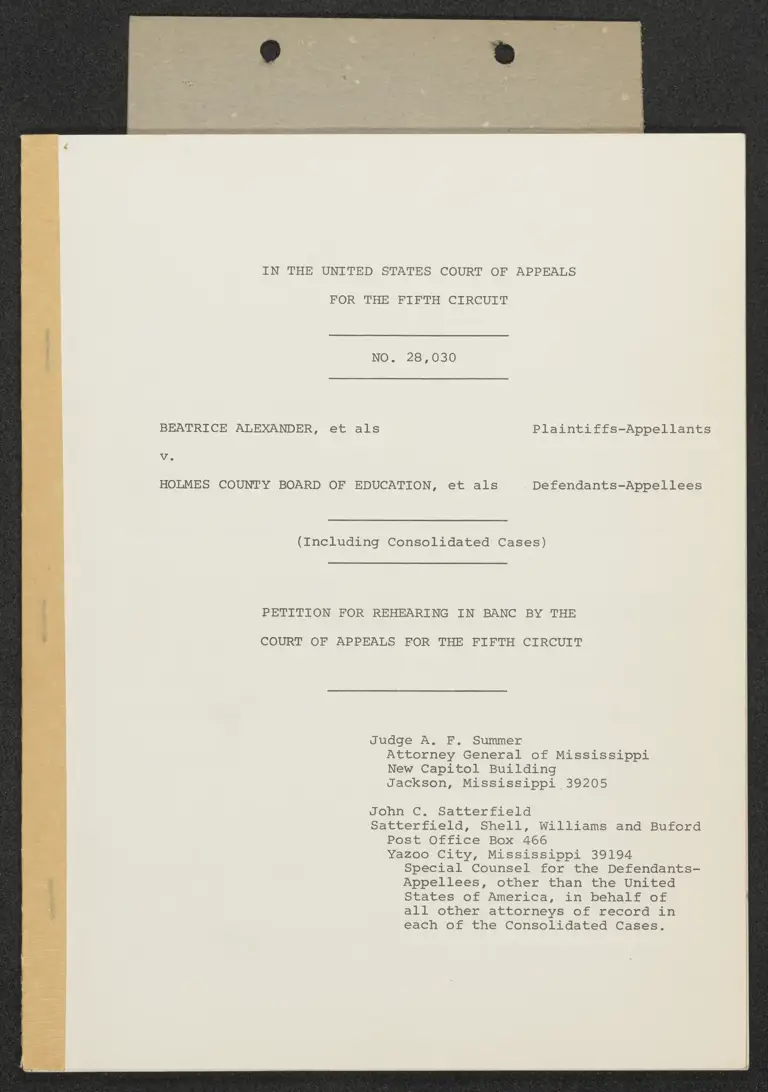

Petition for Rehearing In Banc aby the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

November 20, 1969

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Petition for Rehearing In Banc aby the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1969. 3790d52e-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdffa665. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/18ae1020-e5e0-4a18-98a1-3fa5e8171b3c/petition-for-rehearing-in-banc-aby-the-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 25,030

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et als Plaintiffs-Appellants

VV.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als Defendants-Appellees

(Including Consolidated Cases)

PETITION FOR REHEARING IN BANC BY THE

COURT OP APPEALS POR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Judge A. F. Summer

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

John C. Satterfield

Satterfield, Shell, Williams and Buford

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Defendants-

Appellees, other than the United

States of America, in behalf of

all other attorneys of record in

each of the Consolidated Cases.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

POR THE PIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 28030

JOAN ANDERSON, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant

57, (Civil Action No. 3700(J))

THE CANTON MUNICIPAL, SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al, and THE MADISON

COUNTY - SCHOO, DISTRICT, et. al Defendants-Appellees

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

Vv, {Civil Action No. 3779{(J))

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et al Defendants-Appellees

ROY LEE HARRIS, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

17. {Civil Action No. 1209(W))

THE YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et al Defendants-Appellees

