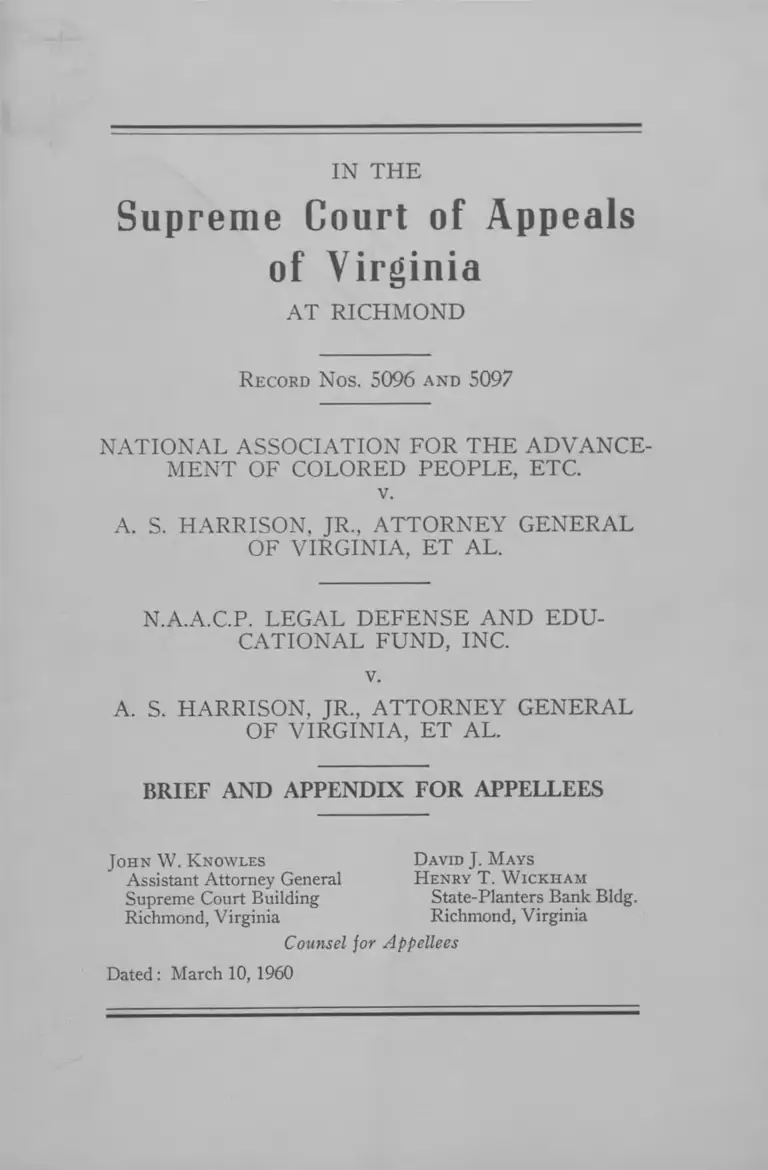

NAACP v. Harrison Brief and Appendix for Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Harrison Brief and Appendix for Appellees, 1960. fd75513a-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1929c8ab-db0c-4ed3-8443-5ffa6a992dcb/naacp-v-harrison-brief-and-appendix-for-appellees. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia

A T R IC H M O N D

R ecord N os. 5096 and 5097

N A T IO N A L A SSO C IA T IO N FO R T H E A D V A N C E

M E N T O F C O LO R ED P E O P L E , ET C .

v.

A. S. H A R R ISO N , JR ., A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

O F V IR G IN IA , E T A L.

N .A.A .C.P. L E G A L D E F E N S E A N D E D U

C A T IO N A L F U N D , INC.

v.

A. S. H A R R ISO N , JR ., A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

O F V IR G IN IA , E T A L .

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLEES

J ohn W. K now les

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel

D avid J. M ays

H en ry T. W ic k h a m

State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Appellees

Dated: March 10, 1960

TABLE OF CONTENTS

P r elim in a r y S ta t em en t ..................................................................... 1

S t a t em en t of t h e C a s e ..................................................... 2

T h e S tatutes I n v o lv ed ................ ........................................ - .......... 3

T h e Q u estio n s P r e s e n t e d ........................................................... 4

S t a t em en t of t h e F a c t s ............................................................. 4

A r g u m e n t ................................................................................................... 28

I. Certain Activities of the Plaintiffs Are Prohibited by

Chapter 33 ............................................................................ 28

II. Chapter 36 Is Applicable to Some of the Activities of

the Plaintiffs ........................................................................ 35

III. Freedom of Speech and Chapters 33 and 3 6 ................... 39

IV. Equal Protection and Chapter 3 6 .................................... 48

C onclusio n ............................................. -...................................... 51

Page

A ppen dix :

I. Chapter 33, Acts of the General Assembly.......... App. 1

II. Chapter 36, Acts of the General Assembly........... App. 5

III. Defendants’ Exhibit D-3, Statement of Legal Fees

and Expenses Paid by Virginia State Conference.. App. 12

IV. Summary of Testimony of Plaintiffs in School

Segregation C ases.................................................... App. 14

Cases

Page

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. Jackson, 235 F.

2d 390............................................. - ........................................... 47

Bigelow v. Old Dominion Copper, 74 N. J. Eq. 457 ................... 42

Board of Supervisors v. Boaz, 176 Va. 126.................................. 37

Brannon v. Stark, 185 F. 2d 871.................................................... 42

Commonwealth v. Mason, 175 Pa. Supp. 576 .............................. 37

Dorghty v. Grills, 37 Tenn. App. 6 3 .............................................. 47

Gates & Sons Co. v. Richmond, 103 Va. 702 ................................ 37

Hilebrand v. State Bar of California, 225 P. 2d 508 .................. 47

Hughes v. Superior Court of California, 339 U. S. 460 ............. 49

In Re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 131 111. 2d 391 ....... 47

International Brotherhood v. NLRB, 431 U. S. 694 .................... 37

LaPage v. United States, 146 F. 2d 536 ...................................... 37

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107.............................................. 43

M’lntyre v. Thompson, 10 F. 531.................................................. 36

N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee, 199 Va. 665 ........................................ 50

National Ass’n. for Advancement of Colored People v. Patty,

159 F. Supp. 503 ......................................................................... 5

Nichols v. Bunting, 3 Hawks (N. C.) 8 6 ...................................... 36

People v. Drake (Cal., 1957), 310 P. 2d 977 ............................... 37

People ex rel Chicago Bar Assn. v. Chicago Motor Club, 362 111.

50 ................................................................................................. 45

People ex rel Courtney v. Assn, of Real Estate Taxpayers, 4 111.

102 ............................................................................................... 46

Railroad Express Agency v. New York, 336 U. S. 106............. 50

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Page

Re Maclub of America, Inc. (M ass.), 3 N. E. 2d 272 ................ 44

Richmond Ass’n. of Credit Men v. Bar Association, 167 Va.

327 ................................................................................. 28, 29, 30

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 .................................. 39

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 .................................................. 40

Thursten v. Percival, 18 Mass. (1 Pick.) 4 1 5 ............................ 36

Tiller v. Commonwealth, 193 Va. 4 1 8 .......................................... 37

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S. 144............. 49

United States v. Petrillo, 332 U. S. 1 ............................................ 50

Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchison, 28 F. Supp. 526 .......................... 42

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178...................................... 39

Wickham v. Conklin, 8 Johns (N. Y.) 220 .................................. 36

Williamson v. Lee Optical Company of Oklahoma, 348 U. S.

