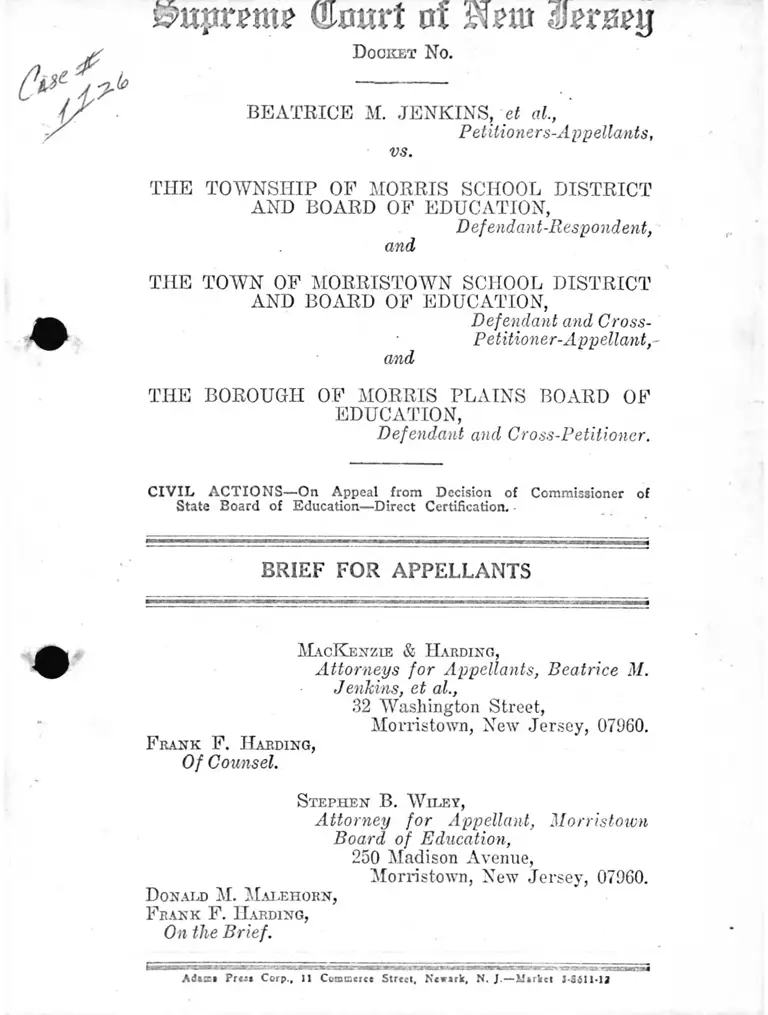

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District and Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 23, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District and Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1971. 39596aad-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/188bc880-ce34-471c-8a17-1f2d2ff5fc03/jenkins-v-township-of-morris-school-district-and-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

mxprmiz (mrnrt ox mm lkxm$

D ocket N o.

BEATRICE M. JENKINS, et al.,

Petitioners-Appellants,

vs.

THE TOWNSHIP OF MORRIS SCHOOL DISTRICT

AND BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendant-Respondent,

and

THE TOWN OF MORRISTOWN SCHOOL DISTRICT

AND BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendant and Cross-

Petitioner-Appellant,-

and

THE BOROUGH OF MORRIS PLAINS BOARD OF

EDUCATION,

Defendant and Cross-Petitioner.

CIVIL ACTIONS—On Appeal from Decision of Commissioner of

State Board of Education—Direct Certification.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

MacK enzie & H arding,

Attorneys for Appellants, Beatrice M.

Jenkins, et al.,

32 Washington Street,

Morristown, New Jersey, 07960.

F rank F . H arding,

Of Counsel.

S tephen B. W iley,

Attorney for Appellant, Morristown

Board of Education,

250 Madison Avenue,

Morristown, New Jersey, 07960.

D onald M. Malehorn,

F rank F . H arding,

On the Brief.

t j g T r a ^ r g m r x g a a ' j r . r j g m a zsr iT r z iL m a g — M ’y i s o t j T a w i t wr i ar - s N 3 r r . - a r a caa n a S

A d a s* Prc;a Corp., 11 Commerce Street, Newark, N. J .— Market 1-3611*12

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FA.GB

P rocedural H istory ............................................................ 1

S tatement of F acts ............................................................ 3

I—Summary of facts as found by hearing officer

and adopted by the Commissioner.................. 3

H—Outline of witnesses.......................................... 5

A. Studies and Reports of Morristown’s Two

Key Expert Witnesses .............................. 5

B. Outline of Other Witnesses Who Testi

fied at Hearing ............................................ 7

1. For the Petitioners ............................... 8

2. For the Town ........................................ 8

3. For Morris Plains ................................. 9

4. For the Township.................................. 9

III—Morristown and Morris Township as a single

community ........................................................ 10

A. Geographic and Physical Features ............ 10

B. Town-Township Boundary Line ................. 10

C. Interrelatedness of the Town and Town

ship in General ............................................ 11

1). Communities and Municipalities Surround

ing Morris Township.................................. 13

E. One Community Defined ............................. 13

FV7—Socio-economic and population differences be

tween Morristown and Morris Township....... 15

A. Housing ................................................ 15

u TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

B. Population ............................................ 17

(1 ) Morristown Population (Including

School Population) ............................. 18

(2) Morris Township Population (Includ

ing School Population) ....................... 19

V—The present Morristown-Morris Township

school systems ................................................... 21

A. In General .................................................. 21

B. Existing Sending-Receiving Relationships 23

1. Morris Plains and Harding Township 23

2. Morristown and Morris Township ....... 24

C. Sufficiency of Facilities .............................. 25

VI—Morris Township’s non-binding referendum .. 26

VII—Impact of withdrawal of Morris Township .... 27

A. Commissioner’s General Findings ............ 27

B. Underlying Proofs ...................................... 29

1 . Racial Imbalance .................................. 29

2. Socio-Economic Mix ............................. 31

3. Resulting Unit Size ............................... 32

4. Indirect Impact Through Resulting

General Population Change .................. 35

5. Financial Impact .................................. 36

VIII—Alternatives to Withdrawal other than K-12

merger ................................................................ 33

IX—Feasibility of merger ...................................... 39

X—Proposed High School not consistent with

merger ................................................................ 41

XI—Impact of failure to merge ................... 42

PAGE

A rgument :

I—Racial imbalance in the Morristown area

community schools requires school merger

as a constitutional r ig h t............................... 43

A. Thorough and Efficient System ............ . 45

B. Rationale of Booker................................ 50

C. Treatment of School District Boundary

Lines ........................................ ............... 57

15. The Morristown. Area Community as

the Unit ................................................... 6S

1. Considerations relating to neighbor

hood policy.......................................... 72

2. Considerations relating to costs....... 74

3. Trends towards withdrawal from the

school community by members of Hie

majority .............................................. 75

4. Reasonableness of community plan .. 76

II—The designation of Morristown High School

cannot be withdrawn without Department

of Education approval ................................... 79

A. The Facts and the Issue ......................... 79

B. The Sending-Receiving Statutes ............... 79

The Commissioner’s E rro rs ......................... 81

1. Department Position on “With

drawal” ............................................... 81

2. “Lack” of Facilities and N.J.S. ISA:

45-1 ....................................................... 86

TABLE OF CONTENTS i i i

IV TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

III—The Department has other unperceived

powers to deal with this situation .............. 89

A. N.J.S. 18A:6-9: Determining Contro

versies and Disputes ............................... S9

1. As a decision-making process, the

determination to •withdraw and re

fusal to merge were unjustifiable ..... 90

2. The decision to withdraw and re

fusal to merge will result in such

great harm to Morristown that it

should be set aside as unreasonable 93

B. N.J.S. 18A:45-1; Consent to New High

School Required ...................................... 98

C. N.J.S. 18A:18-2; Approval of Plans and

Specifications ............................. 100

D. N.J.S. 18A:13-34; Formation of a Re

gional District .......................................... 101

E. N.J.S. 18A:39-1, 38-3; 38-8, 9; exchang

ing students, a feasible last reso rt........ 102

F. N.J.S. 18A :4-10; 4-15; 4-16; 4-22; 4-23;

4-24: Sweeping Administrative Powers.. 103

G. N.J.S. 18A:55-2 State Aid Withholding- 105

Conclusion .................................................................... 106

C ases Cited

Andrews v. Ocean Twp. Board of Adjustment, 30

N. J. 245 (1959).......................................................... 96

Barksdale v. Springfield School Committee, 237 F.

