Douglas v. Southern California Independent Living Center Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 1, 2011

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Douglas v. Southern California Independent Living Center Brief Amici Curiae, 2011. 58e7161f-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/189a958c-a63e-4cf7-a96e-c71e95b4b257/douglas-v-southern-california-independent-living-center-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

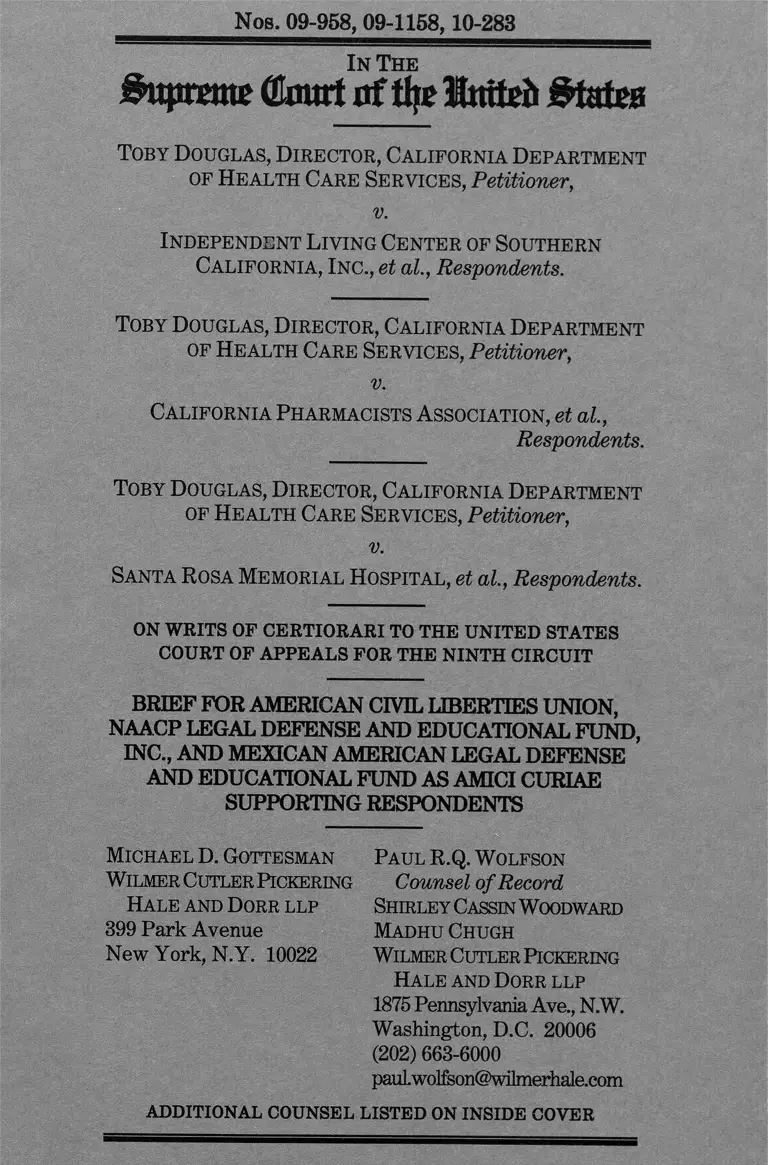

Nos. 09-958, 09-1158,10-288

In The

#uprajtt (four! af tip Itttteii &fettos

T o b y D o u g l a s , D i r e c t o r , C a l i f o r n i a D e p a r t m e n t

o f H e a l t h C a r e Se r v i c e s , Petitioner,

v.

I n d e p e n d e n t L i v in g C e n t e r o f S o u t h e r n

C a l i f o r n i a , I n c ., et al., Respondents.

T o b y D o u g l a s , D ir e c t o r , C a l i f o r n i a D e p a r t m e n t

o f H e a l t h C a r e S e r v i c e s , Petitioner,

v.

C a l i f o r n i a P h a r m a c is t s A s s o c ia t io n , et al.,

Respondents.

T o b y D o u g l a s , D ir e c t o r , C a l i f o r n i a D e p a r t m e n t

o f H e a l t h C a r e S e r v i c e s , Petitioner,

v.

Sa n t a R o s a M e m o r ia l H o s p it a l , et al., Respondents.

on writs of certiorari to the united states

court of appeals for the ninth circuit

BRIEF FOR AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC., AND MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICI CURIAE

SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS

M ic h a e l D. G o t t e s m a n P a u l R .Q . W o lfso n

W ilm er C u tle r P ickerin g Counsel o f Record

H a l e a n d D o r r l l p Sh ir l e y Cassin W oodw ard

399 Park Avenue M a d h u C h u g h

New York, N.Y. 10022 W ilm er C u tle r P ickering

H a l e a n d D o r r l l p

1875 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 663-6000

pauLwolfeon@wilmerhale.com

additional counsel listed on inside cover

mailto:pauLwolfeon@wilmerhale.com

St e v e n R . Sh a p ir o

A m e r ic a n C iv il L iberties

F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, N Y 10025

V ic t o r V ir a m o n t e s

M e x ic a n A m e r ic a n

L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d

634 S. Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

J ohn P a y t o n

D ir e c t o r -C o u n sel

NAACP L eg al D efen se a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, N Y 10013

J o sh u a C iv in

NAACP L egal D efen se a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

14441 Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................ iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE..................................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................... 2

ARGUMENT................................................................... 4

I. T h e C o u r t s ’ L o n g s t a n d in g A u t h o r it y

To E n f o r c e T h e C o n s t it u t io n

T h r o u g h D i r e c t A c t io n s H a s B e e n

P a r t i c u l a r l y C r i t ic a l F o r C i v il

R ig h t s A n d C i v i l L i b e r t i e s .................................4

A. Civil Rights Claims Have Long Been

Enforceable Through Direct Actions................ 5

B. Constitutional Claims Outside The

Civil Rights Context Have Also Long

Been Enforceable Through Direct Ac

tions.....................................................................11

C. The Supremacy Clause As Well May

Be Enforced Through Direct Equitable

Actions................................................................14

II. P r e c l u d in g D ir e c t R ig h t s O f A c t io n

U n d e r T h e S u p r e m a c y C l a u s e W o u l d

H a v e B r o a d A n d H a r m f u l C o n s e

q u e n c e s F o r M a i n t a i n i n g T h e S u

p r e m a c y O f F e d e r a l L a w .................................. 22

A. Minorities, Immigrants, and Low-

Income Individuals Continue To De

pend On Direct Actions Under The Su

premacy Clause To Challenge Invalid

State And Local Laws...................................... 23

Page

11

Page

B. Precluding Rights Of Action Under

The Supremacy Clause Would Under

mine Important Federal Interests................. 26

CONCLUSION.............................................................. 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Allen v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co.,

114 U.S.311 (1884).................................................. 12

Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus,

438 U.S. 234(1978).................................................. 12

Arka?isas Department o f Health & Human

Services v. Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268 (2006)....15,16, 29

Asakura v. City o f Seattle, 265 U.S. 332 (1924)...........16

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946).................................... 9

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents o f Fed

eral Bureau o f Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388

(1971)......................................................................... 10

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)................... 2, 6, 7

Bond v. United States, 131 S. Ct. 2355 (2011)..........5,14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954)........................................................................... 7

Buquer v. City o f Indianapolis, No. ll-ev-708,

2011 WL 2532935 (S.D. Ind. June 24, 2011)........... 24

Camion v. University o f Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

(1979)......................................................................... 28

Carlson v. Gr'een, 446 U.S. 14 (1980).............................10

Chamber o f Commerce v. Edmundson,

594 F.3d 742 (10th Cir. 2010).................................. 23

Chamber o f Commerce v. Whiting, 131 S. Ct.

1968 (2011)................................................................ 23

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940)...................... 6

Page(s)

IV

Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v.

