Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1972

40 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1972. 0f003ba0-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/186ceb2c-9f3e-4ebb-8789-3be48360d078/reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

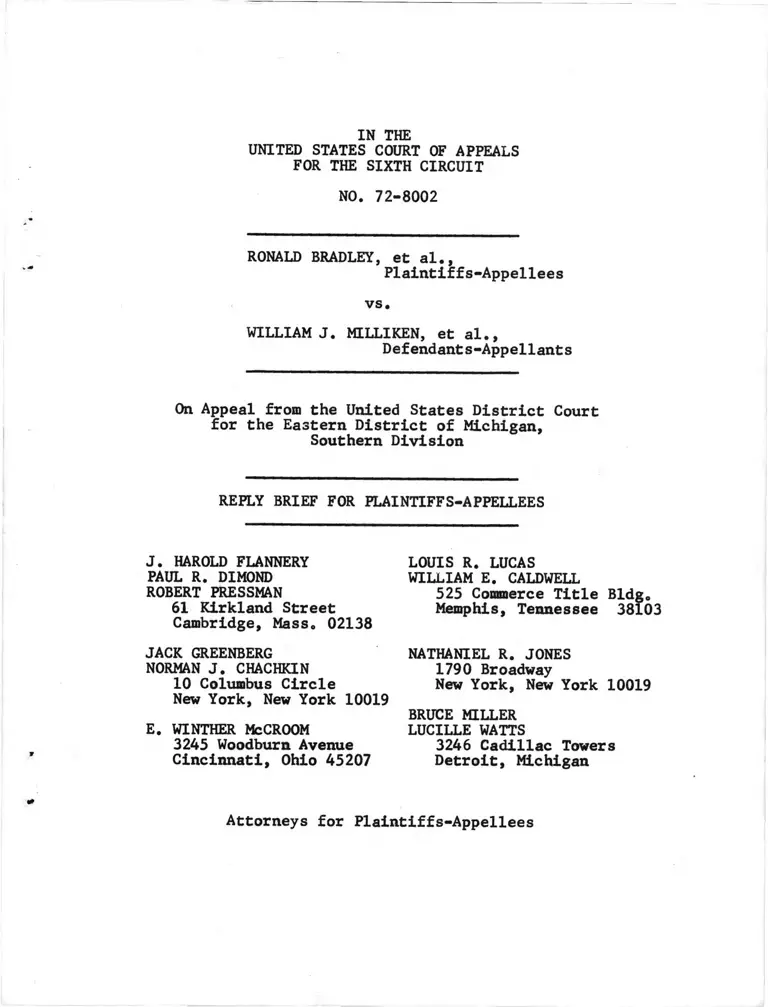

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-8002

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

vs.

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan,

Southern Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

ROBERT PRESSMAN

61 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

BRUCE MILLER

LUCILLE WATTS

3246 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-8002

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

vs*

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, et alo,

Defendants-Appellants

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan,

Southern Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

INTRODUCTION

This reply brief for plaintiffs-appellees is in two

parts along the lines of what we believe to be the material

issues genuinely presented for this Court's consideration.

Treated first and more extensively are the questions— whose

significance is one of the few matters of agreement among

the parties— grouped under the issue, the scope of the

violation and the remedy.

Thereafter we turn to the numerous lesser questions,

many of them raised in a scattershot, makeweight fashion

suggesting that even their exponents place limited cre

dence in them. In this category we address such matters

as the asserted necessity for a three-judge court, the

significance of intent and proximate cause in official

discrimination, Rule 41(b), and the school-by-school

approach to systematic segregation.

Fundamentally, however, the district court was correct

as to the nature and scope of the violation, after which

any lesser remedy would be constitutionally insufficient

and unsound.*

* Page references in this Brief to State's Brief

and the Allen Park intervenors* (Intervenor School Dis

tricts') Brief are to the substituted printed copies of

those briefs.

2

I. The Scope of the Violation and the Remedy

The Court below held that state educational policies

and practices contributed to the constitutional violation

found. It then proceeded to fashion a remedy which would

practicably provide Detroit children with "just schools,"

in place of schools which are a racially identified com

ponent of the relevant area.

The other parties have concentrated on this aspect

here, with the suburban and state defendants challenging

it in almost every particular; and we have previously

acknowledged it to be "the central question on appeal"

(Brief, p. 110, note 75)."" Even the United States, which

was authorized by this Court’s Order of July 20, 1972, to

"intervene for argument on the question of the constitu

tionality of Section 803," sua sponte devotes almost half

of its 42-page Brief to gratuitous observations on these

issues.

In the main, the suburban and state defendants' metro

politan arguments tend, in our judgment, to focus upon the

1/ To be sure, contentions concerning the Detroit vio

lations have been advanced. However, we have elected to

treat those secondarily for several reasons. First, anumber

of them, such as the significance of intent and causation in

school cases, are familiar and not difficult questions of

law (Detroit Board Brief, pp. 22, 33); secondly, others,

such as the pervasiveness and lasting effects of proven prac

tices, are traditionally matters for trial court determination

(State Brief, 72-75, 76-77); and lastly, a number of parties

to the appeal have effectively accepted the court s findings,

some explicitly (defendants-intervenors Magdowski, et al„,

Brief, p. 3), others arguendo (defendants-intervenors-appel-

(cont’d on next page)

-3-

general aspects of such questions as the remedial autho

rity of federal courts and the de facto autonomy of local

districts, and to gloss over the district court’s pain

staking and voluminous findings as to those very issues—

in the context of the violation detailed in this case.

Thus the suburban intervenors argue that the remedial

powers of federal courts are limited, that Brown and its

progeny are racial exclusion not identifiability cases,

that Michigan law does not sanction dual systems, that

only Detroit failed to maintain a unitary system, and that

the court strove for racial balance without inquiring into

the legality of suburban systems’ conduct. (Green Brief,

p. 8; Allen Park Brief, pp. 20-21, 28-29, 31-32, 4, 7, 14-15 )<>

The state defendants argue that they have not discrimi

nated personally, that the Legislature has imparted the

relevant powers to local districts aot the state board, and

that federal courts have declined to hear or grant relief

in cases challenging inequitable transportation arrangements

and taxing and spending formulae. (State Brief, pp. 34 et seq.,

42, 14, 16, 22, 24-25, 59-69).

Issues such as whether suburban districts may legiti

mately be affected by relief absent a showing that they have

discriminated independently or that their lines are created

1/ (cont'd)” lants Green, et al., Brief, pp. 2,8), and still others

who did not review the record (defendants-intervenors-appel-

lants Allen Park Public Schools, et alo, Brief, p. 50)„

-4

or maintained for racial reasons (Allen Park Brief, pp.

4, 14-15, 34) are not abstractions here; their resolution

is inseparable from the actual circumstances affecting

constitutional rights. Similarly, the case does not

challenge state policies, such as the transportation aid

formula, generally or as urban v. rural discrimination

(State Brief, pp. 59-69), but rather, as illustrating

educationally baseless practices which contributed, inevi

tably and foreseeably, to racially dual sets of schools.

