Green v. Estelle Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

Public Court Documents

October 19, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. Estelle Brief for Petitioner-Appellant, 1982. 9fbb803f-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19bd80ff-1963-48ec-9dc1-82674e1091d6/green-v-estelle-brief-for-petitioner-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

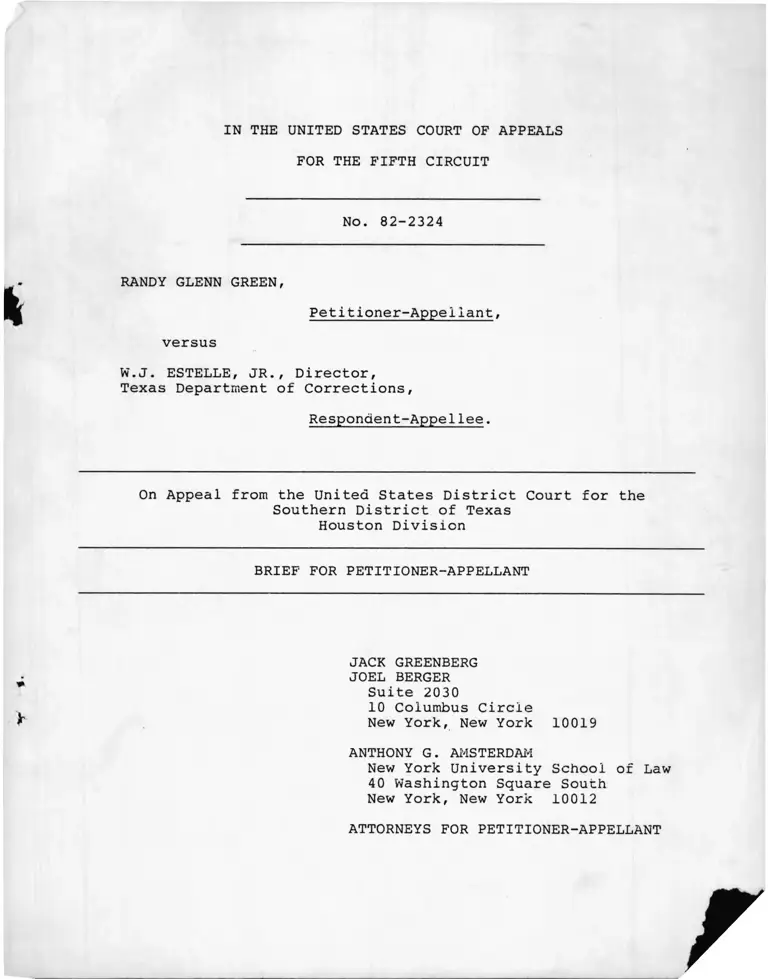

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 82-2324

RANDY GLENN GREEN,

Petitioner-Appellant,

versus

W.J. ESTELLE, JR., Director,

Texas Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Texas

Houston Division

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

JACK GREENBERG

JOEL BERGER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University School of Law

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Pursuant to Rule 13.6.4 of the Rules of this Court, petitioner-

appellant requests oral argument of this appeal.

This is an appeal from the denial of a habeas corpus petition

in a death case. The District Court below found that petitioner's

Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights under Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S.

454 (1982), had been violated by the prosecution's use of the

results of a routine pretrial competency and sanity evaluation at

the penalty phase of petitioner's trial, but nonetheless denied

relief on grounds of procedural forfeiture. Petitioner believes

that under the facts and circumstances of this case, considered in

light of the applicable decisions of the Supreme Court, this Court

and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, no procedural forfeiture

may be imposed.

The resolution of this issue is obviously of the utmost im

portance to Mr. Green, as his very life depends upon it. Accordingly,

petitioner respectfully requests oral argument.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION .................................. 1

ISSUE PRESENTED .............................. 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................... 3

COURSE OF PRIOR PROCEEDINGS .......................... 3

STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................. 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 20

ARGUMENT ................................................... 21

PETITIONER'S OBVIOUSLY VALID CLAIM UNDER

ESTELLE V. SMITH, 451 U.S. 454 (1981),

MAY NOT BE REJECTED ON GROUNDS OF

PROCEDURAL FORFEITURE ................ 21

CONCLUSION .....................................;........... 34

- ii -

TABLE OF CITATIONS

CASES PAGE

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38 ( 1980) .......................... 30

Anderson v. State, 381 So. 2d 1019 (1980) ................... 23

Armstrong v. State, 502 S.W.2d 731 (Tex. Crim. App. 1973) .... 29

Barr v. State, 359 So. 2d 334 (1978) ............ ............ 23

Battie v. Estelle, 655 F . 2d 692 ( 5th Cir. 1931) ............. 32

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980) ........................ 30,32,33

Bell v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 637 (1978) ........................... 30

Brandon v. State, ___ S.W.2d ___, No. 59,348 (Tex. Crim.

App. June 2, 1982) .................................... 20,25,26

Braxton v. Estelle, 641 F.2d 392 ( 5th Cir. 1981) ............ 26

Bullington v. Missouri, 451 U.S. 430 (1981) ................. 30

Burns v. Estelle, 592 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1979), adhered to en

banc, 626 F. 2d 396 (5th Cir. 1980) ..................... 26

Cessna v. State, 381 So. 2d 173 (1980) ...................... 23

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967) ................... 27

Clark v. State, 627 S.W.2d 693 (Tex. Crim. App. 1981) ....... 24

Collins v. State, 361 So. 2d 333 ( 1978) ...................... 23

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1976) ........................ 30

Eddings v. Oklahoma, ___ U.S. ___, 71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982) ...... 30,33

Engle v. Isaac, ___ U.S. ___, 71 L.Ed.2d 783 (1982) ......... 29,30

Enmund v. Florida, __ U.S. ___, 73 L.Ed.2d 1140 (1982) ...... 30

Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981) passim

Ex Parte Demouchette, 633 S.W.2d 879 (Tex. Crim. App. 1982) .. 26

Ex Parte English, __ S.W.2d ___ No. 68,953 (Tex. Crim. App.

Sept. 15, 1982) ......................................... 26

- iii -

CASES PAGE

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977) ................... 30,32,33

Gator v. State, 402 So. 2d 316 (1981) .................. 23

Gholson v. Estelle, 675 F . 2d 734 (5th Cir. 1982) ............ 32,33

Gholson v. State, 542 S.W.2d 395 (Tex. Crim. App. 1976) ___ 29

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420 (1980) .................... 30

Gray v. State, 375 So. 2d 994 (1979) ........................ 23

Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (1979) ....................... 30

Green v. State, 587 S.W.2d 167 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979) ....... 3,17

Harrison v. United States, 392 U.S. 219 (1968) ............ 24

Henry v. Wainwright, ___ F.2d ___, No. 80-5184 (5th Cir.

Sept. 20, 1982) ....................................... 26,27

Hollins v. State, 340 So. 2d 438 (1976) ......... .......... 23

Huffman v. Wainwright, 651 F.2d 347 (5th Cir. 1981) ....... 27

Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682 (1972) .................... 23

Livingston v. State, 542 S.W.2d 655 (Tex. Crim. App. 1976) . 29

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 ( 1978) ........... ........... 30,32

May v. State, 398 So. 2d 1331 (1981) ...................... 23

Miller v. Estelle, 677 F.2d 1080 (5th Cir. 1982) .......... 26

Moore v. Illinois, 434 U.S. 220 (1977) .................... 23

Moran v. Estelle, 607 F.2d 1140 (5th Cir. 1979) ............ 26

Presnell v. Georgia, 439 U.S. 14 (1978) .............. . 30

H. Roberts v. Louisiana, 431 U.S. 633 (1977) ............. 30

S. Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976) ........... 30

Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218 ( 1973) ............ 30

IV

CASES PAGE

Shippy v. State, 556 S.W.2d 246 (Tex. Crim. App. 1977) ..... 29

Smith v. Estelle, 602 F.2d 694 (5th Cir. 1979) ............. 21,28,30,

31,32

Spivey v. Zant, 661 F.2d 464 ( 5th Cir. 1981) ............ . 24

Thompson v. Estelle, 642 F.2d 996 (5th Cir. .1981) .......... 26

Thompson v. State, 621 S.W.2d 624 (Tex. Crim. App. 1981) .... 29

Von Byrd v. State, 569 S.W.2d 883 (Tex. Crim. App. 1978) .... 29

Wilder v. State, 583 S.W.2d 349 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979) ..... 29

Williamson v. State, 330 So. 2d 272 (1976) ....... -.......... 23

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) ............. 30,32

STATUTES

Tex. Code Crim. Pro. Art. 37.01 ............................. 4

28 U.S.C. §2253 .................. .......................... 1

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 82-2324

RANDY GLENN GREEN,

Petitioner-Appellant,

versus

W.J. ESTELLE, JR., Director,

Texas Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Texas

Houston Division

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The Court's jurisdiction to hear this appeal from the denial of

habeas corpus relief in the District Court rests upon 28 U.S.C.

