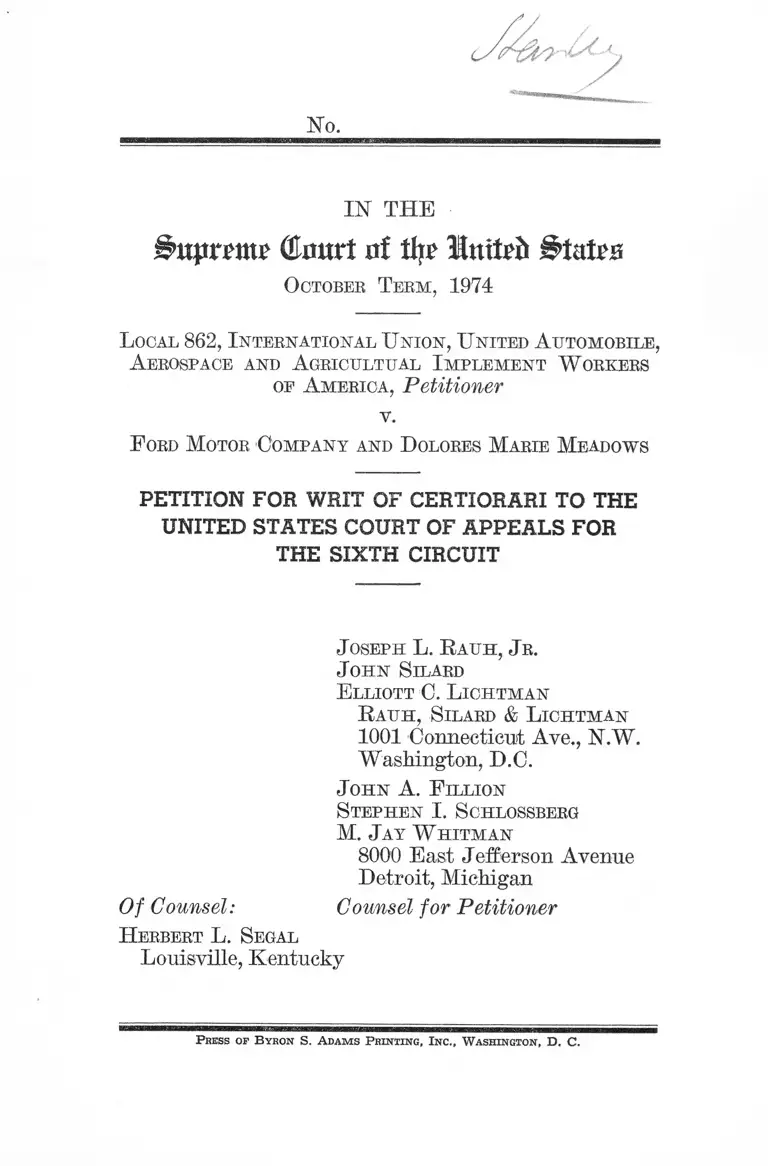

Local 862, International Union v. Ford Motor Company Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Local 862, International Union v. Ford Motor Company Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1974. 62e6465b-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1951927f-0567-49f8-b3be-f9ffbfbc5854/local-862-international-union-v-ford-motor-company-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

j$upr?mi> (Emtrt of % Inttefc B lato

O ctober T e r m , 1974

L ocal 862, I n te r n a t io n a l U n io n , U n ited A u to m o b ile ,

A erospace an d A g r ic u ltu a l I m p l e m e n t W orkers

of A m e r ic a , Petitioner

v.

F ord M otor C o m p a n y and D olores M arie M eadow s

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

J oseph L. R a tih , J r.

J o h n S ilard

E l lio tt C. L ic h t m a n

R atjh , S ilard & L ic h t m a n

1001 Connecticut Aye., N.W.

Washington, D.C.

J o h n A. P illio n

S t e p h e n I . S chlossberg

M. J a y W h it m a n

8000 East Jefferson Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

Of Counsel: Counsel for Petitioner

H erbert L . S egal

Louisville, Kentucky

Press of B yron S. A dams Printing, Inc., W ashington, D. C.

INDEX

Page

Opinions B elow ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................... 2

Question Presented ............. 2

Statement ........................ 2

Reason for Granting the Writ ...................................... 10

Conclusion ............................ 15

Appendix A—Decision of Court of Appeals, January

24, 1975 .................................................. la

Appendix B—Judgment of District Court, December

12, 1973 ......... 22a

Appendix C—Judgment of Court of Appeals, January

24, 1975 .................................................. 24a

Appendix D—Order of Court of Appeals Denying

Rehearing, March 24, 1975 ..................... 26a

Appendix E—New York Times, January 13, 1975 ----- 27a

TABLE OF CITATIONS

C ases :

Banks v. Chicago Grain Trimmers, 389 U.S. 9 1 3 ....... 10

Bigelow v. RKO, 327 U.S. 251 ...................................... 13

Brown v. Board of Education, 344 U.S. 1 ....... ............ 10

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312.............................. 11

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., — F.2d —, 10 FEP Cases

239,150 ................................. 0

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974), No. 74-728, U.S. Supreme Court. .3, 8,

10,12

Hunter v. Ohio, 396 U.S 879 ........................................... 10

Jurinko v. Edmon L. Wiegcmd Co., 477 F.2d 1038 (3d

Cir.), vacated, 414 U.S. 971 (1973), reinstated, —-

F.2d —, 7 FEP 787 .......................................... 5

11 Index Continued

Page

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S 717, 745 ............................ 12

Storey Parchment Co. v. Paterson Parchment Paper

Co., 282 U.S. 555 ...................................................... 12

Swann v. Charlotte-MecJclenhurg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 2 6 ............................................................ 12

M isc e lla n e o u s :

Cooper and Sobol, “ Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws,” 82 Harv. L.Rev. 1598, 1678-

1679 (1969) .............................................................. 9

Blumrosen, ‘ ‘ Seniority and Equal Employment Oppor

tunity” 23 Rutgers L.Rev. 268, 305, 307, 311-312

(1969) ....................................................................... 9

Prosser, Law of Torts, 4th ed., p. 3 3 ............................ 13

IN T H E

Bupnmt (tart of tip Irnt^

O ctober T e r m , 1974

No.

L ocal 862, I n te r n a t io n a l U n io n , U n ited A u to m o b ile ,

A erospace and A g ricu ltu al I m p l e m e n t W orkers

op A m e r ic a , Petitioner

v.

F ord M otor C o m p a n y and D olores M arie M eadow s

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Local 862, International Union, U A W (hereafter

Union), petitions for a writ o f certiorari to review the

judgment o f the United States Court o f Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion o f the Court o f Appeals (App. A, infra

p. la ) appears at 510 F.2d 939. The opinion of the

2

District Court appears at 62 E.R.D. 98. The judgment

o f the District Court appears in App. B, infra p. 22a.

JURISDICTION

The judgment o f the Court of Appeals (App. C,

infra p. 24a) was entered on January 24, 1975, and re

hearing was denied on March 24, 1975 (App. D, infra

p. 26a). The jurisdiction o f this Court is invoked under

28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether in remedying Title V I I violations by an

employer discriminatorily refusing to hire women, Dis

trict Courts may require the offending employer to hold

harmless from pay losses in work reduction situations

both the wronged discriminatees and the unoffending

incumbent workers, instead o f giving preferential sen

iority-layoff protection to either group o f employees.

STATEMENT

This is a ease of employment discrimination involving

a question as vital to the future o f Title V I I as any yet

presented to this Court since the statute’s enactment a

decade ago. Like many recent oases under Title V II ,

this case below presented a variety o f questions con

cerning the scope of the class action, the prerequisites

for individual back pay recoveries, the appropriate

statute o f limitations, etc. But after the EEOC filed

an amicus brief in the Court of Appeals highlighting

the question o f retroactive seniority for diserminatees,

the opinion o f the Court reached the crucial issue:

whether in ordering the hiring of a group o f diserim-

inatees courts should require that they be granted

retroactive seniority which may cause the layoff in

3

work reduction periods of incumbent employees wbo

have long been earning their seniority protection.

