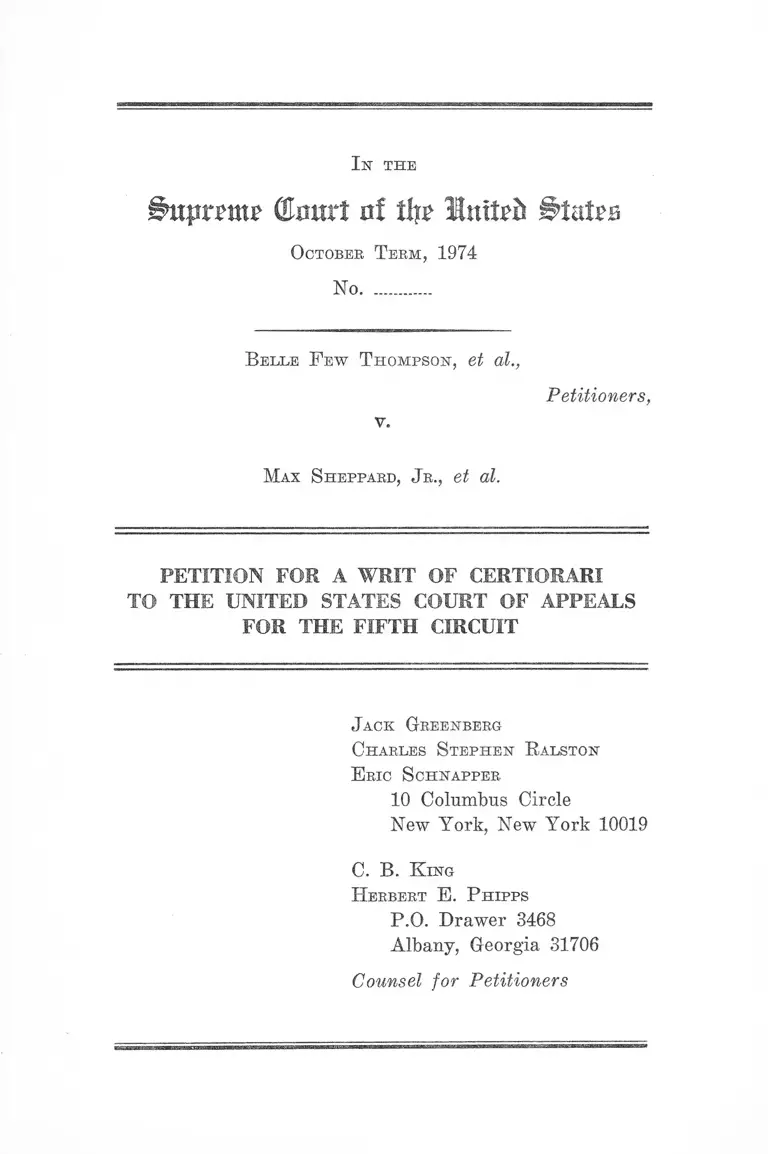

Thompson v. Sheppard Brief for Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thompson v. Sheppard Brief for Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1974. fdebbc16-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19254023-dd6b-4a0e-8c8a-026619d0fb54/thompson-v-sheppard-brief-for-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

ghijtrritt? (Burnt nf % Imiei*

O ctober T erm , 1974

No..............

B elle F ew T h o m pso n , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

M ax S heppard , J r ., et al.

PETITION FOE A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

C harles S te p h e n R alston

E ric S ch napper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C. B. K ing

H erbert E . P h ipps

P.O. Drawer 3468

Albany, Georgia 31706

Counsel for Petitioners

INDEX

PAGE

Opinions B elow ..................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......... ............... .............. ...... .......................... 2

Question Presented......... ........................... —- .................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement of the Case .............. ...... ...... -....................... 4

Statement of the Facts .... ...... ............. -............. -............. 5

Preparation of Petit Jury L is t ..... ........................... 5

Preparation of Grand Jury List ......................... 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ ......... ............. ............... 8

C onclusion* ..... 15

A ppendix

Opinion of the District Court, January 12, 1973 .... la

Opinion of the District Court, April 17, 1973 ....... 6a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ---- ------------------ 7a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals on Petition For

Rehearing ............................ 14a

11

T able oe A uthorities

Cases: page

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) ............... 12,13

Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, 403

U.S. 388 (1971) ................................................................. 14

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) .......2, 8, 9,

10,11,14

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) ............. ........... . 13

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968)............................................................... .......... 8,12

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F.Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966) 10

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ....................... 15

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947) ......... ......... 15

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972) ...... ............................ 15

Pullum v. Greene, 396 F.2d 251 (5th Cir. 1968) _____ 10

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50 (1951) ...... ................ 15

State v. Burns (Indictment No. 25570) .................... . 14

State v. Lane (Indictment No. 34052) ...... ................ 14

State v. Mallory (Indictments No. 34054 and 34082) .... 14

State v. Moulden (Indictment No. 38377) ...... .............. 14

Tollett v. Henderson, 411 U.S. 258 (1973) ....................... 15

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).............. ............ 15

Ill

Statutes: page

18 U.S.C. § 243 ................................-................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ......... ............ ...................................... 2

Code of Georgia, § 59-106 ........ ........................ —- ............ 3, 9

Other Authorities:

U.S. Census, 1970, Characteristics of the Population,

Georgia .................................-............................... -......... 6,7,9

“Jury Discrimination In the South: A Remedy?” , 8

Col. J. of Law and Social Problems 589 (1972) ....... 14

I n th e

tourt of % ItuM States

O ctobee T e em , 1974

No..............

B elle F e w T h o m pso n , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

M ax S heppaed , J e ., et al.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners, Belle Few Thompson, et al., respectfully

pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judg

ments and opinions of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit entered in this proceeding on March

8, 1974 and October 25, 1974.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 490

F.2d 830, and is reprinted in the Appendix hereto at pp.

7a-13a. The opinion of the Court of Appeals denying re

hearing is reported at 502 F.2d 1389, and is set out in the

Appendix hereto at pp. 14a-20a. The opinion of the District

Court of January 12, 1973, which is not reported, is set

out in the Appendix hereto at pp. la-5a. The order of the

District Court of April 17, 1973, which, is not reported, is

set out in the Appendix hereto, p. 6a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

March 8, 1974. The judgment of the Court of Appeals,

denying petition for rehearing and rehearing en banc, was

entered on October 25, 1974. Jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Did the District Court, having found a pattern of racial

discrimination in the selection of grand and petit jurors,

provide the “ detailed and stringent injunctive relief” re

quired by Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320

(1970), when it permitted the use of inherently discrimina

tory criteria which resulted in substantial underrepresenta

tion of blacks on those lists?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

Section 243, 18 U.S.C., provides in pertinent part

No citizen possessing all other qualifications which are

or may be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for

service as grand or petit juror in any court of the

United States, or of any State on account of race, color,

or previous condition of servitude . . .