City of Chicago, 166 U.S. 226 (1897)...................... 12

Comacho v. Texas Workforce Commission,

408 F.3d 229 (5th Cir. 2005).....................................25

Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko,

534 U.S. 61 (2001)..................................................... 10

Crosby v. City of Gastonia, 635 F.3d 634 (4th

Cir. 2011).... 12

Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council,

530 U.S. 363 (2000)................................16,18,20

Cuomo v. Clearing House Ass’n, L.L.C., 129 S.

Ct. 2710 (2009)........................................................... 16

Dennis v. Higgins, 498 U.S. 439 (1991)........................ 12

District o f Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973)........................................................................... 6

Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908)............... 12,13,15

Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v.

Paul, 373 U.S. 132 (1963).........................................16

Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67 (1997).................................16

Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Account

ing Oversight Board, 130 S. Ct. 3138 (2010)...........14

Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights v.

Deal, No. ll-cv-1804, 2011 WL 2520752

(N.D. Ga. June 27,2011).......................................... 24

Golden State Transit Corp. v. City o f Los An

geles, 493 U.S. 103 (1989).............

Green v. Mansour, 474 U.S. 64 (1985)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page(s)

17

13

V

Page(s)

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)................8

Hays v. Port o f Seattle, 251 U.S. 233 (1920).................12

Haywood v. Drown, 129 S. Ct. 2108 (2009).................. 21

Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52 (1941)...........16, 20, 30

Howlett ex rel. Howlett v. Rose, 496 U.S. 356

(1990)......................................................................... 21

Kemp v. Chicago Housing Authority, No. 10-

cv-3347, 2010 WL 2927417 (N.D. 111. July

21,2010)..............................................................24, 25

Lankford v. Sherman, 451 F.3d 496 (8th Cir.

2006)....................................................... 25

League o f United Latin American Citizens v.

Wilson, 997 F. Supp. 1244 (C.D. Cal. 1997)........... 24

Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly, 533 U.S. 525

(2001)......................................................................... 16

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980)........................... 16

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137

(1803)....................................................................... 4,5

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for

Higher Education, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).................... 7

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)...............................6

New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144 (1992)...........14

Osborn v. Bank o f U?iited States, 22 U.S.

(9 Wheat.) 738(1824).......................................... 11,15

Patsy v. Board of Regents of Florida, 457 U.S.

496(1982)................. ......................................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

20

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page(s)

Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers

of America v. Walsh, 538 U.S. 644

(2003)....................................................... 15,16,19,26

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925).........2, 9

Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997)................14

Raich v. Truax, 219 F. 273 (D. Ariz. 1915).................. 11

Rowe v. New Hampshire Motor Transport

Ass’n, 552 U.S. 364 (2008).......................................16

Scott v. Donald, 165 U.S. 107 (1897)............................. 12

Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85

(1983)..........................................................................16

Society of Sisters v. Pierce, 296 F. 928 (D. Or.

1924)............................................................................ 9

South Carolina v. Baker, 485 U.S. 505 (1988)..............14

South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987)................... 14

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197 (1923)................. 8, 9

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953).......................... 2, 8

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947)..................................21

Toll v. Moreno, 458 U.S. 1 (1982)...................................30

Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915)............................. 2, 8

United States v. City o f Philadelphia, 644 F.2d

187 (3d Cir. 1980)......................................................29

United States v. Locke, 529 U.S. 89 (2000).................... 16

Vicksburg Waterworks Co. v. Mayor & Aider-

men of Vicksburg, 185 U.S. 65 (1902)...............12, 21

Vll

Villas at Parkside Partners v. City o f Farmers

Branch, 496 F. Supp. 2d 757 (N.D. Tex.

2007) ........................................................................ 24

Villas at Parkside Partners v. City o f Farmers

Branch, 577 F. Supp. 2d 858 (N.D. Tex.

2008) ........................................................................ 24

Watters v. Wachovia Bank, N.A., 550 U.S. 1

(2007)......................................................................... 16

Webster v. Doe, 486 U.S. 592 (1988)..................................5

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

343 U.S. 579 (1952)................................................... 14

DOCKETED CASES

Complaint, United States v. Alabama, 11-cv-

02746 (N.D. Ala. Aug. 1, 2011)................................18

Complaint, United States v. Arizona, 10-cv-

01413 (D. Ariz. July 6, 2010)..........................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page(s)

18

vm

Page(s)

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

U.S. Const.

art. I, §8, cl. 1..........................................15,22,23,26

art. I, §8, cl. 3..................................... 3,12,13,19,20

art. I, §10, cl. 1........................................ 2,11,12,19

art. II, § 2, cl. 2 ........................................................ 14

art. I l l ....................................................................... 29

art. VI, cl. 2.......................................................passim

amend. 1.....................................................................19

amend. V ......................................................................6

amend. X I .................................................................. 13

amend. X IV ............................... 8, 9,11,12,13,19, 29

amend. X V .............................................................8,19

42 U.S.C. § 1983......................................................passim

Act of Dec. 29, 1979, Pub. L. No. 96-170,

93 Stat. 1284................................................................6

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bandes, Susan, Reinventing Bivens: The Self-

Executing Constitution, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev.

289 (1995).....................................................................7

Berzon, Honorable Marsha S., Securing Fragile

Foundations: Affirmative Constitutional

Adjudication in Federal Courts, 84 N.Y.U.

L. Rev. 681 (2009).......................................................7

Blac-kmun, Harry A., Section 1983 and Federal

Protection o f Individual Rights— Will the

Statute Remain Alive or Fade Away?,

60 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1 (1985)....................................... 7

IX

The Federalist Papers

No. 33 (Hamilton)..................................................... 14

No. 78 (Hamilton)....................................................... 5

Hart & Wechsler’s The Federal Courts & The

Federal Syste?n (Fallon, Richard H. et al.

eds., 6th ed. 2009)..................................................... 16

Hills, Roderick M., Dissecting the State: The

Use of Federal Law to Free State and Lo

cal Officials from State Legislatures’ Con

trol, 97 Mich. L. Rev. 1201 (1999)............................28

Key, Lisa E., Private Enforcement of Federal

Funding Conditions Under § 1983: The

Supreme Court’s Failure to Adhere to the

Doctrine o f Separation o f Powers, 29 U.C.

Davis L. Rev. 283 (1996).......................................... 27

Mank, Bradford C., Suing Under § 1983: The

Future After Gonzaga University v. Doe,

39 Hous. L. Rev. 1417 (2003)................................... 27

Perkins, Jane, Medicaid: Past Successes and

Future Challenges, 12 Health Matrix 7

(2002).........................................................................27

Sloss, David, Constitutional Remedies For

Statutory Actiofis, 89 Iowa L. Rev. 355

(2004).............................................................16, 20, 29

Smolla, Rodney A., Federal Civil Rights Acts

(3d ed. 2011)................................................................ 7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page(s)

X

Page(s)

Stephenson, Matthew C., Public Regulation o f

Private Enforcement: The Case for E x

panding the Role o f Administrative Agen

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

cies, 91 Va. L. Rev. 93 (2005)..................................29

Wright, Charles Alan et ah, Federal Practice

and Procedure (3d ed. 2008)...................................13

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

The American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with

over 500,000 members, dedicated to the principles of

liberty and equality embodied in the Constitution and

our nation’s civil rights laws. Founded in 1920, the

ACLU has vigorously defended civil liberties for over

ninety years, working daily in courts, legislatures and

communities to defend and preserve the individual

rights and liberties that the Constitution and laws of

the United States guarantee everyone in this country.

The ACLU has appeared before this Court in numer

ous civil rights cases, both as direct counsel and as

amicus curiae.

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc. (“LDF”) is a non-profit legal organization estab

lished to assist African Americans and other people of

color in securing their civil and constitutional rights.

