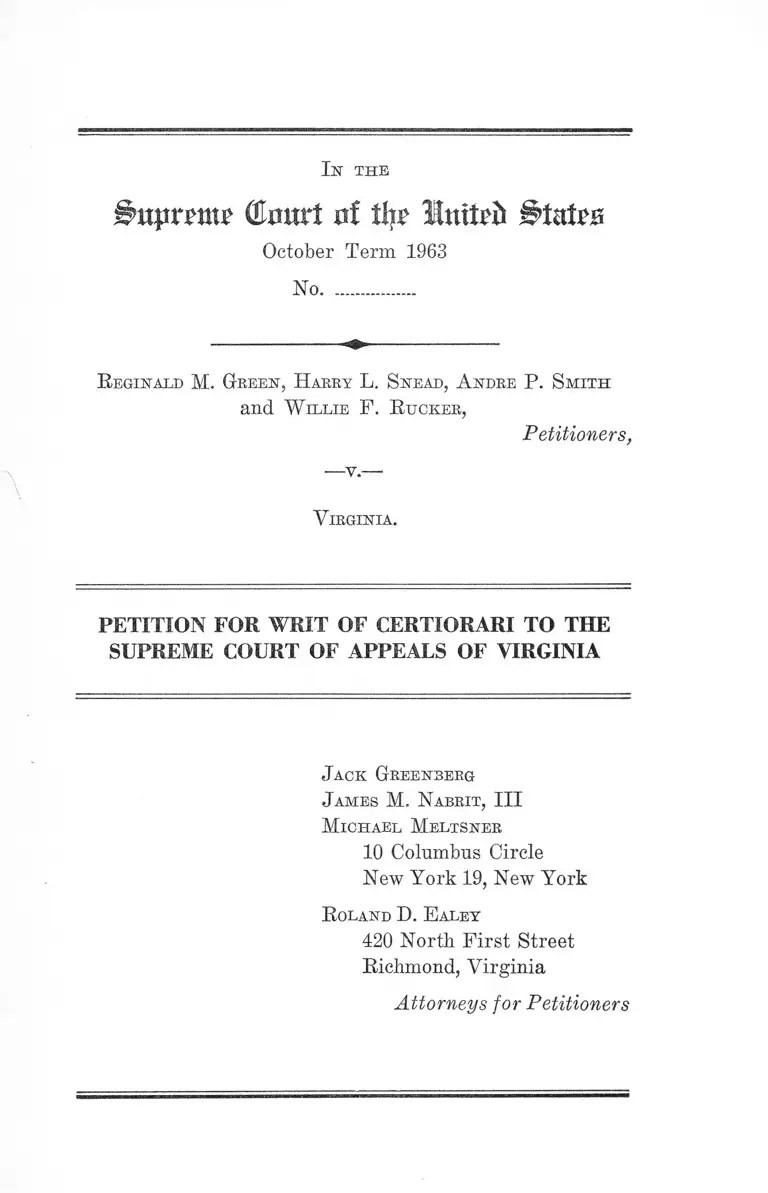

Green v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, 1963. 90564a4c-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/180807a8-c0bf-4837-a935-4f19c485899c/green-v-virginia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-appeals-of-virginia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Olmtrt of % lotted

October Term 1963

No................

R eginald M. Green, H arry L. Snead, A ndre P. Smith

and W illie P . R ucker,

Petitioners,

— y .— .

V irginia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R oland D. E aley

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions Below ........................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................... - .......... —-............................... 2

Questions Presented ................ - ................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement ................................................................... —- 5

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below ............................ -............................... .............. 7

Argument ........................................................................... 9

I. The State by Reason of Statutes Requiring

Segregation at “Any Place of . . . Public Assem

blage” Was Involved to a Significant Extent in

the Refusal to Serve Negro Petitioners .......... 9

II. Petitioners’ Convictions Enforce Racial Dis

crimination in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

S tates.................................................................... 12

Conclusion................................................................................. 15

A ppendix :

Denial of Writ of Error

(Reginald M. Green) ................................................ 17

Denial of Writ of Error

(Harry L. Snead) ................................................. 18

PAGE

Denial of Writ of Error

(Andre P. Smith) ..................................................

