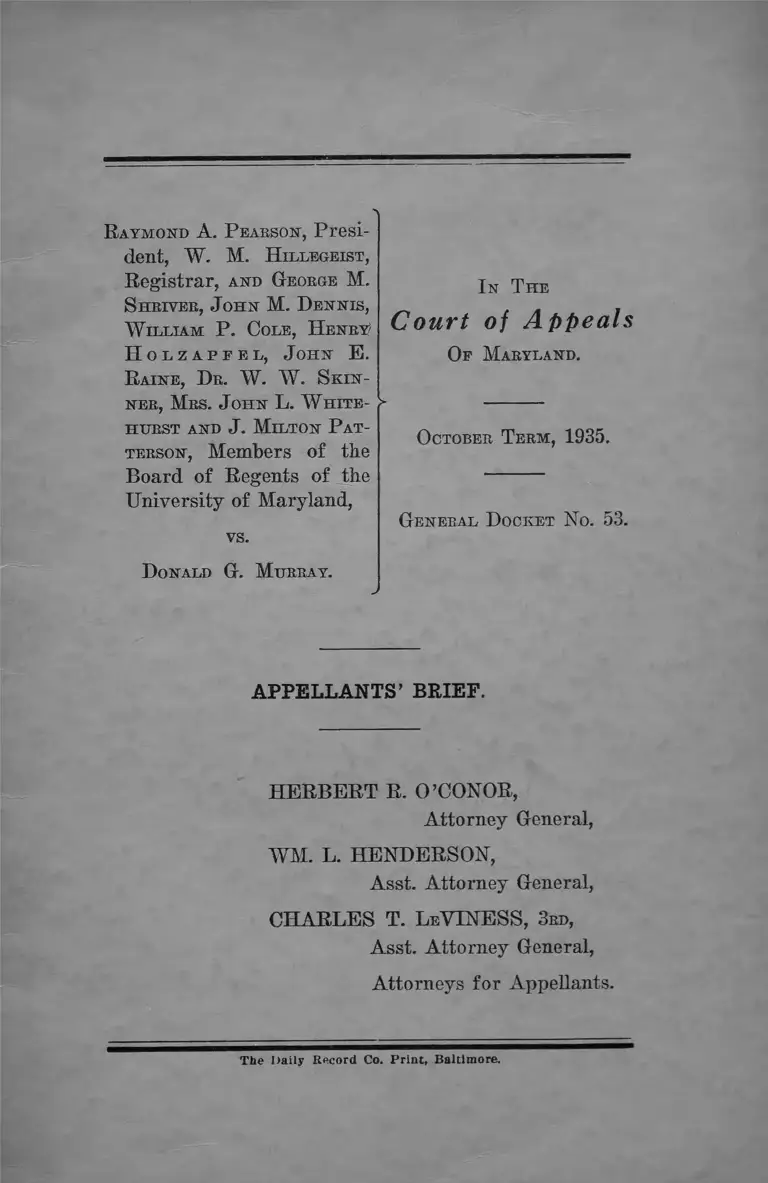

Pearson v. Murray Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1935

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pearson v. Murray Appellants' Brief, 1935. 40e24cef-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/180098db-1e2e-4b6e-90c4-591f713319b2/pearson-v-murray-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

R aymond A . P earson, Presi

dent, W. M. H illegeist,

Registrar, and G eorge M.

S hriver, J ohn M . D en n is ,

W illiam P . C ole, H enry

H o l z a p f e l , J ohn E.

R aine , D e . W. W. S k in

ner, M es. J ohn L. W h ite - >-

HURST AND J . MlLTON P aT-

teeson, Members of the

Board of Regents of the

University of Maryland,

vs.

D onald G. M urray.

I n T he

Court of Appeals

O f M aryland .

O ctober T erm , 1935.

G eneral D ocket No. 53.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF.

HERBERT R. O ’CONOR,

Attorney General,

WM. L. HENDERSON,

Asst. Attorney General,

CHARLES T. LeYINESS, 3rd,

Asst. Attorney General,

Attorneys for Appellants.

The Daily Record Co. Print, Baltimore.

R aymond A. P earson, Presi

dent, W . M. H illegeist,

Registrar, and G eorge M.

S hriver, J ohn M. D en n is ,

W illiam P . Cole, H enry

H o l z a p e e l , J ohn E.

R aine , D r . W . W . S k in

ner, M rs. J ohn L. W h ite

hurst and J . M ilton P at

terson, Members of the

Board of Regents of the

University of Maryland,

vs.

D onald G. M urray.

I n T he

Court of Appeals

Op M aryland .

O ctober T erm , 1935.

General D ocket N o. 53.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF.

STATEM EN T OF TH E CASE.

This is an appeal from the Baltimore City Court in

which the appellee (petitioner below), who is a colored

man, sued for a writ of mandamus to require the defend

ants, the Regents of the University of Maryland, to admit

him as a student in the law school of the University. The

lower court granted the writ.

2

QUESTION ON A PP E A L AND A PPELLAN TS’

CONCLUSIONS THEREON.

Are the defendants compellable in mandamus to admit

a negro to the law school? The lower court ruled they

were so compellable.

The defendants contend that the trial court erred, for

the following reasons:

I.

M ANDAM US IS NOT THE PROPER REM EDY IN THIS CASE.

1. Petitioner Has No Right to Sue in Mandamus to Com pel the

University Officials to Adm it Him. His Rem edy, If A ny, Is by A p

propriate A ction to Require the Proper State Officials to Supply a

Law School for Negroes.

II.

TH E EXCLUSION OF THE APPELLEE DOES NOT V IO L A T E HIS

CO N STITU TION AL RIGH TS.

1. Since education is exclusively a State matter, he has no right

to admission m erely because he is a citizen o f the United States.

2. The equal protection o f the laws does not prevent classifica

tion on the basis o f race.

III.

TH E L A W SCH OOL OF TH E U N IVER SITY OF M ARYLAN D IS

NOT AM ENABLE T O C O N STITU TION AL

LIM ITATION S.

1. The University o f Maryland Is in the Nature o f a Private

Corporation.

2. Private Institutions M ay Select Their Students Arbitrarily,

W ithout Regard to the Fourteenth Am endm ent.

3. The Law School o f the University Derives Its M aintenance

Principally From Tuition Charges to Students.

3

EVEN IF TH E L A W SCH OOL IS A PUBLIC IN STITU TION AM EN

ABLE T O TH E FOURTEENTH AM ENDM ENT, IT IS NOT

REQUIRED T O A D M IT NEGROES BECAUSE TH E ST A TE

PROVIDES SCHOLARSHIPS FOR THEIR

EXCLUSIVE USE.

X. The Policy o f This State Is to Separate the Races.

(a) In railway coaches

(b) In private and public educational institutions, at

scholastic, collegiate and professional levels.

2. Separation o f the Races in Educational Institutions Has Been

Upheld by the Highest Authority.

3. This State A ffords Its Colored Citizens Substantially Equal

Facilities fo r Public Education.

(a) It has a dual and practically identical system of

secondary education for the two races.

(b) It affords substantially equal opportunities at col

legiate levels: at Princess Anne Academy, at Mor

gan College, and by scholarships.

(c) At professional levels it affords no colored schools

because heretofore there has been no sufficient de

mand therefor; but the scholarship system offers

its negro citizens opportunities and advantages

substantially equal to those given its white citizens.

STATEM EN T OF TH E FACTS.

The petitioner is a Negro (E. 23); he is twenty-two

years old; has lived in Baltimore all his life; has attend

ed colored Public School No. 103, on Division Street,

Douglas High School and Amherst College, Amherst,

Massachusetts (E. 45). He intends to practice law in the

IV.