JOHN BARNHARDT, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

Vv. {Civil Action No. 1300(T))

MERIDIAN SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al Defendants-Appellees

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

v7. {Civil Action No. 1302{(F))

THE ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL

DISTRICT and QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL. DISTRICT Defendants-Appellees

DIAN HUDSON, et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant

Vv. {Civil Action No. 3382(J))

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., et al Plaintiffs-Appellants

Ve (Civil Action No. 1096{(W))

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et al Defendants-Appellees

PETITION POR REHEARING IN BANC BY THE

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE PIPTH CIRCUIT

I.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Thizg petition for rehearing in banc is filed by all school

boards and related defendants in the cases captioned above, con-

golidated in this Court under Docket No. 28030. The discussion

herein also applies to the suits against the Wilkinson County

Poard of Fducation and the North Pike Consolidated School Distr-

ict. These two districts are included in the cases consolidated

as Docket No. 28042 and in the petition for rehearing filed therein.

To avoid prolixity and possible confusion of issues, there is

hereby adopted as a part hereof all matters set forth in the peti-

tion for rehearing in consolidated Docket No. 28042, to the extent

that the same are applicable here.

All of the above cases and the suits against the Wilkinson

County Board of Education and the North Pike Consolidated School

District were included in the petition for writ of certiorari filed

in the Supreme Court of the United States by private plaintiffs

-] =

and private intervenors. The other sixteen cases consolidated as

Docket No. 28042 were not respondents to such petition and hence

were not parties to the Per Curiam opinion of the Supreme Court

of the United States rendered on October 29, 1969.

11.

A GRAVE AND FATAL MISUNDERSTANDING

Being completely frank with this Court, when the announce-

ment was made from the bench at the pre-order conference on Nov-

ember 5 that the order had already been written putting into effect

all of each HEW plan (with a few minor exceptions stated) and that

the hearing would be limited to questions concerning details, the

attorneys present were so stunned they were in a state of mental

shock and literally speechless.

The order entered here has dealt a crippling blow to public

education in the United States. It is resulting in an untold waste

of human resources. Chaos and confusion exist in the education of

thousands of children. All this is the result of haste. Not haste

of the courts, nor haste of the United States of America, nor haste

of the Attorney General of the United States, nor haste of the Sec-

retary Of Health, Education and Welfare, nor haste of the public

officials of this state. 1It is the result of haste of the attorneys

for the private plaintiffs in these particular cases.

This haste has brought about an understandable misunderstanding

between the different levels of our federal judicial system.

Knowing the desire of both this Court and the Supreme Court of

the United States to preserve public education, it is inescapable to

us that this Court felt it was mandatory for it to. act as it did in

these cases. This is borne out by the following extracts from the

initial statement of Judge Bell at the pre-order conference (page

i

references are to transcript of the proceedings):

(p.2) Ladies and gentlemen, we have called this pre-

order conference today for the purpose of making some

announcements and also to exchange views. After we make

some statements, we want everyone to feel free to ask

questions. We don't intend to have any legal arguments,

as such, but we do think it would be well for anyone that

has questions, that you feel free to make such inquiries

as you may have....

(p.3) We have also studied the Supreme Court decision in

these cases and we are of the view that action is required,

and immediate action....

(P.5) We have prepared a draft order, it is not a final

Order. We hope to put the Order out tomorrow. We did not

want to put an order out until we had this conference and

we want to tell you generally what is in the order now so

that you will be advised as to what questions you may wish

to pose.

(p.6) Now, we are going on then, and we say to effectuate

the conversion of these school systems to unitary school

systems within the context of the Supreme Court order the

following things have to be done, and then generally we are

putting into effect in every case, except the ones I will

tell you about, the recommended plan of the Office of Educa-

tion, HEW. And that is a permanent plan and not the interim

plan.

We cannot believe that this Court, which is familiar with the

devastating effect of requiring every step of the HEW plans to be

put into effect immediately, would have done so had it not felt it

was acting as specifically directed by the Supreme Court of the

United States.

