Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvester Company Petition for a Writ of Certiorari with Appendix

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvester Company Petition for a Writ of Certiorari with Appendix, 1974. d15765a9-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/18530b6c-0997-412a-85d2-6578bfab9e5e/waters-v-wisconsin-steel-works-of-international-harvester-company-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-with-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

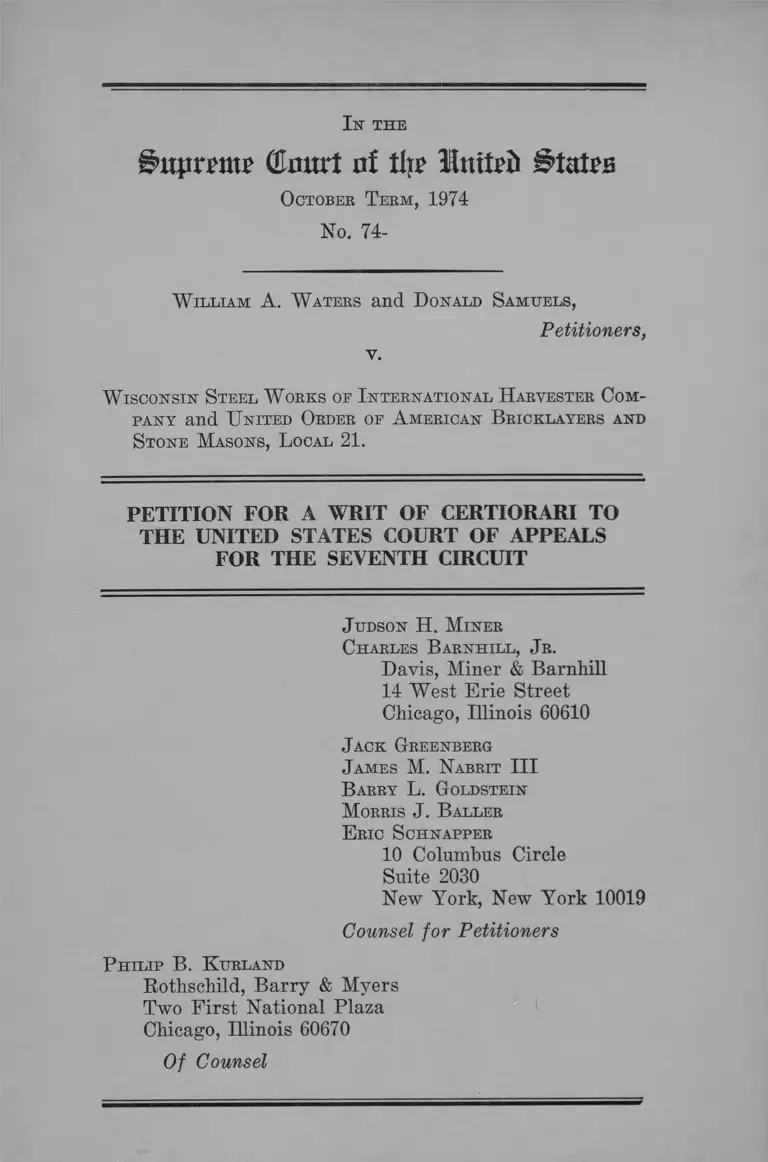

I n t h e

g’upratw (Enurt of tljf llnitfJi States

October T erm, 1974

No. 74-

W illiam A. W aters and D onald Samuels,

Petitioners,

v.

W isconsin Steel W orks of International H arvester Com

pany and U nited Order of A merican B ricklayers and

Stone M asons, L ocal 21.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Judson H. M iner

Charles B arnhill, J r .

Davis, Miner & Barnhill

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

J ack Greenberg

James M. N abrit III

B arry L. Goldstein

M orris J. B aller

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Petitioners

P hilip B. K urland

Rothschild, Barry & Myers

Two First National Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60670

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinion Below ......................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ........................................ 2

Statement of the Case ............................ 5

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................................... 7

I. The Decision of the Court of Appeals That Sec

tion 703(h) of Title VII Limits the Remedies

Provided by Section 1981 Is Inconsistent With

the Decision of This Court in Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co.................................................... 11

II. The Decision of the Court of Appeals That Sec

tion 703(h) Protects Seniority Systems Which

Perpetuate the Effects of Past Discrimination

Is In Conflict With the Decisions of Other Cir

cuits ............................................................................. 15

III. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Limiting

Waters’ Right to Back Pay Is In Conflict With

Decisions of the Third and Fourth Circuits ..... 27

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 30

A ppendix—

Opinion of the Court of Appeals...................................... la

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying Rehearing..... 21a

Order of the District C ourt............... 23a

PAGE

11

T able of A uthorities:

Cases: page

Afro-American Patrolmen’s League v. Duck, 366

F. Supp. 1095 (N.D. Ohio 1973), aff’d in pertinent

part 503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974) .............................. 18

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody No. 74-389, cert, granted

December 16, 1974 .......................... ................................ 9

Alexander v. Oardner-Denver Co., 415 TJ.S. 36

(1974) ....................................................................9,13,14,15

Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp. 1134 (S.D. A la .);

aff’d per curiam 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972); cert.

denied 412 U.S. 909 (1973) ............................................ 18

Atlantic Maintenance Co. v. NLRB, 305 F.2d 604 (3rd

Cor. 1962), enf’g 134 NLRB 1328 (1961) ................... 21

Brady v. Bristol-Myers Co., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir.

1972) ................................................................................. 12

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil Service

Comm., 497 F.2d 1113 (2nd Cir. 1974) ................... 18

Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O’Neil, 324 U.S. 697 (1945) 29

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972) cert, denied 409 U.S. 982 (1972) 11

Chance v. Board of Examiners, No. 70 Civ. 4141 (S.D.

N.Y. Feb. 7, 1975) .......................................................... 20

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971)

cert, denied 404 U.S. 859 (1971) .................................... 14

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan, 41 L.Ed.2d 1 (1974) 24

Delay v. Carling Brewing Company, 9 EPD ft 9877

(N.D. Ga. 1974) ............................. ................................ 19

Dobbins v. Electrical Workers Local 212, 292 F.Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968) atf’d as later modified, 472 F.2d

634 (6th Cir. 1973) .......................................................... 18

Ill

EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189, 311 F. Supp.

PAGE

468 (S.D. Ohio 1970) vac’d on other grounds 438

F.2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971) cert, denied 404 U.S. 832

(1971) ............................................................................ 18

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, O.T. No.

74-728, cert, pending ..................................................2, 9,18

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974) cert, denied 43 LW 3330 (1974) ....... 18

Grates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., 492 F.2d 292 (1974) ....22, 24

Golden State Bottling Co. v. NLRB, 38 L.Ed.2d 388

(1973), afUg 467 F.2d 164 (9th Cir. 1972) ............... 21

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .....9, 23, 24

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d 641 (5th

Cir. 1974) .......................................................................12,14

Hackett v. McGuire Brothers, Inc., 445 F.2d 442 (3rd

Cir. 1971) ......................................................................... 11

Harper v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 359

F. Supp. 1187 (D. Md. 1973), aff’d sub nom. Harper

v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973) .................. 18

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 (6th

Cir. 1973) ......................................................................... 21

Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v. Electrical Work

ers, Local 327,------ F .2d------- , 9 FEP Cases 117 (3rd

Cir. 1975) ....................................................................... 17, 20

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., O.T. 1974,

No. 73-1543 .................................................. 13

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) .......................... 29

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 7 EPD 9066

(W.D. Okla. 1973) ............... 10

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .............................. 14

PAGE

Jnrinko v. Edwin L. Wiegand Co., 477 F.2d 1038, va

cated and remanded on other grounds, 414 U.S. 970

reinstated 497 F.2d 403 (3rd Cir. 1974) ...............19, 24,

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) cert.

denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ..................................... .