483 ............................................................................................... 48

Statutes

Acts of the General Assembly, Extra Session, 1956:

Chapter 33 .................................................... 2, 3, 4, 15, 28, 33

34, 39, 41, 51

Chapter 36 ...................................... 2, 3, 4, 15, 35, 36, 37, 39

41, 44, 48, 50, 51

Code of Virginia:

Section 54-74 ........ ................................................................ 3, 33

Section 54-78 ................................................................. 3, 33, 34

Section 54-79 .................................................................. 3, 4, 34

Section 1-10 ............................................................................... 35

Section 54-42 ............................................................................. 28

Section 54-44 ............................................................................. 28

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment .................................................... 41, 48

Other Authorities

53 A. L. R ........................................................................................... 43

121 A. L. R ......................................................................................... 44

Blackstone’s Commentaries, Book 4 .............................................. 36

Canons of Professional Ethics:

Canon 35 ..................................................................................... 32

Canon 47 ..................................................................................... 31

Restatement of Torts, Section 766 ................................................ 38

Virginia State B a r :

Committee on Legal Ethics

Opinion No. 10 ............................................................ 32, 40

Opinion No. 41 .................................................................... 33

Opinion No. 4 3 ..................................................................... 33

Opinion No. 45 .................................................................. 33

Committee on Unauthorized Practice of Law

Opinion No. 3 0 ..................................................................... 42

Ninth Annual Report, p. 3 7 ...................................................... 31

Ninth Annual Report, p. 3 9 ...................................................... 31

Seventeenth Annual Report, p. 3 2 .......................................... 31

Page

Webster’s New International Dictionary (2d ed., unabridged) .. 37

IN T H E

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

A T R IC H M O N D

R ecord N os. 5096 and 5097

N A T IO N A L A SSO C IA T IO N FO R T H E A D V A N C E

M E N T O F C O LO R ED P E O P L E , ETC .

v.

A. S. H A R R ISO N , JR ., A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

O F V IR G IN IA , E T A L.

N .A .A .C.P. L E G A L D E F E N S E A N D E D U

C A T IO N A L F U N D , INC.

v.

A. S. H A R R ISO N , JR ., A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

O F V IR G IN IA , E T A L.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

These cases were heard together by the court below

though the appellants, hereinafter referred to as plain

tiffs, have filed separate briefs before this Court. The

appellees, hereinafter referred to as defendants, respect

fully request that this brief be considered in opposition to

both briefs of the plaintiffs.

2

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, hereinafter referred to as N .A.A.C.P.,

and the N.A. A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., hereinafter referred to as Legal Defense Fund or

Fund, are New York corporations registered with the

State Corporation Commission to do business in this

State. In the court below, they sought a declaratory

judgment concerning Chapters 33 and 36, Acts of Assem

bly, E xtra Session, 1956 (§§54-74, 54-78, 54-79 and

§§18-349.31 to 18-349.37, inclusive, of the Code of V ir

ginia, as amended).

Both the N .A.A.C.P. and the Legal Defense Fund

contended in the court below that Chapters 33 and 36

should not be construed to apply to them, or those associ

ated with them, because such a construction would deny

them, and those associated with them, due process of law

and the equal protection of the law secured by the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States.

The essence of the contention of the plaintiffs is that

the statutes in question are unconstitutional only if con

strued to apply to them. In other words, when the statutes

are applied to others they are constitutional and “ serve

useful ends” (B rie f of Fund, pp. 33 and 34).

The N .A .A .C.P. not only requested the court below to

construe Chapters 33 and 36 in light of certain constitu

tional contentions but also contended that the statutes

were unconstitutional if applied to its activities.

On February 25, 1959, the Circuit Court o f the City

of Richmond entered its final order. There, it was held

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

3

that certain activities of the plaintiffs were not within

the purview of Chapters 33 and 36 while certain other

enumerated activities, when conducted in the manner

shown by the evidence in these cases, amounted to viola

tions of Chapters 33 and 36.

The Circuit Court also held that the application of

Chapters 33 and 36 to the activities o f the N .A .A .C.P.

and those affiliated with it, did not deny it due process of

law or equal protection of the laws in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The court made no adjudication

on this question as to the Legal Defense Fund in view of

its contention that its pleadings did not raise or present

such a question for determination.

THE STATUTES INVOLVED

For the convenience of the Court, Chapters 33 and 36,

supra, are set forth as Appendix I and Appendix II of

this brief. They pertain to the regulation of the practice

of the law.

Chapter 33 amends and reenacts three sections of the

Code of Virginia, namely, §§54-74, 54-78 and 54-79. The

amendment to §54-74 broadens the definition of “mal

practice” to include the acceptance of employment from

a corporation with knowledge that such corporation has

violated a provision of Article 7, Chapter 4, Title 54, Code

of Virginia (§§54-78 to 54-83, inclusive). Section 54-78

broadens the definition of a “ runner” or “capper” to in

clude any person, association or corporation acting as an

agent for another person, association or corporation who

or which employs an attorney in connection with any

judicial proceeding in which such person, association or

4

corporation is not a party and has no pecuniary right or

liability therein.

The provisions of § 54-79 make it unlawful for a per

son, association or corporation to “ solicit any business”

for an attorney or any other person, association or corpo

ration.

Chapter 36 makes it unlawful for any person not having

a direct interest in a legal proceeding to give anything of

value “as an inducement” to any person to bring a lawsuit

against the Commonwealth, its officers, agencies or politi

cal subdivisions.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The following questions are presented by these cases:

1. Do the activities of the plaintiffs, or either of

them, amount to the solicitation of business prohib

ited by Chapter 33?

2. Do the activities of the plaintiffs, or either of

them, amount to an inducement to others to com

mence or further prosecute a lawsuit against the

Commonwealth, its officers, agencies or political sub

divisions ?

3. Do the provisions of Chapters 33 and 36 vio

late the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

At the trial of the cases, the plaintiffs filed as their

exhibit the complaints, defendants’ motions to dismiss and

answers, majority and dissenting opinions of the three-

5

judge federal district court and the judgment entered in

the case of National A ss’n. fo r Advancement of Colored

People v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (1958), together with

the transcript of the trial proceedings and certain plain

tiffs’ exhibits introduced therein.

The plaintiffs then rested upon the testimony of W.

Lester Banks, Executive Secretary of the Virginia State

Conference of the N A A C P. He testified that there was

no difference in the operation of the N A A C P, the Con

ference or its branches since September 1, 1956. No testi

mony was taken on behalf of the “ Fund.”

Before setting forth the defendants’ evidence, the plain

tiffs’ exhibits pertaining to the trial of the case of National

A ss’n. fo r Advancement of Colored People v. Patty, su

pra, will be reviewed in order to ascertain the organization

of the N A A C P and the “ Fund” and their operations.

The Organization of the NAACP

As pointed out, the N A A C P is a non-profit corporation

organized under the laws of New York. In the words of

its counsel, it is a political association for those who

oppose racial discrimination.

The Virginia State Conference is an unincorporated

association and is a constituent unit of the N A A C P,

being financially supported by contributions from local

branches and the national corporation.

The local branches of the N A A C P are unincorporated

associations that furnish financial support to the national

corporation. The N A A C P exercises such “ minimal” con

trol over its branches as is set forth in its “ Constitution

and By-laws for Branches.”

The “ minimal control” exercised by the N A A C P over

6

its branches is illustrated by its Constitution and By-laws

for Branches, in part, as follows:

Article I, Section 2 — The branch is subject to the

general authority and jurisdiction of the board of direc

tors o f the N A A CP.

Article II, Section 4 — The secretary must report to

the N A A C P all events affecting the interest of colored

people.

Article IV, Section 7 — The N A A C P has the power

to intervene in all election controversies.

Article IX , Section 1 — If the branches fail to report

to the N A A C P for a period of four months the board of

directors of the N A A C P may declare all offices of the

branch vacant and order a new election.

Article IX , Section 2 — The N A A C P may remove lo

cal officers for gross neglect of duty or conduct contrary

to the best interest of the N A A CP.

Article X — The charter of a local branch may be sus

pended or revoked by the N A A CP.

Article X I — A local branch may not adopt or amend

its by-laws without prior written approval of the N A A CP.

