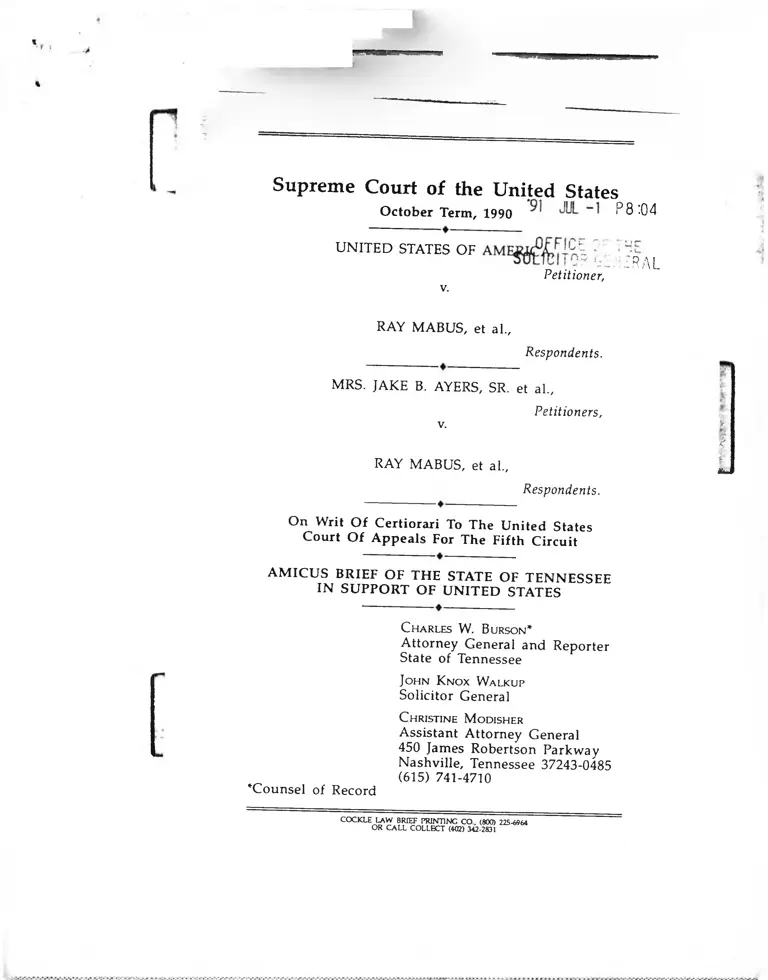

United States v. Mabus Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Mabus Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1991. 3c65218e-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/181a0c51-7519-45ac-ac9f-b00979dc5fd5/united-states-v-mabus-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

•-••>'■ V» '

In The r e c f i v e d

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990 P8;04

UNITED STATES OF ^

Petitioner,

■RAL

V.

RAY MABUS, et a l .

Respondents.

MRS. JAKE B. AYERS, SR. et al..

Petitioners,

V.

RAY MABUS, et al..

Respondents.

On Writ O f Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

AM ICUS BRIEF OF THE STATE OF TENNESSEE

IN SUPPORT OF UNITED STATES

C harles W. Burson*

Attorney General and Reporter

State of Tennessee

John Knox Walkup

Solicitor General

^Counsel of Record

C hristine Modisher

Assistant Attorney General

450 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0485

(615) 741-4710

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225.6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

V-

<

i'

iEbj

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

What is the scope of the duty under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution of a state

which formerly operated a de jure segregated system of

higher education?

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICUS STA TE........................................ 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............................................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.............................................. 2

ARGUMENT.............................................................................. 3

I. THE SCOPE OF THE DUTY UNDER THE FOUR

TEENTH AM ENDM ENT TO THE UN ITED

STATES CONSTITUTION OF A STATE WHICH

OPERATED A DE JURE SEGREGATED SYSTEM

OF HIGHER EDUCATION INCLUDES ELIM

INATING THE PRESENT EFFECTS OF PAST

SEGREGATION................................................................. 3

II. THE SCOPE OF A STATE'S REMEDIAL DUTY IS

DETERMINED BY THE SCOPE OF THE STATE'S

CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION............................. 7

CONCLUSION......................................................................... 13

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases C ited

Alabama State Teacher Association v. Alabama Public

School and College Authority, 289 F.Supp. 784

(M.D. Ala. 1968), aff'd per curiam, 393 U.S. 400

(1969)............................................................. ...............................8

Ayers v. Allain, 914 F.2d 676 (5th Cir. 1990).....................6

Bazemore v. Friday, 751 F.2cl 662 (4th Cir. 1984).............7

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1 9 8 6 )................... 3, 6, 7

Board of Education o f Oklahoma City Public Schools v.

Dowell, 111 S.Ct. 630 (1991)................................... 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 5, 6, 10

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955 )___4, 5

Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986).. 2, 6, 9, 11

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644 (M.D. Tenn. 1977)___10

Geier v. University of Tennessee, 597 F.2d 1056 (6th

Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) ...........................................................2, 8, 9, 10, 11

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) .. .3, 4

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, CA, 480 U.S. 616 (1987)...................................... 12

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 5 ).... 3, 4, 6

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976)............................................ ...................g, 12

Plessy V. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).........................5, 10

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F.Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn.

1968)........................................................................................ 9, 10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971 )...............................................................8, 12

Sweatt V. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)................................. 5

U.S. V. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987)............................... 4, 5

United Steelworkers, etc. v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979).......................................................................................... 12

No. 90-1205 and No. 90-6588

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Petitioner,

V.

RAY MABUS, et a I.,

Respondents.

MRS. JAKE B. AYERS, SR. et al..

Petitioners,

RAY MABUS, et al.

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

---------------- 4-----------------

AMICUS BRIEF OF THE STATE OF TENNESSEE

IN SUPPORT OF UNITED STATES

INTEREST OF AMICUS STATE

The State of Tennessee, its Governor, the Tennessee

Board of Regents, the University of Tennessee, and the

Tennessee Higher Education Commission, as defendants

in the higher education desegregation case now styled

Geier v. McWherter, have definite and substantial interest

in the outcome of this case. One basis of the petitions for

certiorari by the United States and by petitioners Ayers,

et al., is that the Fifth Circuit's ruling in this case is in

conflict with the law of the Sixth Circuit as set forth in

Geier v. University of Tennessee, 597 F.2d 1056 (6th Cir.

1979) and Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986).

The decision in this case will have direct effect on the

Tennessee desegregation litigation in Geier.

Tennessee can provide assistance to this Court in this

case because of Tennessee's experience in Geier over the

last twenty-three years.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The amicus state adopts the statement of the case as

presented by the United States in its petition for cer

tiorari.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The duty of a state which formerly operated a segre

gated system of higher education in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is to

cease the discrimination and to eliminate the present

effects of that past discrimination. The scope of a state's

remedial duty in this context is determined by the scope

of the state's constitutional violation.

No set rules are applicable to every situation. How

ever, a system of higher education has fulfilled its consti

tutional duty when:

- all facilities are equal,

- program duplication has been eliminated at

formerly white and black institutions in the

same geographical area,

- admission requirements do not perpetuate

substandard academic quality at formerly

black institutions,

- governing boards are integrated,

- affirmative action in hiring and promotion

decisions have produced results and promise

to continue to do so.

ARGUMENT

I. THE SCOPE OF THE DUTY UNDER THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES

CONSTITUTION OF A STATE WHICH OPERATED

A DE JURE SEGREGATED SYSTEM OF HIGHER

EDUCATION INCLUDES ELIMINATING THE PRE

SENT EFFECTS OF PAST SEGREGATION.

