave to the jury.

And the opinion below nowhere hints at a disavowal of the

line of prior Georgia decisions interpreting §38-411 to re

quire only a decision by the judge whether there was a

prima facie showing of voluntariness with all factual dis

putes being left to the jury. Downs v. State, 208 Ga. 619,

621, 68 S.E.2d 568, 569-570 (1952); Garrett v. State, 203 Ga.

756, 762-763, 48 S.E,2d 377, 382 (1948); Coker v. State, 199

Ga. 20, 23-25, 33 S.E.2d 171,173-174 (1945); Bryant v. State,

191 Ga. 686, 710-711, 13 S.E.2d 820, 836-837 (1941).

21

Thus, the court’s second point plainly begs the question

in its assertion that Georgia law requires that confessions

be voluntary. The question decided in Jackson v. Denno,

supra, is who must determine that confessions are volun

tary. Georgia has not shown that its procedure in this re

gard differs from that condemned in Jackson.

The Georgia court’s third point is that the trial judge

can grant a new trial if he is not satisfied with or does not

approve the verdict. Again, New York has the same rule,

and this Court was aware of it as indicated by Stein v.

New York, 346 U.S. 156, 174, footnote 18. This Court de

scribed the New York trial judge’s powers in Stein saying

that he can “ set aside a verdict if he thinks the evidence

does not warrant it,” citing N. Y. Code Grim. Proc. §465.

Indeed, in a New York capital case such as Jackson the

state Court of Appeals also has statutory power to order a

new trial “if the conviction is found to be ‘against the

weight of evidence,’ or if the court is satisfied for any

reason whatever ‘that justice requires a new trial’ ” (Stein

v. New York, 346 U.S. 156, 171-172). See People v. Caruso,

246 N.Y. 437, 159 N.E. 390 (1927). With respect to the

trial judge’s powers to order a new trial, the notion that a

trial judge may act as a “ thirteenth juror” is general in

our law and not at all peculiar to Georgia. See, for example,

Brodie v. United States, 295 F,2d 157, 160 (D.C. Cir. 1961);

Davis v. State, 245 Ala. 589, 18 So.2d 282 (1944); People v.

Megladdery, 40 Cal. App. 748,106 P.2d 84 (1940); Common

wealth v. Coyle, 190 Pa. Super. 509, 154 A.2d 412 (1959);

24 C.J.S., Criminal Law, §1452 (1961); Barron & Holtzoff,

Federal Practice & Procedure, §2281 (Rules ed. 1958).

We submit that the Court should reject the invitation in

the opinion below (R. 341) to overrule Jackson v. Denno,

and should reaffirm that the decisions of the nation’s highest

Court interpreting the Constitution are as binding in

22

Georgia as they are in the other States. There is no reason

why Georgia cannot conform to Jackson, as the other States

have done.3 The State’s brief in opposition to certiorari in

this case has understandably made no argument on the

Jackson v. Denno question.

B. The Standards Applied Below to Determine

Voluntariness Were Insufficient to Satisfy the

Constiluional Requirements

In his Amended Motion for New Trial petitioner set

forth constitutional objections to the charge to the jury

on the issue of voluntariness (R. 43-44). The charge on

this issue (R. 312) did little more than reiterate the lan

guage of Ga. Code §38-411 that confessions must be vol

untary “without being induced by another, by the slightest

hope of benefit or remotest fear of injury.” The motion

asserted that the charge violated constitutional require

ments in that it was “wholly inadequate to have insured

a reliable and precise determination of the voluntariness

of the alleged confession” and that the “ instructions leave

it entirely to the impressionistic determination of the jury

whether a voluntary confession was in point of fact made

without delineating any constitutionally adequate standards

or definitive criteria upon which and by which the jury

could resolve said issue” (R. 43-44).

Whatever was the scope of the trial judge’s function

in appraising the issue (we have submitted in part A above

3 The following jurisdictions have altered their rules to conform to

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368: State v. Costello, 97 Ariz. 220, 399 P.2d

119 (1965); People v. Walker, 374 Mich. 331, 132 N.W.2d 87 (1965) ;

State v. Brewton, 395 P.2d 874 (Ore. 1964); Commonwealth ex rel. Gaito

V. Maroney, 416 Pa. 199, 204 A.2d 758 (1964) ; Lopez v. State, 384 S.W.2d

345 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1964), on remand from 378 U.S. 567; State v.

Burke, 27 Wis. 244, 133 N.W.2d 753 (1965).