Roy Wilkins heads the staff of the N A A C P which is

responsible to the board of directors. The staff “preside

over the functioning of the local branches throughout the

country and the state conferences of branches” (Fed. Tr.,

p. 65). *

* “Fed. Tr., p..... ” refers to the page of the transcript of the testi

mony taken in the trial of the case of National Ass’n. for Advance

ment of Colored People v. Patty, supra (PI. ex. R-9).

7

Oliver W. Hill and Spottswood W. Robinson, III, are

members of the Legal Committee of the N A A C P as well

as being members of the Legal Committee of the Virginia

State Conference. Hill is also chairman of the last-men

tioned committee and Virginia counsel for the N A A C P

and its registered Virginia agent.

The Organization of the Legal Defense Fund

The Legal Defense Fund is a New York corporation

organized for the following purposes as stated in its

Certificate of Incorporation:

“ (a ) To render legal aid gratuitously to such Ne

groes as may appear to be worthy thereof, who are

suffering legal injustice by reason of race or color

and unable to employ and engage legal aid and assist

ance on account of poverty.

“ (b ) To seek and promote the educational facilities

for Negroes who are denied the same by reason of

race or color.

“ (c) To conduct research, collect, collate, acquire,

compile and publish facts, information and statistics

concerning educational facilities and educational op

portunities for Negroes and the inequality in the edu

cational facilities and educational opportunities pro

vided for Negroes out of public funds; and the status

of the Negro in American life.”

Thurgood Marshall is Director and Counsel of the

Legal Defense Fund and it is his duty to carry out the

policies of the board of directors. He has under his direc

tion a legal research staff of six full-time lawyers who

reside in New York City but who may be assigned to

places outside of New York (Fed. Tr., p. 254).

8

In addition to the full-time staff, the Legal Defense

Fund has lawyers in several sections of the country on a

retainer basis and, in addition, approximately one hundred

volunteer lawyers throughout the country that come in to

assist whenever needed (Fed. Tr., p. 252).

Spottswood W. Robinson, III, is the Southeast Region

al Counsel for the Legal Defense Fund on an annual re

tainer of $6,OCX). The Southeast region includes the

Commonwealth of Virginia.

The Legal Defense Fund also has at its disposal social

scientists, teachers of government, anthropologists and

sociologists, especially in school litigation (Fed. Tr., p.

266).

There is only a small number of members of the Legal

Defense Fund and no membership dues are required. Its

income is derived mainly from contributors who are so

licited by letter and telegram from New York City.

The Legal Defense Fund has been approved by the

State of New York to operate as a legal aid society because

of the provisions of the barratry statute of New York

(Fed. Tr., p. 311).

The Operation of the Legal Defense Fund

Thurgood Marshall testified that it is the policy of the

Legal Defense Fund before sending assistance in a legal

case that the case must be referred to it by either the party

directly in interest or the party’s attorney. When aid is

given, the party’s attorney is controlled solely by the

canons of ethics and “ by nothing or anybody else” (Fed.

Tr., p. 256).

The Legal Defense Fund does not cooperate if a case

is referred by an organization including the N A A C P

9

(Fed. Tr., p. 256). However, the lawyer who has already

been retained by the party receiving aid from the Legal

Defense Fund is always on the legal staff of the State

Conference of the N A A C P (Fed. Tr., p. 271).

When a so-called client comes to a member of the legal

staff of the State Conference, he may then receive aid,

not only from the full legal staff of the State Conference,

but also from the full legal staff of the Legal Defense

Fund, including the services of its southeastern regional

counsel (Fed. Tr., p. 277).

In the words of its Director and Counsel, the Legal

Defense Fund operates in the following manner:

“ * * * I f the investigation conducted either from

the New York office or through one of our local law

yers reveals that there is discrimination because of

race or color and legal assistance is needed, we will

furnish that legal assistance in the form of either

helping in payment of the costs or helping in the pay

ment of lawyers fees, and mostly it is legal research

in the preparation of briefs and materials of that type.

We are getting calls all the time.” (Fed. Tr., p. 254).

Costs, expenses and investigations of legal cases on

behalf of Negroes are borne by the Legal Defense Fund

(Fed. Tr., p. 277a). No other organization operating in

Virginia offers legal assistance and aid in cases involving

discrimination against Negroes (Fed. Tr., pp. 261-262).

Spottswood W. Robinson, III, testified that his duties

as regional counsel for the Legal Defense Fund were as

follows:

“ To engage in research of a legal character when

there is occasion therefor, to render service to parties

10

wlm may |ieraonttlly rc<|ucHt mo to do no to render

service for them, to render .service to litigants upon

the request of their attorneys, such latter services to

he rendered along with the services that their own

attorneys will render for them." ( h'cd. Tr., p. 34.1)

Robinson also testified in the following manner con

cerning’ the type of case that comes within the policy of

the Legal Defense Fund for paying attorneys’ fees and

costs:

"A . It is my understanding that once a principle

has been established as a matter of law, in other

words, the legal principle has been fixed, that under

those circumstances if it is simply a denial of a right

of a person remedial in damages that I have a right

to refuse to accept a person of that sort.

“ Q. If the principle has not been established, then

the Legal Defense Fund will pay your attorney’s fees

and will pay the costs of a suit by a private litigant

to recover damages for violation of civil rights?

“ A. That is correct, at least, that has been done

in the past.” (Fed. Tr., p. 347)

The testimony of Thurgood Marshall on cross-exami

nation indicated that the Legal Defense Fund represented

only those people who cannot afford to pay for litigation

(Fed. Tr., p. 312). However, he stated that he knew of

no instance in which an investigation was made to find out

whether or not any of the plaintiffs could pay the cost of

the school litigation in Arlington, Charlottesville, New

port News or Norfolk (Fed. Tr., p. 314).

Marshall further admitted that if a plaintiff owned real

estate with a fair market value of $15,000.00, free and

II

clear, lie would hr in pretty good shape to finance his own

lawsuit ( Fed. T r .( p, 315).

Robinson stated that his duties do not require him

to obtain a credit report or look extensively into the finan

rial situation of the parties who may request assistance

of the Legal Defense Fund ( Fed. Tr., p. 344). As to the

type of investigation conducted he stated:

“ I do not make an investigation beyond the point of

looking at the client, if the client comes into the office,

exercising judgment as to appearances as they do

appear, and considering those in the light of what I

am requested to do.” (Fed. Tr., p. 344)

Robinson further testified that the Legal Defense Fund

would represent all of the plaintiffs in a class action even

though all but one could afford the cost of the litigation

(Fed. Tr., pp. 355-356).

The Operation of the NAACP

Speaking of the legal activity of the N A A C P, Roy

Wilkins testified in the federal court:

“ Well, under legal activity we have sought to assist

in securing the constitutional rights of citizens which

may have been impaired or infringed upon or denied.

We have offered assistance in the securing of such

rights. Where there has been apparently a denial of

those rights, we have offered assistance to go to court

and establish under the Constitution or under the

federal laws or according to the federal processes, to

seek the restoration of those rights to an aggrieved

party.” (Fed. Tr., pp. 70-71)

12

Wilkins further testified that in assisting plaintiffs

“ we would either offer them a lawyer to handle their case

or to help to handle their case and pay that lawyer our

selves, or we would advise them, if they had their own

lawyer, would advise with them or assist in the costs of

the case” (Fed. Tr., p. 82). No money ever passes directly

to the plaintiff or litigant (Fed. Tr., p. 82).

The N A A C P does not ask a person if he wishes to chal

lenge a law. However, it does say publicly that it believes

that a certain law is invalid and should be challenged in

the courts. Negroes are urged to challenge such laws and

if one steps forward, the N A A C P agrees to assist (Fed.

Tr., p. 84).

Although it is not in the regular course of business,

prepared papers have been submitted at N A A C P meet

ings authorizing someone to act in bringing lawsuits and

the people in attendance have been urged to sign (Fed.

Tr., p. 86).

Robert L. Carter, General Counsel for the N A A C P, is

paid to handle legal affairs for the corporation. Repre

sentation of the various Virginia plaintiffs falls within

his duties (Fed. Tr., p. 125).