It is the position of the amicus state that the duty of a

state which formerly operated a de jure segregated sys

tem of higher education is not solely controlled by either

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) or

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986). Rather, the duty of

a state which operated a segregated system of higher

education in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment is

controlled by Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965).

The duty of a court to fashion remedies in race dis

crim ination cases brought u nder the Fou rteenth

Amendment was stated in Louisiana v. United Stales, 380

U.S. at 154. In this voting rights case, this Court stated

that "the [district] court has not merely the power but the

duty to render a decree which will so far as possible

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as

bar like discrimination in the future." This aspect of the

decision has been applied in a variety of other Fourteenth

Amendment race discrimination cases.

In the context of desegregation of public elementary

and secondary education, this Court relied upon Louisi

ana in Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. at 438. In

Green, the Court noted Louisiana and held that Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) {Brown II), com

m an d ed th a t " s ta t e - c o m p e l le d d u a l s y s te m s

were . . . clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take

whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary

system in which racial discrimination would be elimi

nated root and branch." Green, 391 U.S. at 438. Green held

that a "freedom of choice" plan for students was not an

end in itself but rather a means to a constitutionally

required end of segregation and its effects. Where a "free

dom of choice" plan did not produce the desired effects,

something more was required. Id., 391 U.S. at 439.

This Court also relied upon Louisiana in U.S. v. Para

dise, 480 U.S. 149, 183 (1987) for the proposition that a

district court has the duty to render a decree which will

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past. Paradise

was a race discrimination in employment case brought

under the Fourteenth Amendment. In Paradise, this Court

upheld a court-ordered race-conscious affirmative action

plan designed to redress past race discrimination in

hiring and promotion by the Alabama Department of

Public Safety. In fact, this Court stated: "The government

unquestionably has a compelling interest in remedying

past and present discrimination by a state actor." Id at

167.

In the landmark case of Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954) {Brown I) this Court concluded

that "in the field of public education the doctrine of

separate but equal has no place. Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal." This Court concluded

that segregated education deprived black students of

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment. This Court in Brown I referred gener

ally to public education" and no one can seriously

dispute that this doctrine applies with equal force to

public post-secondary education.’

In Brown II, 349 U.S. at 301, this Court noted that

school systems must "effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system." In this context, the

Court mentioned the physical condition of school plants,

the school transportation system, personnel, and a system

of determining admission to public schools on a non-

racial basis. Id.

In Brown I this Court discussed several prior cases deal

ing with segregation in higher education. Specifically it was

noted that in Sweait v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), the question

Whether Plessy v. Fcrpison, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) should be held

inapp icablc to public education was expressly reserved.

It would be illogical and contrary to all precedent to

say that this same duty does not apply to race discrimina

tion in public higher education. A state which in the past

operated a de jure system of higher education has a duty

under the Fourteenth Amendment to eliminate the pre

sent effects of that past discrimination.

In Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986) the

Sixth Circuit upheld a pre-professional program for black

undergraduate stu d ents. The Court d istingu ished

Bazemore based on the greater value of advanced educa

tion as compared with high school clubs. This reasoning

of the Sixth Circuit was criticized by the Fifth Circuit in

Ayers v. Allain, 914 F.2d 676 (5th Cir. 1990).

It is true that states have great interest in the educa

tion of their citizens. See Brown I. However, the source of

the duty to remedy present effects of past de jure segrega

tion does not rest on the relative merits of elementary and

secondary education compared with post-secondary edu

cation. The source of the duty is the Fourteenth Amend

ment as interpreted in Louisiana and the compelling

interest of the state in remedying past and present dis

crimination by a state actor.

This Court's decision in Bazemore is not inconsistent

with this line of cases. In Bazemore, this Court held in a

Title VII claim that the state was required to remedy

present racially discriminatory salaries resulting from

past race discrimination. Bazemore, 478 U.S. at 397. With

regard to 4-H and Extension Homemaker Clubs for high

school students, the Fourth Circuit had found that there

was no evidence that anyone was denied membership or

services or provided inferior services because of their

race. Bazemore v. Friday, 751 F.2d 662 (4th Cir. 1984). This

ourt noted that there was no current violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment since prior discriminatory prac-

doiTcv d a neutral admissions

policy adopted. Bazemore, 478 U.S. at 408. In essence all

discrimination and its effects caused by the state had been

remedied. There was no proof of racially-biased services

or admission requirements.

Bazemore is factually distinguishable from formerly

e jure segregated state systems of higher education. In

higher education, the "disease" of de jure segregation can

be much more widespread and include inferior facilities

segregated faculties, program duplication, and differing

student admission requirements. None of these factors

were present in Bazemore. For these reasons, it is the

suggestion of the amicus state that it is the duty of a state

which operated a de jure system of higher education in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to cease the dis

crimination and to remedy the present effects of the past

discriminatory actions, ^

” ■ ™ ,! SCOPE OF A STATE'S REMEDIAL DUTY rs

d e t e r m in e d b y t h e s c o p e o f t h e I

CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION ®

r. a amicus state that the duty to

s i r f t ;d discrimination is

alisfied when the state has placed in compliance with

u n d e rT h ? ? ','’ - - P - ' s of the system

Phan e ■ ? * determination of com-

Phance „,i| depend on the facts of each case, general

ines can and should be drawn by this Court.

The state or other body which originally imposed de

jure segregation has the affirmative obligation to remedy

the effects of that discrimination. Judicial authority enters

only when the state or local authority defaults. It is well-

established with equity cases that the nature of the viola-

Uon determines the scope of the judicial remedy. Swann v

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U S 1 16

(1971). This principle is tied in part "to the necessity of

establishing that school authorities have in some manner

caused unconstitutional segregation, for 'absent a consti

tutional violation there would be no basis for judicially

ordering [a remedy].' " Pasadena City Board o f Education v.

er, 427 U.S. 424, 434 (1976) citing Swann, 402 U.S. at

8. Thus the scope of the remedy must be determined by

looking at the nature of the original constitutional viola

tion by the state.

Various courts have noted the differences between

e ementary and secondary education on the one hand and

higher education on the other. See Geier v. University of

I Z T t . T ’ 979), cert. d e L d ,

At h 886 (1979); Alabama State Teachers Association v.

v Z r Z Z Authority, 289 F.Supp.

• D. Ala. 1968), aff'd per curiam, 393 U.S. 400 (1969).

a^ssfi^ n t/T ^""’ .^°"^P^Jsory and pupils are

assigned to particular schools. The other is

pure y elective, requires the payment of tuition

and fees, and permits students to choose a par-

dcular school for a variety of reasons. Most ele

mentary and secondary schools are roughly

equal ,n curriculum and facilities whereas indi-

thf (5° universities vary greatly in

their offerings and emphasis. ^

Ceier v. University o f Tennessee, 597 F 2d at 106-1 r

higher ecfucation

unif„:.r, are'^no,

These differences, however, do not result in . i

R a T r° T s f d ? d iscrim ln ato "

responsible for public higher educaflon do g a,lv have

offered by e lh 'T n s m u 'ro n .'^ u S rn f ̂ r a ^ e

and in student recruitment. ^ ^

example of the effectiveness

hio6 Z ‘̂ ^segregation remedies in the context of

higher educa,ion can be found in Tennessee. , 7 ^ 1

hee'n elim^il^e^ lo T ta rg e ^ t n , '

slales'''o aod secondary educalion in many

aippi and d i e l T ' * " ’' Tennessee, Missis-

In Tennessee th er"l racially segregated by law.

nfod by e s e fo learning oper-

Sfate u 7 i?er;i,y 7

"00 Agricultural and Industrial St

“■ EHmgfen, 288 F.Supp 9 ^ 940 7Fp. y j / , y40 (M.D. Tenn. 1968). The

10

state statute creating T.S.U. stated that its purpose was

" . . . to train negro students in agriculture, home eco

nomics, trades and industry, and to prepare teachers for

the elementary and high schools for negroes in the state."