Faced with that same question the Fifth Circuit in

Franks, which is here on grant o f certiorari (No. 74-

728), has ruled against retroactive or constructive sen

iority for the discriminatees. The Sixth Circuit in the

present case expressly rejects the Fifth Circuit result,

but remands the issue for District Court consideration

o f “ policy questions” without guidance in their resolu

tion. W e urge grant o f certiorari so the Court may

consider a remedial alternative overlooked by the Fifth

and the Sixth Circuit rulings, an alternative which

avoids future layoff losses both for the discriminatees

who should long ago have been hired with seniority pro

tection and for the incumbent employees who have

meanwhile been earning their seniority rights on the

job. A brief review of the facts will set the case in

proper perspective:

1. In October o f 1969 the Ford Motor Company

opened the Ford Truck Plant, a new production facility

in Jefferson County, Kentucky. Among nearly one

thousand initial employees hired for production jobs

there were no women. Plaintiff Meadows was one of

the women denied hiring soon after the plant opened.

Having filed a complaint with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission and having exhausted its pro

cedures, Ms. Meadows in 1971 filed this class action

against the Company and against U A W Local 862, the

collective bargaining representative of the employees.

The Complaint asserted that by a rule against hiring

applicants weighing less than 150 pounds the Company

was practicing sex discrimination. As late as 1973 there

were still hardly any women on the work force, al

though there had been some 1,414 women among the

4

30,000 persons who had requested employment since

the plant opened in 1969.1

2. On January 16, 1973, the District Court found in

its ruling on plaintiff’s summary judgment motion

that the Company’s weight rule excluded from hiring

about 70% of women applicants but only 20% of the

men, and that actually hiring exceptions had been

made for some men who did not weigh 150 pounds.

Finding that the weight limit operates in a sex-dis

criminatory fashion and that no business justification

for the requirement was shown by the Company, the

District Court granted summary judgment for the

plaintiff enjoining the continued application o f the

weight standard. However, the Court’s final judg

ment ( infra, p 22a) provided no relief other than

preferential hiring for the 31 rejected women appli

cants who had responded to a public notification or

dered by the Court. The District Court denied them

back pay on the ground that it could not determine

with certainty that any particular woman applicant

would have been hired but for the Company’s sex-

discriminatory rule. The Court also declined to pro

vide them retroactive seniority, notwithstanding plain

t iff ’s plea (Complaint, p. 5) for the “ adjusted senior

ity ” to which she and other discriminatees “ would

have been entitled” but for the wrongful denial of 1

1 Although the Complaint had alleged that UAW Local 862,

petitioner herein, acquiesced in the Company’s sex discrimination

practice, the claim was not pursued with any evidentiary support.

Accordingly, the District Court found that the Union had played

no part in the hiring practice, and its final judgment (infra, p.

22a) dismissed with prejudice as to the Union. Nevertheless, that

judgment was appealed without qualification and the Union was

given the status of a party in the ensuing Court of Appeals

proceedings (see infra, p. 10, n. 3).

5

their hiring applications. Some o f the 31 discrim-

inatees have been hired pursuant to the District Court’s

judgment, but are currently vulnerable to layoff be

cause their seniority does not date from their hiring

rejections.

3. In the Court o f Appeals the initial briefs o f the

parties focused chiefly on the back pay issue and on

limits which the District Court had placed upon the

class whose members would benefit from its decree.

While plaintiff asserted (Br. for Plaintiff-Appellant,

p. 7) that the District Court had “ refused to consider

seniority adjustment for hired class members” , she

went no further than to point out that since “ the men

hired in 1969 or 1970 are no longer in entry level jobs” ,

she and other beneficiaries of the decree would be “ re

quired to start and remain at a competitive disadvan

tage with those male applicants who were unlawfully

preferred by Ford in the period from 1969-1973” {id.,

p. 19).

A fter the initial briefs were filed, the EEOC entered

the case in the Court of Appeals with an amicus brief.

Therein, the agency supported various claims made

by the plaintiff and gave special emphasis to the se

niority issue (Br. pp. 8-9). It asserted that by denying

the seniority which plaintiff and her class “ would have

accrued” but for the Company’s conduct, the District

Court “ failed to provide the full relief for victims of

discrimination which Congress intended.” Noting

that seniority is “ crucial” in determining whether a

discriminatee will remain employed in any layoff situa

tion, the EEOC urged (id., pp. 10-11) that consistent

with the Third Circuit’s ruling in Jurinko (477 F.2d

1038) any discriminatee is entitled to be hired with a

constructive or retroactive seniority date as of the time

o f her original rejection for employment. The

6

EEOC emphasized (id., p. 12) that otherwise the dis-

cmninatees “ will continuously suffer from less job

security and poorer upward mobility than those men

who filed applications at the same time and were hired,

merely because they were prevented from commencing

employment and accumulating seniority by F ord ’s

discriminatory weight requirements. ’ ’ However, hav

ing so stated, the E EO C’s brief then added a comment

(p. 12, n. 9) concerning the difficult problem o f the

impact of a retroactive seniority grant on the existing

work force:

Nor will granting such seniority work injustice

towards other employees previously hired. Such

seniority merely allows the women an opportunity

to compete for future job vacancies on the basis

of their ability to perform and their adjusted se

niority; it would not permit “ bumping” of male

incumbents from positions they presently occupy.

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., supra, 485 F.2d

at 450; United States v. Hayes International

Corp., supra, 456 F.2d at 116; Local 189, United

Papermahers and Paperworkers v. United States,

supra, 416 F.2d at 988. Furthermore, the fact

that some employees’ expectations would be frus

trated by the awarding o f seniority adjustments

does not stand in the way o f such relief. “ . . .

Title Y I I guarantees that all employees are en

titled to the same expectations regardless of ‘ race

color, religion, sex, or national origin.’ Where

some employees now have lower expectations than

their co-workers because o f the influence o f one of

these forbidden factors, they are entitled to have

their expectations raised even i f the expectations

o f others must be lowered in order to achieve the

statutorily mandated equality o f opportunity.”

Robinson v. Lorrillard Corp., supra, 444 F.2d

at 800 .

In this posture the seniority issue reached the Court

below for disposition.

7

4. The opinion by Judge Edwards for the Court of

Appeals makes a lengthy analysis o f the hack pay issue

and concludes that the District Court erred in refusing

a back pay award. The Court then addresses the se

niority problem but is apparently unable to resolve it.

On the one hand, the Court remands for reconsideration

the District Court’s denial o f retroactive seniority and

goes so far as to disapprove the Eifth Circuit decisions

•—including Franks—which have that result. On the

other hand, the Court emphasizes that “ the burden of

retroactive seniority for determination o f layoffs would

fall directly upon other workers who have themselves

had no hand in the wrongdoing found by the District

Court. ’ ’ In sum, the Court returns the seniority ques

tion to the District Court for its consideration of “ the

policy questions involved,” offering its own meager

guidance in the following terms (infra, pp. 19a-21a) :

Whatever the difficulties o f determining back

pay awards, the award o f retroactive job seniority

offers still greater problems. Seniority is a sys

tem of job security calling for reduction o f work

forces in periods of low production by layoff first

o f those employees with the most recent dates of

hire. It is justified among workers by the concept

that the older workers in point of service have

earned their retention o f jobs by the length of

prior services for the particular employer. From

the employer’s point o f view, it is justified by the

fact that it means retention o f the most experi

enced and presumably most skilled of the work

force. Obviously, the grant of fully retroactive

seniority would collide with both of these prin

ciples.