The N A A C P offers “ legal advice and assistance and

counsel, and Mr. Carter is one of the commodities” (Fed.

Tr., p. 125).

Thurgood Marshall was Special Counsel for the

N A A C P prior to 1957 and it was his job “ to advise with

lawyers and the people in regard to their legal rights and

to render whatever legal assistance could be rendered”

(Fed. Tr., p. 308).

The State Conference has a legal staff composed of

13

fifteen members and in every instance except two the

plaintiffs have been represented by members of such staff

in cases in which assistance is given.

All prospective plaintiffs are referred to the Chairman

of the Legal Staff, Oliver W. Hill, and counsel for such

plaintiffs makes his appearance when Hill has recommend

ed that they have a “ legitimate situation that the N A A C P

should be interested in” (Fed. Tr., p. 39).

The State Conference assists in cases involving dis

crimination and the Executive Board formulates certain

policies to be applied in determining whether assistance

will be given. Hill then applies these policies and when he

decides that the case is a proper one, it is taken “auto

matically” with the concurrence of the President (Fed.

Tr., p. 47).

Members of the Legal Staff of the State Conference

may attend meetings held by the branches in their capacity

as counsel for the Conference and either the particular

branch or the State Conference pay the traveling expenses

incurred (Fed. Tr., p. 59).

Oliver W. Hill testified that he is not compensated as

chairman of the Legal Staff. It is his duty to advise

Negroes who come to him voluntarily “or directly from

some local branch, or after having been directed there by

Mr. Banks” whether or not he will recommend to the

State Conference that their case will be accepted (Fed.

Tr., p. 131).

A fter a case is accepted, Hill selects the lawyer (Fed.

Tr., pp. 134-135). He refers the case to a member of the

Legal Staff residing in the particular area from which the

complaining party came. For the Richmond area, “ one of

14

us would frequently handle the situation” (Fed. Tr., p.

133).*

A bill for the legal services is submitted to Hill who

approves it with the concurrence of the President of the

State Conference (Fed. Tr., p. 135).

Hill further stated that no investigation is made as to

the ability of the plaintiffs to pay the cost of litigation.

He feels that irrespective of wealth, a person has the right

“ to get cooperative action in these cases” (Fed. Tr., p.

156).

At the trial of these cases in the court below, W. Lester

Banks testified on cross-examination that none of the

school segregation cases were referred to Oliver W. Hill,

Chairman of the Legal Committee of the State Confer

ence, by him. In every instance the individual plaintiffs

made contact with Hill or other members of his legal

staff, and not through the Virginia State Conference (R.

p. 63).

Generally, plaintiffs in the school segregation cases do

not contribute toward expenses and legal fees though they

are solicited and do contribute in the N A A C P ’s Freedom

Fund (R . p. 72).

Banks, as Executive Secretary of the State Conference,

speaks at meetings and urges citizens to look about them

for discriminatory conditions, as do other representatives

of the Conference. Individuals are also urged to assert

their constitutional rights (R . p. 75).

* It should be noted that Hill as well as Spottswood W. Robinson,

III, also a member of the Legal Staff of the State Conference, both

being residents of Richmond, not only represented all the plaintiffs

as counsel of record in the Prince Edward, Arlington, Charlottes

ville, Newport News and Norfolk school segregation cases, but took

active and leading parts in the trial of said cases.

i

15

The chairman of the legal staff (H ill) approves every

item of expense and all legal fees paid by the Conference.

The president of the Conference approves the legal fees

and expenses of Chairman Hill. Further, in every in

stance, the president has approved the recommendations

of the chairman (R . p. 94).

The legal staff became an official committee of the State

Conference in 1945 or 1946 (R . p. 102). Its members are

elected at the annual convention of the State Conference

after being nominated by a nominating committee which,

in turn, gets its recommendations for candidates from the

legal staff (R . p. 103). The legal committee, in a sense,

perpetuates itself in this manner since there has never

been additional nominations from the floor of the Conven

tion (R . p. 104).

Lawyers who wish to become members of the legal

committee of the State Conference may request the presi

dent of his local branch to recommend him to the com

mittee or he may be recommended by a member of the

legal committee (R . p. 104).

Without exception, when a member of the legal com

mittee brings a lawsuit in his community he requests other

members of the committee to be associated with him (R .

p. 106).

The State Conference pays the expenses and fees of its

lawyers for each case with the exception of the fees of

Robinson which are paid by the “ Fund” in the form of an

annual retainer (R . pp. 107-108).

Since there was some question of whether the provi

sions of Chapters 33 and 36 would prohibit the payment

of expenses and fees by the State Conference some of the

litigants in the various school segregation cases were in

16

formed that they might have to pay the costs of the

N A A C P lawyers (R . p. 108). However, since July, 1956,

the State Conference has paid to members of its legal

committee for services and expenses incurred in school

litigation the sum of $ 12,378.61. ( See defendants’ exhibit

D-3 set forth as Appendix III to this brief.) Further,

Banks stated that he expects the State Conference to

receive more outstanding bills for services rendered by

Hill (R . p. 215).

The initial contact in the Charlottesville school segre

gation case was made by the president of the local branch

of the N A A C P requesting Hill to speak with certain par

ents of school children residing in Charlottesville (R . p.

109). The parents then signed papers, some of which

authorized Hill to represent such parents and their chil

dren. Other authorization forms passed out at the meet

ing were signed with no attorney’s name appearing. Hill

filled in his name as attorney on these after he returned to

his office in Richmond (R . p. 109).

Authorization forms for use in all the school segrega

tion cases were prepared by Hill for his use and the use

of other lawyers on the legal committee of the State Con

ference (R . p. 109). The form was so written as to

authorize a particular attorney to associate such other

attorneys as he saw fit (R . p. 110).

In the Charlottesville case Hill first associated Robin

son, Martin, Ely and Tucker, the first three being from

Richmond and Tucker residing in Emporia, Virginia (R .

p. 110). The General Counsel for the N A A C P also came

down from New York for the trial of the Charlottesville

case (R . p. 110). All of the Virginia lawyers were, of

course, members of the legal committee of the State Con

17

ference and are paid at the rate of $60.00 per day for their

services. (See plaintiffs’ exhibit R-18, which states that

“ the Conference agree to pay $60.00 per diem to attorneys

as long as such attorneys adhere strictly to N A A C P

policies” .)

Upon examination, Hill conceded that the State Con

ference could have done without the services of Tucker

but “ it was felt that it would be advisable and helpful if

as many as possible of the lawyers who were in a particu

lar community had some participation in the [school seg

regation] cases” (R . p. 111). The idea was to train law

yers for future school segregation cases (R . p. 111).

The authorization form used by the litigants in the

Prince Edward case authorized the firm of Hill, Martin

and Robinson as attorneys. It did not authorize the asso

ciation of other attorneys (R . p. 120 and plaintiffs’ ex

hibits R-12, R-13, R-14 and R-15). However, Hill testi

fied that the General Counsel of the N A A C P was associ

ated because:

“We don’t regard the prosecution of a person’s

constitutional rights with the same strictness that

you would regard, say, handling a contract litigation

for a particular individual client. This is something

that the N A A C P was sponsoring. These people are

actively connected with the N A A C P and known to

be, and these people whose rights we are trying to

protect and assert are interested in getting the vindi

cation of their rights, and they are not as much con

cerned about the particular lawyers in the majority

of instances— as to the number of lawyers, put it that

way— as a client would be who was involved in a par

ticular single piece of private litigation.” (R . p. 120)

18

Hill stated that it was well understood in civil rights

cases that members of the N A A C P and Negroes are en

titled to representation by attorneys on the legal committee

of the State Conference without cost to them (R . pp. 112-

113 and 121). Negroes were informed of this by Hill

and others in the press, in conventions and in meetings of

local branches (R . p. 113).