Supp. 543 (D. Mass. 1965), vacated on other

grounds, 348 F. 2d 261 (1st C’ir. 1965)....................54,55

TABLE OF CONTENTS V

PAGE

Barone v. Township of Bridgewater, 45 N. J. 224

(1965) ............................... '........................................ 98

Board of Education, East Brunswick v. Township

Council, East Brunswick, 4S N. J. 94 (1966).....45,46,50

Board of Education of Elizabeth v. City Council

of Elizabeth, 55 N. J. 501 (1970)......................... 47,48,50

Board of Education of the Town of Newton v.

Board of Education of the High Point Regional

High School District, etc., 1966 S.L.D. 144..............85-87

Booker v. Board of Education Plainfield, 45 N. J.

161 (1965)..............44, 45, 51-54, 56, 66, 71, 72, 78, 98, 104

Borough of Cresskill v. Borough of Dumont, 15 N. J.

238 (1954)................................................................... 97

Borough of Roselle Park v. Township of Union, 113

N. J. Super. 87 (Law Div. 1970)............................... 9S

Bradley v. Milliken, 443 F. 2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970)..... 89

Bradley v. School Bd. of City of Richmond, Civ. No.

3353 (E. D. Va., Feb. 10, 1971)................................ 67

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.

2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968)................................................. 51

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)..57,59

Burleson v. County Board of Election Commission

ers of Jefferson County, 308 F. Supp. 352 (E. I).

Ark.), aff’d per curiam, 432 F. 2d 1356 (8th Cir.

1970) ................................................................61, 65, 66, S9

Crawford v. Board of Educ. of Los Angeles, No. 822

(Super. Ct. Cal., Feb. 11, 1970)............................. 51

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958)............................. 57

Cullum v. North Bergen Board of Education, 1952-

53 S.L.D. 62, aff’d. 27 N. J. Super. 243 (App. Div.

1953), aff’d, 15 N. J. 285 (1954).................................92, 94

VI TABLE OF CONTENTS

PA 03

Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E. D. Mich. 1970)......... ........._............... 51

Duff con Concrete Products, Inc. v. Borough of Cress-

kill, 1 N. J. 509 (1949)............................................... 95,96

Durgin v. Brown, 37 N. J. 189 (1962)......................... 94,95

Fisher v. Board of Education of the City of Orange,

1963 S.L.D. 123....,............................... ...... ...............43,44

Godwin v. Johnston County Bd. of Educ., 301 F.

Supp. 1339 (E. D. N. C. 1969).................................. 62

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960).............. 59

Grogan v. DeSapio, 11 N. J. 30S (1953)..................... 94

Gunsberg v. Board of Education of Teaneek, Bergen

County, 1961-62 S.L.D. 163....................................... 90

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E. D. La.), aff’d, 287 F. 2d 376 (5th Cir.

1961), aff’d mem., 36S U. S. 515 (1962).................... 58

Haney v. County Board of Education, Sevier County,

410* F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)................................. 1 61

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F. 2d 364 (Sth

Cir. 1970)..................................................................... 67

Hertz Washmobile System v. Village of South

Orange, 41 N. J. Super. 110 (Law Div. 1956), aff’d,

25 N. J. 207 (1957).....................................................93,94

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U. S. 385 (1969)................... 89

Jackman v. Bodine, 49 N. J. 406 (1967)..................... 60

Jackson v. Pasadena City School Dist., 59 Cal. 2d

876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 82 P. 2d 878 (1963).............. 55

Jones v. Falcey, 48 N. J. 25 (1966)..................... ......... 60

TABLE OF CONTENTS VII

PAGE

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, 303 F. Snpp.

279 (D. Colo. 1969).....................................................62,89

Kozesnik v. Township of Montgomery, 24 N. J. 154

(1957) ............. 96

Kunzler v. Hoffman, 43S N. J. 277 (1966).................. 96

Laba v. Newark Board of Education, 23 N. J. 364

(1957) ......................................................................... 104

Lumpkin v. Dempsey, Civ. No. 13,716 (D. Conn.,

Jan. 22, 1971).............. ................................................ 5S

Marburv v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803).................. 68

Masiello, In re, 25 N. J. 590 (1958)..................44, 90, 98,104

Morean v. Board of Education, Montclair, 42 N. J.

237 (1964).................................................................... 72

N. J. Good Humor v. Board of Commissioners of

Borough of Bradley Beach, 124 N. J. L. 162 (E. &

A. 1940)....................................................................... 94

Paulsboro Community Action Committee v. Board

of Education of Borough of Paulsboro (April 22,

1969) ................................................ 44,54

Reitman v. Mulkey, 3S7 U. S. 369 (1967)..................... 89

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 IT. S. 533 (1964)......................... 59

Rice, et ah v. Board of Education of Montclair, 1967

S.L.D. 312................................................................... 44, 54

Schults v. Board of Education, Teaneck, 86 N. J.

Super. 29 (App. Div. 1964), aff’d mem., 45 N. J.

2 (1965)....................................................................... 45

Scotch Plains Township v. Westfield, 83 N. J. Super.

323 (Law Div. 196*1)..................................................... 97

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 TJ. S. 1 (1948)............... . ...89,100

vm TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educ., 311 F.

Supp. 501 (E. D. Cal. 1970)...................................... 51

Termination or Modification of the Sending-Receiv

ing Relationship between the Board of Education

of Chatham Borough, In the Matter of the, 1961-

62 S.L.D. 144 (1962)...................................................82,87

Thomas v. Morris Township Board of Education,

1962 S.L.D. 106, aff’d, 89 N. J. Super. 327 (App.

Div. 1965), aff’d, 46 N. J. 581 (1966)....................... 92

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, 313

F. Supp. 380 (E. D. N. C. 1970).........................61,64,89

U. S. v. Bright Star School District No. 6, Civ. No.

T-69-C-24 (W. D. Ark., April 15, 1970)................... 61

United States v. Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N. D. Ga.,

Dec. 15, 1969).............................................................. 62

U. S. v. Halifax County Board of Education, 314 F.

Supp. 65 (E. D. N. C. 1970)..................................... 61,63

U. S. v. Texas, Civ. No. 1424 (E. D. Tex., Dec. 4,

1970) ........................................................................... 61,62

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 404 F. 2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968), 432 F. 2d 1147 (7th Cir. .1970)....... 51

Vetere v. Allen, 41 Misc. 2d 200, 245 N. Y. S. 2d

682 (Sup. Ct. 1963), modified, Vetere v. Mitchell,

21 A. D. 2d 561, 251 N. Y. S. 2d 480 (1964) aff’d,

Vetere v. Allen, 15 N. Y. 2d 259, 258 N. Y. S. 2d

77, 206 N. E. 2d 174 (1965), cert, denied, 3S2 IJ. S.

825 (1965)................................................................... 56

Washington Township v. Ridgewood Village. 26

N. J. 578 (1958).............................................. 98

Withdrawal of Students of the Borough of Haw

thorne from Central High School, Paterson, New

Jersey, In the Matter of the, 193S S.L.D. 665

(1933) ...........................................................................84-86

PAGE

Wright v. County School Board of Greensville Coun

ty, 309 F. Supp. 671 (E. D. Va. 1970)......................61,64

United States Constitution Cited

Fourteen tli Amendment ................................................ 57

New Jersey Constitution Cited

Article 1, paragraph 5 ............................................43,52,57

Article 8, Section 4 ............. ....................................... .43, 50

Statutes Cited

Congressional District Act of 1966 ............................. 60

L. 1929, c. 281 .............................................................. 85

L. 1933, c. 301 .............................................................. 85

L. 1956, c. 68 ................................................................ 84

N.J.S. ISA :2-l ............................................. 99,103

N.J.S. 18A :4-10.............................................................. 103

N.J.S. ISA :4-15.............................................................. 103

N.J.S. ISA :4-16 .................................................... .......... 103

N.J.S. ISA :4-22.............................................................. 103

N.J.S. 18A :4-23........................ 103,104

N.J.S. 18A :4-24............................................. 103,104

N.J.S. 18A :6-9 ..........................................................89, 92, 9S

N.J.S. 18A :8-l.................................................................. 58, 61

N.J.S. lSA:13-5.............................................................. 73

N.J.S. ISA:! 3-34 ................................................... 71,76,101

N.J.S. 1SA-.1S-2.............................................................. 100

N.J.S. ISA :33-l................. 56

TABLE OF CONTENTS ix

X TABLE OF CONTENTS

N.J.S. 18A :38-3 ..........

