Correspondence from Clerk to Counsel

Public Court Documents

January 24, 1972

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Correspondence from Clerk to Counsel, 1972. cc1b5180-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1861ab4e-dbdd-4a86-abd3-f65167da0078/correspondence-from-clerk-to-counsel. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

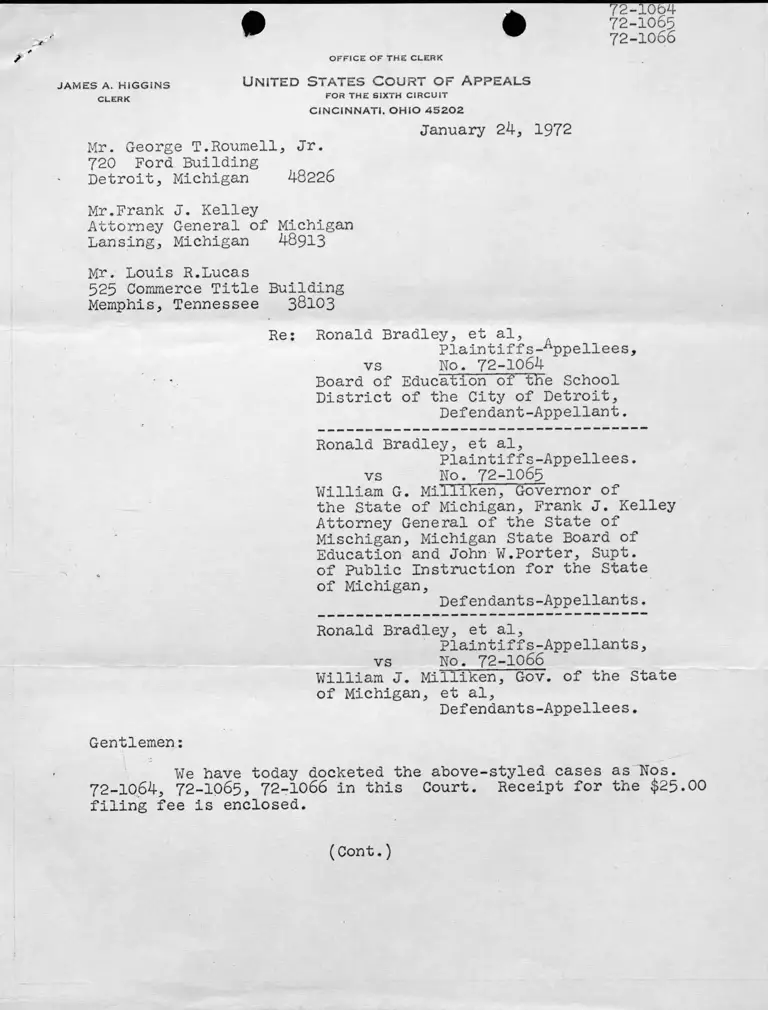

O FFICE OF THE CLERK

72-1064

72-106572-1066

JAMES A. HIGGINS

CLERK

United states Court of A ppeals

FOR THE SIXTH C IR C U IT

CINCINNATI. OHIO 45202

January 24, 1972

Mr. George T.Roumell, Jr.

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Mr.Frank J. Kelley

Attorney General of Michigan

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Mr. Louis R.Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Re: Ronald Bradley, et al,

Plaintiffs- ppellees,

vs No. 72-1064

• Board of Education of the School

District of the City of Detroit,

Defendant-Appellant.

Ronald Bradley, et al,Plaintiffs-Appellees.

vs No. 72-1065

William G. Milliken, Governor of

the State of Michigan, Frank J. Kelley

Attorney General of the State of

Mischigan, Michigan State Board of

Education and John W.Porter, Supt.

of Public Instruction for the State

of Michigan, Defendants-Appellants.

Ronald Bradley, et al,Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs No. 72-1066

William J. Milliken, Gov. of the State

of Michigan, et al,

Defendants-Appellees.

Gentlemen:

We have today docketed the above-styled cases as Nos.

72-1064, 72-1065, 72-1066 in this Court. Receipt for the $25.00

filing fee is enclosed.

(Cont.)

72-1064

72-106572-1066

Please Take note of the enclosed Notice Concerning

Sixth Circuit Policy.

Please sign and return the enclosed entry of appear

ance.

Very truly yours,

JAMES A. HIGGINS, CL?RK

C-

Richard Scrugham, Deputy

cc:

Mr. William E.Caldwell, 525 Commerce Title Bldg., Memphis,Tenn.

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones, General Cousel, N.A.A.C.P. 1790 Broadway

New York, New Y rk 10019

Mr. E. Winther Mc'Croom, 3245 Woodburn Avenue, Cinti, Ohio

Mr. Jack Greenberg, Mr. Norman J.Chachkin, 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

Mr. J. Harold Flannery, Mr. Paul R. Dimond, Mr. Robert Pressman

Center For Law & Education, Cambridge, Mass. 02138