Hill also testified that it was generally expected that

the State Conference would “ sponsor” cases as long as

the litigants adhered to the principles and policies of the

Conference, namely, that a school case must be tried as a

direct attack on segregation (R . p. 113).

S. W. Tucker of Emporia, a member of the legal com

mittee of the State Conference, stated that his duties were

“ to do whatever was necessary to advance our program.

That would entail a study of cases, preparation of cases,

trial of cases” (R . p. 231). He was never employed or

compensated by the State Conference prior to his mem

bership on the legal committee (R . p. 232). He entered

Charlottesville and Warren County school segregation

cases at the suggestion of Hill and his relationship with

Chairman Hill “has been so pleasant and so profitable”

(R . pp. 236-237). Tucker further stated that he handled

cases all over the state for the Conference and received a

per diem of $60.00 for his services (R . p. 237).

The defendants introduced certain exhibits to show

the policies of the N A A C P, the State Conference and its

branches, as well as the activities carried on pursuant

thereto. For example, exhibit D-10 is a copy of a letter

written by the Chairman of the Legal Committee, Oliver

W. Hill, to W. Lester Banks, Executive Secretary of the

Virginia State Conference concerning the feasibility of

19

N A A C P participation in a labor suit involving the State

as the plaintiff and Robert Edwards and Willie Savage as

defendants. The attorney for the defendants requested

financial aid. Hill stated that it was contrary to the policy

of the State Conference to grant financial aid in cases not

handled by the N A A CP.

Exhibit D-4 is a copy of a letter written by the Execu

tive Secretary of the State Conference dated July 1, 1953,

wherein he stated that the N A A C P was not a legal aid

society. It rendered aid in criminal cases only when inno

cent Negroes had been charged with a crime solely because

of race or color, or had been convicted of a crime when

denied a proper jury trial, when a confession had been

extorted through use of force, or when the accused had

been denied the effective use of counsel. Banks testified

that the statements contained in this exhibit still correctly

state the policy of the Virginia State Conference (R .

p. 222).

Defendants’ exhibits D-7 and D-9 show that all mem

bers of the N A A C P and their attorneys cannot partici

pate in any lawsuit which seeks to secure separate but

equal facilities. The contents of exhibit D-9, being a letter

from Spottswood W. Robinson, III, to Reverend N. W.

McNair, reads as follows:

“ This is with reference to the matter, recently dis

cussed with me, of participation by this office drafting

a reply to a letter received by your group by the

County School Board of Amelia County.

“ Upon our conference you advised that the effort

of your group is to obtain consolidation of Negro

elementary schools in said county, and that the effort

is limited to this objective.

20

“A s you were then advised, it is not possible either

for this office or the N A A C P to lend assistance in

connection with this effort. In June, 1950, the A sso

ciation adopted a policy requiring that all education

cases seek facilities and opportunities on a racially

nonsegregated basis. This policy is binding upon all

Association attorneys, and it is apparent that the

plans of your group do not conform to this policy.

“ At your request, Mr. W. Lester Banks, Executive

Secretary, Virginia State Conference, N A A C P, was

contacted, and he is arranging to visit your group at

an early date to more fully explain the Association’s

policy and its recommendation as to educational mat

ters in your county.”

Defendants’ exhibit D-5 likewise states the policy of the

Virginia State Conference which is to eliminate racial

segregation in public schools rather than seek separate

but equal facilities.

Part of the defendants’ exhibit D -l is a letter dated

May 26, 1954, from the Executive Secretary of the V ir

ginia State Conference to all of its members calling for a

meeting to be held in Richmond on June 6, 1954, to “devel

op techniques to put into immediate effect the N A A C P ’s

Atlanta Declarations.” Banks also stated in this letter:

“ * * * No conferences, petitions or other negotiations

should be engaged in by N A A C P or other responsible

leaders with local school officials until after the June 6

meeting.”

Another letter from the Executive Secretary to the local

branches, dated June 16, 1954, dealt with petitions to local

school boards and requested the local branches to withhold

their proceedings with respect to desegregation until com

pletion of the organization of the State Conference’s pro

21

gram. However, forms of petitions prepared by N A A C P

legal department in New York in collaboration with the

attorneys on the legal committee of the State Conference

were forwarded to the various local branches directly from

New York.

The last part of exhibit D -l is styled a “ confidential

directive” , dated June 30, 1955, to the local branches and

signed by the Executive Secretary of the Virginia State

Conference which dealt with the method of processing

petitions. It reads in part as follows:

“ (1 ) • For your convenience we are enclosing four

petitions (2 to the Secretary, and 2 to the President).

Upon receipt of the petitions, the Chairman of your

Education Committee or another responsible branch

official will fill in the appropriate spaces designating

(a ) County or city, (b ) name of School Board, and

(c) name of your Division Superintendent. Do not

fill in the last two lines at the bottom of petition.

“ (2 ) . Petitions will be placed only in the hands of

highly trusted and responsible persons to secure sig

natures of parents or guardians only. Each petition

has an attached sheet for the signatures of 35 names

and addresses. I f a petition bearer needs additional

space, provide one or more of the extra sheets being

sent under separate cover.

“ (3 ) . Petitions are to be signed by parents or

guardians themselves, and if they cannot write some

one can sign for them letting them make an (X )

mark, but be sure to have a witness to this fact.

“ (4 ) . In event a petitioner’s handwriting is not

readible, the bearer of the petition should— in a tact

ful manner— secure the name and address of the peti

tioner and attach it to the petition (example: line 15

22

reads; Mrs. Lucy Wright, Route 1, Box 295, Old-

town, V irginia).

“ (5 ) . Signatures should be secured from parents

or guardians in all sections of the county or city.

Special attention should be given to persons living in

mixed neighborhoods, or near formerly white schools.

“ (6 ) . The signing of the petition by a parent or

guardian may well be only the first step to an extend

ed court fight. Therefore, discretion and care should

be exercised to secure petitioners who will— if need

be— go all the way.

“ (7 ) . Set an early deadline when petitions will be

returned to your Education Committee’s Chairman.

The quicker they are returned, the sooner your peti

tion can be filed.

“ (8 ) . The Education Committee’s Chairman will

forward completed petitions to the Executive Secre

tary of the State Conference. The Chairman of the

Education Committee, or other responsible branch

official will furnish the State Secretary, at the time

of transmittal of petitions, the name and location of

meeting site.

“ (9 ) . Immediately upon receipt of petitions by the

State Secretary, he will notify all the petitioners and

branch officials that an emergency meeting will be

held at the meeting site designated by the branch

official.

“ (10 ). At that meeting, everyone will be advised

as to the next steps. It is absolutely necessary that

all of the petitioners be present at this meeting.”

The directions quoted above were established and adopt

ed by an emergency southwide N A A C P conference held

23

in June, 1955, as shown by the defendants’ exhibit D-8.

It reads in part as follows:

“ * * * it is the job of our branches to see to it

that each school board begins to deal with the prob

lem of providing non-discriminatory education. To

that end we suggest that each of our branches take

the following steps:

“ 1. File at once a petition with each school board,

calling attention to the May 31 decision, requesting

that the school board act in accordance with that deci

sion and offering the services of the branch to help

the board in solving this problem.

“2. Follow up the petition with periodic inquiries

of the board seeking to determine what steps it is

making to comply with the Supreme Court decision.

“ 3. All during June, July, August and September,

and thereafter, through meetings, forums, debates,

conferences, etc., use every opportunity to explain

what the May 31 decision means, and be sure to em

phasize that the ultimate determination as to the

length of time it will take for desegregation to be

come a fact in the community is not in the hands of

politicians or the school board officials but in the

hands of the federal courts.

“ 4. Organize the parents in the community so that

as many as possible 'will be fam iliar with the proce

dure when and if law suits are begun in behalf of

plaintiffs and parents.

“ 5. Seek the support of individuals and commu

nity groups, particularly in the white community,

through churches, labor organizations, civic organi

zations and personal contact.

