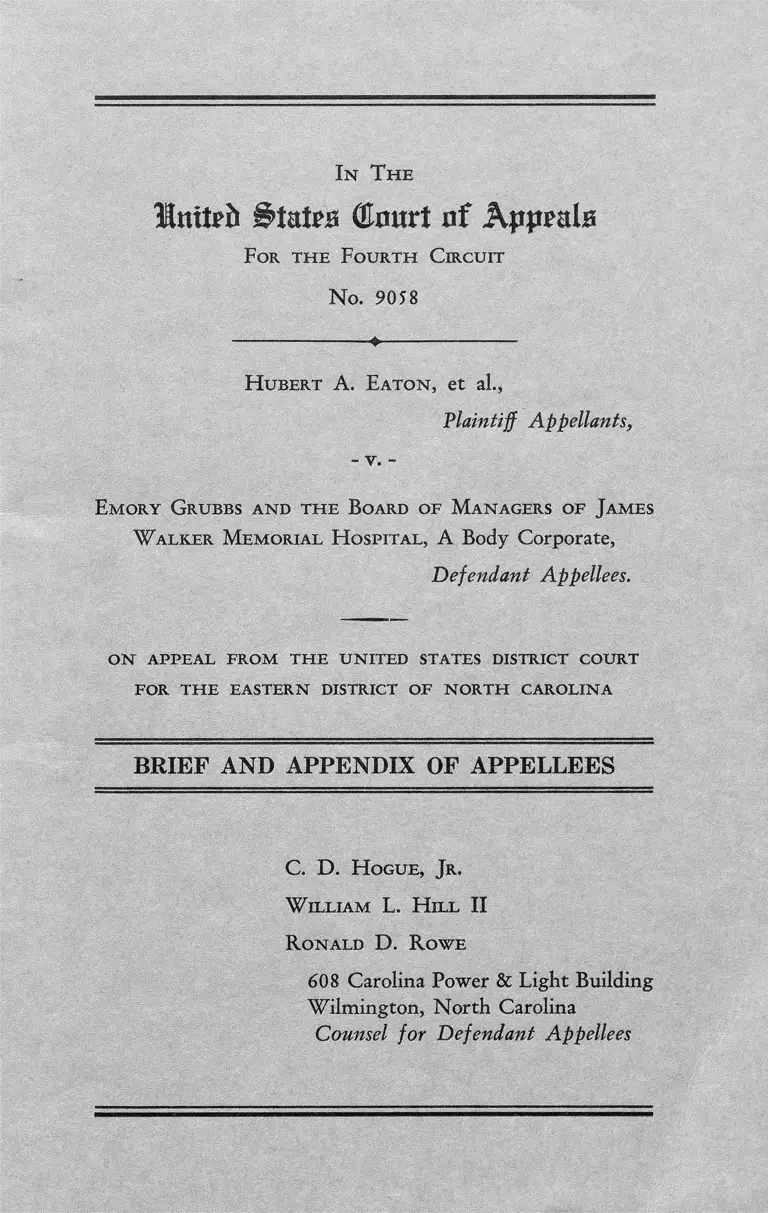

Eaton v. Grubbs Brief and Appendix of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Eaton v. Grubbs Brief and Appendix of Appellees, 1964. 26733d80-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1801d7ae-9886-42fb-b67a-7320c99e2d62/eaton-v-grubbs-brief-and-appendix-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In T h e

Imtefc BUtm (Enurt of Appeals

For th e Fourth C ircuit

No. 9058

----------------------- «-----------------------

H ubert A. Ea t o n , et al.,

Plaintiff Appellants,

- v. -

Emory Grubbs and t h e Board of M anagers of James

W alker M emorial H ospital, A Body Corporate,

Defendant Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF APPELLEES

C. D. H ogue, Jr.

W illiam L. H ill II

R onald D. R owe

608 Carolina Power & Light Building

Wilmington, North Carolina

Counsel for Defendant Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement o f The Case- ________ - - ____________ 1

Questions Presented ______________ _................... .... ........... 2

Statement o f Facts- _____ ____________ _________________ 2

A r g u m e n t ________________________________________________ 4

Point 1 There is no factual element alleged in the

present complaint by plaintiffs, as a basis for

showing State action on the part o f defend

ants, which was not alleged and argued in the

former case involving these plaintiffs_________ 4

Point 2 There has been no change in the law' since

the decision in the prior Eaton case justifying

a change in result____________________________10

Conclusion _______________________________ __ __________ 23

In d ex T o A ppe n d ix

Charter o f Hospital; Chap. 12 Private Laws N . C.

(1901) _________________________________________________ la

Petition for W rit o f Certiorari__________________________ 6a

Reasons for Allowance o f the W rit___________________11a

Conclusion__________________________________________18a

11

T a b l e o f C ases

PAGE

Board of Managers v. City o f Wilmington, 237 N . C.

179, 74 S.E. 2d 749 (1 9 33 )____ __ . . . . . . 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 21

Boman v. Birmingham Bus Company, 280 F. 2d 331

(C. C. A. 3th, 1960)_________________________ ___ 14, 18

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 363 U.S.

715 ----------------- ------------ -- 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 23

Clark v. Nash, 198 U.S. 361_____________________________20

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 299 N .Y . 512,

87 N.E. 2d 541, cert, denied, 339 U.S. 981_______ ____21

Eaton v. Board o f Managers, et al, 164 F. Supp. 191, 261

F. 2d 521 (C. C. A. 4th, 1958), cert, denied, 3 59

U. S. 984-------------1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 23

Hampton v. City o f Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320

(C. C. A. 5th, 1962)...____________________________13, 14

Strickley v. Highland Boy Gold Mining Company, 200

U.S. 527_____________________ _____ ________ ____ _____ 20

Whitney v. State Tax Com., 309 U.S. 530, 84 L. Ed.

909, 915, 60 S. Ct. 63 5...___________________________ ___H

T a b l e o f St a t u t e s

General Statutes of North Carolina

20-7.50 ______________________________________ ______....__19

8 4 -4 ----------------------------------------- ---------------------------18, 19

90-18, 29______ ______ ________ ____ _____________ _______ _______ _______ _______ 18, 19

131-126.3 _______________________ _______...________________17

131-126.4 ______________________ ___________ ________ 17

Private Laves of North Carolina—• Chap. 12 (1901)_____ la

United States Code — 28 U.S.C. 1343 ( 3 ) _______ _______ 4

42 U.S.C. 1533 (4) ( c ) _____ __________ ______ _ _______17

In T he

United Butm (Emirt nf Appeals

F o r t h e F o u r t h C ir cu it

No. 9058

--------------------------------------------- --— -------------------------------------------------------

H u b e r t A. Ea t o n , et al.,

Appellants,

- v. -

Em o r y G ru bbs a n d t h e B o ard o f M a n a g e r s o f Ja m e s

W a l k e r M e m o r ia l H o sp it a l , A Body Corporate,

Appellees.

ON a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d states district c o u r t

FO R T H E E A ST E R N DISTRICT O F N O R T H C A R O L IN A

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

The defendants have no objection to the Statement o f the

Case set out in Plaintiff Appellant’s Brief. The Motion to

Dismiss was filed on the basis o f Eaton v. Board of Managers

of James Walker Memorial Hospital, 261 F. 2d 521 (C. C. A.

4th, 1958). A fter the decision in that case, the plaintiffs did

not move to amend their complaint, but allowed the dismissal

Succintly stated, it is plaintiff’s contention that the form - 15

er case was dismissed because the complaint contained a de

fective statement o f a claim for relief over which this Court

2

has jurisdiction, and that the new complaint expands the old

complaint, corrects the defects, and gives the Court juris

diction. It is defendant’s contention that the former case

finally adjudicated that the defendant Hospital was a private

corporation and could not be sued in the Federal Courts for

infringement o f Civil Rights; that, consequently, the mere

expanding o f the former complaint, with a few additions,

does not now give the Court jurisdiction over this action.