Denial of Writ of Error

(Willie F. Bucker) .................................................. 20

T able oe Cases :

Barr v. City of Columbia, No. 9, October Term, 1963 .... 12

Bell v. Maryland, No. 12, October Term, 1963 .............. 12

Blackwell v. Harrison, 221 F. Supp. 651 (E. D. Va.

1963) ......................................................... -............ . 9

Bouie v. City of Columbia, No. 10, October Term, 1963 .. 12

Brown v. City of Biehmond, —— Va. ----- , 132 S. E.

2d 495 .......................................... -......-....................... 9> 1°

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 ..................................... 12

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 IT. S. 2 0 ............................ 13

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 — ............. 11

Gantt y. Clemson Agricultural College of South Caro

lina, 320 F. 2d 611 (4th Cir. 1963) ......................... U

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157................................ 13

Griffin v. Maryland, No. 6, October Term, 1963 .......... 12

Henry v. Virginia, 374 H. S. 98 .......... ......................... 10

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61................................... 13

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 H. S. 267 .........................11,12

N A A CP v. Button, 371 H. S. 415.................................... 13

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1958) .... 13

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D.

Va. 1949)

11

PAGE

10

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .......... 10,11

Randolph v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 97 ................................ 10

Robinson v. Florida, No. 60, October Term, 1963 .......... 12

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................12,13

Thompson v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 99 ............................ 10

Trustee of Monroe Avenue Church of Christ v. Perkins,

334 IT. S. 813 .............................. ................................. 12

Williams v. Howard Johnson Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845 (4th Cir. 1959) .................................................. 10

Winters v. New York, 333 IT. S. 507................................ 11

Wood v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 100................................... 10

Statutes and Constitutional P rovisions I nvolved :

28 United States Code §1257(3) .......... ......................... 2

Constitution of Virginia §140 ....................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §18.1-173 ................................ 3, 5

Code of Virginia, 1960, §18.1-356 ................. 3, 4, 8, 9,10,13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §18.1-357 .........................8, 9,10,13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §20-54 .................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §22-221 ..................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §37-183 ..................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §38-1597 ................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §53-42 ..................................... . 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §56-196 .................................... 13

Code of Virginia, 1960, §56-326 ................................... 13

Ill

PAGE

Other A uthorities :

PAGE

Henkin, “Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised

Opinion,” 110 U. Pa. L. Rev. 473 (1962) ................. 14

Opinion of the State Attorney General to the Common

wealth Attorney of the City of Roanoke, Aug. 24,

1960, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1282 (1960) ..................... 10

I n t h e

(£mxt ni tljT BIuUb

October Term 1963

No................

R eginald M. Green, H arry L. Snead, A ndre P. Smith

and W illie P. R ucker,

Petitioners,

— Y,—

V irginia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia,

entered in the above-entitled cases October 17, 1963.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinions and judgments or orders of the Supreme

Court of Appeals are not reported and are set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra, pp. 17-20. The Hustings Court of

the City of Richmond entered judgment without opinion

(Tr. 33).1

1 Citations are to the typewritten transcript of proceedings in

the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia were entered October 17, 1963, infra, pp. 17-20.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of rights secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Were Negro sit-in demonstrators’ rights under the Four

teenth Amendment violated by conviction of trespass for

having remained at a restaurant counter in disregard of

orders to leave where:

(1) The decision not to serve petitioners was removed

from the sphere of private choice by state statutes requiring

racial segregation at “any place of . . . public assemblage” ;

(2) The trial court refused to permit petitioners to de

velop evidence of the reasons they were ordered to leave

the restaurant;

(3) The state has used its judicial machinery to enforce

racial discrimination, where the discrimination was caused

at least in part by a segregation custom substantially sup

ported by state laws, and where the state’s regime of laws

has failed to protect petitioners’ claim to equality by sub

ordinating it to a narrow and technical claim of property

right to racially discriminate in a place of public accommo

dation?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case, involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves Section 18.1-173 of the Code of