24

“6. When announcement is made of the plans

adopted by your school board, get the exact text of

the school board’s pronouncements and notify the

State Conference and the National Office at once so

that you will have the benefit of their views as to

whether the plan is one which will provide for effec

tive desegregation. It is very important that branches

not proceed at this stage without consultation with

State offices and the National office.

“ 7. I f no plans are announced or no steps tozvards

desegregation taken by the time school begins this

fall, 1955, the time fo r a lazv suit has arrived. At

this stage court action is essential because only in

this way does the mandate of the Supreme Court that

a prompt and reasonable start towards full compli

ance become fully operative on the school boards in

question.

“ 8. At this stage the matter zvill be turned over

to the Legal Department and it zvill proceed with the

matter in court.” (Emphasis added)

A memorandum written by Banks and introduced and

marked as defendants’ exhibit D-2 shows that the

N A A C P and the Virginia State Conference have con

tinued the policies and activities outlined above. It reads

in part as follow s:

“ IV. Up to Date Picture of Action by N A A C P

Branches Since M ay 31.

“ A. Petitions filed and replies

A total of 55 branches have circulated peti

tions.

“ B. Where suits are contemplated

Petitions have been filed in seven (7 )

25

counties/cities. Graduated negative re

sponse received in all cases.

“ C. Readiness of lawyers for legal action in

certain areas

Selection of suit sites reserved for legal

staff.

State legal staff ready for action in selected

areas.

“ D. Do branches want legal action

The majority of our branches are willing

to support legal action or any other pro

gram leading to early desegregation of

schools that may be suggested by the na

tional and state Conference offices. Our

branches are alert to overtures by public

officials that Negroes accept voluntary ra

cial segregation in public education.”

Banks explained that the language, “ Where suits are

contemplated” referred to places where petitions had been

denied by local school boards (R . p. 217). The language

“ Readiness of lawyers for legal action in certain areas”

meant financial aid was available (R . p. 218). Finally,

the language “ Selection of suit sites reserved for legal

staff” meant that members of the legal committee of the

State Conference would pick the places where lawsuits

would be brought (R . p. 219).

Barbara S. M arx, one of the plaintiffs in the Arlington

school segregation case, testified that she is vice president

of the local branch of the N A A C P in Arlington County.

Before the commencement of the Arlington case she

signed a petition which was received by the local branch

26

directly through the mail from the State Conference in

Richmond (R . p. 171). The petition was then discussed

in a branch meeting and she helped circulate it. Mrs.

M arx also talked with Hill and Robinson about whether

legal action would follow the refusal of the petition by the

school board (R . p. 172). She also stated that she knew

that Hill and Robinson would be the lawyers when the

time came to file the Arlington school segregation suit

(R . pp. 172-173).

Other litigants in the school cases from Arlington,

Charlottesville and Newport News were examined by the

defendants. All of them, with one exception, stated that

they had paid no attorney’s fees and that no bills for serv

ices rendered had been submitted. Some declared that

they would pay if a bill was rendered, while others said

they expected the N A A C P to pay the cost of attorney’s

fees. See Appendix IV.

Some of the litigants examined also stated that they

had no personal contact with the attorneys of the N A A CP.

Others stated that N A A C P attorneys were used since

they were members of the N A A CP. Only one litigant

examined by the defendants stated that she would have

brought suit even if the N A A C P had not agreed to

finance it.

Nineteen litigants were examined concerning their

yearly family income and such income ranged from a low

of $3,500 to an estimated high of between $13,000 to

$17,000. See Appendix IV. Thus, of nineteen litigants

examined, the yearly family income averaged approxi

mately $7,000 for each.

Ten litigants were examined concerning the value of

27

real property owned by them. These estimates ranged

from a low of $12,000 to a high of $87,000. See Appen

dix IV. The average of the value of real estate thus held

approximates $35,000 for each litigant.

The statements of the facts set forth above is the evi

dence material to the consideration of the questions pre

sented and will be summarized and discussed where nec

essary in the defendants’ argument.

A s to the plaintiffs’ statement of facts, it should be

pointed out that the contributions and aid toward the

prosecution of lawsuits are largely in the form of fur

nishing attorneys who are members of the legal commit

tee of the Virginia State Conference. The record shows

that the only financial aid furnished is the payment of

court costs and other such expenses of litigation.

The N A A C P representatives and officers publicly urge

Negroes to assert their constitutional rights so it cannot

be stated that the Association does not act until some indi

vidual comes to it for help. (See defendants’ exhibit D-8

and Tr., pp. 40, 41, 108 and 109.)

The statement that the Association does not direct or

control litigation is also false. The N A A C P has absolute

direction and control. (See defendants’ exhibits D-7 and

D-9 and Tr., p. 108.)

The plaintiffs state that legal aid and assistance is

granted where the litigant is financially unable to bear the

cost o f the litigation. Again, this is not true. No investi

gation of the financial condition of litigants is made (Fed.

Tr., pp. 156 and 344). The record also shows affirmatively

that many litigants are able to finance their own lawsuit

(Fed. Tr., p. 315 and Appendix IV to this brief).

28

ARGUMENT

I.

Certain Activities of the Plaintiffs

Are Prohibited by Chapter 33

First of all, a corporation cannot practice law and it is

a misdemeanor to do so without authority. Sections 54-42

and 54-44, Code of Virginia, and Richmond A ss’n of

Credit Men v. B ar Association, 167 Va. 327 (1937).

In its definition of the practice of law, this Court has

said:

“ The relation of attorney and client is direct and

personal, and a person, natural or artificial, who un

dertakes the duties and responsibilities of an attorney

is none the less practicing law though such person

may employ others to whom may be committed the

actual performance of such duties.” (171 Va. xvii)

Costs, expenses and investigations of legal cases are

borne by the Legal Defense Fund and legal assistance and

aid in cases involving discrimination against Negroes

include the legal services of its Southeastern Regional

Counsel who is on an annual retainer for such purposes.

Counsel for the Legal Defense Fund also renders legal

assistance to Negroes by representing them in court and

otherwise. Further, the Legal Defense Fund maintains

a full-time legal staff of six attorneys to conduct research

and render legal advice to Negroes.

The N A A C P employs a general counsel, Robert L.

Carter, and one of his duties has been to represent the

various plaintiffs in the school segregation cases. The

29

N A A C P offers “ legal advice and assistance and counsel,

and Mr. Carter is one of the commodities.”

The State Conference, which is the “arm” of the

N A A C P in Virginia, has a legal staff of fifteen lawyers,

and all prospective plaintiffs are referred to the chairman

thereof to determine whether they have “a legitimate sit

uation that the N A A C P should be interested in.” I f they

do, a member of the legal staff will represent them in

court and will be paid by the State Conference.

The activities of the plaintiffs are prohibited by Rich

mond A ss’n. of Credit Men v. B ar Association, supra.

There, the credit association undertook to effect collec

tions of business accounts first by personal calls or letter

and then by employment of an attorney selected by it. The

fees of such lawyer were fixed by the association and it

held itself out to be in the business of collecting liquidated,

commercial accounts. Furthermore, the association so

licited claims both from its own members and others. In

the letter employing the lawyer, the association purported

to act “as agent for the creditor.” It was held to be en

gaged in the unauthorized practice of law.

The clients or complainants usually come directly to the

Legal Defense Fund or the State Conference at which

time they are referred to either the lawyer retained by the

Legal Defense Fund or a member of the legal staff of the

State Conference who serves in that capacity without

compensation. Under such circumstances the following

language found in the Richmond A ss’n. o f Credit Men

case is pertinent:

“ ‘The relation of attorney and client is that of

master and servant in a limited and dignified sense,

30

and it involves the highest trust and confidence. It

cannot be delegated without consent, and it cannot

exist between an attorney employed by a corporation

to practice law for it, and a client of the corporation,

for he would be subject to the directions of the cor

poration, and not to the directions of the client.’

Re Co-Operative Law Co., 198 N. Y. 479, 92 N. E.