PAGE

........ ................ 102

N.J.S. 18A:38-8 ............ ......................... 102

N.J.S. 18A:38-9........... ......................... 102

N.J.S. 18A:38-11 .......... ............ 79, SO, 86, 87

N.J.S. 18A :38-12......... ......................... 80

N.J.S. 18A :38-13 ........ ..........79-84, 86-88, 99

N.J.S. 18A :38-20 ......... ................ 80, 81, 83

N.J.S. 18A :38-21 ......... ....................80, 81, 83

N.J.S. 18A :38-23 ......... ......................... 83

N.J.S. 18A:39-1 .......... .......................... 102

N.J.S. 18A:45-1........... .............. 86-89, 98, 99

N.J.S. 18A :55-2........... ......................... 105

R.S. 18:14-7 ................. ......................... 82, 87

R.S. 18:14-7.3 ............. ......................... 83

R.S. 18:14.7.4............... ..........................83, 84

R.S. 41:1-1 .............. . ..........................45, 68

O ther A uth orities Cited

Blumrosen, “Antidiscrimination Laws in Action in

New Jersey: A Law—Sociology Study”, 19 Rut

gers L. Rev. (1965):

1S9, 267 .................................................................... 56

Coleman Report, Ecpiality of Educational Opportun

ity (1966) .................................................................... 76

Kirp, “The Poor, the Schools and Equal Protection,”

in Equal Educational Opportunity (1969):

139 ........................................................................... 60

TABLE OF CONTENTS 33

TAGS

Note, “Racial Imbalance and Municipal Boundaries

—Educational Crisis in Morristown,” 24 Rutgers

L. Rev. (1970):

354 ....................................... ................................... 57

1 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Racial

Isolation in the Public Schools (1967):

p. 3 8 .......................................................................... 76

p. 259 ........................................................................ 58

Wright, “Public School Desegregation: Legal Reme

dies for De Facto Segregation,” 40 N. Y. U. L.

Rev. (1965):

285 .......... 60

Procedural History

On October 28, 1968, this suit was started by petition

of five Morris Township and three Morristown residents,

seven of whom have children attending public schools in

Morristown or Morris Township. The defendants were

four Boards of Education—Morristown, Morris Township,

Morris Plains, and Harding Township,* the latter three

districts sending high school students to Morristown High

School. The petition was filed with the Commissioner of

Education and sought various forms of relief related to

the combining of Morristown and Morris Township lower

grades and maintenance of integrated schooling at the

high school level.

Morristown by its answer and cross-petition sought a

complete Iv-12 merger of Morristown and Morris Tow -

ship schools and, alternatively, sought to prevent Morris

Township from withdrawing its students from Morristown

High School.

Morris Plains by its answer and cross-petition sought a

regionalization of schools at the high school level and

joined in the request to prevent the withdrawal of Mor

ris Township students from Morristown High School.

Harding also sought to prevent the withdrawal of the

Morris Township high school students, but upon consent

of all other parties, Harding was permitted to withdraw

from the case.

Morristown next moved for various forms of prelim

inary relief, including an interim restraint against Morris

Township from holding a referendum, scheduled for March

27, 1969, to authorize capital expenditures for a new high

* These school districts and Boards of Education are here

after normally identified just as “ Morristown” (or “ Town” ),

“ Morris Township” (or “ Township” ), “ Morris Plains” and

“ Harding” .

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

10

2

school, and Morris Township moved for judgment on the

pleadings. On March 21, 1969, the Commissioner denied

Morris Township’s motion for judgment on the pleadings

and granted Morristown’s motion to restrain the refer

endum pending a full hearing.*

Hearings were conducted before a hearing officer ap

pointed by the Commissioner on 15 dates in October, No

vember and December, 1969. Post-hearing briefs were

filed and the Commissioner rendered his final decision on

November 30, 1970. The Commissioner found the facts

in accordance Avith Petitioners and Morristown’s allega

tions but held he had no authority to act Avith respect to

either withdraAval or merger. He therefore dismissed the

petition, the cross-petition of MorristoAvn and the cross-

petition of Morris Plains and lifted the referendum re

straint. Morris Township then scheduled a neAv high

school debt referendum for March 4, 1971.

Petitioners and Morristown appealed the Commission

er’s decision to the State Board of Education and peti

tioned this Court for certification.

On January 20, 1971, this Court denied the request for

certification without prejudice to reapplication folloAving

the filing of a motion for leave to appeal in the Appellate

Division, provided the State Board of Education “has not

decided the matter by February 5, 1971”. This matter Avas

not decided by the State Board by February 5, 1971, and

Petitioners and Morristown then filed a motion for leave

to appeal Avith the Appellate Division, and simultaneously

reapplied to this Court for certification and for a stay of

the referendum scheduled for March 4, 1971.

* On appeal from the restraint directly to the Appellate Divi

sion that Court, in an unpublished opinion, Civ. No. Am-215-68,

affirmed 2-1. Morris Township sought review before this Court

and Avas scheduled to be heard informally, but discontinued its

appeal because the referendum date was at hand.

3

Certification and a stay of the referendum were granted

by this Court on February 23, 1971.

Statement of Facts

I. Summary of facts as found by hearing officer

and adopted by the Commissioner (See Ja 71 to 86).*

Morristown is a compact urban municipality (2.9 square

miles) encircled by Morris Township (15.7 square miles).

Morristown and Morris Township are so interrelated they

form one community. The Town and Township boundary

line does not adhere to natural or physical features, but

cuts across streets, neighborhoods and terrain arbitrarily.

All main roads radiate out from the square in the center

of Morristown into the Township. It is not practicable to

go from most areas of the Township to most other areas

of the Township without going through the Town.

The Town is the social and commercial center of this

single community, while the Township is primarily resi

dential in character-—mostly single family homes—and,

unlike the Town, has considerable undeveloped areas for

additional single family housing.

The black population of this community is centered in

the Town with a slight over-lapping into one non-expand-

able section of the Township. The Town’s black school

population is increasing rapidly and will continue to do

so. The Town elementary schools which are currently

43% black are expected to be predominantly black (70%)

by 1980, while the Township school population which is

now 5% black is expected to remain at that level or lower.

Morristown maintains a complete K-1.2 school system,

and the Township operates a K-9 system. The Town

* The notation “ J a ” is used throughout to denote the Joint

appendix of the individual petitioners-appellants and appellant

Morristown Board of Education.

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

4

and Township schools are located in close proximity to the

Town boundary line and to each other. Failure to merge

these two school systems will result in a predominantly

black school system completely surrounded by an almost

exclusively white district. Black neighborhood schools

will be within short walking distances of white neighbor

hood schools.

Morristown is the high school receiving district for

Harding Township, Morris Plains and Morris Township.

Harding adjoins Morris Township to the south; Morris

Plains adjoins Morris Township to the north. Harding

and Morris Plains send their 9th, 10th, lltli and 12th

grade students to Morristown, and operate Iv-S systems.

Morris Township sends its 10th, 11th and 12th grade stu

dents to Morristown High School and operates a K-9 sys

tem.

The sending-receiving relationship between the Town

and Morris Township has been in effect for over 100

years. A ten-year contract between the Town and Morris

Township whereby all 10th, 11th and 12th grade Town

ship students attend Morristown High School will begin

to expire in September 1972, in that the last 10th grade

class to be sent by the Township under the contract will

enter Morristown High School in September, 1971 (stay

ing through graduation in 1974).