Virginia:

Trespass after having teen forbidden to do so.—If

any person shall without authority of law go upon or

remain upon the lands, buildings or premises of an

other, or any part, portion or area thereof, after having

been forbidden to do so, either orally or in writing, by

the owner, lessee, custodian or other person lawfully in

charge thereof, or after having been forbidden to do so

by a sign or signs posted on such lands, buildings,

premises or part, portion or area thereof at a place

or places where it or they may be reasonably seen, he

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon

conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not

more than one thousand dollars or by confinement in

jail not exceeding twelve months, or by both such fine

and imprisonment.

3. This case involves also §18.1-356 of the Code of Vir

ginia :

Duty to separate races at public assemblages.—Every

person, firm, institution or corporation operating, main

taining, keeping, conducting, sponsoring or permitting

any public hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture

show or any place of public entertainment or public

assemblage which is attended by both white and colored

persons shall separate the white race and the colored

race and shall set apart and designate in each such

public hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture showT

4

or place of public entertainment or public assemblage

certain seats therein to be occupied by white persons

and a portion thereof, or certain seats therein, to be

occupied by colored persons, and any such person, firm,

institution or corporation that shall fail, refuse or

neglect to comply with the provisions of this section

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction

thereof shall be fined not less than one hundred dollars

nor more than five hundred dollars for each offense.

4. This case involves also §18.1-356 of the Code of Vir

ginia :

Failure to take space assigned in pursuance of pre

ceding section.—Any person who fails, while in any

public hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture show

or place of public entertainment or public assemblage,

to take and occupy the seat or other space assigned to

them in pursuance of the provisions of the preceding

section by the manager, usher or other person in charge

of such public hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture

show or place of public entertainment or public assem

blage or whose duty is to take up tickets or collect the

admission from the guests therein, or who shall fail to

obey the request of such manager, usher or other per

son, as aforesaid, to change his seat from time to time

as occasion requires, in order that the preceding section

may be complied with, shall be deemed guilty of a

misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall be fined

not less than ten dollars nor more than twenty-five dol

lars for each offense. Furthermore such person may be

ejected from such public hall, theatre, opera house,

motion picture show or other place of public entertain

ment or public assemblage by any manager, usher or

ticket taker, or other person in charge of such public

5

hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture show or place

of public entertainment or public assemblage, or by a

police officer or any other conservator of the peace,

and if such person ejected shall have paid admission

into such public hall, theatre, opera house, motion pic

ture show or other place of public entertainment or

public assemblage, he shall not be entitled to a return

of any part of the same.

Statement

Petitioners, four Negro students at Virginia Union Col

lege, were tried together and convicted2 in the Hustings

Uourt of the City of Richmond, sitting without a jury,

February 25, 1963, of violating Section 18.1-173 of the Code

of Virginia in that they remained “upon the premises of

National White Tower System, Incorporated . . . after

having been forbidden to do so.” 3

At approximately 10:30 to 11:00 p.m. on the 8th of Janu

ary, 1963, petitioners seated themselves at the counter of

a White Tower restaurant in Richmond, Virginia (Tr. 4).

They were approached by the restaurant supervisor, who

“told them that they would not be served and to please

leave. They refused” (Tr. 4). He called the Richmond

Police Department (Tr. 5), and in the presence of police

officers told petitioners to leave (Tr. 5), but he did not

2 Petitioners were tried and convicted in one proceeding in the

Hustings Court (Tr. 3). They received identical sentences and

filed joint Notice of Appeal and Assignments of Error (Tr. 33).

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, each

petitioner filed separate, though identical, Petitions for Writ of

Error and the Petitions were denied by the Supreme Court of

Appeals in four separate, though identical, orders, infra, pp. 17-20.

3 See the “original warrants” in the Hustings Court.

6

inform petitioners of the reason he was asking them to

leave (Tr. 8).