For more than six decades, LDF attorneys have repre

sented parties and appeared as amicus curiae in litiga

tion before the Supreme Court and other federal courts

on matters of race discrimination, including through the

type of direct constitutional enforcement actions at is

sue in this case.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educa

tion Fund (“MALDEF”) is a national civil rights or

ganization established in 1968. Its principal objective is

The parties have consented to the filing of this brief. Pursu

ant to Rule 37.3(a), written consents to the filing of this brief are

on file with the Clerk of the Court. No counsel for a party au

thored this brief in whole or in part, and no person, other than the

amici curiae, their members, or their counsel made any monetary

contribution to the preparation or submission of this brief.

2

to promote the civil rights of Latinos living in the

United States through litigation, advocacy and educa

tion. MALDEF has represented Latino and minority

interests in civil rights cases in the federal courts

throughout the nation, including the Supreme Court.

MALDEF’s mission includes a commitment to protect

the rights of immigrant Latinos in the United States,

and MALDEF has asserted preemption theories in

federal court to further this commitment.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Enforcement of the Constitution is not depend

ent on affirmative action by the political branches of

government. Rather, from this Nation’s earliest times

to the present, the federal courts have consistently ex

ercised their equitable powers to compel compliance

with the Constitution, without suggesting the necessity

for a statutory vehicle, such as 42 U.S.C. § 1983, for

such authority. Those equitable powers have been, and

continue to be, particularly important for minorities,

immigrants, low-income individuals, and others whom

our majoritarian political processes are often unwilling

or unable to protect against constitutional violations.

Indeed, direct actions brought to enforce compliance

with the Constitution have resulted in many of this

Court’s most important civil-rights and civil-liberties

decisions, including Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1954), Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953), Truax v.

Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915), and Pierce v. Society o f Sis

ters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925); in none of those cases did the

Court suggest that it was acting under § 1983 or an

other statutory vehicle. That history is consistent with

the many cases in which this Court enforced other pro

visions of the Constitution, such as the Contracts

Clause and Commerce Clause, as well as structural

principles of federalism and separation of powers.

3

Such direct actions are also available to enforce a

claim of preemption under the Supremacy Clause, see

U.S. Cert. Amicus Br. 15-18, including where the pre

emption is based on a statute enacted under Congress’s

spending power. This Court has entertained and sus

tained many preemption claims in that context, recog

nizing the appropriateness of direct actions to vindicate

the supremacy of federal law. Petitioner suggests that

such direct actions should not be allowed, or drastically

restricted to narrow contexts, but that rule would seri

ously undermine federal law. In many contexts, a di

rect action is the only way in which the supremacy of

federal law could be established. Requiring litigants

asserting a Supremacy Clause claim to wait for a state-

court action would be grossly inefficient and could re

sult in federal law being undermined by invalid state

laws.

II. Direct actions remain critical to vindicate the

supremacy of federal law. This is especially true for

racial minorities, immigrants, and low-income individu

als, who in many circumstances have difficulty obtain

ing access to, or support from, the federal political

branches, and who often depend on a judicial remedy to

prevent enforcement of state laws that conflict with

federal laws. In contexts as diverse as immigration,

housing, and public assistance, direct actions remain

the only effective avenue to ensure the supremacy of

federal law. Eliminating that avenue would seriously

undermine federal law, because other avenues of en

forcement of federal law—such as termination of fed

eral funding or enforcement actions brought by the

United States—are highly impractical and offer little or

no hope for successful enforcement on behalf of indi

viduals directly harmed by states’ illegal conduct. Ab

sent direct actions brought to establish the supremacy

4

of federal law by those most directly affected by pre

empted state laws, there could well be no meaningful

remedy for state noncompliance with the Constitution’s

fundamental safeguards.

ARGUMENT

I. T h e C o u r t s ’ Lo n g s t a n d in g A u t h o r it y T o E n

f o r c e T h e C o n s titu tio n T h r o u g h D ir e c t A ctio n s

H a s B e e n P a r tic u l a r l y C r itic a l F o r C ivil R ig h ts

A n d C ivil L ib e r t ie s

This Court has long recognized that the strictures

of the Constitution may be enforced through direct ac

tions for equitable relief, regardless whether Congress

has enacted legislation specifically establishing a cause

of action for such relief. So long as the court has sub

ject-matter jurisdiction over the claim, separate legisla

tion establishing a cause of action has never been nec

essary for a plaintiff to obtain forward-looking relief

from unconstitutional conduct. Rather, the traditional

equitable authority of the courts has always been

deemed sufficient to provide such a remedy. The Court

has adhered to this principle in many contexts—

whether the constitutional claim was brought against

federal, state, or local officials; whether the claim was

brought to enforce individual constitutional rights or to

enforce structural principles in the Constitution; and

whether or not the claim was brought to preclude an

anticipated enforcement action.

The courts’ inherent equitable authority to compel

compliance with the Constitution is implicit in the

structure of the Constitution itself, and in the Constitu

tion’s status as the supreme law of the land. See Santa

Rosa Br. 13-18. As the Court recognized in Marbury v.

Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), judicial review is

necessary as a check against the aggrandizement of

5

power by the political branches. These structural prin

ciples not only protect each branch from intrusion by

the others, but they also protect individuals from the

abuse of governmental power. See Bond v. United

States, 131 S. Ct. 2355,2363-2364 (2011). Thus, as Chief

Justice Marshall explained, “ [t]he very essence of civil

liberty” is “the right of every individual to claim the

protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury.”

5 U.S. (1 Cranch) at 163. Although legislation may

channel the way in which constitutional claims are en

tertained by the courts, the courts have long under

stood that the right to compel compliance with the Con

stitution is not contingent on the assent of the political

branches. See Webster v. Doe, 486 U.S. 592, 603 (1988)

(stressing that a ‘“serious constitutional question”’

would arise if the political branches attempted to pre

clude any judicial forum for constitutional claims by

failing to make statutory allowance for such claims); see

also Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton) (“[T]he courts were

designed to be an intermediate body between the peo

ple and the legislature, in order ... to keep the latter

within the limits assigned to their authority.”).

A. Civil Rights Claims Have Long Been Enforce

able Through Direct Actions

The ability to enforce rights directly under the

Constitution has been particularly important for mi

norities, immigrants, low-income individuals, and other

persons who have faced systemic barriers in our ma-

joritarian political process and thus have often de

pended on the federal courts to secure their rights

when Congress and the Executive Branch have been

6

unable or unwilling to do so.2 Some of this Court’s (and

this country’s) most significant steps toward achieving

equality and liberty have resulted from plaintiffs’ en

forcement of their rights directly under the Constitu

tion. And that was particularly true in the long period

before this Court’s decision in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

167 (1961), revived 42 U.S.C. § 1983 as a vehicle for en

forcement of constitutional rights.

Many landmark civil rights decisions resulted from

direct actions to enforce the Constitution. One such

case, Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), is a key

stone of this Court’s desegregation precedent. The

Bolling plaintiffs challenged racial segregation in the

public schools of the District of Columbia under the

Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. The

Court ruled unanimously for the plaintiffs, holding that

racial segregation in the District’s public schools vio

lated the Fifth Amendment. The Court nowhere sug

gested that the plaintiffs’ ability to be heard on their

due process claim depended on their being able to point

to a statutory cause of action, such as § 1983.3

2 See Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 241 (1940) (“Under

our constitutional system, courts stand against any winds that

blow as havens of refuge for those who might otherwise suffer be

cause they are helpless, weak, outnumbered, or because they are

non-conforming victims of prejudice and public excitement.”).

3 Indeed, at the time, it was an open question whether § 1983

applied to the District of Columbia. The Court did not address the

question until District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973),

which held that § 1983 did not apply to persons acting under color

of D.C. law. Congress later amended § 1983 to apply to such per

sons. Act of Dec. 29,1979, Pub. L. No. 96-170, § 1, 93 Stat. 1284.

