Manning v. School Board of Hillsborough County, Florida Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 2020

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Manning v. School Board of Hillsborough County, Florida Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 2020. f50e76e4-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19dcc067-aed6-464d-a403-6207f73af66f/manning-v-school-board-of-hillsborough-county-florida-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

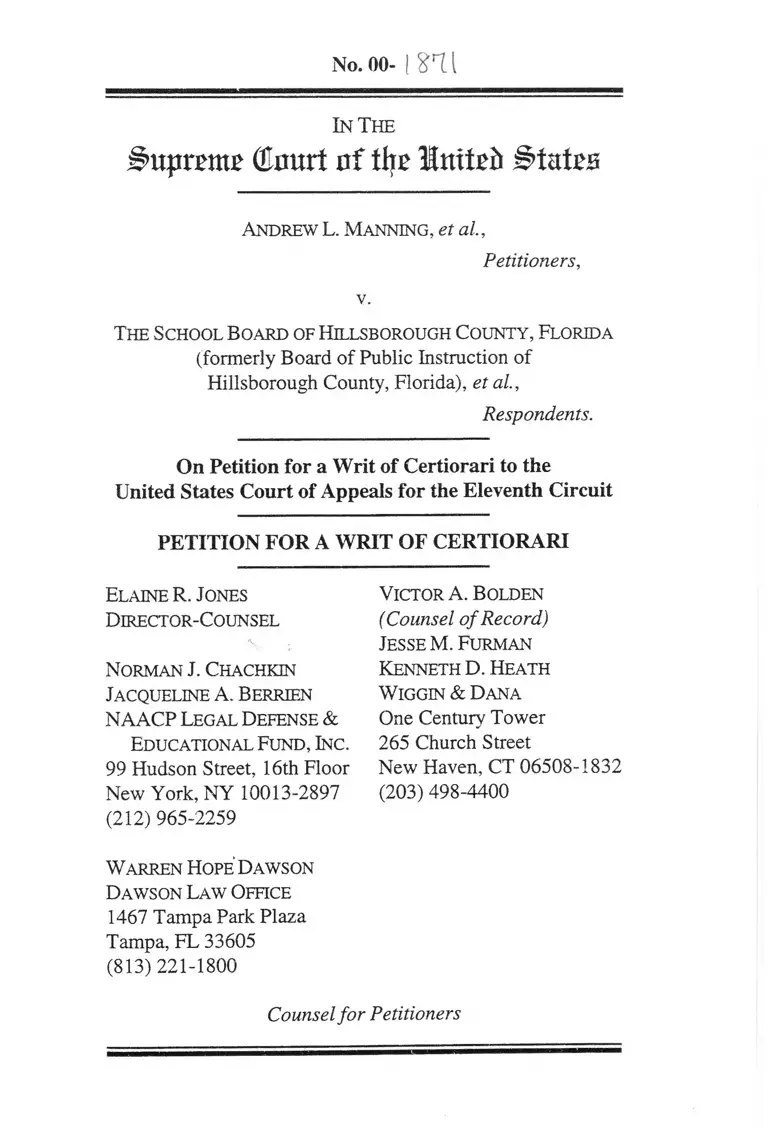

No. 00- 1811

In The

i^upratte Gunirt nf the United States

Andrew L. Manning, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

The School Bo.ard of Hillsborough County, Florida

(formerly Board of Public Instruction of

Hillsborough County, Florida), et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013-2897

(212) 965-2259

Warren Hope Dawson

Dawson Law Office

1467 Tampa Park Plaza

Tampa, FL 33605

(813) 221-1800

Victor A. Bolden

(Counsel o f Record)

Jesse M. Furman

Kenneth D. Heath

Wiggin & Dana

One Century Tower

265 Church Street

New Haven, CT 06508-1832

(203) 498-4400

Counsel fo r Petitioners

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the

District Court’s ruling that Respondent Hillsborough County

School Board had not eliminated the vestiges of de jure

segregation and had not demonstrated good-faith compliance

with the Court’s orders and the Equal Protection Clause. The

Eleventh Circuit’s opinion raises several questions

appropriate for review by this Court. The questions

presented are:

1. Whether the burden of proving that current racial

imbalances are related to the prior de jure segregated school

system or later actions by school district officials shifts to the

plaintiffs, even though the defendant school system has failed

to prove that these racial imbalances are not within its

control.

2. Whether a school board seeking relief from a

desegregation decree may satisfy the good-faith requirement

absent specific proof, or other objective evidence, that it is

unlikely to revert to its former unlawful conduct.

3. Whether, under the clearly erroneous standard, the

factual findings of the District Court may be disregarded by

the Court of Appeals in favor of findings by the Magistrate

Judge when the District Court findings are based on

extensive documentary evidence and reasonable inferences

drawn from facts in the record.

1. All African-American children eligible to

attend public schools in Hillsborough County,

Florida, and their next friends, Petitioners;

2. Darnel Cannon, Petitioner;

3. Nathaniel Cannon, Petitioner;

4. Norman Thomas Cannon, Petitioner;

5. Tyrone Cannon, Petitioner;

6. Andrew L. Manning, Petitioner;

7. Gail Rene Myers, Petitioner;

8. Randolph Myers, Petitioner;

9. Sanders B. Reed, Petitioner;

10. Sandra Reed, Petitioner;

11. Shayron Reed, Petitioner;

12. School Board of Hillsborough County,

Florida, Respondent;

13. Glenn Barrington, Respondent;

14. Carolyn Bricklemyer, Respondent;

15. Carol W. Kurdell, Respondent;

16. Jack R. Lamb, Respondent;

17. Joe E. Newsome, Respondent;

18. Candy Olson, Respondent;

19. Doris Ross Reddick, Respondent.

ii

LIST OF PARTIES

QUESTION PRESENTED...... ............................. i

LIST OF PARTIES .................................................................... ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..................................................... iv

OPINIONS BELOW ..................................................................1

JURISDICTION.......................................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED.................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE..................................................2

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT..............................8

I. The Decision of the Court of Appeals

Conflicts With This Court’s Decisions and

Those of Other Circuits and Improperly Shifts

the Burden of Proof on the Unitary Status

Issue to Plaintiffs................................................ 8

II. The Court of Appeals’ Interpretation o f the

Good-Faith Standard Conflicts With the

Framework Established by this Court’s

Decisions in Freeman and Dowell and with

the Tenth Circuit’s Interpretation...................18

III. The Court of Appeals Misapplied Governing

Law in its Review of the District Court’s

Factual Findings...............................................24

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CONCLUSION 29

IV

Anderson v. Bessemer, 470 U.S. 564 (1985)..... 24, 25, 26, 27

Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Educ., 233

F.3d 232 (4th Cir. 2000), vacated and reh ’g en

banc granted, Nos. 99-2389 (4th Cir. Jan 17, 2001).........21

Board o f Educ. v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991)............passim

Brown v. Board o f Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955).............. 23, 24

Brown v. Board o f Educ, 978 F.2d 585 (10th Cir.

1992)......................................................... 13,21,23

Coalition To Save Our Children v. State Board o f

Educ., 90 F.3d 752 (3rd Cir. 1996)................................15, 21

Dowell v. Bd. o f Educ., 8 F.3d 1501 (10th Cir. 1993).... 14, 19

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992)........................... passim

Friends o f Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Envtl. Servs. (TOC),

Inc., 528 U.S. 167 (2000)............. 22

Jenkins v. Missouri, 122 F.3d 588 (8th Cir. 1997)............... 14

Keves v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189 (1973)................................................................. 9, 14

Lockett v. Bd. o f Educ., I l l F.3d 839 (11th Cir.

1997) (Lockett I I ) ..................... 7

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987).............. 20, 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

V

Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70 (1995).........................10, 17

Peretzv. United States, 501 U.S. 923 (1991)........................ 27

Proffitt v. Wainwright, 685 F.2d 1227 (11th Cir.