In addition, where the burden o f retroactive pay

falls upon the party which violated the law, the

burden of retroactive seniority for determination

8

of layoff would fall directly upon other workers

who have themselves had no hand in the wrong

doing found by the District Court.

There is, however, no prohibition to be found in

the statute we construe in this case which prohib

its retroactive seniority and, of course, the remedy

for the wrong o f discriminatory refusal to hire

lies in the first instance with the District Judge.

Dor his guidance on this issue we observe, how

ever, that a grant of retroactive seniority would

not depend solely upon the existence o f a record

sufficient to justify back pay under the standards

o f the Back Pay Section o f this opinion. The

court would, in dealing with job seniority, need

also to consider the interests of the workers who

might be displaced as well as the interests of the

employer in retaining an experienced work force.

W e do not assume, as our brethren in the Fifth

Circuit appear to (Local 189, AFL-C IO , GLC v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980, cert, denied, 397 TJ.S.

919 (1970)), that such reconciliation is impossible,

but as is obvious, we certainly do foresee genuine

difficulties. See also Jurinko v. Edmon L. W ie-

gand Co., 477 F.2d 1038 (3d Cir.), vacated, 414

TJ.S. 971 (1973), reinstated, — F.2d — , 7 F E P

787 (3d Cir. 1974). Cf. Local 189, supra; Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398 (5th

Cir. 1974).

On remand the District Judge may desire to

hear the policy questions involved in this problem

before remanding the individual claims to the

Master. For purposes of that hearing notice

should be given to the employees likely to be a f

fected and intervention should be allowed from

appropriate representatives.

W hat we have said concerning job seniority does

not, of course, apply to the fringe benefits of em

ployment. Where vacation schedules or pension

9

rights (or other fringe benefits) are determined

by date of hire, we perceive no reason why that

date in these cases should be other than the date

which the trial court fixes as the date when the

employee would have been hired, absent the illegal

hiring practice which the District Court has iden

tified and enjoined.

5. Unlike the Fifth Circuit’s ruling in Franks, which

is pending on certiorari before this Court, the ruling

by the Sixth Circuit in the present case declines to con

clude that “ reconciliation is impossible” between the

seniority-layoff protection of the incumbent workers

and those o f a class o f discriminatees ordered to be

hired by a District Court decree under Title V II . But

the Court returns the issue to the District Court,

essentially without guidance or assistance in the eon-

cededly difficult task. While rejecting the Scylla-

Charybdis assumption espoused by the Franks ruling

in its preference for the incumbent employees, the

Sixth Circuit provides no workable alternative. And in

a more recent ruling the same Court again avoids the

issue, declining on procedural grounds to grant retro

active seniority to discriminatees. EEOC v. Detroit

Edison Co., — F.2d — , 10 FED Cases 239, 250.

However, there is an alternative, originally sug

gested by scholarly analyses o f Title V II , which does

not threaten the layoff either of incumbent workers or

newly hired discriminatees.2 That is the “ front pay”

remedy which requires the wrongdoing employer to

hold both groups harmless from layoff losses in work

2 See Cooper and Sobol, “ Seniority and Testing Under Fair Em

ployment Laws,” 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1678-1679 (1969) ; Blum-

rosen, “ Seniority and Equal Employment Opportunity” , 23

Rutgers L. Rev. 268, 305-307, 311-312 (1969).

10

reduction situations. W e proceed to urge the grant of

concurrent review with Franks, for consideration of

a viable alternative to the seniority-layoff impasse

which that Court resolved against the discriminatees

and the Court below was unable to resolve.

REASON FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Concurrent Review Should Be Granted with Franks (No. 74-

728) for Consideration of a Viable Alternative to the Se

niority-Layoff Impasse Which the Fifth Circuit Resolved

Against the Discriminatees and the Court Below Was

Unable To Resolve

Following grant o f certiorari on a question o f public

importance this Court has frequently granted concur

rent review in companion cases presenlting related and

illuminating aspects o f the same question. See, e.g.,

Brown v. Board of Education, 344 U.S. 1 (1952). W e

urge that course here because the limited contentions in

Franks may foreclose approval o f the best remedy

available in that case as well a;s this. Concurrent con

sideration with Franks will help to illuminate a major

remedial option which neither circuit court seems to

have recognized: a remedy which requires the wrong

doing employer to protect from layoff losses both

those against vbiom he discriminated and his incumbent

employees, rather than subjecting either group to wage

losses in work reduction situations.3

8 In this case the brief amicus by the EEOC emphasized the

seniority rights issue and the Court of Appeals reached that issue

in its opinion. Since the issue directly affects the rights of the in

cumbent workers who are members of the IJAW and are repre

sented by it in collective bargaining, the Union is here a proper

party to invoke review. In like circumstances this Court has

granted intervention to affeeted third parties not previously in

the case, so as to permit their filing of certiorari petitions. See

Banks v. Chicago Grain Trimmers, 389 U.S. 913; Hunter v. Ohio,

396 U.S. 879. In the present case no leave for intervention is

11

This Court’s timely consideration o f that remedy is

vitally necessary. The Court doubtless perceived last

term during its consideration of DeFunis (416 U.S.

312) the undesirable character o f remedies for past dis

crimination which throw the burden either upon the

wronged minority or upon other blameless citizens. I f

in the employment area there is a better solution,

surely it should be preferred over one which is unjust

either to the discriminatee or the incumbent worker.

Thus, i f the discriminatees are hired without the same

protection against losses in work reduction situations

which they would have had but for their employment

rejection, the key Congressional purpose to provide full

Title Y I I remediation is frustrated. As the Conference

Committee emphasized (see 118 Cong. Rec. 7168) sec

tion 706(g) is intended to assure “ that persons

aggrieved by the consequences and effects o f the unlaw

ful employment practice be, so far as possible, restored

to a position where they would have been were it not

for the unlawful discrimination.” A recent article

which describes layoff o f women who were hired at

needed to permit the filing of this petition because the Union is

already a party in the case. Although the District Court dis

missed the Union, it was thereafter captioned as a defendant-

appellee in all briefs in the Court of Appeals as well as in the

opinion of that Court; it was given notice of all proceedings; it

requested leave to appear by letter of May 20, 1974 from counsel

Segal to James A. Higgins, Clerk, and participated in the oral

arguments; and it filed a petition for rehearing which was en

tertained by the Court of Appeals. Finally, that Court expressly

recognized (p. 19) that “ employees likely to be affected” by the

disposition of the seniority problem have a right to participate

by “ appropriate representatives.” Since the Union is such a

representative and a recognized party in the Court below, it prop

erly presents this petition addressed to that Court’s treatment of

the vital senioriy issue.

12

General Motors because o f alleged past sex discrimina

tion, dramatically shows how illusory may be a

“ remedy” which provides no layoff protection to dis

criminatees. See App. E, infra p. 27a. Given this

Court’s definitive ruling in Swann (402 TJ.S. 1, 26)

that to remedy school segregation there must be de

segregation in actuality rather than mere theory, we

cannot believe that in the employment area this Court

would affirm the ruling in Franks which may leave the

discriminatee without job or pay.

On the other hand it would also be unjust if, after

years spent in earning seniority on the job, the faultless

incumbent employees were subjected to layoff in favor

o f discriminatees hired with seniority retroactive to

the time when they were denied hiring. Only last year

a majority o f this Court declined to put the desegrega

tion burden upon suburban school districts “ not shown

to have committed any constitutional violation. ’ ’ Milli-

ken v. Bradley, 418 IT.S. 717, 745. Considering that

the incumbent employees are in no way at fault for the

employer’s Title V I I violation, a remedy which corrects

the employer’s wrongdoing at the expense o f 'those

employees is unjust and unwise.

