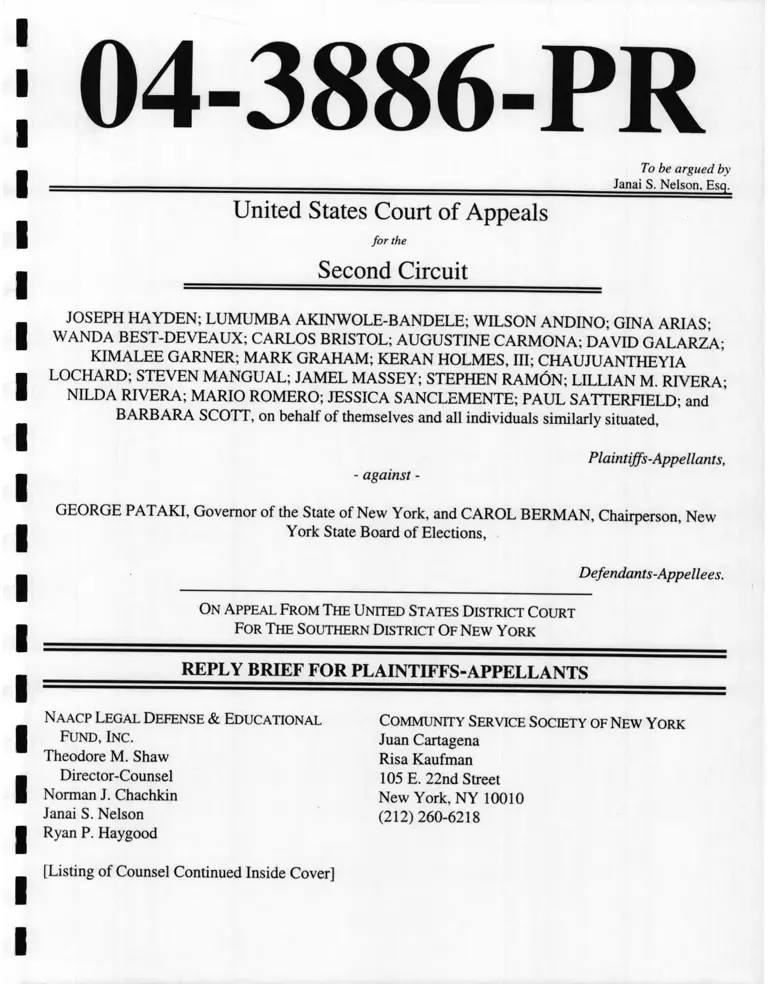

Hayden v. Pataki Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 8, 2004

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hayden v. Pataki Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 2004. 870608d5-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/198e2d3d-b161-4f38-9dde-008150587a8a/hayden-v-pataki-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

04-3886-PR

JOSEPH HAYDEN; LUMUMBA AKINWOLE-BANDELE; WILSON ANDINO; GINA ARIAS;

WANDA BEST-DEVEAUX; CARLOS BRISTOL; AUGUSTINE CARMONA; DAVID GALARZA;

KIMALEE GARNER; MARK GRAHAM; KERAN HOLMES, III; CHAUJUANTHEYIA

LOCHARD; STEVEN MANGUAL; JAMEL MASSEY; STEPHEN RAMON; LILLIAN M. RIVERA;

NILDA RIVERA; MARIO ROMERO; JESSICA SANCLEMENTE; PAUL SATTERFIELD; and

BARBARA SCOTT, on behalf of themselves and all individuals similarly situated,

GEORGE PATAKI, Governor of the State of New York, and CAROL BERMAN, Chairperson, New

York State Board of Elections,

To be argued by

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

United States Court of Appeals

for the

Second Circuit

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of New York

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Naacp Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc. Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

Community Service Society of New York

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel 105 E. 22nd Street

New York, NY 10010

(212) 260-6218

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

[Listing of Counsel Continued Inside Cover]

Naacp Legal Defense & Educational

Fund , Inc. (cont’d)

Alaina C. Beverly

Debo P. Adegbile

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, NY 11225

(718) 270-6296

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................................................................... a

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT...............................................................................1

ARGUMENT............................................................................................................ 2

I- Defendant, Like the District Court, Misapplies the Rule 12(c)

Standard..................................................................................................2

II. Plaintiffs Have Alleged Sufficient Facts of Intentional Discrimination

that Are Not Refuted by Defendant’s Misleading Interpretation of the

Legislative History of New York’s Felon Disfranchisement Laws ......7

A. Defendant and the District Court Ignore the Arlington Heights

Standard for Pleading Intentional Discrimination that Plaintiffs

Have Clearly Met........................................................................... 8

B. Defendant Misstates the Legislative Record in Support of His

Purge Argument, which Fails Both As A Matter of Law and Fact

at this Stage ..................................................................................13

III. Defendant Has Not Proven that New York’s Felon Disfranchisement

Laws Were Purged of Their Discriminatory Taint, Nor Is that

Determination Appropriate for a Rule 12(c) Proceeding......................19

IV. Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection Claim Is Not Barred by Richardson or

Baker Nor Is It Subject to Rule 12(c) Dismissal without Further

Development of the Record...................................................................24

V. Plaintiffs’ Voting Rights Act Claims Should be Preserved Pending

Final Disposition in Muntaqim.............................................................30

CONCLUSION.............................................................. 31

i

Papes

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Baker v. Cuomo. 58 F.3d 814 (2d Cir. 1995), vacated bv

Baker v. Pataki, 85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir. 1996)...............6, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30

Burdick v. Takushi.

504 U.S. 428 (1992)................................................................................27

Carolene Prod. Co. v United States.

323 U.S. 18 (1944).................................................................................. 5

Chen v. City of Houston, cert, denied.

206 F.3d 502 (5th Cir. 2000), cert, denied. 532 U.S. 1046 (2001)... 21 n.5

Clark v. Jeter.

486 U.S. 456(1988)................................................................................. 27

Cotton v. Fordice.

157 F.3d 388 (5th Cir. 1998)..................................................................21

DeMuria v. Hawkes.

328 F.3d 704 (2d Cir. 2003)...................................................................... 3

Dunn v. Blumstein.

405 U.S. 330(1972)................................................................................. 28

Enslev Branch. NAACP v. Siebels.

31 F.3d 1548, 1575 (11th Cir. 1994)......................................................22

Green v. Bd. of Elections.

380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967).............................................................28, 29

Hunter v. Underwood.

471 U.S. 222 (1985)................................ 11, 12, 14 n.3, 20, 21 n.4, 22, 24

Illinois Bd. of Elections v. Socialist Workers Party.

440 U.S. 173 (1979)................................................................................ 27

Irish Lesbian & Gay Org. v. Giuliani.