This Court in the former appeal, as well as the Supreme

Court in the Petition for W rit o f Certiorari (which is print

ed in Appellee’s Appendix, P. 6a) had presented to it,

through plaintiffs’ counsel, the very arguments which are be

fore it now; we respectfully submit that there is no differ

ence between the instant case and the previous case, and that

Judge Butler’s Order was correct in dismissing same (A p

pellant’s Appendix 61a-68a).

Questions Presented

1. Does the instant complaint set forth any factual ele

ments as a basis for showing State action on the part o f the

defendants sufficient to allow the Federal District Court to

take jurisdiction o f this action?

2. Since the decision o f the Fourth Circuit Court o f A p

peals in Eaton v. Board of Managers, et al, 261 F. 2d 521

(C .C .A . 4th, 1958), cert, denied, 359 U.S. 984, has there

been a change in the law as set forth by the Supreme Court

o f the United States justifying a change in the result in this

case, in order to give the Federal District Court jurisdiction

thereof?

Statement of Facts

The Statement o f Facts set forth in Plaintiff Appellant’s

Brief is substantially correct. W e feel that the opinion o f

Judge Soper as contained in Eaton v. Board of Managers of

James Walker Memorial Hospital, 261 F. 2d. 521 (C .C.A.

3

4th, 1958), clearly sets forth the pertinent facts which exist

ed at the time o f the former appeal, and which still exist

now. The express purpose o f the incorporation o f the Hos

pital in the Private A ct o f 1901, (Appellee’s Appendix, P. la)

was to remove the Hospital and the property o f the Hospital

from the control o f local municipal authorities. This was

the principal fact involved on the prior appeal, and is still

true at the time o f this appeal.

In addition to these facts, an affidavit has been filed by

Robert R. Martin, present Director o f the Hospital, (A p

pellants’ Appendix 58a) stating that there has been no change

in the operation o f the Hospital since the decision in the

former case, other than a change in the amount o f the per

diem charge for the treatment o f welfare patients. It will

be noted that the amounts received constitute about 2% o f

the gross income o f the Hospital, that the amount paid by

the City for W orkmen’s Compensation treatments since

October 1961 was $1599.21, and that the only contractual

relationship which still exists between the Hospital and the

County is that for the treatment o f welfare patients on a

per diem charge which is set out in this affidavit.

It is thus clear that the Hospital is operated in the same

manner now as it was at the time o f the former decision,

and plaintiffs do not allege any different operation.

4

A R G U M E N T

Point No. 1

THERE IS NO FACTUAL ELEMENT ALLEGED IN THE

PRESENT COMPLAINT BY PLAINTIFFS, AS A BASIS

FOR SHOWING STATE ACTION ON THE PART OF DE

FENDANTS, WHICH WAS NOT ALLEGED AND ARGUED

IN THE FORMER CASE INVOLVING THESE PLAINTIFFS.

A t the outset it must be stated that the basis for the de

fendants’ Motion to Dismiss this action is that the suit is

one o f individuals suing another individual for the infringe

ment o f individual rights, and that the action alleged is not

State action for which redress can be had in the Federal

District Court under 28 U.S.C.A. 1343 (3 ).

The authority for the motion is the ruling o f the District

Court o f the Eastern District o f North Carolina in the case

o f Eaton et al v. Board of Managers et al, 164 F. Supp. 191,

which was unanimously affirmed by this Court o f Appeals,

261 F. 2d 521 (1958), cert, denied, 359 U.S. 984. In this

case, this Court held that the charter o f this same Hospital

was granted by the General Assembly o f North Carolina pur

suant to a private act creating the corporation. (Appellees’

Appendix, P. la ) with its own Board o f Managers, with full

power and authority to set forth its own rules and regula

tions, and no public funds were received by the corporation

except approximately 4 % % o f its total revenue, which was

paid by the County pursuant to contract for services per

formed. Because o f this it was held that defendant Hospital

was a private corporation and its act o f alleged discrimina

tion in denying the admittance o f Negro doctors to its staff

was not action o f the State and did not give the Federal

Court jurisdiction. This was held, notwithstanding the fact

that the City and County had a reverter in one-half o f the

5

Hospital land should it fail to use it, and that in the past the

City and County had made contributions o f funds to it under

laws which were subsequently declared unconstitutional.

It is defendants’ position that on the facts alleged in this

case, and in the previous case, the Hospital has been ad

judged to be a private corporation and that this Court con

sequently has no jurisdiction over the present dispute, which

is similar in nature to the previous dispute.

In order to compare the two suits let us first discuss the

parties and the relief asked. In the former suit the parties

were the three Negro doctors, who are also plaintiffs in this

suit. In the present suit two individual plaintiffs have been

added who have asked for the right to be treated on a non-

segregated basis in the Hospital. This, however, does not add

any additional facts to show that the Hospital is any less a

private corporation. If the Hospital is a private corporation,

the individual plaintiffs have no more right than the profes

sional plaintiffs, for a private corporation has the right to

serve whomsoever it wishes under the terms and conditions

that it sets forth.

W e conclude then that the addition o f the two individual

plaintiffs does not change the basic adjudication that the cor

poration is a private corporation and that the Federal Court

does not have jurisdiction.

Since the Hospital has already been adjudged a private cor

poration it is the contention o f the defendants that this is not

open to review by the Court at this time. It is further con

tended by the defendants that the allegations in the instant

complaint were all included in the previous complaint, inso

far as they allege any activity, or control which would make

the corporation a public corporation. A review o f these alle

gations is as follows:

(a) In paragraph V I o f the complaint (Appellants’ A p

pendix 6a) the Corporate Charter is alleged in detail and

6

the various acts which have supplemented the charter and

provided for contributions to the Hospital are referred to.

The allegations relative to the charter were in the prior com

plaint at paragraph 8 (Appellants’ Appendix 74a) and ref

erences were made in paragraphs 10 and 11 o f the prior com

plaint (Appellants’ Appendix 75a) to the contributions

which were made by the City and County under the legisla

tion enacted after the Charter. All o f these acts appeared in

the record by stipulation in the former action, and being

Private and Public laws were before the Court as a part o f

the law o f North Carolina. The effect o f these acts and con

tributions by the City and County are fully discussed in both

the District Court and Circuit Court opinions, and it was

decided on the basis o f Board of Managers v. City of Wil

mington, 237 N .C. 179 (1953) (referred to in the instant

complaint paragraph V I-7 Appellants’ Appendix 9a), that

these contributions were unconstitutional, and that no con

tributions other than the per diem contract payments for

the treatment o f indigents, were being made at the time the

suit was commenced. This Court then decided that the prior

contributions did not make the Hospital a public corpora

tion, nor did the per diem payments under contract change

its private nature. Eaton v. Hospital, supra.

(b ) The allegations o f paragraph V II-A (Appellants’

Appendix 9a) relative to the property o f the Hospital were

set out in paragraph 13 and 14 o f the prior complaint. (A p

pellants’ Appendix 76a ).

(c ) The allegations o f paragraph VII B & C (Appellants’

Appendix 10a) relative to James Walker were alleged in

paragraphs 12, 13, and 14 o f the prior complaint, (Appel

lants’ Appendix (7 6 a ). In fact the W ill o f James Walker was

attached to the complaint in the previous action and was a

part o f the record therein.

7

(d ) The allegations o f paragraph VII D (Appellants’ A p

pendix 10a) referring to the conveyance o f property to the

Hospital in trust were referred to in paragraph 14 o f the

prior complaint (Appellants’ Appendix 76a). These were

fully discussed in each o f the prior opinions.

(e) The allegations o f paragraph VII o f the complaint

(sub-paragraph E and E -l Appellants’ Appendix 10a) rela

tive to the exemption from the payment o f City and County

taxes were alleged in the prior complaint at paragraphs 10

and 11 (Appellants’ Appendix 75a) and although not dis

cussed by the Court in its opinions, were fully argued both

in the lower courts and in the petition for W rit o f Certiorari.

(Appellees’ Appendix 6a). Apparently the Court did not

feel that these allegations were o f enough significance to dis

cuss them.