§2253. The requisite certificate of probable cause was granted by

the District Court on August 3, 1982 (R. 2).~

1/ Numbers preceded by "R." refer to pages of the Record on Appeal

to this Court.

ISSUE PRESENTED

Whether petitioner's obviously valid claim under Estelle v.

Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981), may be rejected on grounds of pro

cedural forfeiture.

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

COURSE OF PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On November 14, 1977, at a jury trial in the 178th Judicial

District Court of Harris County, Texas, petitioner was convicted of

capital murder. On November 18, 1977, the jury answered "yes" to

the special issues determinative of sentence in Texas capital cases,

and petitioner was sentenced to die. The Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals affirmed petitioner's conviction and death sentence on

October 3, 1979. Green v. State, 587 S.W.2d 167. Certiorari was

denied on June 29, 1981. 453 U.S. 913.

On October 20, 1981, petitioner filed a petition for a writ of

habeas corpus in the 178th Judicial District Court of Harris County,

Texas. The following day that court certified that in its view

there were no issues of fact requiring an evidentiary hearing, and

transmitted the matter to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. On

October 26, 1981, the Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas corpus

relief.

The instant federal habeas corpus petition, raising issues

identical to those contained in the state habeas corpus proceeding,

was filed on October 26, 1981. By Memorandum and Order filed June

15, 1982, the District Court (Hon. Robert J. O'Conor, Jr.) denied

relief (R. 43-56). Rehearing was denied on July 6, 1982 (R. 25).

On August 3, 1982, the District Court granted a certificate of

probable cause to appeal and leave to appeal in forma pauperis (R.

2), and stayed petitioner's execution pending appeal (R. 1).

3

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Petitioner was convicted and sentenced to die for the murder of

a Baytown, Texas tavern owner. The victim died of injuries sustained

when he was beaten in the course of a robbery of his tavern on the

night of June 28, 1976.

Immediately following petitioner's conviction on November 14,

1977, a penalty trial was conducted before the same jury pursuant to

„ . 2/Tex. Code Crim. Pro. Art. 37.071.“ At the outset of this proceeding

the prosecution established that on November 5, 1976, petitioner had

pleaded guilty to the murder of a woman in Mississippi and had been

3/sentenced to life imprisonment (SF 2959-66).“ The Mississippi

offense was committed in Yazoo City, petitioner's home town, approxi

mately one month after the Baytown, Texas offense (SF 2963). The

penitentiary packet introduced by the prosecution as proof of the

2/ In this proceeding, the State had the burden of proving beyond a

reasonable doubt that the answer to each of the following questions was "yes":

(1) whether the conduct of the defendant that

caused the death of the deceased was com

mitted deliberately and with the reason

able expectation that the death of the de

ceased or another would result;

(2) whether there is a probability that

the defendant would commit; criminal acts

of violence that would constitute a conti

nuing threat to society.

A "yes" answer to both questions results in a mandatory death sentence.

3/ Numbers preceded by "SF" refer to pages of the statement of

facts of the state trial court record in this case. Page references

are to numbers stamped in the lower left hand corner of each page.

4

Mississippi conviction reflects that petitioner had no criminal

record prior to the Mississippi offense. (State's Exhibit 121,

second page, admitted into evidence at SF 2966, reproduced in the

record at SF 3419.)

Other than the Mississippi offense, the State's entire case at

the penalty phase consisted of the testimony of Dr. Donald C. Guild,

a psychiatrist (SF 2990-3029), and Dr. Charlton S. Stanley, a psy

chologist (SF 3030-3114). These two doctors, employees of a

Mississippi state mental hospital (SF 2994, 3059-60), had interviewed

petitioner at that hospital pursuant to the order of a Mississippi

court requesting an evaluation of petitioner's competency to stand

trial in the Mississippi case and his sanity at the time of that

offense (SF 3086-89, 3105, 3422). The interviews took place between

August 30, 1976 and October 14, 1976, the period of petitioner's

confinement in the hospital (SF 3033). At this time petitioner was

already under indictment in the Baytown, Texas case, the indictment

4/having been filed on August 11, 1976 (SF 6).-

Pstitioner has alleged in the instant habeas corpus proceeding,

and the State has not denied, that prior to the interviews Doctors

Guild and Stanley did not advise petitioner that he had a right to

4/ Petitioner was arrested in Yazoo City, Mississippi on August 1,

1976 (SF 2982, 2984), and charged with the Mississippi offense

shortly thereafter. Detectives from Baytown, Texas arrived in Yazoo

City on August 3, 1976, and obtained a statement from petitioner

that evening (SF 2686, 2715, 2750). A felony complaint in the

Baytown case was filed on August 3, 1976 (SF 5, 124, 2785), and the

indictment was returned eight days later (SF 6). However, petitioner

apparently was not released to Texas authorities until after disposition

of the Mississippi case in November 1976. His first recorded appea

rance in a Texas court on the Baytown case took place on March 4,

1977 (SF 124-25); the first recorded appearance of counsel in the case also occurred on that date (ibid.).

5

remain silent, that anything he said to the doctors might be used

against him at the penalty phase of a capital trial, and that he had

a right to consult with counsel before submitting to the interviews

5/(R. 157-58, 98, 86-87, 77).“

Dr. Guild testified that he interviewed petitioner on at least

four occasions during petitioner's confinement in the hospital (SF

3005), that petitioner was "cooperative" with him (SF 3018), and

that he asked petitioner "questions that would be pertinent to a

courtroom about incidents that occurred" including questions about

"the facts of the crime in Mississippi" (SF 2993, 3028). The doctor

concluded that petitioner has an "anti-social personality" (SF 3007,

3022), a diagnosis which he defined as follows:

anti-social personality is a person who again

comes in repeated contact with the law, has dif

ficulty with having morals, allegiance or al

liance with any group or organization, a per

son who sort of doesn't have a conscience in

the usual sense that we think of a conscience

to sort of tell us what's right and wrong, a

sense of values, religious principals, ethics,

scruples, ... people who more or less operate on a day-to-day basis, more self-centered....

... they generally look out for themselves quite

a bit more than the average person does.

(SF 3008).

5/ The State's Motion to Dismiss and Answer, while never alleging

affirmatively that petitioner received such warnings, stated that

Dr. Stanley had testified that "he was conscious of the Fifth Amend

ment" and that "there was an attorney present during his interview

with petitioner" (R. 98). Reference to Dr. Stanley's testimony

establishes that the attorney in question was from the State Board

of Mental Health, sent to provide legal guidance to the hospital

staff (SF 3049), and that at no time did Dr. Stanley claim to have

administered any Fifth or Sixth Amendment warnings to petitioner

(ibid). The State did not claim in opposition to petitioner's

motion for summary judgment that any such warnings were given (R.

77, 79); and the District Court found no evidence in the record that

petitioner received such warnings (R. 46).

6

Dr. Guild testified, based upon "what I know from my evaluation

personally" (SF 3011) together with the prosecutor's description of

the Baytown, Texas offense, that petitioner had committed the of

fense deliberately (ibid.) and that "there's just no reason to believe

that acts like this or similar or violent acts are not going to

6/happen again" (SF 3012). The doctor further stated that peti

tioner "did not display remorse or guilt as most people would expect

[of] a normal person.... [T]his is tantamount to an anti-social

personality" (SF 3019).

Doctor Stanley, the psychologist, testified that he interviewed

petitioner personally and evaluated a series of psychological tests

administered to petitioner under the doctor's "direct and personal

supervision" (SF 3032, 3033). Petitioner resisted the examination

at first, but later became cooperative after being told by the

examiner administering the tests that his resistance "wouldn't get

him anywhere" (SF 3035).

The doctor concluded, based upon his evaluation of the tests,

that petitioner is "an unquestionably dangerous man" (SF 3048). He

diagnosed petitioner as "an anti-social or psychopathic personality

with some traits of a paranoid personality.... He is in no way

psychotic" (ibid.).