Moreover, this appeal does not involve relief based upon

the district court's prediliction for racial balance or

other legislative-type consiaerations(Allen Park Brief, p0

33; State Brief, pc 83) but whether any district court

could have done otherwise where the only asserted justifi

cation for continuing the racial identity of Detroit's

schools is that the state and certain of its other units

would have it that way.

Therefore, let us review the relationship between the

violation and the remedy as contained in the record in this

J Jcase.

2/ We continue to adhere to our view that metropoli

tan desegregation would be required in this case purely as

a matter of remedy. That is, if Detroit children could not

be afforded "just schools" without inclusion of the suburbs,

then such inclusion would be mandated even if the unconsti

tutional condition were traceable solely to a particular state

agent— the Detroit Board. Regardless whether their policies

contributed to the violation, the states must, in the last

analysis, remedy constitutional defaults where their instru

mentalities will not or can not.It is also our view, however, that this case does not

present this question to this Court in its "pure" form. ̂

Rather, the district court found a preponderance of credible evidence that specific state policies and practices were causal

(cont'd on next page)

-5-

As a threshold matter it is undisputed that the

Detroit component of the state system is two-thirds black

while the tri-county components outside are more than 97

percent white; indeed, omitting from the computation such

traditionally black suburban pockets outside Detroit as

Inkster, River Rouge, and Ecorse discloses that the remain

ing components are more than 99 percent white. It is also

undisputed that a Detroit-only desegregation plan, "in

itself state action" (see United States v. Texas Education

Agency. F.2d (No. 71-2508, 5th Cir., decided

August 2, 1972, slip op. at 39)(cited hereinafter as Austin),

would perpetuate that inter-system racial identifiability.

Cf. Austin at pp. 37 and 49. Therefore, if there is a

causal relationship between state action and that effect,then

there is a violation; and cures which do not eliminate the

effects as well as the violation are inadequate.

We need only find a real and significant

relationship, in terms of cause and

effect, between state action and the

denial of equal educational opportunity

occasioned by the racial and ethnic sepa

ration of public school students.

* * * *

2/ (cont’d) . .— factors in the violation, and that such policies

either did not serve a compelling state interest or did not

do so in the most nondiscriminatory way reasonably available.

(A. Ia 515-516, la 525-526.) In this, among other respects,

our case differs from Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F.Supp. 1235

(D.N.Jo 1971).

3/ The defendants arguments, citing the recent Supreme

Court"~3’ecisions in Emporia and Scotland Neck, to the effect ̂

that the district court.here, by noting inter-district statis

(cont'd on next page)

-6-

Discriminatory motive and purpose,

while they may reinforce a finding

of effective segregation, are not

necessary ingredients of constitu

tional violations in the field of

public education.

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District,

F.2d (No. 71-2397, 5th Cir., decided August 2, 1972,

slip op. at 12-13, cited hereinafter as Cisneros).

What then were the relevant state actions and their

effects?

First, the court found, and it is undisputed, that the

state's pupil transportation reimbursement formula discrimi

nated against Detroit and in favor of suburban non-city dis

tricts, plus some suburban city districts by virtue of a

"grandfather clause". (A. IXa 630).

3/ (cont'd)tical disparities, was striving for racial balance

is to us a non sequitur. (State Brief, pp. 85-36, 88

Allen Park Brief, p. 33.) Those decisions, which curbed

efforts to create new, more identifiable systems, involved

districts already surrounded by counties whose school systems

also averaged more than 50 percent black. Bureau of the

Census, General Social Economic Characteristics (1970), Tables

119-120, 125.

4/ The state defendants seem to argue (State Brief,

p. 42“ et seq.) that this is an unconsented suit against _

the State, barred by the Eleventh Amendment, because plain

tiffs have not alleged specific discriminatory intent on

the part of named state officials. At least since Ex Parte

Young, 209 U0S„ 123 (1908), suing the officials in charge

has been the way to challenge state policy that is alleged

to be effectively discriminatory. Indeed, unless two of

these defendants are alleging that a third one is himself

singling out particular Michigan school districts for

discriminatory treatment, this is the pattern in their own

Serrano-type test case: Milliken and Kelley v„ Green, #53809,

Mich. Sup. Ct0

-7

The uncontroverted effects of this state policy were two:

Detroit's comparative inability to provide pupil transpor

tation induced the construction of more numerous,

smaller schools, which because of discriminatory housing

patterns were more segregated than fewer larger schools

would have been. (A.IIIa 93-95,223-24,IVa 129-30). In addition,

suburban schools were thus made more attractive to those

families desiring school transportation for their children—

at the very time when black families were excluded from

such districts by discriminatory housing practices. Compare

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S„

1, 20-21 (1971). (See Plaintiffs' Brief at 36-39).

We are not contending here that the transportation

discrimination, standing alon in a racially homogeneous

setting, is unconstitutional (see State Brief, pp. 74-75).

We are contending, however, that the inevitable and foresee

able effect of the state policy, for which no compensating

justification was advanced, was to make suburban schools more

attractive— and Detroit less attractive— in the context of

white mobility and black containment, Compare Cisneros,

above, at 14-15.

Second, it is not disputed that, as state policies

(such as the transportation formula and bonding authority

and equalization payments, discussed below) were causing

Detroit to be perceived as a disfavored school system, new

school construction was rampart in the suburbs while seats

-8-

were going begging in Detroit. (A. iVa 232-36, IXa 372).

During part of this period state defendants had direct

statutory control over new construction, and during all of

it they had residual constitutional responsibility for state

action at all levels. Again, because of discriminatory

housing patterns only white families could readily respond

to the lure of new schools in apparently favored districts.

Also again, the state defendants' arguments that they

did not personally effect residential segregation or dis

criminatory site selection and construction practices

(State Brief, pp. 34-40) is beside the point. See Cisneros,

above, at 15-18. The issue is not whether the state and

suburban defendants conspired with specific intent to

accomplish today's inter-district segregation. Nor are we

challenging abstractly an uneconomical state policy whose

only vice in a racially homogeneous setting might be its

extravagance. Rather, the gist of the constitutional vio

lation is that a state policy has effectively synchronized

with other racial discrimination to produce segregated

schools——wholly without independent justification for the

policy in terms of a compelling, or even plausible, state

interest. Compare NoA.A.C„P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S0 449

(1958); Brewer v. Norfolk School Board, 397 F.2d

37, 41-42 (4th Cir. 1968). See A. Ia 515-516.

-9

Third, it is undisputed that until 1971 Detroit's

authority to issue school construction bonds without a

popular vote was limited to 3 percent of the assessed

valuation of taxable property, while all other districts

could go to 5 percent. The state defendants argue (State

Brief, p. 60 et seq.) that the Supreme Court has sustained

other state school bonding provisions, and in this Court

for the first time, if we read their argument correctly

(Brief, p. 61), that the limitation was not actually dis

criminatory.

Be that as it may, this is not a geographic inequality

case. The point, again, is that made by the Supreme Couru

in Swann. Families gravitate toward schools, and by policies

that made Detroit an educational stepchild the state vir

tually insured that before long the system would be serving

primarily those families confined, within its perimeter by

residential racial restrictions.

