Letourneau Opinion on Petition for Mandamus to Require Three-Judge Panel

Public Court Documents

August 5, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Letourneau Opinion on Petition for Mandamus to Require Three-Judge Panel, 1977. 51b24c11-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/191bddfa-df4a-4755-989b-ad1dbad316a1/letourneau-opinion-on-petition-for-mandamus-to-require-three-judge-panel. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

NAACP Legal T3efer.se Fund

10 C -l- .v b - T it 'l-

New ■. .9

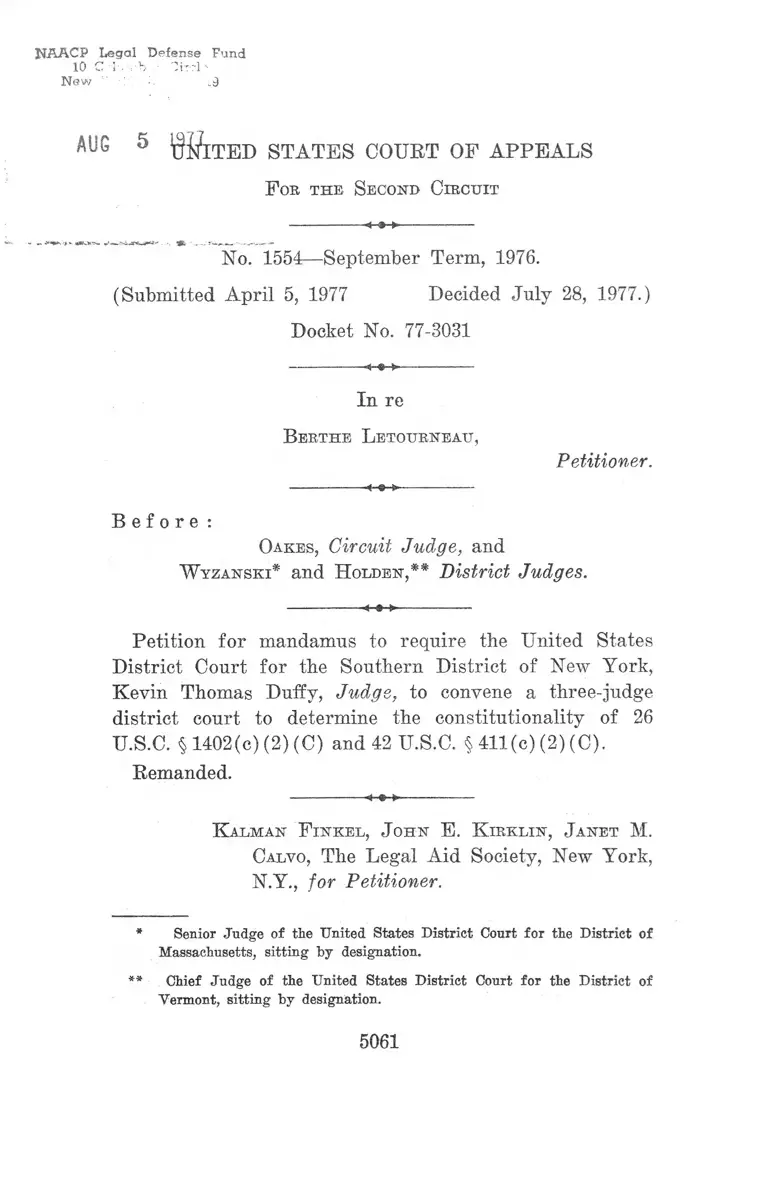

AUG 5 g y iTED gTATES COURT OF APPEALS

P oe th e S econd C ircuit

No. 1554—September Term, 1976.

(Submitted April 5, 1977 Decided July 28, 1977.)

Docket No. 77-3031

In re

B erthe L etou rn eau ,

Petitioner,

B e f o r e :

Oak es , Circuit Judge, and

W y za n s k i* and H olden , ## District Judges.

Petition for mandamus to require the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York,

Kevin Thomas Duffy, Judge, to convene a three-judge

district court to determine the constitutionality of 26

U.S.C. § 1402(c)(2)(C) and 42 U.S.C. § 411(c) (2) (C).

