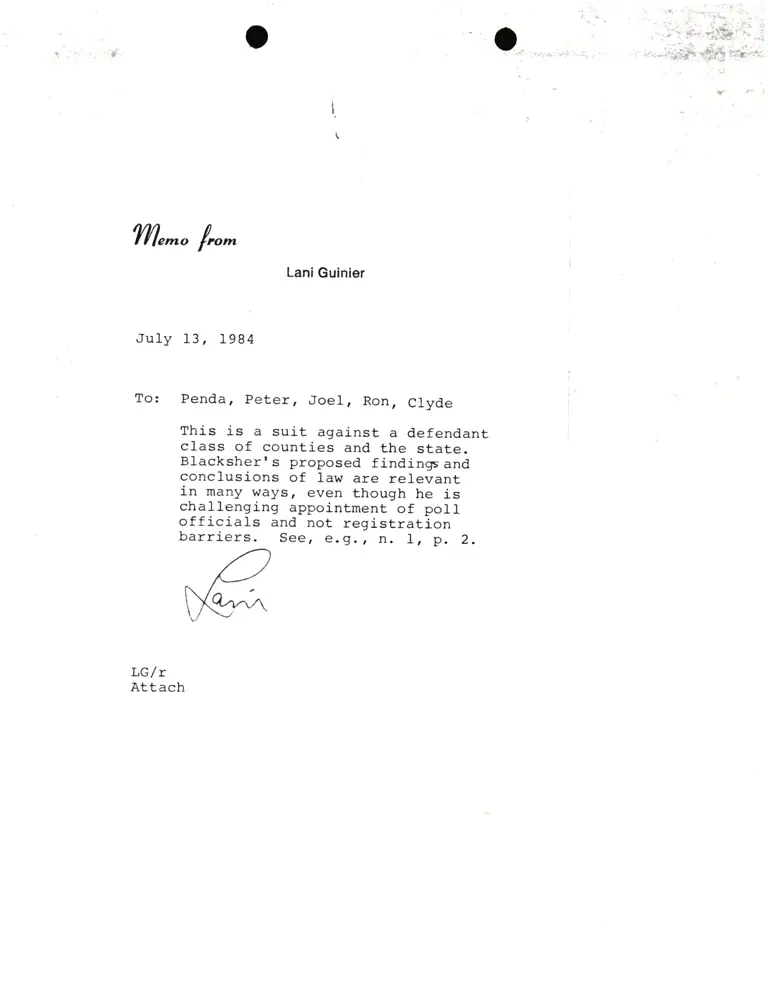

Memo from Lani Guinier to Penda, Peter, Joel, Ron, and Clyde Re: Suit and Blacksher's Findings

Correspondence

July 13, 1984

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Memo from Lani Guinier to Penda, Peter, Joel, Ron, and Clyde Re: Suit and Blacksher's Findings, 1984. 9d489545-e792-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1907225f-a31d-473c-8462-4972098e01e6/memo-from-lani-guinier-to-penda-peter-joel-ron-and-clyde-re-suit-and-blackshers-findings. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

+ {. f- o* "..ili;->7.'..;r-:

v

t.

t

//1"^o /-^

July 13, 1984

LG/ r

Attach

LanlGulnier

To: Penda, peter, Joe1, Ron, Clyde

This is a suit against a defendant

class of counties and the state.

Bl-acksher's proposed findings and

conclusions of 1aw are relevant

in many ltrays, even though he is

challenging appointment of po11

officials and not registration

barriers. See, e.g., n. I, p. 2.