7

Desegregation in higher education was advanced

through another direct constitutional action, McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Educ., 339 U.S.

637 (1950). After the University of Oklahoma denied

the plaintiff admission to graduate school on the basis

of his race, McLaurin sued for injunctive relief, alleging

that the state law prohibiting integrated schools de

prived him of equal protection. The district court

agreed. The Oklahoma legislature then amended the

statute, allowing the university to admit the plaintiff

but restricting him to segregated facilities. The plain

tiff returned to the district court to seek injunctive re

lief, which the district court denied. The Supreme

Court reversed, holding that the amended state law

permitting segregated facilities deprived McLaurin of

his right to equal protection. Id. at 642. The Court no

where suggested that McLaurin’s ability to bring his

constitutional claim depended on a statutory cause of

action.4

4 Another landmark desegregation case, Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)—which also did not mention the

predecessor statute to § 1983—can be seen as a direct constitu

tional action as well, although commentators disagree on how to

characterize that case. Compare Berzon, Securing Fragile Foun

dations: Affirmative Constitutional Adjudication in Federal

Courts, 84 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 681, 685-686 (2009) (characterizing

Brown as a direct constitutional action) and Bandes, Reinventing

Bivens/ The Self-Executing Constitution, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev. 289,

355 (1995) (same), with Blackmun, Section 1983 and Federal Pro

tection of Individual Rights—Will the Statute Remain Alive or

Fade Away?, 60 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1, 1-2, 19 (1985) (characterizing

Brown as a § 1983 suit) and Smolla, Federal Civil Rights Acts

§ 14:2, at 391-392 (3d ed. 2011) (same). Regardless, Bolling dem

onstrates that there is a direct right of action under the Constitu

tion to challenge the legality of racial segregation in public schools.

In an equally important decision for minority vot

ing rights, the Court in Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461

(1953), sustained a constitutional challenge by black

citizens to one of a series of schemes to maintain

whites-only primary elections in Texas. Having aban

doned their claim for damages, the Terry plaintiffs

rested their equitable claims directly on the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments. Id. at 478 nn.2 & 3 (Clark,

J. concurring). The Court struck down the discrimina

tory primary as unconstitutional. Id. at 470; see also id.

at 467 n.2 (plurality opinion) (noting that the Fifteenth

Amendment is ‘“self-executing”’). In so ruling, the

Court relied on its earlier decision in Guinn v. United

States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915), which invalidated grandfa

ther clauses under the Fifteenth Amendment, even

though Congress had not enacted specific legislation

reaching primary elections, based on “the self

executing power of the 15th Amendment,” id. at 368.

Several of this Court’s pathmarking decisions es

tablishing the rights of noncitizens also reached the

Court by way of direct action. For example, in Truax

v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915), this Court held that an

Arizona statute prohibiting the employment of nonciti

zens violated their rights to equal protection under the

Fourteenth Amendment. The Court did not suggest

the case was before it under a statutory cause of action

such as § 1983, but rather stressed that the plaintiff had

invoked the equitable power of the district court to re

strain unconstitutional action. Similarly, in Terrace v.

Thompson, 263 U.S. 197 (1923), the Court, although re

jecting an immigrant’s constitutional claim on the mer

its, stressed that the power to compel compliance with

the Constitution rested on the courts’ traditional equi

table powers, noting that equity jurisdiction will be ex

ercised to enjoin unconstitutional state laws “wherever

9

it is essential in order effectually to protect property

rights and the rights of persons against injuries other

wise irremediable.” Id. at 214.

Similarly, one of this Court’s leading decisions on

the meaning of “liberty” within the Due Process

Clause, Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925),

arrived at the Court by way of a direct action brought

to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment and to prevent

Oregon officials from implementing a state compulsory

education law that would have forced all children to at

tend public schools. See id. at 530. The Court nowhere

referred to a statutory cause of action under which the

claim for equitable relief was brought. The district

court where the case was originally brought observed

that “ [t]he question as to equitable jurisdiction is a sim

ple one, and it may be affirmed that, without contro

versy, the jurisdiction of equity to give relief against

the violation or infringement of a constitutional right,

privilege, or immunity, threatened or active, to the det

riment or injury of a complainant, is inherent, unless

such party has a plain, speedy, and adequate remedy at

law.” Society of Sisters v. Pierce, 296 F. 928, 931 (D.

Or. 1924) (emphasis added).

This theme—that the courts have inherent author

ity to restrain violations of the Constitution, so long as

they have subject-matter jurisdiction—runs through

out the Court’s decisions and has never been seriously

questioned. In Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684 (1946)

(footnote omitted), the Court observed that “it is estab

lished practice for this Court to sustain the jurisdiction

of federal courts to issue injunctions to protect rights

safeguarded by the Constitution and to restrain indi

vidual state officers from doing what the 14th Amend

ment forbids the State to do”—without any mention of

a statutory vehicle such as § 1983. And although Jus

10

tices of this Court have debated whether damages

should be available to remedy past constitutional viola

tions in the absence of a statutory cause of action, see

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents o f Federal Bu

reau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971); Correctional

Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 75 (2001)

(Scalia, J., concurring), the Court has never questioned

courts’ inherent authority to enjoin threatened or ongo

ing constitutional violations. See, e.g., Carlson v.

Green, 446 U.S. 14, 42 (1980) (Rehnquist, J., dissenting)

(criticizing direct constitutional actions for damages,

but acknowledging tradition of direct constitutional ac

tions for equitable relief, and noting that “ [t]he broad

power of federal courts to grant equitable relief for

constitutional violations has long been established”).

Moreover, contrary to petitioner’s assertion (Pet.

Br. 43-44), the Court has entertained such direct ac

tions to enforce the Constitution regardless whether

that claim was brought to prevent a threatened en

forcement action and might have been raised in defense

to such an action. See infra pp. 18-22; U.S. Cert.

Amicus Br. 17-18 (acknowledging that “not all of this

Court’s” preemption cases involved claims raised in de

fense to enforcement actions). Indeed, where the plain

tiff could not bring the claim defensively to an enforce

ment action, the case for exercise of the courts’ equity

power is particularly compelling because the plaintiff

could well have no other way to vindicate his constitu

tional rights. In the desegregation and voting rights

cases discussed above, for example, there was no clear

way that the plaintiffs seeking to vindicate their consti

tutional rights could have obtained a ruling on the mer

its of their claims except through affirmative litigation.

And in Truax, the district court observed that the non

citizen’s constitutional claim presented an appropriate

11

case for the exercise of equity power because under the

challenged Arizona statute only employers, not (non

citizen) employees, were subject to criminal prosecu

tion; thus the noncitizen employee would have had no

other forum for his claim to be heard. See Raich v.

Truax, 219 F. 273, 283-284 (D. Ariz. 1915). If a plaintiff

seeking to enforce the Constitution has no other forum

in which to raise his claim, that provides a stronger—

not a weaker—rationale for the courts to entertain a

direct equitable action.

B. Constitutional Claims Outside The Civil

Rights Context Have Also Long Been En

forceable Through Direct Actions

These civil rights cases are in keeping with histori

cal tradition, in which this Court has long recognized

direct actions to enforce constitutional provisions, re

gardless whether Congress has provided a specific

statutory vehicle for enforcement of the Constitution.

One of the earliest examples is Osborn v. Bank of

United States, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 738 (1824). This

Court resolved the Bank of the United States’ suit

against the Ohio Auditor for collecting a state tax that

conflicted with the federal statute that created the

Bank. Although no statute created a cause of action for

the Bank, this Court found that the dispute warranted

the “interference of a Court,” and it held the Ohio law

unconstitutional on the ground that it was “repugnant

to a law of the United States” and therefore void under

the Supremacy Clause. Id. at 838, 868.