Remanded.

K alm an F in k e l , J o h n E. K ir k l in , J an et M.

Calvo, The Legal Aid Society, New York,

N.Y., for Petitioner.

* Senior Judge of the United States District Court for the District of

Massachusetts, sitting by designation.

** Chief Judge of the United States District Court for the District of

Vermont, sitting by designation.

5061

R o b e r t B. F isk e , J r ., United States Attorney

for the Southern District of New York

(Frederick P. Schaffer, Assistant United

States Attorney, of counsel), for Respon

dent.

Oak es , Circuit Judge:

Petitioner seeks a writ of mandamus, pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1651, to require the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York, Kevin Thomas

Duffy, Judge, to convene a three-judge district court to

determine the constitutionality of 26 U.S.C. § 1402(c) (2)

(C) and 42 U.S.C. § 411(c) (2)(C). The claim is that these

statutes unconstitutionally deny Social Security benefits

to aliens lawfully admitted for permanent residence in the

United States who work for an international organization

or foreign government instrumentality.1 Judge Duffy

refused to convene a three-judge court, which may be

convened only if the complaint “alleges a basis for equi

table relief,” Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp., v. Epstein,

370 U.S. 713, 715 (1962) (per curiam); Nieves v. Oswald,

477 F.2d 1109, 1112 (2d Cir. 1973); see 28 U.S.C. § 2282.

The judge concluded that here the relevant jurisdiction-

conferring statute, 42 U.S.C. § 405(g),2 forbids issuance of

1 A recent amendment to 28 U.S.C. § 2284 obviates the need for a

three-judge court in future cases of this kind, but the amendment by

its terms does not apply to suits commenced prior to the date o f its

enactment (August 12, 1976). Pub. L. No. 94-381, $ 7, 90 Stat. 1119

1120 (1976).

2 42 U.S.C. § 405(g) provides in relevant part:

Any individual, after any final decision of the Secretary made

after a hearing to which he was a party, . . . may obtain a review

of such decision by a civil action . . . brought in the district court

of the United States for the judicial district in which the plaintiff

resides or has his principal, place of business . . . . The court shall

have power to enter, upon the pleadings and transcript of the record,

5062

an injunction against operation of the statutory scheme.

This ruling is reviewable on a petition for mandamus.

Gonzales v. Automatic Employees Credit Union, 419 U.S.

90, 100 n.19 (1974). We hold that the district court’s

construction of 42 U.S.C. § 405(g) is incorrect, and we

therefore remand for consideration of the substantiality of

petitioner’s constitutional claims.

The court below relied for its conclusion on a footnote in

Weinberger v. Sal ft, 422 U.S. 749, 763 n.8 (1975), which

in dictum may be read to state that § 405(g) does not

affirmatively grant injunctive power to the federal courts.3

At least one other district court has been persuaded by

this footnote to hold that § 405(g) leaves it without in

junctive power. Webster v. Secretary of H.E.W., 413 F.

Supp. 127, 128 n.l (E.D.N.Y. 1976), rev’d on other grounds

a judgment affirming, modifying, or reversing the deeision of the

Secretary, with or without remanding the cause for a rehearing. . . .

The judgment of the court shall be final except that it shall be

subject to review in the same manner as a judgment in other civil

actions. . . .

3 The footnote reads in full:

Since 5 405(g) is the basis for district court jurisdiction, there

is some question as to whether it had authority to enjoin the oper

ation of the duration-of-relationship requirements. Section 405(g)

accords authority to affirm, modify, or reverse a decision of the

Secretary. It contains no suggestion that a reviewing court is

empowered to enter an injunctive decree whose operation reaches

beyond the particular applicants before the court. In view o f our

dispositions of the class-action and constitutional issues in this case,

the only significance of this problem goes to our own jurisdiction.

I f a 5 405(g) court is not empowered to enjoin the operation o f a

federal statute, then a three-judge District Court was not required

to hear this case, 28 U.S.C. 5 2282, and we are without jurisdiction

under 28 U.8.C. 5 1253. However, whether or not the three-judge

court was properly convened, that court did hold a federal statute

unconstitutional in a civil action to which a federal agency and

officers are parties. We thus have direet appellate jurisdiction under

28 U.8.C. 5 1252. McLucas v. DeChamplain, 421 U.S. 21, 31-82

(1975).