( f ) Paragraph VII-F o f the instant complaint (Appel

lants’ Appendix 10a) sets forth other alleged indicia o f con

tinuing control and influence o f the City and the County

over the Hospital. They refer to the City as a self-insurer

making payments to the Hospital for services rendered in

treating workmen’s compensation cases. This is no different

from the per diem contract between the City and the Coun

ty for treatment o f the indigent which was fully covered in

the prior case, and the affidavit o f Robert Martin (Appel

lants’ Appendix 58a) shows this amounts to less than $1600

per year.

(g ) Paragraph VII-F-2 refers to the contributions o f the

City and County which were made under the previous acts

and were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court o f

North Carolina in Board of Managers v. City, supra. These

contributions for capital improvement are no different from

the contributions for annual support and maintenance, and

without the elements o f control necessary to make defendant

8

a public corporation do not change the nature o f the re

cipient.

(h) Likewise the allegations o f paragraph VII F-3 (A p

pellants’ Appendix 11a) do not change the nature of the

recipient, and these contributions by the State and Federal

government were set forth in the allegations o f paragraph 12

o f the former complaint (Appellants’ Appendix 11a and

76a). The statute under which the plaintiffs allege jurisdic

tion refers to State action and not Federal action. There is

no allegation that the defendant is an agency o f the Federal

government by reason o f the fact that contributions were

made to the State and turned over to the Hospital. Such an

allegation would be absurd, as is the implication desired by

the plaintiffs.

(i) W ith regard to paragraph VII-F -4 (Appellants’ A p

pendix 11a) the prior complaint in paragraph 12 (Appel

lants’ Appendix 76a) referred to the exercise o f the right o f

eminent domain by the Hospital, and this was discussed in

all o f the briefs. It was clearly before the Court in the form

er case, and, in fact, on the petition for W rit o f Certiorari to

the Supreme Court the Petitioners, present plaintiffs in this

action, through counsel appearing here, filed the record in

the suit referred to in paragraph F-4 in the Supreme Court

o f the United States. (Appellees’ Appendix 14a). The Court

apparently gave this no significance in the light o f the cases

which hold that the exercise o f eminent domain does not

make a corporation an agency o f the State.

( j) In Paragraph VII-F-5 (Appellants’ Appendix 12a)

the plaintiffs refer to the allegations in the suit o f Board of

Managers v. City, 237 N.C. 139, supra, wherein the Board o f

Managers alleged it was a public body. The Supreme Court

o f North Carolina not only held that it was not a public

body, but that the City and County could not make contri

9

butions to it for its support and maintenance, and the effect

o f this case was fully discussed in, and was a basis for the

prior opinions.

(k ) In Paragraph VIII-4-B o f the complaint it is alleged

that the Hospital is a public utility carrying out the func

tions o f the City and County. It was clearly held, however,

that the operation o f a hospital was not a necessary expense

o f government or a governmental function in Board of Man

agers v. City, supra, at page 191. This opinion was recognized

as controlling on the former appeal for there is no control or

right to control, and thus defendant cannot be carrying out

a City or County function.

Judge Butler in his opinion below, after reviewing the com

plaints in both actions, concluded that they were substantial

ly the same, except that there were three possible new allega

tions: the workmen’s compensation payments by the City,

the licensing o f the hospital by the State, and that the Hos

pital was superior to other hospitals in the area (Appellants’

Appendix 66a).

He properly concluded that the compensation payments

were not unlike the per diem payments for the indigent

which had been held by this Court not to be a sufficient ele

ment o f control to create state action.

Likewise he properly disposed o f the other two elements

after careful consideration thereof (Appellants’ Appendix

67a). Since these are discussed in the other part o f this brief

they will not be discussed here.

The defendants invite the Court to carefully consider the

complaint and motions in the prior action, to carefully con

sider the judgment o f the District Court in the prior case, to

carefully consider the briefs and appendices filed in the

Fourth Circuit Court o f Appeals, to carefully consider Judge

Soper’s able opinion in the prior case, which, based on the

10

precedents set forth in the Fourth Circuit, held that the

Board o f Managers o f James Walker Memorial Hospital is a

private, not a public, corporation. When the allegations o f the

present case are applied to the law set forth in the prior case,

we respectfully submit that it can only be concluded that

nothing is added to that which was set forth in the prior case

with regard to the defendant’s being a public corporation,

and that consequently there can be no jurisdiction in this

Court under 28 U.S.C.A. 1343 (3 ) .

Point No. 2

THERE HAS BEEN NO CHANGE IN THE LAW SINCE

THE DECISION IN THE PRIOR EATON CASE JUSTIFYING

A CHANGE IN RESULT.

1. Plaintiffs rely entirely in asserting the jurisdictional

right here on Burton v. Wilmington Barking Authority, 365

U.S. 715. W e note immediately that Burton, supra, recog

nizes the very principal that the Eaton case was decided on

at 365 U.S. 722: "Individual invasion o f individual rights is

not the subject-matter o f the [Fourteenth] Amendment,” ;

and further: "and that private conduct abridging individual

rights does no violence to the Equal Protection Clause . .

This is clearly the theory o f Judge Soper’s opinion in Eaton,

supra.

The Court in Burton further limits its holding to the facts

in the Btirton case, and specifically states that Burton is not

authority for any state o f facts other than those in Burton.

A t 365 U.S. 725, the Court states as follows:

Because readily applicable formulae may not be fashioned, the con

clusions drawn from the facts and circumstances of this record are

by no means declared as universal truths on the basis o f which every

state leasing agreement is to be tested. Owing to the very "largeness”

of government, a multitude of relationships might appear to some

11

to fall within the Amendment’s embrace, but that, it must be re

membered, can be determined only if the framework of the peculiar

facts or circumstances present. Therefore respondents’ prophecy of

nigh universal application of a constitutional precept so peculiarly

dependent for its invocation upon appropriate facts fails to take into

account “ Differences in circumstances [which] beget appropriate

differences in law,” Whitney v. State Tax Com. 309 U.S. 530, 542,

84 L. ed 909, 915, 60 S. Ct. 635. Specifically defining the limits of

our inquiry, what we hold today is that when a State leases public

property in the manner and for the purpose shown to have been the

case here, the proscriptions of the Fourteenth Amendment must be

complied with by the lessee as certainly as though they were binding

covenants written into the agreement itself.

Neither the purpose nor the manner is the same in the instant

case. W e submit then that there is no fundamental change

in the law as a result o f Burton; it merely applied the same

law which was applied in Eaton to the facts in the Burton

case.

In carefully reading the Burton case we find three very

significant facts which were and are in no way present in

Eaton.

A. The Parking Authority o f the City o f Wilmington was

created by a provision o f the Delaware Code which created

it "A public body, corporate and politic, exercising public

powers of the State as an agency thereof.” P. 717 (Emphasis

supplied).

B. The lease between the Parking Authority and Eagle

provided that lessee would "occupy and use the leased prem

ises in accordance with all applicable laws, statutes, ordin

ances and rules and regulations o f any Federal, State or mu

nicipal authority.” P. 720.

C. The leased property was dedicated to "public uses” in

performance o f the Authority’s "essential governmental

12

functions” and was found to be "a physically integral and

indeed, indispensable part o f the state’s plan to operate its

project as a self-sustaining unit.” P. 723-725.

Compare this with Eaton where the charter o f the corpora

tion, Private Laws o f North Carolina, 1901, Chapter 12

(Appellees’ Appendix P. la ) specifically provided that

the Hospital was created as a corporation for the purpose of

removing it from the vicissitudes which generally result when

such an institution is left in the control o f local municipal

authorities. Compare this with Eaton where Eaton was de

cided on the basis o f the North Carolina Court decision in

Board of Managers v. City of Wilmington, 237 N .C. 179

(1953), which clearly held that the Hospital was not exercis

ing public powers o f the City or the County, and that neither

City nor County could provide revenues for its operation.

Hence, if the property reverted back to the City and County

they could not operate it. It could only be operated, if

operated at all, by the independent private corporation

created for that express purpose.