Accordingly, we will urge for the Court’s considera

tion a third and better option, which requires that fol

lowing reinstatement o f discriminatees the offending

employer hold harmless against layoff losses both the

discriminatees and his incumbent employees hired

after the discriminatees’ original rejection from em

ployment. That remedy properly puts the full burden

upon the wrongdoer rather than his victims or other

unoffending employees. It is a familiar rule o f lawT

that the full remedial burden shall be on the offending

party. Such seminal decisions as Storey Parchment

13

(282 U.S. 555) and Bigelow (327 TT.S. 251) apply the

rule as between the wrongdoer and his victim. The

rule equally applies as between the wrongdoer and

third parties; where the wrongdoer has done intentional

harm he is liable to third parties as much as to the

immediately injured party, because “ having departed

from the social standard o f conduct, he is liable for the

harm which follows from his act” (Prosser, Law of

Torts, 4th ecL, p. 33). Thus there is every reason o f

equity and justice for placing the full burden upon the

employer who violated Title V II , requiring him to pro

tect both the discriminatees and his incumbent work

force against layoff losses in periods of work reduc

tion. The save harmless remedy would operate, of

course, only in the area o f overlapping seniority be

tween discriminatees and incumbents with less sen

iority; when an entire plant shuts down or layoff

reaches up the seniority ranks beyond the date when

the discriminatees were wrongfully rejected for hiring,

the normal rules would apply and no member o f either

group could claim protection against layoff.4

No more than avoiding the increased cost o f “ back

pay” to discriminatees, should employers who violate

Title V I I avoid the cost of “ front pay” in layoff sit

uations. Indeed, the latter may be the lesser burden,

since employers have a variety of available means to

cushion future wage obligations which they do not have

in meeting accrued back pay required by a Title V I I

4 I f it is suggested that the employer’s save harmless duty

guarantees pay to both groups but not necessarily the work itself,

we would respond with the common observation that employers

find work for employees whom they must pay. However, if re

duction in the work force may actually sometimes become necessary

then many employees may themselves opt for layoff with pay, and

for any others equitable arrangements can be made.

14

decree. Faeed with restrictions on layoff actions, em

ployers can reduce new hiring, encourage retirement, or

otherwise hedge against employee idle time by adjust

ments made through the established collective bar

gaining process. In cases where employers are re

quired to “ red circle” some of their employees they

have developed a variety o f means for meeting the extra

costs, sometimes even by ultimate resort to price in

creases. W hile we would not welcome that recourse, it

still seems a preferable result that society at large

finance the correction o f massive and historical social

wrongs rather than innocent individual workers and

families least able to absorb the costs o f social reform.

In sum, the seniority impasse in Title Y I I cases is

neither as inexorable as the F ifth Circuit holds in

Franks nor as difficult as the Sixth Circuit suggests in

its present ruling. Grant o f review will permit us to

demonstrate that the seniority rights o f all can be safely

preserved by measures of judicial relief which place

the full economic burden on the wrongdoing employer

whose actions created the remedial issue. Surely on

a matter of such import this Court will want to con

sider a remedy which does not make one group of work

ers bear the burden for securing the rights o f other

equally blameless employees.

15

CONCLUSION

For the reason stated the writ should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J oseph L. Ratth, Jr.

J o h n S ilard

E llio tt 0 . L ic h t m a n

R atth, S ilard & L ic h t m a n

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C.

J o h n A. F illio n

S t e p h e n I. S chlossberg

M . J a y W h it m a n

8000 East Jefferson Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

Counsel for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

H erbert L . S egal

Louisville, Kentucky

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX A

Nos. 74-1258-59

UNITED STATES COURT OE APPEALS

EOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

D olores Marie Meadows,

Plaintiff-A ppellant,C ro ss-Appelle e,

v .

F ord Motor Company,

Defendant-Appellee, Gross-Appellant,

L ocal 862, I nternational Union, United A utomobile,

A erospace and A gricultural I mplement W orkers op

A merica; and I nternational Union, U nited A uto

mobile, A erospace and A gricultural Implement

W orkers op A merica, Defendants-Appellees.

A p p e a l from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Kentucky, Louisville Division

Decided and Filed January 24,1975

Before: E dw ards and M il l e r , Circuit Judges, and Mc

A ll is t e r , Senior Circuit Judge.

E d w ard s , Circuit Judge. Plaintiff appeals from tlie de

nial of back pay and retroactive seniority after the District

Court for the Western District of Kentucky had found that

she and the class of women job applicants she represents

had been denied jobs, in violation of the prohibition against

sex discrimination in employment contained in Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.8.C. §§ 2000e to 2000e-15

(1970), as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e to 2000e-17 (Supp.

II, 1972). She also claims that the class involved was un

duly restricted by the District Judge and that he ordered

an inadequate amount of attorney fees.

This controversy arose when defendant Ford Motor Com

pany began hiring employees for a new Ford Truck Plant

2a

in Jefferson County, near Louisville, Kentucky. Plaintiff

Meadows applied for a production line job on October 10,

1969. She was not hired and heard nothing concerning her

application but learned that Ford had hired over 900 .men

and no women. She then filed a charge of discrimination

before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on

January 14, 1970, alleging that the Ford Motor Company

and Local 862, UAW;1 were discriminating against her and

other women similarly situated. The EEOC issued her a

notice of right to sue and plaintiff Meadows filed this action

in the District Court alleging that Ford employed a 150 lb.

limitation on production line hires so as to eliminate women.

The case was heard by discovery and the taking of depo

sitions. The District Judge entered findings of fact and

conclusions of law on August 29, 1973, and followed by a

final judgment which recorded his critical holdings as fol

lows :

2. There are thirty-one (31) members of the Class

represented by the Plaintiff in the instant action; the

names, address and telephone numbers of the said

members of the class are attached hereto and made a

part hereof as if fully copied herein.

3. The use by the Defendant under the circumstances

before the Court of the 150 pound weight requirement

for eligibility for employment on its production line at

its Kentucky Truck Plant constitutes an unlawful em

ployment practice pursuant to the terms of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l et seq. (sic).

4. Neither the Plaintiff nor any member of the class

is entitled to any award of damages. Plaintiff is

awarded its costs herein expended and counsel fees in

the sum of $11,500.00.

1 Local 862, International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace

and Agricultural Implement Workers of America.

3a

5. The Defendant, Ford Motor Company, be and

hereby is permanently enjoined and prohibited from

applying the 150 pound weight requirement for eligi

bility for employment on its production line at its

Kentucky Truck Plant.

6. The names of the Plaintiff and the thirty-one (31)

members of the class represented by the Plaintiff shall

be placed by the Defendant in a priority employment

pool in the order of the dates of their original appli

cation for production employment. The names of all

other applicants for production employment are to be

placed in a general pool in accordance with the present

practice of Defendant. As production employment

positions become available, Defendant shall select

names from the two pools of applicants at a. set ratio

of one name from the priority pool for every three

names from the general pool, and these individuals are

to be notified by the Defendant of the job openings as

they occur and given a reasonable opportunity to ap

pear for a pre-employment physical examination and

the other processes regularly required of such appli

cants.

The District Judge defined the class of plaintiffs as those

women who had applied for jobs at the Kentucky Truck

Plant between April 1, 1971, and April 13, 1972, and who

were refused jobs.

The District Judge also retained jurisdiction of the case

to supervise implementation of his judgment.

The record showed that the two union defendants exer

cised no control over Ford hiring practices and the case as

tio them was dismissed by the District Court. No appeal

was taken from this decision.

The Ford Motor Company waived its appeal from the

portion of the District Judge’s judgment finding it guilty

of discriminatory practices and requiring it to terminate

4a

them and to establish a priority system for offering em

ployment to some 31 identified discriminatees.

On this appeal we deal only with plaintiffs’ complaints

1) that the District Judge’s judgment by refusing back pay

and retroactive seniority failed to make them whole and

failed to deter similar discrimination in the future, 2) that

the District Judge defined the class of discriminatees too

narrowly, and 3) that the attorney fees awarded did not

consider all of the work performed in this litigation.