6/ Defense counsel objected to this testimony, stating as follows:

"In the first place, that's a matter for the jury to determine. In

the second place, the question fails to include all of the facts as

shown by the evidence. Furthermore, he didn't ask the doctor his

opinion based on reasonable medical certainty. He didn't take into

consideration that Randy Green had been drinking beer all day and

there at the lounge. He left that out and that's material, Your

Honor" (SF 3012). The objection was overruled (ibid.).

7

Dr. Stanley elaborated upon his findings in far greater detail

than Dr. Guild. He found petitioner to be "relatively free of the

constraints on his actions that we normally call conscience" (SF

3036). He accused petitioner of being "a profoundly oppositional

and negativistic person" (SF 3038) with "tremendous hostility"

(SF 3039). "He generally does not act out in blind and helpless

rage, but rather any aggressive acting out would be the result of

deliberate actions on his part" (SF 3039). Dr. Stanley believed

that petitioner "seems unwilling or unable to accept personal re

sponsibility for those things in his life that he regards as per

sonal failures" (SF 3040), and that "[pjersons like this do not

learn from their experiences that they cannot engage in bad behavior

and avoid punishment. It will always be that it was someone else's

fault" (SF 3041).

Dr. Stanley testified that one of the tests showed "a typical

anti-social personality pattern" (SF 3043), which he defined as a

person who

doesn't have the usual controls on their beha

vior that most of us do. They aren't bothered

by what other people's feelings might be. The

attitude of the anti-social personality or psycho

path is that it's me first and to hell with the rest.

(SF 3043). He stated that if petitioner "couldn't get anything

fairly quickly by being nice" to people, he would "probably get ugly

with them" and have "no pity for them" (SF 3044). He reported that

on one of the tests petitioner "frankly admitted to having committed

a murder ... when he was asked about it" (SF 3047), and that on

another test petitioner had answered "true" to the question "[some

times I feel I must injure either myself or others" (SF 3046). The

8

psychologist concluded that petitioner "is shown to be immature, is

hostile, is aggressive, and perfectly in control of his thinking"

(SF 3048), and is a dangerous anti-social or psychopathic personality

(ibid.).

At this point in Dr. Stanley's testimony, the prosecutor elicited

a rendition of specific statements made by petitioner to the doctor

concerning the Mississippi offense (SF 3050-52). Defense counsel

objected and moved

to strike ail this testimony out in view of the

fact that this was a confidential relationship

between a patient and his psychologist, and this

defendant was sent to the hospital under a Court

order, and this is nothing more than a viola

tion of the Fifth Amendment of the [C]onstitution,

telling this defendant to testify against him

self, and this came in the nature of a confi

dential consultation, and we move to strike all

of this testimony and ask the Court to instruct

the jury to disregard it.

(SF 3052)(emphasis added). The prosecutor then offered the following:

"If the Court would strike from the record at the point where he

started going into the details [of the Mississippi offense], I will

withdraw my question at that point and go on to something else" (SF

3053). However, defense counsel did not accept this offer and stated

that "[w]e again renew our motion to instruct the jury to disregard

all the testimony from the witness" (SF 3053), stressing that peti

tioner's communications with a doctor conducting an examination

pursuant to court order were confidential (SF 3053-54). The trial

court overruled the objection (SF 3054), instructing the jury only

that "the State has withdrawn the last question asked of the witness

as to responses of the defendant and any other question asked by this

witness of the defendant concerning his actions as to any other

9

offense. Those matters are all withdrawn from your consideration

and are not to be considered by the jury for any purpose whatsoever

in arriving at your verdict" (SF 3054-55).

Dr. Stanley then testified that "[b]asea on the psychological

report and in reviewing the record in its totality, ... I do not see

any hope of change in Mr. Green's behavior" (SF 3055), and that

"[r]ehabilitation of a person with this particular personality pat

tern is not reported in the scientific literature, to my knowl

edge.... I have looked but I have never come across it" (ibid.).

He concluded, based upon his evaluation of petitioner together with

the prosecutor's description of the Baytown, Texas offense (SF 3056-

58), that petitioner "knew exactly what he was doing" when he com

mitted the offense and that "he understood the nature and conse

quences of his acts at that moment in time. It's my opinion that he

could tell the difference between right and wrong and could have

followed the right had he so chosen" (SF 3058). The doctor further

testified, again on the basis of both his evaluation and the facts

of the crime (SF 3058), that "[t]he probability is overwhelming that

such acts could be expected in the future" (SF 3059).

On cross examination, defense counsel asked Dr. Stanley whether

petitioner could conform his conduct to rules and regulations in a

structured environment (SF 3082-83). The psychologist responded

that "if ... we could get one of the tackles from the Astros [sic]

to stand at his elbow, he could conform I think but I don't see that

as very likely" (SF 3083). Defense counsel then confronted the

doctor with Dr. Guild's case notes, introduced in evidence as De

fendant's Exhibit 3 (SF 3094), reflecting that "[d]uring his course

10

in the hospital, Mr. Randy Green has been quiet and well behaved at

all times and caused no difficulty to anyone. He has associated

with other patients and interacted quite well causing no difficulty

and demonstrating an ability to interact with others in a structured

environment quite well" (SF 3090, 3423). Dr. Stanley at first tried

to explain this statement by claiming that his hospital has superior

security arrangements (SF 3091-93), but ultimately conceded that he

agreed with Dr. Guild's position (SF 3094, 3097). He added, how

ever, that while petitioner had conformed well during his six weeks

at the hospital, "I don't know what he. would do over a seven-week

period, eight-week period, a year, I don't know" (SF 3097).

When asked on re-direct whether petitioner would be a threat to

persons smaller than him in prison, Dr. Stanley replied that "based

on primarily my psychological tests and the history I have been

given, which we all know contains episodes of violent acting out

when he's annoyed or frustrated, I would think that other prisoners

would have reason to have some concern for their welfare" (SF 3107-

OS) .

* * * *

The defense at the penalty trial called petitioner's wife,

mother, father, aunt, former common-law wife, and former common-law

wife's sister, all of whom testified that petitioner had suffered

from chronic alcoholism for the past several years. Several of

these witnesses also testified that petitioner had been drinking

very heavily on the day of the Baytown offense.

Mrs. Sharon Ann Green, petitioner's wife, testified that on the

day in question petitioner consumed twelve bottles of beer and a

11

fifth of Seagrams V-0 whisky before noon (SF 3120-25, 3133). He

left the house at noon and returned around 3-4 P.M., at which time

7/he drank another fifth of whisky (SF 3126, 3134). Mrs. Green

testified that petitioner had been drinking at this pace (between a

fifth and a half-gallon of whisky per day) nearly every day from the

date of their marriage on October 23, 1975 to the date of the Baytown

offense on June 28, 1976 (SF 3127-29, 3134-35, 3138). The couple

had lived together during this entire period except for a one month

separation (SF 3132, 3135). Mrs. Green stated that petitioner rarely

ate food, because "most of the time he was drinking so he didn't

eat" (SF 3138).

Mrs. Jeanne Parnell, the sister of petitioner's former common-

law wife, corroborated Mrs. Green's testimony concerning the extent

of petitioner's consumption of alcohol on the date of the offense

(SF 3181-82), and added that she had given petitioner approximately

8/six additional beers at her house on that date (SF 3287). Mrs.

Parnell had seen petitioner several times on that date, and every

time she saw him he had been intoxicated (SF 3283-84, 3287-88).

During her three months of being a neighbor of Mr. Green in Baytown,

she had seen petitioner every day (SF 3280); on each occasion peti

tioner "was drinking from the time he got up until the time he went

to bed" (SF 3283) .

Ms. Haroline Hester, petitioner's former common-law wife, had

lived with him in Baytown during the period of his brief separation

7/ At the guilt trial, a prosecution witness testified that peti

tioner additionally consumed between three and six beers just before

and during commission of the offense that night (SF 2554-55).

8/ Petitioner and Mrs. Green lived in a garage apartment 30 feet

behind the house in which Mrs. Parnell resided with her husband in

Baytown (SF 3280).

12

from Mrs. Green; they were together until only three weeks before

the date of the offense (SF 3162). Ms. Hester corroborated the

testimony of Mrs. Green and Mrs. Parnell as to petitioner's chronic

drinking, stating that he had consumed one to two fifths of liquor

every day during this period and was drunk each day (ibid.). She

added that petitioner had also been drinking to this extent when she

lived with him in Yazoo City, Mississippi in 1974 (SF 3162-64).