143 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 1998)....................................................................... 3

ii

Cases (Cont’d) Pages

Knight v. Alabama.

14 F.3d 1534(11th Cir. 1994)................................................................. 22

Landell v. Sorrell. 382 F.3d 91, 135 n.24 (2d Cir. 2004)

382 F.3d 91(2d Cir. 2004)......................................................................... 5

Mt. Healthy City Bd. of Educ. v. Dovle.

429 U.S. 274(1977)................................................................................. 20

Muntaqim v. Coombe.

366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004), pet, for cert, filed.

73 U.S.L.W. 3113 (U.S. July 21, 2004)....................................... 2, 30, 31

Patel v. Contemporary Classics of Beverly Hills.

259 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2001).............................................................. 3, 7-8

Personnel Adm’r of Mass, v. Feeney.

442 U.S. 256 (1979)................................................................................. 20

Phillip v. Univ. of Rochester.

316 F.3d 291 (2d Cir. 2003)............................................................. 20 n.4

Ramos v. Town of Vernon.

353 F.3d 171 (2d Cir. 2003).............................................................. 27,28

Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964)................................................................................ 27

Richardson v. Ramirez.

418 U.S. 24 (1974),......................................................... 24, 25, 26, 28, 29

Romer v. Evans.

517 U.S. 620(1996)................................................................................. 29

Scutti Enter.. LLC v. Park Place Entm’t Corn..

322 F.3d 211 (2d Cir. 2003).....................................................................3

Underwood v. Hunter.

730 F.2d 614 (11th Cir. 1984), affd . 471 U.S. 222 (1985)................... 12

iii

United States v. Hemandez-Fundora.

58 F.3d 802 (2d Cir. 1995)....................................................................... 4

United States v. Coleman.

166 F.3d 428 (2d Cir. 1999)(per curiam)............................................... 27

United States v. Fordice.

505 U.S. 717(1992)......................................................................... 21,22

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corn..

429 U.S. 252 (1977)........................................................................ 8, 9, 10

Williams v. Apfel.

204 F.3d 48 (2d Cir. 1999).......................................................................3

Constitutions, Statutes & Rules

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV....................................................................... 16, 17

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 .................................................................................17

Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c)...............................................................................passim

Fed. R. Civ. P. 56............................................................................................ 2

Fed. R. Evid. 201, Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules........................... 4

Fed. R. Evid. 201(e)...................................................................................... 6

N.Y. Elec. Law § 5-106................................................................... 24, 27 n.6

Miscellaneous

Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New

York City to 1898 (19981.......................................................................15

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess................................................................15

Cases (Cont’d) pages

IV

Kenneth Davis. An Approach to Problems of Evidence in the

Administrative Process. 55 Harv . L. Rev . 364 (1942)..... 4

Phyllis F. Field, The Politics of Race in New York: The Struggle for

Black Suffrage in the Civil War Era (19821..................................... 14, 15

David Nathaniel Gellman & David Quigley, Jim Crow New York: A

Documentary History of Race and Citizenship. 1777-1877 (NYU

Press 2003)..............................................................................................15

John T. Hoffman Address (Jan. 5, 1869) in Messages from the

Governor. Vol. 6 (T 869-18761 (Charles Z. Lincoln, ed. 1909)............. 16

John T. Hoffman Address (Jan. 1870) in Messages from the

Governor. Vol. 6 0869-1876) (Charles Z. Lincoln, ed. 1909).............16

John T. Hoffman, Speech to Erie County Democrats in Buffalo (Sept.

8, 1868) in N.Y. Times, Sept. 9,1868..................................................... 16

Irish Citizen. October 19, 1867.................................................................... 16

Journal of the New York State Constitutional Convention Committee,

Begun and Held in the Common Council Chamber, in the City of

Albany, on the Fourth Day of December. 1872 (Weed, Parsons &

Co., 1873)............................................................................................... 18

Charles Z. Lincoln, The Constitutional History of New York from the

Beginning of the Colonial Period to the Year 1905. Showing the

Origin. Development, and Judicial Construction of the

Constitution (1906)............................................................................ 16-17

David Quigley, Second Founding: New York City. Reconstruction.

and the Making of American Democracy (2004)................................... 16

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Plaintiffs have clearly demonstrated that the district court’s Rule 12(c)

dismissal of their claims challenging New York’s felon disfranchisement laws

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution

was in error. As a threshold matter, Defendant George Pataki1 concedes that

Plaintiffs meet the basic pleading requirements for an intentional discrimination

claim and does not challenge the sufficiency of the pleadings with respect to any of

the claims on appeal. Moreover, not only does Defendant Pataki’s response2 offer

no reliable justification for upholding the decision below, it highlights the

searching and exacting factual inquiry merited by Plaintiffs’ claims that was

thwarted by the district court’s premature dismissal of Plaintiffs’ complaint.

Defendant attempts to circumvent this inquiry by misleading the court on the

content and interpretation of the legislative history at issue and by limiting the

analysis of Plaintiffs’ claims to the legislative record when a fuller examination is

1 Defendant George Pataki, Governor of the State of New York, (“Defendant

Pataki” or “Defendant”) submitted a brief in response to Plaintiffs’ opening brief

on appeal on behalf of himself and Glenn S. Goord, Commissioner of New York

State Department of Correctional Services. Commissioner Goord was dismissed

from this action upon the filing of Plaintiffs’ First Amended Complaint (“Amended

Complaint”) in January 15, 2003. Carol Berman, Chairperson of the New York

State Board of Elections, who is a current Defendant in this lawsuit, did not file a

response to Plaintiffs’ brief on appeal.

' Brief for Defendants-Appellees Pataki and Goord [sic] (“Defendant’s Response”

or “Def’s Br.”).

1

required. However, Plaintiffs have pleaded sufficient facts that are supported by

the legislative record and historical context, to withstand dismissal under Rule

12(c). Likewise, Plaintiffs have shown that the disparate application of New York

State’s felon disfranchisement statute among persons with felony convictions is

subject to heightened scrutiny that requires further factual development by the

parties. Finally, the intervening petition for rehearing en banc in Muntaaim v.

Coombe. counsels toward vacating the district court’s dismissal of Plaintiffs’

Voting Rights Act claims.

ARGUMENT

I. DEFENDANT, LIKE THE DISTRICT COURT, MISAPPLIES THE

RULE 12(c) STANDARD

While it is unclear what standard the district court used in dismissing

Plaintiffs’ claims, Defendant stipulates that “the complaint’s allegations satisfy []

minimal pleading requirements.” Defs Br. at 12. However, like the district

court’s opinion below, Defendant’s Response conflates the standard for

withstanding a Rule 12(c) motion with the standard required to prevail on a Rule

56 motion for summary judgment, and urges the Court to engage in an

unwarranted investigation of the merits of this case.

