Three Briefs on Proposition 14 in the California Supreme Court

Public Court Documents

June 11, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Three Briefs on Proposition 14 in the California Supreme Court, 1965. e82f319a-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/18aef2ca-8d47-4e73-bf88-698b73e9f4e9/three-briefs-on-proposition-14-in-the-california-supreme-court. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

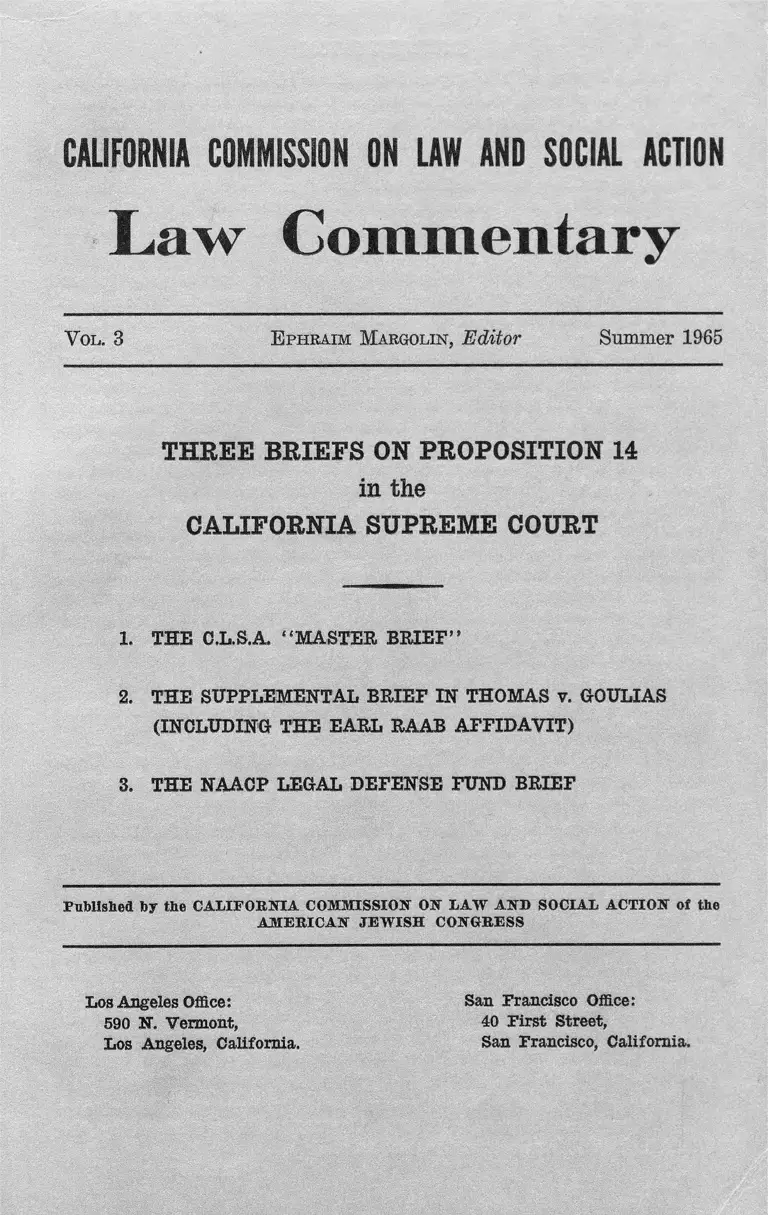

CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON LAW AND SOCIAL ACTION

Law Commentary

T H R E E B R I E F S O N P R O P O S IT IO N 14

in the

C A L I F O R N I A S U P R E M E C O U R T

1. THE C.L.S.A. “ MASTER BRIEF’ ’

2. THE SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF IN THOMAS v, GOULIAS

(INCLUDING THE EARL RAAB AFFIDAVIT)

3. THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND BRIEF

Publishes by the CALIFORN IA COMMISSION ON L A W AND SOCIAL ACTION o f the

A M ERICAN JEW ISH CONGRESS

Y ou 3 E p h r a im M argolin , Editor Summer 1965

Los Angeles Office:

590 N. Vermont,

Los Angeles, California.

San Francisco Office:

40 First Street,

San Francisco, California,

INTRODUCTION

In the Spring of 1964 when Proposition 14 was first brought to onr

attention,, members of the San Francisco Commission on Law and Social

Action initiated a series of meetings to discuss both the legal and the

social-action problems inherent in this proposition. Most of us became

active in the effort to fight it at the Polls. A short brief in Lewis vs.

Jordan, Sac. 7549, was filed on our behalf in the Supreme Court by

Warren Saltzman and Robert Laws, but the brief was limited to pro

cedural matters and did not undertake coverage of substantive con

stitutional issues.

Gradually, our group of attorneys, both in private practice and

from the University of California in Berkeley, grew to 20 or more.

Members of the American Civil Liberties Union, St. Thomas More

Society, and the NAACP were asked to join with us. More than a

dozen papers were commissioned from volunteers. In February 1965

five among us presented our tentative conclusions regarding the con

stitutionality of Proposition 14 at a special conference sponsored by

the National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing in coopera

tion with the University of California in Berkeley. This conference

climaxed a series of meetings in San Francisco and Los Angeles, in

which efforts were made to correlate legal work 'against the Proposition.

By February 1965 a number of us became attorneys of record in several

actions in which Proposition 14 was challenged and a draft of our

main brief wais ready for submission to a large number of sponsoring

organizations who indicated willingness1 to sign a “ Master Brief” prepared

by us. We are grateful to these organizations for their many comments

and suggestions and we wish to extend our special gratitude to Joseph

Robison of the C.L.S.A., to Sol Rabkin of the A.D.L., and to the National

Committee Against Discrimination in Housing.

In this issue of Law Commentary, we bring together the totality

of our legal effort regarding Proposition 14. We reprint the following

three briefs:

(1) The “ Master Brief” , partially financed by the National Com

mittee Against Discrimination in Housing, and partially by voluntary

contributions of a number of its California signatories.

(2) A brief financed by the American Civil Liberties Union of

Northern California, which supplements the “ Master Brief” and repro

duces a remarkable trial court affidavit by Earl David Raab.

(3) A brief financed by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and

limited to the Supremacy Clause argument.

We do not wish to give the impression that the three briefs reprinted

herein are the only briefs filed in the litigation concerning Proposition

14. Briefs of Redevelopment Agencies, the American Civil Liberties

Union of Southern California, Herman F. Selvin, Joseph A. Ball,

Nathaniel Colley and others are all of major importance in this litiga

tion. Under the covers of Law Commentary, however, we brought

together only those briefs for which we take a measure of credit.

We regret that the lack of space precludes the reprinting of any

other papers, memoranda or drafts of other work performed by the

C.L.S.A. in California over the last year.

The Editor

L . A . N os. 28360, 28422 and 28449

S. F . N os. 22019, 22020 and 22017

Sac. N o. 7657

In the Supreme Court

OF THE

State of California

L. A. No. 28360

LINCOLN W. MULKEY, et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

NEIL REITMAN, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Orange County

Honorable Raymond Thompson, Judge

AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF

Philip Adams, Beverly Axelrod, Richard A. Bancroft, Albert M.

Bendich, Herbert A. Bernhard, Lester Bise, Harry Bremond,

Ralph Evan Brown, Frank F. Chuman, J. K. Choy, Reynold H.

Colvin, Jay Darwin, John F. Dunlap, Maurice Engel, Basil

Feinberg, Andrew H. Field, Thomas L. Fike, Maxwell E. Green

berg, Allen J. Greenberg, Joseph R. Grodin, Dorothy E. Handy,

James K. Haynes, Bruce I. Hochman, Robert Holcomb, Harold

W . Horowitz, Norman C. Howard, Neil F. Horton, Tevis Jacobs,

Mathew M. Kearny, Herbert A. Leland, Jack Levine, David J.