Morris Township has served notice on the Town that

it intends to build its own high school to accommodate

all its high school students upon termination of this con

tract with Morristown. This notification followed a “non

binding” referendum conducted by the Township Board of

Education in January, 196S, to determine whether Town

ship voters preferred a K-12 merger with the Town or

the establishment of a separate Township high school.

The Commissioner ruled that the referendum was illegal,

as being’ without authority under school law, and an im

proper abdication of duty by the Township Board since a

5

majority of its members at the time were on record in

favor of merger.

Morristown High Sehooi is an excellent school with an

enrollment as of the dates of the hearing of 1,950. The

hearing officer found that the school can accommodate the

projected high school populations of the four districts

in question through 1974. ^

The hearing officer found that should Morris Town

ship be permitted to withdraw its overwhelmingly white

800 students from Morristown High School, it would have

an immediate adverse educational impact upon that school,

would result in the percentage of black students in the

high school immediately doubling from 14% to 28% (to

44% without Harding and Morris Plains) and by 1980

would reach 35% (56% without Harding and Morris

Plains); and would deny Township high school students

the right to an integrated education.

II. O utline o f w itnesses,

A. S tu d ie s a n d R e p o rts o f M o rris to w n ’s T w o K ey E x p e r t

W itn esse s

Morristown relied heavily upon two extensive studies

which were undertaken at the request of Morristown fol

lowing the commencement of this action. The reports of

both studies were admitted into evidence at the hearing, go

Because of the central importance of these two reports

they are set forth in a separate volume of Appellant’s

Joint Appendix (Ja 207 to 325).

One report was prepared by Candeub. Fleissig and As

sociates, a consulting community planning firm, under the

supervision of Isadore Candeub, President and founder of

the firm and an eminently qualified and nationally known

planning expert (For qualifications of the firm and Mr.

Candeub, see Ja 210 to 217; T 204 to 209). Mr. Candeub 40

10

20

30

40

6

and his firm were asked to investigate and report on (1 )

white-black population projections for both Morristown

and Morris Township through 1980; and (2) the extent

of interrelatedness between Morristown and Morris Town

ship (Ja 21S; T209, 210).

The population projections made by Candeub, Fleissig

and Associates were found reasonable and accepted as

accurate by the Commissioner (Ja 77). Similarly, the

conclusion reached by this Candeub report that Morris

town and Morris Township are so integrally and uniquely

related to one another that they constitute a single com

munity was also found to be true and accepted by the

Commissioner (Ja 80, 81).

The second of these two studies and reports was made

by Engelhardt and Engelhardt, Inc., educational consult

ants, under the supervision of Richard McKinley, vice-

president of the firm. This firm is likewise of national

scope and is particularly well known in New Jersey. It

recently completed a pilot study of school district reor

ganization throughout New Jersey for the “Mancuso

Committee”, the committee appointed in January, 1967 by

the State Board of Education to “study the next steps of

reorganization and consolidation in the school districts

of New Jersey” (Ja 280; T667).

The Engelhardt report concluded that, from an educa

tional standpoint, a withdrawal of Morris Township stu

dents from Morristown High School would have a substan

tial adverse effect upon all students currently attending

the school (Ja 303, 304). Mr. McKinley, in testifying at

the hearing before the Commissioner regarding this re

port, characterized this adverse impact as “disastrous”

insofar as Morristown High School and Town and Town

ship high school students are concerned (T730). The Com

missioner agreed with this conclusion of the Engelhardt

report (Ja 82, 83, 117).

7

The Engelhardt firm also concluded that a K-12 merger

of the Morristown and Morris Township school districts

was entirely feasible, and represented the solution of the

community’s educational needs which afforded the most

educational advantages and opportunities to all students

involved (Ja 310 to 315; T752 to 759). This report fur

ther concluded that a failure to achieve a complete Iv-12

merger would mean inferior educational opportunities for 10

Town students—particularly black students in the Town

elementary grades—because of the increasingly severe ra

cial and socio-economic differences between the Town and

Township (Ja 311; T751, 752). Again, the Commissioner

agreed generally with the Engelhardt firm’s conclusions

regarding the harmful educational effects upon both school

systems—particularly the black students of Morristown—

if merger of the two systems is not achieved (Ja 117).

The Commissioner, in the “conclusion” section of his 20

decision, summarized his findings regarding withdrawal

and merger by expressing concern over two points, as

follows:

“ (1) The adverse educational impact of the pro

posed withdrawal of Township students from Mor

ristown High School because of the resultant reduc

tion in the total number of students at the high

school and the socio-economic disparities between

Town and Township student bodies; and ^

(2) The long-range harmful effects to the two

school systems—particularly to the black Morris

town students, by the maintenance of two separate

school systems in light of the striking racial imbal

ance between the Town and Township student popu

lations.” (Ja 117).

B. O utline of O ther V /itnesses W ho T estified at H earing

For the convenience of the Court in determining the 40

makeup and scope of the case, the following outlines the

8

1. For the Petitioners:

Edward W. Franey, identified photographs of vari

ous scenes in Morristown and Morris Township

(T10 to 13).

Michael J. Barry, dissenting member of the Morris

Township Board of Education, testified to the

10 Board’s activities and his views and knowledge of

the community (T13 to 89).

2. For the Town

Clive. M. Cputts, realtor, described housing, race

factors and housing market trends in the Town and

Township (T92 to 201).

Isadore Candeub, planning consultant, (See Part A;

supra) (T203 to 298).

20 Dr. Harry W. Wenner* Superintendent of Morris

town Public Schools, testified extensively on the facts

of the educational system, history, and the impli

cations of various changes (T299 to 658).

Richard S. McKinley, educational consultant (See

Part A, supra) (T663 to 926).

Ethel Constance Montgomery, President of the Mor

ristown Board of Education, testified on the Board’s

position, her personal knowledge of the community

trends and implications of separation (T974 to

1058).

Nancy Dusenberry, Secretary of the Morristown

Board of Education, explained some of the financial

aspects of merger and withdrawal (T1902 to 1935).

* Dr. AYeuner’s name was misspelled throughout the transcript,

appearing as “ Werner.”

40

9

3. For M orris P lains

Robert F. Strauss, member of Morris Plains Board

of Education, described his Board’s concern (T926

to 970).

4. For the Tow nship

Sheldon Bennett, Secretary and Business Admin- jn

istrator of Morris Township School Board, de

scribed the history of the relationship, the non

binding referendum and the selection of the pro

posed site for the Township high school (T1074 to

1410).

Roger F. Nicholson, member of Morris Township

Board of Education, testified briefly on his role

(T1410 to 1422).

Richard Cadmus, President of the Morris Town- 20

ship Board of Eduaction, testified on his Board’s

position, the non-binding referendum and the ad

vantages of separation (T1422 to 1449).

Munn Reynolds Dodd, realtor, described housing,

race factors and housing market trends in the

Town and Township (T1453 to 1543).

Dr. Ibrahim Elsammak, city planner and urban re

newal consultant, testified eoncei’ning merits of sites

for a high school (T1544 to 1612).

Dr. Ward Young, Superintendent of Schools in

Morris Township, testified extensively on the facts

of the educational system, history and the impli

cations of various changes (T1615 to 1S74).

Dr. Joseph Clayton, Former Deputy Commissioner

of Education of New Jersey, was asked but not

permitted to interpret the various statutes govern

ing the proposed withdrawal (T1S7S to 1899).

•10

10

20

30

40

1 0

III. Morristown and Morris Township as a single

community.

A, G e o g ra p h ic a n d P h y s ic a l F e a tu re s

Morristown and Morris Township are located in north

ern New Jersey in the southern half of Morris County,

approximately 30 miles west of New York City (Ja 219).

High elevations on the west and southwest outer bound

ary of the Township and swampy lowlands on the east

and south outer boundary tend to isolate the Town and

Township from surrounding communities (Ja 221. 222;

T219 to 222).

Morristown is 2.9 square miles and is encircled by Morris

Township, which has an area of 15.7 square miles (Ja 73;

T32, 255). The combined area of the Town and Town

ship forms one compact territorial base (Ja 258; T252).