3

At least biennially, or, if the Judge of the superior

court shall direct, at least annually, on the first Monday

in August, or within 60 days thereafter, the board of

jury commissioners shall compile and maintain and

revise a jury list of intelligent and upright citizens of

the county to serve as jurors. In composing such list

the commissioners shall select a fairly representative

cross-section of the intelligent and upright citizens of

the county from the official registered voters’ list which

was used in the last preceding general election. If at

any time it appears to the jury commissioners that the

jury list, so composed, is not a fairly representative

cross-section of the intelligent and upright citizens of

the county, they shall supplement such list by going

out into the county and personally acquainting them

selves with other citizens of the county, including in

telligent and upright citizens of any significantly iden

tifiable group in the county which may not be fairly

representative thereon.

After selecting the citizens to serve as jurors, the

jury commissioners shall select from the jury list a

sufficient number of the most experienced, intelligent

and upright citizens, not exceeding two-fifths of the

whole number, to serve as grand jurors. The entire

number first selected, including those afterwards se

lected as grand jurors, shall constitute the body of

traverse jurors for the county, except as otherwise pro

vided herein, and no new names shall be added until

those names originally selected have been completely

exhausted, except when a name which has already been

drawn for the same term as a grand juror shall also

be drawn as a traverse juror, such name shall be re

turned to the box and another drawn in its stead. (Book

18, 1972 Cumulative Pocket Part, p. 28)

Section 59-106, Code of Georgia annotated, provides

4

Statement o f the Case

This action was commenced on November 22, 1972, on

behalf of black and female citizens who alleged that they

had been unconstitutionally excluded from service on grand

and petit juries in Dougherty County, Georgia. The defen

dants are the members of the Jury Commission of Dough

erty County and other Dougherty County officials responsi

ble for the selection and composition of grand and petit

jury lists.

After a hearing the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia concluded that blacks and women

had been unconstitutionally excluded from the existing

grand and petit jury lists.1 The District Court issued a

preliminary injunction enjoining the use of these lists and

directing the defendants to prepare new grand and petit

jury lists from which blacks and women were not so ex

cluded.

Following the District Court’s order the defendants pre

pared new grand and petit jury lists. Blacks were still

substantially underrepresented on both of these new lists.

Plaintiffs objected to approval of these lists on the ground

that the defendants had failed to remedy the proven viola

tion. After a hearing the District Court issued a one sen

tence order approving the new grand and petit jury lists.

On March 8,1974, the Court of Appeals affirmed the order

of the District Court approving the new lists. On October

25, 1974, the Fifth Circuit denied petitioners’ petition for

rehearing and rehearing en banc. Two members of the

Court of Appeals, Judge Goldberg and Chief Judge Brown,

dissented from the refusal to grant rehearing en banc.

1 See Appendix, pp. la-5a.

5

Statement of the Facts

Preparation o f Petit Jury List

The old traverse or petit jury list prepared by the de

fendants in 1972 was the result of a two step procedure.

First, the Jury Commissioners, although not required to do

so by state law, expressly excluded from consideration any

otherwise eligible adult who was not registered to vote.2

Second, the Commissioners reviewed the name of the regis

tered voters and picked out those whom they regarded as

“ upright and intelligent.” Voters were regarded as upright

and intelligent if they had been selected for the petit jury

list in the past or were personally known to and vouched

for by one of the jury commissioners.3 This resulted in a

petit jury panel 12.48% of whose members were black, al

though blacks constituted 30.23% of the county imputation

over 21. Blacks were thus underrepresented by 58.71%.

The District Court correctly concluded that the petit

jury list thus prepared was unconstitutional. It held that

“ it is the right of every citizen, who is within the age and

statutory qualifications, to be considered for jury service”

and directed the Jury Commissioners “to do whatever is

necessary to consider every person for jury service.” 4

Following the District Court’s decision, the defendants

undertook to prepare a new petit jury list. Although the

subjective “upright and intelligent” test was largely aban

doned, the Jury Commissioners again refused to consider

any citizen who had not registered to vote. The record

reveals, and the Jury Commissioners were aware, that

2 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, pp. 14, 36, 66, 67.

3 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, pp. 25, 30, 34, 35.

4 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, p. 97.

6

68.0% of the white adults in Dougherty County were regis

tered, compared to only 44.3% of the blacks. By considering

only registered voters the defendants excluded from jury

service 55.7% of all the eligible blacks in the county. As a

result, when approximately 7,300 names were drawn at

random from the list of registered voters for possible jury

service, only 22.1% of those so selected were black.5 6 Ques

tionnaires were sent out to this list of voters; approximately

4,600 were returned. Among the questionnaires returned,

after elimination of certain persons exempt from, jury duty,

blacks constituted 19.15%. Although blacks constituted a

disproportionately large proportion of the voters who did

not return questionnaires, no effort was made by the Jury

Commissioners to follow up this first mailing or to locate

voters who had moved to a location within the county since

the last election.6

Preparation o f Grand Jury List

The old grand jury list was selected from among the petit

jury list with the vaguely defined purpose of picking “a

little higher type [sic].” The Commissioners refused to con

sider any citizen without prior service on a grand or petit

jury, a standard which eliminated most blacks.7 Among

those meeting this test, jurors were chosen who were per

sonally known to and recommended by one of the Jury Com

missioners.8 This selection procedure had the effect of fur

ther reducing the proportion of blacks. Thus, although

5 Transcript of hearing of April 17, 1973, p. 30.

6 Ibid., p. 13. The proportion of blacks changing residence within

the county is significantly higher than the proportion of whites.

See U.S. Census 1970, Characteristics of Population, Georgia,

Tables 119, 125.

7 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, p. 55.

8 Ibid., pp. 46-48.

7

blacks were 12.48% of tlie old petit jury list, they were only

10.7% of the old grand jury list, a reduction of 14.4%.

Blacks were underrepresented on the old grand jury list by

64.60%.

The District Court correctly concluded that the old grand

jury list was unconstitutional. The Court expressly con

demned the two primary criteria used in picking grand

jurors from the petit juror list—prior service and personal

acquaintanceship with a Jury Commissioner9— and directed

the defendants to prepare a new list.