Long v. Ford Motor Company, 496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir.

1974) ..................................................................................

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972) ...................

Loy v. City of Cleveland, 8 FEP Cases 614 (N.D. Ohio

1974) .................................................................................

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)

Macklin v. Spector Motor Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F.2d 979 (D.C. 1973) ......................................................

Meadows v. Ford Motor Company,------ F.2d —— , 9

EPD 9907 (6th Cir. 1975) .................................. 17,19,

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) .......................13,

NLRB v. Cone Brothers Contracting Co., 317 F.2d 3

(5th Cir. 1963) ................................................................

NLRB v. Lamar Creamery Co., 246 F.2d 3, (5th Cir.

1957), enf’g 115 NLRB 1113 (1956) ..........................

NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., 304 U.S. 333

(1938) ...............................................................................

NLRB v. Rutter-Rex Mfg. Co., 396 U.S. 258 (1969) ....

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 495 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ..............................................................21,

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177 (1941)

Phillips v. Martin-Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971)

28

20

12

9

18

9

12

24

14

21

21

21

21

24

21

9

Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1969) ........................... ............................................. 20

V

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971) , cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ............. 21

Rock v. Norfolk & Western Rwy. Co., 473 F.2d 1344

(4 Cir. 1973), cert, denied 412 U.S. 933 (1973) ....... 24

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972) ................................................................................. 18

Southport Co. v. NLRB, 315 U.S. 100 (1942) .............. 21

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ............................................................................... 14

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ................................................................... 14

United Packinghouse, etc. Union v. NLRB, 416 F.2d

1126 (D.C. Cir. 1969), cert, denied 396 U.S. 903

(1969) ............................................................................... 14

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2nd Cir. 1971) ..................................................... 21

United States v. Borden Co., 308 U.S. 188 (1939) ....... 14

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry., 471 F.2d 582

(4th Cir. 1972) cert, denied 411 U.S. 939 (1973) ....... 21

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 7 EPD 9167

(N.D. Ga. 1974) issuing decree on remand from 474

F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973) .............................................. 10,21

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5th Cir. 1971) cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972) 21

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ....... 24

LTnited States v. Navajo Freight Lines, Inc., C.A. No.

116-MNL (C.D. Cal.) (supplemental order to consent

decree entered January 15, 1973) ....... 10

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973) .................. :........ ...... ....................... . 21

PAGE

VI

United States v. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc., C.A. No.

C-143-WS-71 (M.D.N. Car.) (consent decree entered

October 31, 1972) ....... ....................................................

United States v. Roadway Express, Inc., C.A. No.

C-68-321 (N.D. Ohio) (consent decree entered Sep

tember 1,1970) partially reported at 2 EPD 10,295

p. 1176 affirmed, 457 F.2d 854 (6th Cir. 1972) ........... 10

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969), rev’ing 280 F. Snpp. 719

(E.D. No. 1968) ................................................18,19, 23, 24

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc,, 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971) 24

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476 (7th

Cir. 1970), cert, denied 400 IT.S. 911 (1970) ........... 5

Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America, 369

F. Snpp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1974) .............................. 14,17,19

Williams v. Albemarle City Board of Education,

____F .2d------- 8 EPD 9820 (4th Cir. 1974) ............ 28, 29

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ............................................................ 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...........................................................passim

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................................................. 13

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. [Title V II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964] ...................................................passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) [§ 703(a) of Title VII] ....3,23,24

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c) ...............................-----.......... -.... - 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) [§ 703(h) of Title VII] .....passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j) [§703(j) of Title V II] ........... 14

PAGE

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. [Title VIII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1968] ........................................................ 14

National Labor Relations Act [29 U.S.C. §§ 151

et seq.] .......................... ................................................... 21

Other Authorities:

Burean of Labor Statistics: The Employment Situa

tion, Jan. 1975 .................................................................. 8

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objec

tive Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv.

L. Rev. 1589 (1969) .............................. ......................... 20

H. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 64-66 ...............24, 25

110 Cong. Rec. 2726 (1964) (Remarks of Rep. Dowdy) 25

110 Cong. Rec. 2728 (1964) ....................................... 25

110 Cong. Rec. 2804 (1964) .............................................. 25

110 Cong. Rec. 6992 (April 8, 1964) .............................. 23

110 Cong. Rec. 7207 et seq. (1964).................................... 25

110 Cong. Rec. 12,723 (1964) ............................................ 26

110 Cong. Rec. 13650-13652 (1964) ............................... 14

110 Cong. Rec. 14,511 (1964) .................... 26

110 Cong. Rec. 15,896 (1964) ....................................... 26

118 Cong. Rec. 3462 (daily ed. March 6, 1972) ............... 24

Vll

PAGE

42 TJ.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) [§ 706(g) of Title VII] .....4,23,24

IN THE

S>uprrmf (Eourl of tlj? lit t le Stales

October T erm, 1974

No. 74-

W illiam A. W aters and D onald Samuels,

v.

Petitioners,

W isconsin S teel W orks of I nternational H arvester, Com

pany and U nited Order op A merican B ricklayers and

S tone M asons, L ocal 21.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, William A. Waters and Donald Samuels,

respectfully pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment and opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit entered in this proceeding

on August 26, 1974.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, reported at 502

F.2d 1309, is reprinted in the Appendix hereto at pp. la-

20a. The order of the Court of Appeals denying peti

tioners’ Petition for Rehearing is set out in the Appendix

at pp. 21a-22a. The Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law,

and Order of the District Court, which axe not reported,

are set out in the Appendix at pp. 23a-29a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

August 26, 1974. Petitioners’ timely Petition for Rehear

ing was denied on November 26, 1974. This Court’s juris

diction is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Do the limitations of section 703(h) of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, apply to or restrict the

remedies available under 42 U.S.C. § 1981!

2. Does section 703(h) preclude the district courts in

Title VII actions from providing a remedy for a seniority

system which perpetuates the effects of past discrimination

and has a discriminatory impact on black employees and

job applicants!*

3. Is an aggrieved employee’s right to additional back

pay cut off when he declines to accept a job offer from the

defendant employer, where (a) the job offered is less

desirable than the job to which he is entitled, (b) the job

offered is less desirable than the job he then holds, and

(c) the offer is conditioned on a waiver by the employee

of some or all of his remedies for past discrimination!

Statutory Provisions Involved

The pertinent sections of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., as amended, provide:

* See Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, No. 74-728.

3

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his

status as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 703(c)-, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(c):

It shall he an unlawful employment practice for a

labor organization—

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership, or

otherwise to discriminate against, any individual be

cause of his race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership or

applicants for membership, or to classify or fail or

refuse to refer for employment any individual, in any

way which would deprive or tend to deprive any in

dividual of employment opportunities, or would limit

such employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee or as an applicant for

employment, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin..

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a):

4

Notwithstanding any other provision of this title, it

shall not he an unlawful employment practice for an

employer to apply different standards of compensa

tion, or different terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona fide seniority or merit

system, or a system which measures earnings by quan

tity or quality of production or to employees who work

in different locations, provided that such differences

are not the result of an intention to discriminate be

cause of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g):

I f the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an

unlawful employment practice charged in the com

plaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from en

gaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may he appropriate,

which may include, hut is not limited to, reinstatement

or hiring of employees, with or without hack pay (pay

able by the employer, employment agency, or labor or

ganization, as the case may be, responsible for the

unlawful employment practice), or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate. . . . No order of

the court shall require the admission or reinstatement

of an individual as a member of a union, or the hiring,

reinstatement, or promotion of an individual as an em

ployee, or the payment to him of any hack pay, if such

individual was refused admission, suspended, or ex

pelled, or was refused employment or advancement or

was suspended or discharged for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin or in violation of section 704(a).