W e say that these differences are o f the greatest signific

ance. Plaintiffs argue that the case should be reconsidered

under the rule in Burton with regard to the variety o f rela

tionships which exist between the Hospital and the Govern

mental bodies. W e concede that some o f the relationships set

out in Burton exist with regard to the Hospital, but these

relationships must be considered in the light o f the principal

objective o f the W ilmington Parking Authority, which was

created to exercise public powers and to be an agency o f the

State, and the lease to Eagle which was integral to carrying

out this purpose; whereas the Hospital was created to remove

it from the control o f the City and County, and could in no

sense be considered carrying out a public power or purpose.

In addition, in Burton it appears at 365 U.S. 723, that the

cost o f land acquisition, construction and maintenance were

13

defrayed from donations by the City; and at 724, that upkeep

and maintenance o f the building including necessary repairs

were the responsibility o f the Authority and were payable

from public funds. Although there is some allegation in the

instant complaint o f donations and payments made prior to

the decision in the suit o f Board of Managers v. City of Wil

mington, 237 N .C. 179 (1953), the only allegations o f the

payment o f funds or donations existing at the time the in

stant suit was brought, or at the time o f Eaton, supra, are the

allegations relative to payments by the County under con

tract, the payments by the City under Workmen’s Compen

sation, and the general allegation o f exemption from City and

County taxes. The first two items are shown to be insignifi

cant by the affidavit o f the Director o f the Hospital (Appel

lants’ Appendix 58a), and the latter is shown to be insignifi

cant in the argument relating to it in this brief. It will be

noted that the total of all o f these payments is less than 4 % %

o f defendants’ gross revenues. But here again these allegations

must be considered in the light o f the actual charter o f the

Hospital; and the significance o f these items in Burton, supra,

must be considered in the light o f the fact that the Parking

Authority was created to exercise "public powers o f the

State as an agency thereof,” the lease to Eagle being inci

dental to doing this.

Likewise we feel that the dicta o f Judge Tuttle in Hamp

ton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (C .C.A. 5th,

1962), referred to on Page 16 o f plaintiffs’ brief, does not add

anything to plaintiffs’ position, for certainly they do not

argue that this Court is controlled by dicta in a decision o f

the Fifth Circuit. N or do we agree that this dicta casts doubt

on the authority o f Eaton, where plaintiffs have brought a

suit alleging substantially the same facts which were alleged

in Eaton.

14

W e note in Boman v. Birmingham Bus Company, 280 F.

2d 531 (C .C .A . 5th, 1960), also decided by Judge Tuttle,

that in referring to Eaton at page 5 3 5 o f the opinion, he states

that there is nothing in Eaton which is inconsistent with his

decision in the Boman case, clearly recognizing that each case

must be decided on its own facts as did the Supreme Court in

Burton, supra. W e respectfully submit that this Court should

not go to the Fifth Circuit for an interpretation o f the con

trolling decision which already exists in the Fourth Circuit,

for Judge Tuttle in the Boman case clearly recognizes the

rule that "the action inhibited by the first section o f the

Fourteenth Amendment is only such action as may fairly be

said to be that o f the State’s . . He thus recognizes in

Boman that the facts o f the Eaton case did not disclose State

action, and apparently his comment set out on page 16 o f

Appellants’ Brief in Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, supra,

was an attempt to justify his distinguishing the Eaton case

when he decided the Boman case; this certainly cannot be

considered by this Court as indicating that the Eaton case, as

previously decided, is erroneous.

Likewise, we feel that the other cases cited in plaintiffs’

brief do not change the fundamental holding o f the previous

Eaton case that the Hospital is not an agency o f the State.

2. W e feel that the comparison o f the Burton case with

the Eaton case as set out in Paragraph II o f plaintiffs’ brief,

page 18, is also without merit.

The Burton case may have explicitly rejected the single

factor test with regard to whether or not the action o f the

individual became State action, but on the other hand the

Eaton case was not decided on the single factor test. The al

legations o f the previous case which are fully reviewed under

Point No. 1 show that plaintiffs then were not relying on the

single factor test. They alleged every allegation in the prev

ious case which they allege now, and based on the previous

15

allegations the Court held that there was no jurisdiction. W e

concede that the single factor test did not exist in the Burton

case, and did not exist at the time o f the Eaton case. W e say,

however, that the factors relied on in the Eaton case, which

removed the Hospital from the control o f the City and the

County, still exist at the present time, and no new elements

have been brought out which change this; thus its action is

still individual action and not subject to a suit in Federal

Court.

3. W ith regard to the other arguments in paragraph 2 o f

plaintiffs’ brief, for the convenience o f the Court, we will

discuss each separately.

A. Financial Contributions for Capital Construction.

Plaintiffs contend here that the contributions for capital

construction were not considered in the prior appeal. They

admit that the allegations o f the former complaint were

sufficient to cover the contributions from the Federal G ov

ernment for capital improvement, and by the City and

County for capital construction. In the instant complaint

they have these same allegations but have expanded them to

set out the evidence which they presumably would offer to

support them.

W e are satisfied that under the general allegations o f the

former complaint that the allegations were sufficient to sup

port the fact o f these contributions having been made. W e

are also satisfied that Judge Soper in the opinion on the

former appeal considered these allegations. In Eaton v. Board

of Managers, 261 F. 2d 521 (C .C .A . 4th, 1958), at page

525 Judge Soper specifically held that the Hospital ceased

to be a public agency in 1901 when the Charter creating the

Hospital was enacted and the property passed from the con

16

trol o f the City and County to the new Board o f Managers

created in that year. He stated as follows:

It would seem from the evidence that the Hospital then ceased to

be a public agency, although in subsequent years until 1951 it re

ceived certain financial support from the City and County, the

amount of which the record before us does not reveal. Any doubt

on this point vanished in 1952 and 195 3, when annual appropria

tions came to an end as a result of the decision of the Supreme Court

o f the State, and patients sent to the Hospital by the local govern

ments were treated and paid for under contract on a per diem basis.

It is beyond dispute that from that time on the civic authorities

have had no share in the operation of the Hospital and the Board of

Managers have been in full control.

It will be noted that the type o f appropriation which Judge

Soper referred to was not limited, and the decision by the

Supreme Court o f North Carolina would include as uncon

stitutional appropriations for capital expenditures as well as

those for annual support and maintenance; regardless of

source they did not make the Hospital a State agency under

Judge Soper’s ruling.

In addition, in the Petition for W rit o f Certiorari filed by

these plaintiffs in the Supreme Court o f the United States

(Appellees’ Appendix P. 15a) these same arguments were

presented, and this same evidence set out as an example o f

the evidence which would have been presented at the trial of

the former case had the case been sent back by the Supreme

Court for trial on its merits. Since this was presented to the

Supreme Court, the only conclusion which can be made is

that the Court in denying Certiorari agreed with Judge

Soper’s analysis o f the history o f the defendant in that it

was a private corporation, and that the contributions by the

Federal and City and County Governments, for whatever

purpose, did not make it a public corporation.

17

Plaintiffs refer to 42 U.S.C. sec. 1533 which provides that

in the allocation o f funds for public works, in determining

the need therefor, that there shall be no discrimination on

account o f race or color. This A ct further specifically pro

vides [42 U.S.C. 1533 (4) (c ) ] that no department or

agency o f the United States shall have any control over the

operation o f any hospital to which such grants were made,

and that no condition shall be placed on any grant or con

tribution to a hospital to "prescribe or affect its administra

tion, personnel, or operation.” The Statute is clear that the

purpose was to prevent any discrimination being used in de

termining the need for a hospital facility, but that once the

need was determined that the United States Government did

not wish to exercise any control over its operation including

the hiring o f its personnel. This would clearly include the

selection o f the staff o f the hospital.

B. Regulation and Licensing'.

Plaintiffs argue here that another factor not considered by

the Court in E aton, supra, was the North Carolina Hospital

Licensure Act, N.C.G.S. sec. 131-126 et seq. W e feel that

the licensure o f the Hospital by the State o f North Carolina

could not make it an agency o f the State.