We strongly urge that the Court reconsider its construction

of the duty imposed upon it by the Supreme Court of the United

States in its Per Curiam opinion of October 29. The discretion

vested in this Court is stated as follows:

2. The Court of Appeals may ln its discretion direct the

schools here involved to accept all or any part of the

August 11, 1969, recommendations of the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, with any modifications

which that court deems proper....

—3

The clause which delineates the bounds of this broad discre-

tion is as follows:

...insofar as those recommendations insure a totally unitary

school system for all eligible pupils without regard to race

Or. Color.

In the prior paragraph the Supreme Court directed this Court

to issue its decree and order, effective immediately, declaring

that these school districts:

(a) ...no longer operate a dual school system based on race

or color, and

(b) ...begin immediately to operate as unitary school systems

within which no person is to be effectively excluded from any

school because of race or color.

The Supreme Court did not, in this particular order, define a

"dual school system based on race or color". 1t did define a unji-

tary school system as being one "within which no person is to be

effectively excluded from any school because of race or color".

It is crystal clear that this Court of Appeals has the auth-

ority to require the schools to accept any part of the August 11,

1969, recommendations of HEW. It is also crystal clear that any

part put into effect may be "with any modifications which the Court

may deem proper".

We feel it is inescapable that the Supreme Court would not

have referred to "any part" nor authorized "any modifications which

the Court may deem proper" If it had been intended to prohibit this

Court from using a part of a HEW plan. This would include the use

of alternate steps, although they may have been called "interim

steps". Semantics may result in the destruction of the school dis-

tricts where the HEW plans use the word "interim" instead of "alter

nate". Apparently the term "interim" carried a connotation of

delay. In. fact, . a terminal plan: may go into effect immediately, at

d=

once, today, whether it includes one or two or more steps.

The plans for Hinds County, the Meridian Municipal Separate

School District, and the Holmes County School District contained

steps which this Court properly permitted to be followed.” In its

order of November 7 this Court very properly permitted the interim

plan to be utilized as a step or alternate in Quitman Consolidated

School District, and approved other modifications of HEW plans.

In its Per Curiam opinion the Supreme Court referred to

Griffin L/ and Green 2/, The Court said in Griffin, "the time for

mere 'deliberate speed' has run out". The Court stated in Green,

"the burden on the school board today is to come forward with a

plan that promises realistically to work and promises realistically

to work now"... Purthermore, as was said in Carr 3/, an effort

should be made by the school authorities and the courts to "expe-

dite the process of moving as rapidly as practical toward the goal

of a wholly unitary system of schools, not divided by race as to

either students or faculty".

In fact the problem here had its genesis in the interpreta-

tion placed upon words that a plan "promises" to work "now". The

construction of Green inherent in the November 7th order necessa-

rily interprets the word "now" to mean either something accomplished

in the past and existing today or something to be accomplished today

by the stroke of a pen or by the entry of an order. This construc-

tion is wholly inconsistent with the word "promises".

It is contradictory to Green, which was recognized and rein-

forced in Carr. .In Carr the Court said that, "as.stated in Green.v,.

County School Board, supra, 391. U.S. at 439":

It is incumbent upon the school board to establish that lts

proposed plan promises meaningful and immediate progress to-

ward disestablishing state-imposed segregation. It 1s incum-

bent upon the district court to weigh that claim in light Of

the facts at hand and in light of any alternatives which may

be shown as feasible and more promising in their effectiveness.

ok Bp

THE HEW PLANS, INCLUDING ALTERNATE OR "INTERIM" STEPS

IN STUDENT AND FACULTY INTEGRATION, PUT INTO IMMEDIATE

EFFECT UNITARY RACIALLY NONDISCRIMINATORY SCHOOL SYSTEMS

The Per Curiam opinion was rendered and is necessarily con-

strued in the context of Green, Raney4/ , Monroe 2/ and Carr. These

cases clearly and unmistakably describe the unitary racially non-

discriminatory school system which meets all constitutional

guarantees. Notes containing case references appear on last page hereof.