Back P ay

The District Judge’s reasoning on the back pay issue is

set forth in an opinion as follows:

However, having determined that liability for dis

crimination exists is not the same as finding that an

award of money damages is in order. Indeed, the

Court has found absolutely no authority for awarding

money damages in a case like the present one. Under

the relevant statutê , 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(5), (sic) the

only money damages that can be awarded are in the

form of back pay. No court whose decision has been

reported has been willing to award back pay to a group

of persons who were never in the employ of the em

ployer-defendant in the first place. Back pay has been

awarded in cases of discriminatory refusal to promote

or to transfer, and to some individuals who were dis

criminate rily denied jobs in the first instance, but in

all of these situations, the amount of speculation as to

just who was damaged and how much has been mini

mal. For instance, in the case of Bowe v. Colgate, 416

F. 2d 711 (C.A. 7, 1969), it was quite clear as to which

persons were damaged and how they should be com

pensated. That is not the case here. Assuming that

the class of plaintiffs can be more or less exactly de

fined, there is no way to calculate which of them would

have been hired, or when, or what other circumstances

5a

would have intervened in the meantime1. In other

words, there is no basis on which an award in any

amount can be justified. Although all reductions of

legal injury to money damages are somewhat specu

lative, in other cases, the damaged party is absolutely

identified, which is not the case here. The fact that

Ford has been found guilty of sexual discrimination

does not mean that it must pay whatever damages to

which the Plaintiff believes that she is entitled. Un

less the Court is directed to some authority to the

contrary, it does not intend to make an award of money

damages in this case.

The District Judge also entered the following conclusion

of law:

6. The Court, being unable to determine from the

records when plaintiff or any members of her class

would have been employed, had it not been for the dis

criminatory practices of the defendant, concludes that

it is without authority to award any backpay or any

monetary damages to plaintiff or any members o f her

class. The only cases in which backpay has been

awarded to a potential employee, who was discrimi

nated against and not employed, are those involving

individual employees where it was definitely shown

that they would have been entitled, on a date certain,

to be employed and after computation could be made

of the wages to which they were entitled. See Dates

v. Georgia Pacific Corporation, 326 F. Supp. 397 (D.C.

Ore. 1970). Any award of damages in this case, there

fore, would be speculative and must be denied.

We believe the District Judge was in error in concluding

that the difficulties of ascertaining the amount of damages

suffered deprived him of authority to award back pay.

The statute relating to back pay is 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)

6a

(1970). The statutory language extant at the time this suit

was filed was:

(g) If the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an

unlawful employment practice charged in the complaint,

the court may enjoin the respondent from engaging in

such unlawful employment practice, and order such

affirmative action as may be appropriate, which may

include reinstatement or hiring of employees, with or

without back pay (payable by the employer, employ

ment agency, or labor organization, as the case may be,

responsible for the unlawful employment practice).

Interim earnings or amounts earnable with reasonable

diligence by the person or persons discriminated

against shall operate to reduce the back pay otherwise

allowable. No order of the court shall require the ad

mission or reinstatement of an individual as a member

of a union or the hiring, reinstatement, or promotion

of an individual as an employee, or the payment to him

of any back pay, if such individual was refused admis

sion, suspended, or expelled or was refused employ

ment or advancement or was suspended or discharged

for any reason other than discrimination on account

of race, color, religion, sex or national origin or in vio

lation of section 704(a). 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (1970).

The statute was reenacted in 1972, effective for all charges

then pending with the EEOC, so as to add a statute of limi

tations providing that, “ Back pay liability shall not accrue

from a date more than two years prior to the filing of a

charge with the Commission.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)

(Supp. II, 1972), amending, 42 U.S.C. § 2Q00e-5(g) (1970).

The legislative history of this provision is also illumi

nating :

Section 706(g)—This subsection is similar to the

present section 706(g) of the Act. It authorizes the

7a

court, upon a finding that the respondent has engaged

in or is engaging in an unlawful employment practice,

to enjoin the respondent from such unlawful conduct

and order such affirmative relief as may be appropri

ate including, but not limited to, reinstatement or hir

ing, with or without back pay, as will effectuate the

policies of the Act. Back pay is limited to that which

accrues from a date not more than two years prior to

the filing of a charge with the Commission. Interim

earnings or amounts earnable with reasonable dili

gence by the aggrieved person(s) would operate to

reduce the backpay otherwise allowable.

The provisions of this subsection are intended to give

the courts wide discretion exercising their equitable

powers to fashion the most complete relief possible.

In dealing with the present section 706(g) the courts

have stressed that the scope of relief under that sec

tion of the Act is intended to make the victims of un

lawful discrimination whole, and that the attainment

of this objective rests not only upon the elimination

of the particular unlawful employment practice com

plained of, but also requires that persons aggrieved by

the consequences and effects of the unlawful employ

ment practice be, so far as possible, restored to a posi

tion where they would have been were it not for the un

lawful discrimination. 118 Cong. Bee. 7168 (1972)

(Conference Beport) (Emphasis added.)

We approach decision of this issue, keeping in mind the

classic treatment of the damage issue by the United States

Supreme Court in the Story Parchment Go. case:

Where the tort itself is of such a nature as to preclude

the ascertainment of the amount of damages with cer

tainty, it would be a perversion of fundamental prin

ciples of justice to deny all relief to the injured person,

and thereby relieve the wrongdoer from making any

amend for his acts. In such case, while the damages may

8a

not be determined by mere speculation or guess, it will

be enough if the evidence show the extent of the dam

ages as a matter of just and reasonable inference, al

though the result be only approximate. The wrongdoer

is not entitled to complain that they cannot be measured

with the exactness and precision that would be possible

if the case, which he alone is responsible for making,

were otherwise. Eastman Kodak Co. v. Southern Photo

Co., 273 U.S. 359, 379. Compare The Seven Brothers, 170

Fed. 126, 123; Pacific Whaling Co. v. Packers’ Assn.,

138 Cal. 632, 638. As the Supreme Court of Michigan

[Gilbert v. Kennedy, 22 Mich. 117, 130 (1871)] has

forcefully declared, the risk of the uncertainty should

be thrown upon the wrongdoer instead of upon the in

jured party.

# # #

‘ ‘ To deny the injured party the right to recover any

actual damages in such cases, because they are of a na

ture which cannot be thus certainly measured, would be

to enable parties to profit by, and speculate upon, their

own wrongs, encourage violence and invite depredation.

Such is not, and cannot be the law, though cases may be

found where courts have laid down artificial and arbi

trary rules which have produced such a result.” Story

Parchment Co. v. Paterson Parchment Paper Co., 282

U.S. 555, 563-64 (1931).

We recognize, of course, that the words were spoken in

the context of tort cases. But in tort and in discrimination

cases the basic objective of damages is the same—to make

the injured party whole to the extent that that can be done.

We also recognize that to some extent we write on a clean

slate. No case exactly in point has been cited to us and we

have found none. Most of the case law in which back pay

awards have been granted because of unlawful discrimina

tion in employment practices have involved either illegal dis

crimination (via discharge or failure to promote) against

9a

employees who were union members or adherentsla or

against employees who were Negroes.2

Here, of course, we deal with a record showing discrimi

nation against women in hiring practices. Congress, how

ever, appears to have modeled the remedial features of Title

VII upon the National Labor Relations Act. See 110 Cong.

Rec. 6549 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey). See gen

erally Davidson, “ Bach Pay” Awards Under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 26 R ut. L. R ev. 741 (1973) ;

Note, Equal Employment Opportunity: The Bach Pay Rem

edy Under Title VII 1974 U. III. L. F or. 379 (1974). In

addition, the prohibition against sex discrimination is con

tained in the same sentence of Title VII as the prohibition

against race discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (1970),

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (Supp. II, 1972). We be

lieve, therefore, that the great amount of case law man

dating back pay awards in these two situations which we

have just cited is strong precedent for our instant case.