I t is less than six miles across the Township between its

two most remote points, five and one-half miles from east

to west and four miles north to south (Ja 233).

As found by the Commissioner, road patterns exert a

strong unifying effect upon Morristown and Morris

Township and underscore their interrelatedness (Ja 81).

All major roads crossing through and serving the Town

ship radiate out from and feed into the Green in the

center of Morristown (Ja 81, 232, 233). The topography

of the area dictated the present road locations and made

circumferential routes within the Township impractical

(Ja 232; T219). I t is generally not practicable to get

from one side of the Township to the other without pass

ing through Morristown (Ja 81, 232; T33, 229, 230).

B. T o w n -T o w n sh ip B o u n d a ry L ine

Morristown and Morris Township began in 1740 as a

single municipality and were not separated until 1865

(Ja 81, 229; T224). The boundary line dividing Morris

town and Morris Township is arbitrary (Ja 81. 229, 263;

10

20

30

40

11

T224, 225, 226). It does not follow physical or natural

features (Ja 81, 263; T225). The street pattern of the

Town and Township has virtually no relation to the

boundary (Ja 81, 229; T224, 225). Only three streets fol

low the boundary, and those for short distances, whereas

some forty streets cross the boundary line, making it im

possible to distinguish Morristown from Morris Town

ship visually (Ja 229, 233; T228, 229). Many of the Mor-

ristown-Morris Township neighborhoods are split by this

boundary line (Ja 263; T155, 225, 226). Land uses con

tinue without interruption from Town to Township, with

the zoning plans of the Town and Township complement

ing each other in disregard of the boundary line (Ja 229,

230; T117, 221, 222, 223).

The boundary line has no significance in relation to the

growth pattern of the Morristown-Morris Township com

munity (Ja 230). lake other communities, this community

grew out from the center and population is progressively

less dense moving from the Morristown Green out into

the Township (T221, 222, 223, 224). "While an aerial pho

tograph distinguishes the Town-Township area from sur

rounding communities, it gives no indication of a bound

ary line between the Town and Township (Ja 264; T228,

229).

C. In te r re la te d n e s s o f th e T o w n a n d T o w n sh ip in G e n e ra l

Morristown serves as the commercial, social, institu

tional, and community center for Morris Township and

Morristown residents (Ja 81, 259, 260; T110, 111, 112,

117, 118). Morristown has extensive retail stores and

commercial establishments centered around its Green,

whereas Morris Township has very few retail outlets of

any type (Ja 230. 231: T110 to 118). The few that are

located within the Township are spotted around on main

roads (Ja 223; T110 to 118). Morris Township has no

business center or “downtown” area (Ja 230; T110, 111,

112, 227). The vast majority of Township residents are

12

not conveniently situated to make use of business areas

outside of Morristown and because of road patterns and

the location of Morristown in the middle of the Town

ship, Morristown’s downtown business area is easily

reached from all sections of the Township and serves as

the “downtown” shopping center for Township, as well

^ as Town residents (Ja 232; T225, 229).

The overwhelming majority of clubs, associations, so

cial service and welfare organizations serving Town and

Township residents, including the YMCA, hospitals,

churches and service clubs, are located in the Town

(Ja 261; T255). As members and users of such organi

zations and their facilities, Town and Township residents

routinely work and play together (Ja 258, 265, 266; T33,

255, 256, 257).

This interaction is particularly strong in the area of

youth and youth facilities. The Morristown Green is a

focal point and meeting place for the youth of Morris

town and Morris Township (Ja 260; T260). Day care

centers in the Town are used by botli Town and Town

ship residents (Ja 268). Park and playground facilities

in the Town and Township are used by both (Ja 268;

T33, 255). For example, Little League baseball and foot

ball involve youth from both Town and Township on the

same teams with fields in botli the Town and Township

being used for the games (Ja 268; T32, 33, 257).*

30

In the field of municipal and public services there are

a number of instances of this interdependency. The Mor

ristown Water Department supplies water to most of the

* The unique interrelatedness of the Town and Township is

depicted in photographs of the recent Memorial Day parade

where the mayors of the Town and Township paraded side by

side, with their governing bodies marching as a single unit and

the police forces of the Town and Township parading as one in

termingled group (Ja 128, 129; T33, 34, 35).40

10

20

30

40

13

Township residents (Ja 267; T256). Sewer service is

rendered to some parts of the Township by the Town.

Town and Township Fire and Police Departments cover

and otherwise assist each other (Ja 270). Morristown

and Morris Township operate jointly the “Joint Free

Public lib rary of Morristown and Morris Township”,

which is located in the Town (Ja 268, 270).

This unusual relationship between Morristown and Mor

ris Township, being historically rooted and physically im

pelled by geographical features, street patterns and other

concrete features, is a durable relationship which, is es

sentially permanent (Ja 269, 270; T263).

D, C o m m unities a n d M u n ic ip a litie s S u rro u n d in g M o rris

T o w n sh ip

In contrast to Morris Township, all of the areas sur

rounding the Township are oriented toward centers other

than Morristown (Ja 257, 25S; T256). These surround

ing areas (including Morris Plains and Harding Town

ship) have identities separate and apart from the Morris-

town-Morris Township community (Ja 257, 258; T256).

(This is treated area by area by Candeub at T256 to 258.)

E. O ne Com m unity Defined

The hearing officer—based upon the testimony and re

port of Candeub, found that Morristown and Morris

Township are one “community” (Ja SO, 81). Part of

Candeub’s testimony and report was devoted to this defi

nition of “community” as a combination of people and

places having the following characteristics:

(1 ) a territorial base, which can be described and de

fined, and which has a recognizable pattern of develop

ment and identifiable characteristics;

10

20

30

40

14

(2) interdependence, interaction and a correspondence

of interests among diversified groups;

(3) a community center or central core of activities

and institutions; and

(4) historical continuity and stability (Ja 253 to 255;

T244 to 247).

As pointed out by Candeub, Morristown and Morris

Township together have all the characteristics of a single

community (Ja 256 to 270; T252 to 263):

(1 ) a compact, common territorial base, which is sepa

rated and distinguishable from surrounding communities

and areas;

(2) a municipal boundary between them which is entirely

arbitrary and invisible, unrelated to any natural or man

made features;

(3) a single common commercial, social and institutional

center which has the Green in downtown Morristown as its

hub;

(4) extensive interaction, interdependence and a mutual

correspondence of interests—in spite of significant socio

economic differences—between Morristown and Morris

Township residents in a broad variety of areas and activi

ties; and

(5) historical continuity and durability in their relation

ship.

Based upon his knowledge and experience, Candeub

found the closeness of this relationship between tvTo sepa

rate municipalities to be unique within New Jersey (Ja

218; T261, 262, 263).

15

IV. Socio-economic and population differences be

tween Morristown and Morris Township.

AVithin this single community, as in any community,

there are notable social and economic variations, and these

correspond significantly with tire inner-outer division.

Morristown and Morris Township present different socio

economic patterns (Ja 77, 79, 218). They have sharp dif

ferences in housing, racial composition of population and

growth of population (Ja 218, 23G). The socio-economic

level of Morris Township residents is significantly higher

than tire level of Morristown and the disparity is increas

ing (Ja 236, 239; T232, 234, 235).

Morristown not only ;.as a large Negro population but

a large percentage of low income and moderate income

white families as well (Ja 239; T159, 235, 236). Morris

town public school officials estimate that 50% to 65% of

its resident students are economically deprived (T449).

Two hundred and seventy-five Town students are receiv

ing ADC support (T356).

Township residents are more likely to be professionals

or businessmen, while many of the Town residents—par

ticularly the Negroes—are blue collar workers (Ja 239;

T160, 232).

A. H ousing

Morristown is nearly fully developed, but the Township

has a large potential for development because of the con

siderable amount of open space still available (Ja 77, 238;

T139). Morristown has intensive business and commercial

development at the center, along with apartment houses

and two-familv homes in its more central residential sec

tions (Ja 78, 2*36; T11S, 142, 143). The density of popula

tion is much greater in the Town than in the Township.

Morristown has approximately the same number of peo

ple living within its 2.9 square miles as the Township has

within its 15.8 square miles (Ja 73, 236).