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h):

5

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sne, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

Statement of the Case

This action was filed in December, 1968, in the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

by two black bricklayers alleging discrimination on the

basis of race by the Wisconsin Steel Works of the Inter

national Harvester Company and the United Order of

American Bricklayers and Stone Masons, Local 21, in viola

tion of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Eights Act and of 42

U.S.C. §1981. Plaintiff Waters alleged that he was initially

denied employment on the basis of race, and that he was

subsequently hired for a short period of time but then laid

off because he had less seniority than whites hired during

the period when Wisconsin Steel refused to hire blacks.

Plaintiff Samuels alleged that he had been denied employ

ment because Wisconsin Steel gave preference to appli

cants who had previously worked for the company during

the period when it employed only whites.

The District Court1 upheld plaintiffs’ factual allegations

regarding the employment practices of Wisconsin Steel

1 The district court had earlier dismissed the action on proce

dural grounds; the decision of the district court was reversed

and the case remanded, Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427

F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied 400 U.S. 911 (1970).

The Civil Eights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981, provides:

6

and Local 21. It held that prior to April, 1964,2 Wisconsin

Steel maintained a policy of racial discrimination in the

hiring of bricklayers and hired only white applicants.3

The District Court further found that after 1964 Wiscon

sin Steel, in laying off and recalling employees, had given

preferential treatment to employees hired during the “white

only” period, including white employees who had no con

tractual seniority rights because those rights had been

waived in return for severance pay. The District Court

concluded that this preferential treatment had the effect of

continuing the impact of Wisconsin Steel’s past policy of

discrimination, and directly injured plaintiffs (24a-27a).

The record revealed that the seniority system and prefer

ences guaranteed that any black bricklayer at Wisconsin

Steel would be the first laid off, and that virtually all

bricklayers hired would be white. Plaintiffs’ qualifications

were not disputed; Waters and Samuels had twenty and

thirteen years of experience, respectively, as bricklayers.

Among the white bricklayers recalled ahead of Waters on

grounds of seniority were bricklayers hired after Waters

had been rejected for employment because of his race.

The District Court held that these practices constituted

a violation of Title VII and of section 1981. It ruled that

the defendants’ seniority system, as well as the preferen

2 Petitioner Waters had first sought employment at Wisconsin

Steel in the Fall, 1957.

3 Specifically, the district court found that black bricklayers

bad applied unsuccessfully for work on several occasions be

ginning as early as 1949, but that Wisconsin Steel did not hire

a black bricklayer until April 1964; furthermore black laborers

in Wisconsin Steel’s mason department had sought transfer to

Wisconsin Steel’s apprentice program but were denied admis

sion, supposedly on the basis of their age, even though whites

were admitted into the program who were the same age as some

of the black rejected applicants (24a-27a).

7

tial treatment for whites whose contractual seniority rights

had been waived, had its genesis in a period of racial dis

crimination and was thus not a “bona fide” seniority sys

tem under Title VII. The District Court awarded $5,000

in back pay to Waters and Samuels, and directed Wiscon

sin Steel to offer both plaintiffs employment (27a-29a).

On appeal the Seventh Circuit upheld the District Court’s

findings of fact, but reversed on the ground that the district

court was powerless to award most of the relief granted.

The Court of Appeals ruled, as a matter of law, (1) that a

contractual seniority system as well as an informal prefer

ence for employees whose seniority rights had expired,

even though they perpetuated the effect of past discrimina

tion, were absolutely protected from judicial scrutiny under

Title V II by section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h), (2) that

the limitations placed by section 703(h) on remedies under

Title V II also applied to 42 U.S.C. §1981, (3) that the

company could give white employees who had waived their

seniority rights preference over plaintiff Samuels, although

to do so over Waters was unlawful, and (4) that plaintiff

Waters forfeited his right to any further back pay when,

while his claim was pending, Wisconsin Steel offered him

a job if he would waive his claim for retroactive seniority

and otherwise prejudice his case, and he refused to take it

(la-20a).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case arises from a problem of discrimination which

has long obstructed economic opportunity for blacks—the

practice of hiring blacks last when employment is rising

and firing blacks first when the workforce is reduced. The

fact that minority workers were the most recently hired is

seized upon by employers and unions as a justification for

8

laying off those workers before whites with greater com

pany seniority. That in many firms most black employees

were hired only in the last few years is a result of open

and avowed discrimination prior to 1964, and of the con

tinuation of that discrimination in more subtle but equally

effective forms thereafter. This “last hired, first fired”

form of discrimination is one of the primary reasons for

the chronically higher level of unemployment among non

whites compared to white workers.

Under ordinary economic conditions the workforce at

any given plant or office expands and contracts in response

to seasonal variation in demand and the success or prob

lems of the particular firm. The abolition of “ last hired,

first fired” discrimination against blacks is thus a matter

of continuing concern. The problem is of particular

importance now in a time of serious economic dislocation,

with millions of workers being fired, laid off or furloughed

due to falling production. In the last month alone unem

ployment rose by 930,000, and over the last year unemploy

ment rose substantially faster among non-whites than

among whites.4 When the economy begins to recover from

its present difficulties and employment begins to rise, the

“ last hired, first fired” principle will prevent black workers

from participating fully in that new prosperity.

The decision of the Seventh Circuit strips the district

courts of any power to remedy “last hired, first fired”

discrimination. The Court of Appeals held that an em

ployer in laying off employees could give preferential

treatment to whites because they worked for the firm

longer, and could in hiring give preference to whites be

cause they had worked for the firm before. The Court of

4 See generally: Bureau of Labor Statistics, The Employment

Situation, January, 1975.

9

Appeals did not deny that this practice served to per

petuate the effects of past discrimination, but held that

such discrimination enjoyed absolute immunity from legal

attack because of Section 703(h) of Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act. The decision deprives district courts in

that circuit of any ability to fashion fair and effective

relief appropriate to the circumstances of each case for

such “ last hired, first fired” discrimination. The decision

of the Court of Appeals is squarely in conflict with the

decisions of this Court and other courts of appeals, and

with the policies and language of Title VII and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981.

Previously this Court has resolved questions arising

under Title VII regarding procedure5 and standards of

proof.6 The critical issues of employment discrimination

law at present involve remedies.7 This case presents

important questions involving the scope of remedial au

thority vested in the district courts once discrimination

has been established.8 The Court of Appeals decision

5 See, e.g., Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ; and Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972).

6 See, e.g., McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973); Phillips v. Martin-Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971) ;

and Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

7 See e.g., Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, No. 74-389 cert,

granted December 16, 1974; and Franks v. Bowman Transporta

tion Company, No. 74-728 cert, pending.

8 This Court has spoken generally concerning the broad power

of the f ederal courts to eliminate employment discrimination:

Congress enacted Title V II . . . to assure equality of employ

ment opportunities by eliminating those practices and devices

that discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex

or national origin.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra at 44; see also McDon

nell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra at 800; Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., supra at 429-430.

10

resolved these questions in a manner which not only

severely limits the district court’s power hut also would

restrict the ability of the Department of Justice9 and the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission10 to obtain

effective relief for victims of unlawful employment dis

crimination.