In the years after Osborn, and with increasing fre

quency after Congress provided for federal-question

jurisdiction in 1875, courts routinely entertained suits

to enforce directly a broad range of constitutional pro

visions, including the Contracts Clause, the Fourteenth

12

Amendment’s Due Process Clause, and the dormant

Commerce Clause. See, e.g., Hays v. Port o f Seattle,

251 U.S. 233 (1920) (Due Process Clause and Contracts

Clause); Vicksburg Waterworks Co. v. Mayor & A l

dermen of Vicksburg, 185 U.S. 65 (1902) (Contracts

Clause); Chicago Burlington & Quincy R.R. Co. v. City

of Chi., 166 U.S. 226 (1897) (Due Process Clause); Scott

v. Donald, 165 U.S. 107 (1897) (Commerce Clause); A l

len v. Baltimore & Ohio R.R. Co., 114 U.S. 311 (1884)

(Contracts Clause). Particularly noteworthy are the

direct actions for equitable relief brought to enforce the

Contracts Clause, because it still is not settled in this

Court whether claims under the Contracts Clause may

be brought under § 1983. See Dennis v. Higgins, 498

U.S. 439, 456-457 (1991) (Kennedy, J., dissenting);

Crosby v. City o f Gastonia, 635 F.3d 634, 640-641 (4th

Cir. 2011) (noting issue), petition for cert, filed, No. 10-

1479 (U.S. June 8, 2011). Nonetheless, the Court ex

plained in Vicksburg Waterworks that the Contracts

Clause claim was properly before it because “the case

presented by the bill is within the meaning of the Con

stitution of the United States and within the jurisdic

tion of the circuit court as presenting a Federal ques

tion”—without suggesting that a statutory cause of ac

tion was also necessary. 185 U.S. at 82. The Court

more recently upheld a Contracts Clause claim in such

a direct-action posture in Allied Structural Steel Co. v.

Spannaus, 438 U.S. 234 (1978), without discussing

whether the claim might have been brought under

§ 1983.

One of the most notable of these cases was Ex

Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908). After the Minnesota

Attorney General signaled his intention to enforce a

state law limiting the rates that railroads could charge,

a group of railroad shareholders sued him to enjoin en

13

forcement of that law, arguing that it violated the

Commerce Clause and Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. The Court concluded that the

Eleventh Amendment does not bar suits against state

officers to enjoin violations of the Constitution or fed

eral law. Id. at 159-160. The Court also concluded that

the federal courts had jurisdiction because the case

raised “Federal questions” directly under the Constitu

tion. Id. at 143-145. The Court thus viewed the Consti

tution—paired with the federal-question jurisdiction

statute—as providing the basis of the plaintiffs’ right to

sue a state officer to enjoin an alleged constitutional

violation. As this Court has observed, “the availability

of prospective relief of the sort awarded in Ex parte

Young gives life to the Supremacy Clause. Remedies

designed to end a continuing violation of federal law are

necessary to vindicate the federal interest in assuring

the supremacy of that law.” Green v. Mansour, 474

U.S. 64, 68 (1985). Indeed, scholars have concluded that

“the best explanation of Ex parte Young and its prog

eny is that the Supremacy Clause creates an implied

right of action for injunctive relief against state officers

who are threatening to violate the federal Constitution

and laws.”5

Also demonstrating this principle are the numerous

cases in which this Court has resolved structural con

stitutional claims brought against the federal govern

ment without suggesting that a statutory cause of ac

tion was necessary for those claims to be before the

courts, and where there was no evident alternative fo

rum for those claims to be heard (such as under the

5 Wright et ah, Federal Practice and Procedure § 3566, at 292

(3d ed. 2008).

14

Administrative Procedure Act or in defense to an en

forcement action). See Printz v. United States, 521 U.S.

898 (1997); New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144

(1992); South Carolina v. Baker, 485 U.S. 505 (1988);

South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987); Youngstown

Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); see

also Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting

Oversight Bd., 130 S. Ct. 3138, 3151 & n.2 (2010) (ruling

that Appointments Clause claim was properly before

the courts, despite the absence of a statutory cause of

action).6

C. The Supremacy Clause As Well May Be En

forced Through Direct Equitable Actions

Given the courts’ historical willingness to entertain

direct actions to enforce the Constitution, it would be

surprising to learn that the Supremacy Clause, alone

among the Constitution’s provisions, could not be so en

forced. As the Framers explained, the Supremacy

Clause is fundamental to the Constitution, for if the

laws of the United States “were not to be supreme,”

then “they would amount to nothing.” Federalist No.

33 (Hamilton). The Supremacy Clause thus “flows im

mediately and necessarily from the institution of a fed

eral government.” Id.; see also Santa Rosa Br. 30-31.

In keeping with historical tradition, direct actions un

der the Supremacy Clause have played an important

In its most recent Term, this Court reiterated that it will

entertain individuals’ challenges based on federal structural con

stitutional principles. See Bond, 131 S. Ct. at 2363-2364 (“The in

dividual, in a proper case, can assert injury from governmental

action taken in excess of the authority that federalism defines.”);

see also id. at 2365 (“The structural principles secured by the

separation of powers protect the individual as well.” ).

15

role in vindicating the supremacy of federal law, as

Osborn and Ex parte Young illustrate.

This Court has implicitly recognized a right of ac

tion under the Supremacy Clause to enjoin preempted

state law in many contexts—including cases where the

preempting federal law was enacted pursuant to Con

gress’s Spending Clause powers, and where state par

ticipation in the federal program was voluntary.7 By

routinely resolving such claims on the merits, without

regard to whether a federal statute confers a right of

action, this Court has established not only that federal

courts have subject-matter jurisdiction over claims to

enjoin preempted state law but that there is a right of

action under the Supremacy Clause for such claims.

See U.S. Cert. Amicus Br. 15-18 (recognizing that the

Court has often decided preemption claims on their

merits, implicitly assuming that a cause of action exists

under the Supremacy Clause to challenge preempted

state law). It is particularly noteworthy that the Court

entertained such Supremacy Clause claims without ref

7 See, e.g., Arkansas Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. v. Ahl-

bom, 547 U.S. 268 (2006) (federal Medicaid law preempts state

statute imposing liens on tort settlement proceeds). In Pharma

ceutical Research & Manufacturers of America v. Walsh, 538 U.S.

644 (2003) (“PhRMA”), seven Justices (four in the plurality and

three in dissent) reached and resolved the merits of plaintiffs

claim that the challenged state law was preempted by the federal

Medicaid statute. See id. at 649-670 (plurality opinion) (finding on

the merits that state law was not preempted); id. at 684 (O’Connor,

J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) (finding on the merits

that the state law was preempted). By so doing, seven Justices

implicitly concluded both that the Court had the authority to re

solve the case under federal-question jurisdiction and that the

plaintiff had a claim to injunctive relief under the Supremacy

Clause. See id. at 668 (plurality opinion).

16

erence to a statutory cause of action long before Maine

v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980), established that § 1983

may be used to vindicate federal statutory—in addition

to federal constitutional—rights against state interfer

ence. See, e.g., Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc.

v. Paul, 373 U.S. 132 (1963); Hines v. Davidowitz, 312

U.S. 52 (1941); Asakura v. City o f Seattle, 265 U.S. 332

(1924). That tradition continues unbroken to this day.8

In short, “the rule that there is an implied right of

action to enjoin state or local regulation that is pre

empted by a federal statutory or constitutional provi

g

See, e.g., Cuomo v. Clearing House Ass’n, L.L.C., 129 S. Ct.

2710 (2009) (regulations promulgated under National Bank Act

preempt enforcement of executive subpoenas from state Attorney

General); Rowe v. New Hampshire Motor Transp. Ass’n, 552 U.S.

