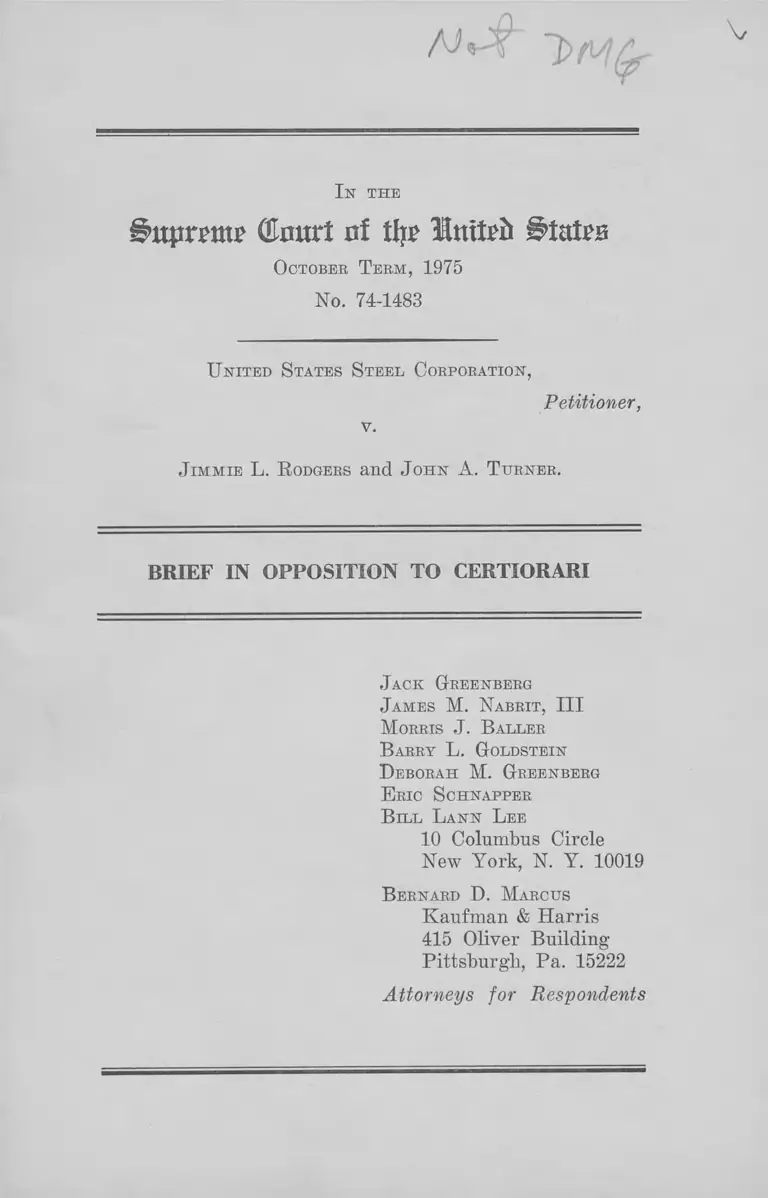

United States v. Rodgers Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Rodgers Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1975. 5be4a5ca-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19c9b6e7-57e6-41e8-85db-f71224d99dbc/united-states-v-rodgers-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(tart of tl|p States

October T erm, 1975

No. 74-1483

U nited States S teel Corporation,

v.

Petitioner,

Jimmie L. R odgers and J ohn A. T urner.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M orris J. B aller

B arry L. Goldstein

Deborah M. Greenberg

E ric S chnapper

B ill L ann L ee

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

B ernard D. Marcus

Kaufman & Harris

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

Attorneys for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below ....................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 1

Question Presented ........................................................... 1

Statutes and Rules Involved................... 2

Statement ............................................................................. 3

Argument ............................................................................... 12

1. The local civil rule and orders of the district

court were in conflict with Rule 23 of the Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure .............................. 12

2. The district court’s rulings conflicted with Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .................. 15

3. Local Civil Rule 34(d) violates the First

Amendment ................................................... 15

4. The trial court’s rules and orders interfered

with free access to counsel ................................... 17

5. The restraint on communications was censorial

and discriminatory ................................... 19

6. The court of appeals carefully delimited its

ruling to avoid hroad issues involving other

types of regulations which might he imposed

in other cases or by other rules of court ....... 20

Conclusion 22

11

T able op A uthorities

Cases: page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, ------ U.S. ------ (de

cided June 25, 1975) ----------------------------------------- 15

Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963) ........... 17

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960) .................. 18

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941) .................. 16

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964) ..................................16,18

Carroll v. Princess Ann County, 393 U.S. 175 (1968).... 17

Chandler v. Fretag, 348 U.S. 3 (1954) .......................... 18

Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 252 (1941) ............................ 16

Dickerson v. United States Steel Co., 64 F.R.D. 351

(E.D. Pa. 1974), appeal quashed, 9 E.P.D. 10063

(3rd Cir. 1975) cert, denied------ U .S .------- , 44 L.Ed.