422 U.S. at 763 n.8.

5063

sub nom. Califano v. Webster, 45 U.S.L.W. 3630 (U.S. Mar.

21, 1977) (per curiam). See also Slone v. Weinberger, 400

F. Supp. 891, 894 (EJD. Ky. 1975).4 We believe, however,

that the footnote, which is an observation and not a holding,

and which does not examine the well-developed prohibition

against inferring denial of remedial powers from ambig

uous statutory language, leaves the ultimate issue open.

See Norton v. Mathews, 427 U.S. 524, 533-34 (1976)

(Stevens, </., dissenting).

Subject to due process limitations, Congress may grant

jurisdiction over particular subject matter to the federal

courts while withholding the power to give certain remedies.

See Palmore v. United States, 11 U.S. 389, 400-02 (1973).

See generally Hart, The Power of Congress to Limit the

Jurisdiction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic,

66 Harv. L. Rev. 1362, 1366 (1953); Note, Congressional

Power Over State and Federal Court Jurisdiction: The

Hill-Burton and Trans-Alaska Pipeline Examples, 49

N.Y.U.L. Rev. 131 (1974). When congressional intent is

unclear, however, no diminution in the remedial powers of

the federal courts may be inferred. Congress must speak

clearly to interfere with the historic equitable powers of the

courts it has created. Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328

U.S. 395, 398 (1946); Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321,

4 Respondent also claims that Jablon v. Secretary o f HJS.W., 399 F.

Supp. 118, 121 (D. Md. 1975) (three-judge eourt), supports its position

and indeed forecloses the issue since it was summarily affirmed by the

Supreme Court, 45 U.S.L.W. 3632 (U.S. Mar. 21, 1977). In Jablon,

however, a three-judge court was in fact convened, and whether that

court declined on the merits to issue an injunction or was persuaded

by the Salfl footnote that it had no power to do so is left unclear in the

opinion. Thus just what it was that the Supreme Court summarily

affirmed is similarly unclear. Moreover, a summary affirmance, as the

Supreme Court has recently reminded us, " 'affirmfs] the judgment but

not necessarily the reasoning by which it was reached.’ ” Mandel v.

Bradley, 45 U.S.L.W. 4701, 4701 (U.S. June 16, 1977) (per curiam),

quoting Fusari v. Steinberg, 419 U.S. 379, 391 (1975) (Burger, C.J.,

concurring).

5064

330 (1944); Brown v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497, 503

(1836); Usery v. Local 639, International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, 543 F.2d 369, 388 (D.C. Cir. 1976); Commodity

Futures Trading Commission v. British American Com

modity Options Corp., 422 F. Supp. 662, 664 (S.D.N.Y.

1976).

Here, § 405(g) speaks expansively of what a district

court may do—it may affirm, reverse or modify in any way

the Secretary’s judgment—and is completely silent on any

limitations on the court’s equitable powers. See note 2

supra. In this absence of any affirmative limitation on

historic district court powers, we may not infer that Con

gress meant to circumscribe them. Accord, Johnson v.

Mathews, 539 F.2d 1111, 1125 (8th Cir. 1976). See also

Jimenez v. Weinberger, 523 F.2d 689, 694 (7th Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 427 U.S. 912 (1976).

While we therefore hold that § 405(g) does not bar

issuance of an injunction, there remains the question

whether petitioner’s constitutional claim is so insubstantial

that a three-judge court nevertheless need not be convened,

see Goosby v. Osser, 409 U.S. 512, 518 (1973). The court

below did not consider this question, and we therefore

remand for a consideration of the substantiality of peti

tioner’s constitutional claims, particularly in light of

Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67 (1976), and Nyquist v.

Mauclet, 45 U.S.L.W. 4655 (U.S. June 13, 1977). See also

Fiallo v. Bell, 45 U.S.L.W. 4402 (U.S. Apr. 26, 1977).

Cause remanded.

5065

480- 8- 1-77 USCA—4221

MEILEN PRESS INC., 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177

219