That the use of seniority as a criterion in layoffs and

hiring is of unusual importance does not, of course, mean

that this Court must adopt a per se rule that the applica

tion of such a standard is always, or never permissible.

The use of seniority takes a variety of forms— contractual

labor-management agreements, written or informal com

pany policies, and ad hoc rules. Different minority em

ployees present different problems—some were denied jobs

on account of race before Title VII became law in 1965,

other applicants were rejected for this reason after 1965,

and still others did not apply to work for an employer

until after the employer had ended such overt discrimina

9 In several Title V II cases, the United States Department of

Justice has secured decrees granting compensatory seniority to

unlawfully rejected applicants. See, e.g., United States v. Road

way Express, Inc., C.A. No. C-68-321 (N.D. Ohio) (consent decree

entered September 1, 1970), partially repeated at 2 EPD 1)10,295

p. 1176 affirmed, 457 F.2d 854 (6th Cir. 1972) ; United States v.

Navajo Freight Lines, Inc., C.A. No. 72-116-MNL (C.D. Cal.)

(supplemental order to consent decree entered January 15, 1973) ;

United States v. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc., C.A. No. C-143-WS-

71 (M.D.N. Car.) (consent decree entered October 31, 1972);

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 7 EPD 1)9167 (N.D. Ga.

1974), issuing decree on remand from 174 F.2d 906 (5th Cir.

1973) ; Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 7 EPD 1)9066,

p. 6500 (W .D. Okla. 1973).

10 EEOC’s authority derives solely from Title V II. Thus, a

limitation read into Title V II may hamstring EEOC in all its

proceedings. The EEOC has filed 306 pending lawsuits, 174 of

which seek relief from discrimination in hiring [information sup

plied by EEOC Litigation Services Branch, December 5, 1974],

And EEOC has thousands of pending administrative charges of

discrimination involving refusals to hire.

11

tion. The instant case involves several different types of

problems.11 Different situations may require different

answers, but the decision below would prevent the district

courts from fashioning remedies appropriate to the par

ticular circumstances of each case. The very complexity

of the possible legal situations accentuates the need for

guidance from this Court.

I.

The Decision of the Court of Appeals That Section

7 0 3 (h ) of Title VII Limits the Remedies Provided by

Section 1981 Is Inconsistent With the Decision of This

Court in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.

The allegations of plaintiffs’ complaint, and the facts

found by the District Court, clearly established a violation

of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and mandated an award of back pay

as well as an injunction requiring the company to hire

both Waters and Samuels with retroactive seniority.

Section 1981, which forbids racial discrimination in the

making of contracts, includes within its prohibition any

racial discrimination in employment.12 Waters first sought

11 Wisconsin Steel had three sets of seniority rules: a written

agreement with Local 21, an unwritten policy regarding laid-off

employees whose recall rights had expired, and a special ad hoc

rule for eight white employees who had waived their recall rights

in return for severance pay. Plaintiff Waters was rejected for

employment by Wisconsin Steel because of his race in 1957, before

the adoption of Title VII. Plaintiff Samuels had not applied for

employment with Wisconsin Steel until April, 1966 when he ap

plied and was rejected because the company gave preference to

former employees.

12 The availability of 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 as an alternative

jurisdictional basis for employment discrimination litigation free

of the procedures incorporated in Title V II has been unanimously

recognized by the Circuits. Hackett v. McGuire Brothers, Inc.,

445 F.2d 442 (3rd Cir. 1971) ; Brown v. Gaston Dyeing Machine

12

a job at Wisconsin Steel during the fall of 1957. Had be

been white he would have been hired at that time, would

have been laid off only infrequently in the following years,

and would by now have accumulated 18 years of seniority.

Instead, Waters was not hired until 1964, actually worked

at Wisconsin Steel for less than three months; Waters

was then not recalled until March, 1967, when he was once

again laid off within three months. The Company’s refusal

to accord Waters the seniority to which he was entitled,

in conjunction with its seniority system for layoffs and

recalls, has clearly perpetuated the effects of its past

discrimination. Similarly, when Samuels applied to Wis

consin Steel in 1966, he was rejected, not because he had

less skill or less experience, but because he had not worked

at Wisconsin Steel before, and the former employees hired

instead were, because of the company’s previous policy of

discrimination, all white. As to Samuels as well, the com

pany’s seniority system served to continue into the future

the effects of discrimination of years past.

The Court of Appeals did not deny that the facts found

by the District Court would, prior to 1964, have established

a violation of § 1981 and entitled plaintiffs to the relief

they sought. The Court held, rather, that to the extent that

section 1981 afforded plaintiffs any remedy, it had been

repealed by Title YII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The

Seventh Circuit concluded that the company’s practices

did not violate Title V II because of a loophole for certain

seniority provisions contained in section 703(h), and then

summarily rejected plaintiffs’ section 1981 claim with the

Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 409 U.S. 982

(1972) ; Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d 641 (5th

Cir. 1974); Long v. Ford Motor Company, 496 F.2d 500 (6th

Cir. 1974) ; Brady v. Bristol-Myers Co., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir.

1972) ; Macklin v. Spector Motor Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d

979 (D.C. 1973).

13

words “having passed scrutiny under the substantive re

quirements of Title VII, the employment seniority system

utilized by Wisconsin Steel is not violative of 42 U.S.C.

Section 1981.” (16a n.4). The Seventh Circuit apparently

concluded that if a disputed employment practice was not

forbidden under Title V II it was ipso facto legal under all

other statutes prohibiting discrimination, and that any pre

existing remedy for such discrimination broader than Title

V II had been tacitly repealed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

This summary rejection of plaintiffs’ section 1981 claim

is squarely in conflict with this Court’s decision in

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974). In

Alexander this Court rejected the contention that ag

grieved employees were limited to any single remedial

provision.

• • • (L)egislative enactments in this area have long

evinced a general intent to accord parallel or over

lapping remedies against discrimination7 . . . (T)he

legislative history of Title V II manifests a congres

sional intent to allow an individual to pursue inde

pendently his rights under both Title VII and other

applicable state and federal statutes. The clear infer

ence is that Title VII was designed to supplement,

rather than supplant, existing laws and institutions

relating to employment discrimination.

7 See, e.g. 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 (Civil Rights Act of

1966); 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 (Civil Rights Act of 1871).

id. at 47-49; see also Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 545-

549 (1974).13 It is the very essence of “ overlapping

remedies” that discrimination not covered by one remedy 13

13 Cf. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., O T 1974

No. 73-1543. ’

14

may be forbidden by another. This Court has repeatedly

rejected the argument that other sections of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 or the Civil Rights Act of 1968 limit

or repeal, substantively or procedurally, the provisions

of the earlier Civil Rights Acts. Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S.

409, 416 n. 20 (1968); Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U.S. 229, 405 (1969); Swann v. Ckarlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 17 (1971).

That section 703(h) could have limited section 1981 is

inconsistent with the established principle that repeals by

implication are not favored. Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S.

535, 549-550 (1974); United States v. Borden Co., 308 U.S.

188, 198 (1939). In the area of employment discrimination

the intention of Congress not to repeal or limit pre-existing

or parallel remedies is “ clear and manifest” .14 In both

1964 and 1972 Congress expressly rejected proposals to

make Title VII the exclusive remedy for employment

discrimination.15

Other circuits have, consistent with Alexander, uniformly

rejected attempts to impose on other remedies the limita

tions applicable to Title VII. See e.g., Contractors Associa

tion of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor, 442

F.2d 159, 172 (3rd Cir. 1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 859

(1971) (Section 703(j ) of Title VII could not limit the

remedial scope of Executive Order 11246); Guerra v. Man

chester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d 641, 653-4 (5th Cir. 1974)

(Title V II’s failure to prohibit discrimination in favor of

citizens does not limit the protection afforded aliens by

section 1981); Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America,

369 F. Supp. 1221, 1230-31 (E.D. La. 1974).

14 United Packinghouse, etc. Union v. N.L.B.B., 416 F.2d 1126,

1133, n . l l (D.C. Cir. 1969), cert, denied 396 U.S. 903 (1969).