In Green such system is described as: "A racially nondiscrimi-

natory. school system" -- "a unitary, nonracial system of public

education" -- "a unitary system in which racial digcrimination

would be eliminated root and branch."

In Raney such system is described as: "A unitary, nonracial

school system".

In Monroe such school system is described as: "A racially

nondiscriminatory system" -- "a unitary system in which racial

discrimination would be eliminated root and branch" -- "a system

without a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school, just schools".

In Carr such school system is described as: "A system of pub-

lic education free of racial discrimination” -- "a completely uni-

fied unitary nondiscriminatory school system" -- "a racially non-

discriminatory school system".

The Supreme Court affirmatively declined to hold in Green that

the Fourteenth Amendment requires "compulsory integration", saying:

The Board attempts to cast the issue in its broadest form

by arguing that its "freedom-of-choice" plan may be faulted

only by reading the Fourteenth Amendment as universally re-

ly

quiring "compulsory integration’, -a reading if insists the

| wording of the Amendment will not support. But that argument

dgnores the thrust of Brown 11. ‘In the light of the command

| of that case, what is involved here is the question whether

| the Board has achieved the "racially nondiscriminatory

school system" Brown II held must be effectuated in order to

remedy the established unconstitutional deficiencies of its

segregated system.

It is only by a consideration of the many complex factors en-

tering into the educational process and particularly into the de-

segregation of formerly de jure and formerly de facto segregated

schools that the courts are able to chart the course which is in

the best interest of the students and of our public schools. This

was the objective stated by Mr. Justice Black in Carr.

In Green the Supreme Court found that the school system of

New Kent County was a dual school system and described such system

as follows:

.... Racial identification of the system's schools was com-

plete, extending not just. to the composition of student

bodies at the two schools but to every facet of school oper-

ations -- faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular

activities and facilities.

In Green, Raney and Monroe there was considered many of the

factors which, when taken as a whole and in combination, should

be utilized in determining the application of the following test:

Where the Court finds the board to be acting in good faith

and the proposed plan to have real prospects of dismantling

the state-imposed dual system 'at the earliest practicable

date' then the plan may be said to provide effective relief....

Moreover, whatever plan is adopted will require evaluation in

practice....

The elements elucidated in these cases included:

l. Every facet of school operations;

2. Faculty, staff and student body;

3. Transportation and construction of new buildings;

4. Extracurricular activities and facilities;

5. Majority to minority transfer;

<7=

6. Method of exercising the freedom of choice;

7. Assignment of students who did not exercise the freedom

Of choice;

8. Whether or not the "public school facilities for Negro

pupils (were) inferior to those provided for white

pupils”:

9. Operation of the freedom of choice plan "in a constitu-

tionally permissible fashion";

10. "All aspects of school life including faculties and

gtaffa’;

11. Whether "the board had indeed administered the plan in

a discriminatory fashion;

12. The comparative treatment of students attempting "to

transfer from their all-Negro zone schools to schools

where white students were in the majority";

13. The comparative treatment of "white students seeking

transfers from Negro schools to white schools";

14. Whether "the transfer (provision) lends itself to per-

petuation of segregation".

Within the broad statements of Green fall the following addi-

tional phases of a school system:

15. Athletic activities within the schools;

16. Parent-teacher associations;

17. Faculty and staff meetings within schools and of

faculties and staffs of the various schools at the

elementary, junior high school and high school levels;

18. School-sponsored visitation of student body officers

and student committees;

19. In-service training of teachers and staff to assist

in the desegregation process;

20. Participation by students in various types of student

organizations.

The unitary nondiscriminatory school system required in the

Per Curiam opinion has been described by the Court of Appeals of

the Sixth Circuit in Goss 5/ (which was decided in the light of

Green, Raney and Monroe) as follows:

og

In Green the Court said school boards must adopt plans which

"promise realistically to convert promptly to a system with-

out. a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school, but just schools.”