2d 102 (1975) ................................................................. 19

Eaton v. City of Tulsa, 415 U.S. 697 (1974) ............... 16

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigative Commit

tee, 372 U.S. 539 (1963) ................................................ 18

In re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959)................................ . 16

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).......7,13,16,17

Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S.

415 (1971) ....................................................................... 17

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 (1946) .............. 16

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ...................... 18

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 296 (1974) ............... 18

Ill

page

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ...................... 18

Southeast Promotions Ltd. v. Conrad,------U.S. ------- ,

43 L.Ed.2d 448 (1975) ................................................. 17

United Mineworkers v. Illinois State Bar Association,

389 U.S. 217 (1967) ..................................................... 16

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

5th Cir. No. 74-3056 ..................................................... 6

United Transportation Union v. State Bar, 401 U.S.

576 (1971) ....................................................................... 16

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962) ........................... 16

Statutes and Buies:

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................................................. 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) ..................................................... 4

Civil Bights Act of 1964, Title V I I .................... 3,12,14,15

Federal Buies of Civil Procedure, Buie 23 ...........2,10,12,

13,14

Local Buie 19B, S.D. Florida ........................................ 20

Local Civil Buie 22, N.D. Illinois.................................. 20

Local Buie 20, D. Maryland .......................................... 20

Local Buie 34, W.D. Pa.................................................... 2,11

Local Buie 34(d), W.D. Pennsylvania .... 4,10,11,12,

15, 20, 21

Local Buie 6, S.D. Texas .............................. ................. 20

Local Buie C.B. 23(g), W.D. Washington ................... 20

Other Authority:

Manual for Complex Litigation, 1 Moore, Federal

Practice, 1(1.41 (3d Ed. 1974, part 2) .............. 11,20,21

In the

(Urntrt of % B u U b

October T erm, 1975

No. 74-1483

U nited S tates Steel Corporation,

v.

Petitioner,

J immie L. R odgers and John A. T urner,

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Third Cir

cuit dated January 24, 1975, is reported at 508 F.2d 152.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth in

the petition.

Question Presented

Whether the court of appeals was correct in issuing a

writ of mandamus and/or prohibition in an employment

discrimination case to strike down a local rule and district

court orders which for three years prevented civil rights

lawyers from talking with black steelworkers who were

potential class members and prohibited the lawyers from

meeting with an NAACP branch which included potential

2

class members, where the district court had not even de

termined if the case could proceed as a class action, either

1. On the ground that such restraints on free speech

were not authorized by statute and imposed unreasonable

conditions upon the availability of class actions which were

inconsistent with Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

and with Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; or

2. Upon the ground that the local rule and orders of

court violated the First Amendment rights of plaintiffs

and their potential class members and lawyers to freedom

of speech, freedom of association, and privacy of associa

tion, and also violated their rights to freedom from dis

criminatory or censorial regulations of their speech and

associations, as well as violating the right to counsel.

Statutes and Rules Involved

The case involves Local Rule 34 of the United States

District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania,

which provides in part:

Rule 34. Class Actions.

In any case sought to be maintained as a class action.

# * #

(c) Within 90 days after the filing of a complaint

in a class action, unless this period is extended on

motion for good cause appearing, the plaintiff shall

move for a determination under subdivision (c)(1 )

of Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as to

whether the case is to be maintained as a class action.

In ruling upon such a motion, the Court may allow

the action to be so maintained, may disallow and strike

the class action allegations, or may order postpone

3

ment of the determination pending discovery of such

other preliminary procedures as appear to be appro

priate and necessary in the circumstances. Whenever

possible, where it is held that the determination should

he postponed, a date will be fixed by the Court for

renewal of the motion before the same judge.

(d) No communication concerning such action shall

be made in any way by any of the parties thereto, or

by their counsel, with any potential or actual class

member, who is not a formal party to the action, until

such time as an order may be entered by the Court

approving the communication.