State law grounds barred consideration of Jackson on its merits in

State v. Taylor, 133 N.W.2d 828 (Minn. 1965) ; Marion v. State, 387 S.W.

2d 56 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1964).

23

that he did not resolve any disputed facts), it seems ap

parent that he did not use any different standard than

the one he gave the jury. This is clear not only from the

jury instruction but from the manner in which the Court

repeatedly treated objections to the confessions, permitting

them to go before the jury on nothing more than conelusory

affirmative answers by police witnesses to questions phrased

in the words of the statute (R. 211, 224-225).

Finally, the Georgia Supreme Court seems to have taken

the same narrow view of the test for vountariness. Its

opinion gives little evidence of an examination of the to

tality of the circumstances surrounding the confession.

There is, for example, no mention of the physical brutality

to which Sims was subjected while in custody during the

investigation process. This is described in detail, infra at

pp. 26 to 30. Nor was there any discussion of the many

other factors such as Sims’ mental condition, injuries,

education, isolation, etc., which are delineated below at

pp. 30 to 36. Eather, the court below apparently found it

sufficient to resolve the issue that there was testimony

that petitioner was advised of certain rights; that the

Sheriff testified “ that no threats or promise of hope or

benefit or reward were made to induce Sims to make a

statement” (R. 335); that there was thus, a “prima facie

showing that the statement was freely and voluntarily made

and admissible in evidence. Code §38-411” (R. 336); and

that “ even without this confession, the above-mentioned

evidence w7as sufficient to support the verdict” (R. 334).

It is, we submit, clear that petitioner never had a deci

sion of the issue of voluntariness made with reference to

the appropriate constitutional standards at any level—•

neither by the trial judge, jury, or state appellate court.

His conviction should be reversed on the authority of

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 IJ.S. 534.

24

In Rogers, supra, the Court invalidated a conviction rest

ing on a confession which the trial judge and the State’s

highest court had approved, since it was plain they both

“ failed to apply the standard demanded by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for determining the

admissibility of a confession” (365 U.S. at 540). The error

of the Connecticut courts was in determining admissibility

“by reference to a legal standard which took into account

the circumstance of probable truth or falsity” (365 U.S.

at 543).

In Isaac Sims’ ease, it is apparent that the State’s high

est court made the same error. It relied on the fact that

there was other evidence corroborating the confession in

considering its -admissibility. Whether the other evidence

of guilt was thought pertinent as assuring the confession’s

truth or as warranting its non-prejudicial character, this

simply is not Fourteenth Amendment law. See Payne v.

Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560, and authorities cited.

The Supreme Court of Georgia, moreover (and the trial

court insofar as its basis of judgment can be gleaned from

this record), appraised the case only in terms of the pres

ence or absence of threats or promises—the Georgia statu

tory standard. Similarly, the skeletal instructions to the

jurors in the words of the statute directed the jury’s atten

tion to “hope . . . or . . . fear” and wholly failed to equip

the jurors to determine voluntariness in accord with federal

constitutional standards requiring scrutiny of all the co

ercive or overbearing circumstances of the ease.

This Court long ago condemned as unduly restrictive a

review of confessions that was limited to determining

whether they were induced by promises or threats. Mr.

Justice Brandeis wrote in Wan v. United States, 266 U.S.

1, 14-15:

25

The court of appeals appears to have held the prison

er’s statements admissible on the ground that a con

fession made by one competent to act is to be deemed

voluntary, as a matter of law, if it was not induced by

a promise or a threat; and that here there was evi

dence sufficient to justify a finding of fact that these

statements were not so induced. In the Federal courts,

the requisite of voluntariness is not satisfied by estab

lishing merely that the confession was not induced by

a promise or a threat. A confession is voluntary in

law if, and only if, it was, in fact, voluntarily made.

A confession may have been given voluntarily, al

though it was made to police officers, while in custody,

and in answer to an examination conducted by them.

But a confession obtained by compulsion must be ex

cluded, whatever may have been the character of the

compulsion, and whether the compulsion was applied

in a judicial proceeding or otherwise. Bram v. United

States, 168 U.S. 532.

And at least since Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227,

239, the rule of Wan has been the law of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See also Ward v. Texas, 316 U.S. 547, 555;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143, 154.

Petitioner has not had a determination of voluntariness

in the courts below which is consistent with the constitu

tional standards. Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534; Wan

v. United States, 266 U.S. 1; cf. Haynes v. Washington, 373

U.S. 503, 516-517, note 11.