The restaurant was open for business and white cus

tomers were present and being served at the time, but only

Negroes were asked to leave (Tr. 7, 10, 28). The restaurant

was not crowded (Tr. 8) and petitioners were not disorderly

(Tr. 8) or “anything like that” (Tr. 8, 9). There was “no

disorderly conduct on the part of anyone” (Tr. 17).

The arresting officer, Frank Duling, testified he “received

information there was a set-in (sic) demonstration” (Tr.

13) and arrived at the White Tower to find “15 colored

males inside the White Tower” (Tr. 13). The restaurant

supervisor told Duling that the Negroes had been told to

leave and asked Duling to ask them to leave (Tr. 13).

“Then,” according to Duling, the supervisor “went to each

individual sitting there and made the following statement:

‘I am George Polhemus. I am manager of this restaurant.

You will not be served here, please leave’ ” (Tr. 14). Some

of the Negroes left the restaurant, but petitioners Smith,

Snead and Rucker made no move to leave and were arrested

(Tr. 14).

Petitioner Green was “just standing there” and Duling

“did not see Mr. Green sitting at the counter at any time.”

But Duling asked Green if he was going to leave and Green

replied that “no one had asked him to leave” (Tr. 14).

Green was then told to leave by the supervisor (Tr. 14, 15).

He requested to speak to Smith, Snead and Pucker (Tr. 15)

and was told “if he did not leave, as requested by the man

ager, that he, too, would be arrested.” When he did not

leave, he was placed under arrest (Tr. 15).

The trial judge repeatedly refused to permit petitioners’

counsel to inquire into the reasons petitioners were refused

service and asked to leave (Tr. 7, 9,10,11,12,18, 25). When

7

counsel asked the supervisor why he would not serve peti

tioners, objection was sustained on the ground that:

That is immaterial to the case. The question is whether

they were in violation of orders of the supervisor (Tr.

7).

Although “no one” was disorderly (Tr. 17) and the arrest

ing officer testified that he was called to the White Tower

because of a “set-in (sic) demonstration” (Tr. 13), the

manager was not permitted to state if there “was any reason

why you would not serve them other than they are

Negroes?” (Tr. 9). The city attorney took the position that

the reason they were asked to leave was immaterial for

the reason that “they were told to leave and there was no

reference to race . . . ” (Tr. 25) and the rulings of the

trial court were in accord with this position (Tr. 7, 9,10, 11,

12, 18, 25).

Petitioners were found guilty and fined $10 each and

costs (Tr. 33).

Petitioners filed timely petitions and supplemental peti

tions for writ of error in the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia, These petitions were denied October 17, 1963,

infra, pp. 17-20. Denial of writ of error by the Supreme

Court of Appeals has the effect of affirming the judgment

of the trial court, Ibid.

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

At the conclusion of the state’s evidence in the trial

court and again prior to judgment, petitioners moved to

strike the evidence against them on the ground that con

viction on the evidence adduced would place the authority

of the state behind private prejudice (Tr. 19-21, 30-32).

8

These motions were overruled (Tr. 21, 33). Petitioners’

counsel also sought unsuccessfully to develop evidence of

the reason petitioners were refused service (Tr. 7, 9, 10,

11, 12, 18, 25).

Petitions and supplementary petitions (filed with leave

of Court) for writ of error raised the question under the

Fourteenth Amendment

whether a concern licensed to do business with the

general public can legally, after inviting members of

the general public into the store, order them to leave

such establishment when such invitees are not disor

derly and do not violate any law; and if so . . . whether

the State can legally enforce such private discrimina

tion where such discrimination is based upon race and

color.

Petitioners also claimed violation of Fourteenth Amend

ment rights in that the trial court erred by “repeatedly

refusing to permit defendants to inquire into the reasons

why defendants were not served and were ordered out of

the public eating place.”

Petitioners also claimed violation of Fourteenth Amend

ment rights in that state statutes compelled racial discrim

ination on the part of the restaurant:4

Code of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, Sec.