2

As set forth in their opening brief, Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint alleges

specific facts demonstrating intentional discrimination and disparate application of

New York’s felon disfranchisement laws. If construed in the light most favorable

to the Plaintiffs and accepted as true, as required by Rule 12(c), these allegations

entitle Plaintiffs to relief. DeMuria v. Hawkes. 328 F.3d 704, 706 (2d Cir.

2003)(citing Scuttie Enters, v. Park Place Entm’t Corp.. 322 F.3d 211, 214 (2d Cir.

2003)); Patel v. Contemporary Classics of Beverly Hills. 259 F.3d 123, 126 (2d

Cir. 2001)(citing Irish Lesbian & Gay Org. v, Giuliani. 143 F.3d 638, 644 (2d Cir.

1998)). By presenting issues of fact that were never raised before the district court,

and inviting interpretations of legislative history that are at best contested,

Defendant seeks to have this Court conduct an evidentiary exercise that is

improper at this stage in litigation.

Specifically, Defendant suggests that this Court should blindly accept his

narrow and misleading interpretation of the legislative history of New York’s felon

disfranchisement provisions. However, Defendant’s argument that the legislative

history of New York’s felon disfranchisement provisions “decisively

demonstrates,” Def’s Br. at 9, his position that subsequent re-enactments of the

laws removed any discriminatory intent is nothing more than Defendant’s opinion

about a severely contested factual issue that cannot be resolved without a remand

for further discovery. See Williams v. Apfeh 204 F.3d 48, 50 (2d Cir. 1999)

3

(vacating a district court judgment and remanding for further proceedings where

the administrative record was undeveloped).

Defendant asks this Court to take judicial notice of his interpretation of the

legislative history of the laws in question. Def s Br. at 12-14. However, the

Advisory Committee Notes to Rule 201, Fed. R. Evid., state that the Rule “deals

only with judicial notice of ‘adjudicative’” and not “legislative” facts and defines

legislative facts as those “which have relevance to legal reasoning and the law

making process, whether in formulation of a legal principle or [ ] in the enactment

of a legislative body.” See Fed. R. Evid. 201 Notes of Advisory Committee on

Rules citing Kenneth Davis, An Approach to Problems of Evidence in the

Administrative Process. 55 Harv. L. Rev. 364, 404-407 (1942). Defendant admits

in his brief that “legislative intent is not an adjudicative fact but a legislative one,”

Def s Br. at 14, making it clear that his proffered interpretation of legislative

history does not fall under Rule 201. See also United States v. Hemandez-

Fundora, 58 F.3d 802, 811 (2d Cir. 1995) (“[RJesolution of the jurisdictional issue

[ ] requires the determination of legislative facts, rather than ‘adjudicative facts’

within the meaning of Rule 201(a), with the result that Rule 201(g) is

inapplicable.”).

4

Although courts have taken judicial notice of legislative history showing the

reason for the passage of certain legislation, see, e ^ , Carolene Prod. Co. v. United

States, 323 U.S. 18, 28 (1944) (“The trial court took judicial notice, as did the

District Court of the District of Columbia, and as we do, of the reports of the

committees of the House of Representatives and the Senate which show that other

considerations [] influenced the [legislation at issue].”), this Court has held that it

may not take notice of legislative facts if those facts are in dispute and especially

when they are dispositive and the record is not developed. Landed v. Sorrell. 382

F.3d 91, 135 n.24 (2d Cir. 2004) (“The fact that this Court may ultimately

undertake de novo review of any legislative facts found by the District Court on

remand or that appellate courts take judicial notice of legislative facts under

appropriate circumstances, does not mean that we must resolve disputed legislative

facts — particularly facts that are dispositive of the case before us — on an

insufficiently developed record.”). Indeed, Landed states that the legislative facts

addressed by this Court have largely dealt with straightforward questions such as

geography, jurisdiction, or scientific fact. Id (“[T]he types of ‘legislative facts’

that have been addressed most recently in our caselaw deal with much more

straightforward questions, e.g., geography and jurisdiction or the fact that cocaine

is derived from coca leaves.”). Accordingly, this Court should not take judicial

notice of Defendant’s proffered interpretation of the legislative history of New

5

York’s felon disfranchisement laws, and certainly not in the context of a Rule

12(c) determination. Moreover, should this Court determine that judicial notice is

appropriate, Plaintiffs must be afforded an adequate opportunity to be heard on this

issue. See Fed. R. Evid. 201(e).

Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint also sufficiently alleges that New York’s

felon disfranchisement provisions, as applied, make impermissible distinctions

among persons with felony convictions. Defendant argues that Baker v. Cuomo.

58 F.3d 814 (2d Cir. 1995), vacated by Baker v. Pataki, 85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir.

1996), forecloses Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection claim. Def’s Br. at 25, 28-29.

However, Baker does not foreclose Plaintiffs’ argument that this case should be

vacated and remanded for development of a complete factual record necessary to

support heightened scrutiny, or a rational basis equal protection analysis, regarding

the severity of the crimes committed by individuals sentenced to incarceration or

parole (as compared to probationers) and the implications of prohibiting such

individuals to exercise their fundamental right to vote. See Baker. 58 F.3d at 818-

819. Therefore, dismissal below should be reversed and this case remanded for

further proceedings.

6

II. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ALLEGED SUFFICIENT FACTS OF

INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION THAT ARE NOT REFUTED

BY DEFENDANT’S MISLEADING INTERPRETATION OF THE

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF NEW YORK’S FELON

DISFRANCHISMENT LAWS

Against the weight of legislative history to the contrary, Defendant alleges

that the “legislative histories of the challenged [felon disfranchisement] provisions

demonstrate that the plaintiffs’ allegation of discriminatory legislative intent fail

[sic] as a matter of law.” Def’s Br. at 10. To support this assertion, Defendant

attempts to divert this Court’s attention from the discriminatory origins of New

York’s felon disfranchisement statute (the corrosive effects of which endure to this

day) by claiming that an alleged “redrafting of the constitutional provisions” more

than half a century later in 1874 and “statutory amendments of 1971 and 1973”

purged the provisions of their discriminatory intent. Id. “Consequently,”

Defendant concludes, “the plaintiff[s] can prove no facts” in support of their

intentional discrimination claim that would entitle them to relief. Id, at 10-11. As

we show below, Defendant’s argument is factually erroneous because (like the

opinion below) it fails to address the naked reality of New York’s long history of

intentional discrimination against Blacks in voting.