15 See 110 Cong. Rec. 13650-13652 (1964); Alexander v. Gard-

ner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 48, n.9.

15

The Seventh Circuit’s decision imposing on section 1981

the limitations which it believed to exist under Title VII is

precisely the approach Congress rejected when it refused

to make Title VII the exclusive remedy for racial dis

crimination in employment, and warrants summary

reversal in the light of Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.

II.

The Decision of the Court of Appeals That Section

7 0 3 (h ) Protects Seniority Systems Which Perpetuate

the Effects of Past Discrimination Is In Conflict With

the Decisions of Other Circuits.

The District Court awarded both plaintiffs injunctive

and monetary relief under Title VII because defendants’

seniority system had operated to perpetuate the effects of

past discrimination. The Court of Appeals did not deny

that the company had discriminated in the past, or that the

seniority system had the effect of continuing the discrim

inatory impact of that prior misconduct. The Seventh Cir

cuit overturned the awarded relief solely on the ground

that section 703(h) placed this discriminatory impact out

side the scope of Title V II’s prohibition or remedies.

Section 703(h) provides

[I] t shall not be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to apply . . . different terms and condi

tions, or privileges of employment pursuant to a bona

fide seniority . . . system . . . provided that such differ

ences are not the result of an intention to discriminate

because of race.

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h). The Court of Appeals read 703(h)

as establishing a per se rule that any contractual seniority

16

system, and as to new applicants any informal or ad hoc

seniority rule,16 is excluded from the reach of Title VII

regardless of whether it has a discriminatory impact.

The decision of the Seventh Circuit is the latest develop

ment in a controversy now dividing, and confounding, the

lower courts as to whether section 703(h) protects a senior

ity system even if the system perpetuates the effects of

past discrimination and, solely because of their race, gives

preferential treatment to whites in layoffs and recalls. That

controversy appears in the guise of one of three questions

— (1) Can such a seniority system he used to determine the

order of layoffs and recalls! (2) Can minority workers

who were or would have been denied employment in the

past be given “ retroactive” seniority to overcome the dis

criminatory impact of such a system! (3) Is a system with

such an impact bona fidef In most cases these questions

as a practical matter yield identical answers as to the

impact of section 703(h); it is a measure of the confusion

wrought by this problem that the answers to these different

questions within a single circuit have not always been

consistent.17

16 In addition to the contractual seniority agreement between

Wisconsin Steel and Local 21, the company adopted a special

ad hoc rule granting a hiring preference to eight white former

employees who had waived recall rights in return for severance

pay. The Seventh Circuit held that as to a former employee like

I\aters, this ad hoc rule was an illegal act of discrimination but

that, as to a new applicant like Samuels, the rule was a bona fide

seniority system outside the reach of Title V II. The logic of this

distinction is not irresistible.

17 Thus the position advocated by petitioners might be stated to

be (1) that the seniority system was covered by section 703(h),

but coverage does not protect the system when it has such an

impact, (2 ) that 703(h) did not bar giving minority employees

sufficient seniority to overcome any discriminatory effect, or (3)

that the system was not covered by section 703(h), according to

which question is asked.

17

In the instant case the Seventh Circuit cast the issue in

the form of the first question and concluded that section

703(h) protects the use of seniority in hiring and layoffs

regardless of its discriminatory impact. The same posi

tion has been taken by the Third Circuit in Jersey Central

Power & Light Co. v. Electrical Workers, Local 327 , --------

F. 2d ------ , 9 FEP cases 117 (3d Cir. 1975). The Third

Circuit ruled that a labor agreement which provided for

the use of company seniority to determine layoffs and re

calls would have to he adhered to even though it might

continue the effects of past race and sex discrimination

and even though it might negate the affirmative steps which

had been taken to eradicate the effects of discrimination

pursuant to an agreement that had been entered into by

the company, union, and the EEOC. Id. at 130-32.

The contrary position was taken by the Sixth Circuit in

Meadows v. Ford Motor Company,------ F .2 d ------- , 9 EPD

H 9907, pp. 6771-72 (6th Cir. 1975). In that case the de

fendant company had refused to hire women because of

their sex. The Sixth Circuit held that, in order to afford

relief to the victims of discrimination, the plant seniority

system governing layoffs and recalls would have to be

changed since that system violated Title V II by continuing

the effects of past discrimination.18 Similarly, in Watkins

v. United Steel Workers, 369 P.Supp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1974)

the court prohibited the use of seniority in determining

which employees would be laid off and recalled. The dis

trict court held that it was a clear violation of Title VII

to make employment decisions on the length of service,

18 The Sixth Circuit in Meadows remanded the case back to the

district court for a consideration of balancing the equitable factors

concerning the victims of the hiring discrimination with the in

terests of the incumbents. The Sixth Circuit stated that recon

ciliation of these competing interests would be difficult, but not

impossible. This is the traditional function of a district court in

equity; however, it is exactly what the broad prohibition of Waters

would prohibit.

18

where blacks had been, by virtue of prior discrimination,

prevented from accumulating seniority. 369 F.Supp. at

1226-27.

Although unions may technically be “ employers” under

Title VII, and thus hiring hall preferences for union mem

bers of long standing are seniority systems, the Eighth

Circuit has forbidden the use of such seniority in giving

preferences in hiring hall referrals. United States v. Sheet

Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123, 131, 133-34 n.20

(8th Cir. 1969), rev’ing 280 F.Supp. 719, 728-730 (E.D. Mo.

1969).19 Similarly, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Circuits have

forbidden the use of seniority as a factor in promotions

in cases where the employer had in the past discriminated

in hiring on account of race.20

The dispute regarding the use of retroactive seniority to

overcome the discriminatory effect of seniority systems has

also divided the circuits. In Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 495 F.2d 398, 414 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

43 LW 3330 (1974)21 the Fifth Circuit held such relief was

precluded by section 703(h):

19 See also Bobbins v. Electrical Workers Local 212, 292 F.Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968), aff’d as later modified, 472 F.2d 634 (6th

Cir. 1973) ; EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189, 311 F.Supp.

468, 474-476 (S.D. Ohio 1970), vac’d on other grounds 438 F.2d

408 (6th Cir. 1971, cert, denied, 404 U.S. 832 (1971).

20 Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 358 (5th Cir.

1972) ; Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F.Supp. 1134, 1142-1143 (S.D.

Ala. 1971), aff’d per curiam 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972), cert,

denied 412 U.S. 909 (1973) ; Afro-American Patrolmen’s League

v. Buck, 366 F.Supp. 1095, 1102 (N.D. Ohio 1973), aff’d in perti

nent part 503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974); Harper v. Mayor and

City Council of Baltimore, 359 F.Supp. 1187, 1203-1204 (D. Md.

1973) , aff’d sub nom Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir.

1973) ; Loy v. City of Cleveland, 8 FE P Cases 614 (N.D. Ohio

1974) ; see also Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of Civil

Service Com’n, 497 F.2d 1113, 1115 (2nd Cir. 1974).

21 A second petition for certiorari which presents the question

of whether district courts have the authority to award retroactive

seniority as a remedy for hiring discrimination is pending. Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Company, No. 74-728.