18.1-356 and 18.1-357 supports the policy of racial

segregation enforced by the restaurant. Sec. 18.1-356

and 18.1-357 require segregation and removed the deci

sion of the restaurant manager from the sphere of

private choice. Defendants’ convictions were, there

fore, obtained in violation of the due process clause

4 See Supplemental Petitions for Writ of Error.

9

and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

(Emphasis: supplied.)

October 17, 1963, the Supreme Court of Appeals denied

petitions for writ of error on the ground that the judgment

of the trial court was “plainly right,” infra, pp. 17-20. The

Court stated the effect of denial “is to affirm the judgment

of the said Hustings Court,”. Ibid.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The State by Reason of Statutes Requiring Segrega

tion at “Any Place of . . . Public Assemblage” Was In

volved to a Significant Extent in the Refusal to Serve

Negro Petitioners.

At the time petitioners were refused service and ordered

to leave the restaurant, January 8, 1963, Virginia law pro

vided criminal penalties for failure to observe racial seg

regation at “any place of . . . public assemblage.” Code of

Virginia, 1960, §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357. These penalties ap

plied to the enterprise at which failure to observe seg

regated seating took place, §18.1-356 and to persons failing

to observe segregated seating arrangements, §18.1-357.

These statutes were declared unconstitutional by the Su

preme Court of Appeals of Virginia September 11, 1963,

Brown v. City of Richmond, ----- V a .----- , 132 S. E. 2d

495 ;5 see also Blackwell v. Harrison, 221 F. Supp. 651

(E. D. Va. 1963).

5 Petitioners’ convictions were affirmed October 17, 1963, infra,

pp. 17-20.

10

The application of §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357 to restau

rants is not a question to which the Supreme Court of

Appeals has addressed itself.6 The opinion of that Court

in Brown v. City of Richmond, supra, did not discuss the

question. One federal court, however, has found restaurant

segregation compelled by the statutes, Nash v. Air Terminal

Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D. Va. 1949); another federal

court, on concession of a party, has proceeded on the as

sumption that it was not, Williams v. Howard Johnson

Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959).7

It is settled that if petitioners had been asked to leave

the restaurant by reason of the command of these statutes,

their convictions for trespass could not stand under the

Fourteenth Amendment, Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373

U. S. 244:

When the State has commanded a particular result it

has saved to itself the power to determine that result

and thereby “to a significant extent” has “become in

volved” in and, in fact, has removed that decision from

the sphere of private choice.

6 This Court vacated judgments in light of Peterson v. Green

ville, supra, in Randolph v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 97; Henry v. Vir

ginia, 374 TJ. S. 98; Thompson v. Virginia, 374 U. S. 99; Wood v.

Virginia, 374 U. S. 100, prior to the judgment affirming peti

tioners’ conviction here, but the Supreme Court of Appeals has

not taken any action on the remand of these cases.

7 The Attorney General of Virginia (in response to an inquiry

from a municipality that still, it seems, desired to enforce the

segregation laws in accordance with their just construction) gave

it as his opinion that the statute did not require restaurant segre

gation, but he relied wholly on the rule of ejusdem generis, hardly

a satisfying guide for a restaurant manager. Opinion of the State

Attorney General to the Commonwealth Attorney of the City of

Roanoke, Aug. 24, 1960, 5 Race Relations Law Reporter 1282

(1960).

11

And this is true “even assuming . .. that the manager would

have acted as he did independently of the existence of the

Ordinance” for the “convictions had the effect, which the

state cannot deny, of enforcing the Ordinance . . . ” Peter

son, supra.

In Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, there was no

segregation provision but “evidence tended to indicate that

the store officials’ actions were coerced by the city” and,

therefore, the “city must be treated exactly as if it had an

ordinance prohibiting such conduct.” Lombard, supra.