Defendant also relies on a misstatement of established legal principle. To

satisfy a Rule 12(c) motion, Plaintiffs need only state facts, which taken together as

true, would entitle them to relief under a particular claim. See Patel, 259 F.3d at

7

126. Here, Plaintiffs assert that New York’s extensive history of intentional racial

discrimination in voting dates back to its Constitution in 1777 and spans more than

a century. During this time, delegates to Constitutional Conventions and

legislators purposefully erected barriers (culminating in the mandated enactment of

a felon disqualification statute) that were intended to, and have had the effect of,

disfranchising Blacks and other racial minorities. These allegations, taken as true,

sufficiently state the basis for this Court to find a violation of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment.

A. Defendant and the District Court Ignore the Arlington Heights

Standard for Pleading Intentional Discrimination that Plaintiffs

Have Clearly Met.

By suggesting that Plaintiffs attempted in their Amended Complaint to make

a “prima facie case” that New York’s felon disfranchisement statute was “enacted

with the intent to “disenfranchise [sic] Blacks,” Def’s Br. at 11, Defendant, like the

district court, seeks to heighten the standard for alleging intentional discrimination

under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The appropriate

test for determining whether a facially neutral state law that has a racially disparate

impact violates the Equal Protection Clause was outlined by the Supreme Court in

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp.. 429 U.S. 252 (1977). In

Arlington Heights, the Supreme Court held that proof of intent to discriminate can

be derived from a contextual analysis of a variety of factors that collectively

8

support an inference of racial animus — including that the impact of an action

bears more heavily on one race than another, the historical background of an

official decision, and the legislative or administrative history of an official action,

particularly where there are statements by members of the decision-making body.

429 U.S. at 266-267 (finding that “whether invidious discriminatory purpose was a

motivating factor demands a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available”).

Arlington Heights requires an evaluation of these factors taken as a whole—

and not in isolation as the Defendant and the district court did here—in order to

appreciate the full context of the origin and effect of a challenged law. Contrary to

the holding of Arlington Heights, however, Defendant relies exclusively on limited

portrayals of “legislative histories of the most recent substantive amendments to

the challenged statutory and constitutional provisions,” Def’s Br. at 12, to

demonstrate a nondiscriminatory legislative intent, and proffers that inadequate,

narrow interpretation as the justification for the district court’s dismissal.

To substantiate their intentional racial discrimination claim, Plaintiffs cited

telling portions of the available historical background and legislative history of

New York’s felon disfranchisement restrictions, (JA 00105-109 [FAC 39-60]),

and their disproportionate impact on Blacks and Latinos. (JA 00109-00111 [FAC

9

11 61-71]). Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint contains numerous, specific

allegations that support a complete review by the trial court of the “circumstantial

and direct evidence of intent as available,” Arlington Heights. 429 U.S. at 266,

regarding the central role of race in the enactment of New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws.

Specifically, the Amended Complaint alleges that, in the 18th and 19th

centuries, both the Legislature and delegates to the various New York State

Constitutional Conventions — intended to, and did, discriminate against Blacks

with respect to the franchise and made “explicit statements of [their] intent” to that

effect. (JA 00106 [FAC 1 41]). The Amended Complaint sets forth the

unmistakable, de jure limitations on the ability of Black New Yorkers to vote, (JA

00106 [FAC f f 43-45]), that provided an historical context for the actions taken at

the 1821 New York Constitutional Convention — a convention dominated by an

express, racist purpose to deprive the vote from “men of color.” (JA 00107 [FAC

148]). Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint also alleges that Blacks in New York have

been routinely denied suffrage on an equal basis as whites, (JA 00105-107 [FAC

11 39-50]), were openly regarded by various state legislators and delegates

to constitutional conventions as being biologically inferior and, therefore, unfit for

suffrage, (JA 00106-107 [FAC11 46, 51]), and were described as being 13 times as

likely as whites to commit infamous crimes. (JA 00107 [FAC 151]).

10

Rather than refuting the discemable discriminatory origins of New York’s

felon disfranchisement regime at the 1821 Constitutional Convention, Defendant

assumes, arguendo, that New York’s “provision was added in 1821 and then

retained in 1846 with the purpose of disenfranchising [B]lacks.” Def s Br. at 18,

and then asserts that an 1874 amendment, allegedly enacted for “an independent,

non-discriminatory purpose,” broke the causal chain. Def’s Br. at 18. Defendant’s

attempt to distract the Court by masking the central issue of New York’s original

discrimination through a tale of revisionist history is unavailing for two reasons.

First, contrary to Defendant’s and the district court’s erroneous conclusions,

the allegations contained in Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint are clearly sufficient

under Hunter, and are, as set out in detail in Plaintiffs’ opening brief, Pis.’ Mem. at

18-20, more detailed and specific than those alleged in the complaint in Hunter.

Second, Defendant puts forth unsupported assertions that the “extensive

redrafting of the constitutional provisions in 1874,” and the “recent statutory

amendments of 1971 and 1973 clearly demonstrate a permissible

nondiscriminatory intent,” Def’s Br. at 10, that can cure the invidious intent hat

gave rise to New York’s original felon disfranchisement provision. These

assertions are not only unsupported, but they are also insufficient under Hunter.

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S at 222, 232-33 (1985). There, the Supreme Court

11

found that the enactment of Alabama’s felon disfranchisement provision in 1901

was “motivated by a desire to discriminate against blacks on account of race and

the section continue [d] to have that effect” more than 80 years later. Id, “As

such,” the Court concluded, “it violates equal protection under Arlington Heights.”

Id. The Supreme Court also upheld the Eleventh Circuit’s ruling that, although the

current administrators of the law acted in “good faith” and without reference to

race, “neither impartiality nor the passage of time . . . can render immune a

purposefully discriminatory scheme whose invidious effects still reverberate

today.” Underwood v. Hunter, 730 F.2d 614, 621 (11th Cir. 1984)), aff’d. Hunter

v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985).

Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint sufficiently alleges the discriminatory

origins of the New York’s felon disfranchisement provision, and Defendant has

failed to show that the subsequent re-enactments purged New York’s felon

disfranchisement law of its discriminatory intent or effect. Defendant does not

demonstrate that later amendments to the felon disfranchisement laws were guided

by a recognition of the discriminatory origins of the provisions and a purpose to

remove the taint of racial bias or to demonstrate, as required by Hunter, 471 U.S. at

228, that prior discrimination is not still a motivating or substantial factor behind

New York’s felon disfranchisement laws. Defendant also ignores that the effects

12

of New York’s purposefully discriminatory felon disfranchisement law still

reverberate today.

B. Defendant Misstates the Legislative Record in Support of His Purge

Argument, which Fails Both As A Matter of Law and Fact at This

Stage.