364 (2008) (Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act

preempts state requirements related to the transport of tobacco

products); Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268 (federal Medicaid law preempts

state statute imposing liens on tort settlement proceeds); Watters

v. Wachovia Bank, N.A., 550 U.S. 1 (2007) (National Bank Act pre

empts state supervision of mortgage-lending activities by national

bank affiliates); PhRMA, 538 U.S. at 649-670 (plurality opinion)

(Medicaid Act did not preempt state prescription-drug rebate law);

Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly, 533 U.S. 525 (2001) (Federal Ciga

rette Labeling and Advertising Act preempts state regulations on

cigarette advertising); Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council,

530 U.S. 363 (2000) (federal Burma statute preempts state statute

barring state procurement from companies that do business with

Burma); United States v. Locke, 529 U.S. 89 (2000) (various federal

statutes preempt state regulations concerning, inter alia, the de

sign and operation of oil tankers); Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67

(1997) (federal election statute preempts Louisiana’s “open pri

mary” statute); Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85 (1983)

(ERISA preempts portions of state benefits law); see also Sloss,

Constitutional Remedies for Statutory Actions, 89 Iowa L. Rev.

355, 365-400 (2004) (canvassing this Court’s case law on preemp

tion claims).

17

sion—and that such an action falls within federal

question jurisdiction—is well established.” Hart &

Wechsler’s The Federal Courts & The Federal System

807 (Fallon et al. eds., 6th ed. 2009) (collecting cases).

This Court’s decision in Golden State Transit Corp.

v. City o f Los Angeles, 493 U.S. 103 (1989), is consistent

with this analysis. That decision makes clear that

§ 1983 does not provide a home for all preemption

claims (but may be used only to vindicate federal

“rights”), see id. at 107, but it nowhere suggests that

preemption claims may not be directly asserted merely

because § 1983 does not provide a vehicle to do so. That

the Supremacy Clause itself “does not create rights en

forceable under § 1983,” id. (emphasis added) means

only that certain preemption claims may not be brought

under § 1983, not that such claims may not be brought

at all. Indeed, the dissent in Golden State Transit,

which would have denied the award of money damages

under § 1983, made that very point, explaining that de

nying relief under § 1983 “would not leave the company

without a remedy” because “§ 1983 does not provide

the exclusive relief that the federal courts have to of

fer,” and that the plaintiffs could seek an injunction on

preemption grounds. Id. at 119 (Kennedy, J., dissent

ing).9

9 Section 1983 is not duplicative of the right of action for in

junctive relief under the Supremacy Clause. By enacting § 1983,

Congress expanded the kinds of state action that private litigants

could challenge and the remedies they could seek beyond those

available in suits directly under the Constitution. See Cal. Phar

macists Br. 35-39; Dominguez Br. 29-34; Santa Rosa Br. 27-28.

That § 1983 has been an important mechanism to secure constitu

tional rights by providing damages remedies against state and lo

cal officials does not mean that § 1983 is the only avenue through

which unconstitutional state action can be challenged.

18

Although petitioner and his amici have acknowl

edged that the federal courts have previously enter

tained direct actions to enforce the Constitution (in

cluding the Supremacy Clause), they have suggested

that, where Congress has not provided a vehicle such

as § 1983 for such claims to be entertained, then those

claims should be remitted to state courts, under what

ever procedures the States might have provided for

them to be heard—or that, at most, the federal courts

should entertain such direct actions only when they are

brought to prevent the threatened imminent enforce

ment of an unconstitutional or preempted state law.

See Pet. Br. 43-44; National Governors Ass’n et al.

Amicus Br. 22-26; U.S. Merits Amicus Br. 19-22.10

Those suggestions should be rejected for several rea

sons.

First, those arguments are inconsistent with this

Court’s uniform precedent. This Court has entertained

and sustained many direct equitable actions under the

Constitution, including the Supremacy Clause, and also

including preemption claims based on a federal spend

ing statute, even when there was no evident enforce

ment action to which the federal claim might be raised

as a defense. For example, in Crosby v. National For

eign Trade Council, 530 U.S. 363 (2000), the challenged

10 The United States has taken the position elsewhere that

the Supremacy Clause provides a direct cause of action that is not

limited to asserting a defense to a state enforcement action. See

Compl., United States v. Arizona, 10-cv-01413 (D. Ariz. July 6,

2010) (filed by the United States as plaintiff challenging Arizona

immigration law, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief and as

serting “Violation of the Supremacy Clause” as its first cause of

action); Compl., United States v. Alabama, ll-ev-02746 (N.D. Ala.

Aug. 1,2011) (similar, in challenge to Alabama law).

19

Massachusetts law barred government procurement of

goods and services from companies doing business with

Burma. See id. at 366-367. There was no “enforce

ment” action in which the companies could raise pre

emption as a defense; the plaintiffs simply could no

longer get government contracts. This Court held that

the state law was preempted, necessarily presuming

that there was a right of action under the Supremacy

Clause that could be asserted directly and not merely in

defense of an enforcement action. Id. at 367; see also

PhRMA, 538 U.S. at 649-670 (plurality opinion); id. at

684 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part and dissenting in

part) (seven Justices resolving Medicaid-based preemp

tion claim on the merits where that claim was raised

affirmatively and not in defense to an enforcement ac

tion); supra pp. 10-11 (noting other examples of direct

constitutional claims being entertained where they

could not have been raised as defenses to enforcement

actions).

Second, a rule requiring preemption claims to be

advanced defensively only, while allowing claims based

on a violation of constitutional rights to go forward in

federal court under § 1983, would be extraordinarily

inefficient and would undermine the effective vindica

tion of federal law. Litigants frequently pursue both

preemption theories and other constitutional claims.

This Court’s cases teem with examples: businesses

commonly pursue both preemption claims and claims

under the Commerce, Contracts, or Due Process

Clauses; immigrants pursue both preemption claims

and claims under the Equal Protection Clause and First

Amendment; racial minorities pursue both statutory

claims and claims under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Very often, courts turn to the preemp

tion claim first in order to avoid reaching difficult con

20

stitutional questions. See, e.g., Crosby, 530 U.S. 363

(holding state procurement statute preempted by fed

eral Burma statute, and thereby avoiding dormant For

eign Commerce Clause claim); Hines, 312 U.S. 52 (hold

ing Pennsylvania registration law for noncitizens pre

empted by federal legislation enacted while the case

was before the Supreme Court, and thus avoiding equal

protection claim).

If litigants could not pursue both preemption

claims (directly) and other constitutional claims (under

§ 1983) in a single action for equitable relief, but were

required to pursue preemption theories not cognizable

under § 1983 only in state court, then they would be

forced either to divide their federal claims between fed

eral and state courts—which could well be barred by

rules against splitting causes of action—or to forgo the

federal forum for their § 1983 claims—which would be

contrary to the strong congressional policy in favor of

affording a federal forum for such claims. See, e.g.,

Patsy v. Board of Regents o f Fla., 457 U.S. 496 (1982).

The far more efficient and sensible rule, as well as the

one more consistent with this Court’s decisions, is to

allow equitable claims based on all provisions of the

Constitution, including the Supremacy Clause, to be

entertained in affirmative litigation through an action

directly under the Constitution.

In addition, the rule proposed by petitioner and its

amici would not adequately assure the supremacy of

federal law. Many Supremacy Clause claims cannot be

raised defensively at all, because there is no enforce

ment action in which they can be raised; in such circum

stances, an affirmative direct action under the Consti

tution is the only way in which the supremacy of fed

eral law could be established. See Sloss, Constitutional

Remedies for Statutory Actions, 89 Iowa L. Rev. 355,

21

406 (2004) (discussing such claims). And even when a

litigant might be able to assert his federal claim in de

fense of state enforcement actions or in defense to state

common law claims, his ability to establish the suprem

acy of federal law should not be dependent on the ven

ues that state law has happened to make available.11

Indeed, this Court has long recognized that “it is one of

the most valuable features of equity jurisdiction, to an

ticipate and prevent a threatened injury.” Vicksburg

Waterworks, 185 U.S. at 82.