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644, 645 n. 2 (M.D. Tenn.

1977) citing Tenn. Code Ann. §49-3206. Compulsory racial

segregation in all Tennessee institutions of higher learn

ing was first mandated by Article II, §12 of the Tennessee

Constitution of 1870. In 1901 Tennessee became the first

state to enact criminal statutes requiring racial segrega

tion in all public and private colleges. Geier v. University

of Tennessee, 597 F.2d at 1058 n. 1. As the district court

noted in 1968;

Prior to the Supreme Court decision in Brown v.

Board o f Education in 1954 the public educational

system in Tennessee operated under one-half of

the decision of the Supreme court in Plessy v.

Ferguson of 1896 . . . The races were certainly

kept separate in the schools; but I would assume

that no one would argue in good faith that the

schools were equal.

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F.Supp. at 939.

Desegregation of Tennessee higher education has

been under the Court's jurisdiction since 1968 - twenty-

three years. This litigation resulted in an order to merge

Tennessee State University, the formerly black school in

Nashville, with University of Tennessee Nashville - a

predominantly white school about five miles from T.S.U.

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644 (M.D. Tenn. 1977), a ff’d

Geier v. University o f Tennessee. This was permissible,

according to the Sixth Circuit, because the defendants

had failed to dismantle the state-wide dual system, the

11

"heart" of which was an all black T.S.U. Geier v. University

of Tennessee, 597 F.2d at 1067.

In 1984 all the parties to the litigation with the excep

tion of the United States entered a "Stipulation of Settle

ment" which was approved by the Court. The Stipulation

is reported in Geier v. Alexander, 593 F.Supp. 1263, 1267

(M.D. Tenn. 1984), aff'd 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986). This

Stipulation addresses student recruitment and retention,

open admissions to two-year institutions, changes in

admission and retention requirements for four-year

schools and racially identifiable institutional image. In

the area of employment, the Stipulation requires that

other race employment goals be set for each institution

and that a variety of programs be implemented to train,

recruit, and employ other race faculty and administra

tors. The Stipulation also addresses Tennessee State Uni

versity and the two other four-year institutions in Middle

Tennessee. It provides for improvement in the facilities at

T.S.U., elimination of program duplication, and enhance

ment of program offerings at T.S.U.

Significant effort has been made by the State of Ten

nessee under this stipulation and the results have been

dramatic. By fall, 1990 nearly $39,000,000 had been appro

priated to fund an ambitious master plan to improve the

acihties at T.S.U. An additional $9,000,000 was recom

mended for fiscal year 1991 to fund other desegregation

activities under the Stipulation. (1991 Desegregation

rogress Report, Table 17, Reproduced as Appendix A).

formerly white colleges and universities

P oye black faculty and administrators roughly in

oportion to their availability. More than half of the

12

formerly white schools had met their goals in black stu

dent enrollment. (1990 Desegregation Progress Report,

Table 1, Reproduced as Appendix B). The entire 1990

Desegregation Progress Report has been filed with this

Court for its consideration.

In hearing this case, this Court should consider not

only defining the duty of public higher education to

desegregate but also when that duty has been satisfied.

Under this Court's recent decision in Board of Education of

Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 111 S.Ct. 630, 638

(1991), a court's jurisdiction over a desegregation case

can be ended when there has been good faith compliance

with the desegregation decree and when the vestiges of

past discrimination have been eliminated to the extent

practicable. Judicial tutelage for the indefinite future is

not required.

Although no set rules applicable to every situation

can be made, the amicus state urges that the parameters

of the legal duty to desegregate be defined.

1. The state need only remedy the present effects of

past state imposed segregation.

2. There is no constitutional right to a particular

degree of racial balancing or mixing. Pasadena, 427 U.S. at

434; Swann, 402 U.S. at 24.

3. Affirmative action and race-conscious remedies

cannot be used to maintain any particular racial balance.

United Steelworkers, etc. v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 208 (1979);

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County, CA,

480 U.S. 616, 630 (1987).

13

4. A system of higher education may be declared

unitary and a desegregation case dismissed when:

- all facilities are equal,

- program duplication has been eliminated at

formerly white and black institutions in the

same geographical area,

- admission requirements do not perpetuate

substandard academic quality at formerly

black institutions,

- governing boards are integrated,

- affirmative action in hiring and promotion

decisions have produced results and promise

to continue to do so.

The position of the amicus state is that a state's duty

to desegregate higher education should be determined by

the scope of the state's violation. The parameters of that

duty under the Fourteenth Amendment and when that

duty has been met would help guide state higher educa

tion systems and the court.

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing authorities and analysis, the

amicus state urges this Court to reverse the decision of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

and hold that a state has a duty under the Fourteenth

̂ mendment to remedy the present effects of past seg-

■ •egation in higher education. The amicus state also urges

14

this Court to give general guidelines for states and courts

as to how this duty might be satisfied.

Respectfully submitted,

C harles W. B urson

Attorney General and Reporter

J. Knox Walkup

Solicitor General

C hristine Modisher

Assistant Attorney General

450 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, TN 37243-0485

615-741-4710

APPENDIX A

lA

1990

DESEGREGATION PROGRESS REPORT

Prepared by

THE TENNESSEE HIGHER EDUCATION

COM M ISSION

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

THE TENNESSEE BOARD OF REGENTS

for the

DESEGREGATION MONITORING COMMITTEE

MAY 3, 1991

2A

[43A]

TABLE 17

COMPARISON OF COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DESEGREGATION

ACTIVITIES BY INSTITUTION, FY 88 THROUGH FY 92

APSU

ETSU

MSU

MTSU

TSU

TTU

SUBTOTAL TBR

UNIVERSITIES

CSTCC

CLSCC

COSCC

DSCC

JSCC

MSCC

RSCC

SSCC

VSCC

WSCC

SUBTOTAL

COMM. COLLEGES

NSTCC

NSTI

PSTCC

STIM

SUBTOTAL TECH INST

& COMM. COLLEGES

TN BOARD OF

r e g e n t s ADMN.