Mrs. Gloria Hearne, petitioner's aunt, testified that she had

known him for 18 years and had become very close with him after

moving to Yazoo City in 1971 (SF 3268-69); they lived only a mile

apart, and visited each other frequently (SF 3770). Mrs. Hearne

stated that petitioner began drinking heavily after Christmas of

1973, when he went through a divorce from his first wife (SF 3270).

From then on he would drink over a fifth of hard alcohol every day

in the afternoon and evening, as well as beer (SF 3270-71). When

drunk, petitioner would "fly off the handle very easily over very

minor things" (SF 3272). However, when not drinking he was "a very

congenial and lovable person" (SF 3271).

Petitioner's mother and father similarly testified to petitioner's

heavy drinking (SF 3159, 3276-77). Mr. James Green, the father,

agreed with Mrs. Hearne that the drinking began after petitioner's

separation from his first wife (SF 3276). Mr. Green stated that

when petitioner was drinking he'd be "quick-tempered" and "high

strung," and it would take "just a very little to upset him" (SF

3277); but "[w]hen he's sober, he's friendly, a gentleman" (ibid.).

Defense testimony at the penalty phase established that petitioner

has two boys from his first marriage, ages 5 and 4, and that both

13

have been adopted by petitioner's parents (SF 3144-45). He also has

a boy, age 3, from his relationship with Haroline Hester; the boy

lives with Ms. Hester in Yazoo City, and petitioner contributes

support for him (SF 3144-45, 3161, 3164). In addition, petitioner

has a two year old boy and a one year old girl from his present

marriage; both live with Mrs. Green in Yazoo City, and petitioner

has helped support them (SF 3131).

To refute the testimony of Doctors Guild and Stanley, the

defense called two psychologists. One of these psychologists, Dr.

David Gerard Ross Pascal, had examined petitioner at age 13 when

petitioner had developed emotional problems as a child (SF 3155-56,

3178-80); after this 3-hour interview in 1968, Dr. Pascal had not

seen petitioner again except for a brief conversation just prior to

his testimony (SF 3184-85, 3196). Dr. Pascal testified that exces

sive consumption of alcohol had triggered petitioner's commission of

the Baytown offense (SF 3189), and that petitioner had not acted

deliberately (SF 3193). He further stated that if petitioner were

to be confined in a structured environment and denied access to

alcoholic beverages, petitioner would not be prone to commit cri

minal acts of violence in the future (SF 3190-91, 3195). Dr. Pascal

disagreed with the diagnosis of Doctors Guild and Stanley, stating

that "I wouldn't call Randy a sociopath" (SF 3198).

Dr. Richard G. Jones, also called by the defense, had inter

viewed petitioner the month before trial and had administered a

series of psychological tests (SF 3217-18, 3243-44). Dr. Jones

concluded that petitioner had not acted deliberately at the time of

the offense because he had been in a severe state of intoxication

(SF 3228-32). The doctor further believed that the probability of

14

petitioner committing future criminal acts of violence would be

"minimal" if he were to be denied the use of alcohol (SF 3239-40),

that petitioner's alcoholism could be cured in prison (SF 3240-41)

and that petitioner would behave properly in a structured, institu

tional environment (SF 3242). Dr. Jones tentatively diagnosed pet

tioner as an "explosive personality" (SF 3237), a person whose

"general behavior is mild in manner and appropriate" (SF 3241) but

who tends to lose control under conditions of extreme fatigue or

extreme frustration and especially under conditions of extreme

intoxication (SF 3239). The doctor explained that "explosive per

sonality" is a recognized diagnostic term (SF 3237). He disagreed

with the diagnosis of Doctors Guild and Stanley, stating that peti

tioner is not a sociopath because his conduct is not sufficiently

calculated to fit within that diagnosis:

He does have some behavioral characteristics

that fit the anti-social personality, but the

thing that strikes me about his history is the

tendency, even from very early years, of being

erratic, unpredictable, changeable, very, very

nice guy, easy to get along with, happy one

moment and then blowing up, firing up, getting

angry, getting into fights at school, or com

mitting some impulsive act. Now from a diag

nostic viewpoint, this particular type of per

sonality structure is described as an explosive

personality.

(SF 3237) .

* * * *

During summation at the penalty phase, the prosecutors relied

extensively upon the testimony of Doctors Guild and Stanley:

[T]he doctors have told you [he] is an antisocial personality, has no feelings of guilt, has no remorse, cannot be rehabilitated, that

15

he's going to do it again whether it's in pri

son — remember the doctor [Stanley] said the

other prisoners in that society would be in

danger.... The only person that he won't kill

is someone bigger than he is...

(SF 3320) ;

He has no feelings. They [the doctors] told

you that. He has no mercy. He has no compas

sion. He has no remorse. He has no guilt,

and ... he will do it again.

(SF 3321);

Dr. Guild and Dr. Stanley had this man under

hospital testing for six weeks. They studied

him. They ran every test they know about,

mental, physical, neurological, and Dr. Guild

and Dr. Stanley came back and told you based

on their tests ... that Randy Green, in the

words of Dr. Guild, [is] a firecracker, a man

who has no conscience, who is anti-social, a

sociopath, has no feelings at all ...

(SF 3328);

Dr. Guild and Dr. Stanley had no doubt. They

told you. They told you that although he uses

alcohol, that alcohol is not what made Randy

Glenn Green do these acts, that Randy Glenn

Green is the sort of person who is careful about

his acts, he is the sort of person who is deli

berate about his acts.... Also they told you

that Randy Green can't learn from experience.

Remember Dr. Stanley telling you that he has

done extensive research into the sort of psycho

logical make-up that this man has, and through

out ail his research and all his reading, there

is not one reported case of any rehabilitation

of a person like Randy Glenn Green. It can't

be done with his sort of person ... [W]e asked

the two doctors is there a probability that

this defendant would commit criminal acts of

violence which would constitute a continuing

threat to society. Dr. Guild told you there was

definitely a probability and Dr. Stanley told

you there was an overwhelming probability.

(SF 3329) ;

16

... Dr. Guild and Dr. Stanley spent so long

and were so careful and did so many tests, so

they could come in and say positively in their

opinion based on scientific evidence.

(SF 3330) .

The jury, after deliberating for a total of 7 hours and 15

minutes (SF 137), answered the special sentencing issues "yes" and

petitioner was sentenced to die (SF 94, 101, 114).

* * ★ *

On appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, petitioner

was represented by Kenneth R. Valka, one of his trial attorneys, by

appointment of the trial court (SF 120). Mr. Valka did not argue on

appeal that the introduction of the testimony of Doctors Guild and

Stanley at the penalty phase violated petitioner's rights under the

Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

On October 3, 1979, the Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed petitioner's

conviction and death sentence. Green v. State, 587 S.W.2d 167 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1979) .

After the decision of the Court of Criminal Appeals, Mr. Valka

declined to continue representing petitioner. On certiorari peti

tioner was represented by Charles W. Mealin, a volunteer attorney.

Mr. Medlin's certiorari petition, filed 44 days out-of-time, did not

challenge the admissibility of the testimony of Doctors Guild and

Stanley on Fifth and Sixth Amendment grounds. Certiorari was denied

on June 29, 1981. 453 U.S. 913.

Subsequent to the denial of certiorari, the state trial court

set an execution date of October 28, 1981. On October 20, 1981, Mr.

Mediin filed a state habeas corpus petition alleging, inter alia,

17

that the doctors' testimony violated petitioner's Fifth and Sixth

Amendment rights (R. 157-58, 160-63). The petition further alleged

that petitioner's Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of

counsel had been violated by several derelictions of duty by his

former attorneys (R. 158-59, 165-66). On October 21, 1981, the day

after the petition was filed, the state trial judge certified that

in his view there were no issues of fact requiring an evidentiary

hearing. Five days later, on October 26, 1981, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals denied habeas corpus relief. Later that same day

Mr. Medlin filed a federal habeas corpus petition, raising issues

identical to those advanced in the state petition, and the District

Court granted a stay of execution (R. 151).

The District Court's order staying petitioner's execution

scheduled a hearing for January 4, 1982 (R. 151). The hearing was

subsequently rescheduled for April 5, 1982 (R. 115). However, on

March 22, 1982, Mr. Medlin filed a motion for summary judgment in

which he contended that no genuine issues of fact existed as to any

of the claims raised in the habeas corpus petition and that petitioner

was entitled to judgment as a matter of law (R. 86-92). The motion

contended that as to the issue challenging the admissibility of the

testimony of Doctors Guild and Stanley on Fifth and Sixth Amendment

grounds, petitioner was entitled to relief under the recent decision

of the Supreme Court of the United States in Estelle v. Smith, 451

U.S. 454 (1981) (R. 86-87). The State's response to the motion

argued that summary judgment was inappropriate on both the Estelle

v. Smith and ineffective assistance of counsel issues (R. 77, 81).