In this regard we find the leading Supreme Court case on

back pay awards occasioned by illegal union discrimination

in hiring practices to be instructive:

Second. Since the refusal to hire Curtis and Daugh

erty solely because of their affiliation with the Union

was an unfair labor practice under § 8(3), the remedial

authority of the Board under § 10(c) became operative.

111 See, e.g., NLBB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1

(1937); NLBB v. Seven-Up Bottling Co., 344 U.S. 344 (1953);

Radio Officers v. NLBB, 347 U.S. 17 (1953); Phelps Bodge Corp.

v. NLBB, 313 U.S. 177 (1941).

2 See, e.g.. Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973); Thorton v. East Texas Motor Freight, 497 F.2d

416 (6th Cir. 1974) ; Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491

F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ; Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474

F.2d 134 (4th Cir. 1973), cert, granted, 43 U.S.L.W. 3344 (U.S.

Dec. 16, 1974) (No. 74-389); United States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d Cir. 1971).

10a

Of course it could issue, as it did, an order “ to cease

and desist from such unfair labor practice ’ ’ in the fu

ture. Did Congress also empower the Board to order

the employer to undo the wrong by offering the men dis

criminated against the opportunity for employment

which should not have been denied them f

Reinstatement is the conventional correction for dis

criminatory discharges. Experience having demon

strated that discrimination in hiring is twin to dis

crimination in firing, it would indeed be surprising if

Congress gave a remedy for the one which it denied for

the other. The powers of the Board as well as the re

strictions upon it must be drawn from § 10(c), which

directs the Board “ to take affirmative action, including

reinstatement of employees with or without back pay,

as will effectuate the policies of this Act.” It could not

he seriously denied that to require discrimination in

hiring or firing to be “ neutralized,” Labor Board v.

Mackay Co., 304 U.S. 333, 348, by requiring the dis

crimination to cease not abstractly but in the concrete

victimizing instances, is an “ affirmative action” which

“ will effectuate the policies of this Act. ’ ’ Therefore, if

§ 10(c) had empowered the Board to “ take such affirm

ative action as will effectuate the policies of this Act,”

the right to restore to a man employment which was

wrongfully denied him could hardly he doubted. Even

without such a mandate from Congress this Court com

pelled reinstatement to enforce the legislative policy

against discrimination represented by the Railway

Labor Act. Texas $ N. 0. B. Co. v. Railway Clerks,

281 U.S. 548. Attainment of a great national policy

through expert administration in collaboration with

limited judicial review must not be confined within

narrow canons for equitable relief deemed suitable by

chancellors in ordinary private controversies. Com

pare Virginian By. v. Federation, 300 U.S. 515, 552.

To differentiate between discrimination in denying em

11a

ployment and in terminating it, would be a differentia

tion not only without substance but in defiance of that

against which the prohibition of discrimination is

directed.

But, we are told, this is precisely the differentiation

Congress has made. It has done so, the argument runs,

by not directing the Board ‘ ‘ to take such affirmative ac

tion as will effectuate the policies of this Act, ’ ’ sim-

pliciter, but, instead, by empowering the Board “ to

take such affirmative action, including reinstatement of

employees with or without back pay, as will effectuate

the policies of this Act.” To attribute such a function

to the participial phrase introduced by “ including” is

to shrivel a versatile principle to an illustrative appli

cation. We find no justification whatever for attributing

to Congress such a casuistic withdrawal of the author

ity which, but for the illustration, it clearly has given

the Board. The word “ including” does not lend itself

to such destructive significance. Helvering v. Morgan’s,

Inc., 293 U.S. 121, 125, note. Phelps Dodge Corp. v.

NLRB, 313 U.S. 177, 187-89 (1941).

The leading case in this circuit upon the award of back

pay was written by Judge Miller in the context of a race

discrimination case involving promotional opportunities:

The finding of discrimination by the district court, in

addition to the nature of the relief (compensatory as

opposed to punitive), and the clear intent of Congress

that the grant of authority under Title YII should be

broadly read and applied mandate an award of back

pay unless exceptional circumstances are present.

Congress evidently intended that the award of back

pay should rest within the sound discretion of the trial

judge. Although appellate courts are loathe to interfere

with the exercise of such discretion by a trial court, it is

recognized that it is not free from appellate scrutiny. In

12a

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134, 141 (4th

Cir. 1973), [cert, granted, 43 U.S.L.W. 3344 (U.S. Dec.

16, 1974) (No. 74-389)] the Fourth Circuit said:

Discretion in a legal sense necessarily is the re

sponsible exercise of official conscience on all the

facts of a particular situation in the light of the pur

pose for ivhich the power exists. Bowles v. Goebel,

151 F.2d 671, 674 (8th Cir. 1945) (emphasis added).

Thus in determining the proper scope of the exercise

of discretion, the objective sought to be accomplished

by the statute must be given great weight. Hecht Co.

v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 331, 64 S.Ct. 587, 88 L.Ed. 754

(1944). Where a district court fails to exercise dis

cretion with an eye to the purposess of the Act, it

must be reversed. Wirtz v. B. B. Saxon Co., 365 F.2d

457 (5th Cir. 1966); Shultz v. Parke, 413 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1969).

We find no reasonable basis for denial of such relief on

the present record. The 1968 change in Timken’s sen

iority system does not ameliorate the injury already

suffered. Good faith by Timken either during the 1965-

68 period or thereafter is not a valid defense to a claim

for back pay. The Court in Rowe v. General Motors

Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972), went to great

lengths to emphasize the good faith of the defendant.

Nevertheless, the court remanded the case, stating that

the district court on reconsideration “ will of course,

include the appropriate remedy, back pay, limited or

full, etc., as needed to effectuate the Act. ’ ’ Id. at 360.

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870,

876-77 (6th Cir. 1973). (Footnote omitted.)

See also Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight, 497 F.2d

416 (6th Cir. 1974).

13a

Other circuits have reached similar results. Thus in the

Georgia Power case the Fifth Circuit said:

2. Equitable Discretion

Title VII was enacted with the legislative objective

of disestablishing the racial and sexual caste systems

which had remained ingrained in the American econ

omy since slavery and coverture. The Act, in authoriz

ing courts to grant equitable relief to those who might

be injured by its breach, expressly and impliedly in

cludes the discretion to award back pay. Given this

court’s holding that “ [a]n inextricable part of the res

toration to prior [or lawful] status in the payment of

back wages properly owing to the plaintiffs” , Harkless

v. Sweeny Independent School District, 427 F.2d 319,

324 (5th Cir. 1971), it becomes apparent that this form

of relief may not properly be viewed as a mere adjunct

of some more basic equity. It is properly viewed as an

integral part of the whole of relief which seeks, not to

punish the respondent but to compensate the victim of

discrimination. See NLEB v. J. H. Rutter-Rex Mfg.

Co., 396 U.S. 258, 90 S.Ct. 417, 24 L.Ed.2d 405 (1969);

Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers, Inc. (sic) Union v.

N.L.R.B., Part III, 144 U.S.App.D.C. 167, 445 F.2d 237

(1971). Cf. Social Security Board v. Nierotko, 327 U.S.

358, 66 S.Ct. 637, 90L.Ed. 718 (1946).19

United States v. Georgia Power Go., 474 F.2d 906, 921

(5th Cir. 1974).

And the Fourth and Seventh Circuits have given an even

broader reading to Title VII back pay entitlement in Moody 10 * * * * * * *

10 The relief provisions of Title VII were derived for a

similar provision in the National Labor Relations Act, 29

U.S.C.A. § 160(c). Monetary awards by the National Labor

Relations Board under this authority have been based upon

net back pay, and legislative history indicates that Congress

felt that the Title VII remedy should be similar. 110 Cong.