301 U.S. at 442, 88 S.Ct. at 1696, The Court further said

that it would be their duty "to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch.” 391 U.8. at 437-438, 88 S.Ct. at 1694, We are not

sure that we clearly understand the precise intendment of

the phrase "a unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated," but express our belief that Knoxville

has a unitary system designed to eliminate racial discrimi-

nation.

This opinion found that the Knoxville school system contained

five all-Negro schools and 29 schools in which the teaching staffs

were composed exclusively either of members of the Negro race or

members of the white race. Knoxville, Tennessee, previously had

schools segregated under state law. Nevertheless, the Court con-

cluded that this system met the requirements of a unitary, non-

discriminatory school system as laid down in Green, Monroe and

Raney.

In its Per Curiam order of October 29 in these cases the

Supreme Court defined the term "unitary school system" in the man-

date that this Court enter an order as to these nine school dis-

tvricts:

... directing that they begin immediately to operate as

unitary school systems within which no person is to be

effectively excluded from any school because of race or

color.

This. definition is in accord with the holding. of the Sixth

Circuit in Goss... IL is. also in. accord with the holding of this

Court in Broussard v. Houston Independent School District, May 30,

1968, 395 80.2d.817, Petition for. Rehearing in banc (in the.light

of Green, Monroe and Raney) denied October 2, 1968, 403 F.2d 34.

That case involved the same constitutional principles which are

applicable here. The issue was that of school construction which

=O

would perpetuate the Houston freedom of choice plan. The affir-

mance of the lower court was based upon the following principle

announced by the Court:

Indeed, under the Houston plan, as described by the school

authorities, it would appear that an "integrated, unitary

school system" is provided, where every school is open to

every child. It affords "educational opportunities on

equal terms to all". That is the obligation of the Board.

{Note 15) United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Bd4.,

supra, 380 7.24 p. 390, en banc consideration.

As noted above, petition for rehearing in banc in the light

of Green, Raney and Monroe (which had been handed down two days

before Broussard) was denied by the full Court on October 2, 1968.

Of course, the above twenty numbered subparagraphs are some-

what repetitious, being taken from the above three decisions.

Nevertheless, it is clear that when the HEW plans filed August 11,

1969, are put into effect as terminal plans, including the alter-

nate or interim steps in student and faculty integration, these

school systems will be operated as unitary school systems, unless

the Court holds that every single element mentioned in Green,

Raney and Monroe is a separate sine qua non of a unitary school

system.

In order to meet the general requirements of the Supreme

Court it is not necessary either (a) that the faculties be inte-

grated so that all systems "are going to have a ratio of almost

equal to that in the faculty population of the system" (finding

of Judge Bell, Tr. 9), or (b) that there be accomplished the com-

pulsory integration of all schools to the extent envisioned in

the over-all or final step of the HEW plans.

We respectfully submit that even if this extreme interpreta-

tion were correct, such alternate or interim steps are permitted.

=16~

There is little difference between the word "immediately" used in

the Per Curiam order of October 29 and the word "now" used in

Green. As was said by Judge Bell at the pre-order hearing (Tr.p.6):

Now, that is the language of the Supreme Court decision. It

is a little different from some of the language used in the

old Supreme Court decisions but probably means the same thing.

Certainly the present decision, which involved only a proce-

dural point, must be construed in the context of Green, Monroe,

Raney and Carxr.

1V.

