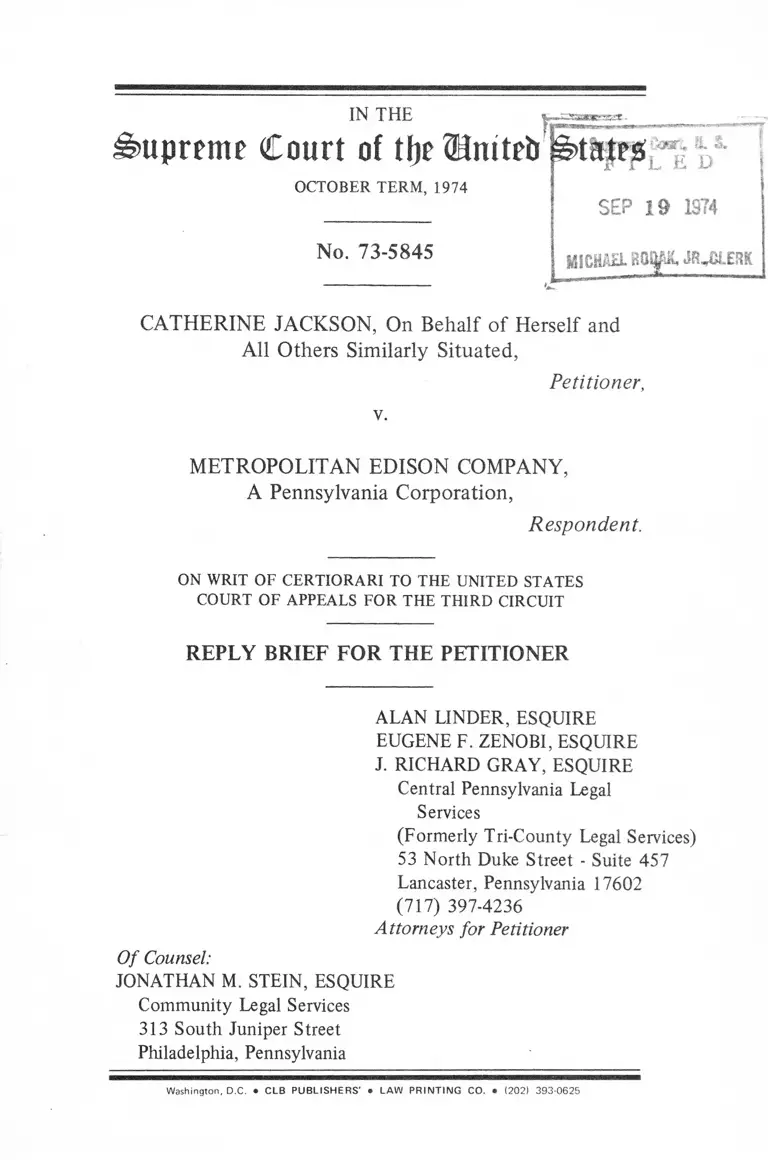

Jackson v. Metropolitan Edison Company Reply Brief for the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Metropolitan Edison Company Reply Brief for the Petitioner, 1974. 91f3f7df-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1928cf28-1d6d-4f97-b427-fb73d69cc065/jackson-v-metropolitan-edison-company-reply-brief-for-the-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

2 3 5 2 t -IN THE

m prrm r C ou rt of tlje ®nitrt> pt&fr;S

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 73-5845

kiart, fi 2

L E D

SEP 19 1374

MICHAEL RSiffiK, JR„CLERK

CATHERINE JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and

All Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioner,

v.

METROPOLITAN EDISON COMPANY,

A Pennsylvania Corporation,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

ALAN LINDER, ESQUIRE

EUGENE F. ZENOBI, ESQUIRE

J. RICHARD GRAY, ESQUIRE

Central Pennsylvania Legal

Services

(Formerly Tri-County Legal Services)

53 North Duke Street - Suite 457

Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17602

(717) 397-4236

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

JONATHAN M. STEIN, ESQUIRE

Community Legal Services

313 South Juniper Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Washington, D.C. • C LB P U B LISH ER S' • LAW PRIN TING CO. • (202) 393-0625

( i )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ARGUMENTS:

I. PETITIONER HAS STANDING TO BRING

THIS ACTION . . ' ......................................................... I

A. Petitioner is entitled to bring this action

because she is the Respondent’s cus

tomer and is the real party in interest

and the intended beneficiary and

recipient of Respondent’s services...................... 1

II. RESPONDENT’S BRIEF FAILS TO PRO

VIDE A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF

THE CUMULATIVE EFFECTS OF THE

VARIOUS INDICIA OF STATE ACTION ................. 4

A. A multi-dimensional approach is re

quired.......................... ................................................ 4

B. The Accessary indicia of state action are

present in this case so as to require a

finding that Respondent acted under

color of law when it terminated

Petitioner’s electrical services. . .............................. 6

1. The state specifically approved the

particular conduct challenged herein

because Respondent’s proposed

termination of service tariff was

passed by the Public Utility Commis

sion following public hearings.............................. 6

2. ' Respondent performs a public

function, which constitutes one in

dex of state action................................................ 7

3. Pervasive state regulation of the

specific conduct challenged is a

significant index of state action........................... 8

( ii)

4. Respondent is a monopoly whose

challenged activity herein is author

ized by and promotes interests of the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.......................... 9

5. The fact that Respondent’s activities

are subject to some Federal regula

tion is not incompatible with a

finding of action under color of state

law with regard to termination of

Page

service for nonpayment of a bill. .................... 11

6. Respondent’s actions constitute the

effectuation of state policies which

are repugnant to the Constitution............. .. 12

7. The fact that Respondent’s revenues

are subject to the Utilities Gross

Receipts Tax is one index of state

action.................... ......................... ................ 13

8. In employing the authority of the

Com m onwealth to terminate

Petitioner’s electrical services, it is

immaterial for state action purposes

that the Respondent did not enter

upon the Petitioner’s premises..................... .. 14

9. Granting Petitioner due process of

law will not deprive the Respondent

of due process of law. ....................................... 15

CONCLUSION .............................. .............................................. 19

(Hi)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adickes v. S.H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) . .................. 8

Arnett v. Kennedy, 40 L.Ed.2d 15 (1974) ............... .. 35, 16

Bailey v. Philadelphia, 184 Pa. 594, 39 A. 494

(1898) 8

Beaver Valley Water Co. v. Public Service Commis

sion, 70 Pa. Super. 621 (1918) ............................................ 3

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971) ........................................ 17

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972) ............. 16, 17

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971) ........................... 15

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715(1961) 4

Davis v. Weir, 328 F. Supp. 317, 359 F. Supp. 1023

(N.D. Ga., 1971, 1973) affirmed 497 F.2d 139

(5th Cir., 1974) ............................................................ 3, 4, 18

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1 9 7 2 ) .............................. 15, 16

Fletcher v. Rhode Island Hospital Trust National

Bank, 496 F.2d 927 (C.A. 1, 1974) ...................................... 6

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, Alabama, 94 S.Ct.

2416 (1974) 9-10

Girard Life Insurance Co. v. The City of Philadel

phia, 88 Pa. 393 (1 8 7 9 ) ......................................................... 8

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) ................................... 18

Ihrke v. Northern States Power Co., 459 F.2d 566

(C.A. 8, 1972) vacated for mootness, 409 U.S.

815 (1972) 14

Page

i

Jackson v. Northern States Power Co., 343 F. Supp.

265 (D. Minn., 1972) ......................... .................................. 3

Kadlec v. Illinois Bell Telephone Co., 407 F.2d 624

(C.A. 7, 1969) cert, den., 396 U.S. 846 (1969) ................. 9

Lathrop v. Donohue, 367 U.S. 380 (1961) ...................... 11. 12

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S 67 (1963) .............................. 9

Lynch v. Household Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538

0972) ........................... ................................................... 3, 12

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 502 (1946) ................................... 12

Mitchell v. W.T. Grant Co., 40 L.Ed.2d 406 (1974) . . . . 15, 16

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 224 (1972) ................................ 12

Moose Lodge 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 (1972) ............. 4, 7, 9

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank and Trust Co.,

339 U.S. 306 (1950) .......................................... ’ ................. 4

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1877) .................... .............. . 8