This policy, like the others, was not supported below

by a showing of compelling state interest, and even here

we are told only that the inequity, if any, was eliminated

in May of 1971 (State Brief, pc 61)• In view of £he obliga

tion to eliminate discriminatory effects "root and branch,"

that remedy is too little and too late. Green v. New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430.

Fourth, a point similar to the foregoing ones was made

with respect to the effects of the state aid formula upon

-10

Detroit in comparison to the suburban districts. The state

defendants have responded (State Brief, p. 77 et.seq.), if

we read them correctly, that some suburban districts are

badly off and that federal courts do not entertain actions

framed in terms of pupils' "needs," citing Mclnnis vy

5/

Ogilvie, 394 UCS. 322 (1969).

We repeat that this case is not Serrano v0 Priest or

even Millikcn and Kelley v, Green0 Where state policies

operate without a compelling justification to stigmatize

some school districts as practically bankrupt or otherwise

undesirable, and where because of racial discrimination only

some families can move to districts commonly perceived to

be more favored, the state's contribution to inter-district

segregation is inevitable, foreseeable, and impermissible.

The "game board" is so "loaded" that a new one is required.

Swarm, 402 U.S. at 28.

The foregoing examples may not exhaust the roster of

state contributions to Detroit's inability to provide its

children with "just schools," and further inquiry might well

disclose others; but standing largely uncontroverted they

constitute substantial evidence in support of the trial

6/

court's findings.

5/ Contrary to this litigation position, the State Depart

ment of Education's Associate Superintendent for Business and

Finance, Robert McKerr, testified to the Senate Select Commit

tee on Equal Educational Opportunity, on October 26, 1971, to

the effect that Detroit compares unfavorably to its suburban

districts. Hearings, Part 19A, pp. 9466-67.6/ The state continues to take steps to preserve the segre

gation of the relevant schools. This Court will recall that it

voided, at an early stage of this case, a portion of Act 48

which purported to mandate neighborhood schools as a puprl

attendance criterion in Detroit. Bradley v0 Millikeji, 433 F.2d

897 at o Since the parties were last here, the State

School Aid Act of 1972 (PA 258, Reg. Sess. of 1972)

-11-

In summary as to the metropolitan violation, we note

that the suburban districts have argued (Allen Park Brief,

pp. 14-15, 34) that the correct standard as to violation

is whether district lines have been created, maintained or

operated in furtherance of an impermissible policy. Al

though not agreeing with this standard, we believe it has

been met. The state must justify policies underlying the

effects achieved here. It has justified neither the policies

nor the effects. Austin, above, at 50.

In the recent words of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit:

The explicit holding of Cisneros I,

which we now affirm, was that actions

and policies of the Board, had, in

terras of their actual effect, either ^

. created or maintained racial and ethnic

segregation in the public schools of

Corpus Christi.

Cisneros, above, at 13. The constitutional principle can

be no different where the state is a prime causer and the

district lines are the effects.

~ ^has^become law. It authorizes more than 34 million

dollars for pupil transportation and continues to discriminate

against Detroit as described above. Moreover, Section 79

^ ' No appropriations allocated under this act

for the purpose of covering transportation

costs or any portion thereof shall be used

for the payment of any cross busing tô

achieve a racial balance of students with

in a school district or districts. .

Compare Lee vc Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (D.N.Y. 1970),

affirmed, 4U2 \CTT935 (1971); North Carolina state Board

of Education v0 Swann, 402 U.SC 43,^5 ̂ X9717 Kelley.,v. ̂ ttetropoTitari 'County~¥d., Nos. 71-1778-79, slip op. at 30 (6th

Cir. May 30̂ I S I Q ) ,

12-

We understand the state and suburban arguments against

the district court's remedial framework of June 14, 1972, to

be essentially two: first, that Michigan's present legal

and administrative arrangements preclude such relief; and

secondly, that substantial cost and inconvenience will be

involved. This Court is urged, in effect, to be appalled

at the novelty and magnitude of the probable course of

events below.

It is tempting to answer that Brown v. Board of Educa

tion and Baker v. Carr were also quite disruptive of existing

arrangements, and that, in the recent words of the Austin

decision (slip. op. at 53): "Equal educational opportunity

must be provided despite cost and inconvenience."

We think it important that this Court be apprised of how

cautiously, indeed meticulously, the court below proceeded

in reaching its order of June 14. Any intimation that

the district court has unnecessarily distorted local arrange

ments in a heavyhanded, uninformed way is belied by the more

than one hundred findings of fact and conclusions of law,

and the precise order, of June 14. It is significant, we

believe, and supportive of our view, that the state and

suburban defendants have not, despite repeated opportunities,

sought to challenge or amend the particulars of the court s

framework. If we read their attitude correctly to be: "if

it must be done, that's the way to do it J that is in a

7/ Therefore, and because issues of state power and

constitutional rights we treated extensively in our Opening

Brief (pp. 81-107), we defer consideration of those.

-13-

sense to their credit, but it can not be reconciled with

generalized periodic naysaying.

It is asserted that the district court went beyond

ordering "just schools" for Detroit's children to require

racial balance, either for its own sake or in order to

foreclose future resegregation by "white flight." (Allen

Park Brief, p. 31; State Brief, p. 80, et seq.) Of course,

the Court did weigh such familiar concepts as "actual deseg

regation," but it is far too late in the constitutional

day to contend that such considerations are impermissible.

Swann, above, at 26-27. Moreover, the district court's

obligation is to choose that plan (itself a de jure act)

which promises unitary schools "now and hereafter". Green,

above. In that context, the court was able to avoid both

a resegregation plan and the Detroit Board's very expan

sive perimeter by the familiar expedient of controlling new

school construction. (A. Ia 515, 541.) That relief also

curbs continuation of one of the state's significant prior

violations. (A. Ia 516-517).

In any event, the best evidence that the district court

did not misuse these concepts is its rejection of plans that

weighted too heavily "racial ratio" and resegregation fac

tors. (Metro. Findings of Fact, 10, 14, and 19; A. Ia 501,

503, 504).

The appropriate area of pupil desegregation was consid

ered. The court viewed as its objective, not the fullest

-14-

possible use of its powers, but only that necessary to

achieve substantial actual desegregation of the Detroit

public schools. (A. la 499-500.) We shall not summarize

here the lengthy inquiry into practically every nook and

__8/

cranny of the many options presented. Some plans were re

jected because they did not desegregate pupils (A. la 501),

and others were premised upon legally problematical cri

teria (A. Ia 503). The court's findings speak eloquently

for themselves, but we believe that the court's criteria

for judgment may fairly be summarized to have been: sub

stantial desegregation, given such practicalities of the

situation as existing school district devices and arrange

ments, maximum sound use of existing facilities, times, dis

tances, and routes of bus trips, and the like. (A. la 506.)

Of course, it is difficult to know infallibly where the

many relevant factors converge ideally, but that is what

expert desegregation panels and continuing district court

jurisdiction are for. (A. Ia 517). And, as we have noted

8/ We refer here to the various metropolitan proposals.