15, 16, 32 L. R. A. (N . S .) 55, 139 Am. St. Rep. 839,

19 Ann. Cas. 879.” (167 Va. at p. 335)

On August 26, 1957, in the case of Virginia State B ar

v. Schmidt & Wilson, the Law and Equity Court of the

City of Richmond entered a declaratory decree and per

manent injunction against a real estate corporation for

engaging in practices constituting the illegal practice of

law. It reads in part as follows:

“ The Court doth adjudge and decree that the fol

lowing practices when engaged in by a real estate

broker, constitute the illegal practice of law, to-wit:

“ (a ) Advertising in a newspaper that it will provide

the services of an attorney at law for its

patrons.

“ (b) Providing, for compensation, legal services to

its patrons in the preparation of deeds and

deeds of trust and in advising them with regard

to the legal problems incident to real estate

transactions, and

“ (c) Representing its patrons in Court in the collec

tion of rent and other matters.”

Subsequent to the Richmond A ss’n. of Credit Men case,

a credit association changed its method of procedure by

permitting the creditor to select and employ the attorney.

31

However, the attorney was to advise the association of

the progress with regard to the collection. It was held by

the Committee of the Virginia State Bar on Unauthorized

Practice of Law that the procedure of the attorney report

ing to a lay agency acting as an intermediary amount to

the unlawful practice of law. Ninth Annual Report of

the Virginia State Bar, p. 37. See, also, Opinion dealing

with corporate real estate rental agent in Seventeenth

Annual Report of the Virginia State Bar, p. 32.

In the Ninth Annual Report of the Virginia State Bar,

p. 39, the Committee on Unauthorized Practice also ren

dered an opinion which is pertinent to consider. The facts

were that a union retained an attorney on a salary basis

to represent all o f its individual members in their claims

for compensation before the State Industrial Commission.

He received no fees from the individuals for such repre

sentation, his sole compensation coming from the salary

paid him by the union. The Committee held that the

union was a lay agency practicing law without a license;

that it was selling the services of a lawyer and intervening

between him and his clients; and that the attorney was in

violation of the Canons of Ethics.

At this time, it is also important to note that Canon 47

of the Canons of Professional Ethics adopted and promul

gated by this Court reads as follows:

“ Aiding the Unauthorized Practice of Law.— No

lawyer shall permit his professional services, or his

name, to be used in aid of, or to make possible, the

unauthorized practice of law by any lay agency, per

sonal or corporate.” (171 Va. xx xv )

Evidence was produced to show that some of the plain

32

tiffs in the school segregation cases had no personal rela

tion with the attorneys for the N A A C P or the Legal De

fense Fund. Furthermore, the attorneys submitted their

bills to the State Conference and not to their so-called

clients, Robinson being paid by the Legal Defense Fund.

It should also be again pointed out that neither the

N A A C P, its State Conference nor the Legal Defense

Fund make any investigation as to the financial condition

of the individual plaintiffs.

Canon 35 reads in p art:

“ Intermediaries.— The professional services of a

lawyer should not be controlled or exploited by any

lay agency, personal or corporate, which intervenes

between client and lawyer. A lawyer's responsibili

ties and qualifications are individual. He should avoid

all relations which direct the performance of his

duties by or in the interest of such intermediary. A

lawyer’s relation to his client should be personal, and

the responsibility should be direct to the client. Char

itable societies rendering aid to the indigent are not

deemed such intermediaries.” (171 Va. xxx ii)

The Committee on Legal Ethics of the Virginia State

Bar has had the occasion to render opinions under the

Canons of Professional Ethics and Opinion No. 10 dealt

with a corporation which desired to employ an attorney to

consult with its employees as to their personal legal prob

lems. The corporation’s interest was to prevent time lost

from work and the duties of the attorney were to handle

only simple legal problems. In more complex cases, such as

lawsuits, the employees would be advised by the attorney to

consult an attorney of their own choosing. The corporation’s

attorney would, however, represent the employee if request

33

ed, charging a reasonable fee to be paid by the employee.

The Committee held that the acceptance of such employ

ment by the attorney would be unethical. Ninth Annual Re

port of the Virginia State Bar, p. 32. See, also, Fifteenth

Annual Report of the Virginia State Bar, p. 34, Opinion

No. 41 dealing with a printing firm offering the services

of an attorney to prepare briefs.

Opinion No. 43 involved an attorney who was to be

employed by a hospital and furnished with an office there

in. He was to collect accounts and advise patients on hos

pital insurance policies held by them. The Committee

ruled that it would be improper for the said attorney to

represent patients of the hospital in personal injury claims.

Fifteenth Annual Report of the Virginia State Bar, p. 34.

In Opinion No. 45 a Virginia attorney wished to form

a corporation to sell insurance policies to persons to fur

nish them legal services up to a limited amount of fees, the

insured to choose his own attorney. The Committee held

that it would be improper to insure reimbursement for a

plaintiff’s attorney fees because to do so would incite,

encourage and promote litigation. Sixteenth Annual Re

port o f the Virginia State Bar, p. 30.

Section 54-74 of Chapter 33 condemns the practice of

law without a license and paragraph (6 ) thereof defines

malpractice to be the acceptance of compensation by an

attorney from a corporation which is guilty of practicing

law. Thus, it can be seen that the provisions of Chapter 33

not only apply to the plaintiff corporations but also apply

to their attorneys.

Furthermore, it is clear from the record that the actions

of the N A A C P cannot be separated from the actions of

the Virginia State Conference and its local branches. It

34

is equally clear that the activities of these organizations,

their officers and agents come within the provisions of

§ 54-78 of Chapter 33 and amount to the solicitation of

business prohibited by § 54-79 thereof.

For example, the Executive Secretary of the Virginia

State Conference testified as follows:

1. Prospective plaintiffs come to the State Con

ference for assistance (Fed. Tr., p. 27).

2. When complaints are received they are referred

to the legal committee of the State Conference (Fed.

Tr., p. 37).

3. All cases in which the State Conference pay

attorneys’ fees are, in almost every instance, handled

by members of its legal staff (Fed. Tr., pp. 41-42).

4. The State Conference attempts to educate Ne

groes as to civil rights and inform them how such

rights may be enforced (Fed. Tr., p. 33).

Defendants’ exhibits D -l, D-7, D-8 and D-9 are other

examples of how the N A A C P solicits business for its

attorneys and completely directs and controls litigation.

The testimony of the president of the Charlottesville

branch and the vice president of the Arlington branch also

make it clear that the N A A C P solicits business in viola

tion of Chapter 33.

Sections 54-78 and 54-79 are also applicable to the

Legal Defense Fund. It is uncontradicted that this cor

poration holds itself out to render legal services to Ne

groes. By doing so, it solicits business for its attorneys,

one of which is Robinson. Without such solicitation, there

35

would be no need to retain Robinson and others on a

yearly basis.

n.

Chapter 36 Is Applicable to Some of the

Activities of the Plaintiffs

Chapter 36 prohibits the offering or giving, or agreeing

to receive, or accepting, or soliciting or requesting, any

thing of value “as an inducement” to another to commence

or further prosecute a lawsuit against the Commonwealth

or any of its agencies or political subdivisions. Certain

exceptions are made, namely,

1. I f the person has a personal right in the litigation ;

2. I f the person has a pecuniary right in the litigation ;

3. I f the person is related by blood or marriage to the

plaintiff ;

4. I f the person occupies a position of trust with the

plaintiff; and

5. I f the person stands in the position of loco parentis

with the plaintiff.

It is also provided that Chapter 36 shall not be con

strued to prohibit the constitutional right of “ regular

employment of any attorney at law.” Furthermore, legal

advice must be sought in accordance with the Virginia

canons of legal ethics.

The common law of England is in force in Virginia.

See § 1-10, Code of Virginia, 1950. Chapter 36 defines

the common law crime of maintenance. There are many

36

and varied definitions given in the reported cases concern

ing maintenance. However, strictly speaking, maintenance

is the assisting of another person in a lawsuit without hav

ing any privity or concern in the subject matter. Wick

ham v. Conklin, 8 Johns (N . Y .) 220, 228.