4

City of Baltimore and desires to enter the Law School of

the University of Maryland, because it is convenient and

less expensive for him, and because he would be able to

observe the Maryland courts and become acquainted with

other practitioners. Also he is a citizen of this State

and thinks he “ should have a right to go there” (R. 45).

In December, 1934, he addressed a letter to the Dean

of the Law School in which he stated that he was a grad

uate of Amherst College of the Class of 1934 and de

sired to secure admittance to the school. He also stated

he could secure necessary high school records from

Douglas High School “ the only Negro High School in

this City” (R. 29). He received a reply from Defendant

Pearson, the President of the University, in which he

was referred to Princess Anne Academy which is main

tained as a separate institution of higher learning for

the education of Negroes (R. 30). Later his applica

tion form and $2.00 money order for an entrance fee

were returned to him (R. 32).

In March, 1935, petitioner addressed a letter to the

Board of Regents of the University of Maryland. He as

serted he was a citizen of the State and fully qualified

to become a student of the University of Maryland Law

School. He stated that there is no other State institu

tion which offers a legal education. He said that the

arbitrary action of the. officials of the University of

Maryland in returning his application was unjust and

unreasonable and contrary to the Constitution of the

United States and the Constitution and laws of this

State. He appealed to the Regents to accept his appli

cation and, finding him qualified, to admit him to the

school (R. 32). In reply to this letter he received an

other communication from President Pearson in which

5

lie was referred to the exceptional facilities open to him

for the study of law at Howard University, in Washing

ton. President Pearson pointed out that Howard Law

School was rated as “ Class A ” and was fully approved

by the American Bar Association and is a member of

the Association of American Law Schools. The Presi

dent further stated that the tuition at Howard Law

School was $135.00 per year, in contrast to $203.00 per

year in the day school and $153.00 per year in the night

school of the University of Maryland Law School (B.

34).

On April 18, 1935, petitioner filed in the Baltimore

City Court his petition for a writ of mandamus, requir

ing the Board of Begents to accept his application and,

upon finding him qualified, to admit him in the regular

manner as a first-year student in the day school of the

University of Maryland School of Law for the academic

year 1935-1936. In his petition he asserted that the Uni

versity of Maryland is an administrative department of

the State and performs as essential governmental func

tion, supported and maintained principally by funds

from the General Treasury of the State. He further

pointed out that the charter of the University provides

that it shall be founded and maintained “ upon the

most liberal plan, for the benefit of students of

every country and every foreign denomination, who

shall be freely admitted to equal privileges and

advantages of education, and to all the honors of the

University, according to their merit, without requiring

or enforcing any religious or civil test, upon any parti

cular plan of religious worship or service” (B. 4). He

further asserted that the action of the Begents in refus

ing him admittance violated the Fourteenth Amendment

6

of the United States Constitution in that it denied him

the equal protection of the laws and deprived him of

liberty and property without due process of law (R.

7, 8).

In their answer the Regents pointed out that the Bal

timore Schools of the University of Maryland, of which

the Law School is a part, do not derive their mainten

ance funds principally from the General Treasury of the

State, but are supported principally by tuition fees paid

by students in said schools (R. 17).

The Regents further pointed out that this State has

provided separate institutions of learning for the ex

clusive use of colored persons, listing the acts of the

Legislature setting up their separate system (R. 19) ;

also they called attention to the scholarship statutes

provided by the General Assembly at its 1933 and 1935

regular sessions which were open to the petitioner as a

substitute for legal education in this State; and that un

der the 1935 Scholarship Act a commission on Higher

Education of Negroes was established to administer the

sum of $10,000 for scholarships to Negroes to attend col

lege out of the State, expressly providing that the schol

arships are for “ college, medical, law or other profes

sional courses * * # for the colored youth of the State

who do not have facilities in the State for such courses”

(R. 20).

However, petitioner did not desire one of these schol-

orships (R. 48) and took no action to obtain one (R. 50).

Up to June 18th, 1935 (the time of the trial below)

three hundred and eighty (380) colored persons had ob

tained application blanks, and one hundred and thirteen

7

(113) had returned these forms properly tilled out, for

scholarships under this Act (E. 109).

Under the plan worked out for the issue of these schol

arships it was decided by the Commission to award schol

arships both to undergraduate students and to graduate

or professional students. About one-half of the scholar

ships would go to undergraduates and one-half to grad

uates (E. 112-113). Of the number of application blanks

requested three hundred and sixty four (364) were for

undergraduate work and sixteen were for graduate

work. Of these sixteen only one applied for law study

(E. 109-110). Petitioner would have been eligible for one

of these scholarships if he had applied (E. 113). The

scholarships are to cover tuition only and, dividing the

$10,000 per year equally between graduate study and

undergraduate study, it may be possible to give more

than twenty-five scholarships for each group (E. 112);

no one applicant may receive more than $200.00 under

one of these scholarships (E. 113).

If petitioner had applied for a scholarship for How

ard University, in Washington, he would be able to com

mute daily from his home in Baltimore, but he “ wouldn’t

want to ’ ’. He can get from Baltimore to Washington

in one hour (E. 49). He stated that if he attends Mary

land Law School he will not have to pay for his room

and board, whereas if he attended school in Washing

ton and did not commute, he would have to pay for his

room and board (E. 50).

Operating under statutory direction (Code, Article

77, Section 200, et seq.) this State has established a dual

system of public education, one administered for its

white and one administered for its colored citizens. The

8

two systems offer approximately equal, and in most

cases identical, opportunities for learning.

In the counties of the State there are twenty-eight

colored high schools and five hundred and ten colored

elementary schools, all of which compare “ very favor

ably ’ ’ with the schools operated for white children. The

courses offered students in each are identical and the

curriculum offered in the small colored high school is the

same as in the small white high school (R. 88). Mary

land requires sixteen units of high school work for grad

uation and even the small colored high schools offer the

full sixteen units; their graduates are admitted into such

colleges as Morgan, in the State, and such universities as

Howard and Lincoln out of the State (R. 88).

Ninety-eight per cent of the teachers in the colored

elementary schools hold a first grade certificate, which

is the same percentage as the white teachers in the white

elementary schools (R. 89).

As to the distribution of these colored schools through

out the State they are found in every county except

Garrett, where the population is sparse. In a county

like Prince George’s where the colored population is

densest, there are forty-four colored schools in the coun

ty and seventy elementary teachers. No colored child

'is required to go more than one and a half miies to reach

a school; and, on the average, colored children in the

State live about three-fourths of a mile from a colored

school house (R. 90).

In the majority of the counties of the State the school

term for colored and white children is identical (R. 91);

in certain counties on the Eastern Shore where there is

9

trucking, colored schools run eight months instead of

nine. This is because of the strawberry season, the

colored children being needed by their parents to pick

strawberries (R. 90). In these schools which are open

only eight months a year, the same subjects are taught

as in the full-term schools, and upon completion the stu

dent receives the same number of credits and is as well

prepared to go to college as the full-term students

(R. 91).

As to the question of school attendance, the State

provides one attendance officer for each county. How

ever, the attendance records show a result “ slightly less

for Negroes than White, not very much less” (R. 92).

In regard to school transportation there are more

white children transported to school than colored chil

dren, but there is a gradual increase in the number of

colored children transported and for the scholastic year

1935-1936, about ten one-room schools will be closed and

the colored children will be transported to other schools

(R. 92). A school for colored children is opened in any

community where it seems there are sufficient number

of children to run a school and employ a teacher. In

some cases in this State schools are operated for as few

as seven colored children (Anne Arundel County); one

school in Dorchester County is operated for fewer than

ten children (R. 93).