1982)........................................................................................ 25

Reed v. Rhodes, 179 F.3d 453 (6th Cir. 1999).......................15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Bd. O f Educ.,, 402

U.S. 1 (1971).................................................................. 10, 11

United States v. City o f Yonkers, 181 F.3d 301 (2d

Cir.), vacated and opinion substituted, 197 F.3d 41

(2d Cir. 1999), cert, denied, 529 U.S. 1130 (2000)...........15

United States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export

Ass'n, 393 U.S. 199 (1968)....................................................22

United States v. Raddatz, 447 U.S. 667 (1980)...............27, 28

Constitutional Provisions Involved

United States Constitution Article III, § 1 ............................. 27

United States Constitution Amend. X IV ........................ passim

Statues and Rules

28U.S.C. § 1254(1).....................................................................2

28 U.S.C. § 63 6 .................................................................passim

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

VI

Page

12 Charles Alan Wright, et ah, Federal Practice and

Procedure, Civil 2d, § 3068.2 (2d ed. 1997).......................27

Fed. R. Civ. P .52 (a )................................................................ 25

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 00-

ANDREW L. MANNING,

et al., Petitioners

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY,

FLORIDA (formerly BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

OF HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY, FLORIDA), et al,

Respondents

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Andrew L. Manning, et a l, respectfully petition for a

writ o f certiorari to review the judgment of the United States

Court o f Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, App. la-4 la, is

reported at 244 F.3d 927. The opinions of the District Court,

App. 42a-56a, 57a-187a, are reported at 28 F. Supp. 2d 1353

and 24 F. Supp. 2d 1277, respectively. The reports and

recommendations of the Magistrate Judge, App. 188a-272a,

273a-314a, are unreported.

2

JURISDICTION

The Court of Appeals entered its judgment on March

16,2001. App. la. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution and 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1).

The Fourteenth Amendment provides, in relevant

part:

All persons bom or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and the State wherein they reside.

No state shall . . . deny any persons within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1) provides in pertinent part:

A judge of the court shall make a de novo

determination o f those portions of the report or

specified proposed findings and recommendations to

which objection is made. A judge of the court may

accept, reject, or modify, in whole or in part, the

findings or recommendations made by the magistrate.

The judge may also receive further evidence or

recommit the matter to the magistrate with

instructions.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case involves a decision by the Eleventh Circuit

reversing a District Court ruling that the School Board of

Hillsborough County, Florida, et al. (“Respondents”) had

failed to eliminate the vestiges of the prior de jure segregated

school system, had not complied in good faith with its orders

and the Equal Protection Clause, and therefore had not

achieved unitary status. The Eleventh Circuit rejected factual

3

findings detailing how Respondents failed to prove that it

was not responsible for the current racial imbalances in its

school system and how Respondents failed to act in ways

consistent with the District Court’s orders and the Equal

Protection Clause. In doing so, the Eleventh Circuit relied on

the factual findings made by the Magistrate Judge, findings

expressly rejected by the District Court.

The critical issues for purposes of this Petition

involve the circumstances arising from Petitioners’

allegations of violations of the District Court’s orders of May

11, 1971 and July 2, 1971 and the consent order of October

24, 1991.

The 1991 Consent Order modified, but did not replace

either the May 11, 1971 Order or the July 2, 1971 Order.

Instead, it maintained all of the obligations of these prior

orders, but permitted Respondents to convert its student

assignment system from single-grade centers to three-grade

middle schools and four-grade high schools. App. 68a. With

this conversion, Respondents intended to provide for a school

system organized into various feeder sets or “clusters,”

containing two or more elementary schools, one or more

middle schools and a single high school. “Because the school

system remained under the Court’s supervision,

[Respondents] were required to propose their Middle School

Plan (also known as the ‘Cluster Plan’) to the Court.” App.

67a. In implementing this new student assignment system,

Respondents pledged to “minimize (to the extent practicable)

the number of schools which deviate from the system-wide

student enrollment [race] ratios.” App. 69a.

In 1994, Respondents’ implementation of the third

year of this new student assignment system exacerbated

rather than ameliorated racial imbalances in the school

system. At that time, sixteen of Respondents’ schools had

exceeded the system-wide African-American student race

ratios by nearly 20% or more. As a result, Petitioners filed a

motion to enforce the District Court’s Orders. The District

4

Court referred the matter to a Magistrate Judge for a report

and recommendation pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1).

After a hearing and extensive briefing, the Magistrate Judge

concluded that the School Board’s actions violated neither

the 1971 nor the 1991 court orders. App. 188a-272a.

Following receipt of the Magistrate Judge’s report and

recommendation as well as objections filed by Petitioners,

the District Court determined that the lack o f a finding of

unitary status “effectively complicate^] the analysis of the

current controversy and demonstrate[d] the need to expand

the scope of the inquiry to a full-fledged determination of

whether the Hillsborough County school system has in fact

achieved unitary status.” App. 189a. Following further

evidentiary proceedings, the Magistrate Judge concluded in

its second report and recommendation that “the public school

system of Hillsborough County ha[d] attained unitary status

and should be released from Court supervision pursuant to

such further Orders as may be appropriate under the

circumstances.” App. 269a.

Based on its de novo review o f the Magistrate Judge’s

report and recommendation, the District Court rejected the

critical finding of unitary status, holding that Respondents

had failed to eliminate the vestiges of the prior de jure

segregated school system and had not complied in good faith

with the Court’s orders and the Equal Protection Clause.

App. 186a. Although the Hillsborough County public school

system experienced very little increase in the percentage of

its black student population during the last quarter century,

the District Court concluded that there was substantial racial

imbalance in its student enrollment. App. 84a-85a. Sixteen

schools had race ratios of African-American schoolchildren

far in excess of the 19.4% African-American population

system-wide; all but three were elementary schools. Id. The

Court was not “convinced that a shift in demographics and

residential patterns explains the racial imbalances in the

Hillsborough County School system.” Id.

5

Respondents relied on data “o f school-aged children

from ages 0-17 to explain enrollment ratios at the elementary

schools.” App. 98a. As the District Court noted, “the fact

that the 0 to 17 age group logically encompasses children too

young and too old to attend elementary school, counsels]

against placing great weight on the use o f these statistics.”

App. 98a. Indeed, on further inspection, the District Court

found that “the total number of school-aged students in the

attendance zones was an overstatement of actual attendees at

the elementary schools at issue,” App. 106a, and that “the

percentage of black school children actually attending each

school almost always exceeded the ‘overstated’

percentages . . . .” Id. Based on this evidence and evidence

presented by Petitioners, the District Court held that

Respondents had “failed to prove that the racial imbalances

are not traceable, in a proximate way, to the past de jure

segregation.” App. 87a.

The District Court also found that Respondents had

not complied in good faith with its orders. The District Court

found that Respondents “unilaterally determined that they

were not responsible for the racial imbalances; therefore,

there was no need to take affirmative steps” to desegregate.

App. 105a. In addition, Respondents failed to recognize and

adopt common desegregation techniques, even ones included

within the District Court’s prior orders. App. 134a. This

“lack of appreciation cast[] doubt on the competence of the

individuals charged with the task of desegregating the

schools.” Id. The District Court concluded that the lack of

good-faith compliance with its orders “taintfed] the analysis

of the other facets of the school district’s operations,” App.

184a-185a, and made it “very difficult in a case such as this

to categorize different aspects of the school system and

declare individual areas unitary.” App. 185a. Therefore, the

Court could not make factual findings for partial unitary

status on any aspect o f the school system.