Levy, Arthur L. Littleworth, Julian W . Mack II, Douglas

Maloney, James McDonald, Lloyd E. McMurray, Richard W .

Petherbridge, James C. Powers, Ralph H. Prince, Gerald Rosen,

Warren H. Saltzman, Edward Stern, Robert E. Sullivan, John

E. Thorne, Solomon Zeltzer, David Ziskind

Of Counsel-.

JOSEPH B. ROBISON

ROBERT M. O’NEIL

EPHRAIM MARGOLIN

683 McAllister Street

San Francisco, California 94102

By:

DUANE B. BEESON

Russ Building

San Francisco, California 94104

SEYMOUR FARBER

593 Market Street,

San Francisco, California 94105

ROBERT H. LAWS, JR.

646 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, California 94102

HOWARD NEMEROVSin

111 Sutter Street

San Francisco, California 94104

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

(Continued on Inside Cover)

L, A. No. 28422

WILFRED J. PRENDERGAST and CAROL A EVA PRENDERGAST, on

behalf of themselves and all persons similarly situated,

Gross-Defendants and Respondents,

vs.

CLARENCE SNYDER, Cross-Complainant and Appellant.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

L. A. No. 28449

THOMAS ROY PEYTON, M.D., , Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

BARRINGTON PLAZA CORPORATION, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

CLIFTON HILL,

CRAWFORD MILLER,

Sac. No. 7657

vs.

Plaintiff and Appellant,

Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Sacramento County

Honorable William Gallagher, Judge

S. P. No. 22019

DORIS R. THOMAS, Plaintiff wnd Appellant,

vs.

G. E. GOULIAS, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge .

S. F. No. 22020

JOYCE GROGAN, Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

ERICH MEYER, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

S. F. No. 22017

REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF FRESNO, a public body,

corporate and politic, Petitioner,

vs.

KARL BUCKMAN, Chairman of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of

Fresno, Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Mandate

Subject index

Interest of Amici .......................................................................... 3

I. Introductory statement ...................................................... 8

II. Discrimination in housing against members of minority

groups exists on a substantial scale in California and

has widespread harmful effects ........................................... 10

A. The existence of racial discrimination in housing in

California................... 10

B. The harmful effects of residential segregation in

California .................................... 13

III. The development of California law in the field of racial

discrimination and the impact of Article I, Section 26,

of the Constitution ............. 21

A. The legislative and judicial response to discrimina

tory practices ................................. - ......................... • 21

1. California legislation prior to 1959 .................... 21

2. 1959 legislation—the Unruh, Hawkins and Pair

Employment Practice Acts ............................. . • 24

3. Legislation subsequent to 1959 ............................. .26

4. Development of California antidiscrimination

common la w .................................................. 28

B. The impact of Article I, Section 26, on California

law ................................ 32

1. The effect on the Branford Act ......................... 32

2. The effect on the Unruh A c t ............................... 33

3. The effect on the development of California

common law ........................................................... 34

4. The effect on future legislative regulation......... 35

Page

S u bject I ndex

IV. Article I, Section 26 constitutes discriminatory state

action within the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the United States Constitution ................................... 36

A. The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits state action

in furtherance of racial discrimination in the sale

and rental of real property ........... ................. . 36

1. Private discrimination on state-owned property 38

2. Private discrimination in the operation of prop

erty under state-assistance programs ............ 39

3. Private discrimination in the management of

property utilized in a quasi-public function . . . 41

4. Private discrimination where the state has dele

gated a governmental function ......................... 41

5. Private discrimination authorized, sanctioned or

encouraged by the state ............................. .. . . . 43

B. There is sufficient state encouragement of racial

discrimination under Article I, Section 26 to bring

it within the proscription of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ............. 47

C. The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits California

from disabling itself from dealing with matters of

fundamental government concern ........................... 54

V. Article I, Section 26 constitutes an unconstitutional im

pairment of the right to petition the government for

redress of grievances ........................................ 58

VI. The constitutional defects in Article I, Section 26

render it completely void ................................................. 62

Conclusion .................................... 65

ii

Page

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

Abstract Investment Co. v. Hutchison, 204 CaI.App.2d 242

(1962) 45,49

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964)............................. 45,49

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 12 L.ed. 2d 992 (1 9 6 4 ).... 64

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F.2d 750 (C.A. 5, 1961).................. 45

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953)......................... 45,48,51

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1946)................................... 43

Bowman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F.2d 531

(C.A. 5, 1960) .........................................................................47,49

Brotherhood of R. Trainmen v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1 (1964) 58, 59

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917)............................... 36

Burks v. Poppy Construction Co., 57 Cal.2d 463 (1962)

....................... 31,33,35,56

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) 38,40,46,47

Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106 (1940)............................. 64

City of Greensborough v, Simpkins, 246 F.2d 425 (C.A. 4,

1957) 39

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)..............................42,43,58

Darlington v. Plumber, 240 F.2d 922 (C.A. 5, 1956), cert.

denied, 353 U.S. 924................................................................

Department of Conservation & Dev. v. Tate, 231 F.2d 615

(C.A. 4, 1955), cert, denied, 352 U.S. 838.........................

Dorsey v. Styvesant Town Corp., 299 N.Y. 512 (1949), cert,

denied, 339 U.S. 981..............................................................

Eastern R. Conf. v. Noerr Motors, 365 U.S. 127 (1961). , . . 58

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F.2d 710 (C.A. 4, 1964)...................... 40

Eisentrager v. Forrestal, 174 F.2d 961 (1949), reversed on

other grounds, 339 U.S. 763 (1950)............... ..................... 57

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)........................ 53

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)........................ 53

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)........................ 53

Home Bldg. & Loan Assoc, v. Blaisdell, 290 U.S. 398 (1934) 57

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948)........................................ 44

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal.2d 876

(1963) ..................................................................................... 56

39

39

40

IV T able of A uthorities, Cited

James v. Marinship Corp., 25.Cal.2d 721 (1944)..................28,41

Johnson,v. Levitt & Son, 131 F.Supp. 114 (E.D. Pa. 1955) 40

Pages

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1 9 3 9 )................................. .. 53

Lynch v. United States, 189 F.2d 476 (C.A. 5, 1951)........ .. 42

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946)................................. 41

McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. By., 235 U.S. 151 (1914).. .46, 49

Ming v. Horgan (Cal. Super. Ct. 1958), 3 Race Relations

L. Repts. 693 ......................................................................... 40

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932).....................................42,49

Orloff v. Los Angeles Turf Club, 30 Cal.2d 734 (1 9 5 1 ).... 31

Piluso v. Spenser, 36 Cal.App. 416 (1918)............................. 31

Reuter v. Board of Supervisors, 220 Cal. 314 (1 9 3 4 ) . . . . . . 52

San Mateo v. Railroad Commission, 9 Cal.2d 1 ..................... 52

Schwartz-Torran.ce Investment Corp. v. Bakery Local 31, 61

Cal.2d 766 ( 1 9 6 4 ) . . . . . . . . ..................................................... 41

Second Slaughter House Case, Butchers’ Union Co. v. Cres

cent City Co., I l l U.S. 746 (1883)................................. 57, 58, 61

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)................. 37,43,44,46,48

Simpkins v. Moses II. Cohn Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d

959 (C.A. 4, 1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S. 938................. 39

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1872)..........58, 59

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944),................................. 42

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 (1959)............................. 63

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F.2d 630 (C.A.