Statement

Respondents Rodgers and Turner are black steelworkers

employed at United States Steel Corporation’s Homestead

Works. They brought this employment discrimination case

in the United States District Court for the Western District

of Pennsylvania in August 1971, against the steel company

and the local and national unions representing workers at

the plant. The complaint alleges a pervasive pattern of

racial discrimination by the defendants in violation of

Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and of 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, and requests injunctive relief and back pay for

the named plaintiffs and a class of more than 1,200 black

workers employed at Homestead Works. As the opinion

below explains, notwithstanding the fact that early in the

case the parties stipulated the definition of the class in

volved, the district court has not yet ruled on plaintiffs’

repeated motions that the case be certified as a class ac

tion. 508 F.2d at 155.

This petition involves a collateral issue not dealing with

the merits of plaintiffs’ job discrimination claim which has

4

not yet been tried or decided. This phase of the case deals

with the fact that the district court by rule and orders

prevented plaintiffs’ lawyers from talking with any of the

black workers at Homestead Works for three and a half

years until the court of appeals issued its writ of man

damus and/or prohibition.

Plaintiffs’ local attorney is Bernard D. Marcus of the

Pittsbui'gh firm of Kaufman & Harris. He has associated

with him in the case several lawyers employed by the

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., a

non-profit corporation which has furnished legal aid in

civil rights cases in state and federal courts for thirty-

five years. The Fund is a New York corporation, approved

to function as a legal aid organization. Neither Mr. Marcus

nor the Legal Defense Fund lawyers have accepted or ex

pect any compensation from the plaintiffs, or from any

member of the potential class. Mr. Marcus and his firm

will be compensated only in the event attorneys fees may

eventually be taxed against the defendants by the court

as authorized by Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k). Any

fee which might be awarded by the court on account of

work done by Legal Defense Fund employees will be paid

to that non-profit corporation and not to the individual

salaried staff attorneys.

For over three years from the filing of the suit until

the decision of the court of appeals, plaintiffs’ attorneys

were forbidden from communicating with class members

by Local Rule 34(d) and several orders issued to enforce

that rule.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys first sought permission to talk with

class members by motion filed September 21, 1973. The

motion alleged that plaintiffs’ ability “ effectively to present

the claims of class members, to discover the case, and to

define the scope of the issues with greater specificity de

5

pends in significant part on tfieir having access to class

members, to investigate their complaints, and to supple

ment the available defendants’ documentary materials by

interviewing their employees.” Plaintiffs asked for a gen

eral order “allowing proper communications” and stated

that “It would be impractical and unworkable for plaintiffs

to reapply specifically for permission to communicate with

particular class members.”

At a hearing on September 29, 1973, the court denied

the motion:

T he Court: The ruling of the Court is that they

can’t contact people who are not named as parties until

an order of Court. No person is to be contacted with

out my permission. As to the specific individual con

cerned after giving notice to the defendants who the

individual is and what you expect to learn from him,

then we can determine whether this is sufficient reason

to change the general rule.

The transcript of this conference will take the place

of and will be considered the order of this Court, no

written order being necessary by agreement of all

parties. (App. 85a-86a)

Plaintiffs made a further effort to get permission to talk

with potential class members in June 1974. In the back

ground of this second effort was a related development

which had occurred in the Northern District of Alabama,

where on April 12, 1974, the court had approved two con

sent decrees in a suit by the United States against nine

major steel companies, including United States Steel, and

the United Steelworkers of America, APL-CIO. The con

sent decrees, approved on the same day the Alabama suit

was filed, purported to be a nationwide settlement of all

race and sex discrimination claims in the steel industry,

6

including claims at Homestead Works.1 The consent decrees

changed seniority practices at steel plants such as Home

stead Works, and provided a back pay remedy for certain

black employees. The consent decrees provide for commu

nication to black class members by the defendants and the

solicitation of waivers of Title VII claims in order for

them to receive back pay.

Plaintiffs in the Rodgers case, who had been prevented

from communicating with class members since suit was

filed in 1971, again moved in April 1974 for a class certifi

cation and proposed that the court sign a notice to class

members explaining the status of the case. Plaintiffs moved

for an order prohibiting the defendants from soliciting

releases from class members, but withdrew this motion

when defendants agreed at the hearing to show plaintiffs’

counsel written communications in advance and afford

plaintiffs time to apply for a protective order if counsel

objected to any communication.

On June 26, 1974, plaintiffs moved for permission for

their counsel to talk with six named class members and to

attend a meeting of the Homestead Branch of the NAACP.