The two sections o f the North Carolina General Statutes

which are apparently referred to are short and read as fo l

lows:

131-126.3 Licensure. After July 1st, 1947, no person or govern

mental unit, acting severally or jointly with any other person or

governmental unit shall establish, conduct or maintain a hospital in

this State without a license. (1947, c. 933, s. 6.)

131-126.4. Application for license. Licenses shall be obtained from

the Commission. Applications shall be upon such forms and shall

contain such information as the said Commission may reasonably re

18

quire, which may include affirmative evidence o f ability to comply

with such reasonable standards, rules and regulations as may be law

fully prescribed hereunder. (1947, c. 933, s.6; 1949, c. 920, s. 3.)

It is apparent that these are regulatory sections, and that they

were enacted for the purpose o f protecting the health, morals

and safety o f the citizens o f North Carolina as are the regu

lations issued thereunder. It is further apparent that the

phrase "no person or governmental unit” as set out in the

Statute, become meaningless if a "person” becomes a "g ov

ernmental unit” through the mere fact o f licensure; and it

is difficult to believe that it can be seriously contended that

the mere act o f licensing a private institution to carry on its

private operations will cause that private institution to be

come a governmental agency. Many, if not most, o f the ac

tivities o f the individual are subject to regulation by govern

ment in this modern era, but the State does not thereby

adopt, or attempt to control, all o f the activities o f the in

dividual performed within the scope o f the license granted;

it only controls where health, morals and safety are involved.

The reference by plaintiffs to Boman v. Birmingham Tran-

sit Company, 280 F. 2d 131 (C .C.A. 5th, 1960), is not in

point, for the license there granted was for the exclusive

right to transport persons within the City o f Birmingham on

the public streets o f the City o f Birmingham. The license re

ferred to by the plaintiffs in this case is a license which can

be issued to any hospital, and the regulations set out under

the act are no more than the regulations which are set out by

the Boards o f Health in the State to require individuals to

maintain a certain standard o f cleanliness in and around their

premises. The only difference being that this act creates a

higher standard which must be maintained where persons

with disease are being treated.

The doctors who complain to this Court in this case, and

the lawyers who represent them here, are all required to be

19

licensed by the State, (N orth Carolina General Statutes 90-

18; 90-29; 8 4 -4 ); they are also ruled by certain ethical

standards and regulations set up by the respective licensing

Boards; but they would presumably concede that they do not

thereby become governmental agents in the practice o f their

professions. It might also be pointed out •— to reduce the

absurd to further absurdity — that every automobile in

North Carolina is required to bear, and every driver to carry,

a license from the State, (N orth Carolina General Statutes

20-50; 20 -7 ), but it could hardly be suggested that every

driver motoring along the streets and highways o f North

Carolina is thus constituted an agent o f the State performing

governmental functions.

C. Tax Exemption.

Plaintiffs argue that because the question o f tax exemption

was not mentioned in the opinion o f the District Court or in

the opinion o f this Court in the former appeal, that this in

dicates that the matter was not considered by either Court in

passing on the matter. They cited then, and they cite now,

no case which holds that tax exemption when given to a

private charitable hospital makes that hospital an agency of

the State, and gives the State control over its operating func

tions. The Supreme Court has not gone this far, and we sub

mit that the statement in Burton v. Wilmington Barking Au

thority, 365 U.S. 715, which is referred to in plaintiffs’ brief,

does not extend the rule this far, since it expressly holds that

the Parking Authority was a "government agency.” The fact

that it was tax exempt is insignificant in the light o f the fact

that it was expressly created an agency o f the government.

Such is not true with regard to defendant Hospital.

Assuming for the purpose o f this appeal that the tax

exemption given by the City and County amounts to $50,-

000 per year as argued by plaintiffs, this is only 2.5% o f the

20

gross annual revenues o f the Hospital, and is certainly in

significant in regard to the total receipts o f the Hospital and

the size o f its operation.

D. Eminent Domain.

The exercise o f the power o f eminent domain by the de

fendant Hospital was admittedly alleged in the former com

plaint. Here again plaintiffs cite no case law which creates a

corporation which is given the power o f eminent domain an

agency o f the State. In the Petition for W rit o f Certiorari to

the Supreme Court in the former case (Appellees’ Appendix

P. 14a) plaintiffs filed a copy o f these very condemnation

proceedings with the Court, and yet the Court did not feel

that the matter was o f sufficient importance to grant the

Writ.

The fact that the Hospital has exercised the right o f emi

nent domain does not make it an agency of the State. It was

held by the Supreme Court in Strickley vs. Highland Boy

Gold Mining Company, 200 U.S. 527, that the right of emi

nent domain may be given to private corporations as well as

public corporations. Justice Holmes in deciding the case re

fers to Clark v. Nash, 198 U.S. 361, at 200 U.S. 531 as

follows:

In discussing what constitutes a public use, it recognized the in

adequacy of use by the general public as a universal test. While em

phasizing the great caution necessary to be shown, it proved that

there might be exceptional times and places in which the very

foundations o f public welfare could not be laid without requiring

concessions from individuals to each other upon due compensation,

which, under other circumstances, would be left wholly to voluntary

consent. In such unusual cases there is nothing in the Fourteenth

Amendment which prevents a state from requiring such concession.

If the Fourteenth Amendment does not prevent the states

from giving the right o f eminent domain to a private corpo

21

ration, the fact that such private corporation has exercised

the right o f eminent domain, properly given it, does not con

stitute the private corporation an agency o f the State.

The same contention made here was made in Dorsey vs.

Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 299 N .Y . 512, 87 N.E. 2d

541, cert, denied, 339 U.S. 981, where tax exemption and

power o f eminent domain were given a housing corporation.

In this case the Court o f Appeals o f New York State held

that "tax exemption and power o f eminent domain are

freely given to many organizations which necessarily limit

their benefits to a restricted group. It has not yet been held

that the recipients are subject to the restraints o f the Four

teenth Amendment.” 87 N.E. 2d 541 at 5 51. This reasoning

applies in the instant case, for if the State o f North Carolina

saw fit to give this private corporation the right o f eminent

domain in order to expand its facilities to take care o f the

sick and afflicted o f New Hanover County, such was not in

consistent with its being a private corporation, and it did not

thereby create it an agency o f the State.

E. Financial Contribution for Hospital Operation.

The effect o f the contributions to the Hospital prior to

1951 and the payments to the Hospital since 1951 under the

contract based on the per diem cost o f treatment o f welfare

patients, was fully presented to the Court in the former

action. Suffice it to say, that since the decision in Board of

Managers v. City of Wilmington, supra, and at the time o f

the application o f the plaintiffs for admission to the Hospital,

neither the City o f Wilmington nor the County o f New

Hanover had the right to use one dime o f the taxpayers’

money to support, maintain, or operate the Hospital other

than the per diem payments under contract for services ren

dered. Certainly the payments by a State Agency to a private

corporation under contract for services rendered does not

constitute the recipient an agency o f the State. This would

22

be true regardless o f the amount paid the agency, but in the

instant case it will be noted that the revenues presently do

not exceed 2% o f the gross income o f the Hospital. (A p

pellants’ Appendix, P. 58a).

T o carry plain tiffs’ argument to its illogical and ultimate

conclusion would require this Court to say that each time a

municipality enters into a contract for services with a pri

vate individual, that it was placing its power, property, and

prestige behind that individual so as to create that individual

an agency o f the State, and subject to the restrictions o f the

Fourteenth Amendment. If this were done the Government

would indeed become a many-armed thing, and the Federal

Courts would become nothing more than a sounding board

for innumerable individual disputes with no sound basis for

Federal jurisdiction.

23

C O N C L U S I O N

In conclusion, we submit that the defendant Hospital at

the present time is an individual, private corporation as it

was at the time o f Eaton v. Board of Managers, supra. W e

submit that this decision is controlling and that the law as

reflected in Burton v .Wilmington Barking Authority, supra,

is clearly distinguishable.