Colored and white teachers do not receive the same

salaries, but this does not “ interfere with the equality

of education” . A Negro teacher having the same quali

fications as a white teacher “ would not slight the mem

bers of his own group because he was not paid as much

as the white teacher (R. 99).

10

County education for Negroes, all in all, is substan

tially equal to the education for whites. There are some

items where it is not (R. 93).

In Baltimore City the Douglas High School for Ne

groes is reputed to be as good as any white school in the

City (R. 101).

At college levels there are available for Negroes in

this State teachers training schools set up by the Pub

lic Education Law (R. 19); Morgan College, a private

institution in Baltimore City for Negroes, and Princess

Anne Academy, which is the Eastern Branch of the Uni

versity of Maryland. Morgan College receives a sub

stantial money grant from the State of Maryland and is

exclusively a Negro liberal arts college. The present

student body comprises about six hundred Negroes. For

the scholastic year 1934-1935, the State appropriated the

sum of $23,000 thereto, and for the scholastic year 1935-

1936, it has appropriated the sum of $35,000 (R. 105,

106). It is a co-educational college specializing in liberal

arts and courses in education, particularly for high

school teachers. It awards degrees of Bachelor of Arts,

Bachelor of Science and Education, Bachelor of Science

and Home Economics. It does not maintain a law school

or any other professional school (R. 104).

To Princess Anne Academy the State appropriated

for the scholastic year 1934-1935 the sum of $15,000.

There are about thirty-three colored students there who

therefore cost the State approximately $468.00 each.

Compared to the appropriation for white students at the

University of Maryland and its several schools, the col

ored student at Princess Anne receives from the State

almost three times as much. The appropriation for the

11

University of Maryland, college department, for the

scholastic year 1934-1935 was $230,000 for fifteen hun

dred students, about $153.00 per student; for the entire

University, including the college department and the

professional schools, the appropriation was $318,000.00

for thirty-six hundred students, or about $88.00 per year

per student (R. 67, 83). These figures do not include the

appropriation to the University of Maryland Hospital

(R. 82-83).

The appropriation for the present year is between

$30,000 and $40,000 less than for the scholastic year

1934-1935 (R. 84).

The Princess Anne Academy seven or eight years ago

was “ just a school for Negro children, some of them

were in the lower grader some in the high school” (R.

72). During the last few years the lower grades and

high school grades have been abandoned, and it is now

operated as a Junior College (R. 51, 72). The rating as

a Junior College is obtained by students who finish at

Princess Anne Academy and enter other colleges, where

they are given credit for two years of college work and

are accredited as juniors, or third year students (R. 51).

Graduates from Princess Anne Academy enter the third

year of Morgan College, Virginia State College at

Petersburg, or Hampton Institute in Virginia (R. 74,

75). Although there are but approximately thirty-three

students at Princess Anne Academy, the school is

equipped to take care of more than one hundred stu

dents. The dormitories for men and women can accomo

date as many as one hundred and seventy-five persons

and the same number can be handled in the class-room.

Class-room facilities are almost unlimited (R. 74). The

Princess Anne Academy offers a training especially de

12

signed to prepare colored boys for country life. For

this reason the school is not better attended, according

to President Pearson, because “ the importance and at

tractiveness and value of that type of education is not

well understood by the leaders in the negro race. ’ ’ By

that he meant farming and home economics (R. 75-76).

Also the Academy is not as attractive as the older in

stitutions with more years behind them and more money

to spend, according to Dr. Pearson (R. 76). In addition

to the facilities at Princess Anne Academy there has

been made available money for scholarships for students

to go elsewhere and finish their college education, the

amount of the scholarship granted to any one student

depending upon the difference between the cost of tui

tion at Princess Anne Academy and the cost of tuition

at the college to which the student might desire to go.

The policy was to equalize things so that “ it is just as

cheap to go outside the State as to stay in the State”

(R. 71).

No colored students have been admitted to the Balti

more Schools of the University of Maryland since the

early nineties when two negroes were admitted as an ex

periment. The practice was discontinued thereafter (R.

86, 107). Out of a faculty of eighteen instructors at the

Law School, twelve are in general practice in Maryland

or on the bench (R. 85).

13

ARGUMENT.

I.

M ANDAM U S IS N O T TH E PROPER REM EDY IN TH IS CASE.

1. Petitioner Has No Right to Sue in Mandamus to Com pel the

University Officials to A dm it Him. His Rem edy, If Any, Is by A p

propriate A ction to Require the Proper State Officials to Supply a Law

School fo r Negroes.

In Cumming vs. County Board of Education, 175 U.

S. 528, 44 L. ed. 262, certain negroes sued a Georgia board

of education to enjoin it from maintaining a high school

for white children without providing a similar school for

colored children which had existed and had been discon

tinued. The Supreme Court of Georgia upheld the denial

of the writ. The Supreme Court of the United States af

firmed this judgment. In discussing the remedy sought

the Supreme Court said, at page 266, law edition:

“ If, in some appropriate proceeding instituted di

rectly for that purpose, the plaintiffs had sought to

compel the Board of Education, out of the funds in

its hands or under its control, to establish and main

tain a high school for colored children, and if it ap

peared that the Board’s refusal to maintain such a

school was in fact an abuse of its discretion and in

hostility to the colored population because of their

race, different questions might have arisen in the

state court. ’ ’

The basis of mandamus is a right in the petitioner and

a corresponding duty in the defendant. No duty arises in

the officials of the University of Maryland to admit a col

ored man to its law schools merely because the State has

not provided a separate law school for colored persons.

The duty, if any, is upon the proper state officials to pro

vide such a separate institution; and not upon the law

14

school to admit a negro contrary to long established pre

cedent and contrary to the public policy of this State

founded in tradition and in statute law.

To require the University to admit a negro, in the ab

sence of any legislative authority so to do, and contrary

to the settled policy of this State, would be to enlarge the

functions of the University by judicial mandate. The

State has established an elaborate system of separate ed-

ucation for its colored citizens. If it be found that this sys

tem is not adequate in every respect, the remedy certainly

is not to pick out the University of Maryland and to seek

by judicial action to compel it to supply the missing

link.

Suppose there were a men’s college and a women’s col

lege as part of the University and suppose that fire de

stroyed the men’s college. Is it conceivable that man

damus would lie to require the women’s college to admit

men students merely because the men thus were left with

out facilities for education! If the proper authorities did

not rebuild the men’s college their remedy, if any, doubt

less would be against these authorities. Their remedy cer

tainly would not be, by mandamus, to compel the women’s

college to take them in.

In Martin vs. Board of Education, 42 W. Ya. 514, 26 S.

E. 348 (1896) a negro citizen, resident of a district which

provided white schools but no colored schools, sued to

have his children admitted to a white school. The Court

said, at page 349 :

‘ ‘ Petitioner’s counsel insists that * * * because the

legislature and the board of education had failed to

make proper provision to afford equal facilities to

15

colored children, that they are entitled to attend the

school provided for white children, on equal terms.

Such a determination would be, in effect, permitting

the neglect of the legislature or board of education

to abrogate the Constitution, while it is the para

mount duty of this Court to see that they obey it.

Therefore the circuit court could not do otherwise

than refuse the prayer of the petition.”

It is apparent that the courts cannot remedy the lack

of school facilities by enlarging the powers of existing

schools contrary to the public policy of a state as ex

pressed in its laws and in its practice.

Also it is well settled that mandamus will not lie to

compel the performance of a discretionary act. Woods

vs. Simpson, 146 Md. 547. Petitioner cannot point to any

statutory or charter provision requiring the University

to admit colored persons. It is clear that the University’s

rights to determine what class or what individual may be

admitted or barred from its cloisters is a matter within

its discretion, to be exercised in its best judgment and

in accordance with public policy. Therefore its exercise

of this discretion is not within the control of the courts.