The moving papers explained that two of the six workers

had sought information and assistance about employment

discrimination from the Assistant Labor Secretary of the

NAACP in New York, and had been referred by her to the

Legal Defense Fund attorneys. The Homestead Branch

of the NAACP had independently invited the plaintiffs’

attorneys to come to a branch meeting to discuss discrim

1 The legality of the consent decrees was promptly challenged

by black workers from various states (including Rodgers and

Turner) who intervened in the Alabama case. The case is now

pending in the Fifth Circuit on the appeal of those intervenors

from an order rejecting all challenges to the consent decrees.

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 5th Cir No 74-

3056.

7

ination at Homestead Works. The motion pointed out the

nature and purposes of the NAACP and explained the cir

cumstances of the invitation which included a request for

information about the Alabama consent decrees and the

pending local litigation. The motion alleged specifically

that a denial of the right to communicate would violate

constitutionally protected rights of free speech and asso

ciation as well as the right of counsel to practice law. The

motion relied on N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963),

and a series of succeeding cases.

On the same date, June 26, plaintiffs filed a related

motion entitled “Renewed Motion for Permission to Com

municate with Members of the Proposed Class” (App.

166a-170a). The latter motion pointed out that the court

had set January 15, 1975, as the deadline for completion

of discovery; that under the prior orders of court coun

sel were unable to communicate with class members for

discovery purposes, that plaintiffs had undertaken a great

deal of time-consuming and costly computer analysis and

discovery of defendants’ records and now needed to talk

with members of the class in order to effectively present

their claims, to define the issues and complete discovery,

and that it was impractical and unworkable for plaintiffs

to apply specifically for the right to communicate with

particular class members. The motion alleged also that

it was inequitable to prohibit communication by plaintiffs

while the defendants could communicate with the class

pursuant to the consent decrees to offer them back pay

and seek to persuade employees to execute releases waiv

ing their rights.

At a hearing on the motion on June 27, 1974, the court

orally forbade plaintiffs’ attorney from attending an

NAACP meeting scheduled for July 7, and reserved deci

sion pending briefs on the constitutional issues. The court

8

also stayed all discovery and a class determination nntil

January 15, 1975. Plaintiffs then moved for entry of a

written order embodying these rulings and for a certifica

tion to permit an interlocutory appeal. On July 19, 1974,

the court orally denied the certification and the motion

to communicate with the NAACP. The court granted the

motion to talk with the six workers, hut when U. S. Steel’s

attorney pointed out that only two of the six had con

tacted the New York office of the NAACP, the court

ruled that counsel could speak with them or any other

class members only if they first filed in court the class

members’ affidavit stating how they happened to consult

counsel. The court’s oral ruling is quoted in the opinion

below, 508 F.2d at 157-158.

Judge Teitelbaum made it clear that the prior restraint

was not merely to prevent solicitation and “barratry.”

When Mr. Marcus asked the court if he and his colleagues

could attend the NAACP meeting if they would agree not

to represent any of the workers there, except in the pend

ing class action, the court “made clear that its purpose in

continuing the ban on communication was to prevent dis

cussion of the Alabama consent decree” (508 F.2d at 158).

The purpose of the restriction on communication was to

prevent what Judge Teitelbaum called “ sabotage” of the

Alabama consent decree (508 F.2d at 152). Although plain

tiffs requested written orders, none were filed.

Plaintiffs filed an appeal and a petition for a writ of

prohibition or mandamus with respect to those orders, and

also sought a stay pending the decision of the court of

appeals on the merits. When the stay was denied without

prejudice for lack of a district court order giving reasons

for its action, plaintiffs again applied to the district court

for a written order—which was finally forthcoming on

9

September 12, 1974, embodying the June 27 and July 19,

1974, oral rulings.

On January 24, 1975, the court of appeals issued a writ

of mandamus or prohibition with respect to the orders

restricting communications. In its opinion the court of

appeals observed that the district court had superimposed

a condition on the availability of the class action device

that raises serious First Amendment issues:

. . . The two provisions make clear that the District

Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania has

superimposed upon Rule 23 a condition that the class

action device be available only to those plaintiffs will

ing to submit to an assertion of a dual power by the

court—the power to postpone class action determina

tion and to impose a prior restraint in the meantime.

That the prior restraint may be of extended duration

is clear; in this case it has continued for more than

three years.

The imposition of such a condition upon access to

the Rule 23 procedural device certainly raises serious

first amendment issues. . . . There is no question but

that important speech and associational rights are in

volved in this effort by the NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc. to communicate with potential

black class members on whose behalf they seek to

litigate issues of racial discrimination. See, e.g.,

United Transportation Union v. State Bar, 401 U.S.