6, 1964) .................................................................................. 40

State Compensation Fund v. Riley, 9 Cal.2d 126 (1 9 3 7 ).... 52

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)..................................... 42

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947)......................................... 57

Thomas v. Goulias, No. SF 22019............................................. 12

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940)............................. 64

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876)................. 59

United States v. Hall, 26 Fed.Cas. 79 (C.C.S.D. Ala. 1871) 43

Williams v. Boilermakers, 27 Cal.2d 586 (1946)................... 30

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964)............................. 53

Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944)........................... 57

Codes

Civil Code: Page

Section 51 ............................. 24

Sections 51-54 ...................................................................... 21

Section 52 ........................................................................... 24

Section 53 ........ 27

Section 69 ............................ 27

Section 782 ......................................................................... 27

Education Code:

Section 8451 ........................................................................ 22

Section 8452 ........................................................................ 22

Section 13274 ...................................................................... 23

; Section 13732 .............................................. 22

Election Code:

Section 223 .......................................................................... 27

Government Code:

Section 8400 ............. 28

Section 10702 .................................................................. 22

Section 19704 ...................................................................... 22

Health and Safety Code:

Section 33039 ...................................................................... 27

Section 33050 .......................................... 26

Sections 35700-35741 ........................................................... 25

Sections 35700-35744 ................. 28

Insurance Code:

Section 11628 .................................................. 23

Labor Code:

Section 177.6 ........................................................................ 23

Sections 1410-1432 .............................................................. 25

Section 1412 ........................................................................ 26

Section 1735 ................................... 22

Military and Veterans Code:

Section 130 ..................... 23

Penal Code:

Section 365 ........................... ........... .............................. • • 21

Welfare and Institutions Code:

Section 19 ............................................................................ 22

Table op A uthorities Cited v

Constitutions

California Constitution: Pages

Article I, Section 10 ........................................................... 60

Ai’ticle I, Section 26 ......................................................... passim

United States Constitution, 14th Amendment ......................

........................................................ 8,10, 36, 38, 42, 43, 54, 55, 58, 60

Statutes

Cal. Stats. 1893, c. 185, p. 220 ................................................ 21

Cal. Stats. 1919, c. 210, p. 309 ................................................ 21

Cal. Stats. 1923, c. 235, p. 485 ............... 21

Cal. Stats. 1925, c. 276, p. 460, Sec. 2 ...................................... 22

Cal. Stats. 1935, c. 618, pp. 1748-1749, Sec. 5.798 as amended 22

Cal. Stats. 1937, c. 753, p. 2110, Sec. 201.................................. 22

Cal. Stats. 1939, c. 643, p. 2068, Sec. 1 ............................. 22

Cal. Stats. 1941, c. 243, p. 1308, Sec. 1 ..................................... 22

Cal. Stats. 1941, c. 1192, p. 3005, Sec. 1 ........................ 23

Cal. Stats. 1947, c. 161, p. 690, Sec. 1 .............................. 22

Cal. Stats. 1949, c. 948, p. 1720, Sec. 1 ..................... 23

Cal. Stats. 1949, c. 1578, p. 2826 ................... 23

Cal. Stats. 1951, c. 1718, p. 4038, Sec. 2 .................................. 22

Cal. Stats. 1955, c. 125, p. 588, Sec. 1 .............................. 23

Cal. Stats. 1955, c. 1910, p. 3519 ........... 23

Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 121, p. 1999, Sec. 1....................... 25

Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1102, p. 3182, Sec. 23.................................. 26

Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1681, pp. 4074-4077 .................................... 25

Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 554, p. 1665, Sec, 2 ............................... 27

Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 1078, p. 2810, Sec. 1 27

Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 1877, p. 3976, Sec. 1 .................................. 27

vi Table oe A uthorities Cited

Table of A uthorities Cited

Cal. Stats. 1961, e. 1898, p. 4008, Sec. 1 .................................. 27

Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 2116, p. 4377, Sec. 1 ........................ 27

Cal. Stats. 1963, c. 1853, p. 3823, Sec. 2 .................................. 28

Attorney General’s Opinions

9 Ops. Cal. At.ty. Gen. 271, 274 ................................................. 31

Texts

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors, pp. 70-81, 137-149, 150-190,

227-243 (1955) ........................................................................ 11

A New Look at State Action, Equal Protection and “ Pri

vate” Racial Discrimination, 59 Mich. L. Rev. 993 (1961) 38

Brown, The Right to Petition, 8 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. (1961) :

Page 729 ................................... 59,60

Page 732 .................................... 59

Clark, Prejudice and Your Child (1955), pp. 39-40 ............ 15

Comment, The Impact of Shelley v. Kraemer on the State

Action Concept, 44 Cal. L. Rev. 718 (1956)....................... 38

Comment, The Rumford Fair Housing Act Reviewed, 37

U.S.C. L. Rev. 427, 430, 432 (1964)..................................... 21

Frank & Monro, The Original Understanding of “ Equal

Protection of the Laws,” 50 Colum, L. Rev. 131 (1950).. 43

Groner & Helfeld, Race Discrimination in Housing, 57 Yale

L. J. 426, 428-429 (1948) ..................................................... 17

Horowitz, California Equal Rights Statute, 33 LT.S.C. L. Rev.

260-264 (1960) ............................... ...............................••••• 21

Horowitz, The Misleading Search for “ State Action” under

the Fourteenth Amendment, 37 Cal. L. Rev. 208 (1957) 38

Kaplan, Discrimination in California Housing: The Need for

Additional Legislaiton, 50 Cal. L. Rev. 635, 636 (1962).. 21

vii

Pages

Table of A uthorities Cited

Karst & Van Alstyne, Sit-Ins and State Action, 14 Stan. L.

Rev. 762 (1962) ...................................................................... 38

Klein, The California Equal Rights Statutes in Practice, 10

Stanford L. Rev. (1958) :

Pages 253, 255-259 ............................................................... 21,31

Pages 270-272 ...................................................................... 31

Lewis, The Meaning of State Action, 60 Colum. L. Rev. 1083

(1960) ...................................................................................... 38

Maslaw, De Facto Public School Segregation, 6 Vill. L. Rev.

353, 354-355 (1961) .............................................. 19

McEntire, Residence and Race (1960), pp. 32-67, 61-66 . . . . 12

Miller, An Affirmative Thrust to Due Process of Law, 30

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 399 (1962)................................................ 43

Myrdal, An American Dilemma. (1944) :

Page 6 1 8 ................................................................................ 19

Pages 618-627 ......................... 11

Note, Civil Rights: Extent of California Statute and Reme

dies Available for Its Enforcement, 30 Cal. L. Rev. 563-565

(1942) ........................................................................................ 21

Peters, Civil Rights and State Non-Action, 34 Notre Dame

Law 303 (1959) ...................................................................... 43

Shanks, “ State Action” and the Girard Estate Case, 105 U.

Pa. L. Rev. 213 (1956) ............................. 38

St. Antoine, Color Blindness But Not Myopia ....................... 38

Williams, The Twilight of State Action, 41 Tex. L. R. 347

(1963) ......................................................................... 38

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948) ........................................... 11

viii

Pages

Table of A uthorities Cited ix

Miscellaneous Pasfe

Editorial, Vol. XLIV, No. 2, California Real Estate Maga

zine (Dec. 1963) .................................................................... 52

N.Y. State Commission Against Discrimination, In Search of

Housing, A Study of Experiences of Negro Professional

and Technical Personnel in New York State (1959)......... 19

Report of Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall

We Live? (1958) :

Pages 1-10 ........................................ 11

Page 3 .................................................................................. 13

Pages 35-36 .......................................................................... 19

Pages 5, 36-38 ...................................................................... 17

Page 36 ................................................................................ 14

Page 40 ................................................................................ 18

Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Se

cure These Rights (1947) :

Pages 67-70 .......................................................................... 11

Pages 82-87 .......................................................................... 20

Report of U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Book 4, Hous

ing, p. 1 (1961) ...................................................................... 11

Report of U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1959) :

Pages 336-374 ...................................................................... 11

Page 3 9 1 ................................................................................ 15

Page 392 ................................................................................ 17

Page 545 ................................................................................ 19

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “ 50 States Report” (1961) :

Pages 43-46 .......................................................................... 11

Page 45 ................................................................ 18

U.S. Commission on Race and Housing, 1959 Report, p. 278 14

L. A. Nos. 28360, 28422 and 28449

S. F. Nos. 22019, 22020 and 22017

Sac. No. 7657

In the Supreme Court

OF THE

State of California

L. A. No. 28360

LINCOLN W. MULKEY, et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs,

NEIL REITMAN, et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Orange County

Honorable Raymond Thompson, Judge

L. A. No. 28422

WILFRED J. PRENDERGAST and CAROLA EVA PRENDERGAST, on

behalf of themselves and all persons similarly situated,

Cross-Defendants and Respondents,

vs.