18

On June 15, 1982, the District Court issued a Memorandum and

Order denying habeas corpus relief (R. 43-56). The Court stated at

the outset that "[b]y agreement of the parties," the petition would

be decided on cross-motions for summary judgment (R. 43). The Court

agreed with petitioner's contention that the testimony of the State's

doctors had violated petitioner's Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights

(R. 44-46), but held that trial counsel's failure to interpose a

contemporaneous objection precluded the granting of federal habeas

corpus relief (R. 46-50). The Court further held that petitioner

had not been denied the effective assistance of counsel (R. 52-54).

In support of a petition for rehearing, Mr. Medlin filed a

statement confessing that he "did not realize that the record alone

... would be insufficient to support a finding ... of ineffective

assistance of counsel" (R. 28). Mr. Medlin relied upon numerous

decisions of this Court, not previously cited by him, holding that a

federal habeas corpus petitioner has a right to a hearing on a claim

of ineffective assistance of counsel (R. 28). Mr. Medlin stated

that, "[i]n light of current counsel of record's failure to cor

rectly perceive this issue, he feels that other counsel would better

represent RANDY GLENN GREEN" (ibid.). He urged that rehearing be

granted to allow new counsel to pursue the issue of ineffective

assistance at an evidentiary hearing (R. 29).

On July 6, 1982, the District Court denied rehearing without

opinion (R. 25). On August 3, 1982, the Court granted a certificate

of probable cause and leave to appeal in forma pauperis (R. 2), and

stayed petitioner's execution during the pendency of the appeal (R.

1) .

19

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Petitioner's Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights under Estelle v.

Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981), were violated when Doctors Guild and

Stanley testified for the prosecution at the penalty phase, on the

basis of pretrial interviews they conducted with petitioner without

first advising him that he had a right to remain silent, that any

thing he said might be used against him at the penalty phase of a

capital trial, and that he had a right to consult with counsel be

fore submitting to the interviews.

The District Court erred in rejecting petitioner's Smith claim

on grounds of procedural default, because 1) under Brandon v. State,

___ S.w.2d ___, No. 59,348 (Tex. Crim. App. June 2, 1982), Texas has

no "contemporaneous objection" rule with respect to Smith error; 2)

defense counsel did preserve a Fifth Amendment objection to all of

Dr. Stanley's testimony; and 3) to execute petitioner despite vio

lation of the fundamental rights declared in Smith, and despite the

fact that a successful objection at trial was totally foreclosed by

repeated decisions of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, would

result in a manifest injustice.

20

ARGUMENT

PETITIONER'S OBVIOUSLY VALID CLAIM UNDER

ESTELLE V. SMITH, 451 U.S. 454 (1981),

MAY NOT BE REJECTED ON GROUNDS OF

PROCEDURAL FORFEITURE

I

In Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981), the Supreme Court of

the United States dealt with a Texas prosecutor's use of the very

same sort of psychiatric testimony employed in this case to secure a

'sentence of death. Ernest Benjamin Smith, Jr., had submitted to a

routine pretrial competency evaluation by a psychiatrist without

being first warned by the doctor that his statements could form the

basis of testimony to be used against him at the penalty phase, or

that he had a right to remain silent. Also, as in this case, Smith

had been deprived of the opportunity to have the advice of counsel

in determining whether or not to submit to such an interview, even

though he was under indictment at the time the doctor conducted the

examination. A unanimous Supreme Court, affirming this Court's

decision in Smith v. Estelle, 602 F.2d 694 (5th Cir. 1979), held

that the use of psychiatric testimony obtained in this manner vio

lated Smith's rights under the Constitution of the United States.

The Supreme Court's opinion in Smith, written in exceedingly

blunt and uncompromising judicial language, squarely condemned the

Texas practice of utilizing the accused's unwarned and uncounseled

interviews with psychiatrists to meet the State's burden of proof at

the penalty phase of capital trials. Those words of condemnation

21

bear repeating here, because they describe equally well what the

State of Texas did to Randy Glenn Green in this case and why it was

so fundamentally unjust. Here, as in Smith, Mr. Green was made the

"'deluded instrument' of his own execution." 451 U.S. at 462. His

responses to the questions of Doctors Guild and Stanley, "unwittingly

made without an awareness that he was assisting the State's efforts

to obtain the death penalty," id. at 466, were used by the prosecution

to meet its statutory burden of proving deliberate conduct and pro

bable future dangerousness at the penalty trial. When the doctors

"went beyond simply reporting to the court on the issue of competence

and testified for the prosecution at the penalty phase ..., [their]

role changed and became essentially like that of an agent of the

State recounting unwarned statements made in a post-arrest custodial

setting." I_d. at 467. Since petitioner "did not voluntarily con

sent to the pretrial psychiatric examination[s] after being informed

of his right to remain silent and the possible use of his statements,

the State could not rely on what he said" without violating his

rights under the Fifth Amendment. Id. at 468.

Furthermore, as in Smith, Mr. Green was not accorded the assis

tance of counsel "in making the significant decision of whether to

submit to the examination[s]" of Doctors Guild and Stanley, and was

deprived of the opportunity for consultation with counsel concerning

"to what end the psychiatrist[s'] findings could be employed." Id.

at 471. Because a capital defendant already under indictment may

not be denied the "'guiding hand of counsel'" on such a crucial

"'life or death matter'" as the decision whether or not to talk to

22

doctors like Donald C. Guild and Charlton S. Stanley,- their testi-

10/mony also violated petitioner's Sixth Amendment rights. Ibid.

The State argued in the District Court that by calling two

psychologists to refute the testimony of Doctors Guild and Stanley,

9/ As employees of a state mental hospital, Doctors Guild and Stanley

testify regularly for the State in Mississippi criminal proceedings.

See Gator v. State, 402 So. 2d 316 (1981); May v. State, 398 So. 2d

1331 (1981); Anderson v. State, 381 So. 2d 1019 (1980); Cessna v.

State, 381 So. 2d 173 (1980); Gray v. State, 375 So. 2d 994, 1003

(1979)(capital case); Collins v. State, 361 So. 2d 333 (1978); Barr

v. State, 359 So. 2d 334 (1978); Hollins v. State, 340 So. 2d 438

(1976); Williamson v. State, 330 So. 2d 272 (1976)(testimony as to

any inculpatory statements made by defendant to doctor deemed inad

missible) .

10/ Petitioner was indicted in the instant case on August 11, 1976

(SF 6), nearly a month before the doctors began their evaluation.

The Supreme Court in Smith explicitly held that a defendant is en

titled to counsel at this stage of a criminal proceeding. See

Estelle v. Smith supra, 451 U.S. at 469-70 and cases cited therein.

As the Court stated in Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682, 689-90

(1972)(plurality opinion), one of the cases relied upon in Smith:

The initiation of judicial criminal pro

ceedings is far from a mere formalism. It is

the starting point of our whole system of ad

versary criminal justice. For it is only then

that the government has committed itself to

prosecute, and only then that the adverse posi

tions of government and defendant have solidi

fied. It is then that a defendant finds him

self faced with the prosecutorial forces of

organized society, and immersed in the intri

cacies of substantive and procedural criminal

law. It is this point, therefore, that marks

the commencement of the "criminal prosecutions"

to which alone the explicit guarantees of the

Sixth Amendment are applicable.

This is why the Court has repeatedly held that the Sixth Amendment

right to counsel "attaches . . . 'at or after the initiation of

adversary judicial criminal proceedings — whether by way of formal

charge, preliminary hearing, indictment, information, or arraign

ment.'" Moore v. Illinois, 434 U.S. 220, 226 (1977), quoting Kirby

v. Illinois, supra, 406 U.S. at 689.

23

petitioner rendered the testimony of the prosecution's doctors harm

less as a matter of "settled state law" (R. 106). However, Texas

law requires precisely the opposite result. In Clark v. State, 627

S.W.2d 693 (Tex. Crim. App. 1981), the Court of Criminal Appeals

held, under identical circumstances, that a capital defendant's

presentation of psychiatric testimony after the prosecution's doctor

has testified in violation of Smith does not render Smith error

harmless. The Court declared that "the introduction of evidence

seeking to meet, destroy or explain erroneously admitted evidence

does not waive the error or render the error harmless." Id. at 696.