In Clark vs. Board of Directors, 24 Iowa 266 (1868) it

was held that where a discretion is thus left to the board

of directors it cannot be controlled by mandamus even

though the discretion be unwisely exercised.

In State vs. School District, 154 Ark. 176 (1922) it was

held that the action of a school board in classifying pupils

on the basis of color is discretionary and no right of man

damus will issue unless it can be shown that the Board

acted arbitrarily.

16

In Guthrie vs. Board, 86 Old. 24 (1922) it was held in a

similar case that mandamus will not lie where its issu

ance would work injustice or introduce confusion and

disorder, citing 26 Cyc. 287.

Therefore it is urged that mandamus against the Uni

versity is not open to the petitioner in this case.

II.

TH E EXCLUSION OF TH E APPELLEE DOES N O T V IO L A T E HIS

C O N ST ITU T IO N A L R IG H TS.

1. Since education is exclusively a State matter, he has no right

to adm ission m erely because he is a citizen o f the United States.

At the outset of a constitutional inquiry it is pertinent

to consider the nature of the right claimed to be im

paired and the protection of that right asserted to be

given by the federal constitution. In the sixteenth para

graph of the complaint in this case it is asserted that

the actions of the respondents “ violate the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States in

that they amount to a denial to Petitioner, a citizen of the

United States and of the State of Maryland, by the State

of Maryland or an administrative department thereof, of

the equal protection and benefits of the laws, as secured

to him by the said Fourteenth Amendment and the law

of the land; and in that such acts were unequal, oppres

sive and discriminatory and deprived the said Donald

G. Murray, Petitioner, of his liberty and property with

out due process of law as guaranteed him by the Four

teenth Amendment and the law of the land aforesaid.”

(R. 7,8).

17

No violation of the Constitution of Maryland is alleged

in this case.

It is submitted that education is purely a matter of

State concern and does not affect a person as a citizen

of the United States.

As was said by the Supreme Court in the Slaughter

House Cases, 16 Wall. 36, 21 L. ed. 394 (1873), the privi

leges and immunities of citizens of the United States are

those which arise out of the nature and character of the

national government, the provisions of its constitution or

its laws and treaties made in pursuance thereof; and it

is those which are placed under the protection of Con

gress by this clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Fur

ther it said:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment recognizes a dis

tinction between citizenship of a state and citizen

ship of the United States * * * It is quite clear then

that there is a citizenship of the United States and

a citizenship of a State which are distinctive from

each other and which depend upon different charac

teristics or circumstances in the individual.”

This decision has been commonly regarded as having

established a dual citizenship in an individual, a state

citizenship and a United States citizenship. Education

has been consistently held one of those matters pertain

ing to an individual as a citizen of a state and not as a

citizen of the United States. As was said in Lehew vs.

Brummell, 103 Mo. 546, 550, 15 S. W. 765 (1890) :

“ The common-school sysem of this state is a

creature of the state constitution and the laws passed

pursuant to its command. The right of children to at

tend the public schools and of parents to send their

children to them is not a privilege or immunity be

18

longing to a citizen of the United States as such. It

is a right created by the state, and a right belonging

to citizens of this state, as such.”

In Piper vs. Big Pine, 193 Cal. 664, 669 (1924), it was

said:

“ The privilege of receiving an education out of

the expense of the state is not one belonging to those

upon whom it is conferred as citizens of the United

States. The federal constitution does not provide

for any general system of education to be conducted

or controlled by the national government. It is dis

tinctly a state affair.”

In Gumming vs. County Board of Education, supra,

where there was under review a state court decision de

nying an injunction against the maintenance of a white

high school while failing to maintain a colored one, the

Supreme Court, in denying the right of negro petition

ers, said:

“ Under the circumstances disclosed, we cannot

say that this action of the state court was, within the

meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, a denial by

the state to the ■ plaintiffs and to those associated

with them of the equal protection of the laws or of

any privileges belonging to them as citizens of the

United States. We may add that while all admit that

the benefits and burdens of public taxation must be

shared by citizens without discrimination against

any class on account of their race, the education of

the people in schools maintained by state taxation is

a matter belonging to the respective states, and any

interference on the part of Federal authority with

the management of such schools cannot be justified

except in the case of a clear and unmistakable dis

regard of rights secured by the supreme law of the

land. We have here no such case to be determined;

19

and as this view disposes of the only question which

this court has jurisdiction to review and decide, the

judgment is affirmed.”

In a Kentucky case it was held that the benefits of

negroes in the school-fund of Kentucky must be received

“ as a citizen of this commonwealth and not as a citizen

of the United States. ’ ’

Marshall vs. Donovan, 73 Ky. 681 (1874).

Further, the Kentucky Court said, at p. 688:

“ These interests and benefits are privileges and

immunities pertaining to the citizenship of the State

owning the school fund and maintaining the school-

system, and they must be secured and protected by

the state government. They do not fall within that

class of fundamental rights which, according to the

opinion of the Supreme Court in the Slaughter

House cases, are under the special care of the Fed

eral government. ’ ’

In Cory vs. Carter, 48 Ind. 327 (1874) a negro sued in

mandamus on behalf of his children and grandchildren

to compel admittance to a white school. It was held, in

denying the right, that the legislature had not provided

for the admission of colored children into the same

schools as white children; and even if the Fourteenth

Amendment required their admission the courts cannot,

in the absence of legislative authority, confer the right

upon them.

In People vs. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438 (1883) suit was

brought on behalf of a colored girl to require her admis

sion into a white school. The Court of Appeals of New

York, through Chief Justice Ruger, held that the Four

20

teenth Amendment does not operate on school classifica

tions. Reviewing the history of this amendment and cit

ing the Slaughter House Cases, supra, the Court said, at

page 447:

“ It would seem to be a plain deduction from the

rule in that case that the privilege of receiving an

education at the expense of the state, being created

and conferred solely by the laws of the state, and al

ways subject to its discretionary^ regulation, might

be granted or refused to any individual or class at

the pleasure of the state. This view of the question is

also taken in State vs. McCann, 21 Oh. St. 210, and

Cory vs. Carter 48 Ind. 337. The judgment appealed

from might, therefore, very well be affirmed upon

the authority of these cases.”

This case also distinguishes “ social rights” from civil

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Gong Lum vs. Rice, 275 U. S. 78, 72 L. ed. 172 (1927)

it was held that no right of a Chinese citizen of the United

States under the Federal constitution is infringed by

classifying her for purposes of education with colored

children and denying her the right to attend schools es

tablished for the white race. The Court said:

“ The decision (to bar the Chinese person from its

white schools) is within the discretion of the state

in regulating its public schools and does not conflict

with the Fourteenth Amendment.”

In Hamilton vs. University of California, 79 L. ed. 159,

(1934) where it was held that military training might be

made compulsory for all students of the University, the

Supreme Court said, at page 166:

“ The privileges and immunities protected are

only those that belong t o . citizens of the United

21

States as distinguished from citizens of the state—

those that arise from the constitution and laws of the

United States as contrasted with those that spring

from other sources.”

As was held in Gong Lum vs. Rice, supra, classification

of students on the basis of race and color is a matter ex

clusively of state policy and does not conflict with any

provisions of the Federal constitution.

It is submitted that there is no violation of any Fed

eral constitutional privilege or immunity in the action of

the Eegents in denying admission to petitioner on the

grounds that he is a negro.

2. The equal protection o f the laws does not prevent classifica

tion on the basis o f race.