6

In a supplemental opinion, following Respondents’

motion to alter or amend this judgment, the District Court

reiterated the bases for its prior ruling. The District Court

again noted “that the racial imbalances in Hillsborough

County appear traceable to [Respondents’] prior

unconstitutional practices and the continued unconstitutional

inaction.” App. 53a. The District Court also amplified the

basis for its ruling on good faith, finding no basis to conclude

that Respondents would not revert to their prior segregated

regime. Id. The District Court faulted Respondents for

failing to submit “documentation of the strategic planning

[they] have engaged in to ensure that discrimination does not

occur in the future.” Id. Likewise, the District Court pointed

out the failure of Respondents to provide the information

necessary to determine the relationship between school site

selection and current racial imbalances. See id. (“Wouldn’t it

be great, if, in the future, [Respondents] were able to say:

‘Here it is, we looked at the land value, population, growth

patterns, budget, racial compositions, etc., and even more,

without having been ordered by the Court to do so ”’).

A panel of the Eleventh Circuit reversed the District

Court’s decision and remanded with instructions to enter

judgment declaring Respondents’ school system unitary.

App. 2a. Rather than rely on the factual findings actually

made by the District Court, the Eleventh Circuit concluded

that the District Court “seemed to have adopted in toto

[Respondents’] theory o f the case (and the Magistrate Judge’s

finding).” App. 19a. The Court later noted: “Since the

district judge did not observe any of the testimony from the

evidentiary hearing, naturally she could not evaluate the

credibility o f the witnesses.” App. 22a.

The Eleventh Circuit then reversed the District

Court’s ruling on whether the Respondents had met their

burden of proof in eliminating the vestiges of the prior de

jure segregated school system to the extent practicable,

holding that the District Court relied on an improper legal

7

standard. While the existence o f racially imbalanced schools

required Respondents to “prove that the imbalances are not

the result of present or past discrimination on its part,” App.

35a (quoting Lockett v. Bd. o f Educ., 111 F.3d 839, 843 (11th

Cir. 1997) [hereinafter Lockett II]), “a school board

overcomes this presumption when it shows that some

external force, which is not the result of segregation and is

beyond the school board’s control, substantially caused the

racial imbalances.” Id. Once this standard had been met, the

Eleventh Circuit held, “a plaintiff [seeking] to preserve the

presumption of de jure segregation . . . must show that the

demographic shifts are the result o f the prior de jure

segregation or some other discriminatory conduct.” App.

36a. Applying this standard, the Eleventh Circuit found that

the plaintiffs “merely persuaded the district judge that

demographics alone did not account for the racial

imbalances,” a finding “insufficient to deny [the School

Board] a declaration of unitary status.” App. 36a-37a.

The Eleventh Circuit also reversed the District

Court’s finding with regard to good faith. Limiting its review

to only the issues of “apathy” and the lack of a viable

majority-to-minority (MTM) program, the Eleventh Circuit

found that neither issue provided a basis for the District

Court’s decision. According to the Court of Appeals, the

District Court’s finding of “apathy” amounted to nothing

more than an erroneous application of the law. App. 37a.

The Court of Appeals rejected the District Court’s

conclusions with respect to the MTM program on two

grounds: (1) even if properly implemented, this program

“should have had only marginal relevance in analyzing

whether Appellants’ ‘policies form[ed] a consistent pattern of

lawful conduct directed to eliminating earlier violations,’”

App. 39a (quoting Lockett II, 111 F.3d at 843), and (2)

discerning a school board’s good faith is a “subjective

finding,” depending “in part on the judge’s personal

observation of the witnesses.” App. 40a. “Where, as here, a

district judge does not personally observe the witnesses in

making subjective finding of fact, we view such a finding

with skepticism.” Id.

Having reversed both the District Court’s finding on

the elimination of vestiges and its finding on good faith, the

Eleventh Circuit declared that “federal judicial supervision of

the Hillsborough County school system shall cease.” App.

40a-41a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Petitioners seek this Court’s review for three reasons.

First, the Eleventh Circuit improperly shifted the burden of

proof on the issue of unitary status from the Respondents to

the Petitioners, a holding without precedent in this Court or

any other Court of Appeals. Second, the Eleventh Circuit

narrowed the scope of this Court’s good-faith inquiry to

require no showing that Petitioners will be free from

discrimination in the future. Third and finally, the Court of

Appeals disregarded the factual findings of an Article III

judge and instead relied on the findings of a Magistrate

Judge.

To address the fundamental issues raised herein, this

Court should grant certiorari and review the Eleventh

Circuit’s decision.

I. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Conflicts

With This Court’s Decisions and Those of Other

Circuits and Improperly Shifts the Burden of

Proof on the Unitary Status Issue to Plaintiffs

Under existing law, a school board operating under a

desegregation decree is not responsible for any racial

imbalances that are beyond its control. However, the

talismanic invocation of demographic change does not

relieve a school board of responsibility to remedy racial

imbalances that it has failed to prove are not within its

control. Nevertheless, the Eleventh Circuit has now held

9

that, so long as a “school board shows that demographic

shifts are a substantial cause of the racial imbalances,” App.

35a, the school board no longer has a burden to explain or

address any racial imbalance in its school system and the

burden of proof shifts to plaintiffs to establish that vestiges of

the de jure segregated system still exist. The Eleventh

Circuit’s ruling represents nothing less than a fundamental re

allocation of the burden of proof in school desegregation

cases. It is clearly inconsistent with this Court’s precedents

and the precedents of other Court of Appeals. As a result,

this Court should grant certiorari to review this decision.

It is well settled that, having once violated the

constitutional rights of African-American schoolchildren and

their parents by maintaining segregated schools, “[t]he duty

and responsibility of a school district once segregated by law

is to take all steps necessary to eliminate the vestiges of the

unconstitutional de jure system.” Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S.

467, 485 (1992). Long ago, this Court recognized that, given

this past violation, any existing racial imbalance is presumed

to be the product of a school system which has decided to

return to its old segregative ways. See Keyes v. School Dist.

No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S. 189, 208 (1973) (“[A]

finding of intentionally segregative school board actions . . .

creates a presumption that other segregated schooling within

the system is not adventitious”); id. at 210 (“[B]e it a

statutory dual system or an allegedly unitary system where a

meaningful portion of the system is found to be intentionally

segregated, the existence of subsequent or other segregated

schooling within the same system justifies a rule imposing on

the school authorities the burden of proving that this

segregated schooling is not also the result of intentionally

segregative acts”). As this Court reaffirmed in Freeman,

“[t]his inquiry is fundamental, for under the former de jure

regime racial exclusion was both the means and the end of a

policy motivated by disparagement of, or hostility towards,

the disfavored race.” 503 U.S. at 474.

10

External factors, such as widespread demographic

change, can effectively preclude further desegregation and

thereby provide an explanation for any current racial

imbalance. Racial balance is not to be achieved for its own

sake, but rather “is to be pursued when racial imbalance has

been caused by a constitutional violation.” Id. at 494. A

school district is under no duty to remedy racial imbalances

caused by demographic factors “once the racial imbalance

caused by the de jure violation has been remedied.” Id.

(citing Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1, 31-32 (1971)). Under such circumstances, this

Court’s command to desegregate “to the extent practicable”

has been satisfied.

The role of the District Court, however, is not to

presume that any demographic change or even some

substantial degree of demographic change accounts for any

current racial imbalance, much less all of it. In Board o f

Educ. v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991), this Court required the

District Court to consider whether the school district had

“made a sufficient showing of constitutional compliance.”

Id. at 249. Before finding that this showing has been made,

this Court held, the District Court must engage in a factual

determination highly dependent on the circumstances o f the

case and conclude that, to the extent that demographic change

accounts for any racial imbalance, this change is “not

attributable to the former de jure regime or any later actions

by school officials.” Freeman, 503 U.S. at 496. Nothing in

either Dowell, Freeman or this Court’s most recent

desegregation opinion, Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70

(1995), suggests that, to the extent that a school system

wishes to argue that an external factor made further

desegregation impractical, the burden for proving this does

not fall on the school district or is shifted to the plaintiff

schoolchildren.