The Jury Commissioners proceeded to prepare a new

list using a slightly rephrased subjective standard, whether

a potential grand juror “would serve the public in Albany

in a good manner.” 10 Except where a potential grand juror

was personally known to a member of the Jury Commis

sion, the decision was based on the juror’s job. A candidate

with a “high position” was regarded as desirable, a mere

carpenter was not.11 In view of the disproportionately low

number of non-whites holding professional, technical and

managerial jobs in Dougherty County,12 any such employ

ment test would have had an inherently discriminatory

effect. These selection procedures had the effect of further

reducing the proportion of blacks. Thus, although blacks

were 19.15% of the new petit jury list, they were only

16.40% of the new grand jury list, a reduction of 14.10%.

Blacks were underrepresented on the new grand jury list

by 45.75%.

9 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, pp. 96-98.

10 Transcript of hearing of April 17, 1973, p. 16. Albany is the

largest city in Dougherty County.

11 Ibid., pp. 46-47.

12 See U.S. Census, 1970, Characteristics of the Population, Geor

gia, pp. 486, 554.

8

Reasons for Granting the Writ

In Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970),

this Court established the right of black citizens, excluded

because of their race from service as grand or petit jurors,

to maintain a civil action to challenge that discrimination.

The question presented by this case is what type of remedy

the federal courts must afford once such discrimination has

been established. In the instant ease, after the District

Court found that blacks had been unconstitutionally ex

cluded from the old grand and petit jury lists, the defen

dants drew up new lists using criteria which they knew

had resulted in the past, and would result again, in the

exclusion of large numbers of blacks. In the old lists blacks

had been underrepresented by 64.60% and 58.71%, respec

tively, on the grand and petit jury lists; in the new lists

blacks were underrepresented by 45.75% and 38.66% re

spectively. The District Court and Court of Appeals ap

proved the new lists as so constituted. Petitioners maintain

that the remedy afforded in this case fell impermissibly

short of the “ detailed and stringent injunctive relief” re

quired by Carter. The failure of the courts below to provide

a remedy which in fact ends the disproportionate exclusion

of blacks is directly analogous to the problem of ineffectual

remedies dealt with in Green v. School Board of New Kent

County, 391 IT.S. 430 (1968). Review by this Court is par

ticularly appropriate because racial discrimination in the

selection of juries threatens the very integrity of the judi

cial process, and because the decision below calls into ques

tion the viability of civil litigation as a means of remedying

such discrimination.

9

In Garter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970),

this Court made clear the responsibilities of the lower

courts in framing a remedy where, as here, jury lists were

found to discriminate on the basis of race. Those courts

have “ not merely the power but the duty to render a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in

the future.” 396 U.S. at 340. Such a decree must both end

the discriminatory practices which excluded blacks and

result in a jury list on which the number of blacks is no

longer disproportionately low. The decree entered in this

case and approved by the Fifth Circuit did neither.

In preparing the new petit jury list, the Jury Commis

sioners made a deliberate decision to consider only regis

tered voters, a practice which they knew had contributed

substantially to the invalidity of the old list. The Commis

sioners were well aware that they were not required to

consider only registered voters, but were obligated by

Georgia law to use whatever other sources of names were

necessary to obtain a jury list which was “ a fairly repre

sentative cross-section” of the population and so as to

increase the number of “citizens of any significant group

in the county which may not be fairly represented.” Section

59-106, Code of Georgia.13 The Commissioners knew that

blacks were substantially underrepresented on the voter

list.14 The Commissioners also had in their possession lists

which could have been used to supplement the voter lists,

including a city directory listing the residents of the city of

Albany in which 91.7% of the county’s black population

resided.15 When asked why the Jury Commission had de

13 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, p. 67.

14 Transcript of hearing of April 17, 1973, p. 30.

15 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, p. 18; U.S. Census,

1970, Characteristics of the Population, Georgia, p. 12-69.

10

liberately used only the voter registration list, one Com

missioner responded, “I really don’t have any reason” .16

In Carter this Court stressed that the district court’s decree

had resulted in substantial efforts to go beyond the avail

able voting list, 396 U.S. at 339-340 ;17 no such efforts were

required or made here.

Similarly, the only change in the subjective method of

picking grand jurors was in altering the description of

the vague eligibility requirement from “a high type” person

to a person who would serve the public “ in a good manner” .

In practice these standards reduced the proportion of

blacks by virtually identical amounts— 14.4% in preparing

the old list and 14.1% in preparing the new list. The

potential for and degree of discrimination in this subjective

method is made apparent by comparing the effect of this

procedure on blacks with its effect on women. In preparing

the old grand jury list the jury commission, ostensibly

applying this standard, reduced female representation by

52.1% ;18 in preparing the new grand jury list the jury com

mission applied a similar test but reduced female repre

16 Transcript of hearing of January 4, 1973, p. 67.

17 This Court expressly referred to Pullum v. Greene, 396 F.2d

251 (5th Cir. 1968) and Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F.Supp, 117

(M.D. Ala. 1966) as examples of the appropriate remedial action.

In Pullum the court disapproved the creation of a new list based

on a voter list with a disproportionately low number of blacks, and

required the commissioners to augment the voter list by “ the affirm

ative action of going out and familiarizing themselves with indi

viduals and groups in the community,” 396 F.2d at 255.̂ In

Mitchell the court based its finding of discrimination on the failure

of the jury commission to use all reasonable means to identify

citizens eligible for jury duty by using “ the city directories, the

telephone directories and by visiting the precincts in the county,”

and required the commission to use such sources of names in the

future. 250 F.Supp. at 122.

18 From 24% on the petit jury to 12.48% on the grand jury.

11

sentation by only 5.8%.19 The record thus reveals, not a

change in the subjective selection methods which had earlier

resulted in the unconstitutional exclusion of both blacks and

women, but the retention of those methods by a jury com

mission willing to abandon discrimination on the basis of

sex but not on the basis of race.

In addition, the District Court’s decree clearly failed to

substantially eliminate the pattern of disproportionately

low numbers of blacks on the jury lists. In the instant case

black underrepresentation on the petit jury was reduced

from 58.71% to 36.66%, a reduction of 37.7%. Black under

representation on the grand jury declined from 64.65% to

45.75%, a reduction of only 29.2%. The jury lists approved

by the District Court and the Court of Appeals in this case

clearly failed to end the unconstitutional exclusion of

blacks, in violation of this Court’s direction in Carter, or

to produce a “ representative cross-section” of the county

population, as required by Georgia law.

The Court of Appeals, in failing to provide the remedy

required by Carter, relied on three standards each of which

was squarely in conflict with the decisions of this Court.