SUBTOTAL

TN BOARD

OF REGENTS

R̂ BVV:gm

FY 88

$110,000

196.000

572.000

353.000

605.000

160.000

FY 89

$113,000

249.000

666.000

368.000

617.000

149.000

FY 90

$116,000

453.000

687.000

383.000

1,207,000

153.000

FY 91

$119,000

457.000

709.000

399.000

1,261,000

158.000

FY 92

$125,000

510.000

848.000

420.000

1,469,000

164.000

$1,996,000

$71,000

15.000

39.000

25.000

52.000

17.000

15.000

42.000

21.000

17,000

$2,162,000

$74,000

15.000

36.000

24.000

54.000

17.000

15.000

43.000

21.000

17,000

$2,999,000

$77,000

15.000

37.000

27.000

56.000

18.000

15.000

44.000

21.000

17,000

$3,103,000

$80,000

26,000

38.000

26.000

58.000

30.000

15.000

46.000

21.000

28,000

$3,536,000

$84,000

28,000

39.000

27.000

60.000

32.000

25.000

47.000

25.000

30.000

$314,000 $316,000 $325,000 $368,000 $397,000

$25,000

25.000

25.000

25.000

$100,000

$497,000

$230,000 $230,000 $230,000 $230,000 $230,000

$2,540,000 $2,708,000 $3,554,000 $3,701,000 $4,263,000

3A

[44A]

TABLE 17

COMPARISON OF COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DESECRATION

ACTIVITIES BY INSTITUTION, FY 88 THROUGH FY 92

FY88 FY 89 FY 90 FY 91 FY 92

UTC $237,000 $244,000 $252,000 $263,000 $274,000

UTK 676,000 685,000 713,000 743,000 807,000

UTM 184,000 190,000 195,000 202,000 209,000

SUBTOTAL $1,097,000 $1,119,000 $1,160,000 $1,208,000 $1,290,000

UTMphs $438,000 $472,000 $834,000 $837,000 $793,000

UTSl 79,000 68,000 69,000 69,000 70,000

UT Agriculture 44,000 44,000 44,000 37,000 37,000

UT Vet. Med. 45,000 46,000 68,000 70,000 91,000

UT IPS, CTAS, MTAS 0 0 0 9,000 9,000

SUBTOTAL $606,000 $630,000 $1,015,000 $1,022,000 $1,000,000

UT ADMIN $ $ $ $ $SUBTOTAL UT $1,703,000 $1,749,000 $2,175,000 $2,230,000 $2,290,000

med/ d e n / p h a r m COND

grant PROGRAM $746,000 $871,000 $ $ $

TOTAL $4,989,000 $5,328,000 $5,729,000 $5,931,000 $6,553,000

addition to the amounts shown above; (1) For FY87, $5,225,000 was recommended for capital projects at TSU. For FY88, $746,000 was

recommended for Campus Outside Improvements at TSU, $137,000 was recommended for Outside Lighting Installation at TSU. For FY89,

• million was recommended for TSU capital outlay projects. For FY 90, $22.0 million was recommended for TSU capital outlay projects,

an or FY 91, an additional $24.5 million is recommended. For FY 92, the Commission has recommended funding for TSU capital outlay

projects totaling $24.2 million. (2) For FY86, an increase of $2 million was recommended for TSAC funding and that amount addresses

orne of the concerns raised in Geier provision IIG.

The program was expanded to include pharmacy in FY 88. In FY 90, at ETSU and UTMphs, the Black Conditional Grant Program

ecame a Black Tennessean Scholarship Program. The original program will remain in effect at Meharry, $310,000, and Vanderbilt,

$20,000, for FY 91 and 92. 6 f 6 y,

The Regional Minority Teacher Education Program is recommended for third-year funding elsewhere for $250,000.

APPENDIX B

IB

[lA]

TABLE I

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

FALL 1988

in stitu tio n s & EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

t b r u n iv e r sit ie s

APSU Undergraduates 4,775 770 3,774 231 16.13%

Graduates 393 31 351 11 7.89%

Total 5,168 801 4,125 242 15.50%

Administrators 28 3 25 0 10.71%

Faculty 200 13 178 9 6.50%

Professionals 78 6 72 0 7.69%

ETSU Undergraduates 9,218 228 8,554 436 2.47%

Graduates 1,536 44 1,363 129 2.86%

Total 10,754 272 9,917 565 2.53%

Administrators 59 4 55 0 6.78%

Faculty 429 12 404 13 2.80%

Professionals 105 4 101 0 3.81%

ETSU MED. Medicine 229 24 188 17 10.48%

Administrators 10 1 8 1 10.00%

Faculty 135 2 121 12 1.48%

MSU

Professionals 65 1 63 1 1.54%

Undergraduates 16,179 3,004 12,841 334 18.57%

Graduates 3,682 423 3,045 214 11.49%

Law 409 31 372 6 7.58%

Total 20,270 3,458 16,258 554 17.06%

Administrators 125 13 111 1 10.40%

Faculty 752 42 667 43 5.59%

mtsu

Professionals 317 38 272 7 11.99%

Undergraduates 11,850 1,042 10,568 240 8.79%

Graduates 1,315 69 1,202 44 5.25%

Total 13,165 1,111 11,770 284 8.44%

Administrators 52 3 48 1 5.77%

Faculty 489 34 437 18 6.95%

Professionals 79 8 71 0 10.13%

2B

FALL 1989

ŝtitutions

]br universities

APSU

ETSU

ETSU MED.

MSU

MTSU

)ENT LEVELS

EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

Undergraduates 5,891 1,066 4,462 363 18.10%

Graduates 401 29 361 11 7.21 %

Total 6,292 1,095 4,823 374 17.40%

Administrators 29 4 25 0 13.79%

Faculty 210 17 185 8 8.10%

Professionals 86 7 79 0 8.14%

Undergraduates 9,643 276 8,916 451 2.86%

Graduates 1,542 32 1,374 136 2.08%

Total 11,185 308 10,290 587 2.75%

Administrators 63 5 58 0 7.94%

Faculty 436 14 410 12 3.21 %

Professionals n o 9 101 0 8.18%

Medicine 226 24 186 16 10.62%

Administrators 10 2 8 0 20.00%

Faculty 125 2 113 10 1.60%

Professionals 58 1 57 0 1.72%

Undergraduates 16,312 3,064 12,932 316 18.78%

Graduates 3,862 397 3,204 261 10.28%

Law 439 30 405 4 6.83%

Total 20,613 3,491 16,541 581 16.94%

Administrators 125 18 106 1 14.40%

Faculty 770 43 673 54 5.58%

Professionals 351 47 295 9 13.39%

Undergraduates 12,744 1,170 11,301 273 9.18%

Graduates 1,392 81 1,257 54 5.82%

Total 14,136 1,251 12,558 327 8.85%

Administrators 49 5 43 1 10.20%

Faculty 515 34 459 22 6.60%

Professionals 107 10 97 0 9.35%

Is^STlTUTlONS

STUDENT

LEVELS

&c

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL.

3B

FALL 1990

BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

OBJECT.

1990-91

%OTHER

RACE

LONG-RNGE

OBJECT.

%OTHER

RACE

(SEE ****)

IliK UNIVERSITIES

APSU

ETSU

ETSU MED.

MSU

MTSU

Undergraduates 5,971 1,077 4,616 278 18.04% 17.00 17.00

Graduates 376 26 345 5 6.91% 6.03 8.42

Total 6,347 1,103 4,961 283 17.38%

Administrators 27 3 24 0 11.11% 9.70

Faculty 222 17 195 10 7.66% 5.30

Professionals 85 12 73 0 14.12% 11.60

Undergraduates 9,761 307 8,993 461 3.15% 3.35 4.00

Graduates 1,597 37 1,409 151 2.32% 3.10 3.10

Total 11,358 344 10,402 612 3.03%

Administrators 58 3 55 0 5.17% 4.80

Faculty 441 13 416 12 2.95% 3.00

Professionals 119 10 109 0 8.40% 6.30

Medicine 236 29 194 13 12.29% 8.10 8.10

Administrators 8 2 6 0 25.00% 15.00

Faculty 90 3 80 7 3.,33% 2.90

Professionals 60 1 58 1 1.67% 6.30

Undergraduates 16,209 3,263 12,627 319 20.13% 30.15 40.40

Graduates 4,049 475 3,297 277 11.73% 20.60 26.56

Law 430 28 400 2 6.51% 9.00 9.60

Total 20,688 3,766 16,324 598 18.20%

Administrators 118 16 100 2 13.56% 15.90

Faculty 775 45 678 52 5.81% 5.00

Professionals 360 47 304 9 13.06% 12.70

Undergraduates 13,428 1,250 11,866 312 9.31% 9.61 11.50

Graduates 1,437 70 1,299 68 4.87% 7.50 9.00

Total 14,865 1,320 13,165 380 8.88%

Administrators 51 8 42 1 15.69% 11.10

Faculty 556 40 488 28 7.19% 6.90

Professionals 119 14 105 0 11.76% 7.10

4B

[2A]