26

C. Petitioner’s Confession Was Obtained in Inherently

Coercive Circumstances and After He Had Been Phys

ically Brutalized While in Custody, and Its Use to

Convict Him Violates the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment

1. Facts and Circumstances Surrounding the Confession

Isaac Sims was taken into custody by Sgt. George

Sims and Trooper Peacock of the State Patrol at about

3:00 p.m. on April 13, 1963 (R. 184-185). On orders

from Sheriff Sikes, petitioner was taken by Sgt. Sims to

the medical office of Dr. Joseph M. Jackson (R. 185).

He was taken directly to Dr. Jackson’s office from the

place where the police took him in custody (R. 184-185).

It is clear that the officers took Sims to Dr. Jackson’s

office as a part of their investigative process, so that his

clothes might be removed and examined for evidence of

the crime (R. 205, 206-207).

Petitioner Sims testified very clearly that he was brutal

ized while in custody at Dr. Jackson’s office. He gave

such testimony both in the pre-trial hearing outside the

presence of the jury (R. 131), and in his unsworn state

ment, before the jury (R. 248). Sims stated that he was

in Dr. Jackson’s office with seven or eight white state

patrolmen. When asked what happened to him there,

Sims said (R. 131):

Well, Dr. Jackson, he knocked me down and kicked

me over my eye lid and busted my eye on the right

side.

Q. Did anything else happen to you? A. And he

grabbed me by my private and drug me on the floor.

Sims’ statement before the jury was to the same effect

(R. 248):

27

Well, they brought me over to Dr. Jackson’s office

and they carried me in there, about six or seven

State Patrols, and Dr. Jackson beat me, and taken

my clothes off, and then carried me over to the bigger

hospital and stitched my eye up where they kicked

me over the eye, and put me on some white clothes

•—white pants, but I kept my shirt I had on.

Q. While you were in Dr. Jackson’s office did he

drag you around the floor? A. Yes, sir.

# # * # #

Q. (By the Defendant’s Attorney) What happened

to you while you were in Dr. Jackson’s office? A.

Well, he pulled me by the privates.

When Sims testified in the pre-trial hearing he was

cross-examined, but the prosecutor never asked Sims a

single question about what happened to him in Dr. Jack

son’s office (E. 137-143). In addition, the prosecutor put

on no testimony at all to rebut Sims’ claim that he was

beaten, kicked over the eye, and pulled by his private

parts in the presence of six to eight officers.

The prosecutor never asked any witness a single ques

tion about what happened in Dr. Jackson’s office. Sgt.

George Sims, the officer who took petitioner to and from

Dr. Jackson’s office (R. 185), was never asked what hap

pened in the office.4 * The other officers who were present

were never called to testify or identified by name.6 The

prosecutor did not ask Dr. Jackson a single question (on

direct or re-direct) about what happened while Sims was

in his office (R. 189-197, 208).

4 Dr. Jackson said that he presumed that the officers in the office with

Sims were the ones who brought him there (R. 202).

6 The exception was Trooper Peacock who was mentioned by Sgt. Sims

(R. 184) but did not testify.

28

Defense counsel did cross-examine Dr. Jackson about

the events in his office (R. 202-207). Certain aspects of

Sims’ testimony were confirmed by Dr. Jackson, who said:

(a) that Sims was brought to his office (R. 202);

(b) that police officers and troopers were there and he

was not alone with the defendant (R. 202);

(c) that Sims’ clothes were removed (R. 202) ;

(d) that he (Dr. Jackson) “ assisted him slightly” and

gave him “a little help” in removing his clothes, including

his pants and his underpants (R. 202-203, 206-207);

(e) that Sims was down on the floor while in the office

(R. 203, 204);

(f) that by the time Sims left the office he “had a place

over his eye that required some treatment” (R. 204) ;6

(g) that when Sims left “he was taken over to the

hospital and the place was treated that I told you about”

(R. 207);

(h) that at the hospital Dr. Aztui put four stitches in

the injury over Sims’ eye (R. 207).

Dr. Jackson’s explanation of what happened to peti

tioner in his office was highly evasive and partly in the

form of denials of knowledge about what happened to

Sims. Asked whether the State Patrolman “put the place

over his eye,” Jackson answered, “ I don’t know who put

it there” (R. 204). When asked if the officers were beating

Sims he said:

A. You’ll have to ask the officers.

Q. I ’m asking you, Dr. Jackson. I ’m asking you

6 A state investigator observed the injury on his face two days later

(R. 242).

29

whether or not the officers were beating the defendant.