Rec. 6549 (1964); Developments — Title VII, [84 Harv. L.

Rev. 1109] supra note 8, at 1259 n. 349.

14a

v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 137 (4th. Cir. 1973), cert,

granted, 43 U.S.L.W. 3344 (II.S. Dee. 16,1974) (No. 74-389);

Boive v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969).

In the Pettway case Judge Tuttle examined the practical

problems of awarding back pay in another race discrimina

tion case involving promotion rights in language which we

commend to the attention of the District Judge on remand

of our instant case:

3. Determination of the award. Having decided that

the district court should grant back pay to the members

of the class, a multitude of questions arise concerning

the period of time encompassed by the back pay, the

burden of proof, and the mechanics of computation.

Some guidelines for the district court will be set forth.

Initially, we approve the district court’s intention of

referring the back pay claims to a Special Master, Fed.

R.Civ.P. 53. United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal

Lathers Int. Union, Local 46, 328 F.Supp. 429, 441 (S.D.

N.Y. 1971). However, the court and the parties may

also consider negotiating an agreement. E.g., Johnson

v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 349 F.Supp. 3, 18 (S.D.

Tex. 1972), 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. March 27, 1974);

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers, Int. Un

ion, Local 46, supra 328 F.Supp. at 444 n. 3. An alter

native is to utilize the expertise of the intervening

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to super

vise settlement negotiations or to aid in determining

the amount of the award.

% # #

This Court has recently addressed the issue of the

burden of proof on back pay claims in Johnson v. Good

year Tire & Rubber Co., supra, 491 F.2d 1364. This

Court pointed out that once a prima facie case of dis

crimination against the class alleged is made out, a

presumption for back pay arises in favor of class mem

bers. However, this presumption was found to be tern-

15a

pered by an initial burden on the individual employee

to bring himself within the class and to describe the

harmful effect of the discrimination on his individual

employment postion:

“ Therefore, the class represented by Johnson, hav

ing established a prima facie case of employment

discrimination, is presumptively entitled to back pay.

. . . Since, at the same time, the initial burden is now

placed on the individual labor department employee

to show that he is a member of the recognized class

subject to employment discrimination, we think it is

appropriate to offer some preliminary observations

concerning the manner in which the presumption in

favor of the class and the initial burden placed upon

an individual employee may be reconciled by the dis

trict court.

* # *

“ The district court’s task will be further compli

cated since the only criteria which Goodyear previ

ously imposed for transfer have been found by this

court to be invalid under Title VII. If an employee

can show that he was hired into the labor department

before April 22, 1971 and was subsequently frozen

into the department because of the discriminatory

practices established here, then rve think the individ

ual discriminatee has met his initial burden of proof

unless there are apparent countervailing factors

present.” Id. at 1379.

This holding is entirely consistent with, and flows from

our decision in Georgia Power that the presumption in

favor of a member of a class discriminated against does

not per se entitle an employee to back pay without some

individual clarification. 474 F.2d at 921-922.

This Court in Goodyear, then went on to detail the

burden on the employer:

“ . . . It will be incumbent upon Goodyear to show

by convincing evidence that other factors would have

16a

prevented his transfer regardless of the discrimina

tory employment practices. If Goodyear wishes to

show that a labor department employee would not

be qualified for any other job then its proof must be

clear and convincing. Any doubts in proof should be

resolved in favor of the discriminatee giving full and

adequate consideration to applicable equitable prin

ciples.” Id. at 1379, 1380.

There, just as in this case, our prior decision in Cooper

v. Allen, supra, 467 F.2d at 840, was instructive. In

Cooper, the district court had placed the burden on the

plaintiff to show, disregarding the discriminatory test

ing, that he was the most qualified for the job which he

was seeking back pay. This Court reversed:

“ On remand the City must prove by clear and con

vincing evidence that, in the light of the enumerated

qualifications, Cooper would not have been entitled to

the job even had there been no requirement to take

and pass the Otis test. That is, the City must show

that the person actually hired was on the whole better

qualified for the job.” Id. at 840.

Reading these earlier decisions together, it is clear

that the burden of proof formulated by this Court con

ceives an initial lighter burden on the back pay claimant

with a heavier weight of rebuttal on the employer.

Therefore, the maximum burden that could be placed on

the individual claimant in this case is to require a

statement of his current position and pay rate, the jobs

he was denied because of discrimination and their pay

rates, a record of his employment history with the com

pany and other evidence that qualified or would have

qualified him for the denied positions, and an estima

tion of the amount of requested back pay. The employ

er’s records, as well as the employer’s aid, would be

made available to the plaintiffs for this purpose. The

17a

burden then shifts to the company to challenge partic

ular class members’ entitlement to back pay. Pettway

v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 258-60

(5th Cir. 1974). (Footnotes omitted.)

Judge Tuttle continued then to discuss the complexity of

a back pay award in a discrimination case involving* denial

of promotions. He then turned to the ingredients of back

pay and his conclusion:

Finally, the ingredients of back pay should include

more than “ straight salary.” Interest, overtime, shift

differentials, and fringe benefits such as vacation and

sick pay are among the items which should be included

in back pay. Adjustment to the pension plan for mem

bers of the class who retired during this time should

also be considered on remand.

Conclusion

The declaratory and affirmative injunctive relief

should alleviate the perpetuated effects of the com

pany’s intentional discrimination and testing and edu

cational requirements. Back pay should compensate

for economic losses suffered during the period of test

ing and before the implementation of this decision.

Nevertheless, two additional elements of relief are

necessary. The district court should establish a com

plaint procedure by which a member of the class may

question the interpretation or implementation of the

district court’s decree. See United States v. Georgia

Power, supra, C.A. Nos. 12355, 11723, 12185. The pro

cedure should include the filing of a complaint with the

personnel department of the company and the proper

committee of the Board of Operatives (described

infra). Finally, the district court should retain this

case on the docket for a reasonable time to insure the

continued implementation of equal employment op

portunities. Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine

18a

Co., supra, 457 F.2d at 1383; Parham v. Southwestern

Bell Telephone Co., supra, 433 F.2d at 429. Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra at 263-64. (Foot

notes omitted.)

Additionally, we note that two circuits have already en

tered orders requiring affirmative action to make whole

parties who have been discriminatorily refused employment

at the hiring office. In a very recent case the Fifth Circuit

said:

The remedies authorized in Title VII specifically in

clude back pay. As indicated above, the purpose of

Title VII is to make the discriminatee whole and elimi

nate the effects of past discrimination as far as possible.

Where the discriminatee has suffered economic injury

in the form of lost wages, back pay is normally ap

propriate relief. Harkless v. Sweeny Independent

School District, 5th Cir. 1970, 427 F.2d 319, 324. Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398, 421 (5th

Cir 1974).

See also, Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th

Cir. 1973), cert, granted, 43 U.S.L.W. 3344 (U.S. Dec. 16,

1974) (No. 74-389).

As we have already indicated, we believe that the District

Judge erred in holding that he was without authority to en

ter back pay awards to the discriminatees before him. In ad

dition to the injustice to the victims of illegal discrimina

tion, such a policy prohibiting back pay because of the diffi

culty of computing it actually would encourage employers

who had the inclination to disregard this act to do so with

impunity, knowing that in the end the worst could happen

to them is that they might be ordered to hire women wholly

prospectively. We recognize the practical difficulties of de

termining that actual damage has occurred. The initial

burden of proof rests upon the job claimant to establish that

she sought employment and that she was eligible for a then-

19a

existing job. She can, of course, take advantage of Ford em

ployment records in establishing a prima facie case. At this

point the burden would then shift to Ford to show a legiti

mate business reason for the job refusal. Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

Assuming that eligibility for back pay was ascertained

within the realm of reasonable probability (and no more

can be asked here), evidence would also have to be taken

pertaining to mitigating of damages because some of these

claimants may have secured work in the meantime.