First, the Fifth Circuit assumed that, in deciding whether

to approve the new jury lists, the question before it was

whether those lists were—in isolation— “constitutionally

defective.” P. 12a. But once the old jury lists had been

shown to have been tainted by racial discrimination, the re

sponsibility of the courts below was “ to fashion detailed

and stringent injunctive relief that will remedy that previ

ous discrimination.” Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S.

320, 336 (1970). Regardless of whether the new jury

selection procedures were apparently neutral on their face,

19 From 37.90% to 35.66%.

12

as the Fifth Circuit contended, the proper test under Carter

was whether those procedures were adequate to remedy the

prior discrimination. That is not the test applied by the

Court of Appeals, nor a test which those procedures could

meet. A plan for selecting juries, like a plan for assigning

public school students, although not inherently unconstitu

tional, is not acceptable as a remedy for a previous viola

tion unless it in fact provides “ effective relief.” Green v.

School Board of Neiv Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968).

Second, the Fifth Circuit held that, in assessing the suf

ficiency of the new lists, the burden of proof was on the

plaintiffs to show that the lists were invalid. P. 12a. This

Court, however, has uniformly held that, where a plaintiff

establishes that state officials have engaged in discrimina

tion, the burden is on those officials to demonstrate that the

remedy they propose will in fact end that discrimination

and any continuing effects thereof. Green v. School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). Even if the

question in this case were not one of fashioning a remedy

but of assessing the validity of a list without a tainted

history, plaintiff need only show the exclusion of a dispro

portionate number of blacks by a method with potential

for discrimination. Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625,

631 (1972). The evidence in the instant case showed pre

cisely those two elements—that blacks were underrepre

sented by 45.75% and 38.66% on the new grand and petit

juries, respectively, and that this resulted from the deliber

ate and unjustified decision of the defendants to choose ju

rors from a voter list with a disproportionately low number

of blacks, and to select grand jurors using vaguely defined

subjective criteria. Even by the standard established by the

Fifth Circuit, all that plaintiffs were required to show was

that the jury list “was not fairly representative of the in

13

habitants.” P. 12a. The undisputed evidence established

that in Dougherty County, where 31.99% of the inhabitants

of voting age were black, only 22.1% of the registered

voters were black. Such a voters list, which underrepre

sented blacks by 30.92%, was manifestly not “ fairly repre

sentative.”

Third, as Judge Brown suggested in his dissent, pp. 16a-

17a, the Fifth Circuit failed to use the method established

by this Court for calculating the degree of underrepresenta

tion in a case such as this. The record showed that the total

county population over twenty-one was 30.23% black,

whereas only 19.15%' of the petit jurors and 16.40% of the

grand jnrors were black. The Fifth Circuit calculated the

degree of underrepresentation by simple subtraction, yield

ing figures of 11.08% and 13.83%. This Court has made

clear, however, that the degree of underrepresentation is

to be calculated by computing what proportion the differ

ence in composition (11.08% and 13.83%) is of the composi

tion of the population (30.23%). See Alexander v. Louisi

ana, 405 U.S. 625, 629 (1972). This method of calculation,

as Judge Brown noted, reveals that the percentage of

underrepresentation was 36.55% on the petit jury list and

45.75% on the grand jury list.

The decision of the Fifth Circuit seriously threatens the

vitality of civil litigation as a method of ending racial

discrimination in the selection of juries. The use of such

civil litigation was first proposed by Justice Jackson in

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950), on the ground that a

civil remedy, unlike the assertion of a jury discrimination

claim, by a criminal defendant, would not entail the reversal

of otherwise valid convictions. 339 U.S. at 303-304.20 See also

20 “ Qualified Negroes excluded by discrimination have available,

in addition, remedies in courts of equity. I suppose there is no

14

Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, 403 U.S.

388, 411-424 (1971) (Burger, C.J. dissenting). Such civil

litigation, to afford an attractive remedy and to protect

the legality of subsequent jury verdicts, must entail stan

dards of relief at least as stringent as those required to

validate a jury panel challenged by a criminal defendant.21

The Fifth Circuit has not so provided, nor has it purported

to hold the petit and grand jury panels to be constitutionally

constituted. The Court of Appeals merely held that the

particular plaintiffs in this particular case had failed to

meet their “ burden of showing” that the new lists were not

defective. P. 12a. Such a resolution of this case is an open,

invitation to criminal defendants to challenge every grand

and petit jury chosen from the new lists, and that is pre

cisely what has occurred in Dougherty County following

the decision of the District Court.22 Unless this Court

requires that meaningful relief be provided whenever, as

here, a civil litigant shows a pattern of racial discrimina

tion in the selection of grand and petit jurors, aggrieved

blacks will not have a significant incentive to pursue such

civil litigation in the Fifth Circuit. Such an emasculation

by the Fifth Circuit of the civil remedy recognized in Carter

would be particularly serious because it is in states com

doubt, and if there is this Court can dispel it, that a citizen or a

class of citizens unlawfully excluded from jury service could main

tain in federal court an individual or a class aetion for an injunc

tion or mandamus against the state officers responsible . . . I doubt

if any good purpose will be served in the long run by identifying

the right of the most worthy Negroes to serve on grand juries with

the efforts of the least worthy to defer or escape punishment for

crime.”

21 See “ Jury Discrimination in the South: A Remedy?” , 8 Col. J.

of Law and Social Problems 589 (1972).

22 See e.g. State v. Lane (Indictment No. 34052); State v. Burns

(Indictment No. 25579); State v. Mallory (Indictment Nos. 34054

and 34082) and State v. Moulden (Indictment No. 38377).

15

prising that circuit that the majority of criminal appeals

based on claims of jury discrimination have arisen.23

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a Writ of Certiorari should issue

to review the judgment and opinion of the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

Ch ari,es S teph en R alston

E ric S ch napper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C. B. K ing

H erbert E . P h ipps

P.O. Drawer 3468

Albany, Georgia 31706

Counsel for Petitioners

23 See e.g. Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ; Patton v.

Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947); Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282

(1950); Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50 (1951) ; Whitus v. Geor

gia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ; Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625

(1972) ; and the cases cited in Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 497,

nn. 6-8 (1972) and Tollett v. Henderson, 411 U.S. 258, 262, n. 2

(1973) .

APPENDIX

Isr th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob th e M iddle D istrict oe G eorgia

A lbany D ivision

Civil Action No. 1224

O rder o f District Court, January 12, 1973

B elle F e w T h o m pso n , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

M ax S heppard , J r ., et al.,

Defendants.