The court had previously heard and ruled inadequate several

Detroit-only plans. In our view of state responsibility,

the court would have been authorized to require metropolitan

relief, without regard to the scope or participants in the

violation, upon a showing that Detroit alone is demogra-

phically unable to provide "just schools . The view of the

court seems to rely primarily upon the perhaps more con

servative analysis relating to the state1s role in the

violation and the complete absence of any practical or edu

cational basis for adopting so flawed a plan. (A. Ia 439-hAZ.)

It may have been in the alternative. (A. Ia 456-461.) In

any event, this Court reviews judgments not opinions.

-15-

previously, were the State and the suburban districts

to say, in effect, "we agree with the objective but we

have some different thoughts on how to get there (other

than neo-separation), no one would be more receptive than

the district court— except possibly plaintiffs.

The question of pupil transportation has arisen in

various forms in this casec We shall not repeat the dis

trict court's extensive findings here. (A. Ia 504-505,

510-512). This case does not involve turning a non

transportation system into a transportation system. Com

pare Cisneros, above, slip. op. at 25. Forty-two to

52 percent of the pupils in the suburban districts receiv

ing state reimbursement are now transported. That figure

contrasts with the Desegregation Panel's estimate that

ultimately about 37 percent of the pupils desegregated

will require transportation. That is not out of line with

the requirements of other cases in this and other circuits.

In the recent words of Judge Gewin in the Cisneros case

(slip. op. at 30):

I realize that the remedy as ordered

by the district court presents^serious

financial and administrative difficul

ties. It is a very substantial matter to

direct the bussing of one-third of

the district's students. But I do

not find it at all surprising that such

a remedy might be required in a system

where over two-thirds of the students

attend segregated schools.

In any event, the court's transportation findings, like

so many others, have been challenged in principle but not as

clearly erroneous.

-16

The defendants have cited possible interference

with existing mechanisms and arrangements„ We repeat

that artifacts of convenience may not be bars to consti

tutional rights, but the court below has manifested no

disposition to disturb the status quo unnecessarily. If

such needs will be made known in concrete form, they can

in all likelihood be accommodated. See, e.g. A. Ia 539,

541-542.

Lastly, with respect to metropolitan faculty desegre

gation, we noted in our Opening Brief (p.41, n.39) that the

parties appeared to be in agreement here as to its appro-

pj^Lateness. That conclusion was based, on the ract that

the intervening teachers had not appealed and that neither

the State nor suburban Petitions for Permission to Appeal

had cited that as an issue. However, the Michigan Educa

tion Association, a non-party which has already been granted

amicus status in the court below (A. Ia 562), seeks here a

writ of prohibition or in the alternative to intervene.

We view it as settled that courts may grant that

ancillary relief which is reasonably necessary and related

to effectuation of the principal decree. Questions of

related relief necessary to vindicate constitutional rights

are not new in school cases. See, for example, .Brewery.

Norfolk School Bo rd, 456 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1972); cert

denied and stay vacated, U.S. , 40 U.S.L.W. 3544,

May 15, 1972. And we believe it is established that con

-17

tract and tenure rights must yield to the Constitution.

United States v. Greenwood Mun, Sep, School Digt. , 406

F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969).

In any event, whether the interests of this organize—

tion and its members, and their contentions, are not ade

quately represented by the intervening school districts

and the state, or by the organization as amicus curiae,

should be considered initially below.

We have previously said virtually all that we can about

the power of federal courts to order what is necessary to

remedy constitutional violations: not merely to prohibit

an impermissible practice but affirmatively to bring about

a condition of constitutionality. Compare Ford Motor Com

pany v. United. States. U.S. , 40 U.S.L.W. 4352, 4356,

note 8 (No. 70-113, March 29, 1972). The position of the

state appears to remain, not that it lacks the power or

wherewithal in any ultimate sense, but that it may only be

required to act within the framework of its existing arrange

ments. (State Brief, p. 102 et. seq.) Not that the state

lacks the wit or authority to devise feasible constitu

tional arrangements, but that its choice to do otherwise may

not be disturbed. The notion that the Constitution’s supre

macy may be limited by state policy, where the effects are

so harmful and the policy so unsupported, has been uniformly

rejected in areas ranging from access to the courts (Boddie v.

Connecticut, 91 S. Ct. 780 (1971)), to voting and welfare

-18-

rights (Dunn v» Blumstein, 31 L 0 Edc 2d 274(1972),

Shapiro v, Thompson, 397 U.S. 254 (1970)), and to school

desegregation (Haney v, County Board, 429 F.2d 364, 368

(8th Cir. 1970)).

It has been suggested that the issues here are of

such novelty and magnitude as to be without precedent.

We do not seek to minimize them unrealistically, but in

that regard we invite the attention of the Court and the

parties to two Third Circuit cases decided more than a

decade ago: Evans v. Ennis, 281 F.2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960);

Evans v. Buchanan, 256 F.2d 688 (3rd Cir. 1958). Those

cases involved statewide and local school desegregation

orders directed to the State Board of Education as well as

local districts, and what powers were lodged where was in

issue. The court made the following observations which

we find instructive here.

The appellants, who are members of

the State Board of Education_and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion, filed joint answers. . .asserting

that the power to effect desegregation

lies not in them but in the local school boards. The members of the boards

of education of the school districts0...

assert that the local boards do not possess

the power or jurisdiction under the

school laws of Delaware. . • .(Buchanan,

at 690.)

The State Superintendent of Public

Instruction and the members of the

State Board of Education assert,

that the powers necessary to effect ̂

these results are vested by the perti

nent Delaware statutes solely in the

local district school boards. (Buchanan,

at 692.)

i -19-

Among the statutory duties entrusted

to the State Board of Education. . . is

that of maintaining a "uniform, equal

and effective system of public schools

throughout the State. . ." . . ./T/he

statutory mandate to the State Board of

Education continues to exist and require

that body to maintain a uniform, equal

and effective public system in the State

of Delaware. To hold otherwise would

be nullification.

The contention of the members of the

State Board of Education that the man

dates of that body have no force upon

the local school boards and the persons

who comprise them is erroneous. The

time when the Delaware educational_ system

was encompassed by a loose federation

of "425 educational republics" has long

since passed. (Buchanan, at 693.)

The Court then goes on to detail Delaware5s educational

statutes, strikingly similar to those of Michigan, to illu

strate the state*s role; and to hold that, if local school

boards flout state directives, then appropriate orders may

issue.

Towards its conclusion the cor t states (in 1958):

The members of the State Board of

Education and the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction may not delay

further in the formulation and sub

mission of such a plan. They must

prepare and submit it promptly. The

time for hesitation is past and the

time for definitive action has

arrived. The law as enunciated by

the Supreme Court of the United States

must be obeyed, by all of us. (Buchanan,

at 695.)

Two years later the same court had occasion to consider

Delaware* s grade—a—year plan, which the district couxc had

approved, because

. . . integration at a more rapid rate

would overcrowd the schoolrooms, over-

-20-

tax the teachers, and have a roost

undesirable emotional impact on

some of the socially segregated

communities of Delaware.