Maintenance is, perhaps, best defined in Blackstone’s

Commentaries, Book 4 at p. 135 as :

“ an officious intermeddling in a suit that no way be

longs to one by maintaining or assisting either party,

with money or otherwise, to prosecute or defend it.”

Most of the reported cases hold that a person does

not act “ officiously” by furnishing money or other help

when:

1) he has a personal right involved;

2 ) he has a pecuniary right involved;

3) he is connected by consanguinity or affirmity to the

litigant; or

4) he stands in relationship as landlord and tenant or

master and servant with the litigant.

See Nichols v. Bunting, 3 Hawks (N . C .) 86 and

M ’Intyre v. Thompson, 10 F . 531 (W . D. N. C .).

It can thus be seen that the provisions of Chapter 36

substantially conform to the common law definition of the

crime of maintenance. Further, the record of the activi

ties of the plaintiffs make it plain that they do not come

within the exceptions enumerated therein.

In Thursten v. Percival, 18 Mass. (1 Pick.) 415, 416,

maintenance was defined as follows:

37

“ Maintenance is strictly prohibited by the common

law, as having a manifest tendency to oppression by

encouraging, and assisting persons to persist in suits

which perhaps they would not venture to go on in

upon their own bottoms.” (Em phasis added)

The proper interpretation of the word, “ inducement” ,

as used in Chapter 36, must now be considered to deter

mine whether the activities of the plaintiffs come within

the meaning of that word.

The defendants agree that penal statutes must be strict

ly construed. However, it is equally true that in constru

ing penal statutes the legislative intent is to be found by

giving words the meaning in which they are used in ordi

nary speech. See Tiller v. Commonwealth, 193 Va. 418,

420; Board of Supervisors v. Boas, 176 Va. 126, 130; and

Gates & Sons Co. v. Richmond, 103 Va. 702, 707.

Webster’s New International Dictionary (2nd ed., un

abridged) defines “ induce” as, “ to lead on; to influence;

to prevail on; to move by persuasion or influence.” Also,

“ inducement” is a synonym for “ incentive, reason, influ

ence.”

In cases construing the National Labor Relations Act,

the Mann Act and the California Narcotics Law, the word

“ induce” is construed to mean nothing more than “ encour

age.” See International Brotherhood v. N L R B , 341 U. S.

694 (1 9 5 1 ); LaP age v. United States, 146 F. (2d) 536

(8th Cir., 1945); and People v. Drake (Cal., 1957), 310

P. (2d) 977.

In the case of Commonwealth v. Mason, 175 Pa. Supp.

576, 106 A. (2d) 877 (1954), the court considered a sec

tion of the Pennsylvania Securities Act and found that

38

there had been an inducement in violation thereof. It was

pointed out that the word induce includes every form of

influence and persuasion and does not necessarily include

any element of fraud or coercion. See, also, Restatement

of Torts, §766.

Induce means to influence, to persuade, to encourage.

This being true, there can be no question that the activities

of plaintiffs are such as to induce Negroes to bring or

further prosecute lawsuits aghinst agencies of the Com

monwealth.

Only one witness, out of some twenty-four litigants in

school cases, testified that she would have brought a law

suit even if the N A A C P had not agreed to finance it.

Further, the exhibits introduced by the defendants make

it abundantly clear that the plaintiffs encourage and influ

ence the bringing of lawsuits. Finally, the plaintiffs’ own

summary of their activities admits o f encouragement,

persuasion and influence of prospective litigants.

To conclude, it is appropriate to again quote from ex

hibit D-8 as follows:

“4. Organize the parents in the community so

that as many as possible will be familiar with the

procedure when and if law suits are begun in behalf

of plaintiffs and parents.

* * *

“ 7. I f no plans are announced or no steps towards

desegregation taken by the time school begins this

fall, 1955, the time for a law suit has arrived. At this

stage court action is essential because only in this

way does the mandate of the Supreme Court that a

prompt and reasonable start towards full compliance

become fully operative on the school boards in ques

tion.

39

“ 8. At this stage the matter will be turned over to

the Legal Department and it will proceed with the

matter in court.”

m .

Freedom of Speech and Chapters 33 and 36

The plaintiffs contend that the provisions of Chapters

33 and 36 violate their freedom of speech and assemblage

and restrain their political activities. Such cases as Wat

kins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 and Sweezy v. New

Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, are cited.

In the Watkins case, supra, a congressional committee

inquired of a witness as to his associations in 1947. The

witness refused to identify his associates during that

period on the ground that he did not now believe they

were identified with the Communist Party. The Supreme

Court held that Congress had not authorized an investiga

tion of this nature and stated that a conviction of con

tempt for refusal to answer a question propounded by a

congressional committee must necessarily depend upon the

authority of the committee. In other words, there was no

relationship between an inquiry as to past associations and

the purpose for which the congressional committee was

formed.

In Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra, the Supreme

Court also held that questions propounded a witness by a

legislative committee concerning past associations were

not authorized by the Legislature.

The above-mentioned cases obviously are not control

ling here. Chapters 33 and 36 do not prohibit the plain

tiffs’ freedom to speak or to join. They prohibit, under

40

certain circumstances, the financing of lawsuits and the

solicitation of litigants.

The defendants also agree that under the holding in

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, a case cited by the plain

tiffs, there is some doubt as to whether mere statements at

public meetings would be considered solicitation rather

than an exercise of free speech. However, the plaintiffs

do more. All of the litigants, or prospective litigants, in

the school segregation cases are referred by representa

tives of the plaintiffs to the attorneys on the legal com

mittee of the Virginia State Conference. Lay agencies

thus funnel legal business to selected lawyers which vio

lates not only the provisions of Chapter 33 but also

Opinion No. 10 of the Committee of the Virginia State

Bar on Legal Ethics discussed on page 32 of this brief.

The Legal Defense Fund, while being a separate cor

poration, is in fact a part of the N A A C P. (See Fed. Tr.,

p. 321.) However, it is qualified as a Legal Aid Society in

New York and its charter provides that its purpose is to

help Negroes “ unable to employ and engage legal aid and

assistance on account of poverty.” The records show that

no investigation is made of the litigants assisted by the

“ Fund” . Furthermore, Thurgood Marshall conceded that

the current school segregation cases in Virginia could be

carried on at a cost of $2,500 or less (Fed. Tr., p. 315)

and that a person who “ had a $15,000 home free and clear,

he would be in pretty good shape” to finance his own

lawsuit (Fed. Tr., p. 315). Most of the litigants in the

current school cases examined in this case could qualify

as being able to finance their own lawsuits. (See Appen

dix IV of this B rief.) Thus, it cannot be argued that

41

Chapters 33 and 36 “ fetter access to the Federal courts”

as claimed by the plaintiffs.

The N A A C P concedes that it is not a legal aid society

(D efs.’ exh. D -4). Its activities and policies may be sum

marized as follows:

1) No aid is granted in lawsuits not handled by it

(D efs.’ exh. D -10);

2) It does not render aid to Negroes merely be

cause they may be indigent (Fed. Tr., p. 156 and

D efs.’ exh. D-4) ;

3) No investigation is made as to the financial

status of a prospective litigant (Fed. Tr., p. 156) ;

4) It will not render aid to Negroes merely seek

ing separate but equal facilities (D efs.’ exhs. D-5

and D - 9 ) ;

5) It will furnish aid only when its own lawyers

handle the case (D efs.’ exh. D -1 0 );

6) It directs and controls the litigation and thus

stands between the client and attorney (R . p. 113 and

D efs.’ exhs. D-7 and D-9) ; and

7) It solicits business (D efs.’ exhs. D-2 and D-8).

The activities of the plaintiffs outlined above are not

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of

free speech and the plaintiffs have cited no cases which

hold such activities are so protected.