Reference of these back pay claims to a Special Master

and pretrial conferences before him to narrow the fact dis

putes which need actual testimony are practical answers to

some of the problems presented by claims for back pay

awards.

If eligibility and discriminatory refusal are established,

then back pay should be fully awarded, including compen

sation for fringe benefits then enjoyed by employees. See

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 263

(5th Cir. 1974).

Sestiobity

Whatever the difficulties of determining back pay awards,

the award of retroactive job seniority offers still greater

problems. Seniority is a system of job security calling for

reduction of work forces in periods of low production by

layoff first of those employees with the most recent dates of

hire. It is justified among workers by the concept that the

older workers in point of service have earned their reten

tion of jobs by the length of prior services for the particu

lar employer. From the employer’s point of view, it is

justified by the fact that it means retention of the most

experienced and presumably most skilled of the work force.

Obviously, the grant of fully retroactive seniority would

collide with both of these principles.

Ill addition, where the burden of retroactive pay falls

upon the party which violated the law, the burden of

retroactive seniority for determination of layoff would fall

directly upon other workers who have themselves had no

hand in the wrongdoing found by the District Court,

There is, however, no prohibition to be found in the

statute we construe in this case which prohibits retroactive

seniority and, of course, the remedy for the wrong of dis

criminatory refusal to hire lies in the first instance with

the District Judge. For his guidance on this issue we ob

serve, however, that a grant of retroactive seniority would

not depend solely upon the existence of a record sufficient

to justify back pay under the standards of the Back Pay

Section of this opinion. The court would, in dealing with

job seniority, need also to consider the interests of the

workers who might be displaced as well as the interests of

the employer in retaining an experienced work force. We

do not assume, as our brethern in the Fifth Circuit appear

to (Local 189, AFL-GIO, CLC v. United States, 416 F.2d

980, cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)), that such reconcilia

tion is impossible, but as is obvious, we certainly do foresee

genuine difficulties. See also Jurinho v. Edwin L. Wiegand

Co., 477 F.2d 1038 (3d€ir.), vacated, 414 U.S. 971 (1973),

reinstated, ■— F.2d —t, 7 FEP 787 (3d Cir. 1974). Cf. Local

189, supra; Franks v. Boivmun Transportation Co., 495

F.2d 398 (5th Oir. 1974).

On remand the District Judge may desire to hear the

policy questions involved in this problem before remanding

the individual claims to the Master. For purposes of that

hearing notice should be given to the employees likely to be

affected and intervention should be allowed from appropri

ate representatives.

What we have said concerning job seniority does not, of

course, apply to the fringe benefits of employment. Where

vacation schedules or pension rights (or other fringe bene

21a

fits) are determined by date of hire, we perceive no reason

why that date in these cases should be other than the date

which the trial court fixes as the date when the employee

would have been hired, absent the illegal hiring practice

which the District Court has identified and enjoined.

T he Class

We affirm the determination of the class as set forth in

the District Judge’s opinion and order, except that mem

bership therein should also be allowed to applicants be

tween April 1, 1971, and January 26, 1973, when the 150

lb. rule was enjoined. We find no abuse of discretion in

the District Judge’s refusal to accept an amendment to

this complaint so as to add to the problems of these plain

tiff’s and this plant (the Kentucky Truck Plant) the prob

lems of applicants for employment at the Grade Lane Auto

Assembly Plant. No present plaintiff applied for or was

refused employment at the Grade Lane plant, and we do not

perceive that reversal is mandated in the interests of

judicial economy. Hopefully this case will supply appli

cable precedent if indeed the same practices prevailed at

Great Lane.

A ttobhey P ees

We likewise find no abuse of discretion in the District

Judge’s award of attorney fees covering the work per

formed up to the dates considered by him. The case has,

however, required additional legal services thereafter both

in the District Court and on appeal which were not dealt

with by his judgment. We therefore vacate the fee portion

of the judgment and remand this aspect of the appeal for

further consideration.

The judgment of the District Court is affirmed as modi

fied above, and the case is remanded to the District Court

for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. Costs

to appellants.

22a

Judgment—Entered December 12,1973

Pursuant to Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

entered on August 23, 1973, it is hereby ordered, adjudged

and decreed that:

1. The Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law en

tered by the Court in this Action on August 23, 1973, are

hereby incorporated herein by reference, as if fully copied

herein.

2. There are thirty-one (31) members of the Class rep

resented by the Plaintiff in the instant action; the names,

addresses and telephone numbers of the said members of

the class are attached hereto and made a part hereof as if

fully copied herein.

3. The use by the Defendant under the circumstances

before the Court of the 150 pound weight requirement for

eligibility for employment on its production line at its Ken

tucky Truck Plant constitutes an unlawful employment

practice pursuant to the terms of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l et seq.

4. Neither the Plaintiff nor any member of the class is

entitled to any award of damages. Plaintiff is awarded its

costs herein expended and counsel fees in the sum of

$11,500.00.

5. The Defendant, Ford Motor Company, be and hereby

is permanently enjoined and prohibited from applying the

150 pound weight requirement for eligibility for employ

ment on its production line at its Kentucky Truck Plant.

6. The names of the Plaintiff and the thirty-one (31)

members of the class represented by the Plaintiff shall be

placed by the Defendant in a priority employment pool in

the order of the dates of their original application for pro

duction employment, The names of all other applicants

for production employment are to be placed in a general

pool in accordance with the present practice of Defendant.

As production employment positions become available,

APPENDIX B

23a

Defendant shall select names from the two pools of appli

cants at a set ratio of one name from the priority pool for

every three names from the general pool, and these individ

uals are to be notified by the Defendant of the job openings

as they occur and given a reasonable opportunity to appear

for a pre-employment physical examination and the other

processes regularly required of such applicants.

7. Individuals from the priority pool called pursuant

to this procedure are entitled to no preference in regard to

regularly applied job requirements, and said individuals

must meet other regularly applied employment require

ments of the Defendant before production employment must

be granted them by the Defendant.

8. The procedure outlined above shall be followed by

the Defendant until all names in the priority pool have been

exhausted, or until the expiration of 18 months from the

date of this Judgment, whichever first occurs.

9. The three-to-one ratio established above in no way

implies the defendant must, as a matter of general practice,

employ one female for every three males employed for pro

duction work, nor does this Judgment mean that the de

fendant must establish a ratio of any type regarding the

employment of males and females for such production work

in the future.

10. This Court shall retain jurisdiction of this action

for a period of 18 months following the entry of this Judg

ment to insure the continued implementation of what now

appears to be the defendant’s policy of equal employment

opportunities at its Kentucky Truck Plant.

It is Further Ordered that this action is dismissed with

prejudice as to the defendant, International Union, United

Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Work

ers of America, Local 862.

(s) Chables M. A llex

December 11, 1973 United States District Judge

cc : Counsel of Record

24a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 74-1258

74-1259

Delores Marie Meadows, Plaintiff-Appellant,

Gross-Appellee,

Y.

F ord Motor Company, Defendant-Appellee,

Cross-Appellant,

L ocal 862, I nternational U nion, U nited A utomobile,

A erospace and I mplement W orkers of A merica; and

International U nion, U nited A utomobile, A erospace

and A gricultural Implement W orkers of A merica,

D efendants-App ellees.

Before: E dwards and Miller, Circuit Judges, and

McA llister, Senior Circuit Judge.

Judgment

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Kentucky.

T his Cause came on to he heard on the record from the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Kentucky and was argued by counsel.

On Consideration W hereof, It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said

District Court in this cause be and the same is hereby

affirmed as modified and the case is remanded for further

proceedings.

APPENDIX C

It is further ordered that Plaintiff-Appellant, Cross-

Appellee recover from Defendant-Appellee, Cross Appel

lant, the costs on appeal, as itemized below, and that