Ow ens , District Judge:

Plaintiff Negro citizens complained1 that the grand and

petit jury lists2 of Dougherty County, Georgia, are un

1 Plaintiffs in their complaint contend, among other things, that

this action should proceed as a class action pursuant to Rule 23,

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and that the Dougherty County

Board of Education is also unconstitutionally composed because

of the six members of said board of education: two, by law, are

chosen by the grand jury and the current two members were

chosen by grand juries which were selected from unconstitutionally

composed grand jury lists. These claims were not considered by

the court; they are reserved until such time as the entire case

is heard and decided.

2 Georgia law provides for a board of jury commissioners com

posed of six persons appointed by the judge of the superior court.

Georgia Code Annotated 59-101. These jury commissioners by law

are directed:

“At least biennially, or, if the judge of the superior court shall

direct, at least annually, on the first Monday in August, or

la

2a

constitutionally composed and moved this court for a pre

liminary injunction. On January 4, 1973, that motion

came on for hearing. This order confirms the court’s

oral decision announced at the conclusion of that hearing.

The undisputed evidence shows that the. present grand

and petit jury lists of Dougherty County were prepared

by the defendant jury commissioners between August 5,

1972, and December 4, 1972. In preparing those lists, the

jury commissioners— one of whom is a Negro female, one

of whom is a Negro male, and four of whom are white

males—in a series of some sixty-two meetings considered

Order of District Court, January 12, 1973

within 60 days thereafter, the board of jury commissioners

shall compile and maintain and revise a jury list of intelli

gent and upright citizens of the county to serve as jurors.

In composing such list the commissioners shall select a fairly

representative cross-section of the intelligent and upright citi

zens of the county from the official registered voters’ list

which was used in the last preceding general election. If at

any time it appears to the jury commissioners that the jury

list, so composed, is not a fairly representative cross-section

of the intelligent and upright citizens of the county, they

shall supplement such list by going out into the county and

personally acquainting themselves with other citizens of the

county, incuding intelligent and upright citizens of any sig

nificantly identifiable group in the county which may not be

fairly representative thereon.

“After selecting the citizens to serve as jurors, the jury com

missioners shall select from the jury list a sufficient number

of the most experienced, intelligent and upright citizens, not

exceeding two-fifths of the whole number, to serve as grand

jurors. The entire number first selected, including those after

wards selected as grand jurors, shall constitute the body of

traverse jurors for the county, except as otherwise provided

herein, and no new names shall be added until those names

originally selected have been completely exhausted, except

when a name which has already been drawn for the same

term as a grand juror shall also be drawn as a traverse juror,

such name shall be returned to the box and another drawn

in its stead.” Georgia Laws 1968, p. 533; Ga. Code Ann

59-106. (emphasis added).

3a

every name on the then most recent general election reg

istered voters list containing some 27,000 names. From

those names they generally selected persons (a) who were

known by one or more individnal commissioners, (b) upon

personal investigation of a jury commissioner who were

recommended by one or more jury commissioners or (c)

who were on the most recent preceding jury lists. The

grand jury list as thus compiled contains 614 names of

which there are 462 white males, 86 -white females, 49

Negro males and 17 Negro females—-about 87% white and

13% Negro; 83% male and 17% female. The petit jury

list contains 3,221 names of which there are 2,194 white

males, 625 white females, 257 Negro males and 145 Negro

females— about 87% white and 13% Negro; 76% male and

24% female.

According to the 1970 census the total population of

Dougherty County was 89,639, of which 48,444 were over

twenty-one and among those who could have registered

to vote and been considered for jury service. Of the

48,444 persons over twenty-one, there were 22,790 males

and 25,423 females; racially there were 33,568 white males

and females and 14,465 Negro males and females about

45% male and 55% female; 70% white and 30% Negro.

While as a matter of law the aforesaid numbers and

percentages establish a prima facia case of discrimina

tion against females as a group and against Negroes as

a group, Whitus v. Georgia, 385 TT.S. 545 (1967), the testi

mony of both Negro and white jury commissioners estab

lished that this discrimination was not intentional or

purposeful but instead resulted from the fact that these

jury commissioners did not understand that it is the right

of every citizen to be considered for jury duty and the

responsibility of jury commissioners to fairly consider

Order o f District Court, January 12, 1973

4a

every citizen for jury duty. Rabinowits v. United States,

366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1966). In exercising their responsi

bility jury commissioners who obviously already do not

personally know and cannot personally become acquainted

with all of the some 27,000 registered voters of Dougherty

County, are required to demonstrate that they went beyond

their personal knowledge and through some system devised

by them objectively and fairly considered every registered

voter and in so doing “fed each out of the same spoon” .

These jury commissioners though required to so demon

strate, could not. Accordingly, the present grand and petit

jury lists of Dougherty County are unconstitutionally com

posed. Turner v. Douche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970). Being un

constitutionally composed, the present grand and petit jury

lists while they may be used for jury selection to the extent

that defendant and litigants m the Superior Court of

Dougherty County voluntarily waive their constitutional

right to a jury selected from a constitutionally composed

jury list, may not and shall not otherwise be used by the

defendants from and after this date.

In view of the fact that four of the Negro plaintiffs are

in jail awaiting grand jury consideration of proposed in

dictments against them, it is imperative that these de

fendant jury commissioners proceed without delay to

compose new grand and petit jury lists for Dougherty

County. They are ordered to do so and no later than ninety

(90) days after this date to submit a written detailed report

of their actions and a copy of their new grand and petit

jury list to this court following which this court will set

this matter down for hearing and further consideration.

This constitutes the preliminary injunction of this court.

The giving of security is deemed unnecessary by the Court.

It is binding “upon the parties to this action, their officers,

Order of District Court, January 12, 1973

5a

Order of District Court, January 12, 1973

agents, servants, employees, and attorneys and upon those

persons in active concert or participation with them who

receive actual notice of the order by personal service or

otherwise.” Rule 65, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. It

shall remain in effect until further order of this court.

So Ordered, this the. 12th day of January, 1973.

W ilbu r D. O w e n s , J r.

United States District Judge

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or th e M iddle D istrict of G eorgia

A lban y D ivision

Civil Action No. 1224

Order of District Court, April 17, 1973

B elle F ew T h o m pso n , et al.,

vs.

M ax S heppard , et al.

O r d e r

It appears to the Court that, within the bounds of what

is practical and possible, both the petit and the grand

jury lists have been recomposed fairly and legally within

the standards known to this Court, and this Court will,

therefore, approve and order that as of the revision the

grand and petit jury lists of Dougherty County, Georgia

are constitutionally composed.

So ordered, this April 17, 1973.

W ilbur D. O w e n s , J r.