19

. . . We do not believe that Title VII permits the exten

sion of constrnctive seniority to them [the black vic

tims of discrimination] as a remedy, section 703(h).

. . . The discrimination which has taken place in a

refusal to hire does not affect the bona, fides of the

seniority system.

In Jurinko v. Edwin L. Wiegand Co., 477 F.2d 1038, vacated

and remanded on other grounds, 414 U.S. 970, reinstated

497 F.2d 403 (3rd Cir. 1974), the Third Circuit reached the

opposite conclusion:

We can perceive no basis for the trial court to have

refused to award back seniority or for its conclusion

that “the plaintiffs are to be offered employment in

production with the company, of course, as new em

ployees” . Seniority is, of course, of great importance

to production workers for it determines both oppor

tunities for job advancement and the order of layoff

in the case of a reduction in a company’s operating

forces. It is our view that the plaintiffs are entitled

to seniority and back pay dating from the time of the

discriminatory employment practice up to the time

they are actually reinstated. Only in this way will the

present effects of the past discrimination be eliminated.

477 F.2d at 1046. The Sixth and Eighth Circuits have also

sanctioned the award of retroactive seniority. Meadows v.

Ford Motor Company,------ F .2 d ------ , 9 EPD H9907 (6th

Cir. 1975). United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36,

416 F.2d 123, 131, 133-34, n.20 (8th Cir. 1969).22

22 Several district courts have also specifically held that Title

V II permits the district courts to provide retroactive seniority

or some other relief for discrimination which results from a last

hired, first fired seniority system. Watkins v. United Steelworkers

of America, Local 2369, 369 F.Supp. 1221 (D.C. La. 1974); Delay

20

Similar conflict exists as to whether a seniority system

with a discriminatory impact is “ bona fide” within the

meaning of section 703(h). Jersey Central Power & Light

Co. v. Electrical Workers, Local 327 concluded that such

a system could qualify as bona fide and thus falls under the

protection of §703 (h).

“We thus conclude in light of the legislative history

that on balance a facially neutral company-wide se

niority system, without more, is a bona fide seniority

system and will he sustained even though it may oper

ate to the disadvantage of females and minority groups

as a result of past employment practices” .

9 FEP Cases at 131. In Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc.,

279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1969), however, the court

reached the opposite conclusion:

Obviously one characteristic of a bona fide seniority

system must he lack of discrimination. Nothing in

§703 (h), or in its legislative history, suggests that a

racially discriminatory system established before the

Act is a bona fide seniority system under the Act.

279 F.Supp. at 517.* 23 See also Local 1 8 9 , United Paper-

makers and Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980,

v. Carling Brewing Company, 9 EPD T19877 (N.D. Ga. 1974) ; see

Chance v. Board of Examiners, No. 70 Civ. 4141 (S.D.N.Y. Feb.

7, 1975). See cases cited in Fn.9, supra, and Cooper and Sobol,

Seniority and Testing Under Fair Employment Laws: A General

Approach to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv.

L.Rev. 1589, 1629 (1969) (hereinafter cited as Cooper and Sobol).

23 In these cases the courts have required the substitution of

date-of-hire ( “ Company” or “ plant” ) seniority for unit seniority

to allow black employees equal access to jobs in formerly all-white

units. These decisions adopt employment date as a nondiscrimina-

21

995-97 (5th Cir. 1969) cert, denied 397 U.S. 919

(1970).24

tory seniority standard not because it is per se valid but because

it accomplishes the remedial purpose of Title VII. The instant

case requires a different remedy under the same principles be

cause of a crucial factual difference— the existence of an all-white

work-force. See also, United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446

F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971) ; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ; United

States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied 411 U.S. 939 (1973) ; United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S.

906 (1972) ; Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973) ; United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973).

24 The decision of the Court of Appeals conflicts with labor law

decisions of this Court which establish appropriate relief under

Section 10(c) of the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C.

§160(c ). The conflict is particularly significant because section

10(c) served as the model for Section 706(g), the remedial pro

vision of Title V II. United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906, 921 n.19 (5th Cir. 1973) • Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co., 494 F.2d 211, 252 (5th Cir. 1974).

In NLRA cases this Court has consistently held that a victim

of an unlawful employment practice must be placed in the posi

tion he would have occupied but for the discriminatory practice,

NLRB v. Rutter-Rcx Mfg. Co., 396 U.S. 258, 263 (1969). A rem

edy that leaves him “worse off” is inadequate, id; Golden State

Bottling Co. v. NLRB, 38 L.Ed.2d 388 (1973), aff’g 467 F.2d 164,

166 (9th Cir. 1972). Accordingly, reinstatement to full status,

including all seniority benefits, is necessary relief for an employee

subjected to an unfair labor practice, including unlawfully rejected

job applicants. Victims of unlawful hiring discrimination should

therefore be reinstated on the same basis as those unlawfully dis

charged. Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177, 188 (1941);

Southport Co. v. NLRB, 315 U.S. 100, 196 n.4 (1942) ; NLRB v.

Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., 304 U.S. 333, 341, 348 (1938).

See e.g., Atlantic Maintenance Co. v. NLRB, 305 F.2d 604 (3rd

Cir. 1962), enf’g 134 NLRB 1328 (1961) ; NLRB v. Lamar Cream

ery Co., 246 F.2d 3, 10 (5th Cir. 1957), enf’g 115 NLRB 1113

(1956); NLRB v. Cone Brothers Co7itracting Co., 317 F.2d 3, 7

(5th Cir. 1963).

22

Wisconsin Steel rejected Samuels’ application solely25

because it decided to rehire former white employees who

had no contractual rights to recall and who had been hired

during a period when the Company only hired white brick

layers. The Seventh Circuit rejected Samuels’ claim that

this preference for former employees was unlawful with

the following blanket statement:

We do not doubt that a policy favoring recall of a

former employee with experience even though white

before considering a new black applicant without ex

perience comports with the requirements of Title V II

and Section 1981.

(16a).26 The Ninth Circuit took a contrary position in

Gates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., 492 F.2d 292 (1974). In

that case, the defendant, in hiring for an accountant’s job,

gave a preference to present company employees. Since

the firm had few, if any, eligible black employees, the pref

erence had the effect of discriminating on the basis of race.

The Ninth Circuit enjoined the use of such a preference

reasoning that the policy “ as applied” in the context of a

past practice of excluding blacks was in violation of Title

VII,27 id. at 296. When an employer with a history of

racially discriminatory hiring practices gives preference

to its former employees, it does more than create a “built-

25 A t the time Samuels applied for work at Wisconsin Steel in

April, 1966, he was an experienced bricklayer.

26 The Seventh Circuit, while not expressly so stating, consid

ered, in all likelihood, the informal or ad hoc recall of former

white employees who had no contractual rights, as not a violation

of Title V II because of its interpretation of Section 703(h).

27 The Ninth Circuit, unlike the Seventh Circuit, properly

analyzed the business reasons for the promotion-from-within policy

in light of the “business necessity” test. Gates v. Georgia Pacific

Corp., supra at 296.

23

in headwind” to the equal employment opportunities of

black applicants, see Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra at

432; it erects an insurmountable barrier to employment

to those previously excluded on the basis of race.28

The limitation that the Seventh Circuit imposed on

Title V II is inconsistent with the breadth of remedy con

templated by other provisions of that statute. Section

703(a)(2) defines as an unlawful employment practice any

practice which would merely “ tend to” deprive individuals

of equal employment opportunities or adversely affect them

because of race. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). This Court, noting

the broad sweep of this section, explained in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1970):

Under the Act, practices, procedures or tests neutral

on their face, and even neutral in terms of intent,

cannot be maintained if they operate to “ freeze” the

status quo of prior discriminatory employment prac

tices.