576 (1971); NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).

And the interest of the judiciary in the proper ad

ministration of justice does not authorize any blanket

exception to the first amendment. See Wood v.

Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962); Craig v. Harney, 331

U.S. 367 (1947); Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331

(1946); Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941).

10

Whatever may be the limits of a court’s powers in

this respect, it seems clear that they diminish in

strength as the expressions and associations sought to

be controlled move from the courtroom to the outside

world. See T. Emerson, The System of Freedom of

Expression, 449, et seq. (1970). (508 F.2d at 162-163).

However, the court of appeals found it unnecessary to

rest its decision on First Amendment grounds, because

it concluded that the district court had no statutory au

thority to promulgate Local Rule 34(d) which it found

to he inconsistent with the policy underlying Rule 23 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Third Circuit

noted that the district court was seeking to prevent “bar

ratry” ; that the policy of Rule 23 was “ in favor of having

litigation in which common interests or common questions

of law or fact prevail, disposed of where feasible in a

single lawsuit” ; that there was no federal common law

offense of barratry; and that even if the federal rules

and statutes were construed to authorize the adoption of

local rules for controlling barratry, a serious “constitu

tional issue of overbreadth would he presented by the

Local Rule in its present form.” (508 F.2d 163-164). The

court went on to state:

The rule imposes a prior restraint on all communica

tion, not merely communication aimed at stirring up

litigation. Think what our reaction would be to a

state statute which required that attorneys submit all

communicatons to be made to persons not yet their

clients to the prior approval of a court. (508 F.2d at

164)

The court then concluded that Local Rule 34(d) was

outside the rule-making power granted to the district

court. The majority found it unnecessary to decide

11

whether a local rule regulating communications “after

a class determination has been made,” would be valid but

pointed out that drafting such a rule would require “ care

ful consideration of overbreadth.” 508 F.2d at 164.

The court noted that Local Rule 34(d) was adopted in

response to a suggestion in the Manual for Complex Liti

gation, see 1 Moore, Federal Practice U 1.41, at 27-32 (2d

Ed. 1974, part 2). The court below noted that Local Rule

34(d) contains none of the exceptions recommended in

the Manual. In any event, the court of appeals made it

plain that it had no occasion to rule on whether the sug

gested Local Rule 7 in the Manual contained sufficiently

specific exceptions to avoid the overbreadth problem. 508

F.2d at 164-165, note 18.

Judge Weis filed a concurring opinion which agreed that

Local Rule 34 should be set aside “not, however, because

of the time period in the litigation, but, rather because it

is overbroad in its wording.” Thus Judge Weis did reach

the constitutional question and decide it in plaintiffs’ favor

saying: “Accordingly, it seems to me that local Rule 34,

as it applies to civil rights actions, must be set aside as

being unnecessarily broad.” 508 F.2d at 166.

The court of appeals, and this Court, denied motions by

U. S. Steel for a stay pending certiorari. ------U.S. ------- ,

43L.ed.2d 649. After the district court vacated its prior

orders, plaintiffs’ attorneys finally met with the Homestead

Branch of the NAACP and discussed racial discrimination

problems at Homestead Works with black steelworkers.

12

Argument

This case does not warrant review on certiorari because

the decision of the court of appeals is in accord with this

Court’s prior decisions, and there is no conflict among the

circuits on the questions presented. The decision of the

Third Circuit, which set aside the trial court’s across-the-

board prior restraint of all communications between plain

tiffs’ attorneys and the potential class of black steel

workers, is entirely supportable on a number of grounds.

The result is plainly correct because the district court’s

rule and orders were inconsistent with Rule 23 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, with Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, with the First Amendment’s

guarantee of freedom of speech and association, and with

the right to counsel. In the factual context of the case the

district court’s rulings were discriminatory, censorial and

inequitable in the treatment of plaintiffs vis-a-vis the

defendants.

1. The local civil rule and orders of the district court were

in conflict with Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

The court below properly concluded that Local Rule

34(d) and the orders implementing that rule in this case,

which were ostensibly designed to supplement Rule 23 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, were actually in

consistent with the policy underlying Rule 23. As the

court below analyzed the case, the district judge had

asserted a “ dual power . . . to postpone class action

determination [for an extended period] and to impose a

prior restraint in the meantime.” 508 F.2d at 162. Local

Rule 34(d), as Judge Gibbons observed, “ imposes a prior

restraint on all communication, not merely communication

13

aimed at stirring up litigation.” 508 F.2d at 164. The

Third Circuit acknowledged that district courts had some

powers to regulate communications and referred to “ the

undoubted power to impose some restrictions on first

amendment rights during the course of judicial proceed

ings.” 508 F.2d at 162. But the court found no authoriza

tion in the statutes or rules for a trial court to condition

the availability of the Rule 23 class action device upon a

litigant’s submission to an indefinite period of prior

restraint on all communications about the case.