CLARENCE SNYDER, Cross-Complainant and Appellant.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

L. A. No. 28449

THOMAS ROY PEYTON, M.D., Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

BARRINGTON PLAZA CORPORATION, Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Los Angeles County

Honorable Martin Katz, Judge

CLIFTON HILL,

CRAWFORD MILLER,

Sac. No. 7657

vs.

Plaintiff and Appellant,

Defendant and Respondent.

Appeal from the Superior Court of Sacramento County

Honorable William Gallagher, Judge

2

DORIS R. THOMAS,

G. E. GOULIAS, et al.,

S. P. No. 22019

vs.

Plaintiff and Appellant,

Defendants and Respondents.

Appeal from the Municipal Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

Honorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

JOYCE GROGAN,

ERICH MEYER,

S. !•’. No. 22020

V S i

Plaintiff and Appellant,

Defendant and Respondent.

.av. i ; . ̂ P-peal,, from the Municipal. Court of the

City and County of San Francisco

''Hl'OTiorable Robert J. Drewes, Judge; Honorable Leland J.

Lazarus, Judge, and Honorable Lawrence S. Mana, Judge

S. F. No. 22017

REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF FRESNO, a public body,

corporate and politic, Petitioner,

■ vs. . . . .

KA.B^,BUCKM4N, Chairman of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of

Fresno, Respondent.

: Petition for Writ of Mandate

AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF

Philip Adams, Beverly Axelrod, Richard A. Bancroft, Albert M.

Bendich, Herbert A. Bernhard, Lester Bise, Harry Bremond,

Ralph Evan Brown, Frank F. Chuman, J. K. Choy, Reynold H,

Golvin, Jay Darwin, John F. Dunlap, Maurice Engel, Basil

Feinberg, Andrew H. Field, Thomas L. Fike, Maxwell E. Green

berg, Allen J. Greenberg, Joseph R. Grodin, Dorothy E. Handy,

James K. Haynes, Bruce I. Hochman, Robert Holcomb, Harold

W . Horowitz, Norman C. Howard, Neil F. Horton, Tevis Jacobs,

Mathew M. Kearny, Herbert A. Leland, Jack Levine, David J.

Levy, Arthur L. Littleworth, Julian W . Mack II, Douglas

Maloney, James McDonald, Lloyd E. McMurray, Richard W .

Eetherbridge, James C, Powers, Ralph H. Prince, Gerald Rosen,

Warren H. Saltzman, Edward Stern, Robert E. Sullivan, John

E, Thome, Solomon Zeltzer, David Ziskind

3

INTEREST OF AMICI

The California attorneys submitting this brief as

amici curiae . represent various organizations con

cerned with discrimination based on race, religion or

national origin. These organizations include:

1. National Committee Against Discrimination in

Housing and its Affiliated Organizations:

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America,

AFL-CIO

American Baptist Convention, Division of Chris

tian Social Concern

American Civil Liberties Union

American Council on Human Rights

American Ethical Union

American Friends Service Committee

American Jewish Committee

American Jewish Congress

American Newspaper Guild, AFL-CIO

American Veterans Committee

Americans for Democratic Action

Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters,

AFL-CIO/CLC

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Department of

Labor, Migration Division

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)

Cooperative League of the USA

Friendship House

Industrial Union Department, AFL-CIO

4

International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union,

AFL-CIO

International Union of Electrical, Radio and Ma

chine Workers, APL-CIO

Jewish Labor Committee

League for Industrial Democracy

The Methodist Church, Woman’s Division of

Christian Service

National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People (NAACP)

National Association of Negro Business and Pro

fessional Women’s Clubs

National Catholic Conference for Interracial Jus

tice

National Coimcil of Churches of Christ, Depart

ment of Ethical and Cultural Relations

National Council of Jewish Women

National Council of Negro Women

National Urban League

Protestant Episcopal Church, Department of

Christian Social Relations

Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Com

mission on Social Action

Unitarian Fellowship for Social Justice

United Auto Workers of America, APL-CIO

United Church of Christ, Council for Social Ac

tion, and Race Relations Department, Board of

Homeland Ministries

United Presbyterian Church, Board of Christian

Education

United Steelworkers of America, APL-CIO

5

2. and tlie following California organizations:

The American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO,

California Division

American Friends Service Committee, California

Offices

American Jewish Congress, California Divisions

American Jewish Committee, Los Angeles and

San Francisco Chapters

Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith, Central

Pacific Region

Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith, Pacific

Southwest Region

Bay Area Urban League, Inc.

California Committee for Fair Practices

California League for American Indians

Catholic Inter-Racial Councils and Human Rela

tions Councils of California

City of San Bernardino

Community Relations Committee, Jewish Welfare

Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles

C.O.R.E. (Western Region)

East Bay Conference on Religion and Race

Episcopal Diocese of California

Fair Housing Council of San Mateo County

First Unitarian Church of San Francisco

Friends Committee on Legislation of Southern

California

Golden Gate Chapter, National Association of

Social Workers

6

Hitman Relations Council of Riverside, Execu

tive Board

Human Relations Commission of San Bernardino

Interfaith Social Action Council of San Bernar

dino

Japanese American Citizens League

Jewish Community Relations Council of San

Francisco, the Peninsula and Marin

Jewish Community Relations Council for Ala

meda and Contra Costa Counties

Jewish Community Relations Council of San Jose

Jewish Labor Committee

Jewish W ar Veterans, California Department

Los Angeles Cloak Joint Board, ILGW U

Marin Committee for Fair Play

Marin Conference on Religion and Race

Marin County Human Rights Commission

NAACP, San Francisco Branch

Rapa County Human Relations Council

Orinda Council for Civic Unity

Palo Alto Fair Play Council

Pasadena Young Women’s Christian Association

Pittsburg Human Relations Commission

San Bernardino Leadership Council

San Francisco Conference on Religion and Race

San Francisco Friends of Student Non-Violent

Coordinating Committee

San Francisco Greater Chinatown Community

Service Association

7

San Francisco Young Women’s Christian Asso

ciation

San Jose Human Relations Commission

Social Action Committee, First Congregational

Church, Riverside

Union of American Hebrew Congregations

Universalist Unitarian Church of Riverside,

Board of Trustees

The foregoing organizations are committed to the

proposition that discrimination based on race, religion

or national origin is a major evil, both nationally and

in California, and that the effects of such discrimina

tion are particularly invidious in the field of housing.

The organizations have long been actively concerned

with the malignant growth and persistence of racial

ghettos in the residential areas of California and the

United States, and their pernicious social, educational

and economic consequences.

The interest of Amici in these cases is limited to

the question of the validity under the federal consti

tution of Article I, Section 26, of the California con

stitution, which became law following enactment as

Initiative Proposition No. 14 in the general election

of November 3, 1964.1 It is the position of Amici that

the new constitutional amendment encourages, sanc

tions, and unmistakeably places the state’s imprimatur

on discriminations based on race, religion and na

tional origin in the transfer of real property interests;

irThe briefs of the parties before the Court present full state

ments of the facts and proceedings below which in our judgment

necessarily present the broad constitutional issues.

8

and that the amendment arbitrarily precludes any

exercise of state power to redress private discrimina

tion in the sale and leasing of real property. Amici

submit that on these grounds Article I, Section 26, of

the California Constitution violates the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution, and is

therefore void.

I. INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT.

The gravamen of the newly enacted Article I, Sec

tion 26, of the California Constitution is contained

in the following clause:

“Neither the State nor any subdivision or agency

thereof shall deny, limit or abridge, directly or

indirectly, the right of any person, who is willing

or desires to sell, lease or rent any part or all

of his real property, to decline to sell, lease or

rent such property to such person or persons as

he, in his absolute discretion, chooses.”

The language is, on its face, general and unqualified.

No effort is made to catalogue the considerations

which the amendment would immunize against state

regulation or prohibition in a landowner’s deter

mination to withhold property from particular in

dividuals. Rather, by vesting “ absolute discretion” in

the property owner with respect to the disposition of

his property, the amendment attempts to sweep within

the pale of state constitutional protection both rea

sonable and unreasonable motivations, ethical and

unethical considerations, licit and illicit reasons for

selecting and rejecting willing buyers and renters.

9

The major impact of the amendment falls only

upon members of minority groups. A constitutional

amendment was not needed to permit property owners

to withhold a leasehold from lessees with pets, to

withhold property in a senior citizens’ community

from purchasers who do not meet an age requirement,

or to withhold property for any number of considera

tions under commonly accepted tenets of desirable

social arid economic behavior. However, in recent

years the withholding of real property on purely

racial or religious grounds has been made the occa

sion for legal redress in California, and there is little

doubt that Article I, Section 26, was proposed and

passed for the precise objective of granting and

guaranteeing the right to discriminate on racial and

religious grounds in the selling and leasing of real

property. See infra, pp. 21-32.

The language of the amendment achieves that pur

pose. Under the “ absolute discretion” phraseology, a

Mexican seeking a home for his family in Los Angeles

may be turned away because of his national origin

by an owner whose house is on the market; a Japanese

farmer may be denied farmland in the San Joaquin

Valley because he is not Caucasian, and a Negro in

San Francisco may be told that he cannot rent an

apartment because of the color of his skin. In those

instances, the amendment undeniably would sanction

discrimination.

It is the position of Amici that Article I, Section

26, of the California constitution, by granting the

protection of law to those who discriminate against

10

minority citizens seeking to acquire property interests,

by withholding redress of law from those who suffer

such discrimination, and by arbitrarily precluding the

effective exercise of state power to regulate discrimi

nation in the transfer of real property, is in direct

conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution. W e develop the reasons which

compel this conclusion in succeeding portions of the

brief.

A proper evaluation, however, of the impact of the

amendment in the area of personal rights covered

by the Fourteenth Amendment requires initially a

discussion of the extent of discriminatory practices

in California and of the present laws which deal with

those practices.

II. DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING- AGAINST MEMBERS OF

MINORITY GROUPS EXISTS ON A SUBSTANTIAL SCALE IN

CALIFORNIA AND HAS WIDESPREAD HARMFUL EFFECTS.

The ghetto pattern that dominates residential areas

throughout the United States—and in California—has

been revealed in every study made of the subject—

whether by public agencies or by private institutions.

Its harmful effects are well known.

A. The Existence of Racial Discrimination in Housing1 in Cali

fornia.

That racial discrimination in housing exists through

out the United States and in California need not be

belabored.

11

In 1961, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights ob

served :2

In 1959 the Commission found that “ housing

. . . seems to be the one commodity in the Ameri

can market that is not freely available on equal

terms to everyone who can afford to pay.” Today,

2 years later, the situation is not noticeably bet

ter.

Throughout the country large groups of Ameri

can citizens—mainly Negroes, but other minorities

too-—are denied an equal opportunity to choose

where they will. live. Much of the housing market

is closed to them for reasons unrelated to their

personal worth or ability to pay. New housing,

by and large, is available only to whites. And in

the restricted market that is open to them, Ne-

groes generally must pay more for equivalent

housing than do the favored majority. “ The dol

lar in a dark hand” does not “ have the same

. purchasing power as a dollar in a white hand.”

And the California Advisory Committee to the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights has reported:3

. The State of California has a large and increas-

■, ing Negro population. These people live mainly in

segregated patterns in the major urban centers

of the State. In most cases, Negro housing areas

-Keport o f the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Book 4, Hous

ing, p. 1 (1961). See, also, Report of the President’s Committee

on Civil Rights, To Secure These Bights, pp. 67-70 (1947) ; Myrdal,

An American Dilemma, pp. 618-27 (1944) ; Weaver, The Negro

Ghetto (1948); Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors, pp. 70-81, 137-49,

150-190, 227-243 (1955); Commission on Race and. Housing,

Where Shall We Live?, pp. 1-10 (1958); Report of the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, pp. 336-374 (1959).

3U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, “ 50 States Report” , pp. 43-

46 (1961).

12

are considerably less attractive than housing in

other areas.

* * * * *

As California’s Negro population increases,

pressure builds up in the great urban ghettos, and

slowly but perceptibly the segregated areas en

large. The Committee found that, as a general

rule, Negro families do not move individually

throughout the community. They move as a group.

This, is true in most cases of the relatively high-

wage Negro professional group. It is practically

universally true of Negroes in the lower mass

group.

* * * * *

This Negro housing problem is widespread.

Negroes encounter discrimination not only where

houses in subdi visions and in white neighborhoods

are concerned but also in regard to trailer parks

and motels. Testimony received by the Committee

indicated that the trailer-park situation is par

ticularly acute and that, especially in the southern

part of the State, few, if any, trailer parks will

accept Negroes.4

Unquestionably there is an established pattern of

segregation in housing, and in the sale and rental of

real estate in California.5

4The existence of housing bias in California’s two principal

metropolitan areas is further documented in McEntire, Residence

and Race (I960), in a chapter (pp. 32-67) studying residential

patterns in 12 large cities representing the major regions of the

country, including Los Angeles and San, Francisco. See particu

larly the maps showing racial concentration in those two cities,

pp. 61-66.

BIn this connection, we refer the Court also to the uncontra

dicted affidavit of Earl Raab which is part of the record in

Thomas v. Goulias, No. S F 22019, pending in this Court.

B. The Harmful Effects of Residential Segregation in California.

Because of the pervasive nature of discrimination

in housing, we have in effect two housing markets,

one for whites and one for non-whites. Its oppressive

effects on the direct victims of discrimination and on

the interests of the state as a whole are readily

demonstrated.

1. The most obvious price paid by those who are

discriminated against is a loss of freedom. “ The

opportunity to compete for the housing of one’s choice

is crucial to both equality and freedom,” declares the

Commission on Race and Housing.6

Within their financial limits, majority groups in

America are free to choose their homes on the basis

of a number of factors germane to their pursuit of

happiness: the size of house needed to accommodate

the family; preferences for particular styles of hous

ing or kinds of neighborhoods; the availability of

community facilities such as churches, schools, play

grounds, clubs, shopping, and transportation.

This freedom of choice is denied members of minor

ity groups. Granted the means, a non-white person

may buy any automobile, any furniture, any clothing,

any food, any article of luxury offered for sale. But

it is not possible for a non-white American to bargain

freely, in an open, competitive market, for the home

of his choice, regardless of his intellect, integrity or

wealth.

6Report of Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall We

Live?, p. 3 (1958).

14

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, referring to

the “ White noose around the city,” has said:7

There may be relatively few Negroes able to

afford a home in the suburbs, and only some of

these would want such homes, but the fact is that

this alternative is generally closed to them. It is,

this shutting of the door of opportunity open to

other Americans, this confinement behind invisible

lines, that makes Negroes call their residential

areas a ghetto.

Housing discrimination also abridges the right of

the majority group owner freely to sell or rent his

property. The mechanics of the dual, segregated hous

ing market restrict the universe within which the

white seller may find prospective purchasers. For

practical purposes he may offer his house to whites or

to Negroes, but not to both.