The history of the civil rights movement in this

country well illustrates the need to enforce federal

rights in the federal courts, without reliance on legisla

tive grace or the vagaries of state law. Had § 1983

never been enacted, it could hardly be the case that

state laws providing for segregated schools, white pri

maries, and restrictions on immigrants could have gone

unchallenged. Plaintiffs could challenge, and did chal

lenge, such unconstitutional state laws directly under

the Supremacy Clause. And nothing in the Supremacy

Clause suggests that it may not also be used directly to

challenge state laws because they conflict with a fed

eral law, and not (or not just) the federal Constitution.

The Supremacy Clause itself provides that both the

Constitution “and the Laws of the United States which

shall be made in Pursuance thereof ... shall be the su

preme Law of the Land.” U.S. Const, art. VI (emphasis

added).

11 Cf. Haywood v. Drown, 129 S. Ct. 2108 (2009) (state courts

cannot refuse to entertain certain classes of federal claims);

Howlett ex rel. Howlett v. Rose, 496 U.S. 356 (1990) (state court

cannot apply state sovereign-immunity principles to refuse adjudi

cation of federal law claim); Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947)

(state courts cannot discriminate against federal claims).

22

Finally, nothing in the Supremacy Clause or this

Court’s precedent indicates that statutes enacted pur

suant to Congress’s Spending Clause power should be

treated any differently than statutes enacted pursuant

to other sources of congressional power, i.e., that direct

causes of action may not be brought to vindicate the

federal structural interest in the supremacy of Spend

ing Clause statutes. Indeed, numerous Spending

Clause statutes—including Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of

1972, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act—are critical in preventing discrimination and pro

tecting civil liberties, and many others—such as Medi

caid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Pro

gram (previously called the Food Stamp Program)—

provide a critical safety net on which low-income indi

viduals rely for survival. II.

II. Precluding Direct Rights Of Action Under The

Supremacy Clause Would Have Broad And

Harmful Consequences For Maintaining The Su

premacy Of Federal Law

An action under the Supremacy Clause provides an

important—and sometimes the only—avenue to vindi

cate the supremacy of federal law. Barring a right of

action under the Supremacy Clause could effectively

foreclose this critical avenue for persons, especially mi

norities, immigrants, and low-income individuals, who

depend on federal law and who would otherwise be sub

ject to invalid state and local laws.

23

A. Minorities, Immigrants, And Low-Income In

dividuals Continue To Depend On Direct Ac

tions Under The Supremacy Clause To Chal

lenge Invalid State And Local Laws

Racial minorities, immigrants, and low-income in

dividuals continue to rely directly on the Supremacy

Clause to challenge invalid state and local laws in many

important areas, including immigration, fair housing,

public assistance, and health care. Many of those cases

have involved legislation enacted under Congress’s

Spending Clause power, and the courts have routinely

adjudicated and sometimes invalidated state laws that

conflicted with the federal legislation.

For example, several plaintiffs in recent years have

used the Supremacy Clause to challenge the increasing-

number of state laws that seek to restrict immigrants’

rights, including immigrants’ employment opportuni

ties. In Chamber o f Commerce v. Edmondson, 594

F.3d 742 (10th Cir. 2010), plaintiffs claimed that provi

sions of the Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection

Act of 2007, which created new employee verification

rules and imposed sanctions on employers that alleg

edly hire undocumented immigrants, conflicted with

federal immigration law, which sets forth a comprehen

sive scheme prohibiting the employment of such indi

viduals. The Tenth Circuit, which upheld in part a pre

liminary injunction against enforcement of the state

law, explained that a “party may bring a claim under

the Supremacy Clause that a local enactment is pre

empted even if the federal law at issue does not create

a private right of action.” Id. at 756 n.13 (internal quo

tation marks omitted); see also Chamber o f Commerce

v. Whiting, 131 S. Ct. 1968 (2011) (adjudicating preemp

tion challenge to Arizona law providing for the revoca

tion or suspension of licenses in certain circumstances

24

of state employers who knowingly hire undocumented

immigrants, but finding no preemption).

Numerous other courts similarly have addressed

preemption challenges, under the Supremacy Clause, to

state and local laws that affect immigrants’ access to

housing and other vital services. See Georgia Latino

Alliance for Human Rights v. Deal, No. ll-cv-1804,

2011 WL 2520752, at *6 (N.D. Ga. June 27, 2011) (find

ing independent jurisdictional grounds under the Su

premacy Clause to allow a preemption challenge

against Georgia’s Illegal Immigration and Enforcement

Act of 2011 and entering preliminary injunction); Bu-

quer v. City o f Indianapolis, No. ll-cv-708, 2011 WL

2532935, at *2 (S.D. Ind. June 24, 2011) (considering a

Supremacy Clause challenge to an Indiana law that al

lows, inter alia, law enforcement officers to make a

warrantless arrest of an immigrant under certain con

ditions and entering preliminary injunction); Villas at

Parkside Partners v. City o f Farmers Branch, 496 F.

Supp. 2d 757, 777 (N.D. Tex. 2007) (considering a Su

premacy Clause challenge to city ordinance that essen

tially “created its own classification scheme for deter

mining which noncitizens may rent an apartment” in

the city and entering preliminary injunction), perma

nent injunction entered, 577 F. Supp. 2d 858, 879

(2008); League o f United Latin Am. Citizens v. Wilson,

997 F. Supp. 1244 (C.D. Cal. 1997) (finding preempted

most provisions of a state law that, inter alia, re

stricted immigrants’ access to health care, social ser

vices, and education).

Low-income individuals have likewise invoked the

Supremacy Clause to ensure compliance with federal

housing laws. In Kemp v. Chicago Housing Authority,

No. 10-cv-3347, 2010 WL 2927417 (N.D. 111. July 21,

2010), a single mother of two argued that municipal

25

rules unlawfully allowed the Chicago Housing Author

ity to terminate her public housing assistance in cir

cumstances other than those specified and limited by

the United States Housing Act of 1937. Kemp sought

to enjoin the local law as preempted under the Suprem

acy Clause. Although the court ultimately did not

grant relief because of the Anti-Injunction Act, it con

cluded that the Supremacy Clause “create[s] rights en

forceable in equity proceedings in federal court,” and

that it could therefore exercise jurisdiction over

Kemp’s preemption claim. Id. at *3 (internal quotation

marks omitted).

Persons receiving public assistance have also in

voked the Supremacy Clause to challenge state laws

that terminate medical or other benefits in contraven

tion of federal law. For example, in Comacho v. Texas

Workforce Commission, 408 F.3d 229 (5th Cir. 2005),

the court invalidated under the Supremacy Clause

state regulations that expanded the circumstances, be

yond those allowed by federal law, under which Medi

caid benefits could be cut off for low-income adults re

ceiving assistance under the federal Temporary Assis

tance to Needy Families program.

Finally, the Eighth Circuit in Lankford v.

Sherman, 451 F.3d 496 (8th Cir. 2006), relied directly

on the Supremacy Clause to preliminarily enjoin a Mis

souri regulation that limited Medicaid coverage of du

rable medical equipment to certain populations, making

most Medicaid recipients in Missouri ineligible to re

ceive such items even if medically necessary. Id. at 509.

The court found that the regulation conflicted with

Medicaid’s requirements and goals and therefore was

likely preempted under the Supremacy Clause. Id. at

513 (holding that plaintiffs had “established a likelihood

26

of success on the merits of their preemption claim” for

obtaining a preliminary injunction).

The Supremacy Clause right of action therefore

remains critically important to minorities, immigrants,

and low-income persons in our society who rely on it for

vindication of federal law. The availability of that di

rect action ensures that state and local governments

cannot undermine federal law by enacting statutes and

regulations that deviate from federal requirements but

would, absent a Supremacy Clause action, be effec

tively insulated from judicial review.