The court noted the injustice of imposing a restraint on

speech in order to prevent abuse of the class action device,

where the court indefinitely delayed a decision about

whether the class action procedure could be employed in

any event. It was in this context that the court made a

distinction between the role of a court in imposing-

restraints before and after class certification. If class

representative status was eventually denied the years of

imposed restraint on free speech would have been imposed

for naught. The court of appeals found it improper to

delay class certification while imposing a broad gag rule

as a condition to seeking representative status.

The court of appeals also noted that while the prevention

of “barratry” and “ solicitation” (cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963)) was one proffered justification for the

trial court’s rulings, the ban was in no way limited to

communications which might fit within those general

rubrics. Plaintiffs’ attorneys were forbidden to interview

workers while investigating the case and gathering wit

nesses and evidence unless they first obtained the court’s

permission for each interview by making a showing of

what they expected to learn from each worker. Plaintiffs’

attorneys, some of whom were employed by a civil rights

14

organization, were forbidden from attending a meeting of

the Homestead Branch of the NAACP because some

potential class members would attend the meeting. The

prohibition against attending the NAACP meeting forbade

mere presence at the meeting. Plaintiffs’ counsel would

have been in violation of this order if they had attended

the meeting without speaking at all, if they attended and

spoke only of unrelated subjects, if they spoke about the

case only in the most restrained and proper manner, if

they distributed copies of relevant court papers or orders,

or if they merely gave an abstract explanation of Title VII

of the Civil Bights Act of 1964. The court of appeals was

entirely correct in finding no authority to impose such

restraints on free speech and association conferred by the

general grant of authority to make rules of practice “not

inconsistent with” the Federal Buies of Civil Procedure.

In any event, the Third Circuit concluded that the

orders and rule of the district court were inconsistent with

the policy of Buie 23 of the Federal Buies of Civil

Procedure which is “ in favor of having litigation in which

common interests, or common questions of law or fact

prevail, disposed of where feasible in a single lawsuit.”

508 F.2d at 163. The court perceived the district court’s

ruling as preventing the full implementation of the policy

of Buie 23. That conclusion is entirely reasonable because

lawyers subject to the district court’s restraints are quite

evidently hobbled in carrying out the obligation to fairly

and adequately represent the class. A lawyer conscien

tiously engaged in representing a large class of workers

would want to learn their grievances and concerns by

personal interviews, and would want to respond to

inquiries by class members. The duty of fair representation

probably encompasses some obligation of responsiveness

to concerns of class members who are not named plaintiffs.

15

It certainly encompasses an obligation to fully investigate

the facts of racial discrimination suffered by the class in

order to adequately litigate the merits of the case. It is

fair to conclude that the restraints imposed by the district

court on plaintiffs in this case so hamstrung their presen

tation of the case as to conflict with the policy of Rule 23

supporting class actions.

2. The district court’s rulings conflicted with Title YII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The arguments that the district court exceeded its au

thority by rulings conflicting with the principles of Rule 23

have added force in the context of a fair employment suit

brought under Title YII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As

this Court held in Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, ------

U .S .------ (decided June 25, 1975), Congress intended that

Title VII plaintiffs have the benefit of the class action

device, for backpay claims as well as for injunctive relief.

Title V II suits are encouraged by statutory provisions for

the award of counsel fees to successful plaintiffs who

vindicate the public interest in eliminating discrimination.

Albermarle Paper Co., supra. The rules and orders of the

district court restraining communications were all the more

inappropriate in a case such as this where plaintiffs’ at

torneys were charging the class members no fees, offered

to agree not to represent any more clients among the class

members, and were entirely dependent upon the court it

self to determine any fee they might obtain if they even

tually won the case on the merits.

3. Local Civil Rule 3 4 (d ) violates the First Amendment.

The trial court imposed unconstitutional prior restraints

on free speech and association in violation of the First

Amendment. The decision of the court of appeals, while

16

not resting on constitutional grounds, recognize “ the

important speech and associational rights . . . involved in

this effort by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. to communicate with potential black class mem

bers on whose behalf they seek to litigate issues of racial

discrimination.” 508 F.2d at 163. And the Third Circuit

cited this Court’s decisions in United Transportation

Union v. State Bar, 401 U.S. 576 (1971), and N.A.A.C.P. v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), recognizing the free speech

and association rights involved in such litigation efforts.

