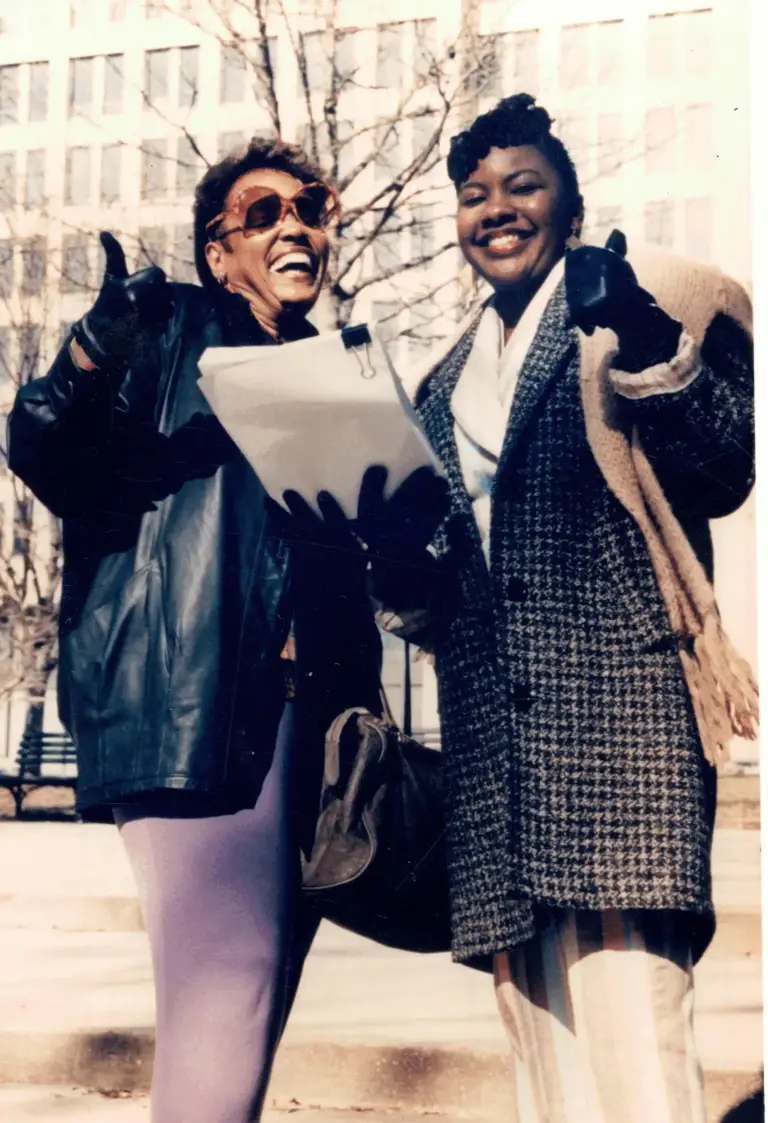

Haynes v. Shoney's, 1993 - 1 of 2

Photograph

January 1, 1993

Photo by Johnson Publishing Company

Cite this item

-

Photograph Collection, Economic Justice. Haynes v. Shoney's, 1993 - 1 of 2, 1993. fe205d0a-ba54-ef11-a317-0022481d08e0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/18453157-5473-4cdb-9cd9-7b4b014133f9/haynes-v-shoneys-1993-1-of-2. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

X-TIKA:Parsed-By org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser X-TIKA:Parsed-By-Full-Set org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser Content-Length 1961307 Content-Type image/jpeg