A. I will say that I wasn’t there all the time (E. 204).

Referring to the “place” over Sims’ eye, Jackson was

asked:

Q. He didn’t have it over his eye when he came

into yonr office, did he? A. I didn’t see him till after

he got in.

Q. And when you first saw him in your office he

didn’t have it? A. I couldn’t see it. He was sort of

slumped over, sort of falling around, like. Most any

thing could have happened to him (E. 204).

Hr. Jackson denied that he knocked Sims down (R.

204) or that he kicked him (R. 205). But when asked

whether Sims wras kicked he said only: “I don’t know

that he was” (R. 205). Earlier, Dr. Jackson was asked

whether Sims was knocked down and he said: “I don’t

know whether he was knocked down or fell down” (R.

203).

Dr. Jackson was asked:

Q. Did you find him down on the floor? A. He

sort of fell in the floor.

Q. He just sort of fell? Where were you standing

at the time he sort of fell? A. I was standing on my

feet.

Q. Were you standing near him? A. Fairly close.

Q. Were you standing as close as I am to you, or

closer? A. Probably a little closer.

Q. Where you could touch him? A. I think he

could touch me.

Q. And you could touch him? Right? A. Yes. (R.

204).

30

Thus, Dr. Jackson’s testimony was that Sims was close

enough to touch him when he fell on the floor, but Dr.

Jackson did not know “whether he was knocked down or

fell down” (R. 203). Later Jackson said Sims was on the

floor when he entered the room (R. 205). In Jackson’s

own words, “ Most anything could have happened to him”

(R. 204). Despite all this, throughout the entire trial the

prosecutor avoided any inquiry into what happened to

Sims in Dr. Jackson’s office. Although Dr. Jackson denied

on cross that he knocked Sims down or kicked him, the

prosecution asked no questions about this and called none

of the policemen to corroborate the doctor’s denial. Plainly

Sims was injured while in custody. There was no sug

gestion that he resisted arrest or anything of that nature.

Moreover, the doctor gave no testimony denying Sims’

claim that he was pulled by his private parts and dragged

on the floor. There was no rebuttal or denial of this

testimony at all and it stands uncontradicted and uncon

tested in the record. The language of the Court in Haynes

v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503, is pertinent in appraising

the State’s failure to rebut Sims’ claim of brutality:

We cannot but attribute significance to the failure of

the State, after listening to the petitioner’s direct

and explicit testimony, to attempt to contradict that

crucial evidence; this testimonial void is the more

meaningful in light of the availability and willing

cooperation of the policemen who, if honestly able

to do so, could have readily denied the defendant’s

claims. (373 U.S. at 510.)

In addition to the evidence of physical brutality, there

are, of course, a variety of other facts to be considered in

appraising the totality of circumstances surrounding the

confessions. They reveal that Sims was bewildered, help

31

less, alone, hungry, in pain and in fear when he signed

his written statement.

Isaac Sims is an indigent, ignorant, illiterate Negro, who

cannot read and can write only his name (R. 130). He has

spent most of his life in Charlton County in the southeast

part of Georgia (R. 129). Both of his parents are dead;

his closest relatives in Charlton County were two sisters

(R. 128). At the time of his arrest he was in his twenties;

the record leaves his exact age unclear.7 Sims was unable

to tell what year he was born (R. 128). He went to the third

grade in school, quitting* when he was “ seventeen or eigh

teen” (R. 130). He testified, “Well, I didn’t go [to school]

too much on account of I had to help my father work, and

he taken me out of school” (R. 129). He worked as a pulp-

wood worker, earning forty to sixty dollars a week. He

is indig-ent, had appointed counsel at his first trial, and

has proceeded in forma pauperis throughout the case.

The record reveals his limited mental capacity in many

instances. He did not know the year he was born; nor could

he state when Iris father died (R. 128). He was totally un

able to explain words and phrases such as “normal and

ordinary” (R. 144), “ legal rights” (R. 136), “ constitutional

rights” (R. 137), “ freely and voluntarily” (R. 136), “ the

right to have a lawyer” (R. 137), or that “a statement can

be used against you in court” (R. 136). Sims “ stutters”

when he speaks (R. 122).

Sims was a Negro charged with the rape of a white

woman-—a capital felony in Georgia. The prosecutrix was

the unmarried daughter of the local postmaster (R. 61).

At about 2 :00 or 2 :30 p.m. Sims was taken into custody and

held at gunpoint some five miles from the scene of the

7 The confession stated that he was 27 on the day of arrest in April

1963 (R. 226) ; he testified that he was 29 at the trial in October 1964

(R. 247), but his birthdate was February 5 (R. 128).