Furthermore, this Court’s examination in Freeman of

whether “any later actions by school officials,” 503 U.S. at

11

496, could have resulted in the racial imbalance is critical in

determining whether a school system has satisfied its burden,

even in the midst of demographic change. School board

decisions, such as where to locate new school buildings, can

influence demographic patterns and promote the re

segregation of a school district. As this Court recognized in

Swann:

The construction of new schools and the closing of

old ones are two of the most important functions of

local school authorities and also two of the most

complex . . . . The result of this will be a decision

which, when combined with one technique or another

of student assignment, will determine the racial

composition of the student body in each school in the

system. Over the long run, the consequences of the

choices will be far reaching. People gravitate toward

school facilities, just as schools are located in

response to the needs of people. The location of

schools may thus influence the patterns o f residential

development of a metropolitan area and have

important impact on composition of inner-city

neighborhoods.

402 U.S. at 20-21; see also Freeman, 503 U.S. at 513

(Blackmun, J., with whom Stevens, J., and O ’Connor, J.,

join, concurring in the judgment) (“Close examination is

necessary because what may seem to be purely private

preferences in housing may in fact have been created, in part,

by actions of the school district”).

An initially successful desegregation plan does not

relieve a school board still under court order from

demonstrating that its decisions regarding school construction

and school closings did not contribute to any current racial

imbalances. See Swann, 402 U.S. at 21 (“In devising

remedies where legally imposed segregation has been

established, it is the responsibility of local authorities and

District Courts to see to it that future school construction and

12

abandonment are not used and do not serve to perpetuate or

re-establish the dual system”); see also Freeman, 503 U.S. at

514 (Blackmun, J., concurring in the judgment) (“Because of

the various methods for identifying schools by race, even if a

school district manages to desegregate student assignments at

one point, its failure to remedy the constitutional violation in

its entirety may result in resegregation, as neighborhoods

respond to the racially identifiable schools”). This Court

further defined the burden in Keyes:

[TJhe Board’s burden is to show that its policies and

practices with respect to school site location, school

size, school renovations and additions . . . , student-

attendance zones, student assignment and transfer

options, mobile classroom units, transportation of

students, assignment of faculty and staff, etc.,

considered together and premised on the Board’s so-

called ‘neighborhood school’ concept, either were not

taken in effectuation of a policy to create or maintain

segregation in the core city schools, or, if

unsuccessful in that effort, were not factors in causing

the existing condition of segregation in these schools.

Considerations of ‘fairness’ and ‘policy’ demand no

less in light of the Board’s intentionally segregative

actions.

413 U.S. at 214.

The Eleventh Circuit’s “substantial cause” standard

does not comply with this Court’s precedents. Under this

standard, a school district is no longer responsible for any

racial imbalance if it can show that external factors are a

“substantial cause” of racial imbalance within the school

district. App. 35a (“Where a school board shows that

demographic shifts are a substantial cause of the racial

imbalances, the defendant has overcome the presumption of

de jure segregation”) (citations omitted). A school system is

not required to explain, let alone remedy, other “substantial

causes,” which may be just as significant - or more - or

13

constitute the predominant basis for the current racial

imbalance. See App. 35a-36a (“[A] plaintiff does not

undermine the strength of a defendant’s demographic

evidence by merely asserting that demographics alone do not

explain the racial imbalances. Rather, for a plaintiff to

preserve the presumption of de jure segregation, the plaintiff

must show that that the demographic shifts are the result of

prior de jure segregation or some other discriminatory

conduct”) (citations omitted). This approach not only

conflicts drastically with the decisions of this Court, but also

those of other Courts of Appeals. Indeed, not a single Court

of Appeals has applied the burden-shifting test adopted by

the Eleventh Circuit.

Not long after Freeman, the Tenth Circuit, in Brown

v. Board o f Educ, 978 F.2d 585 (10th Cir. 1992), clearly

rejected this approach, reversing a district court for engaging

in precisely this type of burden shifting: “Neither Freeman

nor Dowell suggests that the plaintiffs in the remedial phase

of school desegregation litigation must make a new showing

of discriminatory intent in order to obtain relief from a

current condition of segregation. The district court wrongly

required the plaintiffs to make such a showing.” Id. at 589.

Rather than adopt a “substantial cause” approach, the Tenth

Circuit clarified the “substantial burden” placed on the

defendants in these cases. Id. at 590 (“In the continuing

remedial phase . . . the district court must impose upon

defendants the substantial burden of demonstrating the

absence o f a causal connection between any current condition

of segregation and the prior de jure system”). If this burden

is not satisfied, “the district court must retain some measure

of supervision over the school system.” Id. (citations

omitted).

Under the Tenth Circuit’s approach, a school system

does not fulfill its burden even with evidence of demographic

change, unless the current racial imbalance is “only a product

of demographic changes outside the school district’s

14

control.” Id. at 591. The Tenth Circuit also applied this

standard in Dowell v. Bd. o f Educ., 8 F.3d 1501 (10th Cir.

1993), requiring factual findings consistent with Freeman

that the school system did not play a role in, or contribute in

any way to, the demographic change. See id. at 1511 n.6.

The Eleventh Circuit’s “substantial cause” standard falls far

short of the Tenth Circuit’s mark.

The Eighth Circuit has also rejected the Eleventh

Circuit’s lenient standard. Following the remand after this

Court’s decision in Jenkins, the Eighth Circuit addressed the

presumption and expressly rejected the notion that anything

short of proof that the racial imbalances resulting from the

dual system have been eliminated in their entirety satisfies a

school board’s burden. See Jenkins v. Missouri, 122 F.3d

588, 593 (8th Cir. 1997) (“Only when a school district has

attained unitary status does the burden of proving disparities

were caused by intentional segregation shift back to the

plaintiffs”); see also id. at 595 (‘“ [Cjertainly plaintiffs in a

school desegregation case are not required to prove ‘cause’ in

the sense of ‘non-attenuation’”) (quoting Keyes, 413 U.S. at

211 n.17). The Eighth Circuit then upheld the District

Court’s finding that the School Board had not met its burden

for addressing the vestige of student achievement disparities,

despite evidence that they were substantially caused by

external factors:

It is evident that the District Court rejected Dr.

Armor’s opinion that socio-economic factors alone

were the cause of the achievement gap in the [Kansas

City Missouri School District], We cannot say that

the District Court clearly erred in making this finding.

The burden of proof was on the State to prove that it

had not caused the gap, and the State’s expert could

not explain a third of the achievement gap by his

socio-economic theory. The State simply failed to

carry its burden, and our discussion could end at this

point.

15

Id. at 598. Regardless o f the partial contribution of external

factors to existing disparities, the Eighth Circuit, like the

Tenth Circuit, refused to shift the burden of proof to the

plaintiffs and held that the school system had a continuing

responsibility to eliminate to the extent practicable those

racial imbalances or disparities within its control.1

Applying the well-established principles o f this Court,

the District Court in this case properly found that

Respondents failed to meet their burden of proof with regard

to current racial imbalances in their school system. While

Respondents argued that changing demographics had both

caused these racial imbalances and made it impractical to

ameliorate them, the District Court found that Respondents

had failed to explain numerous decisions that affected school 1

1 Recent rulings in other Circuits similarly offer no

support for the Eleventh Circuit’s position. The Sixth Circuit

has adopted the Freeman approach verbatim, noting that a

school district is not required to remedy imbalances caused

by demographic shifts “once the racial imbalance due to the

de jure violation has been remedied.” Reed v. Rhodes, 179

F.3d 453, 466 (6th Cir. 1999) (quoting Freeman, 503 U.S. at

494). Although the Court there affirmed a finding of unitary

status, it based its holding on the absence of any evidence to

suggest that the school system’s evidentiary burden had not

been met, and its opinion provides no support for the

Eleventh Circuit’s approach. See id. at 466-67.