ELIMINATION OF THE VESTIGES OF A DUAL SCHOOL SYSTEM AND

OPERATION OF A UNITARY SCHOOL SYSTEM DO NOT REQUIRE COM-

PULSORY STUDENT INTEGRATION OF EVERY SCHOOL NOR COMPUL-

SORY INTEGRATION OF ALL FACULTIES TO "A RATIO OF ALMOST

EQUAL TO THAT IN THE FACULTY POPULATION OF THE SYSTEM"

As we have set forth above, the Supreme Court of the United

States clearly used the words "all or any part of the August 11,

1969" HEW plans and "modifications" thereof because each plan con-

tains steps in both student and faculty integration. This neces-

sarily was done either (a) because the Supreme Court had had no

opportunity to study the twelve plans before it, or (b) because

the Supreme Court felt that a full and detailed study by this

Court would reveal that these plans exceeded the constitutional

requirements.

Neither the presence of schools attended exclusively or pre-

dominantly by Negroes nor the presence of faculties composed of

teachers of one race constitute vestiges of the dual system. After

the decisions in Green, Monroe, Raney and Hall Z/. the Court of

Appeals of the Sixth Circuit squarely faced this issue in Goss.

In holding that the operation of the Knoxville, Tennessee, school

system complied with all constitutional requirements, the Court

~1lle=

said:

Preliminarily answering question I, it will be sufficient

to say that the fact that there are in Knoxville some

schools which are attended exclusively or predominantly by

Negroes does not by itself establish that the defendant

Board of Education is violating the constitutional rights

of the school children of Knoxville. Deal v. Cincinnati

Bd, of "'Bducation, 369 PI.24 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert. denied,

380 (1.8. 847, B88 S.Ct. 39, 19 L..BPd.24 114 (1967); Marp Vv.

BA: of Education, 373 F.2d 75, 78 (6th Cir ,.-1966), cert.

denied, 389 U.S. B47, 88 S.Ct. 39, 19 L..EA.24 114 (1967).

Neither does the fact that the faculties of some of the

schools are exclusively Negro prove, by itself, violation

of Brown.

The presence of schools with student bodies consisting of stu-

dents of only one race is not a vestige of a dual system of schools.

The existence of schools with faculties composed of members of only

one race is not a vestige of a dual system of schools. The pres-

ence of these factors alone does not destroy the unitary non-

discriminatory character of a school system. These elements are

a natural result of human conduct and of the educational process

when it is maintained without regard to race and without discrimi-

- nation.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit in

Goss is supported by the following compilations assembled from

the statistical information filed with the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, which show the racial composition of

schools in the one hundred largest school districts in this nation

as of October 15, 1968... They were filéd by school districts under

the requirements of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

are upon Civil Rights Porms OS/CR 102-1 and OS/CR 101, Most of

these districts have never had a dual system of schools.

Assuming that a school with less than one percent of the minor-

ity race is an all-white or all-Negro school, of the 12,497 schools

10

in the one hundred largest school districts in the United States

6,137 schools are either all-white or all-Negro. Thus, more than

forty-eight percent of the schools in these districts are either

all-white or all-Negro. If is also found that in such districts

having as much as twenty percent or more Negro student enrollment,

only one district does not have within it all-Negro schools. This

is the Rochester, New York, Monroe County School District. In all the

consolidated cases at bar only one of the thirty districts has less

than twenty percent Negro student enrollment. Such student bodies

and faculties cannot be a "vestige of the dual system of schools".

They result from the natural process of education in a unitary,

non-racial school system:

Racial Composition

of Schools

Total Student All-Negro

Schools Body of Student Faculty of

District in Dist. One Race Body One Race

Chicago Public Schools,

Chicago, 111. 610 392 208 236

Indianapolis Public Schs.,

Indiana 11° 52 17 1

Des Moines Community

Schs., , Iowa 81 36 pe 52

Boston School Dept.,

Massachusetts 196 56 11 108

Detroit Public Schools,

Michigan 302 98 67 10

Special Sch, Dist, No. 1,

Minneapolis, Minn. 98 42 — 52

St. Touis City sch. Dist., ; :

Missouri 164 114 83 81

Kansas City School Dist.,

Missouri 99 43 19 14

-13=

(Continued)

District

Newark Public Schools

Newark, N.J.

Oklahoma City Public Sch.