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

1 6

Single family housing in Morristown ranges in price

from $17,000 to $35,000 with an average sales price of

$22,000 to $24,000 (Ja 78, 238; T120, 121). Single family

housing in Morris Township averages $40,000 to $60,000

and the price of new homes is at least $40,000 (Ja 77, 238;

T100 to 108, 232).

In many areas of Morristown there is a concentration

of old, deteriorating housing, into which Negroes and other

lower socio-economic families are moving—almost exclu

sively on a rental basis—replacing white families and con

verting single family houses into two and three family

units (Ja 78, 236, 237; T126 to 129, 23). Much of this

housing is sub-standard and generally overcrowded (Ja

236; T128).

Unlike Morristown almost the entire Negro population

of Morris Township is concentrated in one residential sec

tion (“Collinsville”) Ja 77, 127; T191, 192). Morristown

has 150 low-income public housing units which are 100%

Negro occupied plus over 100 low-cost public units for the

elderly; Morris Township has none (Ja 78, 236; T143).

There has been little new single family housing con

structed in the Town in recent years (Ja 236; T139). Space

for recent apartment house construction in Morristown has

often been secured by demolishing existing single-family

dwellings (Ja 236; T144, 145). There are. a number of

newer apartments found in the Town which are occupied

predominantly by whites without school-aged children

(Ja 78, 236; T145 to 150).

In contrast to Morristown, a large percentage of Morris

Township’s housing has been constructed within the past

ten years (Ja 23S; T99, 103, 106, 107). Almost all of Mor

ris Township’s recent housing development has been ex

pensive single-family residences (Ja 77, 238; T99, 103, 106,

107, 140). Because of the considerable amount of open

space remaining in tire Township and the demand for ex-

17

pensive single-family houses, the continued construction

of large numbers of such expensive single family dwellings

is expected (Ja 77, 238; T139, 140, 141).

As a result of these differences, Morris Township has

become a site of homes for middle and upper middle in

come families, as contrasted with Morristown, which serves

as the source for housing—public and private—for lower

soeio-ecomonic families, including the elderly and a large

number of Negroes (Ja 77, 78, 236 to 238; T100 to 107,

120 to 128, 139). There is every reason to expect this

housing pattern to continue. There will continue to be a

demand for housing for Negroes in Morristown. Employ

ment opportunities for Negroes in Morris County are in

creasing and there is also the pressure caused by the de

sire of Negroes to move from large concentrations of

Negro populations in nearby cities such as Newark and

New York (Ja 239). The inexpensive housing in Morris- 20

town is relatively more important because of the lack of

available housing for Negroes elsewhere in Morris Coun

ty (Ja 239). New Jersey State Hospital at Greystone

Park employs some 1,000 Negroes, and is only some four

miles from Morristown (Ja 239).

Such blacks coming into the area will continue to be re

stricted by economic factors to locating in the Town, rather

than the Township (Ja 77, 239; T199). Furthermore, the

trend of potential white buyers rejecting the Town as a

place to live (as found by the hearing officer) can be ex- 30

pected to continue and intensify, particularly if the Town

ship withdraws from Morristown High School (Ja 78 79

271, 272, 273; T170 to 173, 1S8, 189, 263 to 265).

B. Population

The sharp differences in housing and housing trends be

tween Morristown and Morris Township have contributed

to and explain the equally sharp differences in the racial

composition and rate of growth of the populations of the 4n

Town and Township. ^

10

20

30

40

18

( 1 ) M orristown Population (Including School Population)

Morristown’s total population is leveling off, but its

Negro population, is increasing at an ever-increasing rate

(Ja 243; T235 to 23S). Morristown bad a population of

15,200 in 1930, 17,200 in 1950 and 17,700 in 1960 (Ja 78,

242, 243). Its population was expected to exceed 20,000

by this time (Ja 242, 243), but the 1970 cent ms shows

17,662. Morristown’s total population is expected to in

crease only by 2,000-4,000 by 1980 (Ja 242, 243).

In 1950 only 10% of Morristown’s population was Negro

(Ja 243; T235). This increased to 14% by 1960 and to

24% by 1968 (Ja 243; T235). By 1980 Morristown will

be between 44% and 48% black, assuming no withdrawal

of Township children from Morristown High School (Ja

78, 243; T237).

Similarly, Morristown’s school population is leveling off,

but its black school population is increasing dramatically

(Ja 171, 173, 24S, 249; T238 to 241). Morristown’s current

resident school enrollment of 2,823 is not expected to ex

ceed 3,200 by 1980; however, its Negro school population is

expected to increase from its current 39% to over 65%

by 1980 (Ja 249; T238). Morristown’s elementary schools

which are now 43% black

by 19S0 (55% black by 1974) (Ja

are expected to be 70%

f0, 24S, 249; T239,

black

241).

The Town black elementary school population is grow

ing at an ever-increasing rate (Ja 171, 173, 248, 249;

T239). It was 33% in 1962 and increased from 39% to

43% from 1968 to 1969 (Ja 75, 171, 173; T333). In 1962-

1963 Morristown in grades K-S had only three classes

over 50% black, whereas in the 1969-1970 school year, the

number had increased to 16 classes (Ja 171. 173; T340).

An even greater rate of increase is most probable in the

event of a withdrawal by the Township from Morristown

High School (Ja 24S, 251, 271 to 273; T 170, 263 to 265).

19

Morristown’s resident high school enrollment is now

30% black, but the overall Morristown High School enroll

ment is only 14% black, because the students received

from Morris Township, Harding and Morris Plains are

predominantly white (Ja 75, 175, 252, 296; T404, 405, 705,

1653). Only 6% of the Morris Township students pres

ently attending Morristown High School are black, and not

over 1% of the Harding Township and Morris Plains stu- 10

dents are black (Ja 175, 252, 2S8, 289, 295, 296, 297).

Morristown no longer has the resources to resolve the

racial imbalance problems now confronting it (Ja 310;

T746, 747). In September, 1962, Morristown voluntarily

undertook a plan of integration to achieve racial bal

ance in its elementary schools (T323, 324, 325, 326). Under

this plan, the Lafayette School, which was overwhelmingly

Negro, was made a junior school for all 7th and Sth grade

pupils and the K -6 pupils formerly attending the school 20

are bussed to the Town’s three other elementary schools

(Ja 73; T324, 325, 326). In spite of this plan, the Lafayette

junior school is now 43% Negro, and the three elementary

schools of the Town 37%, 45% and 49% Negro, respec

tively (Ja 75, 173; T328, 329).

This difference between the racial composition of the

Town’s total population and its school population is at

tributable in part to the fact that the large number of

newer high cost apartments built in the Town are occupied

for the most part by white families without school age 30

children (Ja 78; T146 to 149).

( 2 ) Morris Township Population (Including School Popu

lation )

Morris Township’s total population is increasing rapidly.

I t is overwhelmingly white and will remain so (Ja 127.

243, 246, 247). The Township’s population in 1950 was

7,400. Morris Township’s 1968 population was 17,600

10

20

30

40

20

(Ja 77, 246), and the federal census for 1970 shows 19,-

414. It is anticipated that the Township’s population

will continue to increase and reach 23,500-25,500 by 1974

and 27,500-29,500 by 1980 (Ja 243, 246).

Only 4.5% of the total Township population is black (Ja

245; T236). This represents a decrease in percentage

from 1950. The Township’s Negro population is expected

to decrease slightly by 19S0 and in any event remain less

than 5% of the total Township population (Ja 77, 243,

247; T237).

All of the Negro children who attend Morris Township

public schools—with the exception of three families—live

in the Collinsville section of Morris Township (Ja 127;

T191, 192).

Like its municipal population, Morris Township’s pub

lic school population is now experiencing and will con

tinue to experience growth. Morris Township’s total cur

rent public school enrollment is 4,172 and it is expected

to reach 6,700 by 19S0 (Ja 249, 251). However, the Town

ship’s school enrollment is now and will remain overwhelm

ingly white (Ja 75, 77, 249, 251). Five percent of current

Township students are Negro and no increase in this per

centage is expected (Ja 249, 251; T238). It is more like

ly to decline by 1980 than increase (Ja 77, 249, 251; T239).