Both the Second and the Third Circuits have held that

the burden does shift from the school system to the plaintiff

schoolchildren when there had never been a finding of a

vestige. See United States v. City o f Yonkers, 181 F.3d 301,

311 (2d Cir.), vacated and opinion substituted, 197 F.3d 41

(2d Cir. 1999), cert, denied, 529 U.S. 1130 (2000); Coalition

to Save Our Children v. State Board o f Educ., 90 F.3d 752,

776 (3d Cir. 1996). This legal distinction is not and could not

be the basis for the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in this case.

16

enrollment and that demographic change could not be solely

responsible for the racial imbalances. On the first point,

Respondents’ own analysis failed “to address [their] initial

decisions to draw attendance zones, decisions not to act when

it was apparent that those zones were inappropriate, or other

School Board decisions, such as, location of new schools, or

implementation (or lack thereof) of desegregation tools.”

App. 97a; cf. Freeman, 503 U.S. at 515 (Blackmun, J.,

concurring in the judgment) (“Nor did the court consider how

the placement of schools, the attendance zone boundaries or

the use of mobile classrooms might have affected residential

movement. The court, in my view, failed to consider the

many ways [the school board] may have contributed to the

demographic shifts”).

On the second point, the District Court found

Respondents’ evidence of demographic change insufficient to

prove that they were not responsible for the racial imbalances

existing in its schools. See App. 86a (“The Court is not

convinced that a shift in demographic and residential patterns

explains the racial imbalance in the Hillsborough County

School System”). Indeed, the demographic evidence

presented by Respondents raised more questions than it

answered:

Since the total number of school-aged students in the

attendance zones was an overstatement of actual

attendees at the elementary schools at issue, and

because the percentage of black school children

actually attending each school almost always

exceeded the “overstated” percentages, the Court is

hesitant to accept [the School Board’s] argument that

a shift in demography is the sole cause [of] the

imbalance in these elementary schools. Moreover,

Plaintiffs have provided evidence that the

discrepancies were not caused solely by a shift in

demography.

App. 106a.

17

The District Court did not and could not have

accepted any demographic data as a basis for releasing the

School Board from federal court supervision. If, as was the

case here, the demographic evidence did not provide a clear

and adequate basis for a factual finding that the School Board

did not contribute to or cause the current racial imbalances,

then the District Court could not have found that the School

Board had met its burden. See Freeman, 503 U.S. at 515

(Blackmun, J., concurring in the judgment) (“[Tjhis Court’s

decisions require the District Court ‘to dwell on what might

have been.’ In particular, they require the court to examine

the past to determine whether the current racial imbalance in

the schools is attributable in part to the former de ju re

segregated regime or any later actions by school officials”);

c f Jenkins, 515 U.S. at 100-01 (“Although the Court o f

Appeals later recognized that a determination of partial

unitary status requires ‘careful factfinding and detailed

articulation of findings,’ it declined to remand to the District

Court”). Moreover, following this Court’s guidance from

Freeman, the District Court in this case found that

Respondents’ history of poor compliance with its orders

counseled against a finding that the board had met its burden.

See App. 86a.2

2 Once the District Court concluded that Respondents

had failed to satisfy their burden with respect to the area o f

student assignment, given the interrelationships between this

area and the other Green factors, the District Court

appropriately refused to declare the school district unitary in

any area. App. 184a-185a; see Freeman, 503 U.S. at 497

(“[T]he Green factors may be related or interdependent. Two

or more Green factors may be intertwined or synergistic in

their relation, so that a constitutional violation in one area

cannot be eliminated unless the judicial remedy addresses

other matters as well . . . . As a consequence, a continuing

violation in one area may need to be addressed by remedies

in another”).

18

In reversing the District Court’s decision, the

Eleventh Circuit misapplied this Court’s precedents. Despite

ample evidence in the record in support of the District

Court’s factual findings, the Eleventh Circuit substituted its

novel “substantial cause” standard for the prevailing law.

Quite simply, the Eleventh Circuit has created a lesser burden

for school systems found previously to have engaged in de

jure segregation, thereby undermining the constitutional

guarantee of equal protection. This lesser burden turns this

Court’s command to desegregate “to the extent practicable”

on its head. By shifting the burden away from the defendant

school system, the Eleventh Circuit’s approach forces

plaintiffs in a school desegregation case, not the school

system, the party with control of all of the information

explaining the bases for its decisions, to account for racial

imbalances in the school system. To address the Eleventh

Circuit’s fundamental error in the interpretation of this

Court’s precedents as well as its conflicts with other Courts

of Appeals, certiorari should be granted. II.

II. The Court of Appeals’ Interpretation of the Good-

Faith Standard Conflicts With the Framework

Established by this Court’s Decisions in Freeman

and Dowell and with the Tenth Circuit’s

Interpretation

This Court should also decide whether, and to what

extent, a school board seeking relief from a desegregation

decree must submit proof of how it plans to comply in the

future with the dictates o f the Equal Protection Clause. By

failing to require such proof, and reversing the findings of the

District Court despite evidence that the school board might

return to its unconstitutional ways, the Eleventh Circuit

disregarded an important element of the framework

established by this Court in Dowell and Freeman. In doing

so, moreover, it created an irreconcilable conflict with the

Tenth Circuit, which has interpreted Dowell and Freeman to

19

require proof of “specific policies, decisions, and courses of

action that extend into the future” before a district court may

grant relief from a desegregation decree. Dowell, 8 F.3d at

1513 (internal quotation marks omitted). For these reasons as

well, this Court should grant certiorari.

In Dowell, this Court established that a school district

seeking relief from a desegregation decree must prove both

that “the vestiges of past discrimination [have] been

eliminated to the extent practicable,” Dowell, 498 U.S. at

249-50, and that the school district has demonstrated good

faith in complying with its obligations under the Equal

Protection Clause and the desegregation decree, see id.; see

also Freeman, 503 U.S. at 491-92. With respect to the latter

burden, the Court explained that the good-faith requirement

embodies both retrospective and prospective elements. First,

the school district must demonstrate that it has “operated in

compliance with the commands of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” and the court’s

desegregation decrees. Id. at 247. Second, and equally

important, a school district once found to have engaged in

intentional discrimination must submit objective proof that

“it was unlikely . . . [to] return to its former ways.” Id. As

the Dowell Court reasoned, “A district court need not accept

at face value the profession of a school board which has

intentionally discriminated that it will cease to do so in the

future.” Id. at 249.

In Freeman, this Court reaffirmed that the good-faith

requirement embodies a forward-looking component. In that

case, the Court held that a school district seeking termination

or modification o f a desegregation decree must first

demonstrate “its commitment to a course o f action that gives

full respect to the equal protection guarantees of the

Constitution.” 503 U.S. at 490 (emphasis added). Proof of

such commitment, the Court explained, demonstrates that a

school district “will not suffer intentional discrimination in

the future,” and provides “parents, students, and the public”

20

with “assurance against further injuries or stigma.” Id. at

498; see also id. at 498-99 (‘“A finding of good faith . . .

reduces the possibility that a school system’s compliance

with court orders is but a temporary constitutional ritual’”)

(quoting Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 321 (1st Cir.

1987)). Without such proof, the Court made plain, a school

district should not be relieved from a desegregation decree:

“When a school district has not demonstrated good faith

under a comprehensive plan to remedy ongoing violations,

we have without hesitation approved comprehensive and

continued District Court supervision.” Id. at 499 (citing

cases) (emphasis added).