As pointed out above, classification of students is a

matter of internal State policy. If it were unconstitu

tional to classify on the basis of race, it also would be im

proper to classify on the basis of studies, or on the basis

of sex. Certainly it cannot be contended that if a state

provided a law school for its citizens it also must provide

a medical school, or an engineering school. The University

of Maryland includes among its Baltimore Schools a law

school and a medical school. It does not include an en

gineering school. And yet this is a discrimination in fa

vor of those desiring to study law or medicine and against

those desiring to study engineering. Similarly a state

might provide, without encountering constitutional ob

jections, a certain school for men without a correspond

ing school for women. Distinctions on the basis of sex

uniformly have been upheld by the courts.

22

In Quong Wing vs. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59, 56 L. ed.

350, the Supreme Court, speaking through Mr. Justice

Holmes, upheld such distinctions in these words:

“ If the State sees fit to encourage steam laundries

and discourage hand laundries, that is its own affair.

And if, again, it finds a ground of distinction in sex,

that is not without precedent. It has been recog

nized with regard to hours of work. Muller vs. Ore

gon, 208 IT. S. 412, 52 L. ed 551, 28 Sup. Ct. Hep. 324,

13 A. & E. Ann. Cas. 957. It is recognized in the re

spective rights of husband and wife in land during

life, in the inheritance after the death of the spouse.

Often it is expressed in the time for the coming of

age. If Montana deems it advisable to put a lighter

burden on women than upon men with regard to an

employment that our people commonly regard as

more appropriate for the former, the Fourteenth

Amendment does not interfere by creating a ficti

tious equality where there is a real difference. The

particular points at which that difference shall be

emphasized by legislation are largely in the power

of the state.”

Certain discriminations, either against persons, or

classes, or occupations are found in our tax laws, our

license laws and even in the classification of what work

may be performed on Sundays. As this Court said in

Ness vs. Supervisors, 162 Md. 529, at page 537:

“ Discriminations in the ordinance between activi

ties to be permitted and those not to be permitted on

Sundays are objected to as unconstitutional because

of the inequality of treatment of citizens engaged

in the activities of the one group and the other, and

because of supposed deprivation of the liberty and

property of those whose activities are excluded, with

out due process of law. * * * And that there are dis

criminations which cannot be explained or justified

23

by reasons is possibly true. But what is tolerable and

what intolerable in Sunday observance seems to be

a question which cannot be fully answered by a pro

cess of reason. * * * But the mere fact of inequality

is not enough to invalidate a law, and the legislative

body must be allowed a wide field of choice in deter

mining what shall come within the class of permit

ted activities and what shall be excluded” .

This Court found no such “ obviously arbitrary and

grievous discrimination” as would make the ordinance

unconstitutional (page 538).

And again, in Jones vs. Gordy, 180 Atl. 272, this Court

held that the Legislature had a wide discretion in fram

ing excise laws.

“ And unless the distinctions it makes” , the Court

said, “ are obviously without reasonable foundations

in conditions to be dealt with, there is no departure

from constitutional powers, and the courts have no

function to fulfill.” (page 277).

In Great House vs. Board of School Commissioners,

198 Ind. 95, 151 N. E. 411 (1926) it was held at page 105:

‘ ‘ The classification of scholars on the basis of race

or color, and their education in separate schools, in

volve questions of domestic policy which are within

the legislative discretion and control, and do not

amount to an exclusion of either class. The Legisla

ture has the power to provide for either separate or

mixed schools.”

Also see Ilayman vs. Galveston, 273 U. S. 414.

It is submitted that the “ equal protection” clause does

not require a State to build a school for Negroes, just be

cause it builds one for whites. Appellees cannot point to

24

any decision of this Court, or any decision of the Supreme

Court, which requires equality of treatment or which

forbids classification on the basis of race or color.

III.

TH E L A W SCH OOL OF TH E U N IVER SITY O F M A R Y LA N D IS

NOT AM ENABLE T O CO N ST ITU T IO N A L

LIM ITATIO N S.

1. The University o f Maryland Is in the Nature o f a Private

Corporation.

In the third paragraph of the petition it is asserted

that the University is an administrative department of

the State of Maryland and that it performs “ an essential

governmental function” , with funds derived principally

from the general treasury of the State. The regents in

their answer admitted the “ allegation of fact” of this

paragraph, denying however that the Baltimore Schools

derive their maintenance funds principally from the gen

eral treasury (R. 4, 17).

The admissions of fact, of course, admit no conclusion

of law; and it is submitted that whether the University

of Maryland is a State Department or is in the nature

of a private institution for the purposes of this case, is a

question of law which by the pleadings is left open for

the determination of this Court.

As pointed out by this Court in University of Maryland

vs. Coale, 165 Md. 224, 231:

‘ ‘ The present University of Maryland is a con

solidation of the University of Maryland, as incor

porated by the Acts of 1812, chapter 159, and the

Maryland State College of Agriculture, incorporated

under the Acts of 1916, Chapter 372. The act of con

solidation was passed by the Legislature of 1920,

chapter 480.”

25

There is nothing in the consolidation Act which strips

the University of Maryland, and its separate component

schools, of its status as a private corporation. This Act

(chapter 480, Acts of 1920) provides that the consoli

dated University should possess, in addition to the

powers of the Maryland State College of Agriculture,

“ the powers, rights and privileges heretofore possessed

by the Regents of the University of Maryland, under the

charter of the University of Maryland, and may exer

cise such of them as they shall from time to time deem

judicious ’

The specific question as to whether or not the Uni

versity of Maryland, as organized by the Acts of 1812,

is a public or private corporation, was passed upon by

this Court in 1838. There it was held that the University

of Maryland was a private corporation. After a full dis

cussion of the organization of the University, which itself

was a consolidation of separate schools and colleges,

this Court said:

“ The corporation of the University has none of

the characteristics of a public corporation. It is not

a municipal corporation. It was not created for

political purposes, and is invested with no political

powers. It is not an instrument of the government

created for its own uses, nor are its members of

ficers of the government or subject to its control in

the due management of its affairs, and none of its

property or funds belong to the government. The

State was not the founder, in the sense of that term

as applied to corporations. It was the creator only,

by means of the act of incorporation, and may be

called the incipient, not the perficient founder.

< i * * * it appears from the statement of the

evidence, that it has been endowed to a small amount

26

by private donations, and no donations that it can

derive from the bounty of the State would change

its character, and convert it into a public corpora

tion. ”

University of Maryland vs. Williams, 9 6 . &

J. 365, 397-400.

In the re-organization plan of the State Government

in 1922 the University retained its corporate status and

the power to determine policies under which it should

operate to the best public interest.

It is true that the Attorney General has consistently

taken the position that the University of Maryland is a

department of the State Government, for certain pur

poses, such as immunity from suit.

Volume 16 of the Official Opinions of the At

torney General, page 386.

The property of the University is owned by the State,

and for general administrative purposes, it is treated

like any other department.

Volume 9 of the Official Opinions of the At

torney General, page 273.

The Attorney General advises and represents the Uni

versity in legal matters, and its funds are disbursed

through the State Comptroller.

However, in the matter of admitting students, the

Board of Regents acts in the exercise of a charter power.

The mere fact that it has been treated as a State Depart

ment for some purposes, does not affect the question. As

was said in the Williams case, supra, page 398:

27

“ It is said there have been subsequent endowments

by the State. If it be so, that cannot affect the char

acter of this corporation. If eleemosynary and pri

vate at first, no subsequent endowment of it by the

State, could change its character, and make it pub

lic. ’ ’

It may also be noted that this question was not raised

or discussed in the Coale case, supra. It may be signifi

cant, however, that the Supreme Court dismissed the ap

peal in that case, for want of a substantial Federal ques

tion, whereas in the Hamilton case, supra, it assumed

jurisdiction, commenting on the fact that by express Con

stitutional provision and court decision, the University

of California was part of the State Government.