Similarly, Section 706(g) grants broad powers to the fed

eral courts to remedy any discrimination they find. 42

U.S.C. §2000e-5(g). In 1972, the Conference Committee

Report explained that Section 706(g)

28 The legislative history of Title V II supports the position of

* the Ninth Circuit. The passage of the Clark-Case Memorandum

dealing with recall preferences states:

. . . . "Where waiting lists for employment or training are,

prior to the effective date of the Title, maintained on a dis

criminatory basis, the use of such lists after the Title takes

effect may be held an unlawful subterfuge to accomplish

discrimination.

110 Cong. Ree. 6992 (April 8, 1964) ; see United States v. Sheet

Metal Workers, supra at 133-34, n.20. The recall on the basis of

length of service of former employees who have no contractual

rights to recall is just such a “waiting list(s) for employment,”

24

requires that persons aggrieved by the consequences

and effects of the unlawful employment practices be,

so far as possible, restored to a position where they

would have been were it not for the unlawful discrim

ination.

118 Cong. Rec. 3462 (daily ed., March 6, 1972).29 The con

struction of Section 703(h) suggested by Gates, Meadows,

Sheet Metal Workers, and Jurinko limiting that provision

to seniority systems which do not have a discriminatory

effect is more consistent with the broadly remedial pur

pose of Title V II and avoids any conflict between that

provision and Sections 703(a)(2) and 706(g).

The Seventh Circuit’s reading of the legislative history

of Title V II is clearly erroneous. The Seventh Circuit did

not deny that, but for section 703(h), Wisconsin Steel’s

seniority system would have violated Title VII. When Title

VII was reported out by the House Judiciary Committee

on November 20, 1963, it contained no such provision

regarding seniority. Conservatives on the Committee criti

cized the bill on the ground that it would require a revision

of seniority practices by employers who had discriminated

on the basis of race.30 The same objection to Title VII

29 See also United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965);

Griggs v. Duke Power Go., supra at 429-430 (1971) ; Vogler v.

McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236, 1238 (5th Cir. 1971) ; Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 243 (5th Cir. 1974);

Bock v. Norfolk & Western Bwy. Co., 473 F.2d 1344 (4th Cir.

1973), cert, denied 412 U.S. 933 (1973). Cf. Corning Glass Works

v. Brennan, 41 L.Ed.2d 1 (1974).

30 “ I f the proposed legislation is enacted, the President of the

United States and his appointees— particularly the Attorney Gen

eral— would be granted the power to seriously impair . . . the

seniority rights of employees in corporate and other employment

[and] the seniority rights of labor union members within their

locals and in their apprenticeship program. . . .

“ The provisions of this act grant the power to destroy union

seniority . . . . with the full statutory powers granted by this

25

was voiced on the floor of the House,31 and proponents of

the bill did not deny this would be its effect. Congress

man Dowdy proposed an amendment to exempt completely

from coverage by Title VII any employment decision based

on a seniority system;32 the House rejected the amend

ment.33 The House on February 4, 1964 adopted Title VII

without any special language regarding seniority.34

The original Senate bill, reported out of the Commerce

Committee on February 10, 1964, was similar to the House

bill, and contained no provision similar to section 703(h).

The initial Senate bill was also criticized on the ground

that it would affect seniority rights. In response to this

criticism Senator Clark, on a single occasion on April 8,

1968, before a nearly empty chamber, placed into the record

the documents relied on by the Seventh Circuit suggesting

that Title VII would have no effect whatever on seniority

rights.35 By the Seventh Circuit’s own reasoning the Clark

materials were erroneous, for, on April 8, the proposed civil

rights bill did not contain section 703(h) or any comparable

provision. On May 26, 1964, the Senate leadership offered

a new civil rights bill of their own, containing §703(h). The

language of this new provision, which bore no resemblance

bill, the extent of actions which would he taken to destroy the

seniority system is unknown and unknowable” . H. Rep. No. 914,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 64-66, 71-72.

31110 Cong. Rec. 2726 (1964) (Remarks of Rep. Dowdy).

32 The proposed amendment provided “ [t]he provisions of this

title shall not be applicable to any employer whose hiring and

employment practices are pursuant to (1) a seniority system

. . . . ” 110 Cong. Rec. 2727 (1964).

33110 Cong. Rec. 2728 (1964).

34110 Cong. Rec. 2804 (1964).

35 See 110 Cong. Rec. 7207 et seq. (1964). The Clark construc

tion also appears mistaken in the light of the bill’s history in the

House.

26

to the rejected Dowdy amendment, was explained by Sen

ator Humphrey, one of the sponsors of the leadership bill :36

[T]his provision makes clear that it is only discrim

ination on account of race, color, religion, sex or na

tional origin that is forbidden by the title. The change

does not narrow application of the Title, but merely

clarifies its present intent and effect.

Neither Senator Clark, Senator Case, nor the Department

of Justice ever offered any construction of or comment on

section 703(h), which was adopted along with the rest

of the leadership bill on June 19, 1964.37 Congressman

Celler, in explaining to the House the changes contained

in the Senate bill, noted the provisions in section 703(h)

regarding job-related testing but, apparently agreeing with

Senator Humphrey’s construction, did not mention the se

niority language.38 Under these circumstances the deci

sion of the Seventh Circuit, construing section 703(h) on

the basis of comments made by Senator Clark weeks be

fore that section was ever written or proposed, was clearly

mistaken.

36110 Cong. Rec. 12,723 (1964).

37110 Cong. Rec. 14,511 (1964).

38110 Cong. Rec. 15896 (1964). Celler did mention such in

significant changes as those regarding corporations owned by

Indian tribes and discrimination against atheists.

27

III.

The Decision of the Court of Appeals Limiting

Waters’ Right to Back Pay Is In Conflict With Deci

sions of the Third and Fourth Circuits.

The Seventh Circuit upheld the decision of the Dis

trict Court that Wisconsin Steel discriminated against

plaintiff Waters when on January 17, 1967 it gave recall

preference to a former white employee who had waived

his recall rights in return for back pay. Waters main

tained that he continued to suffer monetary loss from that

date until the present time and neither court below found

otherwise. The Court of Appeals, however, ruled that as

a matter of law Waters was only entitled to back pay

for the period prior to September 5, 1967, when Waters

declined an offer of employment at Wisconsin Steel.

Three critical facts, set out in the record, bear on the

legal significance of this offer. First, the Company in

sisted that as a condition of returning to work Waters

execute a waiver abandoning his then pending claim to

be restored to the seniority he would have had but for

the Company’s initial refusal to hire him because of his

race. Second, Waters was concerned that it would be

argued that he had waived some or all of his rights merely

by accepting the Company’s offer and he so advised the

Company in writing. The Company responded, not by as

suring him it would not so argue, but by insisting he

was entitled to neither back pay nor seniority.39 Third,

39 Waters wrote:

I believe that International Harvester Company, Wisconsin

Steel Division has discriminated against me because of my

race, and I believe that I would lose some of my rights,

privileges or immunities secured and protected by the Con

stitution and laws of the United States if I came back to

28

since Wisconsin Steel would accord him no seniority,

Waters had every reason to believe he would promptly

be laid off soon after starting work as he had been twice

before. To take snch a position and give np a more

secure job he had with another firm would have been

inconsistent with both common sense and Waters’ obliga

tion to mitigate his damages. The district court found

that Waters had declined the September, 1967 offer of

employment because it might prejudice his pending Title

VII claim.