The Eleventh Circuit ignored these pronouncements,

and looked only to the past in applying the good-faith

requirement in this case. See App. 38a (holding that

Respondents satisfy the good-faith requirement because they

“never violated a court order, never were sanctioned, and

consulted extensively with the African-American community

. . . prior to implementing new student assignments under the

1991 Task Force Report”). By contrast, the Tenth Circuit has

properly interpreted Dowell and Freeman to require proof of

both past conduct and future plans for a school district to

satisfy the good-faith requirement. See Dowell, 8 F.3d at

1511-13. As that Court explained the “second,” forward-

looking “prong” of the inquiry:

The second prong of the good faith inquiry is whether

it is “unlikely that the school board would return to its

former ways.” Dowell, 498 U.S. at 247. In Freeman,

the Supreme Court explained that “[a] school system

is better positioned to demonstrate its good-faith

commitment to a constitutional course of action when

its policies form a consistent pattern of lawful conduct

directed to eliminating earlier violations.” 503 U.S. at

491. We have since interpreted the good faith

showing set out in Freeman to mean that “[m]ere

protestations o f an intention to comply with the

21

Constitution in the future will not suffice. Instead,

specific policies, decisions, and courses o f action that

extend into the future must be examined to assess the

school system’s good faith .”

Id. at 1512 (emphasis added) (quoting Brown, 978 F.2d at

592). Thus, unlike school districts in the Eleventh Circuit,

school districts in the Tenth Circuit are required, consistent

with Dowell and Freeman, to submit proof of “future-

oriented board policies manifesting a continued commitment

to desegregation” before obtaining relief from a

desegregation decree. Id. at 1513.

The approaches of the Tenth and Eleventh Circuits

are irreconcilable. However, a review of other court of

appeals decisions following Dowell and Freeman reveals that

confusion over the interpretation of this Court’s holdings runs

deeper than conflict between the Tenth and Eleventh Circuits.

In Coalition to Save Our Children v. State Board o f Educ., 90

F.3d 752, 760 (3d Cir. 1996), for example, the Third Circuit

quoted the test from Freeman, but failed to engage in any

inquiry whatsoever with respect to good faith. By contrast, in

Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Educ., 233 F.3d

232, 252-53 (4th Cir. 2000), vacated and reh’g en banc

granted, Nos. 99-2389 et al. (4th Cir. Jan. 17, 2001), a panel

of the Fourth Circuit held that Freeman requires

consideration o f both the past conduct and future plans of a

school district. Unlike the Tenth Circuit, however, the panel

of the Fourth Circuit suggested that the latter consideration is

part of the inquiry into whether a school district has

eliminated the vestiges of discrimination to the extent

practicable, not the inquiry into good faith. In short, a review

of court of appeals decisions reveals a range of

interpretations of the test established in Dowell and Freeman.

Petitioners submit that, among these varied

interpretations, the Tenth Circuit’s understanding of the

good-faith requirement - requiring proof of both past

compliance with the mandates o f the Equal Protection Clause

22

and “future-oriented board policies manifesting a continued

commitment to desegregation” - is the correct interpretation

of this Court’s precedent and the Constitution, First and

foremost, the Tenth Circuit’s approach is consistent with the

test established by this Court in Dowell and Freeman while

the Eleventh Circuit’s approach is not. For example, the

Tenth Circuit’s approach to the good-faith requirement takes

seriously this Court’s statement, quoted above, that a district

court prior to vacating or terminating a desegregation decree

must find “that it [is] unlikely that the school board would

return to its former ways.” Dowell, 498 U.S. at 247. By

contrast, the Eleventh Circuit’s approach simply ignores this

statement and the others in Dowell and Freeman like it.

Second, requiring a school district to submit future

plans gives force to the constitutional guarantee of equal

protection while looking solely at a school district’s past

conduct does not. In particular, mandating such future-

oriented proof distinguishes those school districts that have

cynically complied with the literal terms of a desegregation

decree, without genuine commitment to the principles of the

Equal Protection Clause, from those districts that have truly

embraced their constitutional obligations and no longer need

judicial supervision to ensure continued compliance. By

doing so, the requirement ‘“ reduces the possibility that a

school system’s compliance with [the dictates of the Equal

Protection Clause] is but a temporary constitutional ritual.’”

Freeman, 503 U.S. at 498-99 (quoting Morgan, 831 F.2d at

321); c f Friends o f Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Envtl. Servs.

(TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 189 (2000) (holding that, when a

party asserts that relief is no longer appropriate, that party

bears the “‘heavy burden of persua[ding]’ the court that the

challenged conduct cannot reasonably be expected to start up

again” (quoting United States v. Concentrated Phosphate

Export A ss’n, 393 U.S. 199, 203 (1968)). As the Tenth

Circuit explained in Brown, “Depending on the definition of

‘good faith,’ the possibility of immediate resegregation

following a declaration o f unitariness seems all too real. For

23

this reason, . . . evaluation of the ‘good faith’ prong of the

Dowell test must include consideration of a school system’s

continued commitment to integration.” 978 F.2d at 592

(emphasis added).

Further, in light of the “complexities arising from the

transition to a system of public education freed of racial

discrimination,” Brown v. Board ofEduc., 349 U.S. 294, 299

(1955), the Tenth Circuit’s understanding of the good-faith

requirement is more pragmatic than the understanding

adopted by the Eleventh Circuit. As the record in this case

reflects, school desegregation decrees are often in effect for

significant periods of time before school districts can even

plausibly seek relief from them. Moreover, the decrees

required to eliminate all vestiges of an unconstitutional de

jure system are often ambitious in scope. Under these

circumstances, those affected by the decrees - parents,

students, teachers, administrators, and the public - come to

rely upon the policies enacted pursuant to the decrees.

Terminating a decree without some indication from the

school district regarding how it plans to comply with the

Equal Protection Clause absent the decree risks undermining

these settled expectations and, particularly in a large school

district, risks wreaking havoc on the school system. By

contrast, requiring proof of future-oriented board policies

manifesting a continued commitment to desegregation more

readily assures an orderly “transition to a system of public

education freed of racial discrimination,” id., and avoids any

potential misunderstanding on the part of parents, students,

teachers and the like that actions taken by a school district in

the wake of judicial supervision are inconsistent with

constitutional requirements.

Applying the Tenth Circuit’s correct understanding of

the good-faith requirement to this case, there is no doubt that

the Eleventh Circuit erred in reversing the finding of the

District Court that Respondents failed to demonstrate good

faith under Dowell and Freeman, or that the Eleventh

24

Circuit’s error will harm Petitioners. Putting aside self-

serving statements of School Board officials - evidence this

Court itself has discounted, see Dowell, 498 U.S. at 249 -

there is simply no evidence in the record to suggest, let alone

prove, “that it [is] unlikely that the school board would return

to its former ways.” Id. at 247. Indeed, the District Court -

the court best situated to appraise the school district’s

compliance, see Brown, 349 U.S. at 299 - expressly found,

after an exhaustive review of the record, that Respondents

“fail[ed] to . . . demonstrate that they have strategically

planned for the future.” App. 50a. In particular,

Respondents failed to submit “documentation of the strategic

planning [they] have engaged in to ensure that discrimination

does not occur in the future.” Id. Respondents simply did

not give the District Court any indication of what they would

do if or when unitary status was granted. In fact, the

Respondent School Board members did not even vote on

whether to seek unitary status in the first place. (10/25/96

Unitary Status Hearing Tr. at 25-26).

Given the absence of affirmative proof that

Respondents were unlikely to revert to their former ways, the

District Court’s finding that Respondents failed to establish

good faith was not error - let alone clear error - and, but for

its misapplication of the test established in Dowell and

Freeman, the Eleventh Circuit would have been required to

affirm. For this reason, and because the Eleventh Circuit’s

erroneous interpretation of Dowell and Freeman is in direct

conflict with the interpretation of the Tenth Circuit, this

Court should grant certiorari. III.