Otter Tail Power Co. v. United States, 410 U.S. 366

(1973), reh. den. 411 U.S. 910 .............................. ..............12

Palmer v. Columbia Gas of Ohio, 342 F. Supp. 241

(N.D. Ohio, W.D., 1972), affirmed 479 F.2d 153

(C.A. 6, 1972) ............................ ............................... ........... 17

Pa. Chautauqua v. Public Service Commission of Pa.,

105 P. Super. 160 (1932) .......... ......................................... 3

Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451

(1952) .............................. ............................................ 7, 12, 13

Railway Employees Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U.S. 225

(1956) ............................................................................. 11, 12

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) . .............................. 8

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ........................... 18

(iv)

Page

Page

Tyrone Gas and Water Co. v. Public Service

Commission, 77 Pa. Super. 292 (1921) .............................. 3

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 97 (1950) ......................... 12

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §1983 ......................................................................... 12

72 Pa. Stat. Anno. §8101 14

66 Pa. Stat. Anno. §1122 13

66 Pa. Stat. Anno. §1141 7

66 Pa. Stat. Anno. § 1171 .............................................. 5, 8, 16

Miscellaneous:

Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States ................. 2

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 1st Sess., App. 68 (1871)............... 12

Pa. P.U.C. Tariff Regulation No. VIII .............................. 13, 15

Pa. P.U.C. Electric Regulation Rule No. 14D ................. 13, 15

Metropolitan Edison Company Electric Tariff Elec

tric Pa. P.U.C., No. 41, Rule 15 ................................ 2, 7, 13

P.U.C. et al v. Metropolitan Edison Co., R.l.D. 64,

—P.U.R. 4 th - (March 25, 1974) ........................................... 10

Re Rules and Reguations Governing the Discon

nection o f Utility Sendees o f the Vermont Public

Service Board, 2 P.U.R. 4th 209 (April 19, 1974)............... 18

Amicus Brief o f the Public Service Commission o f

New York ........................................................... .. 17-18

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfjr ®mteb H>tateg

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 73-5845

CATHERINE JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and

All Others Similarly Situated,

v.

Petitioner,

METROPOLITAN EDISON COMPANY,

A Pennsylvania Corporation,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

ARGUMENT

I.

PETITIONER HAS STANDING TO BRING

THIS ACTION

A. Petitioner is entitled to bring this action

because she is the Respondent’s customer

and is the real party in interest and the

intended beneficiary and recipient of the

Respondent’s services.

In its first argument, Respondent raises the issue of

Petitioner’s legitimacy to bring this action. This issue

was not raised in the lower courts, nor was it included

in Respondent’s brief in opposition to the Petition for

the Writ of Certiorari.1 Certainly, the failure of the

district court and court of appeals to consider this

obvious issue lends support to the apparent lack of

significance of such issue.

There is no question that the Petitioner is a proper

party to bring this action. Petitioner was the owner,

occupant and prior billing party of the premises to

which Respondent’s electrical services were provided,

(A-22). The Respondent was certainly aware of the

above and provided service to the Petitioner as the

beneficiary of the contract entered into between it and

Dodson in September 1971. (A-23). Furthermore, after

Dodson moved from the premises, the Respondent

considered the Petitioner to be its customer and liable

for the bill, as shown by the demand made by the

Respondent’s employee for $30.00 by the following

Monday on October 11, 1971 (A-25). The fact that a

written contract was not entered into at this point is

irrelevant since Rule 1 of the Respondent’s Tariff No.

41 provides that a written contract is not necessary to

create a customer relationship (A-38).

In addition to having standing to sue as the customer

or intended beneficiary of the service, the Petitioner

acquired standing as an occupant with a legal interest in

the premises who is also the intended recipient of the

services. Thus, Respondent’s statement on page 10 of

its Brief that the Fourteenth Amendment protections

*See Rules 24(2) and 4G(l)(d)(2) of the Rules of this Court

as to timeliness of arguments.

3

apply to “persons” and not to “premises” not only

appears to reassert the discredited personal v. property

rights distinction which was struck down in Lynch v.

Household Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538 (1972), but

also ignores the reality of the fact that Petitioner’s

personal rights are being denied by Respondent when it

unconstitutionally deprives her of the property right to

continued receipt of electrical services during a billing

dispute.