32

crime by two Negro men who had been ordered by their

boss, a local white man, to look for any “ stray man” (R. 169,

175-176). He was then taken by this white man, Noah

Stokes, accompanied by several other men, to state troopers

who carried him to Dr. Jackson’s office where Sims was

brutalized as we have described above. After Sims was

treated at the hospital for his eye injury, the police took

him to the Ware County Jail in Waycross, some thirty or

thirty-five miles away from Folkston and located outside

the county where the crime occurred, for “ safe keeping”

(R. 233-231, 242).

The police testimony is that at about 6 :30 p.m., while con

fined in a cell at the Ware County Jail, Sims orally admitted

“ raping” or “molesting” a white woman in Folkston in a

conversation with Deputy Sheriff Dudley Jones whom Sims

had known for more than a dozen years previously8 (R. 113,

209-210, 214-216). Jones did not testify that he gave Sims

any warnings prior to eliciting this admission, either as to

Sims’ right to remain silent, that his statement would be

used against him, or as to his right to counsel. Jones testi

fied that Sims then agreed when asked if he wanted to make

a statement to the sheriff (R. 113, 210).9

Sims remained alone in a cell until about 10:00 or 10:30

that evening when he was taken to the “interview room”

in the jail (R. 210, 223). Sims had not been fed since he

was taken into custody some 8 hours earlier and he was

still in pain from the injury sustained in Dr. Jackson’s

office.10 There were four white officers in the “ interview

8 Sims denied making- this oral confession (R. 134, 138-139).

9 Sims also denied this (R. 133).

10 Sims testified at R. 135-136:

A. Well, I felt pretty rough for about two or three weeks, more on

my private than I did on my face.

Q. When you said you felt pretty rough, what did you mean, Isaac?

A. Well, I was paining a right smart.

33

room” with Sims: they were the Sheriff and Deputy Sheriff

of Ware County, the Chief of Police, and the Constable.11

Sims testified that he was “ scared” (R. 143). As to his

treatment, he said, “ they didn’t beat me, but they kind of

scolded me a little” (R. 139). None of Sims’ testimony in

these regards was rebutted.

Since his arrest, petitioner had not been in touch with

any relative, friend or attorney. He had not been offered

the use of a phone (R. 222) and he had not been taken be

fore a magistrate in accordance with Georgia law (R. 235-

236).12 He was in jail in the adjoining county some 30 or

35 miles from Folkston (R. 67, 242).

Q. Were you paining a right smart when you were in the room

with Sheriff Lee and Deputy Sheriff Jones? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, after you were taken into custody up until the time you

were taken upstairs had you been given anything to eat? A. No, sir.

Q. Were you hungry? A. Yes, sir; I could have eat.

11 The Police Chief and Constable were not called as witnesses.

12 Georgia law specifically required bringing petitioner promptly before

a magistrate where, as here, the arrest was made without a warrant:

“Duty of person arresting without warrant.—In every case of an

arrest without a warrant the person arresting shall without delay

convey the offender before the most convenient officer authorized to

receive an affidavit and issue a warrant. No such imprisonment shall

be legal beyond a reasonable time allowed for this purpose and any

person who is not conveyed before such officer within 48 hours shall

be released.” Ga. Code §27-212 (1933).

Even if the arresting officers had a warrant, they were similarly obli

gated :

“ Officer may make arrest in any county. Duty to carry prisoner to

county in which offense committed.— An arresting officer may arrest

any person charged with crime, under a warrant issued by a judicial

officer, in any county, without regard to the residence of said arrest

ing officer; and it is his duty to carry the accused, with the warrant

under which he was arrested, to the county in which the offense is

alleged to have been committed, for examination before any judicial

officer of that county.

“ The county where the alleged offense is committed shall pay the

expenses of the arresting officer in carrying the prisoner to that

county; and the officer may hold or imprison the defendant long

enough to enable him to get ready to carry the prisoner off. (Acts

1865-6, pp. 38, 39; 1895, p. 34.)” Ga. Code §27-209 (1933).

34

The record does not make it clear how long Sims was in

the interview room before the confession was given and

signed,13 or to what extent, if any, Sims was interrogated.

When asked whether he questioned Sims, Sheriff Lee said,

“ I don’t think so,” then, “I could have,” and finally, “I just

don’t recall right now” (R. 105). Sims said he was ques

tioned by Lee (R. 135, 140), and also that he was “ scolded”