TABLE I

PAI L 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

FALL 1988

ssTiTL'TlONS

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

ISL'— Undergraduates 6,440 4,354 1,851 235 67.61%

Graduates 913 262 607 44 28.70%

Total 7,353 4,616 2,458 279 62.78%

Administrators 34 25 8 1 73.53%

Faculty 328 158 136 34 48.17%

Professionals 123 98 24 1 79.67%

n u Undergraduates 7,001 223 6,629 149 3.19%

Graduates 900 34 761 105 3.78%

Total 7,901 257 7,390 254 3.25%

Administrators 70 4 63 3 5.71%

Faculty 330 15 282 33 4.55%

Professionals 124 13 108 3 10.48%

K)TAL tbr Undergraduates 55,463 9,621 44,217 1,625 17.35%

LNIV. Graduates 8,739 863 7,329 547 9.88%

WITH TSU) Law 409 31 372 6 7.58%

Medicine 229 24 188 17 10.48%

Total 64,840 10,539 52,106 2,195 16.25%

Administrators 378 53 318 7 14.02%

Faculty 2,663 276 2,225 162 10.36%

^OTAL tbr

L'NIV.

TSU)

Professionals 891 168 711 12 18.86%

Undergraduates 49,023 5,267 42,366 1,390 10.74%

Graduates 7,826 601 6,722 503 7.68%

Law 409 31 372 6 7.58%

Medicine 229 24 188 17 10.48%

Total 57,487 5,923 49,648 1,916 10.30%

Administrators 344 28 310 6 8.14%

Faculty 2,335 118 2,089 128 5.05%

Professionals 768 70 687 11 9.11%

5B

FALL 1989

STUDENT LEVELS %

i,vjstitutions & EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER BLACK

TSU*** Undergraduates 6,442 4,427 1,802 213 68.72%

Graduates 920 258 606 56 28.04%

Total 7,362 4,685 2,408 269 63.64%

Administrators 36 23 13 0 63.89%

Faculty 333 168 139 26 50.45%

Professionals 119 94 24 1 78.99%

ttu Undergraduates 6,859 216 6,479 164 3.15%

Graduates 1,204 37 1,065 102 3.07%

Total 8,063 253 7,544 266 3.14%

Administrators 73 5 66 2 6.85%

Faculty 344 16 305 23 4.65%

Professionals 119 13 104 2 10.92%

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 57,891 10,219 45,892 1,780 17.65%

UNIV. Graduates 9,321 834 7,867 620 8.95%

(WITH TSU) Law 439 30 405 4 6.83%

Medicine 226 24 186 16 10.62%

Total 67,877 11,107 54,350 2,420 16.36%

Administrators 385 62 319 4 16.10%

Faculty 2,733 294 2,284 155 10.76%

Professionals 950 181 757 12 19.05%

total TBR Undergraduates 51,449 5,792 44,090 1,567 11.26%

UNIV. Graduates 8,401 576 7,261 564 6.86%

(W/0 TSU) Law 439 30 405 4 6.83%

Medicine 226 24 186 16 10.62%

Total 60,515 6,422 51,942 2,151 10.61%

Administrators 349 39 306 4 11.17%

Faculty 2,400 126 2,145 129 5.25%

Professionals 831 87 733 11 10.47%

6B

institution s

STUDENT

LEVELS

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL.

FALL 1990

BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

OBJECT

1990-91

%OTHE

RACE

TSU*** Undergraduates 6,347 4,277 1,880 190 67.39% 45.00

Graduates 1,046 311 669 66 29.73% 71.44

Total 7,393 4,588 2,549 256 62.06%

Administrators 35 22 13 0 62.86% 50.80

Faculty 337 167 146 24 49.55% 51.00

Professionals 111 90 21 0 81.08% 39.00

TTU Undergraduates 7,150 246 6,734 170 3.44% 6.00

Graduates 984 32 841 111 3.25% 2.55

Total 8,134 278 7,575 281 3.42%

Administrators 66 6 58 2 9.09% 7.80

Faculty 342 16 303 23 4.68% 3.70

Professionals 123 13 107 3 10.57% 13.20

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 58,866 10,420 46,716 1,730 17.70%

UNIV. Graduates 9,489 951 7,860 678 10.02%

(WITH TSU) Law 430 28 400 2 6.51%

Medicine 236 29 194 13 12.29%

Total 69,021 11,428 55,170 2,423 16.56%

Administrators 363 60 298 5 16.53%

Faculty 2,763 301 2,306 156 10.89%

Professionals 977 187 777 13 19.14%

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 52,519 6,143 44,836 1,540 11.70%

UNIV. Graduates 8,443 640 7,191 612 7.58%

(W /0 TSU) Law 430 28 400 2 6.51%

Medicine 236 29 194 13 12.29%

Total 61,628 6,840 52,621 2,167 11.10%

Administrators 328 38 285 5 11.59%

Faculty 2,426 134 2,160 132 5.52%

Professionals 866 97 756 13 11.20%

LONG-RNGE

OBJECT.

%OTHER

RACE

(SEE ****)

61.30*

76.79

6.80*

3.00

7B

[3A]