To accept Respondent’s argument that only the

billing party has standing to contest a utility company’s

termination action is to maintain that a non-billing

occupant has no legal interest in receipt of utility

service. This position is not only contrary to common

sense and to public policy, but is contrary to caselaw.2

In this regard, since Respondent’s challenged tariff

requires that notice be provided prior to termination of

2 In Pennsylvania, an incoming tenant cannot be held

responsible for the bills of the former occupant of the premises.

Tyrone Gas and Water Co. v. Public Service Commission, 77 Pa.

Super. 292 (1921). See also, Beaver Valley Water Co. v. Public

Service Commission, 70 Pa. Super. 621 (1918); Pa. Chautauqua

v. Public Service Commission o f Pa., 105 Pa. Super. 160 (1932).

Similarly, courts have held that a tenant who is the non-billing

party, has standing to challenge the termination of utility service

to his or her premises without prior notice and opportunity to

be heard when the landlord billing party refuses or fails to pay

the bill. Jackson v. Northern States Power Co., 343 F. Supp. 265

(D. Minn., 1972); Davis v. Weir, 328 F. Supp. 317, 359 F. Supp.

1023 (N.D. Ga„ 1971, 1973), affirmed 497 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.,

1974) at 145, where the Court noted that the “Department’s

actions offend not only equal protection of the laws but also due

process.”

4

service for nonpayment of a bill, it is submitted that

such notice, in order to be meaningful and pass

constitutional muster, must be furnished to the

occupant of the premises. Mullane v. Central Hanover

Bank and Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306 (1950); Davis v.

Weir, 328 F. Supp. 317, 359 F. Supp. 1023 (N.D. Ga„

1971, 1973), affirmed 497 F.2d 139 (5th Cir., 1974).

As an occupant with a legal interest in said premises,

Petitioner is the customer and real party in interest,

with standing to bring this action regardless of whether

or not she was the prior billing party.

II.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF FAILS TO PRO

VIDE A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF

THE CUMULATIVE EFFECTS OF THE

VARIOUS INDICIA OF STATE ACTION.

A. A multi-dimensional approach is required.

In its brief, and contrary to the rule of Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961)

and Moose Lodge 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 (1972),

Respondent seeks to avoid a finding of state action by

treating the various indices of state action separately

and in a vacuum. Rather, Petitioner submits that it is

consideration of the cumulative effect of the several

indices of state action that is required for a

determination that ostensibly private conduct is taken

under color of law. Thus, a finding of state action is

required when specific governmental interests are

furthered by challenged conduct which is extensively

regulated, authorized and approved by the state.

In this case the several indices of state action are

integrally related to \ the conduct challenged. Hence,

Respondent’s status as a state sanctioned monopoly

enables it to threaten to terminate a customer’s services

without fear of loss of competitive advantage. The fact

that Respondent performs a public function in

furnishing electrical services furthers the state’s interest

in assuring the reasonably continuous supply of services

at a reasonable price to its citizens. See 66 Pa. Stat.

Anno. §1171. The joint participation of the Common

wealth with the Respondenuderives a State guaranteed

rate of return and is permitted to operate without

significant competition, while the Commonwealth

benefits from the efficient operation of the

Respondent’s activities and receives direct tax revenues

therefrom. In addition, the Commonwealth derives an

economic benefit when it delegates quasi judicial

authority to the Respondent to adjudicate billing

disputes and to deprive customers of property. Finally,

the Commonwealth regulates and specifically authorizes,

encourages, and approves the particular conduct

challenged.

The thrust of Respondent’s brief is not only to

attempt to discredit the Petitioner’s argument by

isolating the various indices of state action, but also to

utilize the “floodgates” argument for its in terrorem

effect. Respondent implies that a finding of state action

herein will result in a complete breakdown of the

distinction between essentially private conduct and

public action. However, in so doing, Respondent applies

6

Petitioner’s argument out of context in this regard.

State action need not be found solely because of state

licensing or regulation, but instead, results where, in

addition to the above, the conduct challenged promotes

state interests and is authorized by the state which acts

as a partner in such conduct.3

B. The necessary indicia of state action are

present in this case so as to require a finding

that Respondent acted under color of law

when it terminated Petitioner’s electrical

services.

In its brief, Respondent mistakenly attempts to

isolate, distinguish or minimize the importance of the

various indicia of state action set forth in Petitioner’s

brief.

1. The state specifically approved the particular conduct

challenged herein because Respondent’s proposed

termination of service tariff was passed by the Public

Utility Commission following public hearings.