Dist., 1-89, Okla,

Dallas Indep. Sch. Dist.,

Texas

Los Angeles School Dist.,

California

Sch. Dist. No. 1, City

&.Co..0f Denver, Colo.

District. of Columbia

Public Schools

Gary Community Schools,

Gary, Ind.

Cleveland, Ohio,

Cuyahoga Co.

New York City Public Schs.

New York, N.Y.

Houston Indep. Schools,

Houston, Texas

School Dist. of

Philadelphia, Pa.

Racial Composition

of Schools

Total Student All-Negro

Schools Body of Student Faculty of

in Dist, One Race Body One Race

80 27 27 3

115 71 15 5

173 117 26 149

591 359 65 229

116 54 3 32

118 114 114 26

45 25 21 6

180 115 57 38

B53 158 113 221

225 139 61 9

278 87 63 3

Broussard approved the Houston Independent School District as

being in compliance with constitutional requirements under a free-

dom of choice plan. According to its official report as of October

15, 1968, there then remained sixty-one all-Negro schools, seventy-

eight all-white schools, and there were nine schools with faculties

composed of members of one race.

-14~

¥.

THE PARTIES HAVE NOT BEEN ACCORDED DUE PROCESS OF LAW

We have generally adopted as a part of this petition for re-

hearing all matters set forth in the petition for rehearing Filed in

the other nineteen cases consolidated under Docket Number 28042. We

particularly adopt that portion thereof pointing out in detail how

the litigants have not been accorded due process of law. As detailed

therein, the Supreme Court of the United States considered on the Writ

of Certiorari only the order dated August 28. No issue was joined

concerning the plans filed on August 11 by the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare. They were neither before the Court nor con-

sidered by the Court. Hence such hearing does not affect in any manner

the total lack of due process of law in these cases.

CONCLUSION

We submit, with deference, that a rehearing should be granted

at which the Court would permit all litigants to be heard. 1n the

alternative, we strongly urge this Court to alleviate the condition

which is now destroying our system of public schools in this state.

The chaos and confusion is beyond description. Every public school

system here involved will suffer major and irreparable injury. There

is no way to determine the number which may be destroyed.

If the steps proposed by HEW as alternate or "interim" steps

were embodied in the terminal plan and permitted to be utilized as

proposed, we believe that most of these systems could be salvaged and

much of the injury and damage prevented. This would, of course, be a

major step by this Court. Yet we believe the public interest warrants

such action.

-15-~

Respectfully submitted,

[2 Eo Sunaas

JUDGE A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of

Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Re-

spondents, other than the

United States of America,

associated with other attor-

neys of record in each of the

Consolidated Cases.

IN BEHALF OF ALL ATTORNEYS OF

RECORD IN THE ABOVE STYLED CAUSES.

NOTES CONTAINING CASE REFERENCES

Griffin v. School Board,

Green v. County School Board,

Carr v. Montgomery Cty.,

Raney v. Gould, 391 U.S. 443,

377 U.S. 213, 12 1.Fd.24 256

391 U.S. 430

23 L..24.24 263, 3921 U.S. 443

20 1T..Pd.2d 727

Monroe v. City of Jackson, Tenn., 391 U.S. 450, 20 L.Fd.24 733

Goss v. Bd, of Ed.

Hall v. St. Helena Parish,

of ‘Knoxville, Tenn., 406 r.24 1183

287 P.24 376

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Petition for

Rehearing were served on the Plaintiff-Appellants and Intervenors

on this 20th day of November, 1969, by mailing copies of same,

postage prepaid, to their counsel of record at the last known

address as follows:

Melvyn R. Leventhal

Reuben V. Anderson

Fred L. Banks, Jr.

| John A. Nichols

538-1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Jack Greenberg

| James M. Nabrit, I11

| Norman C. Amaker

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Jeris Leonard

Assistant Attorney General

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

David L. Norman

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

Robert E. Hauberg

United States Attorney

Post Office Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

This the 20th day of November, 1969.

Of Counsel