Even if Defendant properly dealt with the original discrimination that

infected the enactment of New York’s felon disfranchisement statute, which he did

not, there is yet another deeply problematic aspect of Defendant’s argument: It

misstates the history of New York State between 1867 and 1874 in order to

persuade this Court that legislative action in the latter year was nondiscriminatory.

Specifically, Defendant asserts that the 1874 amendment to New York’s

Constitution, which replaced the permissive “may” with respect to felon

disfranchisement laws with the mandatory “shall,” was originated by delegates to

the 1867 Constitutional Convention who sought not intentionally to

“disenfranchise [B]lacks or other minorities, but [acted] as part of a larger project

aimed at preventing vote buying and other forms of ballot-box corruption.” Defs

Br. at 18-20. Defendant also asserts that “there is strong evidence of a concern to

protect the franchise for minorities.” Id, However, Defendant’s reference is to the

proceedings of 1867-68 Constitutional Convention, not the 1872-73 Constitutional

Commission and is, therefore, misleading and unreliable. See id.

13

Moreover, Defendant completely fails to recognize or account for the

political hurricane that stormed through New York between 1867 and 1874,

removing from power the Radical Republicans, who were sympathetic to Black

equal manhood suffrage, in favor of Democrats, who were vehemently opposed to

the same. This failure on Defendant Pataki’s part obscures rather than facilitates

an accurate understanding as to why the “shall” language was adopted in 1874. It

is to a discussion of the historical backdrop against which the 1874 amendment

was created that we briefly turn.3

The influence of Radical Republicans, who had a strong presence at the

1867-68 Constitutional Convention and opposed the 1821 voting requirement that

conditioned access to the franchise on a requirement that Blacks possess a freehold

estate worth $250, was severely weakened by a decisive Democratic victory in the

November 1867 elections. Phyllis F. Field, The Politics of Race in New York: The

Struggle for Black Suffrage in the Civil War Era (1982). “The overwhelming

majority of Democrats, however, were not willing to surrender on the race issue.”

3 It is important to note that this historical context is evidence that must be

developed through discovery, including expert reports and testimony, and is not

required to be proven or alleged in exhaustive detail by Plaintiffs at this stage in

the litigation. As in Hunter, Plaintiffs here should be afforded an adequate

opportunity to develop their case. Toward that end, Plaintiffs have retained an

expert who has conducted substantial research in support of their intentional

discrimination claim. However, the district court dismissed Plaintiffs’ claims

before discovery was concluded.

14

Mi at 173. Vehemently opposed to removing the racially discriminatory property

requirements, Democrats (who were emboldened by victories in the 1867 state

elections in which Black suffrage was a critical issue) put the issue to the voters of

New York in 1869, with the express understanding and expectation that New

Yorkers would oppose such a measure. See id. In 1869, New Yorkers, as

expected, voted to maintain the racially discriminatory language of the 1821

Constitution. David Nathaniel Gellman & David Quigley, Jim Crow New York: A

Documentary History of Race and Citizenship. 1777-1877 293 (NYU Press 2003).

Indeed, it was not until the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment (which New

York opposed by attempting to withdraw its earlier ratification of the Amendment,

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. at 1447-81), and the Federal Enforcement Acts

of 1870 and 1871, that equal manhood suffrage came to the Empire State, despite

the opposition of New York’s voters and political leadership, dominated by anti-

Black Democrats in 1870 and 1871. David Quigley, Second Founding: New York

City, Reconstruction, and the Making of American Democracy Ch. 5 (2004).

Moreover, the Governor of New York from 1869-1872 was John T.

Hoffman, Mayor of New York City from 1866-1868 and one of the leaders of

Manhattan’s Tammany Hall. Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A

History of New York City to 1898 927, 1009 (1998). In 1867, as Mayor of New

York City, amid the push by some for Black suffrage, Governor Hoffman declared

15

that “the people of the North are not willing . . . that there should be [N]egro

judges, [Njegro magistrates, [Njegro jurors, [Njegro legislators, [Njegro

Congressmen.” Irish Citizen. October 19, 1867, at 5. In Hoffman’s first speech of

his gubernatorial campaign in 1868, he declared that “in ten Southern States the

white man is subject to the domination of the [Njegro. [Applause.] That by an act

of Congress [Njegro suffrage is forced upon them, while white men are

disfranchised.” Hoffman’s speech to Erie County Democrats in Buffalo on

September 8, 1868, in New York Times. September 9, 1868, at 1. Consistent with

his deeply held racist beliefs, Governor Hoffman opposed the Fifteenth

Amendment, complaining that it was “another step in the direction of centralized

power.” Hoffman’s Address, January 5, 1869, Messages from the Governor.

Volume 6 (1869-1876) (Charles Z. Lincoln, ed. 1909). In 1870, Governor

Hoffman wrote: “I protest against the revolutionary course of Congress with

reference to amendments of the Constitution.” Hoffman’s Address, January 1870,

Messages from the Governor. Volume 6 (1869-1876) (Charles Z. Lincoln, ed.

1909).

Significantly, Governor Hoffman — in conjunction with the state Senate —

appointed the members (who are normally elected) to the State Constitutional

Commission of 1872-73, which drafted the revisions to the 1874 Constitution at

issue here. Charles Z. Lincoln, The Constitutional History of New York from the

16

Beginning of the Colonial Period to the Year 1905, Showing the Origin.

Development, and Judicial Construction of the Constitution 464-71 (1906).

Governor Hoffman’s anti-Black Democratic appointees in 1872-73 were not, as the

Defendant suggests, the Radical Republicans who grappled with issues of equal

manhood suffrage for Blacks at the 1867-68 Constitutional Convention. Indeed,

only six (or fewer than 20 percent) of the 32 delegates of the 1872-73 Convention

were veterans of the 1867-67 Convention. Id,

Though the 1872-73 Constitutional Commission strenuously debated

whether to replace the word “may” with “shall” in Article II, Section 2 of New

York’s Constitution, there was no clear move to embrace the anti-discriminatory

language of the Radical Republicans of 1867. Id. at 22, 96-97, 170. Instead, the

1872-73 Constitutional Commission, recognizing the impossibility of erecting

explicitly racial barriers in the aftermath of the Fifteenth Amendment, supported a

range of barriers — each of which disproportionately impacted New York’s Black

population.

First, as Plaintiffs alleged in their Amended Complaint, “two years after the

passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, an unprecedented committee convened and

amended the disfranchisement provision of the New York Constitution to require

the state legislature, at its following session, to enact laws excluding persons

17

convicted of infamous crimes from the right to vote . . . . Theretofore, the

enactment of such laws was permissive.” (JA 00108 [FAC f 56]). Second, they

urged the incorporation of literacy tests for suffrage in New York State. Journal of

the Constitutional Commission of the State of New York. Begun and Held in the

Common Council Chamber, in the City of Albany, on the Fourth Day of

December. 1872 339-93 (Weed, Parsons & Co. 1873). Third, they proposed a new

Article of the Constitution, number XIV, which focused on municipal government

and created a new Board of Audit for New York’s large cities, id. at 318, 373-74,

397; however, reminiscent of the 1821 property requirement that existed for Blacks

only until the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, only voters with $250 in

property would be allowed to elect members of such boards. Id. at 282.