- Applicable to “any place of-. . . public assemblage,” there

is no reason why these statutes should not be read to compel

restaurant segregation. This Court need not, however, re

solve the question, for it is clear that restaurant proprie

tors might reasonably believe segregation required by the

broad language of these statutes, and consequently conform

their conduct to them. Such a result would be “coercion,”

Lombard, supra, sufficient to invoke the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

Regardless of whether §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357 of the Code

of Virginia compel restaurant segregation, as in Peterson,

or coerce it, as in Lombard, petitioners’ convictions cannot

stand. At the very least the uncertainty of the. reach of

these broad provisions is sufficient to encourage segregation

and withdraw the decision to serve or not to serve Negroes

from the purely private sphere. Cf. Gantt v. Clemson Agri

cultural College of South Carolina, 320 F. 2d 611, 613 (4th

Cir. 1963). In this respect these provisions are like any

statutes which due to vagueness and ambiguity may throttle

protected conduct. See e.g., Winters v. New York, 333 U. S.

507; Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229.

Doubts as to the application of these statutes must be

resolved in favor of petitioners, for here, as in Lombard v.

12

Louisiana, supra, “the evidence of coercion was not fully

developed because the trial judge forbade petitioners to ask

questions directed to that very issue.” Petitioners’ counsel

was thwarted repeatedly in his efforts to ascertain the rea

sons for the failure to serve petitioners (Tr. 7, 9, 10, 11,

12, 18, 25). Denial of the opportunity to establish violation

of a constitutional right is itself denial of a constitutional

right. Carter v. Texas, 177 TJ. S. 442.

II.

Petitioners’ Convictions Enforce Racial Discrimination

in Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

This petition presents for decision issues identical to

those pending before this Court in Barr v. City of Columbia,

No. 9, October Term, 1963; Bouie v. City of Columbia,

No. 10, October Term, 1963; Bell v. Maryland, No. 12,

October Term, 1963; Robinson v. Florida, No. 60, October

Term, 1963; Griffin v. Maryland, No. 6, October Term, 1963.

Those cases and this raise the question of a state’s consti

tutional responsibility for acts of racial discrimination en

forced by criminal convictions. Where a petition for cer

tiorari presents questions identical with, or similar to,

issues already pending before this Court in another case

in which certiorari has been granted, the issues involved

in the petition are obviously appropriate for review by

certiorari. Compare Trustee of Monroe Ave. Church of

Christ v. Perkins, 334 U. S. 813, with Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U. S. 1.

Petitioners’ convictions enforce racial discrimination in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. This record shows

racial discrimination despite the refusal of the trial judge

to permit petitioners to develop evidence that race was

13

the reason they were ordered to leave the restaurant. The

arresting officer testified that he was called to the restau

rant because of a “set-in (sic) demonstration.” It is well-

known and commonly understood that a “sit-in” is a peace

ful attempt by Negroes to obtain service at restaurants

or other business enterprises which maintain a policy of

racial exclusion or segregation. Gamer v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157, 193 (Mr. Justice Harlan concurring). Upon ar

riving the arresting officer found “fifteen colored males”

and only they (not white patrons) were ordered to leave.

Despite the failure of the trial judge to permit evidence

which would develop the precise reasons for the exclusion

of petitioners, it is plain from this record that petitioners

were excluded for their race. Cf. Child Labor Tax Case,

259 U. S. 20, 37.

The state is constitutionally responsible for racial dis

crimination under three related theories urged by peti

tioners :

First, the use of state judicial machinery to convict peti

tioners of a crime is a use of state power in the Fourteenth

Amendment sense. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 is

applicable and cannot properly be distinguished.

Second, state action is involved because the acts of dis

crimination were casually related at least in part to a

segregation custom which law has substantially supported.

See e.g. Code of Virginia, §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357; NAACP

v. Button, 371 U. S. 415; Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61;

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1958).8 State

8 In Virginia whites and Negroes may not study together (Const,

of Va. §140; Code of Va., I960, §22-221), marry one another (Code

of Va., 1960, §20-54), go to prison together (Code of Va., 1960,

§53-42), join a fraternity together (Code of Va., 1960, §38.1-597),

go together to the hospital for feebleminded (Code of Virginia,

1960, §37-183), wait for an airplane together (Code of Va. 1960,

§56-196), get on a bus together (Code of Va., 1960, §56-326).