The rule in the Supreme Court of the United States is the same.

Harrison v. United States, 392 U.S. 219 (1968). And this Court has

recently held that even where the State's doctor ultimately testi

fies in rebuttal, after the defense has gone forward with expert

testimony, Smith is still violated if the defendant was denied his

Sixth Amendment right to the assistance of counsel at the time of

the State's doctor's examination. Spivey v. Zant, 661 F.2d 464,

11/473-76 (5th Cir. 1981).—

II

The District Court recognized the validity of petitioner's

Smith claim (R. 44-46), but nonetheless rejected it upon the sole

11/ The State also contended below that the testimony of Doctors

Guild and Stanley was harmless because petitioner's psychological

experts essentially agreed with their testimony. Nothing could be

farther from the truth. As demonstrated in the Statement of Facts,

pp. 14-15, supra, the psychologists called by petitioner disagreed

with Doctors Guild and Stanley as to the correct clinical diagnosis

and also disagreed with them as to the correct answers to the statu

tory sentencing questions which determined under Texas law whether

petitioner would live or die.

24

ground that the claim had not been properly preserved by a contem

poraneous objection. This holding was incorrect for at least three

separate reasons.

First and foremost, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has

expressly held, in plain and unambiguous language, that defense

counsel's failure to interpose an objection does not result in a

waiver of the rights recognized in Smith. In Brandon v. State, ___

S.W.2d ___, No. 59,348, slip op. at pp. 1-2 (Tex. Crim. App. June 2,

1982), that Court stated:

Judgments of death will be reversed when

the appellate record shows that the defendant's

Fifth or Sixth Amendment objections to ...

[psychiatric testimony at the penalty phase

of a capital prosecution] were overruled despite

the State's failure to show that the proper warnings

had been given and that the assistance of counsel

had been made available. Fields v. State, 627

S.W.2d 714 (Tex. Cr. App. 1982); Clark v. State,

627 S.W.2d 693 (Tex. Cr. App. 1981); Thompson v.

State, 621 S.W.2d 624 (Tex. Cr. App. 1981).

Even when the appellate record does not show

such an objection, relief from judgments of

death will be granted in cases in which such

testimony was used when it is shown by post

conviction proceedings that the proper warnings

were not given or that the assistance of counsel

was not made available. Estelle v. Smith, 451

U.S. 454 (1981); Battie v. Estelle, 655 F.2d

692 (5th Cir. 1981); Ex parte Demouchette, [633]

S.W.2d [879, 881 n.1] (Tex. Cr. App., No. 68940,

May 26, 1982).

12/(emphasis added). Since, as Brandon establishes, there is no

"contemporaneous objection" rule in Texas with respect to Smith

error, the absence of an objection at petitioner's trial obviously

would not bar the granting of federal habeas corpus relief pursuant

12/ For the Court's convenience, the full text of the as-yet un

published Brandon opinion is annexed to this brief as Appendix A.

25

to Smith. See Miller v. Estelle, 677 F.2d 1080, 1084 (5th Cir.

1982); Thompson v. Estelle, 642 F.2d 996, 998 (5th Cir. 1981);

Braxton v. Estelle, 641 F .2d 392, 394 (5th Cir. 1981); Moran v.

Estelle, 607 F .2d 1140, 1141-42 (5th Cir. 1979); Burns v. Estelle,

592 F.2d 1297, 1301-02 (5th Cir. 1979), adhered to en banc, 626 F.2d

396 (5th Cir. 1980).

This Court has only recently held that even where a state

supreme court's decisions are ambiguous concerning application of

contemporaneous objection rules, this Court wiil presume that the

merits are being reached in the absence of express holdings to the

contrary. Henry v. Wainwright, ___ F.2d ___, No. 80-5184, slip op.

at 15617 (5th Cir. Sept. 20, 1982)(on remand from the Supreme Court

of the United States). Here, given Texas' unequivocal declaration

in Brandon that it does not apply a contemporaneous objection rule

to defeat Smith claims, the District Court clearly erred in finding

13/a procedural forfeiture.

Secondly, defense counsel at petitioner's trial did object to

the testimony of Dr. Stanley on Fifth Amendment grounds. Counsel

stated that Dr. Stanley's testimony was "nothing more than a vio

lation of the Fifth Amendment of the [C]onstitution, telling this

13/ The rule articulated in Brandon has also been applied by the

Court of Criminal Appeals to invalidate death sentences pursuant to

Smith in Ex Parte Demouchette, 633 S.W.2d 879, 881 n.l (Tex. Crim.

App. 1982), and Ex Parte English, ___ S.W.2d ___, No. 68, 953 (Tex.

Crim. App. Sept. 15, 1982)(although the Court's opinion does not

mention the absence of a contemporaneous objection, the trial

court's Findings of Fact clearly state (finding #23, p.3) that no

such objection was raised; for this Court's convenience, the as-yet

unpublished opinion in English and the trial court's Findings of

Fact are annexed to this brief as Appendix B).

26

defendant to testify against himself" (SF 3052). And a moment later

counsel asked the trial judge to strike "all the testimony from this

witness" on the basis of the objection just stated (SF 3053). Al

though the defense attorney's objection to Dr. Stanley's testimony

was also based on the doctor-patient privilege and the fact that the

doctor's examination of petitioner had been ordered solely to exa

mine his competency, the Fifth Amendment clearly was mentioned as

one of the grounds for the objection.

This Court recently held in another death case, where counsel

totally failed to object to a constitutional defect but had registered

a proper objection to a similar defect earlier in the trial, that no

procedural forfeiture had occurred. Henry v. Wainwright, supra,

slip op. at 15616. Surely, where counsel interposes an objection

that specifically encompasses the appropriate constitutional provision

as one of the grounds for relief, habeas corpus should not be denied.

See Huffman v. Wainwright, 651 F.2d 347 (5th Cir. 1981), and cases

14/cited therein.

14/ Concedely, counsel in this case did not object on constitu

tional grounds to the testimony of the State's other psychiatrist,

Dr. Guild. But if Dr. Stanley's testimony is held violative of

Smith, Dr. Guild's testimony hardly renders the constitutional error

harmless. Dr. Stanley's testimony was by far the more detailed of

the two, running nearly twice the transcript length of Dr. Guild's.

And in summation the prosecution relied heavily upon the fact that

both doctors had reached the identical conclusion (SF 3328-30).

(They had actually differed in one crucial respect: only Dr. Stanley

testified that petitioner would behave violently in prison, SF 3090-

97, 3107-08, 3320.) Petitioner's own two expert witnesses testified

in diametric opposition to Doctors Guild and Stanley on the critical

issues. (See p. 24 n. 11, supra.) The State could not seriously

contend in any case of conflicting expert testimony, let alone a

death case in which the jury deliberated at sentencing for 7 1/4

hours (SF 137), that Dr. Guild's testimony alone would render the

unconstitutional admission of Dr. Stanley's testimony harmless

beyond a reasonable doubt. Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18

(1967).

27

Finally, even if Texas had a contemporaneous objection rule

with respect to Smith error, and even if defense counsel had totally

failed to object, Randy Glenn Green could not be sent to his death

on the basis of a procedural forfeiture of the fundamental rights

declared in Smith. In Smith itself there was no contemporaneous

objection on any constitutional ground, yet both this Court and the

Supreme Court held that the federal habeas corpus petitioner in that

case was entitled to relief. This Court expressly stated that the

failure of Smith's attorney to object did not constitute a procedural

default, and gave three "sufficient" answers to the State's waiver

argument. One of those answers, that a successful objection was

foreclosed under existing state law, Smith v. Estelle, 602 F.2d 694,

708 n.19, suffices to establish that the District Court erred in its

finding of a waiver in the present case. The Supreme Court'expressly

ratified the reasoning of footnote 19 of this Court's Smith decision.