W e further respectfully submit that the operation o f the

internal affairs o f the Hospital with regard to the qualifica

tions for membership on its professional staff is one over

which the Federal Courts should be reluctant to take jurisdic

tion, since control o f matters o f public health, morals and

safety have always been expressly reserved to the states. A

decision as far reaching as that requested by the plaintiffs

herein would create the Federal Courts a body to sit as referee

in the administration o f the internal, personnel, and other

affairs o f all private charitable hospitals. Such a result should

not come about. The Judgment below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

C. D. H ogue, Jr.

W illiam L. H ill II

R onald D. R owe

608 Carolina Power & Light Building

Wilmington, North Carolina

Counsel for Defendant Appellees

A P P E N D I X

la

PRIV ATE LAW S OF N O R T H C A R O L IN A — 1901

CH A PTE R 12

An act to provide for the Government o f the "James Walker

Memorial Hospital o f the City o f Wilmington,

North Carolina,”

Whereas, through the munificent liberality o f Mr. James

Walker, o f the City o f Wilmington, N . C., and the County

o f New Hanover, the said City and County have been pro

vided with a substantial modern hospital for the mainte

nance and medical care o f sick and infirm poor persons who

may from time to time become chargeable to the charity o f

the said city and county, and for other persons who may

be admitted; and,

W HEREAS, it is desirable that the management o f said

hospital should be removed as far as possible from the vicis

situdes which generally result when such an institution is left

entirely in the control o f local municipal authorities subject

to changing political conditions and its efficiency in sound

degree thereby crippled; and

W HEREAS, it is also desirable that suitable provisions

should also be made for the permanent maintenance o f the

hospital by said City and County, therefore, The General As

sembly o f North Carolina do enact:

Section I. That said hospital and the dispensary connected

therewith shall be under the general supervision and control

o f a board o f nine managers who are hereby created a body

politic and Corporate for the term o f thirty years, under the

name and style o f the "Board o f Managers o f the James

Walker Memorial Hospital o f the City o f Wilmington, North

Carolina” and by that name shall have succession and a com

mon seal, sue and be sued; plead and be interpleaded, and

2a

Control of hospital Corporate powers

Managers created a body politic: Board how selected

Corporate name RESTRICTION:

have all the rights and privileges conferred upon such cor

porations. The said Board o f Managers shall be composed o f

three members to be elected by the Board o f Commissioners

o f N ew Hanover County, two members to be elected by the

Board o f Aldermen o f the City o f Wilmington, North Caro

lina, and four members to be selected by Mr. James Walker.

The members o f the said Board o f Managers who are to be

elected by the Board o f County Commissioners, and the

Board o f Aldermen shall be elected at the first regular month

ly meeting o f the respective bodies held in the month o f

March, one thousand nine hundred and one, and no one o f

said members shall be from either the Board o f Aldermen or

the Board o f County Commissioners. The members to be se

lected by Mr. James Walker, shall enter upon the discharge

o f their duties as soon as the hospital now in course o f erec

tion shall have been completed and turned over to the Board

o f Aldermen o f the City o f Wilmington and the Board o f

Commissioners o f the County o f New Hanover, and formal

ly accepted by them, and shall then succeed to all powers and

duties o f "The Board o f Managers o f the City Hospital o f

Wilmington, North Carolina.”

Section II. The Board o f Managers shall hold their first

meeting on the day following their election. A t this meet

ing they shall decide by lot the term of office o f each mem

ber as follows: Three members shall be selected by lot whose

term o f office shall be two years; three members shall be

selected by lot whose term o f office shall be four years; and

three members shall be selected by lot whose term o f office

shall be six years A t all subsequent elections the term of

office shall be six years. Should any vacancy occur in the

board either by death or resignation, the remaining members

shall fill the vacancy, and the term of office o f the person

3a

When to enter upon discharge

of duties

Powers:

When to hold 1st meet:

Term of office of each, how decided:

Term of office:

Failure to attend meeting board may

declare membership void &

elect successor

Means of sustenance of hospital and

maintenance and medical care of

indigent sick and infirm provided

City & County appropriations con

trolled and disbursed by board

of managers

elected shall expire at the time the original member’s would

have expired. Should any member o f the Board o f Managers

fail to attend a meeting o f the board for a period o f six

months, the board may declare his membership void, and

proceed to fill this position by the election o f a successor for

his unexpired term. As the expiration o f the term of office

o f members, the remaining members o f the Board shall elect

their successors.

Section III. That for the purpose o f providing the proper

means for sustaining the said hospital, and for the mainte

nance and medical care o f all such sick and infirm poor per

sons as may from time to time be placed therein by the au

thority o f the said Board o f Managers, the Board o f Com

missioners o f N ew Hanover County shall annually provide

and set apart the sum o f four thousand eight hundred dollars,

and the Board o f Aldermen o f the City o f Wilmington shall

annually provide and set apart the sum o f three thousand two

hundred dollars, which said fund shall be placed in the hands

o f the said Board o f Managers to be paid out and disbursed,

under their direction, according to such rules, regulations and

orders as they may from time to time adopt.

Section IV. Should any portion o f the annual appropria

tions by the County o f New Hanover and City o f W ilming

ton remain unexpended on the first day o f March o f each

year, it shall be the duty o f the Board o f Managers to invest

such unexpended balance in bonds o f the City of Wilmington

or County o f New Hanover, or State o f North Carolina,

and such investment shall be known as a permanent fund.

4a

Unused portion of appropriations to Income, how used

be invested in City & County or When fund itself, used

State Bonds Transfer of bonds, how & when made

Bonds, how registered When & where board to meet &

organize

The bonds so purchased shall be registered in the name o f the

"Board o f Managers o f the James Walker Memorial Hospital

o f the City o f Wilmington, North Carolina.” The income

from said permanent fund may be used for the maintenance

o f the hospital, but no part o f the fund itself shall be used

except in case o f additional emergency, or for some perm

anent improvement or addition to the hospital. N o part o f

said fund shall be used as above provided, except by approval

o f two-thirds o f the entire membership o f the Board o f Man

agers and any transfer o f the bonds, in which said funds is

invested shall be made by the president and secretary o f the

board, only after such approval by two-thirds o f the entire

membership o f the Board o f Managers.

Section V. That the said Board o f Managers shall, as soon

after their election as may be practicable and advisable, con

vene in the office o f the County Commissioners of said Coun

ty, in the City o f Wilmington, on a day to be named by the

chairman o f the board o f County Commissioners if no day

has been selected as the first meeting o f the Board o f Man

agers, and shall then and there proceed to organize by the

election o f a president and such other officers as they may see

fit for the purpose o f carrying out the provisions o f this act,

and shall adopt such by-laws and regulations for their own

government and for the control and management o f said hos

pital and dispensary as they may deem right and proper. A

majority o f said Board o f Managers shall constitute a quorum,

with power to fix their times o f assembling to adopt, alter,

amend, or repeal their by-laws, rules and regulations, and

to do whatever, by law, the said Board o f Managers have

authority to do.

Plan of organization

By-laws

Quorum & Powers

5a

Board of Managers to report

Contents of Report

Conflicting laws repealed

Section VI. That the said Board o f Managers shall on the

first Monday in January in each and every year, make two

separate reports, one to the Board of County Commissioners

and the other to the Board o f Aldermen, which said reports

shall contain a full-time and accurate account o f the conduct

and management o f said hospital and dispensary, giving an

itemized account o f their receipts and disbursements, to

gether with the number, sex, race, age and disease o f all o c

cupants o f said hospital for the proceeding year.

Section VII. That so much o f Chapter 23 o f the laws of

1881, and all other laws as may conflict with this act are

hereby repealed.

Section VIII. That this act shall be in force from and

after the first day o f March, one thousand nine hundred

and one.

6 a

£§>uprm? Court o f ttjr llnitrb §tatro

October Term, 1958

No. 789

H u b e r t A. Ea t o n , et al.,

j"Petitioners,

Bo ard o f M a n a g e r s o f t h e Ja m e s W a l k e r M e m o r ia l

H o s p it a l , et al.,

Respondents.