Against this historical backdrop, Defendant’s assertion that the Radical

Republicans’ concern in 1867-68 to protect the ballot box from fraud “remained

the purpose of the amended section 2 when it was ultimately enacted [by anti-

Black Democrats] in 1874,” Def’s Br. at 23, is simply unsupported by a fair and

accurate reading of the historical record. Accordingly, Defendant’s conclusion —

that “[g]iven the lack of the ambiguity in the published record, this court should

conclude that no amount of extrinsic or circumstantial evidence” could provide

evidence of discriminatory intent, Def’s Br. at 24, is simply unreliable, and is an

18

unfortunate attempt to preclude New York’s historical discrimination against

Blacks in voting from coming to light.

When read together in the light most favorable to the Plaintiffs, the

allegations in the Amended Complaint tell a persuasive story of a pervasive pattern

of historical intentional discrimination in voting, including repeated explicit

statements about Blacks’ unfitness for suffrage, their perceived criminality, and the

codification of mandatory disfranchisement during an unprecedented special

session at a time when overt denial of the franchise to Blacks was newly outlawed

by the Fifteenth Amendment. These allegations satisfy the Rule 12(c) standard,

and justify reversal of the district court’s ruling.

III. DEFENDANT HAS NOT PROVEN THAT NEW YORK’S FELON

DISFRANCHISEMENT LAWS WERE PURGED OF THEIR

DISCRIMINATORY TAINT, NOR IS THAT DETERMINATION

APPROPRIATE ON A RULE 12(c) MOTION

In order to prevail on his argument that New York’s felon disfranchisement

laws have been purged of any original discriminatory intent, Defendant has the

burden of proving that the legislature enacted the 1874 amendment for wholly non-

19

discriminatory reasons, notwithstanding the racist origins of the felon

disfranchisement provision.4 Defendant has failed to meet his burden.

As the Supreme Court stated in Hunter, proof of discriminatory intent

underlying a specific policy in the past raises an inference that the discriminatory

purpose continues into the present, the passage of time and subsequent changes to

the policy notwithstanding. Hunter, 471 U.S. at 233. Indeed, as the Court noted,

“[o]nce racial discrimination is shown to have been a ‘substantial’ or ‘motivating’

factor behind enactment of the law, the burden shifts to the law’s defenders to

demonstrate that the law would have been enacted without this factor.” 471 U.S. at

228 (citing Mt. Healthy City Bd. of Educ. v. Dovle. 429 U.S. 274, 287 (1977)).

Here, Plaintiffs have clearly shown the discriminatory origins of the felon

disfranchisement provision. Thus, Defendant has the burden of proving that any

subsequent amendment to the law was enacted without a discriminatory intent, to

the extent that the amendment so changes the intention of the original enactment

that it cleanses it of its original discriminatory purpose. See Personnel Adm’r of

Mass, v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 266-70 (1979) (indicating that the gender

4 Defendant Pataki further recognizes that “on a 12(c) motion to dismiss the

defendants bear the burden of showing that ‘it appears beyond doubt that the

plaintiffs can prove no set of facts in support of his claim which would entitle him

to relief.’” Def’s Br. at 16 n.l (quoting Phillip v. Univ. of Rochester. 316 F.3d

291,293 (2d Cir. 2003)).

20

discriminatory purpose of veteran’s preference law may be found in its 1896

origins, notwithstanding the enactment of a number of subsequent amendments).

Indeed, as Justice Thomas noted in his concurring opinion in United States v.

Fordice, once a law is infected with racist intent, it is not easily cleansed: “[GJiven

an initially tainted policy, it is eminently reasonable to make the State bear the risk

of nonpersuasion with respect to intent a some future time, both because the State

has created the dispute through its own prior unlawful conduct, and because

discriminatory intent does tend to persist through time.” United States v. Fordice.

505 U.S. 717, 746-47 (1992) (Thomas, J., concurring). But see Cotton v. Fordice.

157 F.3d 388 (5th Cir. 1998) (requiring pro se plaintiff to prove that state enacted

amendment with discriminatory purpose).5

Likewise, in the context of de jure segregation, courts routinely examine

whether race-neutral policies have the effect of perpetuating past intentional racial

discrimination. In such cases, courts require that the state show that the original

taint of discriminatory intent has been purged and, that the state has taken

affirmative steps to remove the effects of past discrimination. See Fordice. 505

5 In Chen v. City of Houston. 206 F.3d 502, 521 (5th Cir. 2000), cert, denied. 532

U.S. 1046 (2001), the Fifth Circuit noted that the Cotton decision “broadly stands

for the important point that when a plan is reenacted — as opposed to merely

remaining on the books like the provision in Hunter — the state of mind of the

reenacting body must also be considered.”

21

U.S. at 729 (reiterating that states have an affirmative duty to dismantle the

vestiges of past de jure desegregation in higher education, which is not satisfied

“through the adoption and implementation of race-neutral policies alone”); see also

Knight v. Alabama, 14 F.3d 1534, 1540 (11th Cir. 1994) (requiring state to prove

that it has dismantled past discrimination “root and branch”) (quoting Fordice. 505

U.S. at 728).

In this context, proving that an amendment neutralizes the original

discriminatory purpose of New York’s felon disfranchisement law thus requires a

meaningful and demanding inquiry into the legislative history of the amendment.

Indeed, in order to neutralize a discriminatory law by showing that “the law would

have been enacted without [the discriminatory motive],” Hunter. 471 U.S. at 228,

Defendant must show that the prior discrimination is not still one of the motivating

or substantial factors behind the challenged policy. The state cannot merely

reenact or amend a purposefully discriminatory policy and thereby perpetuate its

prior discrimination. See Enslev Branch. NAACP v. Siebels. 31 F.3d 1548, 1575

(11th Cir. 1994) (noting that, in an employment context, “[pjublic employers

cannot escape their constitutional responsibilities merely by adopting facially-

neutral policies that institutionalize the effects of prior discrimination and thus

perpetuate de facto discrimination”).