451 U.S. at 468 n.12. .

The manifest injustice that would follow from holding petitioner

to have waived Smith error here is especially apparent from analysis

of the decisions of the Texas courts during the period surrounding

his trial. While as a general proposition contemporaneous objections

may encourage state courts to re-examine prior decisions (see Respon

dent's Supplemental Motion to Dismiss in the District Court below,

R. 66), that concept has iittle meaning when measured against the

reality of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals' decisions of 1973-79

upholding the practice ultimately invalidated in Smith. During that

period the Court of Criminal Appeals repeatedly rejected the claims

of Texas capital defendants that the prosecution's use in penalty

28

trials of psychiatric testimony based upon routine pretrial

examinations violated the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. See, e.g.,

Armstrong v. State, 502 S.W.2d 731, 734-35 (Tex. Crim. App. 1973);

Livingston v. State, 542 S.W.2d 655, 661-62 (Tex. Crim. App. 1976);

Gholson v. State, 542 S.W.2d 395, 399-401 (Tex. Crim. App. 1976);

Shippy v. State, 556 S.W.2d 246, 254 (Tex. Crim. App. 1977); Von

Byrd v. State, 569 S.W.2d 883, 897 (Tex. Crim. App. 1978); Wilder v.

State, 583 S.W.2d 349, 358 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979). Only after Smith

was finally decided by the highest court in the land did the Court

of Criminal Appeals finally relent, and then only because "the

Supreme Court, in its role as the ultimate expositor of the United

States Constitution, ha[d] spoken otherwise." Thompson v. State,

621 S.W.2d 624, 626 (Tex. Crim. App. 1981). Thus, it is clear that

constitutional challenges to prosecutorial psychiatric testimony at

the penalty phase were totally foreclosed in the courts of Texas --

no matter how many times the Court of Criminal Appeals might be

afforded an opportunity to re-examine its decisions.

In Smith, a unanimous Supreme Court categorically held that

constitutional rights basic to the fairness of a capital sentencing

proceeding had been violated by the Texas practice of using routine

pretrial psychiatric examinations against capital defendants. Surely

petitioner should not now be sent to his death "the 'deluded instru

ment' of his own execution," Estelle v. Smith, supra, 451 U.S. at

462, solely because his trial lawyer failed to interpose a ritualistic

objection which under Texas law the trial court was required to

reject summarily. In Engle v. Isaac, ___ U.S. ___, 71 L.Ed.2d 783,

805 (1982), the case primarily relied upon by the District Court

29

below (R. 48-49), the Supreme Court noted that "principles of comity

and finality[,] ... [i]n appropriate cases ...[,] must yield to the

imperative of a fundamentally unjust incarceration." In death cases,

where the Supreme Court has consistently demanded especially ex-

15/acting standards of fairness, those principles must yield to the

imperative of a fundamentally unjust death sentence brought about by

the defendant's unwarned and uncounseled cooperation with the pro

secution's psychiatrists. Estelle v. Smith, supra, 451 U.S. at 466-

71. 16/

As this Court declared in its Smith opinion:

If the state is entitled to compel a defen

dant to submit to an examination, it can, in

an effort to gain the defendant's cooperation,

mislead him or indeed lie to him about the

significance of the examination; it can take

advantage of his ignorance or lack of under

standing. It can coerce him in any way that

does not make his statements less useful to

the interrogating psychiatrist. Psychologi

cal pressure, sharp practices, and deceit are

likely to be, in effect, the means of compel-

1 5 / Enmund v. Florida, U.S. , 73 L.Ed.2d 1140 (1982); Eddinqs

v. Oklahoma, ___ U.S. ___, 71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982); Estelle v. Smith,

supra; Bullington v. Missouri, 451 U.S. 430 (1981); Adams v. Texas,

448 U.S. 38 (1980); Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980); Godfrey v.

Georgia, 446 U.S. 420 (1980); Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (1979);

Presnell v. Georgia, 439 U.S. 14 (1978); Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S.

586 (1978); Bell v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 637 (1978); H. Roberts v. Louisiana,

431 U.S. 633 (1977); Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977); Davis

v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1976); Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S.

280 (1976); S. Roberts v . Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976).

16/ The State certainly cannot rely upon one of the other major

policy considerations underlying Isaac, i.e., that limiting federal

habeas corpus litigation will encourage a prisoner to accept his

sentence and "look forward to rehabilitation and becoming a con

structive citizen." Engle v. Isaac, supra, 71 L .Ed. 2d at 800 n.

31, quoting Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 262 (1973)

(Powell, J., concurring). Id. at 800 n. 32. That concept obviously

has no applicability to capital cases, in which the condemned habeas

petitioner faces death rather than rehabilitation if he is foreclosed

by rules of procedural forfeiture from raising a valid constitutional claim.

30

ling examinations. These tactics are inhe

rently discriminatory. A knowledgeable de

fendant, or one with vigilant attorneys, will

either simply refuse to submit to an examina

tion or will bargain with the state to have

the examination conducted by a psychiatrist

who is more likely to favor the defense. Only

defendants who do not know better will allow

themselves to be examined by psychiatrists

antecedently favorable to the state.

We have every reason, therefore, to give

effect to the apparent command of the fifth

amendment and to hold that a defendant may not

be compelled to speak to a psychiatrist who

can use his statements against him at the

sentencing phase of a capital trial. If a

state wishes to prove a defendant's propensity

to commit future crimes of violence by using

evidence gathered at a psychiatric examination,

the defendant must voluntarily consent to the

examination. It follows that Judge Porter

was correct when he held that if a defendant

indicates that he wishes to remain silent,

"he may not be questioned by the psychiatrist

for the purpose of determining dangerousness."

Judge Porter also held that the defendant must

be warned that he had a right to remain silent;

since Smith was in custody when he was inter

viewed, this holding too was correct.

602 F.2d 707-708 (footnote omitted);

[The decision whether or not to submit to a

psychiatric examination in a capital case] is

a vitally important decision, literally a life

or death matter. It is a difficult decision

even for an attorney; it requires a knowledge

of what other evidence is available, of the

particular psychiatrist's biases and predilec

tions, of possible alternative strategies at

the sentencing hearing. For a lay defendant,

who is likely to have no idea of the vagaries

of expert testimony and its possible role in

a capital trial, and who may well find it dif

ficult to understand, even if he is told,

whether a psychiatrist is examining his compe

tence, his sanity, his long-term dangerousness

for purposes of sentencing, his short-term

dangerousness for purposes of civil commit

ment, his mental health for purposes of treat

ment, or some other thing, it is a hopelessly

31

difficult decision. There is no reason to

force the defendant to make it without "the

guiding hand of counsel." Powell v. Alabama,

287 U.S. 45, 57, 53 S.Ct. 55, 77 L .Ed. 158

(1933).

Id. at 708-09. This Court has consistently adhered to the funda

mental principles of Smith in its subsequent decisions, rejecting

numerous arguments presented by the Texas Attorney General in an

effort to limit and weaken Smith1s safeguards. See Battie v.

Estelle, 655 F.2d 692 (5th Cir. 1981); Gholson v. Estelle, 675 F.2d

734 (5th Cir. 1982).

To hold that petitioner may be executed merely because his

attorney failed to interpose a meaningless objection would seriously

undermine the policies articulated by this Court and by the Supreme

Court's equally sweeping, unanimous holding in Smith. Use of such

a super-technical rule of procedural forfeiture' to defeat an ob

viously valid Smith claim would also run contrary to the basic

policy underlying all Supreme Court decisions in capital cases

since 1976:

the penalty of death is qualitatively dif

ferent from a sentence of imprisonment,

however long. Death, in its finality,

differs more from life imprisonment than

a 100-year prison term differs from one

of only a year or two. Because of that

qualitative difference, there is a corre

sponding difference in the need for reli

ability in the determination that death

is the appropriate punishment in a specific case.

Woodson v.

opinion).

(plurality

(plurality

North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305 (1976) (plurality

See also Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 357-58 (1977)

opinion); Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586, 604 (1978)

opinion); Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 637-38 (1980);

32

Eddings v. Oklahoma, ___ U.S. ___, 71 L.Ed. 2d 1, 9 (1982).—

That policy was eloquently restated by this Court only recently in

Gholson v. Estelle, supra, 675 F.2d at 737, a case decided on the

basis of Smith:

There is no doubt this Court and the

Supreme Court recognize the death penalty

as a qualitatively different form of punish

ment than any other that can be imposed.

[Citations omitted] ... It is different

from all other punitive measures in that

it is the most severe and exacting disci

plinary mechanism available to a society

that considers itself civilized and decent.

In addition, the termination of human life

is the most final and decisive method for

inflicting a penalty that can be conceived.

It is precisely the inflexible and terminal

nature of the death penalty that makes it

a matter of exceeding consequence to assure

that before such a condemnation is made

the individual receives the full force of

the protections and safeguards guaranteed by the Constitution.