2. Housing discrimination imposes a heavy eco

nomic penalty on the Negro. As the U.S. Commission

on Civil Rights pointed out in the portion of its 1961

Report quoted above, “ Negroes generally must pay

more for equivalent housing than do the favored

majority.” 8 This is because the discriminatory prac

tices that hold down the supply of housing available

to Negroes inevitably raise the price or rent they

must pay.

7Oommission on Race and Housing, 1959 Report, p. 278.

Similarly, the Commission on Race and Housing, in its Report,

Where Shall We Live? (1958), p. 36, said: “ . . . segregated groups

receive less housing value, for their dollars spent than do whites,

by a wide margin.”

15

McEntire, after reviewing all past studies as well

as those conducted for the Commission on Race and

Housing, concludes :9

Racial differences in the relation of housing

equality and space to rent or value can be briefly

summarized. As of 1950, nonwhite households,

both renters and owners, obtained a poorer quality

of housing than did whites at all levels of rent or

value, in all regions of the country. Nonwhite

homeowners had better quality dwellings than

renters and approached more closely to the wThite

standard, but a significant differential persisted,

nevertheless, in most metropolitan areas and value

classes. . . .

3. Other, less tangible, injuries are inflicted on the

victims of discrimination in housing, with resultant

evil effects on the state itself.10 “ AH of our community

institutions reflect the pattern of housing,” the presi

dent of the Protestant Council of New York has

stated. “ It is indescribable, the amount of frustration

and bitterness, sometimes carefully shielded, but the

anger and resentment in these areas can scarcely be

overestimated and can hardly be described; and this

kind of bitterness is bound to seep, as it has already

seeped, but increasingly, into our whole body politic.”

He said he could “ think of nothing that is more

dangerous to the nation’s health, moral health as well

as physical health, than the matter of these ghettos.” 11

. -'Op. cit. supra, p. 155.

10See, in particular, Clark, Prejudice and Your Child (1955),

pp. 39-40.

11U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Report, p. 391.

16

Residential discrimination and segregation impede

the social progress and job opportunities of minority

groups, and deprive the whole community of the con

tributions these Americans might otherwise make. It

is questionable whether we can fully comprehend the

enormous harm to the individual and to the com

munity in terms of waste of human and economic re

sources.

4. Perhaps the most notorious effect of the ghetto

system is its creation of slums, with all their attendant

evils—to the slum dweller and to the public weal. As

we have seen, housing bias compels non-white groups

to live in the restricted areas available to them. The

excessive density of population resulting from the

artificially limited supply is a classic cause of slums,

which in turn breed delinquency, vice, crime and

disease.

Thus, in 1959, the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights

described the effects of residential discrimination as

follows. “ The effect of slums, discrimination and in

equalities is more slums, discrimination and inequali

ties. Prejudice feeds on the conditions caused by

prejudice. Restricted shun living produces demoral

ized human beings—and their demoralization then be

comes a reason for ‘ keeping them in their place’ . . . .

Not only are children denied opportunities but the

city and nation are deprived o f their talents and pro

ductive power.” The Commission reported that a

former Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare

estimated the national economic loss at 30 million dol

lars a year, representing the diminution in productive

17

power of those who by virtue of the inferior status

imposed upon them were unable to produce their full

potential.12

Two years later, the Commission reiterated its con

clusion and added: “ These problems are not limited

to any one region of the country. They are nationwide

and their implications are manifold . . .” 13

5. The racial patterns of the slums resulting from

housing bias severely distort programs of slum clear

ance and urban renewal. The price paid for these

civic improvements, in terms of forced moves and

disrupted lives, is often borne most heavily by the

minority families that live in the cleared areas.

The problem has been fully described by the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights.14 It points out that

minorities are frequently the principal inhabitants of

the areas selected for slum clearance or urban re

newal.15 But each of these programs depends for

success on the ability to relocate some or all of the

slum dwellers. Urban renewal obviously contemplates

12U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Report, p. 392; Com

mission on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 5, 36-38; Groner

& Helfeld, Race Discrimination in Housing, 57 Yale L.J. 426,

428-9 (1948).

13U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Report, Book 4,

“ Housing,” p. 1. See also MeEntire, op. cit. supra, pp. 93-94.

14U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Report, Book 4,

“ Housing,” c. 4. “ Urban Renewal,” especially pp. 82-83. See also

Commission on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 37-40.

15From the beginning of the Federal urban renewal program in

1949 up to 1960, slum clearance and urban renewal projects had

relocated 85,000 families. Of the 61,200 families whose color is

known, 69% were non-white. Housing & Home Finance Agency,

Relocation from Urban Renewal Project Areas through June 1960,

p. 7 (1961).

18

the destruction of obsolete slum buildings, and these

residents must of course move. And if they are simply

moved to another segregated area, adding to its popu

lation densities, a new slum is created. In those cir

cumstances the renewal program represents much

motion but little movement.

As Albert M. Cole, former Federal Housing and

Home Finance Administrator, has said :16

Regardless of what measures are provided or

developed to clear slums and meet low-income

housing needs, the critical factor in the situation

which must be met is the fact of racial exclusion

from the greater and better part of our housing

supply. . . . Ho program of housing or urban im

provement, however well conceived, well financed,

or comprehensive, can hope to make more than

indifferent progress until we open up adequate

opportunities to minority families for decent

housing.

The California Advisory Committee to the IT. S.

Commission on Civil Rights discovered these phe

nomena in full effect in this state, with clearly visible

harm to the Negro population. It reported:17

The Committee found that concentration of

Negro families into certain specified areas within

California cities seems to be augmented, rather

than alleviated, by urban renewal projects. It

appears that Negroes displaced by such projects

18“ What is the Federal Government’s Role in Housing?” Ad

dress to the Economic Club of Detroit, Feb. 8, 1954, quoted in

Report of the Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall We

Live?, p. 40 (1958).

1750 States Report, supra, p. 45.

19

tend to find alternative housing in pre-existing

ISTegro sections. There seems to be little effort to

guide displaced families in their selection of

homesites. The project moves forward and Negro

f amilies, along with other groups, must quickly

find new homes. More often than not, these Negro

families settle in adjacent ghettos already in

existence.

As the proportion of minority group members

is extremely high in the so-called “ blighted areas”

of our State’s larger cities, this is a major prob

lem for those concerned with civil rights and

minority housing.

6. The harmful effects of residential segregation

are not limited to housing. A conspicuous feature of

the ghetto system is its tendency to produce segrega

tion in education and all other aspects of our daily

lives.18 It is primarily responsible for the wide

spread segregation that hampers Negroes and persons

of Puerto Rican and Mexican origin in urban public

schools.19 It has even impaired the job opportunities

opened up by fair employment laws.20

One of the most disturbing features of the physical

pattern of segregation, whether in housing or other-

18Myrdal, An American Dilemma, p. 618 (1944); Commission

on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 35-36.

19Maslow, De Facto Public School Segregation, 6 Vill. L. Rev.

353, 354-5 (1961). In its 1959 Report, the U. S. Commission on

Civil Rights said (at p. 545) : “ The fundamental interrelation

ships among the subjects of voting, education, and housing make

it impossible for the problem to be solved by the improvement of

any one factor alone.” See also pp. 389-90.

. 20N. Y. State Commission Against Discrimination, In Search of

Housing, A Study of Experiences of Negro Professional and Tech

nical Personnel in New York State (1959).

20

wise, is that it builds the attitudes of racial prejudice

which, in turn, strengthen the segregated conduct pat

terns. This was recognized almost two decades ago by

a Presidential Committee:21

For these experiences demonstrate that segre

gation is an obstacle to establishing harmonious

relationships among groups. They prove that

where the artificial barriers which divide people

and groups from one another are broken, tension

and conflict begin to be replaced by cooperative

effort and an environment in which civil rights

can thrive.22

W e show now that California, prior to enactment of

Article 1, Section 26 of the Constitution, had indeed

made significant inroads in creating “ an environment

in which civil rights can thrive” .

21Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Se

cure These Rights, pp. 82-7 (1947).