III. The Court of Appeals Misapplied Governing Law

in its Review of the District Court’s Factual

Findings

It is well settled that a district court’s factual findings

‘“ shall not be set aside unless clearly erroneous.’” Anderson

25

v. Bessemer, 470 U.S. 564, 573 (1985) (quoting Fed. R. Civ.

P. 52(a)). In Anderson, this Court cautioned that when a case

turns on the resolution of factual disputes, “the task of

appellate tribunals . . . [is limited to] determin[ing] whether

the trial judge’s conclusions are clearly erroneous.” Id. at

580-81. Nevertheless, the Eleventh Circuit improperly

subjected the District Court’s decision to more stringent

scrutiny solely because the Magistrate Judge - and not the

District Court - conducted the evidentiary hearing in this

case, and because the Court o f Appeals deemed the

Magistrate Judge’s credibility determinations “dispositive.”

App. 40a. A court of appeals is not free to apply an elevated

standard of review to the findings of a district court on this

basis. For this reason, this Court should review the Eleventh

Circuit’s decision.

Relying on its decision in Proffitt v. Wainwright, 685

F.2d 1227, 1237 (11th Cir. 1982), the Eleventh Circuit wrote

that “[i]n other contexts . . . [it] ha[d] cautioned district

judges from overruling a magistrate judge’s finding where

credibility determinations are dispositive.” App. 40a. It

proceeded to reverse the District Court’s decision based upon

either its improperly constrained view of the District Court’s

authority to review the magistrate’s findings, App. 40a

(“Where . . . a district judge does not personally observe the

witnesses in making a subjective finding of fact, we view

such a holding with skepticism, especially where, as here, the

finding is contrary to the one recommended by the judicial

official who observed the witnesses”), or its erroneous

application of the prevailing law. App. 20a-21a ( (“[W]e are

convinced that the district judge agreed with the magistrate

judge and found that shifting demographics was a substantial

cause of the racial imbalances in [Respondents’] student

assignments and that [Respondents] did not deliberately

cause the racial imbalances”). To reach this conclusion, the

Eleventh Circuit relied on two fundamentally flawed

premises.

26

First, the Eleventh Circuit wrongly decided that the

District Court’s factual findings involved credibility

determinations. In fact, they did not. The District Court’s

factual finding that Respondents failed to present sufficient

demographic evidence in order to meet its burden for

explaining current racial imbalances in the school system did

not turn on the credibility of a witness, but rather on the

limitations of the demographic evidence Respondents

presented. See App. 98a (“[T]he fact that the 0 to 17 age

group logically encompasses children too young and too old

to attend elementary school, counsels] against placing great

weight on the use of these statistics”). The District Court’s

factual finding that the School Board failed to comply in

good faith with its orders and the Equal Protection Clause

based, in part, on the failure of a School Board official to

understand a critical part o f the 1971 Order did not turn on

the credibility of a witness; indeed, the District Court

accepted the School Board officials’ statements as true. See

App. 134a (“It is very disturbing that Defendants’ ‘in-house’

desegregation expert testified that he did not completely

understand the import of the MTM program . . . . Certainly,

[Respondents] lack of appreciation casts doubt on the

competence of the individuals charged with the task of

desegregating the schools”).

Second, the Eleventh Circuit erroneously held that the

type of fact-finding conducted by the District Court is

entitled to less deference. As this Court observed in

Anderson, deference to a District Court’s factual findings is

warranted under the clearly erroneous standard “even when

the district court’s findings do not rest on credibility

determinations, but are based instead on physical or

documentary evidence or inferences from other facts.” 470

U.S. at 574. As discussed above, the District Court based its

findings both on documentary evidence and inferences from

other facts. It was error for the Eleventh Circuit to reverse

the District Court’s decision “simply because it [wa]s

27

convinced that it would have decided the case differently.”

Id. at 573.

Certainly, the fact that the Magistrate Judge had

engaged in fact-finding does not provide a basis for

disregarding the District Court’s factual findings. Under 28

U.S.C. § 636, a district court judge must make a de novo

determination of the magistrate judge’s findings. See United

States v. Raddatz, 447 U.S. 667, 674 (1980) (“It should be

clear that on these dispositive motions, the statute calls for a

de novo determination, not a de novo hearing. We find

nothing in the legislative history o f the statute to support the

contention that the judge is required to rehear the contested

testimony in order to carry out the statutory command to

make the required determination”).

A district court’s authority to make a de novo

determination following a magistrate judge’s hearing is

essential to protect the rights o f the litigants in matters

referred by the district court pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 636(b)(1)(B). As one commentator has observed,

[constitutional concerns explain the statutory

distinction between types o f pretrial matters. Motions

thought “dispositive” of the action w arrant. . . a higher

standard of review [by the district court] because “of

the possible constitutional objection that only an article

III judge may ultimately determine the litigation.”

12 Charles Alan Wright, etal., Federal Practice and

Procedure: Civil 2d, § 3068.2, at 334 (2d ed. 1997)

(citation omitted). This Court has previously recognized that

“Article III, § 1 [of the United States Constitution] serves

both to protect the role of the independent judiciary within

the constitutional scheme of tripartite government . . . and to

safeguard litigants’ right to have claims decided before

judges who are free from potential domination by other

branches of government.” Peretz v. United States, 501 U.S.

923, 929 n.6 (1991) (internal quotation marks and citations

28

omitted); see also Raddatz, 447 U.S. at 686 (Blackmun, J.,

concurring) (noting that litigants’ rights are adequately

protected by the statutes governing referral o f matters for

decisions by magistrate judges because “the district judge -

insulated by life tenure and irreducible salary - is waiting in

the wings, fully able to correct errors,” and therefore there is

no “threat to the judicial power or the independence of

judicial decisionmaking that underlies Art. III”). While it is

true that “litigants may waive their personal right to have an

Article III judge preside over a civil trial,” Peretz, 501 U.S. at

936, that was not the case here. Petitioners did not consent to

trial by the Magistrate Judge in this case, and never waived

their right to have an Article III judge ultimately pass upon

their claim that Respondents had not achieved unitary status.

Under these circumstances, the Eleventh Circuit’s notion that

the Magistrate Judge’s findings concerning unitary status

should be adopted conflicts with Petitioners’ right to final

resolution of their dispute by an Article III judge.

The Eleventh Circuit simply had no basis for

disregarding the factual findings of the District Court. It does

not promote judicial economy to require a District Court to

repeat the evidentiary hearing conducted by a Magistrate

Judge pursuant to a 28 U.S.C. § 636(b) referral in order for

its findings of fact to receive the deference it is due under the

“clearly erroneous” standard. This result is inconsistent with

the desire for greater judicial efficiency that motivated

Congress to enact § 636(b), and contradicts the legislative

scheme, which requires de novo review of dispositive issues

addressed by the magistrate judge, except when such

proceedings are conducted with the consent o f the parties.

To review and correct this fundamental legal error, certiorari

should be granted.

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Victor A. Bolden

Counsel of Record

Jesse M. Furman

Kenneth D. Heath

Wiggin & Dana

One Century Tower

265 Church Street

New Haven, CT 06508

(203) 498-4400

Warren Hope Dawson

Dawson Law Office

1467 Tampa Park Plaza

Tampa, Florida 33605

(813)221-1800

APPENDIX

la

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals,

Eleventh Circuit.

Andrew L. MANNING, a minor, by his father and next

friend, Willie MANNING, et ah, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY,

FLORIDA (formerly Board of Public Instruction of

Hillsborough County, Florida), et ah, Defendants-Appellants.

No. 99-2049.

March 16, 2001.

*929 Walter Crosby Few, Few & Ayala, Thomas M. Gonzalez,

Arnold B. Corsmeier, Thompson, Sizemore & Gonzalez, P.A.,

Tampa, FL, for Defendants- Appellants.

Victor Allen Bolden, Wiggin & Dana, New Haven, CT,

Jacqueline A. Berrien, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc., New York City, Warren Hope Dawson, Dawson and

Griffin, P.A., Tampa, FL, for Plaintiffs-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle

District of Florida.