TABLE I

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

FALL 1988

STUDENT LEVELS %

INSTITUTIONS & EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER BLACK

t b r c o m m u n it y c o l l e g e s

CSTCC Undergraduates 6,391 699 5,606 86 10.94%

Administrators 8 1 7 0 12.50%

Faculty 151 21 129 1 13.91%

Professionals 50 5 45 0 10.00%

CLSCC Undergraduates 2,977 150 2,780 47 5.04%

Administrators 15 2 13 0 13.33%

Faculty 67 4 61 2 5.97%

Professionals 18 4 13 1 22.22%

COSCC Undergraduates 2,667 218 2,421 28 8.17%

Administrators 11 2 9 0 18.18%

Faculty 66 7 58 1 10.61%

Professionals 21 1 18 2 4.76%

DSCC Undergraduates 1,742 209 1,519 14 12.00%

Administrators 9 1 8 0 11.11%

Faculty 43 7 36 0 16.28%

Professionals 16 1 15 0 6.25%

jSCC Undergraduates 2,774 355 2,410 9 12.80%

Administrators 11 1 10 0 9.09%

Faculty 74 7 67 0 9.46%

Professionals 10 2 8 0 20.00%

M s e c Undergraduates 2,392 129 2,241 22 5.39%

Administrators 19 2 17 0 10.53%

Faculty 50 3 47 0 6.00%

Professionals 5 2 3 0 40.00%

RSCC Undergraduates 3,853 108 3,706 39 2.80%

Administrators 6 1 5 0 16.67%

Faculty 88 2 86 0 2.27%

Professionals 34 5 29 0 14.71%

»d

FALL 1989

in stitu tio n s

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

tbr c o m m u n ity c o l l e g e s

CSTCC Undergraduates 7,412 829 6,470 113 11.18%

Administrators 7 1 6 0 14.29%

Faculty 136 22 113 1 16.18%

Professionals 55 6 49 0 10.91%

CLSCC Undergraduates 3,098 169 2,894 35 5.46%

Administrators 23 2 21 0 8.70%

Faculty 65 5 57 3 7.69%

Professionals 21 4 16 1 19.05%

c o s c c Undergraduates 3,053 219 2,794 40 7.17%

Administrators 12 3 9 0 25.00%

Faculty 71 9 60 2 12.68%

Professionals 24 2 21 1 8.33%

DSCC Undergraduates 1,851 220 1,607 24 11.89%

Administrators 11 2 9 0 18.18%

Faculty 44 6 38 0 13.64%

Professionals 16 3 13 0 18.75%

JSCC Undergraduates 3,010 400 2,592 18 13.29%

Administrators 12 3 9 0 25.00%

Faculty 74 7 67 0 9.46%

Professionals 10 1 9 0 10.00%

M sec Undergraduates 2,544 147 2,363 34 5.78%

Administrators 19 2 17 0 10.53%

Faculty 54 3 51 0 5.56%

Professionals 12 2 10 0 16.67%

RSCC Undergraduates 4,319 127 4,156 36 2.94%

Administrators 6 1 5 0 16.67%

Faculty 107 7 99 1 6.54%

Professionals 39 5 34 0 12.82%I

STUDENT

LEVELS

&

EMPLOYEESin st it u t io n s

TBR c o m m u n it y c o l l e g e s

TOTAL

ENROLL.

9B

FALL 1990

BLACK WHITE OTHER

OBJECT. LONG-RNGE

1990-91 OBJECT.

% %OTHER %OTHER

BLACK RACE RACE

(SEE ****)

CSTCC Undergraduates 7,793 843 6,832 118 10.82% 14.00 15.30»

Administrators 7 1 6 0 14.29% 11.10

Faculty 139 21 117 1 15.11% 16.00

Professionals 56 6 50 0 10.71% 8.00

CLSCC Undergraduates 3,315 148 3,128 39 4.46% 4.40 5.50*

Administrators 22 2 20 0 9.09% 6.70

Faculty 72 6 64 2 8.33% 5.00

Professionals 20 4 15 1 20.00% 16.70

COSCC Undergraduates 3,402 222 3,133 47 6.53% 5.60 5.60*

Administrators 11 3 8 0 27.27% 20.00

Faculty 79 10 66 3 12.66% 16.90

Professionals 22 2 19 1 9.09% 13.50

DSCC Undergraduates 1,993 239 1,733 21 11.99% 14.90 14.90*

Administrators 11 2 9 0 18.18% 20.00

Faculty 45 4 41 0 8.89% 15.60

Professionals 19 5 14 0 26.32% 20.00

JSCC Undergraduates 3,252 443 2,784 25 13.62% 16.75 21.00*

Administrators 14 2 12 0 14.29% 14.30

Faculty 77 8 69 0 10.39% 10.30

Professionals 13 3 10 0 23.08% 23.80

MSCC Undergraduates 2,767 153 2,580 34 5.53% 5.40 5.40*

Administrators 18 2 16 0 11.11% 8.70

Faculty 50 4 54 0 6.90% 5.50

Professionals 11 1 10 0 9.09% 15.40

RSCC Undergraduates 4,928 141 4,734 53 2.86% 3.80 4.20*

Administrators 5 1 4 0 20.00% 11.70

Faculty 120 8 111 1 6.67% 6.50

Professionals 44 5 39 0 11.36% 10.30

lOB

[4A]

TABLE I

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

FALL 1988

in st it u t io n s

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL.

s s c c Undergraduates 3,822

Administrators 25

Faculty 112

Professionals 21

v s c c Undergraduates 3,474

Administrators 9

Faculty 82

Professionals 19

w s c c Undergraduates 3,513

Administrators 9

Faculty 83

Professionals 35

to ta l t b r Undergraduates 33,605

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 122

(WITH SSCC) Faculty 816

Professionals 229

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 29,783

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 97

(W /0 SSCC) Faculty 704

Professionals 208

TBR SYSTEM Administrators 19

STAFF Professionals 19

BLACK WHITE

2,161

15

38

8

169

2

13

3

95

1

7

5

4,293

28

109

36

2,132

13

71

28

3

6

1,615

10

70

13

3,236

7

69

16

3,373

8

73

28

28,907

94

696

188

27,292

84

626

175

16

12

OTHER

46

0

4

0

69

0

0

0

45

0

3

2

405

0

11

5

359

0

7

5

0

1

%

BLACK

56.54%

60.00%

33.93%

38.10%

4.86%

22.22%

15.85%

15.79%

2.70%

11. 11%

8.43%

14.29%

12.77%

22.95%

13.36%

15.72%

7.16%

13.40%

10.09%

13.46%

15.79%

31.58%

IIB

FALL 1989

INSTITUTIONS

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

s s c c Undergraduates 4,216 2,399 1,713 104 56.90%

Administrators 27 15 12 0 55.56%

Faculty 112 34 74 4 30.36%

Professionals 28 14 13 1 50.00%

v s c c Undergraduates 3,670 194 3,412 64 5.29%

Administrators 8 2 6 0 25.00%

Faculty 87 13 74 0 14.94%

Professionals 20 4 16 0 20.00%

w s c c Undergraduates 4,220 150 4,026 44 3.55%

Administrators 9 1 8 0 11.11%

Faculty 88 8 78 2 9.09%

Professionals 35 4 30 1 11.43%

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 37,393 4,854 32,027 512 12.98%

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 134 32 102 0 23.88%

(WITH SSCC) Faculty 838 114 711 13 13.60%

Professionals 260 45 211 4 17.31%

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 33,177 2,455 30,314 408 7.40%

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 107 17 90 0 1

(W /0 SSCC) Faculty 726 80 637 9 11.02%

Professionals 232 31 198 3 13.36%

TBR SYSTEM Administrators 21 3 18 0 14.29%

STAFF Professionals 21 5 15 1 23.81%

STUDENT

LEVELS

12B

FALL 1990 OBJECT.

1990-91

in stitu tio n s

&

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

%OTHER

RACE

s s c c Undergraduates 4 , 7 6 3 2 , 5 9 9 2 , 0 5 3 111 5 4 . 5 7 % 4 9 . 5 0

Administrators 2 7 1 3 1 4 0 4 8 . 1 5 % 5 6 . 4 0

Faculty 1 0 4 31 6 8 5 2 9 . 8 1 % 6 5 .1 0

Professionals 2 8 18 9 1 6 4 . 2 9 % 5 8 . 5 0

v s c c Undergraduates 4 , 1 6 0 2 3 6 3 8 6 9 55 5 .6 7 % 6 .4 0

Administrators 8 2 6 0 2 5 . 0 0 % 1 8 .2 0

Faculty 91 1 4 77 0 1 5 .3 8 % 1 5 .8 0

Professionals 2 3 5 1 8 0 2 1 . 7 4 % 2 5 .0 0

w s c c Undergraduates 4 , 5 6 7 1 3 8 4 , 3 8 2 4 7 3 .0 2 % 2 .8 0

Administrators 8 1 7 0 1 2 .5 0 % 9 .0 0

Faculty 9 6 1 0 8 4 2 1 0 .4 2 % 9 .2 0

Professionals 3 6 4 31 1 1 1 .1 1 % 1 0 .8 0

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 40,940 5 , 1 6 2 3 5 , 2 2 8 5 5 0 1 2 . 6 1 %

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 131 2 9 1 0 2 0 2 2 . 1 4 %

(WITH SSCC) Faculty 881 1 1 6 7 51 1 4 1 3 . 1 7 %

Professionals 2 7 2 5 3 2 1 5 4 1 9 .4 9 %

TOTAL TBR Undergraduates 3 6 , 1 7 7 2,563 33,175 439 7.08%

COMMUNITY

COLLEGES Administrators 104 1 6 8 8 0 15.38%

(W /0 SSCC) Faculty 777 85 683 9 10.94%

Professionals 244 35 206 3 14.34%

TBR SYSTEM Administrators 2 0 4 16 0 2 0 . 0 0 % 13.30

STAFF Professionals 21 6 1 3 2 28.57% 28.50

(SEE

LONG-RNGE

OBJECT.