On pages 24-25 of its brief, Respondent notes that in

1971 it filed proposed tariffs for a rate increase with

3 Although failing to find state action where a bank set off an

indebtedness against the checking account of a depositor, the

First Circuit Court of Appeals noted that there was “little

parallel between a closely regulated bank and a public utility

which has been chosen by the state to carry out a specific

governmental objective. Fletcher v. Rhode Island Hospital Trust

National Bank, 496 U 2d 927, 932 (C.A. 1, 1974).

7

the Public Utility Commission. In its proposed tariff the

Respondent included certain of its prior tariffs,

including Rule No. 15, the termination of service tariff.

Hearings were then held before the Commission from

September 30, 1971 to March 10, 1972. The

Commission granted a rate increase and did not order a

change in Respondent’s other regulations.

, It is apparent from the above that the Commission

considered and gave specific approval to Respondent’s

termination of service- tariff, l i \ Public Utilities

Commission v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 45 i (1952) state action

resulted where the District of Columbia Public Utility

Commission held hearings and specifically approved the

challenged action. Respondent’s challenged activity thus

falls within the doctrine of Poliak, supra, and requires a

finding of state action thereunder. See Moose Lodge

107 v. Irvis, supra.

2. Respondent performs a public function, which consti

tutes one index of state action.

Respondent contends that it does not perform a

public function because the Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania allegedly had no common law duty to furnish

utility services to its citizens (Resp. Br., 11). Whether

or not the Commonwealth originally had such a duty is

immaterial, since, in passing the Public Utility Law, the

Commonwealth in fact assumed an obligation to assure

that its citizens receive reasonably continuous utility

services at reasonable rates. 66 Pa. Stat. Anno. §1141,

8

§1171.4 See also Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1877).

Furthermore, conduct undertaken pursuant to common

law “custom or usage” is certainly state action. See

Adickes v. S.H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970);

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967).

In addition to the above noted public function, the

Respondent also performs a public function through the

exercise of quasi-judicial authority delegated to it by

the Commonwealth. Respondent can thus determine the

lawfulness of its own regulations, adjudicate disputes

between itself and its customers, and effect a seizure of

property interests by terminating a customer’s electrical

services.

3. Pervasive state regulation of the conduct challenged is

a significant index of state action.

Respondent charges that the distinction between

public and private action will be destroyed if a finding

of state action may rest upon the sole fact of a state

regulatory scheme in a particular case. (Resp. Br., 14).

However, Respondent misstates Petitioner’s argument in

tliis regard. Petitioner asserts only that a finding of

state action is required where it is found that the state

benefits from challenged conduct-*vhtre i f -i5 found that

which it 4

4 The cases cited by Respondent in support of its position,

predate the enactment of the Public Utility Law. Girard Life

Insurance Co. v. The City o f Philadelphia, 88 Pa. 393 (1879);

Baily v. Philadelphia, 384 Pa. 594, 39 A. 494 (1898).

9

regulates, encourages and authorizes.5 See Moose Lodge

v. Irvis, supra. Thus, as noted by the district court

herein, the state must be involved not simply with some

activity of the institution alleged to have inflicted

injury upon a plaintiff, but with “the activity that

caused the injury” (A-71). See also Kadlec v. Illinois

Bell Telephone Co., 407 F.2d 624 (C.A. 7, 1969) cert,

den., 396 U.S. 846 (1969). Certainly, as noted above,

the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is so significantly

involved in the Respondent’s termination activity as to

warrant a finding of state action.

4. Respondent is a monopoly whose challenged activity

herein is authorized by and promotes the interests of

the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Respondent disputes Petitioner’s characterization of

it as a “state sanctioned monopoly” (Resp. Br., 15).

Certainly, such a characterization cannot now be

seriously disputed in view of Gilmore v. City o f

5Hence, the mere fact that a state may regulate restaurants in

general would not warrant a finding of state action in a situation

involving excessive prices if the challenged prices are not

specifically authorized by the state, but might very well warrant

a finding of state action in a situation where the state authorizes

restaurants to engage in challenged racial discrimination. See

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 67 (1963).

in

Montgomery, Alabama, 94 S.Ct. 2416 (1974).6 Further

more, it is apparent that the above characterization of

Respondent is fully supported by the finding of the

Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, as recently as

March 25, 1974 when it granted the Respondent a rate

increase of over $18 million.7

6In Gilmore, supra, this Court noted that:

“Traditional state monopolies, such as electricity, water,

and police and fire protection—all generalized governmental

services—do not by their mere provision constitute a

showing of state involvement’ in- invidious”discriminations.”