To send petitioner to his death on the basis of his statements

to Doctors Guild and Stanley, unwittingly made without the guidance

of counsel and without the slightest awareness that he was assisting

the State's effort to take his life, simply cannot be squared with

these concepts. The judgment of the District Court should be reversed.

17/ The Supreme Court has several times declined in recent years

to dishonor valid constitutional claims against sentences of death

on grounds of procedural forfeiture. In addition to Smith itself

(see p. 28, supra), see Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 361

(1977)(trial counsel's failure to request access to full pre-sentence

report did not waive constitutional error in State's failure to

disclose its contents), and Eddings v. Oklahoma, U.S. , 71

L.Ed.2d 1, 14 & n. 1 (dissenting opinion of the Chief Justice)(relief

granted on Eighth Amendment claim not raised in the State trial

court); cf. Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 647-48 (1980)(dissenting

opinion of Justice Rehnquist)(relief granted on Due Process and

Eighth Amendment claim not preserved before State Supreme Court).

33

CONCLUSION

This Court should reverse the judgment below and grant habeas

corpus relief vacating the unconstitutional sentence of death imposed

upon petitioner.

Respectfully submitted,

JOEL BERGER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University School of Law

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

Dated: October/?, 1982

34

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, JOEL BERGER, hereby certify that on October/?, 1982, I

served a copy of the within Brief for Petitioner-Appellant upon

counsel for Respondent-Appellee by depositing same in the United

States mail, first class mail, postage prepaid, addressed as

follows: Hon. Mark White, Attorney General of the State of Texas,

P.0. Box 12548, Capitol Station, Austin, Texas 78711 (Att: Leslie

A. Benitez, Esq., Assistant Attorney General).

APPPENDIX A

+..̂

i

THELETTE BRANDON, Appellant

NO. 59,348 v. - - - Appeal from MCLENNAN County

THE STATE OF TEXAS, Appellee

O R D E R

The trial court entered a judgment that the appellant

was guilty of capital murder and that he be put to death. We

affirmed. Brandon v. State, 599 S.W.2d 567 (Tex.Cr.App. 1980) .

The United States Supreme Court vacated our judgment and remanded

the case for further consideration in light of Estelle v. Smith,

451 U.S. 454 (1981). Brandon v. Texas, 453 U.S. ___, 101 S.Ct.

3134 (1981).

In Smith, the Court held that a defendant’s Fifth

Amendment rights were violated by the admission of a psychiatrist's

testimony at the punishment stage of a capital trial when the

defendant had not been advised before the pretrial psychiatric

examination that he had a right to remain silent and that any

statement he made could be used in the capital punishment deter

mination, and that his Sixth Amendment rights were violated

by the admission of the testimony when he had been denied the

assistance of counsel in deciding whether to submit to the exam

ination and to what end the psychiatrist's findings could be

employed. Judgments of death will be reversed when the appellate

record shows that the defendant's Fifth or Sixth Amendment ob

jections to such testimony were overruled despite the State's

failure to show that the proper warnings had been given and that

the assistance of counsel had been made available. Fields v.

State, 627 S.W.2d 714 (Tex.Cr.App. 1982); Clark v. State, 627

S.W.2d '693 (Tex.Cr.App. 1981); Thompson v. State, 621 S.W.2d

624 (Tex.Cr.App. 1981). Even when the appellate record does

not show such an objection, relief from judgments of death will

be granted in cases in which such testimony was used when it is

BRANDON - 2

shown by post-conviction proceedings that the proper warnings

were not given or that the assistance of counsel was not made

available. Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981); Battie v.

Estelle, 655 F .2d 692 (5th Cir. 1981); Ex parte Demouchette,

____S.W.2 d _____ (Tex.Cr.App., No. 68,940, May 26, 1982).

In the case now before us on appeal, the appellant

made no Fifth or Sixth Amendment objections to the psychiatrists'

1/testimony at the punishment stage of the trial. While these

failures to object will not necessarily prevent a reviewing

2/

court from reaching the constitutional issues, they have left

the record silent on the facts which are necessary to a resolu

tion of those issues. Those facts must be developed. Since this

3/

court has no effective procedures for fact-finding, it is

necessary to abate this appeal so that the trial court can use

the fact-finding procedures of a motion for new trial to develop

the facts on the Fifth and Sixth Amendment issues.

For the purposes of the appellate procedures set out

in Chapter 40 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the appellant

shall be deemed to have filed, on the day our mandate of abate

ment issues, a motion for new trial raising the Fifth and Sixth

Amendment issues discussed in Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454

(1981). If the trial court grants a new trial, its order shall

be transmitted to this court in a supplemental transcript and

this appeal will be dismissed. If the trial court denies a new

trial, a supplemental transcript of these proceedings shall be

added to the appellate record in this court. The parties then

may file their appellate briefs on those issues in this court.

1/

The appellant made Fifth Amendment objections to the

psychiatrists' testimony at the guilt stage of the trial, but

he made only statutory objections to their testimony at the

punishment stage.

y See Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454, 468 n. 12 (1981).

3/

See Ex parte Young, 418 S.W.2d 824, 826 (Tex.Cr.App.

1967) .

BRANDON - 3

The appeal is abated.

DELIVERED: June 2, 1982

PER CURIAM

EN BANC

APPPENDIX B

EX PARTE SAMMIE NORMAN ENGLISH Habeas Corpus Application

From HARRIS CountyNO. 68,953

O P I N I O N

!

*

)

This is a post-conviction application for habeas corpus

relief pursuant to Article 11.07, V.A.C.C.P. The applicant was

convicted of the offense of capital murder with the penalty of

death. The conviction was affirmed by this Court; English v.

State, 592 S.W.2d 949 (Tex.Cr.App. 1980), cert, denied 449 U.S.

891, 101 S.Ct. 254, 66 L.Ed.2d 120 (1981).

The applicant now asserts that his privilege against self

incrimination and the right to effective assistance of counsel

were violated when psychiatric testimony was admitted at the

punishment stage of his trial. The trial court has made specific

-findings of fact, which are supported by the record, that the

applicant before a pretrial psychiatric examination was not

informed that he did not have to participate and that he could

remain silent, that his statements and the psychiatric testimony

based on the examination could be used at the punishment, stage

of his trial. Also, the applicant's counsel were not notified

in advance that the psychiatric examination was being made to

prepare the psychiatrist to testify on the issue of the applicant's

dangerousness.

The Supreme Court's holding in Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S.

454, 101 S.Ct. 1866, 69 L.Ed.2d 359(1981) requires the reversal

of the judgment in this case. See also Ex parte Demouchette,

633 S.W.2d 879 (Tex.Cr.App. 1982); Clark v. State, 627 S.W.2d

693 (Tex.Cr.App. 1982) affirmed on rehearing following the

Governor's commutation of sentence; Thompson v. State, 621 S.W.2d

624 (Tex.Cr.App. 1981); Fields v. State, 627 S.W.2d 714 (Tex.Cr.

App. 1982).

ENGLISH

The psychiatrist's testimony and opinion in this case was

based on his examination of the applicant. The hypothetical

questions propounded to the witness also incorporated the

witness' own examination and findings concerning the applicant.

Cf. Vanderbilt v. State, 629 S.W.2d 709 (Tex.Cr.App. 1981)

The relief sought will be granted.

It is so ordered.

DALLY, Judge

Delivered September 15, 1982

En Banc

EX PARTE § IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF

§ HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS

SAMMIE NORMAN ENGLISH

Applicant

§ 230TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT

FINDINGS OF FACT

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT:

NOW COME SAMMIE NORMAN ENGLISH, Applicant in the above

entitled and numbered cause by and through his court appointed

attorney of record and the State of Texas by and through its

Assistant District Attorney and present the following proposed

findings of fact applicable to Smith v. Estelle, 79-11^7 (May 18,

1981) :

1. Applicant was charged in Cause No. 263368, with the

felony offense of capital murder and assessed the death penalty.

2. Tom Stansbury and Bob Montgomery were appointed to

represent Applicant at his trial.

3. A Motion for Sanity/Competency Examination of Sammie

Norman English was filed jointly by Assistant District Attorney Andy

Tobias and defense counsel Thomas Stansbury on July 19, 1977.

4. On July 19, 1977, the Court signed an Order authorizing

■t-b— Harris County Forensic Psychiatric Unit to conduct a competency/

sanity examination of Applicant.

5. Applicant was subsequently examined in August, 1977,

by Jerome B. Brown, Ph.D. and Jose G. Garcia, M.D. of the Harris