The percentage of Negroes in Township schools has de

creased noticeably in recent years as evidenced by the fact

that in 1946 the Township’s ninth grade class graduating

from Alfred Vail Junior High School was 22% Negro

(T979, 980).

21

V. The present Morristown-Morris Township school

systems.

A. In G eneral

Both the Morristown and Morris Township school sys

tems are of high quality (Ja 72, 294, 295; T341 to .353,

593, 1355, 1428). Morristown is rated as one of the top

two school districts in Morris County and also ranks high

among the superior school districts of New Jersey as

revealed by the “Pilot Study of School District Reor

ganization for the State of New Jersey” made by Engel-

hardt, Engelhardt and Leggett, Inc. (now Engelhardt and

Engelhardt, Inc.) in January, 1968 for the State Depart

ment of Education in connection with the work of the

“Mancuso” Committee (Ja 193, 194, 294; T349, 350).

By all accepted standards of measurement, Morristown

maintains an excellent educational program, both at the

high school and elementary levels (Ja 72, 83, 294, 295; T341

through 353).

10

20

Morristown High School rates high among the superior

schools of the state and offers a diversified and compre

hensive program, including seven full vocational programs

and an equal number of advanced college placement

courses in English, social studies, science and language

(Ja 72, 294, 295; T367, 368, 369). Morristown High School

currently offers a total of 150 courses (T367). The me

dian superior school district in New Jersey offers 90-99 30

courses at the high school level, and the State median is

only 80-89 courses (Ja 295). Morristown High School

has been singled out for a number of pilot state and

federal programs including vocational guidance, television

and food services (T374, 375).

During the years 1966, 1967, 1968 and 1969, approximate

ly 70% of Morristown High School graduates enrolled in

4-year, 2-vear or technical schools following graduation

(Ja 181, 302). Total figures for these four years show that 49

10

20

30

40

22

while 76% of Township graduates went on to further

schooling, only 59% of Town graduates did so (.Ja 181,

302).

Morristown High School's current enrollment is approx

imately 2,000 which compares favorably with the size of

schools in the group of superior school districts studied

iii connection vv'ith the work of the Maneuso Committee

(Ja 294, 295). Morristown High School’s comprehensive

program has been educationally and financially feasible

because of the size of its total enrollment (Ja 82, S3,

300, 301, 303; T371 to 373).

Morristown had a total resident school population on

May 1, 1969, of 2,823, including 785 9th-12th grade stu

dents in Morristown High School (Ja 285). Morristown

has three K -6 elementary schools (George Washington,

Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson), and in ad

dition it houses six kindergarten classes in rented space

in the Assumption School and two kindergarten classes

in a “child development center” building (Ja 281, 284).

Morristown’s 7th and 8th grade students are housed in

the Lafayette School (Ja 73, 284; T675). These build

ings as well as the high school, are well maintained, but,

with the exception-of Thomas Jefferson, are older than

those in Morris Township and located on smaller sites

(Ja 283).

Morris Township’s total resident school population as

of May 1, 1969 was 4,172 (Ja 74, 285), including 750

10th, 11th and 12th grade students sent to Morristown High

School (Ja 282). Morris Township bus five K-6 elemen

tary school buildings (Woodland Avenue, Normandy Park,

Alfred Vail, IJillcrest and Sussex Avenue), and the Fre-

Iinghuysen Junior School which houses its 7th, 8th and

9th grades (Ja 73, 74, 75, 284). The five Township ele

mentary schools are located in close proximity to the

Town-Township boundary line and the Town schools,

which also (with one exception) lie near such boundary

line (Ja 73, 74, 250; T239 to 241).

23

Apart from the sending-receiving relationship at the

high school level, the Morristown and Morris Township

school districts have various joint educational programs

and cooperative efforts (Ja 283; T316 to 321, 675, 676).

-Along with Morris Plains and Harding, Morristown and

Morris Township sponsor a single special education pro

gram for their trainable, educable, physically handicapped,

emotionally disturbed and socially maladjusted students,

with the large majority of such students attending classes

in either Morristown or Morris Township schools (Ja

283; T317, 675, 676). Morristown and Morris Township

have for several years jointly conducted summer remedial

reading and math programs as well as in-service training

for their staffs (T319, 320).

B. E x is tin g S en d in g -R ece iv in g R e la tio n sh ip s

1. M orris Plains and H arding Tow nship

Morristown also accepts 9-12 grade students from Mor

ris Plains and Harding Township (Ja 72, 281, 282). The

Morristown High School enrollment as of 5/1/69 totalled

1,976 as follows:

Town Grades Enrollment Percent

Morris Plains 9-12 336 17

Harding 9-12 105 5

Morris Township 10-12 750 38

Morristown 9-12 7S5 40

Total: 1976

(Ja 282)

Neither Morris Plains nor Harding currently is under

contract with Morristown to send its pupils to Morris

town High School (Ja 72; T321). These sending-receiv

ing relationships are based only on designations, and

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

24

they are tenuous if the Commissioner persists in saying

he cannot control withdrawal (Ja 82; T321, 322, 323, 977,

978). Both the Harding and the Morris Plains Boards

have considered alternatives to sending their high school

pupils to Morristown High School (T322, 323). Morris

Plains will seriously consider other alternatives and ex

plore a relationship with other contiguous districts, in

cluding entry into a contiguous regional district, in the

event Morris Township withdraws from Morristown High

School (T941, 942).

Unlike Morris Township, the number of resident high

school pupils (9th-12th gx-ade) from Harding and Mor

ris Plains is expected to increase by only some 100 stu

dents by 1980 (Ja 286). These high school populations

will remain less than 1% black (Ja 252).

2 . M orristown and Morris Township

This sending-receiving relationship whereby Morris

Township currently sends its 10th, 11th and 12tli

grade students to Morristown High School pre-dates

the present 10-year contract and has been a con

tinuous one since 1870 (Ja 71, 72; T304, 305, 306, 307,

1084). Dui'ing this long relationship, the only Morris

Township high school students failing to attend and

graduate from Morristown High School were those in

the Township 10th grade classes of 1958 and 1959. These

two classes attended and graduated from Madison High

School. Even during this period, therefore, at least one

class of Morris Township students was attending Morris

town High School (Ja 71; T305, 306).

In 1959 and again in 1960, the voters of Morris Town

ship defeated a referendum which, if approved, would

have permitted the Township Board of Education to con-

struct its own high school (T308, 309). In between these

two Township high school referendums, the Boards of

Education of Morristown and Morris Township jointly

25

sponsored a referendum proposing a complete K-12 mer

ger of both districts (Ja 185; T308, 309). The voters of

Morristown approved, but Morris Township voters re

jected merger (T308, 309).

On March 15, 1961, Morristown and Morris Township

entered into the present 10 year contract whereby Mor

ris Township agreed to send its 1.0th grade students

to, and have them educated through 12th grade, at Mor

ristown High School for the 10 year period specified

(Ja 71, 161; T306, 309). The last 10th grade class cov

ered is the one which will enter in September, 1971 and

graduate in June, 1974 (Ja 71, 72; T306).

C. Sufficiency o f F ac ilitie s

Total school population projections for Morristown and

Morris Township show the school facility needs of the

Township to be more acute and extensive than are the

needs of the Town (Ja 74, 2S4, 285, 287; T686 to 690).

The present capacity of Morristown High School is

adequate to accommodate all high school students from

Morristown, Morris Township, Morris Plains and Hard

ing through 1974 without exceeding an average of 25

pupils per class (Ja 74, 305; T382 to 386). Morristown’s

elementary facilities are currently at capacity, but its K-6

enrollment is expected to increase only by 200 pupils by

1980 (Ja 284, 285). Morristown’s junior high school has

sufficient capacity to accommodate all its 7th and 8th

grade pupils through 1980 (Ja 284, 285). Morris Town

ship reports that its elementary schools (K-6) are some

200 below capacity as of May 1, 1969 (Ja 284). Morris

Township’s K -6 enrollment will increase by 1.000 pupils

by 1974 and by 1,500 pupils by 19S0 (Ja 285).