Supra, 2426. ......

It should be noted that Petitioner’s legal position is fully

consistent with the above statement, since state action is present

herein not because Respondent is a state granted monopoly, but

because the Respondent’s monopoly status enables it to

effectuate state interests and facilitates termination of a

customer’s services.

7In its Order of March 25, 1974, at R.I.D. 64, P.U.C. et al v.

Metropolitan Edison Co.,—P.U.R. 4 th -, the Commission noted

that:

“Respondent was incorporated under the laws of Pennsyl

vania on July 24, 1922, and is a subsidiary of General

Public Utilities Corporation (G.P.U.), a holding company

registered under the Public Utility Holding Company Act

of 1935. G.P.U. now owns all the common stock of three

operating electric subsidiaries; namely respondent, Pennsyl

vania Electric Company, and Jersey Central Power and

Light Company, which form a fully integrated power pool.

G.P.U. is a member of the Pennsylvania - New Jersey -

Maryland (P.J.M.) inter-connection, which consists of

twelve operating utility companies combined into six

member systems. Respondent participates in P.J.M. as a

subsidiary of G.P.U. . . .”

continuedI

Respondent’s monopoly status is significant because

it is by virtue of such state granted status that it is

enabled to successfully threaten to terminate

Petitioner’s service with impunity. In addition, the fact

that Respondent’s monopoly status promotes certain

state interests is significant in the consideration of the

existence of state action. See Railway Employees’

Department v. Hanson, 351 U.S. 225 (1956); Lathrop

v. Donahue, 367 U.S. 830 (1961).

5. The fact that Respondent’s activities are subject to

some Federal regulation is not incompatible with a

finding of action under color of state law with regard

to termination of service for nonpayment of a bill.

Respondent seeks to exempt itself from a state

action analysis merely because it is subject to some

Federal regulation (Resp. Br., 16). However, the fact

that Respondent is subject to some Federal regulation

does not negate the fact that it is also extensively

regulated by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Whether Respondent may be considered as acting on

behalf of the state in a particular situation depends

upon how extensively the state is involved in that

“At August 31, 1972, respondent furnished electric service

to 312,188 customers located in all or portions of four

cities, 92 boroughs, and 155 townships located within 14

counties in eastern and central Pennsylvania. The service

area comprises approximately 3,300 square miles or seven

per cent of the entire state, with an estimated population

of 826,400 at December 31, 1972.” Supra, pp. 4-5.

12

particular conduct,8 As noted above, the Common

wealth of Pennsylvania is significantly involved in the

Respondent’s challenged termination activity.

6, Respondent’s actions constitute the effectuation of

state policies which are repugnant to the Constitution.

On page 18 of its brief, Respondent suggests that a

finding of state action should be confined only to cases

involving racial discrimination. Such a suggestion

certainly lacks merit especially in light of the history of

the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1983, the purpose of

which was to provide protection not only for former

slaves, but for all people who were deprived of federal

rights under color of state law. Cong. Globe, 42nd

Cong., 1st Sess., App. 68 (1871). See also Mitchum v.

Foster, 407 U.S. 224 (1972); Lynch v. Household

Finance Corp., supra. Thus, this Court has decided

numerous state action cases not involving racial

discrimination. See Public Utilities Commission v.

Poliak, supra; United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 97

(1950); Railway Employees Dept. v. Hanson, supra;

Lathrop v. Donohue, supra; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S.

502 (1946).

* Otter Tail Power Co. v. United States, 410 U.S. 366 (1973),

noted by Respondent on page 17 of its brief, is fully consistant

with this position, since in that case, Otter Tail was not exempt

from anti-trust action where its particular complained of conduct

was not subject to specific state governmental regulation or

authorization.