------------—------- ------------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ o f certiorari issue to review

the judgment o f the United States Court o f Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit entered in the above - entitled case on

November 29, 1958.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion o f the Court o f Appeals is printed in the

appendix hereto, page la, infra, and is reported at 261 F. 2d

521. The opinion o f the District Court herein is reprinted

in the appendix at page 13 a, and is reported at 164 F.

Supp. 191.

Jurisdiction

The judgment o f the Court o f Appeals was entered on

November 29, 1958. By order o f the Chief Justice, time to

file petition for writ o f certiorari was extended to and in

cluding March 23, 1959. The jurisdiction o f this Court is in

voked under 28 U. S. C., §1254.

7a

Question Presented

Whether the complaint, which invoked the Fourteenth

Amendment right to be free from racial discrimination, and

which alleged substantial governmental support o f defendant

hospital, that it had been created by the City and County,

was governed by a governmentally created board, and had

other significant governmental contacts, was properly dis

missed under the Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure, where it

was admitted that plaintiffs, Negro physicians, were excluded

from practicing in said hospital solely because o f race, or

whether plaintiffs have stated a claim upon which relief can

be granted sufficient to allow presentation o f proof on the

merits.

Statement

The complaint in this case demanded declaratory judg

ment and injunction and posed the following question:

. . . whether the custom and practice o f the defen

dants in denying, on account o f race and color to plain

tiffs and other qualified Negro physicians similarly sit

uated the right to courtesy staff privileges, including

the right to treat their patients when they are admitted

to defendants hospital, the James Walker Memorial Hos-

pital, Wilmington, North Carolina, is unconstitutional

and void as being a violation to the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution o f the United States (App.

2) .*

The three plaintiffs herein are Negroes and physicians who

reside and practice in Wilmington, North Carolina. The de

fendants are the Board o f Managers o f the James Walker

Memorial Hospital, a body corporate under and by virtue of

the laws o f the State o f North Carolina and in the complaint

alleged to be a governmental instrumentality, the Secretary

* App. refers to petitioners’ appendix in the Court o f Appeals.

8a

o f the Board o f Managers o f said hospital, who as its chief

administrative officer has overall control and management

thereof, the City o f Wilmington, North Carolina, and the

County o f New Hanover in which that City is located.

The complaint sets forth the professional qualifications o f

plaintiffs, including their education, training and experience,

and that they have been denied, solely because o f race, the

right to treat their patients at the James Walker Memorial

Hospital (App. 3, 4 ) . It alleges certain contacts between the

hospital and various arms o f government, by virtue o f which

it is claimed that action o f the hospital is state action in the

sense that it is governed by the equal protection clause o f the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

These allegations, it may be noted at this point, are admitted

both by motions to dismiss (App. 10, 11, 13) and by stipula

tion. (App. 15).

In particular the allegations concerning state action con

sist o f the following:

1. "Defendants, including defendant Hospital, have ex

ercised the right o f eminent domain . . . for expansion and

maintenance o f the said Hospital” (App. 6 ) .

2. Defendants have received "large grants o f money from

the Federal Government for expansion and maintenance o f

the said Hospital” (App. 6 ).

3. That the hospital is on a tract o f land which was pur

chased by the County and City o f W ilmington in 1881

(App. 6, 5 5-57).

4. That the City and County held and used said hospital

under the W ill o f James Walker "as a hospital for the treat

ment o f the 'sick and afflicted’ ” (App. 6 ). The will directed

(App. 38-40) that the hospital be constructed by monies to

be derived from Mr. Walker’s estate "and after the comple

9 a

tion o f the said Hospital my said Executors are hereby direct

ed to deliver and turn over the same to the proper authorities

o f the City o f Wilmington and the County o f N ew Hanover,

State o f North Carolina, to be held and used by them and

their successors as a Hospital for the treatment o f the sick and

afflicted” (App. 39).

5. That the County o f W ilmington "did by deed transfer

the land upon which was situated the James Walker Memorial

Hospital to the Board o f Managers o f the James Walker

Memorial Hospital in trust for the benefit o f the said Coun

ty and City” (App. 7) by a deed requiring the County and

City " T o h a v e a n d T o h o l d the same in trust for the use

o f the Hospital aforesaid, so long as the same shall be used and

maintained as a Hospital for the benefit o f the County and

City aforesaid, and in case o f disuse or abandonment to revert

to the said County and City as their interest respectively

. . .” (App. 59-60).

6. That the board o f the hospital was constituted by state

statute, a majority o f its members to be selected by the Coun

ty and City, and that since its constitution it has been self

perpetuating (App. 33-34).

7. The City "has provided financial support for the said

James Walker Memorial Hospital by granting said Hospital

exemption from payment o f city taxes . . .” (App. 5 ).

8. The "C ity has for many years prior to 1951 made direct

annual contributions from its treasury for the support, main

tenance and operation o f said Hospital and that since the

year 1951, the said City has made per diem contribution to

said Hospital in payment o f services rendered certain resi

dents o f the City o f Wilmington, North Carolina” (App. 5).

9. "The County has provided financial support for the

James Walker Memorial Hospital by granting said hospital

exemption from payment o f County taxes . . .” (App. 6 ).

10a

10. The "County has for many years prior to 1951, made

direct annual contributions from its treasury for the support,

maintenance and operation o f the said hospital; and that

since the year 1951, the said County has made per diem con

tributions to said hospital in payment o f services rendered

certain residents o f the County o f New Hanover.” (App. 6).

As noted above, each o f the defendants filed a motion to

dismiss under Rule 12 (App. 10, 11, 13). The existence o f

certain statutes was stipulated by counsel for both sides and

a tabular list o f funds paid over by the County and City be

tween 1952 and 1957 was also stipulated as true. These funds

totaled about 4 % of the hospital’s income (App. 28) . It also

was stipulated that none o f the original members o f the board

were on the board at the time plaintiff applied (App. 15).

The Mayor submitted an affidavit relating that the city does

not contribute any financial support to the hospital but

charges it for water and sewerage (App. 17). Other affidavits

were submitted concerning City and County payments sub

sequent to 195 3 (Appee. 1, 2, 4 ) . *

Reviewing the facts and the law the District Court held on

defendants’ motion to dismiss under Rule 12 for lack o f fed

eral jurisdiction (App. 18) "that for the lack o f jurisdiction

the complaint must be dismissed . . (App. 30) . The

Court o f Appeals affirmed, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958).

* Appee. refers to respondents (appellee’s) appendix in the Court of

Appeals.

11a

REASONS FOR ALLOWANCE OF THE WRIT

I

Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure dismis

sal under Rule 12 was erroneous.

This case at this stage involves essentially a relatively nar

row issue: whether the district court should have granted the

motion "to dismiss under Rule 12 [o f the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure] for lack o f federal jurisdiction,” 164 F.

Supp. at 192. Petitioners contend that under the liberal pro

visions o f the Federal Rules they stated enough in their com

plaint to have permitted them to go to trial and make their

proof. As stated in Conley v. Gibson, 3 55 U. S. 41, it is "the

accepted rule that a complaint should not be dismissed for

failure to state a claim unless it appears beyond doubt that

the plaintiff can prove no set o f facts in support o f his claim

which would entitle him to relief.” 3 55 U. S. at 45-46. And

as stated further in that case "the Federal Rules o f Civil Pro

cedure do not require a claimant to set out in detail the facts

upon which he bases his claim. T o the contrary, all the Rules

require is 'a short and plain statement o f the claim’ that will

give the defendant fair notice o f what the plaintiff’s claim is

and the grounds upon which it rests.” Id. at 47. For " [t ]h e

Federal Rules reject the approach that pleading is a game o f

skill in which one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the

outcome and accept the principle that the purpose o f pleading

is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits.” Id. at 48.