See also, Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex

rel. State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964), and United Mine

Workers v. Illinois State Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217

(1967).

This Court’s decisions also make it clear that plaintiffs’

counsel are not stripped of all First Amendment rights

simply because they are attorneys before the bar of the

court. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, supra, 377 U.S.

1, 8. And as the court below put it, “ the interest of the

judiciary in the proper administration of justice does not

authorize any blanket exception to the first amendment.”

508 F.2d at 163. An unbroken line of cases from Bridges v.

California, 314 U.S. 252, 268 (1941), and including Craig v.

Harney, 331 U.S. 252 (1941); Pennekamp v. Florida, 328

U.S. 331 (1946); In re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959); and

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375, 384, 393 (1962), dispels any

notion that lawyers are without free speech rights to talk

about pending cases. To justify punishment (let alone

prior restraint), there must be “ an imminent, not merely

a likely, threat to the administration of justice.” Craig v.

Harney, 331 U.S. 367, 376; cf. Eaton v. City of Tidsa, 415

U.S. 697, 698 (1974).

Of course, on the facts of this case, there is no question

about any allegedly improper or punishable conduct by

17

plaintiffs’ counsel. They have obeyed the district court’s

prohibition against communication and there is not the

slightest suggestion in the record that they engaged in any

solicitation or communication in violation of the court

rules and orders. Thus, the case does involve the power of

a court to punish disobedience of its orders or allegedly

improper speech or conduct. Rather, the case involves the

validity of a broad prior restraint. This Court has set

forth, now well established principles disfavoring prior

restraints in the area of First Amendment freedoms.

Southeast Promotions Ltd. v. Conrad, ------ U.S. ------ , 43

L.Ed.2d 448, 459-460 (1975); Organization for a Better

Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415, 419 (1971); Carroll v.

Princess Ann County, 393 U.S. 175, 181 (1968); Bantam

Boohs v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963).

The prior restraint system set up by the trial court is

fatally overbroad in its sweeping restraint on entirely

lawful communications. It has become axiomatic that

“precision of regulation must the touchstone in an area so

closely touching our most precious freedoms,” N.A.A.C.P.

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 438 (1963). By establishing a prior

restraint sweeping far beyond any legitimate concern of

the court in regulating the conduct of class actions, the

district court’s rule and orders limited First Amendment

freedoms in a fashion far more sweeping than could be

justified by any governmental interest involved. N.A.A.C.P.

v. Button, supra.

4. The trial court’s rules and orders interfered with free

access to counsel.

Freedom of association includes a right to privacy of

association. The district court’s requirements that every

contact between plaintiffs’ counsel and members of the

class be disclosed prevents class members from consulting

18

with, or assisting plaintiffs’ lawyers in private and makes

their every contact known to their employers. These rules

invade the traditional attorney-client privacy. Little

imagination is required to perceive that many a potential

client or informant would be loath to approach counsel by

running the gauntlet imposed by the trial court’s orders.

“ Freedom [of speech, press and association] are protected

not only against heavy handed frontal attack, but also from

being stifled by more subtle governmental interference,”

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516, 523 (1960); Shelton v.

Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960); Gibson v. Florida Legislative

Investigative Committee, 372 U.S. 539 (1963).

When black steelworkers seek to consult plaintiffs’ at

torneys they seek to exercise “ the right of individuals and

the public to be fairly represented in lawsuits authorized

by Congress to effectuate a basic public interest.” Brother

hood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1, 7

(1964). As the Court said in that case, “laymen cannot

be expected to know how to protect their rights when deal

ing with practiced and carefully counselled adversaries,

. . . ” {ibid.). Indeed, the right to be heard by counsel of

one’s own choice has been called “unqualified.” Chandler v.

Fretag, 348 U.S. 3, 9 (1954). See also, Powell v. Alabama,

287 U.S. 45, 69 (1932), where the Court said that an

arbitrary refusal to hear a party by counsel would be a

denial of due process “ in any case, civil or criminal.” And

see, Procunierv. Martinez, 416 U.S. 296 (1974), condemning

unjustified restrictions on prisoners’ access to legal assis

tants and law students employed by counsel.

5. The restraint on communications was censorial and dis

criminatory.