2. Private Institutions May Select Their Students Arbitrarily,

W ithout Regard to the Fourteenth Am endm ent.

It is well settled that the provisions of the Fourteenth

Amendment refer to the action of the States exclusively

and not to the action of individuals and private corpora

tions.

In Clark vs. Maryland Institute, 87 Md. 643 (1898),

there was under consideration a similar question raised

by a colored citizen who was attempting to force his ad

mittance into the Maryland Institute. This Court pointed

out that the school is a private corporation, not created

for political purposes nor endowed with political powers.

It held:

“ It has none of the faculties, functions or features

of a public corporation as they are designated in the

Regents’ case, 9 Gill & Johnson, 365, and the many

other cases which have followed that celebrated

decision.” Page 658.

28

In the Maryland Institute case there was a precedent

of four colored persons who had been admitted prior to

the refusal of this applicant. Commenting upon this the

Court said:

“ It (the Maryland Institute) was established for

the benefit of white pupils, and has never admitted

any other kind with the exception of the four in

stances already mentioned. When it found that the

admission of these pupils had a very injurious effect

on its interest, and seriously diminished its useful

ness, it certainly had the right to refuse to continue

such a disastrous departure from the scheme of ad

ministration on which it was organized. It would

have been mere folly to persevere in the experiment

under the existing circumstances. We suppose that

it could hardly be maintained that the constituted

authorities of the corporation did not have the right

to conduct its affairs according to the plan and policy

on which it was founded. # * *” Page 658.

Referring to the constitutional question the Court held

that the Maryland Institute, in denying admittance to

the negro, impaired no constitutional right. It said, at

page 661:

“ * * * The Constitution of this State requires

the General Assembly to establish and maintain a

thorough and efficient system of free public schools.

This means that the schools must be open to all with

out expense. The right is given to the whole body of

the people. It is justly held by the authorities that

‘ to single out a certain portion of the people by the

arbitrary standard of color, and say that these shall

not have rights which are possessed by others, denies

them the equal protection of the laws’. Cooley on

Torts, page 287, where a large number of cases are

cited. Such a course would be manifestly in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment, because it

would deprive a class of persons of a right, which the

29

Constitution of the State had declared that they

should possess. Excellent public schools have been

provided for the education of colored pupils in the

city of Baltimore. But the Maryland Institute is

not a part of the public school system. This has

been solemnly adjudged by this Court. St. Mary’s

School v. Brown, 45 Maryland 310. The appellant

has no natural, statutory or constitutional right to

be received there as a pupil, either gratuitously or

for compensation. He has the same rights, which

he has in respect to any other private institution;

and none other or greater. * * * ”

Just as Maryland Institute is not a part of the public

school system, neither is the University of Maryland.

In Booker vs. Grand Rapids Medical College, 156 Mich.

95 (1909), two negroes were taken into the school and the

school attempted to bar them from returning the second

year. It was held that the Medical College was a private

institution which “ may select those whom they will re

ceive as. students” . The Court further said:

“ The arbitrary refusal to receive any student

would not violate any privilege or immunity resting

in the positive law, protected or granted by the

Federal or State Constitution. ’ ’

Also see note in 24 L. R. A. (N. S.) 447.

3. The Law School o f the University Derives Its Maintenance

Principally From Tuition Charges to Students.

As asserted by the Regents’ in their answer, and un

controverted in the testimony, ‘ ‘ the Baltimore schools of

the University of Maryland, of which the Law School is

a part, do not derive their maintenance funds principally

from the general treasury of the State but are supported

principally by tuition fees paid by students in Siaid

school” (R. 17).

30

For all these reasons it is submitted that the University

of Maryland and its school of law are not subject to the

provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that they

may choose such students as they desire to admit.

IV.

EVEN IF TH E L A W SCH O O L IS A PUBLIC IN STITU TION AM EN

ABLE TO TH E FOU RTEEN TH AM ENDM ENT, IT IS NOT

REQUIRED T O A D M IT NEGROES BECAUSE TH E S T A T E

PRO VID ES SCH OLARSHIPS FOR TH EIR

EXCLU SIVE USE.

1. The P olicy o f This State Is to Separate the Races.

(a) In railway coaches.

It has long been the policy of this State to provide sepa

rate facilities for the two races in railway coaches and

on steamboats. Article 27 of the Code, Sections 432 to

448 inclusive, is statutory authority for the separation

of white and colored passengers in these mediums of

public transportation.

This segregation statute has been upheld by this Court,

as to intra-state commerce, in Hart vs. State, 100 Md.

595, in which the Court of Appeals quoted with approval

from West Chester and Philadelphia Railroad Com

pany vs. Miles, 55 Pa. St. 209 (1867) where it was said,

prior to a legislative Act prohibiting segregation, at

page 212:

“ It is much easier to prevent difficulties among

passengers by regulations for their proper separa

tion, than it is to quell them. The danger to the

peace engendered by the feeling of aversion between

individuals of the different races cannot be denied.

It is the fact with which the company must deal. If a

negro takes his seat beside a white man or his wife

or daughter, the law cannot repress the anger, or

31

conquer the aversion which some will feel. However

unwise it may be to indulge the feeling, human in

firmity is not always proof against it. It is much

wiser to avert the consequences of this repulsion of

race by separation than to punish afterwards the

breach of peace it may have caused * * *.”

The Pennsylvania Court likened the race classification

to the separation of the sexes:

“ The ladies’ car is known upon every well-regu

lated railroad, implies no loss of equal right on the

part of the excluded sex, and its propriety is doubted

by none.” Page 211.

The power of the State to separate the races in railway

coaches has been upheld by the Supreme Court in Plessy

vs. Ferguson, 163 IJ. S. 537 (1895).

Discussing the applicability of the Fourteenth Amend

ment the Supreme Court held that it was not intended to

abolish distinctions based on color and pointed to the

“ most common instance” of separation in schools. It

said, at page 544 :

“ The object of the amendment was undoubtedly

to enforce the absolute equality of the two races be

fore the law, but in the nature of things it could not

have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon

color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from polit

ical equality, or a commingling of the two races upon

terms unsatisfactory to either. Laws permitting,

and even requiring their separation in places where

they are liable to be brought into contact do not nec

essarily imply the inferiority of either race to the

other, and have been generally, if not universally,

recognized as within the competency of the state

legislatures in the exercise of their police power.

The most common instance of this is connected with

32

the establishment of separate schools for white and

colored children, which have been held to be a valid

exercise of the legislative power even by courts of

states where the political rights of the colored race

have been longest and most earnestly enforced.”

(Italics supplied).

Commenting upon the Plessy case, Freund in his work

on the Police Power, Sec. 699c, says

“ The following seems to be the strongest argu

ment in favor of the legality of compulsory separa

tion: it is legitimate for transportation companies

to provide separate accommodations for the two

races, just as it may provide ladies’ waiting rooms

or cars for smokers, as conducive to the comfort

of the parties thus separately accommodated. Trans

portation companies may be subjected to public con

trol in the interest of public convenience and com

fort, and if separate accommodation is generally de

manded, and not unreasonably burdensome it may

be compelled by law. It then follows also that the

failure to provide it or the failure to maintain it

on the part of the railroad company, may be visited

with penalties, and a passenger who intrudes him

self into a compartment in which he is not wanted

may likewise be punished. The facts in Plessy vs.

Ferguson did not call for more than a recognition of

these principles.”

Also see Article 27, Section 365 of the Code, which for

bids intermarriage of white and colored persons in Mary

land. And also Article 27, Section 415.

(b) In private and public educational institutions, at

scholastic, collegiate and professional levels.