13

Respondent correctly notes that there must be a

nexus between the state and its relationship with the

challenged activity for state action purposes. (Resp. Br.,

19) . However, Respondent incorrectly states that

Pennsylvania law does not command or approve

Respondent’s summary termination action. (Resp. Br.,

20) . By authorizing Respondent’s termination of service

tariff, No. 41, Rule 15, through prior enactment of

Sections 202(d) and 401 of the Public Utility Code, 66

Pa. Stat. Anno. §§1122, 1171, and, as further

authorized by Public Utility Commission Tariff Regula

tion No. VIII and Electric Regulation Rule 14D, the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has expressly

sanctioned the Respondent’s challenged activities.

Furthermore, the fact that the Public Utility Commis

sion actually held formal hearings in 1971 and 1972

regarding Respondent’s proposed rate increase and

various other proposed tariffs, including Rule 15, the

very rule challenged herein, brings this case within the

doctrine of Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, supra,

so as to justify a finding of state action based on the

express and formal approval by the state of the

challenged termination activity.

7. The fact that Respondent’s revenues are subject to the

Utilities Gross Receipts Tax is one index of state

action.

Payment of taxes in itself need not justify a finding

of state action. (Resp. Br., 26). However, the Utilities

14

Gross Receipts Tax, 72 P.S. §8101 et seq., is not an

ordinary tax paid by all corporations, but instead, is a

unique tax paid only by public utilities, based upon

gross revenues. Thus, the state directly benefits from

payment of said tax as reflected in increased company

revenues resulting from threatened utility terminations.

Respondent is correct in its position that the Utilities

Gross Receipts Tax is no different from the 5% profit

sharing arrangement recognized as prominent for state

action purposes in Ihrke v. Northern States Power Co.,

459 F.2d 566 (8th Cir., 1972), vacated for mootness,

409 U.S. 815 (1972). (Resp. Br., 26). However, it

should be noted in tills regard that the finding of state

action in Ihrke, supra, was based not only on such

profit sharing arrangement between the utility and the

City of St. Paul, but upon a variety of state action

indicia, including extensive regulatory review of the

utility’s tariffs and pervasive governmental regulation of

the utility’s activities. Such factors, as noted above, are

abundantly present in the instant case.

8. In employing the authority of the Commonwealth to

terminate Petitioner’s electrical services, it is im

material for state action purposes that the Respondent

did not enter upon Petitioner’s premises.

As noted above, contrary to Respondent’s assertion

(Resp. Br., 26), Respondent did terminate Petitioner’s

electrical service pursuant to state authorization. The

fact that this termination was accomplished without

15

entry on Petitioner’s premises is irrelevant, since the

issue is whether the Respondent may terminate services

without due process of law in the first instance. The

means by which such service is terminated is not

significant.9

9. Granting Petitioner due process of law will not deprive

the Respondent of due process of law.

Respondent asserts that Petitioner seeks to use the

federal courts to compel Respondent to furnish free

service to its customers (Resp. Br., 28). This statement

certainly misconstrues the nature of this action. At no

time has Petitioner asserted that she should be provided

with free service. Indeed, although Respondent has

refused to bill Petitioner for services following the

commencement of this action (Resp. Br., 9), Petitioner

has placed funds aside for her estimated electric bills

pending termination of this action. Accordingly,

Petitioner seeks to assure only that utility services not

be terminated without due process of law for failure to

pay a disputed bill.10 Petitioner does not seek to avoid

9 Respondent’s tariffs authorizing entry on private property to

terminate service were authorized by Commission Rule 14D and

Commission Regulation No. VIII, and were subject to the

approval of the Commission.

10The requirement of a prior hearing, as mandated by Fuentes

v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1972), in the absence of “extraordinary

circumstances” , Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971), is

not modified by Arnett v. Kennedy, 40 L.Ed.2d 15 (1974), or

by Mitchell v. W.T. Grant Co., 40 L.Ed.2d 406 (1974).

(continued)

16

payment. of the current bill pending resolution of a

disputed bill.

Arnett v. Kennedy, supra, involved the termination of a public

employment situation where rights could be adequately vindi

cated by a post hearing review and where adequate administrative

remedies were available. It should be noted in that case that six

members of this Court adhered to the concept that “the

adequacy of statutory procedures for deprivation of a statutorily

created property interest must be analyzed in constitutional

terms” . Arnett v. Kennedy, supra (Opinion of Mr. Justice Powell,

concurring in part and concurring in the result in part).