Morris Township’s Junior School (Frelinghuysen) is

said to have already exceeded its capacity by some 200

pupils (Ja 2S4). Morris Township’s 7th and 8th grade pop

ulation will increase over 200 pupils by 1974 and by 1,000

.10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

26

pupils by 19S0 while Morris Township’s 9th-12th grade

population will increase from 1,021 to 1,500 by 1974 and to

1,760 by 19S0 (Ja 285).

VI. Morris Township’s non-binding referendum

On January 11, 1968, the Morris Township Board of

Education conducted a “non-binding” special referendum

among only Morris Township residents (Ja 85; T25,

11S9). The issue as presented on the ballot asked the

Township voter to indicate whether he favored a sep

arate K-12 school system for Morris Township, or a com

plete K-12 merger with Morristown (Ja 85, 159; T25).

The Morris Township Board of Education agreed to

hold this referendum although six out of eight members

of the Board favored a complete K-12 merger (Ja 85;

T25 to 27, 11S9, 3190, 1345, 1346). Although referred to

as a “non-binding” referendum, the Morris Township

Board pledged itself to be bound by the decision of the

voters and has acted and regarded itself as bound since

the referendum (Ja 85, 159, 195; T29). By a narrow mar

gin, the Township voters favored a separate K-12 dis

trict; the referendum vote was 2,164 to 1,899 in favor of

a separate high school and against merger (Ja 85, T29).

In regard to this referendum the Township residents

were given no information concerning capital cost savings

lo Township taxpayers in view of the anticipated rapid

increase in Township enrollment, if there were a merger

(Ja 75; T1435 to 1439). As pointed out by the hearing

officer, under a merged system the Town would bear about

40% of the cost of providing facilities required by the in

creasing Township population for Township students (Ja

75).

Immediately following this referendum, the Morris

Township Board of Education launched into its program

for the planning and construction of a separate Town-

27

ship high school (Ja 85; T31, 32, 1349). A bond referen

dum seeking approval of the Township voters to incur

indebtedness of $7,9SO,000 in connection with the construc

tion of such high school was scheduled for March, 1969,

but was enjoined by the Commissioner’s preliminary de

cision of March 21, 1969 (Ja 55 to 66; T35). Since the

January 11, 1968 referendum, the Morris Township Board

of Education has not considered any course of action 10

ether than erecting its own separate high school (Ja 85,

86, 195; T31).

In addition Morris Township refused to take part in

the merger study conducted by Dr. Leslie Rear, Morris

County Superintendent of Schools, pursuant to the urgent

request of the Commissioner of Education, made as part

of his preliminary decision of March 21, 1969 (Ja 65, 66,

86, 131, 133; T31, 32).

20' The Commissioner ruled that this January 11, 1968 ref-

erendum was illegal and an improper abdication of the

Township Board’s responsibility (Ja 113).

VII. Impact of withdrawal of Morris Township

A. Com m issioner’s G eneral Findings

The Commissioner found that the proposed withdrawal

of some 800 overwhelmingly white Morris Township stu

dents from Morristown High School would have an adverse

educational impact upon high school students from both 30

Morristown and Morris Township (Ja 117). This con

clusion Avas supported by the folloAving specific findings of

the hearing officer regarding the educational disadvantages

of withdrawal, summarized as folloAvs (Ja 82, S3):

1 . Scope and variety of courses offered at Morristown

High School would have to be reduced;

2. Withdrawal of the highly motivated, capable Town

ship students Avould have an adverse effect upon

40

23

10

20

30

the performance and motivation of the remaining

students;

3. The program structure would have to be drastically

re-oriented for the remaining students from lower

socio-economic backgrounds;

4. The percentage of black students in the High School

would immediately double from 14% to 28% (to 44%

without Harding and Morris Plains) and by 1980

would reach 35% (56% without Harding and Morris

Plains);

5. The present excellent program at Morristown High

School would lose its breadth and quality;

6. With change in program and reputation and loss

in tuition revenue, it is likely there will be a de

crease in the Town’s financial support of its school

system;

7. Morristown would have difficulty keeping and at

tracting the same high quality faculty;

8. Township high school students would be denied the

privilege of an integrated education;

9. The sudden alteration in racial composition of the

High School is likely to aggravate the tendency of

potential white buyers to avoid purchasing houses in

Morristown.*

* Immediately following these nine findings the hearing officer

makes an observation which requires mention. He says:

“ However, even accepting petitioners’ enrollment projec

tions, no conclusive testimony was introduced to establish

that, as a result of the withdrawal of the township students,

the remaining black Morristown High School students

would necessarily experience a sense of stigma or be sub

ject to a stamp of inferiority.”

( C o n t i n u e d or, f o l l o w i n g p a g e )40

29

B. U nderlying Proofs

I . Racial Imbalance

Racial imbalance and racial segregation at the high

school level would result if 'Morris Township were per

mitted to withdraw and erect its own high school (Ja 82,

295, 297). This results from the fact that Morristown’s

resident black high school population is increasing rapid

ly, while Morris Township’s school population will con

tinue its rapid growth, but remain overwhelmingly white

(Ja 248, 249, 251). Morristown High School’s current en

rollment of some 2,000 students is only 14% black be-

( C o n t i n u e d f r o m p r e c e d i n g p a g e )

While this is not structured as a specific finding it warrants men

tion because it is not only palpably in error on the record, but

directly contradicted by the hearing officer’s specific findings,

which establish that the image and reputation of Morristown High

School will suffer substantially. Thus, he found in item 7 that

high quality faculty candidates would tend not to come to Morris

town; in item 6 he found that Morristown High School’s “ reputa

tion” will change—obviously adversely; and in item 9 he found

that home buyers may reject Morristown increasingly because of

this sudden alteration of the racial composition of the high school.

This is a finding of stigma by another name—deterioration of

reputation and image. The hearing officer’s quoted sentence, in

light of this, does not seem to have been carefully considered.

If it was intended to differentiate between the obvious harm to

Morristown’s black students and outsiders’ perception of it, as

against the black students’ perception of it, it is without founda

tion.

We suggest the hearing officer’s itemized findings are controlling,

and that the quoted sentence was a casual commentary which was

not intended to contradict the findings, and if it were so intended

would be unsubstantiated in the record.

On the compelling evidence of a branding of Morristown High

School as inferior, see, e.g., the testimony of Dr. Wenner (T441-

442) the Candeub report (Ja 271-273) and the Engelhardt report

(Ja 304a).

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

30

cause the students received from Morris Township, Hard

ing and Morris Plains are overwhelmingly white (.Ja 75,

l<o, 252, 296; T404, 405, 705, 1653). Morristown’s resi

dent high school population, however, is 30% black, while

only 0% of the 762 10th-12th grade students received from

Morris Township are black and not over 1 % of the Hard

ing and Morris Plains students are black (Ja 75, 175

252, 288, 289, 295, 296, 297). These Township students’

constitute approximately 45% of the total 10th, 11th and

12th grade students at Morristown High School, and would

total well over 50% of such grades bv 1974 (Ja 24S to

251; T425).

In contrast to the sharp increase in the black popula

tion at Morristown High School which would be produced

by the Township’s withdrawal, the new Township high

school, along with the rest of the Township district, would

be overwhelmingly white (95%) (Ja 76, 77, 249, 251, 297).

When the large Negro elementary school population of the

Town is also considered (now 43% Negro and expected

to be 70% Negro by 1980), the result is a predominantly

black school district surrounded by an overwhelmingly

white one (Ja 75, 76, 77, 82, 83, 84, 310, 3.11).

Morris Township’s high school students would be de

nied the bi-racial experience which is now available to

them at Morri&town High School, and which is represen

tative of the bi-racial Morristown community in which

they live (Ja 272, 273, 311). The result would be “disas

trous” insofar as relationships, among the youth of the

community and the community as a whole is concerned

(T434). Candeub testified that withdrawal would be an

“extraordinarily regressive step which frankly shocks me.”

(T265). The opportunity of both Town and Township

students to prepare for the future in a social climate con

ducive to developing healthy relationships among whites

and blacks would be lost (Ja 311; T263, 264, 265, 435)

This unfavorable contrast between Morristown’ High

31

School and the new Township high school in terms of