It is a matter of general knowledge that there is no

mixture of the races in educational institutions in the

State of Maryland. As to private institutions the case of

33

Clark vs. Maryland Institute, 87 Md. 643, exemplifies the

policy of this State on the question.

Public Schools.

In public education, the State has erected a dual sys

tem giving practically identical instruction to each race.

In 1872 by Chapter 377, sub-chapter 18 (now codified

as Section 200 of Article 77 of the Code of Public Gen

eral Laws 1924 Edition), the Legislature of Maryland

established and provided a system of separate public

schools for the exclusive use of the colored children of

the State. This Section of the Code reads as follows:

“ 200. It shall be the duty of the county board of

education to establish one or more public schools in

each election district for all colored youths, between

six and twenty years of age, to which admission

shall be free, and which shall be kept open not less

than one hundred and sixty (160) actual school days

or eight months in each year; provided, that the col

ored population of any such district shall, in the

judgment of the county board of education, warrant

the establishment of such a school or schools.”

Furthering this policy of separate education, our Leg

islature has provided for the establishment of colored

industrial schools in each county of the State where there

is need of one, in which the colored youths of the State

are given instruction in domestic science and the indus

trial arts. (Code, article 77, section 211).

The State also provides a State Normal School for

the instruction and practice of colored teachers in the

science of education. (Code, Article 77, Section 256).

As to the character of the public education furnished

the colored children in public schools of the State, Doug

34

las High School, an all-Negro institution, is reputed to

be as good as any in Baltimore City (R. 101); whereas

in the county schools the colored children study the same

curriculum and the facilities of both races are substan

tially the same. (R. 87-100).

College Education.

At college levels the demand for education by the ne

gro population of the State is much less1, but the State

has met this demand insofar as it exists by the creation

of an “ eastern branch” of the University of Maryland,

known as Princess Anne Academy and situated at Prin

cess Anne, Somerset County. This institution is devoted

exclusively to the higher education of colored boys and

girls of the State and has a rating of a junior college.

(R. 51).

While this college has in the past accommodated more

than one hundred students there are at the present time

only thirty-three students at the school. Thus the supply

is greater than the demand for this type of education,

which is largely agriculture and home economics.

For those negro students who wish a four year liberal

arts college, the State annually appropriates a sum of

money to Morgan College (R. 105).

Post-Graduate Education.

Up to the present time there has been no demand for

professional or postgraduate education. As far as the law

school is concerned, there have been but nine negro ap

plicants for admission for the years 1933, 1934 and 1935

and before that there were none (R. 107).

35

It is a settled policy of the University not to accept

negroes except at its eastern branch at Princess Anne,

as shown by the minutes of the Board of Regents (R. 60-

61).

2. Separation o f the Races in Educational Institutions Has Been

Upheld by the Highest Authority.

There is no doubt of the power of a State to segregate

the races in schools.

Gong Lum vs. Rice, Supra; 11 Corpus Juris, 806 (Civil

Rights, Section 11) and cases there cited.

In the case of Wall vs. Oyster, 31 Appeals of D. C. 180

(1910) a federal court held that “ Congress may consti

tutionally provide for the separation of white and col

ored children in the public schools of the District of Co

lumbia. ’ ’

In this State there is statutory authority for separation.

In Maryland we have not only a public policy of sepa

ration of the races in educational institutions but statutes

authorizing and requiring it. At professional levels the

Acts of 1933, Chapter 234 and the Acts of 1935, Chapter

577 clearly point out the State policy in this respect.

Even without statutory authority to separate the races

it appears that the State, or any corporation organized

under the State laws, has a right to separate the races.

As this Court said in Hart vs. State, supra, speaking of

segregation in railway coaches:

“ It seems to be well settled that a common carrier

has the power, in the absence of statutory provision,

36

to adopt regulations providing separate accommoda

tions for white and colored passengers, provided, of

course, no discrimination is made.” Page 601.

If common carriers may segregate the races without

statutory authority it follows that private schools and

public institutions operating under charter from the

State may do likewise.

One of the earliest cases on segregation of white and

colored children in schools is Roberts vs. Boston, 5 Cush.

198 (1849). A colored girl brought action against the

school authorities of Boston because they excluded her

from a white school and required her to attend a school

maintained exclusively for colored children. The State

of Massachusetts had neither authorized nor forbidden

race segregation in the schools, but there was a State

constitutional injunction of equal protection, the same as

the Fourteenth Amendment (see Gong Lum vs. Rice,

supra at page 87). It had been the public policy of Bos

ton to segregate the races for at least fifty years. It was

held by the Supreme Court of Massachusetts that the

school board had the power to segregate the races with

out specific statutory authority upon the subject.

“ The great principle,” said Chief Justice Shaw,

“ advanced by the learned and eloquent advocate of

the plaintiff (Mr. Charles Sumner) is, that by the

Constitution and laws of Massachusetts, all persons

without distinction of age or sex, birth or color,

origin or condition, are equal before the law. * * *

But, when this great principle comes to be applied

to the actual and various conditions of persons in

society, it will not warrant the assertion that men

and women are legally clothed with the same civil

and political powers, and that children and adults

are legally to have the same functions and be sub

37

ject to the same treatment; but only that the rights

of all, as they are settled and regulated by law, are

equally entitled to the paternal consideration and

protection of the law for their maintenance and se

curity. ’ ’

It was held that the powers of the school board extended

to the establishment of separate schools for children of

difference ages, sexes, and colors, and that they might

also establish special schools for poor and neglected

children, who have become too old to attend the primary

school, and yet have not acquired the rudiments of learn

ing, to enable them to enter the ordinary schools.

The cases heretofore cited have concerned: schools. One

of the few college cases we have found is Berea College

vs. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45 (1908)—affirming 123 Ky. 209,

94 S. W. 623. In this case the State of Kentucky passed a

law in 1904 prohibiting the teaching of white and negro

pupils in the same institution. It was held that in this

case the State statute, when applied to a corporation as

to which the State has reserved the power to alter, amend

or repeal its charter, does not deny due process of law

or otherwise violate the Federal constitution.

Thus it is clear that separation of the races is not pro

hibited by the Fourteenth Amendment. While some cases

from other states have held that, in order to justify sepa

ration, substantially equal facilities must be granted each

race, it should be pointed out that neither the Supreme

Court of the United States nor this Court has imposed

the test of “ substantial equality” .

The segregation of the races, by statute or otherwise,

long has been recognized by this Court. As was said by

Judge Sloan, speaking for the Court in Lee vs. State,

164 Md. 550, at 553:

38

“ Wliite and colored alike are entitled to the equal

protection of the laws, yet states have not been de

nied the right to pass and enforce many segregation

statutes. Railways and other means of transporta

tion have been required by states, and lawfully, to

provide separate compartments for whites and col

ored. Innkeepers, in the conduct of their business,

are not required to throw their houses open to whom

soever chooses to be their guests. Hall v. De Guir,

95 U. S. 485, 24 L. ed. 547, 553; Chiles v. G. & 0. R.

Go., 218 U. S. 71, 30 S. Ct. 667, 54 L. ed. 936. If the

defendant’s contention is sound or logical, then so

long as this State has separate schools' for white

and colored children, he could not be brought to trial,

for nowhere is the separation more marked than

there. Yet it has been frequently held that separate

schools do not violate the provisions of the Four

teenth Amendment. Gumming v. Board of Educa

tion of Richmond County, 175 U. S. 528, 20 S. Ct. 197,

44 L. ed. 262, and note. In all of the cases the right

to make such regulations in public places and institu

tions is recognized, provided equal advantages and

comforts are afforded both races, and there is no

suggestion here that this has not been done. ’ ’

3. This State A ffords Its C olored Citizens Substantially Equal

Facilities fo r Public Education.