Furthermore, such property interests are not “created by the

Constitution” ; rather, they are created and their dimensions are

defined by existing rules that “stem from state laws.” Board o f

Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972) at 577. Such property

interests are created and defined by the Pa. Public Utility Law,

66 Pa. Stat. Anno. §1171, in the instant case. In balancing the

individual’s property interests in due process of law against the

competing interests of the state, factors such as the individual’s

“brutal need” and “being driven to the wall” must be afforded

important consideration. Arnett v. Kennedy, (opinion of Mr.

Justice White, concurring in part and dissenting in part) 40

L.Ed.2d at 54-55. Certainly, such factors are present in the

instant case.

The case of Mitchell v. IW. T. Grant, supra, involved a creditor

replevin situation specifically distinguishable from Fuentes supra,

in that, due to fear of disposal or waste by the debtor of the

creditor’s property, the creditor would be permitted to

temporarily seize such property pursuant to a closely supervised

procedure under control of the court from beginning to end, in

which a sworn affidavit and petition is presented to and

approved by a judge, following posting of a bond. This procedure

also allows for return of the property to the debtor and an

immediate hearing upon posting of a counterbond by the debtor,

upon whom the “ impact” of a temporary deprivation is not

(continued)

17

Respondent asserts that the tremendous hardship that

would allegedly be imposed upon it by requiring it to

afford customers the opportunity to resolve disputed

bills before their services are terminated justifies a

continued denial of the constitutional rights of such

customers. Certainly, any added costs of administration

must be subordinate to consideration of whether due

process is to be provided in the first instance. See Bell

v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971). Only after a

determination is made that due process is required may

consideration be given to what type of process is in fact

due, following a “balancing” of the circumstances.

Board o f Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972).

In this case, although due process requires that

customers be afforded a prior opportunity to resolve

disputes, the actual nature of the dispute resolution

procedure may vary depending upon the circumstances

of the case, and may be informal in the first instance.

Contrary to Respondent’s expressed fears, Petitioner

does not seek to impose an “inflexible” hearing

requirement in every case. (Resp. Br., 28). Hence, the

requirement of providing a conference with a company

official or an informal hearing at the company level

would seem to be an inexpensive method of resolving

disputes. See Amicus Brief of the Public Service

great. Such situation has little applicability to the instant case,

where the temporary deprivation of utility services following a

summary and unsupervised termination may affect life itself.

Palmer v. Columbia Gas o f Ohio, 342 F. Supp. 241 (N.D. Ohio,

W.D., 1972), affirmed 479 F.2d 153 (C.A. 6, 1973).

18

Commission of New York.11 Certainly, the requirement

of a formal hearing conducted by the Public Utility

Commission following the failure of the utility

company to satisfactorily resolve the dispute, would not

involve such extensive costs as to make such procedure

economically infeasible or constitutionally prohibitive.12

Finally, the cost involved in disposing of administrative

appeals cannot outweigh due process requirements.

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970); Shapiro v.

Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969). Thus, when presented

with the very argument that the utility would suffer an

undue financial burden if required to comport with due

process of law, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals

stated:

“Finally, in view of the concededly small number

of similar applicants, the miniscule percentage of

the Department’s revenue that is affected, the

minimal cost of instituting constitutionally suffi

cient procedures, and the availability of other

collection methods, we hold the City has failed to

demonstrate any substantial detriment to its

revenue bond rating.” Davis v. Weir, supra, 497

F.2d at 145.

11 See also “Re Rules and Regulations Governing the

Disconnection of Utility Services” , of the Vermont Public Service

Board, 2 P.U.R. 4th 209 (April 19, 1974) at 218.

12 It should be expressly noted that at the time of this action,

as well as at present, neither the Respondent’s tariffs nor the

Public Utility Commission’s regulations provided for any formal

method of dispute resolution prior to the termination of a

customer’s utility services.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Petitioner respectfully

urges that this Court reverse the Judgment and Opinion

of the Court below.

Of Counsel:

Respectfully submitted,

ALAN LINDER, ESQUIRE

EUGENE F. ZENOBI, ESQUIRE

J. RICHARD GRAY, ESQUIRE

Central Pennsylvania Legal

Services

(Formerly Tri-County Legal Services)

53 North Duke Street - Suite 457

Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17602

Attorneys for Petitioner

JONATHAN M. STEIN, ESQUIRE

September 1, 1974