22

Here, after a long history of using felon disfranchisement to prevent Blacks

from voting, New York’s legislators sought to amend the state’s constitution to

mandate such disfranchisement. Defendant takes numerous occurrences and

statements out of context to assert that the justification for the amendment was

nondiscriminatory. See supra Section II. Defendant’s meager evidence, however,

fails to prove that the 1874 amendment was enacted with a wholly non

discriminatory purpose. Had Defendant shown, for example, that delegates to the

1874 Constitutional Convention were actually aware of the felon disfranchisement

provision’s past discriminatory purpose and contemporary effect, but nevertheless

re-enacted it for a different, bona fide, nondiscriminatory reason, the result might

be different. However, Defendant offers no evidence that the legislature

acknowledged the discriminatory genesis of the law and adopted the amendment

for a wholly different purpose. Defendant does not even offer convincing proof

that the amendment was enacted for the non-discriminatory reasons he states. He

offers only fragments of ahistorical evidence from a previous constitutional

convention, which it contends is incontrovertible proof that the 1874 amendment

was enacted for nondiscriminatory reasons. In fact, the amendment can reasonably

be interpreted as intending to perpetuate the past discriminatory purpose while at

the same time guaranteeing its continuation. Additionally, Plaintiffs have been

denied the opportunity to refute Defendant’s evidence with historical fact and

23

expert opinion. See supra Section I. Thus, Defendant has failed to prove that the

1874 amendment to New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme adequately

cleansed the provision of its discriminatory purpose.

Similarly, Defendant’s failure to show that the 1874 Constitutional Convention

purged the original discriminatory intent of New York’s constitutional felon

disfranchisement provision defeats his argument that the 1971 and 1973

amendments, which were enacted pursuant to the 1874 Constitutional Convention,

do not “contain the slightest hint of discriminatory intent.” Defs Br. at 17.

Moreover, Defendant’s argument regarding the 1971 and 1973 amendments fails to

satisfy the standards in Hunter and, therefore, does not provide a basis for

upholding the district court’s dismissal of Plaintiffs’ intentional discrimination

claims.

IV. PLAINTIFFS’ EQUAL PROTECTION CLAIM IS NOT BARRED

BY RICHARDSON OR BAKER NOR IS IT SUBJECT TO RULE

12(c) DISMISSAL WITHOUT FURTHER DEVELOPMENT OF

THE RECORD

Plaintiffs allege that New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme further

violates the Equal Protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment by

impermissibly distinguishing between individuals convicted of a felony who are

sentenced to incarceration and/or serving a sentence of parole, on the one hand,

and those convicted of a felony who are pardoned, who receive a suspended or

24

commuted sentence, or who are sentenced to probation or conditional or

unconditional discharge, on the other. In his attempt to skirt any meaningful

scrutiny of New York’s non-uniform felon disfranchisement scheme, Defendant

incorrectly relies upon a portion of the panel decision in Baker v. Cuomo, which

applied a wholly deferential rational basis standard of review to a challenge to New

York’s felon disfranchisement provision by incarcerated individuals. Defendant’s

contention that the equal protection claims raised by Plaintiffs are foreclosed under

Baker fails to recognize key distinctions between the allegations in this case and

those at issue both in Baker and Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974), upon

which Defendant also relies.

In Richardson, the Supreme Court held that felon disfranchisement is not

prohibited under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Richardson did not, however, foreclose all constitutional challenges to felon

disfranchisement provisions. Nor did it, as the panel in Baker incorrectly suggests,

mandate that all challenges to disfranchisement schemes—other than those

alleging race or other suspect classifications—be reviewed under a highly

deferential rational basis standard of scrutiny. The Richardson Court rejected strict

scrutiny analysis only for a facial challenge to laws that disfranchise individuals

convicted of an infamous crime.

25

Neither the Court in Richardson nor the Second Circuit panel in Baker

addressed the Equal Protection issues raised by Plaintiffs in this case. Specifically,

neither court addressed whether states and election officials, when enacting and

implementing felon disfranchisement provisions, may disfranchise only some

individuals with felony convictions but not others—or settled the question whether

“rational basis” or “strict scrutiny” review would be applied to such a statute if

challenged. Indeed, the Richardson Court noted that it was leaving open to the

“alternative contention that there was such a total lack of uniformity in county

election officials’ enforcement of the challenged state laws as to work a separate

denial of equal protection.” Richardson. 418 U.S. at 56.

In contrast to the wholesale challenge to felon disfranchisement at issue in

Richardson, Plaintiffs here challenge specific features of New York’s felon

disfranchisement scheme: the non-uniform practice of disfranchising persons

convicted of a felony who are sentenced to incarceration and/or on parole but

allowing those who receive a suspended or commuted sentence, or are sentenced to

probation or conditional or unconditional discharge, to vote. (JA 00112-113

26

[Compl. 79; 82]).6 Richardson does not dispose of these claims or reject

application of strict scrutiny to them.

In addition and in the alternative, Plaintiffs urge the Court to apply an

intermediate level of scrutiny to their equal protection claims. As this Court

recently noted in Ramos v. Town of Vernon. 353 F.3d 171 (2d Cir. 2003),

intermediate scrutiny, which lies “between [the] extremes of rational basis review

and strict scrutiny,” 353 F.3d at 175 (quoting Clark v. Jeter. 486 U.S. 456, 461

(1988)), is appropriate to review quasi-suspect classifications such as gender or

legitimacy, as well as to review “a law that affects ‘an important, though not

constitutional, right.’” 353 F.3d at 175 (quoting United States v, Coleman. 166

F.3d 428, 431 (2d Cir. 1999) (per curiam)).

Similarly, it has long been recognized that the right to vote is “of the most

fundamental significance under our constitutional structure.” Burdick v. Takushi.

504 U.S. 428, 433 (1992) (quoting Illinois Bd. of Elections v. Socialist Workers

Party, 440 U.S. 173 (1979)); see also Reynolds v. Sims. 377 U.S. 533, 561-562

6 Furthermore, Plaintiffs have alleged that as a result of disparities in prosecution,

conviction and sentencing, Blacks and Latinos are sentenced to incarceration at

substantially higher rates than whites and sentenced to probation at substantially

lower rates than whites. (JA 00108-109 [FAC ffi[ 60-65]). Plaintiffs contend that

as a result of these racial disparities, as well as the disfranchisement of only certain

classes of individuals with felony convictions, Blacks and Latinos collectively

comprise nearly 87% of those currently denied the right to vote pursuant to §5-

106(2), (JA 00110 [FAC f 67]), which underscores the Equal Protection violation.

27

(1964); Dunn v. Blumstein. 405 U.S. 330, 336 (1972). While the Baker court

rejected strict scrutiny to protect the otherwise fundamental right to vote of felons

in cases where there was no allegation of discrimination on the basis of race or

other suspect criteria, Baker. 58 F.3d at 820, in this case, which challenges New

York’s felon disfranchisement scheme because it denies the right to vote to persons

who are convicted of a felony and sentenced to incarceration and/or parole but not

similarly situated individuals who are sentenced to probation, the court should

review Plaintiffs’ claims under a heightened, intermediate scrutiny standard.