(a) It has a dual and practically identical system of

secondary education for the two races.

As pointed out above, this State maintains a dual

system of public education in the lower schools, sub

stantially equal and in most respects identical. Huffing-

ton, (R. 93; 87-100); Cook (R. 102). It not only fur

nishes an adequate system of separate education for its

colored youth but it provides substantially more than

other Southern states.

39

Maryland spends more money on negro education per

capita in the lower schools than any other Southern

State. In the scholastic year 1929-30 Maryland spent

$43.16 on each colored child enrolled in its schools. In

other states the figure ranged from $5.45 in Mississippi

to $34.25 in Oklahoma. No Southern state spends as

much on its colored education as it does on its white but

in Maryland the ratio is more favorable to the negro

than in the other states.

See McCuistion’s “ Financing Schools in the South,”

published in 1930 by State Directors of Educational Re

search in the Southern States, 502 Cotton States Build

ing, Nashville, Tenn.

In considering this publication it must be borne in

mind that money spent is by no means an exact criterion

of equality, since colored children get more for their

school dollar than do whites. See testimony of Huffing-

ton (R. 99) where it is stated that colored teachers’ sal

aries are lower than whites but this does not affect the

equality of education received. In like manner, colored

schoolhouses ordinarily do not cost as much as those of

white children, but this would not affect the quality of

education received. The above figures are cited merely

to show that Maryland spends more on colored education

than any other Southern state.

(b) It affords substantially equal opportunities at

collegiate levels at Princess Anne Academy, at Morgan

College and by scholarships.

As pointed out above, Maryland maintains the Prin

cess Anne Academy as the eastern branch of the Univer

sity of Maryland. Here the enrollment at the present

40

time is only thirty-three students, although more than

one hundred may be accommodated (E. 74). Graduates

of this institution, which is a junior college, may go into

the third or junior year of Morgan College in the State,

or of other colleges out of the State. The educational ad

vantages afforded are approximately the same as at

other junior colleges. The State appropriation for Prin

cess Anne is $15,000 a year; on the present basis of the

student enrollment it is $468. per student (E. 67).

On the basis of money spent by the State on white and

colored college work, the following comparisons gleaned

from the testimony are pertinent (E. 67, 83, 84,105):

Colored

Morgan

Student

enrollment

State

appropriation

Amt.

spent per

Student

enrolled

1934-35 600 $23,400. $39.

1935-36

Princess

Anne

600 $35,000. $58.

1934-35

White

Un. of Md.

33 $15,000. $468.

1934-35 3,600 $318,000. $88.

1935-36 3,600 $288,000. $80.

It will be noted from the above that the State appro

priation for the year 1935-36 is greater than the preced

ing year in the case of Morgan College, the colored in

stitution, and less than the preceding year in the case of

the University of Maryland, the white institution.

41

(c) At professional levels it affords no colored

schools because heretofore there has been no sufficient

demand therefor; but the scholarship system offers its

negro citizens opportunities and advantages substan

tially equal to those given its white citizens.

It is apparent at this early stage of the call for pro

fessional education for negroes that there are not enough

students to form separate professional schools for each

group, even if there were money with which to finance

them. There were only nine colored persons who applied

for admission to the School of Law in the years 1933,

1934 and 1935 and none before that (R. 108).

While preserving Maryland’s traditional policy of

separation of the races, the State has met the demand of

the negroes for higher education by establishing a sys

tem of scholarships to institutions out of the State for

the exclusive use and benefit of colored students. This

scholarship policy was launched by the Legislature of

1933, which provided that the Board of Regents of the

University of Maryland might set apart a portion of the

State appropriation for Princess Anne Academy and

establish scholarships for negro students who might wish

to take professional courses or other work not offered in

Princess Anne but which were offered white students at

the University of Maryland. Chapter 234, Acts of 1933.

No special appropriation was made by the Legislature

to finance these scholarships and since the University

budget was severely cut there was no practical benefit to

the colored race from this Act (R. 34-36, 61-64). The

case before us is not affected by this circumstance, how

ever, since Petitioner applied for admissioner to the Law

School for the year 1935-36.

42

The General Assembly at its regular session in 1935

set up a new scholarship statute and appropriated the

sum of $10,000. annually to be set aside for the higher

education of negroes. This Act, after establishing a

“ Maryland Commission on Higher Education of Ne

groes,” of which Judge Morris A. Soper was named

chairman, provided:

“ Sec. 2. And Be It Further Enacted, That it

shall be the duty of said Commission to administer

the sum of Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000) included

in the Budget for the years 1935-36 and 1936-37 for

scholarships to Negroes to attend college outside

the State of Maryland, it being the main purpose of

these scholarships to give the benefit of such col

lege, medical, law, or other professional courses to

the colored youth of the State who do not have facili

ties in the state for such courses, but the said com

mission may in its judgment award any of said

scholarships to Morgan College. Each of said schol

arships shall be of the value of not over Two Hun

dred Dollars ($200). Each candidate awarded such

scholarship must be a bona fide resident of Mary

land, must maintain a satisfactory standard in de

portment, scholarship and health after the award is

made, and must meet all additional charges beyond

the amount of the scholarship to enable him to pur

sue his studies.”

Chapter 577, Acts of 1935.

This Act went into effect on June 1st, 1935. At the time

of the trial below, on June 18th, 1935, three hundred and

eighty colored persons had applied for application

blanks for these scholarships and one hundred and thir

teen completed applications had been turned in. There

were twelve days left in which to file applications (R.

111) .

43

Only sixteen of these completed applications were for

graduate work; and, of these, only one was for law work

(R. 109-110).

It will be noted that from the scholarship Act above

quoted that the maximum available for any one student

is $200 and that the scholarship covers tuition only. Since

it is the policy of the scholarship commission to divide

the appropriation about equally between undergraduate

applicants and graduate applicants (R. 112-113), it will

be seen that there will be at least twenty-five scholar

ships for graduate study (R. 112).

As only sixteen had applied for graduate scholarships,

with but twelve days to go, it is a fair inference that

there were enough scholarships to gratify all graduate

or professional demands for the current year.

The petitioner in this case would have been eligible

for one of these scholarships if he had applied (R. 113);

and since he did not apply, he cannot be heard to deny

the adequacy of the scholarship provision, assuming that

he can be required to accept a fair substitute for con

solidated instruction.

Howard University, in the City of Washington, main

tains the nearest negro law school to Baltimore. There

the tuition is $135.00 per year compared to $203.00

in the day school of the University of Maryland Law

School (R. 34).

In effect the State, by paying petitioner’s tuition at

another school, relieves him from the payment of the

$203.00 he would have to pay as tuition here, which sum

he can apply to his transportation to Howard Law School

or some other school of his choice.

44

A number of authorities have held that where the

State furnishes or pays for transportation of colored

persons to and from a school which is farther away from

their homes than a white school, there is no discrimi

nation or inequality.

In Wright vs. Board of Education, 129 Kan. 852, 284

Pac. 363 (1930) an injunction was sought to prevent the

school board from removing the Wright girl from a

white school to a colored school twenty blocks farther

away. The State agreed to furnish transportation. In

holding that there was no inequality here, the Court

said:

“ Plaintiff lives within a few blocks of Randolph

School (white) and it is convenient for her to at

tend school there. Buchanan school (colored) is

some twenty blocks from plaintiff’s residence and

to attend school there would require her to cross

numerous intersections, where there is much auto

mobile traffic, in going to and from school. No con

tention is made that the Buchanan school is not as

good a school and as well equipped in every way as ,

is the Randolph school. The sole contention made

by appellant here is that defendant’s order that

plaintiff attend school at the Buchanan school is

unreasonable in view of distance she would have