22The impact of housing discrimination is not limited to citizens

of our country. The California Advisory Committee to the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights confirms this:

“ Discrimination in housing directed against Negroes has

had an unfortunate impact on foreign students whose skin

colors are dark. The Committee heard testimony from an

Indian student at Sacramento State College who indicated

that he had been refused accommodations in a number of

instances because of his color. The testimony of student gov

ernment leaders at the same school indicated that this foreign

student problem is significant. Commendably, student groups

at Sacramento State are trying to do something about this

situation through investigation and conference.

_ “ The Committee is very disturbed by the evident impact of

discriminatory treatment on foreign students whose precon

ceptions about American democracy have been rudely upset.

These students are potential leaders in their own countries

and the image of America which they take back with them

can be significantly tarnished by such experiences.” 50 States

Report, supra p. 46.

21

III. THE DEVELOPMENT OF CALIFORNIA LAW IN THE FIELD

OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AND THE IMPACT OF

ARTICLE I, SECTION 26, OF THE CONSTITUTION.

A. The Legislative and Judicial Response to Discriminatory

Practices.

1. California Legislation Prior to 1959.

California has a long history of legislation pro

hibiting discrimination on the ground of race.23 The

first California anti-discrimination statute, enacted in

1872,24 prohibited innkeepers and common carriers

from discriminating in making their facilities avail

able to persons of all races and creeds. In 1897 legis

lation was enacted which prohibited discrimination in

“ public accommodations.”25 Those provisions, which

became Sections 51-54 of the Civil Code in 1905, and

were amended in 1919 and 1923,26 guaranteed to “ all

citizens . . . full and equal accommodations . . . of inns,

restaurants, hotels, eating houses . . . barber shops,

bath houses, theaters, skating rinks, public convey

ances and all other places of public accommodation

or amusement, subject only to the conditions and

limitations established by law, and applicable alike to

all citizens.”

23See generally, Klein, The California Equal Rights Statutes in

Practice, 10 Stanford L. Rev., 253, 255-259 (1958) ; Kaplan, Dis

crimination in California Housing: The Need for Additional Leg

islation, 50 Cal. L. Rev., 635, 636 (1962) ; Comment, The Rumford

Fair Housing Act Reviewed, 37 U.S.C. L. Rev., 427, 430, 432

(1964) ; Horowitz, California Equal Rights Statute, 33 U.S.C. L.

Rev., 260-264 (1960) ; Note, Civil Rights: Extent of California

Statute and Remedies Available for Its Enforcement, 30 Cal. L.

Rev., 563-565 (1942).

24Now Pen. Code, Sec. 365.

25Cal. State. 1893, e. 185, p. 220.

26Cal. Stats. 1919, c. 210, p. 309; Cal. Stats. 1923, c. 235, p. 485.

22

In 1925, the California legislature enacted provi

sions27 which prohibit instruction in California public

-schools reflecting adversely upon the race or color of

United States citizens. In 1935, the California Legis

lature28 prohibited questions regarding, and discrimi

nation on account of, race or color with respect to ap

plicants or candidates for employment in California

school districts. In 1937, the Legislature prohibited

discrimination on the ground of race in the state civil

service.29 Prohibition of discrimination by reason of

race or color in employment on public work projects

became law in 1939.30

The notation of color or race in California Civil

Service personnel records was forbidden by statute in

1941.31 In 1947, the California Legislature required

that assistance programs for needy and distressed

persons be administered “ without discrimination on

account of race, . . .” 32 Two years later the legisla

ture prohibited segregation and discrimination on the

basis of race or color in the State militia, and enacted

a declaration of State policy that:

27Cal. Stats. 1925, c. 276, p. 460, Sec. 2, now Education Code,

Sections 8451 and 8452.

28Oal. Stats. 1935, c. 618, pp. 1748-1749, Sec. 5.798 as amended

by Cal. Stats. 1951,, e. 1718, p. 4038, Sec. 2, now Education Code

Section 13732.

28Cal. Stats. 1937, e. 753, p. 2110, Sec, 201, now Government

Code, Section 10702.

30Cal. Stats. 1939, c. 643, p. 2068, Sec. 1, now found in Labor

Code, Section 1735.

31Cal. Stats. 1941, e. 243, p. 1308, Sec. 1„ now Government Code,

Section 19704.

. 32Cal. Stats. 1947, c, 161, p. 690, Sec. 1, now Welfare and

Institutions Code, Section 19.

“ There shall be equality of treatment and oppor

tunity for all members of the militia of this

State without regard to race or color.”38

In the same year, 1949, the California Legislature for

bade state agencies and offices from inquiring into

the race of any job applicant, agent or employee of

the State of California.* 34 In 1951, discrimination was

prohibited on the ground of race or color with respect

to apprentices in public works by any employer of

labor union.35 In 1955, the California Legislature en

acted a measure36 37 prohibiting discrimination on the

ground of race or color by certain automobile liability

insurers. In the same session of the California Legisla

ture the following provision was enacted for the pro

tection of teachers:87

“ It shall be contrary to the public policy of

this, State for any person or persons charged, by

[the governing boards of school districts], with

the responsibility of recommending [teachers] for

employment by said boards to refuse or to fail

to do so for reasons of race, color . . . of said

applicants for such employment.”

The foregoing summary shows that for nearly a

century the California Legislature has responded to

ssOal. Stats. 1949, c. 948, p. 1720, Sec. 1, now Military and

Veterans Code, Section 130.

34Cal. Stats. 1949, c. 1578, p. 2826, now in Government Code,

Section 8400.

35Cal. Stats. 1941,. c. 1192, p. 3005, Sec. 1, now in Labor Code,

Section 177.6.

sRQal. Stats. 1955, c. 125, p. 588, Sec. 1, now in Insurance Code,

Section 11628.

37Cal. Stats. 1955, c. 1910, p. 3519, now Education Code, Section

13274.

24

the pressing need for corrective action against dis

crimination on grounds of race and color. Legislative

policy has been consistent in opposing such discrimi

nation wherever it was found to exist, whether in

public accommodations, education, employment, public

welfare, the state militia or the insurance industry.

As we show next, the Legislature has also applied the

identical anti-discrimination policy to housing.

2. 1959 Legislation—The Unruh, Hawkins and Fair Employment

Practice Acts.

During 1959 the California Legislature enacted

three far-reaching statutes prohibiting discrimination

on the grounds of race or color. The first was enacted

as Sections 51 and 52 of the Civil Code and replaced

the early civil rights provisions contained in the then

Sections 51 through 54 (see p. 21, supra) :

“ §51. This section shall be known, and may

be cited, as the Unruh Civil Bights Act.

“ All citizens within the jurisdiction of this

State are free and equal, and no matter what their

race, color, religion, ancestry, or national origin

are entitled to the full and equal accommodations,

advantages, facilities, privileges, or services in all

business establishments of every kind whatsoever.

“ This section shall not be construed to confer

and right or privilege on a citizen which is con

ditioned or limited by law or which is applicable

alike to citizens of every color, race, religion, an

cestry, or national origin.”

“ § 52. Whoever denies, or who aids, or incites

such denial, or whoever makes any discrimination,

distinction or restriction on account of color, race,

25

religion, ancestry, or national origin, contrary to

the provisions of Section 51 of this code, is liable

for each and every such offense for the actual

damages, and two hundred fifty dollars ($250) in

addition thereto, suffered by any person denied

the rights provided in Section 51 of this code.”

In addition to this measure, which on its face en

compassed all residential housing sold or leased by a

“ business,” the 1959 California Legislature enacted

a specific statute directed against racial discrimina

tion in residential housing.88 This measure, popularly

known as the “ Hawkins Act,” prohibited “ The prac

tice of discrimination because of race, color, religion,

national origin or ancestry in any publicly assisted

housing accommodations . . . ” (Cal. Stats. 1959, p.

4074.)