%OTHER

RACE

59.30*

9.10*

2.90*

13B

[5A]

TABLE I

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

FALL 1988

INSTITUTIONS

)ENT LEVELS

EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

Undergraduates 6,199 689 5,295 215 11.11%

Graduates 1,327 81 1,192 54 6.10%

Total 7,526 770 6,487 269 10.23%

Administrators 114 11 101 2 9.65%

Faculty 284 18 256 10 6.34%

Professionals 101 16 82 3 15.84%

Undergraduates 18,770 863 17,479 428 4.60%

Graduates 5,158 268 4,460 430 5.20%

Law 462 36 420 6 7.79%

Vet. Medicine 178 2 176 0 1.12%

Total 24,568 1,169 22,535 864 4.76%

Administrators 324 25 297 2 7.72%

Faculty 1,482 50 1,345 87 3.37%

Professionals 788 41 688 59 5.20%

Undergraduates 4,367 598 3,645 124 13.69%

Graduates 286 11 269 6 3.85%

Total 4,653 609 3,914 130 13.09%

Administrators 64 3 61 0 4.69%

Faculty 234 4 216 14 1.71%

Professionals 58 7 50 1 12.07%

Undergraduates 326 34 286 6 10.43%

Graduates 244 25 180 39 10.25%

Dentistry 318 15 285 18 4.72%

Medicine 608 28 539 41 4.61 %

Pharmacy 276 12 255 9 4.35%

Total 1,772 114 1,545 113 6.43%

Administrators 142 7 131 4 4.93%

Faculty 756 36 670 50 4.76%

Professionals 1,343 118 1,139 86 8.79%

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

UTC

UTK”

UTM

UTMHSC

14B

FALL 1989

in s t it u t io n s

)ENT LEVELS

EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

Undergraduates 6,595 672 5,688 235 10.19%

Graduates 969 53 875 41 5.47%

Total 7,564 725 6,563 276 9.58%

Administrators 114 10 102 2 8.77%

Faculty 282 17 254 11 6.03%

Professionals 98 15 82 1 15.31%

Undergraduates 19,068 900 17,709 459 4.72%

Graduates 5,794 313 4,984 497 5.40%

Law 479 39 438 2 8.14%

Vet. Medicine 171 4 165 2 2.14%

Total 25,512 1,256 23,296 960 4.92%

Administrators 335 27 306 2 8.06%

Faculty 1,411 56 1,271 84 3.97%

Professionals 797 46 682 69 5.77%

Undergraduates 4,716 630 3,951 135 13.36%

Graduates 392 26 358 8 6.63%

Total 5,108 656 4,309 143 12.84%

Administrators 60 3 57 0 5.00%

Faculty 238 6 221 11 2.52%

Professionals 59 10 48 1 16.95%

Undergraduates 315 43 263 9 13.65%

Graduates 245 19 179 47 7.76%

Dentistry 307 12 276 19 3.91%

Medicine 599 44 508 47 7.35%

Pharmacy 281 16 255 10 5.69%

Total 1,747 134 1,481 132 7.67%

Administrators 132 5 123 4 3.79%

Faculty 772 41 687 44 5.31 %

Professionals 1,376 127 1,146 103 9.23%

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

UTC

UTK*

UTM

UTMHSC

i

in stitu tio n s

STUDENT

LEVELS

&

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL.

15B

FALL 1990

BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

OBJECT.

1990-91

%OTHER

RACE

LONG-RNGE

OBJECT.

%OTHER

RACE

(SEE ****)

university o f TENNESSEE

UTC

UTK-

UTM

UTMHSC

Undergraduates 6,698 677 5,774 247 10.11% 15.00 16.80

Graduates 1,027 65 909 53 6.33% 10.80 15.80

Total 7,725 742 6,683 300 9.61%

Administrators 112 9 102 1 8.04% 9.30

Faculty 285 18 255 12 6.32% 7.30

Professionals 71 15 55 1 21.13% 15.20

Undergraduates 19,537 997 18,035 505 5.10% 7.50 10.50

Graduates 5,882 302 5,038 542 5.13% 5.10 6.00

Law 471 36 431 4 7.64% 7.40 7.40

Vet. Medicine 165 6 155 4 3.64% 4.30 8.70

Total 26,055 1,341 23,659 1,055 5.15%

Administrators 312 27 285 0 8.65% 6.70

Faculty 1,166 49 1,053 64 4.20% 4.20

Professionals 480 35 431 14 7.29% 6.50

Undergraduates 5,050 747 4,173 130 14.79% 17.00 18.40

Graduates 313 23 285 5 7.35% 9.50 14.70

Total 5,363 770 4,458 135 14.36%

Administrators 61 4 57 0 6.56% 5.10

Faculty 238 9 216 13 3.78% 1.60

Professionals 55 8 46 1 14.55% 9.50

Undergraduates 341 45 288 8 13.20% 11.20 14.20

Graduates 264 26 177 61 9.85% 8.10 10.80

Dentistry 301 17 260 24 5.65% 5.90 8.80

Medicine 591 52 496 43 8.80% 5.30 8.90

Pharmacy 288 25 255 8 8.68% 7.00 8.40

Total 1,785 165 1,476 144 9.24%

Administrators 131 6 121 4 4.58% 7.00

Faculty 591 26 520 45 4.40% 3.50

Professionals 534 81 404 49 15.17% 11.90

16B

[6A]