United States District Judge

7a

Belie Few THOMPSON, et al., etc., Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

Max SHEPPARD, Jr., et al., etc., Defendants-Appellees.

Decision of Court of Appeals

No. 73-2519.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

March 8, 1974.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Mid

dle District of Georgia.

Before COLEMAN, AINSWORTH and GEE, Circuit

Judges.

COLEMAN, Circuit Judge:

This is an action brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C., § 1983 on

behalf of black and female citizens of Dougherty County,

Georgia, to enforce their right to serve on grand and petit

juries in the courts of that county.

A preliminary injunction at the outset of the proceedings

resulted in the compilation of a new jury list, drawn by chance

from county voter lists. After a hearing, the District Court

approved this list. Plaintiffs are not satisfied and brought

this appeal. We affirm the judgment of the District Court.

According to the 1970 Census, Dougherty County then had

48,444 inhabitants over twenty-one years of age.

By percentages, this age group divides statistically into the

following characteristics:

White, male and female,

over 21 years of age 69.29%69.29%

8a

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

Blacks, male and female,

over 21 years of age

Black males

Black females

White males

30.23%

35.49%

17.49%

12.73%

White females 35.19%

There were 29,204 voters, as determined at the previous

general election.

After the District Court prohibited the further use of the

existing jury list and directed the compilation of a new one

which would pass constitutional muster, a new jury list was

compiled by a computer process which automatically selected

every fourth name on the voter list, a total of 7,308 individu

als (3,507 males and 3,801 females). Seventy five per cent of

the names so selected were of white persons and 25% were of

black persons, a variation of 5% from the actual racial popula

tion proportions of the county.

These 7,308 individuals were sent a racially neutral ques

tionnaire. Of this total, 1,240 were returned by the post

office, addressee unknown, while 1,489 addressees simply

failed to return the questionnaire at all. 1,078 females

claimed the exemption allowed them upon request by Georgia

law, 195 individuals claimed an occupational exemption, 224

claimed the over age exemption, 228 cited physical disability,

24 were unable to read or write, 102 were students away at

college, and 9 wrere dead. The record fails to reveal the race

of these various groups.

[1] This left a master jury pool of 2,721 names, selected

solely by objective methods, with no subjective considerations

entering the picture. Of these 2,721, 37.9% were women,

which would appear to settle their presence in substantial

numbers and we devote no further discussion to that aspect of

the case.

9a

Racially, the master jury pool turned out to be composed of

2199 whites (80.8%) and 522 blacks (19.2%).

This results in the following comparisons: Total black popu

lation over age twenty-one, 30.23%; percentage of blacks on

the jury list, 19.2%. Thus the jury list fell 11% short of

proportionate population representation. The record is silent

as to how much of this disparity was due to exemptions

claimed, inability to deliver the questionnaires, and failure to

return them. In any event, the names randomly selected by

the computer were within 5% of racially proportionate to the

population and there is not a hint that any name was there

after rejected for any subjective reason.

Plaintiffs rely on Broadway v. Culpepper, 5 Cir., 1971, 439

F.2d 1253 as authority for the proposition that the above

method of compiling the jury lists failed to produce the

required fairly representative cross section of the inhabitants

of the county and argue that supplemental methods should

have been used to produce a jury list in w'hich the percentage

of black jurors would more nearly approach the actual per

centage of those over twenty-one years of age residing in the

county.

We must first point out that Broadway was not a case in

which the jury list had been drawn at random by computer

from the voter list, although the Court took pains to praise

that procedure [Footnote 19, 439 F.2d at 1259], Moreover, the

Broadway Court was careful to emphasize that “ Obviously

nothing is to be gained by poking around in old 1966, 1967,

1969 ashes. What is desired—what Georgia law and the

Federal Constitution demand— is a valid jury list” . The case

was remanded for further proceedings on a fresh, rather than

a stale, record. The District Court was told, however, that in

formulating a new jury list the jury commissioners should use

“effective means to assure the return of the questionnaires

properly filled out and signed and a suitable follow up proce

dure for actual delivery of those returned as undeliverable” .

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

10a

Finally, the Court expressly declined to define what is re

quired to constitute a fairly representative cross section of the

community vis-a-vis comparison with demographic percent

ages.

We turn for guidance to the decisions of the Supreme Court

of the United States. We look first to Turner v. Fouche, 396

U.S. 346, 90 S.Ct. 532, 24 L.Ed.2d 567 (1970). This was a

Georgia case, originating in Taliaferro County, where 60% of

the inhabitants were black. The jury list was not drawn at

random. The commissioners pared the voters list of 2,152

down to 608. These names were listed in alphabetical order

and every other name (304) was carried forward to a new list,

191 white and 113 black. Further refinements resulted in a

grand jury of 17 whites and 6 blacks. 171 Negroes had been

eliminated from the list as unintelligent or not upright. The

Supreme Court held that Negroes composed only 37% of the

304 member list from which the grand jury was drawn, that

this contrasted “ sharply with the representation that their

percentage (60%) of the general Taliaferro County population

would have led them to obtain in a random selection (emphasis

ours)” .

The Supreme Court then added, “ In the absence of a

countervailing explanation by the appellees, we cannot say

that the underrepresentation reflected in these figures is so

insubstantial as to warrant no corrective action by a federal

court charged with the responsibility of enforcing constitu

tional guarantees” .

It must be remembered that the Supreme Court, 396 U.S. at

360, singled out the use of subjective judgment rather than

objective criteria as one of the causes of the impermissible

disparity.

In short, there was subjective selection of jurors, there was

no drawing at random from the whole body of voters, and 60%

of the population wound up with only 25% of the grand jurors.

THOMPSON v. SHEPPAIiD

11a

Obviously, the case now before us is not such a case as

Turner v. Fouche.

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396 U.S. 320,

90 S.Ct. 518, 24 L.Ed.2d 549, was decided the same day as

Turner v. Fouche. In Greene the jurors were not selected at

random from the whole body of eligibles. Although 65% of

the population was black, only 32% of those on the jury roll

were black. The discriminatory character of the jury lists was

conceded but the Court declined to order the appointment of

Negro commissioners, saying, “ The appellants are no more

entitled to proportional representation by race on the jury

commission than on any particular grand or petit jury” .

Mr. Justice Douglas dissented in part because he thought

the selection of black jury commissioners should be compelled,

but wrote:

“We have often said that no jury need represent propor

tionally a cross-section of the community. See Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 208..209, [85 S.Ct. 824, 829-830, 13

L.Ed.2d 759]; Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 286-287 [70

S.Ct. 629, 631-632, 94 L.Ed. 839]. Jury selection is largely

by chance; and no matter what the race of the defendant,

he bears the risk that no racial component, presumably

favorable to him, will appear on the jury that tries him.