The Court of Appeals held that despite these conditions

Waters had an absolute legal obligation to accept the job

offered by Wisconsin Steel and forfeited any right to fur

ther back pay when he declined to do so. The Seventh

Circuit’s decision is in direct conflict with the decision of

the Third Circuit in Jurinko v. Edwin L. Wiegand Com

pany, 477 F.2d 1038 (3rd Cir. 1973) and the en banc deci

sion of the Fourth Circuit in Williams v. Albemarle City

Board of Education, ------ F.2d ------ , 8 EPD f 9820 (4th

Cir. 1974). In Jurinko, the employer had refused in 1966

to hire the plaintiffs because of their sex, but in February,

1969 offered them jobs with neither back pay nor the se

niority to which they were entitled. The district court held

their refusal to accept the jobs ended plaintiffs’ right to

further back pay. The Third Circuit reversed, reasoning:

work before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

render their decision in this case.

I would like to know if Wisconsin Steel Works is prepared

to pay me my lost time and place me on the seniority list

in the position I should be in?

The Company responded:

We find that no monies are due you.

W e reject your request that you be placed on the seniority

list when, in fact, you have no accrued seniority, on the

ground that such action would be in direct violation of our

labor agreement.

29

The terms of the 1969 job oilers were within Wiegand’s

control, and it did not offer plaintiffs seniority or back

pay. The offer that was made did not rectify the effect

of its past discrimination, and the plaintiffs were under

no duty to accept such an offer.

477 F.2d at 1038. In Williams, the plaintiff had been re

moved from his job as a school principal because of his

race, but the defendants contended he had no right to back

pay because he had rejected its offer of employment as a

teacher. The Fourth Circuit rejected that contention and

held the principal had no obligation to accept a position

less than that to which he was entitled. 8 EPD at p. 6439.40

The decision of the Seventh Circuit on the facts of this

case sanctioned a deliberate and callous attempt by Wis

consin Steel to sabotage Waters’ pending claim by forcing

him to choose between waiving his claim for seniority and

back pay (if he accepted the job) and waiving any future

back pay (if he did not). Such a legal maneuver is not

consistent with the requirement that all waivers must be

voluntary, Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938), or with

the public policy against any waivers of rights involving

the public interest. Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O’Neil, 324

U.S. 697 (1945). I f such job offers can have the effect

claimed by the Court of Appeals, they will afford recal

citrant employers a ready means to prevent the enforce

ment of Title VII.

40“ [Tlhere can be little question that the alternative employ

ment was of a kind inferior to that previously followed by the

appellee . . . . More importantly, the acceptance of the alterna

tive employment in this case could well have been regarded as

an acquiescence by the appellee in his racially discriminatory de

motion.” Id.

30

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a Writ of Certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Seventh Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Judson H. M iner

Charles B arnhill , Jr.

Davis, Miner & Barnhill

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit III

B arry L. Goldstein

M orris J. B aller

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Petitioners

P hilip B. K urland

Rothschild, Barry & Myers

Two First National Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60670

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

intfie

Mmteh States; Court of

jFor tfje g>ebentfj Circuit

Nos. 73-1822, 73-1823, and 73-1824 '

W illiam A. W aters and D onald

Samuels,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W isconsin Steel W orks of I nter

national H arvester Company, a

corporation, and U nited Order

of A merican B ricklayers and

S tone M asons, L ocal 21, an un

incorporated association,

Defendants-Appellees.

U nited Order of A merican B rick-

LAYERS AND S T O N E MaSONS,

L ocal 21,

Defendant-Appellant,

v.

W illiam A. W aters and D onald

Samuels,

Plaintiff s-Appellees.

A p p e a l s from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Northern District

>- of Illinois, Eastern

Division.

No. 68 C 2483

W illiam J.

Campbell, Judge.

I nternational H arvester Com

pany,

Defendant-Appellant,

v.

W illiam A. W aters and Donald

Samuels,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

A rgued A pril 22, 1974 — Decided A ugust 26, 1974

Before Swygert, Chief Judge, H astings, Senior Circuit

Judge, and Sprecher, Circuit Judge.

la

2a

Swygert, Chief Judge. P la in tiffs W illiam A . W a ters

and D onald Sam uels, both black jou rn eym en brick layers,

appeal fro m a ju dgm ent o f the d istrict cou rt entered

a fter a bench tria l finding that the defendants had v io la ted

both T itle V I I o f the C ivil R igh ts A ct o f 1964, 42

IT.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and Section I o f the C ivil R ights

A c t o f 1866, 42 U .S.C . § 1981. T he p la in tiffs ’ appeals

cen ter so le ly on the d istrict co u rt ’s ap p roach to ca lcu

lating the p la in tiffs ’ back -pay aw ard and a ttorn eys ’ fees

under T itle V I I . D efendants International H arvester

C om pany (In tern ation a l), W iscon sin Steel W o rk s o f

International H arv ester C om pany (W iscon sin S tee l), and

L oca l 21, U nited O rder o f A m erican B rick layers and

S tone M asons (L oca l 21), cross-appea l fro m the d istrict

co u rt ’s finding that they v iola ted § 1981 and T itle V II .

In ternational operates a la rge steel p lant in Chicago,

know n as the W iscon sin Steel W ork s. I t em ploys a

sm all fo r c e o f brick layers to m aintain and rep a ir b last

furnaces. L oca l 21 is the exclusive barga in in g represen ta

tive fo r the brick layers em ployed b y International.

W a ters and Sam uels in itiated an action in the d istrict

cou rt on D ecem ber 27, 1968, cla im ing that certain em

p loym ent practices and p o lic ies o f In ternational and

jo in ed in b y L oca l 21 d ep rived them o f rights secured

b y : Section I o f the C ivil R igh ts A c t o f 1866, 42 U .S .C .

§ 1981; T itle V I I o f the C ivil R ig h ts A c t o f 1964, 42

U .S.C . ^ 2000 et seq.; the L a b o r M anagem ent R elations

A ct, 29 U .S .C . § 1 8 5 (a ) ; and the N ational L a b o r R e la

tions A ct, 29 U .S .C . § 151 et seq. B e fo re filing their

suit, p la in tiffs in M ay, 1966 had registered com plaints

w ith both the Illin o is F a ir E m ploym en t P ractices C om

m ission and the U nited States E qual E m ploym ent

O pportu n ity C om m ission (E E O C ) ch arg in g W iscon sin

Steel w ith racia l d iscrim ination due to W iscon sin S tee l’s

la y -o ff o f W a ters and its subsequent refu sa l to reh ire

him and its fa ilu re to h ire Sam uels. T h e S tate C om

m ission d ism issed the charges as u nsu bstan tiated ; likew ise

the E E O C concluded in a F ebru ary , 1967 decision that

no probab le cause existed to believe that W iscon sin Steel

had violated T itle V II . B u t as a result o f new evidence

that w hite brick layers had been h ired a fter W a ters sought

reinstatem ent and Sam uels had requested in itial em p loy

73-1822,73-1823,73-1824

3a

m ent, the E E O C reassum ed ju risd iction and, on recon

sideration , it determ ined that the p la in tiffs had cause to

sue.

S h ortly th erea fter the p la in tiffs in itiated their action

as a class action against both International and L oca l

21. On d efen d an ts ’ m otions, the d istrict court dism issed

p la in tiffs ’ claim s. On appeal w e reversed and rem anded

the cause fo r a trial. Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

427 F .2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U .S . 911

(1970). On rem and the p la in tiffs abandoned their class

allegations and p roceed ed to tria l on claim s o f ind ividual

d iscrim ination against the tw o p la in tiffs .

A t tr ia l W a ters challenged the existence o f W isconsin