B. Precluding Rights Of Action Under The Su

premacy Clause Would Undermine Important

Federal Interests

Precluding a right of action under the Supremacy

Clause would leave important rights and interests ef

fectively unprotected. Not only will the rights of indi

vidual litigants seeking to invalidate unconstitutional

state laws be harmed, but important federal supremacy

interests could go unprotected as well.

First, precluding rights of action under the Su

premacy Clause would leave few, if any, effective reme

dies to force state compliance with many federal laws

that are intended to benefit minorities, immigrants, and

low-income persons in our society. In the context of

laws enacted under Congress’s Spending Clause power,

the termination of federal funding may sometimes be

theoretically available to remedy the State’s failure to

comply with its obligations under the Medicaid Act or

other Spending Clause laws, see PhRMA, 538 U.S. at

675 (Scalia, J., concurring in the judgment), but that

remedy is so rare and drastic as to be effectively un

available as a meaningful enforcement tool. As com

mentators have explained, both political considerations

27

and procedural hurdles make withdrawal of federal

funding an illusory remedy. See, e.g., Mank, Suing Un

der § 1983: The Future After Gonzaga University v.

Doe, 39 Hous. L. Rev. 1417, 1431-1432 (2003) (“ [A]s a

practical matter, federal agencies rarely invoke the

draconian remedy of terminating funding to a state

found to have violated the [federal] conditions because

there are often lengthy procedural hurdles that allow a

state to challenge any proposed termination of funding,

and members of Congress from that state will usually

oppose termination of funding.”); Perkins, Medicaid:

Past Successes and Future Challenges, 12 Health Ma

trix 7, 32 (2002) (“ [T]he Medicaid Act provides for the

Federal Medicaid oversight agency to withdraw federal

funding if a State is not complying with the approved

State Medicaid plan; however,... this is a harsh remedy

that has rarely, if ever, been followed through to its

conclusion.”); Key, Private Enforcement o f Federal

Funding Conditions Under § 1983: The Supreme

Court's Failure to Adhere to the Doctrine o f Separation

of Powers, 29 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 283, 292-293 (1996)

(“ [OJften the agency’s only enforcement mechanism is a

cutoff of federal funds for the program[,| ... [which] is

rarely, if ever, invoked.”).12

Moreover, termination of federal funding would in

many circumstances be counterproductive and contrary

to Congress’s intent that the funding program be im

plemented to provide a wide benefit. Indeed, persons

12 As respondents point out (Cal. Pharmacists Br. 2-3, 17),

this case shows how difficult it can be for the Executive Branch to

enforce the supremacy of federal law by itself; even after the re

sponsible federal agency disapproved state rate cuts as inconsis

tent with federal law, the State continued to implement its invalid

legislation.

28

who receive crucial benefits and services from federal

programs usually do not want federal funding to be

terminated. Terminating federal funding would not

protect the interests of those injured by the State’s

noncompliance with federal law; rather, it would harm

the very people Congress intended to benefit. See

Cannon v. University o f Chi., 441 U.S. 677, 704-705

(1979) (explaining that “termination of federal financial

support for institutions engaged in discriminatory prac

tices ... is ... severe” and “may not provide an appro

priate means of accomplishing” the purposes of the

statute); see also Hills, Dissecting the State: The Use of

Federal Law to Free State and Local Officials from

State Legislatures’ Control, 97 Mich. L. Rev. 1201,

1227-1228 (1999) (“ [T]he sanction of withdrawing fed

eral funds from noncomplying state or local officials is

usually too drastic for the federal government to use

with any frequency: withdrawal of funds wall injure the

very clients that the federal government wishes to

serve.”).

The more effective way to vindicate the objectives

of federal law is to allow for the important role that

private parties play in enforcing the supremacy of fed

eral statutes. As the United States previously argued

in this case, “those programs in which the drastic

measure of withholding all or a major portion of federal

funding is the only available remedy would be generally

less effective than a system that also permits awards of

injunctive relief in private actions in appropriate cir

cumstances.” See U.S. Cert. Amicus Br. 19. In such

circumstances, an injunction would force a State to

comply with the federal provision at issue without

harming the intended beneficiaries of the federal pro

gram.

29

Nor would it be appropriate to force individuals

who depend on federal law to rely exclusively on the

federal government to bring affirmative litigation to

enforce compliance with the Supremacy Clause. Pri

vate rights of action are necessary because the gov

ernment lacks the resources to police preemption dis

putes between States and private parties. See Sloss,

Constitutional Remedies For Statutory Actions, 89

Iowa L. Rev. at 404. Private rights of action “increase

the social resources devoted to law enforcement, thus

complementing government enforcement efforts.” Ste

phenson, Public Regulation of Private Enforcement:

The Case for Expanding the Role o f Administrative

Agencies, 91 Va. L. Rev. 93, 108 (2005); see also Ahl-

bom, 547 U.S. at 291. In short, absent a right of action

under the Supremacy Clause there could well be no

meaningful remedy at all for state noncompliance.13

A private right of action under the Supremacy

Clause serves other important values as well. The Su

premacy Clause supports the structural guarantee of

13' Indeed, it is not entirely clear that the federal government

would always be authorized to sue to compel enforcement of fed

eral law. Private plaintiffs directly affected by state laws have

Article III standing to sue to enjoin their enforcement; the federal

government might not. And if private plaintiffs did not have a di

rect right of action to sue under the Supremacy Clause, it might

well be questioned whether the United States could sue without

its own statutory cause of action. Cf. United States v. City of Phi-

la., 644 F.2d 187 (3d Cir. 1980) (holding that United States may not

sue local governments for injunction against violation of Four

teenth Amendment, absent statutory authority to sue). The Court

need not resolve those issues in this case, but at a minimum there

would be no assurance that enforcement by the United States

would necessarily be available if private lawsuits were not permit

ted.

30

federalism—namely, that federal law will remain para

mount. And that interest can only be effectively vindi

cated by ensuring that preempted state laws are in

validated—a goal that, for the reasons described above,

can best be achieved through a private right of action.

In addition, a private right of action, by allowing robust

enforcement for preemption claims, fosters uniformity

and predictability in the application of both federal and

state law.14 Thus, in order to realize the Constitution’s

fundamental promise that federal law will remain

paramount over invalid state and local laws, it is essen

tial that this Court continue—as it has done for nearly

two hundred years—to allow litigants to bring preemp

tion challenges directly under the Supremacy Clause.

CONCLUSION

The judgments of the court of appeals should be af

firmed.

14 Preemption claims in immigration and other areas of law

have also been critical to preserving the federal government’s

paramount role in foreign policy. See, e.g., Hines, 312 U.S. at 63

(“Our system of government is such that the interest of the cities,

counties and states, no less than the interest of the people of the

whole nation, imperatively requires that federal power in the field

affecting foreign relations be left entirely free from local interfer

ence.”); id. at 66-67; Toll v. Moreno, 458 U.S. 1,10-13 (1982).

31

Respectfully submitted.

M ic h a e l D. G o tte sm a n

W ilm er C u tler P ickering

H a l e a n d D o r r l l p

399 Park Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10022

St e v e n R . Sh a p ir o

A m erican C iv il L iberties

F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, N.Y. 10025

V ic to r V ir a m o n t e s

M e x ic a n A m e r ic a n

L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d

634 S. Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

P a u l R .Q . W o lfso n

Counsel of Record

Sh ir l e y Cassin W oodward

M a d h u C h u gi-i

W ilm er C u tler P ickering

H a l e a n d D o r r l l p

1875 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 663-6000

paul.wolfson@wihnerhale.com

J ohn P a y to n

D ir e c t o r -C o u n se l

NAACP L egal D efen se an d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, N.Y. 10013

J osh u a C iv in

NAACP L egal D efen se and

E d u c a tio n a l F u n d , In c .

1444 I Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

A u g u s t 2011

mailto:paul.wolfson@wihnerhale.com