The law only requires that the panel not be purposely

unrepresentative. See Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 550

[87 S.Ct. 643, 646, 17 L.Ed.2d 599], Those finally chosen

may have no minority representation as a result of the

operation of chance, challenges for cause, and peremptory

challenges.”

This remands us to Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 85 S.Ct.

824, 13 L.Ed.2d 759 (1965), which declared, “ Neither the jury

roll nor the venire need be a perfect mirror of the community

or accurately reflect the proportionate strength of every iden

tifiable group * * * We cannot say that purposeful dis

crimination based on race alone is satisfactorily proved by

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

12a

showing that an identifiable group in a community is under

represented by as much as 10%” .

This followed a declaration that “ a defendant in a criminal

case is not constitutionally entitled to demand a proportionate

number of his race on the jury which tries him nor on the

venire or jury roll from which petit jurors are drawn” , 380

U.S. at 208.

[2] We conclude that a jury list drawn objectively, me

chanically, and at random from the entire voting list of a

county is entitled to the presumption that it is drawn from a

source which is a fairly representative cross-section of the

inhabitants of that jurisdiction. The presumption, of course,

is rebuttable but the challenger must carry the burden of

showing that the product of such a procedure is, in fact,

constitutionally defective. In addition to the authorities al

ready discussed, see Camp v. United States, 5 Cir., 1969, 413

F.2d 419; Wright v. Smith, 5 Cir., 1973, 474 F.2d 349.

[3] More specifically, in the case now under review we

hold that the plaintiffs failed to carry the burden of showing

that the Dougherty County jury list was not drawn from a

source which was fairly representative of the inhabitants and

that they accordingly failed to establish constitutional defi

ciency on account of racial discrimination in the selection of

the jury. As was pointed out in Broadway v. Culpepper,

supra, the time is at hand for the selection of a new jury list.

As in Broadway, we remind the defendant-appellees that they

should prosecute a more effective follow-up on those whose

questionnaires are not delivered and on those who fail to

return their questionnaires. A County which has embarked

upon a wholly objective method of compiling its jury list,

substantially utilizing the same procedure used for the compi

lation of jury lists in the federal court system, will no doubt

comply with these details. If they do not, plaintiffs-appel-

lants, in the exercise of their usual diligence, have the right

effectively to question it.

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

13a

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

The jury commission, composed of whites, blacks, and wom

en, selected the grand jury list according to the method which

the Supreme Court declined to condemn in Turner v. Fouche,

supra, and we see no reason to hold it fatally defective.

The judgment of the District Court is

Affirmed.

14a

Decision of Court of Appeals Denying Rehearing

Belle Few THOMPSON et al., etc., Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

Max SHEPPARD, Jr., et al., etc., Defendants-Appellees.

No. 73-2519.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Oct. 25, 1974.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Mid

dle District of Georgia; Wilbur D. Owens, Jr., Judge.

ON PETITION FOR REHEARING AND PETITION FOR

REHEARING EN BANC

(Opinion March 8, 1974, 5 Cir., 1974, 490 F.2d 830).

Before COLEMAN, AINSWORTH and GEE, Circuit

Judges.

PER CURIAM:

The Petition for Rehearing is denied and the Court having

been polled at the request of one of the members of the Court

and a majority of the Circuit Judges who are in regular active

service not having voted in favor of it, (Rule 35 Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure; Local Fifth Circuit Rule 12) the

Petition for Rehearing En Banc is also denied.

JOHN R. BROWN, Chief Judge, with whom GOLDBERG,

Circuit Judge, joins, dissenting:

I dissent to the Court’s failure to rehear this case en banc

and on such rehearing reverse and remand the cause to the

District Court with appropriate instructions.

15a

I.

It is, first, enbancworthy, FRAP 35, 28 U.S.C.A. § 46(c), as a

case of major importance presenting recurring questions on

which this Court in the past 20 years has spoken with a clear

voice.

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

II.

But it is equally enbancworthy as such a case o f importance

because the result is, in my view, wrong and contrary to what

we have consistently held.

The basic error in the beguiling opinion of the Court,

Thompson v. Sheppard, 5 Cir., 1974, 490 F.2d 830, is that it

confuses two things: (i) proof of discrimination by race (or

sex) and (ii) the appropriate remedy once discrimination is

found to exist, either in fact, in law, or both.

Although there is loose language in the Court’s opinion

about failure of plaintiffs to carry their burden of proof there

is really no problem of burden of proof in this case. On the

initial hearing the trial court assumed that the burden was on

the state jury selection officials. And the defended officials,

without questioning that in the least, undertook to shoulder

that burden. Indeed, except for a few superficial witnesses

produced by plaintiffs on aspects which the trial court thought

were insignificant, all of the witnesses were put on the stand

by the officials. Assaying the 1972 petit and grand jury lists

the revelations of that hearing were so shocking that the

Judge from the bench held the list to be unconstitutional by

reason of discrimination against blacks, as a race, and women,

both white and black.

16a

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

This was the picture:

Table A

Percentage of Blacks in the

Over-21 Community

Percent on

Master Jury List

Percent on

Grand Jury List

30.23% 12.48% 10.7%

Percentage of W o m e n in the Percent on Percent on

Over-21 Community Master Jury List Grand Jury List

52.68% 24 % 12.48%

The District Court ordered the officials to compile a new list

which would contain more blacks and women. On the hearing

to show cause why the revised list should not be approved the

officials again produced all of the testimony. This showed

improvement—even substantial improvement—but again

there was revealed a staggering, uncontradicted, difference

between the percentage of these classes in the adult popula

tion of the county and the percentage of such classes on the

petit and grand jury lists. This glaring disparity was re

flected not only on the difference in percentage points but,

more significantly, the percentage of underrepresentation.1

1. This was obviously regarded as the significant thing in the analysis

made by the Court in this excerpt from Alexander v. Louisiana,

1972, 405 U.S. 625, 629, 92 S.Ct. 1221, 1225, 31 L.Ed.2d 536, 541:

In Lafayette Parish, 21% of the population was Negro and 21 or

over, therefore presumptively eligible for grand jury service. Use

of questionnaires by the jury commissioners created a pool of

possible grand jurors which was 14% Negro, a reduction by

one-third of possible black grarfd jurors. The commissioners then

twice culled this group to create a list of 400 prospective jurors,

7% of whom were Negro^—a further reduction by one-half.