TABLE 1

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNESSEE

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

INSTITUTIONS

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK

FALL 1988

WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

UTMCK Administrators 102 2 100 0 1.96%

Faculty 111 1 99 11 0.90%

Professionals 1,276 18 1,235 23 1.41%

INSTIT. OF Administrators 47 2 45 0 4.26%

AGRIC. Faculty 269 3 263 3 1.12%

Professionals 553 24 519 10 4.34%

UT-WIDE Administrators 95 3 92 0 3.16%

ADMIN. Professionals 174 10 164 0 5.75%

TOTAL Undergraduates 29,662 2,184 26,705 773 7.36%

UT Graduates 7,015 385 6,101 529 5.49%

Law 462 36 420 6 7.79%

Dentistry 318 15 285 18 4.72%

Medicine 608 28 539 41 4.61%

Pharmacy 276 12 255 9 4.35%

Vet. Medicine 178 2 176 0 1.12%

Total 38,519 2,662 34,481 1,376 6.91 %

Administrators 888 53 827 8 5.97%

Faculty 3,136 112 2,849 175 3.57%

Professionals 4,293 234 3,877 182 5.45%

THEC Administrators 12 2 10 0 16.67%

STAFF Professionals 5 0 5 0 0.00%

GRAND Undergraduates 118,730 16,098 99,829 2,803 13.56%

TOTAL Graduates 15,754 1,248 13,430 1,076 7.92%

(WITH TSU Law 871 67 792 12 7.69%

& SSCC) Dentistry 318 15 285 18 4.72%

Medicine 837 52 727 58 6.21%

Pharmacy 276 12 255 9 4.35%

Vet. Medicine 178 2 176 0 1.12%

Total 136,964 17,494 115,494 3,976 12.77%

Administrators 1,419 139 1,265 15 9.80%

Faculty 6,615 497 5,770 348 7.51%

Professionals 5,437 444 4,793 200 8.17%

i

17B

FALL 1989

JSTITUTIONS

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK

UTMCK Administrators 109 2

Faculty 115 1

Professionals 1,359 27

INSTIT. OF Administrators 47 2

AGRIC. Faculty 263 4

Professionals 565 26

UT-WIDE Administrators 98 4

ADMIN. Professionals 160 10

TOTAL Undergraduates 30,694 2,245

UT Graduates 7,400 411

Law 479 39

Dentistry 307 12

Medicine 599 44

Pharmacy 281 16

Vet. Medicine 171 4

Total 39,931 2,771

Administrators 895 53

Faculty 3,081 125

Professionals 4,414 261

THEC Administrators 12 2

STAFF Professionals 8 2

GRAND Undergraduates 125,978 17,318

TOTAL Graduates 16,721 1,245

(WITH TSU Law 918 69

& SSCC) Dentistry 307 12

Medicine 825 68

Pharmacy 281 16

Vet. Medicine 171 4

Total 145,201 18,732

Administrators 1,447 152

Faculty 6,652 533

Professionals 5,653 494

%

WHITE OTHER BLACK

107 0 1.83%

104 10 0.87%

1,306 26 1.99%

45 0 4.26%

256 3 1.52%

528 11 4.60%

94 0 4.08%

150 0 6.25%

27,611 838 7.31%

6,396 593 5.55%

438 2 8.14%

276 19 3.91%

508 47 7.35%

255 10 5.69%

165 2 2.34%

35,649 1,511 6.94%

834 8 5.92%

2,793 163 4.06%

3,942 211 5.91%

10 0 16.67%

6 0 25.00%

105,530 3,130 13.75%

14,263 1,213 7.45%

843 6 7.52%

276 19 3.91%

694 63 8.24%

255 10 5.69%

165 2 2.34%

122,026 4,443 12.90%

1,283 12 10.50%

5,788 331 8.01%

4,931 228 8.74%

STUDENT

LEVELS

18B

FALL 1990

in st it u t io n s

&

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

%OTHE

RACE

UTMCK Administrators 114 2 112 0 1.75% 2.50

Faculty 87 1 76 10 1.15% 4.30

Professionals 1,204 25 1,153 26 2.08% 6.60

INSTIT. OF Administrators 44 1 43 0 2.27% 5.00

AGRIC. Faculty 268 3 263 2 1.12% 3.40

Professionals 541 24 509 8 4.44% 7.40

UT-WIDE Administrators 94 5 89 0 5.32% 6.40

ADMIN. Professionals 157 11 146 0 7.01% 5.30

TOTAL Undergraduates 31,626 2,466 28,270 890 7.80%

UT Graduates 7,486 416 6,409 661 5.56%

Law 471 36 431 4 7.64%

Dentistry 301 17 260 24 5.65%

Medicine 591 52 496 43 8.80%

Pharmacy 288 25 255 8 8.68%

Vet. Medicine 165 6 155 4 3.64%

Total 40,928 3,018 36,276 1,634 7.37%

Administrators 868 54 809 5 6.22%

Faculty 2,635 106 2,383 146 4.02%

Professionals 3,042 199 2,744 99 6.54%

THEC Administrators 11 2 9 0 18.18% 15.80

STAFF Professionals 8 2 6 0 25.00% 15.80

GRAND Undergraduates 131,432 18,048 110,214 3,170 13.73%

TOTAL Graduates 16,975 1,367 14,269 1,339 8.05%

(WITH TSU Law 901 64 831 6 7.10%

& SSCC) Dentistry 301 17 260 24 5.65%

Medicine 827 81 690 56 9.79%

Pharmacy 288 25 255 8 8.68%

Vet. Medicine 165 6 155 4 3.64%

Total 150,889 19,608 126,674 4,607 12.99%

Administrators 1,393 149 1,234 10 10.70%

Faculty 6,279 523 5,440 316 8.33%

Professionals 4,320 447 3,755 118 10.35%

OBJECT. LONG-RNGE

1990-91 OBJECT.

%OTHER

RACE

(SEE ****)

1

19B

[7A]

TABLE I

FALL 1988 THROUGH FALL 1990 HEADCOUNT ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT IN TENNFSSFF

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND ENROLLMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OBJECTIVES

INSTITUTIONS

GRAND

TOTAL

(W /0 TSU

& SSCC)

STUDENT LEVELS

& EMPLOYEES

Undergraduates

Graduates

Law

Dentistry

Medicine

Pharmacy

Vet. Medicine

Total

Administrators

Faculty

Professionals

TOTAL ENROLL.

108,468

14,841

871

318

837

276

178

125,789

1,360

6,175

5,293

FALL 1988

BLACK WHITE OTHER

9,583

986

67

15

52

12

2

10,717

99

301

338

96,363

12,823

792

285

727

255

176

111,421

1,247

5,564

4,756

2,522

1,032

12

18

58

9

0

3,651

14

310

199

%

BLACK

8.83%

6.64%

7.69%

4.72%

6.21%

4.35%

1.12%

8.52%

7.28%

4.87%

6.39%

FALL 1989

STUDENT LEVELS %

INSTITUTIONS & EMPLOYEES TOTAL ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER BLACK

GRAND Undergraduates 115,320 10,492 102,015 2,813 9.10%

TOTAL Graduates 15,801 987 13,657 1,157 6.25%

(W /O TSU Law 918 69 843 6 7.52%

& SSCC) Dentistry 307 12 276 19 3.91%

Medicine 825 68 694 63 8.24%

Pharmacy 281 16 255 10 5.69%

Vet. Medicine 171 4 165 2 2.34%

Total 133,623 11,648 117,905 4,070 8.72%

Administrators 1,384 114 1,258 12 8.24%

Faculty 6,207 331 5,575 301 5.33%

Professionals 5,506 386 4,894 226 7.01 %

STUDENT

LEVELS

21B

FALL 1990

INSTITUTIONS

&

EMPLOYEES

TOTAL

ENROLL. BLACK WHITE OTHER

%

BLACK

GRAND Undergraduates 120,322 11,172 106,281 2,869 9.29%

TOTAL Graduates 15,929 1,056 13,600 1,273 6.63%

(W /0 TSU Law 901 64 831 6 7.10%

& SSCC) Dentistry 301 17 260 24 5.65%

Medicine 827 81 690 56 9.79%

Pharmacy 288 25 255 8 8.68%

Vet. Medicine 165 6 155 4 3.64%

Total 138,733 12,421 122,072 4,240 8.95%

Administrators 1,331 114 1,207 10 8.56%

Faculty 5,838 325 5,226 287 5.57%

Professionals 4,181 339 3,725 117 8.11%

NOTE: Employment date for Tennessee Board of Regents institutions are based upon October revised budgets. UT data as of October 1,

1990. Unrestricted full-time employment data have been included for 1990. For UT fall 1988 and 1989 data included all employees.

* Refinement based upon 1986 projections. If met, college-going desparity will have been addressed.

Includes UTSI.

Beginning fall 1987 at TSU, reclassification of some positions was made from administrators to professional.

Other race here means black for all institutions except TSU and SSCC. For TSU and SSCC it means white.