* * *

We cannot agree. (Ennis, at 387"388®)

The court went on to make the following pertinent observa

tions.

Doubtless integration will cost the

citizens of Delaware money which other™

wise might not have to be spent. The

education of the young always requires,

indeed demands, sacrifice by the older

and more mature and resolute members of

the community. Education is a prime

necessity of our modern world and of

the State of Delaware. We cannot

believe that the citizens of Delaware

will prove unworthy of this sacred

trust. (Ennis, at 389.)

Plus ca change® . . .

We conclude this portion by reiterating that judicial

remedial power has been exercised by the district court

here commensurate with the constitutional violation. jk̂ ann,

402 U.S. at 15® Also, the remedy is practicable, sound,

and still open to the receipt of timely, effective alterna

tives from Michiga authorities.

-21

II.

MISCELLANY

With the few exceptions hereinafter noted, defen-

dants-appe11ants do not attack the lower court's factual

findings underlying its conclusion that school segregation

in Detroit results from unlawful state action. Rather,

defendants proffer selective, isolated readings from the

district court's initial ruling of September 27, 1971,

together with several untenable legal theories in support

of a general contention that the district court erred as a

matter of law. Defendants' various lines of attack are

these: (1) the district court failed to find that any of

defendants' actions were for the purpose or intent of segre

gation (Detroit Board's Brief at 22-32; State's Brief at

38-89); (2) the court failed to find that defendants' actions

were the proximate cause of school segregation (Detroit

Board's Brief at 33-40; Xntervenor School Districts Brief

at 42); (3) the court failed to identify individual schools

whose racial compositions specifically result from particu

lar discriminatory acts, which identification would assertedly

limit both the finding of violation and the remedy (State's

Brief at 97-101; Interverior School Districts' Brief at 40-42).

-22'

Additionally, certain of the defendants argue that

the district court (1) erred in admitting into evidence

proof of racial discrimination in housing (State's Brief

at 40-46), (2) erred in implicating State defendants in

the segregatory pattern of school site selection and con

struction (State's Brief at 47-50), (3) erred in denying State

defendants' Rule 41(b) motions to dismiss and in making

findings against State defendants based on evidence received

after the motions to dismiss were filed (State's Brief at

51-68), (4) erred in finding State discrimination against

Detroit vis-a-vis suburban school districts in the areas

of transportation funding, bonding limitations and the

school aid formula (State's Brief at 68-87), (5) denied sub

urban defendants due process of law in the proceedings b'low

and by involving some of them in the remedy without having

joined them as parties at the inception of this litigation

(Intervenor School Districts' Brief at 42-47), and (6) erred

in failing to convene a three-judge court to enter the June

14 rulings (Intervenor School Districts' Brief at 47-55).

Some of these purported issues and related matters we

will treat with greater dignity than the quality of their

presentation deserves; others we will deal with in the margin.

A. The Violation Challenges

Both the assertion that the district court failed to

find purpose or intent on the part of defendants to segre

gate and the contention that such finding is a requisite part

-23-

of a Fourteenth Amendment violation are without merit,

factual or legal. As to the lack of factual merit, we

respectfully invite the Court to read the lower court’s

opinion of September 27, 1971 in its entirety. Such a

reading, we submit, patently refutes defendants’ conten

tions (based upon chronologically misplaced excerpts) that

the district court did not find intentional segregation.

But defendants urge that the failure of the court to

find their actions "to be taken with any evil purpose

strains the rationale of the concept of de jure segregation..."

9/

(Detroit Board’s Brief at 30). The Fourteenth Amendment,

however, has never known a requirement that subjective

motive must be proved to show a violation. Were that the

test, "the constitutional provision— adopted with special

reference to Negro citizen's protection— ■would be but a

vain and illusory requirement." Norris v0 Alabama, 294 U.S.

587, 598 (1935)o Thus, even if a showing of intent is

necessary to establish a constitutional violation (as the

10/district court held), proof of subjective malevolence is

9/ To this contention, the Detroit Board provides its

own best answer (at p. 39): "The requirement of a finding

of intent or purpose... is not grounded in a concept of mens

rea..0."

10/ But cf. Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School

Dist o7 No7~71-2397 (5th Ci'r. Au£7 2, 1972) ( en banc fTsilp op.

at~16-17); Wright v» Cox- cil of the City of oona, 40 U.S.L.W.

4806 (June 11, VZTF), '

-24-

not required* "In judging human conduct, intent, motive

and purpose are illusive, subjective concepts, and their

existence usually can be inferred only from proven facts.

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, F.2d , (5th Cir.

1972) (en banc), affM 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971).

11/ As to the proven facts, nowhere in their briefs do

defendants claim that optional zones, discriminatory busing,

gerrymandering of attendance zones and feeder patterns,

segregatory site selection and school construction, Act 48,

etc., did hot occur, or came about unexpectedly as if by

Act of God. Nor do defendants deny the massive racial_im

pact of these actions. CjE. Ely, Legis 1 ati.vu__gnd _ _ i s -

trative Motivation in Constitutional Law, 79 YALE L.J.

T Z G 5 7 T 2 3 5 ' ( W f ) . """" ‘ _Defendants’ half-hearted attempts to counteract a few

of the district court’s specific findings (see Detroit_

Board’s Brief at 25 n.l; State’s Brief at 88-94) are with

out record support, as demonstrated in plaintiffs Opening

Brief (pp* 8**40). We do, however, note mi statements of ̂

the record in two such instances. (1) The Detroit Board

argues (at p. 25 n.l of its Brief) that the north-south

orientation of attendance zones had been established and

maintained "because of the arterial system of streets...

and the bus transportation routes in existence... Whether

or not the transcript page (2931) cited in support or this

assertion amounts to "credible record evidence, it is

contradicted by clear and convincing evidence from the same

witness (A. IVa201; IXa393) as well as the Superintendent

(Xa 43-55; 11/4/70 Tr. 38) and others (A. Ilia 51-56; P.X.

105 at p. 450). (2) The State defendants state that the

busing of black students from the Carver School District

to black Northern High School within the Detroit District

occurred "during the years 1949-52." (State s Brief at

88-91). Whatever the archives of the State Attorney General s

office may reveal, the records of the Detroit Board or Educa

tion reflect the existence of this overt segregation practice

as late as the 1959-60 school year (A. Ila 193; P.X.^78a at

pp. 23-24 of the Center District guidebook). There is no

contrary evidence in the record. Fur;hermore, the elemen

tary schools in the o3.d Carver District remain segregated

(see Plaintiffs' Brief at 53 n.48).

-25-

Accord, Davis v> School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 913 (1971). In short,

this Court*s decisions in Deal and Davis, contrary to the

Detroit Board*s contention (Detroit Board’s Brief at 39),

12/

require affirmance.

12/ In a last-ditch effort to avoid the district

court"*!; finding of purposeful segregation, the State defen

dants argue that it defies "human experience" for the

district court to find intentional segregation of pupils

in the face of its commendation of the Detroit Board with

respect to faculty integration. (State*s Brief at 37-38).