Thus, in Alexander, the Court did not subtract 7% from 14% for a

disparity of only 7%, but calculated that the reduction was one-half,

i. e., 50%.

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

Table B

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Percentage

Point

Difference,

(5)

Percentage Original Revised Column (1) Percentage

of Over-21 Master Master Less of Under-

Community List List Column (3) Representation

Blacks 30.23% 12.48% 19.15% 11.08% 36.66%

W o m e n 52.68% 24 % 37.90% 14.78% 28.06%

Original Grand Revised Grand

Jury List Jury List

Blacks 30.23% 10.7% 16.40% 13.83% 45.75%

W o m e n 52.68% 12.48% 35.66% 17.02% 32.31%

Upon the completion of the initial hearing the trial court

clearly recognized that it had “not merely the power but the

duty to render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate

the discriminatory effects o f the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future.” Carter v. Jury Commission of

Greene County, 1970, 396 U.S. 320, 340, 90 S.Ct. 518, 529, 24

L.Ed.2d 549, 563 (emphasis added), quoting Louisiana v. Unit

ed States, 1965, 380 U.S. 145, 85 S.Ct. 817, 13 L.Ed.2d 709.

Acting under that duty the Judge ordered the preparation of

a new and better list. But in the face of continued flagrant

underrepresentation shown by Table B that same duty re

mained.

No explanations really were offered as to why that result

was the best attainable “ as far as possible” , Carter, supra.

And what evidence was offered, affirmatively proved a num

ber of sources making the system vulnerable.

Intending no disparagement of the use of data computers in

the law2 the Court nevertheless seems in my view to be

2. Ross v. Odom, 5 Cir., 1968, 401 F.2d 464; First National Bank of

Birmingham v. Daniel, 5 Cir., 1956, 239 F.2d 801; Bush v. Martin,

18a

almost mesmerized because a data computer was used. But

the role of the computer here was very limited and wholly

mechanical. It did only two things. First it merely created a

“universe” of 7,308 names from the most recent voter list3 of

29,204 voters, the racial-sex-composition of which was never

established. And second it identified the race-sex categories

in the “ universe” . From that point on the computer did

nothing.

But the universe of 7,308 dwindled to 2,721 in the course of

the further processing by the human beings comprising the

officials. This was partly because of certain exemptions,

required or claimed, in the answering questionnaire. But

larger in numbers, in percentages, and legal significance un

der this Court’s holding in Broadway v. Culpepper, 5 Cir.,

1971, 439 F.2d 1253 were the following:

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

Addressees Not Returning Questionnaires 1,489

Returned B y Post Office, Address Unknown 1,240

2,729

Thus the so-called computer created “ random” list of 7,308

was nothing of the kind. At most the universe was reduced

to 4,579. But even this was an illusion.

Although I think the Court’s declaration that “a jury list

drawn objectively, mechanically, and at random from the

entire voting list of a county is entitled to the presumption

that it is drawn from a source which is a fairly representative

cross-section of the inhabitants of that jurisdiction” , 490 F.2d

S.D.Tex., 1966, 251 F.Supp. 484; Brown, Electronic Brains and the

Legal Mind: Computing The Data Computer’s Collision With Law,

71 Yale L.J. 239 (1961).

3. Under current Georgia law, this is the “ official registered voters’

list as most recently revised by the county board of

registrars or other county election officials. . . . ” Ga.Code

Ann. § 59-106 (1973).

19a

at 833 is an acceptable working principle4 its conclusion that

the plaintiffs “ failed to carry the burden * * * ” of

“ showing that the product of such a procedure is, in fact,

constitutionally defective” , id., is not sustainable on this

record. In the first place, there was nothing to prove—noth

ing, that is, beyond that shown by the testimony from the

officials. And the result of the “ second try” was still glaring,

spectacular, underrepresentation of 36% and 45% as to blacks.

(See Table B.) This was proof that for some reason the

so-called random selection from the voter list was not ade

quate to create a fair cross-section of the community.5 What

those reasons might be, and more importantly, what steps

should be taken to achieve a fair cross-section and eliminate

the causes of the disparity were factual things which Carter

and Broadway, supra, imposed on the officials to prove.

But having responded to the duty following the initial

hearing the District Court at this point did nothing. It did

not, for example, require or even consider whether sources

other than voting lists ought to be used and if so what ones

would be the most reliable. Nor did it require that undeliv

ered or unanswered questionnaires be followed up.6 Nor did

4. Under the federal Jury Selection and Service Act of 1968, 28

U.S.C.A. §§ 1861-1869, and under all plans approved by the Fifth

Circuit reviewing panel, see, Gewin, The Jury Selection and Service

Act of 1968, 20 Mercer L.Rev. 349 (1969), voter registration lists are

the principal source. But of course the act itself requires the use of

“ some other source or sources of names in addition to voter lists

where necessary to foster the policy and protect the rights secured

by sections 1861 and 1862 of this title.” 28 U.S.C.A. § 1863(b)(2).

5. In Rabinowitz v. United States, 5 Cir., 1966 (en banc), 366 F.2d 34,

57 we declared:

The Constitution and laws of the United States place an affirm

ative duty on the [jury selection officials] to develop and use a

system that will probably result in a fair cross-section of the

community being placed on the jury rolls.

6. In Broadway, supra, 439 F.2d at 1257-1258, we condemn the use

of a voter list as a source where 40% of the questionnaires to the

voters were undelivered. In doing so we said:

A list—this constitutes the “ universe”—which is only 60% usea

ble is hardly a source reflecting the community from which a fair

cross-section may be obtained unless there is proof—lacking

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

20a

it require an explanation as to why more blacks than whites

were excluded when grand jurors were selected under the

subjective standards of “ intelligence” and “ uprightness” .

Finally, the Court’s decision is in conflict with other deci

sions with regard to the degree of underrepresentation held to

require further remedial action. Thus, in Turner v. Fouche,

1970, 396 U.S. 346, 90 S.Ct. 532, 24 L,Ed.2d 567, the Supreme

Court held that further relief was required upon a showing

that only 37% of the master list was black in a county 60%

black, an underrepresentation of 40%, and in Preston v.

Mandeville, 5 Cir., 1970, 428 F.2d 1392, the master list was 16%

black in a county 29.3% black, an underrepresentation of

45.4%.

1 therefore respectfully dissent.

here— that the composition of the 40% remnant is comparable to

the 60% available.

Here of course the remnant was 37% (2,721 of 7,308) and

contrasted with Broadway was of '/» of the voters, not all voters.

THOMPSON v. SHEPPARD

MEILEN PRESS INC.