However, even assuming, arguendo, that rational basis review applies to

Plaintiffs’ claims, Defendant nevertheless errs in arguing that Baker controls the

instant case. In Baker, this Court interpreted the plaintiffs’ Equal Protection claim

as a challenge to the way in which New York disfranchises incarcerated felons but

not those who are not incarcerated. Baker. 58 F.3d at 820. Citing Richardson v.

Ramirez to reject heightened scrutiny, and relying on its previous decision in

Green v. Bd. of Elections. 380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967), the Court applied rational

basis review and held that such a classification “is not irrational.” Id.

Unlike in Baker. Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection claim also focuses on

distinctions among individuals who live in their communities, subject to state

supervision. New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme distinguishes between

28

those individuals living in the community on parole and those on probation. (JA

00109 [FAC 58-59]). Thus, the Baker Court’s determination of the rationality

of distinctions between incarcerated felons and felons who are not incarcerated is

not controlling for purposes of disposing of Plaintiffs’ claims.

Moreover, application of rational basis scrutiny need not be wholly

deferential, particularly where the challenged distinction is based solely on the

status of the individual—here, whether he or she is convicted of a felony and

sentenced to incarceration and/or parole or sentenced to probation. Rather, in such

cases, courts may apply rational basis review in such a way as to inquire into “the

relation between the classification adopted and the object to be attained.” Romer

v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 632 (1996). While Baker held that the distinction between

incarcerated and non-incarcerated persons with felony convictions was “not

irrational,” both Baker and of Green, upon which Baker relies, were decided prior

to the Supreme Court’s decision in Romer v. Evans. 517 U.S. 620 (1996), in which

the Court applied a more searching rational basis review. Such review is

warranted here.

Thus, even if this court determines that rational basis is the appropriate level

of review, the district court still must allow Plaintiffs the opportunity to develop

evidence regarding the interests served by the voting ban and whether the

29

distinction is, in fact, rational. By dismissing Plaintiffs’ claims prematurely, the

district court denied Plaintiffs the opportunity to engage in this analysis.

V. PLAINTIFFS’ VOTING RIGHTS ACT CLAIMS SHOULD BE

PRESERVED PENDING FINAL DISPOSITION IN MUNTAOIM

The district court dismissed Plaintiffs’ Voting Rights Act claims based upon

this Court’s intervening ruling in Muntaqim v. Coombe. 366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir.

2004), which held that the Voting Rights Act does not apply to New York’s felon

disfranchisement laws. Subsequently, the plaintiff-appellant in Muntaqim filed a

petition for a writ of certiorari in the United States Supreme Court. Muntaqim v.

Coombe, 385 F.3d 793 (2d Cir. 2004), pet, for cert, filed, 73 U.S.L.W. 3113 (U.S.

July 21, 2004) (No. 04-175). Since Plaintiffs’ filed their opening brief in this

appeal and while the petition in Muntaqim was pending before the United States

Supreme Court, this Court, sua sponte, conducted a poll on whether to rehear

Muntaqim en banc. Muntaqim v. Coombe, 385 F.3d 793 (2d Cir. 2004) (denying

petition for rehearing en banc). The suggestion for rehearing did not gamer a

sufficient number of votes and, therefore, failed. Id. But see id. at 795 (Jacobs, J.,

dissenting) (“[A] majority [of this court] now expresses—or signals—an interest in

7 Although Plaintiffs disagree with the holding in Muntaqim concerning the

application of the Voting Rights Act to felon disfranchisement laws, we recognize

that it is the law of this circuit and, therefore, have appealed from the district

court’s dismissal of their Voting Rights Act claims to preserve the issue and seek

the limited relief described below.

30

hearing this appeal in banc.”). The petition for certiorari in Muntaqim was

subsequently denied and the plaintiff-appellant then petitioned this Court for a

rehearing en banc. See Pet. for Reh’g En Banc, in Muntaqim v. Coombe. 366 F.3d

102 (2d Cir. 2004) (No. 01-7260) filed Nov. 16, 2004.

The disposition of the pending petition in Muntaqim will have a direct

bearing on Plaintiffs’ Voting Rights Act claims. Accordingly, Plaintiffs request

that this Court vacate the judgment below, with instructions to the district court to

reconsider its dismissal in light of any action taken by this court in Muntaqim.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the district court should be

reversed in part, vacated in part, and the case remanded for further proceedings.

Dated: New York, New York

December 8, 2004

. Nelson

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Ryan P. Haygood

Debo P. Adegbile

Alaina C. Beverly

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013-2897

31

(Tel.) 212-965-2200

(Fax) 212-226-7592

inelson@naacpldf.org

Juan Cartagena

Risa E. Kaufman

Community Service Society

of New York

105 E. 22nd Street

New York, NY 10010

(Tel.) 212-614-5462

(Fax) 212-260-6218

icartagena@cssnv.org

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, NY 11225

(Tel.) 718- 270-6296

(Fax) 718-270-6190

ioangibbs@hotmail.com

32

mailto:inelson@naacpldf.org

mailto:icartagena@cssnv.org

mailto:ioangibbs@hotmail.com

RULE 32(a)(7)(B)(ii) CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

The undersigned hereby certifies that this brief complies with the type-

volume limitations of Rule 32(a)(7)(B)(ii) of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure. Relying on the word count of the word processing system used to

prepare this brief, I hereby represent that the brief of the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York, and the

Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College for Plaintiffs-

Appellants contains 6,963 words, not including the table of contents, table of

authorities, and certificate of counsel, and is therefore within the word limit for

7,000 set forth under Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B)(ii).

Director of Political Participation

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

inelson@naacpldf.org

Dated: December 8, 2004

mailto:inelson@naacpldf.org

CERTFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify under penalty of perjury pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746 that on

December 8, 2004, I served upon the following, by United States Postal Service

priority mail, postage prepaid, a true and correct copy of the attached REPLY

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS:

Eliot Spitzer

Attorney General of New York

Michelle Aronowitz

Deputy Solicitor General

Gregory Klass

Assistant Solicitor General

120 Broadway - 24th Floor

New York, New York 10271-0332

Counsel for Defendant Governor

George Pataki

Patricia L. Murray

First Deputy Counsel

New York State Board of Elections

40 Steuben Street

Albany, New York 12207-0332

Counsel for Defendant Carol Berman

by depositing it securely enclosed in a properly addressed wrapper into the custody

of the United States Postal Service for priority mail delivery, prior to the latest time

designated by that service.

Director of Political Participation

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

inelson @ naacpldf.org