The fact is, however, that this purported inconsistency

strengthens, rather than weakens, the violation findings

pertaining to pupil segregation, for it demonstrates the

strict standard of proof applied below (see Plaintiffs|

Opening Brief at 40-48 and note 39). Furthermore, it is

to be remembered that much segregatory conduct is an effort

to accommodate community sentiment (cfi. Clemons v. Bd0 of

Educ. of Hillsboro, 228 Fc2d 853, 85T“(6th Cir. 1956)

X^tewart', X., concurring)). Thus while white Detroit was

openly hostile to black faculty members prior to 1960

(A. Ilia 180-181, Ilia 137; 1 Tr. 45-49), the intensity^

of the hostility to black teachers appears to have subsided

somewhat, so that, coupled with strong integration-oriented

leadership in the personnel division, some progress in the

area of faculty integration has been made since the later

1960's. (See Plaintiffs* Brief at 40-48). As the record

and Act 48 demonstrate, however, no such change in the

attitude of white Detroit has ever occurred with regard

to pupil integration; and the school authorities persisted

in accommodating public sentiment at least until adoption

of the April 7, 1970 plan of partial high school desegrega

tion. # #Similarly without merit is the State’s implied contention

that no State purpose or intent can be found because racial

discrimination contravenes the law of Michigan, Act 48 not

withstanding. But this argument only serves to magnify the

invidiousness of the discriminatory actions found by the dis

trict court. Clemons, supra. And, although some components

of Michigan’s educatiohaT system outside of the Detroit

metropolitan area may have complied with the Fourteenth Amend

ment, others have not. See, Davis v. School Dist0 of Pontiac,______ ___ , ’F.2d (6th Cir."

v. Beni:oh "Harbor School"Uist., C.A. No. 9 (W.D.

Kalamazoo Bd. o£ Educ

26-

Passing over the Detroit Board’s contention that

the district court failed to find a causal connection between

school authorities' discriminatory acts and existing segre-

13/gation, we come to the contention of the Intervenor

14/School Districts and the State defendants that the lower

13/ This allegation (Detroit Board's Brief at 33-40) falls

on its face, for the lower court found "that both the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education have committed

acts which have been causal factors in the segregated condi

tion of the public schools of the City of Detroit." (Mem.

0po, la 210) (emphasis added).Equally frivolous is the Detroit Board's proposition

(at pp0 37-38) that a lack of "causal nexus" is evidenced

by the district court's finding that the current condition

of segregation is so pervasive that it can no longer be com-

pletly remedied within the confines of the city proper0 It

would be an anomaly, indeed, if the law immunized those who

violated it best.

14/The position of intervenor-appellants as to the dis

trict court's violation findings typifies the quality of their

contribution both below and here. They begin their attack

on the opinion of September 27, 1971 by confessing that

"counsel.../Have not/ had an opportunity to review the

record..." "("intervenor School Districts' Brief at 40). Un

daunted by their own ignorance, however, they proceed to

find error, knowing not whether their suggested school-by-<

school inquiry was in fact made. Significantly, the Detroit

Board defendants, who have presumably read the record, do not

make this argument.But even more questionable is intervenors' belated excuse

for their ignorance, i.e., the alleged "unavailability of

/the/ record prior to the preparation of the appendix in

connection with the instant appeal and the time constraints ̂

imposed by the time schedule in connection with said appeal...

(p. 40 n.26). First, aside from the fact that counsel for

the State, Detroit Board and plaintiffs have each had com

plete copies of the transcript of the trial on the merits

since the day it ended and although, to our knowledge, inter

venor s have never requested a review of same of any of these

parties, the entire record of this case has always been

available in the district court, including since the February,

1972 motions to intervene. Second, we respectfully suggest

that interveners' determination to challenge the September 27,

1971 ruling came at the last minute. Intervenors' Petition

(cont'd on next page)

-27-

court erred in not providing a list of schools which

are segregated as a result of specific discriminatory

acts directed against them individually. Such a listing,

it is argued, limits not only the violation finding, but

the remedy as well. This argument turns the Fourteenth

Amendment on its head; it is both practically and legally

absurd; it ignores the record; and it improperly shifts

the remedial burdens from defendants to either the dis

trict court or the victims of pervasive discrimination.

First, defendants efforts to transfer their own

failures into reversible error must be forthrightly re

jected. After intensive factual inquiry, the district

court found system-wide school segregation. If those

findings are supported by substantial evidence, the remedy

must speak to the system, for even if defendants are correct

that the law requires a school-by-school approach (a proposi

tion which we dispute below), the district court has made a

painstaking and thorough inquiry into practically every

facet of the Detroit system and found the entire system

suffering by segregation from the effects of defendants'

racially discriminatory actions.

14/ (cont'd)

for Permission to Appeal, previously filed with

this Court on or about July 28, 1972, sets forth (at pp» 5-6)

four general issues which intervenors proposed to present

for review on this appeal. None of these issues is even

remotely related to the lower court's violation findings.

It thus appears that intervenors' lack of knowledge is more

properly attributable to their own strategy and decision

making tardiness.

15/ We doubt that there is any school in the City of

Detroit which the extensive and detailed record does not reveal to

(cont'd on next page)

28-

Moreover, if there are specific' schools which defendants

claim are immune from remedy, the record does not reveal

them because no such claim has ever been presented to the district

16/court. Surely, if defendants are right in their legal

15/ (cont’d)be affected by the unlawful state action of school

authorities,, For example, the Detroit Board argues, in

support of its contention that no proximate cause was

shown, that the six (in fact, there were 8 in 1959) optional

zones represented "but a small fraction of the total

twenty-one high school constellations..." (Detroit Board’s

Brief at 36). Putting aside such practices as discrimina

tory busing, zone and feeder pattern gerrymandering, and

the massive site selection and construction violation, the

Detroit Board ignores the true impact of its dual zoning

practices. A "high school constellation" in Detroit refers

to one of the 21 attendance-area high schools together with

its elementary and junior high feeder schools. Accepting,

arguendo, the number as six optional zones, it must be ̂

remembered that each optional zone was created between white

and black high school constellations. Thus, six optional

zones directly affected twelve high school constellations

containing over one-half of Detroit’s schools. More im

portantly, dual zoning was utilized to seal off virtually

all of the black schools in Detroit from all of the white

schools. (See Plaintiffs’ Opening Brief at 16-19, 68-71).

Clearly, "Had the school authorities not specifically segre

gated the minority students in certain schools- other schools

may have developed as desegregated facilities. 1 United States

v. Texas Education Agency (Austin), No. 71-2508, slip op. at

5(5 (5th Cir. Aug. 2,19727. “

16/ Only intervenors, who have never readthe record,^

have Tdentified a school (here, not below) which they claim

is exempt from the remedial process because the school (Mum-

ford.), now black, was once white. (Intervenor Districts'

Brief at 41). These and otner defendants rely upon United

States v. Board of Educn of Tulsa, 459 F.2d 720 (10th Cir.