Before BLACK, FAY and COX, Circuit Judges.

BLACK, Circuit Judge:

Appellants, the School Board of Hillsborough County',

Florida, and its officials, appeal two orders of the district court

which subject them to continued supervision under a federal

desegregation decree. See Manning v. Sch. Bd. o f Hillsborough

2a

County, Fla., 24 F. Supp. 2d 1277 (M.D. Fla.), mot. to alter or

amend den., mot. fo r clarification granted in part, 28 F. Supp.

2d 1353 (M.D. Fla.1998). Appellants argue that they have

eliminated the vestiges of past discrimination to the extent

practicable and have fully complied in good faith with the

desegregation decree. Accordingly, Appellants claim their

school district should be declared unitary and federal judicial

supervision should cease. Conversely, Appellees, a class of

African-American schoolchildren, contend the school district is

not unitary and federal judicial oversight o f Appellants remains

necessary. We hold that Appellants have achieved unitary

status. We reverse and remand for the district court to enter

judgment, in accordance with this opinion, declaring the

Hillsborough County school system to be unitary.

I. BACKGROUND

A. Procedural History

Appellants for many years operated a racially-

segregated, dual school system. As a result of the Supreme

Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board o f Education o f

Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954)

(Brown I), Appellees in 1958 filed this class-action lawsuit on

behalf of all "minor Negro children and their parents" residing

in Appellants' school district.1 In 1962, the district court found *

‘The lawsuit was filed in the Southern District of Florida. In

1962, the Middle District of Florida was created, and the case was

transferred to that court's docket on November 2, 1962. In a May

1971 order, the presiding district judge noted that this case was--in

1971--the oldest active case on the docket of the Middle District of

Florida. Of course, the same holds true today.

The Honorable Thurgood Marshall, prior to his appointment

to the Supreme Court, served as one of the attorneys for Appellees.

3a

that Appellants, by operating a segregated school system, had

violated the Fourteenth Amendment. For the next *930 eight

and half years, the district court issued various orders as part of

its efforts to remedy the harm caused by Appellants'

unconstitutional conduct. See, e.g., Mannings v. Bd. o f Pub.

Instruction o f Hillsborough County, Fla., 306 F. Supp. 497

(M.D. Fla. 1969).

In 1970, our predecessor court examined whether

Appellants had sufficiently eradicated the illegal dual school

system such that it could be found "unitary." See Mannings v.

Bd. o f Pub. Instruction o f Hillsborough County, Fla., 427 F.2d

874 (5th Cir.1970). Relying upon the six so-called Green2

The lead plaintiff was, and still is, Andrew L. Manning; through the

many years of litigation, his surname has frequently, and incorrectly,

been spelled "Mannings." The institutional defendant was formerly

known as the Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County.

The following are the published opinions arising from this case:

Mannings v. Bd. o f Pub. Instruction o f Hillsborough County, Fla.,

277 F.2d 370 (5th Cir.1960); Mannings v. Bd. o f Pub. Instruction of

Hillsborough County, Fla., 306 F. Supp. 497 (M.D. Fla. 1969);

Mannings v. Bd. o f Pub. Instruction o f Hillsborough County, Fla.,

427 F.2d 874 (5th Cir.1970); Mannings v. Sch. Bd. o f Hillsborough

County, Fla., 796 F. Supp. 1491 (M.D. Fla.1992); Mannings v. Sch.

Bd. o f Hillsborough County, Fla., 816F. Supp. 714 (M.D. Fla. 1993);

Mannings v. Sch. Bd. o f Hillsborough County, Fla., 149 F.R.D. 235

(M.D. Fla. 1993); Mannings v. Sch. Bd. o f Hillsborough County,

Fla., 149 F.R.D. 237 (M.D. Fla.1993); Mannings v. Sch. Bd. o f

Hillsborough County, Fla., 851 F. Supp. 436 (M.D. Fla. 1994).

Additionally, a law review article is devoted exclusively to this

litigation. See Drew S. Days, III, The Other Desegregation Story:

Eradicating the Dual School System in Hillsborough County,

Florida, 61 Fordham L. Rev. 33 (1992).

2Green v. County Sch. Bd. o f New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430, 88 S. Ct. 1689, 20 L. Ed. 2d 716 (1968).

4a

factors, the former Fifth Circuit concluded that, with regard to

three factors (transportation, extracurricular activities, and

facilities), Appellants had indeed achieved a unitary school

district. See Mannings, A l l F.2d at 878. Nonetheless, based on

its examination of three other factors (faculty desegregation,

staff desegregation, and student assignments), the court found

Appellants had fallen short and had not attained unitary status.

See id. The case was remanded to the district court with

instructions to remedy the deficiencies. See id.

After remand, the Supreme Court, in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.

Ct. 1267, 28 L. Ed. 2d 554 (1971), gave firm guidance on a

district court's equitable power to remedy illegal segregation.

On May 11, 1971, just 21 days after Swann was decided, the

district court directed Appellants to submit a comprehensive

desegregation plan that conformed with the requirements of

Swann. Thereafter, Appellants submitted such a plan, and the

district court adopted the plan in its order dated July 2, 1971

(the July 1971 Order). From 1971 to 1991, the district court's

supervision of Appellants was governed, with some minor

modifications, exclusively by the July 1971 Order.3

In 1991, Appellants and Appellees entered into a

consent decree (1991 Consent Order). The primary reason for

the 1991 Consent Order was to enable Appellants to reorganize

the school district, so as to eliminate single grade centers and to

create middle schools. The 1991 Consent Order, which was to

be implemented over a 7-year period, did not annul the July

1971 Order, but merely modified it.

Appellee moved in 1994 to enforce the 1991 Consent

Order. The matter was referred to the magistrate judge who

3For a summary of the minor modifications, see infra note 6.

5a

recommended denying the motion. The district judge, however,

deferred ruling on the motion and sua sponte recommitted the

matter to the magistrate judge to consider whether the school

district had become unitary, thereby removing the need for

federal judicial oversight.

In October 1996, the magistrate judge conducted a 7-day

hearing, at which both sides presented considerable evidence.

In August 1997, the magistrate judge issued a detailed report

and recommendation wherein she recommended the district

court find that Appellants had achieved unitary status and thus

should be released from federal judicial supervision. Without

holding an evidentiary hearing, the district judge in a 110-page

order dated October 26, 1998, rejected in part and adopted in

part the magistrate judge's report and recommendation. See

Manning, 24 F. Supp. 2d at 1277-1335. The district judge

concluded that Appellants had not attained unitary status and

therefore federal judicial supervision was still warranted.4 See

Manning, 24 F. Supp. 2d at 1335. *931 Within ten days of the

order dated October 26,1998, Appellants filed a motion to alter

or amend judgment pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e). The

district court, in a 13-page order, denied the motion on

December 4, 1998. See Manning, 28 F. Supp. 2d at 1361.

Within 30 days, Appellants filed a notice of appeal as to the

district judge's orders of October 26, 1998, and December 4,

1998.

4Before the district court, Appellees also argued that, even if

the school district were unitary, this status would not constitute a

"changed circumstance" warranting a modification or vacation of the

1991 Consent Order. See Manning, 24 F. Supp. 2d at 1287-88 (citing

Rufo v. Inmates o f Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S. 367, 112 S. Ct. 748,

116 L. Ed. 2d 867 (1992)). The district court rejected Appellees'

argument. See id. at 1288. Since Appellees do not contest this ruling

on appeal, we do not address it.

6a

B. Facts

To analyze this case that has endured for over 40 years,

we first summarize the contents of the July 1971 Order and the

1991 Consent Order, which, with minor modifications, have

served as the guideposts for Appellants' journey toward a

unitary school district. Then, we set forth the district court's