14

action is causally traceable into the discrimination prac

ticed here. Segregation is all one piece; when the state

holds up the edifice at a hundred points by law, it is surely

contributing to its standing up even at the points where

the law does not directly take hold. Moreover, the state

has not shown a contrary, and the burden of proving other

wise should rest on the state in the circumstance of this

case.

Finally, state power is involved to a significant degree

in that the state’s regime of laws fails to furnish protection

to petitioners by subordinating their claimed rights to

equality to a narrow and technical property claim. The

state’s role is not neutral; it has preferred the discrim

inator’s insubstantial property claim to the petitioners’

claim of equality. The Fourteenth Amendment overrides

this state power, for equal protection of the laws requires

the states to protect a claim of equality in such circum

stances.

The theories of state action urged above may be limited

in their incidents by an interpretation of the substantive

meaning of the equal protection clause which recognizes

other constitutional demands. Thus, the personal and pri

vate life of individuals need not be subjected to Fourteenth

Amendment norms. Petitioners do not urge that no state

action is needed under the Fourteenth Amendment, but

rather that because it is usually present, a substantive rule

applying the equal protection clause to the public life of

the community is needed. See Henkin, “Shelley v. Kraemer:

Notes for a Revised Opinion,” 110 U. Pa. L. Rev. 473 (1962).

15

CONCLUSION

W h e r e f o r e , f o r th e fo r e g o in g re a s o n s , p e t i t io n e r s p r a y

t h a t th e p e t i t io n f o r w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i be g r a n te d .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R oland D. E aley

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Petitioners

a p p e n d ix

17

APPENDIX

Denial of Writ of Error

V irginia :

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Thursday the 17th day of October, 1963.

The petition of Reginald M. Green for a writ of error

and supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings

Court of the. City of Richmond on the 25th day of- February,

1963, in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against the

said petitioner for a misdemeanor, having been maturely

considered and a transcript of the record of the judgment

aforesaid seen and inspected, the court being of opinion that

the said judgment is plainly right, doth reject said petition

and refuse said writ of error and supersedeas, the effect

of which is to affirm the judgment of the said hustings court.

1 A copy, Teste:

H. F. T urner

Clerk

18

Denial of Writ of Error

V irginia:

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Thursday the 17th day of October, 1963.

The petition of Harry Lee Snead for a writ of error and

supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings Court

of the City of Richmond on the 25th day of February, 1963,

in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against the said peti

tioner for a misdemeanor, having been maturely considered

and a transcript of the record of the judgment aforesaid

seen and inspected, the court being of opinion that the said

judgment is plainly right, doth reject said petition and

refuse said writ of error and supersedeas, the effect of

which is to affirm the judgment of the said hustings court.

A Copy, Teste:

H. F. T urner

Clerk

Denial of Writ of Error

V irg inia :

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Thursday the 17th. day of October, 1963.

The petition of Andre Pierre Smith for a writ of error

and supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings

Court of the City of Richmond on the 25th day of February,

1963, in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against the

said petitioner for a misdemeanor, having been maturely

considered and a transcript of the record of the judgment

aforesaid seen and inspected, the court being of opinion

that the said judgment is plainly right, doth reject said

petition and refuse said writ of error and supersedeas, the

effect of which is to affirm the judgment of the said hustings

court.

A copy, Teste:

H. F. T urner

Clerk

20

Denial of Writ of Error

V irginia :

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Thursday the 17th day of October, 1963.

The petition of Willie Frank Rucker for a writ of error

and supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings

Court of the City of Richmond on the 25th day of February,

1963, in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against the

said petitioner for a misdemeanor, having been maturely

considered and a transcript of the record of the judgment

aforesaid seen and inspected, the court being of opinion

that the said judgment is plainly right, doth reject said

petition and refuse said writ of error and supersedeas, the

effect of which is to affirm the judgment of the said hustings

court.

A copy, Teste:

H. F. T urner

Clerk