The third major item of civil rights legislation

during the 1959 session was the California Fair Em

ployment Practices Act.39 This Act prohibited dis

crimination on the grounds of race or color by certain

employers and labor unions and established the Fair

Employment Practice Commission to administer its

provisions. The Act begins with this legislative decla

ration of public policy (Lab. Code, See. 1411) :

“ It is hereby declared as the public policy of

this State that it is necessary to protect and safe

guard the right and opportunity of all persons

to seek, obtain, and hold employment without dis- 38

38Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1681, pp. 4074-4077, now in Health and

Safety Code,, Sections 35700-35741.

89Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 121, Sec. 1, p. 1999, now in Labor Code,

Sections 1410-1432.

26

crimination or abridgement on account of race,

religious creed, color, national origin, or ancestry.

“ It is recognized that the practice of denying

employment opportunity and discriminating in the

terms of employment for such reasons, foments

domestic strife and unrest, deprives the State of

the fullest utilization of its capacities for develop

ment and advance, and substantially and ad

versely affects the interests of employees, em

ployers, and the public in general.

“ This part shall be deemed an exercise of the

police power of the State for the protection of

the public welfare, prosperity, health, and peace

of the people of the State of California.”

The next section of the Act provides (Lab. Code,

sec. 1412) :

“ The opportunity to seek, obtain and hold em

ployment without discrimination because of race,

religious creed, color, national origin, or ancestry

is hereby recognized as and declared to be a civil

right.”

In addition to these anti-discrimination measures,

the 1959' Legislature amended the Health and Safety

Code to prohibit discrimination “ in undertaking com

munity redevelopment or urban renewal projects.” 40

3. Legislation Subsequent to 1959.

There has been no slackening in the increasing

tempo of civil rights legislation in California since

40Cal. Stats. 1959, e. 1102, See. 23, p. 3182, now in Health and

Safety Code, Section 33050.

27

1959. In 1961 the Legislature prohibited county clerks

from refusing to deputize voter registrars on the

grounds of race or color.41 With respect to housing,

the 1961 Legislature declared:42

‘ ‘ The Legislature of the State of California

recognizes that among the principal causes of

slum and blighted residential areas are the follow

ing factors:

# # # # *

“ (c) Racial discrimination against persons of

certain groups in seeking housing.”

In furtherance of the same policy, the 1961 Legisla

ture prohibited all racially restrictive covenants affect

ing real property interests,43 and all racially restric

tive conditions subsequent in deeds of real property.44

That session of the Legislature also added a provision

to section 69 of the Civil Code providing that appli

cants for marriage licenses “ shall not be required to

state, for any purpose, their race or color. ’ (Cal.

Stats. 1961, p. 1665.)45

The next major assault by the California Legislature

on racial discrimination, and in particular on racial

discrimination in residential housing, is contained in

41Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 1898, Sec. 1,. p. 4008, now in Election Code,

Section 223.

«Cal. Stats. 1961, c. 2116, Sec. 1, p. 4377, now in Health and

Safety Code, Section 33039.

«C al Stats. 1961, c. 1877, Sec. 1, p. 3976, now in Civil Code,

Section 53.

44Cal. Stats. 1961,. c. 1078, Sec. 1, p. 2810, now in Civil Code,

Section 782,

4BCal. Stats. 1961, c. 554, Sec. 2, p. 1665,

28

the measure popularly known as the “ Rumford Act,”

which added sections 35700-35744 to the Health and

Safety Code48 and replaced the provisions of the

“ Hawkins Act.” The Rumford Act was broader than

the Hawkins Act in covering inter alia, residential

housing containing more than four units, even though

not publicly assisted. In addition, the Legislature

vested the exclusive authority to administer the Rum

ford Act in the Pair Employment Practice Commis

sion. The legislative policy which the Rumford Act

implemented is expressed in its initial provision

(Health & Safety Code, sec. 35700) :

“ The practice of discrimination because of race,

color, religion, national origin, or ancestry in

housing accommodations is declared to be against

public policy.

“ This part shall be deemed an exercise of the

police power of the State for the protection of the

welfare, health, and peace of the people of this

State. ’ ’

4. Development of California Antidiscrimination Common Law.

Legal developments against racial discrimination in

California have not been confined to legislative action.

This Court and other courts in the State, in the de

velopmental tradition of the common law, have recog

nized that private acts of racial discrimination may

warrant judicial relief.

An important example is James v. Marinship Corp.,

25 Cal.2d 721 (1944), involving a union which had a

closed shop contract with an employer. The union 40

40Cal. Stats. 1963, c. 1853, Sec. 2, p. 3823.

29

would not admit Negroes into membership with rights

and privileges equal to those enjoyed by white mem

bers. Instead, the Negro employees were given the

option of joining a segregated union or being dis

charged under the union security agreement. This

Court concluded that the closed shop, coupled with the

closed union, constituted an unlawful arrangement

affecting employment, and ordered the union either to

provide equal membership opportunities for Negroes

or to refrain from causing their discharge.

The decision was not predicated on statute. Rather,

the Court ruled that racial discrimination in the situ

ation there presented was contrary to the “ public

policy of the United States and [the State of Cali

fornia]” and was therefore unlawful as a matter of

common law. (25 Cal.2d at 739.) The Court explained

the interplay between common law and statutory law

prohibiting private discrimination (25 Cal.2d at 740) :

“ Defendants contend that ‘ individual invasion

of individual rights’ can be prohibited only by a

statute of the state, and they point out that Cali

fornia statutes forbidding racial discrimination

by private persons relate only to certain specifi

cally enumerated businesses such as inns, restau

rants, and the like, but not to labor unions (Civ.

Code, §§51-52). It has been said, however, that

such statutes, to the extent that they embrace

public service businesses, are merely declaratory

of the common law.”

Two years later, this Court made it clear that

Marinship was not restricted to circumstances where

a union had obtained a monopoly of labor in the lo

30

cality involved. Thus, in Williams v. Boilermakers,

27 Cal.2d 586 (1946), the Court sustained a complaint

similar to that in Marinship, which did not allege the

inability of the plaintiff to obtain work at his trade

elsewhere in the community. Following a discussion of

decisions in other states which granted a common law

remedy in like instances, the Court stated (27 Cal.2d

at 590-591) :

“ These decisions are based upon the theory that

such collective labor activity does not have a

proper purpose and constitutes an unlawful inter

ference with a worker’s right to employment. . . .

This rule is not founded upon the presence of a

labor monopoly in the entire locality, and the

reasoning is simply that it is unfair for a labor

union to interfere with a person’s right to work

because he does not belong to the union although

he is willing to join and abide by, reasonable

union rules and is able to meet all reasonable con

ditions of membership. dSTo purpose appropriate to

the functions of a labor organization may be

found in such discriminatory conduct. Here the

union’s efforts are directed, not toward advancing

the legitimate interests of a labor union, but

rather against other workers solely on the basis

of race and color. . . . The public interest is

directly involved because the unions are seeking

to control by arbitrary selection the fundamental

right to work.”

The Court added, in a more general vein, that “ where

persons are subjected to certain conduct by others

which is deemed unfair and contrary to public pol

icy, the courts have full power to afford necessary

31

protection in the absence of statute” (emphasis

added) .47

Apart from holdings which rest on the existence of

a common law public policy against racial discrimina

tion, this Court on numerous occasions has empha

sized the pervasiveness of California’s anti-discrimi

nation policy at all levels of California law. Thus, in

Orloff v. Los Angeles Turf Club;, 30 Cal.2d 734, 739

(1951), the Court stated:

“ The so-called civil rights statutes (Civ. Code

§§51-54) do not necessarily grant theretofore non

existent rights or freedoms. The enactments are

declaratory of existing equal rights and provide

the means for their preservation by placing re

strictions upon the power of proprietors to deny

the exercise of the right and by providing pen

alties for violation.”

See also, Piluso v. Spenser, 36 Cal.App. 416 (1918),

for an earlier statement to similar effect. In holding