N or should it matter as here that the motion to dismiss

particularly alleged lack o f jurisdiction. For jurisdiction, in

the sense that it was an issue here, was co-extensive with the

issue posed by the merits: There was no jurisdiction, it was

held, because the hospital in question was not a governmental

instrumentality. But whether the hospital was a governmental

instrumentality or not was the main substantive question in

12a

the case. The decision o f this question depended upon the na

ture and extent o f the hospital’s contacts with the State,1

something which could only be developed by the proof. Plain

tiffs submit they were not obligated to plead except in general

terms. And they should have been permitted, it is respectfully

submitted, to adduce detailed proof to substantiate their gen

eral allegations.

The general allegations which petitioner made were ade

quate to permit detailed material proof to be made at the

trial. For example, it should have been pertinent for petitioner

to present proof o f the extent to which and the manner in

which the hospital exercised the right o f eminent domain

(App. 6 ). Moreover, there is an allegation o f the complaint,

admitted for purposes o f the motion to dismiss, that defend

1 This Court, o f course, has not expressed any definitive formula con

cerning what constitutes state action under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The cases indicate that any given determination may depend upon a full

exposition of what constitutes the nexus between the alleged state instru

mentality, and the government proper. See e.g., American Communications

v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382, 401 (1950) (" . . . when authority derives in

part from Government’s thumb on the scales, the exercise of that power

by private persons becomes closely akin, in some respects, to its exercise by

Government itself.” And see Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946)

(company town; claim of free speech upheld against charge o f trespass);

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, 299 N . Y. 512, 87 N. E. 2nd 541 (1949)

(state aided urban redevelopment; insufficient state action) cert. den. 339

U. S. 981 (1950); Steele v. Louisville and N. R. R. Co., 323 U, S. 192

(1944) (Railway Labor A ct held to require fair representation, forbid

racial discrimination); Betts v. Easely, 161 Kan. 459, 169 P. 2d 831

(1946) (union held governmental entity); Williams v. United States, 341

U. S. 97 (1951) (private detective qualified as special police officer; state

action); Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956) (injunc

tion issued against county’s lessee); Clark, Charitable Trusts, the Four

teenth Amendment and the Will o f Stephen Girard, 66 Yale L. J. 979

(1957); Horowitz, The Misleading Search for "State Action” Under the

Fourteenth Amendment, 37 Calif. L. Rev. 208 (1957).

13a

ants have received large grants o f money from the federal

government for expansion and maintenance o f the said hos

pital (App. 6) . It is difficult to see how the motion to dismiss

could have been granted without knowing how much money

was given and in what manner and under what conditions. It

is noteworthy that neither o f the opinions below so much as

mentions the matter o f federal contribution.

It is further alleged that the City and County, by means o f

a reverter clause, require the Board o f Managers to maintain

the property as a hospital. This reverter clause, however, con

cerns only part o f the property and it would bear upon the

entire picture to know the fiscal significance o f this require -

ment and its meaning for the operation o f the hospital as a

whole. Moreover, it has been alleged that the County and

City have over the years provided financial support for said

hospital. It very well might make a difference for the ulti

mate result if the court knew how much o f said financial aid

was for capital construction which now is a part o f the hos

pital and how much was expended in day-to-day operation

and is, in a sense, no longer a part o f the hospital.

In short, on the motion to dismiss none o f these, nor any

other o f the multitude o f facts which might have been de

veloped upon a trial, were elicited. The purpose o f a complaint

is not to plead such details but to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted in support o f which such details may be

marshalled.

Petitioners here note certain public records which are only

part o f the evidence which may be produced in support o f

petitioner’s general allegations. These are referred to merely

as an example o f the injustice which is done to the notice

pleading concept o f the Federal Rules by cutting off proof

when a claim is well stated in general terms:

14a

1. The 1943-44 Annual Report o f the City o f W ilming

ton, North Carolina, states at page 30:2 3 4 *

James Walker Memorial Hospital

City’s Contribution $21,000

Located at Dickinson and Red Cross Streets, this gen

eral, nonprofit hospital serves the greater portion o f W il

mington’s white population as well as some o f the negro

population. A new addition, financed by federal funds

at a cost o f $508,000, was placed in service in March,

1944, to bring the total number o f beds available for

patients to 3 00.8

2. Moreover, in a Petition for Condemnation in the Su

perior Court o f New Hanover County, State o f North Caro

line, filed by the Board o f Managers o f said Hospital against

Kirby C. Sidbury and W ife on April 28, 1942 to condemn

land taken for said half-million dollar addition the Hospital

alleged that it was "a municipal corporation, a public body

and body corporate and politic . . .” Said petition for con

demnation was granted by final judgment in said Superior

Court on December 5, 1944, the judgment reciting that the

petitioner is a public body, a body corporate and politic

5>4

3. There is also a public record o f the fact that certain

costs for capital construction have been paid for by the City

and County in the Hospital’s complaint at page 6 o f the

Record o f Board of Managers of the James Walker Memorial

2 A copy of this Report is being deposited with this petition.

3 The original file concerning this federal grant is a public document,

now on microfilm, held by the Housing and Home Finance Agency,

Office of the Administrator, Records, Management Branch, F ¥ A Project

Docket No. 31-127.

4 A copy o f the Petition for Condemnation and the Final Judgment

are deposited along with this Petition.

15a

H ospita l o f W ilm in g ton v . C ity o f W ilm in g ton and N e w

H a n over C o u n ty , 237 N . C. 179, 74 S. E. 2d 749, to which

opinion the District Court (Appendix hereto, 19a) and the

Court o f Appeals (Appendix hereto, 4a) referred:

The North wing referred to above cost approximately

$100,000 all told, o f which the government contributed

$40,000 and the City o f W ilmington and the County o f

N ew Hanover paid, beginning the first o f the fiscal year

— the first o f July, 1937, — $10,000 each for three

years, making $60,000 all told, in addition to their regu

lar appropriations o f $15,000 each.

As stated above these references to public documents are

made solely for the purpose o f demonstrating part o f the

proof that would have been possible at a trial on the merits.

But notwithstanding petitioners’ substantial general allega

tions they were not permitted to go to such a trial.

On March 9, 1959, this Court handed down an order high

ly suggestive o f what should be a proper disposition o f this

cause. In passing on petition for writ o f certiorari in O liphant

v. B rotherhood o f L o co m o tiv e F irem en and E nginem en , 262

F. 2d 359 (6th Cir. 1958) this Court ruled that "in view o f

the abstract context in which the questions sought to be

raised are presented by this record, the petition for writ of

certiorari is denied.” 27 U. S. L. W k. 3249. In the O liphant

case, however, a "detailed record,” 265 F. 2d at 361, had been

made. Since plaintiffs therein had made such a record, which

nonetheless failed to remove the issues therein from the level

o f abstraction, no further proceedings were, it seems, war

ranted. In the instant case, however, petitioners are in an en

tirely converse position. Petitioners herein have n o t been p er

m itted to present the case in a manner sufficiently concrete to

pose the highly important constitutional questions involved.

Instead, petitioners have been dismissed on the basis o f an ab

stract record.

16a

II

The issue presented is one of the highest importance.

Discrimination against Negro physicians generally, and

especially by governmental institutions, raises a question o f

the gravest national importance. The problem is not one

merely o f the economic boycott practiced against such phy

sicians, as in this case where Negro patients are permitted to

use the hospital in question, but must accept a white physi

cian. As stated in a recent scholarly study o f the subject con

ducted under the auspices o f the Commonwealth Fund,

. . . medicine is not simply a matter o f individual pa

tients who seek out physicians according to whim or

convenience. Modern medicine is practiced in a compli

cated set o f institutions — ■ hospitals, clinics, public health

agencies. The physician’s career involves finding a place

in the system; the patient’s career as a consumer o f med

ical services likewise involves access to hospitals, clinics,

and other agencies, and his association with various so

cial groups — unions, employers, the armed forces,

schools — which connect him with health services and

insurance schemes. The system, operating at its best,

sends the patient on from his first contact to whatever

physicians or agencies can best handle his case; it also

allows the physician, as he develops, to move towards

those places in the system where he can best join his per