T972T7cert..IJehdTng; /uisHrTT'supra (concurring opinion on

remedy); and Keyes v 0 School Dlst0 No0 1, 445 F.2d 990 (10th

Cir. 1971), cert, granted, "504 U.S. 1036 (1972), for the

proposition that some schools/ racial compositions in a

system which has practiced racial discrimination may be found

to be not the result of discriminatory actions. Whatever

the legal merit of these decisions may be, it is to be

emphasized that each of these decisions involved factual

(cont’d on next page)

29-

proposition, it is their responsibility, indeed, their

burden, to convince the district court in the first

instance, as this Court does not try cases de nnvo0 The

district court could hardly have committed reversible

error by failing to decide an alleged factual defense

never presented to it.

Second, we submit that, as a matter of law, when

"/t/here is established... an overwhelming pattern of un

lawful segregation that has infected the entire school

system, J T J ° select other than a system-wide remedy would

be to ignore system-wide discrimination and make conver

sion to a unitary system impossible0" Cisneros, supra,

17/slip op. at 20. Whatever the abstract validity of a

contrary view, there can be no other conclusion in this

16/ (cont'd)determinations by the trial court that some or all

schools were not segregated by unlawful state action. Had

intervenors read the record they ŵ ould know that the proof

of discrimination in Detroit is not^susceptible to com-

partmentalization or sectioning as in Keyes and Tulsa; and

they would know that even if such a school-by-schooldeter

mination is most important "in some populous school districts

embracing large geographical areas" (Austin, supra, slip op.

at 76) it is, at best, impossible to H m d any "innocent"

schools in Detroit because of the system-wide pervasiveness

of the pattern of discrimination. See Boykins v0 Fairfield

Bd0 of Educ., F.2d (5th Clr. Feb. 23, 1972); KeTTy

v. MetropoTitan Comity Board, Nos. 71-1778-79, slip op. at

7 T T ^ t F c I F r ^ y 3 ( J 7 ^ b 7 7 y 7 1 N o . 71-2715, (5th

Cir., July 14, 1972).

17/ The import for the Fifth Circuit of Judge Bell's

concurring opinion in Austin, supra, upon which defendants

rely heavily in support oTTheTrcontent ion that a school-

by-school approach to the remedial process is required, is

cast into considerable doubt by the court's en banc decision

(cont'd on next page)

-30-

case0 Here we deal with systematic discrimination of

longstanding in the Detroit public schools. In such cir

cumstances, courts, having found a pervasive system-wide

violation, are ill-equipped to then make the sort of

complex socio-historical determination as to the reason

for each school's racial composition which defendants*

approach would require. For the very reason that "all

things are not equal in a system that has been deliberately

constructed and maintained to enforce racial segregation"

(Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at ), the school-by-school

remedial inquiry, in a case such as this, is incapable of

resolution; it assumes a fact that never was— i.e., that

although black people as a racial class have been the

objects of systematic discrimination, some black people

may have escaped the effects thereof.

The remaining assignments of error to the district

court's violation findings— proof of housing discrimination,

17/ (cont'd)

of the same day in Cisneros, which also received

the support of a majority of 'the court (Judge Thornberry,

who did not participate in Austin, and Judge Ingraham, who

voted with Judge Bell in Austin, "make a majority_for Judge

Dyer's Cisneros opinion). In any event, we submit that the

individual-school approach must be rejected for the reasons

set forth in Cisneros and Judge Wisdom's opinion for the

court in AustinT’"

18/ (State's Brief at 31-37). We have dealt with this

issue~Tn our Opening Brief, but reiterate briefly here that

the district court's ruling was based on evidence of sub

stantial discrimination by defendant school authorities.

And we have demonstrated active partnership onthe part of

the school authorities with the agents of housing discrimina

tion. It does not appear from the reported decisions in Deal

(cont'd on next page)

-31-

the State defendants’ duties and responsibilities regarding

19J

site selection and construction, and State discrimination

in the areas of transportation funding, bonding authority,

. 2 0J

and school aid formula — are disposed of in the margin and

must be rejected for the reasons there stated. In sum,

18/ (cont’d)

that the rejected housing proof in that case was

offered to show related and interrelated discriminatory

actions by the school authorities. Such a relationship was

established and found below; we submit that its proof was

clearly admissible and judicially cognizable under the

Fourteenth Admendment.

19J (State’s Brief at 38-40). Reality and the Consti

tution are simply defied by State defendants’ assertion that

they have no responsibility under the Equal Protection

Clause for the manner in which State money is expended for

the location and construction of State-supported public

schools. The Fourteenth Amendment obligation was not, and

could not have been, withdrawn in 1962 when the legislature

removed the requirement that the State Board approve and

authorize site selection and construction.

20/ (State's Brief at 54-70). As to bonding limitations

and transportation funding, see Plaintiffs' Opening Brief

at 34-39. As to the school aid formula issue, we make two

points. First, and more importantly, the issue is irre

levant to the violation finding and none of the district

court's orders have been based thereon; rather, all orders

and subsequent rulings have been based on the finding of

unlawful segregation. The remedial action decreed, how

ever "should produce schools of like quality, facilities,

and staffs." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at . Second, the

lower court's finding in this regard is certainly supported

by the record; if the district court was in any way misled

it is not for State defendants to complain, for they (as

will be next discussed in the text) had chosen to absent

themselves from part of the trial at which the Detroit Board

presented further evidence in support of this finding.

-32

the lower court's violation findings must be affirmed in

their entirety.

B. The Rule 41(b) Issue

With regard to this issue, the State's position turns

Rule 41(b), F.R.C.P., inside out and places the fact

finding powers of the federal courts at the mercy of liti

gants who choose to pack up and leave in mid-trial.

Rule 41(b) permits granting of a motion to dismiss

at the close of plaintiffs' case-in-chief only if "upon

the facts and the law the plaintiff has shown no right to

relief." The facts presented during plaintiffs case-in

chief (or at earlier preliminary hearings), and which are

set forth in our Opening Brief (pp. 33-40; 76-80), demon

strate that no error was committed by the district court

in denying the State's motions. Given, that, the argument

(State's Brief at 52-54) that the court was nonetheless

barred from making findings against the State defendants

based on evidence received after the motions were lodged

21/

must be rejected.

21/ When counsel for State defendants requested "per

mission to leave" at mid-trial, he was informed by the

Court: "That is a matter entirely within your judgment."

(A. Ilia 191)o Defendants exercised their judgment, but

surely they did not expect to bring proceedings, or fact

finding, to a halt thereby.

-33-

The suburban, interveners argue, for the first time, that

the district court's June 14 rulings and order could only

be properly issued by a three-judge court convened pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. §2281; the failure to convene such court,

they contend, requires reversal of those rulings and order.

While we agree wholeheartedly that intervenor "school

boards are 'state officers'" (Intervenor Districts' Brief

at 52), the case is otherwise entirely unrelated to the

provisions of §2281. Nothing in the June 14 order even

resembles "/a7n interlocutory or permanent injunction restrain

ing the... action of any officer of /.the/ State" from

doing anything. That order is not even directed at any of

the suburban intervenors, and as to the State officers to

whom it is directed, it only requires study, planning and

reporting. Furthermore, the order does not enjoin, does

not even spealc to, the "operation or execution of any State

statute...," much less "demolish...the Michigan educational

system...." (Intervenor Districts' Brief at 54).