The district court’s restraint on communications was

one-sided and unfair in its impact upon the efforts of black

workers to oppose the defendant company and union.

Defense counsel were entirely free to consult with their

clients in respect to any matters relevant to the conduct of

the lawsuit. The company and union have virtually limit

less opportunity to communicate with black steelworkers

in the regular course of business, and in the conduct of

union affairs. Beyond that, the defendants had judicial

sanction to explain the meaning of the consent decrees, and

at a later date to offer back pay and solicit the workers

release of their Title YII claims. “Implementation Com

mittees” composed of company and union representatives

met with workers to explain the Alabama consent decree.

In this context, the district court entered orders with

the avowed purpose to prevent plaintiffs’ attorneys from

discussing the consent decrees with class members— even

those who invited them to come to a civil rights organiza

tion meeting for this purpose. 508 F.2d at 158. This

censorship of plaintiffs’ speech unfairly disadvantaged

those workers who sought to oppose the consent decrees,

and gave an undue advantage to the def endants who sought

to defend that decree and interpose it as a defense to the

Rodgers suit. (For a similar case where U. S. Steel has

sought to use the consent decrees to defeat a previously

filed Title YII suit, see Dickerson v. United States Steel

Co., 64 F.R.D. 351, 360 (E.D. Pa. 1974), appeal quashed

9 E.P.D. 10063 (3d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, -------U .S ._____,

44 L.Ed.2d 102 (1975).) The district court’s rulings con

stituted an invidious discrimination which allowed the

defendants to voice their views with the workers by meet

20

ings and by written communications while the plaintiffs

were totally restrained from speaking.

6. The court of appeals carefully delimited its ruling to

avoid broad issues involving other types of regulations

which might be imposed in other cases or by other rules

of court.

There is no conflict of circuits on the questions pre

sented here because no other court of appeals has decided

similar issues. Indeed, insofar as our research has dis

covered, no court has adopted a local rule as broad and

sweeping as Local Rule 34(d). Our research has located

only five other federal districts which have any rule

regulating communication in class actions.2 It is quite

clear that Local Rule 34(d) is uniquely restrictive even

among the small number of related federal court rules.

Four of the rules partially codified Suggested Local Rule

No. 7 in the Manual for Complex Litigation, 1 Moore

Fedral Practice (par. 72, 1973). These rules specifically

enumerate kinds of communication the rule is supposed to

cover and contain exceptions not present in Rule 34(d).

Petitioners have attempted to defend Local Rule 34(d)

by citation of the Manual. Actually the Manual quite

explicitly disavows any such permanent or absolute pro

hibition of contact with class members, Manual § 1.41:

The recommended preventive action, whether by

local rule or order, is not intended to be either a

permanent or an absolute prohibition of contact with

actual or potential class members. Promptly after the

entry of the recommended order, or the applicable

date of the local rule in a case, and at all times there

2 Local Rule 19B, S.D. Florida; Local Civil Rule 22, N.D.

Illinois; Local Rule 6, S.D. Texas; Local Rule C.R. 23(g) W.D.

Washington; Local Rule 20, D. Maryland.

21

after, the court should, upon request, schedule a hear

ing at which time application for relaxation of the

order and proposed communications with class mem

bers may he presented to the court. Since the recom

mended rule and order are designed to prevent only

potential abuse of the class action and are not meant

to thwart normal and ethically proper processing of a

case, the court should freely consider proposed com

munications which will not constitute abuse of the

class action. In many such cases, the class members

will have knowledge of facts relevant to the litigation

and to require a party to develop the case without

contact with such witnesses may well constitute a

denial of due process.

There will normally be some need for counsel to

communicate with class members on such routine

matters as answering factual inquiries and developing

factual matters in preparation for the class action

determination as well as for trial. In order that there

might be some minimal judicial control of these com

munications, it is suggested that ex parte leave may be

given by the court, If requesting counsel is at a

distance from the court, the request may be handled

by telephone.

No such cautionary note is present in Local Rule 34(d).

This fact is underlined by the district court rulings that

have exactly the unintended effect on the normal processing

of this case.

The opinion below carefully refrained from ruling on

the constitutional validity of suggested model provisions

such as those in the Manual. 508 F.2d at 164-165.

22

CONCLUSION

For tlie foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the petition for certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M orris J. Baller

B arry L. Goldstein

Deborah M. Greenberg

E ric S chnapper

B ill L ann L ee

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

B ernard D. M arcus

Kaufman & Harris

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

Attorneys for Respondents

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C 219