Finally, even to the extent that the June 14 order re

quires planning and reporting it is not based "upon the

ground of the unconstitutionality of /any StateJ statute..."

On its face, we submit, the three-judge court argument, never

presented to the district court, is without merit.

C. The Three-Judge Court Issue

-34-

D. The Due Process Issues

Suburban intervenors seek reversal on the grounds that

they were denied due process in and by the proceedings below,

and also by the failure to join them as parties at the

inception of this litigation. (Intervenor Districts’ Brief

at 42-47). Although we are not informed of the "life,

liberty or property" (Due Process Clause) which intervenors

claim to have been deprived of by the various asserted pro

cedural errors, apparently it is their assumed right to re

main white components of the State public education system

in the Detroit metropolitan community which they feel has

been prejudiced below0

Turning to the substance of the assigned errors, sub

urban intervenors claim that the^were denied due process in

this non-jury, non-criminal case by the following: (1)

the failure of the district court to conduct oral argument

after receiving written briefs on the legal propriety of con-

23/

sidering a metropolitan plan of desegregation ; (2) the

22J V7e agree with the Detroit Board that "Suburban

defendants..„seem obsessed with the concept of guilt, operating

on the principle that the provision to small children of their

Constitutional rights is, of all things, a punishment to be

visited upon the sinful and withheld from the righteous..."

(Detroit Board’s Brief at 38).

23/ Intervenors seem particularly aggrieved by this

point~'because the court's ruling on the issue "reject^ed/

the contentions of Intervenor School Districts." (Brief

at 43).

-35

district court's ruling that Detroit-only desegregation

plans were constitutionally inadequate without intervenors

24/

having participated in the hearing on such plans ; (3) the

lack of notice to intervenors of the "charges against them" and

_ 25/the lack of opportunity "to be heard in /their/" defense" ;

(4) the refusal of the lower court to receive "testimony

regarding safety in schools" as well as the deposition of

24/ At this point, intervenors argue, they "had been

effectively foreclosed from protecting their interests."

(Brief at 43). Again, we do not know to what "interests"

they refer, but they were permitted to intervene "for two

principal purposes: (a) To advise the court, by brief,

of the legal propriety or impropriety of considering a

metropolitan plan; (b) To review any plan or plans for the

desegregation of the so-called larger Detroit Metropolitan

area, and submitting objections, modifications or alterna

tives to it or them...." (A. la 409 ). Intervenors

responded to the first condition and claim only that this

interest was not adequately protected because they were

not allowed to persuade by oratory as well as written legal

argument. The second condition they chose, by and large,

not to respond to, and it is this problem, in part, to

which the district court spoke when it referred to the

"awkward position" of the Allen Park intervenors (40 dis^ tricts) in having single representation (A. Ia 502-03)~i.e.,

counsel was in the impossible position of having to urge

that some of his clients (all of whom opposed any form

of metropolitan remedy) could not, within the practicali

ties of the situation, be included in a desegregation plan,

while others could; or, as was the case, making no contri

bution at all.

25/ in support of this contention intervenors cite

In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948), a criminal case. Again,

plaintiffs and the other proponents of complete school

desegregation are not seeking criminal sanctions. The

Fourteenth Amendment does not require the parties here to

proceed by indictment or information.

-36-

Dr. David Armor in opposition to desegregation ; (5) the

court's intervention order limitation on examination of

27/

witnesses to one suburban counsel per witness. The

short answer to most of these points is that throughout

the two-year history of this litigation any claimed "interest"

of these intervenor "officers of the State" have been ade

quately and vigorously represented by their parent State

defendants, who have staunchly and consistently opposed

even the discussion of a remedy which would extend beyond

the boundaries of the City of Detroit. The lower court was

certainly within its authority in placing conditions and

26/

26/ The Well's subpoena sought to introduce "records

as to the instance of attacks, violence and things of

that type that have occurred in various schools in the

Detroit School District" (A. Villa 88), and the Armour

deposition was offered to demonstrate the alleged "effects

of busing based upon studies of areas where they have had

what Dr. Armour classified as induced or forced integration."

(A. Villa 117). Clearly, neither offer had any relevance

to the issue before the court: school desegregation. Any

way, intervenors do not show, or even allege, how the

district court's ultimate rulings would have or should

have been affected had these offers of proof been received

into evidence.

27/ Intervenors again fail to allege or show how

they were prejudiced by the intervention order. Two rea

sons are obvious: (1) the order expressly provided that

more than one attorney for intervenors could examine a

witness upon a showing of cause; (2) throughout the metro

politan hearing every intervenor who so chose was permitted

to examine any witness.

-37-

limitations on the interventions permitted, and, as

we have shown above in the margin, no prejudicial, let

alone reversible, error was committedG

For the same reason, i.e., the presence of inter

veners' parent State authorities, the claim that the

suburban districts should have been joined as parties

at the inception of the lawsuit is without merit. The

suburban intervenors simply are not indispensable parties

within the meaning of Rule 19, F.R.C.P.— their absence

would not prevent "complete relief.0.among those already

parties" (Rule 19 (a)(1)), nor do they have a claimed

"interest relating to the subject of the action and f a x e f

so situated that the disposition of the action in /theirJ

absence may (i) as a practical matter impair or impede

/their/ ability to protect that interest or (ii) leave

any of the persons already parties subject to a substantial

risk of incurring double, multiple, or otherwise inconsis

tent obligations...." (Rule 19 (a)(2)). The due process

arguments are without merit.

28/ The interests of these intervenors were adequately

represented by the State defendants. See generally 3B Moore's

Federal Practice. PP 24.09-1/57, 24.08/77; Hatton v„ County

Bd.'.' of Ed'u'c . , 472 F02d 457 (6th Cir0 1970);""Spangler v.

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 427 F.2d 1352 (9 th Cir. T970).

The trial court is authorized to limit intervention to cer

tain issues and place conditions on it. 3B Moore's, supra,

P24.10/57. Thus, an intervenor may not be permitted to

assert any claim or defense previously decided by the court.

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., 298 F.Supp. 288 (E.D.

La. 1069)'; 3b Moore's, 124.16/57; cT. Hatton v. County Board,

supra. Intervenors' thus take the case as they £ind it, Common

wealth v. Sincavage, 439 F.2d 1133 (3d Cir. 1971), and are

in all respects subordinate to the main, original parties.

Moore's, supra, P 24.16/57.

-38

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs-appellees urge that the stay previously

entered be vacated, that the orders on appeal be affirmed,

and that the case be remanded to the district court for

further consistent proceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis r . lucas ‘

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Bldgc

Memphis, Tennessee

NATHANIEL JONES

General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

17S0 Broadway

New York, New York

/ /f t f .'is 'L * i & / £ /

ROLD FLANNERY

R. DIMOND

)BERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

E. WINTER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio

Attorney for Plaintiffs

JACK GREENBURG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that two copies of the foregoing Reply

Brief have been served upon all counsel of record, either by

hand delivery or U.S. Mail, postage prepaid, this 21st day

of August, 1972.